1. Introduction

The greatest challenges related to the lithium-ion cells upgrades are improvements in their safety by eliminating organic solvents present in classic, non-aqueous electrolytes.

Because during a car accident the battery can be damaged which, in combination with a rise in temperature and/or electrodes short circuit can lead to fire or even explosion of solvent vapors. For this reason, currently produced lithium-ion cells are packed e.g. in steel cans, which protect the cell against mechanical damage and can also withstand high internal pressure [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, the addition of heavy packaging significantly lowers the gravimetric and volumetric energy density of the cell. Rather that introducing a heavy external component, a solution focused on optimizing the composition of battery itself would be preferable. One of the solution is to replace the flammable, volatile carbonates with other solvents, but although many different alternative liquid electrolytes have been proposed so far, they still require a lot of research [

5,

6]. As a result, carbonates are still in use in most of the cells produced nowadays. In order to improve the specific properties of the electrolyte or reduce many of their problems, flame retardants and other additives are used [

7,

8,

9]. Unfortunately, this is only a partial solution and does not make it completely safe to use or does not have the appropriate electrochemical properties to be used in production. Another method is to replace the liquid systems with solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs) or immobilize the solvent molecules in gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs) [

10,

11]. Although SPEs fully comply with safety requirements, their use is still limited due to their low ionic conductivity, poor compatibility with electrodes or other limitations [

12].

A different approach to the safety of electrolytes would be the development of systems capable to responding to an impact. Such systems are currently being investigated and their operation is based on the shear thickening effect. Shear thickening fluids (STFs) (also called dilatant fluids) are colloidal suspensions that exhibit a significant increase in viscosity with increasing shear rate [

13]. This process is reversible, so the material regains its original properties after the force is removed. Due to such properties and their ability to absorb energy STFs are good candidates for protective applications, for example in liquid armor and protective clothing [

14,

15,

16], shock absorbers and dampers [

17,

18,

19,

20], and protective sports equipment [

21,

22]. STFs usually consist of colloidal particles of size up to 100 microns in diameter (e.g. silica, calcium carbonate, and so on) suspended in a carrier liquid (e.g. water, ethylene glycol, polyethylene glycol). The introduction of the lithium salt into STFs forms a new type of electrolytes called shear thickening electrolytes (STEs). These electrolytes could exhibit high conductivity values similar to those of liquid electrolytes while simultaneously possessing better mechanical properties, particularly under impact, akin to solid electrolytes [

23].

The first report about the use of shear thickening electrolyte for lithium-ion battery application belongs to Ding et al., who described systems containing fumed silica and 1 M LiFP

6 in EC/DMC. The electrolyte with 9.1 wt.% silica showed shear thickening behavior, with an increased ionic conductivity compared with the commercial electrolyte [

24]. Veith et al. also studied silica nanoparticles introduced into conventional liquid electrolytes, introducing the concept of SAFIRE – Safe Impact Resistant Electrolytes, which can be produced from battery-compatible and low-cost materials. Studies of various types of synthesized and commercially purchased silicas show that the internal short circuit may be prevented by application of STFs [

25]. However, so far all these shear thickening electrolytes have contained low molecular weight, flammable carbonates that have low boiling points and high vapor pressures. This is not the most advantageous option due to the fact that during the shear thickening effect, kinetic energy is converted into other types of energy, such as thermal energy [

26]. This may cause the cell to burst due to heating.

In this article, we propose shear thickened electrolytes that do not contain volatile, flammable organic solvents. Instead, they use oligoethers as the continuous phase, which, due to their branched structure, have lower viscosity compared to their linear counterparts.

2. Experimental

2.1. Synthesis of Star-Shaped Oxyethylene and Oxypropylene Glycols

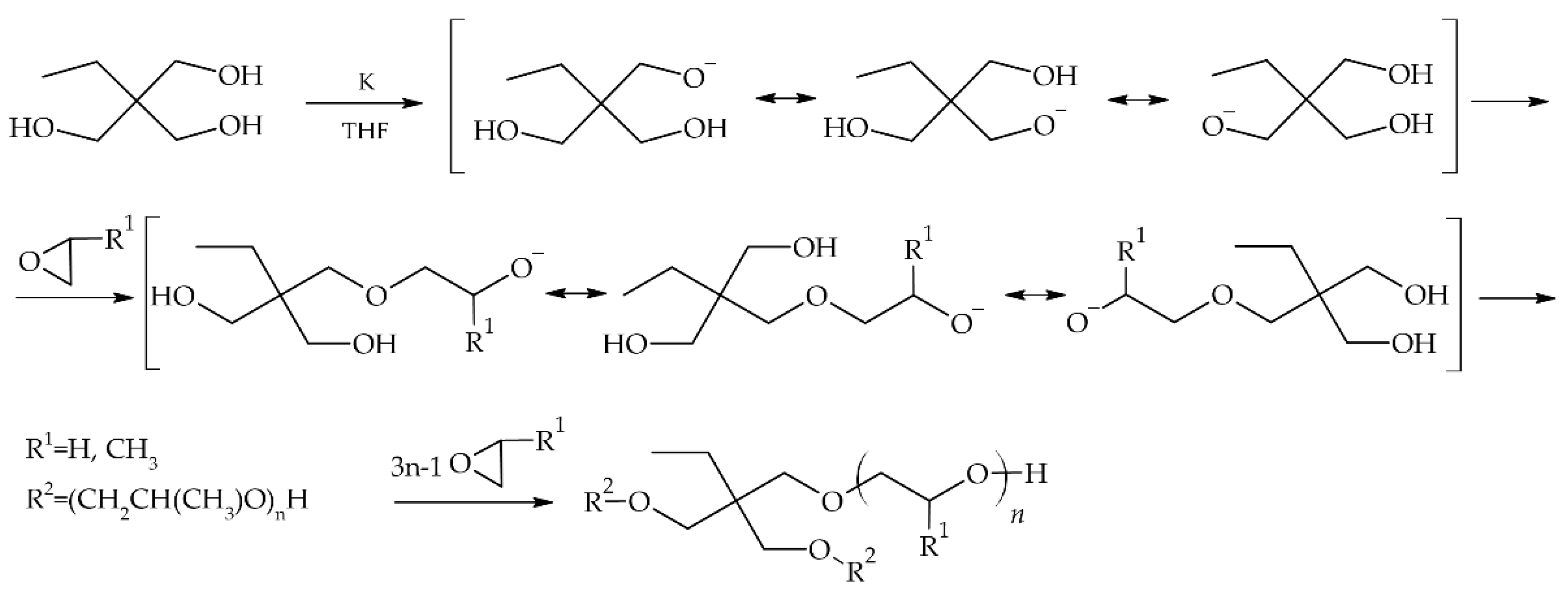

Star-shaped glycols have been obtained using an anionic polymerization mechanism (

