Submitted:

04 July 2024

Posted:

05 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

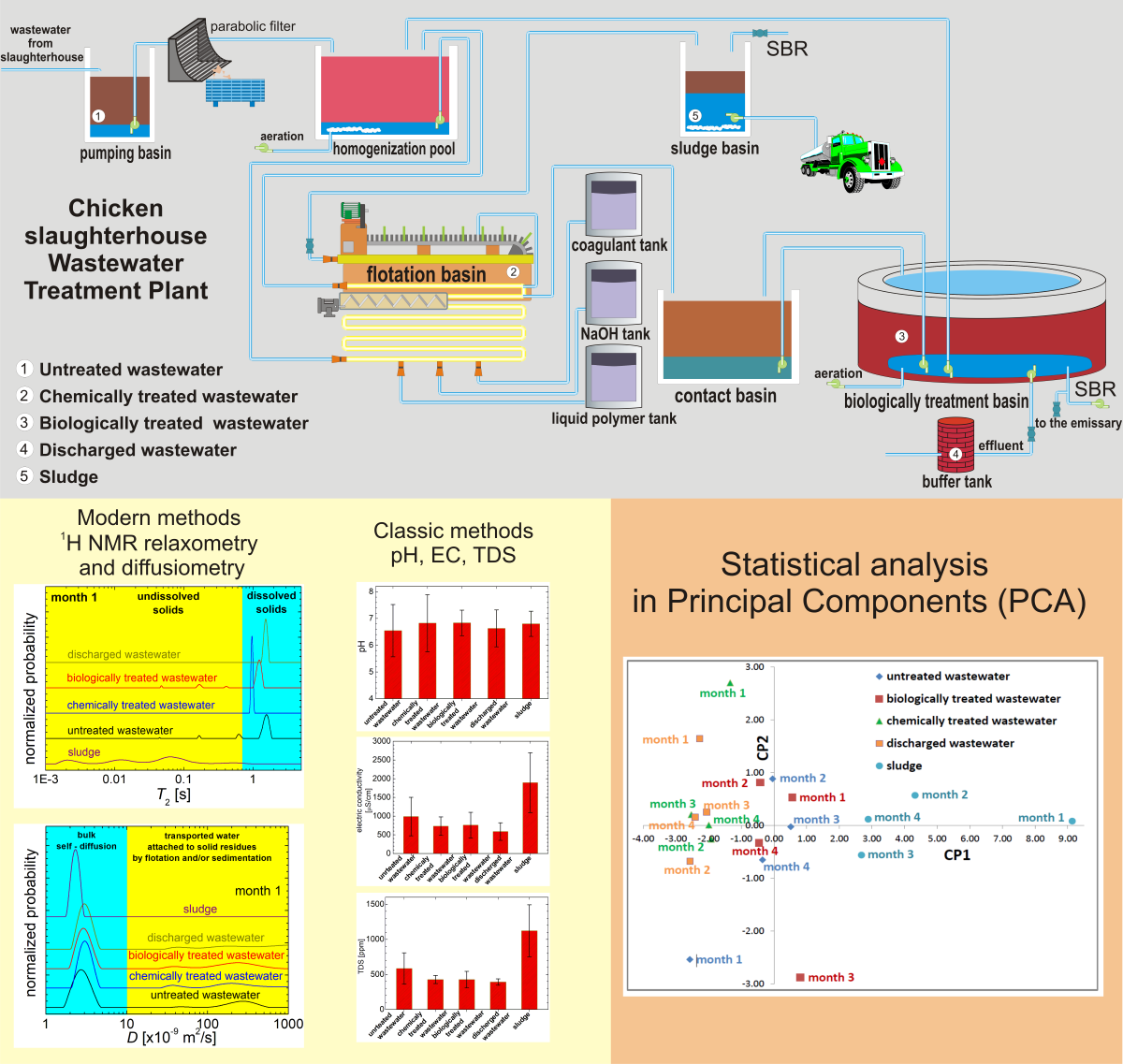

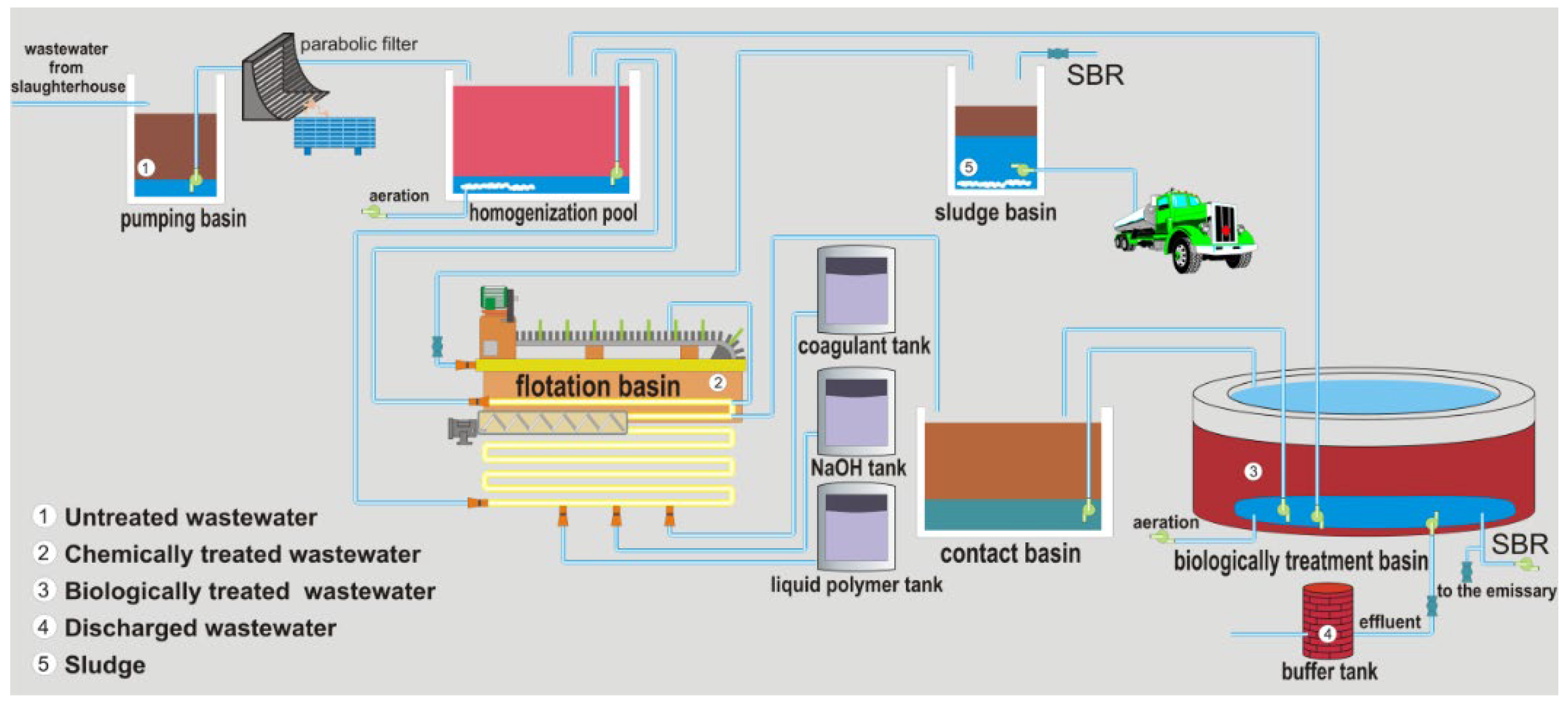

2.1. Materials and Processes in the Slaughterhouse Wastewater Purification Treatment

