Submitted:

22 June 2024

Posted:

24 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

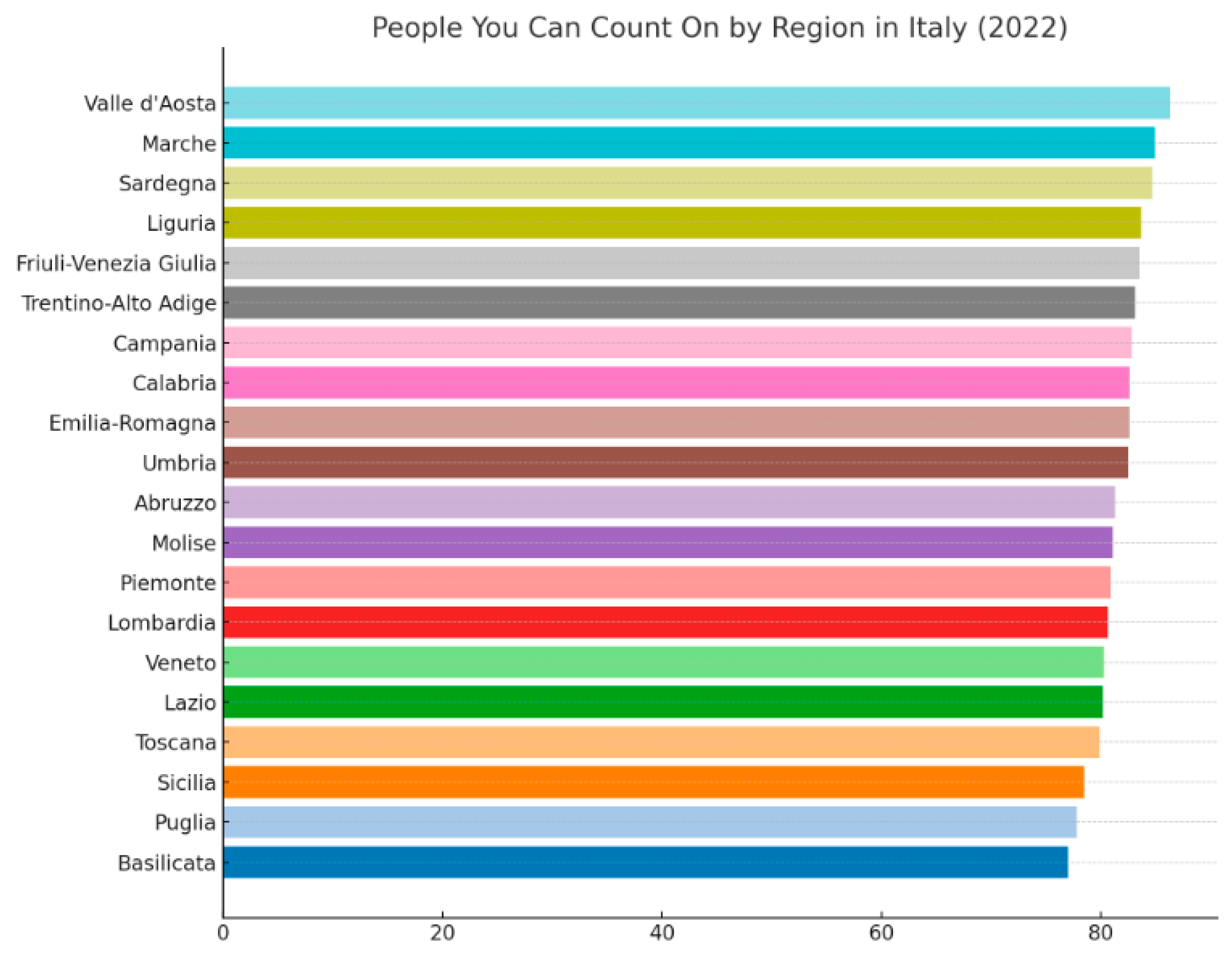

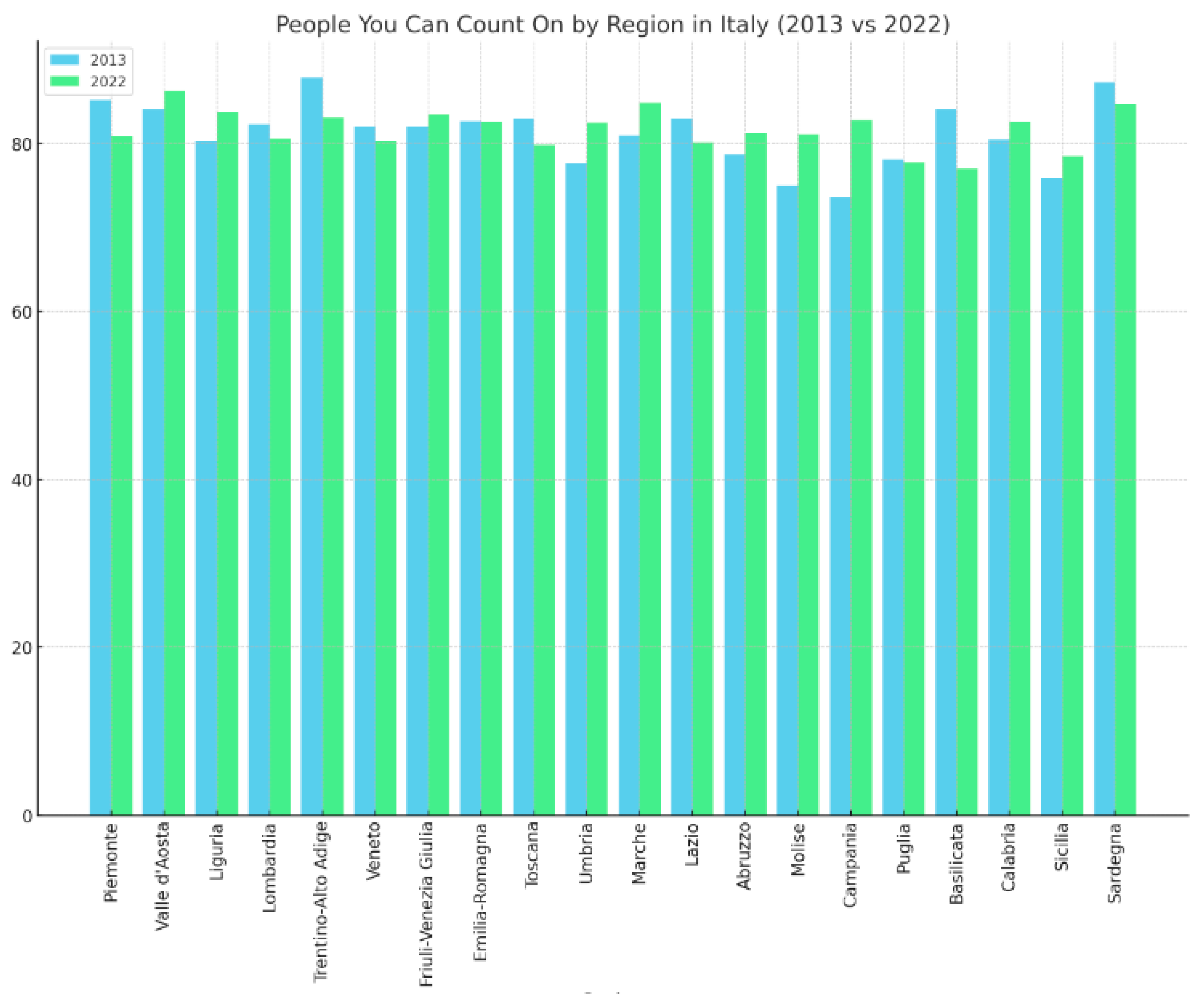

