1. Introduction

Global warming has emerged as a significant issue in recent years [

1,

2,

3]. Consequently, various technologies have been developed in the field of renewable energies, including the utilization of solar panels [

4]. An influential factor in optimizing energy conversion through this technology is solar radiation, so considering the panel’s orientation in relation to the sun is crucial, as outlined in [

1]. Mexico features regions with prolonged periods of high solar radiation which offer a natural geography conducive to harnessing this technology to its full potential. Located in the northern part of Mexico, the state of Sonora stands out as the region receiving the highest levels of solar radiation, averaging

, making it an ideal location for the establishment of solar power plants, as discussed in [

5]. The Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) model was employed in [

6] in southern Sonora to assess solar radiation levels across different seasons. Likewise, a study conducted in [

7] explored a photovoltaic installation for the company Sales del Valle S. A. de C. V., aiming to achieve a 28% reduction in energy consumption through the deployment of panels mounted on a mechanical structure.

In solar panel technology, electrical energy conversion is predominantly contingent on the panel’s orientation relative to the sun’s rays and its temperature. In the 2013 study presented in [

8], a comparative analysis between a fixed and a mobile panel demonstrated a 40% increase in electricity generation by manipulating one degree of freedom (DOF) of the panel. The study emphasized the electronic design of the tracking system, while the didactic panel was directly linked to the direct current (DC) motor. Additionally, [

9] proposed the use of a 2-DOF tracker employing 24 volts of direct current (VDC) motors with a speed reducer coupled to the angular movement of the axles holding the panel. Orientation was determined using the algorithm proposed by [

10] as a reference, together with electronic instrumentation; this enabled maximizing power generation, which was subsequently compared with both a fixed system and the proposed system; the result was a 27.98% increase, with a final energy gain of 1.3%. The study was conducted in the municipality of Texcoco, in the State of Mexico.

A comparative study of a 1-degree-of-freedom (1-DOF) and a 2-degree-of-freedom (2-DOF) solar tracker was presented in [

11]. The first case involved the direct coupling of a DC motor to the shaft upon which the solar panel is installed, utilizing corresponding electronics for solar tracking. Subsequently, a second degree of freedom and its corresponding motor were applied to the same system to provide axle movement, complementing the electronic control system. Scale prototypes demonstrated that the 1-DOF system achieved 30% efficiency, while the 2-DOF system reached 40% efficiency when compared to a fixed panel at 21°.

In the same line of research, [

12] presented a study on a 2-degree-of-freedom (2-DOF) tracker employing a worm screw to control panel orientation with direct coupling. DC motors were utilized to control the axle with spur gears. The electronic tracking system and a comparison of the tracker with a fixed panel were also discussed, revealing 30% efficiency when utilizing the proposed mobile system. The physically constructed systems were demonstrated at scale.

A similar proposal was outlined in [

13], where two DC actuators were applied to control both panel and axle movements with direct coupling between the shaft and the motor. The focus was on the system’s electronic instrumentation; however, no evidence of the constructed prototype or field results were provided. In 2017, a 1-degree-of-freedom (1-DOF) tracker was introduced in [

14] that allowed controlling the axle, with the panel fixed at 35.47°. The system employed a DC motor coupled to a worm screw reducer connected to the shaft to facilitate the corresponding movement. The implementation of a solar panel parallel to the tracker was proposed, using a reflective surface to enhance electrical energy generation. The results were compared with those of a fixed panel, revealing that the proposed scheme allows for a 71.75% power efficiency compared to the fixed scheme. Similar to previous articles, the focus remains primarily on electronic instrumentation and the tracking algorithm. Meanwhile, [

15] presented a comparative study between a fixed panel and a 2-degree-of-freedom (2-DOF) tracker, with the latter achieving 25% efficiency. The tracker utilizes a 100 W solar panel, and both panel and axle movements are individually controlled by a chain transmission system. The analysis presented in [

14] concentrates on the development of electronic instrumentation for actuator tracking and control.

In 2019, [

16] outlined the prototype for a 2-degree-of-freedom (2-DOF) tracker in which solar alignment is determined by an efficient orientation chart based on the presented electronic design. It employs a linear actuator for the angular control of the panel while proposing a 2-step bevel gear and worm screw system for the axle. The study, conducted in Obregón, Sonora, Mexico, demonstrated a 24% increase in electrical energy compared to a fixed system. The prototype was constructed at a 1:1 scale and incorporates four 250 W panels.

In [

17], servomotors with encoders were employed to drive both the panel and the axle of a 2-degree-of-freedom (2-DOF) tracker through a pair of spur gears. The authors detail the acquisition, processing, and control system for a 70 W panel reporting that building a 1:1 scale prototype resulted in a 24.7% efficiency improvement over a fixed system. Similarly, [

18] introduced a prototype for a 2-DOF solar tracker utilizing linear actuators for panel and axle control. The 150 W panel was equipped with the corresponding electronic instrumentation, and the proposed system was compared with a fixed system, achieving a 25.19% increase in efficiency. In [

19], a cubic-shaped solar tracker featuring a 10 W panel installed on each edge of the cube was presented, with simultaneous axle movement on each panel facilitated by a chain transmission system. Additionally, the second degree of freedom for the angular movement of the panel utilizes the same transmission system coupled to a mechanism to generate the rocker output. The necessary electronic instrumentation and the system for detecting the position of the sun are presented, and the results were experimentally evaluated, considering cases such as a fixed panel with axle movement (1-DOF), a panel and axle movement (2-DOF), and a solar panel mounted on a structure. The results reveal that the 1-DOF tracker achieves an efficiency of 16.71% compared to the fixed system, while the 2-DOF tracker reaches 24.97%.

The abovementioned works provide a comprehensive approach to solar trackers, prioritizing both the electronic system and the sun position detection system. However, the design of the mechanical system for reducing the energy consumption required by the actuators is often overlooked. With this in mind, the research presented by [

20] focuses on the position development of a 2-DOF parallel manipulator coupled to a solar panel. The full-scale tracker was constructed to generate 400 W, and corresponding experimental tests were conducted, with solar position determined using the Local Condition Index (LCI) function. Meanwhile, the proposal in [

21] employs a 1-DOF tracker where an electric piston coupled to the shaft supporting the solar panel is controlled by a Proportional-Derivative (PD) scheme.

The tracker has also been constructed at a 1:1 scale. Intellectual property protection has been secured through the patent of the mechanical system that facilitates the tracker’s movement, as detailed in [

22], where 3 planar mechanisms are employed to control the tracker’s 2 degrees of freedom. Another patent, focusing on the mechanical system, is discussed in [

23], which enables the control of 1-DOF in the solar panel tracker through a spur gear and worm screw system that can be integrated into the serial control of different solar panels. Meanwhile, [

24] implements a spherical tracker to control 2-DOF of the solar panel using 2 actuators, while [

25] presents the dynamic analysis of a rocker crank mechanism without detailing the procedure for determining the kinematic parameters of velocity and acceleration used in its control scheme. The dynamic equations of this paper are taken from [

26] for application in a solar tracker. In [

25], two offset crank-rocker arms are used to control the 2 DOF in the tracker, focusing on optimization of the transmission angle. The full-scale prototype is built by integrating a solar panel using a worm screw reducer coupled to the electric actuator connected to the crank. Similarly, [

27] constructs a 2-DOF solar tracker using two pairs of offset crank-rocker mechanisms to generate movement. The actuators are equipped with a drum that winds a metal cable, transmitting motion to each degree of freedom. The kinematic equations of motion are not presented in [

27].

A study focused on the kinematic part is presented in [

28] using 6 linear actuators with spherical joints at each end to control the tracker’s 2 degrees of freedom. The position equations are presented to be solved using the Newton-Raphson algorithm and the transformation matrices for velocity analysis. To identify the bed length and position of an offset crank-rocker mechanism from a symmetrical pattern, [

29] presents a hybrid method using the differential evolution and Jaya algorithms. The optimization method takes knowledge of the angular variation of the coupler from the mathematical expression developed in [

31] as a starting point but is developed under the particular condition of zero eccentricity.

