1. Introduction

Amyloidosis encompasses a group of diseases characterized by the deposition of misfolded proteins in various tissues, leading to disruption of tissue architecture and dysfunction [

1]. Cardiac involvement, known as cardiac amyloidosis (CA), carries the worst prognosis [

2]. CA primarily results from the infiltration of the myocardium by either immunoglobulin light chain fibrils (AL) or transthyretin fibrils (ATTR), causing cardiomyopathy and, if left untreated, eventually leading to sooner death [

3]. AL is derived from a misfolded N-terminal fragment of a monoclonal immunoglobulin light chain produced by plasma cells in the bone marrow [

4]. ATTR is the misfolded form of hepatically-derived transthyretin (TTR) protein, a carrier of thyroxine and retinol-binding protein in the blood; this misfolding can be due to a genetic mutation (ATTRv) or occur spontaneously (ATTRwt). It is a less aggressive disease than AL [

5]. Recent studies have demonstrated evolving trends in the epidemiology of CA, as the prevalence of CA continues to rise, likely attributed to better awareness and improvement in diagnostic modalities (6). In addition, patients are now more often diagnosed at an earlier stage of the disease, with substantially lower mortality, and these changes may have important implications for initiation and outcome of therapy (7).

CA shares many clinical features with other cardiac diseases, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and aortic stenosis, often resulting in misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis. It has been identified in approximately 10% of adult patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and those with aortic stenosis, as well as in about 13% of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction [

8,

9,

10]. Recent improvements in diagnostic imaging and heightened clinical awareness have revealed a significant prevalence of CA, particularly ATTR, in the elderly population [

11,

12,

13]. The therapeutic landscape has also advanced remarkably, with disease-modifying therapies now available that can alter the disease course and improve survival when initiated early.

However, there remains a critical need for early and accurate detection of CA to ensure patients can benefit from these emerging therapies. This review aims to explore advancements in and the role of multimodality imaging in the diagnostic workup of CA.

2. Pretest Probability of CA

The effectiveness of initial imaging techniques, such as echocardiography, cardiac tomography, and cardiac magnetic resonance, in diagnosing CA hinges on the pretest probability of the condition. Delays in diagnosing CA often stem from limited knowledge and inadequate physician knowledge of its clinical features. Suspicion of ATTR typically arises in elderly patients hospitalized for congestive heart failure or bradyarrhythmia who display unexplained left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) without hypertension. It may also present with low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis [

14].

Persistent elevation of serum troponin levels is another indicator. A common but not universal sign in advanced CA is the discrepancy between low-voltage electrocardiogram (EKG) readings and LVH observed on echocardiography. This incongruity is due to amyloid fibrils replacing myocardial cells. However, similar EKG-echocardiography discordance can also be seen in conditions like obesity, emphysema, severe hypothyroidism, and connective tissue diseases, where hypertension or valvulopathy is present. Other typical EKG findings in CA include pseudo-infarct patterns, and different types of heart blockades such as first-degree atrioventricular and fascicular blocks [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Identifying non-cardiac clues is crucial for improving the pre-imaging probability of CA, as these symptoms often precede cardiac manifestations by several years. Carpal tunnel syndrome is particularly significant, frequently occurring in men with ATTR and appearing 5-10 years before cardiac symptoms [

19]. Approximately 10% of patients undergoing carpal tunnel surgery have amyloid deposits in their tenosynovial tissue [

19]. Additional musculoskeletal indicators include lumbar spinal stenosis, spontaneous biceps tendon rupture, and joint arthropathies [

20,

21,

22,

23].

Peripheral neuropathy, proteinuria, dysautonomia, and macroglossia are frequently associated with AL amyloidosis. Peripheral neuropathy is very frequent in ATTR as well, especially in ATTRv. Clinically, CA patients often present with dyspnea, fatigue, and edema due to heart failure, or syncope associated with bradyarrhythmias. Chronic elevations in cardiac biomarkers, including troponin and brain natriuretic peptide, can also raise suspicion for CA [

24].

3. Echocardiography

Echocardiography is usually the first diagnostic tool in the evaluation of CA patients that often present with symptoms of dyspnea and heart failure [

25] (

Table 1). It can detect features such as left and right ventricular wall thickening, biatrial enlargement, interatrial septal thickening, thickened atrioventricular valves, pericardial effusion, and impaired left and right ventricular strain on advanced imaging technique that raise suspicion for CA warranting further work up [

26,

27,

28,

29]. It is important to know that certain echocardiographic characteristics are more associated with advanced stages of the disease, including pericardial effusion, restrictive pattern and LA thickness of more than 6 mm.

3.1. Left Ventricular Features and Strain Analysis

CA typically manifests as diastolic heart failure with elevated filling pressures, increased wall thickness, and reduced chamber size [

29]. This results from the deposition of amyloid fibrils, which disrupt the myocardial wall and lead to thickened myocardium. Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is a predominant echocardiographic finding in CA, appearing symmetrically in AL and asymmetrically in ATTR [

30]. Certain echocardiographic features help differentiate CA from other hypertrophic cardiomyopathies, such as LV wall thickness exceeding 12 mm and grade 2 or higher diastolic dysfunction, in the absence of aortic valve disease or severe uncontrolled hypertension [

31]. Additionally, amyloid deposition gives the myocardium a distinctive speckled or granular appearance on 2-D echocardiography [

32].

In early stages, diastolic parameters transition from low E-wave and high A-wave velocities, a decreased E/A ratio, and normal deceleration time to later stages where there is a normal E-wave, small A-wave, high E/A ratio, and rapid deceleration time [

33]. Tissue Doppler commonly reveals greatly reduced mitral and tricuspid e' velocities and a high E/e' ratio, which suggest elevated filling pressures even in the absence of noticeable LV wall thickening, indicative of a restrictive myocardial pattern [

33,

34]. A restrictive pattern on tissue Doppler imaging of the mitral annulus, characterized by e', a', and s' velocities below 5 cm/s and accompanied by pericardial effusion, strongly suggests CA [

29]. AL often shows a restrictive pattern earlier in its progression compared to ATTR. Furthermore, a small S-wave on tissue Doppler is indicative of advanced disease [

29].

