Submitted:

01 July 2024

Posted:

03 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

1. Chronological Progression of COPD

1.1. Disease Progression in COPD

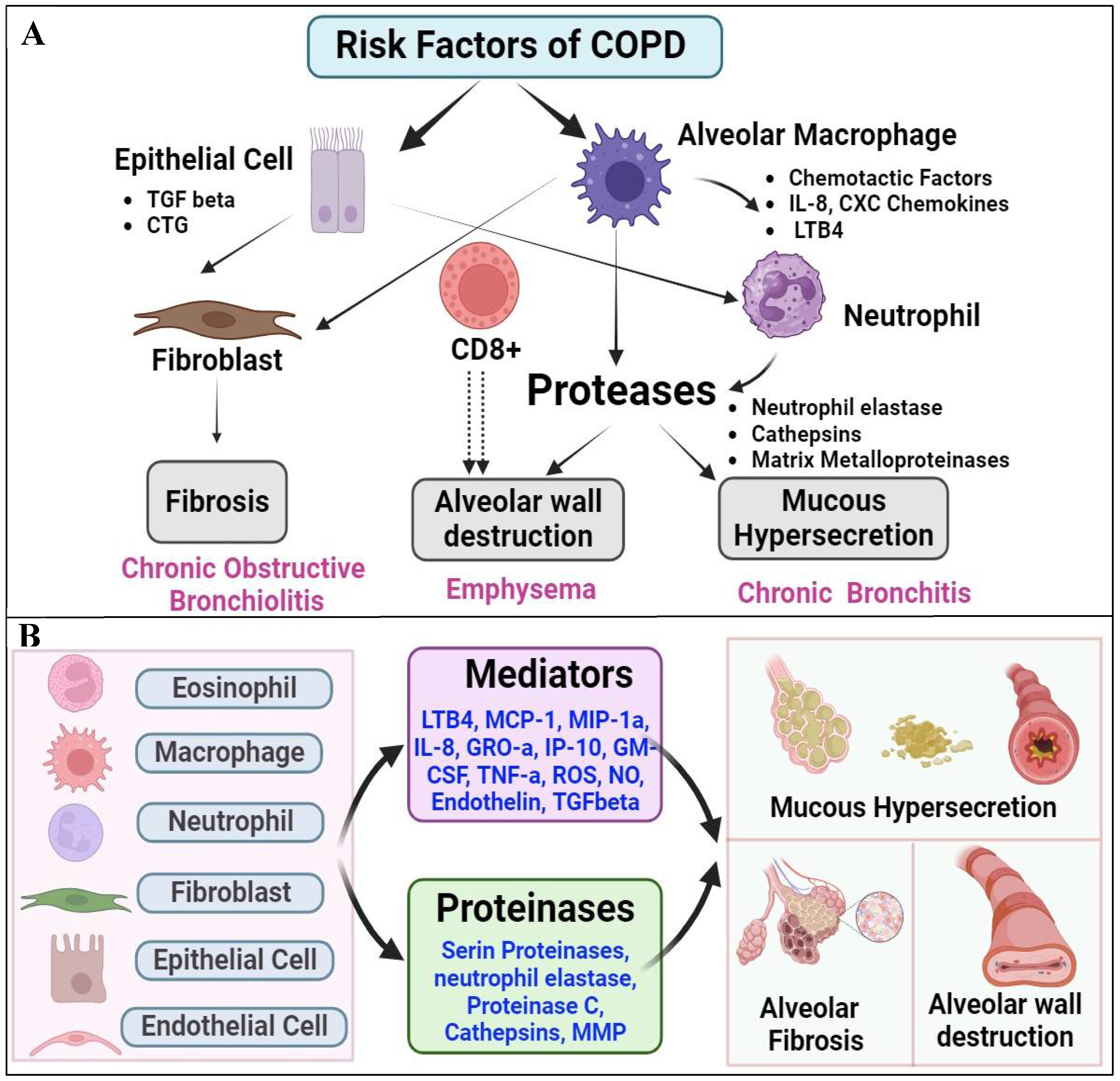

1.2. The Major Causative Factors of COPD

1.3. Diagnosis and Monitoring of COPD

2. Prognostic and Diagnostic Significance of LncRNA in COPD

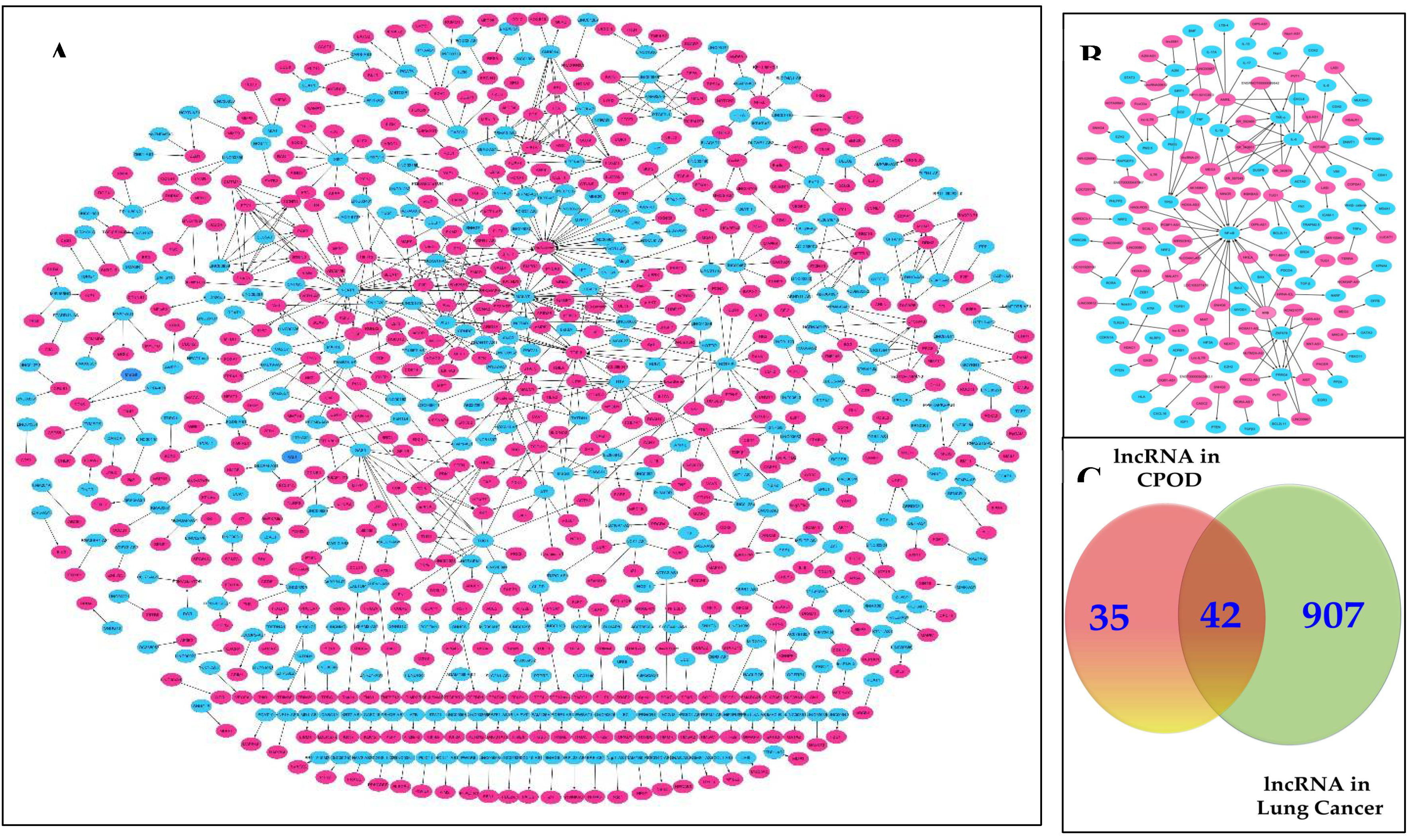

2.1. Identification and Profiling of COPD-Associated LncRNAs

2.2. Master Regulators of Gene Expression in Lung Cancers Progression

2.3. Tobacco Smoke Exposure and Expression Profiles of LncRNA in COPD

2.4. Correlation Between LncRNA Expression and COPD Severity

2.5. Prognostic and Diagnostic Value of LncRNA in Predicting COPD Outcomes

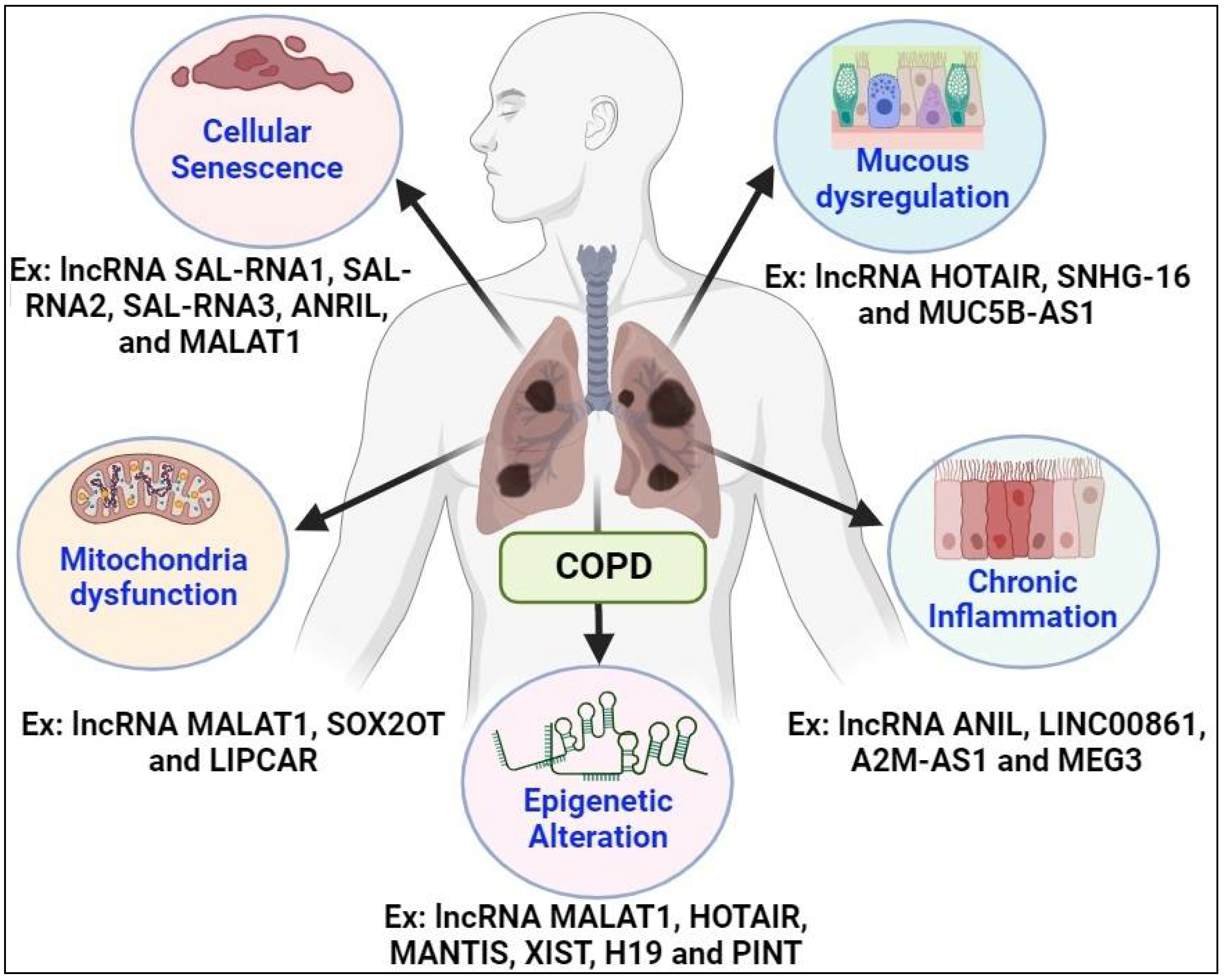

3. Regulatory Functions of LncRNAs in COPD

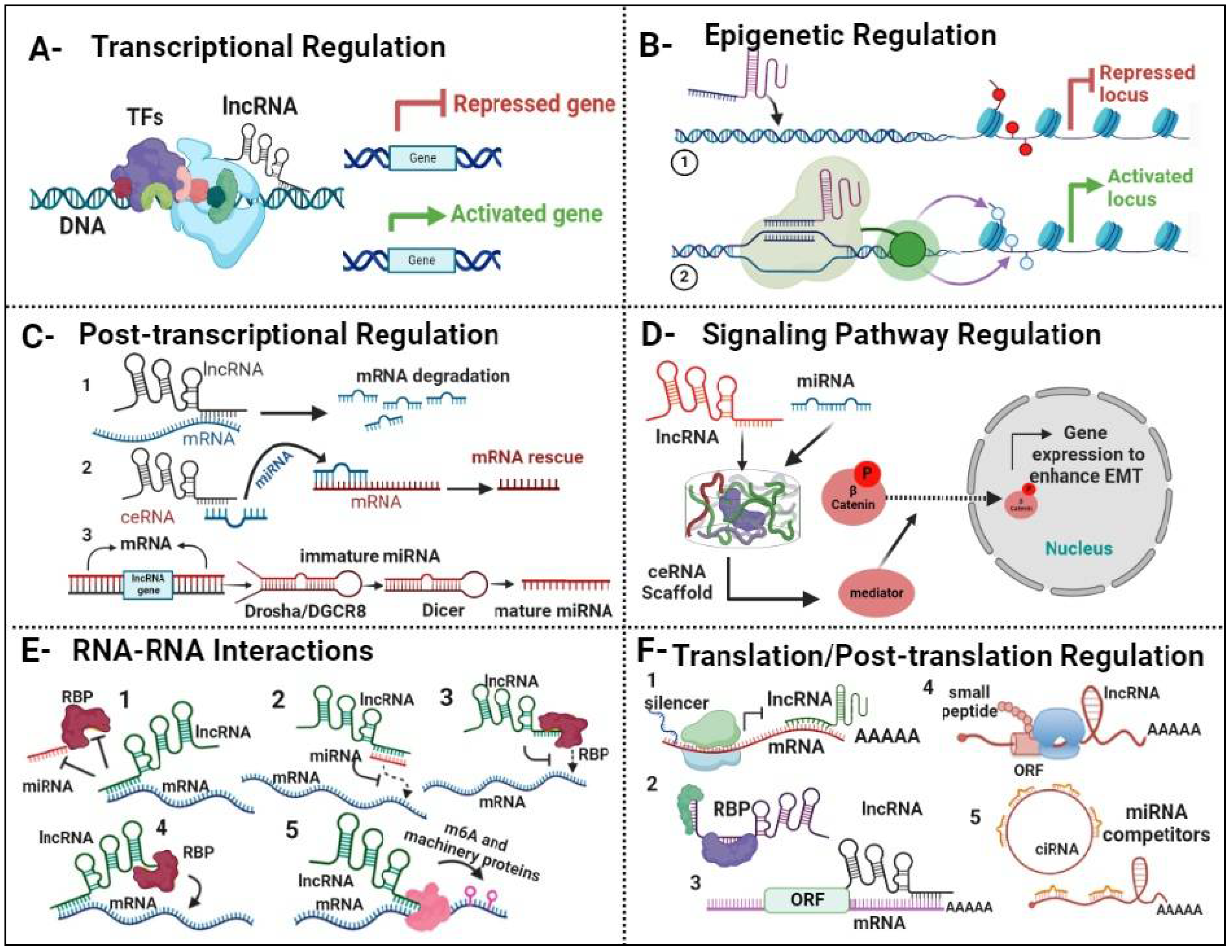

3.1. LncRNAs Control Gene Expression in COPD

3.2. LncRNA-Mediated Immune Response in COPD

3.3. Complexities of Inflammatory Mechanisms in COPD

3.4. Modulation of Cellular Processes by LncRNA in COPD

4. Modulatory Mechanisms of COPD-Associated LncRNA in Lung Cancer Progression

4.1. Interaction Between COPD-Associated LncRNA and Lung Cancer Pathways

4.1.1. Shared Molecular Pathways

4.1.2. Regulatory roles of COPD-Associated LncRNA in Lung Cancer

4.2. Dysregulated Expression of COPD-Associated LncRNAs in Lung Cancer

5. LncRNA in Body Fluids for COPD Diagnosis and Therapy

5.1. Detection of LncRNA Biomarkers in Blood Samples

5.2. Urinary LncRNA as a Diagnostic Tool for COPD

5.3. Pharmacological Actions of LncRNA Molecules as Potential Therapeutics for COPD

5.4. Potential Therapeutic Applications of LncRNA in COPD

Conclusions and Future Directions:

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Authors Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; 2021. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/gold-reports/ (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Soriano, J.B.; Kendrick, P.J.; Paulson, K.R.; et al. Prevalence and Attributable Health Burden of Chronic Respiratory Diseases, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir Med. 2020, 8, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurer, D.C.; Erdogan, İ.; Ahmadov, U.; Basol, M.; Sweef, O.; Cakan-Akdogan, G.; Akgül, B. Transcriptomics Profiling Identifies Cisplatin-Inducible Death Receptor 5 Antisense Long Non-coding RNA as a Modulator of Proliferation and Metastasis in HeLa Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021, 9, 688855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Quinn, J.J.; Chang, H.Y. Unique Features of Long Non-Coding RNA Biogenesis and Function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Ding, J.W.; Wang, X.A.; et al. Dysregulation of lncRNAs and mRNAs Expression in the Development of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 119, 4600–4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de-Torres, J.P.; Wilson, D.O.; Sanchez-Salcedo, P.; et al. Lung Cancer in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Development and Validation of the COPD Lung Cancer Screening Score. