Submitted:

30 June 2024

Posted:

02 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seed materials and Its Multiplication

2.2. Biochemical Analysis of Abrus Seeds

2.2.1. Total Moisture Content

2.2.2. Total Phenol Content

2.2.3. Antioxidant Activity

2.2.4. Total Ash Content

2.2.5. Total Protein Content

2.2.6. Total Monomeric Anthocyanin Pigment Content

2.2.7. Total Flavonoid Content

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

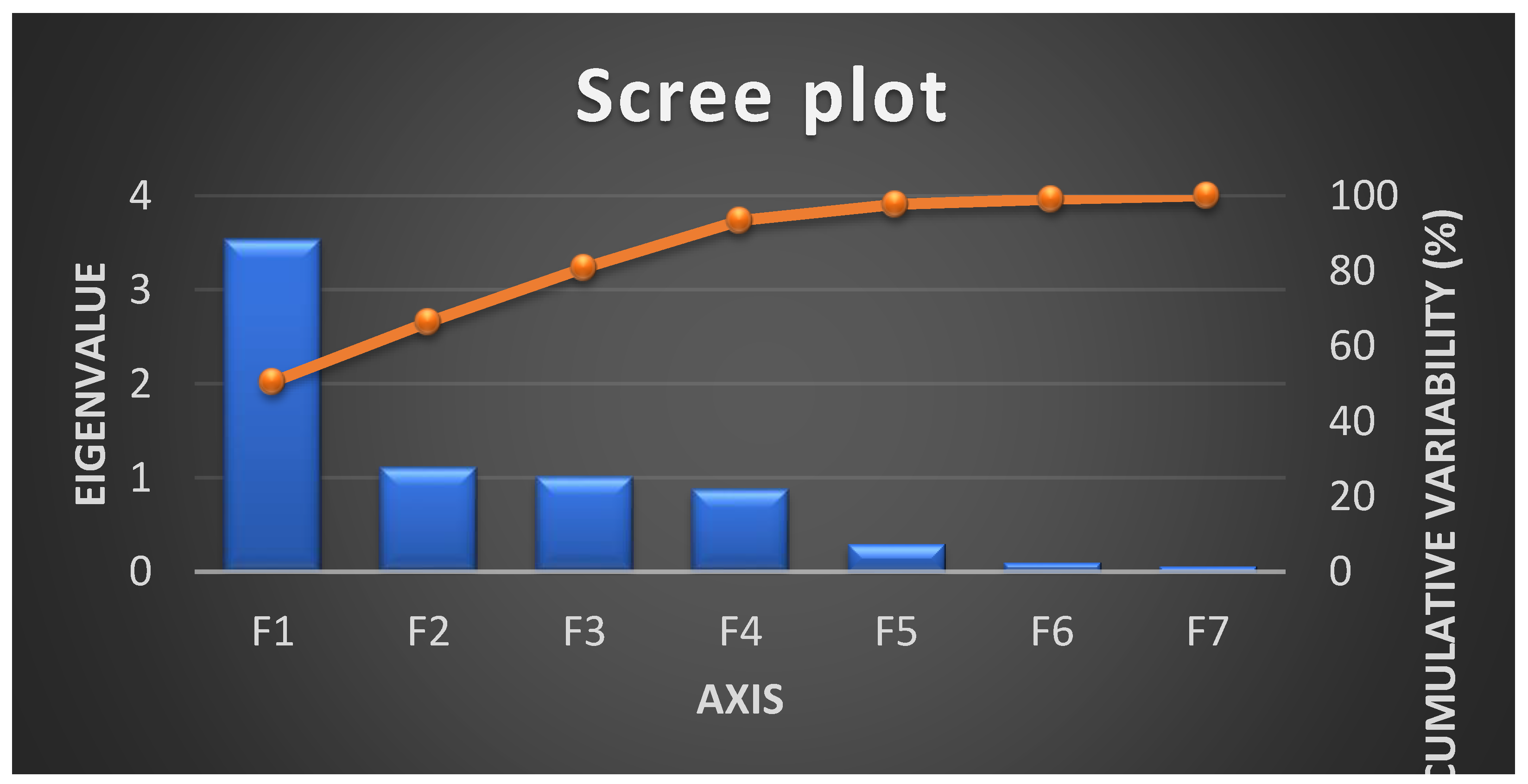

3.1.1. Eigen Values and Variability (%)

3.1.2. Factor Loading

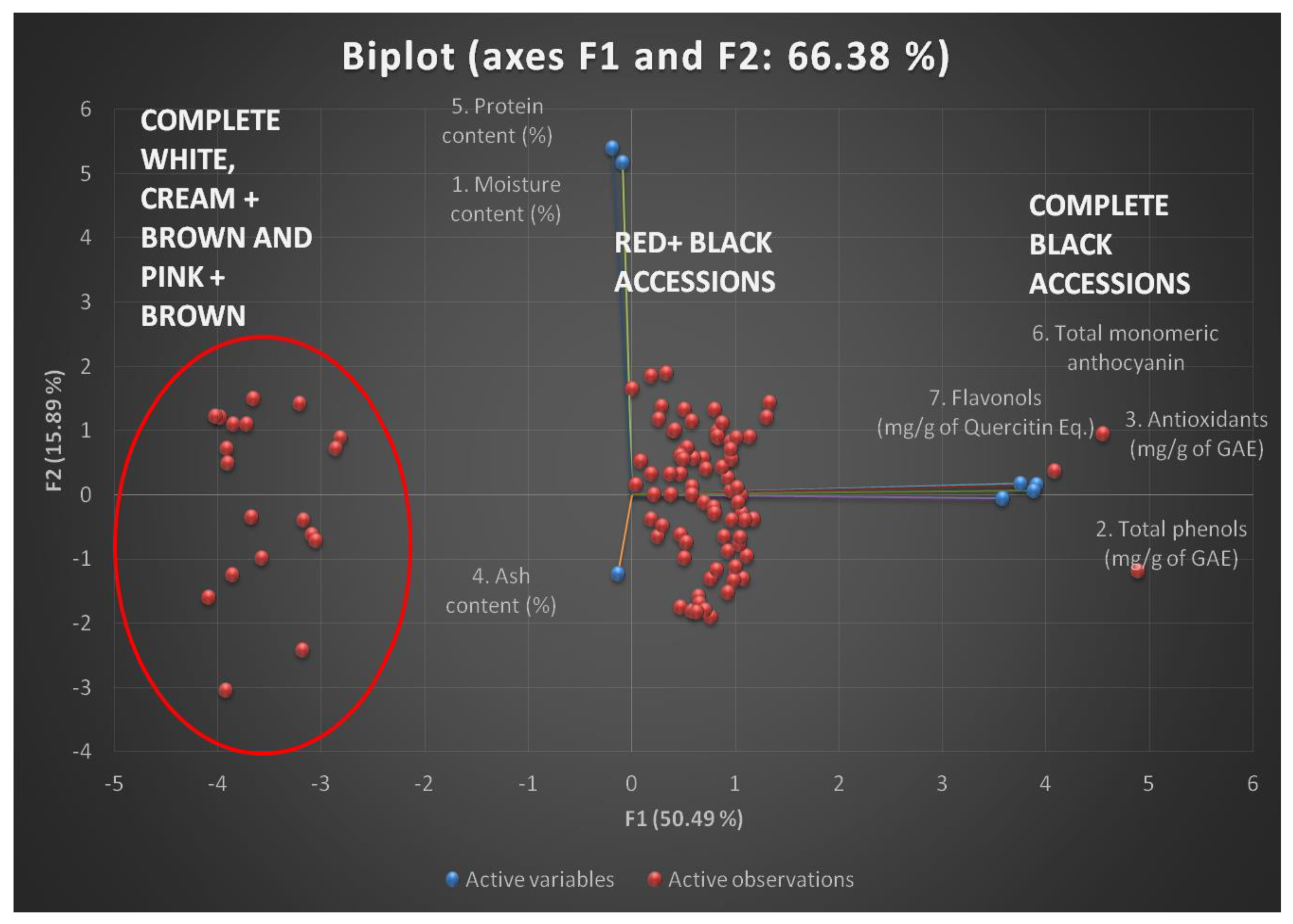

