Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

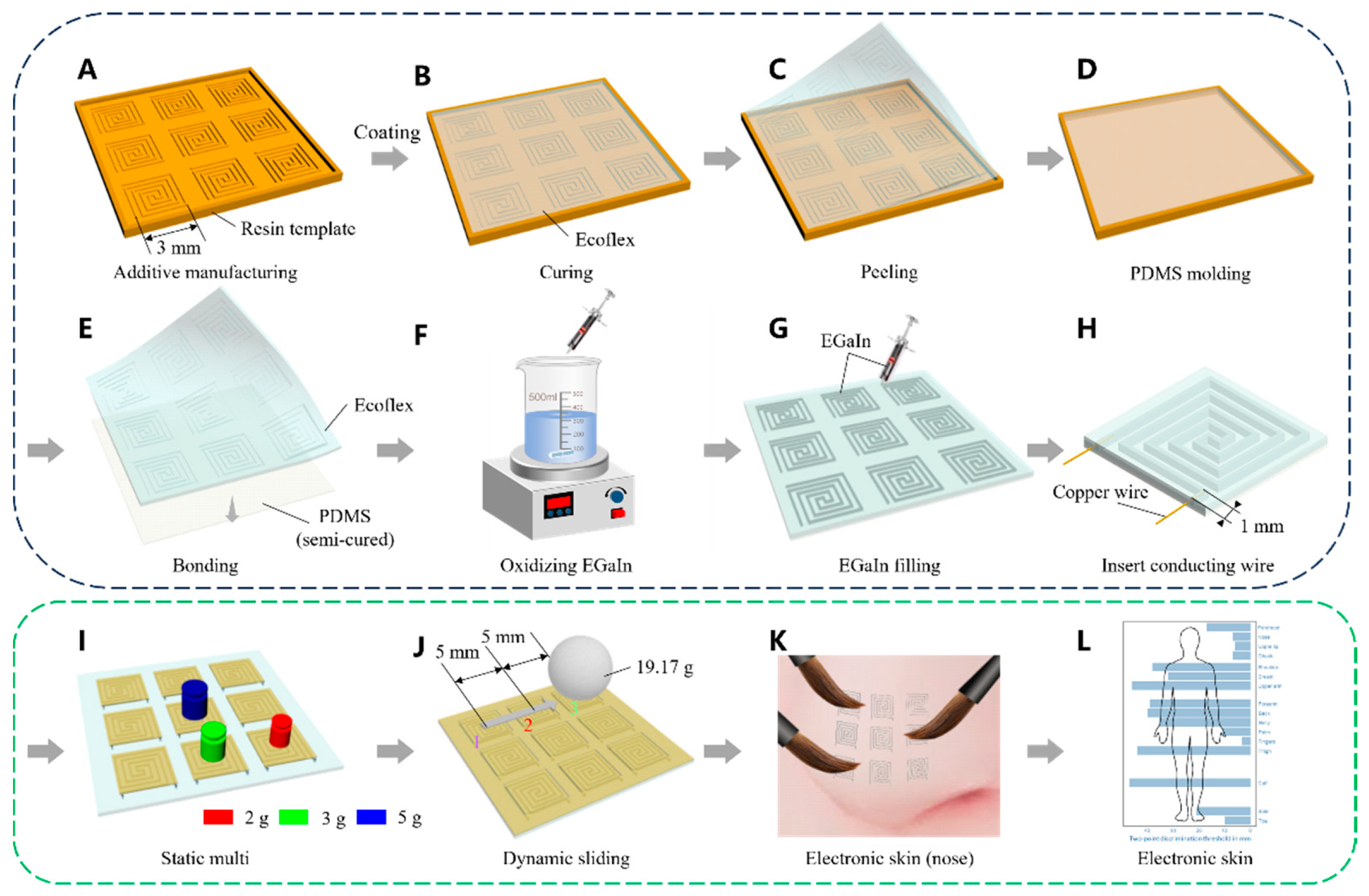

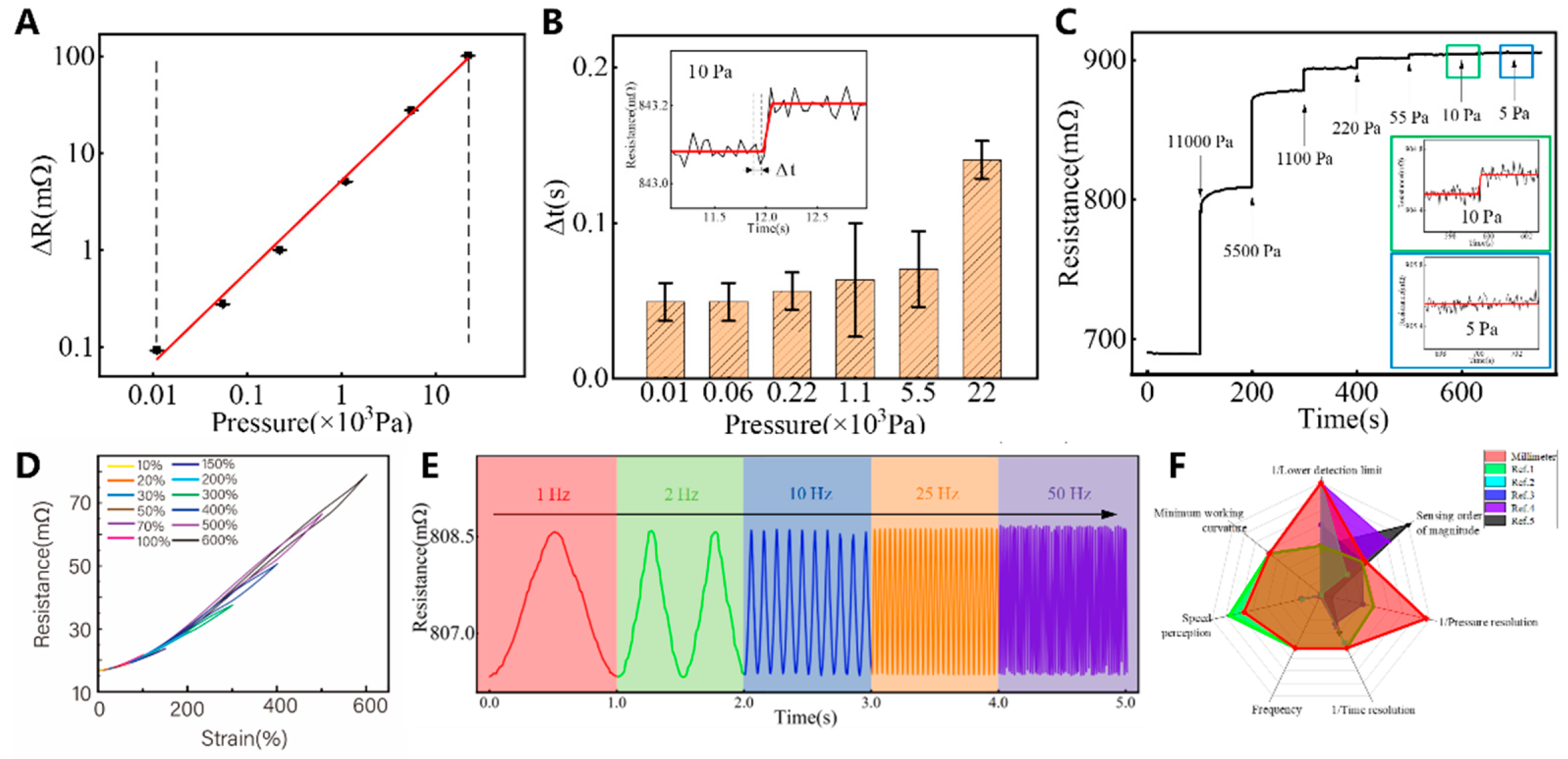

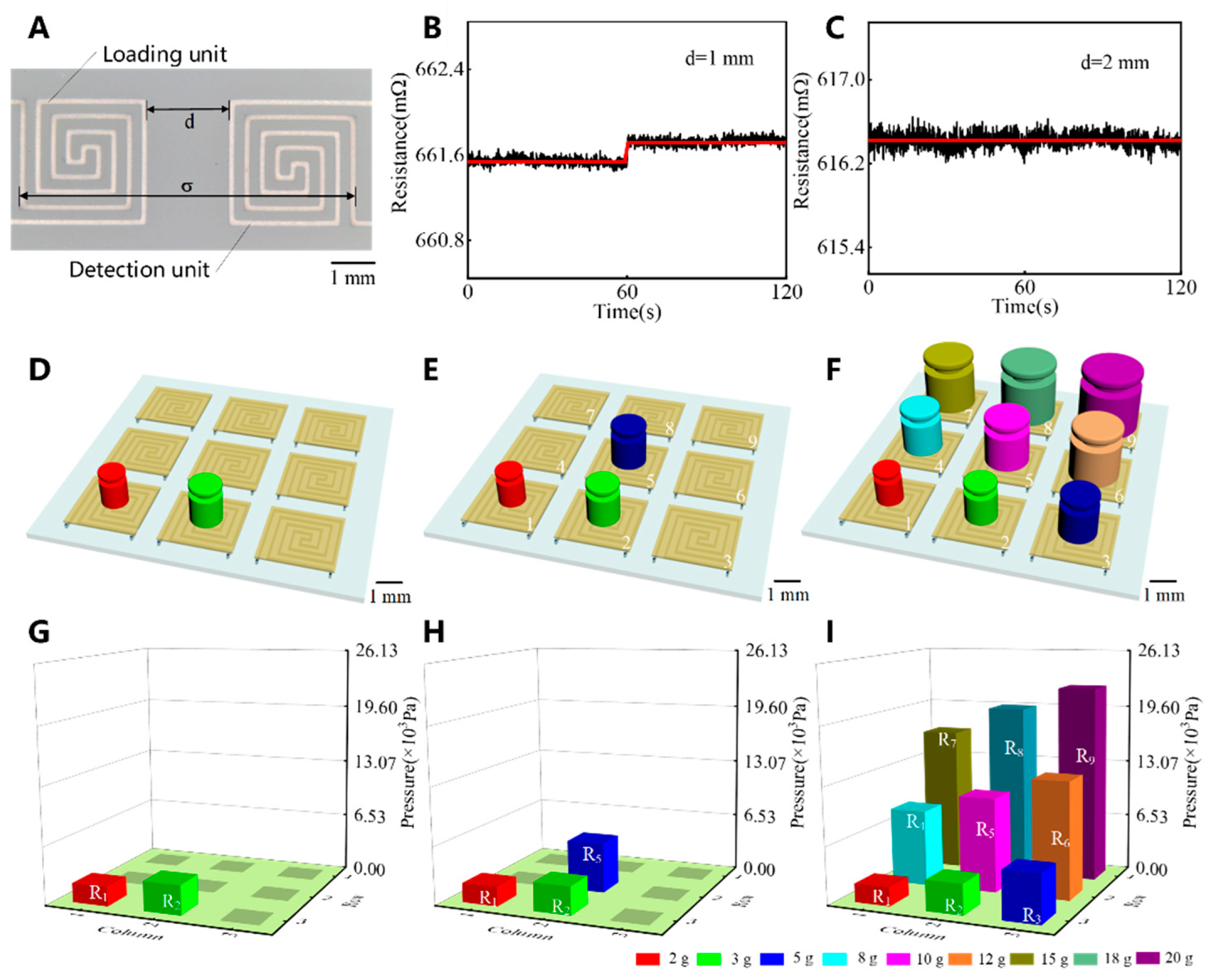

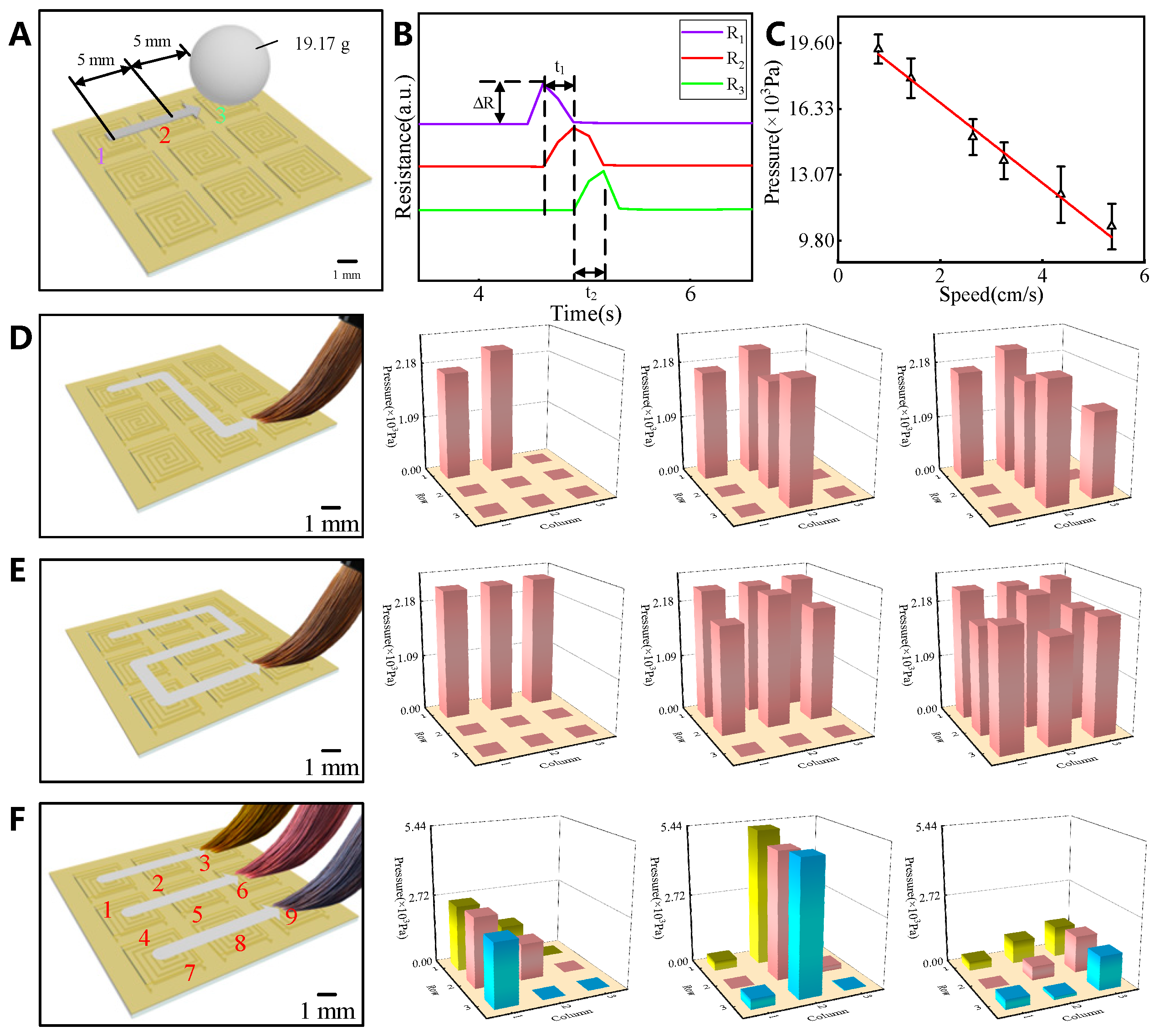

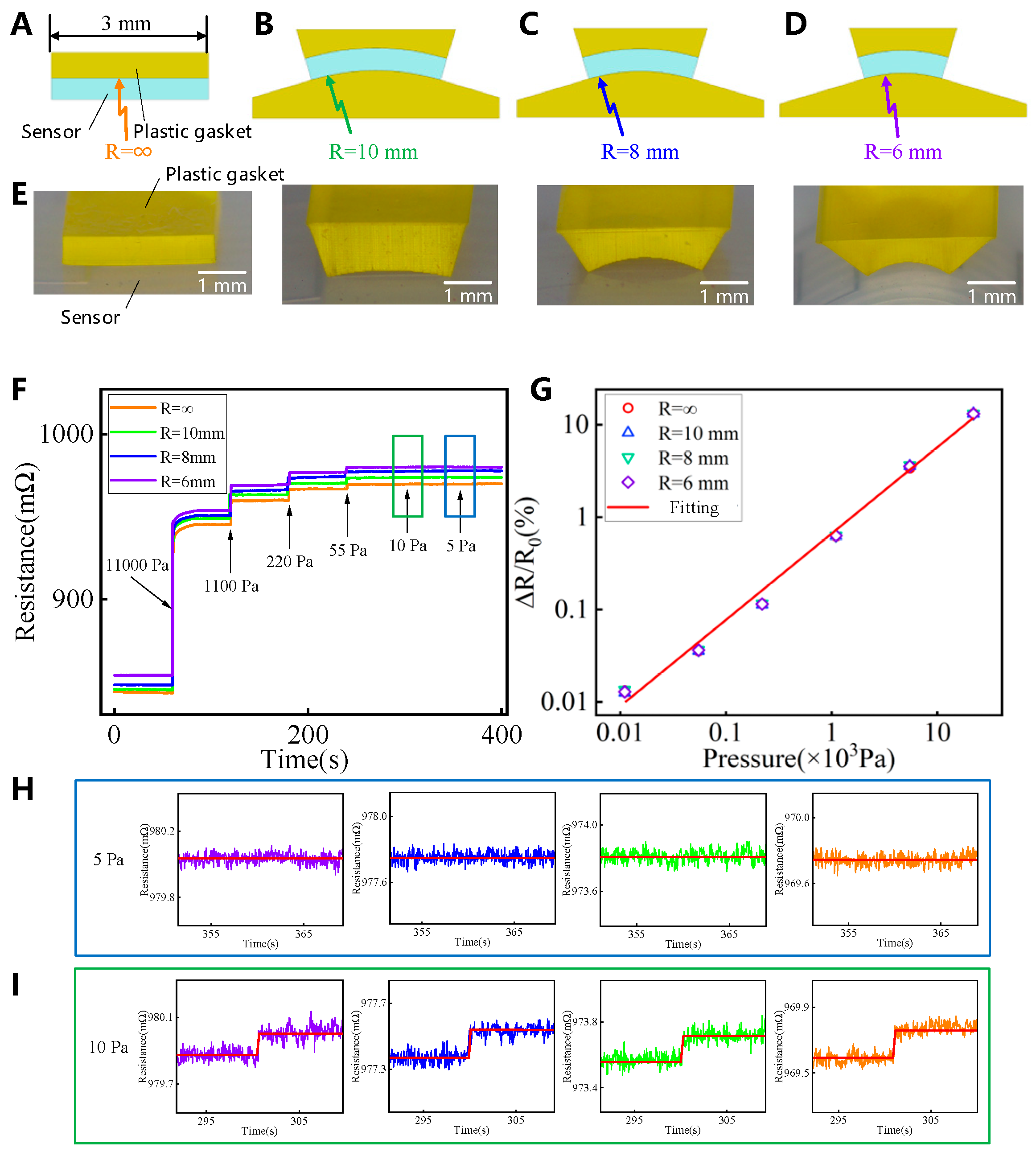

