Introduction

Designing, developing, deploying, operating, and managing the lifecycle of distributed software applications is a critical area of study because all our business and personal lives depend on them. Volumes have been written on the subject and the book authority organization lists 20 best distributed system books of all time [

1]. A literature survey on service-oriented architecture used 65 papers published between 2005 and 2020. [

2]. A systemic literature review of microservice architecture (MSA), (MSA is a more recent proposal to use fine-grained services architecture for distributed software systems) discovered in 3842 papers [

3]. However, several issues with their design, deployment, operation, and management, their instability under large fluctuations in resource demand or availability, vulnerability to security breaches, and CAP theorem limitations are ever-present. The CAP theorem [

4], also known as Brewer’s theorem states that it is impossible for a distributed data system to simultaneously provide more than two out of three guarantees:

Consistency: All users see the same data at the same time, no matter which node they connect to. For this to happen, whenever data is written to one node, it must be instantly forwarded or replicated to all the other nodes in the system before the write is deemed ‘successful’.

Availability: Any client requesting data gets a response, even if one or more nodes are down. Another way to state this is that all working nodes in the distributed system return a valid response for any request, without exception.

Partition Tolerance: The system continues to operate despite an arbitrary number of messages being dropped (or delayed) by the network between nodes.

In addition, the complexity of maintaining availability and performance continues to increase with Hobson’s choice between single vendor-lock-in or multi-vendor complexity [

5]. There are solutions available using free and open-source software or adopting multi-vendor and heterogeneous resources offered by multiple cloud providers [

6]. This can help to maintain the scalability and management flexibility of distributed applications. However, this often increases complexity, and layers of management lead to the “who manages the managers” conundrum. Moreover, the advent of many virtualized and disaggregated technologies, and the rapid increase of the Internet of Things (IoT) makes end-to-end orchestration difficult to do at scale.

Some arguments suggest that the problems of scalability, resiliency, and complexity of distributed software applications are symptoms that point to a foundational shortcoming of the computational model associated with the stored program implementation of the Turing Machine from which all current-generation computers are derived [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

As Cockshott et al., [

11] p. 215 describe in their book “Computation and its Limits” the concept of the universal Turing machine has allowed us to create general-purpose computers and “use them to deterministically model any physical system, of which they are not themselves a part to an arbitrary degree of accuracy. Their logical limits arise when we try to get them to model a part of the world that includes themselves.” External agents are required for the harmonious integration of the computer and the computed.

The distributed software application consists of a network structure of distributed software components that are dependent on the infrastructure that provides the resources (CPU, memory, and power/energy) which are managed by different service providers with their own infrastructure as a service (IaaS), and Platform as a service (PaaS) management systems. In essence, the process of execution structures behaves like a complex adaptive system and is prone to emergence properties when faced with local fluctuations impacting the infrastructure. For example, if a failure occurs in any one component, the execution halts and external entities must fix the problem. If the demand fluctuates, resources must be increased or decreased to maintain efficiency and performance by an external entity. These lead to a single vendor lock-in or the complexity of a third-party orchestrator that manages various component managers.

Current-generation computers are used for process automation, intelligent decision-making, mimicking behaviors by robots, and using transformers to generate text, images, and videos [

14,

15,

16].

