1. Introduction

The emergence of the severe acute respiratory syndrome virus (SARS-CoV-2), which made COVID-19 a pandemic, has drawn world attention to hygiene as the first line of defense in controlling infection. Likewise, to maintain healthy skin, washing your hands needs to be done as often as possible. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers act as antimicrobials and disinfectants by denaturing proteins in microbial plasma membranes and inactivating viruses (Lee et al., 2020). Therefore, alcohol-based sanitizers have been in great demand for centuries to prevent infection with pathogenic diseases (Hans et al., 2023). Using hand sanitizer in the form of liquid and gel preparations containing antiseptic alcohol can make hands dry and cause dehydration of the skin. Even excessive use of alcohol can increase the risk of inflammation in the digestive tract (Kao et al., 2023). In addition, the process of washing hands intensively can cause various changes in skin texture, such as easily irritating the skin and damaging the skin barrier. Irritation or long-term exposure to allergens can cause contact dermatitis (Tang et al., 2023). To overcome skin problems caused by the use of hand sanitizers made from alcohol antiseptics, and excessive hand washing frequency, it is necessary to prepare non-alcoholic hand sanitizers which have the function of being able to prevent the transmission of COVID-19, are effective in treating skin diseases, killing microbes and able to maintain healthy skin by keeping it clean. stay moist and smooth.

Non-alcoholic hand sanitizer lotions offer a variety of benefits, including time-saving capabilities, moisturizing, and are compatible with latex gloves. These products have been shown to be effective in reducing bacteria, and some formulations even outperform alcohol-based products (Suryavanshi et al., 2021). Abuga and Nyamwega (2021) highlights the advantages of non-alcoholic hand gel, namely that it does not dry out hands and can be used to wash and moisturize hands antiseptically. Sidauruk et al. (2021) also support this by showing the antibacterial potential of Sargassum plagyophillum extract in non-alcoholic hand sanitizer gel. Egner (2023) presents a natural alternative to alcohol-based hand sanitizers, with a non-alcoholic gel containing mandelic acid and essential oils, proven to have better antimicrobial activity and organoleptic properties. Research regarding natural sources from the sea as raw materials for hand sanitizers has also been reported. The hand sanitizer gel formulation containing mangrove leaf extract and patchouli oil is able to fight Staphylococcus aureus, with the highest inhibitory zone diameter of 25 mm (Fahreni et al., 2021). In addition, the hand sanitizer gel formulation using seaweed (Eucheuma spinosum) methanol extract shows antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus bacteria (Praselya, 2022). L. japonica extract hydrates the skin through the humectants and hydrocolloids it contains through physicochemical characteristic tests (Choi et al., 2013). Other research shows that melanin and concentrate of the seaweed Gelidium sp. are rich in antioxidant activity (Poulose et al., 2020). The combination of seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii) and jicama (Pachyrhizus erosus) in body lotion also has good properties for the skin (Pratama et al., 2020). When compared with green and red algae, the potential of brown algae as antimicrobial and antiviral is closely related to the high content of secondary metabolites phlorotannin (1% to 14% of dry algal biomass). Phlorotannin derivatives were found to be dominant in inhibiting the viral protein PLpro, which is responsible for processing viral proteins for multiplication (Maheswari and Babu, 2022). Fucoidant isolated from brown algae shows strong antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 by reducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, especially interleukins (Gunathilaka, 2023).

These studies collectively suggest that seaweed can be a valuable raw material in the formulation of hand sanitizer lotions for skin health. However, research regarding the specific use of brown seaweed (Scytosiphon lomentaria) as a non-alcoholic hand sanitizer is still limited. Further research is needed to explore the feasibility and effectiveness of S. lomentaria seaweed-based hand sanitizer lotions.

The use of S.lomentaria as a raw material in the production of safer, antibacterial hand sanitizer solution that help maintain the health and smoothness of the hands. The secondary bioactive content is related to the function of algae as antioxidants (Pradhan et al., 2021). This study aims to analyse microbial inhibitory ability and characteristics of S. lomentaria hand sanitizer lotion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The main ingredient used in this research is the algae Scytosiphon lomentaria found in the intertidal zone of Jolosutro Beach, Blitar Regency, Indonesia. The lotion preparations used included olive oil (Arabina Store, Indonesia), stearic acid (Biru Baru Official Store, Indonesia), beeswax (Cera Alba, Indonesia), triethanolamine (TEA) (Indonesia), distilled water, nipagin (Aahna Skincare, Indonesia), glycerin (Jas Chemical, Indonesia), and chitosan (Phy Edumedia, Indonesia). All of the other chemicals used in this study were analytical in nature.

2.1.1. Sample Preparation

Fresh algae, S. lomentaria, were collected and put in plastic bags and cool boxes, then transported to the Polytechnic of Marine and Fisheries Sidoarjo Quality Testing Laboratory and cleaned with running water. The samples were dried at room temperature (±26ºC) for 5-7 days. The dry samples were then cut into ±0.5 cm with scissors and blended, while the fresh samples were blended with the addition of distilled water (1:1) as a mixture for hand sanitizer lotion. The dry algae powder was frozen before being used for further tests. Phytochemical tests were carried out using the Harborne method (Harborne, 1995).

2.2. Method

Algae powder was tested for compound content, including phytochemical tests (Harborne, 1995), total phenol content (Kang et al., 2010) with modification, free radical scavenging activity (IC50) (Khalaf et al., 2008; Pinteus et al., 2017) with modifications, as well as antibacterial tests against gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus) and gram-negative (Escherichia coli) bacterial strains (Kantachumpoo and Chirapart, 2010).

2.2.1. Experimental Design

Hand sanitizer lotion preparations were divided into four treatment groups, including normal control (base lotion without the addition of algae), lotion with the addition of 20% algae, lotion with the addition of 30% algae, and lotion with the addition of 40% algae. The lotion preparations for each treatment group were tested for antibacterial activity for

Staphylococcus aureus and

Escherichia coli (Kantachumpoo and Chirapart, 2010), phytochemicals (Harborne, 1995), pH (Sayuti, 2015), adhesive power (Pujiastuti & Kristen, 2019), spread ability (Sayuti, 2015), homogeneity (Umarudin

et al., 2020), emulsion type (Olejnik and Goscianska, 2023), and hedonic (Kim

et al., 2017). The formulation of hand sanitizer lotion refers to research by Yanuarti et al. (2021) with modifications (

Table 1).

