Submitted:

04 July 2024

Posted:

04 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

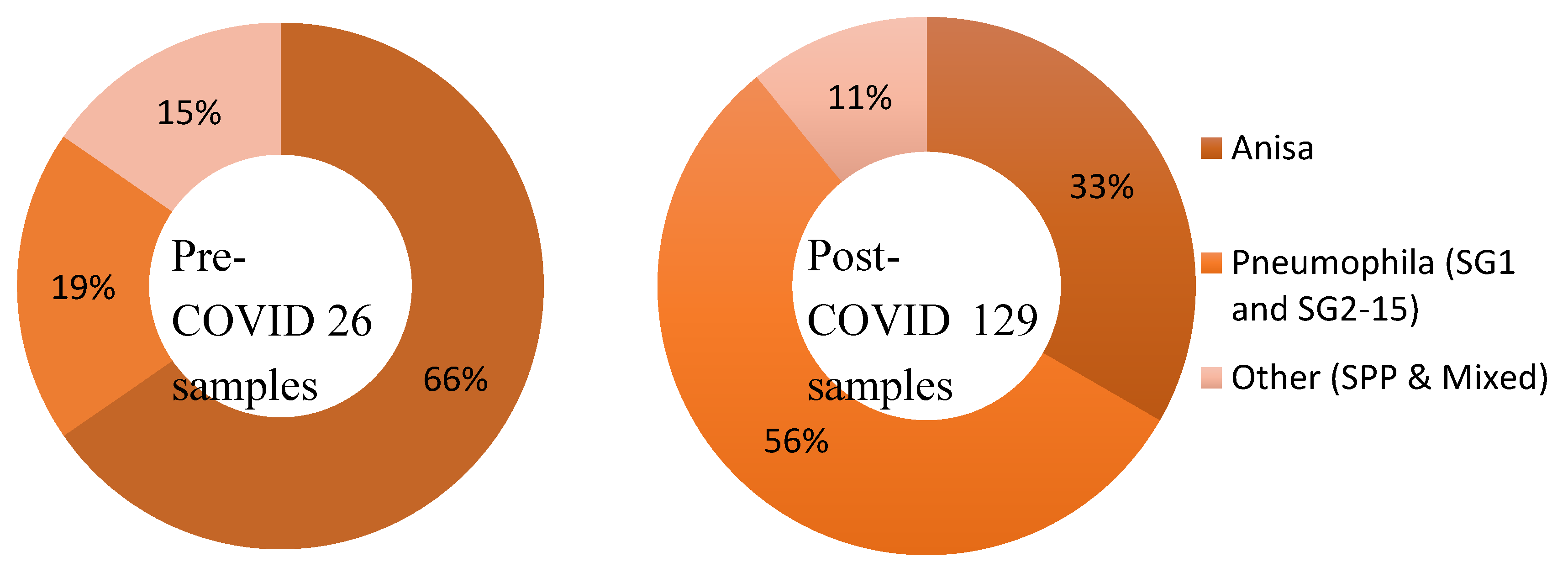

Overview

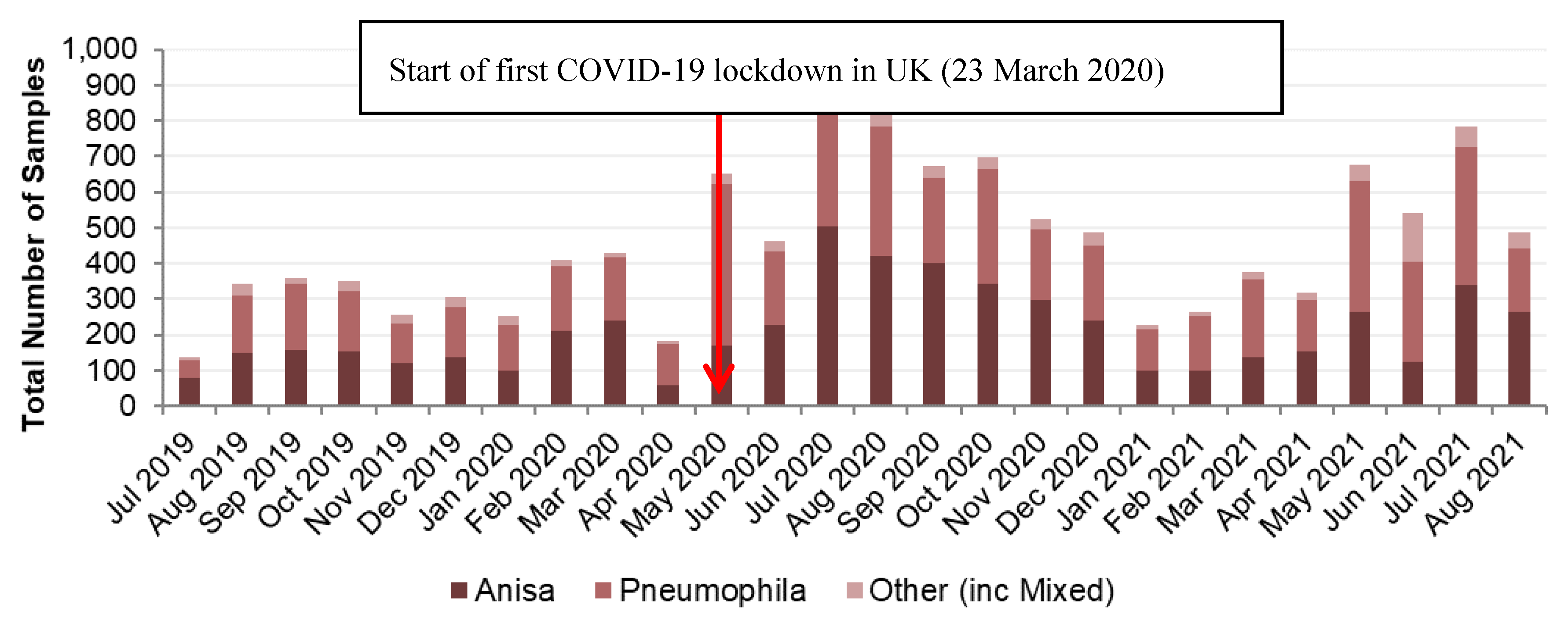

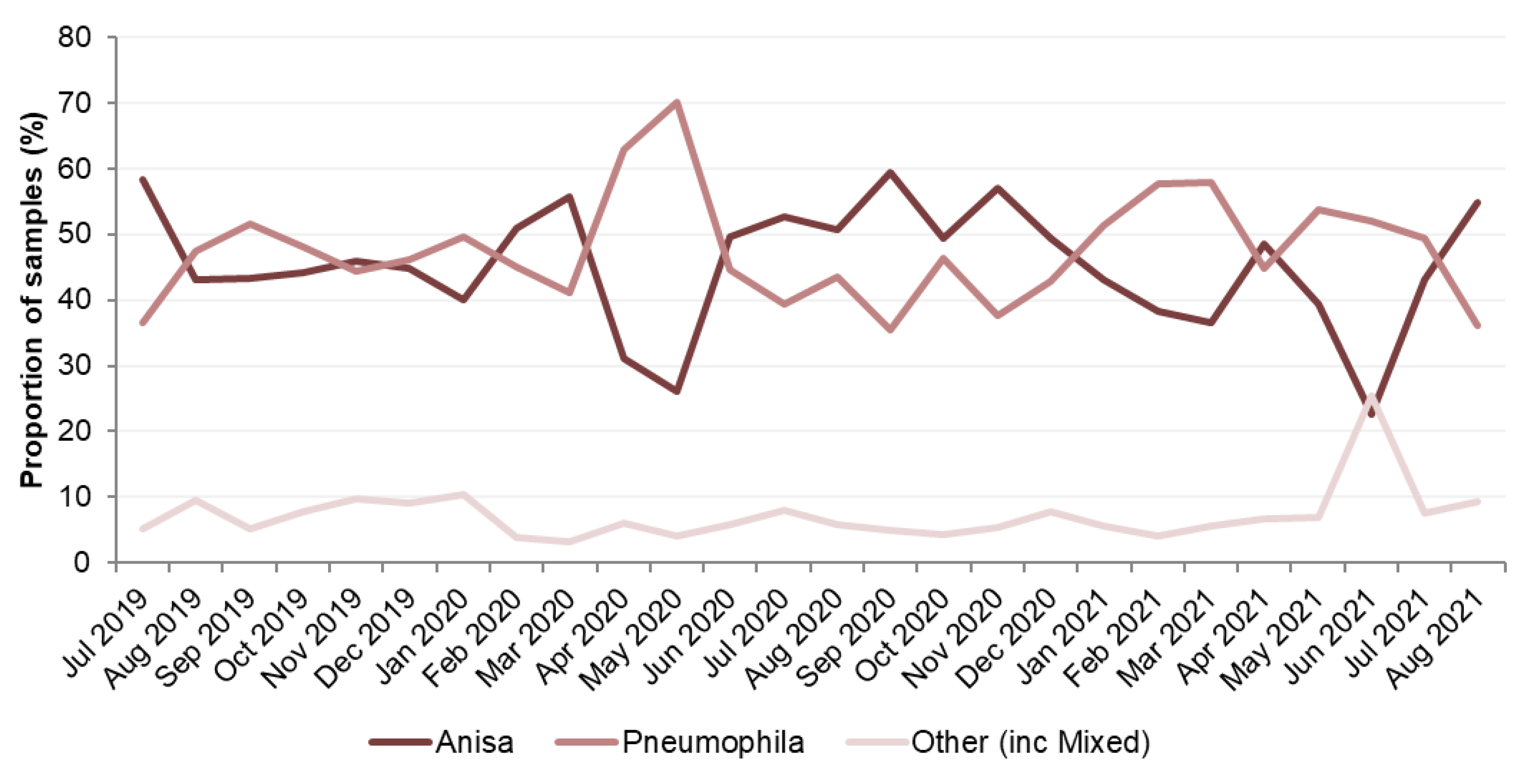

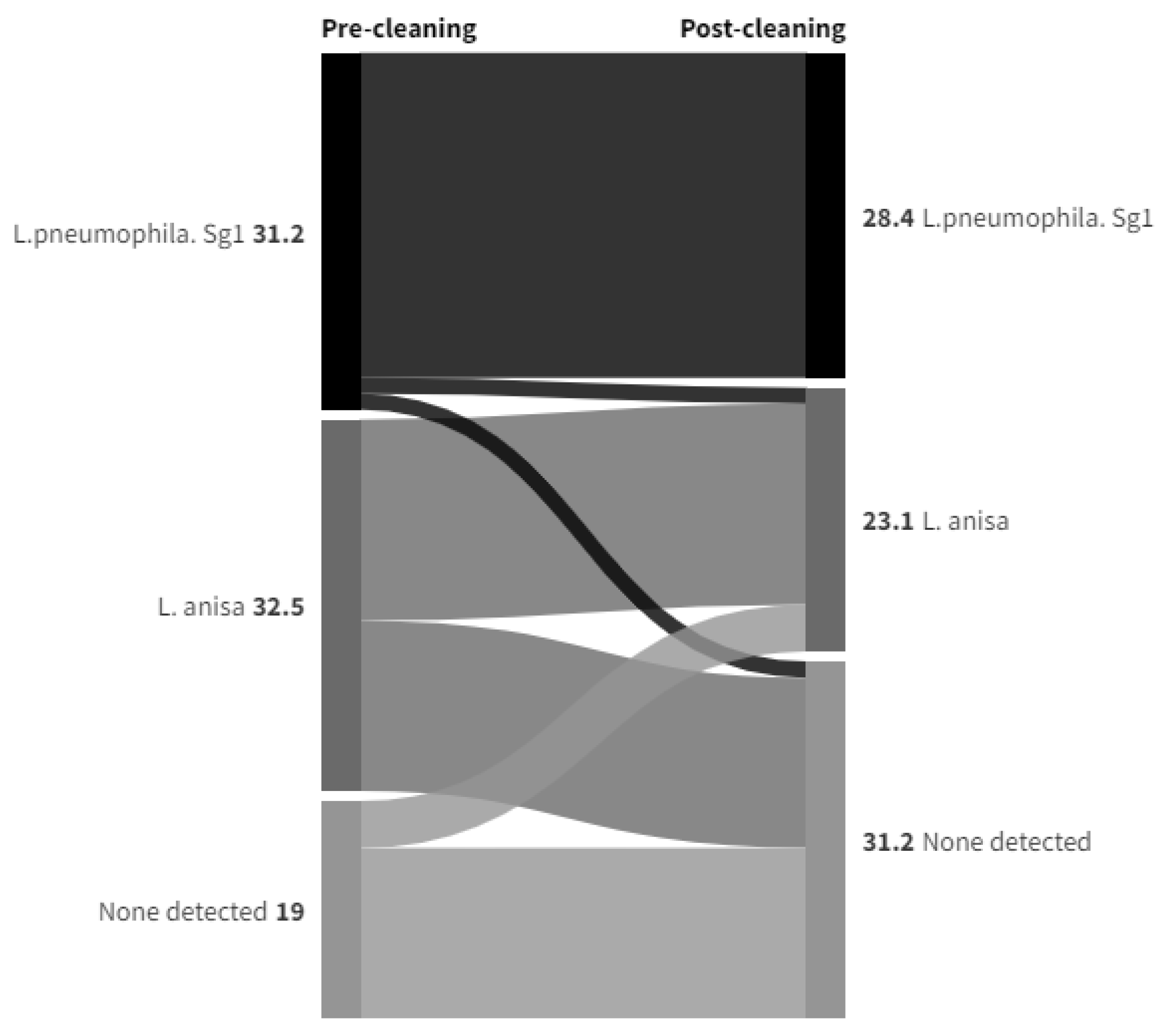

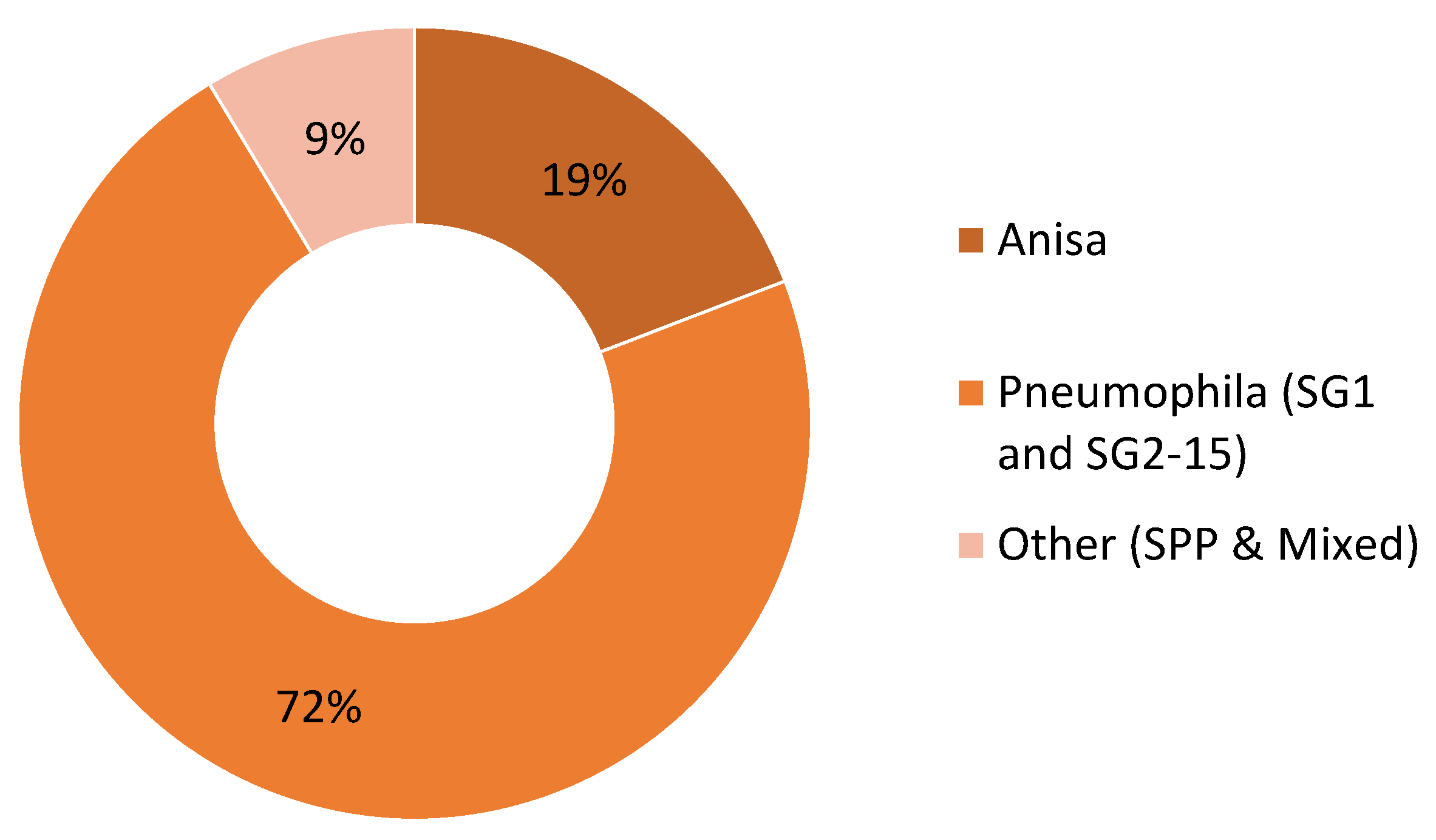

Legionella Data set 1

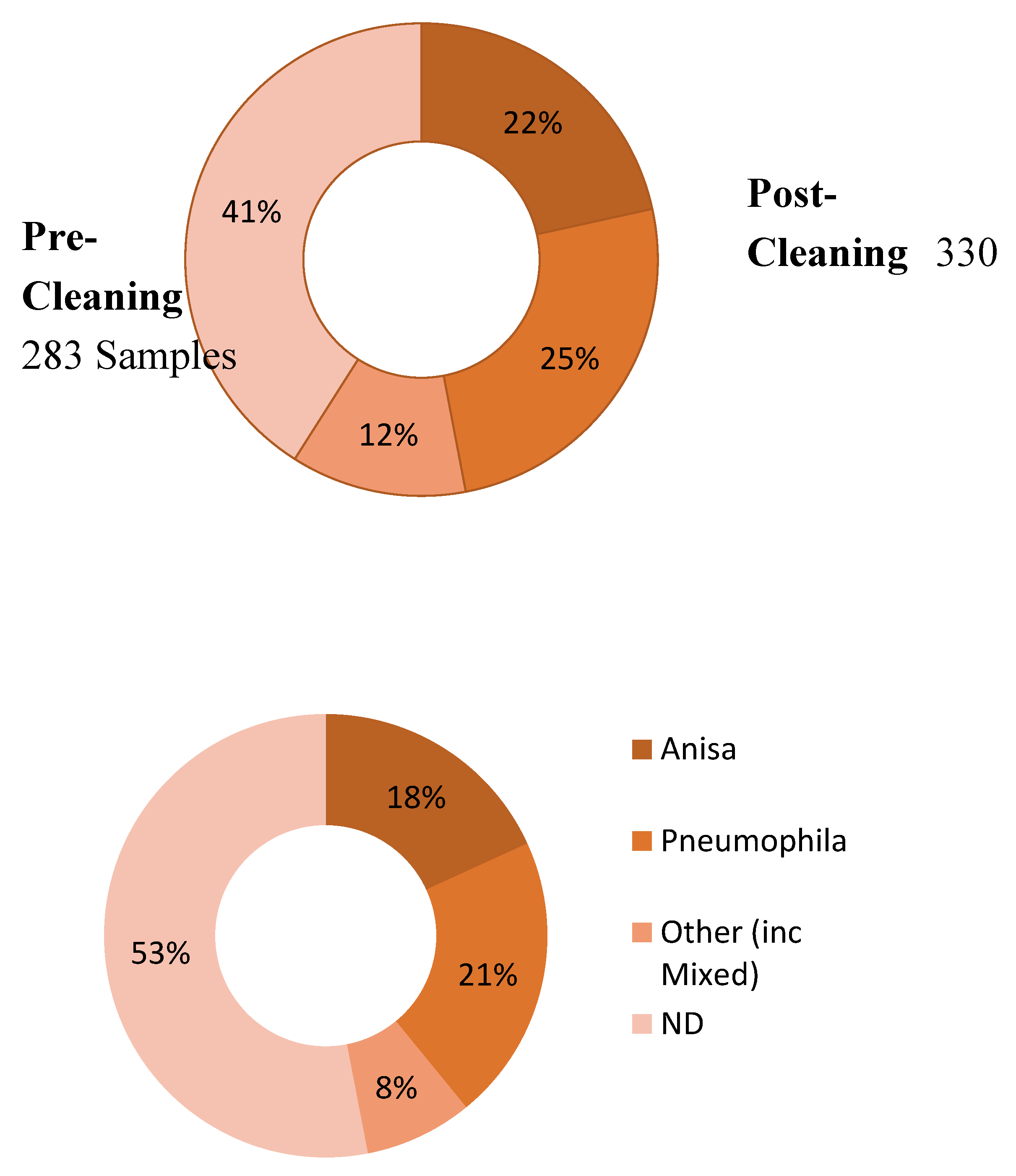

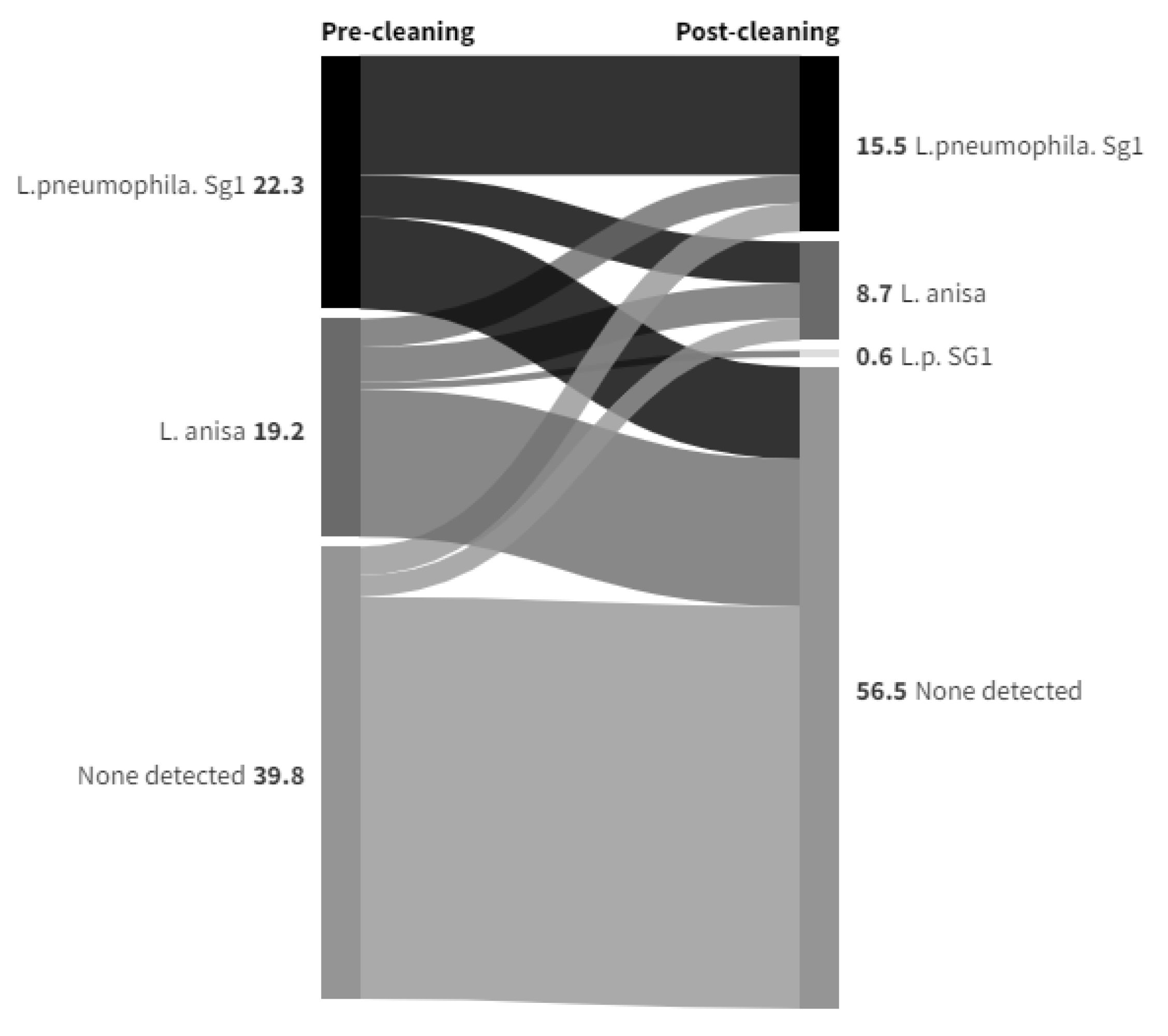

Legionella Data set 2

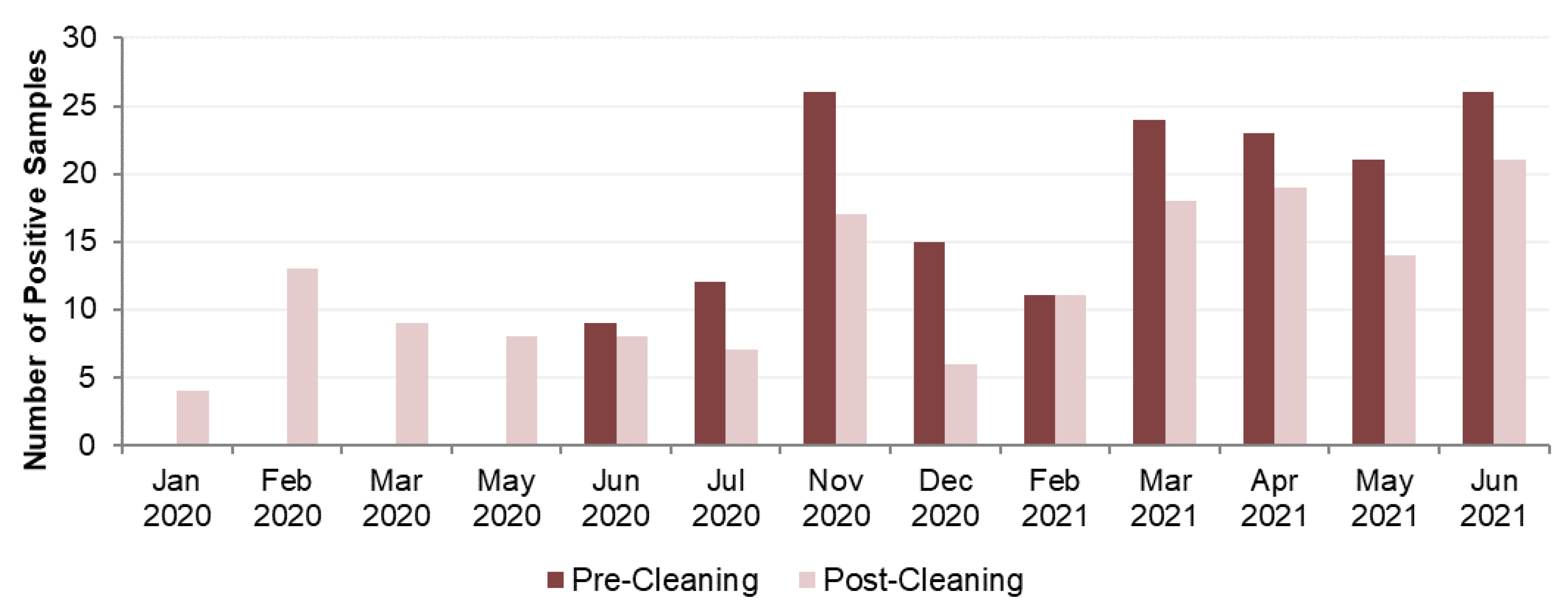

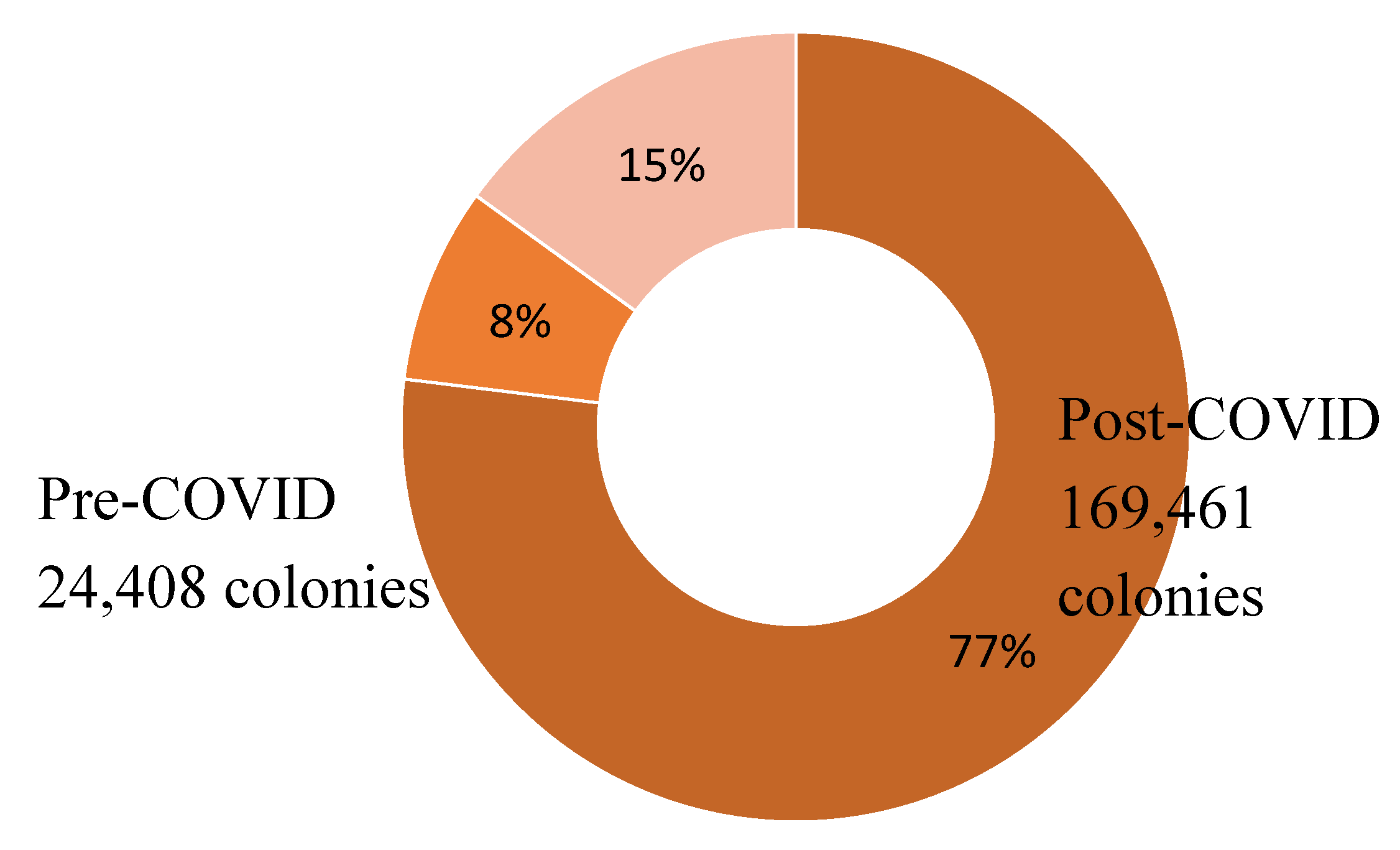

Legionella Data set 3

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walker, J.T.; McDermott, P.J. Confirming the presence of Legionella pneumophila in your water system: a review of current Legionella Testing Methods. Journal of AOAC International 2021, 104, 1135–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muder, R.R.; Yu, V.L. Infection Due to Legionella Species Other Than L. pneumophila. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2002, 35, 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozak-Muiznieks, N.A.; Lucas, C.E.; Brown, E.; Pondo, T.; Taylor Jr, T.H.; Frace, M.; Miskowski, D.; Winchell, J.M. Prevalence of sequence types among clinical and environmental isolates of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 in the United States from 1982 to 2012. Journal of clinical microbiology 2014, 52, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ECDC. Legionnaires' disease Annual Epidemiological Report for 2021. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/legionnaires-disease-annual-epidemiological-report-2021 (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Cross, K.E.; Mercante, J.W.; Benitez, A.J.; Brown, E.W.; Diaz, M.H.; Winchell, J.M. Simultaneous detection of Legionella species and L. anisa, L. bozemanii, L. longbeachae and L. micdadei using conserved primers and multiple probes in a multiplex real-time PCR. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016, 85, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccaro, L.; Izquierdo, F.; Magnet, A.; Hurtado, C.; Salinas, M.A.; Gomes, T.S. First Case of Legionnaire's Disease Caused by Legionella anisa in Spain and the Limitations on the Diagnosis of Legionella non-pneumophila Infections. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, S.T.; Slow, S.; Scott-Thomas, A.; Murdoch, D.R. Legionellosis Caused by Non-Legionella pneumophila Species, with a Focus on Legionella longbeachae. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, R.J.; Stack, B.H.R. Legionnaires' disease due to Legionella anisa. Journal of Infection 1990, 20, 227–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, M.C.; Sebti, R.; Hassoun, P.; Mannion, C.; Goy, A.H.; Feldman, T.; Mato, A.; Hong, T. Osteomyelitis of the Patella Caused by Legionella anisa. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2013, 51, 2791–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thacker, L.; Benson, R.F.; Hawes, L.; Mayberry, W.R.; Brenner, D.J. Characterization of a Legionella anisa strain isolated from a patient with pneumonia. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 1990, 28, 122–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan-Jackson, A.R.; Flood, M.; Rose, J.B. Enumeration and characterization of five pathogenic Legionella species from large research and educational buildings. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol. 2021, 7, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzotta, M.; Salaris, S.; Pascale, M.R.; Girolamini, L.; Cristino, S. Occurrence of Legionella spp. In Man-MadeWater Sources: Isolates Distribution and Phylogenetic Characterization in the Emilia-Romagna Region. Pathogens 2021, 10, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascale, M.R.; Mazzotta, M.; Salaris, S.; Girolamini, L.; Grottola, A.; Simone, M.L.; Cordovana, M.; Bisognin, F.; Dal Monte, P.; Bucci Sabattini, M.A.; et al. Evaluation of MALDI–TOF Mass Spectrometry in Diagnostic and Environmental Surveillance of Legionella Species: A Comparison with Culture and Mip-Gene Sequencing Technique. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 589369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crook, B.; Willerton, L.; Smith, D.; Wilson, L.; Poran, V.; Helps, J.; McDermott, P. Legionella risk in evaporative cooling systems and underlying causes of associated breaches in health and safety compliance. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 2020, 224, 113425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, V.L.; Plouffe, J.F.; Castellani Pastoris, M.; Stout, J.E.; Schousboe, M.; Widmer, A.; Summersgill, J.; File, T.; Heath, C.M.; Paterson, D.L.; et al. Distribution of Legionella Species and Serogroups Isolated by Culture in Patients with Sporadic Community-Acquired Legionellosis: An International Collaborative Survey. