Submitted:

04 July 2024

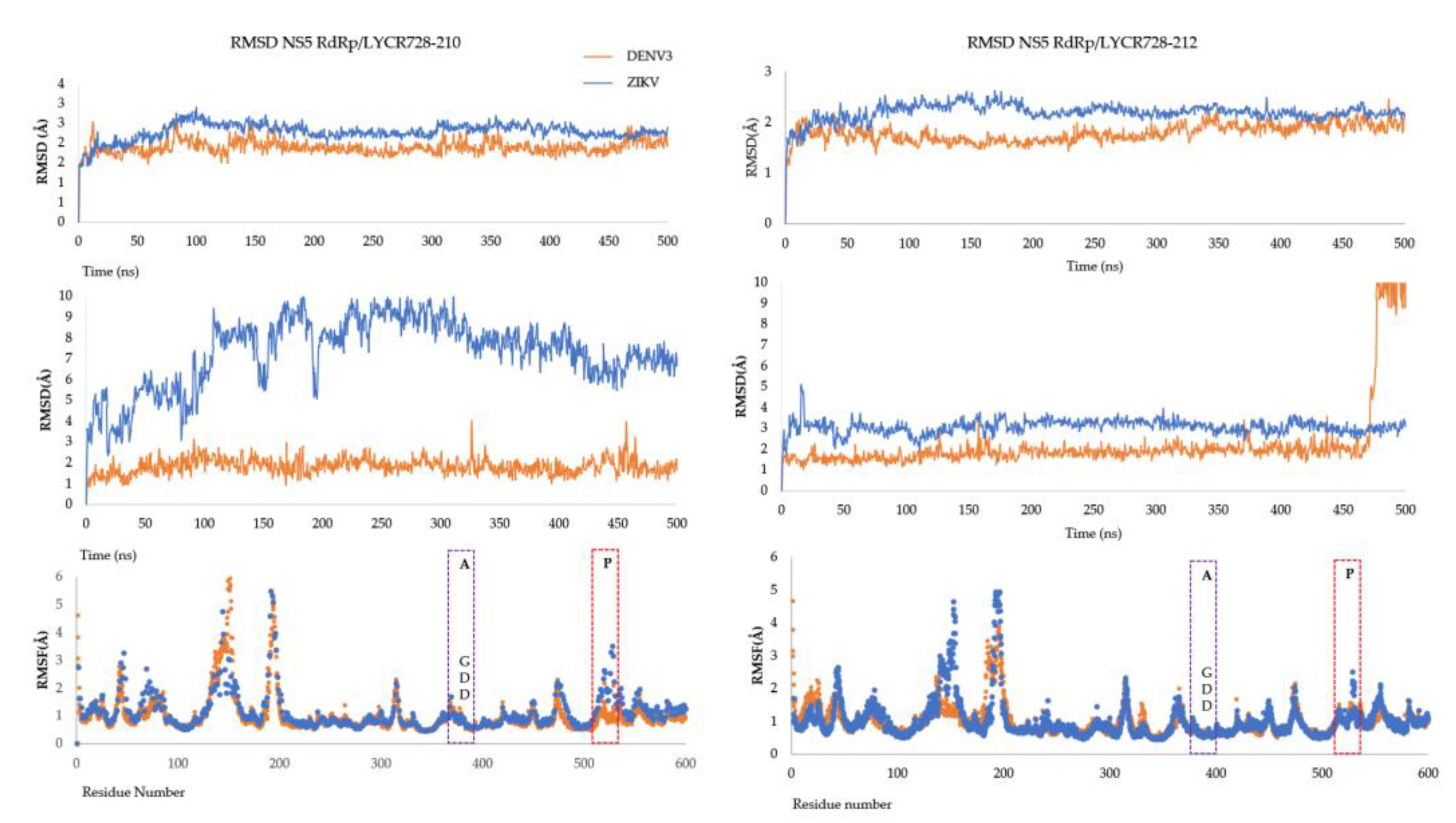

Posted:

05 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

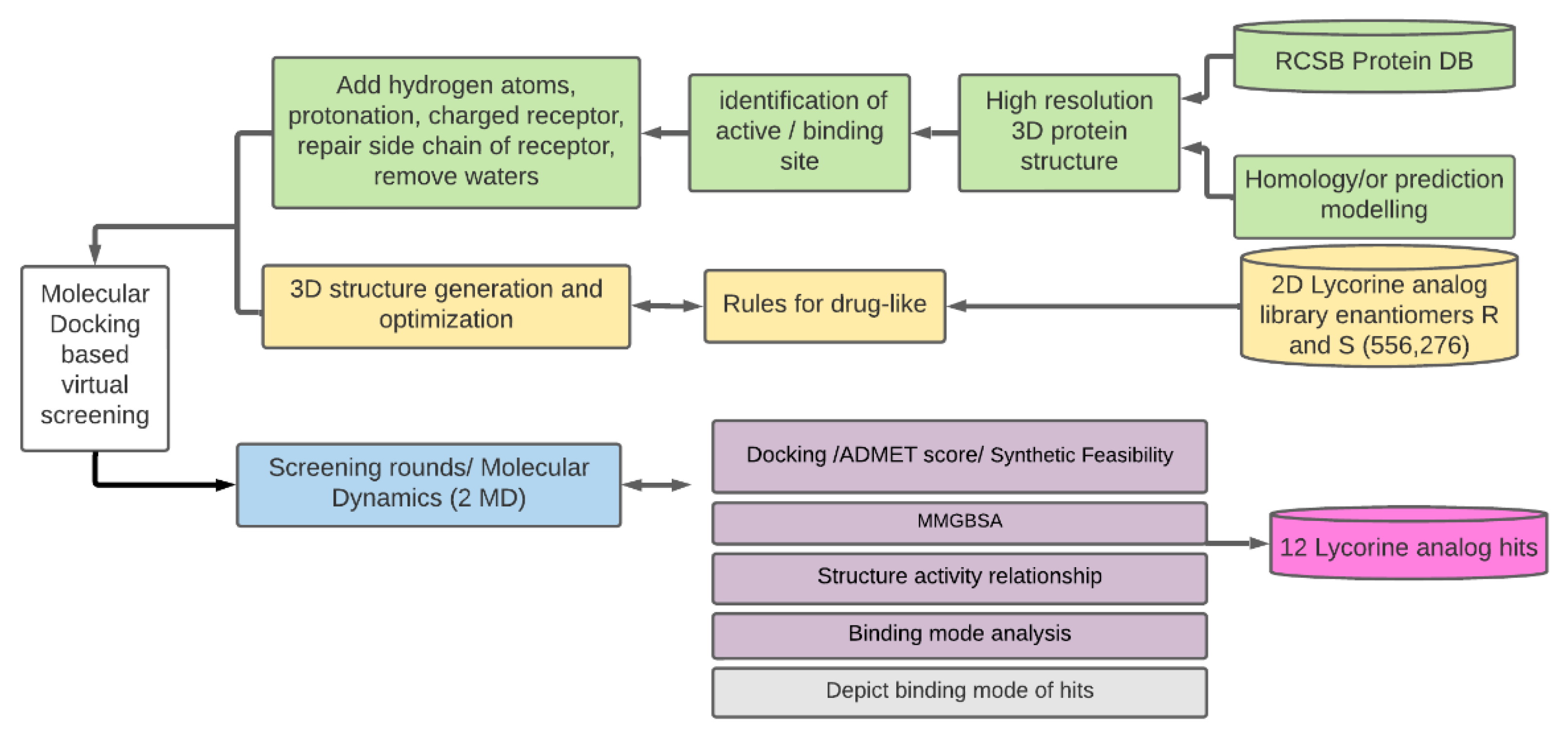

2. Materials and Methods

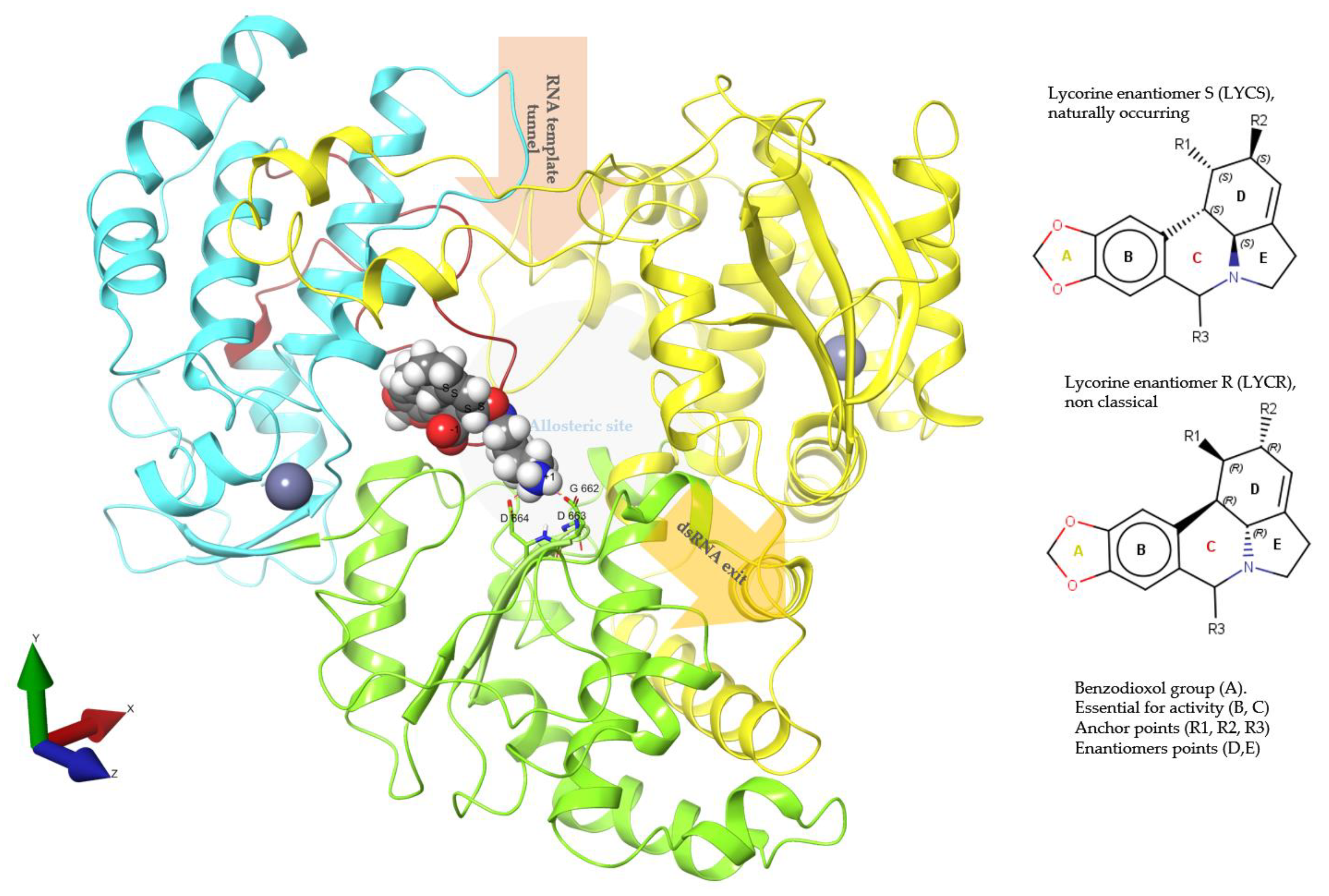

2.1. Preparation of DENV3 and ZIKV RdRp NS5 Structures

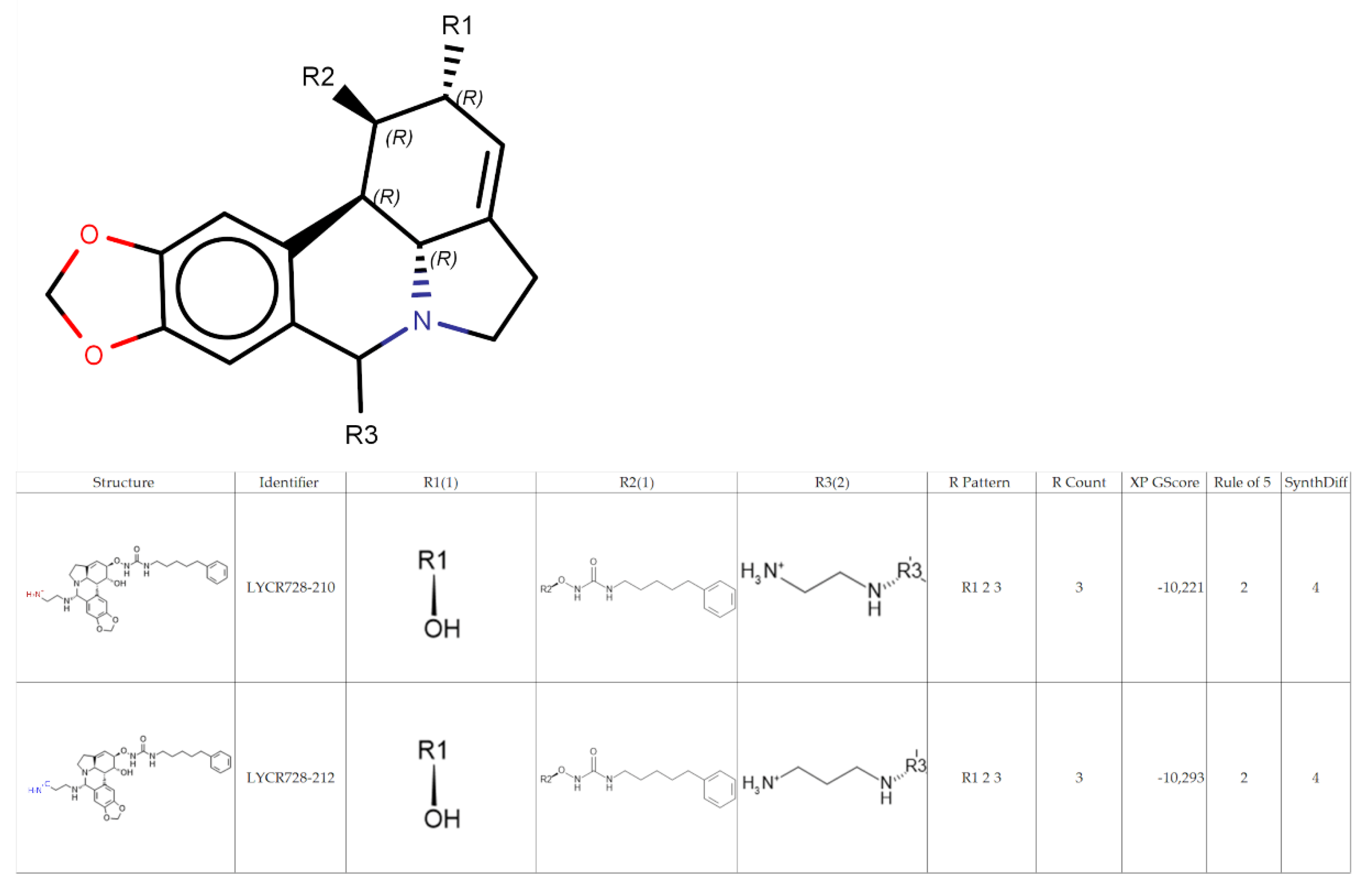

2.2. Generation of Lycorine Analogs Library

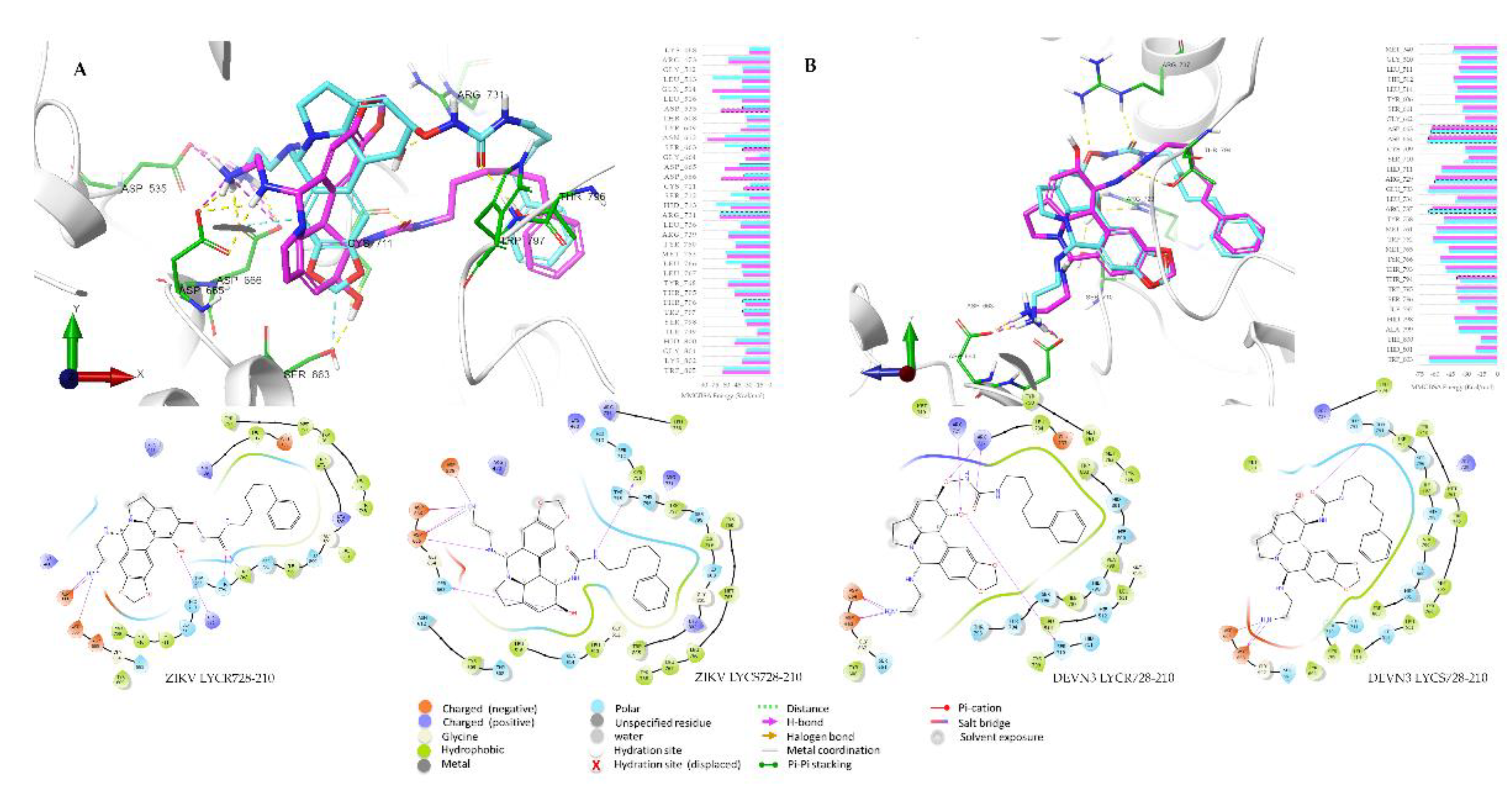

2.3. Molecular Docking Screening

2.4. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

2.5. MM/GBSA Free Energy Calculations

2.6. Chemoinformatic Analysis

2.7. Activity Cliff Detection and Matched Molecular Pair Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Authors Contributions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Messina, J.P.; Brady, O.J.; Golding, N.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; Wint, G.R.W.; Ray, S.E.; Pigott, D.M.; Shearer, F.M.; Johnson, K.; Earl, L.; et al. The Current and Future Global Distribution and Population at Risk of Dengue. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierson, T.C.; Diamond, M.S. The Continued Threat of Emerging Flaviviruses. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 796–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, P.R. Arboviruses: A Family on the Move. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1062, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, W.; Gong, P.; Gong, P. A Structural Overview of RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerases from the Flaviviridae Family. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 12943–12957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holbrook, M.R. Historical Perspectives on Flavivirus Research. Viruses 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-Hernández, M.Y.; Ruiz-Saenz, J.; Villamizar, L.J.; Gómez-Rangel, S.Y.; Martínez-Gutierrez, M. Co-Circulation and Simultaneous Co-Infection of Dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika Viruses in Patients with Febrile Syndrome at the Colombian-Venezuelan Border. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paixão, E.S.; Teixeira, M.G.; Rodrigues, L.C. Zika, Chikungunya and Dengue: The Causes and Threats of New and Reemerging Arboviral Diseases. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2018, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obi, J.O.; Gutiérrez-Barbosa, H.; Chua, J. V.; Deredge, D.J. Current Trends and Limitations in Dengue Antiviral Research. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, S.; Rashid, N.; Iftikhar, S. Dengue Proteins with Their Role in Pathogenesis, and Strategies for Developing an Effective Anti-Dengue Treatment: A Review. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 941–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEntire, C.R.S.; Song, K.W.; McInnis, R.P.; Rhee, J.Y.; Young, M.; Williams, E.; Wibecan, L.L.; Nolan, N.; Nagy, A.M.; Gluckstein, J.; et al. Neurologic Manifestations of the World Health Organization’s List of Pandemic and Epidemic Diseases. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppolu, V.; Shantha Raju, T. Zika Virus Outbreak: A Review of Neurological Complications, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options. J. Neurovirol. 2018, 24, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.J.R. da; Magalhães, J.J.F. de; Pena, L. Simultaneous Circulation of DENV, CHIKV, ZIKV and SARS-CoV-2 in Brazil: An Inconvenient Truth. One Heal. 2021, 12, 100205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, C.G.; Lim, S.P.; Arora, R.; Yokokawa, F.; Nilar, S.; Seh, C.C.; Wright, S.K.; Benson, T.E.; Smith, P.W.; Shi, P.Y. A Conserved Pocket in the Dengue Virus Polymerase Identified through Fragment-Based Screening. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 8541–8548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, R.; Liew, C.W.; Soh, T.S.; Otoo, D.A.; Seh, C.C.; Yue, K.; Nilar, S.; Wang, G.; Yokokawa, F.; Noble, C.G.; et al. Two RNA Tunnel Inhibitors Bind in Highly Conserved Sites in Dengue Virus NS5 Polymerase: Structural and Functional Studies. J. Virol. 