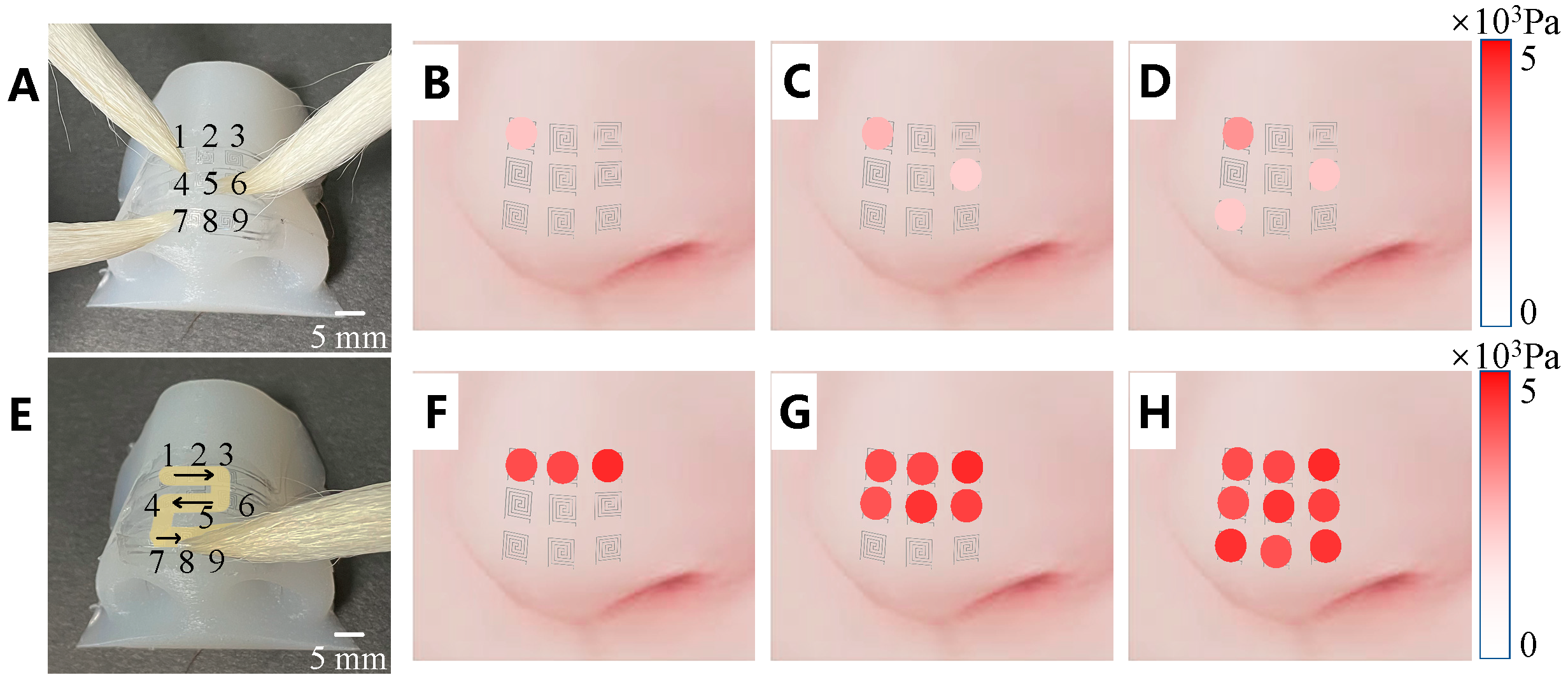

Electronic skin is widely employed in multiple applications such as health monitoring, robot tactile perception, and bionic prosthetics. In this study, we fabricated millimeter-scale electronic skin featuring compact sensing units using Boston Micro Fabrication S130 (a high-precision additive manufacturing device) and the template removal method. We used a gallium-based liquid metal and achieved an inner channel diameter of 0.1 mm. The size of the sensing unit was 3 × 3 mm². This unit exhibited a wide linear sensing range (10–22000 Pa) and high pressure resolution (10 Pa) even on an ultracurved surface (radius of curvature was 6 mm). Sliding was successfully detected at speeds of 8–54 mm/s. An artificial nose with nine sensing units was fabricated, and it exhibited excellent multitouch and sliding trajectory recognition capabilities. This confirmed that the electronic skin functioned normally even on an ultracurved surface.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