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2002, 186, 127–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, et al S. Collins1,2, F. Jorgensen2, C. Willis2 and J. Walker Real-time PCR to supplement gold-standard culture-based detection of Legionella in environmental samples. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2015, 119, 1158–1169. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.C.; Vickers, R.M.; Yu, V.L.; Wagener, M.M. Growth of 28 Legionella species on selective culture media: a comparative study. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 1993, 31, 2764–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, V.L.; Stout, J.E. Legionella anisa and hospital water systems. J Infect Chemother 2004, 10, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compain, F.; Bruneval1, P.; Jarraud, S.; Perrot, S.; Aubert, S.; Napoly, V.; Ramahefasolo, A.; Mainardi, J.-L.; Podglajen, I. Chronic endocarditis due to Legionella anisa: a first case difficult to diagnose. New Microbe and New Infect 2015, 8, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, N.; Mercatello, A.; Marmet, D.; Surgot, M.; Deveaux, Y.; Fleurette, J. Pleural infection caused by Legionella anisa. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 1989, 27, 2100–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, M.; Nakajima, H.; Nakamura, A.; Ito, T.; Nakamura, M.; Shimono, T.; Wada, H.; Shimpo, H.; Nobori, T.; Ito, M. Mycotic Aortic Aneurysm Associated with Legionella anisa. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2009, 47, 2340–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, G.W.; Feeley, J.C.; Steigerwalt, A.; Edelstein, P.H.; Moss, W.; Brenner, D.J. Legionella anisa: a new species of Legionella isolated from potable waters and a cooling tower. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1985, 49, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan-Jackson, A.; Rose, J.B. Co-occurrence of Five Pathogenic Legionella spp. and Two Free-Living Amoebae Species in a Complete Drinking Water System and Cooling Towers. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenstersheib, M.D.; Miller, M.; Diggins, C.; Liska, S.; Detwiler, L.; Werner, S.B.; Lindquist, D.; Thacker, W.L.; Benson, R.F. Outbreak of Pontiac fever due to Legionella anisa. Lancet 1990, 336, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, T.F.; Benson, R.F.; Brown, E.W.; Rowland, J.R.; Crosier, S.C.; Schaffner, W. Epidemiologic Investigation of a Restaurant- Associated Outbreak of Pontiac Fever. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2003, 37, 1292–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doleans, A.; Aurell, H.; Reyrolle, M.; Lina, G.; Freney, J.; Vandenesch, F.; Etienne, J.; Jarraud, S. Clinical and Environmental Distributions of Legionella Strains in France Are Different. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2004, 42, 458–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svarrer, C.W.; Uldum, S.A. The occurrence of Legionella species other than Legionella pneumophila in clinical and environmental samples in Denmark identified by mip gene sequencing and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012, 18, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, B.S.; Barbaree, J.M.; Sanden, G.N.; Morrill, W.E. Virulence of a Legionella anisa Strain Associated with Pontiac Fever: an Evaluation Using Protozoan, Cell Culture, and Guinea Pig Models. Infection and Immunity 1990, 58, 3139–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Scola, B.; Mezi, L.; Weiller, P.J.; Raoult, D. Isolation of Legionella anisa Using an Amoebic Coculture Procedure. 39Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2001, 39, 365–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnier, I.; Croce, O.; Robert, C.; Raoult, D.; La Scola, B. Genome sequence of Legionella anisa, isolated from a respiratory sample, using an amoebal coculture procedure. Genome Announc. 2014, 2, e00031-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peci, A.; Winter, A.-L.; Gubbay, J.B. Evaluation and Comparison of Multiple Test Methods, Including Real-time PCR, for Legionella Detection in Clinical Specimens. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, T.; Nakagawa, N.; Murata, M.; Yasuo, S.; Yoshida, T.; Ando, K.; Okamori, S.; Okada, Y. Diagnostic accuracy of urinary antigen tests for legionellosis; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respiratory Investigation 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, B.S.; Benson, R.F.; Besser, R.E. Legionella and Legionnaires’ Disease: 25 Years of Investigation. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2002, 15, 506–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uldum, S.A.; Schjoldager, L.G.; Baig, S.; Cassell, K. A Tale of Four Danish Cities: Legionella pneumophila Diversity in Domestic Hot Water and Spatial Variations in Disease Incidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, B.M.; Trajtman, A.; Bernard, K.; Burdz, T.; Vélez, L.; Herrera, M.; Rueda, Z.V.; Keynan, Y. Legionella co-infection in HIV-associated pneumonia. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 2019, 95, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, P.; Drancourt, M.; Gouriet, F.; La Scola, B.; Fournier, P.-E.; Rolain, J.M.; Raoult, D. Ongoing Revolution in Bacteriology: Routine Identification of Bacteria by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2009, 49, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Scola, B.; Raoult, D. Direct Identification of Bacteria in Positive Blood Culture Bottles by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionisation Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e8041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiaa, V.; Casatia, S.; Tonolla, M. Rapid identification of Legionella spp. By MALDI-TOF MS based protein mass fingerprinting. Systematic and Applied Microbiology 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boczek, L.A.; Tang, M.; Formal, C.; Lytle, D.; Ryu, H. Comparison of two culture methods for the enumeration of Legionella pneumophila from potable water samples. Journal of Water and Health 2021, 19, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health and Safety Executive. Legionnaires’ disease Technical guidance HSG274 Part 2: The control of Legionella bacteria in hot and cold water systems. Available online: https://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/books/hsg274.htm (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- van der Mee-Marquet, N.; Domelier, A.-S.; Arnault, L.; Bloc, D.; Laudat, P.; Hartemann, P.; Quentin, R. Legionella anisa, a Possible Indicator of Water Contamination by Legionella pneumophila. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2006, 44, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, I.J.; Sangster, N.; Ratcliff, R.M.; Mugg, P.A.; Davos, D.E.; Lanser, J.E. Problems Associated with Identification of Legionella Species from the Environment and Isolation of Six Possible New Species. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1990, 56, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edagawa1, A.; Kimura, A.; Doi, H.; Tanaka, H.; Tomioka, K.; Sakabe, K.; Nakajima, C.; Suzuki, Y. Detection of culturable and nonculturable Legionella species from hot water systems of public buildings in Japan. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2008, 105, 2104–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.K.; Shim, J.I.; Kim, H.E.; Yu, J.Y.; Kang, Y.H. Distribution of Legionella Species from Environmental Water Sources of Public Facilities and Genetic Diversity of L. pneumophila Serogroup 1 in South Korea. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2010, 76, 6547–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleres, G.; Couto, N.; Lokate, M.; van der Sluis, L.W.M.; Ginevra, C.; Jarraud, S.; Deurenberg, R.H.; Rossen, J.W.; García-Cobos, S.; Friedrich, A.W. Detection of Legionella anisa in Water from Hospital Dental Chair Units and Molecular Characterization by Whole-Genome Sequencing. Microorganisms 2018, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolamini, L.; Salaris, S.; Pascale, M.R.; Mazzotta, M.; Cristino, S. Dynamics of Legionella Community Interactions in Response to Temperature and Disinfection Treatment: 7 Years of Investigation. Microbial Ecology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, M.B.; Fenoy, S.; Magnet, A.; Vaccaro, L.; Gomes, T.D.S.; Angulo, S.; Hurtado, C.; Ollero, D.; Valdivieso, E.; del Águila, D.; et al. Are pathogenic Legionella non- pneumophila a common bacteria in Water Distribution Networks? Water Res 2021, 196, 117013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, A.S.S.; Caiaffa Filho, H.H.; Sinto, S.I.; Sabbaga, E.; Barone, A.A.; Mendes, C.M.F. An outbreak of nosocomial Legionnaires’ disease in a renal transplant unit in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Journal of Hospital Infection 1991, 18, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, M.; Owan, T.; Nakasone, C.; Yamamoto, N.; Haranaga, S.; Higa, F.; Tateyama, M.; Yamane, N.; Fujita, J. Prospective Monitoring Study: Isolating Legionella pneumophila in a Hospital Water System Located in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Ward after Eradication of Legionella anisa and Reconstruction of Shower Units. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 60, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolamini, L.; Salaris, S.; Lizzadro, J.; Mazzotta, M.; Pascale, M.R.; Pellati, T.; Cristino, S. How Molecular Typing Can Support Legionella Environmental Surveillance in Hot Water Distribution Systems: A Hospital Experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stout, J.E.; Muder, R.R.; Mietzner, S.; Wagener, M.M.; Perri, M.B.; DeRoos, K.; Goodrich, D.; Arnold, W.; Williamson, T.; Ruark, O.; et al. Role of Environmental Surveillance in Determining the Risk of Hospital-Acquired Legionellosis: A National Surveillance Study with Clinical Correlations. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007, 28, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syndnor, E.R.M.; Bova, G.; Gimburg, A.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Perl, T.M.; Maragakis, L.L. Electronic-eye faucets; Legionella species contamination in healthcare settings. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2012, 33, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Kubota, T.; Tateyama, M.; Koide, M.; Nakasone, C.; Tohyama, M.; Shinzato, T.; Higa, F.; Kusano, N.; Kawakami, K.; et al. Isolation of Legionella anisa from multiple sites of a hospital water system: the eradication of Legionella contamination. J Infect Chemother 2003, 2003 9, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krøjgaard, L.H.; Krogfelt, K.A.; Albrechtsen, H.J.; Uldum, S.A. Cluster of Legionnaires’ disease in a newly built block of flats, Denmark, December 2008 – January 2009. Euro Surveill. 2011, 16, 19759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhat, M.; Moletta-Denat, M.; Frère, J.; Onillon, S.; Trouilhé, M.-C.; Robinea, E. Effects of Disinfection on Legionella spp., Eukarya, and Biofilms in a Hot Water System. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2012, 78, 6850–6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.E.; Stout, J.E.; Yu, V.L. Controlling Legionella in Hospital Drinking Water: An Evidence-Based Review of Disinfection Methods. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2011, 32, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, M.A.; Ross, K.E.; Brown, M.H.; Bentham, R.; Whiley, H. Water Stagnation and Flow Obstruction Reduces the Quality of Potable Water and Increases the Risk of Legionelloses. Front. Environ. Sci. 2020, 8, 611611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legionella Control Association webinar – Legionella dangers emerging from lockdown. Available online: https://www.legionellacontrol.org.uk/video-media/view/?id=17 (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- British Standard BS7592:2022; Sampling for Legionella bacteria in water systems — Code of practice.