3.1.3. Biplot Analysis

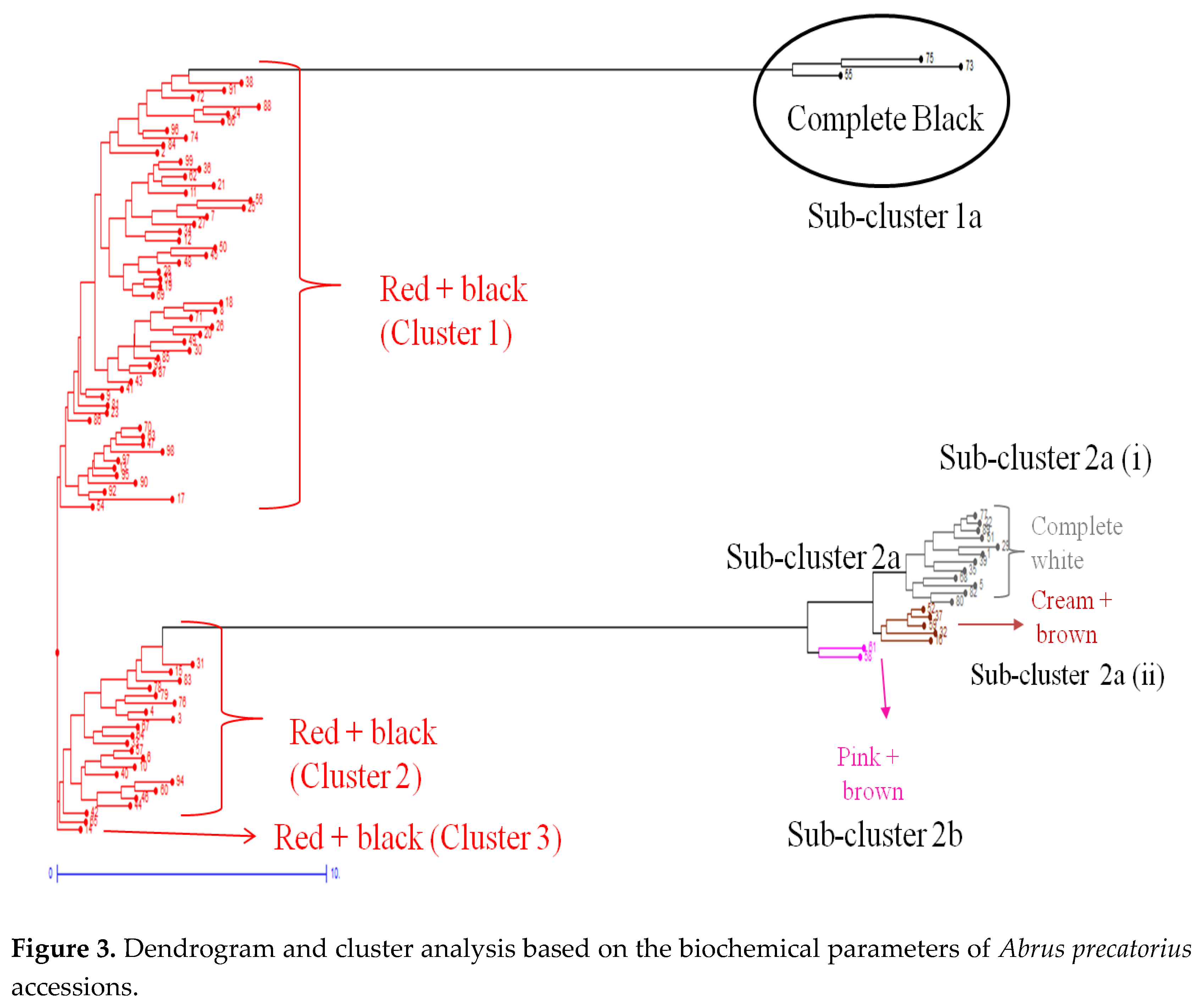

3.2. Cluster Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Awuchi, C.G. Medicinal plants: the medical, food, and nutritional biochemistry and uses. Int. J. Adv. Acad. Res. 2019, 5, 220–241. [Google Scholar]

