1. Introduction

Engineering design is challenging because it is far from static in a transition period from Industry 4.0 (I4.0) to Industry/Society 5.0, which focuses on the complete integration of technology to address social challenges and improve quality of life, along a phenomenon known as human-centricity [

1,

2]. Technological advances are permanently providing new alternatives and solutions, creating new problems or even full fields of study. The availability of technological alternatives also makes new products more complex than their previous generations. In this ever-evolving landscape of engineering, Systems Engineering stands as a critical discipline that coordinates the development of complex, multidisciplinary systems across diverse industries, in the time of Society 5.0 (a futuristic concept that advocates integrating technology into every aspect of daily life to improve quality of life) to benefit society [

3]. Systems Engineering has proposed a methodology that allows a systematic approach to developing systems that could involve multiple components from multiple domain expert teams [

4].

Among I4.0 technologies, robotic systems have been used in the last decade for risky duties such as ocean exploration [

5]. Within unmanned vehicles, one can find that Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) represent an example of systems that have evolved from simple to complex, according to the tasks that are expected to be executed. Initially developed for simple underwater tasks, ROVs have changed from maneuverable underwater camera systems [

6] to sophisticated platforms capable of performing intricate operations in deep water environments. Applications range from bomb recovery, search for lost submarines, and heavy-duty for the oil and gas industry [

6] to habitat monitoring and conservation [

7] and in-water hull cleaning [

8], among others.

The evolution of such underwater robotic systems has been driven by technological advances that extend their capabilities in harsh, unstructured environments [

6]. The integration of advanced sensory and autonomous navigation technologies has transformed ROVs from manually operated machines to intelligent systems capable of complex decision-making and operations [

9]. Current research in the field emphasizes the importance of integrating smart technologies to enhance the autonomy, efficiency, and user interface of ROVs [

10]. Some examples include simplifying operation [

11], visual-haptic feedback [

12], novel pilot interfaces for ROV operation [

13], or ROVs being launched and recovered from unmanned autonomous surface vessels [

14].

By focusing on smart technologies, we get into one pillar of this work: Industry 4.0. The concept of I4.0 is rooted in a history of industrial revolutions, each marked by breakthroughs that reshaped society, [

15]. From the steam engine to the use of electricity and the advent of computer technology, each phase has set the stage for the next [

16]. Industry 4.0 has built on these advances to introduce a new age of automation and data exchange in manufacturing technologies, setting new standards for productivity, and fostering an environment of continuous improvement and connectivity. Industry 4.0 is characterized by a fusion of technologies that blur the lines between physical, digital, and biological spheres, heavily relying on advances such as the Internet of Things (IoT), Big Data, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and Machine Learning (ML) [

17,

18].

The synergy between traditional engineering practices and revolutionary digital technologies is imperative nowadays. This is the key to significantly improving efficiency and innovation in manufacturing, data management, and system operation [

19]. However, the challenge remains in effectively integrating these next-generation technologies to enhance operational effectiveness without compromising reliability or increasing complexity undesirably [

20]. An additional challenge for engineers and designers is to avoid using the latest technology just for the sake of it and remain focused on solving the actual needs of users [

21]. The user requirements and functional-oriented Systems Engineering framework are ideal for integrating mature and new technologies into robust solutions while supporting a user-centered design approach.

There is literature on the relationship between robotics and Industry 4.0 [

22,

23] and on Systems Engineering and robotics [

24,

25,

26]. Additionally, works detail ROV development and design from components and specifics perspectives [

27,

28,

29]. However, while I4.0 may not seem closely related to ROVs, there are improvement opportunities that can be approached with I4.0 tools.

This work presents a novel integration of I4.0 concepts and Systems Engineering methodologies in the context of designing an underwater robotic system. Through a case study, this research introduces the development of an underwater exploration vehicle using Systems Engineering tools, starting from stakeholder identification and requirements definition to presenting a logical decomposition of the exploration system.

The novelty of this approach lies in the emphasis on requirements and functions closely related to I4.0 solutions. By viewing I4.0 from a functional standpoint, this work facilitates its connection with Systems Engineering methodologies, providing a new perspective on the application of I4.0 tools to advanced robotics. This integration serves as a reference for applying Systems Engineering to the domain of advanced robotics under I4.0, illustrating its potential to streamline the integration of cutting-edge technologies into complex systems.

Additionally, the structured analysis and design approach provided in this study aims to serve as a blueprint for future developments in robotic systems and other complex engineering projects within the scope of migrating from I4.0 to Industry/Society 5.0.

The organization of the paper is as follows.

Section 2 provides the concepts of SE and describes the design process for complex systems.

Section 3 describes the technologies of I4.0 and emphasizes the present and future requirements of human-centricity for the implementation of such technologies.

Section 4 summarizes the main characteristics that allow a remotely operated underwater robot to be considered a complex system.

Section 5 presents the case study for the conceptual design of an underwater robotic system using the SE approach. Finally,

Section 6 contains the discussion, and

Section 7 presents the main conclusions.

2. Systems Engineering

A technical system is defined as “a set of components working together as a whole to achieve a common objective” [

30]. These systems operate within an environment where they interact and produce mutual effects. However, several characteristics distinguish a complex system from a simpler system [

30]. The first one is that it is a product of engineering and therefore meets specific needs. The second is that it consists of various components that have intricate relationships between them and is therefore multidisciplinary and relatively complex. And the final one is that it uses advanced technology in ways that are central to the performance and fulfillment of its primary functions, which involves taking risks during development and often high costs.

The concept of Systems Engineering and its applications emerged in the early 1950s, although it has been promoted by the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) since the 1990s as an engineering discipline of systems design [

31]. It aims to work with all engineering disciplines (mechanics, hydraulics, electronics, sensors, control, etc.) to develop comprehensive solutions that meet the functional, physical, and operational performance requirements of customers and stakeholders [

4,

30].

The roles of systems engineering are to allocate the system’s functions in the appropriate engineering domain, to coordinate those functions, to define the interfaces between functions, and to distribute design tasks, among others [

32]. NASA defines Systems Engineering as the practice of balancing organizational, cost, and technical interactions within complex systems [

33].

Systems Engineering spans the project life cycle from the initial idea to develop a functional device that meets the user’s needs. Important product features that are considered in this discipline are product function, costs, schedule, user support, quality, manufacturing, and phase-out [

32,

33]. Additionally, a crucial process in Systems Engineering is to model the system from a functional perspective, which facilitates decision-making in the design process. This involves decomposing the system into manageable subsystems and ensuring continuous integration across domains [

32].

Systems Engineering follows a sequential process, typically starting with the formulation of the objective and strategic planning. Followed by requirements development, architectural design, and component development [

34,

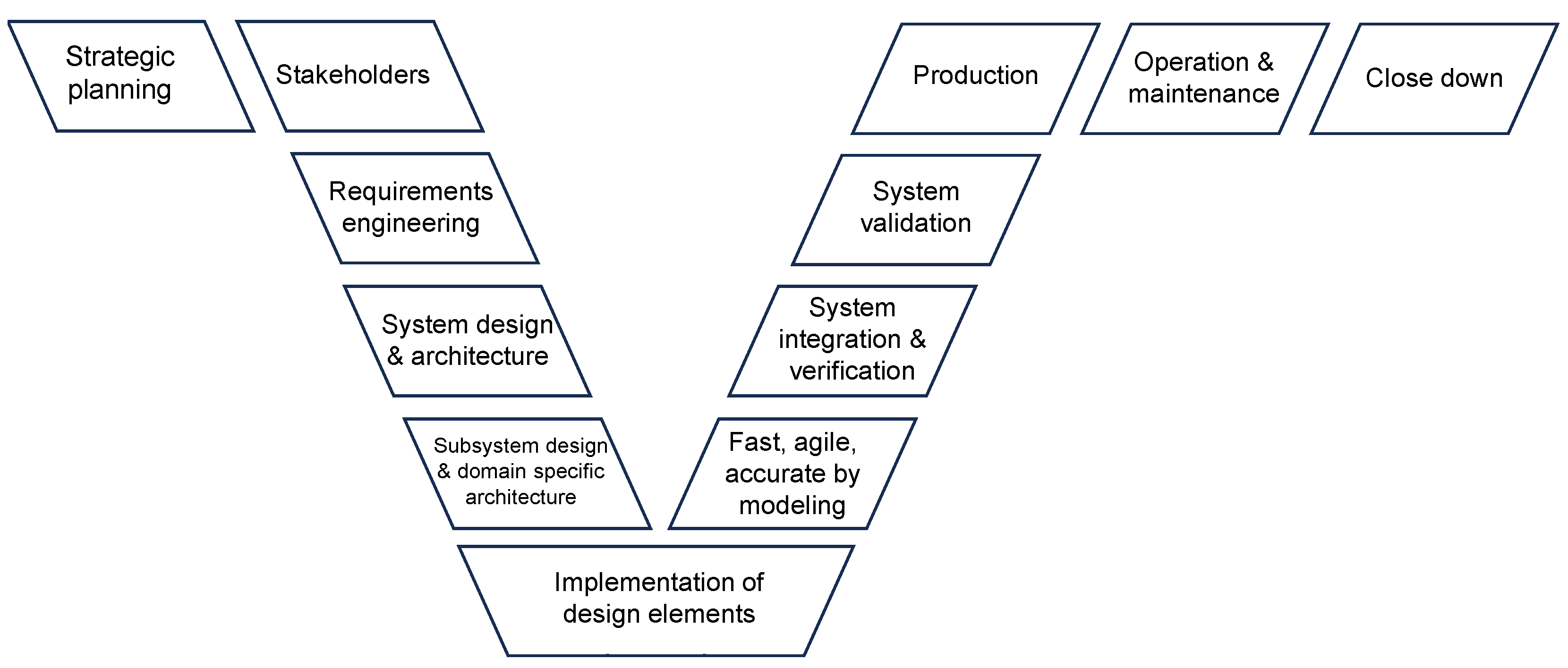

35]. This process is illustrated in

Figure 1. Systems Engineering starts understanding the global problem, and then progressively decomposes the system into subsystems and components. This process is known as the “top-down approach” in the analysis of needs and requirements. It starts with functional thinking (logical decomposition and functional architecture) and gradually transitions to physical thinking (physical architecture). Following this, a bottom-up approach is employed for the implementation of physical solutions and their actual integration. The process concludes with a comprehensive final evaluation of the physical system [

33]. SE is also defined as an iterative process where each step relies on the previous one, but that previous one can receive feedback by subsequent steps [

32].