2.3. Analysis Data

The research design used was a completely randomized design (CRD). The research data were analyzed using parametric analysis in the form of an analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a confidence level of 95% and the DMRT (Duncan’s Multiple Range Test) further test with a confidence level of 95% to determine the magnitude of the influence between treatments and each treatment. Hedonic test parameters were carried out using non-parametric analysis in the form of the Kruskal-Wallis’ test with a confidence level of 95% and the Mann-Whitney test with a confidence level of 95% to determine whether there were real differences between treatment groups.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Antibacterial Activity of Lotion and Algae Porridge

Antibacterial activity testing uses gram-negative (

E. coli) and gram-positive (

S. aureus) bacteria. The results of the inhibitory zone test for pathogenic bacteria for

Scytosiphon lomentaria seaweed lotion and porridge preparations can be seen in

Table 2. The highest inhibition zone for the

E. coli pathogenic bacteria was 6.33 ± 1.02 mm in the 1 mg/ml

S. lomentaria algae porridge treatment group (

Table 2). The lotion with the addition of

S. lomentaria algae had the best zone of inhibition against the

E. coli pathogenic bacteria, with a value of 6.30 ± 0.64 mm in the 40% seaweed addition treatment. The higher the concentration of algae porridge added to the lotion preparation, the greater the diameter of the inhibition zone against

E. coli gram-negative pathogenic bacteria. The inhibitory strength of

E. coli pathogenic bacteria from all groups was classified as moderate for the lotion treatment with the addition of 30%, 40% algae, and algae porridge, and was classified as low for the lotion treatment without the addition of algae and lotion with the addition of 20% algae. The lotion treatment group with the addition of 30% algae was not significantly different from the lotion with the addition of 40% algae and algae porridge, but it was significantly different from the lotion treatment group without the addition of algae and the lotion with the addition of 20% algae. The strength of antibacterial antibiotics in a sample is as follows: An inhibitory area of 20 mm or more means a very strong inhibitory power; an inhibitory area of 10-20 mm means strong; an inhibitory area of 5-10 mm means moderate; and an inhibitory area of 5 mm or less means weak (Scania and Chasani, 2021). Factors that influence the size of the inhibition area (clear zone) are the sensitivity of the organism, culture medium, incubation conditions, and agar diffusion speed. Agar diffusion is influenced by the concentration of microorganisms, media composition, incubation temperature, and incubation time (Radiena

et al., 2019). Apart from that, adding algae to lotion can increase the effectiveness of inhibition against pathogenic bacteria because it contains secondary metabolite compounds such as phenols, tannins, flavonoids, and saponins (Xu

et al., 2017).

Table 2 shows that the zone of inhibition against the

S. aureus pathogenic bacteria was highest in the

S. lomentaria algae porridge treatment group with a concentration of 1 mg/ml and a value of 7.18 ± 0.63 mm. The lotion treatment without the addition of algae had the lowest inhibitory power, with a value of 5.25 ± 2.36 mm. The inhibitory power of the lotion in the form of the diameter of the clear zone produced increases in value as the algae concentration increases; however, the strength of the antibacterial antibiotic in all treatment samples is classified as moderate with a clear zone diameter of 5-10 mm. All treatment groups did not show any significant differences in the inhibitory power of the pathogenic bacteria

Staphylococcus aureus. The increase in inhibitory power in lotions with the addition of algae is related to the bioactive content, which influences their bioactivity. The oxidative potential of hydroxyl groups can change bacterial cell membranes, so this will inhibit bacterial growth (Bogolitsyn

et al., 2019). The inhibition zone for lotions containing of algae or algae porridge against gram-positive bacteria (

S. aureus) is higher than that for gram-negative bacteria (

E. coli). This is due to physical differences in the ability of gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative bacteria to simplicia. These physical differences include bacterial cells’ morphological structure and their composition within the cells (Sahgal

et al., 2011). An outer membrane with a high lipopolysaccharide content surrounds gram-negative bacteria. This membrane allows bacteria to resist several antibiotics, whereas gram-positive bacteria have cell walls that are relatively polar compared to the cell walls of gram-negative bacteria, making gram-positive bacteria more easily penetrated by antimicrobial compounds. In addition, gram-positive bacteria contain high levels of nucleic acid. Antibacterials from phenolic compounds can denature proteins and nucleic acids, thereby irreparably damaging bacterial cell membranes. Inhibition of bacterial growth occurs due to interference by active compounds in the extract or simplicia (Sameeh

et al., 2016). Increasing the concentration of the extract or simplicia is needed to kill microorganism cells rather than inhibiting their growth (Ibrahim

et al., 2013).

3.2. Phytochemical Screening

Phytochemical analysis was carried out based on the Harbourne (1995) method, which includes tests for alkaloids, triterpenoids, and steroids, flavonoids, saponins, and polyphenols. The dry powder of S. lomentaria, as a result of research, contains polyphenol and tannin compounds. This is indicated by a blue solution when Follin Ciocalteau phenol reagent Hi-LR is added. Meanwhile, lotion with the addition of 30% S. lomentaria contains polyphenolic compounds, tannins, and saponins. The saponin content is indicated by the formation of stable foam when water and HCl reagent are added. The addition of algae to lotion can contain polyphenol and tannin compounds. Compounds that have potential as antioxidants and antibacterials can be predicted from the phenolic, alkaloid, and flavonoid groups, which are polar compounds.