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 191, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durham, A.L.; Adcock, I.M. The Relationship between COPD and Lung Cancer. Lung Cancer 2015, 90, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdoğan, İ.; Sweef, O.; Akgül, B. Long Noncoding RNAs in Human Cancer and Apoptosis. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2023, 24, 872–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agusti, A.; Edwards, L.D.; Rennard, S.I.; et al. Persistent systemic inflammation is associated with poor clinical outcomes in COPD: a novel phenotype. PLoS One 2012, 7, e37483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, P.J. Inflammatory mechanisms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelmeier, C.F.; Criner, G.J.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report. GOLD Executive Summary. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedzicha, J.A.; Seemungal, T.A. COPD exacerbations: defining their cause and prevention. Lancet 2007, 370, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celli, B.R.; MacNee, W. ; ATS/ERS Task Force. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur. Respir. J. 2004, 23, 932–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; 2021. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/gold-reports/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Pellegrino, R.; Viegi, G.; Brusasco, V.; et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 26, 948–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celli, B.R.; Cote, C.G.; Marin, J.M.; et al. The Body-Mass Index, Airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise Capacity Index in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sin, D.D.; Miller, B.E.; Duvoix, A.; et al. Serum PARC/CCL-18 concentrations and health outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweef, O.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z. The Oncogenic and Tumor Suppressive Long Non-Coding RNA-microRNA-Messenger RNA Regulatory Axes Identified by Analyzing Multiple Platform Omics Data from Cr(VI)-Transformed Cells and Their Implications in Lung Cancer. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Scoditti, E.; Massaro, M.; Garbarino, S.; Toraldo, D.M. Role of Diet in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Prevention and Treatment. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byanova, K.L.; Abelman, R.; North, C.M.; Christenson, S.A.; Huang, L. COPD in People with HIV: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Management, and Prevention Strategies. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2023, 18, 2795–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleich, F.; Bougard, N.; Moermans, C.; Sabbe, M.; Louis, R. Cytokine-targeted therapies for asthma and COPD. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2023, 32, 220193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, M.; Chandel, J.; Malik, J.; Naura, A.S. Particulate matter in COPD pathogenesis: an overview. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 71, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, D.D.; Doiron, D.; Agusti, A.; Anzueto, A.; Barnes, P.J.; Celli, B.R.; Criner, G.J.; Halpin, D.; Han, M.K.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Air pollution and COPD: GOLD 2023 committee report. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2202469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neşe, A.; Samancıoğlu Bağlama, S. The Effect of Progressive Muscle Relaxation and Deep Breathing Exercises on Dyspnea and Fatigue Symptoms of COPD Patients: A Randomized Controlled Study. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2022, 36, E18–E26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntritsos, G.; Franek, J.; Belbasis, L.; Christou, M.A.; Markozannes, G.; Altman, P.; Fogel, R.; Sayre, T.; Ntzani, E.E.; Evangelou, E. Gender-specific estimates of COPD prevalence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2018, 13, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, L.N.; Martinez, F.J. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease subpopulations and phenotyping. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 1961–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, S.P.; Criner, G.J. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Evaluation and Management. Med. Clin. North Am. 2019, 103, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagdonas, E.; Raudoniute, J.; Bruzauskaite, I.; Aldonyte, R. Novel aspects of pathogenesis and regeneration mechanisms in COPD. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2015, 10, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.S.; Liu, Z.; Sweef, O.; Saeed, A.F.; Kluz, T.; Costa, M.; Shroyer, K.R.; Kondo, K.; Wang, Z.; Yang, C. Hexavalent chromium exposure activates the non-canonical nuclear factor kappa B pathway to promote immune checkpoint protein programmed death-ligand 1 expression and lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2024, 589, 216827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murgia, N.; Gambelunghe, A. Occupational COPD-The most under-recognized occupational lung disease? Respirology 2022, 27, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Chronic Respiratory Diseases Collaborators. Global burden of chronic respiratory diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: an update from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 59, 101936. [CrossRef]

