Submitted:

27 June 2024

Posted:

28 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategies

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

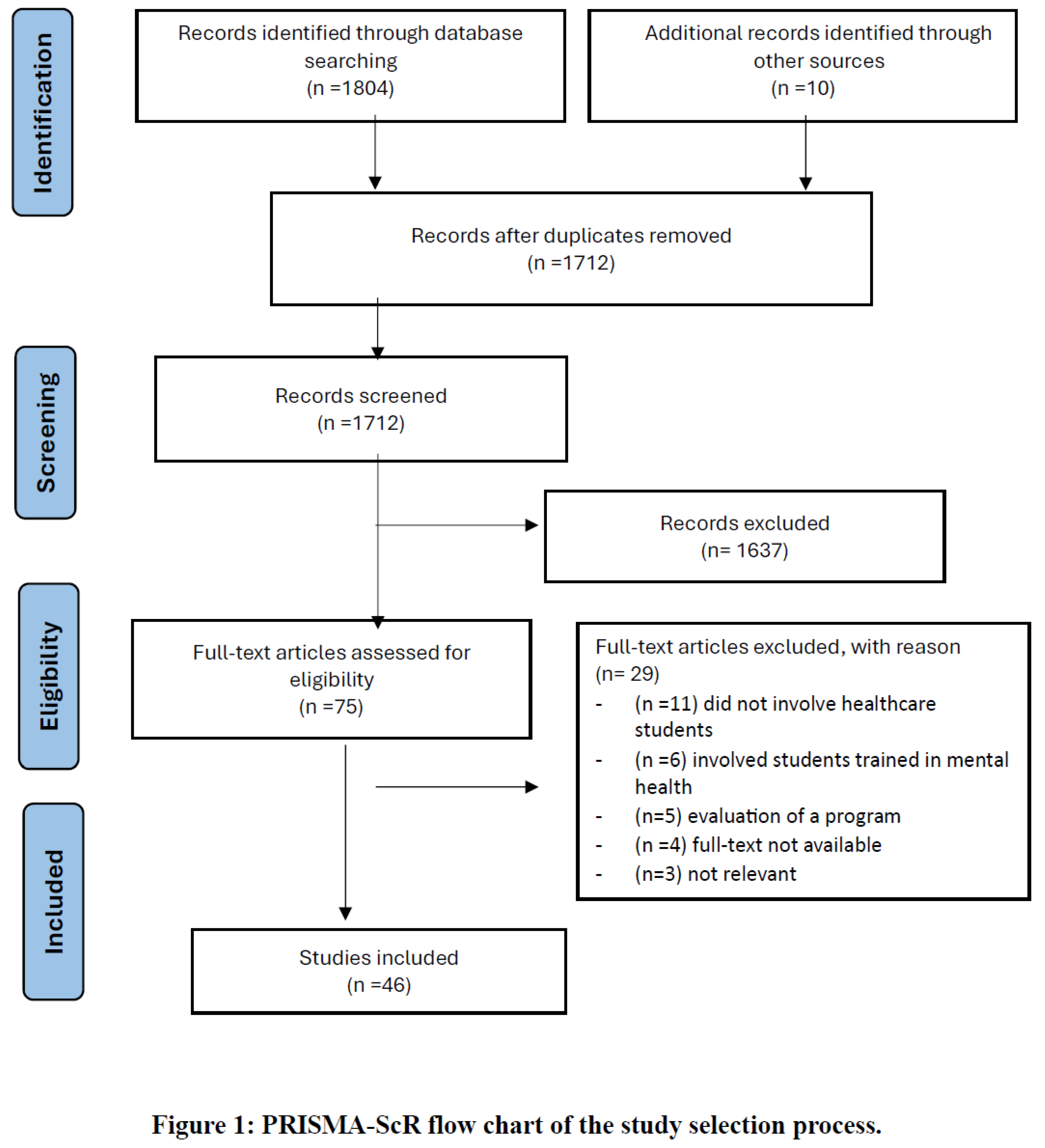

3.1. Study Search

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Key Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Future Research and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A.

- Studies from database inception to 31st December 2023.

- Databases used for searches:

- PubMed

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

- Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

- Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

- Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE)

- PsycINFO

- Database of Abstracts of Review of Effects (DARE)

- Inclusion criteria

- Studies that evaluated the attitude and/ or knowledge on suicide and/ or suicide related programs, and involves healthcare students from professions such as medicine, nursing, pharmacists, dentistry, and allied health such as paramedics, oral health therapists, and dental therapists as study population.

- 2.

- Exclusion criteria

- Reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, conference abstracts, conference proceedings, in vivo studies, in vitro studies, animal studies, thesis, and letter to editors.

- Studies that were written in other languages than English.

- Studies without available abstracts and full texts.

- Studies that evaluated healthcare students with special training in psychiatry such as psychiatric trainees, psychology students and mental health nurses, and midwives.

- Studies that evaluated healthcare students’ suicide rate and suicidality.

- Studies that evaluated healthcare students’ attitude and/ or knowledge on physician assisted suicide.

- Studies with outcomes that are not specific, such as the attitudes towards both depression and suicide.

- In studies which evaluation of an intervention is the focus, pre-test attitudes or knowledge assessments are unavailable.

- Search healthcare term (A)

- Search student term (B)

- Search knowledge & attitude terms (C)

- Search suicide term (D)

- Combine healthcare, student, knowledge & attitude, and suicide terms (A+B+C+D)

- Exclude reviews, systematic reviews, animal studies, and other non-research articles.

- Screen titles and abstracts for studies evaluating healthcare students’ knowledge of and attitude toward suicide.

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (accessed on.

