1. Introduction

Normal alleles of the

SERPINA1 gene are referred to as PiM, where "Pi" stands for protease inhibitor and "M" denotes medium mobility. The PiM allele produces the standard form and normal levels (1.2-2 g/L) of alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) protein, which functions to protect tissues from enzymes released during inflammation, particularly in the lungs [

1] Most common mutant alleles of the

SERPINA1 gene are Pi*Z (Glu342Lys) and Pi*S (Glu264Val) Individuals with two mutated alleles (homozygous or compound heterozygous individuals) have significantly reduced levels of functional AAT and are at a much higher risk for early onset lung diseases and occasionally to vasculitis, necrotizing panniculitis, or other chronic inflammatory diseases [

2]. Nearly 100 percent of the clinical cases of AATD-associated pathologies involve the

Pi*Z allele, as

PiZZ homozygous or less frequently as compound heterozygous [

3]. In clinical practice, pulmonary emphysema, bronchiectasis and chronic bronchitis are the most frequently associated with PiZZ [

4] while the significance of heterozygous variants such as PiSZ, PiMZ, PiMS is less clear [

5,

6,

7].

Other less common mutant alleles include Pi*F (fast migration) and Pi*I (intermediate migration), which produces AAT with slightly altered function and usually does not cause significant clinical symptoms. Null alleles (e.g., Pi*Q0) result in not measurable or very low levels of AAT and high risk for pulmonary diseases [

8]. To date, hundreds of variants of the

SERPINA1 gene have been identified and about 70 of them have been associated with clinical manifestations [

1].

In this study we aimed to determine the prevalence of Pi*Z and Pi*S AATD variants in a cohort of Lithuanian small children diagnosed as wheezers of varying severity, and compare findings with control group as well as with data earlier collected from COPD patients in the Central-Eastern European AAT Network and non-disease specific epidemiological studies (SES) performed in our region [

9,

10].

2. Materials and Methods

In total 145 children with an acute wheezing episode were included in the study. In addition, 74 children without respiratory conditions who were hospitalized for various surgical pathology and required a blood sample in preparation for surgery were used as a control group (

Table 1). The study was carried out with the permission of the Lithuanian Bioethics Committee (L-16-07/2).

Blood samples were taken on a dry blood spot cards and sent to the National Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases in Warsaw, Poland. Diagnostic tests performed included determination of AAT concentration, phenotyping, genotyping, and DNA sequencing when appropriate.

Wheezing severity, which was classified into mild, medium and severe, was calculated using the Pediatric Respiratory Assessment Measure (PRAM). We looked for an association between AAT genotypes and the severity of wheezing.

Data for comparison with COPD patients were taken from the CEE A1AT Network, established within the LPP Leonardo da Vinci EU program (2011-1-PL-LEO04-197151) “Introducing standards of the best medical practice for the patients with inherited Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency in Central Eastern Europe” DBS samples were collected from 328 COPD patients between October 2012-January 2013. The data were also compared with two previous epidemiological studies conducted with healthy Lithuanian subjects (n=2491) in determining the general population frequency of PI*S and PI*Z genes [

11,

12].

3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0 and Microsoft Excel. Continuous and categorical variables were presented as median (interquartile range (IQR) and numbers (percentages %), respectively. Mann-Whitney U or Friedman test was used to compare continuous variables, and χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Pi*Z and Pi*S frequency is expressed as a frequency per thousand alleles with 95% CI (e.g. 3 Pi*Z alleles were found out of 74 subjects, i.e. 148 alleles, then the frequency per 1000 alleles is calculated as follows: 3 × 1000/148= 20.27).

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Wheezing Children and Control Group

Children with wheezing episodes were statistically significantly younger compared to children in the control group (

Table 1).

The median AAT concentration did not differ between wheezing children and the control group: 144 (IQR 119.5 - 168) mg/dl in wheezers and 147.5 (IQR 126 - 165.25) mg/dl in controls, p=0.701. A total of 22.1% of wheezing children had food allergies and 26.9% of wheezing children had atopic dermatitis. The prevalence of food allergies and atopic dermatitis was significantly higher in wheezing children compared to the control group (

Table 2). A history of family smoking was more prevalent in the families of wheezing children compared to controls (33.79% vs. 6.76%, p<0.001).