Figure 1). TMP was used as the core. The reaction was carried out in a pressurized reactor under an inert gas atmosphere. The synthesis proceeded in two stages. The first stage was initiation. Metallic potassium, which was in deficiency (10 mol% in relation to the TMP hydroxyl groups), was used as the initiator. Active alkoxide centers remained in equilibrium, which made it possible to obtain oligomeric stars with arms of equal length. In the case of ethylene glycols, this step was carried out in THF at room temperature for several hours. The mixture was then cooled using dry ice, and ethylene oxide was introduced. This reaction stage lasted for 10 hours at a temperature of 50-60 °C. Star-shaped oligo(oxypropylene), on the other hand, was obtained without the presence of a solvent. The first stage of the reaction was carried out for 4 h at 100 °C. The reactor was then cooled to room temperature, and the appropriate amount of propylene oxide was introduced. Polymerization was carried out for 12 h at 140 °C. After the reaction was completed, the reaction mixture was purified by passing it through a column filled with a cation exchanger to remove potassium ions. Methanol was used as the eluent. After purification, the solvent was removed by vacuum distillation at 60 °C.

The amounts of reagents were selected to obtain an oligomer of propylene oxide with a mass of approximately 2000 g mol-1 and ethylene oxide with masses of approximately 2000 g mol-1 and 1000 g mol-1, assuming complete conversion of the monomer.

2.2. Preparation of Electrolytes

Star-shaped oligo(oxypropylene) with a mass of approximately 2000 g mol-1 was used to obtain shear thickened electrolytes. Due to the fact that oligo(oxyethylene) with a similar mass is a solid at room temperature, it was decided to use a compound with a lower mass (approx. 1000 g mol-1). Nanosilica was added in portions to the obtained glycols while mixing the contents of the vessel using a mechanical mixer. When mixing was difficult due to the high viscosity of the system, the system was heated with max temperature 100 °C. In this way, shear thickening fluids were obtained. Lithium salt was added to the obtained STFs, and everything was mixed also using a mechanical mixer. The obtained composites were also placed in an ultrasonic bath. As a reference electrolyte, we obtained electrolytes without the addition of silica, the appropriate glycol was mixed with salt. These activities were performed in an argon atmosphere.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Star-Shaped Oxyethylene and Oxypropylene Glycols