Speckle tracking echocardiography (STE) reveals significantly impaired left ventricular global longitudinal strain (LVGLS) despite a preserved ejection fraction, indicating a poor prognosis [

28]. The basal and mid LV segments exhibit more severe LVGLS impairment compared to the apical segment, resulting in a distinctive "cherry on top" appearance on the bull's eye plot [

35]. A relative regional strain ratio above 1 is highly sensitive and specific for diagnosing CA [

32]. AL shows worse LVGLS than ATTR for a given wall thickness [

36]. Research has found that an LVEF/GLS ratio greater than 4.95 is a better screening tool, with 75% sensitivity and 66% specificity [

37]. Additionally, three-dimensional (3-D) STE, which incorporates parameters like global area strain and global circumferential strain, offers enhanced sensitivity for identifying CA features and assessing the disease prognosis [

37,

38].

3.2. Left Atrial Features and Strain Analysis

Biatrial enlargement, commonly seen due to elevated filling pressures, serves as an imaging marker for early subclinical changes in ATTR [

39]. Amyloid fibril deposition in the atrial myocardium causes atrial septal thickening, with measurements exceeding 6 mm having a 100% specificity for diagnosing CA [

37]. Additionally, STE can detect atrial cardiopathy caused by amyloid deposition, as evidenced by impaired left atrial (LA) strain in all phases compared to age-matched controls [

40]. The LA reservoir strain is becoming a valuable indicator for diastolic dysfunction, with both LA reservoir and contractile strain proving to be superior predictors of elevated left ventricular filling pressure compared to LA volume and conventional Doppler parameters [

41]. This underscores the importance of LA strain analysis in the early detection of CA, enabling the timely initiation of therapies for improved patient outcomes. In patients with ATTR, LA reservoir and contractile strain are lower than in those with AL or those without CA, even in the absence of atrial arrhythmias [

41]. Moreover, LA strain can distinguish CA from other hypertrophic cardiomyopathies (HCM), as CA patients exhibit lower LA strain than those with HCM despite having a preserved ejection fraction [

40]. Atrial dysfunction in CA increases the risk of thromboembolic events, even in patients who are in sinus rhythm [

42]. Additionally, LA reservoir strain serves as an independent predictor of cardiovascular-related death and heart failure hospitalization in patients with ATTR [

43,

44,

45].

3.3. Right Ventricular Features and Strain Analysis

CA also affects the right ventricular (RV) chamber and the RV myocardial walls. This condition results in increased RV wall thickness, basal diameter, and inferior vena cava size, along with reduced chamber volume and RV systolic function as measured by tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) [

46]. Unexplained RV wall thickening exceeding 5 mm and reduced function are indicative of CA [

37]. Both STE and traditional echocardiography have demonstrated impaired RV free wall longitudinal strain with apical sparing and reduced TAPSE, respectively [

47]. Among CA subtypes, AL exhibits more pronounced apical sparing compared to ATTR. An RV apical/(basal+middle) ratio greater than 0.8 is reported to have a sensitivity of 97.8%, specificity of 90.0%, and accuracy of 94.7% in distinguishing AL from ATTR [

47]. However, it is important to be note that echo, as a diagnostic tool, does not have the capacity to distinguish between ATTR and AL. Finally, echocardiographic measures of both systolic and diastolic function, including LVEF, longitudinal strain, LV stroke volume and E/e′ have been shown to be independent prognostic factors for mortality in patients with ATTR [

48].

4. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) is pivotal in the precise and detailed assessment of cardiac tissue and morphology, offering high spatial resolution and tissue contrast differentiation [

4]. It is the gold standard in the morphological and biomechanical assessment of cardiac chambers with superiority in myocardial tissue characterization [

49]. While not the primary diagnostic modality due to cost and expertise requirements, CMR serves as a valuable adjunct to echocardiography in identifying CA and evaluating treatment response and prognosis. It is able to identify the extracellular expansion of myocardium by the deposition of amyloid fibrils through the typical global and predominant subendocardial distribution of the late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) with a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 92% [

50]. In addition, a key characteristic considered pathognomonic for CA is the retention of LGE by the amyloid filled expanded extracellular matrix to a similar extent as the blood pool. This result in overlapping T1 recovery curves on the inversion T1 scout sequence conducted before LGE imaging, making it challenging to identify the T1 null point of healthy myocardium necessary for accurate LGE imaging [

51]. Although CMR imaging is unable to explicitly distinguish between ATTR and AL, LGE is typically more extensive in ATTR and patients with ATTR often exhibit a transmural pattern of LGE with involvement of the RV wall [

52]. Moreover, diffuse LGE offers additional prognostic value beyond cardiac biomarker staging in CA, with transmural LGE being linked to a poor prognosis. [

53] Despite the numerous advantages of LGE, it has limitations, including its inability to quantify amyloid burden. Additionally, its use is restricted in patients with renal impairment, specifically those with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m², due to the risk of developing nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, a potentially fatal condition [

54].

5. T1 Mapping

T1 mapping provides a detailed understanding of myocardial response to CA by accurately quantifying longitudinal relaxation times on a pixel-by-pixel basis. It has the advantage over LGE by quantifying the amyloid burden also does not need contrast, therefore, native T1 mapping can safely be used in kidney disease [

55]. Native T1 shows elevated levels in the early stages of CA even before ventricular thickening or detectable LGE appears [

56]. In fact, elevated native (pre-contrast) myocardial T1 demonstrates high diagnostic accuracy for CA with values below 1,036 ms and above 1,164 ms showing 98% negative predictive and 98% positive predictive values for CA, respectively [

56]. This makes native T1 mapping a useful tool in situations where the use of contrast agents is contraindicated. Beyond facilitating CA diagnosis, native T1 mapping is crucial for monitoring disease progression. Poor prognosis is linked to pre-contrast T1 times exceeding 1044 ms for AL and 1077 ms for ATTR [

57,

58]. Furthermore, T1 mapping can estimate the myocardial extracellular volume (ECV) fraction, acting as a surrogate for quantifying amyloid burden and correlating with disease severity in both AL and ATTR. ECV measurement is also effective in tracking treatment response in AL patients [

59,

60,

61].

6. T2 Mapping

T2 mapping complements T1, LGE, and ECV findings by visualizing and quantifying myocardial edema. It is sensitive to edema associated with myocyte toxicity, with elevated T2 times reflecting the degree of myocyte edema [

62]. Although T2 times are elevated in both ATTR and AL, untreated AL patients exhibit higher T2 values compared to treated AL and ATTR patients [

62]. This is likely due to greater edema caused by the direct toxicity of light chains in AL [

63]. Consequently, T2 mapping is particularly relevant for AL prognostication [

52,

64]. Moreover, the utility of elevated T2 increases in quantifying and prognosticating AL, as most other features of disease severity, such as LV mass, wall thickness, LGE transmural extent, and RV involvement, are more commonly associated with ATTR amyloid [

52].

