1. Introduction

Neural stimulation has long been practiced as an effective treatment for chronic diseases and pain. In recent years, advancements in electronic engineering have brought significant attention to implantable stimulators with wireless power transfer (WPT) capabilities.

Among a series of WPT techniques, resonance inductive coupling technology is most commonly employed for neural stimulation[

1]. The basic principle is to utilize LC resonance characteristic to generate higher voltage or current and compensate the gain deduction caused by the enlarged gap. However, there are drawbacks of the traditional structure. The resonant frequency splits with varying coupling coefficient [

2], and the voltage gain is affected by load impedance.

It is a popular direction for improvement to added compensation networks to the original circuit and form hybrid topologies. Numerous structures have been proposed, such as LCC[

3,

4,

5], LCL[

6,

7] and others. Most of these topologies are designed for kW-level WPT[

8] and are modeled at frequency around 100kHz. For medical use, however, the WPT systems work at several hundred kilohertz to a few megahertz to ensure more compact size and biocompatibility[

1,

9,

10]. The parasite parameters like the stray capacitance become remarkable in this range, but are often neglected since they are trivial in lower frequency and in high-power system [

3,

4,

11,

12]. Additionally, researches from the perspective of power electronics typically focus on efficiency, which is not the top priority in low-power medical use. Therefore, the MRC structure should be remodeled and better tuned for medical applications.

For AM or ASK modulated implant stimulators[

13], insensitivity to misalignment is crucial because relative movement between the transmitter and receiver may lead to varying coupling coefficient, and consequently, changes in received voltage amplitude. The transmitter should be able to monitor the received voltage and implement feedback control. Besides complex wireless communication, one solution is to track the resonant frequency to maintain constant voltage gain[

14], yet the narrow ISM band strictly limit the adjustment range. Another approach is to adaptively compensate the MRC circuit by a selective impedance matching network[

15], but it is only capable for discrete control and involves bulky relays.

The purpose of this paper is to analyze and design the LCL-compensated WPT structure for constant voltage transmission, primarily for medical use.

Section 2 derives the characteristics of the structure by modeling the circuit and theoretically proves the feasibility of CV-WPT.

Section 3 presents the experimental results, and

Section 4 discusses the application methods.