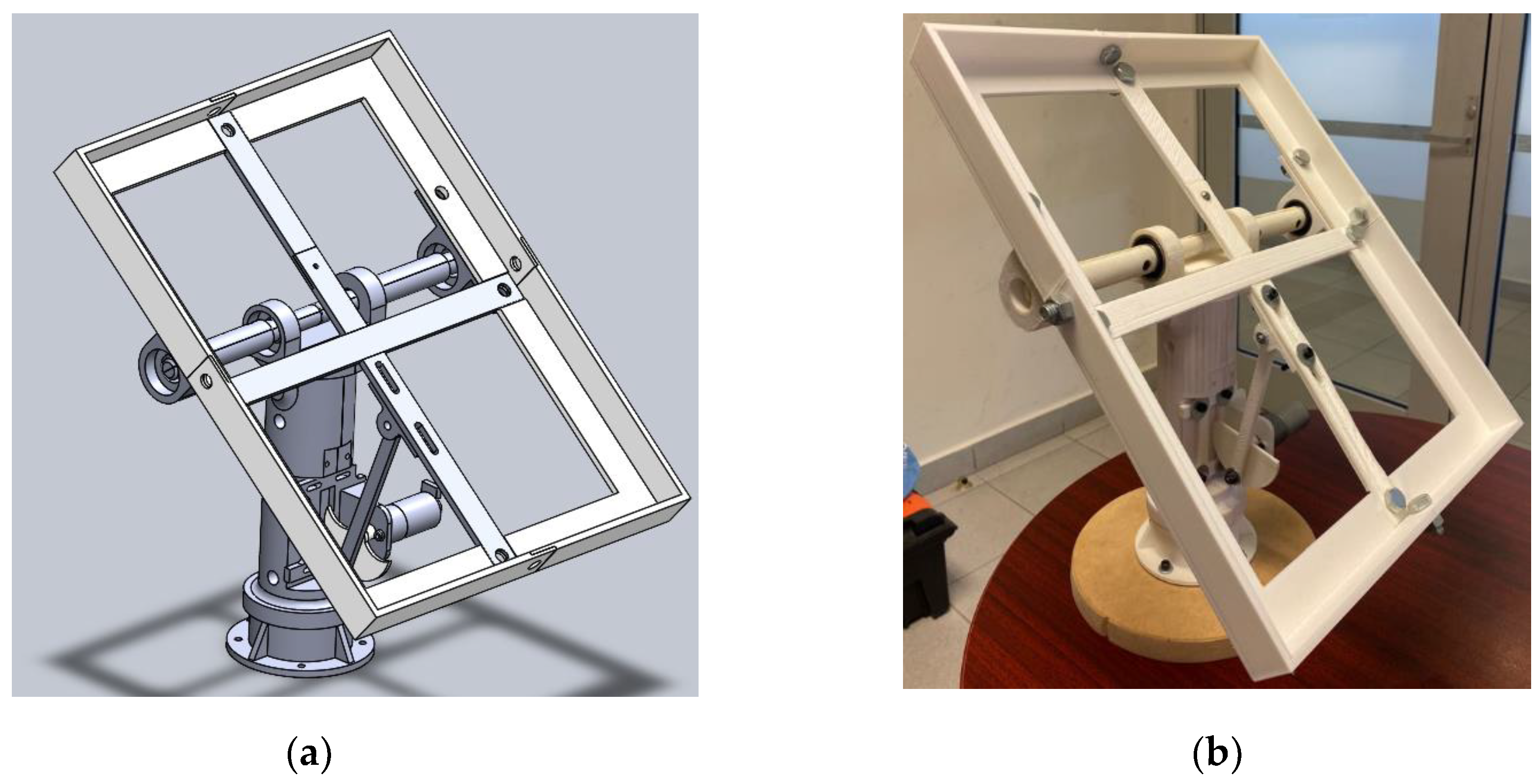

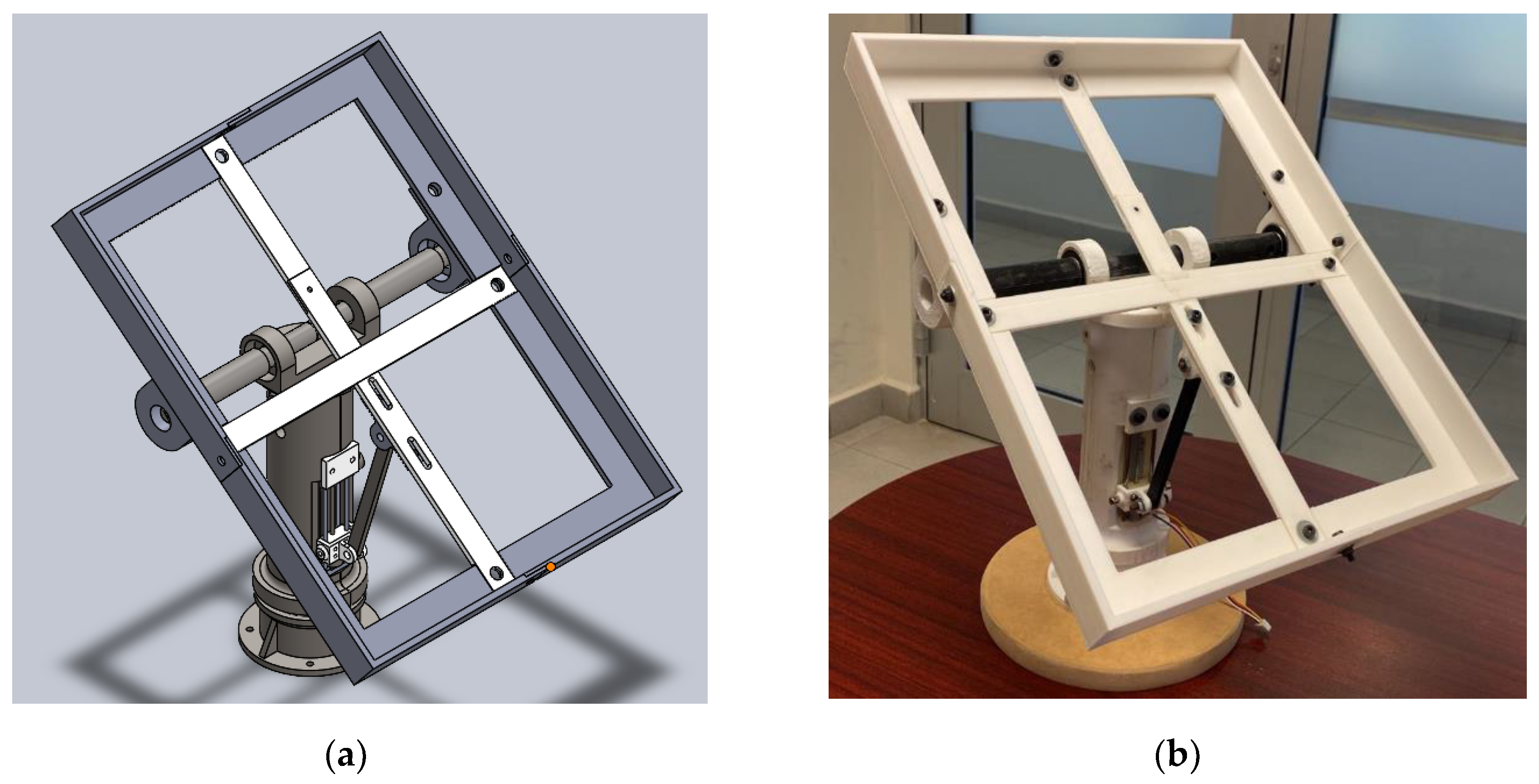

In this study, the kinematic design of two 4-bar planar mechanisms is executed to control 1-DOF of a solar tracker. Validations of the mathematical expressions developed by means of the graphical and numerical methods are also presented, and the corresponding comparison is presented to evaluate their applicability in solar panels. Finally, a practical-scale construction of the proposed mechanisms is undertaken using additive manufacturing to validate the proposed equations and their functionality in the tracker.

