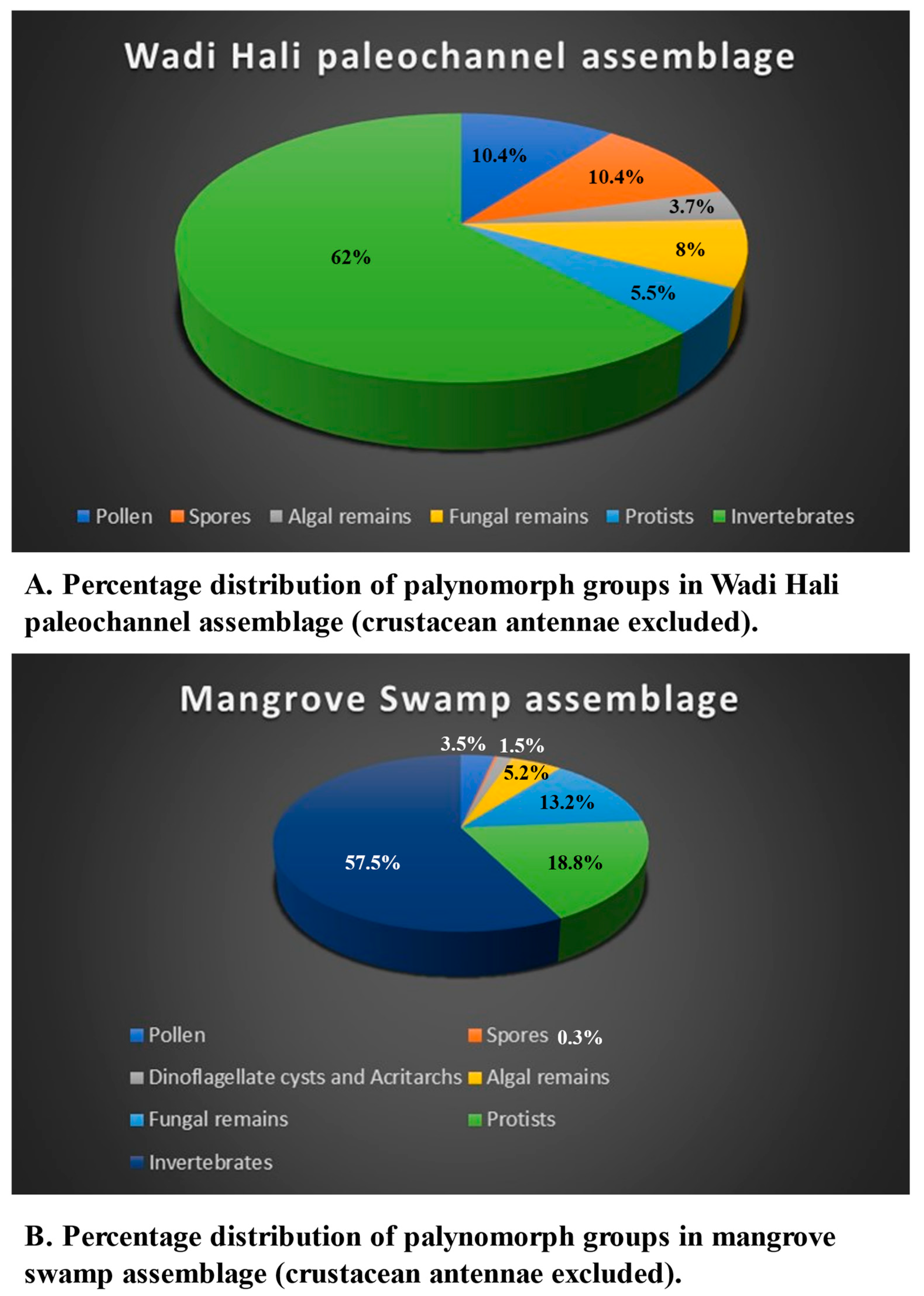

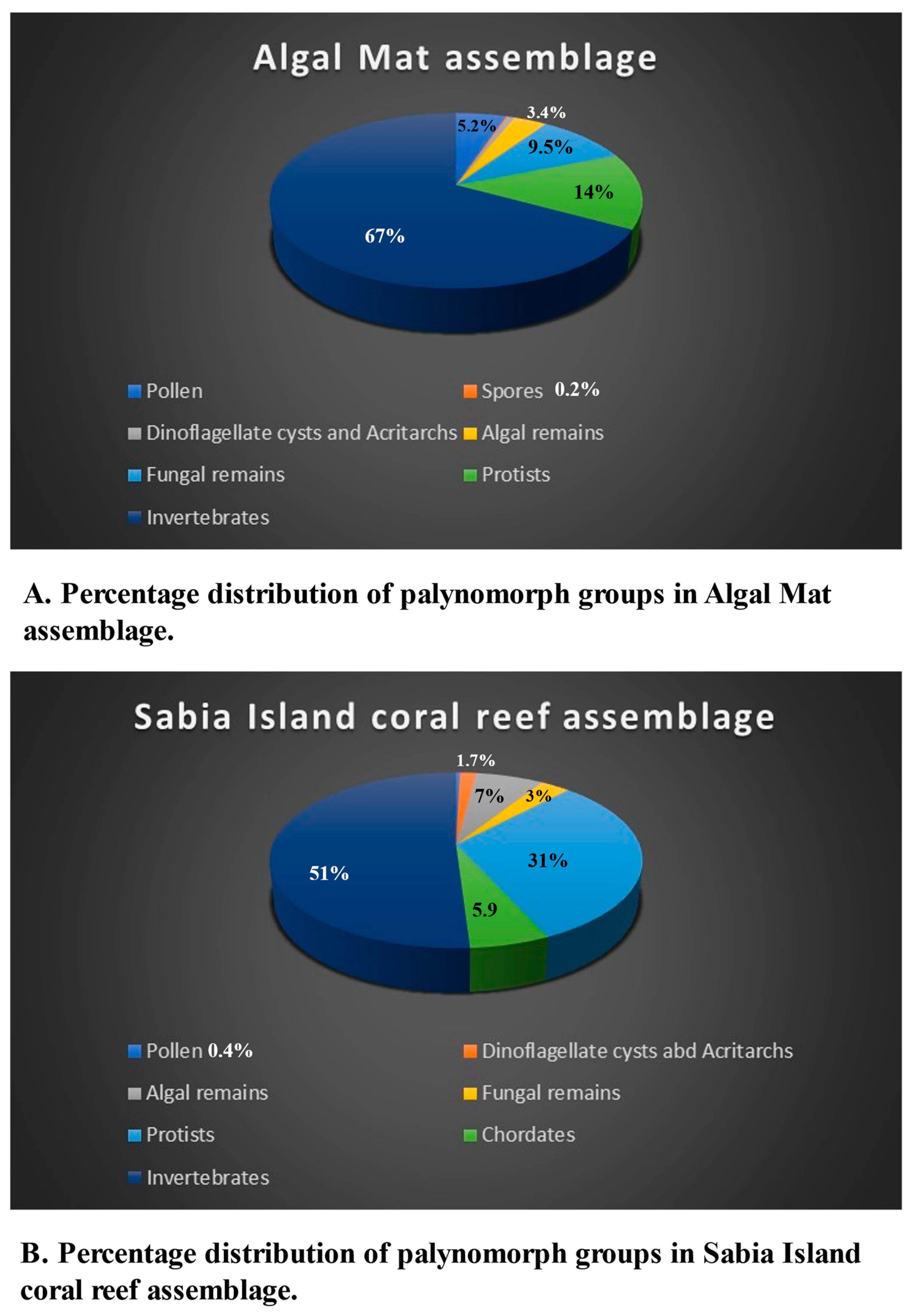

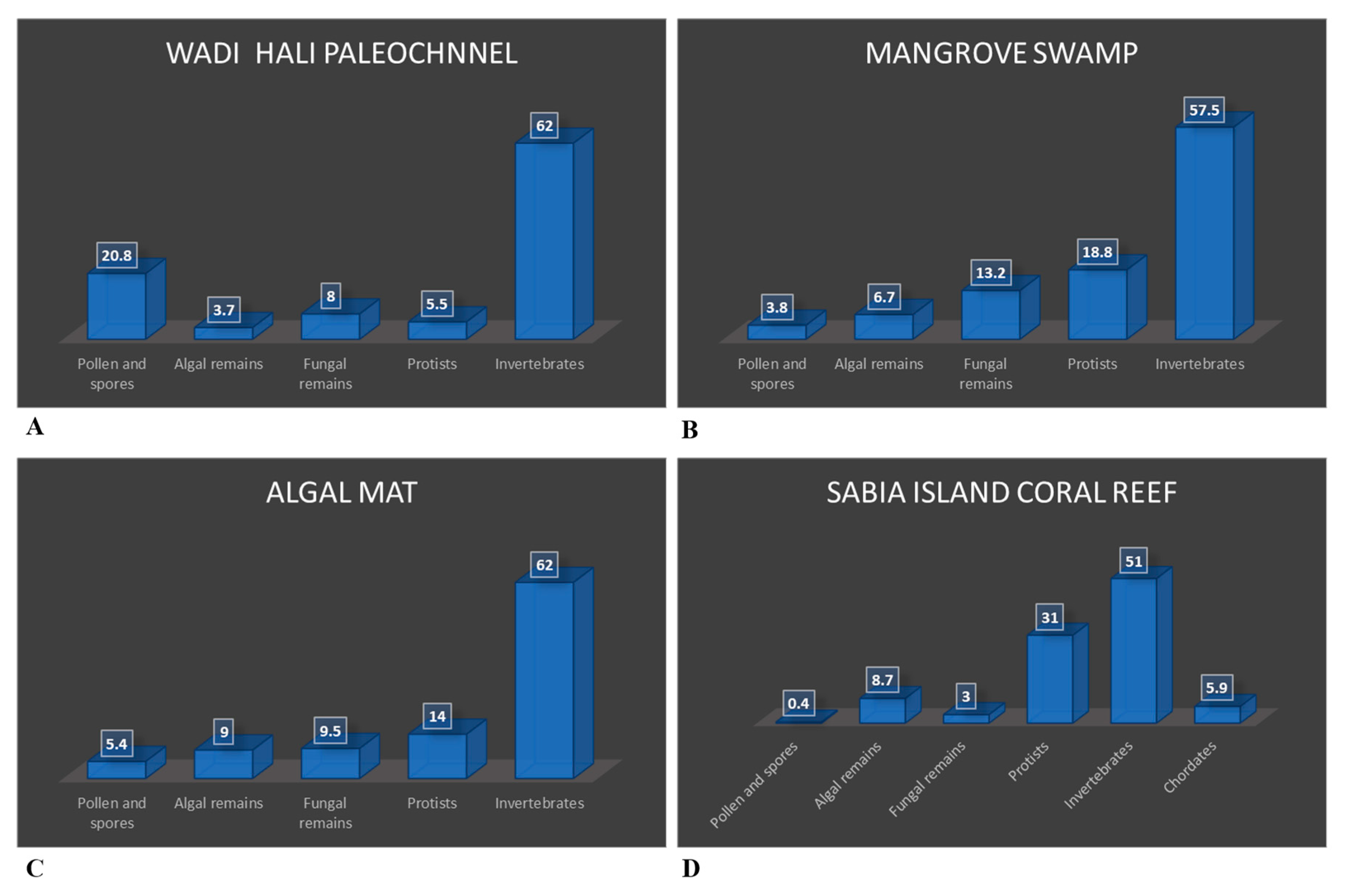

The palynomorphs recovered in this study are classified into the following groups: pollen and spores, dinoflagellate cysts and algal remains, fungal spores, hyphae and fruit bodies, protists, and invertebrates. Mineral microfossils (ascidian spicules, sponge spicules and phytoliths) are not palynomorphs because are not organic, however, since they occur in palynological preparations, they are included in the assemblage. Fragments of a variety of cuticles, tracheid, wood and charcoal occur commonly in almost all samples. Palynomorph preservation ranges from moderate to good. Several palynomorphs belonging to various groups could not be identified, thus labelled as indeterminate. The distribution of palynomorphs recorded from various environments is shown in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 (

Table 1; pollen and spores,

Table 2; dinoflagellate cysts and other algal remains,

Table 3; fungal taxa,

Table 4. microforaminifera, thecamoebians and tintinnomorphs, and form taxa,

Table 5. numerical distribution of palynomorphs and foraminiferal palynomorphs in various environments,

Table 6. invertebrate remains and mineral microfossils.