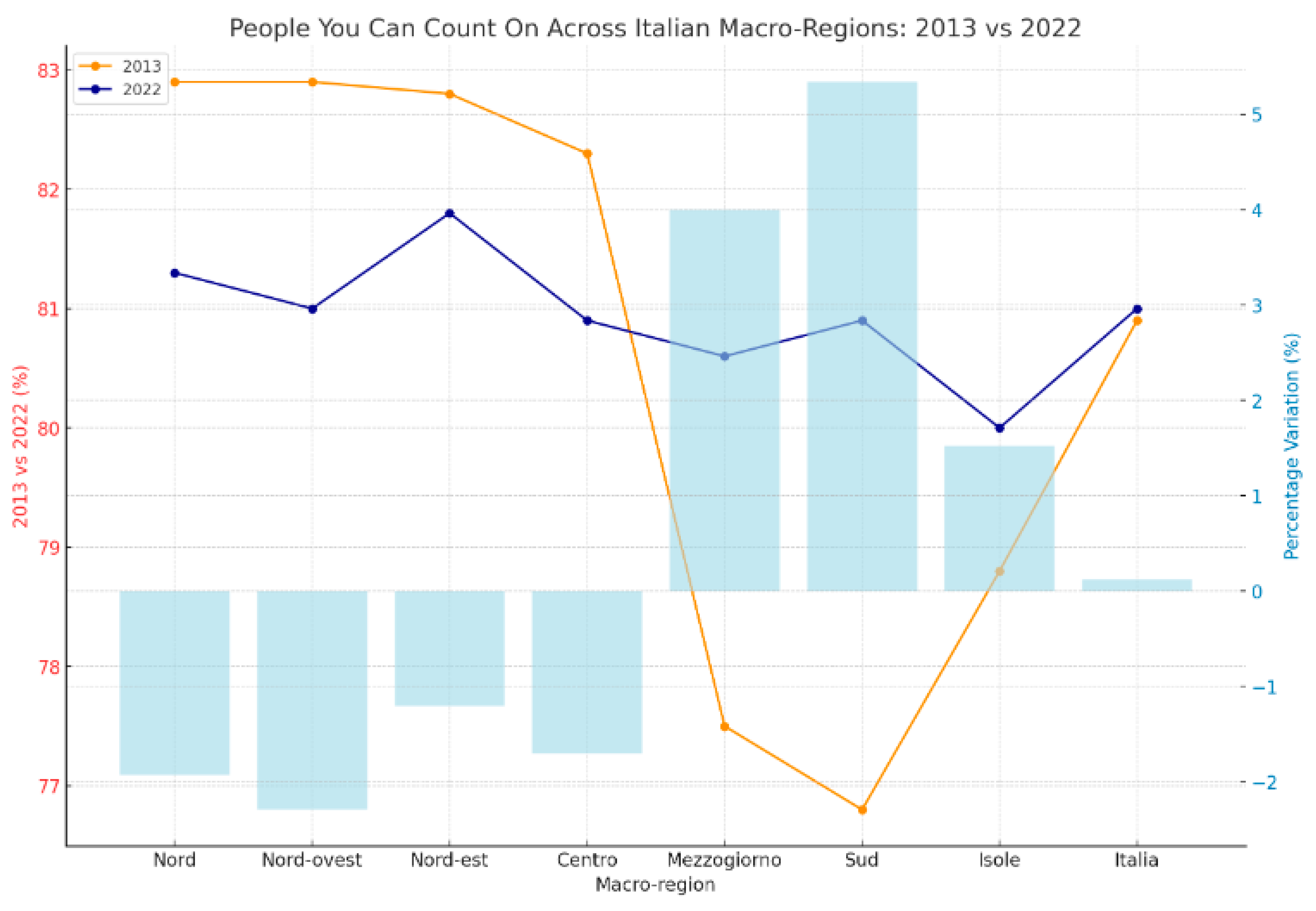

3. Rankings of Regions and Macro-Regions in the Sense of PYCC

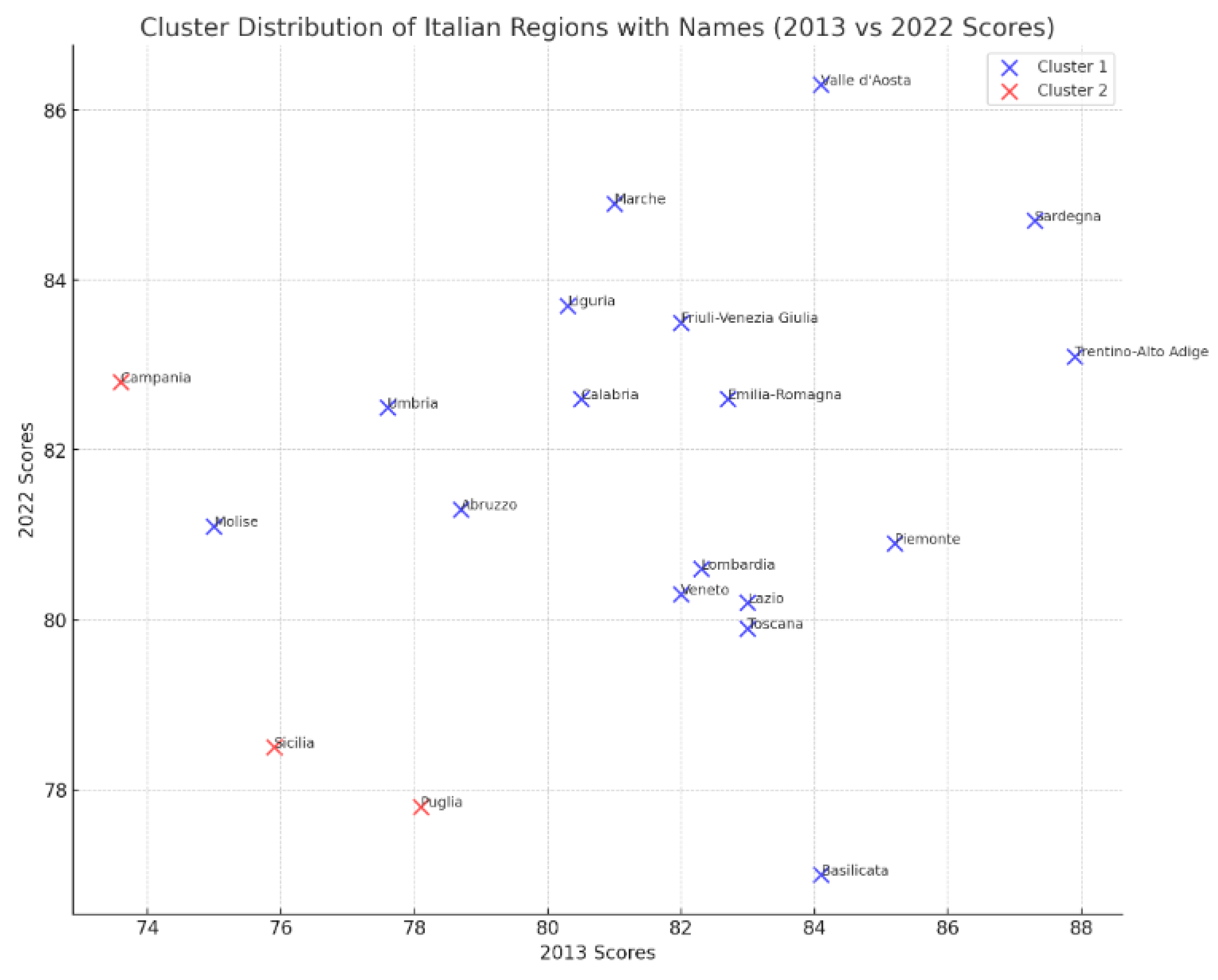

4. Clusterization with k-Means Algorithm Optimized with the Silhouette Coefficient

- Cluster 1 includes: Piemonte, Valle d’Aosta, Liguria, Lombardia, Trentino-Alto Adige, Veneto, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Emilia-Romagna, Toscana, Umbria, Marche, Lazio, Abruzzo, Molise, Basilicata, Calabria, and Sardegna.

- Cluster 2 includes: Campania, Puglia, and Sicilia.