NASA’s Systems Engineering handbook describes SE including three different groups of technical processes: system design, product realization, and technical management [

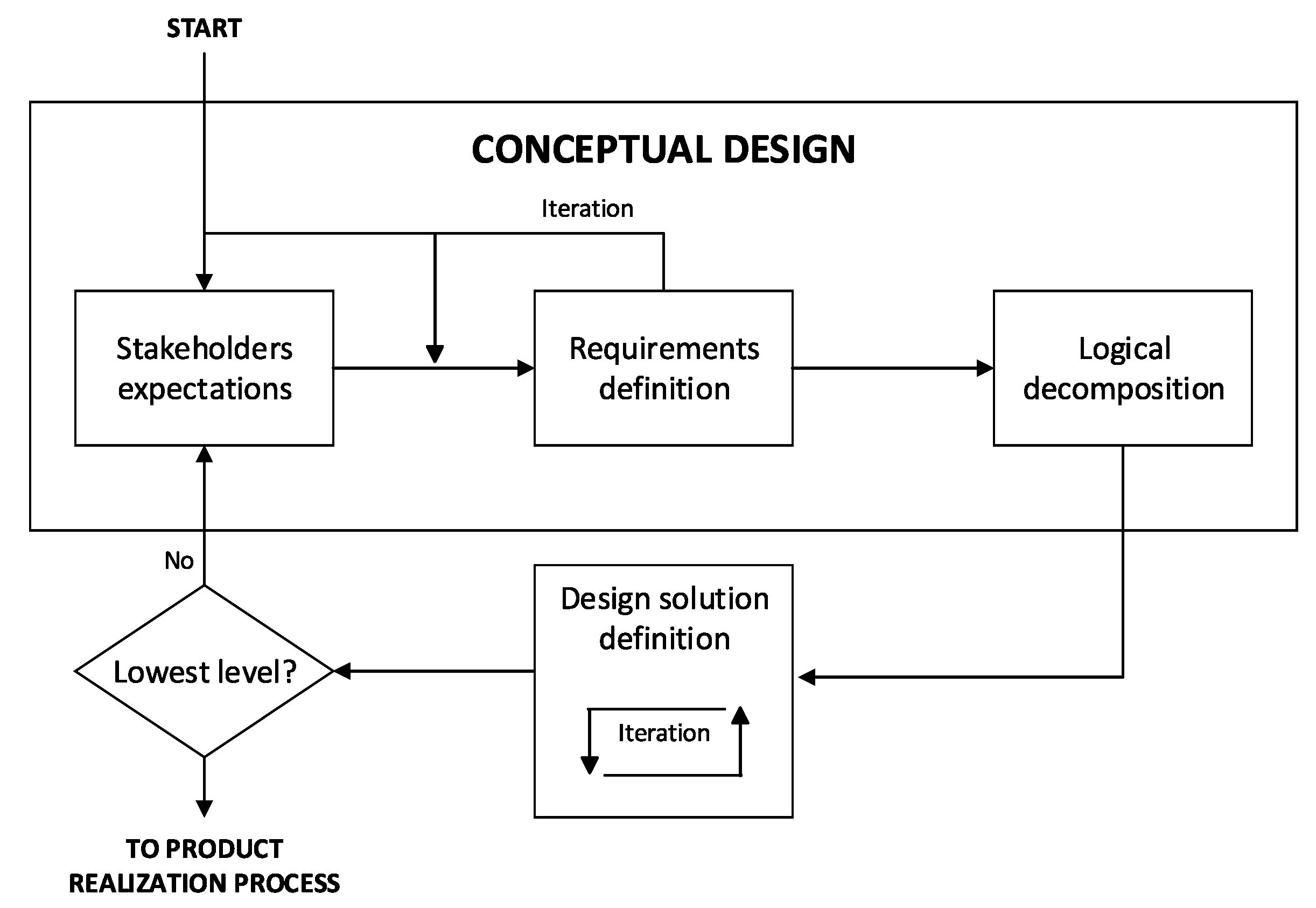

33]. Focusing on system design (see

Figure 2), this process encompasses defining stakeholder expectations, generating technical requirements, translating these into logical models, and designing solutions that meet these expectations [

30,

33,

34].

Figure 2 also illustrates how the three first steps could be related to conceptual design. Conceptual design starts with a needs statement, followed by a context study, requirements engineering, and a state-of-the-art review. The system is visualized as a whole, and functions, sub-functions, and functional groups are proposed. The conceptual design stage is critical as it sets the direction for all subsequent efforts [

33].

The following design stage aims to transition from the problem domain to the solution domain. This is also known as the design solution definition. In this stage, the functional architecture must be transformed into a physical architecture, and subsystems are established. This could be related to embodiment and detailed design in other representations of the design process. Low-resolution prototypes of individual elements and subsystems are used. Decisions are made based on requirements criteria, with the objective of proposing a physical configuration of the solution with preliminary values. In this system design stage, various disciplines develop the solution for each subsystem. Detailed calculations, tests, and increasingly integrated high-resolution prototypes are prioritized. System specifications are obtained, and a general design review is conducted.

Construction or production (product realization) aims to produce the components according to the obtained specifications. This involves the construction and testing of the system. Once constructed, formal qualification reviews and evaluation and acceptance tests are performed. Like any design process, these stages have iterative and recurring components. It should also be understood that in practice, the boundaries between stages are blurred, and the exact methods to be used may vary from one project to another.

The system project must be developed under consistent technical planning, technical control, technical assessment, and technical decision analysis processes. It allows project traceability from requirement, configuration, and technical management through technical assessment and risk management [

33].

Finally, SE emphasizes a User-Centered Design (UCD) approach, prioritizing end-user needs and feedback throughout the design and development process. By integrating user requirements into system specifications, the goal is to create products, systems, or services that are not only effective and efficient but also satisfying for the user [

36,

37]. Integrating user requirements into the overall system requirements ensures that technical specifications align with user expectations.

3. Industry 4.0

The fourth industrial revolution, known as Industry 4.0 (I4.0), is revolutionizing market competitiveness through the adoption of innovative processes. These processes incorporate digital technologies, automation, and data-driven decision-making, establishing new paradigms in production, consumption, and interaction with the world [

17,

18]. The concept of I4.0 was initially proposed in Germany in the early 2010s, defined to create smart and interconnected companies [

38]. These companies leverage cyber-physical systems to optimize processes by integrating sensing, computation, control, and networking into physical objects and infrastructure, connecting them to the internet and each other [

39].

To understand the concept of an industrial revolution, it is necessary to define the previous ones as periods where big economic, social, and economic changes and transitions in industrial processes and manufacturing occurred, using innovative technologies [

40]. In the first industrial revolution, the steam machine was introduced (1760-1840), followed by the discovery and adoption of electric energy, the assembly line, and massive production in the second one (1870-1930). During the third one, electronic devices, computation, and automation were globally adopted (1950-2000s) [

16].

Industry 4.0 is characterized by the use of the Internet of Things (IoT), Big Data, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and Machine Learning (ML), as well as other technologies, some of them summarized and related to their functionalities in

Table 1. These technologies facilitate the extensive availability of data via an internet connection. They enable a deeper understanding of industrial and consumer behaviors through data analysis. This, in turn, supports learning from experience, modeling, and predicting phenomena [

17].

IoT plays a key role in I4.0, connecting physical objects, devices, and systems to the internet, aiming to receive and transmit data through wireless networks, to process them and subsequently report the object status or perform an activity without any human operation [

17]. Functionally describing IoT, it enables the connection of physical devices and objects to the internet, allowing them to collect and exchange data. In the industrial context, this means that machines, sensors, and other equipment can communicate with each other in real time.

This process is strongly related to Big Data, as the large amount of data generated by IoT needs to be analyzed to derive insights and understand the systems’ behavior. Big data analytics involves the processing and analysis of large volumes of data to derive meaningful insights [

50]. In Industry 4.0, this tool helps in making data-driven decisions, predicting equipment failures, optimizing processes, and improving overall efficiency. Subsequently, AI and ML algorithms are employed to analyze data, recognize patterns, and make autonomous decisions, contributing to the smart side of Industry 4.0 [

41].

An important concept that defines a scalable and accessible platform for storing and processing large amounts of data is Cloud Computing. I4.0 facilitates the centralized storage of large datasets, collaborative work, and remote access to resources [

64].

Advanced robotic technologies are also important in I4.0, they are systems capable of cognition, navigation, mobility, and complex interactions [

65]. Robots equipped with AI and sensors can perform tasks autonomously. In many industrial applications, these robots can handle repetitive or dangerous tasks, improving efficiency and workplace safety. They are meant to perform complex jobs in hostile environments, data extraction, enhance productivity and reliability, automate processes, and carry out inspections and surveillance, among other tasks [

23]. In this way, the robotic systems are strongly linked with I4.0 elements, as they employ technological elements such as digitization, automation, and connectivity [

22].

