Submitted:

28 June 2024

Posted:

01 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Preprocessing

2.2. Labels Mapping

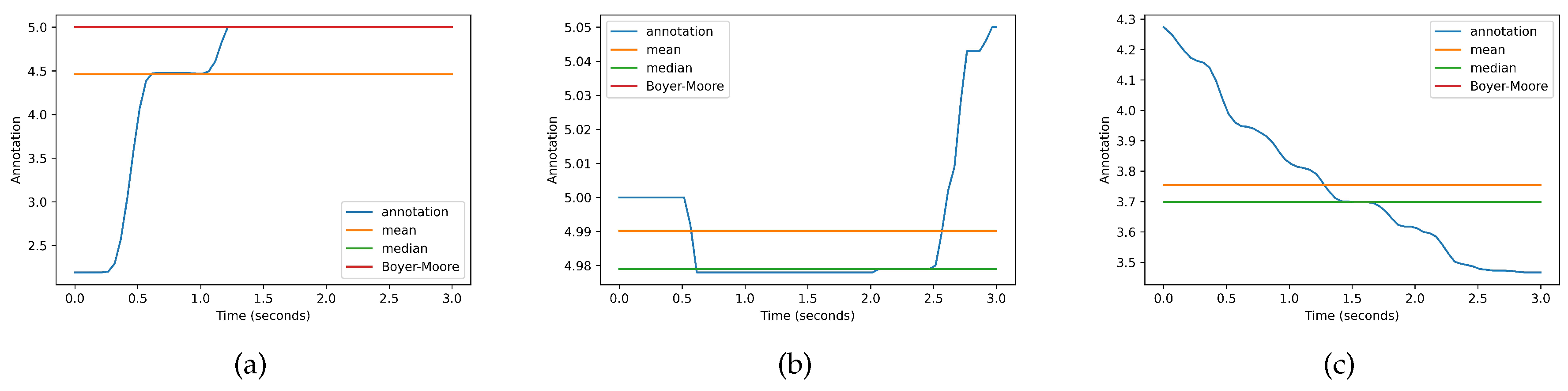

2.3. Labeling Schemes

2.4. Data Splitting