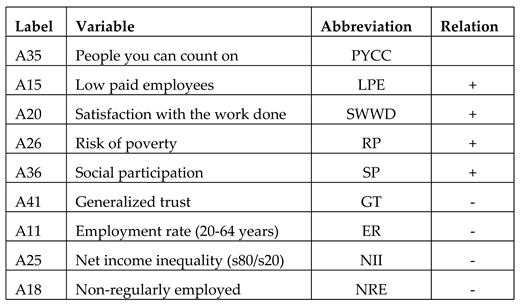

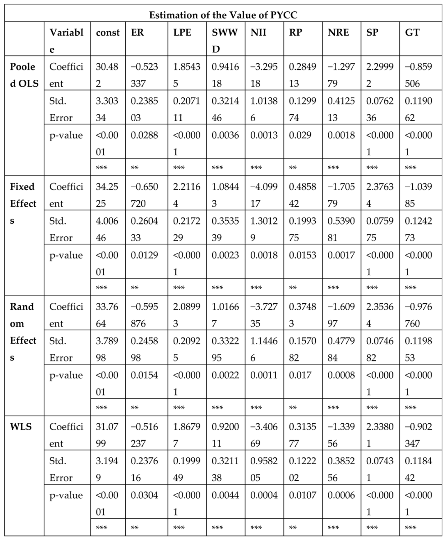

5. Econometric Model

- LPE: the positive relationship between PYCC and LPE can be explored through the lens of social support networks and solidarity that often form in work contexts characterized by less favourable economic conditions. This positive link suggests that, despite economic challenges, there are positive social and relational dynamics emerging in work environments with a prevalence of low wages. In work contexts where employees face similar economic conditions, often characterized by low wages, a strong sense of solidarity can develop. Sharing common challenges can foster a supportive environment, where workers tend to help each other both professionally and personally. People working under conditions of low pay may be more inclined to build social support networks at the workplace and beyond. These networks can provide practical assistance, such as sharing caregiving responsibilities or support in financial emergencies, as well as offering emotional support. Working in low-wage contexts can also lead to shared values and a sense of belonging. This collective identity can strengthen interpersonal relationships and promote a culture of mutual support. People experiencing similar economic conditions tend to have higher levels of empathy and mutual understanding. This can translate into closer and more meaningful relationships, where there is a greater inclination to offer and receive support. In low-wage contexts, support can extend beyond the workplace, involving families and local communities. Communities may organize shared resources or mutual aid initiatives to help those facing economic difficulties. Despite economic challenges, LPE can benefit from robust and meaningful social support networks, highlighting how shared difficulties can act as a catalyst for forming strong interpersonal bonds and support networks. This demonstrates the importance of social and relational dimensions in mitigating the negative impacts of economic hardships and in promoting individual and collective well-being.

- SWWD: the positive relationship between PYCC and SWWD highlights how having a supportive network at work can significantly enhance an individual’s satisfaction with their job. This connection suggests that when employees feel supported by their colleagues and superiors, they are more likely to experience higher levels of job satisfaction. The presence of supportive colleagues and managers can provide a buffer against workplace stress and challenges. Emotional support from co-workers can foster a sense of belonging and well-being, contributing to overall job satisfaction. A work environment where employees can rely on each other encourages collaboration and effective teamwork. When people feel they are part of a cohesive team, working towards common goals, their engagement and satisfaction with their job increase. Having mentors and supportive peers can facilitate opportunities for learning and professional growth. Employees who feel supported in their career development are more likely to be satisfied with their job, as they see a path for progression and improvement. A supportive network contributes to a positive work culture, where individuals feel valued and recognized. This positive environment can significantly boost job satisfaction, as employees feel their contributions are appreciated and that they are an integral part of the organization. When employees have a reliable support system at work, they are less likely to consider leaving their job. High job satisfaction, fostered by supportive relationships, contributes to higher retention rates within organizations. Support from co-workers and supervisors can enhance job performance. Employees who feel supported are more motivated and engaged, leading to better outcomes and further increasing job satisfaction. In essence, the positive correlation between having PYYC and experiencing SWWD underscores the importance of fostering supportive relationships in the workplace. Organizations that prioritize building a collaborative and supportive culture can enhance employee satisfaction, which in turn can lead to improved performance, reduced turnover, and a more positive work environment.

- RP: a positive relationship between PYYC and RP might seem counterintuitive at first glance, as it suggests that having a supportive network is associated with a higher risk of poverty. However, this interpretation might need clarification or a different perspective to fully understand the underlying dynamics. Typically, one would expect that having a strong network of support would decrease the risk of poverty by providing individuals with resources, emotional support, and opportunities that could help them avoid or escape poor economic conditions. In communities or groups where the risk of poverty is high, strong social support networks might develop as a necessary means of survival and mutual aid. In these contexts, the presence of PYYC is crucial and more prevalent because of the shared challenges. Therefore, the positive relationship does not imply that support networks cause poverty but rather that in environments where poverty risk is high, supportive networks are essential and become more visible or necessary. Individuals facing economic hardships often rely on extended family, friends, and community networks for support. This could include financial assistance, sharing of resources, or providing care services for each other. The strong presence of these support networks among those at risk of poverty highlights how essential they are for mitigating the immediate impacts of economic challenges. In areas with high poverty risks, the development of social capital—reflected in networks of mutual support and solidarity—can be particularly strong. People in these communities may often rely on one another to navigate economic difficulties, leading to a positive correlation between having people to rely on and experiencing a higher risk of poverty. It is important to clarify that the positive relationship here does not suggest that supportive networks increase the risk of poverty; rather, it reflects the importance and prevalence of support networks within communities where the risk of poverty is already high. These networks play a critical role in providing emotional, financial, and practical support, helping individuals and families cope with economic challenges and potentially aiding in poverty alleviation efforts.