2. Materials and Methods

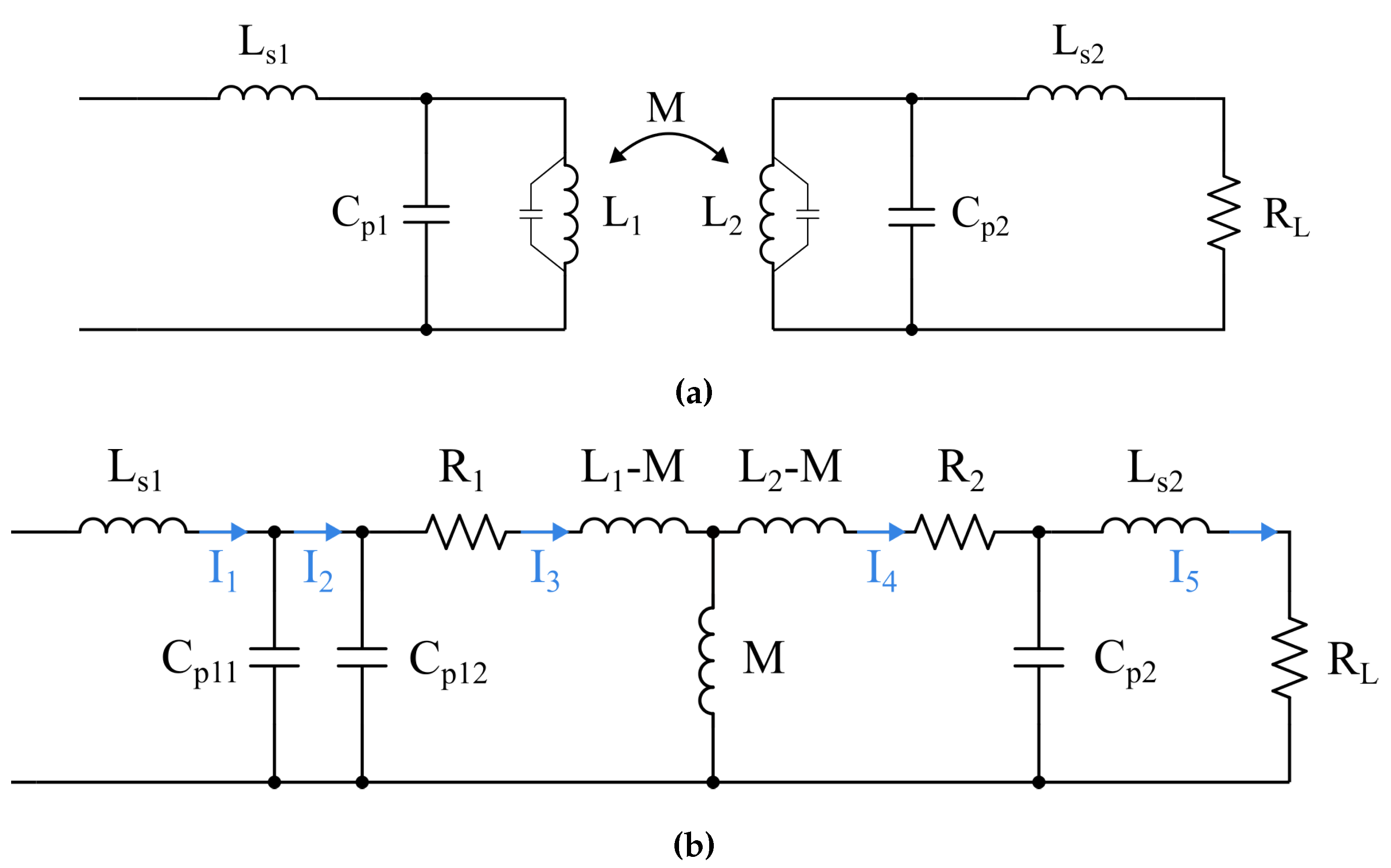

The proposed LCL-compensated WPT structure is shown in

Figure 1a. The coils with self-inductance

and

are coupled with mutual inductance

, where

k denotes the coupling coefficient.

depicts the equivalent AC load.

when the output is rectified and filtered. The circuit is re-drawn as

Figure 1b for analysis.

and

depict ESR of the coils.

is split into

and

using the conclusion of Li et-al[

12] to provide extra degree of freedom and achieve load-independent constant voltage transmission. Parasite capacitance of both coils are absorbed by

and

. The composited capacitance can be measured and tuned to ideal in practice, hence the parasite capacitance is neglected in analysis.

2.1. Load-and-Matching-Independent Resonant Frequency

Denote the mesh currents in

Figure 1b as

to

, the KVL matrix is written as:

In which

to

denote the complex impedance of each mesh. Parasite parameters are neglected temporarily. The voltage gain is then:

It is obvious that when

there are

and

, making the voltage gain irrelevant to both the load and the matching condition. To set this fully independent resonant frequency to be

, the circuit should satisfies:

Merge Equation (

3) and (

4), the voltage gain at

only depends on

k:

Equation (

5) demonstrates that the LCL-compensated voltage gain is inversely proportional to

i.e. the "turns ratio" of an ideally-coupled transformer, which makes smaller receiving coil possible. Notice that the electromagnetic attenuation is neglected here. However, the loss becomes dominant in loosely-coupled condition and (

5) no longer holds. Non-ideal parameters also restrict

from increasing further with smaller

k, which will be discussed later.

2.2. Online Estimation of Received Voltage

Although load-independent, voltage gain at still varies with k. A feedback loop with information of received voltage or the intermediate parameter k must be constructed. With LCL compensation, the needed signal can be extracted from the transmitting side. It avoids extra wireless communication from the receiver and enhances responding speed as well as robustness.

The input number is denoted as

in

Figure 1b. Let Equation (

4) into Equation (

1),

at

is obtained:

Where the effect of

cannot be eliminated, but can be reduced to negligible. Let

,

, it is obvious that

B is irrelevant to

. Then the effect of

on

is:

diminishes with larger

. For K

-level load, the load adjustment rate can be further reduced by tuning the inductors ratio. Although a small

is desired for more compact receiver, it is practical to have a larger

and smaller

. Notice that

, otherwise

becomes irrelevant to

k from Equation (

6).