2.5. Feature Extraction

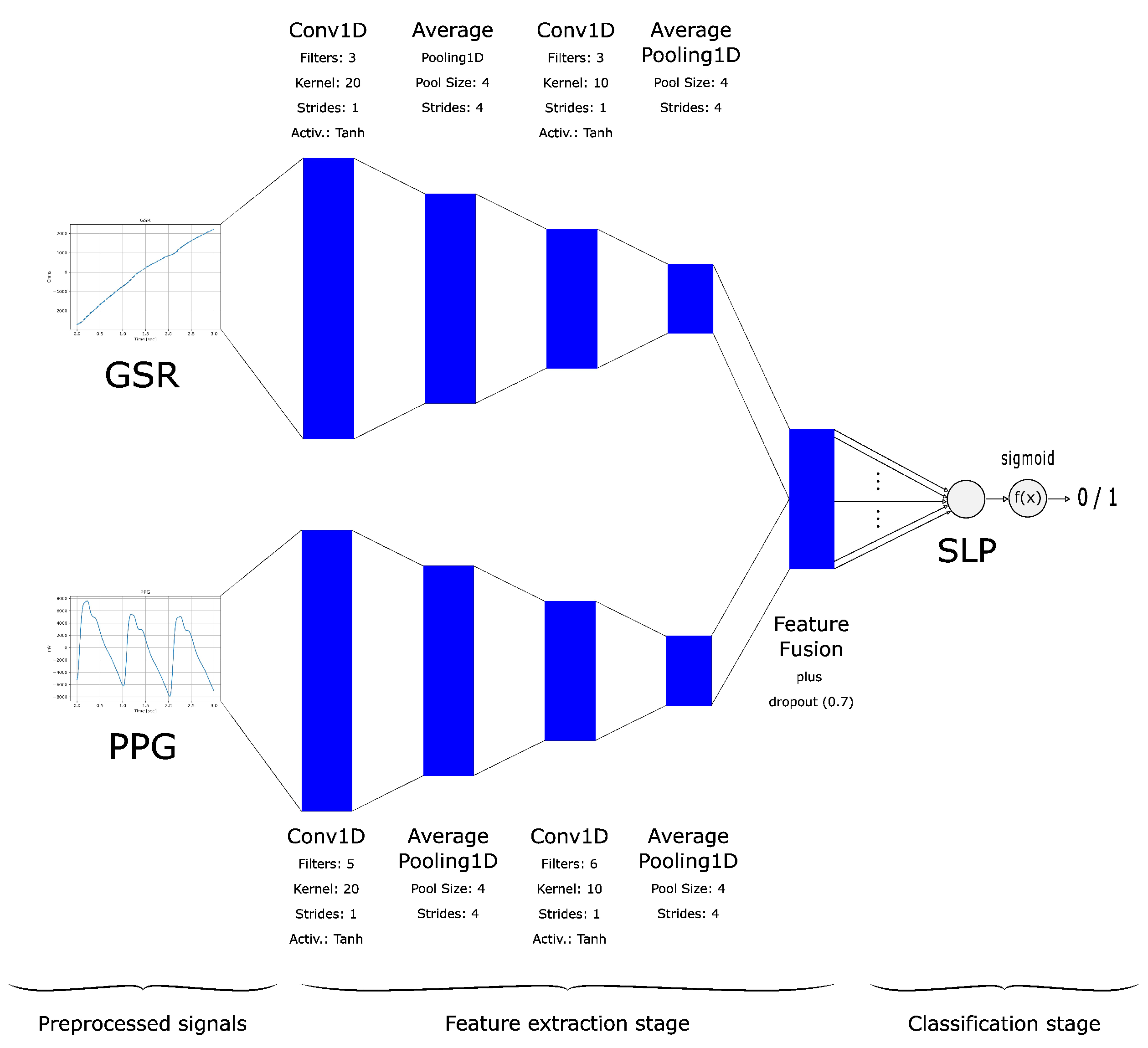

2.6. Algorithm Training and Performance Evaluation

2.7. Code Availability

3. Results

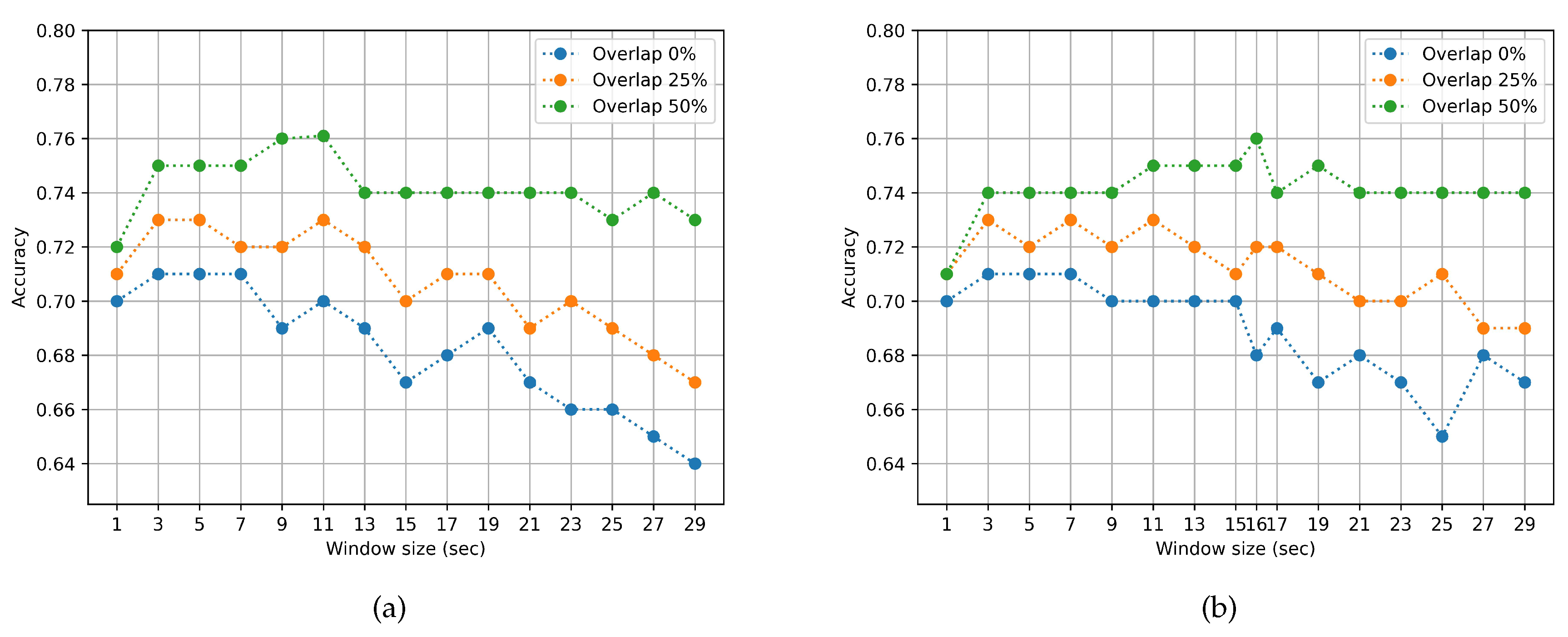

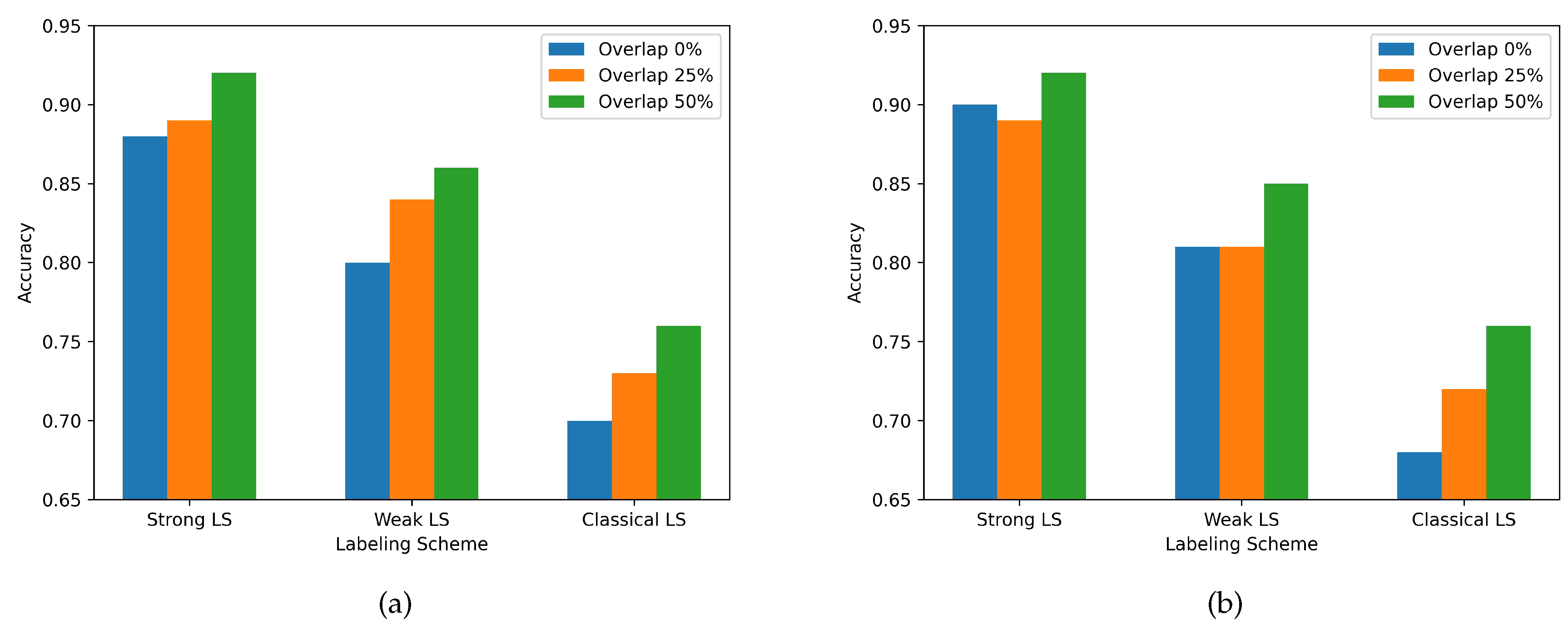