- Saloni Dattani, L.R.-G. Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina. Suicides. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/suicide (accessed on.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts About Suicide. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html (accessed on.

- Sveen, C.A.; Walby, F.A. Suicide survivors’ mental health and grief reactions: a systematic review of controlled studies. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2008, 38, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, C.M.; Kinchin, I. Economic and epidemiological impact of youth suicide in countries with the highest human development index. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0232940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, S.; Funk, M.; Chisholm, D. Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2020. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 2015, 21, 461–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013-2020. 2013.

- Stene-Larsen, K.; Reneflot, A. Contact with primary and mental health care prior to suicide: A systematic review of the literature from 2000 to 2017. Scand J Public Health 2019, 47, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesec Rodi, P.; Roskar, S.; Marusic, A. Suicide victims’ last contact with the primary care physician: report from Slovenia. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2010, 56, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunkley, C.; Borthwick, A.; Bartlett, R.; Dunkley, L.; Palmer, S.; Gleeson, S.; Kingdon, D. Hearing the Suicidal Patient’s Emotional Pain. Crisis 2018, 39, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, N.C.; Sullivan, A.; Wilhelm, S.; Cohen, I.G. Effect of a legal prime on clinician’s assessment of suicide risk. Death Stud. 2016, 40, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheerder, G.; Reynders, A.; Andriessen, K.; Van Audenhove, C. Suicide intervention skills and related factors in community and health professionals. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2010, 40, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothes, I.A.; Henriques, M.R.; Leal, J.B.; Lemos, M.S. Facing a patient who seeks help after a suicide attempt: the difficulties of health professionals. Crisis 2014, 35, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.; Shipra, U. Attitudes of clinicians in emergency room towards suicide. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2006, 10, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A.; Pfeiffer, A. The ten most common errors of suicide interventionists; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, L.; Jacob, S.A. Pharmacists’ Experiences, Perceptions, and Attitudes towards Suicide and Suicide Prevention: A Scoping Review. Pharmacy 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allport, G.W. Attitudes.; Clark University Press: Worcester, MA, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmedani, B.K.; Simon, G.E.; Stewart, C.; Beck, A.; Waitzfelder, B.E.; Rossom, R.; Lynch, F.; Owen-Smith, A.; Hunkeler, E.M.; Whiteside, U.; et al. Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moose, J.; Branham, A. Pharmacists as Influencers of Patient Adherence. Pharmacy Times Oncology Edition 2014, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rukundo, G.Z.; Wakida, E.K.; Maling, S.; Kaggwa, M.M.; Sserumaga, B.M.; Atim, L.M.; Atuhaire, C.D.; Obua, C. Knowledge, attitudes, and experiences in suicide assessment and management: a qualitative study among primary health care workers in southwestern Uganda. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimollahi, M. An investigation of nursing students’ experiences in an Iranian psychiatric unit. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 19, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The, P.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, L.; Voracek, M.; Yousef, S.; Galadari, A.; Yammahi, S.; Sadeghi, M.-R.; Eskin, M.; Dervic, K. Suicidal behavior and attitudes among medical students in the United Arab Emirates. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention & Suicide Prevention 2013, 34, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskin, M.; Voracek, M.; Stieger, S.; Altinyazar, V. A cross-cultural investigation of suicidal behavior and attitudes in Austrian and Turkish medical students. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2011, 46, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, P.; Terzoni, S.; Ruta, F.; Poggi, A.D.; Destrebecq, A.; Gambini, O.; D’Agostino, A. Nursing students’ attitudes towards suicide and suicidal patients: A multicentre cross-sectional survey. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 109, 105258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacchero Vedana, K.G.; Guidorizzi Zanetti, A.C. Attitudes of nursing students toward to the suicidal behavior. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem (RLAE) 2019, 27, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botega, N.J.; Reginato, D.G.; da Silva, S.V.; Cais, C.F.; Rapeli, C.B.; Mauro, M.L.; Cecconi, J.P.; Stefanello, S. Nursing personnel attitudes towards suicide: the development of a measure scale. Braz J Psychiatry 2005, 27, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavalidou, K. Suicidal thoughts and attitudes towards suicide among medical and psychology students in Greece. Suicidology Online 2013, 4, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Domino, G.; Gibson, L.; Poling, S.; Westlake, L. Students’ attitudes towards suicide. Social psychiatry 1980, 15, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, N.; Kilgariff, J.K. Should suicide risk assessment be embedded in undergraduate dental curricula? Br. Dent. J. 2023, 234, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herron, J.; Ticehurst, H.; Appleby, L.; Perry, A.; Cordingley, L. Attitudes toward suicide prevention in front-line health staff. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2001, 31, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, D.W. Patient suicide: model for medical student teaching and mourning. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 1979, 1, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lappann Botti, N.C.; Costa de Araújo, L.M.; Costa, E.E.; de Almeida Machado, J.S. Nursing students attitudes across the suicidal behavior. Investigacion & Educacion en Enfermeria 2015, 33, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Narváez, M.L.; Escobar-Chan, Y.M.; Sánchez de la Cruz, J.P.; Tovilla-Zárate, C.A.; Juárez-Rojop, I.E.; Fresan, A.; González-Castro, T.B.; Montanee-Sandoval, A.C.; Suarez-Méndez, S. Differences in attitude toward prevention of suicide between nursing and medicine students: A study in Mexican population. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2020, 34, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques Moraes, S.; Magrini, D.F.; Guidorizzi Zanetti, A.C.; dos Santos, M.A.; Giacchero Vedana, K.G. Attitudes and associated factors related to suicide among nursing undergraduates. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem 2016, 29, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öz, F.; Turgut Atak, N.; Meriç, M. Nursing students’ attitudes toward death and stigma toward individuals who attempt suicide. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 1728–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterham, P.J.; Calear, A.L.; Christensen, H. The Stigma of Suicide Scale. Psychometric properties and correlates of the stigma of suicide. Crisis 2013, 34, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, P.; Reker, G.; Gesser, G. Death attitude profile–revised: a multidimensional measure of attitudes death; Neimeyer, R.A., Ed.; Taylor &Francis, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Poreddi, V.; Anjanappa, S.; Reddy, S. Attitudes of under graduate nursing students to suicide and their role in caring of persons with suicidal behaviors. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2021, 35, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.K.; Long, A.; Huang, X.Y.; Chiang, C.Y. A quasi-experimental investigation into the efficacy of a suicide education programme for second-year student nurses in Taiwan. J Clin Nurs 2011, 20, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedana, K.G.G.; Pereira, C.C.M.; Dos Santos, J.C.; Ventura, C.; Moraes, S.M.; Miasso, A.I.; Zanetti, A.C.G.; Borges, T.L. The meaning of suicidal behaviour from the perspective of senior nursing undergraduate students. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arafat, S.M.Y.; Hussain, F.; Hossain, M.F.; Islam, M.A.; Menon, V. Literacy and stigma of suicide in Bangladesh: Scales validation and status assessment among university students. Brain Behav 2022, 12, e2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajracharya, J.; Bhandari, N.; Chalise, P.; Tiwari, D. Perception Regarding Care of Attempted Suicide Patients among Nursing Students in Kathmandu University School of Medical Sciences. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. (KUMJ) 2020, 18, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.I.; Batterham, P.; Christensen, H.; Galletly, C. Suicide literacy, suicide stigma and help-seeking intentions in Australian medical students. Australas Psychiatry 2014, 22, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calear, A.L.; Batterham, P.J.; Christensen, H. The literacy of suicide scale: Psychometric properties and correlates of suicide literacy. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C.J.; Deane, F.P.; Ciarrochi, J.; Rickwood, D. Measuring Help-Seeking Intentions: Properties of the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire. Canadian Journal of Counselling 2005, 39, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cryer, R.E.M.; Calear, A.L.; Batterham, P.J.; Patel, S.R. Suicide, mental, and physical health condition stigma in medical students. Death Stud. 2020, 44, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaoka, D.A.; Fullerton, C.S.; Benedek, D.M.; Gifford, R.; Nam, T.; Ursano, R.J. Medical students’ responses to an inpatient suicide: opportunities for education and support. Acad. Psychiatry 2007, 31, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mospan, C.M.; Gillette, C. Student Pharmacists’ Attitudes Toward Suicide and the Perceived Role of Community Pharmacists in Suicidal Ideation Assessment. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, 7588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neimeyer, R.A.; Diamond, R.J. Suicide management skills and the medical student. J. Med. Educ. 1983, 58, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Batterham, P.J.; Calear, A.L.; Cryer, R. Predictors of Comfort and Confidence Among Medical Students in Providing Care to Patients at Risk of Suicide. Acad. Psychiatry 2016, 40, 919–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterham, P.J.; Calear, A.L.; Christensen, H. Correlates of suicide stigma and suicide literacy in the community. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2013, 43, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.J.; Smillie, L.D.; Corr, P.J. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Mini-IPIP five-factor model personality scale. Personality and Individual Differences 2010, 48, 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskin, R.; Terry, H. A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1988, 54, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, R.; Kawanishi, C.; Yamada, T.; Hasegawa, H.; Ikeda, H.; Kato, D.; Furuno, T.; Kishida, I.; Hirayasu, Y. Knowledge and attitude towards suicide among medical students in Japan: preliminary study. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 60, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheckel, M.M.; Nelson, K.A. An interpretive study of nursing students’ experiences of caring for suicidal persons. J. Prof. Nurs. 2014, 30, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.K.; Long, A.; Chiang, C.Y.; Wu, M.K.; Yao, Y. The psychological processes voiced by nursing students when caring for suicidal patients during their psychiatric clinical practicum: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedana, K.G.G.; Dos Santos, J.C.; Zortea, T.C. The Meaning of Suicidal Behaviour for Portuguese Nursing Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, S.; Shah, N.E.; Sivachandran, S.; Shahruddin, I.; Ismail, N.N.S.; Mohan, L.D.; Kamaluddin, M.R.; Nawi, A.M. Attitude Towards Suicide and Help-Seeking Behavior Among Medical Undergraduates in a Malaysian University. Acad. Psychiatry 2021, 45, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renberg, E.S.; Jacobsson, L. Development of a questionnaire on attitudes towards suicide (ATTS) and its application in a Swedish population. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2003, 33, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, F.P.; Skogstad, P.; Williams, M.W. Impact of attitudes, ethnicity and quality of prior therapy on New Zealand male prisoners’ intentions to seek professional psychological help. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 1999, 21, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, F.P.; Todd, D.M. Attitudes and Intentions to Seek Professional Psychological Help for Personal Problems or Suicidal Thinking. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy 1996, 10, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Boyle, M.; Fielder, C. Empathetic attitudes of undergraduate paramedic and nursing students towards four medical conditions: a three-year longitudinal study. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, e14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christison, G.W.; Haviland, M.G.; Riggs, M.L. The medical condition regard scale: measuring reactions to diagnoses. Acad Med 2002, 77, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohn, J.H. The Experiences of Nursing Students While Caring for Patients at Risk for Suicide: A Descriptive Phenomenology. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2022, 43, E91–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawgood, J.L.; Krysinska, K.E.; Ide, N.; De Leo, D. Is suicide prevention properly taught in medical schools? Med. Teach. 2008, 30, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, R.; Weingartner, L.A.; Brikker, E.; Shaw, M.A.; Shreffler, J.; O’Connor, S.S. Improving Medical Student Attitudes Toward Suicide Prevention Through a Patient Safety Planning Clerkship Initiative. Acad. Psychiatry 2022, 46, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domino, G.; Takahashi, Y. Attitudes toward suicide in Japanese and American medical students. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1991, 21, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emul, M.; Uzunoglu, Z.; Sevinç, H.; Güzel, C.; Yilmaz, C.; Erkut, D.; Arikan, K. The attitudes of preclinical and clinical Turkish medical students toward suicide attempters. Crisis 2011, 32, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskin, M. The effects of religious versus secular education on suicide ideation and suicidal attitudes in adolescents in Turkey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2004, 39, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskin, M. Social reactions of Swedish and Turkish adolescents to a close friend’s suicidal disclosure. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1999, 34, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etzersdorfer, E.; Vijayakumar, L.; Schöny, W.; Grausgruber, A.; Sonneck, G. Attitudes towards suicide among medical students: comparison between Madras (India) and Vienna (Austria). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1998, 33, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekstra RFW, K.A. Attitudes towards suicide: the development of a suicide-attitude questionnaire (SUIATT). In Suicide and its prevention, the role of attitude and imi tation; Diekstra, R.F.W., Maris, R., Platt, S., Schmidtke, A., Sonneck, G., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, 1989; pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Wallin, U.; Runeson, B. Attitudes towards suicide and suicidal patients among medical students. Eur. Psychiatry 2003, 18, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebhinani, N.; Mamta, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Gaikwad, A.D.; Tamphasana, L. Nursing students’ attitude toward suicide prevention. Ind Psychiatry J 2013, 22, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.K.; Long, A.; Chiang, C.Y.; Chou, M.H. A theory to guide nursing students caring for patients with suicidal tendencies on psychiatric clinical practicum. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 38, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobodanka Bašić, B.L.; Jović, Sladjana; Petrović, Branislav; Kocić, Biljana; Jovanović, Jovica. Suicide Knowledge and Attitudes among Medical Students of the University of NIŠ. Facta Universitatis, Series: Medicine and Biology 2004, 11, 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Öncü, B. Çiğdemİhan, İnci ÖzgürSayl, Işk. Attitudes of Medical Students, General Practitioners, Teachers, and Police Officers Toward Suicide in a Turkish Sample. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention 2008, 29, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salander-Renberg, E.; Jacobson, L. Development of a questionnaire on attitudes toward suicide (ATTS) and its application in a Swedish population. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior 2003, 33, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan-Ko, S.; Long, A.; Xuan-Yi, H.; Chun-Ying, C. A quasi-experimental investigation into the efficacy of a suicide education programme for second-year student nurses in Taiwan. Journal of clinical nursing (john wiley & sons, inc.) 2011, 20, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.K.; Long, A.; Boore, J. The attitudes of casualty nurses in Taiwan to patients who have attempted suicide. J Clin Nurs 2007, 16, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, M.N.; Robinson, J.D.; McKeirnan, K.C.; Akers, J.M.; Buchman, C.R. Training Student Pharmacists in Suicide Awareness and Prevention. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, ajpe847813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelvik, A.; Eldridge, A.; Furnari, M.; Hoeflich, H.; Chen, J.I.; Roth, B.; Black, W. A Peer-to-Peer Suicide Prevention Workshop for Medical Students. MedEdPORTAL 2022, 18, 11241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a theory of planned behavior questionnaire; 2019.