The product, with a mass of approximately 2000 g mol

-1, obtained according to the synthesis described in

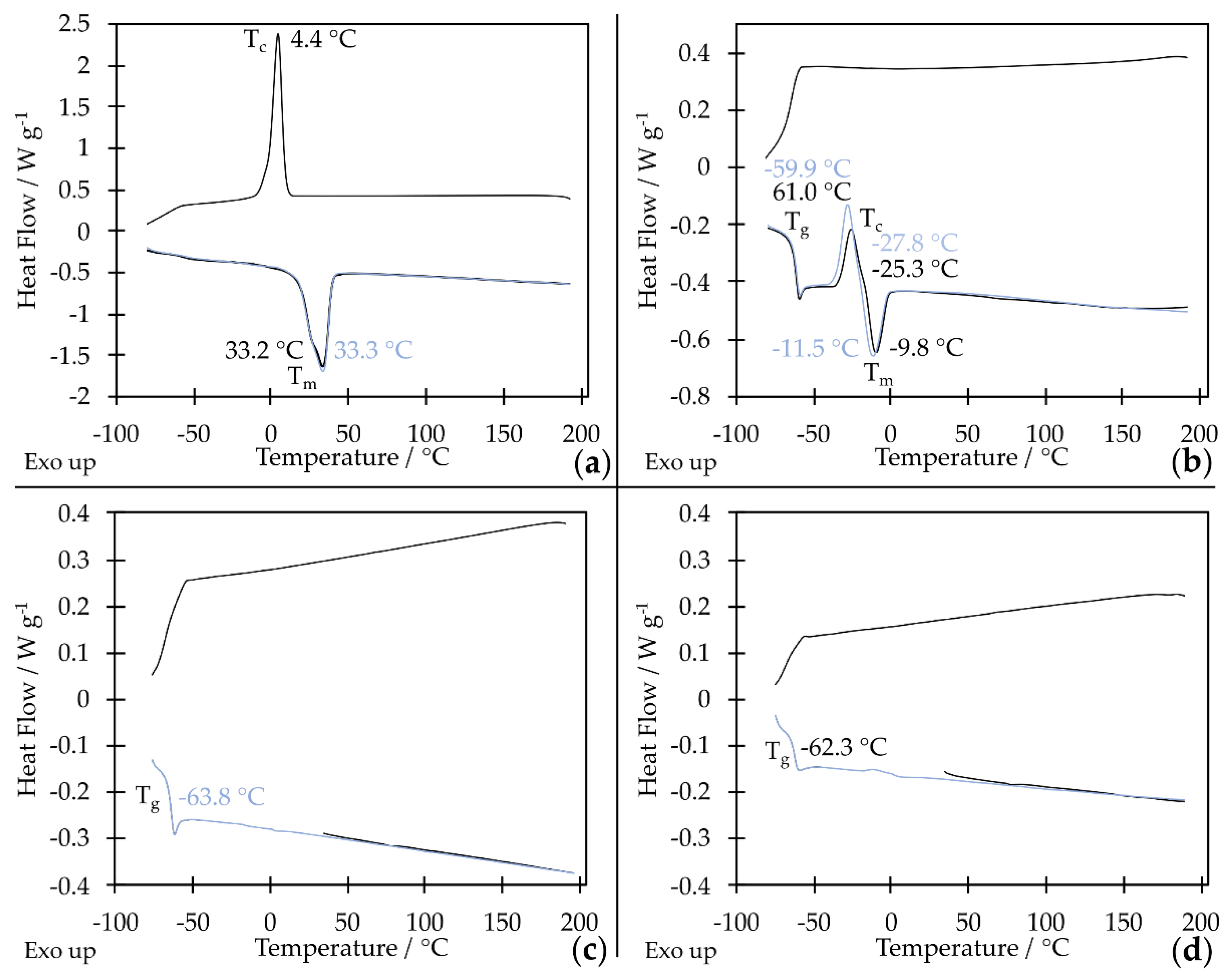

Figure 1, where the monomer was ethylene oxide, at room temperature was a solid that started to melt at 33.3 °C (

Figure 2a). Therefore, it was decided to obtain star-shaped oligo(oxyethylene) with a lower molar mass. Star-shaped oligo(oxyethylene) with a mass of approximately 1000 g mol

-1 at room temperature has the properties of a viscous liquid. However, it is not fully amorphous. It has a melting point of T

m = -11.5 °C (values determined from the second heating cycle, Figure 2b), which means it cannot be used in a very wide temperature range. However, the product, whose repeating units are propylene oxide, has the properties of a viscous liquid at room temperature. It is fully amorphous and characterized by a glass transition temperature of -63.8 °C (Figure 2c). Thanks to this, it can be used in a wide temperature range. This is important in the case of using star-shaped oligo(propylene glycol) as a solvent in shear thickened electrolytes, which are to be used in li-ion cells.

1H,

13C NMR and MALDI-TOF spectroscopy methods confirmed the obtainment of the expected product as a result of anionic polymerization on a core derived from potassium alkoxide obtained by reaction with TMP. The spectrum shows signals from protons in the CH

3- (0.74-0.85 ppm), -CH

2- (1.28-1.40 ppm), and -CH

2O- (3.21-3.30 ppm) groups from the initiator constituting the core of the oligomer, as well as signals from the groups -OCH

2 (3.55-3.63 ppm)- or -OCH- (3.47 ppm) coming from the oligomer arms. Signals from protons in the last repeating unit are also visible at (3.60-3.95 ppm). In the case of three-armed propylene glycol, a signal from the -CH

3 group in the chain (1.16 ppm) is also visible (

Figure S1). Moreover, from the

13C NMR spectra, it can be concluded that each hydroxyl group of the TMP core is substituted based on the 43 ppm unsplit signal (Figure S2). MALDI-Tof analysis (

Figure S3) allowed to confirm that the tested product contains mainly the 3-arm oligo(oxypropylene).

3.2. Shear Thickening Fluids

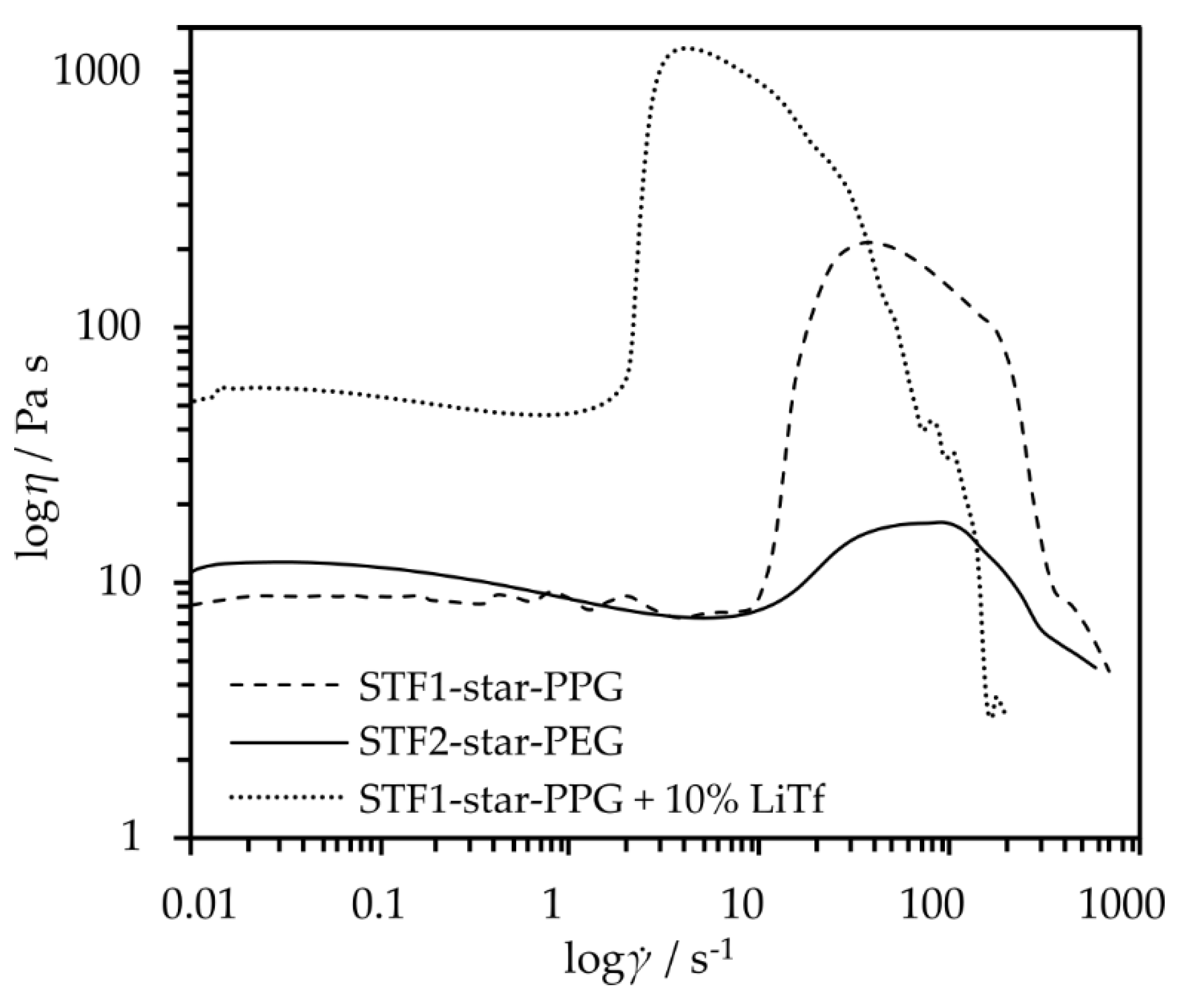

In order to determine the influence of the continuous phase on the rheological properties of fluids, the obtained star-shaped glycol-based composites were subjected to rheo-logical tests. The test results are presented in