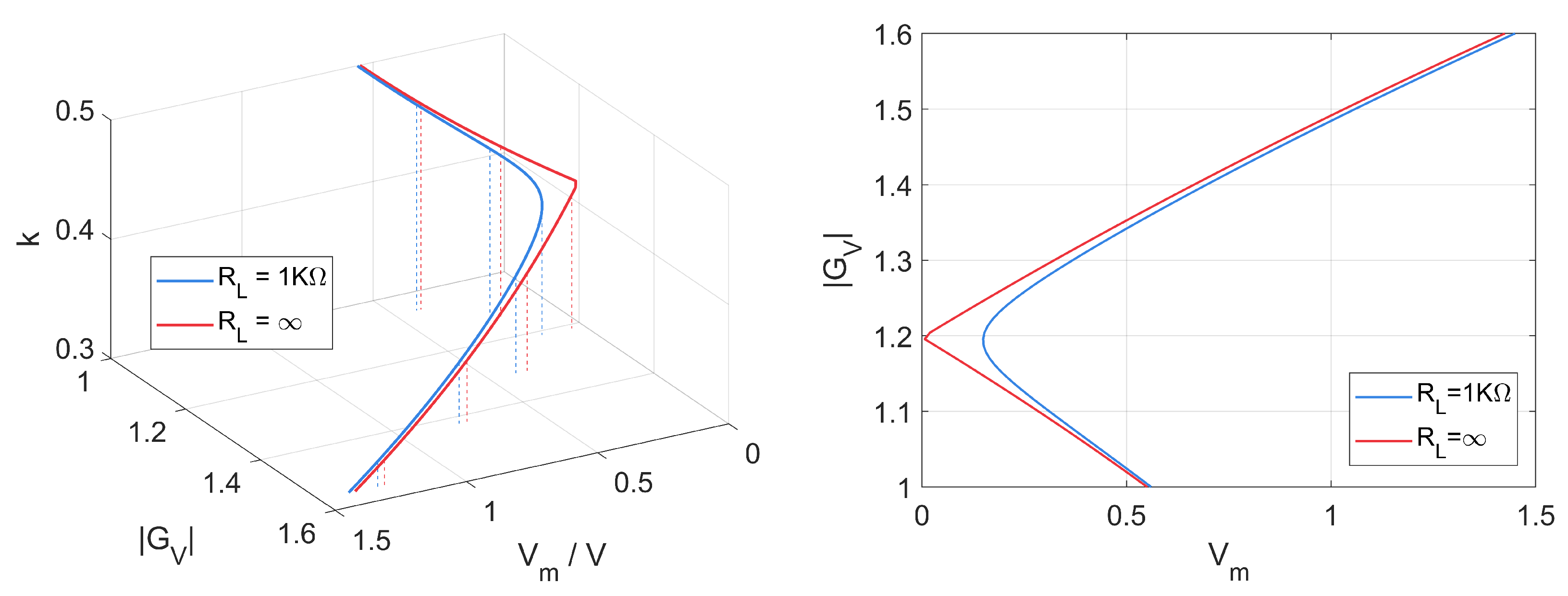

At light load, Equation (

6) becomes a function of

k.

monotonically deceases when

and increases otherwise. The boundary

is obtained by:

When

is not within the working range,

is a always a monotonic function. Therefore the inverse function

is single-valued and can be used to estimate

k. Notice

is also where the maximum

lies. So

should be put as far as possible from the possible range of

k.

is extracted by measuring the amplitude of voltage across

.

Where

and

denotes the amplitude of the input and measured voltage respectively.

From Equation (

5), the overall voltage gain at

is a single-valued function of

k. Therefore for any measured

there is only one corresponding

. Hence the received voltage

can be estimated by Equation (

12). The relationship between

,

and

k is shown in

Figure 2.

Notice that Equation (

11) and (

12) only serve as a proof of the feasibility of the

k estimation. It is recommended to plot

in experiment to cover the disturbance of parasite parameters, which will be discussed later.