- Pothireddy, N.; Lavigne, J.E.; Groman, A.S.; Carpenter, D.M. Developing and evaluating a module to teach suicide prevention communication skills to student pharmacists. Curr Pharm Teach Learn 2022, 14, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavigne, J.E.; King, D.; Lu, N.; Knox, K.L.; Kemp, J.E. Pharmacist and Pharmacy Staff Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Suicide and Suicide Prevention After a National VA Training Program. Value Health 2011, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamero, C.; Walsh, L.; Otero-Perez, G. Use of the film The Bridge to augment the suicide curriculum in undergraduate medical education. Acad. Psychiatry 2014, 38, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, S.; Beh, P.S.; Wong, P.W. Attitudes towards suicide following an undergraduate suicide prevention module: experience of medical students in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med. J. 2013, 19, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeirnan, K.C.; MacCamy, K.L.; Robinson, J.D.; Ebinger, M.; Willson, M.N. Implementing Mental Health First Aid Training in a Doctor of Pharmacy Program. Am J Pharm Educ 2023, 87, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modgill, G.; Patten, S.B.; Knaak, S.; Kassam, A.; Szeto, A.C.H. Opening Minds Stigma Scale for Health Care Providers (OMS-HC): Examination of psychometric properties and responsiveness. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litteken, C.; Sale, E. Long-Term Effectiveness of the Question, Persuade, Refer (QPR) Suicide Prevention Gatekeeper Training Program: Lessons from Missouri. Community Ment Health J 2018, 54, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellbeing, N.C.f.M. Mental health first aid. Available online: https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/our-work/mental-health-first-aid/ (accessed on 24th February 2024).