2.2. Methods

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

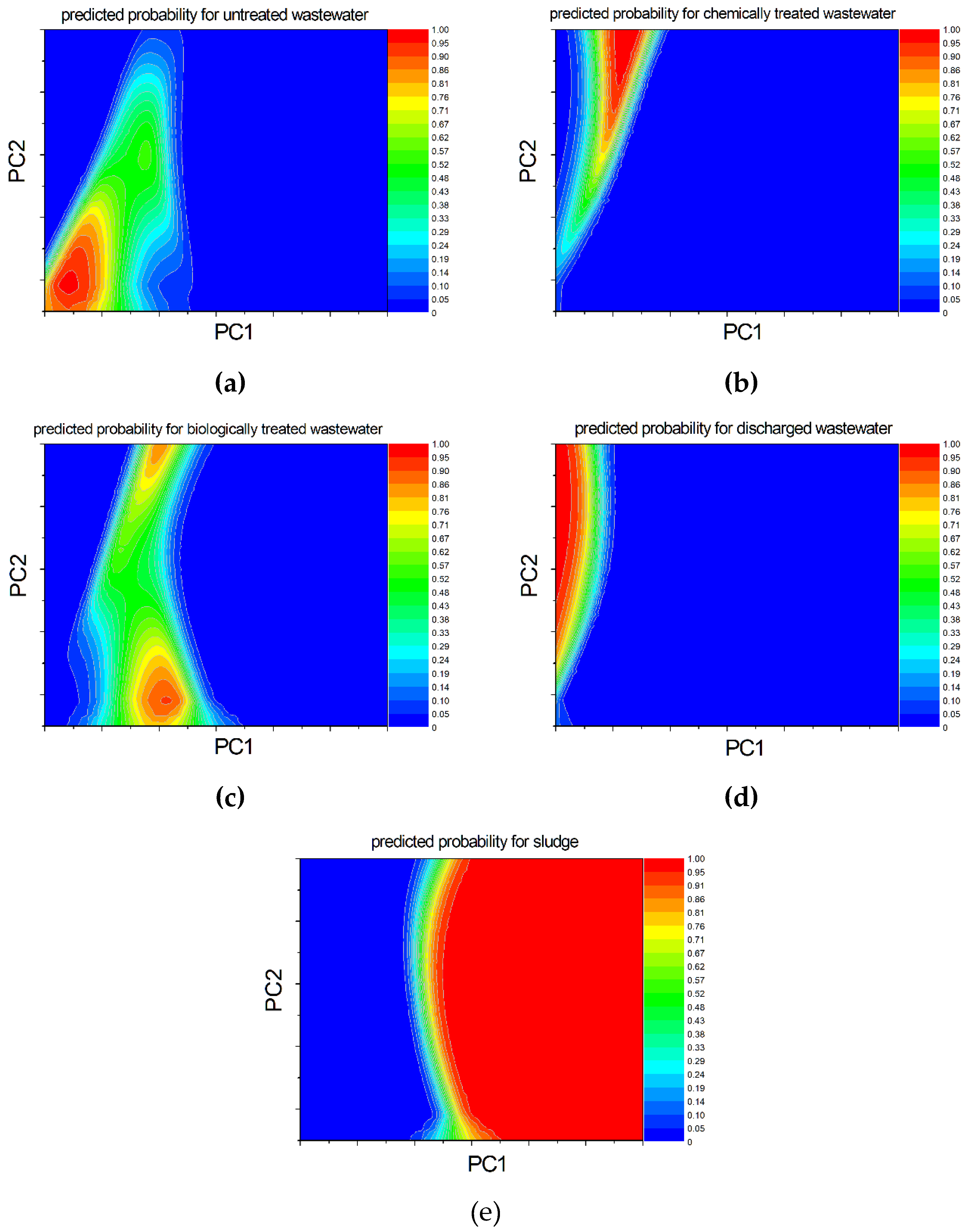

2.5. Prediction Using Machine Learning ML5, an AI-Based Algorithm

3. Results