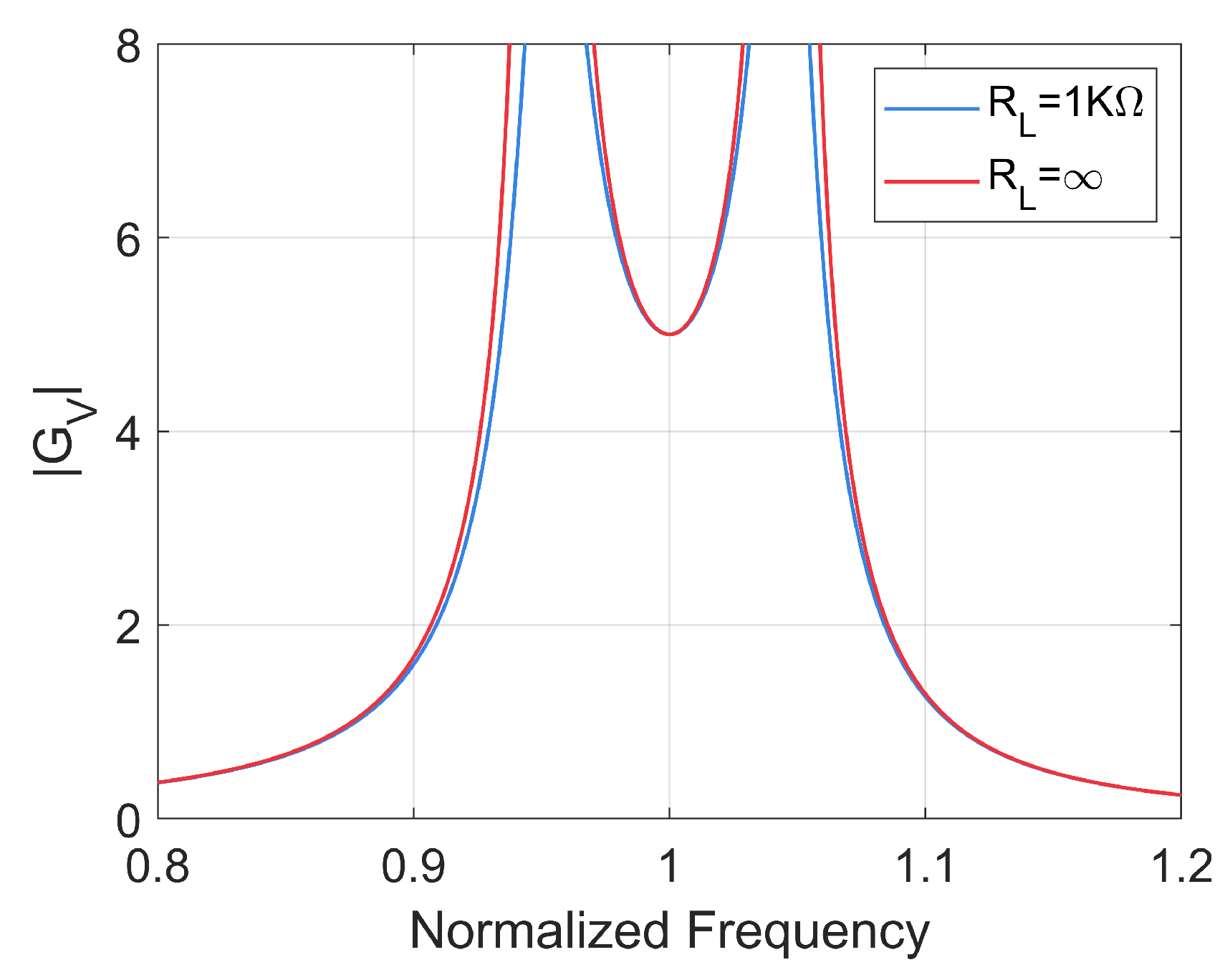

2.3. Minimization of Effect of Frequency Error

By selecting compensation component value as given in Equation (

4), it is straightforward to demonstrate that

is the independent resonant frequency where

. However,

is not necessarily where the maximum voltage gain is achieved. A high Q-value in the LCL-compensated WPT circuit may results in significant overvoltage with minor deviations in frequency, posing risks especially in medical applications. Therefore, it is advisable to smoothen the gain curve around

.

To obtain

as a function of

, expand

in Equation (

3):

Where

is the weight matrix of the polynomial function

. It is omitted here for simplicity. The analytical solution of peaks of

is hard to obtained, but it is still easy to investigate whether

is one of the solution. With the resonance characteristic that

,

as long as

.

Obtain the derivative of Equation (

13) to

, then substitute

with

:

The real part of Equation (

14) is variable with

k. Thus

cannot be a static peak. However, when an average coupling coefficient

is determined, the inductors can be tuned to minimize the gain slope around

as Equation (

15). The effect is demonstrated in

Figure 3.

2.4. Analyzing the Effect of Parasite Resistance

Denote ESR of

as

, and likewise

,

and

. The output impedance of the power source is absorbed by

.

and

forms a frequency-independent voltage divider, hence temporarily assume

for simplicity. Keep the values of the LC components so that the Equation (

4) still stands. The

matrix in Equation (

1) is re-written as Equation (

16).

Merge Equation (

2), (

4) and (

16).

with parasite resistance considered is obtained.

Observed from Equation (

19), the derivative of

to

is controlled by

. With K

-level load and

less than 10

, the load adjustment rate

is normally less than 0.1%.

When take into consideration, remains the same except of an extra voltage-division factor . usually has a lower Q-factor compared to for the strict size limitation of the implant receiver. However, for a reasonable and H at 10MHz, is still much smaller than , leading to a division factor of greater than . Therefore the voltage gain at can still be considered as load-independent.

It is obvious from Equation (

17) that

is still a single-valued function to

k, but is no longer monotonic with parasite resistance.

first increases with

k and then declines after a critical point

, which is written as:

The intermediate derivation is omitted for simplicity. From Equation (

20), The CV control is made easier as the gain around

becomes smoother.

Additionally, for

which is used to extract

k,

is indivisible from

. Equation (

7) is re-written as:

With

,

and

join the denominator,

becomes less sensitive to

.

In conclusion, the impact of parasite resistance on resonant frequency and k estimation is negligible in practice. While the exact number of does change, it can be easily tracked with experiment measurement and numerical simulation. Moreover, is irrelevant to the resonant frequency, allowing a relatively low Q-value for the receiving coil.

