Submitted:

01 July 2024

Posted:

01 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Autonomous Orbit Estimation Models

2.1. Dynamics Model of Low Orbit

2.2. Geomagnetic Field Measurement Model

3. Adaptive Robust Cubature H-Infinity Filter

3.1. Suboptimal Solution of the Extended H-Infinity Filter

3.2. Adaptive Determination of Constraint Level Values

3.3. Adaptive H-Infinity Filtering Algorithm with Adjustable Constraint Level

3.3.1. Spherical Simplex-Radial Cubature Quadrature Rule

3.3.2. Adaptive H-Infinity Filter with Constrained Level Adjustment

4. Simulation and Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhong, W.; Gurfil, P. Mean Orbital Elements Estimation for Autonomous Satellite Guidance and Orbit Control. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2013, 36, 1624–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, X. Angle-Only Cooperative Orbit Determination Considering Attitude Uncertainty. Sensors 2023, 23, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, F.; Gao, D.; Zheng, J. Magnetometer-Based Orbit Determination via Fast Reconstruction of Three-Dimensional Decoupled Geomagnetic Field Model. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2021, 58, 1374–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.-M.; Sun, L.; Cai, J.-N.; Huang, W. A starlight refraction scheme with single star sensor used in autonomous satellite navigation system. Acta Astronaut. 2014, 96, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Wei, C.L.; Liu, L.D. Performance enhancement of X-ray pulsar navigation using autonomous optical sensor. Acta Astronautica 2016, 128, 473–484. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, Y.-J. Fast convergence of orbit determination using geomagnetic field measurement in Target Pointing Satellite. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2013, 30, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Moazzam, A.; Ali, K. A Stochastic Optimization Approach to Magnetometer Calibration With Gradient Estimates Using Simultaneous Perturbations. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2018, 68, 4152–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Gao, D.; Zheng, J. Magnetometer-based autonomous orbit determination via a measurement differencing extended Kalman filter during geomagnetic storms. Aircraft engineering and aerospace technology, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, C.X.; Liu, M. Hybrid geomagnetic attitude and orbit estimation using time⁃differential feedback. Transactions of The Japan Society for Aeronautical&Space Sciences 2021, 64, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.N.; Zhou, H.R.; Zhang, G.Y. . Improving extended Kalman filter algorithm in satellite autonomous navigation. Proceedings of Institution of Mechanical Engineers Part G: Journal of Aerospace Engineering 2017, 231, 743–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julier, S.; Uhlmann, J.; Durrant-Whyte, H.F. A new method for the nonlinear transformation of means and covariances in filters and estimators. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2001, 45, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Xu, L.; Gao, B.; et al. Robust Unscented Kalman Filter-Based Decentralized Multisensor Information Fusion for INS/GNSS/CNS Integration in Hypersonic Vehicle Navigation. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, S.; Li, N. A switch-mode information fusion filter based on ISRUKF for autonomous navigation of spacecraft. Inf. Fusion 2013, 18, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasaratnam, I.; Haykin, S. Cubature Kalman filters. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 2009, 54, 1254–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasaratnam, I.; Haykin, S.; Hurd, T.R. Cubature Kalman Filtering for Continuous-Discrete Systems: Theory and Simulations. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2010, 58, 4977–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghparast, B.; Salarieh, H.; Pishkenari, H.N.; et al. A Cubature Kalman Filter for parameter identification and output-feedback attitude control of liquid-propellant satellites considering fuel sloshing effects. Aerospace science and technology 2024, 144, 108813.1–108813.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potnuru, D.; Chandra, K.P.B.; Arasaratnam, I.; et al. Derivative-free square-root cubature Kalman filter for non-linear brushless DC motors. IET Electric Power Applications 2016, 10, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Performance evaluation of Cubature Kalman filter in a GPS/IMU tightly-coupled navigation system. Signal Process. 2016, 119, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chowdhury, A.; Dey, A.; et al. Adaptive Divided Difference Filter for Power Systems Dynamic State Estimation With Outliers and Unknown Noise Covariance. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2023, 6(Pt.2), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Mili, L. Robust Unscented Kalman Filter for Power System Dynamic State Estimation with Unknown Noise Statistics. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2017, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, F.; Fan, S.; Sun, Q.; Chen, W. A novel resampling-free update framework-based cubature Kalman filter for robust estimation. Signal Process. 2024, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garry, A.; Langford, B.W. Robust extended Kalman filtering. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 1999, 47, 2596–2598. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Hu, J.; Wang, H. Research on integrated navigation method based on adaptive H∞ filter. Chinese Journal of Scientific Instrument 2014, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Feng, J.; Tse, C.K. Spherical Simplex-Radial Cubature Kalman Filter. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2013, 21, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaumik, S.; Swati, F. Cubature quadrature Kalman filter. IET Signal Processing 2013, 7, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