Table 7 summarizes distribution of palynomorphs and palynomorph groups in various environments. The relative abundance of palynomorphs are denoted as Rare (R): 1-4 specimens; Few (F): 5-10 specimens; Common (C ): 11-25 specimens; Very Common (VC): 26-50 specimens; Abundant (A): 51 or more specimens. The occurrences of various groups of palynomorphs and their possible source is discussed.

4.1. Pollen and Spores

Pollen and spores form a minor component of the palynomorph assemblages, only rare occurrences of individual pollen and spore were observed. A total of 25 taxa of pollen (21 angiosperms and 4 gymnosperms) and 6 taxa of spores were observed in this study (

Table 1). The pollen and spores identified were

Acacia sp. (Leguminosae),

Artemesia sp. (Asteraceae),

Avicennia marina (Avicenniaceae), cf. Cyperaceae pollen, Euphorbia sp. (Euphorbiaceae), Inaperturate pollen,

Juniperus sp. (Cupressaceae),

Nypa sp. (Arecaceae),

Palmaepollenites sp. (Arecaceae),

Palmidites sp. (Arecaceae), cf.

Potamogeton sp. (Potamogetonaceae),

Proxapertites sp. (Araceae/Arecaceae), Rannunculaceae pollen,

Rhizophora mucronata (Rhizophoraceae),

Trichotosulcites sp., and

Zea mays (Graminae; cultivated).

There is no published pollen atlas of Saudi Arabian plants. However, there are few publications on the palynology of Quaternary and Recent sediments in and around the Arabian Peninsula describing both pollen and NPP. They describe and illustrate the morphology of common recent pollen and spores [

15,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Few other publications also describe and illustrate pollen [

12,

13,

34]. These papers helped in identifying certain pollen and spores. Most importantly floral composition of various vegetation types in Saudi Arabia [

35] was used to discuss the provenance of pollen types identified. A 12-month long aerobiological survey of pollen in Riyadh, the capital city of Saudi Arabia located in the east-central region of the country, recorded several types of pollen taxa including Palmae/Arecaceae (36). In order from the most to least common taxa were Chenopodiaceae, grasses, plantain,

Artemisia, and

Ambrosia. Grasses and Chenopodiaceae released pollen 11 to 12 months of the year [

36]. This study shows the presence of airborne pollen in the central part of Saudi Arabia and most of them are reported in the present study. However, Palmae (Arecaceae) pollen dominates the coastal assemblages because mostly they inhabit the coastal regions.