- Rabe, K.F.; Watz, H. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2017, 389, 1931–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, S.; Jankowich, M.; Wu, W.C.; Blackshear, C.; Abbasi, S.; Choudhary, G. Gender Differences in Risk Factors Associated With Pulmonary Artery Systolic Pressure, Heart Failure, and Mortality in Blacks: Jackson Heart Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e013034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, I.A.; Jenkins, C.R.; Salvi, S.S. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in never-smokers: risk factors, pathogenesis, and implications for prevention and treatment. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannino, D.M.; Buist, A.S. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet 2007, 370, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvi, S.S.; Barnes, P.J. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers. Lancet 2009, 374, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easter, M.; Bollenbecker, S.; Barnes, J.W.; Krick, S. Targeting Aging Pathways in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Sun, S.; Tang, R.; Qiu, H.; Huang, Q.; Mason, T.G.; Tian, L. Major air pollutants and risk of COPD exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2016, 11, 3079–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.S.; Liu, Z.; Sweef, O.; Xie, J.; Chen, J.; Zhu, H.; Zeidler-Erdely, P.C.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z. Long noncoding RNA ABHD11-AS1 interacts with SART3 and regulates CD44 RNA alternative splicing to promote lung carcinogenesis. Environ Int. 2024, 185, 108494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekkat-Berkani, R.; Wilkinson, T.; Buchy, P.; Dos Santos, G.; Stefanidis, D.; Devaster, J.M. Seasonal influenza vaccination in patients with COPD: a systematic literature review. BMC Pulm. Med. 2017, 17, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odimba, U.; Senthilselvan, A.; Farrell, J.; Gao, Z. Current Knowledge of Asthma-COPD Overlap (ACO) Genetic Risk Factors, Characteristics, and Prognosis. COPD 2021, 18, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, E.K. Genetics of COPD. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2020, 82, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Mu, X.; Deng, L.; Fu, A.; Pu, E.; Tang, T.; Kong, X. The etiologic origins for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2019, 14, 1139–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahnert, K.; Jörres, R.A.; Behr, J.; Welte, T. The Diagnosis and Treatment of COPD and Its Comorbidities. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2023, 120, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şerifoğlu, İ.; Ulubay, G. The methods other than spirometry in the early diagnosis of COPD. Tuberk Toraks 2019, 67, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huprikar, N.A.; Skabelund, A.J.; Bedsole, V.G.; Sjulin, T.J.; Karandikar, A.V.; Aden, J.K.; Morris, M.J. Comparison of Forced and Slow Vital Capacity Maneuvers in Defining Airway Obstruction. Respir. Care 2019, 64, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, W.; He, X.; Xu, Q.F.; Wang, H.Y.; Casaburi, R. Increased difference between slow and forced vital capacity is associated with reduced exercise tolerance in COPD patients. BMC Pulm. Med. 2014, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christenson, S.A.; Smith, B.M.; Bafadhel, M.; Putcha, N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2022, 399, 2227–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Bemt, L.; Schermer, T.; Smeele, I.; Bischoff, E.; Jacobs, A.; Grol, R.; van Weel, C. Monitoring of patients with COPD: a review of current guidelines' recommendations. Respir. Med. 2008, 102, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarroux, J.; Morillon, A.; Pinskaya, M. History, Discovery, and Classification of lncRNAs. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 1008, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Fu, H.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, X. Function of lncRNAs and approaches to lncRNA-protein interactions. Sci. China Life Sci. 2013, 56, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, M.C.; Daulagala, A.C.; Kourtidis, A. LNCcation: lncRNA localization and function. J. Cell Biol. 2021, 220, e202009045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, D.; Li, D.; Zheng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Lu, W. Long non-coding RNA expression patterns in lung tissues of chronic cigarette smoke induced COPD mouse model. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negewo, N.A.; Gibson, P.G.; McDonald, V.M. COPD and its comorbidities: Impact, measurement and mechanisms. Respirology 2015, 20, 1160–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwagboe, I.; Adcock, I.M.; Lo Bello, F.; Caramori, G.; Mumby, S. New drugs under development for COPD. Minerva Med. 2022, 113, 471–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raherison, C.; Girodet, P.O. Epidemiology of COPD. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2009, 18, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, F.W.; Chan, K.P.; Hui, D.S.; Goddard, J.R.; Shaw, J.G.; Reid, D.W.; Yang, I.A. Acute exacerbation of COPD. Respirology 2016, 21, 1152–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, R. Long noncoding RNAs in respiratory diseases. Histol. Histopathol. 2018, 33, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulet, C.; Njock, M.S.; Moermans, C.; Louis, E.; Louis, R.; Malaise, M.; Guiot, J. Exosomal Long Non-Coding RNAs in Lung Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, D.K.; Biswas, R. Role of Non-Coding RNAs in Post-Transcriptional Regulation of Lung Diseases. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 767348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booton, R.; Lindsay, M.A. Emerging role of MicroRNAs and long noncoding RNAs in respiratory disease. Chest 2014, 146, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweef, O.; Zaabout, E.; Bakheet, A.; Halawa, M.; Gad, I.; Akela, M.; Tousson, E.; Abdelghany, A.; Furuta, S. Unraveling Therapeutic Opportunities and the Diagnostic Potential of microRNAs for Human Lung Cancer. Pharmaceutics. 2023, 15, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fang, D.; Ou, X.; Sun, K.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, P.; Zhao, Z.; He, Y.; Peng, J.; Xu, J. m6A modification-mediated lncRNA TP53TG1 inhibits gastric cancer progression by regulating CIP2A stability. Cancer Sci. 2022, 113, 4135–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, A.B.; Tsitsipatis, D.; Gorospe, M. Integrated lncRNA function upon genomic and epigenomic regulation. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 2252–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Sarkissyan, M.; Ogah, O.; Kim, J.; Vadgama, J.V. Expression of MALAT1 Promotes Trastuzumab Resistance in HER2 Overexpressing Breast Cancers. Cancers 2020, 12, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Piao, H.L.; Kim, B.J.; Yao, F.; Han, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Siverly, A.N.; Lawhon, S.E.; Ton, B.N.; et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 suppresses breast cancer metastasis. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1705–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.A.; Shah, N.; Wang, K.C.; Kim, J.; Horlings, H.M.; Wong, D.J.; Tsai, M.C.; Hung, T.; Argani, P.; Rinn, J.L.; Wang, Y.; Brzoska, P.; Kong, B.; Li, R.; West, R.B.; van de Vijver, M.J.; Sukumar, S.; Chang, H.Y. Long Non-Coding RNA HOTAIR Reprograms Chromatin State to Promote Cancer Metastasis. Nature 2010, 464, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, S.; Shen, Y.; Chen, B.; Wu, Y.; Jia, L.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, R.; Guo, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, Q. H3K27me3 Induces Multidrug Resistance in Small Cell Lung Cancer by Affecting HOXA1 DNA Methylation via Regulation of the lncRNA HOTAIR. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.A.; Shaker, O.G.; Khalifa, A.A.; Ezzat, E.M.; Elghobary, H.A.; Abdel Mawla, T.S.; Elkhateeb, A.F.; Elebiary, A.M.A.; Elamir, A.M. LncRNAs NEAT1, HOTAIR, and GAS5 Expression in Hypertensive and Non-Hypertensive Associated Cerebrovascular Stroke Patients, and Its Link to Clinical Characteristics and Severity Score of the Disease. Noncoding RNA Res. 2022, 8, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ren, X.; Yuan, Y.; Yuan, B.S. Downregulated lncRNA GAS5 and Upregulated miR-21 Lead to Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Lung Metastasis of Osteosarcomas. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 707693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Wei, H. LncRNA H19 alleviates sepsis-induced acute lung injury by regulating the miR-107/TGFBR3 axis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2022, 22, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Pan, T.