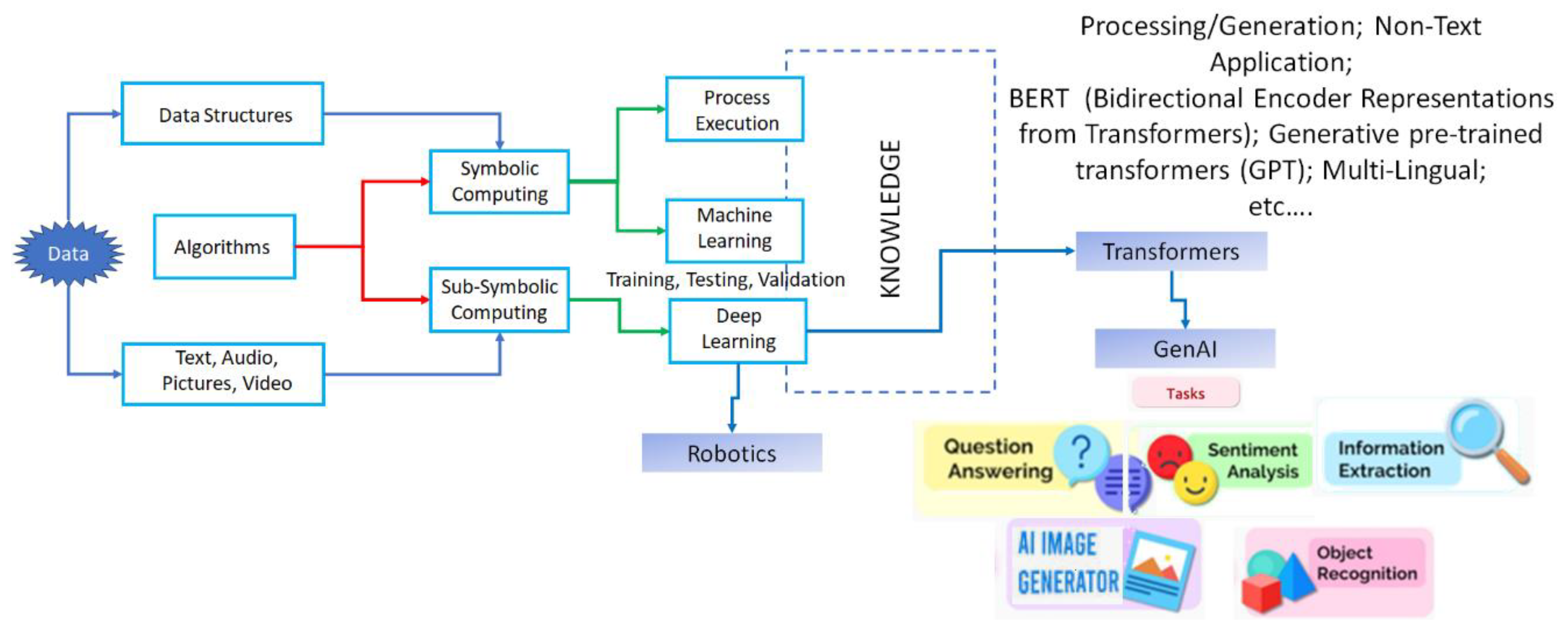

Figure 1, shows process automation executed by an algorithm operating on data structures. Insights obtained through machine learning algorithms or deep learning algorithms for intelligent decision-making are derived from data analytics also shown in

Figure 1. In addition, deep learning algorithms (which use multi-layered neural networks to simulate the complex pattern recognition processes of the human brain) are used to perform robotic behaviors or generative AI tasks.

McCulloch and Pitts’s 1943 paper [

17] on how neurons might work, and Frank Rosenblatt’s introduction of the perceptron [

18] led to the current AI revolution with deep learning algorithms using computers.

Robotic Behavior Learning primarily involves training a robot to perform specific tasks or actions. This includes reinforcement learning, where the robot learns from trial and error, receiving rewards for successful actions and penalties for mistakes. Over time, the robot improves its performance by maximizing its rewards and minimizing penalties. This type of learning is useful in environments where explicit programming of all possible scenarios is impractical. On the other hand, transformers in GenAI focus on processing and generating text data. They use attention mechanisms to understand the context within large bodies of text. The input to a Transformer model is a sequence of tokens (words, sub-words, or characters), and the output is typically a sequence of tokens that forms a coherent and contextually relevant text. This could be a continuation of the input text, a translation into another language, or an answer to a question. In addition, when the algorithm is trained on a large dataset of images or videos, it learns to understand the underlying patterns and structures in the data and generates new, original content. The results can be surprisingly creative and realistic, opening up new possibilities for art, design, and visual storytelling.

Symbolic computing uses a sequence of symbols (representing algorithms) that operate on another sequence of symbols (representing data structures describing the state of a system that depicts various entities and relationships) to change the state. Sub-symbolic computation is associated with neural networks where an algorithm mimics the neurons in biological systems (perceptron). A multi-layer network using perceptron mimics the neural networks in converting the information provided as input (text, voice, video, etc.).

Several issues with sub-symbolic computing have been identified [

19,

20,

21]:

Lack of Interpretability: Deep learning models, particularly neural networks, are often “black boxes” because it’s difficult to understand the reasoning behind how they respond to the queries.

Need for Large Amounts of Data: These models typically require large data sets to train effectively.

Overfitting: Deep learning models can overfit the training data, meaning they may not generalize well to unseen data.

Vanishing and Exploding Gradient Problems: These are issues that can arise during the training process, making it difficult for the model to learn.

Adversarial Attacks: Deep learning models are vulnerable to adversarial attacks, where small, intentionally designed changes to the input can cause the model to make incorrect predictions.

Difficulty Incorporating Symbolic Knowledge: Sub-symbolic methods, such as neural networks, often struggle to incorporate symbolic knowledge, such as causal relationships and practitioners’ knowledge.

Bias: These methods can learn and reflect biases present in the training data.

Lack of Coordination with Symbolic Systems: While sub-symbolic and symbolic systems can operate independently, they often need to coordinate closely together to integrate the knowledge derived from them, which can be challenging.

Recent advances based on the General Theory of Information, provide a new approach that integrates symbolic and sub-symbolic computing structures with a novel super-symbolic structure and addresses various foundational shortcomings mentioned above [

9,

22,

35,

37].

Mark Burgin’s General Theory of Information (GTI) bridges our understanding of the material world, which consists of matter and energy, and the mental worlds of biological systems that utilize information and knowledge. This theory is significant because it offers a model for how operational knowledge is represented and used by biological systems involved in building, operating, and managing life processes [

9,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. In addition, it suggests a way to represent operational knowledge and use it to build, deploy, and operate distributed software applications. The result is a new class of digital automata with autopoietic and cognitive behaviors that biological systems exhibit [

23]. Autopoietic behavior refers to the self-producing and self-maintaining nature of living systems. Cognitive behavior refers to obtaining and using knowledge.