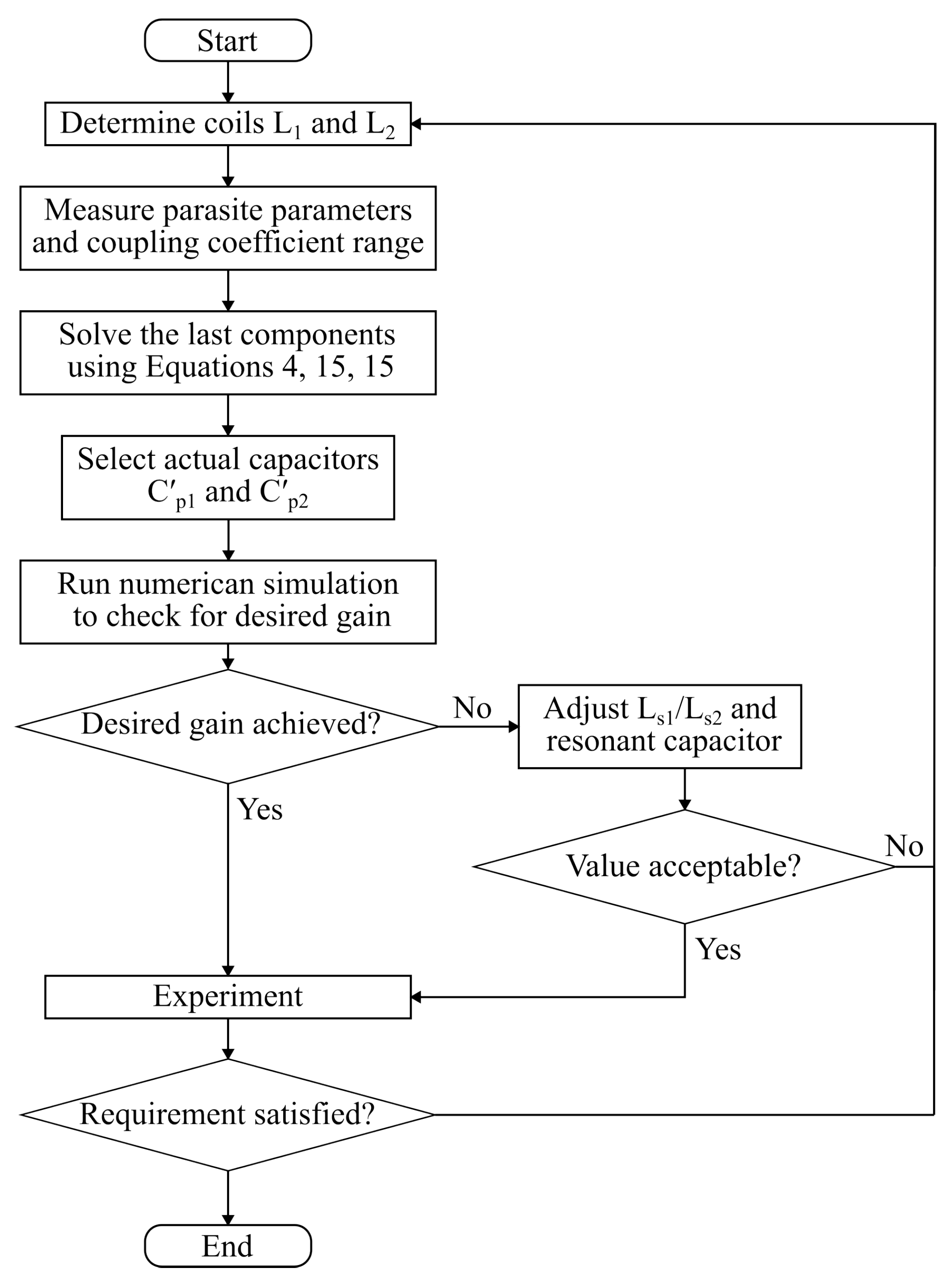

2.5. Design Procedure

The circuit in

Figure 1b has seven parameters to be determined. Given that the effect of the parasite resistance is limited, the circuit can be assumed as ideal when select the LC values. Based on experiment result, iteration may be needed to account for parasite parameters, including the stray capacitance of the coils.

The coil

and

should be determined before designing the LCC compensation circuit. The parasite parameters of coils and their coupling coefficient range is then measured. The last 5 components can be solved by Equation (

4),(

5) and (

15) to make the circuit resonant at

, smoothen the gain slope and acquire desired gain at

. The actual capacitors are selected as

and

. A numerical simulation based on Equation (

3) to check weather the desired gain is achieved. when not,

/

and the corresponding resonant capacitor must be adjusted. If the adjusted value is beyond acceptance, then roll-back to the coil designing.

Figure 4.

Design flowchart

Figure 4.

Design flowchart

3. Results

3.1. Validation of LCL-Compensated WPT and Voltage Gain Estimation

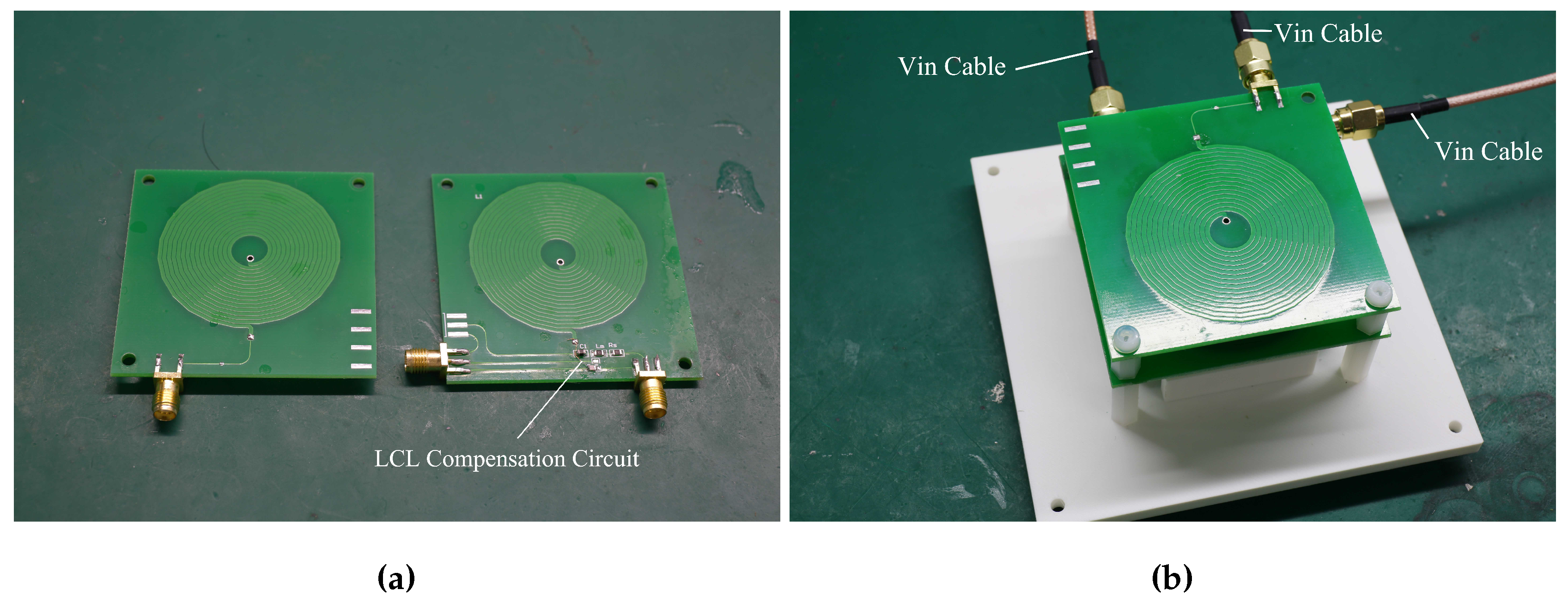

An experiment platform of LCL-Compensated WPT circuit that works on 6.78MHz ISM band is constructed, shown in