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xie, H.; Liang, Z.; Chen, B.; Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Huang, X.; et al. Curcumenol triggered ferroptosis in lung cancer cells via lncRNA H19/miR-19b-3p/FTH1 axis. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 13, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Cruz, A.F.; Bermúdez-Santana, C.I. Computational Prediction of RNA-RNA Interactions between Small RNA Tracks from Betacoronavirus Nonstructural Protein 3 and Neurotrophin Genes during Infection of an Epithelial Lung Cancer Cell Line: Potential Role of Novel Small Regulatory RNA. Viruses 2023, 15, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yang, C.; Cui, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, L.; Fan, X.; Xu, S. The Long Non-Coding RNA XIST Controls Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Proliferation and Invasion by Modulating miR-186-5p. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 41, 2221–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Tang, Y.; Wang, T.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, M.; Tang, M.; et al. Chronic pulmonary bacterial infection facilitates breast cancer lung metastasis by recruiting tumor-promoting MHCIIhi neutrophils. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, G.W.; Cummings, K.M. Tobacco and lung cancer: risks, trends, and outcomes in patients with cancer. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2013, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Lin, H.; Su, Q.; Li, C. Cuproptosis-related lncRNA predict prognosis and immune response of lung adenocarcinoma. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 20, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desind, S.Z.; Iacona, J.R.; Yu, C.Y.; Mitrofanova, A.; Lutz, C.S. PACER lncRNA regulates COX-2 expression in lung cancer cells. Oncotarget 2022, 13, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Jiang, X.; Duan, L.; Xiong, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, P.; Jiang, L.; Shen, Q.; Zhao, S.; Yang, C.; et al. LncRNA PKMYT1AR promotes cancer stem cell maintenance in non-small cell lung cancer via activating Wnt signaling pathway. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.J.; Dang, H.X.; Lim, D.A.; Feng, F.Y.; Maher, C.A. Long noncoding RNAs in cancer metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Xu, A.; Li, M.; Xia, X.; Li, P.; Han, R.; Fei, G.; Zhou, S.; Wang, R. Effect of Methylation Status of lncRNA-MALAT1 and MicroRNA-146a on Pulmonary Function and Expression Level of COX2 in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 667624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, I.K.; Yao, H.; Rahman, I. Oxidative stress and chromatin remodeling in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and smoking-related diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 1956–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Wang, J.; Liu, X. Development of six immune-related lncRNA signature prognostic model for smoking-positive lung adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, R.; Gao, F.; Mao, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Yuan, L.; Huang, Z.; Lv, Q.; Qin, C.; Du, M.; Zhang, Z.; et al. LncRNA BCCE4 Genetically Enhances the PD-L1/PD-1 Interaction in Smoking-Related Bladder Cancer by Modulating miR-328-3p-USP18 Signaling. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2303473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maremanda, K.P.; Sundar, I.K.; Rahman, I. Role of inner mitochondrial protein OPA1 in mitochondrial dysfunction by tobacco smoking and in the pathogenesis of COPD. Redox Biol. 2021, 45, 102055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, P.; Wu, C.W.; Pham, A.; Zeki, A.A.; Royer, C.M.; Kodavanti, U.P.; Takeuchi, M.; Bayram, H.; Pinkerton, K.E. Animal models and mechanisms of tobacco smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 2023, 26, 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Ding, Y.; Shi, T.; He, W.; Feng, J.; Mei, Z.; Chen, X.; Feng, X.; Zhang, X.; Jie, Z. Long noncoding RNA GAS5 attenuates cigarette smoke-induced airway remodeling by regulating miR-217-5p/PTEN axis. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 2022, 54, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, P.; Li, R.; Piao, T.H.; Wang, C.L.; Wu, X.L.; Cai, H.Y. Pathological Mechanism and Targeted Drugs of COPD. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2022, 17, 1565–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, A.; Lee, J.Y.; Donaldson, A.V.; Natanek, S.A.; Vaidyanathan, S.; Man, W.D.; Hopkinson, N.S.; Sayer, A.A.; Patel, H.P.; Cooper, C.; et al. Increased expression of H19/miR-675 is associated with a low fat-free mass index in patients with COPD. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 7, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forder, A.; Zhuang, R.; Souza, V.G.P.; Brockley, L.J.; Pewarchuk, M.E.; Telkar, N.; Stewart, G.L.; Benard, K.; Marshall, E.A.; Reis, P.P.; et al. Mechanisms Contributing to the Comorbidity of COPD and Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, J.; Geng, S.; Jiang, H. Long noncoding RNAs antisense noncoding RNA in the INK4 locus (ANRIL) correlates with lower acute exacerbation risk, decreased inflammatory cytokines, and mild GOLD stage in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2019, 33, e22678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araya, J.; Tsubouchi, K.; Sato, N.; Ito, S.; Minagawa, S.; Hara, H.; Hosaka, Y.; Ichikawa, A.; Saito, N.; Kadota, T.; et al. PRKN-regulated mitophagy and cellular senescence during COPD pathogenesis. Autophagy 2019, 15, 510–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulet, C.; Njock, M.S.; Moermans, C.; Louis, E.; Louis, R.; Malaise, M.; Guiot, J. Exosomal Long Non-Coding RNAs in Lung Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.J.; Huang, H.B.; Shen, H.B.; Chen, W.; Yang, Z.H. Role of long non-coding RNA MALAT1 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 2691–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Sen, C.; Peters, K.; Frizzell, R.A.; Biswas, R. Comparative analyses of long non-coding RNA profiles in vivo in cystic fibrosis lung airway and parenchyma tissues. Respir. Res. 2019, 20, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.; Tang, F. The potency of lncRNA MALAT1/miR-155/CTLA4 axis in altering Th1/Th2 balance of asthma. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20190397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.P.; Liu, Z.B.; Wu, M.; Ge, Y.P.; Zhang, Q. Effect of lncRNA MALAT1 expression on survival status of elderly patients with severe pneumonia. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 3959–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Philp, A.M.; Corte, T.; Travis, M.A.; Schilter, H.; Hansbro, N.G.; Burns, C.J.; Eapen, M.S.; Sohal, S.S.; Burgess, J.K.; et al. Therapeutic targets in lung tissue remodelling and fibrosis. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 225, 107839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stefano, A.; Sangiorgi, C.; Gnemmi, I.; Casolari, P.; Brun, P.; Ricciardolo, F.L.M.; Contoli, M.; Papi, A.; Maniscalco, P.; Ruggeri, P.; et al. TGF-β Signaling Pathways in Different Compartments of the Lower Airways of Patients With Stable COPD. Chest 2018, 153, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stefano, A.; Sangiorgi, C.; Gnemmi, I.; Casolari, P.; Brun, P.; Ricciardolo, F.L.M.; Contoli, M.; Papi, A.; Maniscalco, P.; Ruggeri, P.; Girbino, G.; Cappello, F.; Pavlides, S.; Guo, Y.; Chung, K.F.; Barnes, P.J.; Adcock, I.M.; Balbi, B.; Caramori, G. TGF-β Signaling Pathways in Different Compartments of the Lower Airways of Patients with Stable COPD. Chest 2018, 153, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tang, J.; Wang, R. Long non-coding RNA FAM230B is a novel prognostic and diagnostic biomarker for lung adenocarcinoma. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 7919–7925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Huang, Q.; He, F. Correlation of small nucleolar RNA host gene 16 with acute respiratory distress syndrome occurrence and prognosis in sepsis patients. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, R.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Ding, Y. lncRNA GAS5 promotes pyroptosis in COPD by functioning as a ceRNA to regulate the miR 223 3p/NLRP3 axis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2022, 26, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Zhang, C.F.; Guo, J.L.; Su, J.L.; Guo, Z.K.; Li, H.Y. Involvement of NEAT1/PINK1-mediated mitophagy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease induced by cigarette smoke or PM2. 5. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jen, J.; Tang, Y.A.; Lu, Y.H.; Lin, C.C.; Lai, W.W.; Wang, Y.C. Oct4 transcriptionally regulates the expression of long non-coding RNAs NEAT1 and MALAT1 to promote lung cancer progression. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Kelava, L.; Zhang, L.; Kiss, I. Microarray data analysis to identify miRNA biomarkers and construct the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA network in lung adenocarcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101, e30393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokgun, O.; Tokgun, P.E.; Inci, K.; Akca, H. lncRNAs as Potential Targets in Small Cell Lung Cancer: MYC-dependent Regulation. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 2074–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.F.; Deng, J.M. Emerging Role of Long Noncoding RNAs in Asthma. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2023, 26, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Zhou, H.; Cao, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Senescence associated long non-coding RNA 1 regulates cigarette smoke-induced senescence of type II alveolar epithelial cells through sirtuin-1 signaling. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 300060520986049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezegbunam, W.; Foronjy, R. Posttranscriptional control of airway inflammation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Min, L.; Qiu, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, C.; Ma, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, L. Biological Function of Long Non-coding RNA (lncRNA) Xist. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 645647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Wang, H.; Hu, X.; Cao, X. lncRNA MALAT1 binds chromatin remodeling subunit BRG1 to epigenetically promote inflammation-related hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Oncoimmunology 2018, 8, e1518628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Qu, T.; Yin, D.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, E.; Guo, R. LncRNA LINC00969 promotes acquired gefitinib resistance by epigenetically suppressing of NLRP3 at transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels to inhibit pyroptosis in lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, C.; Sun, S.G.; Yue, Z.Q.; Bai, F. Role of lncRNA LUCAT1 in cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 134, 111158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Chen, L.; Piao, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Lin, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X. M6A RNA methylation-mediated RMRP stability renders proliferation and progression of non-small cell lung cancer through regulating TGFBR1/SMAD2/SMAD3 pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, S.Q.; Zhu, J.B.; Wang, L.N.; Lin, H.; Li, L.F.; Cheng, Y.D.; Duan, C.J.; Zhang, C.F. LncRNA CALML3-AS1 modulated by m6A modification induces BTNL9 methylation to drive non-small-cell lung cancer progression. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023, 30, 1649–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreiro, E.; Sznajder, J.I. Epigenetic regulation of muscle phenotype and adaptation: a potential role in COPD muscle dysfunction. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2013, 114, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Huang, K.; Chang, C.; Chu, X.; Zhang, K.; Li, B.; Yang, T. Serum Proteomic Profiling in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2023, 18, 1623–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvato, I.; Ricciardi, L.; Nucera, F.; Nigro, A.; Dal Col, J.; Monaco, F.; Caramori, G.; Stellato, C. RNA-Binding Proteins as a Molecular Link between COPD and Lung Cancer. COPD 2023, 20, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, L.; Xia, H.; Zheng, W.; Hua, L. Comparison of cell subsets in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and controls based on single-cell transcriptome sequencing. Technol. Health Care 2023, 31, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, H.; Ma, W.; Wang, F.; Liu, C.; He, S. Increased interleukin (IL)-8 and decreased IL-17 production in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) provoked by cigarette smoke. Cytokine 2011, 56, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, X.; Du, W.; Du, J.; Chi, Y.; Sun, B.; Song, Z.; Shi, J. Diagnosis values of IL-6 and IL-8 levels in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Investig. Med. 2021, 69, 1344–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matera, M.G.; Calzetta, L.; Cazzola, M. TNF-alpha inhibitors in asthma and COPD: we must not throw the baby out with the bath water. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 23, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belvisi, M.G.; Bottomley, K.M. The role of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in the pathophysiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a therapeutic role for inhibitors of MMPs? Inflamm. Res. 2003, 52, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wu, T.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Li, X.; Sun, T.; Xie, X.; Zhou, Y.; Du, Z. Tumor-suppressive function of long noncoding RNA MALAT1 in glioma cells by downregulation of MMP2 and inactivation of ERK/MAPK signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Li, H.; Qiu, T.; Dai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Cai, H. Loss of PTEN induces lung fibrosis via alveolar epithelial cell senescence depending on NF-κB activation. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e12858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzy, R. Fibroblast Growth Factor Inhibitors in Lung Fibrosis: Friends or Foes? Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 63, 273–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, R.Y.; Oliver, B. Innate Immune Reprogramming in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: New Mechanisms for Old Questions. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2023, 68, 470–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.G.; Pyo, S.J.; Cui, Y.; Yoon, S.H.; Nam, J.W. Tumor immune microenvironment lncRNAs. Brief Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbab504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Nie, Y.J.; Luo, G.H.; Fan, X.; Yang, S.; Zhao, Q.H.; Li, J.Q. lncRNA NEAT1 aggravates sepsis-induced lung injury by regulating the miR-27a/PTEN axis. Lab Invest. 2021, 101, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayama, T.; Marr, A.K.; Kino, T. Differential Expression of Glucocorticoid Receptor Noncoding RNA Repressor Gas5 in Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases. Horm. Metab. Res. 2016, 48, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayama, T.; Marr, A.K.; Kino, T. Differential Expression of Glucocorticoid Receptor Noncoding RNA Repressor Gas5 in Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases. Horm. Metab. Res. 2016, 48, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Huang, S.; Huang, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhuang, Q. Role and Mechanism of Exosome-Derived Long Noncoding RNA HOTAIR in Lung Cancer. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 17217–17227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Xu, M.; Han, L.; Wu, W.; Wang, S. Solamargine enhanced gefitinib antitumor effect via regulating MALAT1/miR-141-3p/Sp1/IGFBP1 signaling pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Carcinogenesis 2023, 44, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Xu, M.; Han, L.; Wu, W.; Wang, S. Solamargine enhanced gefitinib antitumor effect via regulating MALAT1/miR-141-3p/Sp1/IGFBP1 signaling pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Carcinogenesis 2023, 44, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Lan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zuo, F.; Gong, Y.; Luo, G.; Peng, Y.; Yuan, Z. LncRNA GAS5 suppresses inflammatory responses by inhibiting HMGB1 release via miR-155-5p/SIRT1 axis in sepsis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 942, 175520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, S. LncRNA GAS5 suppresses inflammatory responses and apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells by targeting miR-429/DUSP1. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2020, 113, 104357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Ding, X.; Chen, X. Chinese herbal compound Huangqin Qingrechubi capsule reduces lipid metabolism disorder and inflammatory response in gouty arthritis via the LncRNA H19/APN/PI3K/AKT cascade. Pharm. Biol. 2023, 61, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Xie, Y.; He, Q.; Geng, Y.; Xu, J. LncRNA-Cox2 regulates macrophage polarization and inflammatory response through the CREB-C/EBPβ signaling pathway in septic mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 101, 108347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, L.; Jin, Y.; Shen, X.; Li, Y. Construction of a prognostic immune-related lncRNA model and identification of the immune microenvironment in middle- or advanced-stage lung squamous carcinoma patients. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, R.; Xie, L.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, M.; He, P. Cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation in COPD mediated via LTB4/BLT1/SOCS1 pathway. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2015, 11, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barta, I.; Paska, C.; Antus, B. Sputum Cytokine Profiling in COPD: Comparison Between Stable Disease and Exacerbation. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2022, 17, 1897–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gu, H.; Gu, Y.; Zeng, X. Association between TNF-α -308 G/A polymorphism and COPD susceptibility: a meta-analysis update. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2016, 11, 1367–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, A.; Horie, M.; Nagase, T. TGF-β Signaling in Lung Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopoulou, M.E.; Papakonstantinou, E.; Stolz, D. Matrix Metalloproteinases in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.W.; Cai, Q.Q.; Yang, Y.; Dong, S.; Liu, Y.Y.; Chen, Z.Y.; Kang, C.L.; Qi, B.; Dong, Y.W.; Wu, W.; Zhuang, L.P.; Shen, Y.H.; Meng, Z.Q.; Wu, X.Z. LncRNA BC promotes lung adenocarcinoma progression by modulating IMPAD1 alternative splicing. Clin. Transl. Med. 2023, 13, e1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.W.; Jose, C.C.; Cuddapah, S. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: Insights into nickel-induced lung diseases. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 76, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Ji, X.; Cao, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, X.M.; Miao, M. Medicine Targeting Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition to Treat Airway Remodeling and Pulmonary Fibrosis Progression. Can. Respir. J. 2023, 2023, 3291957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, G.; Liao, Q.; Li, G.; Yin, F. miR-378 associated with proliferation, migration and apoptosis properties in A549 cells and targeted NPNT in COPD. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demedts, I.K.; Demoor, T.; Bracke, K.R.; Joos, G.F.; Brusselle, G.G. Role of apoptosis in the pathogenesis of COPD and pulmonary emphysema. Respir. Res. 2006, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, H.C.; Lin, T.L.; Chen, T.W.; Kuo, Y.L.; Chang, C.J.; Wu, T.R.; Shu, C.C.; Tsai, Y.H.; Swift, S.; Lu, C.C. Gut microbiota modulates COPD pathogenesis: role of anti-inflammatory Parabacteroides goldsteinii lipopolysaccharide. Gut 2022, 71, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.M.; Liu, G.Q.; Xian, H.B.; Si, J.L.; Qi, S.X.; Yu, Y.P. LncRNA NEAT1 alleviates sepsis-induced myocardial injury by regulating the TLR2/NF-κB signaling pathway. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 4898–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegman, C.H.; Li, F.; Ryffel, B.; Togbe, D.; Chung, K.F. Oxidative Stress in Ozone-Induced Chronic Lung Inflammation and Emphysema: A Facet of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Hua, S.; Song, L. PM2.5 Exposure and Asthma Development: The Key Role of Oxidative Stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 3618806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, L.M.; Herrera, A.M. Fibrotic response of tissue remodeling in COPD. Lung 2011, 189, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wu, D.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Qiu, F.; Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Cao, Y.; Yang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, J. A functional CNVR_3425. 1 damping lincRNA FENDRR increases lifetime risk of lung cancer and COPD in Chinese. Carcinogenesis 2018, 39, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kume, H.; Yamada, R.; Sato, Y.; Togawa, R. Airway Smooth Muscle Regulated by Oxidative Stress in COPD. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, M.; Zhang, D.; Jin, Y. Long Non-Coding RNA Review and Implications in Lung Diseases. JSM Bioinform. Genom. Proteom. 2018, 3, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.H.; Hao, Q.Y.; Wang, K.; Paul, J.; Wang, Y.X. Emerging Role of MicroRNAs and Long Noncoding RNAs in Healthy and Diseased Lung. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 967, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Groot, P.; Munden, R.F. Lung cancer epidemiology, risk factors, and prevention. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 2012, 50, 863–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginn, L.; Shi, L.; Montagna, M.; Garofalo, M. LncRNAs in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Noncoding RNA 2020, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Fukunaga, A.; Yodoi, J.; Tian, H. Progress in the mechanism and targeted drug therapy for COPD. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Feng, C.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Cai, R. LncRNA H19 promotes lung cancer proliferation and metastasis by inhibiting miR-200a function. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 460, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, J.; Kim, B.; Im, M.; Jang, W.; Chae, Y.; Kang, J.; Youn, B.; Kim, W. MALAT1-regulated gene expression profiling in lung cancer cell lines. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, M.; Chen, F. LncRNA MALAT1 accelerates non-small cell lung cancer progression via regulating miR-185-5p/MDM4 axis. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 9138–9149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Mo, J.; Xie, Y.; Wang, C. Ultrasound microbubbles-mediated miR-216b affects MALAT1-miRNA axis in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Tissue Cell 2022, 74, 101703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attaway, A.H.; Bellar, A.; Welch, N.; Sekar, J.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, S.; Hatipoğlu, U.; McDonald, M.L.; Regan, E.A.; Smith, J.D.; et al. Gene polymorphisms associated with heterogeneity and senescence characteristics of sarcopenia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.; Zhang, F.; Liu, L.; Shen, H.; Liu, T.; Jin, J.; Yu, N.; Wan, Z.; Wang, H.; Hu, X.; et al. LncRNA ANRIL promotes HR repair through regulating PARP1 expression by sponging miR-7-5p in lung cancer. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Niu, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, C.; Cao, H.; Chen, H.; Xie, R.; Zhuang, L. LncRNA TUG1 contributes to the tumorigenesis of lung adenocarcinoma by regulating miR-138-5p-HIF1A axis. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2021, 35, 20587384211048265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, F.; Lv, Z.D.; Huang, W.D.; Wei, S.C.; Liu, X.M.; Song, W.D. LncRNA TUG1 promotes pulmonary fibrosis progression via up-regulating CDC27 and activating PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Epigenetics 2023, 18, 2195305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entezari, M.; Ghanbarirad, M.; Taheriazam, A.; Sadrkhanloo, M.; Zabolian, A.; Goharrizi, M.A.S.B.; Hushmandi, K.; Aref, A.R.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Zarrabi, A.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs and exosomal lncRNAs: Potential functions in lung cancer progression, drug resistance and tumor microenvironment remodeling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 150, 112963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Hashimoto, R.F. Dynamical Analysis of a Boolean Network Model of the Oncogene Role of lncRNA ANRIL and lncRNA UFC1 in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, L. Retraction: Long noncoding RNA ANRIL knockdown increases sensitivity of non-small cell lung cancer to cisplatin by regulating the miR-656-3p/SOX4 axis. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.H.; Kim, D.; Jin, E.J. Down-regulation of Phospholipase D Stimulates Death of Lung Cancer Cells Involving Up-regulation of the Long ncRNA ANRIL. Anticancer Res. 2015, 35, 2795–2803. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25964559/. [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Jia, M.; Ji, J.; Wu, Z.; Chen, X.; Yu, D.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, Y. Roles of H19/miR-29a-3p/COL1A1 axis in COE-induced lung cancer. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.T.; Xing, W.; Zhao, R.S.; Tan, Y.; Wu, X.F.; Ao, L.Q.; Li, Z.; Yao, M.W.; Yuan, M.; Guo, W.; et al. HDAC2 inhibits EMT-mediated cancer metastasis by downregulating the long noncoding RNA H19 in colorectal cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, M. High expression of long non-coding RNA MALAT1 correlates with raised acute respiratory distress syndrome risk, disease severity, and increased mortality in sepstic patients. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2019, 12, 1877–1887. Available online: https://wwwncbinlmnihgov/pmc/articles/PMC6947113/. [PubMed]