Integration of IoT in robotic systems implies using sensors that allow collecting and transmitting data to adapt themselves to changing conditions and work collaboratively with human workers and other machines, as they could generate enough amounts of data to ease data-driven decision making, as well as allow remote monitoring and control [

22,

44,

66]. IoT capabilities in robotic systems can provide valuable data for predictive maintenance, quality control, and process optimization. In terms of surveillance activities, equipping robots with vision, imaging systems, and AI, leads to important inspection tasks that empower the robot to make its own decisions or wait for an operator’s instruction. Robots are important in driving the Industry 4.0 pillars of automation, data-driven decision-making, and connectivity.

It is important to recognize I4.0 from the point of view of its contribution to solving people’s problems and not because of its technologies as such. One way to do this is to understand technologies from the functions or tasks that they can perform. It allows them to be connected with functional and systemic thinking that helps develop new user-centered solutions based on the best available technologies or reach these solutions by adapting technologies from their functionality. That is a key aspect of the exercise shown in

Table 1.

4. Remotely Operated Vehicles

A robot is generally defined as a machine or mechanical device engineered to execute tasks autonomously or with minimal human intervention [

67]. Robots usually include a physical structure, actuators for movement, sensors for perception, and a control system governed by computer programs [

68]. The primary objective of physical robots is to execute specific functions, often in environments where human intervention may be impractical, unsafe, or where high precision and efficiency are required [

69,

70]. Robots come in various forms, ranging from industrial robotic arms to mobile robots [

71,

72]. They find applications in logistics, industrial manufacturing, defense and security, space, land, and underwater exploration [

46,

73].

Within the domain of mobile robotics, we distinguish between remotely operated and fully autonomous devices. This category includes Unmanned Ground Vehicles (UGVs) and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles/Systems (UAVs/UAS) for terrestrial and aerial operations, respectively. In aquatic settings, developments include Autonomous Surface Vehicles (ASVs) which are essentially robotic boats, along with Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) and Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs). ROVs are defined as unmanned remotely controlled submersible vehicles [

6] that operate in underwater missions such as ocean exploration, offshore inspections, scientific research, deep-sea archaeology, and underwater maintenance. These vehicles are typically equipped with cameras, sensors, and in some cases mechanical arms for tasks such as collecting samples or performing maintenance, for multiple hours, in depths up to 6000 m [

9,

10].

The development of ROVs can be traced back to the first exploration prototype in the 1950s and naval applications in the 1960s [

11]; by the 1970s, the oil and gas industries were responsible for developing and taking advantage of this technology. Although traditionally linked to military and oil industry applications [

74], their use has been extended to biological monitoring applications [

75], and the renewable energy industry [

76].

According to the NORSOK U-102 standard [

77], ROVs are classified into five different classes. Class I, for observation, is typically equipped with a video camera, lights, and propellers; Class II, for observation with additional load capacity, equipped with at least two additional sensors; Class III, for working, with sufficient capacity to load additional sensors and actuators to manipulate objects; Class IV, for work on the seabed, with wheels or other means of traction; and Class V, prototypes and other vehicles in the development phase. They dictate how the size and requirements are defined, and determine the capabilities and systems that should be integrated to get to the design objective.

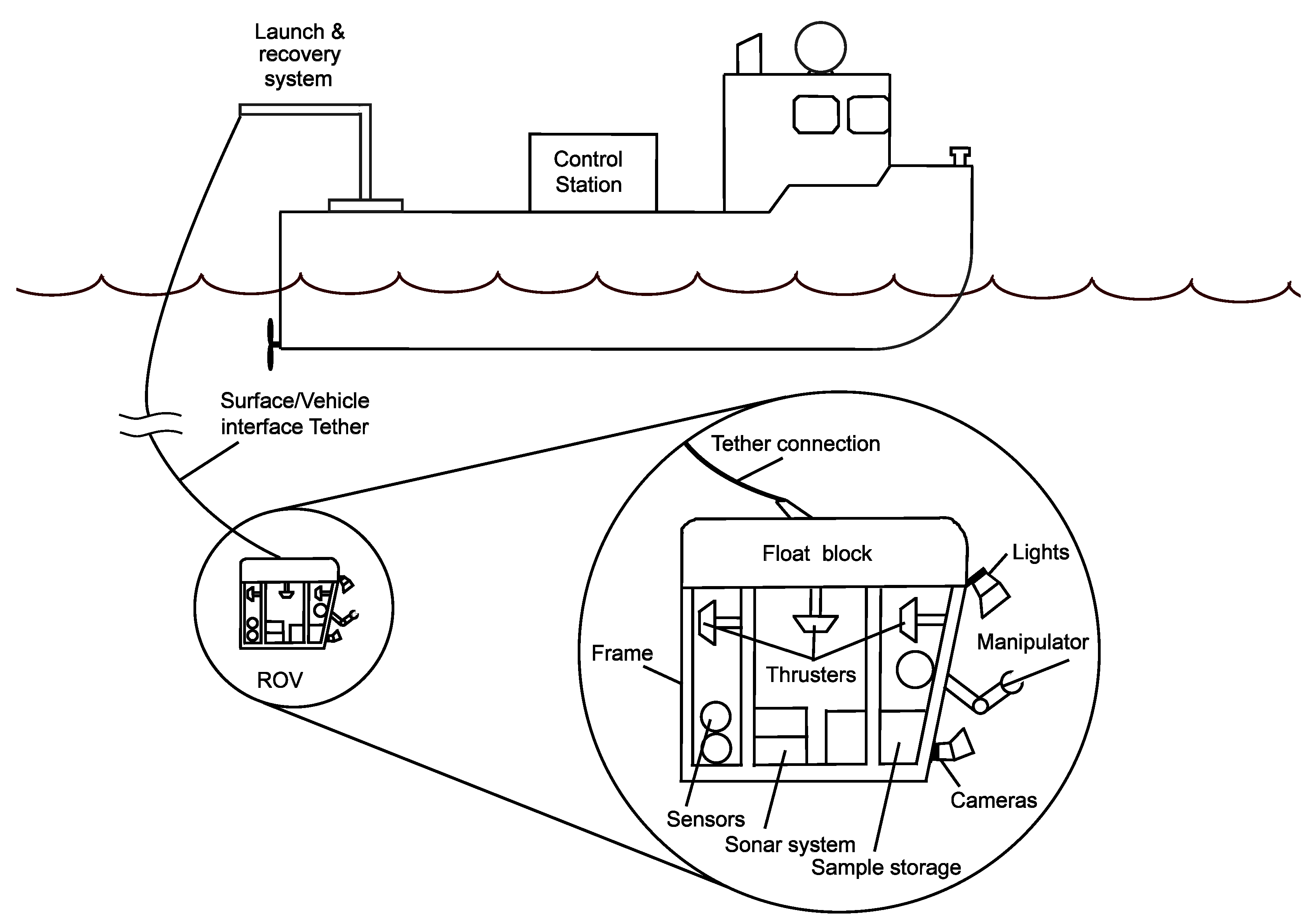

An ROV can be described in terms of a set of components [

28]: vehicle, surface station, surface/vehicle interface, control, and software. The vehicle itself is in charge of carrying out underwater tasks. The surface station provides an interface with the operator and contains the mechanical and power infrastructure required on the surface for the vehicle and other subsystems to operate. The surface/vehicle interface, also known as the Tether or Umbilical, allows the connection between the vehicle and the surface station. The control system is transversal to all subsystems and is in charge of the algorithms that give intelligence to the ROV system. The software is also transversal to all subsystems and provides the computing infrastructure that allows communications, capture, management, and processing of information, and vehicle control. This is an example of a components-centered description.

An ROV system is illustrated in

Figure 3. The surface side shows the surface control station and the launch and recovery system. There is a surface/vehicle interface or tether cable. Underwater side the ROV presents the frame, float block, thrusters, and the tether cable connection. There is also a variety of other components which may change on specific models. Some of the usual components are cameras, lights, sensors, and sonar systems. ROVs in Classes III and IV usually include manipulators and other tools.

An ROV is a complex system given its sub-system interactions. Although there are some components available off the shelf, their integration into a system is a complex task, leading to the need for multiple iterations and an interdisciplinary work team to accomplish its design process, requiring different basic disciplines that make up robotics: mechanics, electronics, control, and computing.

Despite being a mature technology, numerous recent efforts can currently be found to improve its navigation capabilities and levels of autonomy [

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83], as well as its monitoring capabilities through the implementation of different measurement equipment [

84,

85]. The requirements specified for the design of an underwater exploration system typically include: vehicle class, operating environment, operating depth, required degrees of freedom, weight and maximum dimensions, communications technology, navigation instruments, and auxiliary systems, among others [

28].

5. Case Study: Conceptual Design of an Underwater Exploration System

As stated before, conceptual design is the most important stage of the process because it establishes the foundation and direction for the subsequent work [

33]. This case study begins with a request from an undisclosed company for an experimental robotic system to support oceanic exploration activities. The approach follows the steps depicted in

Figure 2: Stakeholder Expectations, Requirements Definition, and Logical Decomposition.