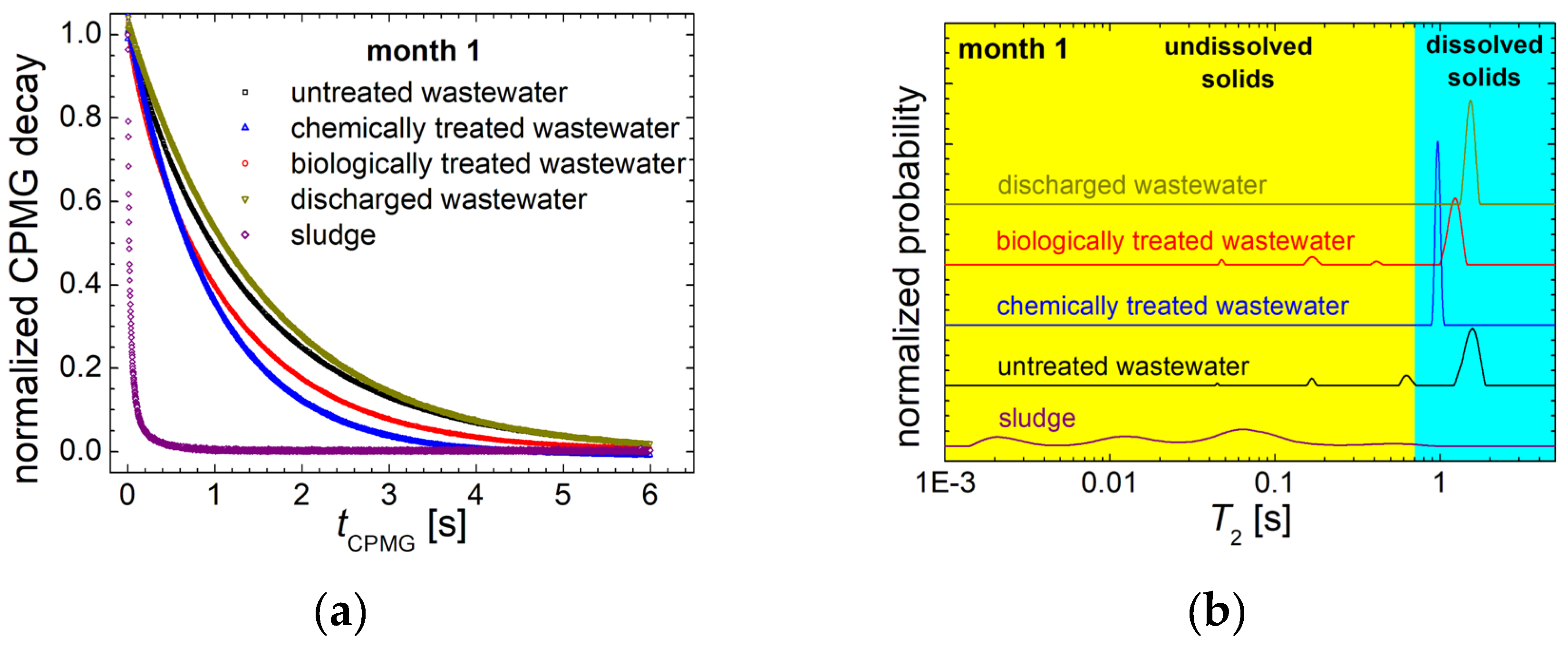

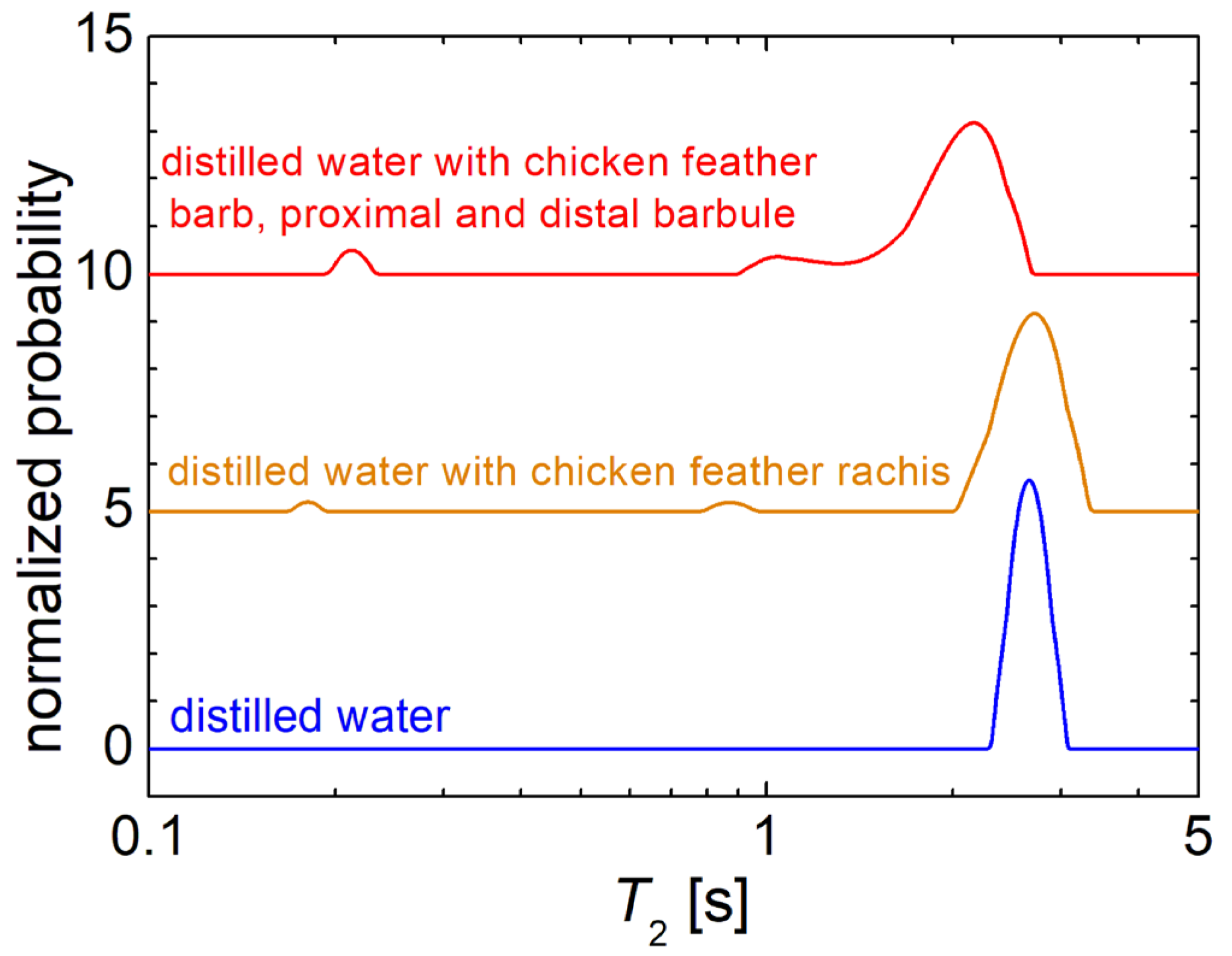

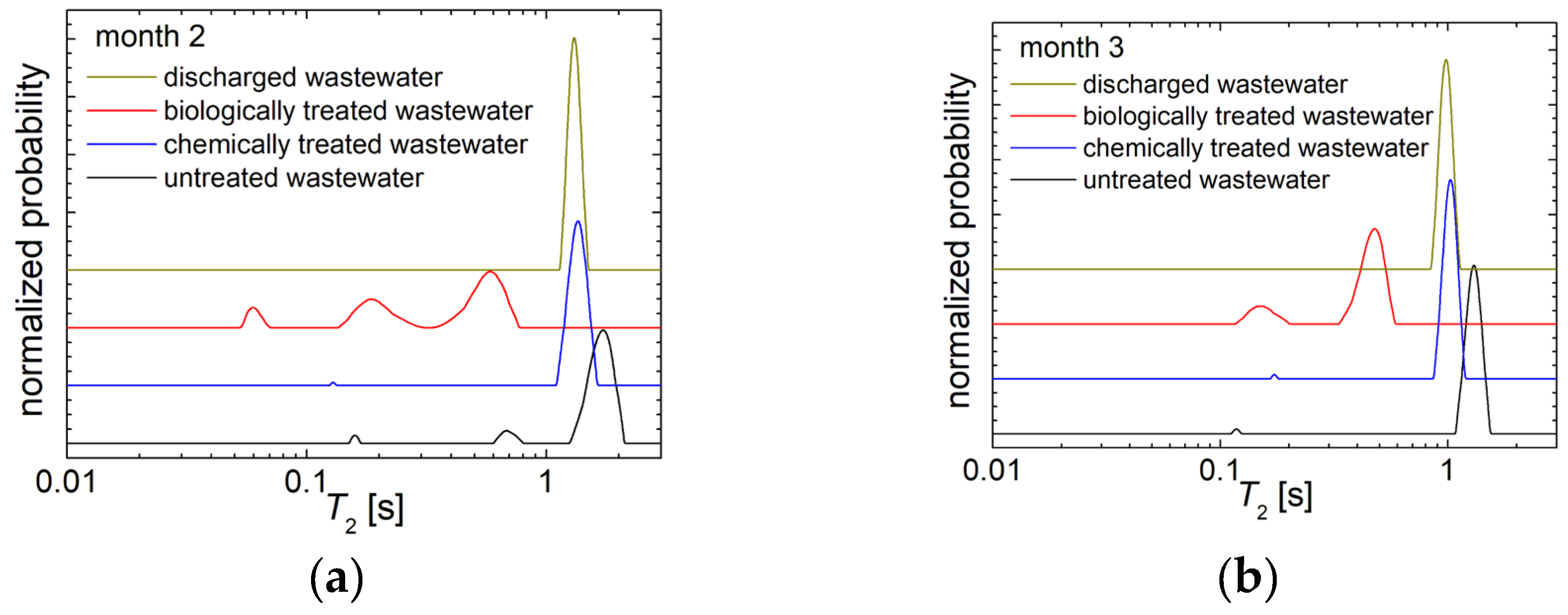

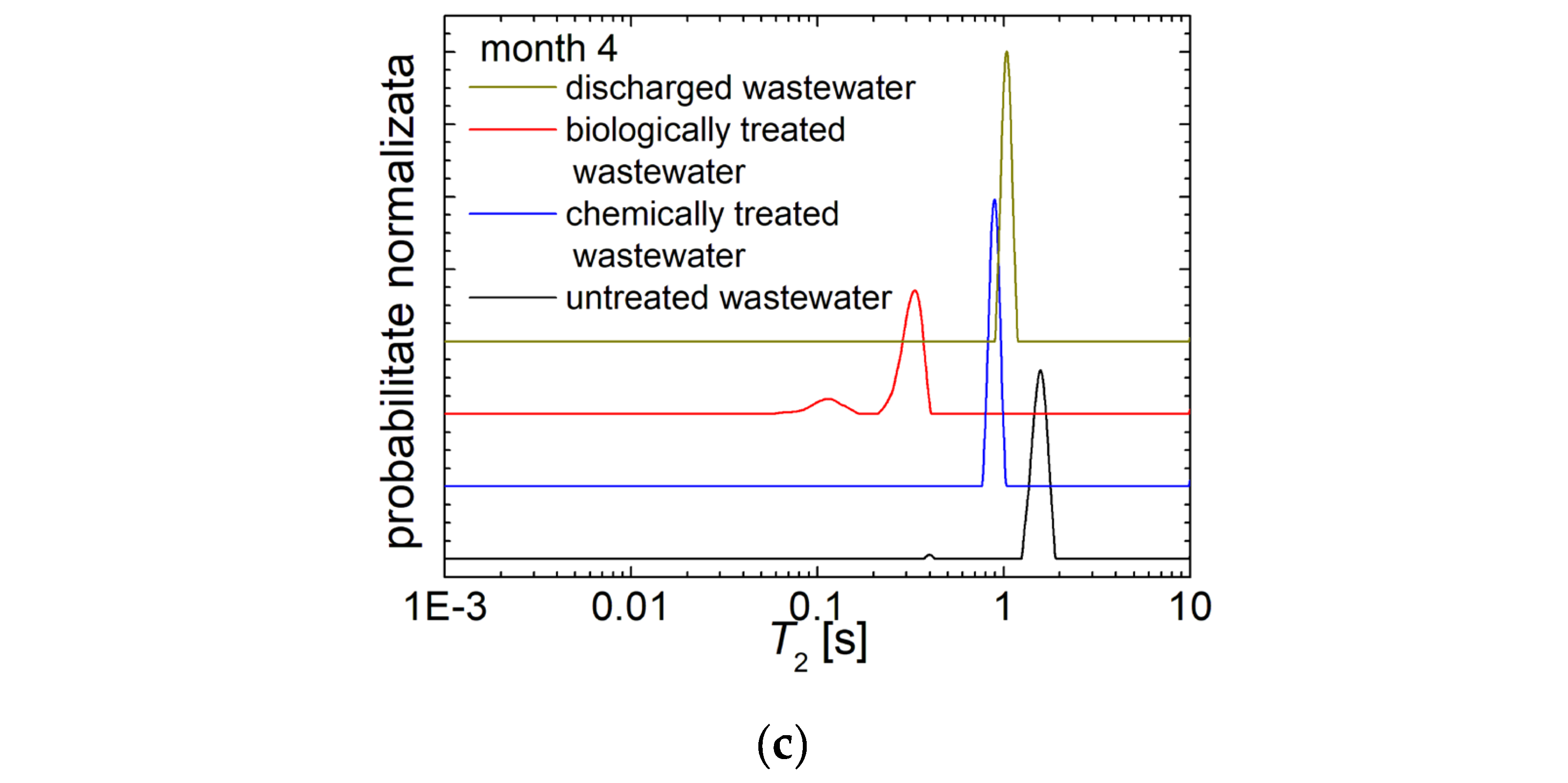

3.1. 1H NMR Relaxometry of Wastewater and of Sludge from the Chicken Slaughterhouse