- Carpenter, D.M.; Stover, A.N.; Harris, S.C.; Anksorus, H.; Lavigne, J.E. Impact of a Brief Suicide Prevention Training with an Interactive Video Case Assessment on Student Pharmacist Outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ 2023, 87, 100093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, P.A.; Brown, C.H.; Inman, J.; Cross, W.; Schmeelk-Cone, K.; Guo, J.; Pena, J.B. Randomized trial of a gatekeeper program for suicide prevention: 1-year impact on secondary school staff. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 2008, 76, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siau, C.S.; Wee, L.H.; Ibrahim, N.; Visvalingam, U.; Wahab, S. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Attitudes Toward Suicide Questionnaire Among Healthcare personnel in Malaysia. Inquiry 2017, 54, 46958017707295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre, F.S.P. Suicide Prevention for Pharmacy. Available online: https://intheforefront.org/suicide-prevention-for-pharmacy-professionals/ (accessed on July 28, 2020 ).

- Lopez-Morinigo, J.D.; Escribano-Martinez, A.S.; Ruiz-Ruano, V.G.; Mata-Iturralde, L.; Sanchez-Alonso, S.; Munoz-Lorenzo, L.; Baca-Garcia, E.; David, A. Randomised controlled trial of metacognitive training compared with psychoeducation in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: effects on insight. Schizophr. Bull. 2020, 46, S47–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.; Tsang, R.S.W.; Morgan, A.; Jamieson, F.B.; Ulanova, M. Invasive disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type a in Northern Ontario First Nations communities. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 60, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatne, M.; Nåden, D. Experiences that inspire hope: Perspectives of suicidal patients. Nursing Ethics 2016, 25, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbuto, D.; Berardelli, I.; Sarubbi, S.; Rogante, E.; Sparagna, A.; Nigrelli, G.; Lester, D.; Innamorati, M.; Pompili, M. Suicide-Related Knowledge and Attitudes among a Sample of Mental Health Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grad, O.T.; Zavasnik, A.; Groleger, U. Suicide of a patient: gender differences in bereavement reactions of therapists. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1997, 27, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (WHO), W.H.O. Policy Brief: COVID-19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/UN-Policy-Brief-COVID-19-and-mental-health (accessed on.

- Carmona-Navarro, M.C.; Pichardo-Martínez, M.C. Attitudes of nursing professionals towards suicidal behavior: influence of emotional intelligence. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2012, 20, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamis, D.A.; Underwood, M.; D’Amore, N. Outcomes of a Suicide Prevention Gatekeeper Training Program Among School Personnel. Crisis 2017, 38, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbey, K.J.; Madsen, C.H., Jr.; Polland, R. Short-term suicide awareness curriculum. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1989, 19, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aseltine, R.H.; James, A.; Schilling, E.A.; Glanovsky, J. Evaluating the SOS suicide prevention program: a replication and extension. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bean, G.; Baber, K.M. Connect: an effective community-based youth suicide prevention program. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2011, 41, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, T.L.; Witt, J.; Abraibesh, N. Does a gatekeeper suicide prevention program work in a school setting? Evaluating training outcome and moderators of effectiveness. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2010, 40, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.; Smith, A.R.; Dodd, D.R.; Covington, D.W.; Joiner, T.E. Suicide-Related Knowledge and Confidence Among Behavioral Health Care Staff in Seven States. Psychiatr. Serv. 2016, 67, 1240–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramberg, I.L.; Di Lucca, M.A.; Hadlaczky, G. The Impact of Knowledge of Suicide Prevention and Work Experience among Clinical Staff on Attitudes towards Working with Suicidal Patients and Suicide Prevention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramberg, I.L.; Wasserman, D. Benefits of implementing an academic training of trainers program to promote knowledge and clarity in work with psychiatric suicidal patients. Arch Suicide Res 2004, 8, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.; Krishna, M.; Rajendra, R.G.; Keenan, P. Nurses attitudes and beliefs to attempted suicide in Southern India. Journal of Mental Health 2015, 24, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, J.; Mackay, B.; McGivern, M.J. The potential of sim ulation to enhance nursing students’ preparation for suicide risk assessment: A review. Open Journal of Nursing 2017, 7, 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Giacchero Vedana, K.G.; Magrini, D.F.; Zanetti, A.C.G.; Miasso, A.I.; Borges, T.L.; Dos Santos, M.A. Attitudes towards suicidal behaviour and associated factors among nursing professionals: A quantitative study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2017, 24, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedana, K.G.G.; Magrini, D.F.; Miasso, A.I.; Zanetti, A.C.G.; de Souza, J.; Borges, T.L. Emergency Nursing Experiences in Assisting People With Suicidal Behavior: A Grounded Theory Study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2017, 31, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joiner, T.E., Jr.; Hollar, D.; Kimberly Van, O. ON BUCKEYES, GATORS, SUPER BOWL SUNDAY, AND THE MIRACLE ON ICE: “PULLING TOGETHER” IS ASSOCIATED WITH LOWER SUICIDE RATES. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 2006, 25, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Hwang, I.; Sampson, N.; Kessler, R.C.; Angermeyer, M.; Beautrais, A.; Borges, G.; Bromet, E.; Bruffaerts, R.; de Girolamo, G.; et al. Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med 2009, 6, e1000123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AG, T. Psychiatric care of people at risk of committing suicide: Narrative interviews with registered nurses, physicians, patients and their relatives; Umeå University: Sweden, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsson, M.; Sunbring, Y.; Winell, I.; Asberg, M. Nurses’ attitudes to attempted suicide patients. Scand J Caring Sci 1997, 11, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Cais, C.F.; da Silveira, I.U.; Stefanello, S.; Botega, N.J. Suicide prevention training for professionals in the public health network in a large Brazilian city. Arch Suicide Res 2011, 15, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzouni C, N.K. Nurses’ attitudes towards attempted suicide. Health Science Journal 2013, 7, 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, S.E.; Stoll, K.A. Attitudes of medical and nursing staff towards self-poisoning patients in a London hospital. Int J Nurs Stud 1977, 14, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osafo, J.; Knizek, B.L.; Akotia, C.S.; Hjelmeland, H. Attitudes of psychologists and nurses toward suicide and suicide prevention in Ghana: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 2012, 49, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norheim, A.B.; Grimholt, T.K.; Loskutova, E.; Ekeberg, O. Attitudes toward suicidal behaviour among professionals at mental health outpatient clinics in Stavropol, Russia and Oslo, Norway. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi, Y.; Kurosawa, H.; Morimura, H.; Hatta, K.; Thurber, S. Attitudes of Japanese nursing personnel toward patients who have attempted suicide. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011, 33, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, K.E.; Hawton, K.; Fortune, S.; Farrell, S. Attitudes and knowledge of clinical staff regarding people who self-harm: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 139, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wimsatt, L.A.; Schwenk, T.L.; Sen, A. Predictors of Depression Stigma in Medical Students: Potential Targets for Prevention and Education. Am J Prev Med 2015, 49, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramberg, I.L.; Wasserman, D. Suicide-preventive activities in psychiatric care: evaluation of an educational programme in suicide prevention. Nord J Psychiatry 2004, 58, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barney, L.J.; Griffiths, K.M.; Jorm, A.F.; Christensen, H. Stigma about Depression and its Impact on Help-Seeking Intentions. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2006, 40, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F.; Wright, A.; Morgan, A.J. Where to seek help for a mental disorder? National survey of the beliefs of Australian youth and their parents. Med J Aust 2007, 187, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, B.G.; Highet, N.J.; Hickie, I.B.; Davenport, T.A. Exploring the perspectives of people whose lives have been affected by depression. Med J Aust 2002, 176, S69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.M.; Epstein, S.A.; Weinfurt, K.P.; DeCoster, J.; Qu, L.; Hannah, N.J. Predictors of primary care physicians’ self-reported intention to conduct suicide risk assessments. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2012, 39, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, M.D.; Franks, P.; Duberstein, P.R.; Vannoy, S.; Epstein, R.; Kravitz, R.L. Let’s not talk about it: suicide inquiry in primary care. Ann. Fam. Med. 2007, 5, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutting, P.A.; Dickinson, L.M.; Rubenstein, L.V.; Keeley, R.D.; Smith, J.L.; Elliott, C.E. Improving detection of suicidal ideation among depressed patients in primary care. Ann. Fam. Med. 2005, 3, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michail, M.; Tait, L. Exploring general practitioners’ views and experiences on suicide risk assessment and management of young people in primary care: a qualitative study in the UK. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, E. Health care in contemporary Japanese religions. In Healing and Restoring—Health and Medicine in the World’s Religious Traditions; LE, S., Ed.; Macmillan: New York, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, Y. Culture and suicide: from a Japanese psychiatrist’s perspective. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1997, 27, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thimmaiah, R.; Poreddi, V.; Ramu, R.; Selvi, S.; Math, S.B. Influence of Religion on Attitude Towards Suicide: An Indian Perspective. Journal of Religion and Health 2016, 55, 2039–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoib, S.; Armiya’u, A.Y.; Nahidi, M.; Arif, N.; Saeed, F. Suicide in Muslim world and way forward. Health Sci Rep 2022, 5, e665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), G.o.I. Census of India. Available online: https://censusindia.gov.in/census.website/data/census-tables (accessed on.