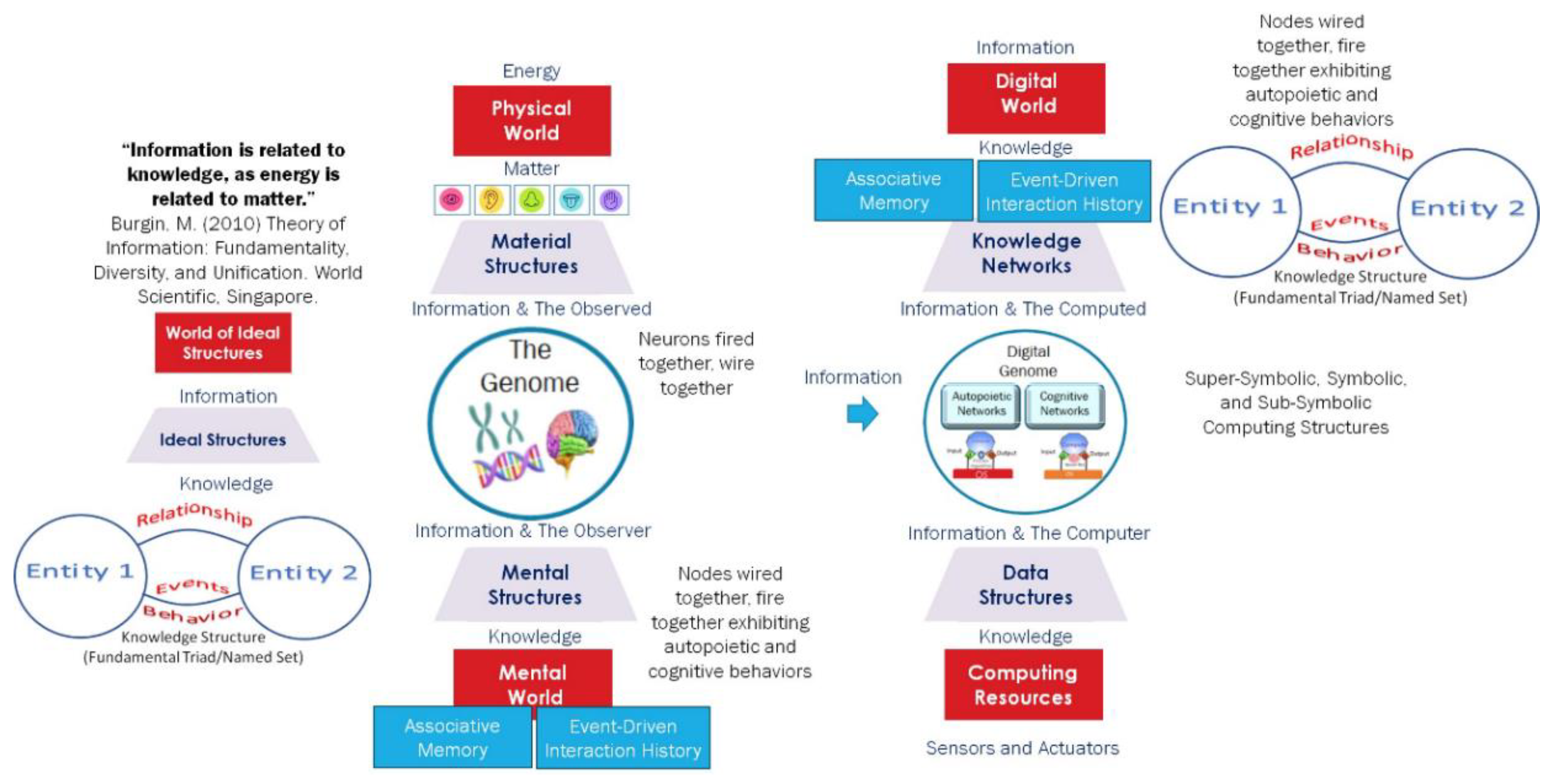

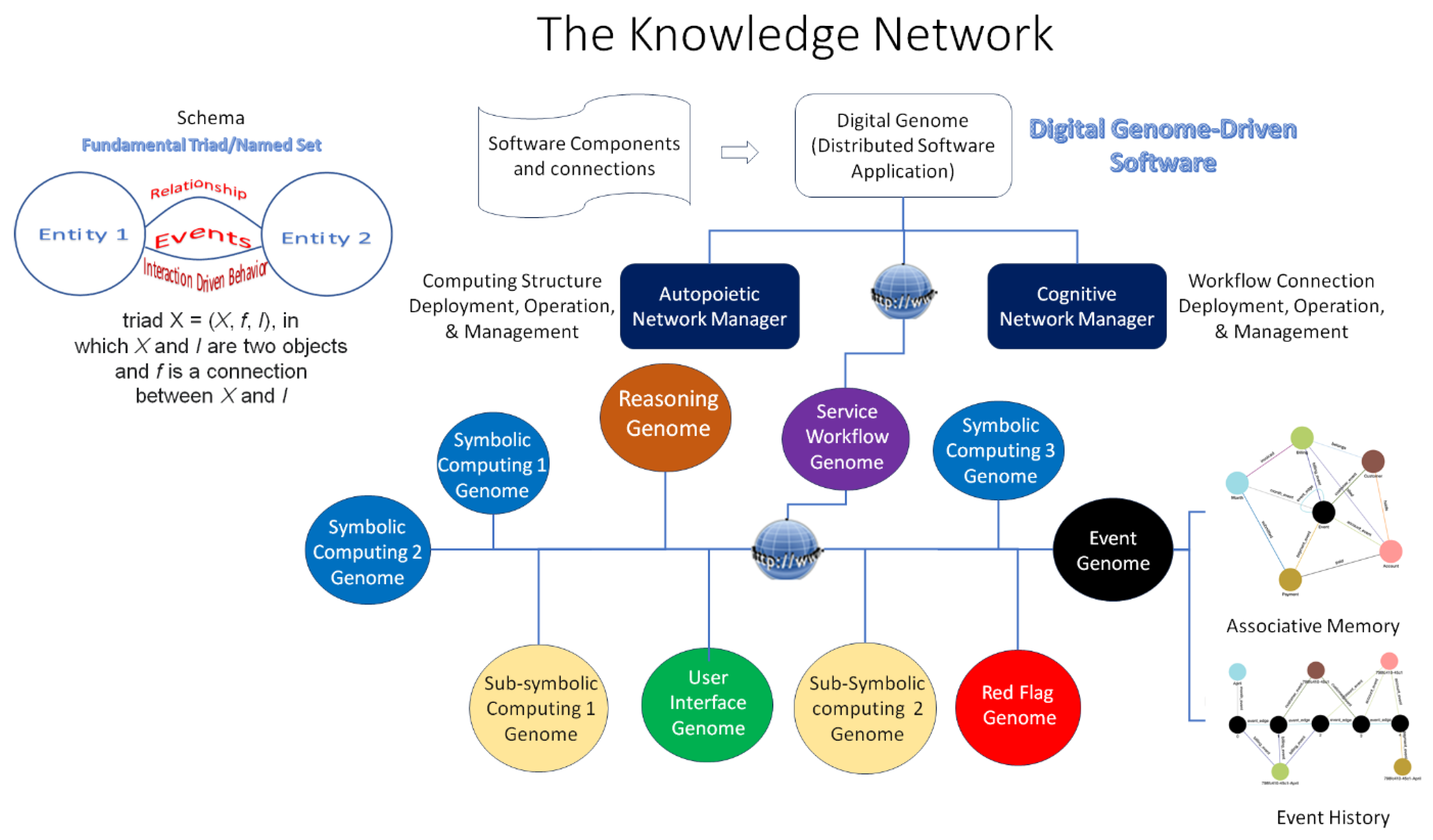

Figure 2 depicts [

37] how information bridges the material world of structures formed through energy and matter transformations; the mental world that observes the material world and creates mental structures that represent the knowledge received from observed information; the digital world created through the mental structures using the stored program control implementation of the Turing Machine.

GTI bridges our understanding of the material world, which consists of matter and energy, with the mental world of biological systems, that utilize information and knowledge to interact with the material world. The genome through natural selection has evolved to capture and transmit the knowledge to build, operate, and manage a structure that receives information from the material world and converts it into knowledge in the mental world using the genes and neurons. The result is an associative memory and event-driven transaction history that the system uses to interact with the material world. In the symbolic computing structures, the knowledge is represented as data structures (entities and their relationships) depicting the system state, and its evolution using an algorithm. In sub-symbolic computing, the algorithm creates a neural network and knowledge is represented by the optimized parameters that result from training the neural network with data structures. The observations of Turing, Neumann, McCulloch, Pitts, and Rosenblatt have led to the creation of the digital world where information is converted into knowledge in the digital form as shown in

Figure 1. The super-symbolic structure derived from GTI provides a higher-level knowledge representation in the form of fundamental triads/named sets [