2. Planar Mechanisms for the Control of One Degree of Freedom of Solar Tracker

Four-bar mechanisms are deceptively simple systems that require significant effort in kinematic and mechanical design. They are designed to generate a particular output pattern in response to a known input. Their physical simplicity has allowed their widespread use in applications such as mechanical pressure grips, internal combustion engines (piston-connecting rod-crankshaft), orange juicers, and eyelash curlers, among others. Among their advantages are their low maintenance requirements and their robustness for outdoor use. Additionally, their locking positions can be utilized to secure the mechanism, or mechanical systems (such as power screws or speed reducers) can be used to energize the motor only when the tracker’s position needs to be updated.

2.1. Eccentric Crank-Rocker Mechanism

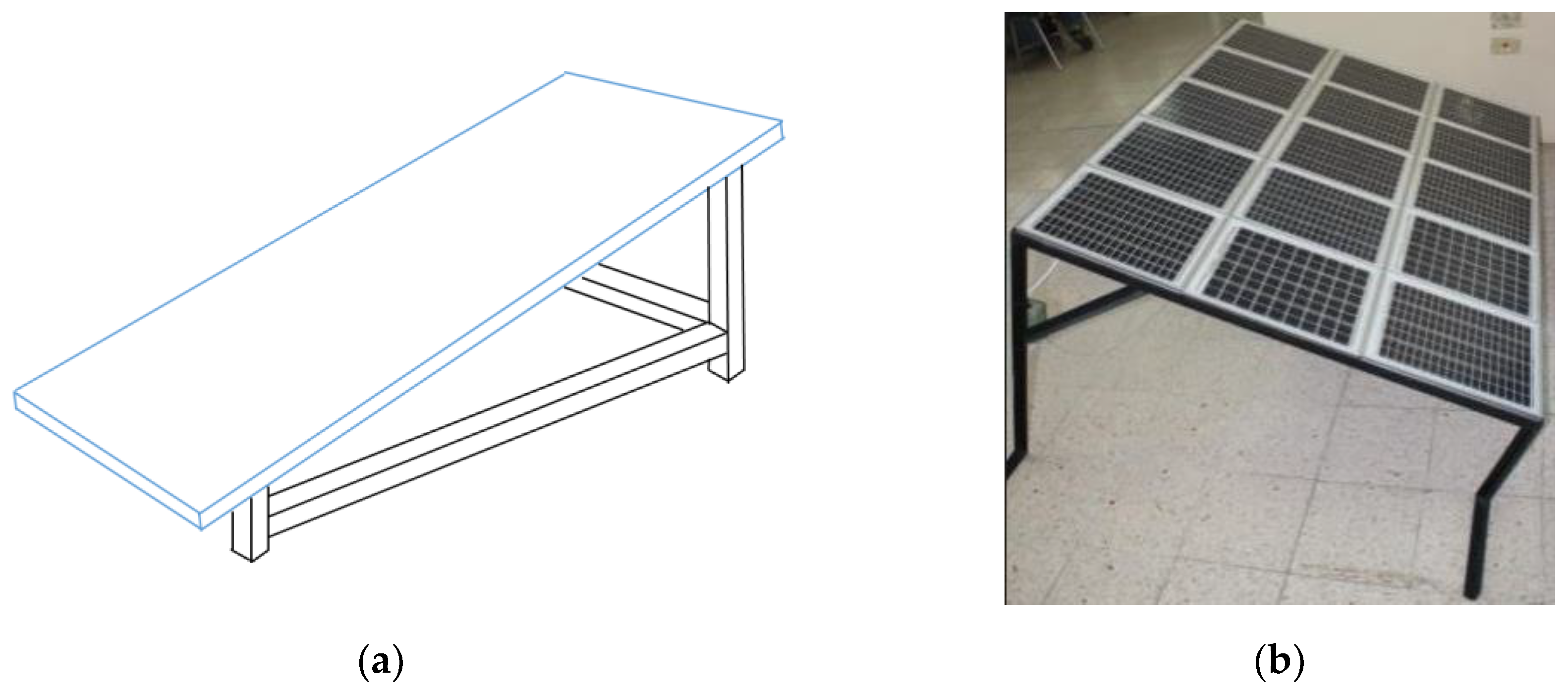

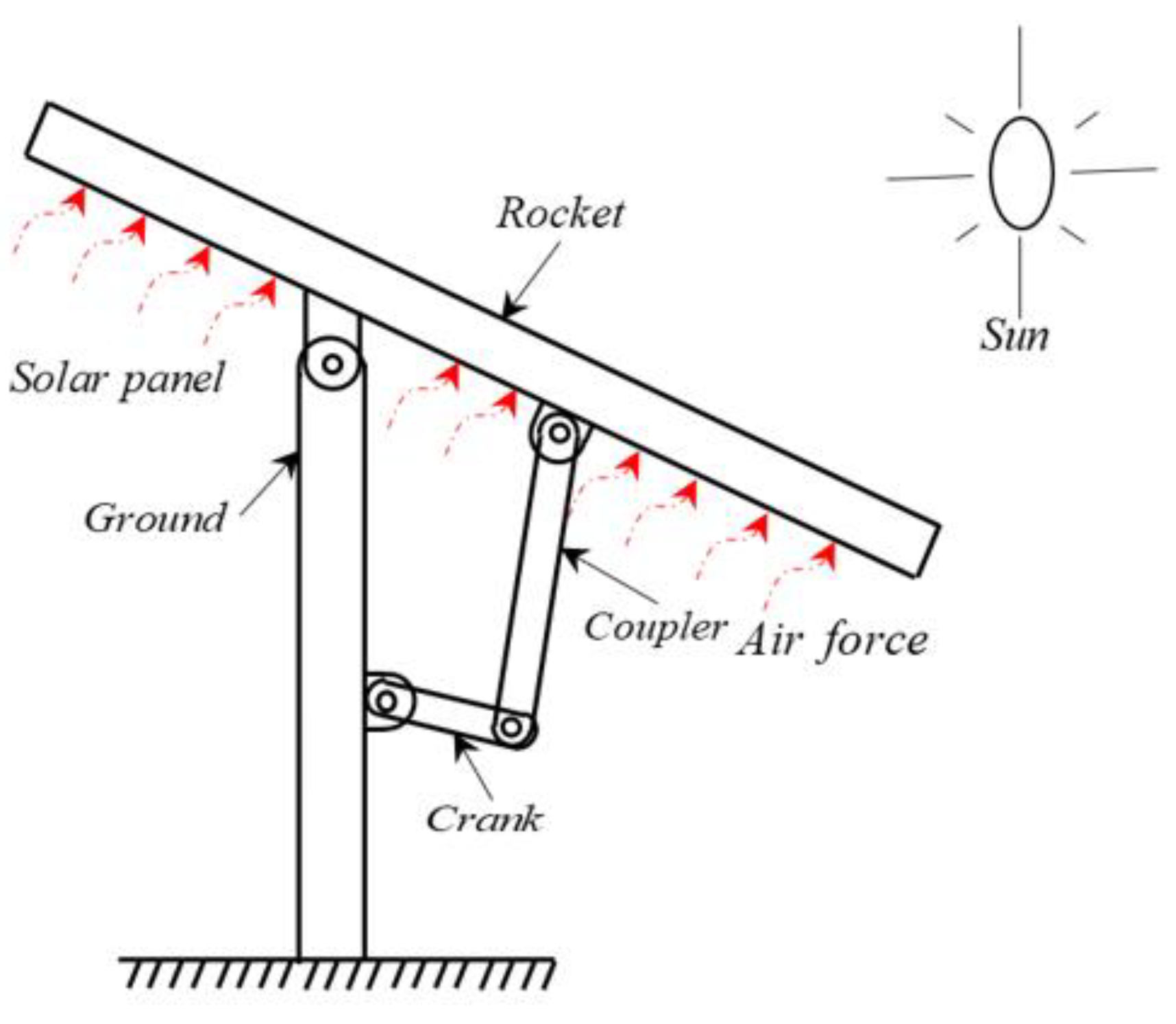

Solar trackers facilitate the conversion of solar energy into electricity using solar panels, whose efficiency is contingent on their position relative to the sun. A prevalent contemporary approach involves installing the solar panels at a fixed orientation angle, as depicted in the following image.