5.1. Stakeholder Expectations

For Systems Engineering, stakeholders are fundamental elements in the system development process. The stakeholders of a system are those individuals who have the right to influence the requirements because they will be affected (positively or negatively) by the system under development. In this case study stakeholders were identified in five groups: i) the company managers who approved the budget and execution of the design project, ii) professionals (engineers and geologists) who raised the technical requirements, iii) the operational personnel who are responsible for the operation of equipment, iv) the personnel in charge of analyzing the information obtained by the system, and v) the personnel of the platform from which the system will be operated (ship, oil/gas platform, dock, etc.).

Different activities have to be performed with stakeholders to identify and define their expectations. Such expectations include needs, goals, objectives, constraints, and success criteria. For this case study the summary of stakeholders’ expectations are given as follows:

The Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) is an experimental observation system designed for underwater exploration in the ocean, up to 500 m deep. Its main functions include capturing high-quality images and video of the sea floor and collecting solid and liquid samples.

The ROV is compact and lightweight, with a mass between 100 to 300 kilograms. It features a video system able to capture and display multiple videos simultaneously, instead of having to switch between cameras. It also includes multiple power and data connections, and a lighting system adapted for underwater conditions. The design emphasizes minimal power consumption and high-speed data transmission.

The ROV is targeted at markets involved in hydrocarbon exploration and marine scientific studies. Its data transmission capabilities are enhanced with the potential for real-time data, depending on the availability and mission-specific requirements. The design ensures easy operability with minimal personnel, and its sample collection capacities are optimized within the vehicle’s physical limitations.

Note that this is a summary; behind every statement, there is a lot of information and analysis. For example, an expected weight between 100 to 300 kilograms has implications related to logistics, transportation, operative costs, crew size, safety, and so on.

5.2. Requirements Definition

A requirement is a fundamental concept for SE. It is the result of a formal transformation of one or more needs into an obligation of an entity to perform a certain function or possess a certain quality, given certain constraints. In SE, a set of clear, complete requirements that do not interfere with each other must be obtained. There should also be an understanding of the required functionalities, priorities, and costs, as well as the management of requirement changes that may arise throughout the process [

34].

Requirements engineering seeks to consolidate needs and requirements that will guide the system’s development. Requirements are important because they help establish the scope, allow all stakeholders to have a voice, justify development costs, accurately report progress, and determine when the project has successfully concluded [

34].

Several user requirements can be identified within an underwater exploration ROV project. Some of them are strongly related to the utilization of Industry 4.0 technologies, which are used among the whole system.

Table 2 shows a summary of user requirements, with each definition expressed following the Easy Approach to Requirements Syntax (EARS) proposed by Mavin et al. [

86]. This methodology is characterized by helping to generate a concrete and sufficiently technical redaction to the requirements. This avoids overly vague or excessively complex writings. Once requirements are properly stated, they are presented to stakeholders so they approve the list. Finally, it is important to have requirements prioritized. Stakeholders establish requirements priority by giving them a punctuation (1 to 5). This is also shown on

Table 2.

Requirements can be classified in several ways. One classification includes customer requirements, functional requirements, performance requirements, and design requirements. Two strategies can be used to consolidate requirements: elicitation and elaboration. Elicitation is achieved explicitly and directly from stakeholders through strategies such as interviews and workshops. Elaboration involves obtaining requirements that are not explicitly proposed by stakeholders but are derived from the study of the context, the technology of other requirements, etc. [

87]. “Bad requirements cannot be fixed by good design” [

34,

88], summarizes the importance of requirements engineering and conceptual design. Requirements are also key inputs when conducting a selection process to acquire a commercially available system (or technology) ready for operation.

5.2.1. Quality Function Deployment - House of Quality

Requirements are often processed to obtain technical criteria that allow for decision-making later in the design process. Techniques such as the House of Quality (HoQ) can be applied at this stage [

88,

89,

90,

91]. HoQ is just the first of four matrices included in the Quality Function Deployment (QFD) method. These matrices span the whole product development cycle. However, in the conceptual design stage, only the first matrix of the QFD is created, i.e., the HoQ.

The first step in the HoQ process involves defining the requirements, as illustrated in

Table 2 and discussed in

Section 5.2. It is also crucial to have users assign priority scores to these requirements to ensure their importance is accurately reflected.

The second step involves translating user requirements into Engineering Characteristics (EC). These are defined in terms of controllable attributes by the design team. While these technical requirements do not dictate specific solutions; they should be articulated as measurable or quantifiable specifications [

92].

Thirdly, the HoQ exercise for the ROV system is carried out as detailed in

Table 3, adhering to established HoQ guidelines [

88,

93]. In this exercise, the relationship between user requirements and engineering characteristics is evaluated and assigned scores of 0 (no relation), 1 (weak relation), 3 (moderate relation), or 9 (strong relation). These scores, combined with the prioritization of user requirements, facilitate the ranking of engineering characteristics.

This ranking is of great importance, serving as a guide for decision-making since it identifies which characteristics are most critical to address, taking into account potential conflicts or resource limitations. Consequently, this process highlights the most crucial engineering characteristics of the underwater exploration system, with data transmission speed, video resolution, image resolution, and storage autonomy emerging as the top priorities among the 13 evaluated technical requirements.

5.3. Logical decomposition

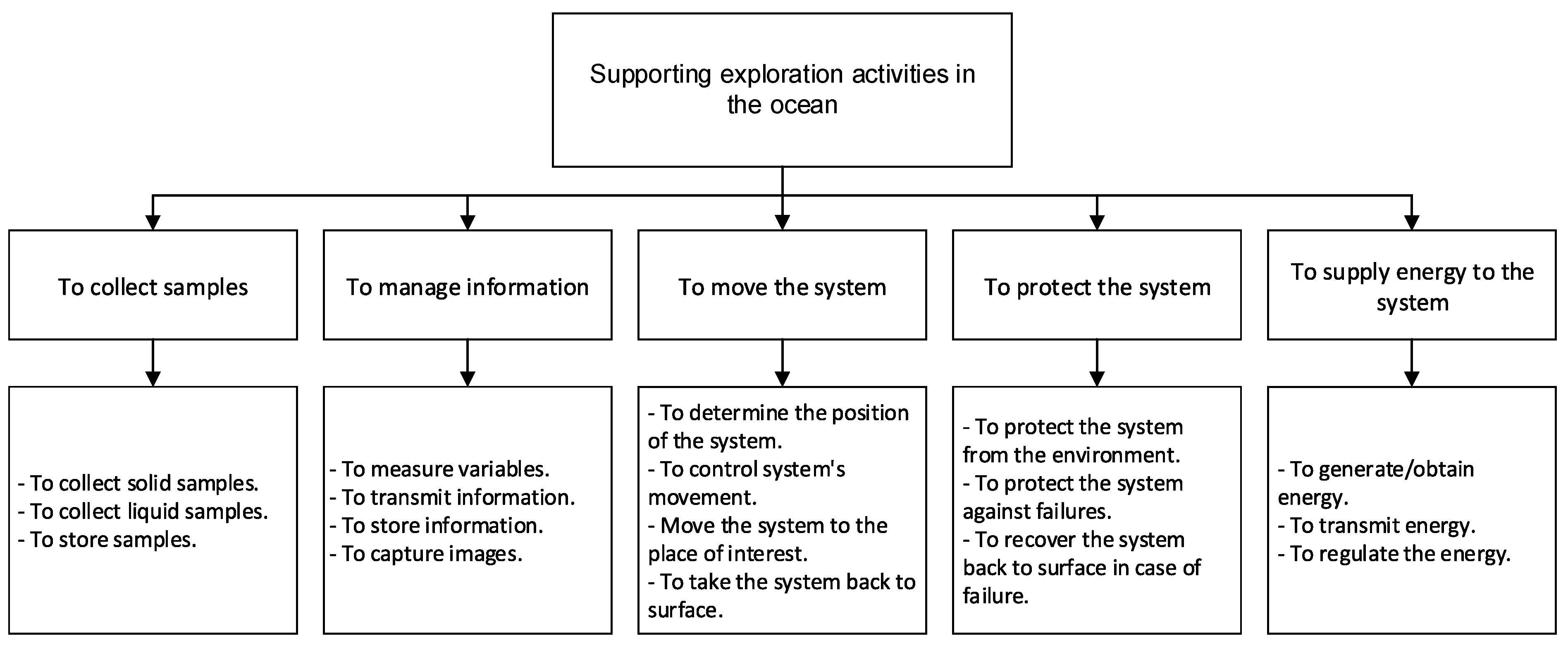

The logical decomposition requires to understand the system to be designed in terms of the tasks or functions the system will perform. The main function of the ROV system in the case study is to collect images and samples in the ocean at depths of up to 500 meters. To achieve this function, several support functions must be defined and accomplished. A logical decomposition for the ROV is shown in

Figure 4. To create this simplified representation, functional groups are defined and lower-level support functions are included in each group. This simplification presents the following five functional groups.

To collect physical samples. This functional group is responsible for collecting and storing water samples as well as solid samples. As in any other complex system, this function is not isolated and depends on the fulfillment of other functions to achieve its goals. It highlights the interdependent nature of system functions, relying on precise movement and data management to successfully collect and catalog samples.

To manage information. This function deals with all the data sent from the control room to the robot. It also manages the data generated from sensors and components and brings them to the surface. Data needs to be collected, transmitted, classified, stored, and retrieved. From the point of view of I4.0, this functional group would be the heart of the system.

To move the system. No meaningful sample or data can be obtained if the ROV is not located in the desired exploration area. This functional group deals with tasks related to bringing the robot into the water as well as moving the robot through the water until it reaches the place where samples are going to be taken and back to the surface/support vessel. Determining ROV position and orientation is also a task of this functional group.