22,

24,

28] shown in

Figure 2.

In essence, three contributions from GTI enable the developing, deploying, operating, and managing of a distributed application using heterogeneous IaaS and PaaS resources while overcoming the shortcomings discussed in this paper:

Digital Automata: Burgin’s construction of a new class of digital automata to overcome the barrier posed by the Church–Turing Thesis has significant implications for AI. This allows for the creation of more advanced AI systems that can perform tasks beyond the capabilities of traditional Turing machines [

23,

24,

25,

26].

Super-symbolic Computing: His contribution to super-symbolic computing with knowledge structures, cognizing oracles, and structural machines changes how we design and develop self-regulating distributed applications. These tools also allow AI systems to process and understand information in a more complex and nuanced way, similar to how humans do by interacting with the sub-symbolic and super-symbolic computing structures with common knowledge representation using super-symbolic computing which is different from neuro-symbolic computing [

36,

37,

38].

Digital Genome: The schema and associated operations derived from GTI are used to model a digital genome specifying the operational knowledge of algorithms executing the software life processes. The digital genome specifies operational knowledge that defines and executes domain-specific functional requirements, non-functional requirements, and best-practice policies that maintain the system behavior, conforming to the expectations of the design. This results in a digital software system with a super-symbolic computing structure exhibiting autopoietic and cognitive behaviors that biological systems also exhibit [

37,

38,

39].