Figure 1a,b depict a panel with a specific tilt, and for the southern region of Sonora, Mexico, a recommended fixed angle of approximately 27° can be applied, as suggested in [

6].

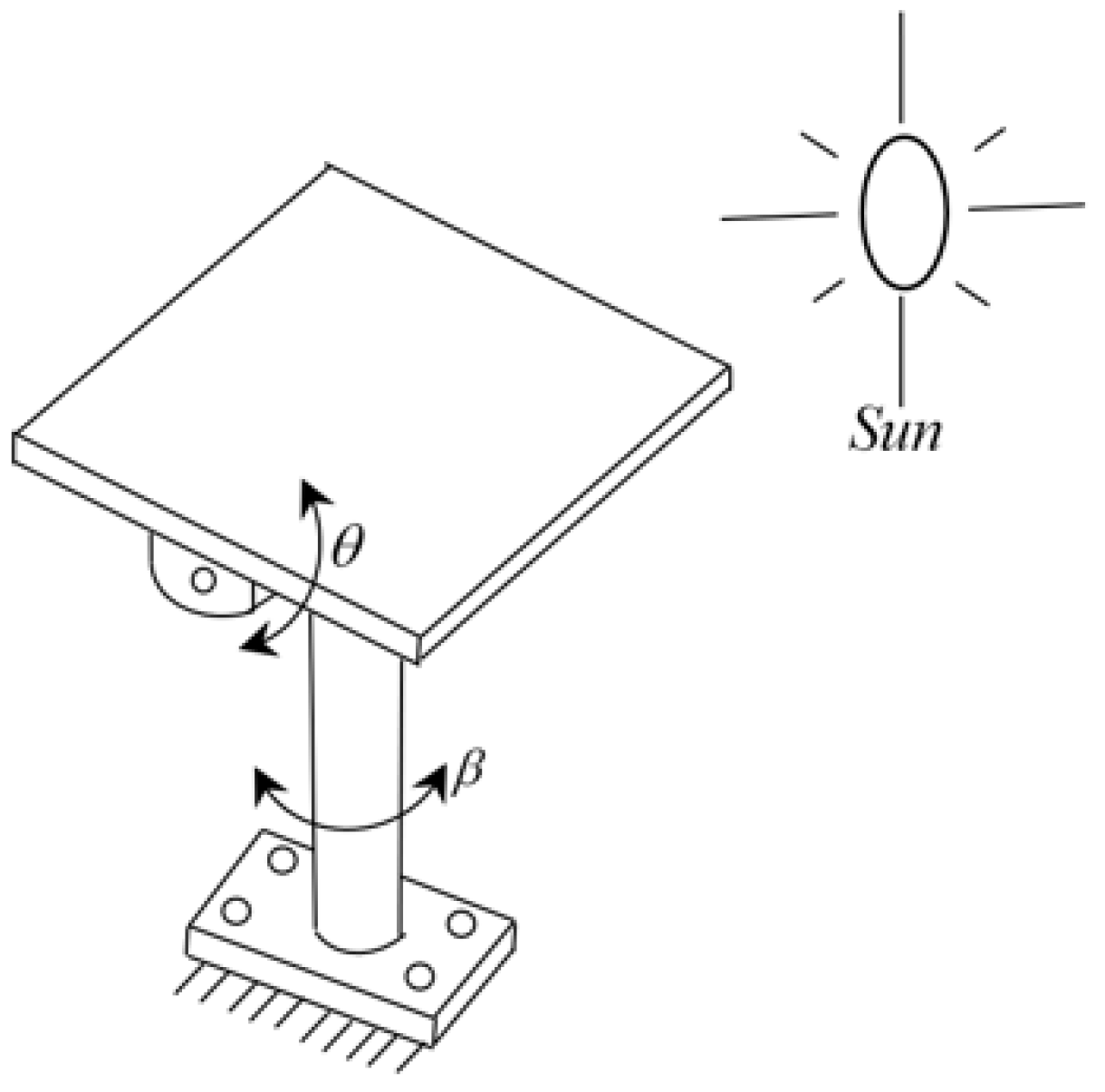

Similarly, to enhance power generation, panel orientation towards the sun is essential, necessitating a system with at least two degrees of freedom, as illustrated in the following figure.

In

Figure 2, the two motions required to optimize the orientation of a solar tracker to solar position are depicted, where the angle

represents the axle movement and

signifies the angular change of the solar panel. Various methods for controlling the required degrees of freedom are discussed in [

30]. Nevertheless, within the mechanical domain, purpose-specific mechanisms like 4-bar planar mechanisms can be utilized to control one degree of freedom in a solar tracker and integrate it into renewable energy systems.