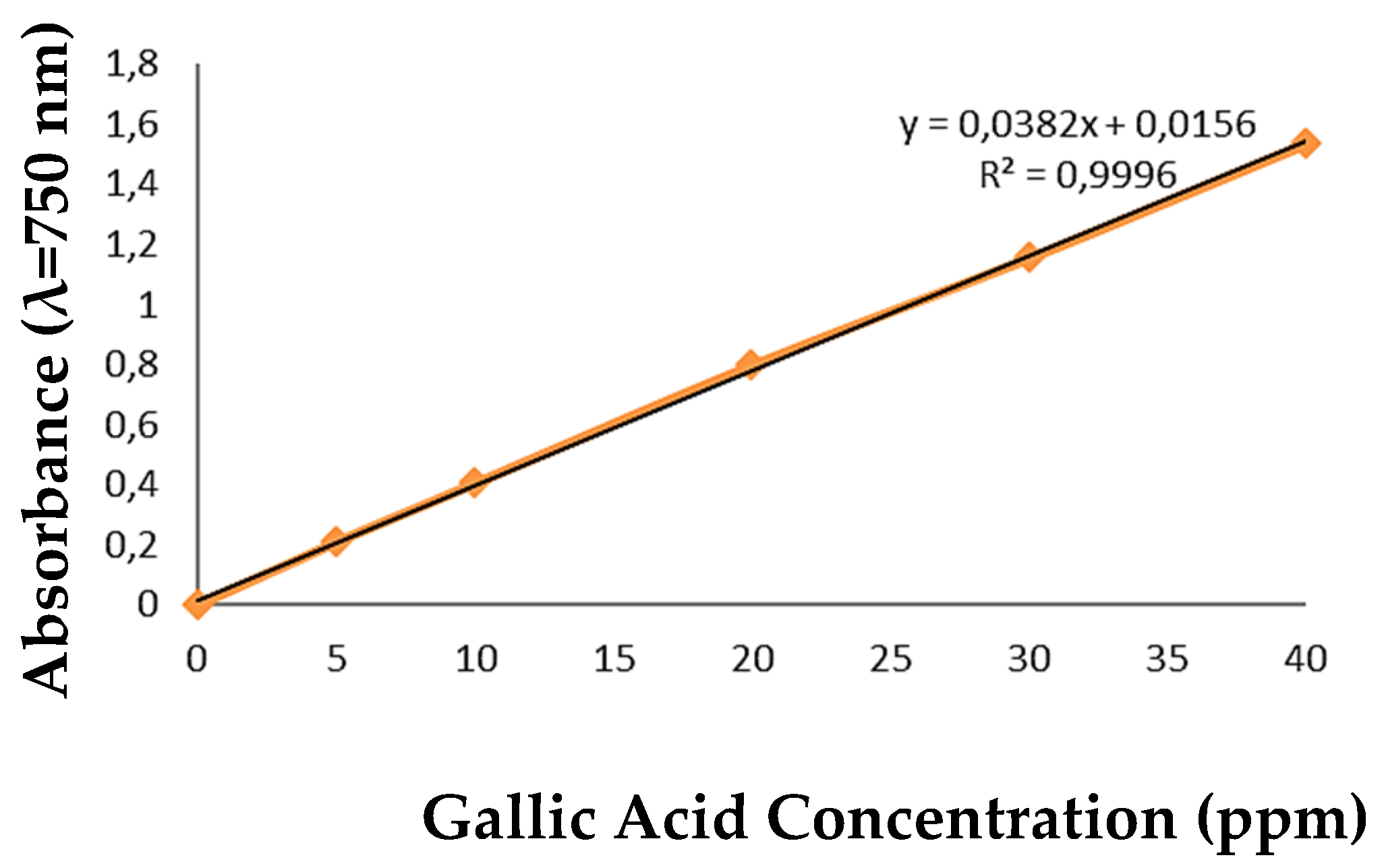

3.3. Total Phenolic Content

S. lomentaria algae powder was analyzed to determine the amount of phenolic contained in the algae. The activity of phenolic compounds comes from the number of hydroxyl groups on the benzene ring (Dhianawaty and Ruslin, 2015). The analysis of total phenolic content was carried out using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and a reference in the form of gallic acid. The gallic acid standard curve was determined by plotting the absorbance results of gallic acid at various concentrations, which had been reduced by the absorbance of the blank solution (distilled water). Gallic acid is made into six concentrations, such as 5 ppm, 10 ppm, 15 ppm, 20 ppm, 25 ppm, 30 ppm, 35 ppm, and 40 ppm. The absorbance values of gallic acid at various concentrations were then plotted on a linear regression curve as the y value and the actual value of the gallic acid concentration as the x value. The equation of the linear curve for gallic acid is obtained from the graph formed:

The R2 value is obtained close to 1, so there has been a perfect linear relationship in the form of a straight line between the increase in gallic acid concentration and the increase in absorbance (A) value. The standard curve of gallic acid at various absorbance concentration variations can be seen in

Figure 1.

The results of measuring the total phenol content of

S. lomentaria powder in gallic acid equivalent (GAE) units can be seen in

Table 3. The average total phenolic content at a concentration of 200 ppm (200 μg/ml or 0.2 mg/ml) is 117.70 mg GAE/g dry basis. The total phenol content of

S. lomentaria powder is relatively higher compared to the total phenol of several other types and species of brown algae, such as

S. muticum, which is 230.8 ± 17.1 mg GAE/100 g dry basis (Farvin and Jacobsen, 2013);

Codium vermilara was 16.72 ± 0.065 mg GAE/g extract (Pinteus

et al., 2017);

S. vulgare was 7.09 g GAE/100 g extract (Plaza

et al., 2010);

S. thunbergii amounted to 11.5 g GAE/100 g extract (Luo

et al., 2010); and

S. hystrix was 11.43 g GAE/100 g dry basis (Lailatussifa, 2017). However, the total phenolic content of

S. lomentaria powder in this study was lower than the total phenolic content of

S. polycystum of 59.30 g GAE/100 g extract (Lailatussifa and Pereira, 2022);

Fucus spiralis was 397.23±0.02 mg GAE/g extract;

Bifurcaria bifurcata was 129.17±0.002 mg GAE/g extract (Pinteus

et al., 2017); and

S. kjelmanianum of 16.3 g GAE/100 g extract. The high or low total phenolic content is influenced by intrinsic factors (sample type and species, sampling location, and sample age) as well as extrinsic factors (temperature, climate, depth, salinity, tidal zone, and tidal cycle) (Lann

et al., 2012).

3.4. DPPH (1,1-diphenyl 2-picrylhydrazyl) Free Radical Scavenging Activity

The IC

50 value is the substrate concentration that can reduce DPPH activity by 50%. This parameter is defined as the amount of antioxidant required to reduce DPPH absorbance by 50% of the initial absorbance (Mishra

et al., 2012). The IC50 values of the dry powder of S. lomentaria and standard vitamin C can be seen in

Table 4.