Out of 145 children clinically identified as wheezers, 59 (40.69%) experienced their first wheezing episode, while 86 (59.31%) had recurrent episodes. Children with their first wheezing episode were significantly younger than those with repeated episodes (respectively 15 (IQR 5 – 24) months vs. 25 (IQR 12.75 – 36) months of age, p<0.001). The median AAT concentration did not differ between children with their first wheezing episode and children with repeated wheezing episode. A significantly higher percentage of children with their first wheezing episode needed hospitalization compared to children with repeated wheezing episodes (91.53% vs. 76.74%, p=0.021), although the length of stay in the hospital did not differ. Other clinical characteristics, such as the severity of wheezing, allergies, family history of smoking, and the presence of concomitant diseases, did not differ significantly between these subgroups. (

Table 3).

Out of 145 wheezing children 25 (17.2%) experienced wheezing without having a cold. Children wheezing without a cold were significantly older than those who experienced wheezing only when they had a cold (30 months (IQR 13.5–52) vs. 19 months (IQR 10–30), p=0.009). The median AAT concentration did not differ between children wheezing without having a cold and those wheezing only when they had a cold. A significantly higher percentage of children wheezing when having a cold needed hospitalization compared to children wheezing without a cold (88.33% vs. 56%, p<0.001), but the length of stay in the hospital did not differ. There was no difference in wheezing severity between children wheezing with a cold and those wheezing without a cold. Allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and a family history of smoking were more frequent among children wheezing without a cold compared to those wheezing only when they had a cold (

Table 4).

4.2. AAT Genotypes among Wheezing Children and Controls

Among 145 children diagnosed as wheezers, we found a normal PiMM genetic variant of AAT in 129 (88.97%), Pi*S in 3 (2.07%), Pi*Z in 10 (6.90%), and rare mutations were identified in 3 (2.07%) cases. Among control group’s children a normal PiMM genetic variant of AAT was found in 68 (91.89%). There was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of a normal PiMM genetic variant of AAT between children with wheezing and the control group children (p=0.496). Distribution of alpha-1 antitrypsin genotypes in wheezing and control groups are shown in

Table 5.