Figure 5. The coils are implemented on FR4 PCBs and of circular shape. The detailed parameters are listed in

Table 1 and

Table 2. To adjust the coupling coefficient, i.e. the distance between the coils, the PCBs are fixed on a 3D-printed PLA material base, with the length of the nylon columns between them adjustable.

The transmitter is driven by signal generator via SMA cable. As 0805 chip inductors are used in the compensation circuit, the driving voltage is set to 300mVpp. and are monitored by oscilloscope. To cover the internal resistance of the signal generator, is also monitored, and data is normalized as .

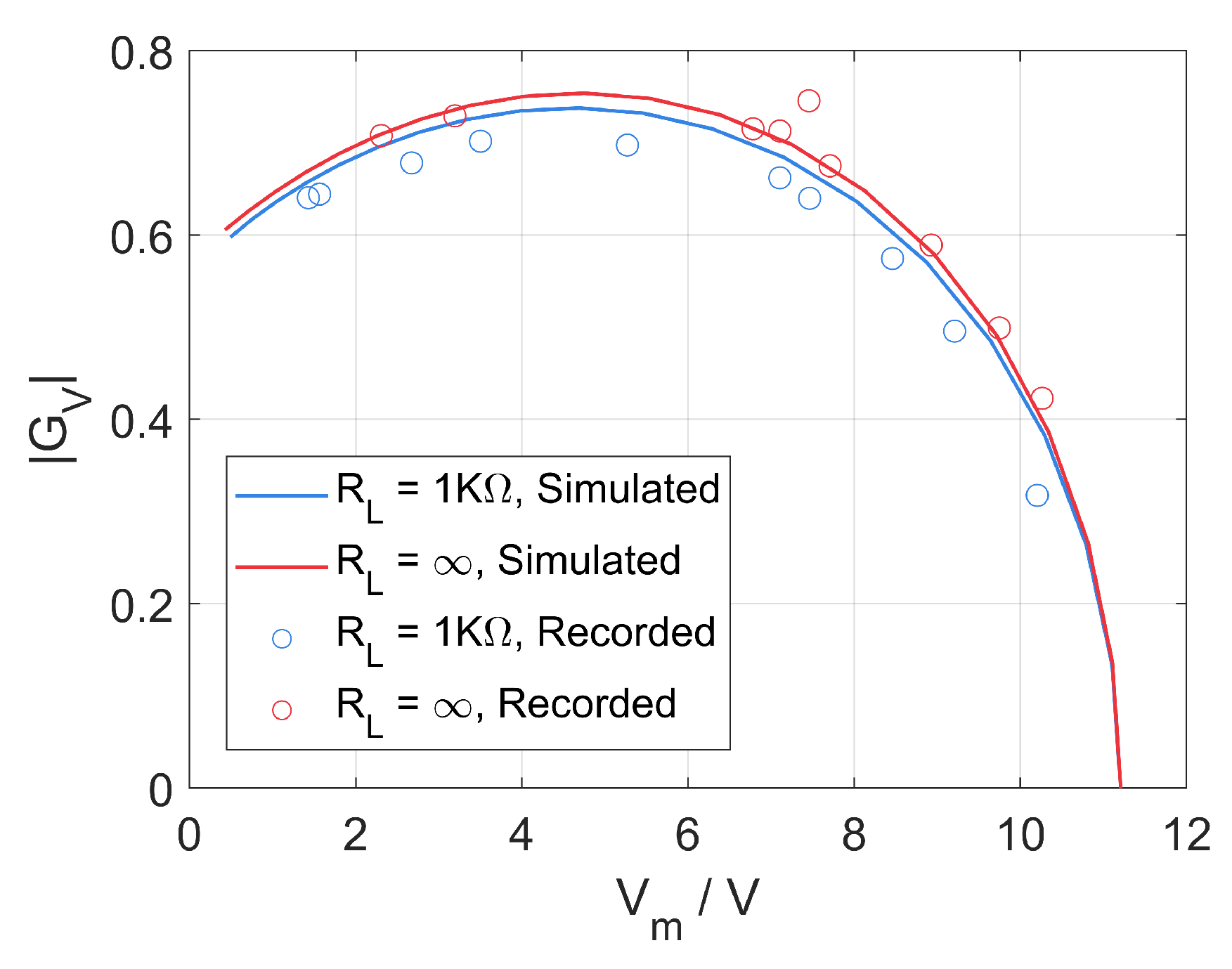

Two sets of data are recorded in experiment, with

pure resistive load and open-circuit respectively. The recorded result and theoretical

curves are plotted in

Figure 6.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of experiment result

The recorded data in

Figure 6 shows that the

characteristic of experiment circuit follows the identical trend as that of the mathematical model proposed in section 2. The effect of load changes on the

estimation is limited, but still observable. Data points of

load deviate from the theoretical curve farther, as the parasite parameters vary at the frequency higher than those at which they were measured.