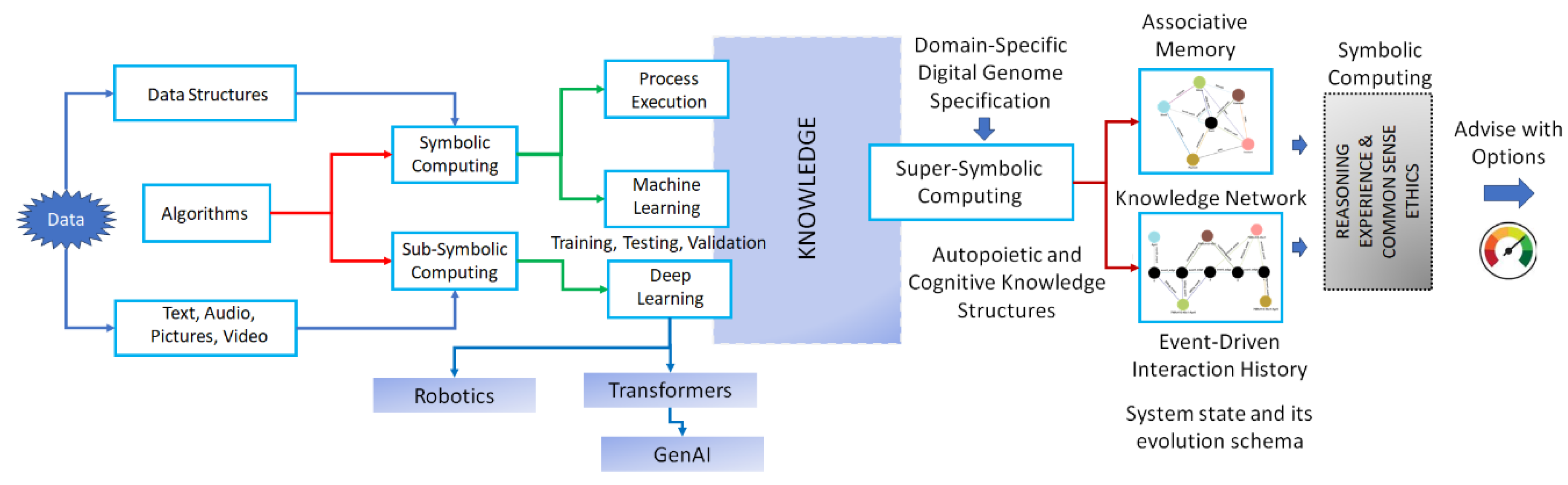

Figure 3 shows the super-symbolic computing structure implementing a domain-specific digital genome using the structural machines, cognizing oracles, and knowledge structures derived from GTI to create a knowledge network with two important features:

The knowledge network captures the system state and its evolution caused by the event-driven interactions of various entities interacting with each other in the form of associative memory and event-driven interaction history. It is important to emphasize that the Digital Genome and super-symbolic computing structure are different from symbolic and sub-symbolic computing structures used together. For example, the new frameworks [

39] from MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory provide important context for language models that perform coding, AI planning, and robotic tasks. However, this approach does not use associative memory and event-driven transaction history as long-term memory. The digital genome provides a schema for creating them.

GTI provides a schema and operations [

34] for representing the system state and its evolution, which are used to define and execute various processes that fulfill the functional and non-functional requirements and the best-practice policies and constraints.

The figure shows the theoretical GTI-based implementation model of the digital genome specifying the functional and non-functional requirements along with adaptable policies based on experience to maintain the expected behaviors based on the genome specification. In this paper, we describe an implementation of a distributed software application using the digital genome specification and demonstrate the policy-based management of functional and non-functional requirements. In section 2, we describe the distributed software application and its implementation. In section 3, we discuss the results and lessons learned. In section 4, we draw some conclusions and discuss some future directions.