Overall, CMR with its multi-faceted approach, including LGE, T1 mapping, ECV measurement, T2 mapping presents a comprehensive toolkit for the precise diagnosis, characterization, and prognostication of CA, ultimately guiding therapeutic strategies and improving patient outcomes.

7. Role of CMR In Determining Prognosis and Treatment Response

The volumetric measurements on CMR can predict prognosis in CA. In a study 54 consecutive patients (age 66 ± 10 years, 59% males) with confirmed AL and mean LV ejection fraction of 60 ± 12%, left trial ejection fraction as assessed by CMR was associated with NYHA functional class, Mayo Clinic stage, myocardial LGE and 2-year mortality (65). A study that incorporated deep learning to classify CA on MR images concluded that cine- convolutional neural network (CNN) leads to significantly better discrimination between AL and ATTR as compared to gadolinium-CNN or human readers, but with lower performance than reported in studies where visual diagnosis is easy, and is currently suboptimal for clinical practice (66).

CMR plays a crucial role as an imaging modality to monitor treatment response in both ATTR and AL. A prospective study investigating 221 AL patients, who underwent surveillance CMR at 6 and/or 12 months after initiating chemotherapy, demonstrated that native T1 can track the treatment response in AL (67). The change in native T1 reflected the composite change in ECV and T2 and was independently associated with mortality (67). Data from the Bern Cardiac Amyloidosis Registry assessed CMR changes after treatment with Tafamidis and found that the initiation of Tafamidis preserved CMR-measured biventricular function and reduced LV mass at 12 months compared with untreated patients (68).

8. Cardiac Computed Tomography

Cardiac computed tomography (CT) is a noninvasive diagnostic modality that provides comprehensive information on cardiac chamber morphology, perfusion, strain, and scar presence. It quantifies the ECV fraction, typically performed with precontrast and delayed-phase postcontrast imaging [

69,

70]. Previous studies have shown that CT performs well in measuring ECV fraction compared with CMR [

71]. Cardiac CT can also distinguish CA from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), as the mean ECV is significantly greater in CA (54.7% ± 9.7) compared to HCM (34.6% ± 9.1) and normal myocardium (35.9% ± 9.9). Additionally, higher ECV values correlate with worse outcomes in the CA group [

72].

ECV fraction has also been used to assess the myocardium in various procedures and disease processes, such as aortic valve replacement, atrial fibrillation ablation, hemodialysis, chemotherapy, and heart failure [

70]. The process involves normalizing the pre- and postcontrast imaging to blood hematocrit values to obtain the ECV fraction [

73]. Kidoh et al. demonstrated high sensitivity (90%) and specificity (92%) of CT-derived ECV fraction in identifying CA. Furthermore, the myocardium-to-lumen signal ratio showed a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 92% for detecting CA [

74]. This technique avoids the need for unenhanced CT and aids in diagnosing CA when hematocrit values are unavailable or laboratory tests are delayed.

However, caution is necessary as the ECV fraction can be elevated in conditions causing myocardial fibrosis, infarction, inflammation, and edema [

70]. Additionally, CT imaging of the myocardium is limited by motion artifacts and lower image contrast compared with MRI. Despite these limitations, cardiac CT is fast, widely available, and valuable for raising suspicion of CA, particularly when patients undergo cardiac CT for other evaluations, such as planning for transcatheter aortic valve replacement in low-flow low-gradient aortic stenosis patients. It is also beneficial for patients who cannot undergo cardiac MRI due to the presence of cardiac devices or prostheses that preclude MRI.

Further research is needed to maximize the utility of cardiac CT, incorporate it into diagnostic algorithms for CA, and define ECV fraction thresholds to aid in the diagnosis of CA.

9. Nuclear Scintigraphy with Bone-Avid Tracers

Nuclear scintigraphy has revolutionized the diagnostic approach for CA. This non-invasive method has significantly reduced the reliance on endomyocardial biopsies, enabling more widespread detection of CA. A multicenter study that comprised of >1000 patients with suspected CA demonstrated the high sensitivity and specificity of 99mTc-labeled bone-seeking tracers in identifying ATTR amyloidosis in the absence of paraproteinemia [

75]. In addition, a meta-analysis of six studies with > 500 patients demonstrated that bone scintigraphy using technetium-labeled radiotracers had a high diagnostic yield, exhibiting a sensitivity of 92.2% and a specificity of 95.4% [

76]. In the United States, the 99mTc-pyrophosphate (99mTc-PYP) tracer is predominantly used, whereas in Europe, 99mTc-hydroxymethylene diphosphonate (99mTc-HMDP) and 99mTc-DPD are more common. These tracers exhibit comparable diagnostic efficacy.

Notably, bone scintigraphy is effective only for detecting ATTR, while histological confirmation is necessary for diagnosing AL. The selective affinity of bone-seeking tracers for ATTR over AL is attributed to their calcium-binding properties. Research indicates that greater density of microcalcifications exists in ATTR compared to AL, which potentially contributes to this selectivity, regardless of age, cardiac function, and serum calcium and creatinine levels [

77].

Interpreting nuclear scintigraphy involves a semi-quantitative approach, visually grading tracer uptake relative to bone uptake in the rib cage. The grading system ranges from 0 for no myocardial uptake, to 1 for mild uptake (less than in bone), 2 for uptake equal to bone, and 3 for substantial uptake (greater than in bone) [

78]. In a multicenter study with a large cohort of biopsy-proven ATTR patients, 100% specificity and positive predictive value for ATTR were confirmed when grade 2 or 3 uptake was observed without paraproteinemia [

75,

79].

Quantitative assessment entails delineating circular regions of interest over the heart and mirrored on the contralateral chest wall. Radiotracer uptake is quantified using the heart-to-contralateral lung (H/CL) ratio, where a ratio exceeding 1.5 suggests ATTR diagnosis, and a ratio ≥1.6 is associated with poor survival [

80,

81].