- Akbar, S.; Akbar, S. Abrus precatorius L. (Fabaceae/Leguminosae). Handbook of 200 Medicinal Plants: A Comprehensive Review of Their Traditional Medical Uses and Scientific Justifications, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, United States, 2020; pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabha, M.; Perumal, C.; Kumar, P.; Soundarrajan, S.; Srinivasan. S.R. Pharmacological activities of Abrus precatorius (L.) seeds. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2015, 3, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, S.; Bhardwaj, R.; Gupta, V. Profiling Total Phenolic Content of Different Seed Colored Germplasm of Ratti (Abrus precatorius). Indian j. Plant Genet. Res. 2021, 34, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Parveen, F.; Narain, P. Medicinal plants in the Indian arid zone, 1st ed.; CAZRI bulletin, Jodhpur, India, 2005; pp. 3.

- Sofi, M.S.; Sateesh, M.K.; Bashir, M.; Ganie, M.A.; Nabi, S. Chemopreventive and anti-breast cancer activity of compounds isolated from leaves of Abrus precatorius L. 3 Biotech. 2018, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, S.; Ghosh, D.; Anusuri, K.C.; Ganapaty, S. Toxicological studies and assessment of pharmacological activities of Abrus precatorius L.(Fabaceae) ethanolic leaves extract in the management of pain, psychiatric and neurological conditions: An in-vivo study. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 7, 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, M.; Siddiqui, N.A.; Gupta, S. Abrus Precatorius (L.): An Evaluation of Traditional Herb. Indo American J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 3, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bhakta, S.; Das, S.K. The medicinal values of Abrus precatorius: a review study. J. Adv. Biotechnol. Exp. Ther. 2020, 3, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhya, S.; Chandrasekhar, J.; David, B.; Vinod, K.R. Potentiality of hair growth promoting activity of aqueous extract of Abrus precatorius Linn. on Wistar albino rats. J. nat. remedies. 2012, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, A.; Zaveri, M. Pharmacognosy, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Abrus precatorius leaf: A review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2012, 13, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Adelowotan, O.; Aibinu, I.; Aednipekun, E.; Odugbemi, T. The in-vitro antimicrobial activity of Abrus Precatorius (L.) fabaceae extract on some clinical pathogens. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2008, 15, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, M.Z.; Ahmad, F.; Kondapi, A.K.; Qureshi, I.A.; and Ghazi, I.A. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of Abrus precatorius (L.) leaf extracts - an in-vitro study. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palvai, V.R.; Mahalingu, S.; Urooj, A. Abrus precatorius (L.) leaves: antioxidant activity in food and biological systems, pH and temperature stability. Int. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 2014, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molgaard, P.; Nielsen, S.B.; Rasmussen, D.E.; Drummond, R.B.; Makaza, N.; Andreassen, J. Anthelmintic screening of Zimbabwean plants traditionally used against schistosomiasis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 74, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadivel, K.; Thangabalan, B.; Mahathi, K.; Sindhuri, T.K.; Srilakshmi, T.; Babu, S.M. Evaluation of in-vitro anthelminthic activity of the crude aqueous leaf extracts of Abrus precatorius (L.). J. Pharm. Res. 2012, 5, 2767–2768. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, S.H.; Lee, E.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.; Shin, M.; Hong, M.; Bae, H. Screening of herbal medicines for recovery of acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2009, 27, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oladimeji, A.V.; Valan, M.F. Molecular docking study of bioactive compounds of Abrus precatorius (L.) as potential drug inhibitors against covid-19 protein 6lu7. Kala sarovar. 2020, 23, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, M.; Saxena, J.; Nema, R.; Singh, D.; Gupta, A. Phytochemistry of medicinal plants. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2013, 1, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, U.; Jacobo-Herrera, N.; Altemimi, A.; Lakhssassi, N. A comprehensive review on medicinal plants as antimicrobial therapeutics: potential avenues of biocompatible drug discovery. Metabolites. 2019, 9, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egbuna, C.; Kumar, S.; Ifemeje, J.C.; Ezzat, S.M.; Kaliyaperumal, S. Phytochemicals as lead compounds for new drug discovery. 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019: pp. 76-78.