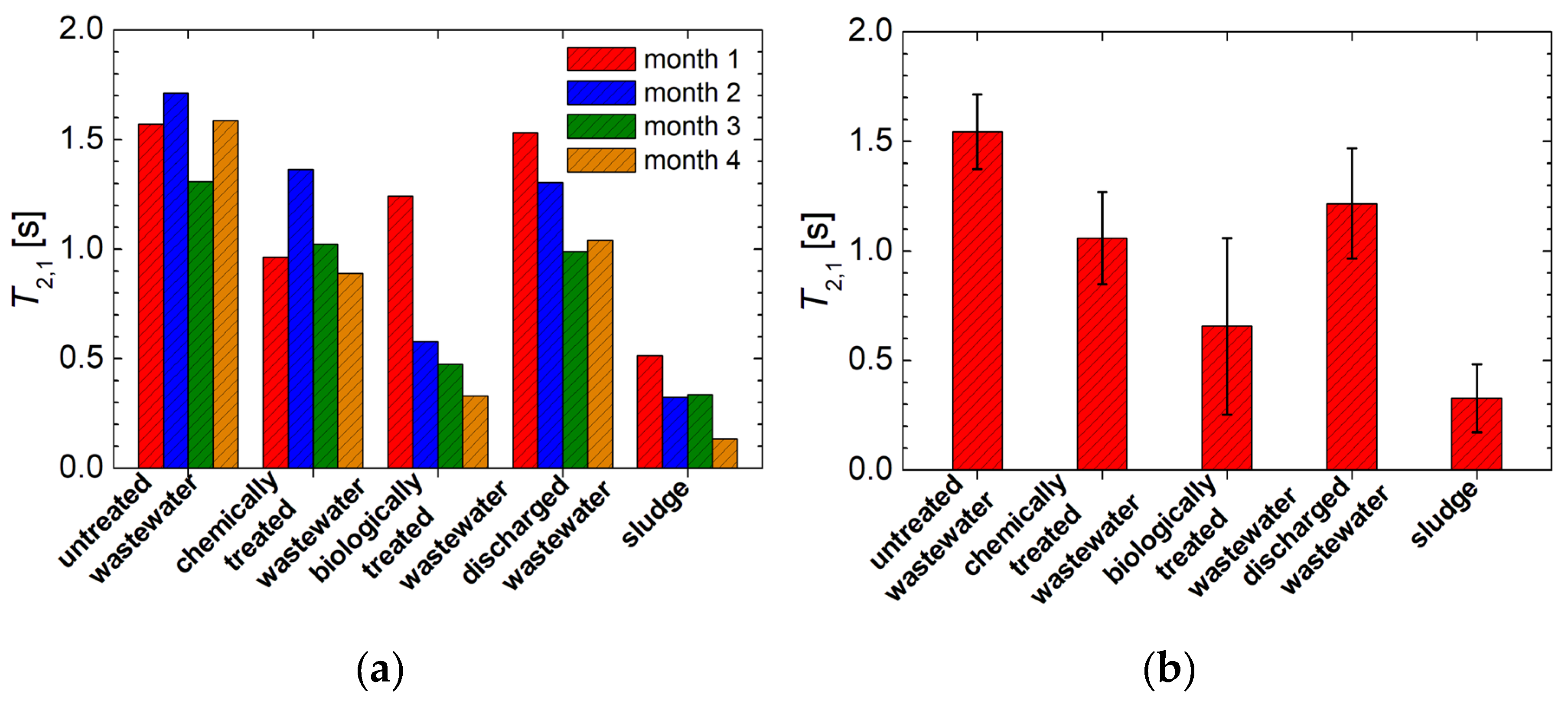

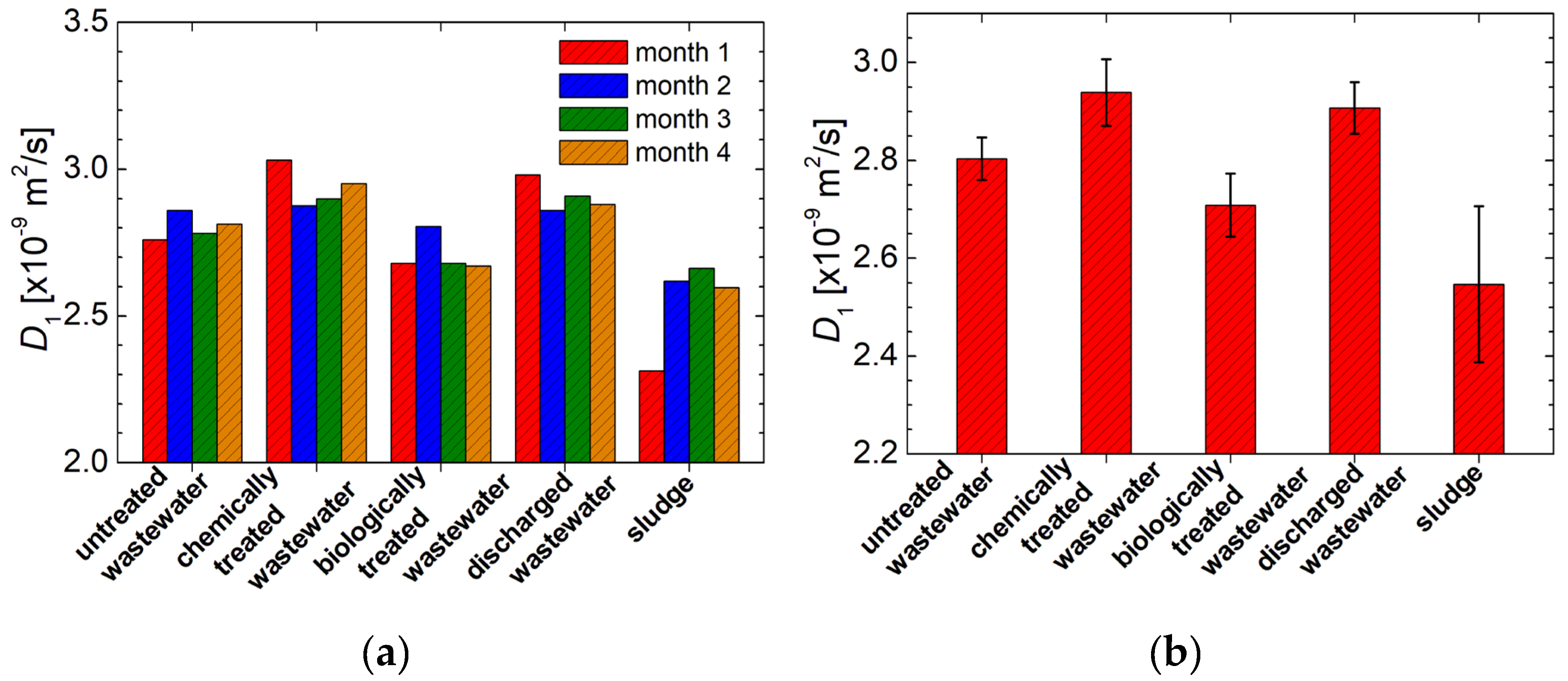

3.2. 1H NMR Diffusometry of Wastewater and Sludge from Chicken Slaughterhouse

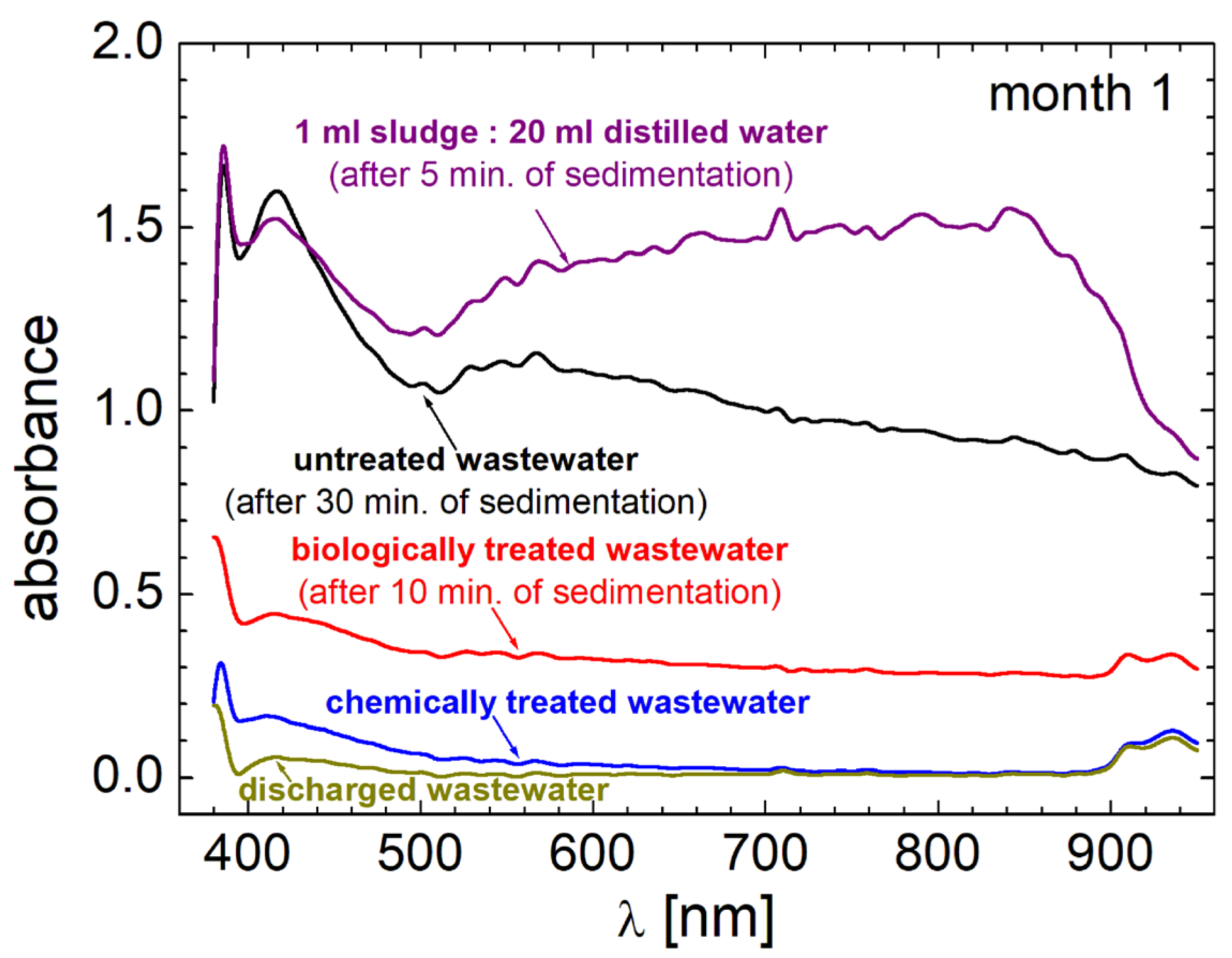

3.3. VIS-NearIR Spectroscopy

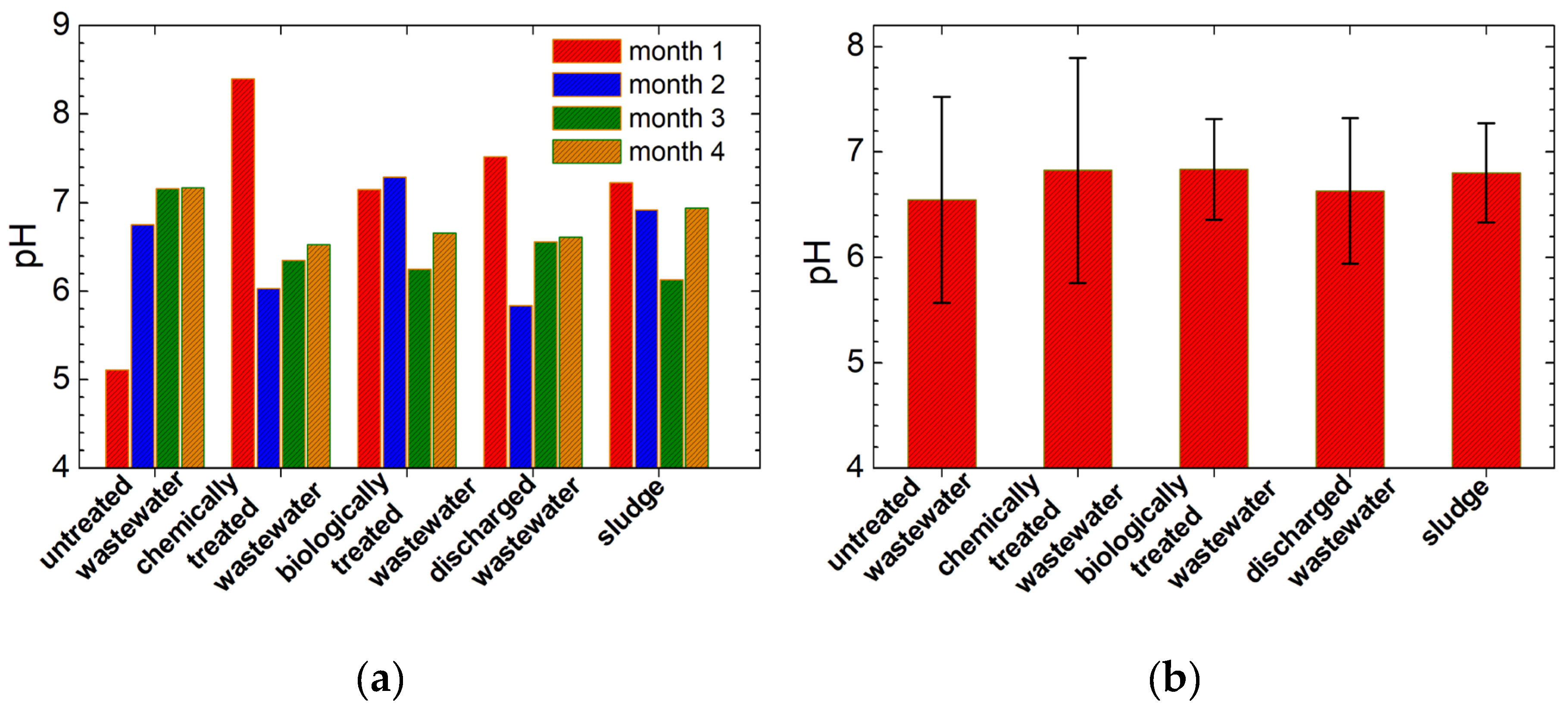

3.4. The pH Measurements

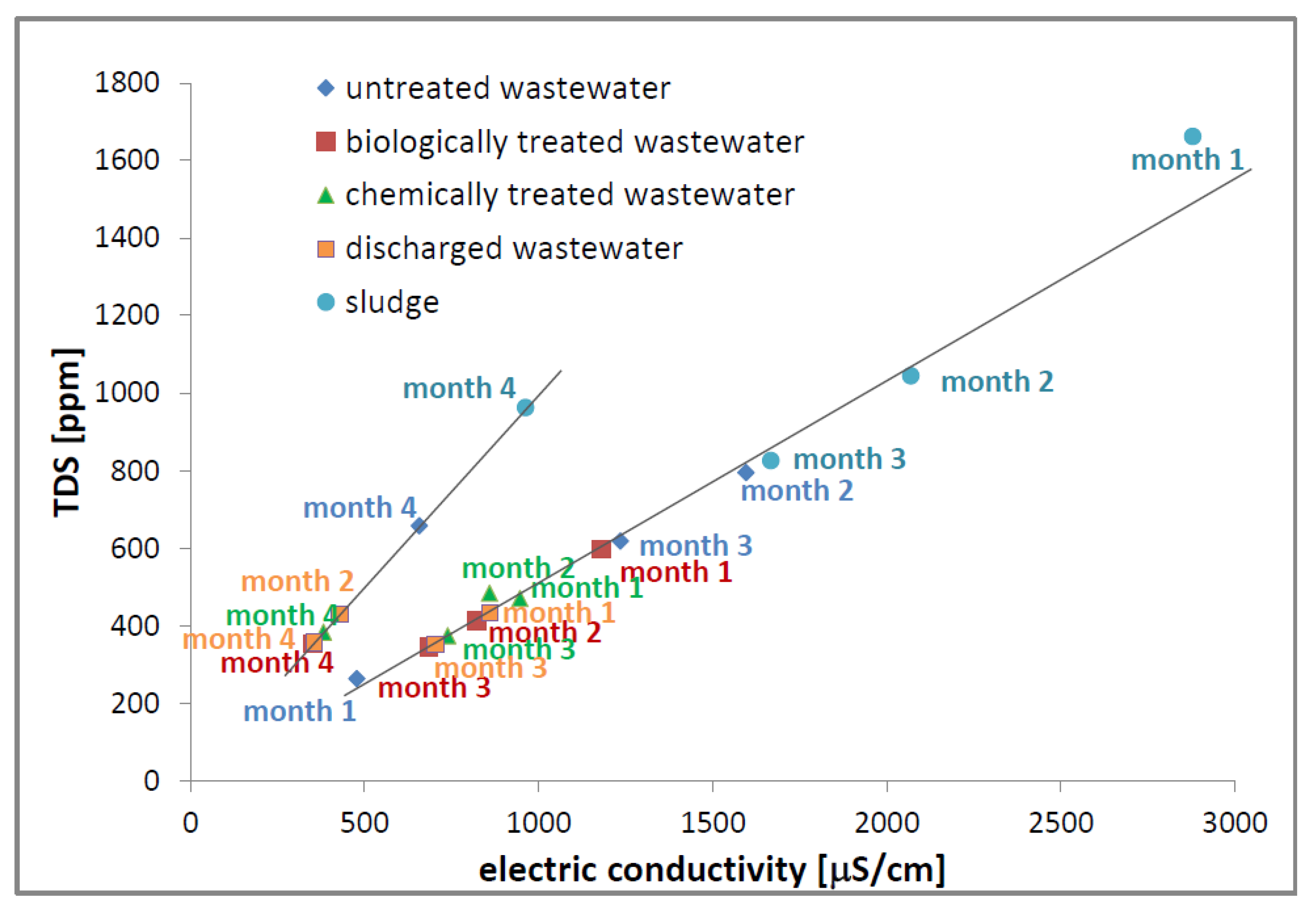

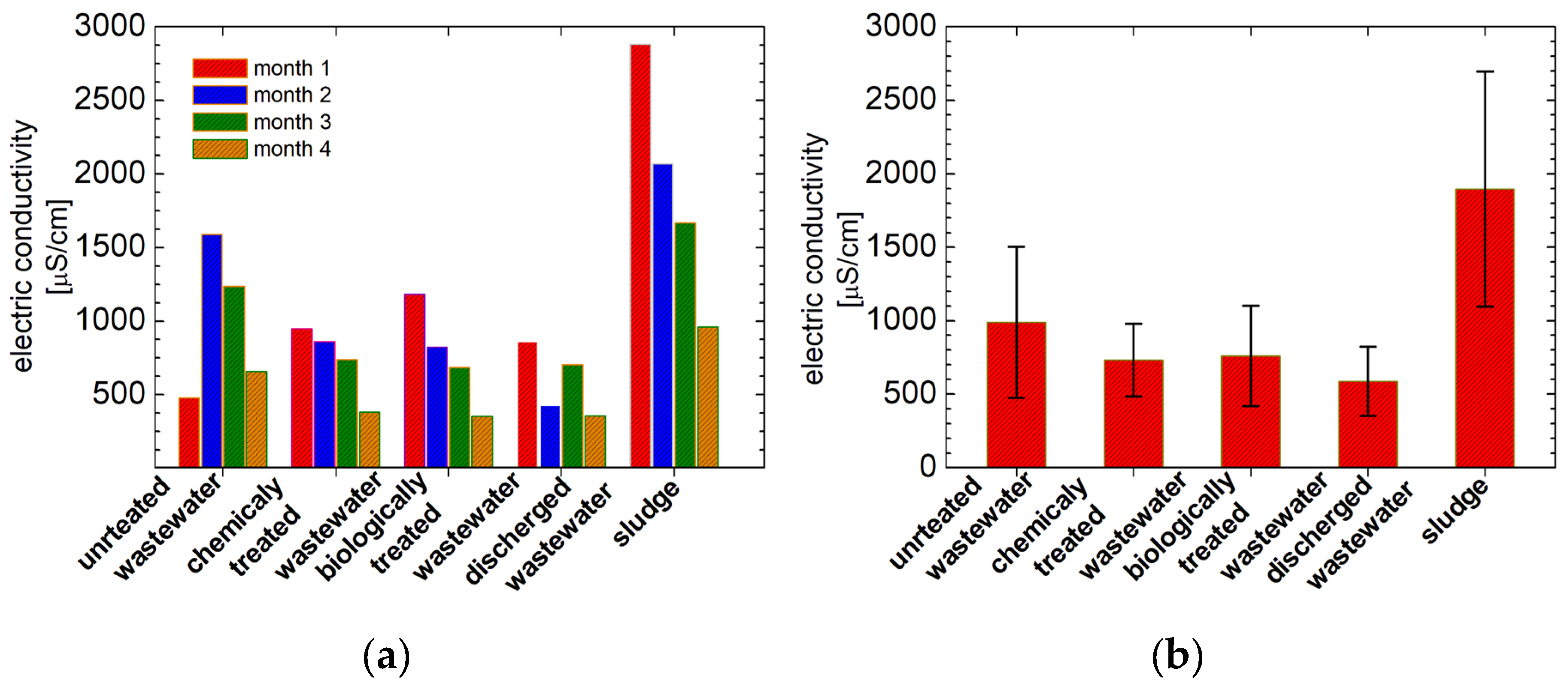

3.5. Electric Conductivity Measurements

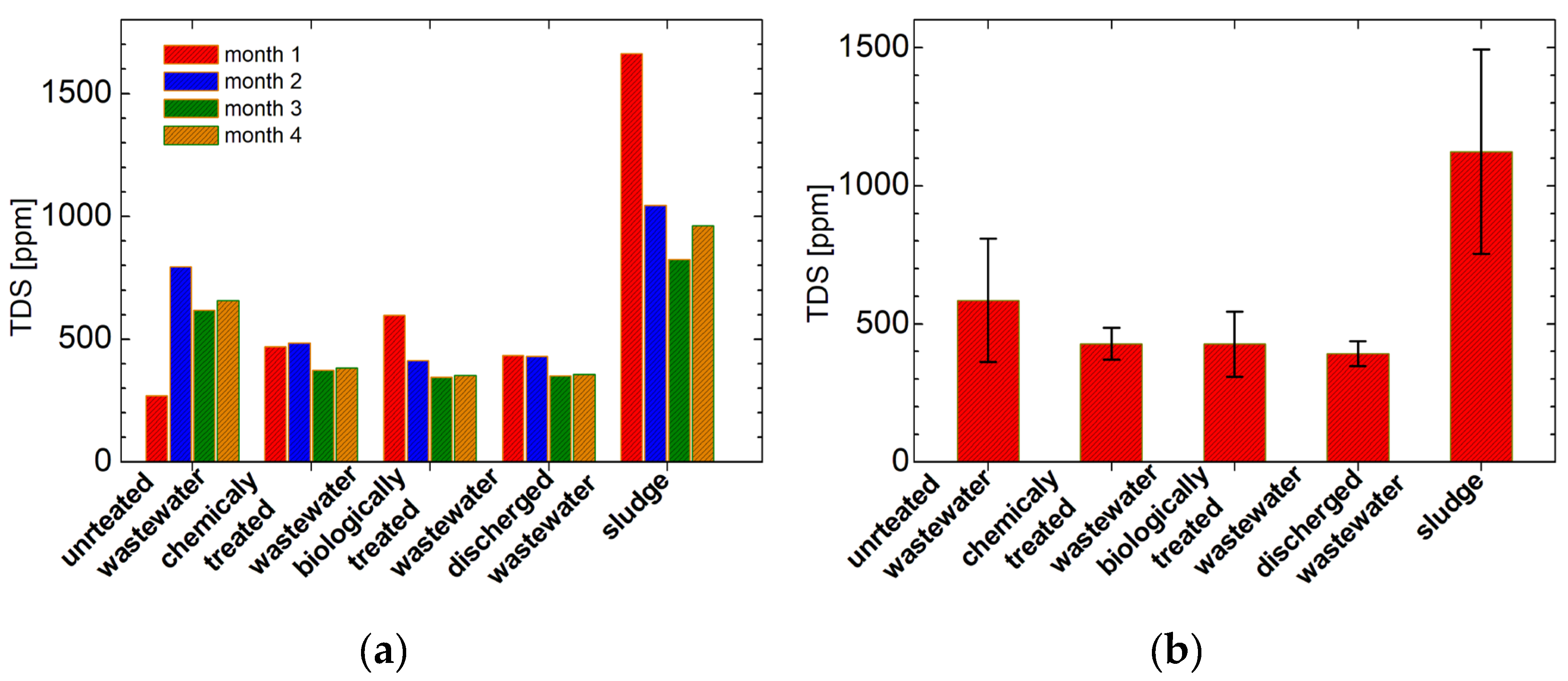

3.6. Total Dissolved Solids Measurements

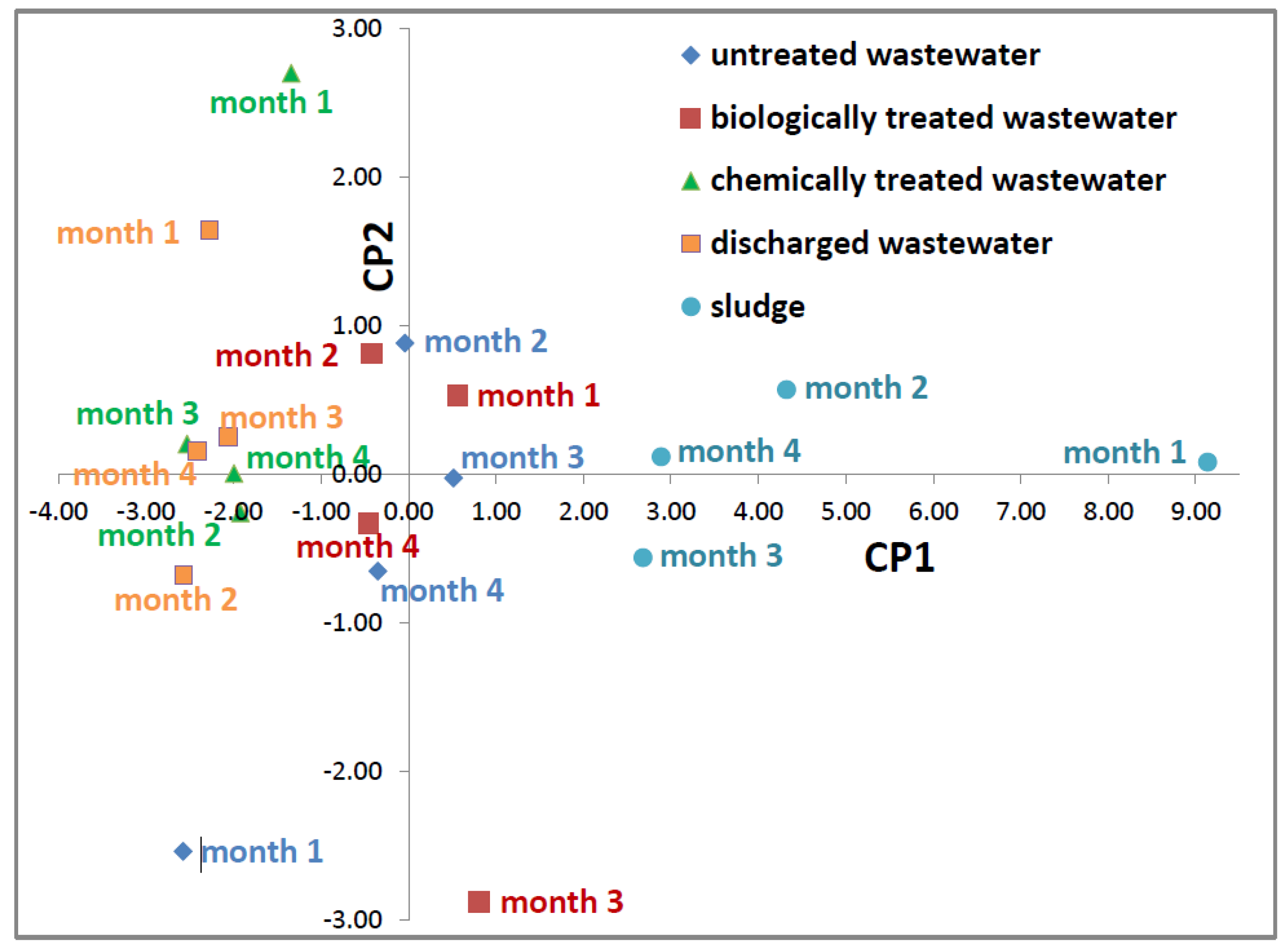

3.7. Principal Component Analysis

| wastewater | month | Total VIS-nearIR absorbance |

T2,1 [s] |

D1 [10-9 m2/s] |

pH [–] |

EC [μS/cm] |

TDS [ppm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| untreated wastewater | 1 | 1.06* | 1.57 | 2.76 | 5.11 | 478 | 263 |

| 2 | 0.14 | 1.71 | 2.86 | 6.75 | 1596 | 795 | |

| 3 | 1.401* | 1.31 | 2.78 | 7.16 | 1236 | 618 | |

| 4 | 2.13* | 1.59 | 2.81 | 7.17 | 658 | 658 | |

| chemically treated wastewater | 1 | 0.06 | 0.96 | 3.03 | 8.4 | 947 | 470 |

| 2 | 0.04 | 1.36 | 2.88 | 6.03 | 860 | 484 | |

| 3 | 0.05 | 1.02 | 2.90 | 6.35 | 740 | 374 | |

| 4 | 0.02 | 0.89 | 2.95 | 6.53 | 383 | 383 | |

| biologically treated wastewater | 1 | 0.33** | 1.24 | 2.68 | 7.15 | 1182 | 597 |

| 2 | 0.14** | 0.58 | 2.81 | 7.29 | 822 | 412 | |

| 3 | 2.99** | 0.47 | 2.68 | 6.25 | 686 | 344 | |

| 4 | 0.04** | 0.33 | 2.67 | 6.66 | 353 | 353 | |

| discharged wastewater | 1 | 0.02 | 1.53 | 2.98 | 7.52 | 860 | 433 |

| 2 | 0.02 | 1.30 | 2.86 | 5.84 | 429 | 429 | |

| 3 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 2.91 | 6.56 | 704 | 352 | |

| 4 | 0.002 | 1.04 | 2.88 | 6.61 | 356 | 356 | |

| Sludge | 1 | 1.39*** | 0.52 | 2.31 | 7.23 | 2880 | 1662 |

| 2 | 0.33*** | 0.32 | 2.62 | 6.92 | 2070 | 1045 | |

| 3 | 0.43*** | 0.34 | 2.66 | 6.13 | 1668 | 826 | |

| 4 | 0.32*** | 0.14 | 2.60 | 6.94 | 963 | 963 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paulista, L.O.; Presumido, P.H.; Peruço Theodoro, J.D.; Novaes Pinheiro, A.L. Efficiency analysis of the electrocoagulation and electroflotation treatment of poultry slaughterhouse wastewater using aluminum and graphite anodes. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res. 2018, 25, 19790–19800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aceves-Lara, C.-A.; Latrille, E.; Conte, T.; Steye, J.-P. Online estimation of VFA, alkalinity and bicarbonateconcentrations by electrical conductivity measurementduring anaerobic fermentation. Water Sci. Technol. 2012, 65, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M.S.; Azwan, A.M.; Zamri, M.F.M.A.; Aziz, H.A. Removal of colour, turbidity, oil and grease for slaughterhouse wastewater using electrocoagulation method. AIP Conf. Proc. 2017, 1892, 040012-1–040012-7. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, V.K. pH measurement of dirty water sources by ISFET: addressing practical problems. Sensor Review 2007, 27, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modla, M. The easy guide to pH measurement. Meas. Control 2004, 37, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, F.M.; Yuan, Q. Nitrite interference with soluble COD measurements from aerobically treated wastewater. Water Environ. Res. 2017, 89, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 22nd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Boughou, N.; Majdy, I.; Cherkaoui, E.; Khamar, M.; Nounah, A. Physico-chemical characterization of wastewater from slaughterhouse: Case of rabat in Morocco. ARPN J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2018, 13, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Crainic, R.; Drăgan, L.R.; Fechete, R. 1H NMR relaxometry and ATR-FT-IR spectrosopy used for the assesment of wastewater treatment in slaughterhouse. Studia UBB Phys. 2018, 63, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seif, H.; Moursy, A. Treatment of slaughterhouse wastes. In Sicth international water conference; IWTC: Alexandria, Egypt, 2001; pp. 270–271. [Google Scholar]

- Alayu, E.; Yirgu, Z. Advanced technologies for the treatment of wastewaters from agro-processing industries and cogeneration of by-products: a case of slaughterhouse, dairy and beverage industries. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 15, 1581–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Maldonado, E.A.; Oropeza-Guzman, M.T.; Jurado-Baizaval, J.L.; Ochoa-Terán, A. Coagulation–flocculation mechanisms in wastewater treatment plants through zeta potential measurements. J. Hazard. Mat. 2014, 279, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K.; Rehman, S.K.U.; Wang, J.; Farooq, F.; Mahmood, Q.; Jadoon, A.M.; Javed, M.F.; Ahmad, I. Treatment of Pulp and Paper Industrial Euent Using Physicochemical Process for Recycling. Water 2019, 11, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, H.; Golestani, H.A.; Mousavi, S.M.; Zhiani, R.; Hosseini, M.S. Slaughterhouse wastewater treatment using biological anaerobic and coagulation-flocculation hybrid process. Desal. Wat. Treat. 2019, 155, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridis, N.K.; Matis, K.A.; Webb, M. Flotation of metal-loaded clayanion exchangers. Part I: the case of chromate. Chemosphere 2001, 42, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, F.M.; Liu, Z.D. The effect of triethylenetraamine (trien) on the ion flotation of Cu2+ and Ni2+. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 258, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandegar, V.; Saroha, A.K. Electrocoagulation for the treatment of textile industry effluent e A review. J. Env. Management 2013, 128, 949–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozturk, D.; Yilmaz, A.E. Treatment of slaughterhouse wastewater with the electrochemical oxidation process: Role of operating parameters on treatment efficiency and energy consumption. J. Water Proc. Eng. 2019, 31, 100834-1–100834-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tünay, O.; Kabdasli, N.I. Hydroxide precipitation of complexed metals. Water Res. 1994, 28, 2117–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrus, M.E. A review of metal precipitation chemicals for metal-finishing applications. Metal Finish. 2000, 98, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Qu, R.; Shi, J.; Li, D.; Wei, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z. Heavy metal and phosphorus removal from water by optimizing use of calcium hydroxide and risk assessment. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 1, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, Z.; Rui, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Z. A Review on Reverse Osmosis and Nanofiltration Membranes for Water Purification. Polymers 2019, 11, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacıfazlıoğlu, M.C.; Parlar, I.; Pek, T.