- SP: A positive relationship between PYCC and SP indicates that individuals who have a strong support network are more likely to be involved in social activities and community engagement. This correlation highlights the significant role that interpersonal relationships and social support play in encouraging active participation in social, cultural, and community events. Having supportive people in one’s life can boost confidence and motivation to engage in social activities. Knowing that they have others to rely on for encouragement or companionship can make individuals more inclined to participate in social events and community activities. Social networks often serve as a valuable source of information about social activities, volunteer opportunities, and community events. People embedded in a network of supportive relationships are more likely to be informed about and encouraged to take part in these activities. Supportive networks frequently consist of individuals with shared interests and values. This common ground can foster group participation in social and community activities, leading to higher levels of social participation among the network’s members. For some, participating in social activities can be challenging due to logistical, financial, or emotional barriers. Having people to rely on can provide the necessary support to overcome these obstacles, whether it is through sharing transportation, helping with costs, or offering emotional encouragement. Participation in community and social activities often leads to the strengthening of community ties and the building of new supportive relationships. This, in turn, creates a positive feedback loop where increased social participation enhances community cohesion, which further supports individual engagement. Engaging in social participation contributes to personal resilience and well-being, aspects that are supported and reinforced by having a reliable social network. The sense of belonging and purpose gained through active participation can improve mental health and overall life satisfaction. In summary, the positive correlation between having PYCC and SP underscores the importance of social support networks in fostering an active, engaged lifestyle. Supportive relationships not only encourage individuals to partake in social and community activities but also enhance the collective vibrancy and cohesiveness of communities as a whole.

- There is a negative relationship between PYCC and the following variables namely:

- GT: A negative relationship between PYCC and GT suggests that in environments where individuals have strong, reliable support networks, there might be a lower level of trust towards society. When people have close-knit support networks, they may develop strong in-group bonds that inadvertently lead to reduced trust outside of their immediate circle. This “us vs. them” mentality strengthens ties within the group but can erode generalized trust in broader society. Individuals who rely heavily on a tight support network might feel less need to trust or engage with those outside their immediate circle. This self-sufficiency can reduce the perceived necessity to build trust with others in the wider community, leading to lower levels of generalized trust. In some cultures or communities, the emphasis on strong familial or community ties may come with an inherent wariness of external entities or individuals. This cultural norm can foster deep trust within specific groups while simultaneously lowering trust in broader society. Support networks often function as protective entities. When such networks are strong, individuals within them may become more risk-averse, viewing external interactions as unnecessary or potentially threatening, thereby reducing their level of generalized trust. In situations where individuals have experienced betrayal or exploitation by those outside their immediate support network, there may be a tendency to retreat into more trusted inner circles. Such experiences can significantly diminish one’s propensity to trust people in general. Strong reliance on personal networks might be more pronounced in communities facing economic or social challenges, where trust in institutions and societal structures is low. In these contexts, the reliance on PYCC becomes a necessity rather than a choice, reflecting broader issues of systemic distrust. To address this negative relationship and promote generalized trust, interventions might focus on building bridges between different social groups, fostering inclusivity, and encouraging positive interactions across community divides. Efforts to strengthen social cohesion and trust in institutions, alongside promoting the benefits of diverse and open social networks, could also help counteract the tendency towards insularity and enhance generalized trust within the broader society.

- ER: a negative relationship between PYCC and the ER might initially seem counterintuitive, as strong social networks are often thought to contribute positively to job opportunities through connections and information sharing. However, this correlation could highlight underlying social and economic dynamics that merit closer examination. In communities with robust support systems, individuals might rely more on their network for financial and material support, possibly reducing the immediate necessity or urgency to seek employment. This could be particularly true in cultures or contexts where family or community support is expected and normalized over individual economic independence. Individuals with strong support networks might be more inclined to withdraw from the job market, especially after prolonged periods of unsuccessful job searching. The emotional and sometimes financial support they receive can afford them the luxury of not participating in the labour force, inadvertently affecting the employment rate. In some cases, strong support networks facilitate engagement in informal or non-traditional employment sectors not captured by standard employment statistics. For instance, individuals might participate in family businesses, informal caregiving, or community-based work, which may not be reflected in the official employment rate for ages 20-64. The relationship could also reflect regional economic conditions where strong community bonds are essential for survival due to a lack of formal employment opportunities. In such areas, the employment rate might be lower, not because social networks directly discourage work, but because the economy offers fewer formal job opportunities, and people rely more on each other for support. Areas with lower employment rates might see a higher out-migration of individuals seeking work elsewhere, leaving behind a population with stronger ties to the local community. These individuals may have a greater reliance on their social networks due to reduced economic opportunities in their locality. In societies with generous social welfare systems, individuals might not feel as compelled to find employment due to the availability of social support. This could lead to a situation where strong social networks exist alongside a lower employment rate, as the pressure to seek employment is mitigated by the welfare support. Addressing this negative relationship requires a multifaceted approach, focusing on enhancing economic opportunities, providing targeted employment services, and encouraging the positive aspects of social networks in facilitating job search and employment. Policies aimed at economic development, education, and training programs, as well as incentives for entrepreneurship, could help transform the potential of social networks into a driving force for increasing employment rates among the 20-64 age group.