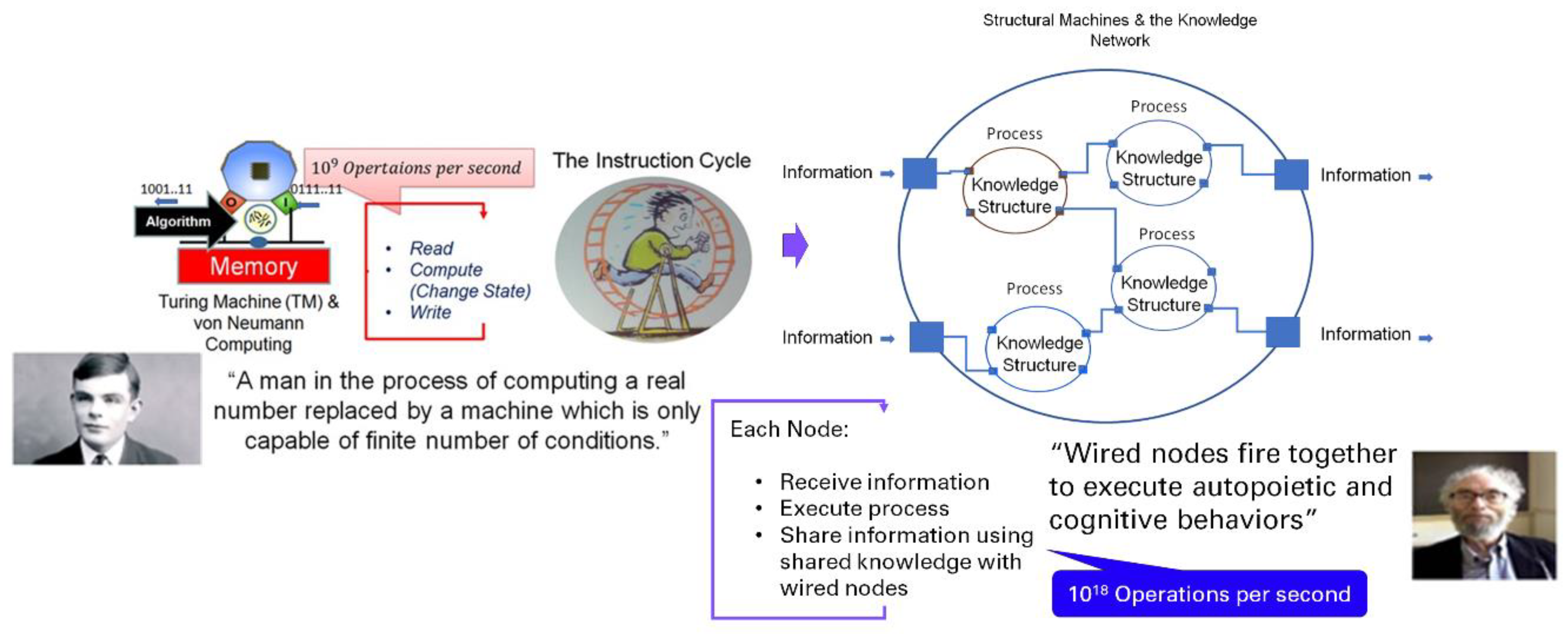

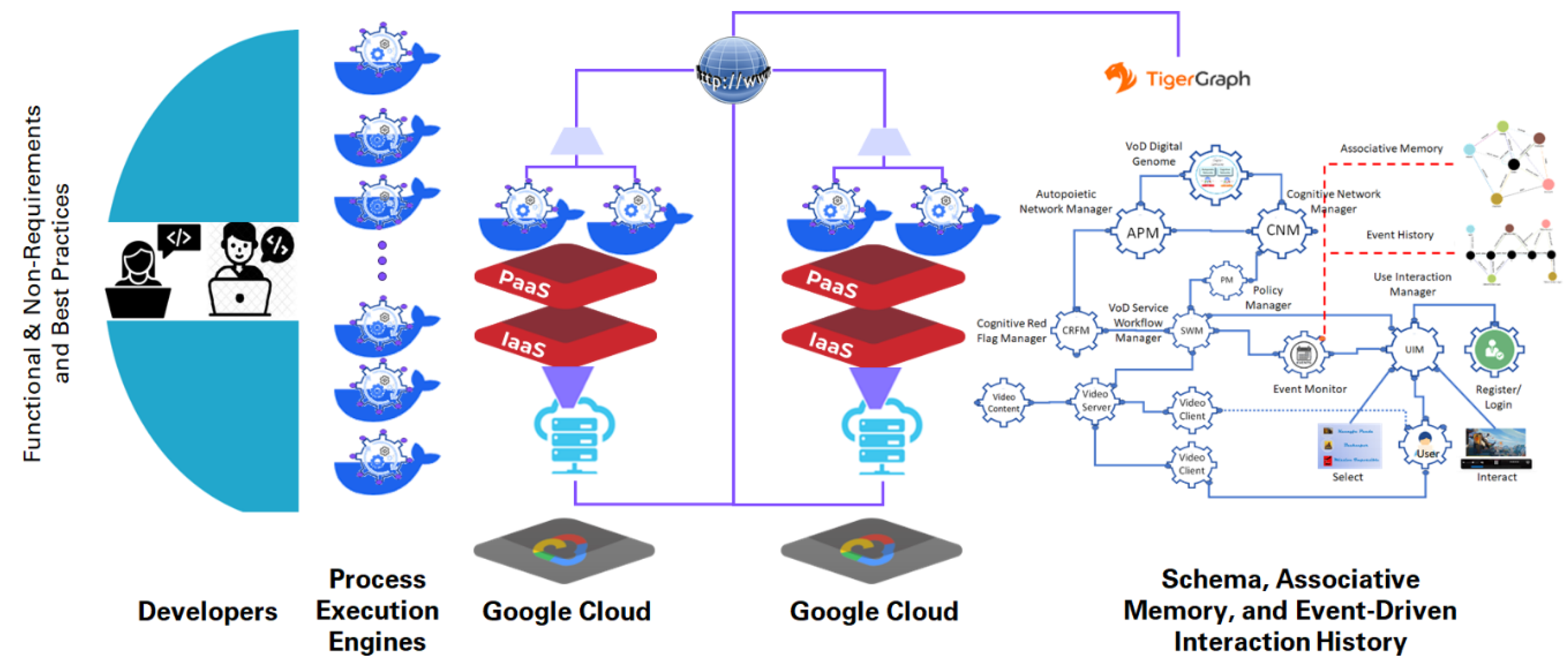

Figure 4 shows the two information processing structures one based on the Turing Machine and von Neumann architecture and the other based on the structural machines and the knowledge network composed of knowledge structures and cognizing oracles.