Among the angiosperms, the monocotyledonous family Arecaceae (syn. Palmae) is represented by the largest number of taxa; they are

Neocouperipollis sp.,

Palmaepollenites sp.,

Palmidites sp.

Spinizonocolpites sp. (

Nypa palm),

Trichotomosulcites sp. and

Verrualetes sp. According to Thomas [

35] four palm species occur in Saudi Arabia; they are

Hyphaene thebaica, Phoenix caespitosa, Phoenix dactylifera, and

Phoenix reclinata. The date palm (

Phoenix dactylifera) is an important crop in Saudi Arabia. This family also contains commercial species such as coconuts, areca nuts and date palms, and many indoor and ornamental species as well. Presence of Arecaceae pollen taxa reported in this assemblage probably belong to these species of palms transported by wind (sand and dust storms) and water (flash floods and rains) from the neighboring regions and beyond since various species of palms occur widely in the Arabian region and northeast Africa. The genus

Proxapertites sp. (Araceae/Arecaceae) too is sourced from one of the palm species found in the region.

Acaciapollenites sp., Euphorbia sp., unidentified tricolpate pollen and Chenopodiaceae/ Amaranthaceae pollen are other significant pollen taxa of the assemblage. Most of them were derived from the vegetation of the coastal plains, sabkhas and wadis characterized by low sand dunes and saline marshes. These environments are inhabited by open, drought-deciduous thorn woodlands, mangroves, halophytes, open xeromorphic and thorn woodlands. Avicennia marina and Rhizophora mucronata are mangrove pollen found in this assemblage.

Cyperaceae pollen and pollen of Artemisia sp. and Calligonum sp. are probably derived from open xeromorphic grasslands where common shrubs of the sand-dunes are Artemisia monosperma and Calligonum comosum. All these shrubs co-occur with perennial herbs and grasses such as Cyperus conglomeratus.

Presence of a single pollen of cf. Casuarina sp. is problematic because it is not native to this area, but Casuarina trees planted near Dammam along the Arabian Gulf coast of Saudi Arabia were observed (A. Kumar, personal observation). Most likely the Casuarina pollen may have been transported during thunderstorms or dust storms which are common in this region.

The presence of cf.

Potomogeton pollen in this assemblage is problematic because it is a pond weed that occurs in submerged aquatic habitats. At present there are only rare ponds along the Tihama Plain in this desert environment where

Potomogeton could grow. Although Saudi Arabia does not have rivers or perennial streams, its seasonal streams and ponds do contain a few species. The aquatic flora in Saudi Arabia contains more than forty aquatic or semi aquatic species, of which Potamogetonaceae has the maximum number of species [

35]. Formation of ponds occurs during flooding events caused by thunderstorms in which heavy to very heavy rainfall occurs within a short period of time [

37]. I suggest that a species of

Potomogeton might have grown in one such pond contributing to the pollen assemblage.

Several plant species belonging to the family Ranunclaceae occur in Saudi Arabia as well. In the southwestern region of Saudi Arabia plant species belonging to this family are

Clematis hirsute,

Clematis simensis,

Ranunculus multifidus and

Ranunculus forskoehlii [

35]. There is a possibility that a Rannunculaceae pollen reported in this study might be sourced from one of these plants.

Among the gymnospermous pollen

Juniperus sp., Pinuspollenites sp. and

Podocarpus sp. were observed. The

Juniperus sp. pollen is related to

Juniperus procera that inhabits higher altitudes in the southwestern parts of the Arabian Peninsula.

Pinus and

Podocarpus are not known in the Arabian region. However,

Pinus and

Podocarpus pollen were reported from Pleistocene and Holocene sediments of the Nile Cone, Egypt [

14].

Pinus is a genus of the Pinaceae family; it has a characteristic bisaccate pollen. This family has worldwide distribution including North Africa.

Pinus radiata was introduced for timber production in sub-Saharan Africa and

Podocarpus is known from the tropical highlands of Africa. Tropical cyclones originating in the Arabian Sea are known to impact the Arabian Peninsula, mainly in the southern regions such as Yemen and Oman. Pollen of

Pinus and

Podocarpus are most likely wind transported from East Africa by these cyclones or the southwest monsoon, when the summer wind blows across the Arabian Sea from northeast Africa to India with a branch that veers north towards the Arabian Peninsula.

The monoporate pollen

Zea mays (Graminae; cultivated) is known from the Arabian region and have been reported in a few studies from Iraq [

32,

34,

38]. Monoporate pollen could also be derived from the family Poaceae/Gramineae which are common in the Asir Mountains, Jizan and in the wadis of southwestern regions of Saudi Arabia [

35].