- NII: a negative relationship between PYCC and NII suggests that in communities or societies where individuals have strong support networks, there tends to be lower income inequality. In societies with strong support networks, there is often a culture of sharing resources and providing mutual aid. This can help mitigate financial disparities by ensuring that those who are less well off receive support from their community, thereby reducing the gap between the highest and lowest earners. Strong social networks foster social cohesion, which can lead to more collective action aimed at addressing issues of inequality. Communities that are tightly knit are more likely to advocate for policies and practices that benefit the broader society, including welfare programs, progressive taxation, and other redistributive measures. Individuals with reliable support networks have better resilience in the face of economic downturns. The ability to rely on others for temporary financial assistance, job leads, or even entrepreneurial opportunities can prevent people from falling into poverty, which, on a larger scale, can contribute to reducing overall income inequality. Social networks increase an individual’s social capital, providing access to information, resources, and opportunities that can lead to better employment and income prospects. When widespread across a society, this can lead to a more equitable distribution of economic resources, as more people can improve their socioeconomic status. Support networks often play a crucial role in educational achievement and occupational success by providing mentorship, advice, and connections. This support can level the playing field, especially for individuals from less privileged backgrounds, contributing to reduced income inequality. Societies with strong social bonds may also show higher levels of engagement in political and policy-making processes. This engagement can lead to the support and implementation of policies that aim to reduce income inequality, as there is a collective understanding of the importance of supporting every member of the community. In summary, the negative relationship between PYCC and NII highlights the role of social support networks in fostering economic equity. By sharing resources, advocating for fair policies, and providing individual support, these networks can help reduce the disparities in income distribution, contributing to a more balanced and cohesive society.

- NRE: A negative relationship between PYCC and NRE suggests that in contexts where individuals have strong and reliable support networks, there tends to be a lower presence of irregular employment. Having a solid network can facilitate access to more stable and regular job opportunities through recommendations and information sharing. People with extensive social supports might be better positioned to find jobs with long-term contracts or full-time positions thanks to the shared information and opportunities within their networks. Support networks provide not just practical assistance in job searching but also emotional support throughout the process. This can reduce the level of stress associated with job precarity and increase individual resilience, making people less inclined to accept irregular jobs out of desperation or immediate necessity. Individuals supported by a robust network of contacts might have greater opportunities to access educational and training resources that enhance their employability in more stable and higher-quality jobs. Family or community support can facilitate investment in education and ongoing training, key elements for accessing more stable job opportunities. People with strong support networks might have a lower tolerance for precarious and irregular working conditions, feeling more secure in rejecting unsatisfactory job offers. The economic and emotional security provided by their social support could allow them to actively seek jobs that offer greater stability and satisfaction. In some cultures or social contexts, there is a strong expectation towards job stability as a social norm and a sign of success. Support networks in these contexts can, therefore, encourage and facilitate the pursuit of regular employment as the desirable path. However, it is important to note that this relationship can vary significantly depending on the socio-economic context, local labour market dynamics, and prevailing social policies. Interventions aimed at strengthening social support networks, along with inclusive labour policies that promote regular and quality employment, can help mitigate the negative effects of irregular employment on social cohesion and individual well-being.

6. Policy Implications

7. Conclusions

References

- Akhtar, S. (2023). Behavioral economics and the problem of altruism: The review of Austrian economics. The Review of Austrian Economics, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, C. G., Cabrales, A., Dolls, M., Durante, R., & Windsteiger, L. (2021). Calamities, common interests, shared identity: what shapes altruism and reciprocity?

- Albanese, M. (2021). Some epistemological reflections on the concept of Homo Economicus. Specialized discourses of well-being and human development, 32.

- Baldassarri, D.; Abascal, M. Diversity and prosocial behavior. Science 2020, 369, 1183–1187. [CrossRef]

- Benner, C., & Pastor, M. (2021). Solidarity economics: Why mutuality and movements matter. John Wiley & Sons.