Figure 3. Both types of tested composites, the one obtained with star-shaped oligo(oxypropylene) (STF1-star-PPG) and the one with oligo(oxyethylene) (STF2-star-PEG), are shear-thickening fluids. The viscosity jump is observed at a similar value of the critical shear rate. However, the value of the viscosity jump is much higher for a fluid made of STF1-star-PPG (205 Pa s) than for STF2-star-PEG (10 Pa s).

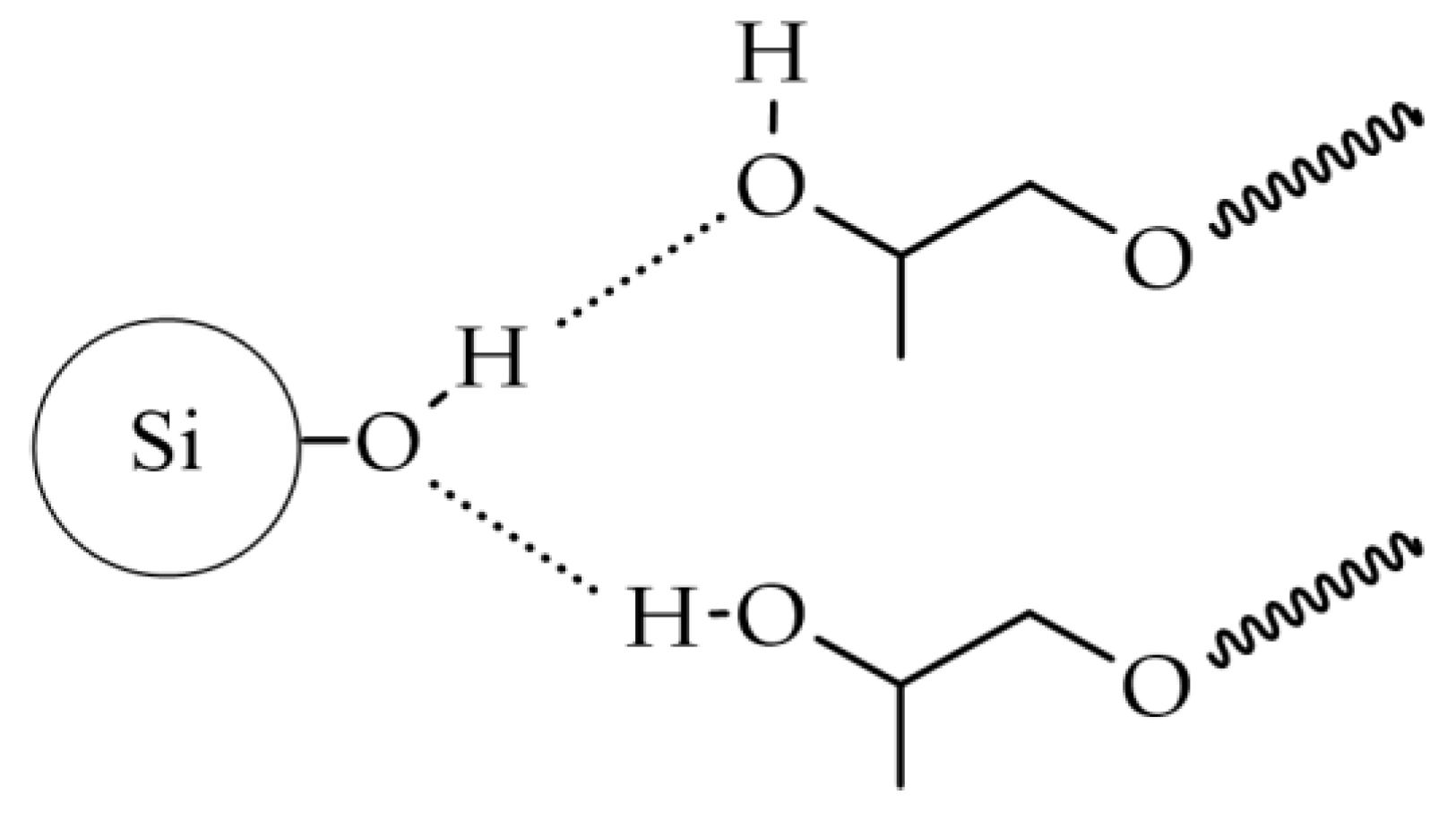

It is generally assumed that in strongly hydrogen-bonding liquids, a solvation layer forms on the silica surface through hydrogen bonding between the liquid molecules and surface silanol groups (Si-OH) [

27]. The change in viscosity is attributed to the interaction of the hydroxyl groups present at the ends of the chain with the nanosilica surface, as shown in

Figure 4.

Additionally, the viscosity of the system at low shear rates is lower for star-shaped oligo(oxypropylene). This is a desirable feature in the context of using composites as electrolytes for li-ion cells because the ionic conductivity is closely related to the viscosity of the system. Due to the change in viscosity over twenty times greater for a fluid made of 20 wt% SiO₂ with star-shaped oligo(oxypropylene), we decided to obtain electrolytes from it and further analyze them. Moreover, the shear thickening fluid made of star-shaped oligo(oxypropylene), like the oligomer itself, does not crystallize in the entire range of tested temperatures. It is characterized by a low glass transition temperature of -62.3 °C (

Figure 2d). Therefore, nanosilica does not act as crystallization nuclei, and the composite can retain its properties typical of a fluid over a wide temperature range.