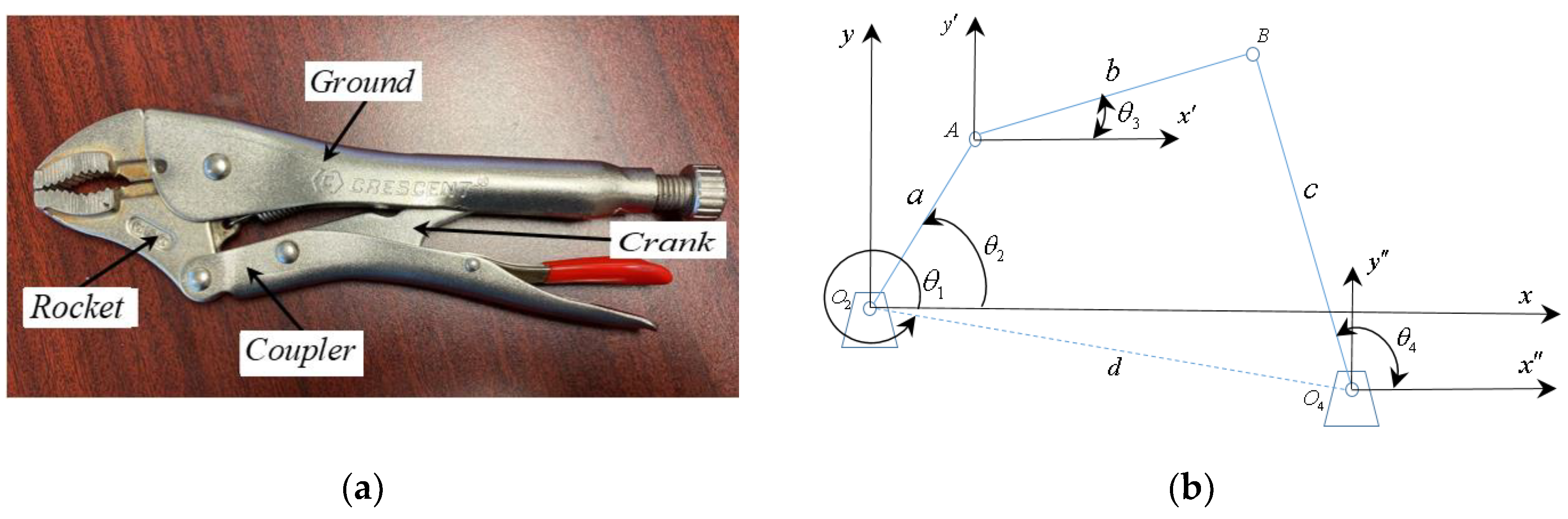

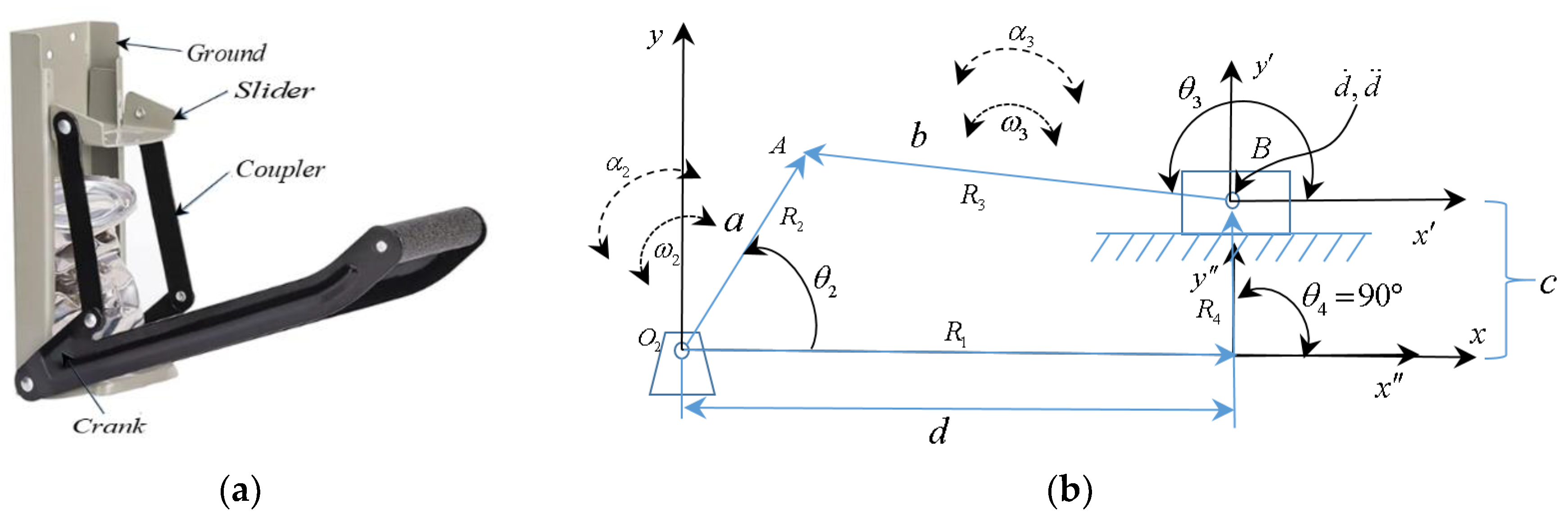

This is a planar mechanism designed to generate a particular output pattern, consisting of 4 elements: ground, crank, coupler, and rocker arm. A common application of this element is in mechanical locking pliers, as shown in

Figure 3a.

Figure 3a depicts mechanical locking pliers, where the input force is applied to the coupler. For analysis, the eccentricity is assumed to be zero, and its mathematical solution, considering the crank as the input link, is detailed in [

31,

32]. However, a comprehensive solution for this application necessitates considering eccentricity in the mechanism, as illustrated in

Figure 3b. In this same figure, the lengths of the links are represented by the variables

,

,

, and

with the input force assumed to be located at link

, representing its crank. The output link corresponds to link

, the rocker arm. The corresponding vector diagram comprises a set of vectors in polar coordinates, as presented in

Figure 4.

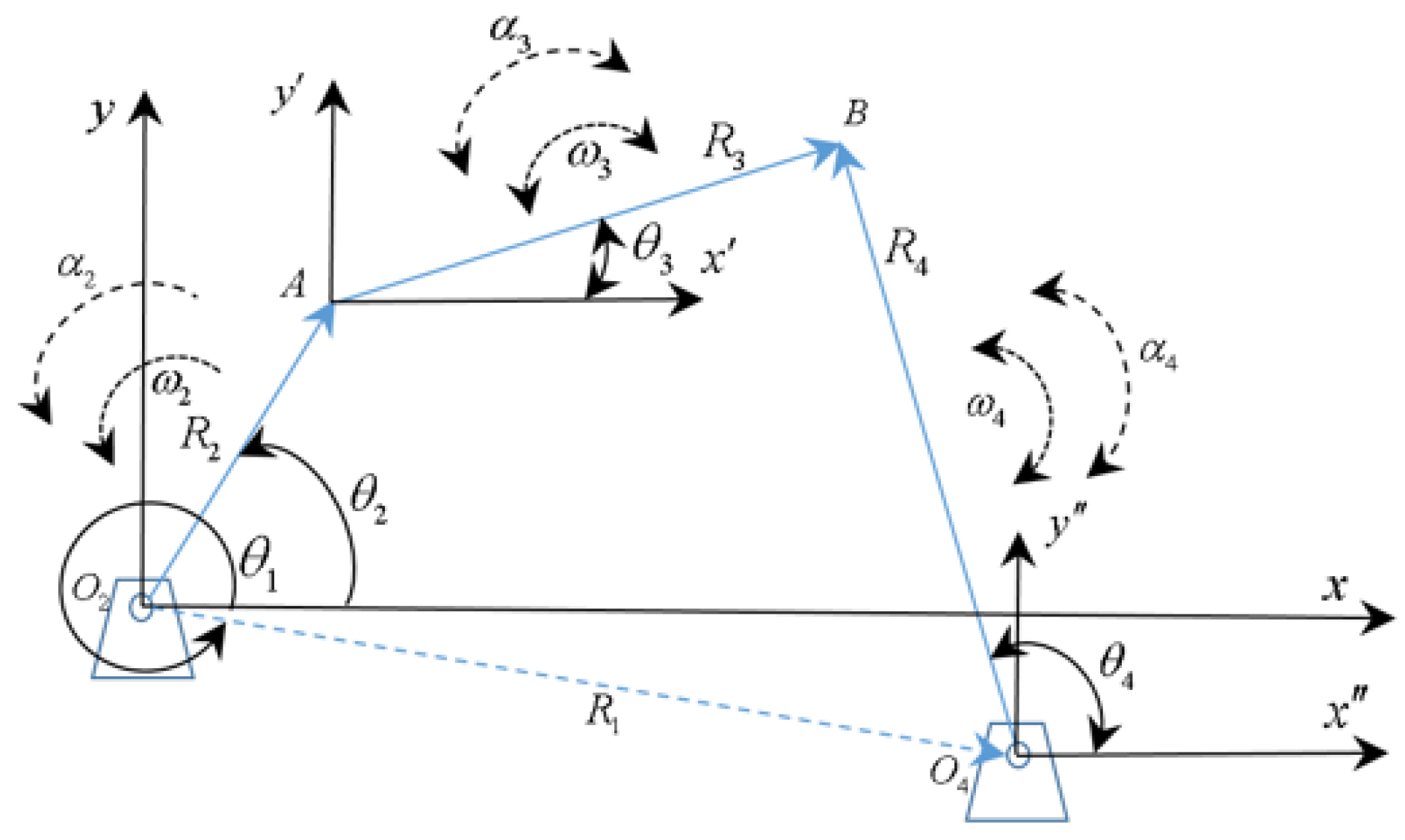

Note that in

Figure 4, the angular value of the frame is non-zero (

), generating an eccentricity in the mechanism and its general solution. Likewise, the links become vectors, originating in the fixed (

) and floating (

,

). coordinate systems. Therefore, the position equation given by the following expression is obtained from

Figure 4:

Equation (1) represents the general vector position equation for the eccentric crank-rocker mechanism. The solution procedure using the complex method is detailed in [

31], resulting in the position equations for the coupler and rocker, given below.

and

Where the general constants are expressed as follows.

Equations (2) and (3) represent the general solution for the offset crank-rocker mechanism, constituting the general equations for this planar device, unlike the system presented in [

31], which provides a specific solution. The velocity equations for the mechanism are expressed by the following expressions:

and

Equations (4) and (5) represent the angular velocities of the coupler and the rocker, respectively.