Six taxa of pteridophytic spores were observed belonging to the fern families Lycopodiaceae and Polypodiaceae. In Saudi Arabia there are twenty-seven species of Pteridophytes. They occur in most terrestrial habitats and in some aquatic communities. The observed spore taxa must be related to these plants and most likely transported by both wind and water to the site of deposition. Rare specimens of Hypnaceae spore (Moss) were observed in algal mat samples. The genus Hypnum has a cosmopolitan distribution occurring on all continents except Antarctica. They are typically found in moist forest areas, while some species are aquatic. They can also be found living on soil, rocks, and live trees.

4.3. Fungal Spores, Hyphae, and Fruit Bodies

Fungal remains are a significant part of the palynomorph assemblages in most samples. Several taxa of fungal spores, fruit bodies and hyphae were observed (

Table 3). Fungal palynomorphs were tentatively identified, described, and illustrated in earlier study [

16,

17]. Later, a morphological and taxonomic restudy of these fungal palynomorphs was carried out and these morphotypes were placed in various genera and species [

52]. The generic identifications are based on comprehensive treatises on fossil fungi by Kalgutkar and Jansonius [

53], and Saxena and Tripathi [

59]. Fungal remains were represented by 23 genera and 27 named species [

52]. In addition, there are several specimens which could be identified only up to generic level and have been described as sp. 1, sp. 2, etc. The assemblage consists mainly of fungal spores whereas sporocarps are poorly represented by only three genera. The extant relationship of fungal sporocarps, spores, mycelia and other fungal remains is presented. Eight new species were proposed, they are:

Dicellaesporites bisariae,

Dicellaesporites foveolatus,

Inapertisporites choudharyi,

Inapertisporites kharei, Inapertisporites foveolatus, Inapertisporites microverrucatus, Monoporisporites rotundus and

Pluricellaesporites mishrae (

Table 3).

Several specimens of

Glomus sp. were observed in many samples [

16,

17].

Glomus sp. (family Glomeraceae) is an endomycorrhizal fungus showing a symbiotic relationship with roots of higher plants. These are globose chlamydospores, aseptate, inaperturate and are of variable size (18-138 µm). They are formed below the soil surface and are not normally transported [

54]. They are indicative of soil erosion in the catchment area and provide a useful line of evidence in palaeoecology [

55].

Fungal fruit bodies (Microthyriaceae) are multicellular, epiphyllous forms; they occur most likely on the coastal mangrove stands and are indicative of tropical to subtropical moist humid climate and heavy rainfall. Fungal hyphae are unicellular to multicellular, branched, or unbranched forms that occur primarily in freshwater marsh/flood plain environments and are indicative of high organic input and heavy rainfall. Fungal spores vary from unicellular to multi-cellular, septate or aseptate, with or without pores and occur in the present assemblages.

Since fungi lack chlorophyll, thus are heterotrophs and survive as epiphytes, saprophytes, parasites or in symbiotic associations on or in living or dead plants and animals. They rarely produce hard resistant tissues thus not prone to fossilization, however their spores, hyphae and fruit bodies are preserved as organic matter and can be isolated using palynological maceration techniques [

53]. A comprehensive account of the diverse aspects of Palaeomycology which includes study of fossil fungal palynomorphs their morphology, descriptive terminology, identification and nomenclature, geological history and paleoenvironmental and paleoclimatic significance, etc. is discussed [

53,

56]. Fungi provides evidence for relative humidity, atmospheric pressure, and precipitation rates. The assemblage of fungal spores in higher diversity and numbers are usually considered to be indicative of warm and humid climatic conditions [

47,

48].

Fossil fungal remains have been used as proxies for environmental perturbations and vegetation changes caused by climate change, as well as floristic changes, and the sequence of vegetational modifications during the past. Microclimatic and edaphic interactions of fossil fungi with geological soils have also been investigated by Kalgutkar and Jansonius [

53]. A useful review of the relationship between fungi and their environment in the geological past is provided by Stubblefield and Taylor [

57] and Taylor [

58]. Saxena and Tripathi [

59] suggested that it is advisable to take into consideration the complete palynological assemblage for paleoenvironmental interpretations rather than just based on fungal remains.

In these marginal marine environments, there is free mixing of fresh water. Many of the fungal palynomorphs were transported from land in these environments by wind and water. Conidia of Tetraploa are found generally associated with grasses indicating grass supporting environment nearby. Similarly, Alternaria spores indicate the presence of herbaceous flora. It is well known that to survive, Alternaria needs a moist warm environment. This fungus lives in seeds and seedlings and is spread by spores. Nigrospora (being represented by Exesisporites) grows in soil, air, and plants as a leaf pathogen. Microthyriaceous ascocarps, viz. Callimothallus, Spinosporonites and Trichothyrites are also epiphyllous fungi growing on leaves. In general, the assemblage indicates warm and moist conditions in the area as indicated by dry, hot, and brackish coastal environments that periodically become wet and humid due to short term excessive rainfall during tropical storms.