Whether symbolic, sub-symbolic, or neuro-symbolic, the current state of the art uses the von- Neumann implementation of the Turing Machine. The approach presented in this paper uses structural machines with a schema and operations defining a knowledge network based on GTI.

Figure 4 shows the two models. Each knowledge structure executes a process specified by the functional and non-functional requirements using best-practice policies and constraints to fulfill the design goals. We describe in the next section the knowledge network and how to use it to design, deploy, operate, and manage a distributed software application.

Distributed Software Application and Its Implementation

A distributed software application is designed to operate on multiple computers or devices across a network. They spread their functionality across different components with a specific role, work together, and communicate using shared knowledge to accomplish the application’s overall goals. The overall functionality and operation are defined using functional and non-functional requirements, and policies and constraints are specified using best practices that ensure the application’s functionality, availability, scalability, performance, and security while executing its mission. We describe a process to design, develop, deploy, operate, and manage a distributed software application using functional and non-functional requirements, policies, and constraints specified to achieve a specific goal. The goal is determined by the domain knowledge representing various entities, their relationships, and the behaviors that result from their interactions.

Both symbolic and sub-symbolic computing structures execute processes that receive input, fulfill functional requirements, and share knowledge with other wired components to fulfill system-level functional requirements.

Figure 5 shows the computing models and how knowledge is represented and used in the new approach based on GTI.

Figure 5 describes how the associative memory and the event-driven interaction history of various entities, their relationships, and behaviors are specified using a schema [

30,

33,

34].

As discussed in [34] p. 13 “Information processing in triadic structural (entities, relationships, and behaviors) machines is accomplished through operations on knowledge structures, which are graphs representing nodes, links, and their behaviors. Knowledge structures contain named sets and their evolution containing named entities/objects, named attributes, and their relationships. Ontology-based models of domain knowledge structures contain information about known knowns, known unknowns, and processes for dealing with unknown unknowns through verification and consensus. Inter-object and intra-object behaviors are encapsulated as named sets and their chains. Events and associated behaviors are defined as algorithmic workflows, which determine the system’s state evolution.

A named set chain of knowledge structures (knowledge network) provides a genealogy representing the system’s state history. This genealogy can be treated as the deep memory and used for reasoning about the system’s behavior, as well as for its modification and optimization.”

The domain knowledge for each node and the knowledge network is obtained from different sources (including the Large Language Models) and specified as functional and non-functional requirements derived from the system’s desired availability, performance, security, and stability.