- Colucci, E.; Martin, G. Religion and spirituality along the suicidal path. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2008, 38, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.; Kumar, S.; Pattanayak, R.D.; Dhawan, A.; Sagar, R. (De-) criminalization of attempted suicide in India: A review. Ind Psychiatry J 2014, 23, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, U.; Aspegren, K. Pedagogical methods and affect tolerance in medical students. Med Educ 1999, 33, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JC, S. Suicide: can we prevent the most mysterious act of the human being? Rev Port Enferm Saúde Mental 2015, 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.; Standen, P.; Nazir, S.; Noon, J.P. Nurses’ and doctors’ attitudes towards suicidal behaviour in young people. Int J Nurs Stud 2000, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baykan, N.; Arslantürk, G.; Durukan, P. Desensitizing Effect of Frequently Witnessing Death in an Occupation: A Study With Turkish Health-Care Professionals. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying 2020, 84, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukouvalas, E.; El-Den, S.; Murphy, A.L.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; O’Reilly, C.L. Exploring Health Care Professionals’ Knowledge of, Attitudes Towards, and Confidence in Caring for People at Risk of Suicide: a Systematic Review. Arch Suicide Res 2020, 24, S1–s31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterman, P. Even Accidental Counsellors Have to Be Brave. Australian Pharmacist 2010, 29, 1015. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, A. Suicide prevention. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 230, 115–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskin, M.; Baydar, N.; El-Nayal, M.; Asad, N.; Noor, I.M.; Rezaeian, M.; Abdel-Khalek, A.M.; Al Buhairan, F.; Harlak, H.; Hamdan, M.; et al. Associations of religiosity, attitudes towards suicide and religious coping with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in 11 muslim countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siau, C.S.; Wee, L.H.; Wahab, S.; Visvalingam, U.; Yeoh, S.H.; Halim, N.A.A.; Ibrahim, N. The influence of religious/spiritual beliefs on Malaysian hospital healthcare workers’ attitudes towards suicide and suicidal patients: a qualitative study. J. Res. Nurs. 2021, 26, 723–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, R.E.; Alonzo, D. Religion and Suicide: New Findings. Journal of Religion and Health 2018, 57, 2478–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppens, E.; Van Audenhove, C.; Iddi, S.; Arensman, E.; Gottlebe, K.; Koburger, N.; Coffey, C.; Gusmão, R.; Quintão, S.; Costa, S.; et al. Effectiveness of community facilitator training in improving knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in relation to depression and suicidal behavior: Results of the OSPI-Europe intervention in four European countries. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 165, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, A.N.; Lavigne, J.E.; Carpenter, D.M. A Scoping Review of Suicide Prevention Training Programs for Pharmacists and Student Pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ 2023, 87, ajpe8917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.; Mehta, R.; Dave, K.; Chaudhary, P. Effectiveness of gatekeepers’ training for suicide prevention program among medical professionals and medical undergraduate students of a medical college from Western India. Industrial Psychiatry Journal 2021, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, S.-L. Evalua&on of a gatekeeper training program as suicide intervention training for medical students: A randomized controlled trial. The University of Manitoba 2015.