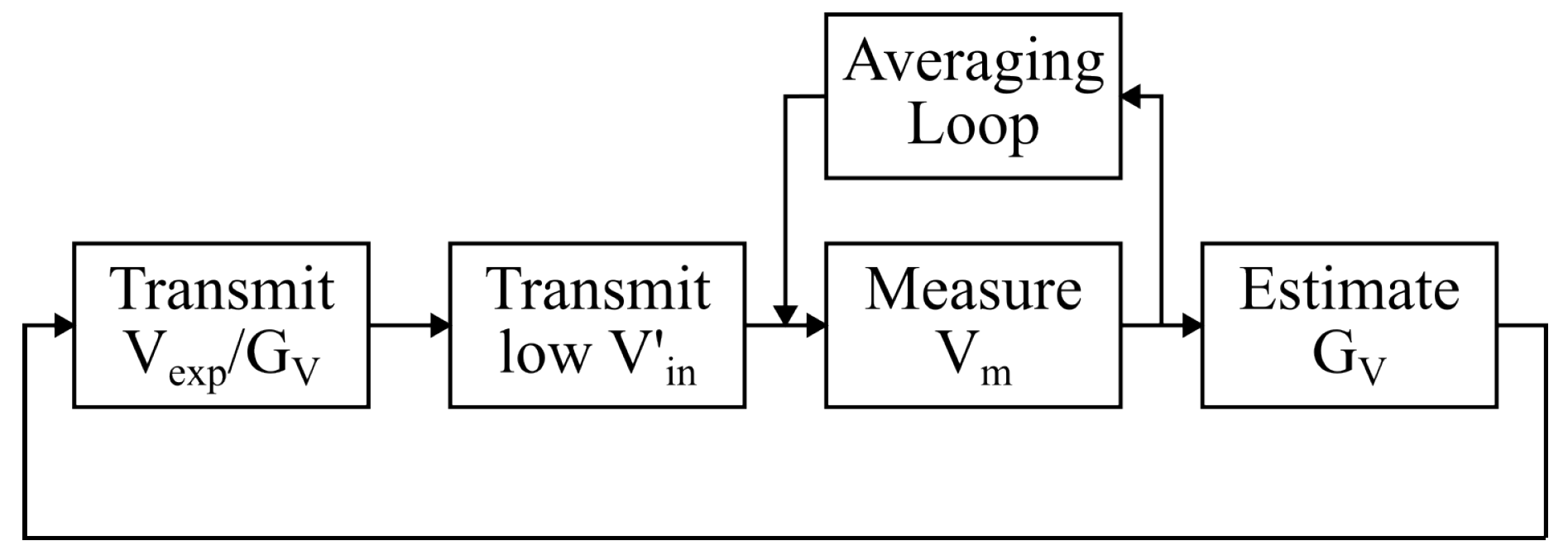

Noises occurred in the measurement has affected the recorded data, creating inconsistent points. Such noises are expected to appear in applications as well. Averaging may be required to ensure the accuracy of the

estimation. Additionally, as the independency of resonant voltage gain is slightly weaker than expected due to complex parasite parameters,

should be measured during intervals of transmission with lower

, based on Equation (

7). The new estimation strategy is shown in

Figure 7.

4.2. Application

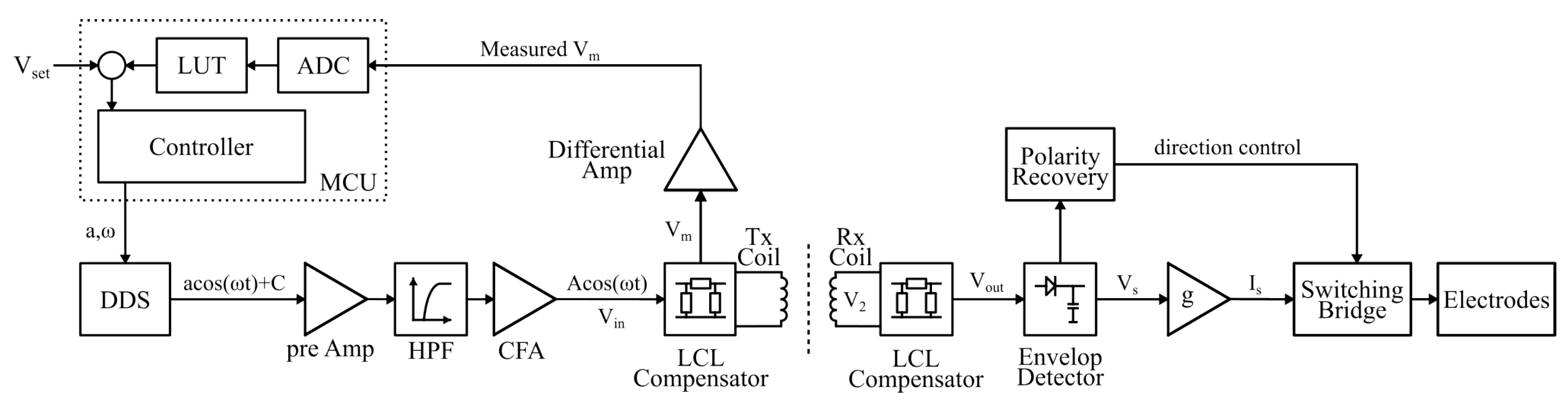

The proposed CV-WPT strategy is planned to be implemented in an implant neural stimulating system shown in