To protect the system. An ROV has interactions with other systems (support vessel, launch and recovery system, etc.) and with the environment (water, waves, currents, reefs, rocks, sand, etc). There are also internal failures that need to be addressed. Active and passive protection must be performed from possible damages. This functional group includes: protecting against failures, protecting from the environment, and recovering procedures if something fails.

To supply energy. Powering the ROV’s mission, this function deals with the generation, regulation, and distribution of energy to various components. Given the diverse energy needs of the ROV’s systems (from propulsion to sensors), this group is tasked with ensuring a reliable energy supply under varying operational conditions, addressing challenges such as energy efficiency and the distribution of power to optimize mission duration and capability.

The functional groups in

Figure 4, and their supporting functions are not standalone; they are interconnected, illustrating the ROV’s system complexity and the need for an integrated approach to its design and operation. This decomposition not only aids in understanding the system’s operational framework but also sets the stage for identifying technical requirements and addressing design challenges. In this case guided by the principles of I4.0 for a smarter, interconnected solution.

5.3.1. Example: Logical Decomposition for a Lower Level Functional Group

The functional group in charge of managing data would be the backbone of an ROV.

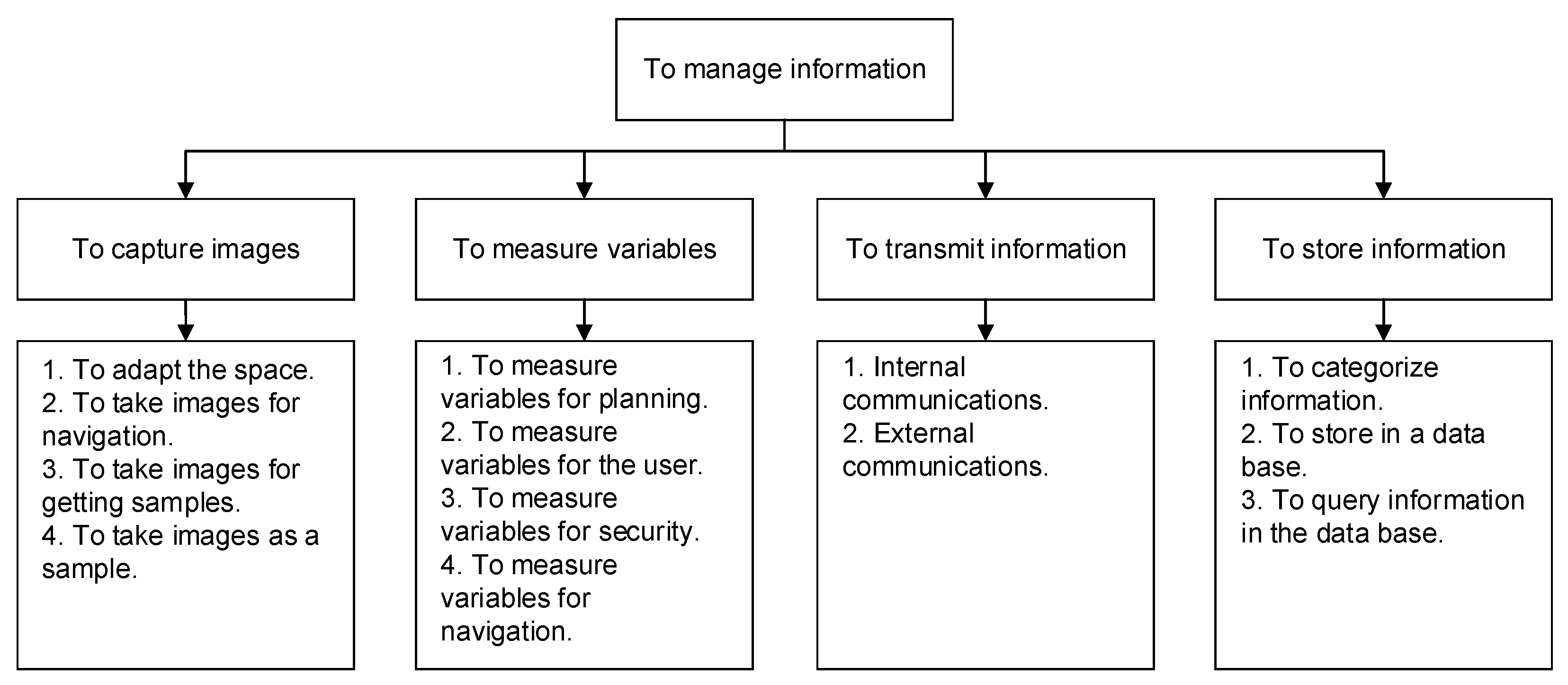

Figure 5 presents the specific functional decomposition of the functional group

to manage information. By making this decomposition, the support functions that take the system closer to the main objective are properly identified. It means, which tasks or functions are needed for the ROV system to capture images, measure variables, transmit information, and store it.

As seen in

Figure 5, the

manage information functional group is decomposed into four lower-level groups. The following brief descriptions are helpful for further conceptual analysis.

-

To capture images. For this case study, images refer to both pictures and video. Images are used in several ways in ROVs. They are the main input for pilots to decide how to navigate, hence, human controllers require quality images. Images are also important to decide where to take a physical sample or which sample should be taken, in case the ROV is equipped to do so.

For exploration missions, pictures and videos themselves are the samples and after being captured they will be analyzed by specialists. For instance, if studying biodiversity in some ocean area, biologists will analyze images in order to identify and catalog what was recorded.

Finally, no image will be recorded if there is not adequate lighting. Beyond a 100-meter depth sunlight is completely absorbed, so ROV systems need a way to adapt the environment for cameras to work.

-

To measure variables. As well as with images, variables are used for several purposes. There are some variables from the vehicle and from external sources required to make decisions regarding whether or not to do an immersion or other mission planning (ie: current speed, tides, weather, underwater visibility, etc). Other variables are associated to samples; for instance, water temperature, dissolved oxygen (with the corresponding depth), and coordinates where the values were recorded.

Safety variables are information collected in order to monitor the vehicle itself and its surroundings in order to avoid risks or to take action in case of damage or accidents. For example, not only the ROV’s depth is important but also distance from the bottom, and monitoring if there is humidity inside sealed cases with electronics. The circuit’s current and temperature are also monitored, etc. Pilots need to be checking on these values or checking on alarms in order to take proper actions.

Finally, while pilots rely mostly on real-time video to navigate, other variables may be helpful as well. For example, distance from the bottom is important to avoid colliding. ROV coordinates relative to the surface platform are required as feedback when trying to reach a specific location with the underwater vehicle.

To transmit information. Information is collected both underwater and in the surface station, and such information is required in both sides of the system. There is even information from external sources required for the system to work. For this reason, reliable communication is required inside the vehicle and between the vehicle and the surface station, or even beyond the surface station. Some information needs to be transmitted in real or near real time (for example navigation video, navigation variables, and safety variables, among others). Depending on the amount of information collected or the system’s capabilities, information can be partially transmitted while some other is stored and analyzed after the mission.

To store information. Given the volume of data that is generated, a strategic approach to data storage is essential. Information storage, whether onboard the ROV, at the surface station, or distributed across both, must prioritize data integrity, organization, and accessibility. This function addresses the need for comprehensive data management strategies to accommodate the extensive data collected during missions of the robotic system.

Notice how these descriptions are not focused on which specific device or strategy is going to be used. All the descriptions are centered on what needs to be done. This is part of the SE approach to functional and systemic thinking. Once this level of detail is obtained, it is easier for the engineering team to think about devices and equipment that might serve as solutions to reach the functional objective. However, before selecting specific physical components, the functions need to be well established and interrelated between them, as well as the interaction with external inputs and variables.

5.4. Integrating Functional Decomposition with Industry 4.0 Enhancements

Functions presented in

Figure 5 are a part of the set of tasks that need to be fulfilled for the ROV to perform as required by customers. The next step in the design is to establish solution alternatives for each function and to select the best ones. For selecting alternatives engineering characteristics from the HoQ are used as the basis for decision-making criteria.

At this point, we introduce one more tool to help explain the approach for I4.0 technologies in this conceptual design. The Kano Model [

94] is a framework used in product development to categorize customer preferences into five main types, aiming to enhance customer satisfaction. These categories are as follows.

Must-be Quality Attributes: Basic needs that are taken for granted when met but cause dissatisfaction when missing.

One-dimensional Quality Attributes: Features that lead to satisfaction when fulfilled and dissatisfaction when not, with a proportional relationship between the level of fulfillment and customer satisfaction.

Attractive Quality Attributes: Unexpected features that significantly increase customer satisfaction without causing dissatisfaction when absent, serve as differentiators.

Indifferent Quality Attributes: Features that neither enhance nor diminish customer satisfaction.

Reverse Quality Attributes: Features that can cause dissatisfaction when present and satisfaction when absent, varying among different customer segments.

The functions in

Figure 5 can be related to solutions into Kano’s Must-be and One-dimensional Qualities. These categories are about what is expected by customers and also required by them explicitly. It means that these characteristics can be traced back to user requirements.

The Attractive Quality category refers to characteristics that users are not expecting in the product, probably because they do not know the technology. In the context of ROVs systems, by understanding I4.0 capabilities, the design team may find characteristics that can be implemented on new models. It is possible that customers did not require all of them, but it doesn’t mean they are not useful or important. Attractive Quality does not necessarily include new functions to the system, but it may change the way functions are usually solved.

Section 5.3.1 describes the functions for functional group “To manage information”. From those descriptions, it is clearly expected that ROV pilots or users will be in charge of analyzing all the information generated by the ROV system. What if, by introducing I4.0 capabilities, the ROV system can make some of the decisions, assist the pilots, or find some of the results and save some time and work for pilots and users?

