1. Introduction

Chorea is a neurological condition characterized by random and flowing movements, with a dance-like appearance, usually switching quickly and irregularly between limbs, trunk, neck or face. [

1,

2]. Insidious onset, in children younger than 5 years old, is more linked to genetic causes. Conversely, acquired pathogenesis relates to acute outbreak after 5 years of age.

In the pediatric population, Sydenham’s Chorea (SC) represents the most common cause of acute chorea. Etiology is due to an autoimmune sequelae that occurs after a group A beta hemolytic streptococcal (GABHS) infection. Age of onset is between 8 and 9 years, mostly in females. SC has mainly a bilateral involvement, but in about 20-35% cases it can be unilateral. Other neurological, and also psychiatric findings can be associated with chorea movements, such as hypotonia, psychomotor agitation, hypometric saccades, anxiety, obsessive compulsive symptoms and attention and hyperactivity syndrome. Throat culture showing streptococcal infection, positive anti-streptolysin-0 or anti DNAse antibodies lead to diagnosis. Clinical resolution is often seen within 2 years [

3].

Autoimmune disorders seem to have a large impact on the onset of chorea in children (females are usually the most affected). Infact, as well as what happens in GSBHS infection, also in autoimmune encephalitis and in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus syndrome (SLE) (associated with Antiphospholipid Syndrome; APS) there is antibodies production headed towards neuronal structures.

Anti NMDAR encephalitis are the most represented in the etiology of chorea, usually emerging after viral infections. Clinical picture is characterized by prodromal influenza-like symptoms and then onset of psychiatric elements such as psychosis, disinhibition, sleep disorders, seizures and catatonia. Lingual, orofacial dyskinesia, ballism and dystonia can also be described in addition to chorea. Anti NMDAR antibodies can appear 1-4 weeks after viral infection [

3,

4,

5].

As well as autoimmune ones, also viral encephalitis play a role in the genesis of this neurological abnormality. Herpes symplex virus, mumps, varicella parvovirus B19 and measles are typically responsible for neuronal involvement. In addition, other agents’ presence as Borrelia and Toxoplasma should be excluded because of their neurotropism[

6].

Around 1-3% of patients with SLE and APS develop chorea. It is usually generalized, and psychosis and behavioral disturbances are quite featured, with a resolution course predominant [

3].

Drug toxicity should be considered in the diagnostic approach of choreic disorders. A careful medical history is required for potential intake of dopamine receptor blocking agents, antiparkinsonian or antiepileptic drugs. Several inborn metabolic diseases may also present with chorea, notably some specific organic acid disorders, such as glutaric acidemia type 1 and methylmalonic acidemia [

3]. When acute hemichorea is reported, it’s important to evaluate common complications of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Another peculiar etiology of unilateral chorea, in children less frequent though, is vascular stroke. Most cardioembolic strokes in pediatric patients occur in the setting of cardiac surgery, since survival after this procedure has increased [

8]. For this reason, in the last few years more attention has been paid to “Post Pump Chorea” (PPC), complication of pediatric open heart surgery (in particular when cardiopulmonary bypass is used) [

9]. Nowadays, it’s still not clear if pathogenesis is due to microemboli or to inadequate restore of cerebral circulation after operation. PPC occurs within 2 weeks after surgery [

10]. Signs and symptoms often improve or fade away in a few weeks or months [

11].

In this work we describe a case of chorea in a 6 years old child who underwent heart surgery for moderate-severe mitral insufficiency, with the aim to provide more awareness about differential diagnosis among the many causes of chorea in pediatric population, giving particular importance to risk factors and clinical presentation of patients who undergo our attention.

2. Case Report

A 6-year-old girl, born at term by C-Section, Small for Gestational Age (SGA), Birth Weight 2450 g, with a medical history of moderate-severe mitral insufficiency due to prolapse of the anterior mitral leaflet and severe hypoplasia of the posterior one, underwent cardiac surgery for valve repair in Extracorporeal Circulation (total ECC time 6 hours and cooling temperature of 32°C).