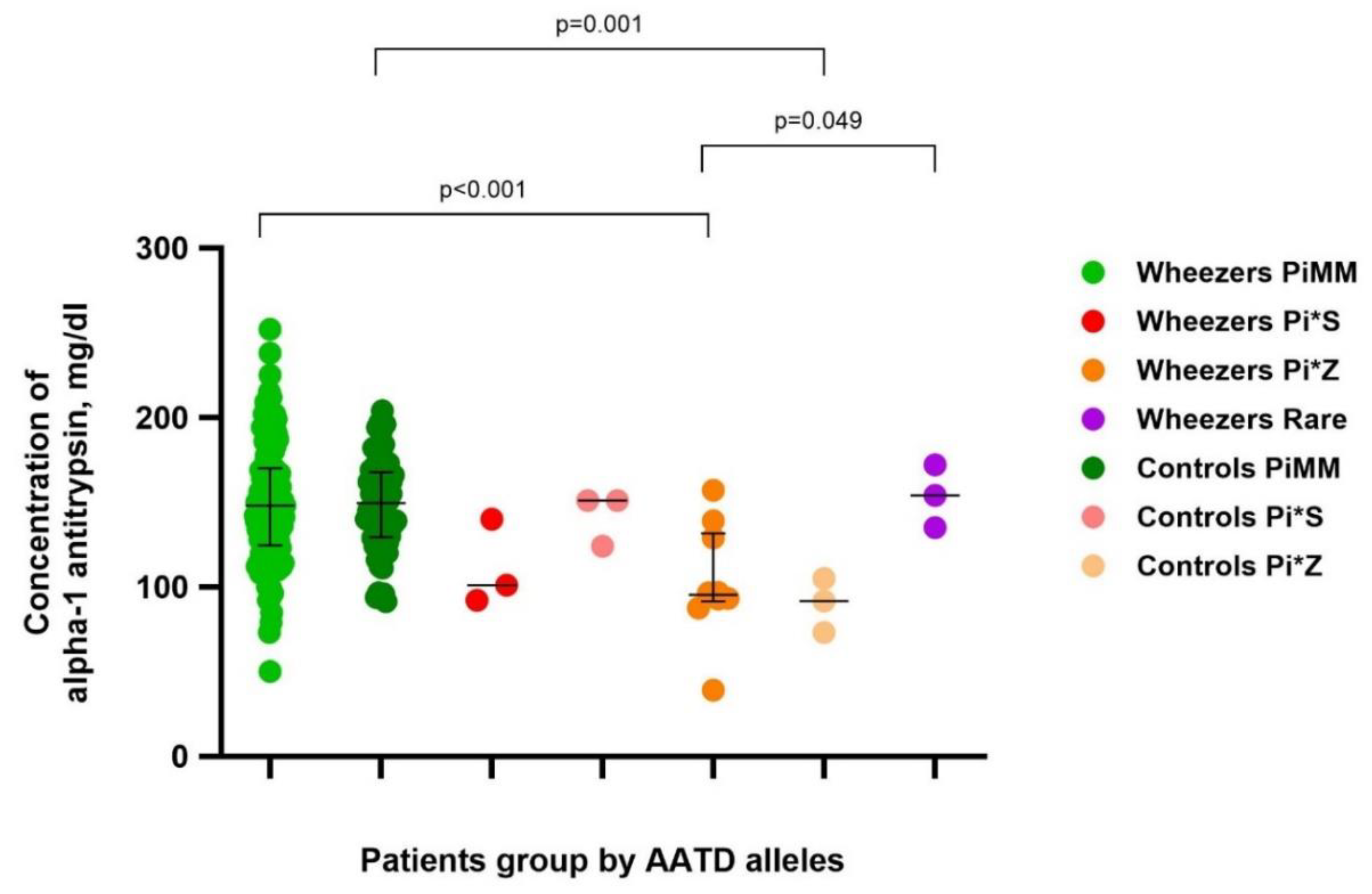

Plasma concentrations of AAT were in line with AAT genotypes.

The median AAT concentration in PiMM wheezing children (n=129) was 148.00 (IQR 124.5 – 170) mg/dl and in the control group (n=68) was 149.5 (IQR 129.25 – 167.75) mg/dl.

The median AAT concentration in Pi*S wheezing children (n=3) was 101 mg/dl and in the control group (n=3) was 151 mg/dl.

The median AAT concentration in Pi*Z wheezing children (n=10) was 95.3 (IQR 91.45 – 131.5) mg/dl and in the control group (n=3) was 91.7 mg/dl. The median AAT concentration in wheezing children with rare mutations (n=3) was 154 mg/dl.

The levels of AAT in wheezers and controls with deficient variants of AAT are shown in

Figure 1.

There was no statistically significant difference in AAT levels between wheezers and controls in groups by genotype.

Wheezers with the PiZ genotype had lower AAT concentrations compared to those with the PiMM genotype (p<0.001) and those with rare mutations (p=0.049). Wheezers with the PiS genotype also had lower AAT concentrations compared to those with the PiMM genotype, but difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.056).

Controls with the PiZ genotype had lower AAT concentrations compared to those with the PiMM genotype (p=0.001) (

Figure 1).

Among the wheezing children, 43 (29.66%) experienced mild wheezing, 65 (44.83%) experienced moderate wheezing, and 37 (25.52%) experienced severe wheezing. No statistically significant difference in AAT concentration and prevalence of AATD alleles was found between groups of patients categorized by disease severity (

Table 6).

4.3. Pi*Z and Pi*S Frequencies in Comparison with Other Cohorts

The Pi*Z allele was found to be statistically significantly more frequent in Lithuanian wheezing children than in individuals from Lithuanian non-disease specific epidemiological studies (NDSES).

The frequency of Pi*S and Pi*Z alleles among wheezing children is close to the frequency of these alleles among COPD patients: Pi*S 10.3 (95% CI: 4.0- 16.6) vs. 15.8 (95% CI: 6.92-24.6) and Pi*Z 44.8 (95% CI: 32.1-57.5) vs. 46.1 (95% CI: 31.1-60.9).