4.4. Protists and Invertebrates

Foraminifers, thecamoebians and tintinnids are three groups of Protists that commonly occur in these assemblages. Benthic foraminifers are quite ubiquitous in brackish/marine environments ranging from intertidal zone to deep oceans and from polar regions to the tropics. Thus microforaminiferal test linings are found in all these environments. Thecamoebians, also known as agglutinated rhizopods or testate amoebae are benthic microfaunal groups that occur worldwide in bodies of fresh and brackish water. Tintinnids are present as tintinnomorphs that are part of the microzooplankton inhabiting primarily marine, but brackish and freshwaters as well.

4.4.1. Microforaminiferal Test Linings

Microforaminiferal test linings are the inner organic remnants of the benthic microforaminifera, commonly observed in palynomorph assemblages of marine and brackish water sediments. They are acid-resistant, chitinoid linings, usually <150 μm size. Mathison and Chmura [

60] developed a qualitative classification of the physical condition of microforaminiferal test linings based on whether individual chambers were intact or damaged (split or torn), and if they were closely spaced (proximate) or the spacing of the individual chamber was open. Based on these criteria, sixteen microforaminiferal lining types were described as lining types 1 through 16 [

16,

17]. None of the specimens have any torn or split chambers in the present assemblages. Their distribution is shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5. Microforaminiferal test linings generally occur as rare or few in most samples, however, occasionally they are common to very common in few samples (

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 7).

Microforaminiferal linings have been used as proxies for water pollution, ocean productivity and paleoenvironmental studies [

61]. Monga et al. [

62] used various groups of microforaminiferal linings to delineate marine and terrestrial realms in the Paleogene sequences and facilitated better interpretation of the depositional environment. Mudie and Yanko-Holmbach [

63] carried out concurrent palynological and micropaleontological studies to investigate the relationship between the morphology and abundance of these linings and benthic foraminiferal assemblages along the transects off the Danube River Delta, NW Black Sea. Al-Dubai et al. [

64] published on the diversity and distribution of benthic foraminifera in the Al-Kharrar Lagoon, eastern Red Sea coast of Saudi Arabia. They defined five assemblages characterizing various sub-environments in the lagoon including intertidal assemblage

Quinqueloculina seminula - Q. laevigata and

Affinetrina quadrilateralis-Neorotalia calcar and a few other forms. It is not possible to relate these benthic foraminifers to the microforaminiferal linings of the present study.

A further study of microforaminiferal palynomorph assemblages was carried out to investigate palaeoenvironmental and palaeoecological utility of foraminiferal palynomorphs in absence of any foraminiferal data in marine and brackish water environments [

19]. The study demonstrated that there are significant differences in relative abundances among informally described morphotypes of foraminiferal palynomorphs in various environments. In the intertidal and mangrove environments smaller benthic calcareous foraminifers were common. However, in the coral reef environments smaller benthic, both calcareous and porcelaneous forms were observed. Common occurrence of foraminiferal palynomorphs related to small-sized opportunistic

Ammonia has palaeoecological significance due to its abundance in the mangrove sediments in proximity to roots of mangrove plant

Avicennia marina. No foraminiferal palynomorphs were observed in the algal mat environment. Thus, in absence of data on foraminiferal assemblages, relative abundances of foraminiferal palynomorph morphotypes may be used for distinguishing various coastal (brackish and marine) environments.

4.4.2. Thecamoebians

There are only two published accounts of thecamoebians from the Red Sea coast of the Arabian Peninsula [

16,

17]. Further, a report on the acid-resistant Cretaceous thecamoebian tests from the Arabian Peninsula [

65] is the only other publication on thecamoebian studies from this region. A useful illustrated key for the identification of Holocene lacustrine thecamoebian taxa [

67] is widely used for thecamoebian studies. There is an extensive review on testate rhizopod (Thecamoebian) research that discusses the several aspects of studies on thecamoebians and their usefulness in paleoenvironmental and (paleo)limnological research [

68].

Thecamoebian occurrence ranges between rare to common in these samples (

Table 4). The taxa observed were

Arcella sp.,

Centropyxis aculeata,

Centropyxis sp.,

Cyclopyxis sp.,

Difflugia sp.,

Euglepha sp.,

Geopyxella sylvicola, Thecamoebian types A, B, F, and ?Thecamoebian [

17].

Centropyxis aculeata occurs in almost every lacustrine environment; however, it prefers warmer waters above thermocline. Its morphology ranges from spiny to spineless. The occurrence of

Geopyxella sylvicola, a soil testate amoeba was reported from the tropical coastal lowlands of southwest India [

47]. Thecamoebian type A resembles

Arcella megastoma [

65] which is known from fresh-water lakes, coastal wetlands, mouth of the rivers, and the sewage drainage system in India. Thecamoebian type B resembles

Cyclopyxis sp. [

65] which is known from Nilarevu mouth of Godavari River, on the eastern coast of peninsular India [

66]. Thecamoebian type F resembles

Centropyxis laevigata.