One week after the discharge from the surgery department, the patient was taken to the Emergency Room of “Regina Margherita” Pediatric Hospital of Turin for hyposthenia of the right upper limb and the right lower one associated with slower speech, mild dysarthria and sialorrhea.

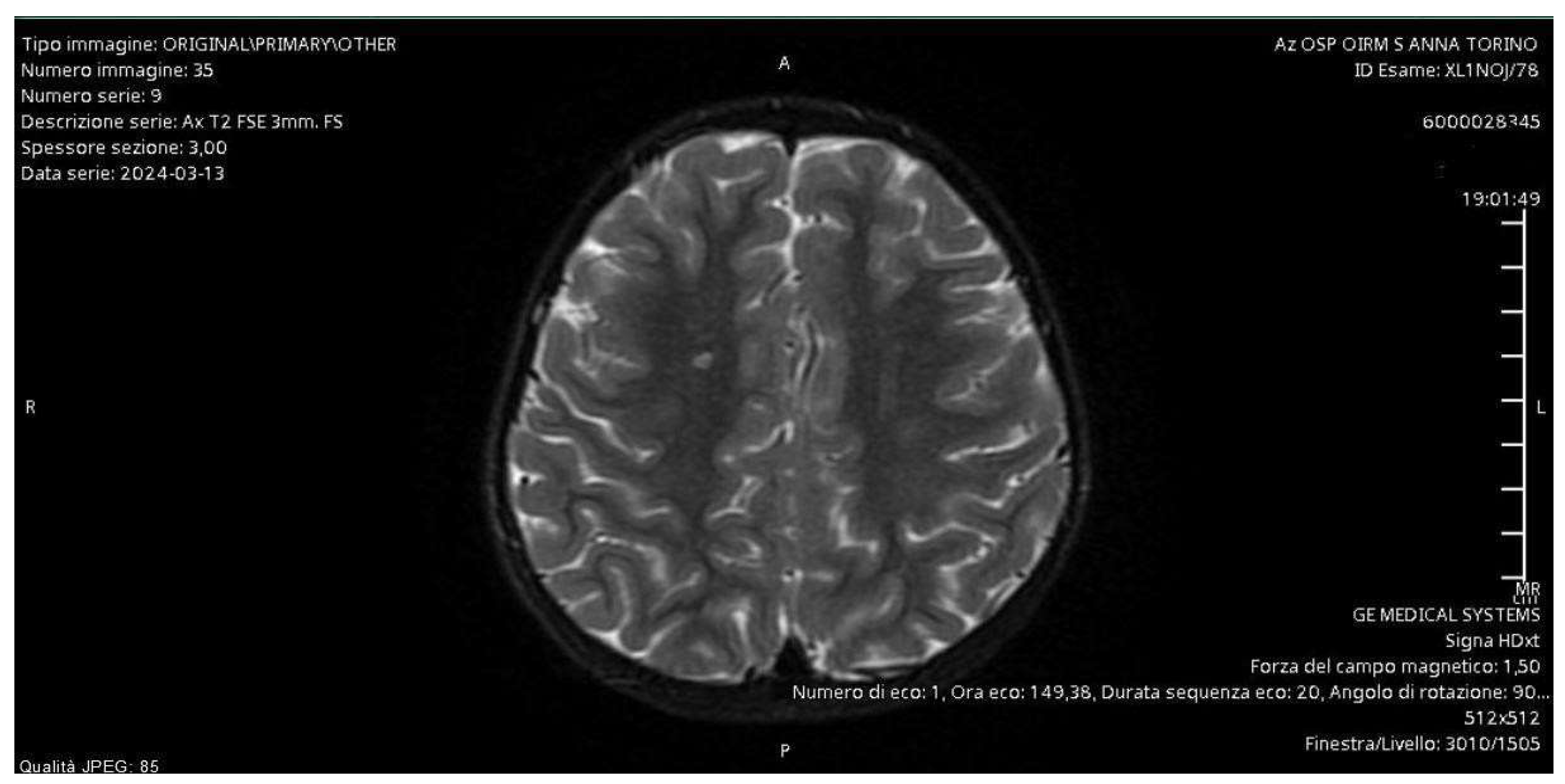

In regime of emergency, a MRI of the brain and an intracranial MRI-angiography were performed with the evidence of a small vascular focus on a probable microembolic basis at the right semioval center. They allowed us to exclude the presence of brain masses and stroke as causes of chorea, since the clinical manifestations were ipsilateral to the microembolic focus (

Figure 1).