Ö.; Kabay, N. Evaluation of chemical cleaning to control fouling on nanofiltration and reverse osmosis membranes after desalination of MBR effluent. Desalination 2019, 466, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, H.A.; Puat, N.N.A.; Alazaiza, M.Y.D.; Hung, Y.T. Poultry Slaughterhouse Wastewater Treatment Using Submerged Fibers in an Attached Growth Sequential Batch Reactor. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fechete, R.; Demco, D.E.; Blümich, B. Segmental Anisotropy in Strained Elastomers by 1H NMR of Multipolar Spin States. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 6083–6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechete, R.; Demco, D.E.; Blümich, B. Enhanced sensitivity to residual dipolar couplings by high-order multiple-quantum NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 2004, 169, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldovan, D.; Fechete, R.; Demco, D.E.; Culea, E.; Blümich, B.; Herrmann, V.; Heinz, M. Heterogeneity of Nanofilled EPDM Elastomers Investigated by Inverse Laplace Transform 1H NMR Relaxometry and Rheometry. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2010, 211, 1579–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, D.; Fechete, R.; Demco, D.E.; Culea, E.; Blümich, B.; Herrmann, V.; Heinz, M. The heterogeneity of segmental dynamics of filled EPDM by 1H transverse relaxation NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 2011, 208, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechete, R.; Demco, D.E.; Blümich, B. Order parameters of orientation distributions of collagen fibers in tendon by Multipolar spin states filtered NMR signals. NMR in Biomedicine 2003, 16, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fechete, R.; Demco, D.E.; Blümich, B.; Eliav, U.; Navon, G. Self-diffusion anisotropy of water in sheep Achilles tendon. NMR in Biomedicine 2005, 18, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, R.S.; Fechete, R.; Moldovan, D.; Sus, I.; Szasz, S.; Pávai, Z. Assessment of femoral bone osteoporosis in rats treated with simvastatin or fenofibrate. Open Life Sci. 2015, 10, 379–387. [Google Scholar]