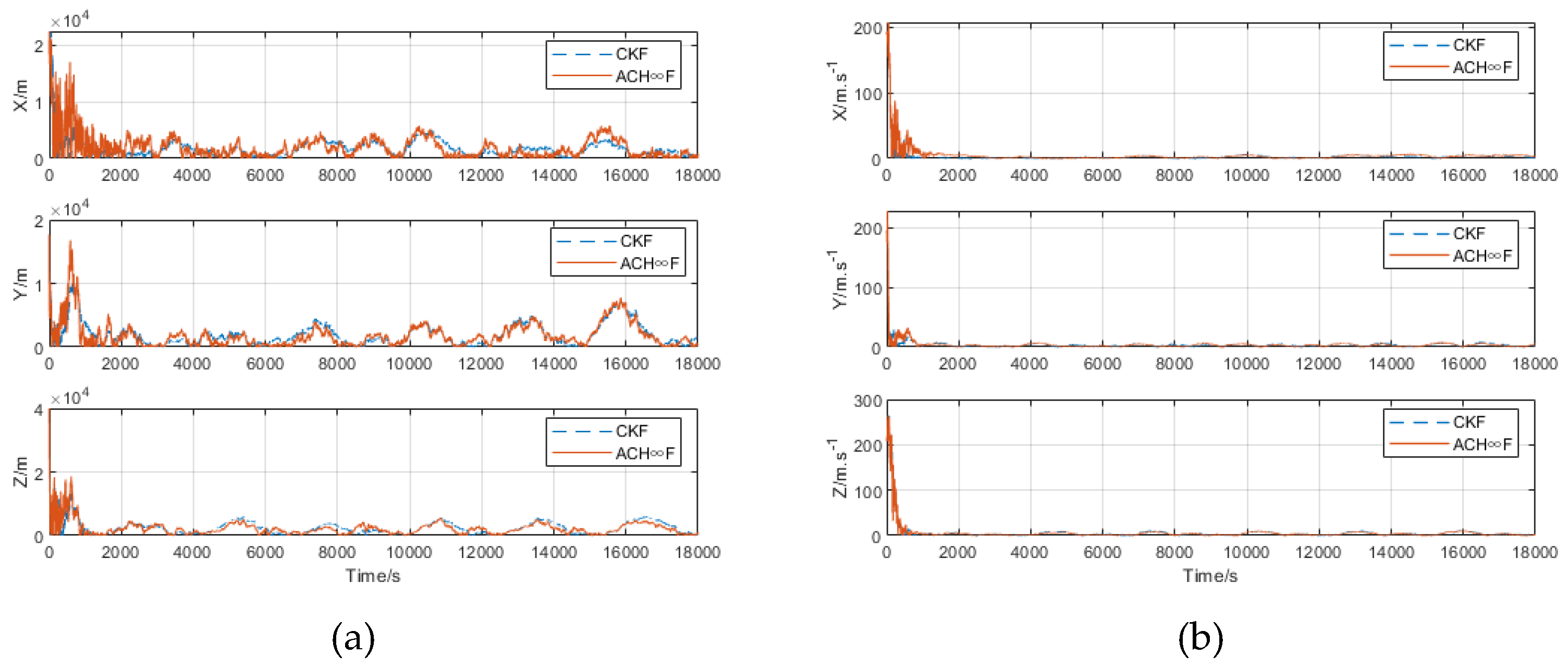

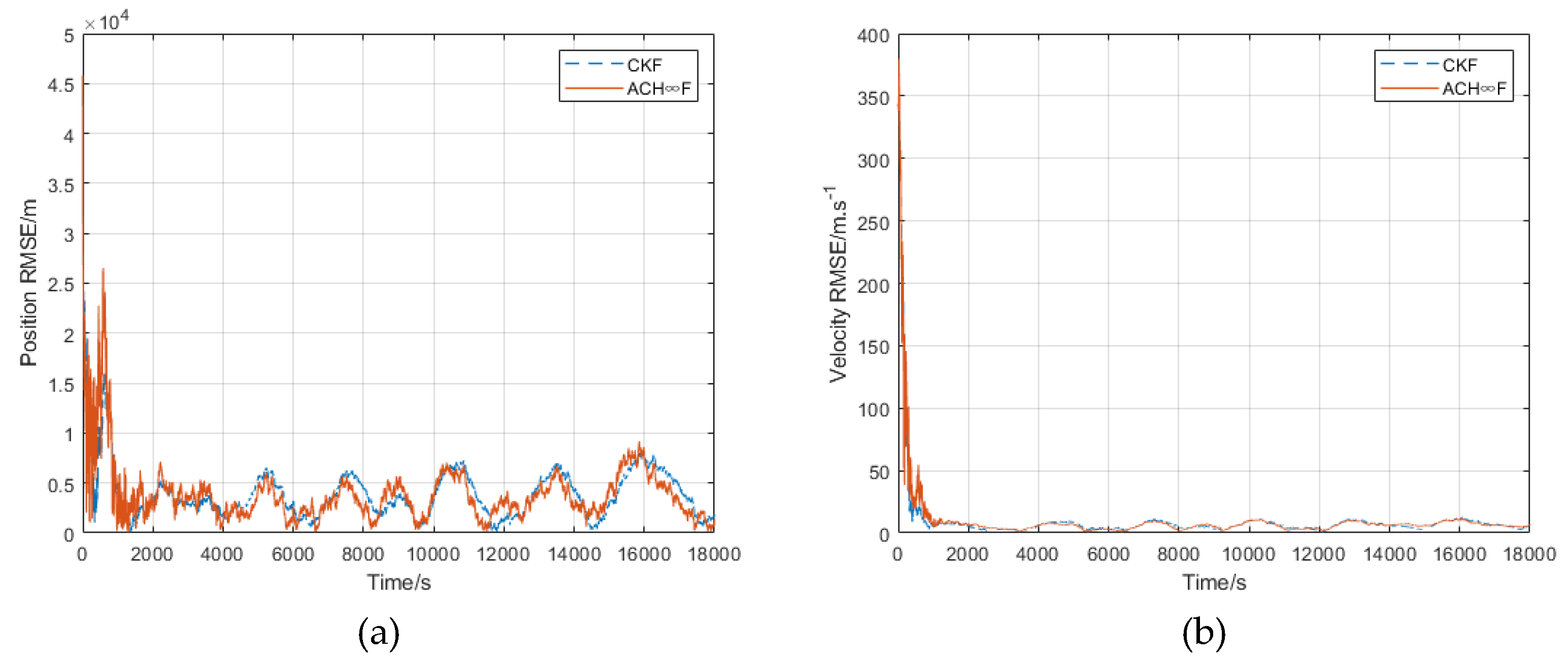

| Filters | Average Positioning RMSE | Average Velocity RMSE |

|---|---|---|

| CKF | 3769.6 | 6.2005 |

| ACH∞F | 3487.3 | 6.0082 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).