It's crucial to note that nuclear scintigraphy, especially when showing a visual grade of 2 or 3 indicating myocardial uptake, boasts high sensitivity (>99%) for ATTR but exhibits a relatively lower specificity of 82-86%. This diminished specificity stems from the fact that patients with AL can also display grades of 1 or 2 [

80,

81,

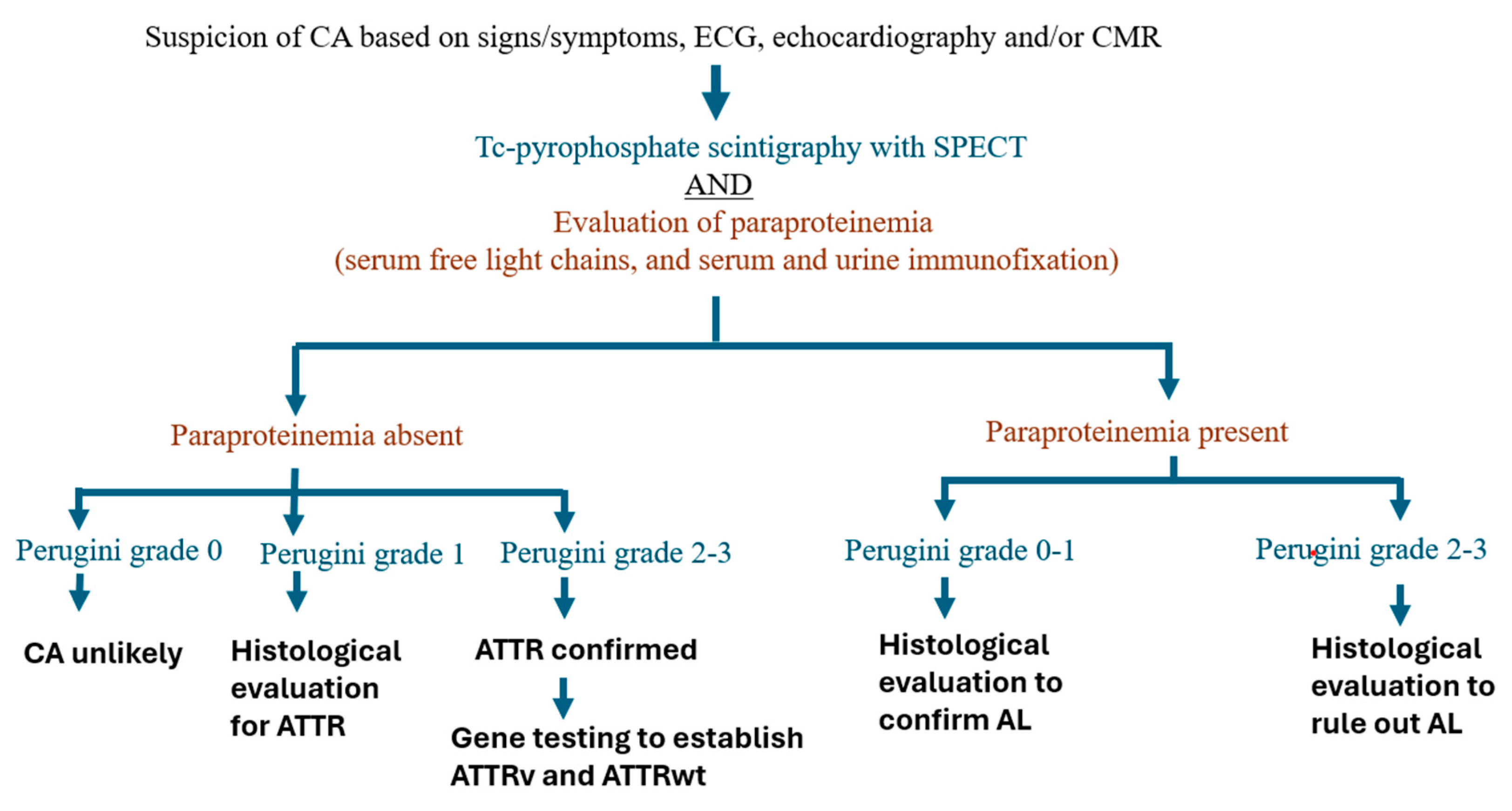

82]. Therefore, bone scintigraphy alone cannot definitively diagnose ATTR or exclude AL. Standard practice involves conducting urine and serum immunofixation electrophoresis and obtaining serum free light chains and the kappa/lambda ratio to rule out AL disease. When these tests yield negative results for AL, the specificity of nuclear scintigraphy rises to 100%. Consequently, a confident diagnosis of ATTR can be made without histological confirmation in a patient exhibiting a typical clinical phenotype (such as a history of bilateral carpal tunnel surgery), consistent echocardiographic and/or CMR features of CA, grade 2 or 3 tracer uptake on 99mTc-PYP scintigraphy, and no detectable monoclonal gammopathy in the blood and urine.

The optimal approach to multimodality imaging has been described in

Figure 1.

10. When Do We Need Endomyocardial Biopsy

Histological confirmation and identification of the type of amyloidosis are recommended for patients with detectable monoclonal immunoglobulin (83). A diagnosis of AL amyloidosis always requires a tissue biopsy. In certain situations, a tissue biopsy may also be necessary for diagnosing ATTR, particularly when nuclear scintigraphy shows a visual grade below 2, serum and urine tests are negative for AL, and clinical, echocardiographic, and/or MRI findings suggest CA. Notably, ATTRv associated with the Ser77Tyr and P64L variants may present with an atypical nuclear scintigraphy appearance, showing only grade 1 uptake, even in the presence of classic clinical, morphological, and functional features on echocardiography and CMR (84). In these cases, tissue biopsy becomes essential to confirm an ATTR diagnosis.

The distinctive apple-green birefringence pattern on Congo red–stained tissue sections under polarized light microscopy is a hallmark of amyloid deposits. Amyloid typing, critical for distinguishing between AL and ATTR types, is carried out using immunohistochemistry and mass spectrometry. While endomyocardial biopsy offers 100% sensitivity for diagnosing cardiac amyloidosis, it carries potential risks such as ventricular perforation, cardiac tamponade, and ventricular arrhythmias (85,86). An alternative approach is abdominal fat pad fine-needle aspiration biopsy, though its sensitivity is low, especially in wild-type ATTR (~15%), and it has a high rate of inadequate specimens, making it a less reliable diagnostic tool (87).