The Pi*Z allele in wheezing group is significantly different from that of the control group (44.8 (95% CI: 32.1 - 57.5) vs. 20.27 (95% CI: 11.53 - 29.01). And on the contrary, more Pi*S mutational variants were found in the control group than in the wheezing group (20.27 (95% CI: 11.53 – 29.01) vs. 10.3 (95% CI: 4.0- 16.6) (

Table 7).

5. Discussion

Childhood wheezing illness appears to be associated with an increased risk of developing COPD in adulthood [

13,

14,

15]. This association may be due to several factors. For example, children with wheezing illnesses may be more sensitive to environmental factors such as tobacco smoke, air pollution, and respiratory infections [

16,

17,

18]. Persistent inflammation from repeated wheezing episodes can lead to structural changes in the lungs, including airway remodelling and reduced elasticity, which are key characteristics of COPD. Overall, the relationship between childhood wheezing and adult COPD highlights the importance of early identification and management of respiratory issues in children to potentially mitigate long-term adverse outcomes on lung health.

Children who experience wheezing may have underlying genetic factors that predispose them to both early-life respiratory issues and the development of COPD later in life. Certain genetic variants, like those in the SERPINA1 gene associated with AATD, can contribute to both childhood wheezing and adult airways disorders. However, the existing data are controversial. For instance, several studies have reported an association between AATD and adult bronchial asthma [

19,

20,

21]. In contrast, the relationship between AATD and childhood bronchial asthma remains debated [

22,

23,

24]. Our study, based on the ALSPAC cohort, did not show an association between SERPINA1 gene polymorphisms and the risk of developing bronchial asthma in school-aged children [

25].

Our current results show that the frequency of the Pi*Z allele in wheezing small children is significantly higher than in the control group (44.8% [95% CI: 32.1-57.5] vs. 20.27% [95% CI: 11.53-29.01], respectively). Additionally, the prevalence of the Pi*Z allele in these children (44.8 alleles per 1000) is higher compared to general population estimates based on data from 21 European countries [

26].

Interestingly, we found more Pi*S variants in the control group than in the wheezing group. This observation might be related to the fact that the primary pathologies in the control group, which necessitated surgeries, were conditions such as abdominal wall and inguinal hernias (52.7%), port-wine stains (14.9%), benign tumors (8.1%), vascular malformations (8.1%), cystic formations (6.8%), hemorrhoidal nodes (2.7%), and other individual cases (6.8%). It is possible that these pathologies are associated with AATD, as AAT is a major inhibitor of neutrophil proteases and certain metalloproteases involved in remodelling and repairing connective tissue. This connection could explain the higher prevalence of PiS variants in the control group [

27,

28].

We also compared the frequency of Pi*S and Pi*Z alleles among wheezing children with previously reported data on the frequencies of these alleles in COPD patients from the Central-Eastern European AAT Network and non-disease-specific epidemiological studies performed in Lithuania [

9,

10]. The frequency of the Pi*S and Pi*Z alleles among wheezing children was like the frequency observed among COPD patients: PiS 10.3% (95% CI: 4.0-16.6) vs. 15.8% (95% CI: 6.92-24.6) and PiZ 44.8% (95% CI: 32.1-57.5) vs. 46.1% (95% CI: 31.1-60.9). Furthermore, the Pi*Z allele was significantly more common in wheezing children compared to data from non-disease-specific epidemiological studies, with a frequency of 44.8% (95% CI: 32.1-57.5) vs. 13.6% (95% CI: 10.7-17.4).

Taken together, findings from our single center cohort of small children diagnosed as wheezers suggest the necessity of verifying the role of AAT heterozygous mutations in the manifestation of wheezing and the further development of COPD. Understanding how these genetic variations contribute to early respiratory issues can provide valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying both childhood wheezing and adult COPD.