3.1. Impact of Window Duration Size and overlap

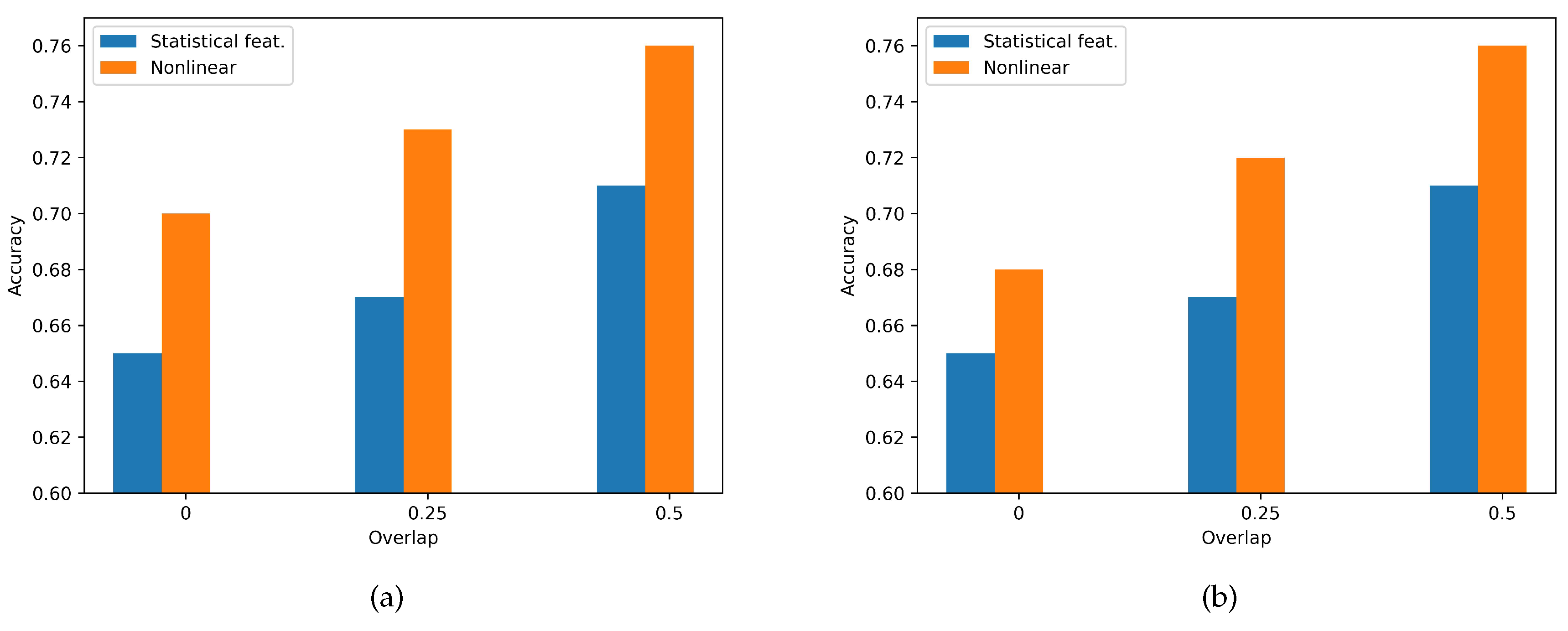

3.2. Features Domain Performance Comparison

3.3. Labeling Schemes comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

| Author | Modalities | Windowing / Overlap1 | Features2 | Classifier | Computational Cost | ACC3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goshvarpour et al. [16] | PPG, GSR | - | NL | PNN | High | A: V: |