11. Future Directions

While multimodality imaging has played a crucial role in diagnosing CA, the only modality that can distinguish ATTR from AL is nuclear scintigraphy utilizing bone-seeking tracers. However, AL patients can also exhibit mild tracer uptake, making it impossible to differentiate between the two predominant CA subtypes on the scintigraphy, especially in the presence of paraproteinemia. Hence, biopsy becomes mandatory in such circumstances, thereby necessitating further research in the area to discover imaging-based biomarkers and radiotracers that could effectively differentiate between the two CA subtypes noninvasively even in the presence of paraproteinemia.

Another limitation of nuclear scintigraphy is the rare ATTR variants that show grade 0 or 1 on planar image and do not demonstrate tracer uptake. The suspicion for CA in these scenarios is often based on clinical phenotype in conjunction with echocardiographic and/or CMR features, thereby prompting endomyocardial biopsy to confirm ATTRv. The precise mechanism(s) through which these certain ATTRv fibrils do not exhibit tracer uptake remains unclear, and further research is needed in this area.

CMR-based markers, particularly ECV, have excellent prognostic utility. There is a need to incorporate these well-established imaging-based markers into the existing CA staging systems and prognostic algorithms to further refine them.

Future research should focus on identifying novel, non-invasive biomarkers for early detection and differentiation of AL and ATTR. Advances in genetic markers, serum proteomics, and microRNAs could improve diagnostic accuracy and facilitate the differentiation of CA subtypes.

Future studies should explore personalized treatment approaches, including investigating combination therapies that target multiple mechanisms of disease. Understanding the synergistic effects of combining treatments could provide more effective and sustainable therapeutic options.

12. Conclusions

The advent of advanced imaging modalities has significantly transformed the detection and management of CA. Echocardiography frequently serves as the initial test that raises suspicion for CA, especially in patients with high pretest probability based on comorbid conditions, cardiac biomarkers, and EKG findings. Cardiac CT and MRI are instrumental in distinguishing CA from other causes of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and infiltrative diseases, while also providing valuable prognostic information and monitoring disease progression through extracellular volume (ECV) measurements. Nuclear scintigraphy with bone-avid tracers, such as Tc-99m PYP scintigraphy, has a high diagnostic yield for ATTR in the absence of paraproteinemia, often eliminating the need for an endomyocardial biopsy. Collectively, these imaging advancements have been pivotal in the accurate identification, quantification of disease burden, tracking of disease progression, and guiding the management and treatment response of CA, thereby improving patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. and Z.B.; methodology, S.B, B.K.; software, S.B, B.K, and Z.B.; validation, S.B, B.K, and Z.B; formal analysis, S.B, B.K, and Z.B.; investigation, S.B and Z.B.; resources, B.K, Z.B and S.B.; data curation, S.B and Z.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.B, B.K and S.B.; writing—review and editing, Z.B, B.K, and S.B.; visualization, Z.B, B.K, and S.B; supervision, S.B; project administration, S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Merlini G, Bellotti V. Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2003 Aug 7;349(6):583-96.

- Bukhari S. Cardiac amyloidosis: state-of-the-art review. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2023 May 28;20(5):361-375.

- Buxbaum J, Jacobson DR, Tagoe C, Alexander A, Kitzman DW, Greenberg B, Thaneemit-Chen S, Lavori P. Transthyretin V122I in African Americans with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Apr 18;47(8):1724-5.

- Masri A, Bukhari S, Eisele YS, Soman P. Molecular Imaging of Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Nucl Med. 2020 Jul;61(7):965-970.

- Bukhari S, Khan SZ, Bashir Z. Atrial Fibrillation, Thromboembolic Risk, and Anticoagulation in Cardiac Amyloidosis: A Review. J Card Fail. 2023 Jan;29(1):76-86.

- Porcari A, Allegro V, Saro R, Varrà GG, Pagura L, Rossi M, Lalario A, Longo F, Korcova R, Dal Ferro M, et al. Evolving trends in epidemiology and natural history of cardiac amyloidosis: 30-year experience from a tertiary referral center for cardiomyopathies. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Nov 7;9:1026440.

- Ioannou A, Patel RK, Razvi Y, Porcari A, Sinagra G, Venneri L, Bandera F, Masi A, Williams GE, O'Beara S, et al. Impact of Earlier Diagnosis in Cardiac ATTR Amyloidosis Over the Course of 20 Years. Circulation. 2022 Nov 29;146(22):1657-1670.

- Bukhari, S, Nieves, R, Fatima, S. et al. HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY MIMICKING AMYLOID CARDIOMYOPATHY. JACC. 2021 May, 77 (18_Supplement_1) 1921.

- Castaño A, Narotsky DL, Hamid N, Khalique OK, Morgenstern R, DeLuca A, Rubin J, Chiuzan C, Nazif T, Vahl T, et al. Unveiling transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis and its predictors among elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Eur Heart J. 2017 Oct 7;38(38):2879-2887.

- González-López E, Gallego-Delgado M, Guzzo-Merello G, de Haro-Del Moral FJ, Cobo-Marcos M, Robles C, Bornstein B, Salas C, Lara-Pezzi E, Alonso-Pulpon L, et al. Wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis as a cause of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2015 Oct 7;36(38):2585-94.

- Bashir Z, Musharraf M, Azam R, Bukhari S. Imaging modalities in cardiac amyloidosis. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2024 Dec;49(12):102858.

- Bukhari S, Bashir Z. Diagnostic Modalities in the Detection of Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Clin Med. 2024 Jul 12;13(14):4075.

- Gilstrap LG, Dominici F, Wang Y, El-Sady MS, Singh A, Di Carli MF, Falk RH, Dorbala S. Epidemiology of Cardiac Amyloidosis-Associated Heart Failure Hospitalizations Among Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries in the United States. Circ Heart Fail. 2019 Jun;12(6):e005407.

- Bukhari S, Oliveros E, Parekh H, Farmakis D. Epidemiology, Mechanisms, and Management of Atrial Fibrillation in Cardiac Amyloidosis. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023, 48, 101571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari SB, Nieves A, Eisele R, Follansbee Y, Soman WP. Clinical Predictors of positive 99mTc-99m pyrophosphate scan in patients hospitalized for decompensated heart failure. J Nucl Med. 2020;61(Supplement 1):659.

- Murtagh, B. , et al., Electrocardiographic findings in primary systemic amyloidosis and biopsy-proven cardiac involvement. Am J Cardiol, 2005. 95(4): p.