- Rallis, B.A.; Esposito-Smythers, C.; Disabato, D.J.; Mehlenbeck, R.S.; Kaplan, S.; Geer, L.; Adams, R.; Meehan, B. A brief peer gatekeeper suicide prevention training: Results of an open pilot trial. J Clin Psychol 2018, 74, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebhinani, N.; Kuppili, P.P.; Paul, K. Effectiveness of Brief Educational Training on Medical Students’ Attitude toward Suicide Prevention. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2020, 11, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, A.; Chaudhary, N.; Murphy, J.; Lok, B.; Waller, J.; Buckley, P.F. The Use of Simulation to Teach Suicide Risk Assessment to Health Profession Trainees-Rationale, Methodology, and a Proof of Concept Demonstration with a Virtual Patient. Academic psychiatry 2015, 39, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, C.; Waalen, J.K.; Haelstromm, E. Many helping hearts: an evaluation of peer gatekeeper training in suicide risk assessment. Death Stud 2003, 27, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tompkins, T.L.; Witt, J. The short-term effectiveness of a suicide prevention gatekeeper training program in a college setting with residence life advisers. J Prim Prev 2009, 30, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, W.; Matthieu, M.M.; Lezine, D.; Knox, K.L. Does a brief suicide prevention gatekeeper training program enhance observed skills? Crisis 2010, 31, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, D.J.; Servaty-Seib, H.; Miles, N.; Lee, J.Y.; Morris, C.A.; Prieto-Welch, S.L.; et al. The impact of gatekeeper training for suicide prevention on university resident assistants. J Coll Couns 2013, 16, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimini, M.D.; Rivero, E.M.; Bernier, J.E.; Stanley, J.A.; Murray, A.D.; Anderson, D.A.; Wright, H.R.; Bapat, M. Implementing an audience-specific small-group gatekeeper training program to respond to suicide risk among college students: a case study. J Am Coll Health 2014, 62, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cwik, M.F.; Tingey, L.; Wilkinson, R.; Goklish, N.; Larzelere-Hinton, F.; Barlow, A. Suicide Prevention Gatekeeper Training: Can They Advance Prevention in Indian Country? Arch Suicide Res 2016, 20, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NA, I. Outcomes of a suicide prevention gatekeeper training on a university campus. J Coll Stud Dev 2011, 52, 350–363. [Google Scholar]

- Matthieu, M.M.; Chen, Y.; Schohn, M.; Lantinga, L.J.; Knox, K.L. Educational preferences and outcomes from suicide prevention training in the Veterans Health Administration: one-year follow-up with healthcare employees in Upstate New York. Mil Med 2009, 174, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capp, K.; Deane, F.P.; Lambert, G. Suicide prevention in Aboriginal communities: application of community gatekeeper training. Aust N Z J Public Health 2001, 25, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, W.; Matthieu, M.M.; Cerel, J.; Knox, K.L. Proximate outcomes of gatekeeper training for suicide prevention in the workplace. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2007, 37, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, M.; Elias, B.; Katz, L.Y.; Belik, S.-L.; Deane, F.P.; Enns, M.W.; Sareen, J. Gatekeeper Training as a Preventative Intervention for Suicide: A Systematic Review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2009, 54, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, B.F.; Hides, L.; Kisely, S.; Ranmuthugala, G.; Nicholson, G.C.; Black, E.; Gill, N.; Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan, S.; Toombs, M. The need for a culturally-tailored gatekeeper training intervention program in preventing suicide among Indigenous peoples: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchener, B.A.; Jorm, A.F. Mental health first aid training for the public: evaluation of effects on knowledge, attitudes and helping behavior. BMC Psychiatry 2002, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aseltine, R.H.; DeMartino, R. An outcome evaluation of the SOS Suicide Prevention Program. American journal of public health 2004, 94, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P, R. Review of the Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training program (ASIST): Rationale, evaluation results, and directions for future research. 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Author (year); countrya | Objectives | Study design and instruments | N; Health programsƵ | Year of studyƵ | Population characteristics (mean age; gender) Ƶ | Personal experience of mental health issues and suicideƵ | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KnowledgeƵ | AttitudeƵ | |||||||

| Amiri et al. (2013); UAE [25] |

|

|

115; Medical |

|

20.7y; 51.9% female |

|

NA |

|

| Ferrara et al. (2022); Italy [27] |

|

|

409; Nursing |

|

22y; 63.1% female |

|

|

|

| Giacchero Vedana et al. (2019); Brazil [28] |

|

|

111; Nursing |

|

22.6y; 86.5% female |

|

|

|

| Kavalidou et al. (2013); Greece [30] |

|

|

105; Medical |

|

22.4y, 61.0% female |

|

NA |

|

| Kelly et al. (2023); UK [32] |

|

|

30; Dental |

|

NA; 67% female | NA |

|

|

| Krueger (1979); US [34] |

|

|

6; Medical | NA | NA; NA | NA |

|

|

| Lappann Botti et al. (2015); Brazil [35] |

|

|

58; Nursing |

|

21-25y; 89.7% female | NA | Factor 2 by item: 1.2: low confidence in dealing with suicidal person |