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.J.; Liu, J.N.; Pan, X.D. Synthesis and Antiviral Activity of Lycorine Derivatives. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 22, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Lao, Z.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Long, H.; Li, D.; Lin, L.; Liu, X.; Yu, L.; Liu, W.; et al. Antiviral Activity of Lycorine against Zika Virus in Vivo and in Vitro. Virology 2020, 546, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.P.; Noble, C.G.; Seh, C.C.; Soh, T.S.; El Sahili, A.; Chan, G.K.Y.; Lescar, J.; Arora, R.; Benson, T.; Nilar, S.; et al. Potent Allosteric Dengue Virus NS5 Polymerase Inhibitors: Mechanism of Action and Resistance Profiling. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.; Rehman, A.U.; Badshah, S.L.; Ullah, A.; Mohammad, A.; Khan, K. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Zika Virus NS5 RNA Dependent RNA Polymerase with Selected Novel Non-Nucleoside Inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1203, 127428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi-Ayachi, A.; Santhanakrishnan, S.; Wong, Y.H.; Chan, K.W.K.; Tan, S.T.; Bates, R.W.; Vasudevan, S.G.; El Sahili, A.; Lescar, J. Non-Nucleoside Inhibitors of Zika Virus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase. J. Virol. 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, J.R.; Grinstein, S.; Orlowski, J. Sensors and Regulators of Intracellular PH. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Hu, Y.; Vogt, M.; Stumpfe, D.; Bajorath, J. MMP-Cliffs: Systematic Identification of Activity Cliffs on the Basis of Matched Molecular Pairs. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 52, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Cai, J.; Cheng, J.; Jing, C.; Yin, J.; Jiang, J.; Peng, Z.; Hao, X. Design, Synthesis and Structure-Activity Relationship Optimization of Lycorine Derivatives for HCV Inhibition. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, M.; Liang, L.; Xiao, X.; Feng, P.; Ye, M.; Liu, J. Lycorine: A Prospective Natural Lead for Anticancer Drug Discovery. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy, A.S.; Lima, G.M.A.; Oliveira, K.I.Z.; Torres, N.U.; Maluf, F. V; Guido, R.V.C.; Oliva, G. Crystal Structure of Zika Virus NS5 RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Sahili, A. RCSB PDB - 6LD5: Zika NS5 Polymerase Domain.