- British Standard BS EN ISO 11731:2017. Water quality — Enumeration of Legionella.

| Post-Cleaning Sample | Grand Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anisa | Pneumophila | Other | ND | |||

| Pre-Cleaning Sample | Anisa | 18 | 6 | 3 | 34 | 61 |

| Pneumophila | 8 | 54 | 4 | 15 | 81 | |

| Other | 6 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 25 | |

| ND | 6 | 5 | 1 | 103 | 115 | |

| Grand Total | 38 | 71 | 12 | 161 | 282 | |

| Date | Pre-Cleaning Sample Colonies | Post-Cleaning Sample Colonies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anisa | Pneumophila | Other | Total | Anisa | Pneumophila | Other | Total | |

| Jan 2020 | 40 | 1,520 | 0 | 1,560 | ||||

| Feb 2020 | 12,920 | 80 | 1,268 | 14,268 | ||||

| Mar 2020 | 5,820 | 360 | 2,400 | 8,580 | ||||

| May 2020 | 2,920 | 2,120 | 1,460 | 6,500 | ||||

| Jun 2020 | 4,762 | 7,630 | 0 | 12,392 | 3,081 | 1,540 | 0 | 4,621 |

| Jul 2020 | 3,180 | 460 | 6,400 | 10,040 | 3,340 | 0 | 180 | 3,520 |

| Nov 2020 | 11,080 | 25,080 | 4,200 | 40,360 | 1,260 | 10,820 | 1,400 | 13,480 |

| Dec 2020 | 2,520 | 8,280 | 0 | 10,800 | 120 | 3,180 | 0 | 3,300 |

| Feb 2021 | 2,821 | 26,496 | 0 | 29,317 | 408 | 19,635 | 4,400 | 24,443 |

| Mar 2021 | 11,673 | 50,127 | 2,120 | 63,920 | 8,937 | 37,380 | 0 | 46,317 |

| Apr 2021 | 28,875 | 39,480 | 17,260 | 85,615 | 940 | 11,540 | 3,860 | 16,340 |

| May 2021 | 3,400 | 111,440 | 0 | 114,840 | 0 | 20,880 | 200 | 21,080 |

| Jun 2021 | 6,680 | 53,540 | 9,700 | 69,920 | 11,460 | 15,240 | 3,160 | 29,860 |

| Total | 74,991 | 322,533 | 39,680 | 437,204 | 51,246 | 124,295 | 18,328 | 193,869 |

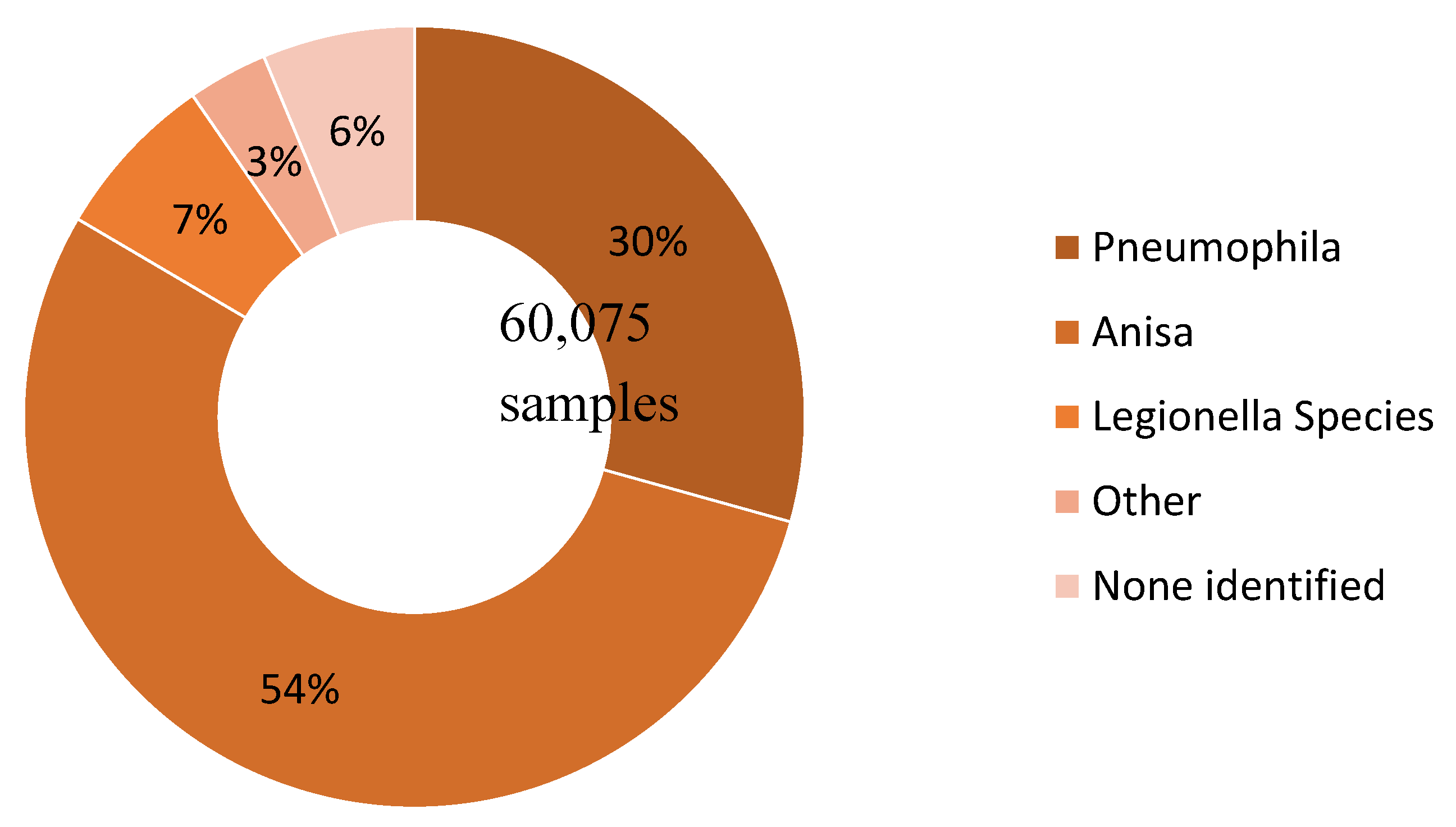

| Species Detected | Count | (Proportion) |

|---|---|---|

| Legionella pneumophila | 17,617 | (29.3%) |

| Legionella anisa | 32,517 | (54.1%) |

| Legionella species | 4,162 | (6.9%) |

| Other | 1,992 | (3.3%) |

| Blank (no species identified) | 3,787 | (6.3%) |

| TOTAL | 60,075 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).