Likewise, the angular acceleration equations are given by the following expressions:

and

where Equations (6) and (7) represent the angular accelerations of the coupler and the rocker, respectively.

These general expressions for angular acceleration will allow determining the magnitude values of the inertial torque at the center of gravity in the coupler and rocker links. Likewise, Equations (6) and (7) make it possible to calculate the tangential component of each link, while the angular velocities given in Equations (4) and (5) provide the normal component. By vectorially summing these two components of acceleration, the linear acceleration at the center of gravity of each link is found, where the linear inertial force will act. The inertial torque and linear inertial force are fundamental elements for the dynamic analysis of machines and mechanisms.

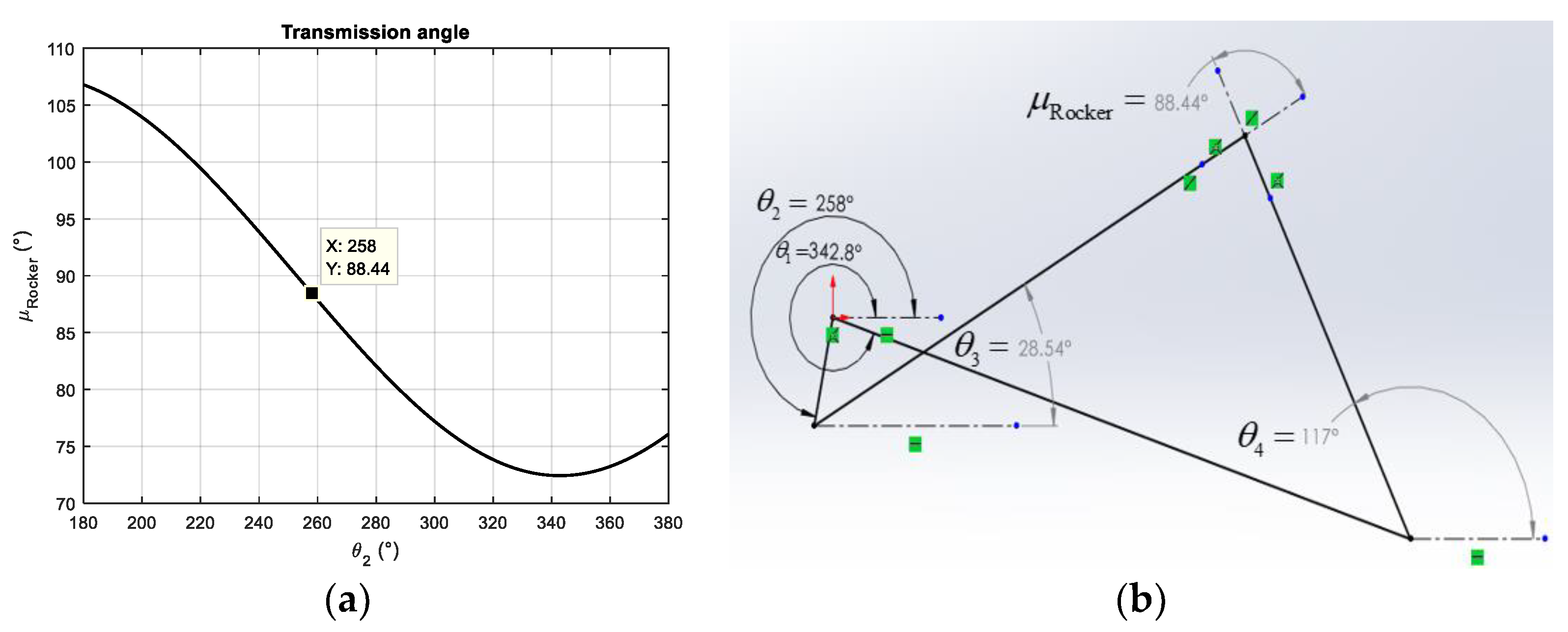

For this mechanism, the transmission angle is given by Equation (8).

Finally, it is emphasized that Equations (2) to (7) represent the general solution for the crank-rocker mechanism, unlike the particular solution presented in [

31]. This generalization is achieved by solving this mechanism for

. In the particular case where the eccentricity is zero, distinct forward and reverse velocities are generated in the output link, directly affecting the angular and linear acceleration patterns. The coupling of the crank-rocker to the solar tracker is accomplished by incorporating a non-zero eccentricity, which allows an actuator to be inserted into the crank, while the rocker will serve as the base for the solar panel movement, as illustrated in

Figure 6.

2.2. Eccentric Crank-Slider Mechanism

Another mechanism architecture is the crank-slider. A common application of this element can be found in a can crusher, as presented in

Figure 5a below.

The schematic diagram can be seen in

Figure 5b. In this latter figure, the input link is the slider represented by node B. Therefore, the known variables are considered to be:

,

,

,

, while the variables to be determined are

and

. The vector equation for crank-slider position is expressed in the following equation:

Using the methodology presented in [

30], the position equations for the coupler link and the crank are given by the following mathematical expressions:

and

where:

Equations (10) and (11) allow determining the angular position of the crank and coupler for any input value on the slider, whereas in [

31] the input link for the crank-slider mechanism is the crank itself.

and

The velocity at any point of the crank and coupler, respectively, can be determined from Equations (12) and (13), while the mathematical expressions to ascertain the angular acceleration are the following:

and

Equations (14) and (15) allow determining the angular acceleration of the crank and coupler, respectively, which, when combined with Equations (12) and (13), determine the linear accelerations with their angle of incidence — parameters used for the dynamic force analysis of the mechanism.

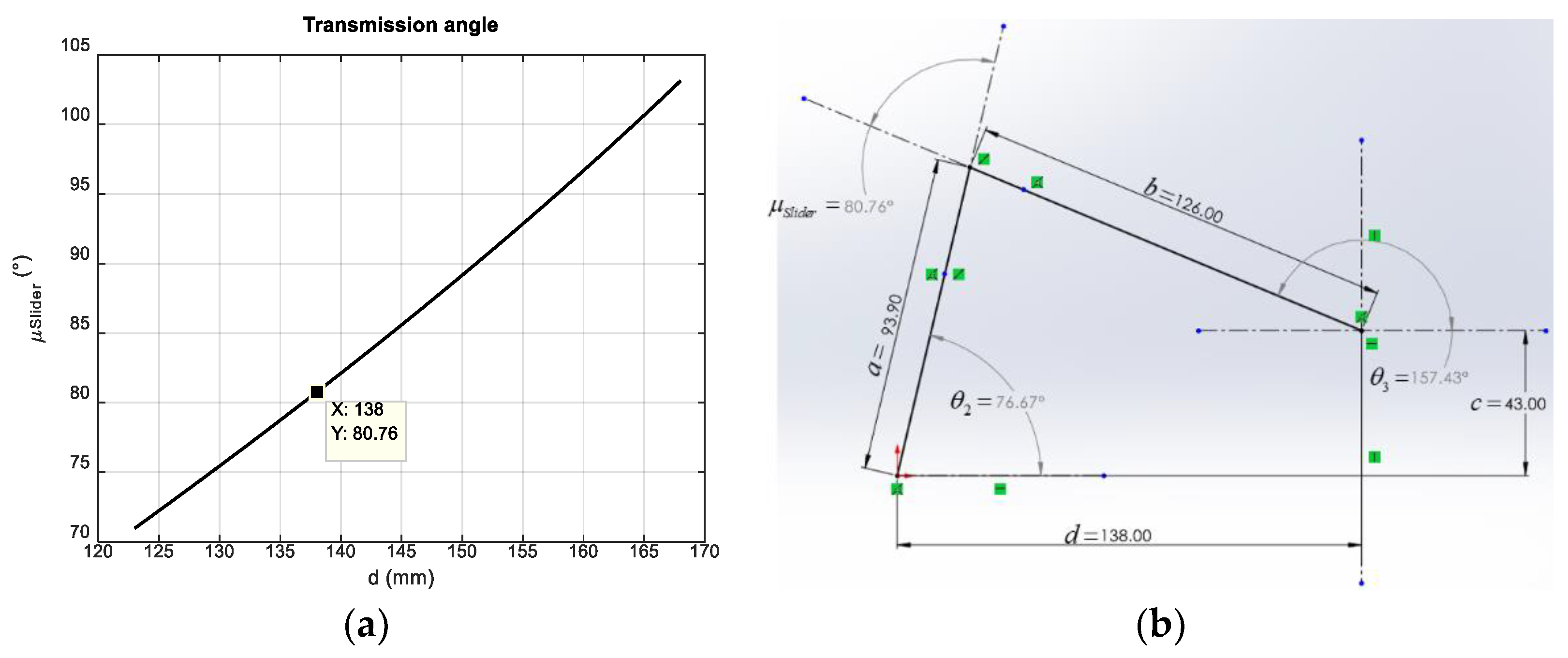

Similarly, its corresponding transmission angle is given by the following equation.