| Position | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.20 | 1.52 | 2.14 |

| 6 | - | 0.94 | 1.13 |

| 7 | - | - | 1.10 |

| Position | F | G | H |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.49 | 3.49 | 3.49 |

| 2 | 3.57 | 3.57 | 3.57 |

| 3 | 4.12 | 4.12 | 4.12 |

| 4 | - | 3.35 | 3.35 |

| 5 | - | 3.92 | 3.92 |

| 6 | - | 3.69 | 3.69 |

| 7 | - | - | 3.99 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yunru Yu, Jiahui Guo, Lingyu Sun, Xiaoxuan Zhang, and Yuanjin Zhao, Microfluidic Generation of Microsprings with Ionic Liquid Encapsulation for Flexible Electronics, Research 2019;(9) 6906275. [CrossRef]

- Kirthika Senthil Kumar, Po-Yen Chen, and Hongliang Ren, A Review of Printable Flexible and Stretchable Tactile Sensors, Research 2019; (32) 3018568. [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Yi, H.; Ge, K.; Zhan, L.; Gao, Y.; Li, Z.; Ji, H.; Li, M.; Feng, H. Additively Manufactured Flexible Electronics Filled with Ionic Liquid for Cryogenic Pressure Sensing. Adv Devices Instrum 2024, 5, 0052. [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Yi, H.; Gao, Y.; Cao, Y.; Ge, K.; Kuang, T.; Ji, H.; Li, M.; Feng, H. High-Sensitivity and Damage Redundant Detection Capable Gel-State [BMIM][BF4] Electronic Skin for Aerospace Applications. Supramolecular Materials 2024, 100077. [CrossRef]

- Huanhuan Feng, Yaming Liu, Liang Feng, Limeng Zhan, Shuaishuai Meng, Hongjun Ji, Additively Manufactured Flexible Electronics with Ultrabroad Range and High Sensitivity for Multiple Physiological Signals’ Detection, Research 2022; (11) 9871489. [CrossRef]

- Yue Li, Zhiguang Cao, Tie Li, Fuqin Sun, Yuanyuan Bai, Qifeng Lu, Shuqi Wang, Xianqing Yang, Manzhao Hao, Ning Lan, Ting Zhang, Highly Selective Biomimetic Flexible Tactile Sensor for Neuroprosthetics, Research 2020; (11) 8910692. [CrossRef]

- Yao Lu, Xinyu Qu, Wen Zhao, Yanfang Ren, Weili Si, Wenjun Wang, Qian Wang, Wei Huang, Xiaochen Dong, Highly Stretchable, Elastic, and Sensitive MXene-Based Hydrogel for Flexible Strain and Pressure Sensors, Research 2020; (13) 2038560. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Xiao D, Liu P, Liao Q, Ruan Q, Huang C, Liu L, Li D, Zhang X, Li W, Tang K, Wu Z, Wang G, Wang H, Chu PK. Nanostructured Conductive Polypyrrole for Antibacterial Components in Flexible Wearable Devices. Research 2023; 6, (0) 074. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wei Y, Yang Y, Zheng L, Luo L, Gao J, Jiang H, Song J, Xu M, Wang X, Huang W. The Soft-Strain Effect Enabled High-Performance Flexible Pressure Sensor and Its Application in Monitoring Pulse Waves. Research 2022; 2022, 0002. [CrossRef]

- Shuo Wang, Mengmeng Zhao, Yibo Yan, Peng Li, Wei Huang. Flexible Monitoring, Diagnosis, and Therapy by Microneedles with Versatile Materials and Devices toward Multifunction Scope. Research 2023; 6 (10) 0128. [CrossRef]

- YANG J C, MUN J, KWON S Y, et al. Electronic Skin: Recent Progress and Future Prospects for Skin-Attachable Devices for Health Monitoring, Robotics, and Prosthetics. Adv. Mater 2019;31 (48) 1904765. [CrossRef]

- YANG J, CHENG W, KALANTAR-ZADEH K. Electronic Skins Based on Liquid Metals. Proceedings of the IEEE 2019;107 (10) 2168-2184. [CrossRef]

- XIONG Y, HAN J, WANG Y, et al. Emerging Iontronic Sensing: Materials, Mechanisms, and Applications. Research 2022;2022 1-35. [CrossRef]