4.4.3. Tintinnomorphs

Tintinnids are protists of complex eukaryotic organisms and are part of the microzooplankton (size ranges between 20 and 200 µm) that inhabit primarily marine, but brackish and freshwaters as well [

69]. They produce a chitinous shell, called lorica with an oral opening at the anterior end, and the posterior end may be conical, globular, or tubular. The shape of the lorica is species specific. However, there are considerable intraspecific morphological variations related to the life cycle stages of these ciliates [

70].

van Waveren [

71] introduced the term 'Tintinnomorphs' to emphasize that palynomorphs resembling tintinnids cannot always be separated into loricae or cysts and may even represent cysts of other protozoans. Da Silva et al. [

69] expanded the concept of ‘Tintinnomorphs’ for the group of palynomorphs resembling organic remains of tintinnids, which are not always identifiable as true lorica, cysts or pouch, and may even represent other structures of distinct organisms, such as rotifers and turbellarians. Many loricae and cysts occur in palynological preparations, especially in modern marine and marginal marine sediments (see references in 69) and were classified as zoomorphs [

72].

van Waveren [

71] described, illustrated, and categorized tintinnomorphs in an informal morphological system. Tintinnomorphs resemble organic remains of tintinnids, but are not necessarily identifiable as true lorica, cysts or pouch. In the present study, 34 tintinnomorphs types 1 through 34 [

16,

17] were described using the terminology of van Waveren [

71]. Later most of these morphotypes were transferred to the newly proposed form taxa [

18] except for Tintinnomorph types 9, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 16 described from the intertidal sediments (

Table 4).

There is a possibility that tintinnomorphs described here might be Neorhabdocoela oocytes [

73], because there is a morphological resemblance between them. Tintinnomorphs, as stated earlier, is a collective term for loricae, cysts and stalked pouches of Tintinnids and some of them appear morphologically like oocytes (egg capsules) of aquatic flatworms of the order Neorhabdocoela [

73]. Neorhabdocoela oocytes are typically elliptical to spherical and of dark brown color, relatively larger in size (60 - 600 µm), but tintinnomorphs in contrast are usually cup-shaped, oval and of diverse shapes, pale yellow and of relatively smaller size. Neorhabdocoela oocytes occur predominantly in fresh-water environments, however, present assemblage is reported from the intertidal environment.

A high morphological diversity of tintinnomorphs indicates high diversity of Tintinnids in the southern Red Sea zooplankton; however, their numerical presence is usually rare in the intertidal sediments. Abu Zaid and Hellal [

74] published an assemblage of modern tintinnids from the Hurghada coast of Red Sea in Egypt. However, it is difficult to assign a species or genus name to the titinnomorphs just based on the shape of lorica or cyst.

4.4.4. New Form Taxa (18)

Palynological slides of Quaternary-Recent marine and brackish water sediments invariably comprise a variety of vase-shaped palynomorphs. They are of variable sizes, could be hyaline or agglutinated and their colour ranges between yellowish to dark brown, and sometimes greyish. Biological affinities of such palynomorphs are debatable, generally palynologists relate them to tintinnid loricae and cysts, thus known as tintinnomorphs. However, similar morphotypes are known from lacustrine sediments as well and considered to be oocytes or resting eggs (6-200 µm) of Neorhabdocoela, a small, soft-bodied flatworm belonging to class Turbellaria, phylum Platyhelminthes, found in freshwater environments all over the world. Sometimes their affinity has also been related to testate amoebae. Palynological literature reports occurrences of many such palynomorphs that were described primarily based on a variety of their shapes, such as vase, urn, flask, funnel, tube, spherical and shapes that could be morphological variants among them. Identification of such forms is confusing because there is no standard nomenclature to describe them. Although attempts to informally describe them in various morphological groups were made, confusion prevails in their identifications because they do not have any formal taxonomic identity as genus and species.

Kumar (18) proposed new form genera and form species from a large morphologically diverse population of tintinnomorphs recovered from the southern Red Sea coastal environments of Saudi Arabia [

16,

17]. From these assemblages two new form genera

Katora, and

Mangrovia, and six new form species

K. arabiaca, K. elongata, K. oblonga, K. twinmorpha, M. redseaensis, and M. hallii were proposed. They occur in all the environments studied and their abundance ranges between rare to common (

Table 4).

4.4.5. Crustacean and Annelid Palynomorphs

The crustacean and annelid remain found in these palynomorph assemblages are diverse and occur in all samples; though their absolute numbers range between rare to few. A total of 17 forms including 12 crustacean and seven annelid occur in these samples (

Table 6). A neoichnological study reported several biogenic traces that occur in the intertidal and supratidal flats of the same locality as the present study [

75]. They were interpreted to have been formed by gastropods, land hermit crabs

Coenobita clypeatus, ghost crab Ocypode quadrata, insects, beetles, sand wasps, and annelid species

Arenicola marina, a large marine worm of the phylum Annelida; it is also known as lugworm or sandworm. Copepods (Subphylum Crustacea; Subclass Copepoda) inhabit the area of the present study as well. They are microcrustaceans (0.5-2 mm in size), normally occur in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat as planktic or benthic organisms. They have two pairs of antennae and a single red compound eye; are mostly crawlers, walkers, and burrowers in terrestrial environments, but still live where water is generally available [

76].