This part of the work aims to discuss some alternative solutions including I4.0 technologies. These are not traditional solutions to ROV’s functions but may be interesting Attractive Quality Attributes.

Table 4 presents functions from

Figure 5 with a summarized example of how they are typically solved in terms of devices/components. It also suggests ideas that may be added to those functions by taking advantage of I4.0 tools. The last column shows which user requirements may be beneficially impacted if the new approach is implemented, the numbers correspond to the requirement ID on

Table 2. In this way,

Table 4 connects the functional thinking from logical decomposition with the functional description of I4.0 technologies presented in

Table 1 and user requirements.

As an example, let us consider surveying fish populations and coral species on deep coral reefs (depths greater than 80 meters). It is expected that the ROV capture video of the area. ROV pilots are not necessarily biologists, hence, they are not able to identify what they are watching on screen. Biologists might be in the control room, but real-time video is too fast to identify all the specimens recorded. Biologists will have to take a copy of the video and analyze every second in order to obtain the expected survey. This process can take a lot of time and the survey will be finished only after the expedition has already ended. What if the ROV is equipped with an AI image recognition model which can generate the survey in real or near real time? This would be an improved solution to the requirements of storing data of variables of interest and storing image information (Req. IDs 4 and 7).

Another example can be related to automatic lighting. ROV pilots have the task of regulating the ROV lights in order to allow the cameras to record when ambient light is not enough. However, pilots’ perception of lightning may not be the best for the cameras. The ROV could be equipped with a smart lighting system trained to improve lighting for videos and images. This may work based on IoT tools and a photography-trained AI. This would be beneficial for collecting physical samples, acquiring images, image quality, ROV positioning, and even maneuverability (Req. IDs 1, 2, 3, 8, and 10).

From the functions described, it is also viable to see an ROV as a source of data from different origin (video, pictures, sensor values, digital data, weather reports, coordinates, etc.) and in structured, semi-structured, and non-structured formats. Since missions can last hours, and an expedition may include several missions, an ROV may become a source of data with Big Data characteristics: velocity, volume, value, variety, and veracity. From this point of view, it makes sense to take advantage of already existing Big Data tools to manage the information. Requirements 4 and 7 would be impacted by this approach.

The objective of this study case, which focuses on one functional group of an ROV system, was to show a path for stating divergent solutions inspired by the possibilities provided by Industry 4.0 tools. This path is well structured by using Systems Engineering concepts and tools that can be used not only for ROVs but for other complex systems under development.

As described, the next step in the design would be to establish solution alternatives for each function and to select the best ones. This would be part of a divergence and convergence process included in the design solution definition stage. Even with Industry 4.0 technologies suggested to improve some of the ROV functions, there will be several alternatives for implementation (hardware and components alternatives and brands, service providers, software platforms, etc). Selecting components and providers is outside the scope of this study case.

6. Discussion

The integration of Systems Engineering with Industry 4.0 technologies is a tool for innovation. In this case, by adopting a functional-oriented view of technology integration, ROVs that are potentially more effective, efficient, and adaptable to the complex demands of underwater missions are conceptualized. However, we only approached one of the functional groups from

Figure 4, this means there is still room for more conceptual improvements and ideas to be explored by using the same approach.

Through the study, it has been illustrated how ROVs can be transformed by Industry 4.0 technologies, specifically through the integration of AI for real-time data analysis and autonomous decision-making. This is a departure from traditional ROVs that primarily rely on direct human control. The smart integration of IoT and Big Data analytics into ROVs can lead to improved operational autonomy, enabling these vehicles to perform high-precision tasks with greater reliability and less human intervention. The approach not only aligns with the evolving demands of underwater exploration and monitoring but also sets lines for future research in marine technology.

A challenge associated with Industry 4.0 lies in its technology-centric approach, often leading to a disconnection between the tools developed and the actual needs of the user. The tendency to impose or sell technologies without a complete understanding of user requirements must be avoided. This study addresses such challenges by advocating for a user-centered design paradigm, which ensures that technology integration aligns closely with user requirements and enhances system usability.

The integration of Systems Engineering with Industry 4.0 technologies provides a powerful framework for addressing the complex demands of modern engineering projects. This study demonstrates the practical application of design theories within a real-world case study, showcasing how Systems Engineering can be adapted to develop advanced robotic systems. By focusing on stakeholder needs and functional requirements, the Systems Engineering approach ensures that all aspects of the design process are comprehensively addressed, providing a robust methodology for managing complexity.

The incorporation of Industry 4.0 technologies, such as IoT, AI, and Big Data, into the ROV design significantly enhances the system’s capabilities. These technologies enable real-time data processing, autonomous decision-making, and improved operational efficiency, illustrating the transformative potential of Industry 4.0 tools. This integration not only aligns with current trends in industrial design but also sets the stage for future advancements in robotic systems and other complex engineering projects.

Managing the complexity of the ROV design required a structured approach that decomposed the system into manageable subsystems. Systems Engineering methodologies provided the necessary tools to coordinate the development of these subsystems, ensuring seamless integration and functionality. This approach can be applied to other complex engineering projects, demonstrating the versatility and effectiveness of Systems Engineering in managing complexity.

Future research should explore the integration of additional Industry 4.0 technologies and further refine the methodologies used in this study. Potential areas for investigation include the application of advanced AI algorithms for autonomous navigation and decision-making, the use of blockchain for secure data management, and the development of more sophisticated IoT networks for enhanced connectivity.

The concept of User-Centered Design prioritizes the end user’s needs, challenging the notion that technology should dictate user behavior [

95]. Rather, technology should seamlessly integrate into users’ lives by addressing their specific requirements. The emphasis is not solely on adopting the latest trend but on configuring, personalizing, improving, or creating solutions that align with the users’ needs and preferences.

Table 4 which connects functions, solutions, suggested functional improvements and user requirements makes explicit the User-Centered Design approach in this study case.

Moreover, the emerging concept of Society 5.0 offers a corrective to the shortcomings of Industry 4.0. In this paradigm, the technologies pioneered by Industry 4.0 are harnessed with a clear focus on serving humanity [

1,

96,

97]. Society 5.0 envisions a convergence of these innovations to enhance the quality of life for individuals. It represents a paradigm shift where technology, rather than being an end in itself, becomes a means to execute tasks that directly address and fulfill the diverse needs of people.

This work provides an example of how Industry 4.0 technologies can be integrated into complex systems, like ROVs, while still focusing on user requirements. In this way, this research underscores how Systems Engineering, a mature and robust platform, can facilitate the transition and support the realization of Industry 5.0 by integrating complex systems more thoughtfully and sustainably.

The conceptual design exercise presented also aligns with the INCOSE Systems Engineering Vision 2035 [

98], with ideas like the emphasis on integrating advanced technologies and adopting a holistic, stakeholder-focused approach to SE. Vision 2035 envisions a future where Systems Engineering leads in the development and integration of complex systems, enhancing their functionality and adaptability to meet changing requirements and environments.

Additionally, INCOSE highlights the importance of sustainable and human-centric design approaches. United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and the Society 5.0 concept are actually explicit referents for Systems Engineering Vision 2035. This reflects a call for systems engineers to be leaders in technological development and integration while remaining aware of the societal and environmental impacts of their designs. In other words, to keep developing technology focused on humanity’s challenges and needs.

An important limitation of the presented work is that the case study only addressed one out of five main functional groups presented in

Figure 4. A full conceptual design will have to analyze all functional groups and each of their sub-functions. This gives an idea of the amount of work required for just the conceptual design of a complex system and the involvement of new technologies in the development process. After a full conceptual design, the design solution definition and product realization process should be implemented in order to achieve the complete ROV development. Those design stages are necessary to deal with potential challenges, limitations, and mitigation strategies. This includes addressing technological readiness, cost implications, operational risks, and any potential resistance to adopting new technologies.

7. Conclusions

This paper addressed the conceptual design stage of an underwater robotic exploration system using systems engineering. The process was divided into three steps: stakeholder expectations, requirements definition, and logical decomposition. These steps were taken from the Systems Engineering approach, emphasizing a system and function-centered methodology where users are central by prioritizing user requirements.

Our study presents a practical application of design theories within the framework of Systems Engineering. By focusing on the conceptual design stage, we demonstrated how traditional design methodologies could be adapted and applied to modern engineering challenges. This case study exemplifies the integration of stakeholder needs and requirements into the design process, showcasing how theoretical concepts are translated into practical, actionable design strategies. The use of Systems Engineering principles facilitated a structured approach, ensuring that all functional requirements were comprehensively addressed.

The integration of Industry 4.0 technologies into the design of the ROV system was a key aspect of this study. By leveraging advancements such as IoT, AI, and Big Data, we proposed innovative solutions that enhance the functionality and performance of the robotic system. This approach not only aligns with the current trends in engineering design but also demonstrates the potential of I4.0 technologies to revolutionize traditional systems. The proposed methods highlight the synergy between conventional engineering practices and digital innovations, fostering an environment of continuous improvement and connectivity.

The complexity inherent in designing a sophisticated system like an ROV was managed through the application of Systems Engineering principles. By decomposing the system into functional groups and addressing each aspect systematically, we illustrated how to handle the intricate interplay of multiple components and subsystems. This structured approach ensured that the design process remained coherent and manageable, despite the high level of complexity involved. The case study serves as a reference for managing complexity in the design of advanced mechanical systems, providing insights that can be applied to similar engineering projects

With a function-centered analysis, it was possible to connect the robotic system’s conceptual design with the Industry 4.0 capabilities. The conceptual examples of Industry 4.0 tools working for improving ROV’s performance provide a range of possibilities that would have to be addressed by further design stages. However, these possibilities are already oriented to improve the user’s experience when the final system is developed.