The IC50 value of S. lomentaria dry powder is 0.455 ± 0.004 mg/ml, or 455 ± 3.40 ppm. This value is higher than the IC50 value of S. polycystum phlorotannin extract of 1.20 ± 0.01 mg/ml, S. polycystum polyphenol extract of 1.27 ± 0.01 mg/ml (Sianipar and Gunardi, 2023), S. filipendula polysaccharide sulfate is 1,000 ppm (Costa et al., 2011), Fucus vesiculosus polysaccharide sulfate is 800 ppm (Suresh et al., 2013), and S. plagiophyllum polysaccharide sulfate is 700 ppm (Suresh et al., 2013). The IC50 value of S. lomentaria dry powder is 0.33 ± 0.03 mg/ml, which is lower than the IC50 value of S. hystrix extract (Maheswari and Babu, 2022a).

The IC

50 value of

S. lomentaria dry powder is significantly different from the vitamin C standard with a confidence level of 95% (

Table 4). The IC50 value of

S. lomentaria dry powder is, however, lower than that of standard vitamin C, with a value of 0.013 ± 0.002 mg/ml, or 13.10 ± 1.30 ppm. The IC

50 value is classified as strong if the value ranges between 50 and 100 ppm (Ramadhan

et al., 2022). Suresh et al. (2013) stated that brown algae with an IC

50 value of 1000 ppm is reactive and has the potential to be used as an anticancer agent in vitro. The high or low IC

50 value of a sample is influenced by several factors, including the solvent used, the amount of dissolved bioactive content, the sample harvest season, the location of the sampling location, and the type of sample species (Maheswari and Babu, 2022a).

3.5. pH

The pH test is carried out to determine the pH of the lotion preparation so that it can be used as a topical preparation without causing skin irritation.

Table 5 is the physicochemical characteristics of the lotion, including the pH test results. The higher the concentration of algae added to the lotion preparation, the lower the pH value of the lotion preparation. This is consistent with research by Ramdani et al. (2021), which stated that the addition of red algae (

Eucheuma cottonii) to lotion preparations was able to reduce the pH value of the lotion to a value of 6.67. To prevent skin irritation, an ideal lotion preparation has a pH value ranging from 4.5 to 8.0.

3.6. Adhesive Strength

Adhesive Strength is included in the physicochemical characteristics of lotion which can be seen in

Table 5. The results showed that the adhesive strength values are significantly different in each treatment group (p<0.05) (

Table 5). The lowest adhesive force was found in the normal control/lotion base treatment group without the addition of algae, with a value of 15.01 ± 4.54. The adhesion value increased as the concentration of algae added to the lotion preparation increased. The minimum standard value for good adhesion to lotion is more than four seconds (Salsabila

et al., 2021). The higher the adhesive power, the better the lotion’s resistance to the skin, and hence the lotion’s ability as a source of protection (Oktaviasari and Zulkarnain, 2017). The higher the adhesive force, the longer it takes for the two glass objects to separate, so the better the adhesive power of the lotion preparation, the longer the preparation will stick to the skin and the longer the active substance in the lotion will be in contact with the skin (Wong

et al., 2023). When producing lotion preparations, the higher the mixing temperature and the longer the stirring time, the higher the adhesive power will be (Hiola

et al., 2018).

3.7. Spread Power

The spreadability test measures the area where the lotion is spread to determine the spreadability of the lotion or emulsion when applied to the skin (Dina

et al., 2017). The spreadability test results can be seen in

Table 5. The higher the concentration of algae added to the lotion preparation, the lower the value of the lotion’s spreadability, because algae have the ability to act as a thickener in the lotion (Lopez-Hortas

et al., 2021). This is in accordance with research by Ramdani et al. (2021), that the addition of 2% (w/w)

E. cottonii algae to the lotion preparation can reduce the spreadability value of the lotion to 5.16 ± 0.03 cm. However, all treatment groups complied with the standard spreadability of semisolid materials of 5-7 cm (Apriliani

et al., 2021). The spreadability value of the lotion preparation is influenced by several factors, including mixing temperature, mixing time (Hiola

et al., 2018), type of active ingredient formulation, viscosity, and adhesive power (Nurjanah

et al., 2020).

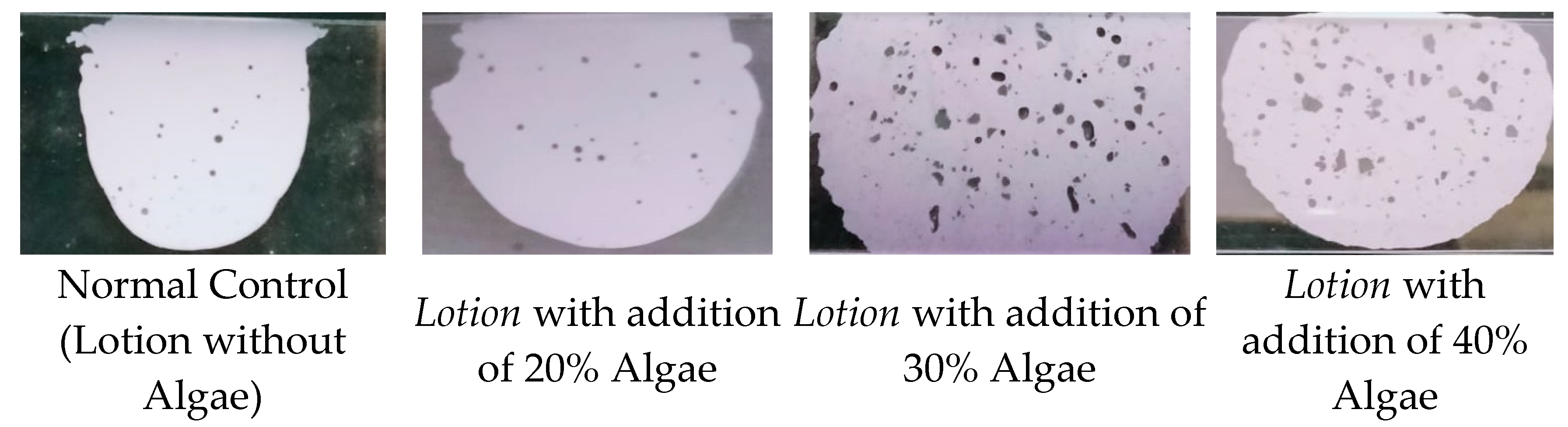

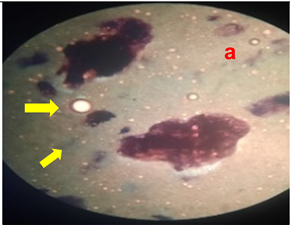

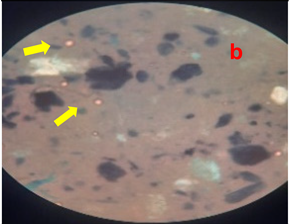

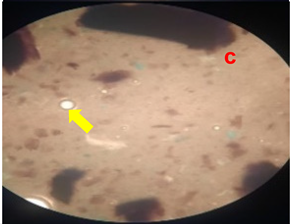

3.8. Homogeneity Test

The results of the homogeneity test on the lotion can be seen in

Table 5 and

Figure 2.