- Bukhari SM, Shpilsky S, Nieves D, Bashir R, Soman Z. Development and validation of a diagnostic model and scoring system for transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. J Investig Med. 2021, 69, 1071–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari SM, Shpilsky S, Nieves D, Soman R. Amyloidosis prediction score: a clinical model for diagnosing Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Card Fail. 2020;26(10 Supplement):33.

- Sperry BW, Reyes BA, Ikram A, Donnelly JP, Phelan D, Jaber WA, Shapiro D, Evans PJ, Maschke S, Kilpatrick SE, et al. Tenosynovial and Cardiac Amyloidosis in Patients Undergoing Carpal Tunnel Release. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Oct 23;72(17):2040-2050.

- Maurer MS, Smiley D, Simsolo E, Remotti F, Bustamante A, Teruya S, Helmke S, Einstein AJ, Lehman R, Giles JT, et al. Analysis of lumbar spine stenosis specimens for identification of amyloid. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022 Dec;70(12):3538-3548.

- Rubin J, Alvarez J, Teruya S, Castano A, Lehman RA, Weidenbaum M, Geller JA, Helmke S, Maurer MS. Hip and knee arthroplasty are common among patients with transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis, occurring years before cardiac amyloid diagnosis: can we identify affected patients earlier? Amyloid. 2017 Dec;24(4):226-230.

- Geller HI, Singh A, Alexander KM, Mirto TM, Falk RH. Association Between Ruptured Distal Biceps Tendon and Wild-Type Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. JAMA. 2017 Sep 12;318(10):962-963.

- Eldhagen P, Berg S, Lund LH, Sörensson P, Suhr OB, Westermark P. Transthyretin amyloid deposits in lumbar spinal stenosis and assessment of signs of systemic amyloidosis. J Intern Med. 2021 Jun;289(6):895-905.

- Bashir Z, Younus A, Dhillon S, Kasi A, Bukhari S. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of cardiac amyloidosis. J Investig Med. 2024 Oct;72(7):620-632.

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021 Sep 21;42(36):3599-3726. . Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021 Dec 21;42(48):4901. [CrossRef]

- Liang S, Liu Z, Li Q, He W, Huang H. Advance of echocardiography in cardiac amyloidosis. Heart Fail Rev. 2023 Nov;28(6):1345-1356.

- Bukhari S, Barakat AF, Eisele YS, Nieves R, Jain S, Saba S, Follansbee WP, Brownell A, Soman P. Prevalence of Atrial Fibrillation and Thromboembolic Risk in Wild-Type Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2021 Mar 30;143(13):1335-1337.

- Dorbala S, Cuddy S, Falk RH. How to Image Cardiac Amyloidosis: A Practical Approach. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 Jun;13(6):1368-1383.

- Cuddy SAM, Chetrit M, Jankowski M, Desai M, Falk RH, Weiner RB, Klein AL, Phelan D, Grogan M. Practical Points for Echocardiography in Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2022 Sep;35(9):A31-A40.

- Martinez-Naharro A, Baksi AJ, Hawkins PN, Fontana M. Diagnostic imaging of cardiac amyloidosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020 Jul;17(7):413-426.

- Dorbala S, Ando Y, Bokhari S, Dispenzieri A, Falk RH, Ferrari VA, Fontana M, Gheysens O, Gillmore JD, Glaudemans AWJM, et al. ASNC/AHA/ASE/EANM/HFSA/ISA/SCMR/SNMMI Expert Consensus Recommendations for Multimodality Imaging in Cardiac Amyloidosis: Part 1 of 2-Evidence Base and Standardized Methods of Imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021 Jul;14(7):e000029.

- Bashir Z, Chen EW, Tori K, Ghosalkar D, Aurigemma GP, Dickey JB, Haines P. Insight into different phenotypic presentations of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2023 Jul-Aug;79:80-88.

- Rapezzi C, Aimo A, Barison A, Emdin M, Porcari A, Linhart A, Keren A, Merlo M, Sinagra G. Restrictive cardiomyopathy: definition and diagnosis. Eur Heart J. 2022, 43, 4679–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgendy IY, Bukhari S, Barakat AF, Pepine CJ, Lindley KJ, Miller EC; American College of Cardiology Cardiovascular Disease in Women Committee. Maternal Stroke: A Call for Action. Circulation. 2021 Feb 16;143(7):727-738.

- Bravo PE, Fujikura K, Kijewski MF, Jerosch-Herold M, Jacob S, El-Sady MS, Sticka W, Dubey S, Belanger A, Park MA, et al. Relative Apical Sparing of Myocardial Longitudinal Strain Is Explained by Regional Differences in Total Amyloid Mass Rather Than the Proportion of Amyloid Deposits. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019 Jul;12(7 Pt 1):1165-1173.

- Quarta CC, Solomon SD, Uraizee I, Kruger J, Longhi S, Ferlito M, Gagliardi C, Milandri A, Rapezzi C, Falk RH. Left ventricular structure and function in transthyretin-related versus light-chain cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2014 May 6;129(18):1840-9.

- Kyrouac D, Schiffer W, Lennep B, Fergestrom N, Zhang KW, Gorcsan J 3rd, Lenihan DJ, Mitchell JD. Echocardiographic and clinical predictors of cardiac amyloidosis: limitations of apical sparing. ESC Heart Fail. 2022 Feb;9(1):385-397.

- Bukhari S, Fatima S, Barakat AF, Fogerty AE, Weinberg I, Elgendy IY. Venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and postpartum period. Eur J Intern Med. 2022 Mar;97:8-17.

- Minamisawa M, Inciardi RM, Claggett B, Cuddy SAM, Quarta CC, Shah AM, Dorbala S, Falk RH, Matsushita K, Kitzman DW, et al. Left atrial structure and function of the amyloidogenic V122I transthyretin variant in elderly African Americans. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021 Aug;23(8):1290-1295.

- Monte IP, Faro DC, Trimarchi G, de Gaetano F, Campisi M, Losi V, Teresi L, Di Bella G, Tamburino C, de Gregorio C. Left Atrial Strain Imaging by Speckle Tracking Echocardiography: The Supportive Diagnostic Value in Cardiac Amyloidosis and Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023 Jun 15;10(6):261.

- Inoue K, Khan FH, Remme EW, Ohte N, García-Izquierdo E, Chetrit M, Moñivas-Palomero V, Mingo-Santos S, Andersen ØS, Gude E, et al. Determinants of left atrial reservoir and pump strain and use of atrial strain for evaluation of left ventricular filling pressure. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021 Dec 18;23(1):61-70.