- Bhat, A.A.; Afzal, O.; Afzal, M.; Gupta, G.; Thapa, R.; Ali, H.; Hassan Almalki, W.; Kazmi, I.; Alzarea, S.I.; Saleem, S.; et al. MALAT1: A key regulator in lung cancer pathogenesis and therapeutic targeting. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2024, 253, 154991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, N.; Xu, X.; He, Y. LncRNA TUG1 alleviates sepsis-induced acute lung injury by targeting miR-34b-5p/GAB1. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020, 20, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Shen, J.; Chan, M.T.; Wu, W.K. TUG1: A Pivotal Oncogenic Long Non-Coding RNA of Human Cancers. Cell Prolif. 2016, 49, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, G.; Jayawickramarajah, J.; Zhuo, Y.; Shan, B. Functions of lncRNA HOTAIR in lung cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2014, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.M.; Xu, S.; Wei, Y.B.; Yang, J.J.; Yang, Y.N.; Sun, S.S.; Li, Y.J.; Wang, P.Y.; Xie, S.Y. Roles of HOTAIR in lung cancer susceptibility and prognosis. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2020, 8, e1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Li, Q. LncRNA-UCA1 regulates lung adenocarcinoma progression through competitive binding to miR-383. Cell Cycle 2023, 22, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Ling, L.; Li, C.; Wu, R.; Zhang, M.; Shao, F.; Wang, Y. LncRNA UCA1 promoted cisplatin resistance in lung adenocarcinoma with HO1 targets NRF2/HO1 pathway. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 1295–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szafranski, P.; Gambin, T.; Karolak, J.A.; Popek, E.; Stankiewicz, P. Lung-specific distant enhancer cis regulates expression of FOXF1 and lncRNA FENDRR. Hum. Mutat. 2021, 42, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Merchan, A.; Cuadros, M.; Rodriguez, M.I.; Rodriguez, S.; Torres, R.; Estecio, M.; Coira, I.F.; Loidi, C.; Saiz, M.; Carmona-Saez, P.; Medina, P.P. The value of lncRNA FENDRR and FOXF1 as a prognostic factor for survival of lung adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 11, 1172–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Shirvani-Farsani, Z.; Hussen, B.M.; Taheri, M.; Samsami, M. The key roles of non-coding RNAs in the pathophysiology of hypertension. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 931, 175220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Y. Extracellular vesicles and COPD: foe or friend? J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanale, D.; Taverna, S.; Russo, A.; Bazan, V. Circular RNA in Exosomes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1087, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarfi, M.; Abbastabar, M.; Khalili, E. Long noncoding RNAs biomarker-based cancer assessment. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 16971–16986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reggiardo, R.E.; Maroli, S.V.; Kim, D.H. LncRNA Biomarkers of Inflammation and Cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2022, 1363, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Yu, W.; Yang, J. Long Non-Coding RNA in the Pathogenesis of Cancers. Cells 2019, 8, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.B.; Li, Z.H.; Gao, S. Circulating miR-146a/b Correlates with Inflammatory Cytokines in COPD and Could Predict the Risk of Acute Exacerbation COPD. Medicine 2018, 97, e9820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoult, G.; Gillespie, D.; Wilkinson, T.M.A.; Thomas, M.; Francis, N.A. Biomarkers to Guide the Use of Antibiotics for Acute Exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2022, 22, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walcher, L.; Kistenmacher, A.K.; Suo, H.; Kitte, R.; Dluczek, S.; Strauß, A.; Blaudszun, A.R.; Yevsa, T.; Fricke, S.; Kossatz-Boehlert, U. Cancer Stem Cells-Origins and Biomarkers: Perspectives for Targeted Personalized Therapies. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogelmeier, C.F.; Román-Rodríguez, M.; Singh, D.; Han, M.K.; Rodríguez-Roisin, R.; Ferguson, G.T. Goals of COPD Treatment: Focus on Symptoms and Exacerbations. Respir. Med. 2020, 166, 105938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, P.J. Inflammatory Endotypes in COPD. Allergy 2019, 74, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Liang, H.; Cui, R.; Ji, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Shen, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Song, Z.; Jiang, Y. Construction of a Risk Model and Prediction of Prognosis and Immunotherapy Based on Cuproptosis-Related LncRNAs in the Urinary System Pan-Cancer. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brisotto, G.; Guerrieri, R.; Colizzi, F.; Steffan, A.; Montico, B.; Fratta, E. Long Noncoding RNAs as Innovative Urinary Diagnostic Biomarkers. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2292, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terracciano, D.; Ferro, M.; Terreri, S.; Lucarelli, G.; D'Elia, C.; Musi, G.; de Cobelli, O.; Mirone, V.; Cimmino, A. Urinary Long Noncoding RNAs in Nonmuscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: New Architects in Cancer Prognostic Biomarkers. Transl. Res. 2017, 184, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, X.; Yu, B.; Ai, F. Long Non-Coding RNA THRIL Predicts Increased Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Risk and Positively Correlates with Disease Severity, Inflammation, and Mortality in Sepsis Patients. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2019, 33, e22882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Xie, D.; Pan, L.; Lou, Y.; Shi, M. Urinary Exosomal Long Noncoding RNAs Serve as Biomarkers for Early Detection of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Biosci. Rep. 2021, 41, BSR20210908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, J.; Gao, W.; Xuan, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, D.; Tian, Z.; Ni, B.; Tang, J. Critical Effects of Long Non-Coding RNA on Fibrosis Diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, e428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Feng, Y.; Zheng, X.; Xu, X. The Diagnostic and Therapeutic Role of snoRNA and LincRNA in Bladder Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, S.Q.; Wang, L.; Lin, H.; Zhu, J.B.; Chen, R.; Li, L.F.; Cheng, Y.D.; Duan, C.J.; Zhang, C.F. m6A Methyltransferase METTL3-Induced LncRNA SNHG17 Promotes Lung Adenocarcinoma Gefitinib Resistance by Epigenetically Repressing LATS2 Expression. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Wan, Z.; Zhou, L.; Liao, H.; Wan, R. LncRNA ITGB2-AS1 Promotes Cisplatin Resistance of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer by Inhibiting Ferroptosis via Activating the FOSL2/NAMPT Axis. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2023, 24, 2223377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Hu, T.; Tao, W.; Tong, J.; Han, Z.; Herndler-Brandstetter, D.; Wei, Z.; Liu, R.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Q.; Xu, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, R.; Cho, J.H.; Li, H.B.; Huang, H.; Flavell, R.A.; Zhu, S. A LncRNA from an Inflammatory Bowel Disease Risk Locus Maintains Intestinal Host-Commensal Homeostasis. Cell Res. 2023, 33, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.N.; Li, J.; Tang, L.B.; Chen, W.T.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, L.X. MiRNAs and LncRNAs: Dual Roles in TGF-β Signaling-Regulated Metastasis in Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.; Wang, B.; Tan, F.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, F.; Liu, M.; Zhou, G.; Yuan, C. The Regulatory Role of LncRNA HCG18 in Various Cancers. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 2023, 101, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansel, N.N.; McCormack, M.C.; Kim, V. The Effects of Air Pollution and Temperature on COPD. COPD 2016, 13, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Egranov, S.D.; Lin, C.; Yang, L. Long Noncoding RNA Loss in Immune Suppression in Cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 213, 107591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ding, P.; Yan, W.; Wang, Z.; Lan, Y.; Yan, X.; Li, T.; Han, J. Pharmacological Roles of LncRNAs in Diabetic Retinopathy with a Focus on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 214, 115643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zhou, M.; Wang, X.; Long, X.; Ye, M.; Yuan, Y.; Tan, W. Aberrant LncRNA Expression in Patients with Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy: Preliminary Results from a Single-Center Observational Study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023, 23, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, H.M.F.; Abdelghany, A.A.; Al Ageeli, E.; Kattan, S.W.; Hassan, R.; Toraih, E.A.; Fawzy, M.S.; Mokhtar, N. Long Non-Coding RNAs Gene Variants as Molecular Markers for Diabetic Retinopathy Risk and Response to Anti-VEGF Therapy. Pharmgenomics Pers. Med. 2021, 14, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foronjy, R. Commentary on: The Potency of LncRNA MALAT1/miR-155 in Altering Asthmatic Th1/Th2 Balance by Modulation of CTLA4. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20190768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Baskoro, H.; Rennard, S.I.; Seyama, K.; Takahashi, K. MicroRNAs as Therapeutic Targets in Lung Disease: Prospects and Challenges. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2015, 3, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaldi, P.J.; Guo, F.; Qiao, D.; Du, F.; Naing, Z.Z.C.; Li, Y.; Pham, B.; Mikkelsen, T.S.; Cho, M.H.; Silverman, E.K.; Zhou, X. Identification of Functional Variants in the FAM13A Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Genome-Wide Association Study Locus by Massively Parallel Reporter Assays. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vij, N. Nano-based theranostics for chronic obstructive lung diseases: challenges and therapeutic potential. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2011, 8, 1105–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleasants, R.A.; Hess, D.R. Aerosol Delivery Devices for Obstructive Lung Diseases. Respir. Care 2018, 63, 708–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).