Table 5 shows the results of the homogeneity test for each treatment group. All treatment groups were classified as homogeneous; no solid lumps were formed that were visible when the lotion was contacted with a glass object. The emulsifier, namely TEA and stearic acid, which makes the emulsion between the oil phase and the water phase mix properly, are responsible for the lotion’s good homogeneity. The presence of air bubbles in the lotion is caused by the use of glycerin during the process of making the water phase of the lotion (Apriliani

et al., 2021). The homogeneity of a preparation is influenced by the presence of an emulsifier (Moravkova and Filip, 2013). Apart from that, the mixing temperature and stirring time also influence the homogeneity of a preparation. Stirring time can expand the contact area by increasing the stirring speed, thereby increasing the homogeneity of a mixture (Hiola

et al., 2018).

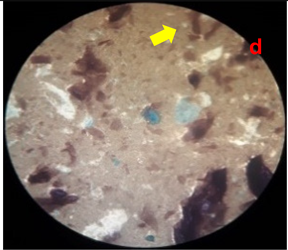

3.9. Emulsion Type

The emulsion type of all lotion treatment groups can be seen in

Table 6.

Table 6 shows that all treatment groups are included in the oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion type. O/W lotion contains more than 31% water (Guzmán

et al., 2022). The results showed that the water phase, as an external phase, was colored by methylene blue, but the oil phase, as an internal phase, was not. The solubility of methylene blue is that it dissolves in water, allowing it to create a color that spreads in the water phase (Pujiastuti & Kristen, 2019). Increasing the concentration of algae added to the lotion preparation does not affect the type of lotion emulsion but affects the texture of the oil in water. The higher the concentration of algae added to the lotion preparation, the more evenly the oil is dispersed on the surface of the lotion, resulting in fewer oil bubbles in the emulsion. This is related to algae’s ability to act as a thickener and emulsifier in lotion preparations (Fernando

et al., 2019).

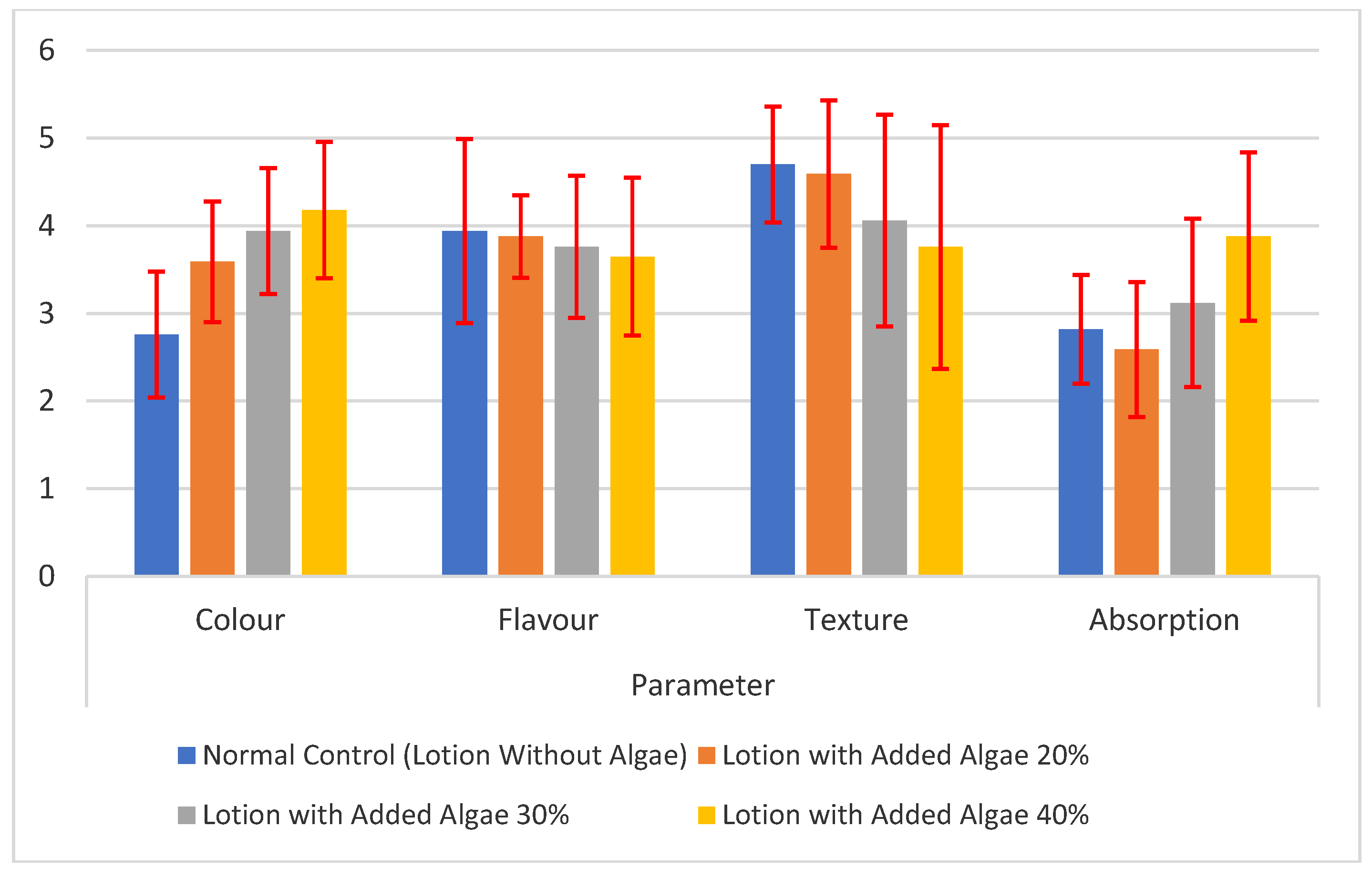

3.10. Hedonic Test

Hedonic tests were carried out on color, aroma, texture, and absorption parameters. The hedonic scale ranges from 1 to 5. Scale value 1 = really don’t like it; 2 = don’t like; 3 = neutral/normal; 4 = like; and 5 = really like it (Joy and Rani, 2013). The results showed that there is a significant difference in the hedonic value of lotion color preference for each treatment group (