3.3. Electrolytes Based on Star-Shaped Glycols

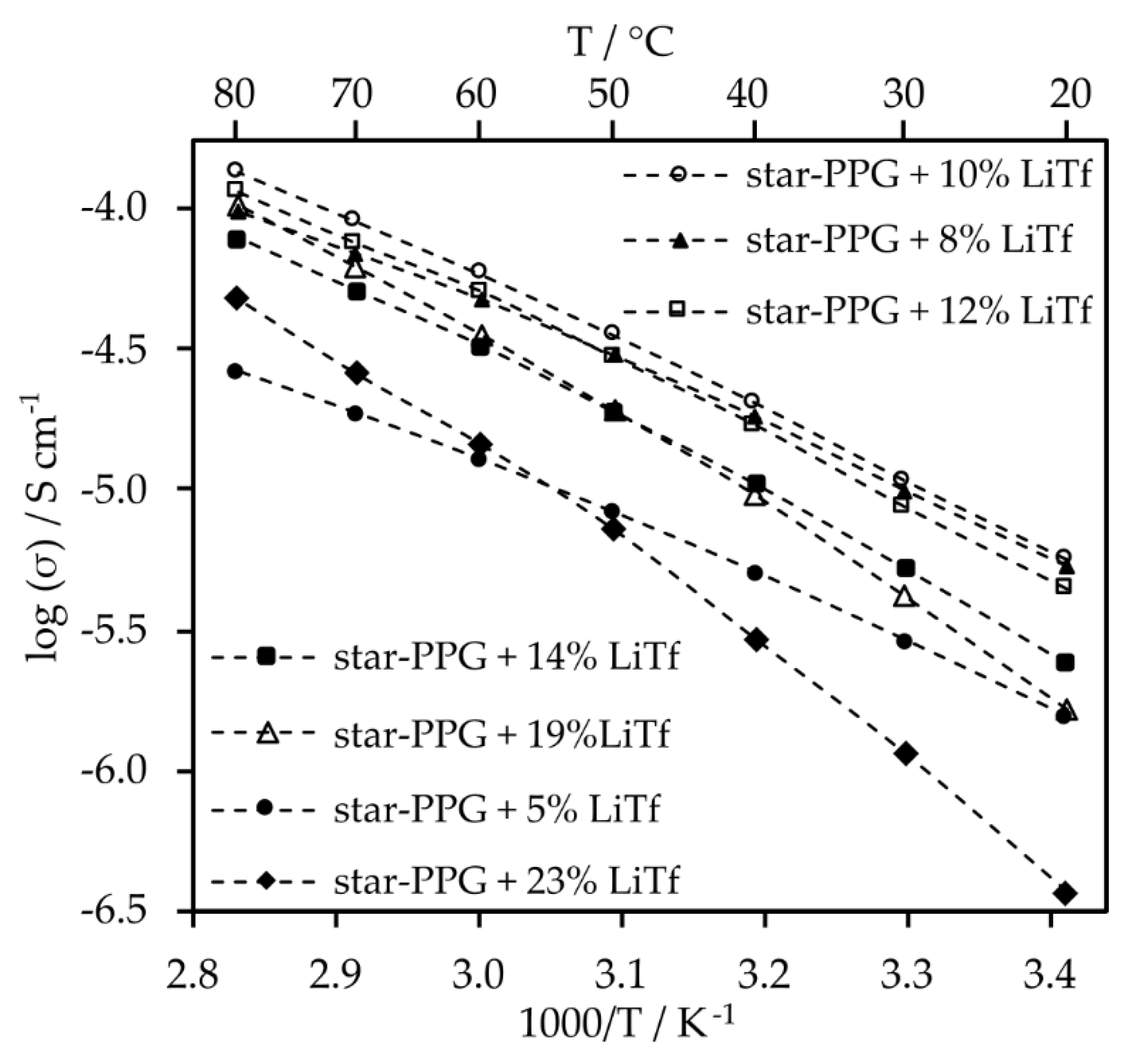

Measurements were carried out to determine the optimal salt content for electrolytes consisting only of star-shaped oxypropylene glycol. The analysis indicates that the optimal salt content in this solvent, which provided the highest conductivity values across the entire range of tested temperatures, is 10 wt%. Additionally, the conductivity of 10% LiTf solution at 20 °C is 5.1 × 10

-6 S cm

-1. However, at 80 °C, it increases to 1.2 × 10

-4 S cm

-1 (

Figure 5).