By examining larger and more diverse cohorts, researchers can better determine the specific impact of heterozygous AAT mutations on respiratory health. This includes understanding how these mutations affect AAT levels and lung function from an early age. Moreover, early identification of children with AAT mutations could allow for targeted interventions aimed at preventing the progression of wheezing to more severe respiratory conditions.

6. Conclusion

With a clearer understanding of the genetic factors involved, it may be possible to develop preventative strategies or treatments that can mitigate the risk of developing COPD in later life for those identified as genetically predisposed. Overall, ongoing research is crucial to fully elucidate the relationship between AAT heterozygous mutations, early-life wheezing, and the risk of developing COPD, ultimately contributing to better prevention, diagnosis, and treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to all the families, doctors and nurses who participated in this study. Special thanks to professor S.Janciauskiene from Department of Pulmonary and Infectious Diseases and BREATH German Center for Lung Research (DZL), Hannover Medical School, thanks to pediatricians from Vilnius city clinical hospital and pediatricians from other cities who helped us to collect the samples and wheezing group: Prof. E.Vaitkeviciene, V.Miseviciene, V.Lukosiene, R.Sabaliene, A.Storpirstiene, J.Suliauskaite. The sincerest thanks to team from the National Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases in Warsaw, Poland for their help with genetic analysis.

Ethical Considerations

The study was carried out with the permission of the Lithuanian Bioethics Committee (L-16-07/2).

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Kueppers, F.; Andrake, M.D.; Xu, Q.; Dunbrack, R.L.; Kim, J.; Sanders, C.L. Protein modeling to assess the pathogenicity of rare variants of SERPINA1 in patients suspected of having Alpha 1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. BMC Med Genet. 2019, 20, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamesch, K.; Mandorfer, M.; Pereira, V.M.; Moeller, L.S.; Pons, M.; Dolman, G.E.; et al. Liver Fibrosis and Metabolic Alterations in Adults With alpha-1-antitrypsin Deficiency Caused by the Pi*ZZ Mutation. Gastroenterology. 2019, 157, 705–719.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Pérez, J.M.; Ramos-Díaz, R.; Vaquerizo-Pollino, C.; Pérez, J.A. Frequency of alleles and genotypes associated with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency in clinical and general populations: Revelations about underdiagnosis. Pulmonology. 2023, 29, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piras, B.; Ferrarotti, I.; Lara, B.; Martinez, M.T.; Bustamante, A.; Ottaviani, S.; et al. Clinical phenotypes of Italian and Spanish patients with α 1 -antitrypsin deficiency. Eur Respir J. 2013, 42, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foreman, M.G.; Wilson, C.; DeMeo, D.L.; Hersh, C.P.; Beaty, T.H.; Cho, M.H.; et al. Alpha-1 Antitrypsin PiMZ Genotype Is Associated with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Two Racial Groups. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017, 14, 1280–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curjuric, I.; Imboden, M.; Bettschart, R.; Caviezel, S.; Dratva, J.; Pons, M.; et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: From the lung to the heart? Atherosclerosis. 2018, 270, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoller, H.; Wagner, S.; Tilg, H. Is Heterozygosity for the Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Risk Allele Pi∗MZ a Disease Modifier or Genetic Risk Factor? Gastroenterology. 2020, 159, 433–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueira Gonçalves, J.M.; Martínez Bugallo, F.; García-Talavera, I.; Rodríguez González, J. Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Deficiency Associated With Null Alleles. Arch Bronconeumol Engl Ed. 2017, 53, 700–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chorostowska-Wynimko, J. The incidence of severe alpha-1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency alleles in COPD patients — Preliminary results from Central Eastern European (CEE) AAT NETWORK. Eur Respir Soc 2013, 42 Suppl 57. Available from: https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/42/Suppl_57/P541.article-info.

- Serapinas, D. Alfa-1 antitripsino poveikis monocitų aktyvumui in vitro bei genotipo įtaka lėtinės obstrukcinės plaučių ligos ypatumams [Internet]. 2009. Available from: https://lsmu.lt/cris/entities/publication/d6be1d77-a7b4-4950-8536-4e60723e2ab6/details.