An electroencephalogram (EEG) was performed too, with the finding of initial signs of bilateral parieto-occipital slow dysrhythmia, monitored with subsequent serial electroencephalograms and gradually normalized.

Neurological evaluation revealed repeated, involuntary, non-finalistic, distal movements, choreo-athetotic like, involving the right hand and foot and sporadically becoming wider until involving the ipsilateral arm and leg too. Light hyposthenia of the right upper and lower limb and right hand grasp deficit were reported too. There were no abnormalities in sensory function, deep tendon reflexes and cranial nerve function.

Further investigations performed allowed us to exclude the main causes of chorea in children. Above all, the hypothesis of rheumatic chorea was excluded due to negative tests related to a previous group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus infection.

Rachicentesis was not performed due to ongoing warfarin therapy but serum panels for dysimmune encephalitis and serum virological tests within normal limits allowed us to exclude autoimmune and infectious chorea too.

Moreover, medical history had not revealed the prescription of any pharmacological agents potentially interfering with movement and drug-induced chorea was finally ruled out by an extensive toxicological work-up in plasma and in urine, that did not show any abnormal finding.

In order to investigate for inherited metabolic conditions that may present with chorea, specific analysis were then performed, including the determination of amino acids, total homocysteine, ceruloplasmin, lactate and uric acid in plasma, the determination of acylcarnitines and biotinidase activity in dried blood spot and the determination of organic acids in urine. The results of this metabolic screening were found to be normal. Medical treatment with warfarin, prednisone and oral amoxicillin was administered, until the rheumatic etiology of chorea was excluded and antibiotic therapy therefore suspended. The patient was offered neuro-rehabilitation including physiotherapy and speech therapy assessment too.

In consideration of anamnestic data and the results of tests performed, a diagnostic hypothesis of post pump chorea was established.

As a result, there was a remarkable improvement of motor symptoms and radiological data, remotely controlled, with the expected evolution of the microembolic alteration, commonly found in patients undergoing extracorporeal circulation. The patient made good overall recovery in two weeks after which the treatment was gradually withdrawn and she was discharged without neurological consequences.

3. Discussion

The diagnostic pathway for our patient involved evaluating several hypotheses. The brain MRI and the intracranial MRI-angiography allowed us to exclude brain masses and ischemic foci responsible for the symptoms. The instrumental examination showed evidence of a microhemorrhagic focus located ipsilateral to the body side affected by the neurological disturbance.

Given the age of our patient (older than five years) and the symptoms at presentation, we focused on acquired chorea. From an epidemiological point of view, the first hypothesis we considered was Sydenham's chorea. In laboratory tests, our patient had the O-titer (ASLO titer) at the upper limit of the normal range, but negative anti-DNAse antibodies and throat swab for group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus infection. Although the patient presented mitral insufficiency, which appeared to be compatible with rheumatic fever, the valvular defect had been first diagnosed more than three years earlier. In addition, according to the cardiologists, the morphology of the valve not appear to be consistent with rheumatic fever. Finally, the child presented with unilateral neurological symptoms at onset, whereas Sydenham's chorea more commonly involves both sides.

Subsequently, in order to exclude an autoimmune etiology, the serum panel for dysimmune encephalitis was performed, including anti-NMDAr, anti-AMPAr, anti-GABAr B1, anti-LG1, anti-CASPR antibodies, all of which were negative. Furthermore, the serology panel for neurotropic viruses, to which Borrelia was added, was also normal.