Figure 8. To achieve bipolar current stimulation, the system uses amplitude modulation (AM) to transfer power. A threshold voltage is established in the implant stimulator. When the demodulated AM signal surpasses the threshold, the stimulator outputs positive current and vice versa. This procedure is referred as Polarity Recovery. The aforementioned CV-WPT techniques provides robust and precise control with varying

k. We use a linear transmission circuit built by Direct Digital Synthesis (DDS) and High-Power Output Current Feedback Amplifier (CFA) for better accuracy, with a trade-off of efficiency.

The MCU uses two LUTs to estimate the received voltage. First of them is derived from Equation (

11), it estimates

basing on measured

. The other is derived from Equation (

18) and outputs the corresponding

of given

. The desired

is calculated by

, and sent to the DDS. The intermediate

is also used to detect misalignment or fault.

5. Conclusion

The LCL-Compensated WPT circuit is re-analysis for constant voltage transmission. The proposed CV-WPT system uses voltage measures on the transmitting side to estimate the coupling coefficient and voltage gain. Its feasibility is proved and the load-independent characteristic is validated through experiment. Compared to existing methods, our approach does not require frequency sweep or bulky components such as RF relays. The tuning strategy helps further shrink the size of the implant receiver.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zhiyang Cao, Shicong Gui, Chujia Xu and Yubo Li; Formal analysis, Zhiyang Cao; Investigation, Chujia Xu, Rui Zhong and Zhaotan Lin; Project administration, Yubo Li; Resources, Yubo Li; Software, Rui Zhong and Zhaotan Lin; Supervision, Yubo Li; Validation, Zhiyang Cao; Writing – original draft, Zhiyang Cao; Writing – review & editing, Shicong Gui. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Key R&D Program of Zhejiang Province grant number 2022C03038; BLB19J014.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request. Please connect the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support and collaboration of Qizhen Taichi Medical Co, Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Haerinia, M.; Shadid, R. Wireless Power Transfer Approaches for Medical Implants: A Review. 1, 209–229. Number: 2 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.Q.; Chu, J.X.; Gu, W.; Shen, A.D. Exact Analysis of Frequency Splitting Phenomena of Contactless Power Transfer Systems. 60, 1670–1677. [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Cai, T.; Duan, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C. An LCC-Compensated Resonant Converter Optimized for Robust Reaction to Large Coupling Variation in Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer. 63, 6591–6601. Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Cheng, D.; Wei, K. An LCC-C Compensated Wireless Charging System for Implantable Cardiac Pacemakers: Theory, Experiment, and Safety Evaluation. 33, 4894–4905. Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, W.; Deng, J.; Nguyen, T.D.; Mi, C.C. A Double-Sided LCC Compensation Network and Its Tuning Method for Wireless Power Transfer. 64, 2261–2273. Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Mao, M.; Ma, H. An LCL-Based SS Compensated WPT Converter With Wide ZVS Range and Integrated Coil Structure. 68, 4882–4893. Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Samanta, S. A Novel Parameter Tuning for LCL–LCL WPT With Combined CC/CV Charging and Improved Harmonic Performance. pp. 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Abou Houran, M.; Yang, X.; Chen, W. Magnetically Coupled Resonance WPT: Review of Compensation Topologies, Resonator Structures with Misalignment, and EMI Diagnostics. 7, 296. Number: 11 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.L.; Chang, C.K.; Lee, S.Y.; Chang, S.J.; Chiou, L.Y. Efficient Four-Coil Wireless Power Transfer for Deep Brain Stimulation. 65, 2496–2507. Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Cirmirakis, D.; Schormans, M.; Perkins, T.A.; Donaldson, N.; Demosthenous, A. An Integrated Passive Phase-Shift Keying Modulator for Biomedical Implants With Power Telemetry Over a Single Inductive Link. 11, 64–77. Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Circuits and Systems. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wong, S.C.; Tse, C.K.; Ruan, X. Analysis, Design, and Control of a Transcutaneous Power Regulator for Artificial Hearts. 3, 23–31. Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Circuits and Systems. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Tong, X. Research and Design of Misalignment-Tolerant LCC–LCC Compensated IPT System With Constant-Current and Constant-Voltage Output. 38, 1301–1313. Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Zhao, J.; Li, P.; Liu, X.; Xu, Y.P.; Je, M. Implantable stimulator for biomedical applications. 2013 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Workshop Series on RF and Wireless Technologies for Biomedical and Healthcare Applications (IMWS-BIO), pp. 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.D.; Sun, C.; Suh, I.S. A proposal on wireless power transfer for medical implantable applications based on reviews. 2014 IEEE Wireless Power Transfer Conference, pp. 166–169. [CrossRef]

- Beh, T.C.; Kato, M.; Imura, T.; Oh, S.; Hori, Y. Automated Impedance Matching System for Robust Wireless Power Transfer via Magnetic Resonance Coupling. 60, 3689–3698. Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).