- Beckman, L.; Sikström, C.; Mikelsaar, A.V.; Krumina, A.; Kučinskas, V.; Beckman, G. α1-Antitrypsin (PI) Alleles as Markers of Westeuropean Influence in the Baltic Sea Region. Hum Hered. 1999, 49, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stakisaitis, D.; Basys, V.; Benetis, R. Does alpha-1-proteinase inhibitor play a protective role in coronary atherosclerosis? Med Sci Monit Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2001, 7, 701–711. [Google Scholar]

- Tagiyeva, N.; Fielding, S.; Devereux, G.; Turner, S.; Douglas, G. Childhood wheeze – A risk factor for COPD? A 50-year cohort study. In: 61 Epidemiology [Internet]. European Respiratory Society; 2015 [cited 2024 May 27]. p. OA2000. Available from: http://erj.ersjournals.com/lookup/doi/10.1183/13993003.congress-2015.OA2000.

- Berry, C.E.; Billheimer, D.; Jenkins, I.C.; Lu, Z.J.; Stern, D.A.; Gerald, L.B.; et al. A Distinct Low Lung Function Trajectory from Childhood to the Fourth Decade of Life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016, 194, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerkhof, M.; Boezen, H.M.; Granell, R.; Wijga, A.H.; Brunekreef, B.; Smit, H.A.; et al. Transient early wheeze and lung function in early childhood associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease genes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014, 133, 68–76.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piitulainen, E.; Tornling, G.; Eriksson, S. Effect of age and occupational exposure to airway irritants on lung function in non-smoking individuals with alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency (PiZZ). Thorax. 1997, 52, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eden, E.; Mitchell, D.; Mehlman, B.; Khouli, H.; Nejat, M.; Grieco, M.H.; et al. Atopy, Asthma, and Emphysema in Patients with Severe α -1-Antitrypysin Deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997, 156, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMeo, D.L.; Sandhaus, R.A.; Barker, A.F.; Brantly, M.L.; Eden, E.; McElvaney, N.G.; et al. Determinants of airflow obstruction in severe alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Thorax. 2007, 62, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-González, E.; Hernández-Pérez, J.M.; Pérez, J.A.P.; Pérez-García, J.; Herrera-Luis, E.; González-Pérez, R.; et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and Pi*S and Pi*Z SERPINA1 variants are associated with asthma exacerbations. Pulmonology. 2023, S2531043723000910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, E. Asthma and COPD in Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. Evidence for the Dutch Hypothesis. COPD J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2010, 7, 366–374. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Pérez, J.M.; Martín-González, E.; González-Carracedo, M.A. Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency and SERPINA1 Variants Could Play a Role in Asthma Exacerbations. Arch Bronconeumol. 2023, 59, 416–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, I.C.J.; Toro, A.D.C.; Ribeiro, J.D.; Bertuzzo, C.S. Alpha 1 antitrypsin (A1AT) deficiency in children with asthma in Brazil. Eur Respir J 2003, 22 (Suppl. 45), 3128. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello, M.; Frizzelli, A.; Pisi, R.; Fantin, A.; Ghirardini, M.; Marchi, L.; et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is significantly associated with atopy in asthmatic patients. J Asthma. 2022, 59, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colp, C.; Pappas, J.; Moran, D.; Liebemuin, J. Variants of α1-Antitrypsin in Puerto Rican Children With Asthma. Chest. 1993, 103, 812–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLuca, D.S.; Poluzioroviene, E.; Taminskiene, V.; Wrenger, S.; Utkus, A.; Valiulis, A.; et al. SERPINA1 gene polymorphisms in a population-based ALSPAC cohort. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019, 54, 1474–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, I. Estimated numbers and prevalence of PI*S and PI*Z alleles of 1-antitrypsin deficiency in European countries. Eur Respir J. 2006, 27, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooptu, B.; Ekeowa, U.I.; Lomas, D.A. Mechanisms of emphysema in 1-antitrypsin deficiency: Molecular and cellular insights. Eur Respir J. 2009, 34, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.A.; Pani, A.M.; Mervis, C.B.; Rios, C.M.; Kistler, D.J.; Gregg, R.G. Alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency alleles are associated with joint dislocation and scoliosis in Williams syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2010, 154C, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).