Chorea can also characterize the clinical presentation in a limited percentage of children suffering from certain inborn metabolic diseases, including aminoacidopathies such as homocystinuria and maple syrup urine disease, organic acidemias such as glutaric acidemia type 1, biotinidase deficiency, methylmalonic acidemia and propionic acidemia, purine metabolism disorders such as Lesch-Nyhan disease, copper disorders such as Wilson disease, pyruvate metabolism disorders such as pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency. In order to investigate for these conditions, we have performed a specific biochemical work-up based on the analysis of amino acids, homocysteine, acylcarnitines, organic acids, biotinidase activity, uric acid, ceruloplasmin and lactate. This metabolic screening allows the identification of the majority of inborn metabolic disorders presenting with chorea [

12].

After performing all the diagnostic investigations and considering the patient's medical history and clinical course, the diagnosis of post-pump chorea was reached by exclusion (

Table 1). This condition is one of the most concerning postoperative neurological complications for pediatric patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Although postpump chorea was first described by Bjork and Hultquist in the 1960s, the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms remain largely unknown. The most widely accepted hypothesis suggests that neurological complications could be due to hypoxic-ischemic events or disturbances in cerebral blood flow following reperfusion after prolonged hypothermia in patients undergoing extracorporeal circulation [

13].

Early studies reported an incidence rate of up to 18% [

14], but, according to more recent literature, this has fallen to between 0.6% and 1.7% [

15].

Choreoathetotic movements typically occur within two weeks of the surgical procedure, as in the case of our patient whose mother noticed hyposthenia in her right arm about ten days after surgery [

10].

Our patient’s symptomatology initially involved the right hemilatum, with right hand hypotilisation and dragging of the right lower limb, associated with slowed speech. Gherpelli et al. in 1998 observed 647 children who had undergone cardiac surgery and described how choreic movements predominantly affected limbs bilaterally and orofacial musculature [

11].

Over the years, numerous risk factors associated with the development of neurological complications have been identified, including the duration and degree of hypothermia during the surgical procedure, the induction of intraoperative cardiac arrest with extracorporeal circulation, the patient’s age (with increased vulnerability under one year of age up to 5-6 years) and weight, and the presence of cyanotic heart disease [

9,

15,

16].

Our patient is a 6-year-old girl with poor ponderal-staturo growth, and a diagnosis of severe mitral insufficiency approximately one year prior. The surgical procedure was carried out in two stages, with a double induction of extracorporeal circulation under moderate hypothermia (32°C).

As for diagnostic investigations, instrumental examinations are often normal in with postpump chorea. Electroencephalographic findings are negative in most cases, although some patients exhibit a diffuse slowing of the electrical activity, as observed in our patient [

11,

13].

Additionally, children with onset of neurological complications after cardiac surgery have been evaluated using CT and diffusion and perfusion weighted MRI of the brain, with findings that can be highly variable. Often, during the acute phase, MRI may be normal or show a pattern of multiple microembolic infarcts, anomalies in the basal ganglia, or diffuse atrophy [

11,

17,

18]. Consistent with the literature, our patient was studied using contrast-enhanced MRI and intracranial MRI angiography, which revealed the presence of a vascular lesion in the right centrum semiovale and punctiform microhemorrhagic foci as a consequence of extracorporeal circulation.

The available treatment of postpump chorea is symptomatic; since the 1960s, multiple attempts have been made with Tetrabenazine, Valproate, Levetiracetam, and Carbamazepine without any benefit. Currently, the only therapy routinely used in clinical practice is neuroleptics, among them Haloperidol, without any evidence, however, that this could modify the evolution of the disease [

10].

Typically, the symptoms resolve within 2-4 weeks, although cases have been described with long-term neurological sequelae, ranging from memory, language, and motor function deficits to more severe clinical presentations such as long-term motor and cognitive disabilities [

10,

13]. A pediatric neuropsychiatric follow-up was established for our patient, including electroencephalographic investigations and the monitoring of academic learning, to analyze the long-term consequences.

4. Conclusions

This case highlights the significance of a thorough differential diagnosis in pediatric chorea, emphasizing the importance of considering even less common diagnoses based on a patient's medical history and clinical presentation. The diagnosis of post-pump chorea was established by exclusion, following a comprehensive evaluation of several diagnostic hypotheses.