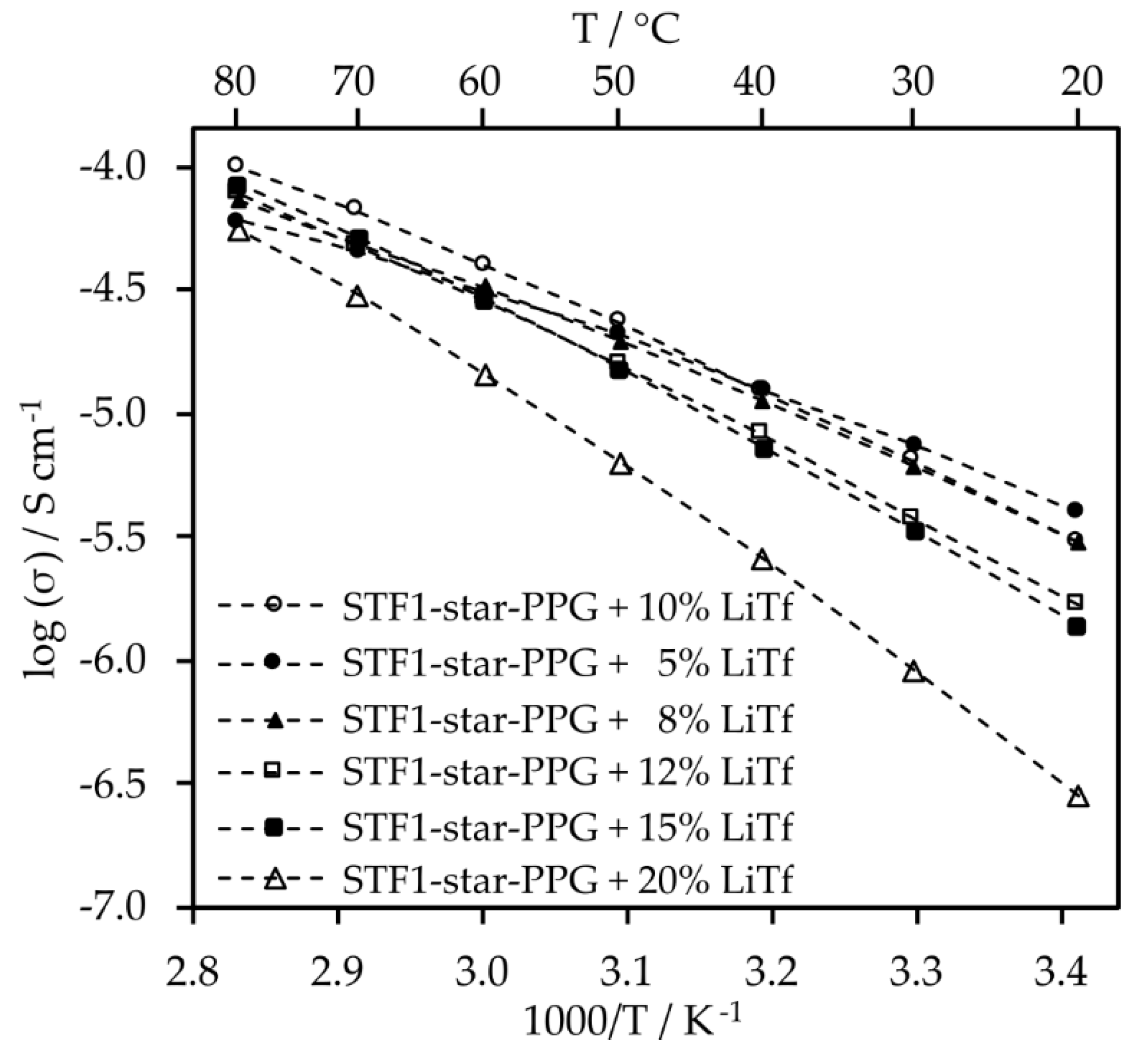

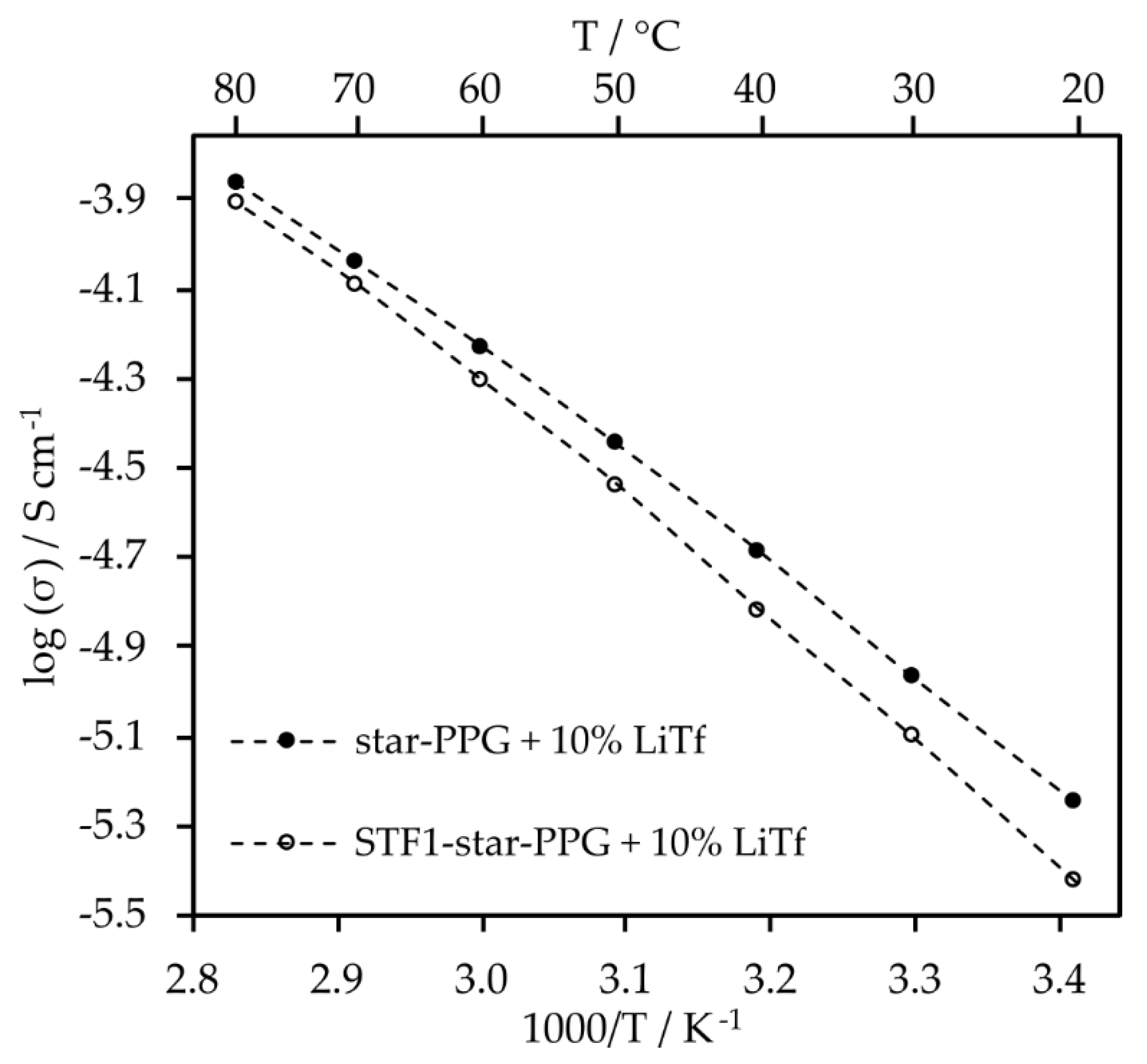

Optimization of salt content for electrolytes whose containing the addition of nanosilica was also conducted (

Figure 6).