Figure 3). The color of the lotion with the addition of 40% algae was the most preferred by the panelists, amounting to 4.18 ± 0.78 with a liking level. The clearer the color of the lotion, the more the panelists prefer it. Lotion with 40% algae added showed matcha green color. The sample that had a least like by the panelists was the normal control treatment (lotion without the addition of seaweed), with a value of 2.76 ± 0.72, indicating dislike towards neutral. The higher the concentration of algae added to the lotion preparation, the more intense the color of the lotion, and the more liked by the panelists. This is in accordance with research by Pratama et al. (2020) who stated that increasing the concentration of the addition of

Kappaphycus alvarezii algae to jicama (2:1) in lotion preparations was preferred by panelists with a neutral preference level of 3.1 ± 0.58 compared to samples without the addition of algae and samples with the addition of a higher concentration of algae. The color formed in the preparation is influenced by the color of the constituent ingredients (Paakki

et al., 2018).

The level of liking for the aroma of the lotion ranged from neutral/usual to liking, with a value range of 3.65 ± 0.90 to 3.94 ± 1.05. The highest aroma hedonic value was found in the lotion base sample treatment without the addition of algae. The higher the concentration of algae added to the lotion preparation, the more it reduces the fragrant smell that comes from the olive oil mixed with the fresh aroma of the algae. In contrast to the research of Sirait et al. (2022), which stated that the addition of 1% Caulerpa racemose algae extract to hand cream preparations without adding other active ingredients was preferred by panelists with a very like level (hedonic value 5.00 ± 1.673). However, the test results are in line with research by Pratama et al. (2020) who stated that increasing the concentration of adding Kappaphycus alvarezii algae to lotion preparations did not affect the level of panelists’ liking for the lotion aroma, with hedonic values ranging from 3.13-3.55 with neutral levels to liking.

All treatment groups had hedonic texture values ranging from neutral to like to like to very like (3.76-4.70), with a quality value from slightly soft to soft. The texture most preferred by the panelists was the base lotion treatment group without the addition of algae, with the hedonic quality of a soft texture. Adding algae concentration to the lotion creates a slightly rough and thick texture. This is in line with research by Pratama et al. (2020), which states that increasing the concentration of algae in lotion preparations reduces the panelists’ level of preference because algae can make the lotion chewier, which the panelists dislike.

The highest hedonic value of lotion absorption was found in the lotion treatment with the addition of 40% algae, amounting to 3.88 ± 0.96, with the quality characteristic of high absorption. The hedonic value of the absorption capacity of lotion with the addition of 40% algae was significantly different from all other treatment groups. The addition of algae to the preparation functions as a moisturizer, so it can increase skin hydration and absorption capacity (Nejad et al., 2020).

4. Conclusion

This study set out to analyze microbial inhibitory ability, physical and chemical characteristics of hand sanitizer lotion made from Scytosiphon lomentaria algae. The addition of 40% S. lomentaria porridge to lotion preparations can be used as a hand sanitizer with moderate bacterial level inhibition. It contains secondary bioactive compounds in the form of polyphenols and saponins as antioxidants, with an IC50 value of S. lomentaria powder of 455±3.4 ppm and a total phenolic content of 117.70 ± 1.40 mg GAE/g dry weight. The S. lomentaria hand sanitizer lotion has an O/W emulsion type and is well accepted by the panelists based on the hedonic test. This research can be an alternative reference in making non-alcoholic hand sanitizer lotion that is safe for the skin.

Funding

This research was partially supported by Polytechnic of Marine and Fisheries Sidoarjo with DIPA 2022.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank the entire team for their support during the research, until the completion of this paper.

References

- Abuga, K. & Nyamwega, N. (2021). Alcohol-based hand sanitizers in covid-19 prevention: a multidimensional perspective. Pharmacy, 9(64): 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Apriliani, E. P., Putri, R. M. S. and Apriandi, A. (2021) ‘Formulation of Seaweed (Sargassum polycystum) and Mangrove (Rhizophora apiculata) Leaf as Antimosquito Lotion’, E3S Web of Conferences, 324, pp. 0–3. [CrossRef]

- Bogolitsyn, K. et al. (2019) ‘Biological activity of a polyphenolic complex of Arctic brown algae’, Journal of Applied Phycology, 31(5), pp. 3341–3348. [CrossRef]

- Costa, L. S. et al. (2011) ‘Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of heterofucans from the seaweed Sargassum filipendula’, Marine Drugs, 9(6), pp. 952–966. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S., Moon, W.S., Choi, J.N., Do, K.H., Moon, S.H., Cho, K.K., Han, C.J., & Choi, I.S. (2013). Effects of seaweed Laminaria japonica extracts on skin moisturizing activity in vivo. J Cosmet Sci. 64(3):193-205. PMID: 23752034.

- Egner, P., Pavlackova, J., Sedlarikova, J., Pleva, P., Mokrejs, P., & Janalikova, M. (2023). Non-alcohol hand sanitiser gels with mandelic acid and essential oils. International Journal of Molecular Science, 24(3885): 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Fahreni, Mardiana, V., Indriaty, & Ramaidani. (2021). Examination of gel hand sanitizer from mangrove leaves and Patchouli oil against Staphylococcus aureus. International Journal of Engineering, Science & Information Technology, 1(4): 7-12. [CrossRef]

- Gunathilaka, M. D. T. L. (2023) ‘Utilization of Marine Seaweeds as a Promising Defense Against COVID-19: a Mini-review’, Marine Biotechnology, 25(3), pp. 415–427. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, E., Ortega, F. and Rubio, R. G. (2022) ‘Pickering Emulsions: A Novel Tool for Cosmetic Formulators’, Cosmetics, 9(4), p. 68. [CrossRef]

- Hans, M. et al. (2023) ‘Production of first- and second-generation ethanol for use in alcohol-based hand sanitizers and disinfectants in India’, Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 13(9), pp. 7423–7440. [CrossRef]

- Harborne, J. B. (1995). Phytochemical Methods: A Guide to Modern Ways of Analyzing Plants. Penerbit ITB. Bandung.