- Sipos, R.S.; Fechete, R.; Chelcea, R.I.; Moldovan, D.; Pap, Z.; Pávai, Z.; Demco, D.E. Ovariectomized rats’ femur treated with fibrates and statins. Assessment of pore-size distribution by 1H-NMR relaxometry. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2015, 56, 743–752. [Google Scholar]

- Chelcea, R.I.; Sipos, R.S.; Fechete, R.; Moldovan, D.; Sus, I.; Pávai, Z.; Decmo, D.E. One-Dimensional Laplace Spectroscopy Used For The Assessment Of Pore-Size Distribution On The Ovariectomized Rats Femur. STUDIA UBB CHEMIA 2015, LX, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sipos, R.S.; Fechete, R.; Moldovan, D.; Sus, I.; Pávai, Z.; Demco, D.E. Ovariectomy-Induced Osteoporosis Evaluated by 1H One-and Two-Dimensional NMR Transverse Relaxometry. App. Magn. Reson. 2016, 47, 1419–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumbu, A.V.; Fechete, R.; Perian, M.; Bumbu, B.S.; Brinzaniuc, K. Sciatic Nerve Regeneration in Wistar Albino Rats Evaluated by in vivo Conductivity and in vitro 1H NMR Relaxometry. Acta Medica Marisiensis 2018, 64, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baias, M.; Demco, D.E.; Popescu, C.; Fechete, R.; Melian, C.; Blümich, B.; Möller, M. Thermal Denaturation of Hydrated Wool Keratin by 1H Solid-State NMR. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 2184–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melian, C.; Demco, D.E.; Istrate, M.; Balaceanu, A.; Moldovan, D.; Fechete, R.; Popescu, C.; Blümich, B.; Möller, M. Morphology and side chain dynamics in hydrated hard α-keratin fibres by 1H solid-state NMR. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009, 480, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipoi, C.; Demco, D.E.; Zhu, X.; Vinokur, R.; Conradi, O.; Fechete, R.; Möller, M. Water self-diffusion anisotropy and electrical conductivity of perfluorosulfonic acid/SiO2 composite proton exchange membranes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2012, 554, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechete, R.; Demco, D.E.; Zhu, X.; Tillmann, W.; Vinokur, R.; Möller, M. Water states and dynamics in perfluorinated ionomer proton exchange membranes by 1H one- and two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy, relaxometry, and diffusometry. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2014, 597, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioica, N.; Fechete, R.; Cota, C.; Nagy, E.M.; David, L.; Cozar, O. NMR relaxation investigation of the native corn starch structure with plasticizers. J. Molec. Struct. 2013, 1044, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioica, N.; Fechete, R.; Filip, C.; Cozar, I.B.; Cota, C.; Nagy, E.M. NMR and SEM Investigation of Extruded Native Corn Starch with Plasticizers. Rom. J. Phys. 2015, 60, 512–520. [Google Scholar]

- Jumate, E.; Moldovan, D.; Manea, D.L.; Demco, D.E.; Fechete, R. The Effects of Cellulose Ethers and Limestone Fillers in Portland Cement-Based Mortars by 1H NMR relaxometry. App. Magn. Reson. 2016, 47, 1353–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumate, E.; Manea, D.L.; Moldovan, D.; Fechete, R. The Effects of Hydrophobic Redispersibele Powder Polymer in Portland Cement Based Mortars. Proc. Eng. 2017, 181, 316–323. [Google Scholar]

- Dávid, R.E.; Fechete, R.; Sfrângeu, S.; Moldovan, D.; Chelcea, R.I.; Morar, I.A.; Stamatian, F.; Kovacs, T.; Popoi, P. In Vivo 1H Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy and Relaxometry Maps of the Human Female Pelvis. Anal. Lett. 2019, 52, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gussoni, M.; Greco, F.; Vezzoli, A.; Paleari, M.A.; Moretti, V.M.; Lanza, B.; Zetta, L. Osmotic and aging effects in caviar oocytes throughout water and lipid changes assessed by 1H NMR T1 and T2 relaxation and MRI. Magn. Reson. Imag. 2007, 25, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Zhou, K.; He, Y.; Chai, X.; Dai, X. Unraveling the water states of waste-activated sludge through transverse spin-spin relaxation time of low-field NMR. Water Res. 2019, 155, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fechete, R.; Morar, I.A.; Moldovan, D.; Chelcea, R.I.; Crainic, R.; Nicoara, S.C. Fourier and Laplace-like low-field NMR spectroscopy: The perspectives of multivariate and artificial neural networks analyses. J. Magn. Reson. 2021, 324, 106915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkataramanan, L.; Song, Y.Q.; Hürlimann, M.D. Solving Fredholm integrals of the first kind with tensor product structure in 2 and 2.5 dimensions. IEEE Trans. Sign. Proc. 2002, 50, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.Q.; Venkataramanan, L.; Hürlimann, M.D.; Flaum, M.; Frulla, P.; Straley, C. T1–T2 correlation spectra obtained using a fast two-dimensional Laplace inversion. J. Magn. Reson. 2002, 154, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hürlimann, M.D.; Flaum, M.; Venkataramanan, L.; Flaum, C.; Freedman, R.; Hirasaki, G.J. Diffusion-relaxation distribution functions of sedimentary rocks in different saturation states. Magn. Reson. Imag. 2003, 21, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechete, R.; Demco, D.E.; Blümich, B. Parameter maps of 1H residual dipolar couplings in tendon under mechanical load. J. Magn. Reson. 2003, 165, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aursand, I.G.; Veliyulin, E.; Böcker, U.; Ofstad, R.; Rustad, T.; Erikson, U. Water and salt distribution in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) studied by low-field 1H NMR, 1H and 23Na MRI and light microscopy: effects of raw material quality and brine salting. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 57, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Song, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Tan, M. Approach for monitoring the dynamic states of water in shrimp during drying process with LF-NMR and MRI. Dry. Technol. 2018, 36, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, C.D.S.; Mársico, E.T.; Ribeiro, R.D.O.R.; Conte Júnior, C.A.; Álvares, T.S.; De Jesus, E.F.O. Quality attributes in shrimp treated with polyphosphate after thawing and cooking: a study using physicochemical analytical methods and Low-Field 1H NMR. J. Food Process. Eng. 2013, 36, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, A.; May, S.; Clark, V.A. Practical Multivariate Analysis, 5th editionCRC Press; Taylor and Francis Group, 2012; pp. 357–379. [Google Scholar]

- Dragan, L.R.; Andras, D.; Fechete, R. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy and Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H NMR) Relaxometry and Diffusometry for the Identification of Colorectal Cancer in Blood Plasma. Analytical Letters 2023, 56, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffman, D. The Nature of Code. Simulating the natural systems with Processing, Generated by Magic Book Project, 2012.

- Shiffman, D. The Nature of Code. Simulating the natural systems with Javascript, Ed. No Starch Press, 2024.

| parameter | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | PC6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

total VIS-nearIR absorbance |

0.336 | -0.627 | 0.550 | 0.430 | -0.079 | -0.025 |

| T2,1 [s] | -0.561 | 0.054 | 0.703 | -0.417 | 0.117 | 0.026 |

| D1 [10-9 m2/s] | -0.892 | 0.343 | 0.122 | 0.036 | -0.244 | -0.104 |

| pH | 0.250 | 0.794 | 0.264 | 0.478 | 0.085 | 0.032 |

| EC [μS/cm] | 0.884 | 0.220 | 0.173 | -0.288 | -0.211 | 0.118 |

| TDS [ppm] | 0.933 | 0.165 | 0.107 | -0.226 | 0.042 | -0.195 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).