For the specific analysis case where the slider is the input link, eccentricity helps generate smooth angular acceleration, as depicted in

Figure 1. However, this is not the case when the input is in the crank, since it generates a fast forward or return mechanism. One drawback is the challenge of establishing a locking position within the operational range of the mechanism when used in a solar tracker.

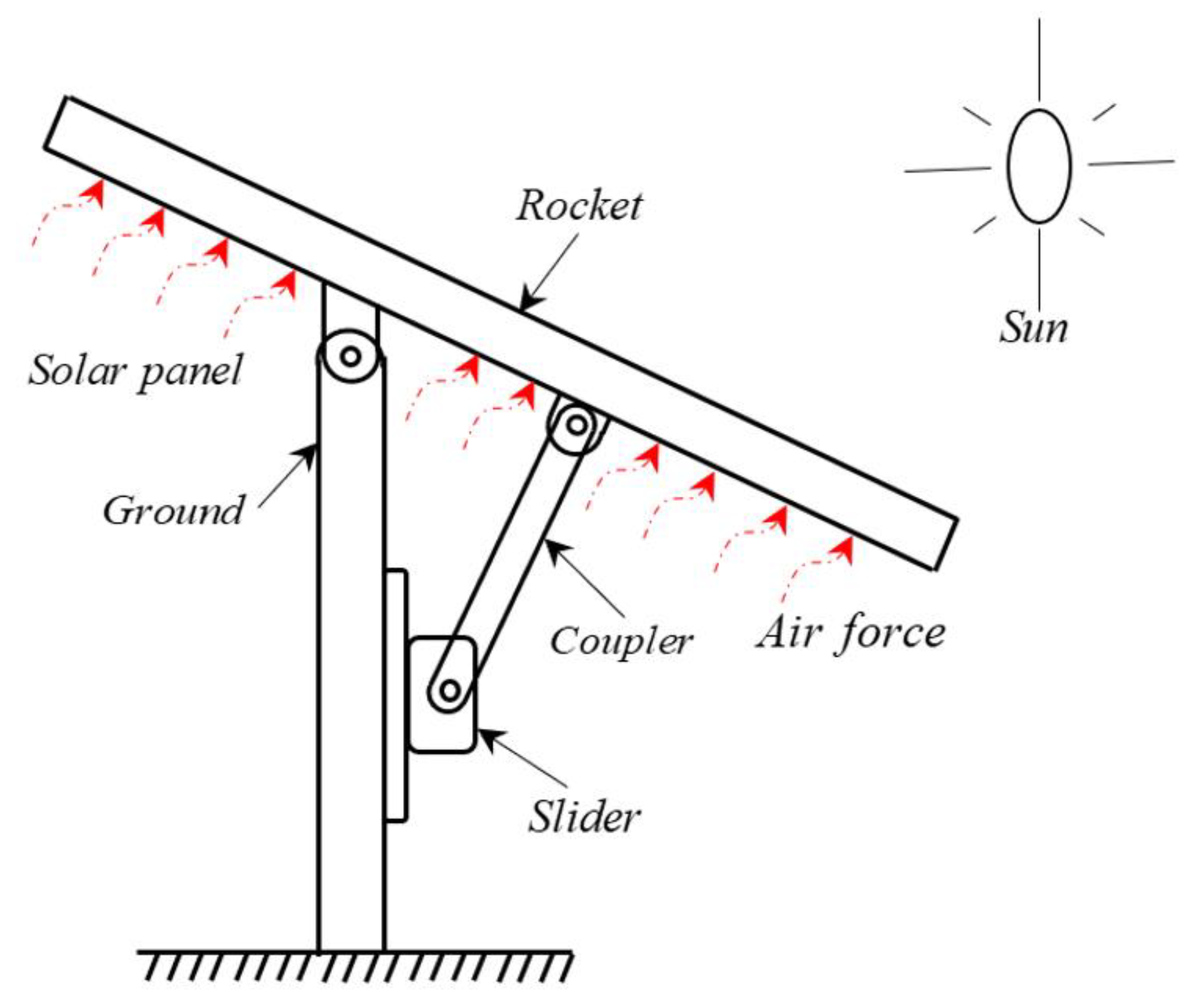

2.3. Coupling Planar Mechanisms to Solar Trackers

The proposed integration of the 4-bar mechanism with rocker arm output and kinematic motions governed by Equations (2) to (7) is shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 6 illustrates the proposed integration of the planar mechanism, where the coupling has been designed to control panel movement, optimizing its positioning relative to the sun. In this figure, the input actuator is assumed to be in the crank link (

), enabling control of the variable

. The rocker arm movement is coupled to the solar panel, and its position is determined by

. The kinematic design proposal is detailed in Figure. 7a,b.

The figure above allows evaluating the functionality of the crank-slider mechanism in order to generate a desired output motion in the solar panel.

Adaptation of the crank-slider mechanism in the solar tracker for the second case study is shown in

Figure 8.

In

Figure 8, it can be observed that the mechanism’s sliding link represents the force and motion input into the system, while the crank establishes the coupling with the solar panel and represents the output variable of interest (

). The kinematic design proposal is shown in

Figure 9a,b.