- Hiola, R. et al. (2018) ‘Formulation and Evaluation of Langsat (Lansium domesticum Corr.) Peel Ethanol extracts Lotion as Anti-Mosquito Repellent’, Journal of Reports in Pharmaceutical Sciences, 7(3), pp. 250–259. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, D. et al. (2013) ‘Efficacy of pyroligneous acid from rhizophora apiculata on pathogenic Candida albicans’, Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science, 3(7), pp. 7–13. [CrossRef]

- Joy, K. H. M. and Rani, R. N. A. (2013) ‘Formulation, sensory evaluation and nutrient analysis of products with Aloe Vera.’, World Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences (WJPPS), 2(6), pp. 5321–5328.

- Kang, C. et al. (2010) ‘Brown alga Ecklonia cava attenuates type 1 diabetes by activating AMPK and Akt signaling pathways’, Food and Chemical Toxicology, 48(2), pp. 509–516. [CrossRef]

- Kantachumpoo, A. and Chirapart, A. (2010) ‘Components and antimicrobial activity of polysaccharides extracted from thai brown seaweeds’, Kasetsart Journal—Natural Science, 44(2), pp. 220–233.

- Khalaf, N. A. et al. (2008) ‘Antioxidant activity of some common medicinal plants’, International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research, 32(2), pp. 51–55.

- Kao, R., Alsaif, N., Thain, A., Kao, V., Misener, B., & Chu, M. (2023). Alcohol-based hand sanitizer’s effect on hand barrier function induced Staphylococcus lugdunensis aortic and mitral valve endocarditis: a case report. Case Report: Surgery: Cardiac Surgery, 8(26): 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.A., Hout, D.V., Dessirier, J.M. & Lee, H.S. (2017). Degree of satisfaction-difference (DOSD) method for measuring consumer acceptance: A signal detection measurement with higher reliability than hedonic scalling. Food Quality and Preference, 63: 28-37. [CrossRef]

- Lailatussifa, R., Husni, A., & Isnansetyo, A. (2017). Antioxidant activity and proximate analysis of dry powder from brown seaweed Sargassum hystrix. Jurnal Perikanan Universitas Gadjah Mada, 19(1): 29-37. ISSN: 0853-6384 eISSN: 2502-5066.

- Lailatussifa, R. & Pereira, M.M. (2022). Phenolic content analysis of algae extract Sargassum polycystum from south beach, Gunung Kidul, Yogyakarta. Chanos chanos, 20(1): 215-225.

- Lann, K.L., Ferret, C., VanMee, E., Spagnol, C., Lhuillery, M., Payri, C., et al. (2012). Total phenolic, size-fractionated phenolics and fucoxanthin content of tropical Sargassaceae (fucales, phaeophyceae) from the South Pacific Ocean: spatial and specific variability. Phycological Research, 60: 37-50. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. et al. (2020) ‘Hand Sanitizers: a Review on Formulation Aspects, Adverse Effects, and Regulations’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, p. 3326.

- Lopez-Hortas, L. et al. (2021) ‘Applying seaweed compounds in cosmetics, cosmeceuticals and nutricosmetics’, Marine Drugs, 19(10), pp. 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.Y., Wang, B., Yu, C.G., Qu, Y.I. & Su, G.I. (2010). Evaluation of antioxidant activities of five selected brown seaweeds from China. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research, 4: 2557-2565. [CrossRef]

- Maheswari, V. and Babu, P. A. S. (2022). ‘Phlorotannin and its Derivatives, a Potential Antiviral Molecule from Brown Seaweeds, an Overview’, Russian Journal of Marine Biology, 48(5), pp. 309–324. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K., Ojha, H., & Chaudury, N.K. (2012). Estimation of antiradical properties of antioxidants using DPPH assay: A critical review and results. Food Chemistry, 130: 1036-1043. [CrossRef]

- Moravkova, T. & Filip, P. (2013). The influence of emulsifier on rheological and sensory properties of cosmetic lotions. Hindawi Publishing Corporation, 2013: 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Nejad, H.B., Blasco, L., Moran, B., Cebrian, J., Jim, Woodger, Gonzalez, E., Pritts, C., & Milligan, J. (2020). Bio-based algae oil: an oxidation and structural analysis. International Journal of Cosmetic Science, 42(3): 237-247. [CrossRef]

- Nurjannah, N., Jacoeb, A.M., Bestari, E., & Seulalae, A.V. (2020). Characteristics of seaweed mosses Gracilaria verrucosa and Turbinaria connoides as raw materials body lotion. Jurnal Akuatek, 1(2), 73–83. [CrossRef]

- Oktaviasari, L. &. Zulkarnain, A.K. (2017). Formulation and physical stability test of lotion O/W potato starch (Solanum tuberosum L.) and the activities as sunscreen. Majalah Farmaseutik, 13(1): 9-27. [CrossRef]

- Olejnik, A. & Goscianska, J. (2023). Incorporation of UV filters into oil -in-water emulsionsRelease and permeability characteristics. Applied Sciences, 13(7674): 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Osório, C. et al. (2020) ‘Pigments content (Chlorophylls, fucoxanthin and phycobiliproteins) of different commercial dried algae’, Separations, 7(2), pp. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Paakki, M., Aaltojarvi, I., Sandell, M., & Hopia, A. (2018). The importance of the visual aesthetics of colours in food at a workday lunch. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 16: 100131. [CrossRef]

- Pinteus, S., Silva, J., Alves, C., Horta, A., Fino, N., Rodrigues, A.I., Mendes, S., & Pedrosa, R. (2017). Cytoprotective effect of seaweeds with high antioxidant activity from the Peniche coast (Portugal). Food Chemistry, 218: 591-599. [CrossRef]

- Poulose, N., Sajayan, A., Ravindran, A., Sreechithra, T.V., Vardhan, V., Selvin, J., & Kiran, G.S. (2020). Photoprotective effect of nanomelanin-seaweed concentrate in formulated cosmetic cream: With improved antioxidant and wound healing properties. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. 205: 111816. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B., Patra, S., Dash, S.R., Nayak, R.. & Bahera, C. (2021). Evaluation of the antibacterial activity of methanolic extract of Chlorella vulgaris Beyerinck (Beijerinck) with special reference to antioxidant modulation. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 7(1): 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Praselya, Z. & Fitriani, N. (2022). Formulation of hand sanitizer gel of methanol extract seaweed (Eucheuma spinosum) from Bontang City, East Kalimantan. Mulawarman Pharmaceutical Conference, 15(2022): 205-212. [CrossRef]