| Martínez et al. [17] | PPG, GSR | W: Yes O: No | A | SCAE4 | High | <5 |

| Ayata et al. [18] | PPG, GSR | W: Yes O: Yes | ST | RF | Low | A: V: |

| Kang et al. [19] | PPG, GSR | W: Yes O: No | A | CNN | High | A: V: |

| Domínguez-Jiménez et al. [21] | PPG, GSR | W: Yes O: No | ST, NL6 | SVM | Low | 7 |

| Our previous work [22] | PPG, GSR | W: No O: No | TST | SVM | Low | A: V: 8 |

| Zitouni et al. [15] | PPG, GSR and HR | W: Yes O: Yes | ST, NL | LSTM | High | A: V: |

| Santamaría-Granados et al. [35] | ECG-GSR | W: Yes O: Yes | TST, F, NL | DCNN | High | A: V: |

| Cittadini et al. [36] | GSR, ECG, RESP | W: Yes O: No | TST | KNN | Low | A: V: |

| Zhang et al. [32] | PPG, GSR, ECG, HR | W: Yes O: No | A | CorrNet9 | High | A: V: |

| Present work | PPG, GSR | W: No O: Yes | NL | RF | Low | A: V: |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khare, S.K.; Blanes-Vidal, V.; Nadimi, E.S.; Acharya, U.R. Emotion recognition and artificial intelligence: A systematic review (2014–2023) and research recommendations. Inf. Fusion 2023, 102, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzedzickis, A.; Kaklauskas, A.; Bucinskas, V. Human emotion recognition: Review of sensors and methods. Sensors (Switzerland) 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bota, P.J.; Wang, C.; Fred, A.L.N.; Placido Da Silva, H. A Review, Current Challenges, and Future Possibilities on Emotion Recognition Using Machine Learning and Physiological Signals. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 140990–141020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, P.; Reiss, A.; Dürichen, R.; Laerhoven, K.V. Wearable-Based Affect Recognition—A Review. Sensors 2019, 19, 4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoli, L.; Martalò, M.; Cilfone, A.; Belli, L.; Ferrari, G.; Presta, R.; Montanari, R.; Mengoni, M.; Giraldi, L.; Amparore, E.G.; Botta, M.; Drago, I.; Carbonara, G.; Castellano, A.; Plomp, J. On driver behavior recognition for increased safety: A roadmap, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, N.; Pato, M.; Lourenço, A.R.; Datia, N. A Survey on Wearable Sensors for Mental Health Monitoring. Sensors (Basel). 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreibig, S.D. Autonomic nervous system activity in emotion: A review, 2010. [CrossRef]