Electrolytes with 10% salt content by weight exhibit similar conductivity values to those with 8% and 5% salt content. Moreover, at temperatures exceeding 40 °C, their conductivity surpasses that of electrolytes with other salt contents. Despite the significant viscosity of the composite electrolyte, the inclusion of nanosilica induces minor changes in conductivity (

Figure 7). This is likely attributed to enhanced lithium ion mobility resulting from Lewis acid-base interactions between SiO

2 particles and salt anions. Furthermore, such electrolytes exhibit very high transference numbers, which are 0.79 for the system with silica, and 0.85 for the electrolyte without silica.

We attribute this high transference number (t

+ = 0.85) to the structure of the oligomer itself, which contains hydroxyl groups at the ends of the oligoether arms. These groups can form hydrogen bonds between the star oligomer and the anions of the lithium salt. The anions of the triflate salt we use (CF

3SO

3-) contain several highly electronegative C-F groups, which can form extensive hydrogen-bond connections with the hydroxyl groups in the oligomer. The hydrogen bonds occurring in the system between the salt anions and the electrolyte matrix are responsible for the significant immobilization of the anions. This effect related to the immobilization of anions due to the formation of hydrogen bonds has been noticed and described for poly(vinylidene fluoride-hexafluoropropylene) based solid-state electrolytes [

28].

Our research shows that the introduction of silica with silanol groups on the surface of the particles slightly weakens this effect, as some of the end groups of the oligomer interact with the silica surface. The transference number remains high but is lower than in the system without silica (t+ = 0.79).

Furthermore, the rheological tests depicted in

Figure 2 demonstrate that electrolytes containing, in addition to lithium triflate, nanosilica, and star-shaped propylene glycol, exhibit a viscosity jump of 1187 Pa s, which is a value approximately 19 times higher than in the that of an electrolyte containing a mixture of EC and DMC carbonates as solvents [

24].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemical and Reagents

Propylene oxide (99%), ethylene oxide (99,8%), potassium (99,5%), 1,1,1-tris(hydroxymethyl)propane (98%), tetrahydrofuran (anhydrous, 99,9%) silica (declared grain size 7 nm), AmberLite IR120 ion exchange resin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. Methanol (analytical grade) was purchased from POCH. Lithium trifluoromethanesulfonate (LiTf, LiCF3SO3) (96%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, dried under reduced pressure at 130°C and kept in an argon atmosphere. Metallic lithium was used in the form of a ribbon, 1.5 mm thick and 100 mm wide, purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

4.2. Experimental Techniques

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was used to assess the type and quality of phase transformations occurring in the tested materials. Measurements were carried out on Q2000 differential scanning calorimeter in the -80 to 200 ˚C temperature range with heating/cooling rate of 10 ˚C/min in hermetically closed aluminum vessels. All samples were prepared in an Ar-filled glovebox.

The chemical structure of star-shaped glycols was characterized by 1H and 13C spectroscopy in solutions in CDCl3 (Varian Mercury VXR 400 MHz).

MALDI-Tof measurements were performed using an UltrafleXtreme mass spectrometer from Bruker Daltonics. Trans-2-[3-(4-tert-butylphenyl)-2-methyl-propenylidene]malononitrile (DCTB) was used as the matrix. Samples were dissolved in chloroform or THF.

Ionic conductivity of the electrolytes was determined via impedance measurements using a VSP-3e potentiostat (Bio-Logic) within the frequency range from 500 kHz – 1 Hz and the temperature range from 20 to 80 °C. The samples were stored in symmetrical cells with stainless steel electrodes. Ionic conductivity was calculated according to the equation:

where R represents the resistance determined from the impedance measurement, S is the surface area of the electrolyte and l is the thickness of the electrolyte.

The transference number (t

+) of lithium cations was determined using the polarization method with the Bruce-Vincent correction. According to this method, the electrolyte was placed in a symmetrical Li|electrolyte|Li system. A constant bias voltage of 20 mV was applied to the system. Then the system was monitored until the polarization current reached the steady state (I

ss value). Additionally, impedance spectra were recorded before and after polarization. The equation was used to calculate the transference number:

where U represents applied polarization potential, I

0 and I

SS represents the initial and steady-state currents and respectively, R

0 and R

SS represents the corresponding initial andsteady-state resistances of the solid-state interface calculated from the impedance plots before and after polarization.

Steady-state rheological measurements were carried out using a Kinexus Pro rotational rheometer (Malvern) operating in a plate-plate system with a plate with a diameter of 20 mm. The measurement temperature was 25 °C, the width of the measurement gap was 0.3 mm. The measurement time was 5 min, measurement range 0.01-1000 s-1, 10 measurement points per decade. Immediately before the measurement, the sample was sheared at an exponentially increasing shear rate to 0.01 to 0.1 s-1 for 2 min.