|

| López-Narváez et al. (2020); Mexico [36] |

|

|

355; Medical, nursing | NA | 20.47y; 61.4% female |

|

NA |

|

| Marques Moraes et al. (2016); Brazil [37] |

|

|

244; Nursing |

|

42.2% 21.0-22.9y; 86.5% female |

|

|

|

| Öz et al. (2022); Turkey [38] |

|

560; Nursing |

|

19.3y; 63.7% female |

|

NA |

|

|

| Poreddi et al. (2021); India [41] |

|

|

223; Nursing |

|

19.8y; 89.7% female |

|

NA |

|

| Vedana et al. (2018); Brazil [43] |

|

|

30; Nursing |

|

87% <25y; 87% female | NA | NA |

|

| Arafat et al. (2022); Bangladesh [44] |

|

|

162; Medical | NA | 18-27y; NA | NA |

|

|

| Bajracharya et al. (2020); Nepal [45] |

|

|

103; Nursing |

|

19.8y; NA |

|

NA |

|

| Chan et al. (2014); Australia [46] |

|

219; Medical |

|

24.6y; 53.8% female | NA |

|

|

|

| Cryer et al. (2020); Australia [49] |

|

|

116; Medical |

|

25.02y; 58% female | NA | NA |

|

| Hamaoka et al. (2007); US [50] |

|

|

12; Medical | NA | NA; NA | NA | NA |

|

| Mospan et al. (2020); US [51] |

|

|

73; Pharmacist |

|

NA; 66% female |

|

|

|

| Neimeyer et al. (1983); US [52] |

|

|

141; Medical |

|

25.3y; 27.4 % female | NA |

|

NA |

| Patel et al. (2016); Australia [53] |

|

116; Medical |

|

25.0y; NA |

|

|

NA | |

| Sato et al. (2006); Japan [57] |

|

|

160; Medical |

|

21.5y; 41.2% female | NA |

|

|

| Scheckel et al. (2014); US [58] |

|

|

11; Nursing |

|

21-26y; 100% female | NA |

|

|

| Sun et al. (2020) , Taiwan [59] |

|

|

22; Nursing |

|

20-23y; 95.5% female | NA |

|

|

| Vedana et al. (2022); Portugal [60] |

|

|

13; Nursing |

|

53.8% 22y; 92.3% female |

|

NA |

|

| Wahab et al. (2021); Malaysia [61] |

|

290; Medical |

|

22.4y; 49.7% female |

|

NA |

|

|

| Williams et al. (2015); Australia [65] |

|

|

554; Paramedic, paramedic/nursing |

|

83% <25y; 69.1% female | NA | NA |

|

| Zohn et al. (2022); US [67] |

|

|

14; Nursing |

|

22-43y; 92.9% female | NA |

|

|

| Hawgood et al. (2008); Australia [68] |

|

|

373; Medical |

|

25.9y; 55% female | NA |

|

|

| Price et al. (2022); US [69] |

|

|

360; Medical |

|

NA; NA | NA |

|

|

| Domino et al. (1991); US, Japan [70] |

|

|

|

NA |

|

|

NA |

|

| Emul et al. (2011); Turkey [71] |

|

|

234; Medical |

|

NA; NA | NA | NA |

|

| Eskin et al. (2011); Austria, Turkey [26] |

|

|

|

|

|

NA |

|

|

| Etzersdorfer et al. (1998); India, Austria [74] |

|

|

NA; Medical | NA |

|

|

NA |

|

| Wallin et al. (2003); Sweden [76] |

|

|

306; Medical |

|

|

|

NA |

|

| Nebhinani et al. (2013); India [77] |

|

|

308; Nursing | NA | 20y; 95.1% female |

|

|

|

| Sun et al. (2019); Taiwan [78] |

|

|

22; Nursing | NA | 20-23y; 95.5% female |

|

|

|

| Slobodanka Bašić et al. (2004); Serbia [79] |

|

|

150; Medical |

|

NA; 58.7% female | NA |

|

|

| Oncü et al. (2008); Turkey [80] |

|

|

41; Medical | NA | 23.3y; 46.3% female | NA | NA |

|

| Fan-Ko et al. (2011); Taiwan [82] |

|

|

79; Nursing |

|

26.8y; 97.7% female |

|

|

|

| Willson et al. (2020); US [84] |

|

|

158; Pharmacists |

|

NA; 63% female |

|

|

NA |

| Hjelvik et al. (2022): US [85] |

|

|

273; Medical |

|

NA; NA | NA |

|

|

| Pothireddy et al. (2022); US [87] |

|

|

139; Pharmacist |

|

23.8y; NA |

|

|

|

| Retamero et al. (2014); US [89] |

|

|

180; Medical |

|

NA; NA | NA | NA |

|

| Yousuf et al. (2013); Hong Kong [90] |

|

|

22; Medical |

|

20-23y; 32% female |

|

NA |

|

| Mckeirnan et al. (2023); US [91] |

|

|

205; Pharmacist |

|

NA; NA |

|

|

|

| Carpenter et al. (2023); US [95] |

|

|

146; Pharmacist |

|

23.6y; 67% female |

|

|

NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).