It is suggested that chitinous remains of crustaceans and annelids observed in this study should most likely belong to these invertebrate animals. At present it is not always possible to relate such palynomorphs to their parent organisms. More work needs to be done on this matter.

4.4.6. Miscellaneous and Indeterminate Palynomorphs

1. Miscellaneous palynomorphs

Miscellaneous palynomorphs include tracheid, stomata; leaf epidermis showing stomata; charcoal; and phytoliths. They are rare or few in their occurrences and do not occur in all samples (

Table 7). Leaf epidermis, probably of grass with stomata as well as phytoliths indicate the presence of family Poaceae in the region, but no Poaceae pollen was observed in these assemblages. The presence of charcoal indicates either natural forest fires or possibly wood burning due to human activity.

2. Indeterminate palynomorphs

A total of seven indeterminate forms were identified and informally named as A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. Most of these indeterminate palynomorphs occur rarely in the samples (

Table 7). A tentative suggestion about their affinity is given wherever possible, within brackets. They are Indeterminate form A (may be worm oocytes with operculum); indeterminate form B (Algal spore?); indeterminate form C (Cyanobacteria?); indeterminate form D (Pseudoschizaea/Concentricystis sp.?); indeterminate form E (Crustacean egg?); indeterminate form F (Algal cyst?) and indeterminate form G (Fungal sporangium?).

4.4.7. Ascidian and Sponge Spicules

Ascidian spicules are mineral microfossils (calcareous) thus cannot be considered as palynomorphs. However, they occur in palynological slides along with other palynomorphs. Ascidians (Phylum Chordata, Class Ascidiacea), also known as sea squirts, are sac-like marine invertebrate filter feeders characterized by a tough outer "tunic" made of the polysaccharide cellulose. They are sessile animals that remain attached to their substratum, such as rocks and shells. They are found in all marine habitats from shallow water to the deep sea. Ascidians generate calcareous spicules (usually between 15 µm and 100 µm ) of characteristic shapes that accumulate in their tunic or internal tissues. Spicule morphology is quite diverse, thus is significant in ascidian taxonomy [

77,

78]. A brief overview of the fossil record of ascidian spicules is provided [

79,

80].

The present assemblage contains forms that range in size between 26 µm and 38 µm. This size range compares well with the forms described from Quaternary piston core of muddy sediments deposited by turbidity currents from offshore Argentina [

80] where average size ranges between 25 µm and 30 µm. The ascidian spicules described from Argentina are from shallow marine environments that were transported to deeper marine environments by turbidity currents.

Numbers of ascidian spicules in the present assemblage range between rare to few (

Table 6). They are not identifiable with published forms; informal names were used to describe them [

17]. Ascidian spicules were observed only in the Sabia Island coral reef assemblage. They were informally described using the terminology of Lukowiak [

79] and Lukowiak et al. [

81]. Ascidian spicule types 1 through 5 belong to the Didemnidae Family and the ascidian spicule type 6 belongs to the Polycitoridae Family [

77].

Ascidian spicules type 1 has close morphological resemblance with

Didemnum-like spicule A described from Miocene of Moldova [

81]. However, the Moldovian specimens are significantly larger; their size ranges between 90 µm to 100 µm and has only 10 rays. Ascidian spicules type 2 has close morphological resemblance with

Trididemnum-like spicule B described from Miocene of Moldova [

81]. However, the Moldovian specimens are significantly larger; their size is 100 µm and has only 8 to10 rays. Ascidian spicules type 3 resembles

Didemnid spicule type II described from Eocene of Australia [

79]. However, the Australian specimens are larger measuring 60 µm. Ascidian spicules type 4 resembles

Didemnid spicule type III described from Eocene of Australia [

79]. However, the Australian specimens are larger measuring 100 µm. Ascidian spicules type 5 is triangular, Y-shaped form, with three long, slender, and conical rays with pointed ends. Length of each ray varies between 76-36 µm and maximum width at the center is 23.6 µm. Surface of rays is smooth. Ascidian spicules type 6 resembles

Cystodytes cf.

dellechiajei described [

79] from Eocene of Australia. However, the Australian specimens are 100-120 µm in diameter with a smooth central part. The present specimen is significantly smaller and has a granular internal surface.

One specimen of sponge spicule was observed in sample SI2.

4.4.8. Polychaete Chaetae

Rare specimens of setae of polychaetes were observed in the Sabia Island coral reef assemblage. chaeta (also spelled cheta or seta; plural chaetae) is a chitinous bristle found in insects, arthropods, and annelid worms. The Polychaeta or the bristle worms are generally marine annelid worms having a segmented body. Each segment has a pair of fleshy protrusions called parapodia that bear chitinous bristles called chaetae. Common Polychaetes are lugworm (

Arenicola marina) and sand worm that were reported from this area in a neoichnological study by the author [

75]. Chaetae shape and size vary considerably and are often species-specific; main types include capillary, compound, pseudo compound, hooked and many more [

82].