- Chen, C. Evaluation of air oven moisture content determination methods for rough rice. Biosyst. Eng. 2003, 86, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, H.G.; Thorpe, W.V. Analysis of phenolic compounds of interest in metabolism. Methods Biochem. Anal. 1954, 1, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of antioxidant power: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, W.; Albert, R.; Deutsch, M.J.; Thompson, N.J. Precision parameters of methods of analysis required for nutrition labeling. Part I. Major nutrients. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 1990, 73, 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oomah, B.D.; Martinez, A.C.; Pina, G.L. Phenolics and antioxidative activities in common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005, 85, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, P.; Kumar, A.; Satyendra, S.; Singh, S.P.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, R.R.; Prasad, B.D.; Kumar, S. Principal component analysis for assessment of genetic diversity in rainfed shallow lowland rice (Oryza sativa L). Curr. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 39, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleem, S.; Tahir, M.; Sharif, I.; Aleem, M.; Najeebullah, M.; Nawaz, A.; Batool, A.; Khan, M.I.; Arshad, W. Principal component and cluster analyses as a tool in the assessment of genetic diversity for late season cauliflower genotypes. Pakistan J Agri. Res. 2021, 34, 176–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Rajcan, I. Biplot Analysis of Test Sites and Trait Relations of Soybean in Ontario. Crop Sci. 2002, 42, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girgel, U. Principle component analysis (PCA) of bean genotypes (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) concerning agronomic, morphological and biochemical characteristics. Appl. ecol. environ. res. 2021, 19, 1999–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratchell, N. Cluster analysis. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems. 1989, 6, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Yoo, H.; Yang, H. Cluster analysis of medicinal plants and targets based on multipartite network. Biomol. 2021, 11, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajaykumar, R.; Harishankar, K.; Chandrasekaran, P.; Navinkumar, C.; Sekar, S.; Sabarinathan, C.; Reddy, B.K. Principle component analysis (PCA) and character interrelationship of irrigated blackgram [Vigna mungo (L.) Hepper] influenced by liquid organic biostimulants in Western Zone of Tamil Nadu. Legume Res. 2023, 46, 346–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, M.C.; Almeida, A.D.; Araujo, L.B.; Dias, C.D.; deOliveira, L.C.; Yokomizo, G.K.; Rosado, R.D.; Cruz, C.D.; Vasconcelos, L.F.; Lima, P.D.; Macedo, L.M. Principal component and biplot analysis in the agro-industrial characteristics of Anacardium spp. Eur. Sci. J. 2019, 15, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahto, D.; Singh, P.K.; Parveen, R.; Nahakpam, S.; Kumar, M. Estimation of genetic diversity by principal component analysis of yield attributing traits in Katarni Derived Lines. Journal of Rice Res. 2022, 15, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | ||

| Eigenvalue | 3.53 | 1.11 | 1.01 | 0.88 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.06 | |