- van Dooren, M.; de Vries, J.J.J.; Janssen, J.H. Emotional sweating across the body: Comparing 16 different skin conductance measurement locations. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 106, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, S.; Massimino, S.; Fallica, P.G.; Giacobbe, A.; Donato, N.; Coco, M.; Neri, G.; Parenti, R.; Perciavalle, V.; Conoci, S. Emotion Recognition: Photoplethysmography and Electrocardiography in Comparison. Biosensors 2022, 12, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, S.; Pan, J. Combining facial expressions and electroencephalography to enhance emotion recognition. Futur. Internet 2019, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelstra, S.; Mühl, C.; Soleymani, M.; Lee, J.S.; Yazdani, A.; Ebrahimi, T.; Pun, T.; Nijholt, A.; Patras, I. DEAP: A database for emotion analysis; Using physiological signals. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2012, 3, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Correa, J.A.; Abadi, M.K.; Sebe, N.; Patras, I. AMIGOS: A Dataset for Affect, Personality and Mood Research on Individuals and Groups. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2021, 12, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.Y.; Cha, N.; Kang, S.; Kim, A.; Khandoker, A.H.; Hadjileontiadis, L.; Oh, A.; Jeong, Y.; Lee, U. K-EmoCon, a multimodal sensor dataset for continuous emotion recognition in naturalistic conversations. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Castellini, C.; van den Broek, E.L.; Albu-Schaeffer, A.; Schwenker, F. A dataset of continuous affect annotations and physiological signals for emotion analysis. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 196–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitouni, M.S.; Park, C.Y.; Lee, U.; Hadjileontiadis, L.J.; Khandoker, A. LSTM-Modeling of Emotion Recognition Using Peripheral Physiological Signals in Naturalistic Conversations. IEEE J. Biomed. Heal. Informatics 2023, 27, 912–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goshvarpour, A.; Goshvarpour, A. The potential of photoplethysmogram and galvanic skin response in emotion recognition using nonlinear features. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2020, 43, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, H.P.; Bengio, Y.; Yannakakis, G. Learning deep physiological models of affect. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2013, 8, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayata, D.; Yaslan, Y.; Kamasak, M.E. Emotion Based Music Recommendation System Using Wearable Physiological Sensors. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2018, 64, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.H.; Kim, D.H. 1D Convolutional Autoencoder-Based PPG and GSR Signals for Real-Time Emotion Classification. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 91332–91345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeng, J.H.; Kang, D.H.; Kim, D.H. Deep Learning Method for Selecting Effective Models and Feature Groups in Emotion Recognition Using an Asian Multimodal Database. Electron. 2020, Vol. 9, Page 1988 2020, 9, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Jiménez, J.A.; Campo-Landines, K.C.; Martínez-Santos, J.C.; Delahoz, E.J.; Contreras-Ortiz, S.H. A machine learning model for emotion recognition from physiological signals. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2020, 55, 101646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamonte, M.F.; Risk, M.; Herrero, V. Emotion Recognition Based on Galvanic Skin Response and Photoplethysmography Signals Using Artificial Intelligence Algorithms. Advances in Bioengineering and Clinical Engineering; Ballina, F.E., Armentano, R., Acevedo, R.C., Meschino, G.J., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowski, D.; Pham, T.; Lau, Z.J.; Brammer, J.C.; Lespinasse, F.; Pham, H.; Schölzel, C.; Chen, S.H. NeuroKit2: A Python toolbox for neurophysiological signal processing. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 53, 1689–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, R.S.; Moore, J.S., MJRTY---A Fast Majority Vote Algorithm. In Automated Reasoning: Essays in Honor of Woody Bledsoe; Boyer, R.S., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1991; pp. 105--117 [CrossRef]

- Menezes, M.L.; Samara, A.; Galway, L.; Sant’Anna, A.; Verikas, A.; Alonso-Fernandez, F.; Wang, H.; Bond, R. Towards emotion recognition for virtual environments: an evaluation of eeg features on benchmark dataset. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2017, 21, 1003–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstein, M.T.; Collins, J.J.; De Luca, C.J. A practical method for calculating largest Lyapunov exponents from small data sets. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1993, 65, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, C.; Prost-Boucle, F.; Campagne, A.; Charbonnier, S.; Bonnet, S.; Vidal, A. Selection of the Most Relevant Physiological Features for Classifying Emotion. Proc. 2nd Int. Conf. Physiol. Comput. Syst., 2015, pp. 17–25. [CrossRef]