- YUAN Z, HAN S, GAO W, et al. Flexible and Stretchable Strategies for Electronic Skins: Materials, Structure, and Integration. ACS Appl. Electronic Materials 2022;4 (1) 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, H.; Xing, C.; Guo, H.; Qiu, D.; Yang, H.; Song, C.; Cheng, H. Stretchable 3D Wideband Dipole Antennas from Mechanical Assembly for On-Body Communication. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022; 14 (10) 12855−12862. [CrossRef]

- Chung, H. U.; Kim, B. H., Binodal, wireless epidermal electronic systems with in-sensor analytics for neonatal intensive care. Science 2019; 363 (6430) eaau0780. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xie, Z.; Yu, Y.; Lee, J. Skin-integrated wireless haptic interfaces for virtual and augmented reality. Nature 2019;575 (7783) 473−479. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, W.; Ma, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Wang, P.; Chen, Y.; Feng, X. Flexible Ultrasonic Patch for Accelerating Chronic Wound Healing. Adv. Healthcare Mater 2021; 10 (19) No. 2100785. [CrossRef]

- TENG L, YE S, HANDSCHUH-WANG S, et al. Liquid Metal-Based Transient Circuits for Flexible and Recyclable Electronics. Adv. Functional Mater 2019;29 (11) 1808739. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Kramer, C. Majidi and R. J. Wood, Wearable tactile keypad with stretchable artificial skin. IEEE 2011; pp. 1103-1107. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Chen G, Sun L, Ye F, Shen X, Zhao Y. Claw-inspired microneedle patches with liquid metal encapsulation for accelerating incisional wound healing. Chem Eng J 2021;406 126741. [CrossRef]

- Yifan Huang, Fan Yang, Sanhu Liu, Rongguo Wang, Jinhong Guo, Xing Ma, Liquid Metal-Based Epidermal Flexible Sensor for Wireless Breath Monitoring and Diagnosis Enabled by Highly Sensitive SnS2 Nanosheets, Research 2021; (13) 9847285. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG Y, LIU S, MIAO Y, et al. Highly Stretchable and Sensitive Pressure Sensor Array Based on Icicle-Shaped Liquid Metal Film Electrodes[J]. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020;12(25) 27961-27970. [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Wang, X. L.; Yu, W. Z.; Tang, J. B.; Liu, J. A highly conductive and stretchable wearable liquid metal electronic skin for long-term conformable health monitoring. Sci. China: Technol. Sci 2018; 61 (7) 1031−1037. [CrossRef]

- Pan, C. F.; Kumar, K.; Li, J. Z.; Markvicka, E. J.; Herman, P. R.; Majidi, C. Visually Imperceptible Liquid-Metal Circuits for Trans parent, Stretchable Electronics with Direct Laser Writing. Adv. Mater 2018; 30 (12) 1706937. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. G.; Alrowais, H.; Brand, O. 3D-Integrated and Multifunctional All-Soft Physical Microsystems Based on Liquid Metal for Electronic Skin Applications. Adv. Electron. Mater 2018; 4 (2) 1700434. [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y. G.; Koo, J. B.; Park, N. M.; Oh, J. Y.; Na, B. S.; Lee, S. S.; Ahn, S. D.; Park, C. W. Freely Deformable Liquid Metal Grids as Stretchable and Transparent Electrodes. IEEE Trans Electron 2017; 64 (12) 5157−5162. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Q.; Sun, N.; Wen, Z.; Cheng, P.; Zheng, H. C. Liquid-Metal-Based Super-Stretchable and Structure-Designable Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Wearable Electronics. ACS Nano 2018;12 (2) 2027−2034. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. G.; Lee, G. Y.; Jang, J.; Yun, S. M.; Kim, E.; Park, J. U. Liquid Metal-Based Soft Electronics for Wearable Healthcare. Adv. Healthcare Mater 2021;10 (17) 2002280. [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.; Song, B. G.; Yang, H. I.; Kim, D. M.; Lee, C. S.; Park,M.; Chung, C. M. Smart Passivation Materials with a Liquid Metal Microcapsule as Self-Healing Conductors for Sustainable and Flexible Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater 2018;28 (22) 1800110. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C. B.; Arutselvan, K.; Liu, Y.; Armstrong, D.; Lin, Y.L.; Khan, M. R.; Genzer, J.; Dickey, M. D. Stretchable Capacitive Sensors of Torsion, Strain, and Touch Using Double Helix Liquid Metal Fibers. Adv. Funct. Mater 2017;27 (20) 1605630. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, J. J.; Luo, Z. B.; Zhang, J. Y.; Li, L.; Su, Y.; Gao, X.; Li, Y. T.; Tang, W.; Cao, C. J.; Liu, Q. H.; Wang, L.; Li, H. Superelastic, Sensitive, and Low Hysteresis Flexible Strain Sensor Based on Wave-Patterned Liquid Metal for Human Activity Monitoring. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020; 12 (19) 22200−22211. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y. J.; Ota, H.; Schaler, E. W.; Chen, K.; Zhao, A.; Gao, W. Wearable Microfluidic Diaphragm Pressure Sensor for Health and Tactile Touch Monitoring. Adv. Mater 2017;29 (39) 1701985. [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Kim, H.; Kang, I.; Park, H.; Jung, J.; Lee, H. Universal assembly of liquid metal particles in polymers enables elastic printed circuit board. Science 2022;378 (6620) 637−641. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, M.; Liu, S.; Yuan, M.; Wu, J.; Yu, M.; Teng, L.; Xu, Z.; Guo, J.; Li, G.; Liu, Z.; Ma, X. Three-dimensional flexible electronics using solidified liquid metal with regulated plasticity. Nat. Electron 2023; 6 154−163. [CrossRef]