A path for proposing divergent solutions inspired by the possibilities provided by Industry 4.0 tools was presented. This path is well structured by using Systems Engineering concepts and tools that can be used not only for ROVs but for other complex systems under development.

Systems Engineering continues to play a central role in the development of advanced technologies. Its user-centered principles and functional approach not only align with but also support the objectives of Industry 5.0. This is echoed in the INCOSE Systems Engineering Vision 2035, which advocates for these methodologies as foundational for future technological advancements in the benefit of society.

This study intends to provide a case study that helps to understand core System Engineering ideas for conceptual design while embracing Industry 4.0 technologies and highlighting the importance of understanding their functions before any implementation. The results are intended to promote the use of Systems Engineering techniques across different industries, aiding in the design and implementation of systems that are technologically sophisticated, robust, efficient, and focused on the user’s needs.

Ultimately, this research aims to contribute to the conversation about Systems Engineering in the digital era, providing insights and ideas that can be customized and used across various high-tech fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.R.C, E.A.T, and R.E.V.; methodology, E.A.T, and R.E.V.; validation, J.A.R.C., J.S.P., and R.E.V.; formal analysis, E.A.T., and E.P.G.; investigation, J.A.R.C., E.A.T, E.P.G, C.A.E., J.S.P., and R.E.V. writing—original draft preparation, E.A.T, E.P.G, C.A.E., J.S.P., and R.E.V.; writing—review and editing, J.S.P., and R.E.V.; supervision, J.A.R.C., J.S.P., and R.E.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was developed with the funding of the Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana (UPB) and with the support of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia in association with Contraloría General de la República in the frame of Contract CGR-373-2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Huang, S.; Wang, B.; Li, X.; Zheng, P.; Mourtzis, D.; Wang, L. Industry 5.0 and Society 5.0—Comparison, complementation and co-evolution. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2022, 64, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M.; Iranmanesh, M.; Mubarak, M.F.; Mubarik, M.; Rejeb, A.; Nilashi, M. Identifying industry 5.0 contributions to sustainable development: A strategy roadmap for delivering sustainability values. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2022, 33, 716–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziatdinov, R.; Atteraya, M.S.; Nabiyev, R. The Fifth Industrial Revolution as a Transformative Step towards Society 5.0. Societies 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE). INCOSE Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities, 2015.

- Rúa, S.; Vásquez, R.E.; Crasta, N.; Betancur, M.J.; Pascoal, A. Observability analysis for a cooperative range-based navigation system that uses a rotating single beacon. Ocean Engineering 2022, 248, 110697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, R.D.; Sr, R.L.W. The ROV manual, a user guide for Remotely Operated Vehicles; Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lahoz-Monfort, J.J.; Magrath, M.J.L. A Comprehensive Overview of Technologies for Species and Habitat Monitoring and Conservation. BioScience 2021, 71, 1038–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, Z.Y.; Kim, T.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, M. Metals and suspended solids in the effluents from in-water hull cleaning by remotely operated vehicle (ROV): Concentrations and release rates into the marine environment. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 460, 132456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilssen, I.; Odegard, T.; Sorensen. ; Johnsen, A.J. “Integrated environmental mapping and monitoring. a methodological approach to optimise knowledge gathering and sampling strategy, ” Marine Pollution Bulletin 2015, 96, 374–383. [Google Scholar]

- Ludvigsen, M.; Sorensen, A.J. “Towards integrated autonomous underwater operations for ocean mapping and monitoring. Annual Reviews in Control 2016, 42, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teigland, H.; Møller, M.T.; Hassani, V. Underwater Manipulator Control for Single Pilot ROV Control. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; You, H.; Du, J. Visual-haptic feedback for ROV subsea navigation control. Automation in Construction 2023, 154, 104987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; You, H.; Ye, Y.; Du, J. ROV teleoperation via human body motion mapping: Design and experiment. Computers in Industry 2023, 150, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Thies, P.; Lars, J.; Cowles, J. ROV launch and recovery from an unmanned autonomous surface vessel – Hydrodynamic modelling and system integration. Ocean Engineering 2021, 232, 109019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, A. , The Industrial Revolution 4.0. In Towards Process Safety 4.0 in the Factory of the Future; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2023; chapter 1, pp. 1–14, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9781394226375.ch1]. [CrossRef]

- Schwab, K.; Davis, N. Shaping the future of the fourth industrial revolution; Crown Currency: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lemstra, M.A.M.S.; de Mesquita, M.A. Industry 4.0: a tertiary literature review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2023, 186, 122204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özköse, H.; Güney, G. The effects of industry 4.0 on productivity: A scientific mapping study. Technology in Society 2023, 75, 102368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ruben, R.; Rajendran, C.; Saravana Ram, R.; Kouki, F.; Alshahrani, H.M.; Assiri, M. Analysis of barriers affecting Industry 4.0 implementation: An interpretive analysis using total interpretive structural modeling (TISM) and Fuzzy MICMAC. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, G.B.; Ghezzi, A.; Frank, A.G. When technologies become Industry 4.0 platforms: Defining the role of digital technologies through a boundary-spanning perspective. International Journal of Production Economics 2023, 260, 108858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.R.; Moreno, I.D. , Process System Engineering Tool Integration in the Context of Industry 4.0. In Computer Aided Chemical Engineering; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 469–474. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wanyama, T.; Singh, I.; Gadhrri, A.; Schmidt, R. From Industry 4.0 to Robotics 4.0 - A Conceptual Framework for Collaborative and Intelligent Robotic Systems. Procedia Manufacturing 2020, 46, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Substantial capabilities of robotics in enhancing industry 4.0 implementation. Cognitive Robotics 2021, 1, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchlewitz, S.; Nicklas, J.P.; Winzer, P. Using systems engineering for improving autonomous robot performance. 2015 10th System of Systems Engineering Conference (SoSE). IEEE, 2015, pp. 65–70. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C.; Fernandez-Sanchez, J.L. Model-based systems engineering to design collaborative robotics applications. 2017 IEEE International Systems Engineering Symposium (ISSE). IEEE, 2017, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Onstein, I.F.; Haskins, C.; Semeniuta, O. Cascading trade-off studies for robotic deburring systems. Systems Engineering 2022, 25, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, L.B.; Zuluaga, C.A.; Ramirez, J.A.; Vasquez, R.E.; Florez, D.A.; Taborda, E.A.; Valencia, R.A. Development of an Underwater Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) for Surveillance and Inspection of Port Facilities. Volume 11: New Developments in Simulation Methods and Software for Engineering Applications Safety Engineering, Risk Analysis and Reliability Methods Transportation Systems. ASME, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Correa, J.C.; Vásquez, R.E.; Ramírez-Macías, J.A.; Taborda, E.A.; Zuluaga, C.A.; Posada, N.L.; Londoño, J.M. An Architecture for the Conceptual Design of Underwater Exploration Vehicles. Ingeniería y Ciencia 2015, 11, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Castro, O.A.; Inzunza-González, E.; García-Guerrero, E.E.; Tlelo-Cuautle, E.; López-Bonilla, O.R.; Olguín-Tiznado, J.E.; Cárdenas-Valdez, J. Design and Construction of an ROV for Underwater Exploration. Sensors 2019, 19, 5387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossiakoff, A.; Sweet, W.; Seymour, S.; Biemer, S. Systems Engineering Principles and Practice; Wiley-Interscience, 2011.

- Honour, E.C. INCOSE: history of the International Council on Systems Engineering, 1998.

- Jantzer, M.; Nentwig, G.; Deininger, C.; Michl, T. Systems Engineering. In The Art of Engineering Leadership; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2020; pp. 25–35. [CrossRef]

- Hirshorn, S.R.; Voss, L.D.; Bromley, L.K. NASA systems engineering handbook. Technical report, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 2017.

- Faulconbridge, R.; Ryan, M. Systems Engineering Practice; Argos Press: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Haberfellner, R.; de Weck, O.; Fricke, E.; Vössner, S. Systems Engineering; Springer International Publishing, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kontogiannis, T.; Embrey, D. A user-centred design approach for introducing computer-based process information systems. Applied Ergonomics 1997, 28, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegenberg, J.; Cramar, L.; Schmidt, L. Task- and user-centered design of a human-robot system for gas leak detection: From requirements analysis to prototypical realization. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2012, 45, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standardization Council Industry 4.0. German Standardization Roadmap on Industry 4.0. Technical report, DKE Deutsche Kommission Elektrotechnik Elektronik Informationstechnik in DIN und VDE, Berlin, Germany, 2023. Accessed: 01/02/2024.