- Pratama, G., Novshally, A., Apriandi, A., Suhandana, M., &. Ilhamdy, A.F. (2020). Evaluation of body lotion from seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii) and Jicama (Pachyrhizus erosus). Jurnal Perikanan dan Kelautan, 10(1): 55-65. [CrossRef]

- Priyan Shanura Fernando, I. et al. (2019) ‘Algal polysaccharides: potential bioactive substances for cosmeceutical applications’, Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 39(1), pp. 99–113. [CrossRef]

- Pujiastuti, A. & Kristiani, M.. (2019). Formulation and mechanical stability test for hand and body lotion from tomato juice (Lecopersicum esculentum Mill.) as antioxidants. Jurnal Farmasi Indonesia, 16(1): 42-55. [CrossRef]

- Radiena, M.S.Y., Moniharapon, T., & Setha, B. (2019). Antibacterial activity of ethyl acetate extract of green algae SILPAU (Dictyosphaeria versluysii) on bacteria Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Majalah BIAM, e-ISSN: 2548-4842 p. 41-49. [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, R. et al. (2022) ‘The potency of selected ethnomedicinal plants from East Kalimantan, Indonesia as antidiabetic agents and free-radical scavengers’, Biodiversitas, 23(4), pp. 2225–2230. [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, Y., Ananto, A.D., & Hajrin, W. (2021). Variation Of Extraction Methods And Determination Of SPF Value of Red Seaweed (Eucheuma cottonii) Lotion. Acta Pharmaciae Indonesia, 9(1): 31-43. e-ISSN 2621-4520.

- Sabeena Farvin, K. H. and Jacobsen, C. (2013) ‘Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of selected species of seaweeds from Danish coast’, Food Chemistry, 138(2–3), pp. 1670–1681. [CrossRef]

- Sahgal G., Ramanathan, S., Sasidharan, S., Mordi, M.N., Ismail, S., & Mansor, S.M. (2011). In vitro and in vivo anticandidal activity of Swietenia mahogany methanolic seed extract. Tropical Biomedicine, 28 (1): 132–137. PMID: 20237441.

- Salsabila, S., Rahmiyani, I., & Zustika, D.S. (2021). Sun Protection Factor (SPF) value in water guava leaf ethanol extract (Syzygium aqueum) lotion preparation. Majalah Farmasetika, 6: 123-132. [CrossRef]

- Sameeh, M.Y., Mohamed, A.A., & Elazzazy, A.M. (2016). Plyphenolic contents and antimicrobial activity of different extracts of Padina boryana Thivy and Enteromorpha sp. marine algae. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science, 6(9): 87-92. [CrossRef]

- Sayuti, N.A. (2015). Formulation and physical stability of Cassia alata L. leaf extract gel. Jurnal Kefarmasian Indonesia, 5(2): 74-82.

- Scania, A.E. & Chasani, A.R. (2021). The anti-bacterial effect of phenolic compounds from three species of marine macroalgae. BIODIVERSITAS, 22(6): 3412-3417. [CrossRef]

- Sianipar, E. A. and Gunardi, S. I. (2023) ‘Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of Sargassum polycystum ethyl acetate extract from Indonesia’, Journal of HerbMed Pharmacology, 12(3), pp. 407–412. [CrossRef]

- Sidauruk, S.W., Sari, N.I., Diharmi, A., Arif, I., & Sukmiwati, M. (2021). Characteristics of Sargassum plagyophillum extract as an active compound on Non-Alcoholic hand sanitizer. IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Sciences, 934(2021): 012096. [CrossRef]

- Sirait, S.M., Rosita, T., & Rahmatia, L. (2022). Formulation and evaluation of sea grape (Caulerpa racemose) extract as hand cream and its antioxidant activity test. Jurnal Kimia Riset, 7(1): 47-56. [CrossRef]

- Suresh, V., Senthilkumar, N., Thangam, R., Rajkumar, M., Anbazhagan, C., Rengasamy, R., Gunasekaran, P., Kannan, S., & Palani, P. (2013). Separation, purification, and preliminary characterization of sulfated polysaccharides from Sargassum plagiophyllum and its in vitro anticancer and antioxidant activity. Process Biochemistry, 48: 364-373. [CrossRef]

- Suryavanshi, M., Sachdeva, N., Jaipuria, J., Bhushan, V., & Sharma, K. (2021). Time to relook at formulations recommended for hand sanitizers formulation-An in vitro study. Indian Journal of Applied Microbiology, 23(2): 11-29. [CrossRef]

- Tamama, K. (2021) ‘Potential benefits of dietary seaweeds as protection against COVID-19′, Nutrition Reviews, 79(7), pp. 814–823. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H. et al. (2023) ‘Contact dermatitis caused by prevention measures during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review’, Frontiers in Public Health, 11(July), pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Umarudin, Surahmaida, Syukrianto, Wulansari, S.A., & Nurhaliza, S. (2020). Application of snail shell chitosan hand sanitizer as antibacterial and preventive efforts for Covid-19. SIMBIOSA, 9(2): 107-117. [CrossRef]

- Wong, S. H. D. et al. (2023) ‘Smart Skin-Adhesive Patches: From Design to Biomedical Applications’, Advanced Functional Materials, 33(14). [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. J., Zhang, Y., Lin, H., Kang, C., & Fu, X.T. (2017). Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of a brown alga Scytosiphon lomentaria. Chiang Mai Journal of Sciences, 44(2): 595-604. [CrossRef]

- Yanuarti, R., Nurjanah, Anwar, E., & Pratama, G. (2021). Physical evaluation of sunscreen cream from Kappaphycus alvarezii and Turbinaria conoides. Jurnal Fishtech, 10(1): 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, Z., Mohamed, A.M., Jamil, N.S.M., Rofiee, S., Hussain, M.K., Sulaiman, M.R., The, L.K., & Salleh, M.Z. (2011). In vitro antiproliferative and antioxidant activities of the extracts of Muntingia calabura leaves. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine, 39(1): 183-200. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).