- Aimo A, Fabiani I, Giannoni A, Mandoli GE, Pastore MC, Vergaro G, Spini V, Chubuchny V, Pasanisi EM, Petersen C, et al. Multi-chamber speckle tracking imaging and diagnostic value of left atrial strain in cardiac amyloidosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022 Dec 19;24(1):130-141.

- Bukhari S, Kasi A, Khan B. Bradyarrhythmias in Cardiac Amyloidosis and Role of Pacemaker. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023 Nov;48(11):101912.

- Oike F, Usuku H, Yamamoto E, Yamada T, Egashira K, Morioka M, Nishi M, Komorita T, Hirakawa K, Tabata N, et al. Prognostic value of left atrial strain in patients with wild-type transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. ESC Heart Fail. 2021 Dec;8(6):5316-5326.

- Bukhari S, Khan B. Prevalence of ventricular arrhythmias and role of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in cardiac amyloidosis. J Cardiol. 2023 May;81(5):429-433.

- Cicco S, Solimando AG, Buono R, Susca N, Inglese G, Melaccio A, Prete M, Ria R, Racanelli V, Vacca A. Right Heart Changes Impact on Clinical Phenotype of Amyloid Cardiac Involvement: A Single Centre Study. Life (Basel). 2020 Oct 18;10(10):247.

- Moñivas Palomero V, Durante-Lopez A, Sanabria MT, Cubero JS, González-Mirelis J, Lopez-Ibor JV, Navarro Rico SM, Krsnik I, Dominguez F, Mingo AM, et al. Role of Right Ventricular Strain Measured by Two-Dimensional Echocardiography in the Diagnosis of Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019 Jul;32(7):845-853.e1.

- Bukhari S, Bashir Z, Shpilsky D, Eisele YS, Soman P. Abstract 16145: reduced ejection fraction at diagnosis is an independent predictor of mortality in transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2020;142(suppl 3):A16145-A16145. [CrossRef]

- Korthals D, Chatzantonis G, Bietenbeck M, Meier C, Stalling P, Yilmaz A. CMR-based T1-mapping offers superior diagnostic value compared to longitudinal strain-based assessment of relative apical sparing in cardiac amyloidosis. Sci Rep. 2021 Jul 30;11(1):15521.

- Zhao L, Tian Z, Fang Q. Diagnostic accuracy of cardiovascular magnetic resonance for patients with suspected cardiac amyloidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016 Jun 7;16:129.

- Khedraki R, Robinson AA, Jordan T, Grodin JL, Mohan RC. A Review of Current and Evolving Imaging Techniques in Cardiac Amyloidosis. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2023 Mar;25(3):43-63.

- Dungu JN, Valencia O, Pinney JH, Gibbs SD, Rowczenio D, Gilbertson JA, Lachmann HJ, Wechalekar A, Gillmore JD, Whelan CJ, et al. CMR-based differentiation of AL and ATTR cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014 Feb;7(2):133-42.

- Boynton SJ, Geske JB, Dispenzieri A, Syed IS, Hanson TJ, Grogan M, Araoz PA. LGE Provides Incremental Prognostic Information Over Serum Biomarkers in AL Cardiac Amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016 Jun;9(6):680-6.

- Yang L, Krefting I, Gorovets A, Marzella L, Kaiser J, Boucher R, Rieves D. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and class labeling of gadolinium-based contrast agents by the Food and Drug Administration. Radiology. 2012 Oct;265(1):248-53.

- Olausson E, Wertz J, Fridman Y, Bering P, Maanja M, Niklasson L, Wong TC, Fukui M, Cavalcante JL, Cater G, et al. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis associates with incident ventricular arrhythmia in implantable cardioverter defibrillator recipients. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Feb 16:2023.02.15.23285925.

- Karamitsos TD, Piechnik SK, Banypersad SM, Fontana M, Ntusi NB, Ferreira VM, Whelan CJ, Myerson SG, Robson MD, Hawkins PN, et al. Noncontrast T1 mapping for the diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013 Apr;6(4):488-97.

- Banypersad SM, Fontana M, Maestrini V, Sado DM, Captur G, Petrie A, Piechnik SK, Whelan CJ, Herrey AS, Gillmore JD, et al. T1 mapping and survival in systemic light-chain amyloidosis. Eur Heart J. 2015 Jan 21;36(4):244-51.

- Martinez-Naharro A, Kotecha T, Norrington K, Boldrini M, Rezk T, Quarta C, Treibel TA, Whelan CJ, Knight DS, Kellman P, et al. Native T1 and Extracellular Volume in Transthyretin Amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019 May;12(5):810-819.

- Bukhari S, Khan SZ, Ghoweba M, Khan B, Bashir Z. Arrhythmias and Device Therapies in Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Clin Med. 2024 Feb 25;13(5):1300.

- Banypersad SM, Sado DM, Flett AS, Gibbs SD, Pinney JH, Maestrini V, Cox AT, Fontana M, Whelan CJ, Wechalekar AD, et al. Quantification of myocardial extracellular volume fraction in systemic AL amyloidosis: an equilibrium contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013 Jan 1;6(1):34-9.

- Martinez-Naharro A, Abdel-Gadir A, Treibel TA, Zumbo G, Knight DS, Rosmini S, Lane T, Mahmood S, Sachchithanantham S, Whelan CJ, et al. CMR-Verified Regression of Cardiac AL Amyloid After Chemotherapy. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Jan;11(1):152-154.

- Kotecha T, Martinez-Naharro A, Treibel TA, Francis R, Nordin S, Abdel-Gadir A, Knight DS, Zumbo G, Rosmini S, Maestrini V, et al. Myocardial Edema and Prognosis in Amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jun 26;71(25):2919-2931.

- O'Brien AT, Gil KE, Varghese J, Simonetti OP, Zareba KM. T2 mapping in myocardial disease: a comprehensive review. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2022 Jun 6;24(1):33.

- Bukhari, S.; Fatima, S.; Nieves, R.; Ibrahim, J.; Brownell, A.; Soman, P. Bleeding risk associated with transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77 (Suppl. S1), 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohty D, Boulogne C, Magne J, Varroud-Vial N, Martin S, Ettaif H, Fadel BM, Bridoux F, Aboyans V, Damy T, et al. Prognostic value of left atrial function in systemic light-chain amyloidosis: a cardiac magnetic resonance study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016 Sep;17(9):961-9.