5. Conclusions

An innovative electrolyte for lithium-ion cells has been presented, designed to enhance the operational safety of lithium-ion batteries, particularly during impact. The developed electrolyte exhibits the properties of a shear thickening fluid and is free of flammable, low-molecular-weight organic solvents. The matrix used was synthesized via anionic polymerization, an approach that resulted in well-defined products that did not crystallize in the temperature range tested. Additionally, the synthesized three-armed oli-go(propylene oxide) is characterized by a low glass transition temperature of -64 °C. The shear thickening effect was achieved by incorporating a rheological modifier in the form of nanosilica. The lithium salt content (LiCF3SO3) was optimized to 10% by weight, yielding conductivities of 10-6 S cm-1 at 20 °C and 10-4 S cm-1 at 80 °C, along with exceptionally high transference numbers of 0.79, likely due to the oligomer's structure. Furthermore, it was observed that the addition of silica had a minimal impact on the electrochemical parameters of the electrolyte and the phase transformation temperatures, yet enabled the creation of a shear thickening electrolyte with a viscosity increase of nearly 1200 Pa s. Consequently, systems comprising branched oligo(propylene oxide) with silica and lithium salt represent a novel class of shear thickening electrolytes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Spectra 1H NMR of star-shaped oxypropylene glycol obtained via anionic polimerization; Figure S2: Spectra 13C NMR of star-shaped oxypropylene glycol obtained via anionic polimerization; Figure S3: MALDI-ToF spectrogram of star-shaped oxypropylene glycol.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Z.-M.; methodology, M.K. and E.Z.-M.; validation, M.S. and A.Cz.; formal analysis, M.S., A.Cz. and M.K.; investigation, M.S. and M.K.; data curation, M.S., A.Cz., M.K. and E.Z.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, A.Cz. and E.Z.-M.; visualization, M.S. and A.Cz.; supervision, E.Z.-M.; project administration, E.Z.-M.; funding acquisition, E.Z.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by (POB Energy, Energytech-2, No. 1820/39/Z01/POB7/2021) of Warsaw University of Technology within the Excellence Initiative: Research University (IDUB) programme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be available upon a reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, Q.; Ping, P.; Zhao, X.; Chu, G.; Sun, J.; Chen, C. Thermal runaway caused fire and explosion of lithium-ion battery. Journal of Power Sources 2012, 208, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chombo, P. V.; Laoonual, Y. A review of safety strategies of a Li-ion battery. Journal of Power Sources 2020, 478, 228649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M. K. , Mevawalla, A., Aziz, A., Panchal, S., Xie, Y., & Fowler, M. A review of lithium-ion battery thermal runaway modeling and diagnosis approaches. Processes 2022, 10, 1192. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K. ; Nonaqueous liquid electrolytes for lithium-based rechargeable batteries. Chemical Reviews 2004, 104, 4303–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, J.; Fan, L.; Kong, X.; Lu, Y. Progress in electrolytes for rechargeable Li-based batteries and beyond. Green Energy & Environment 2016, 1, 18–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalhoff, J.; Eshetu, G. G.; Bresser, D.; Passerini, S. Safer electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries: state of the art and perspectives. ChemSusChem 2015, 8, 2154–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, J. T. ; Lithium-Ion Battery Chemistries: A Primer, 1st ed; Elsevier, 2019.

- Battig, A.; Markwart, J. C.; Wurm, F. R.; Schartel, B. Hyperbranched phosphorus flame retardants: Multifunctional additives for epoxy resins. Polymer chemistry 2019, 10, 4346–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, K.; Tran, Y.H.T.; Kwak, S.; Han, J.; Song, S. W. ; Design of fire-resistant liquid electrolyte formulation for safe and long-cycled lithium-ion batteries. Advanced Functional Materials 2021, 31, 2106102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.C.; Gonçalves, R.; Costa, C.M.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Toward Sustainable Solid Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. CS Omega 2022, 7, 14457–14464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavers, H.; Molaiyan, P.; Abdollahifar, M.; Lassi, U.; Kwade, A. Perspectives on Improving the Safety and Sustainability of High Voltage Lithium-Ion Batteries Through the Electrolyte and Separator Region. Advanced Energy Materials 2022, 12, 2200147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M. Solid Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium Batteries: A Tribute to Michel Armand. Inorganics 2022, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, H.A. Shear-Thickening (“Dilatancy”) in Suspensions of Nonaggregating Solid Particles Dispersed in Newtonian Liquids. J. Rheol. 1989, 33, 329–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, N.; Wetzel, E. Advanced body armor utilizing shear thickening fluids. US2006023 4577A1, 2006.

- Haq, S.; Morley, C.J. Fibrous armour material. US981 6788B2, 2017.

- Williams, T.H.; Day, J.; Pickard, S. ; Surgical and medical garments and materials incorporating shear thickening fluids. US2009025 5023A1, 2009.

- Seshimo, K. Viscoelastic damper. US475 9428A, 1988.

- Hesse, H. Rotary shock absorber. US450 3952A, 1985.

- Rosenberg, B. Nonlinear energy absorption system. US383 3952A, 1974.

- Zhang, X.Z.; Li, W.H.; Gong, X.L. The rheology of shear thickening fluid (STF) and the dynamic per-formance of an STF-filled damper. Smart Mater. Struct. 2008, 17, 035027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafran, M.; Antosik, A.; Głuszek, M.; Falkowski, P.; Bobryk, E.; Żurowski, R.; Rokicki, G.; Tryznowski, M.; Kaczorowski, M.; Leonowicz, M.; Wierzbicki, Ł.; Kryjak, M.; Szczygieł, M. Football shin guard with increased degree of energy absorbing capacity. PL23 1757B1, 2019.

- Ding, J.; Li, W.; Shen, S.Z. Research and applications of shear thickening fluids. Recent Pat. Mater. Sci. 2011, 4, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Wang, C.; Li, W.; Bussell, T.; Ding, J. Electrolytes with reversible switch between liquid and solid phases. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2020, 21, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Tian, T.; Meng, Q.; et al. Smart Multifunctional Fluids for Lithium Ion Batteries: Enhanced Rate Performance and Intrinsic Mechanical Protection. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veith, G.M.; Armstrong, B.L.; Wang, H.; Kalnaus, S.; Tenhaeff, W.E.; Patterson, M.L. Shear Thickening Electrolytes for High Impact Resistant Batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 9, 2084–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Liang, X.; Liu, B.; Deng, H. Research Progress of Shear Thickening Electrolyte Based on Liquid–Solid Conversion Mechanism. Batteries 2023, 9, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, S.R.; Walls, H.J.; Khan, S.A. Rheology of Silica Dispersions in Organic Liquids: New Evidence for Solvation Forces Dictated by Hydrogen Bonding. Langmuir 2000, 16, 7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Kou, H.; Chang, R.; Zhou, X.; Yang, J.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Y. Hydrogen-Bond-Driven High Ionic Conductivity, Li+ Transfer Number and Lithium Interface Stability of Poly (Vinylidene Fluoride-Hexafluoropropylene) Based Solid-State Electrolytes. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).