- van Gent, P.; Farah, H.; van Nes, N.; van Arem, B. Analysing noisy driver physiology real-time using off-the-shelf sensors: Heart rate analysis software from the taking the fast lane project. J. Open Res. Softw. 2019, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, V.; Seneviratne, S.; Rana, R.; Wen, E.; Kaluarachchi, T.; Nanayakkara, S. SigRep: Toward Robust Wearable Emotion Recognition with Contrastive Representation Learning. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 18105–18120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Moni, M.A.; Islam, M.M.; Rashed-Al-Mahfuz, M.; Islam, M.S.; Hasan, M.K.; Hossain, M.S.; Ahmad, M.; Uddin, S.; Azad, A.; Alyami, S.A.; Ahad, M.A.R.; Lio, P. Emotion Recognition from EEG Signal Focusing on Deep Learning and Shallow Learning Techniques. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 94601–94624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuller, B.; Vlasenko, B.; Eyben, F.; Wöllmer, M.; Stuhlsatz, A.; Wendemuth, A.; Rigoll, G. Cross-Corpus acoustic emotion recognition: Variances and strategies. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2010, 1, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ali, A.E.; Wang, C.; Hanjalic, A.; Cesar, P. Corrnet: Fine-grained emotion recognition for video watching using wearable physiological sensors. Sensors (Switzerland) 2021, 21, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saganowski, S.; Komoszyńska, J.; Behnke, M.; Perz, B.; Kunc, D.; Klich, B.; Kaczmarek. D.; Kazienko, P. Emognition dataset: emotion recognition with self-reports, facial expressions, and physiology using wearables. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bota, P.; Brito, J.; Fred, A.; Cesar, P.; Silva, H. A real-world dataset of group emotion experiences based on physiological data. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria-Granados, L.; Munoz-Organero, M.; Ramirez-Gonzalez, G.; Abdulhay, E.; Arunkumar, N. Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Emotion Detection on a Physiological Signals Dataset (AMIGOS). IEEE Access 2019, 7, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cittadini, R.; Tamantini, C.; Scotto di Luzio, F.; Lauretti, C.; Zollo, L.; Cordella, F. Affective state estimation based on Russell’s model and physiological measurements. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustos-López, M.; Cruz-Ramírez, N.; Guerra-Hernández, A.; Sánchez-Morales, L.N.; Cruz-Ramos, N.A.; Alor-Hernández, G. Wearables for Engagement Detection in Learning Environments: A Review. Biosens. 2022, Vol. 12, Page 509 2022, 12, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Classic labeling scheme | Weak labeling scheme | Strong labeling scheme |

|---|---|---|

| (CLS) | (WLS) | (SLS) |

| map | map | map |

| map | map | map |

| discard | discard |

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| LE | Lyapunov exponent (Rosenstein et al. method [26]) |

| ApEn | Approximate entropy |

| SD11 | Poincaré plot standard deviation perpendicular to the line of identity [9], for lag l1,Goshvarpour2020 |

| SD21 | Poincaré plot standard deviation along the identity line [9], for lag l1 |

| SD121 | Ratio of SD1-to-SD2, for lag l1 |

| S1 | Area of ellipse described by SD1 and SD2, for lag l1,Goshvarpour2020 |

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| GSR,Godin2015: | |

| Avgd | Average of the derivative |

| Negs | % of neg. samples in the derivative |

| Lm | number of local minima |

| PPG,Godin2015[28]: | |

| BPM | Beats per minute |

| IBI | Mean inter-beat interval |

| SDNN | Standard deviation of intervals between adjacent beats |

| RMSSD | Root mean square of successive differences between neighbouring heart beat intervals |

| SDSD | Standard deviation of successive differences between neighbouring heart beat intervals |

| Algorithm | Hyperparameters |

|---|---|

| KNN | neighbors = 5 |

| DT | criterion = gini |

| RF | estimators = 5 |

| SVM | regularization |

| GBM | estimators = 5 |

| CNN-SLP | See Figure 2 |

| Valence 1 | Arousal 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classifier | UAR | ACC | F1 | UAR | ACC | F1 |

| KNN | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.72 |

| DT | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.70 |

| RF | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.73 |

| SVM | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.56 |

| GBM | 0.68 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.74 | 0.68 |

| CNN-SLP | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.60 |

| Baseline | 0.50 | 0.61 | 0.37 | 0.5 | 0.59 | 0.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).