- Germain P, Vardazaryan A, Labani A, Padoy N, Roy C, El Ghannudi S. Deep Learning to Classify AL versus ATTR Cardiac Amyloidosis MR Images. Biomedicines. 2023 Jan 12;11(1):193.

- Dobner S, Bernhard B, Ninck L, Wieser M, Bakula A, Wahl A, Köchli V, Spano G, Boscolo Berto M, Elchinova E, et al. Impact of tafamidis on myocardial function and CMR tissue characteristics in transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. ESC Heart Fail. 2024 Oct;11(5):2759-2768.

- Ioannou A, Patel RK, Martinez-Naharro A, Razvi Y, Porcari A, Rauf MU, Bolhuis RE, Fernando-Sayers J, Virsinskaite R, Bandera F, Kotecha T, et albukha. Tracking Treatment Response in Cardiac Light-Chain Amyloidosis With Native T1 Mapping. JAMA Cardiol. 2023 Sep 1;8(9):848-852.

- Bukhari S, Fatima S, Elgendy IY. Cardiogenic shock in the setting of acute myocardial infarction: Another area of sex disparity? World J Cardiol. 2021 Jun 26;13(6):170-176.

- Williams, MC. Improving the Diagnosis of Amyloidosis at Cardiac CT. Radiology. 2023 Mar;306(3):e222406.

- Nacif MS, Kawel N, Lee JJ, Chen X, Yao J, Zavodni A, Sibley CT, Lima JA, Liu S, Bluemke DA. Interstitial myocardial fibrosis assessed as extracellular volume fraction with low-radiation-dose cardiac CT. Radiology. 2012 Sep;264(3):876-83.

- Deux JF, Nouri R, Tacher V, Zaroui A, Derbel H, Sifaoui I, Chevance V, Ridouani F, Galat A, Kharoubi M, et al. Diagnostic Value of Extracellular Volume Quantification and Myocardial Perfusion Analysis at CT in Cardiac Amyloidosis. Radiology. 2021 Aug;300(2):326-335.

- Zimmerman, SL. Strengthening the Case for Cardiac CT in Amyloidosis Evaluation. Radiology. 2021 Aug;300(2):336-337.

- Kidoh M, Oda S, Takashio S, Hirakawa K, Kawano Y, Shiraishi S, Hayashi H, Nakaura T, Nagayama Y, Funama Y, et al. CT Extracellular Volume Fraction versus Myocardium-to-Lumen Signal Ratio for Cardiac Amyloidosis. Radiology. 2023 Mar;306(3):e220542.

- Gillmore JD, Maurer MS, Falk RH, Merlini G, Damy T, Dispenzieri A, Wechalekar AD, Berk JL, Quarta CC, Grogan M, et al. Nonbiopsy Diagnosis of Cardiac Transthyretin Amyloidosis. Circulation. 2016 Jun 14;133(24):2404-12.

- Treglia G, Glaudemans AWJM, Bertagna F, Hazenberg BPC, Erba PA, Giubbini R, Ceriani L, Prior JO, Giovanella L, Slart RHJA. Diagnostic accuracy of bone scintigraphy in the assessment of cardiac transthyretin-related amyloidosis: a bivariate meta-analysis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018 Oct;45(11):1945-1955.

- Stats MA, Stone JR. Varying levels of small microcalcifications and macrophages in ATTR and AL cardiac amyloidosis: implications for utilizing nuclear medicine studies to subtype amyloidosis. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2016 Sep-Oct;25(5):413-7.

- Perugini E, Guidalotti PL, Salvi F, Cooke RM, Pettinato C, Riva L, Leone O, Farsad M, Ciliberti P, Bacchi-Reggiani L et al. Noninvasive etiologic diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis using 99mTc-3,3-diphosphono-1,2-propanodicarboxylic acid scintigraphy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005 Sep 20;46(6):1076-84.

- Nieves RA, Bukhari S, Harinstein ME. Adding value to myocardial perfusion scintigraphy: A prediction tool to predict adverse cardiac outcomes and risk stratify. J Nucl Cardiol. 2021 Oct;28(5):2283-2285.

- Bokhari S, Castaño A, Pozniakoff T, Deslisle S, Latif F, Maurer MS. (99m)Tc-pyrophosphate scintigraphy for differentiating light-chain cardiac amyloidosis from the transthyretin-related familial and senile cardiac amyloidoses. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013 Mar 1;6(2):195-201.

- Masri A, Bukhari S, Ahmad S, Nieves R, Eisele YS, Follansbee W, Brownell A, Wong TC, Schelbert E, Soman P. Efficient 1-Hour Technetium-99 m Pyrophosphate Imaging Protocol for the Diagnosis of Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 Feb;13(2):e010249.

- Bukhari S, Masri A, Ahmad S, Eisele YS, Brownell A, Soman P. Discrepant Tc-99m PYP Planar grade and H/CL ratio: Which correlates better with diffuse tracer uptake on SPECT? Journal of Nuclear Medicine May 2020, 61 (supplement 1) 1633.

- Leguit RJ, Vink A, de Jonge N, Minnema MC, Oerlemans MIF. Endomyocardial biopsy with co-localization of a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and AL amyloidosis. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2021 Jul-Aug;53:107348.

- Musumeci MB, Cappelli F, Russo D, Tini G, Canepa M, Milandri A, Bonfiglioli R, Di Bella G, My F, Luigetti M, et al. Low Sensitivity of Bone Scintigraphy in Detecting Phe64Leu Mutation-Related Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 Jun;13(6):1314-1321.

- Ardehali H, Qasim A, Cappola T, Howard D, Hruban R, Hare JM, Baughman KL, Kasper EK. Endomyocardial biopsy plays a role in diagnosing patients with unexplained cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J. 2004 May;147(5):919-23.

- Holzmann M, Nicko A, Kühl U, Noutsias M, Poller W, Hoffmann W, Morguet A, Witzenbichler B, Tschöpe C, Schultheiss HP, et al. Complication rate of right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy via the femoral approach: a retrospective and prospective study analyzing 3048 diagnostic procedures over an 11-year period. Circulation. 2008 Oct 21;118(17):1722-8.

- Guy CD, Jones CK. Abdominal fat pad aspiration biopsy for tissue confirmation of systemic amyloidosis: specificity, positive predictive value, and diagnostic pitfalls. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001 Mar;24(3):181-5.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).