Neurological complications following cardiac surgery remain a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in pediatric patients. The child of our case report presented several risk factors, despite the hypothermia not being severe. Further studies are needed, particularly regarding management and treatment of this complication, to promptly recognize the clinical presentation and address it adequately. Additionally, the use of advanced imaging techniques and neurophysiological monitoring may provide further insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying these complications.

Finally, multidisciplinary collaboration between surgeons, pediatric neuropsychiatrists, radiologists and pediatricians is essential for early recognition of choreic symptoms and identification of the underlying etiology. This approach may allow early treatment helping to minimize long-term complications.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patient involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Termsarasab, P. Chorea. Contin. Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 25, 1001–1035 (2019).

- Walker, R. H. Chorea: Contin. Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 19, 1242–1263 (2013).

- Baizabal-Carvallo, J. F. & Cardoso, F. Chorea in children: etiology, diagnostic approach and management. J. Neural Transm. 127, 1323–1342 (2020).

- Mohammad, S. S.; et al. Movement disorders in children with anti-NMDAR encephalitis and other autoimmune encephalopathies: AUTOIMMUNE MOVEMENT DISORDERS IN CHILDREN. Mov. Disord. 29, 1539–1542 (2014).

- Titulaer, M. J. , Leypoldt, F. & Dalmau, J. Antibodies to N-methyl-D-aspartate and other synaptic receptors in choreoathetosis and relapsing symptoms post–herpes virus encephalitis. Mov. Disord. 29, 3–6 (2014).

- Yilmaz, S. & Mink, J. W. Treatment of Chorea in Childhood. Pediatr. Neurol. 102, 10–19 (2020).

- Arecco, A. , Ottaviani, S., Boschetti, M., Renzetti, P. & Marinelli, L. Diabetic striatopathy: an updated overview of current knowledge and future perspectives. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 47, 1–15 (2023).

- Zijlmans, J. C. M. Vascular chorea in adults and children. in Handbook of Clinical Neurology vol. 100 261–270 (Elsevier, 2011).

- Abdshah, A.; et al. Incidence of neurological complications following pediatric heart surgery and its association with neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio. Health Sci. Rep. 6, e1077 (2023).

- Khan, A. , Hussain, N. & Gosalakkal, J. Post-pump chorea: Choreoathetosis after cardiac surgery with hypothermia and extracorporeal circulation. Journal of Pediatric Neurology (2012). [CrossRef]

- Gherpelli, J. L. D.; et al. Choreoathetosis after cardiac surgery with hypothermia and extracorporeal circulation. Pediatr. Neurol. 19, 113–118 (1998).

- Saudubray, J.-M. & García-Cazorla, Á. Clinical Approach to Inborn Errors of Metabolism in Paediatrics. In Inborn Metabolic Diseases (eds. Saudubray, J.-M., Baumgartner, M. R., García-Cazorla, Á. & Walter, J.) 3–123 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2022). [CrossRef]

- Przekop, A. , Mcclure, C. & Ashwal, S. Postoperative encephalopathy with choreoathetosis. in Handbook of Clinical Neurology vol. 100 295–305 (Elsevier, 2011).

- Brunberg, J. A. , Doty, D. B. & Reilly, E. L. Choreoathetosis in infants following cardiac surgery with deep hypothermia and circulatory arrest. J. Pediatr. 84, 232–235 (1974).

- Popkirov, S. , Schlegel, U. & Skodda, S. Is postoperative encephalopathy with choreoathetosis an acquired form of neuroacanthocytosis? Med. Hypotheses 89, 21–23 (2016).

- Holden, K. R. , Sessions, J. C., Curé, J., Whitcomb, D. S. & Sade, R. M. NNeurologic outcomes in children with post-pump choreoathetosis.

- Medlock, M. D.; et al. A 10-year experience with postpump chorea. Ann. Neurol. 34, 820–826 (1993).

- Kirkham, F. J.; et al. Movement disorder emergencies in childhood. Eur. J. Paediatr.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).