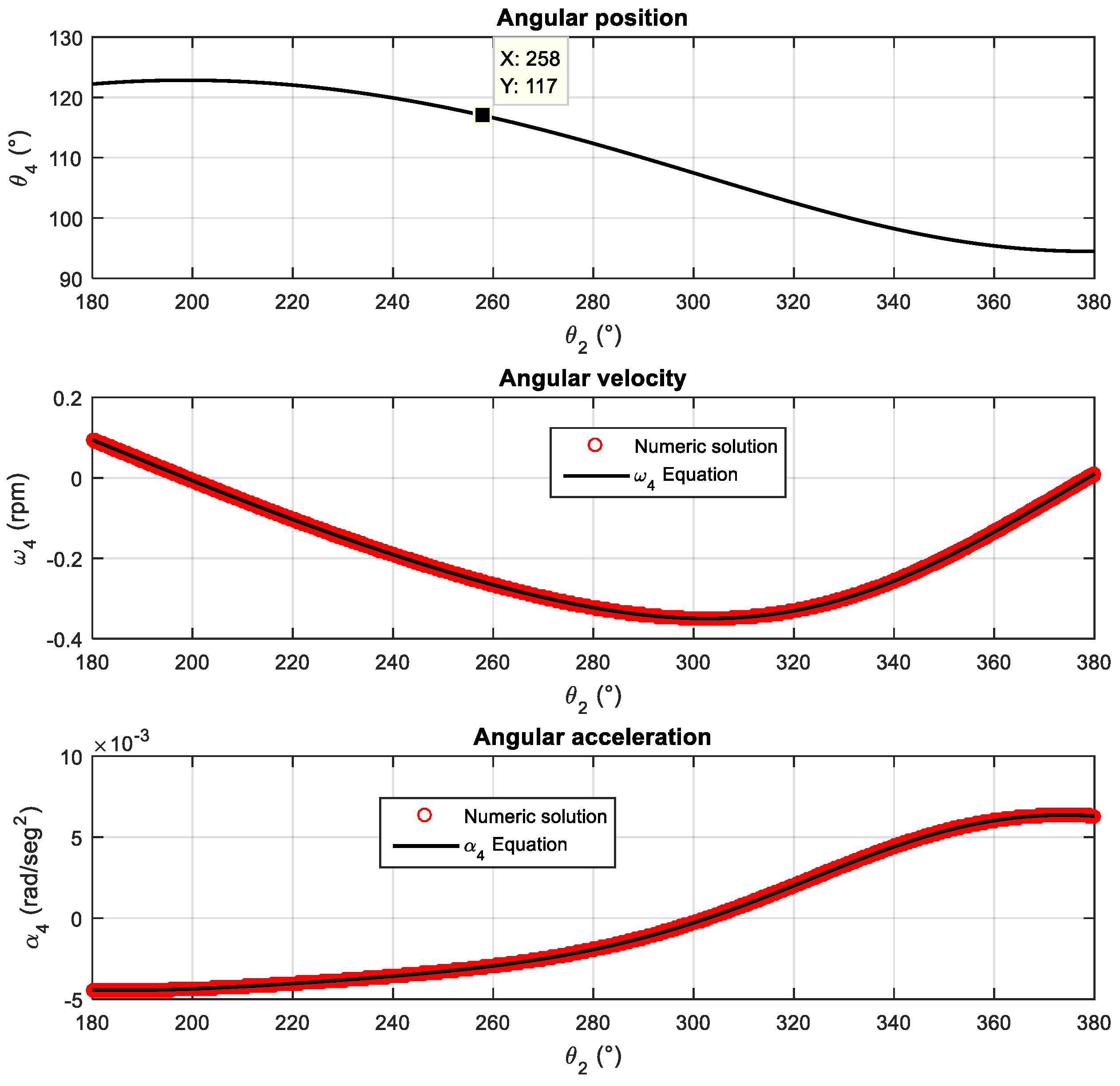

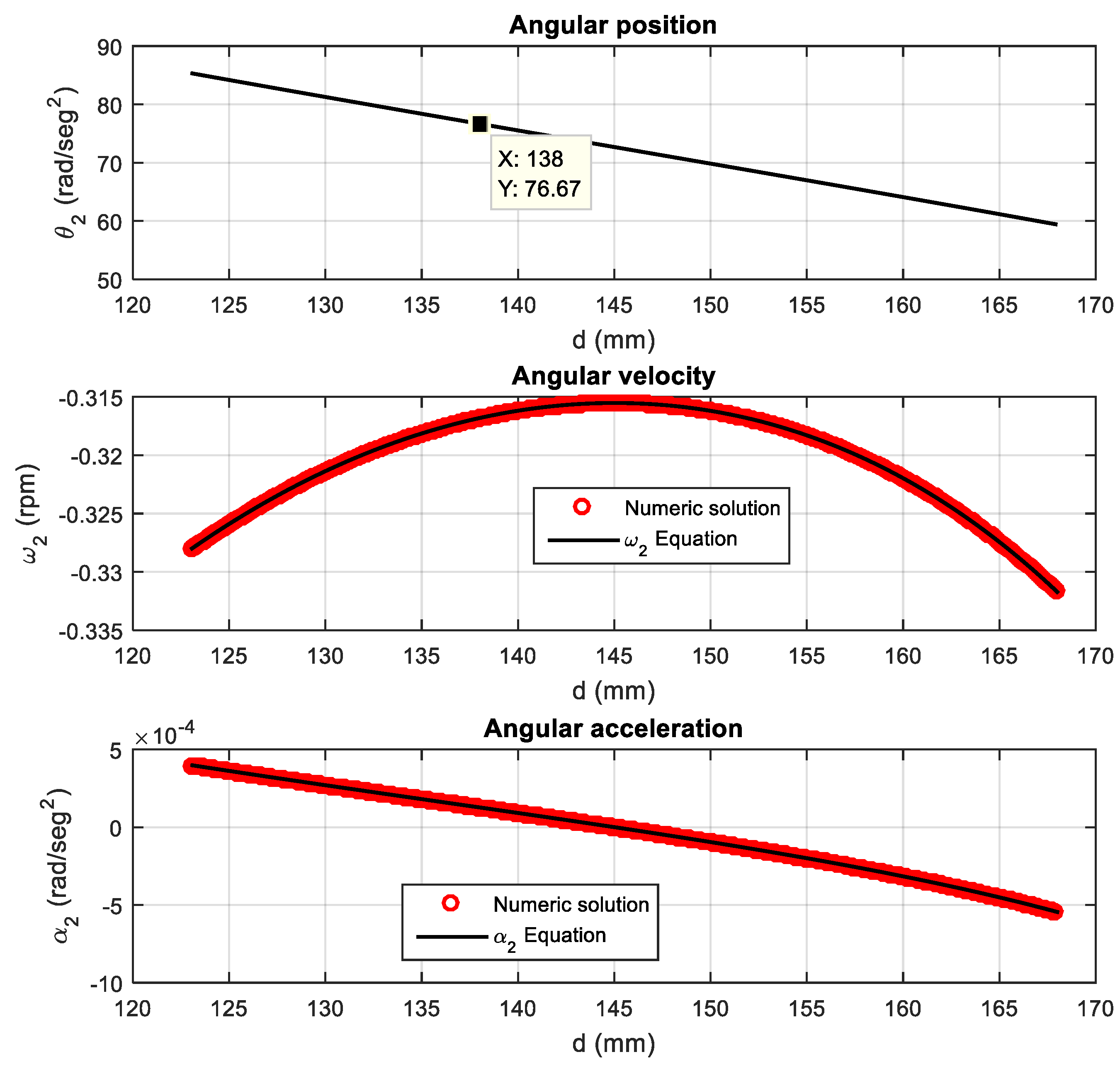

4. Discussion

Solar trackers require at least 2-DOF to position the panel toward the sun for maximum power conversion. However, controlling each degree of freedom necessitates an actuator that consumes a portion of the generated electrical energy. Therefore, research is needed in different mechanical systems with the aim of reducing the required power. In the current research, crank-slider and crank-rocker mechanisms, as shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 9, were employed for the control of 1 degree of freedom, and their operation can be applied for this purpose. Kinematic equations (position, velocity, and acceleration) of the rocker mechanism were developed, considering eccentricity in the frame and input force located on the crank, resulting in Equations (2) to (7), which constitute a general deduction compared to that presented in [

31]. For the crank-slider mechanism, the expressions for position, velocity, and acceleration are given by Equations. (10) to (15), considering that the slider is the link with the input motion. The two mechanisms applied to the solar tracker validate the developed mathematical expressions. Patterns characteristic of position and angular acceleration were obtained based on Equations. (2) to (7) and considering a working range of

, as shown in

Figure 10. When compared with corresponding patterns for the crank-slider (see

Figure 11), it is observed that the solar panel exhibits smoother motion in position and angular acceleration with the latter mechanism. It is therefore recommended to use the 4-bar crank-slider mechanism to control 1 degree of freedom of a tracker.

A measurement of the quality of the proposed mechanisms was also performed through the study of the transmission angle concept. This showed that the crank-rocker and crank-slider mechanisms are within the recommended range , with the slider mechanism showing a lower .

During experimental tests of the constructed prototypes, the crank-rocker mechanism (see

Figure 7 (b)), whose actuator consists of a DC motor and a gear reducer, required a constant power supply to sustain the panel in the desired position. In the case of the crank-slider (see

Figure 9b)), the actuator is installed in the slider and comprises a DC motor directly coupled to a lead screw, allowing the solar panel to remain in the desired position even when deenergized.