| Variability (%) | 50.49 | 15.89 | 14.48 | 12.59 | 4.23 | 1.42 | 0.90 | |

| Cumulative % | 50.49 | 66.38 | 80.86 | 93.45 | 97.68 | 99.10 | 100.00 |

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | |||||||||

| 1. Moisture content (%) |

-0.022 | 0.719* | 0.353 | -0.596 | 0.050 | ||||||||

| 2. Total phenols (mg/g of GAE) |

0.888* | -0.008 | 0.006 | 0.084 | 0.438 | ||||||||

| 3. Antioxidants (mg/g of GAE) |

0.933* | 0.024 | 0.049 | -0.051 | -0.295 | ||||||||

| 4. Ash content (%) |

-0.033 | -0.171 | 0.932* | 0.316 | -0.010 | ||||||||

| 5. Protein content (%) |

-0.046 | 0.751* | -0.127 | 0.645 | -0.033 | ||||||||

| 6.Total monomeric anthocyanin (mg/100g of C3G) |

0.971* | 0.021 | 0.008 | -0.013 | -0.119 | ||||||||

| 7. Flavonols (mg/g of QE) |

0.964* | 0.010 | -0.027 | 0.013 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Cluster | Sub- cluster | Accessions | Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | IC0553765, IC0400421, IC0397770, IC0322320, IC397936, IC0564539, IC0553727, IC0262948, IC0260022, IC0385638, IC0469946, IC0418116, IC0345234, IC261421, IC0526820, IC0391898, IC0329886 , IC0526819, IC0564695, IC0392859, IC0261023, IC0469934, IC0261408, IC0469932, IC0261401, IC0263057, IC0392836, IC0470438, IC0470922, IC0418103, IC0552617, IC0308748, IC0310646, IC0281057, IC0617322, IC0385619, IC0420958, IC0391888, IC0553504, IC0469963, IC0418119, IC0617321, IC0469967, IC0627451, IC0371792, IC0337216, IC0418115, IC0538733, IC0605146, IC0370449, IC0619016, IC0306236, IC376080, IC0469931 and IC0418097 | 55 |

| a | IC0401666, IC0405311 and IC0605143 | 3 | |

| 2 | - | IC0564732, IC0418120, IC0430717, IC0349804, IC0588655, IC0337202, IC0418096, IC0263011, IC0391892, IC0400325, IC0392838, IC0315333, IC0469939, IC0316266, IC0405295, IC0405304, IC0385520, IC0310926, IC0280795, IC0369145 and IC0400380 | 21 |

| 2a (i) | IC0400492, IC0545109, IC0430870, IC0311747, IC0322486, IC0392840, IC0385635, IC0254919, IC0603047, IC0385644, IC0310647 and IC0395270 | 12 | |

| 2a (ii) | IC0349819, IC0306198, IC0392839, IC0470979 and IC0392846 | 5 | |

| 2b | IC0405305 and IC 392860 | 2 | |

| 3 | - | IC0310855 | 1 |

|

Cluster |

Sub- cluster |

Seed color |

1. Moisture content (%) |

2.Total phenols (mg/g of GAE) |

3. Antioxidants (mg/g of GAE) |

4. Ash content (%) |

5. Protein content (%) |

6.Total monomeric Anthocyanin (mg/100g of C-3-G.) |

7. Flavonols (mg/g of QE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | Red + black | 12.37 | 27.61 | 12.11 | 3.24 | 18.05 | 28.63 | 45.31 |

| a | Complete black | 12.17 | 42.47 | 13.60 | 3.27 | 18.10 | 49.80 | 63.54 | |

| 2 | - | Red + black | 12.26 | 27.91 | 12.67 | 3.34 | 17.69 | 25.22 | 44.16 |

| 2a (i) | Complete white | 12.43 | 18.57 | 1.13 | 3.40 | 18.11 | 0.00 | 26.84 | |

| 2a (ii) | Cream + brown | 11.64 | 23.69 | 1.96 | 3.13 | 17.84 | 0.00 | 27.66 | |

| 2b | Pink + brown | 13.07 | 23.07 | 2.37 | 3.12 | 18. 54 | 0.00 | 33.28 | |

| 3 | - | Red + black | 12.30 | 28.39 | 12.84 | 4.00 | 18.25 | 27.37 | 43.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).