- Selisko, B.; Papageorgiou, N.; Ferron, F.; Canard, B. Structural and Functional Basis of the Fidelity of Nucleotide Selection by Flavivirus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerases. Viruses 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa da Silva, A.W.; Vranken, W.F. ACPYPE - AnteChamber PYthon Parser InterfacE. BMC Res. Notes 2012 51 2012, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci. Reports 2017 71 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead- and Drug-like Compounds: The Rule-of-Five Revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrchan, C.; Evertsson, E. Matched Molecular Pair Analysis in Short: Algorithms, Applications and Limitations. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, S.; Jasial, S.; Miyao, T.; Funatsu, K. Interpretation of Ligand-Based Activity Cliff Prediction Models Using the Matched Molecular Pair Kernel. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, D.; Hahn, M. Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. ILOGP: A Simple, Robust, and Efficient Description of n-Octanol/Water Partition Coefficient for Drug Design Using the GB/SA Approach. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 3284–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Lin, F.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Lai, L. Computation of Octanol−Water Partition Coefficients by Guiding an Additive Model with Knowledge. J Chem Inf Model 2007, 47, 2140–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baell, J.B.; Holloway, G.A. New Substructure Filters for Removal of Pan Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) from Screening Libraries and for Their Exclusion in Bioassays. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 2719–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, T.; Hoffmann, R.D. Methods and Principles in Medicinal Chemistry. Pharmacophores and Pharmacophore Searches.; 2006; ISBN 3527609164r9783527609161r9783527608720r3527608729.

- Tarantino, D.; Cannalire, R.; Mastrangelo, E.; Croci, R.; Querat, G.; Barreca, M.L.; Bolognesi, M.; Manfroni, G.; Cecchetti, V.; Milani, M. Targeting Flavivirus RNA Dependent RNA Polymerase through a Pyridobenzothiazole Inhibitor. Antiviral Res. 2016, 134, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netzler, N.E.; Enosi Tuipulotu, D.; Eltahla, A.A.; Lun, J.H.; Ferla, S.; Brancale, A.; Urakova, N.; Frese, M.; Strive, T.; Mackenzie, J.M.; et al. Broad-Spectrum Non-Nucleoside Inhibitors for Caliciviruses. Antiviral Res. 2017, 146, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z. Multi-Objective de Novo Drug Design with Conditional Graph Generative Model. J. Cheminform. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertl, P.; Schuffenhauer, A. Estimation of Synthetic Accessibility Score of Drug-like Molecules Based on Molecular Complexity and Fragment Contributions. J. Cheminform. 2009, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrodinger Structure-Based Virtual Screening Using Glide. 2020.

- Yi, D.; Li, Q.; Pang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, Z.; Liang, C.; Cen, S. Identification of a Broad-Spectrum Viral Inhibitor Targeting a Novel Allosteric Site in the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerases of Dengue Virus and Norovirus. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Molecule | Lipinski | Ghose | Veber | Egan | Muegge | Synthetic Accessibility |

| Rivabirin | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3,89 |

| Lycorine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4,2 |

| LYCS214-507 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4,94 |

| LYCS505-214 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5,04 |

| LYCR66-506 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5,09 |

| LYCS510-212 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5,18 |

| LYCR211-507 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5,27 |

| LYCS510-214 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5,31 |

| LYCS214-510 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5,76 |

| LYCS728-210 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5,87 |

| LYCR728-210 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6,11 |

| LYCR728-212 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6,24 |

| LYCR294-114 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6,41 |

| LYCR727-112 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6,57 |

| Molecule | GI absorption | BBB permeant | Bioavailability Score | CYP-Substrate/inhibitor | ||||

| CYP1A2 | CYP2C19 | CYP2C9 | CYP2D6 | CYP3A4 | ||||

| Rivabirin | Low | No | 0,55 | No | No | No | No | No |

| Lycorine | High | No | 0,55 | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| LYCS214-507 | High | No | 0,55 | No | No | No | No | No |

| LYCS505-214 | High | No | 0,55 | No | No | No | No | No |

| LYCR66-506 | High | No | 0,55 | No | No | No | No | No |

| LYCS510-212 | High | No | 0,55 | No | No | No | No | No |

| LYCR211-507 | High | No | 0,55 | No | No | No | No | No |

| LYCS510-214 | High | No | 0,55 | No | No | No | No | No |

| LYCS214-510 | High | No | 0,55 | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| LYCS728-210 | High | No | 0,55 | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| LYCR728-210 | High | No | 0,55 | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| LYCR728-212 | High | No | 0,55 | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| LYCR294-114 | High | No | 0,55 | No | No | No | No | No |

| LYCR727-112 | High | No | 0,55 | No | No | No | No | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).