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Gawankar, S.A. Sustainable Industry 4.0 framework: A systematic literature review identifying the current trends and future perspectives. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2018, 117, 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musarat, M.A.; Irfan, M.; Alaloul, W.S.; Maqsoom, A.; Ghufran, M. A Review on the Way Forward in Construction through Industrial Revolution 5.0. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radanliev, P.; De Roure, D.; Nicolescu, R.; Huth, M.; Santos, O. Artificial Intelligence and the Internet of Things in Industry 4.0. CCF Transactions on Pervasive Computing and Interaction 2021, 3, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashima, R.; Haleem, A.; Bahl, S.; Javaid, M.; Kumar Mahla, S.; Singh, S. Automation and manufacturing of smart materials in additive manufacturing technologies using Internet of Things towards the adoption of industry 4.0. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 45, 5081–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Internet of things for smart factories in Industry 4.0, a review. Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems 2023, 3, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Ghosh, T.; Aurna, N.F.; Kaiser, M.S.; Anannya, M.; Hosen, A.S. Machine learning and internet of things in industry 4.0: A review. Measurement: Sensors 2023, 28, 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenizi, F.A.; Abbasi, S.; Hussein Mohammed, A.; Masoud Rahmani, A. The artificial intelligence technologies in Industry 4.0: A taxonomy, approaches, and future directions. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2023, 185, 109662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashtoush, T.; A. , J.; Herrera, J.; Hernandez, L.; Martinez, L.; E., M.; Escamilla, O.; E., R.; Diaz, A.; Jimenez, J.; Isaac, J.; Martinez, M. Space Mining Robot Prototype for NASA Robotic Mining Competition Utilizing Systems Engineering Principles. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Soto, D.A.P.; Veres, S.M.; Rossiter, A. Human Robot Interaction for Future Remote Manipulations in Industry 4.0. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 10223–10228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, R.F.N.; Arshad, H.; Rahman, A.H.A.; Albahri, O.S. Robotics Utilization in Automatic Vision-Based Assessment Systems From Artificial Intelligence Perspective: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 77537–77570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ye, X.; Wang, S.; Li, P. ULO: An Underwater Light-Weight Object Detector for Edge Computing. Machines 2022, 10, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, K. Internet of Things, Big Data, Industry 4.0 – Innovative Solutions in Logistics and Supply Chains Management. Procedia Engineering 2017, 182, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H. Big data, industry 4.0 and cyber-physical systems integration: A smart industry context. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 46, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Suman, R. Digital Twin applications toward Industry 4.0: A Review. Cognitive Robotics 2023, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, A.; Sahed, M.; Tasneem, Z.; Das, P.; Badal, F.; Ali, M.; Ahamed, M.; Abhi, S.; Sarker, S.; Das, S.; Hasan, M.; Islam, M.; Islam, M. Towards next generation digital twin in robotics: Trends, scopes, challenges, and future. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlădăreanu, L.; Gal, A.I.; Melinte, O.D.; Vlădăreanu, V.; Iliescu, M.; Bruja, A.; Feng, Y.; Ciocîrlan, A. Robot Digital Twin towards Industry 4.0. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 10867–10872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, B.; Manandhar, P. Integrating Computer Vision and CAD for Precise Dimension Extraction and 3D Solid Model Regeneration for Enhanced Quality Assurance. Machines 2023, 11, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Ardolino, M.; Bacchetti, A.; Perona, M. The applications of Industry 4.0 technologies in manufacturing context: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Production Research 2020, 59, 1922–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, T.S.; Xiong, G.; Shen, Z.; Leng, J.; Fang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Lodhi, E.; Wang, F.Y. 3D printing in materials manufacturing industry: A realm of Industry 4.0. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, M.S. , Cloud Computing Concepts. In Cloud Technologies and Services; Springer International Publishing, 2023; chapter 1, pp. 3–30. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Jiang, R.; Han, Y.; Li, A.; Peng, Z. A survey on cybersecurity knowledge graph construction. Security & Computers 2024, 136, 103524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Bilal, M.; Qiu, Y.; Qian, C.; Xu, X.; Raymond Choo, K.K. Survey on digital twins for Internet of Vehicles: Fundamentals, challenges, and opportunities. Digital Communications and Networks 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; Cao, G.; Zhang, P.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, Z. Multi-Analogy Innovation Design Based on Digital Twin. Machines 2022, 10, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Inventory management and information sharing based on blockchain technology. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2023, 179, 109196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elapolu, M.S.; Rai, R.; Gorsich, D.J.; Rizzo, D.; Rapp, S.; Castanier, M.P. Blockchain technology for requirement traceability in systems engineering. Information Systems, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godavarthi, B.; Narisetty, N.; Gudikandhula, K.; Muthukumaran, R.; Kapila, D.; Ramesh, J. Cloud computing enabled business model innovation. The Journal of High Technology Management Research 2023, 34, 100469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, F.F.; Oghazi, P.; Palmié, M.; Chirumalla, K.; Pashkevich, N.; Patel, P.C.; Sattari, S. Industry 4.0 and supply chain performance: A systematic literature review of the benefits, challenges, and critical success factors of 11 core technologies. Industrial Marketing Management 2022, 105, 268–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolakis, N.; Gasteratos, A. Sensor-Driven Human-Robot Synergy: A Systems Engineering Approach. Sensors 2022, 23, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.J. Introduction to robotics: mechanics and control; Pearson Educacion, 2006.

- Siciliano, B.; Khatib, O.; Kröger, T. Springer handbook of robotics; Vol. 200, Springer, 2008.

- Inaba, M.; Corke, P. Robotics Research: The 16th International Symposium ISRR; Vol. 114, Springer, 2016.

- Ding, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, K. A review of structures, verification, and calibration technologies of space robotic systems for on-orbit servicing. Science China Technological Sciences 2020, 64, 462–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, G.; Jenkin, M. Computational principles of mobile robotics; Cambridge university press, 2010.

- Niku, S.B. Introduction to robotics: analysis, control, applications; John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

- Post, M.A.; Yan, X.T.; Letier, P. Modularity for the future in space robotics: A review. Acta Astronautica 2021, 189, 530–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.; Brockhurst, J. “Subsea pipeline infrastructure monitoring: A framework for technology review and selection. Ocean Engineering 2015, 104, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedachalam, N.; Ramesh, S.; Subramanian, A.N.; Sathianarayanan, D.; Ramesh, R.; Harikrishnan, G.; Pranesh, S.B.; Prakash, V.D.; Jyothi, V.B.N.; Chowdhury, T.; Ramadass, G.A.; Atmanand, M.A. “Design and development of remotely operated vehicle for shallow waters and polar research. Underwater Technology (UT) 2015, 10., 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Toal, D.; Omerdic, E.; Dooly, G. “Precision navigation sensors facilitate full auto pilot control of SmartROV for ocean energy applications. Sensors 2011, 10., 6127381. [Google Scholar]

- NORSOK. NORSOK Standard U-102, 2012.

- Dukan, F. ROV motion control systems. PhD thesis, Ph.D. Thesis, Norweigian University of Science and Technology NTNU, 2014.

- Dukan, F.; Ludvigsen, M.; Sørensen, A.J. Dynamic positioning system for a small size ROV with experimental results. OCEANS 2011 IEEE - Spain, 2011, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.H. Vision-based tracking with projective mapping for parameter identification of remotely operated vehicles. Ocean Engineering 2008, 35, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Blanke, M.; Skjetne, R. Particle filter ROV navigation using hydroacoustic position and speed log measurements. 2012 American Control Conference (ACC), 2012, pp. 6209–6215. [CrossRef]

- Bonin-Font, F.; Oliver, G.; Wirth, S.; Massot, M.; Lluis Negre, P.; Beltran, J.P. Visual sensing for autonomous underwater exploration and intervention tasks. Ocean Engineering 2015, 93, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K.D.; Nguyen, H.D.; Ranmuthugala, D.; Forrest, A. A heading observer for ROVs under roll and pitch oscillations and acceleration disturbances using low-cost sensors. Ocean Engineering 2015, 110, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukan, F.; Sørensen, A.J. Integration Filter for APS, DVL, IMU and Pressure Gauge for Underwater Vehicles. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2013, 46, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choyekh, M.; Kato, N.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Dewantara, R.; Chiba, H.; Senga, H.; Yoshie, M.; Tanaka, T.; Kobayashi, E.; Short, T. Development and Operation of Underwater Robot for Autonomous Tracking and

Monitoring of Subsea Plumes After OilSpill and Gas Leak from Seabed and Analyses of Measured Data. In Applications to Marine Disaster Prevention: Spilled Oil and Gas Tracking Buoy System; Springer Japan: Tokyo, 2017; pp. 17–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavin, A.; Wilkinson, P.; Harwood, A.; Novak, M. Easy Approach to Requirements Syntax (EARS). 2009 17th IEEE International Requirements Engineering Conference. IEEE, 2009, pp. 317–322. [CrossRef]

- Department of Defense. , System Engineering Fundamentals; Defense Acquisition University Press: Fort Belvoir, VA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman, D. The Mechanical Design Process; McGraw-Hill, 2009.

- Ulrich, K.; Eppinger, S. Product Design and Development; McGraw-Hill, 2011.

- Aristizábal, L.M.; Zuluaga, C.A.; Rúa, S.; Vásquez, R.E. Modular Hardware Architecture for the Development of Underwater Vehicles Based on Systems Engineering. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2021, 9, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga, C.A.; Aristizábal, L.M.; Rúa, S.; Franco, D.A.; Osorio, D.A.; Vásquez, R.E. Development of a Modular Software Architecture for Underwater Vehicles Using Systems Engineering. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2022, 10, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisher, R.A.; Rhea, R.A. Pipe Drafting and Design; Gulf Professional Publishing, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dieter, G.E.; Schmidt, L.C. Engineering design Fourth Edition; McGraw-Hill, 2012.

- Kano, N. Attractive quality and must-be quality. Journal of the Japanese society for quality control 1984, 31, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Law, C.M.; Jaeger, P.T.; McKay, E. User-centered design in universal design resources? Universal Access in the Information Society 2010, 9, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, M. Society 5.0: Aiming for a new human-centered society. Japan Spotlight 2018, 27, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Vogel-Heuser, B.; Wang, L. Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0—Inception, conception and perception. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2021, 61, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE). Systems Engineering Vision 2035. https://www.incose.org/publications/se-vision-2035, 2022. Accessed: 13/04/2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).