- Benner, C., & Pastor, M. (2021). Solidarity economics: Why mutuality and movements matter. John Wiley & Sons.

- Bertogg, A.; Koos, S. Socio-economic position and local solidarity in times of crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of informal helping arrangements in Germany. Res. Soc. Strat. Mobil. 2021, 74, 100612–100612. [CrossRef]

- Cappelen, A. W., Falch, R., Sørensen, E. Ø., & Tungodden, B. (2021). Solidarity and fairness in times of crisis. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 186, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Choquette-Levy, N.; Wildemeersch, M.; Santos, F.P.; Levin, S.A.; Oppenheimer, M.; Weber, E.U. Prosocial preferences improve climate risk management in subsistence farming communities. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Cimagalli, F. Is There a Place for Altruism in Sociological Thought?. Hum. Arenas 2020, 3, 52–66. [CrossRef]

- Costa, J. F. (2021). Solidarity Is Not Reciprocal Altruism. In Unchaining Solidarity: On Mutual Aid and Anarchism with Catherine Malabou (pp. 163-178). Rowman & Littlefield International.

- Eriawaty, E. T. D., Widjaja, S. U. M., & Wahyono, H. (2022). Rationality, Morality, Lifestyle And Altruism In Local Wisdom Economic Activities Of Nyatu Sap Artisans. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 5781-5797.

- Fernández GG, E., Lahusen, C., & Kousis, M. (2021). Does organisation matter? Solidarity approaches among organisations and sectors in Europe. Sociological Research Online, 26(3), 649-671. [CrossRef]

- Gualda, E. Altruism, Solidarity and Responsibility from a Committed Sociology: Contributions to Society. Am. Sociol. 2021, 53, 29–43. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. D. (2020). Greed, need, and solidarity: The socialization of Homo economicus. In How Social Forces Impact the Economy (pp. 40-58). Routledge.

- Kawano, E. (2020). Solidarity economy: Building an economy for people and planet. In The New Systems Reader (pp. 285-302). Routledge.

- Konarik, V.; Melecky, A. Religiosity as a Driving Force of Altruistic Economic Preferences. Int. J. Bus. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2022, 10–29. [CrossRef]

- Mangone, E. (2020). Beyond the dichotomy between altruism and egoism: Society, relationship, and responsibility. IAP.

- Mangone, E. A new sociality for a solidarity-based society : the altruistic relationships. Derecho y Real. 2022, 20, 15–32. [CrossRef]

- Matthaei, J. (2020). Thinking beyond capitalism: social movements, revolution, and the solidarity economy. In A Research Agenda for Critical Political Economy (pp. 209-224). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Pearlman, S. Solidarity Over Charity: Mutual Aid as a Moral Alternative to Effective Altruism. Kennedy Inst. Ethic- J. 2023, 33, 167–199. [CrossRef]

- Salem, M. B. (2020). “God loves the rich.” The economic policy of Ennahda: liberalism in the service of social solidarity. Politics and Religion, 13(4), 695-718.

- Salustri, A. Social and solidarity economy and social and solidarity commons: Towards the (re)discovery of an ethic of the common good?. Ann. Public Cooperative Econ. 2021, 92, 13–32. [CrossRef]

- Siemoneit, A. Merit first, need and equality second: hierarchies of justice. Int. Rev. Econ. 2023, 70, 537–567. [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, P.; Kesting, S. An Institutional Economics of Gift?. J. Econ. Issues 2021, 55, 954–976. [CrossRef]

- Spaulonci Chiachia Matos de Oliveira, B. C. (2022). Homo Colaboratus Birth Within Complex Consumption. In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Social Problems (pp. 1-10). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Travlou, P., & Bernát, A. (2022). Solidarity and care economy in times of ‘crisis’: A view from Greece and Hungary between 2015 and 2020. In The Sharing Economy in Europe: Developments, Practices, and Contradictions (pp. 207-237). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- van Geest, P. (2021). The Indispensability of Theology for Enriching Economic Concepts. In Morality in the Marketplace (pp. 68-88). Brill.

- Ventura, L. (2023). The Social Enterprise Movement and the Birth of Hybrid Organisational Forms as Policy Response to the Growing Demand for Firm Altruism. The international handbook of Social Enterprise Law. Cham: Springer, 9-26. [CrossRef]

- Volosevici, D.; Grigorescu, D. Individual, employers and organizational citizenship behaviour. Jus et Civ. – A J. Soc. Leg. Stud. 2021, 8(62), 43–50. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).