- Zhan L, Cao Y, Gao Y, et al. Additively Fabricated Electronic Skin with High Performance in Dynamic Sensing as Human Skin. ACS Appl. Electronic. Materials 2023; 5 (4) 2017-2025. [CrossRef]

- LIN Y, GORDON O, KHAN M R, et al. Vacuum filling of complex microchannels with liquid metal. Lab Chip 2017;17 (18) 3043-3050. [CrossRef]

- S. Choi, S. I. Han, D. Kim, T. Hyeon, D.-H. Kim, Chem. High-performance stretchable conductive nanocomposites: materials, processes, and device applications. Soc. Rev 2019;48, 1566. [CrossRef]

- G. Yun, S.-Y. Tang, H. Lu, S. Zhang, M. D. Dickey, W. Li, Microfluidic Mass Production of Stabilized and Stealthy Liquid Metal Nanoparticles. Small Sci 2021; 1 2000080. [CrossRef]

- R. W. Style, R. Tutika, J. Y. Kim, M. D. Bartlett, Flexible thermoelectric generators with inkjet-printed bismuth telluride nanowires and liquid metal contacts. Adv. Funct. Mater 2021; 31 2005804. [CrossRef]

- Q. Gui, Y. He, Y. Wang, Soft Electronics Based on Liquid Conductors. Adv. Electron. Mater 2021; 7 2000780. [CrossRef]

- L. Sheng, J. Zhang, J. Liu, Diverse transformations of liquid metals between different morphologies, Adv. Mater 2014;26, 6036e6042. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, L. Sheng, J. Liu, Synthetically chemical-electrical mechanism for controlling large scale reversible deformation of liquid metal objects, Sci. Rep 2014; 4 7123. [CrossRef]

- J. Tang, X. Zhao, J. Li, R. Guo, Y. Zhou, J. Liu, Gallium-based liquid metal amalgam: transitional-state metallic mixtures (TransM2ixes) with enhanced and tunable electrical, thermal, and mechanical properties, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017; 9 35977e35987. [CrossRef]

- H. Chang, R. Guo, Z. Sun, H. Wang, Y. Hou, Q. Wang, W. Rao, J. Liu, Direct writing and repairable paper flexible electronics using nickel-liquid metal ink, Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2018; 5 1800571. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, B. Yuan, S. Liang, R. Guo, W. Rao, X. Wang, H. Chang, Y. Ding, J. Liu, L. Wang, PLUS-M: a porous liquid-metal enabled ubiquitous soft material, Mater. Horiz 2017; 5 (222) 229. [CrossRef]

- Dickey, M. D. Stretchable and Soft Electronics using Liquid Metals. Adv. Mater 2017; 29 (27) 1606425. [CrossRef]

- XI W, YEO J C, YU L, et al. Ultrathin and Wearable Microtubular Epidermal Sensor for Real-Time Physiological Pulse Monitoring. Adv. Mater 2017; 2 (5) 1700016. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Yang S, Liu Z, et al. Patterning sub-30 µm liquid metal wires on PDMS substrates via stencil lithography and pre-stretching. Journal of micromechanics and microengineering 2019; 29 (9). [CrossRef]

- Park Y G, AN H S, KIM J Y, et al. High-resolution, reconfigurable printing of liquid metals with three-dimensional structures. Sci. Adv 2019; 5 (6) 2844. [CrossRef]

- Zhan L M , Cao Y, Gao Y F, Additively Fabricated Electronic Skin with High Performance in Dynamic Sensing as Human Skin, ACS Applied Electronic Materials 2023; 5 (4) 2017-2025. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).