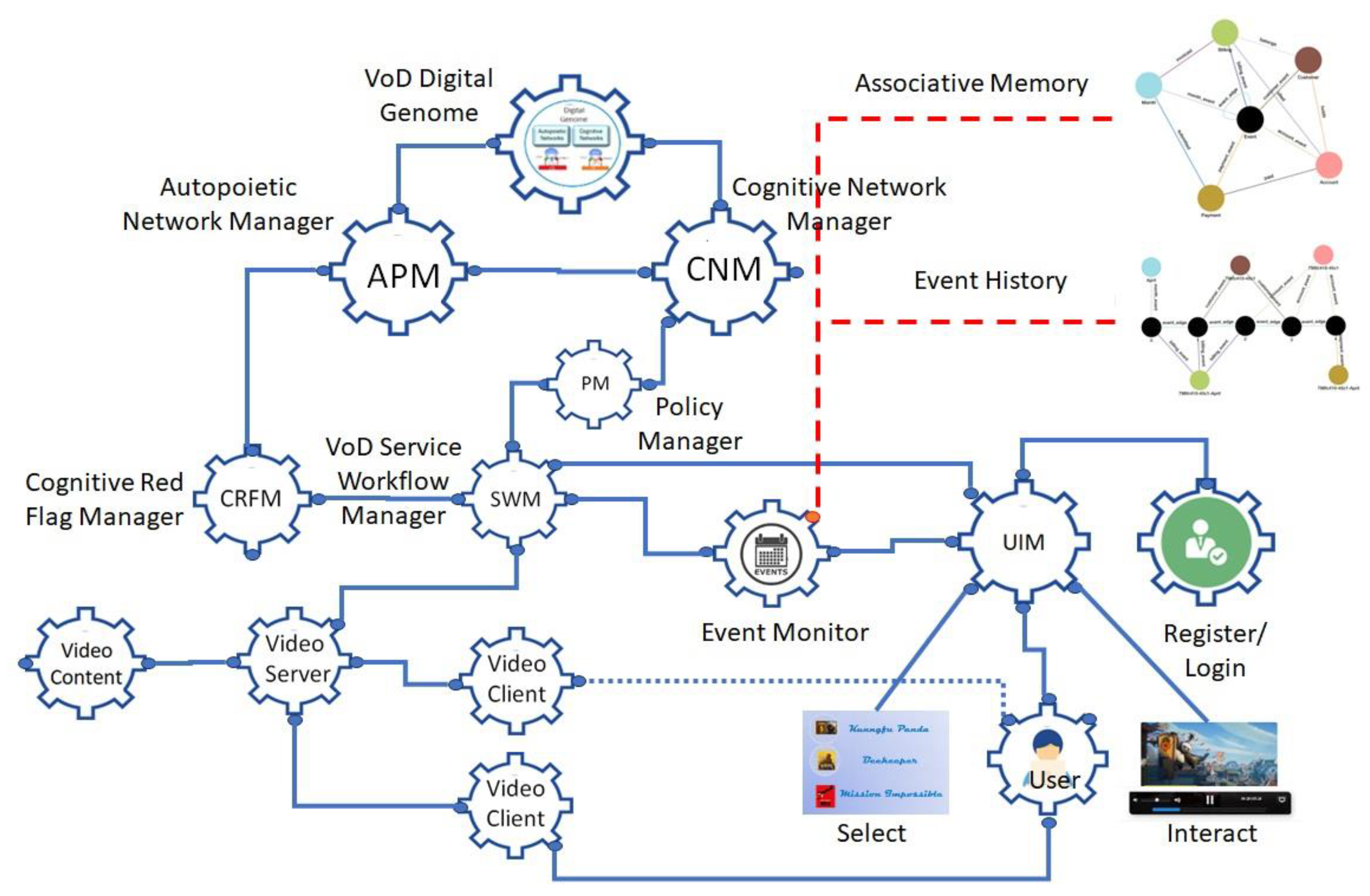

The digital genome specifies the functionality and operation of the system that deploys, operates, and manages the evolution of the knowledge network with the knowledge about where to get the computing resources and use them. The autopoietic network manager is designed to deploy the software components with appropriate computing resources (e.g., IaaS and PaaS in a cloud) as services. The cognitive network manager manages the communication connections between the nodes executing various processes. The service workflow manager controls the workflow among the nodes delivering the service. An event monitor captures the events in the system to create the associative memory and the event-driven interaction history. A cognitive red flag manager captures deviations from the normal workflow and alerts the autopoietic manager which takes corrective action by coordinating with the cognitive network manager. The architecture provides a self-regulating distributed software application using resources from different providers.

We describe an example implemented using this architecture to demonstrate the feasibility and the benefits of this architecture. A video-on-demand service is deployed in a cloud with auto-failover. The purpose of this demonstration is to show the feasibility of creating associative memory and event-driven transaction history that provides real-time evolution of the system as long-term memory. They can be used to perform data analytics using a transparent model to gain insights in contrast to the current state of the art as shown in

Figure 3.

Video on Demand (VoD) Service with Associative Memory and Event-Driven Interaction History

The design begins with defining the functional requirements, non-functional requirements, best-practice policies, and constraints.

Functional Requirements for User Interaction:

User is given a service URL

User registers for the service

Administrator authenticates with a user ID and password

User logs into URL with user ID and Password

The user is presented with a menu of videos

User Selects a video

The user is presented with a video and controls to interact

User uses the controls (pause, start, rewind, fast forward) and watches the video.

Functional Requirements for Video Service Delivery:

-

Video Service consists of several components working together:

- ○

VoD service workflow manager

- ○

Video content manager

- ○

Video server

- ○

Video client

Non-functional Requirements, Policies, and Constraints:

Auto-Failover: When a video service is interrupted by the failure of any component, the user service should not experience any service interruption.

Auto-Scaling: When the end-to-end service response time falls below a threshold, necessary resource adjustments should be made to adjust the response time to the desired value.

Live Migration: Any component should be easily migrated from one infrastructure to another without service interruption.

Figure 6 shows a digital genome-based architecture with various components that fulfill these requirements. Each node is a process-executing engine that receives input and executes the process using a symbolic or sub-symbolic computing structure. An example is a Docker container deployed in a cloud using local IaaS and PaaS. The roles of the digital genome, the autopoietic network manager, and the cognitive network manager are well discussed in several papers [

9,

21,

37,

40].

Just as the genome in living organisms contains the information required to manage life processes the digital genome contains all the information about the distributed software application in the form of knowledge structures to build itself, reproduce itself, and maintain its structural stability while using its cognitive processes to fulfill the functional requirements.

We summarize the functions of the schema of the knowledge network that specifies the process of processes executing the system’s functional and non-functional requirements and best practice policies and constraints:

The Digital Genome Node: It is the master controller that provides the operational knowledge to deploy the knowledge network that contains various nodes executing different processes and communicating with other nodes wired together with shared knowledge. It initiates the autopoietic and cognitive network managers responsible for managing the structure and workflow fulfilling the functional and non-functional requirements.

Autopoietic Network Manager (APM) Node: It contains knowledge about where to deploy the nodes using resources from various sources such as IaaS and PaaS from cloud providers. It receives a list of Docker containers to be deployed as nodes and determines how they are wired together. At t=0, APM deploys various containers using the desired cloud resources. It passes on the URLs of these nodes and the network connections to the Cognitive Network Manager. For example, if the nodes are duplicated to fulfill non-functional requirements, it assigns which connection is the primary and which is the secondary.

Using the URLs and their wiring map, the CNM consults with the Policy Manager which specifies the requirements for fulfilling the non-functional requirements such as auto-failover, auto-scaling, and live migration, then sets up the connection list and passes it on to the Service Workflow Manager.

Service Workflow Manager (SWM): Provides the service workflow control by managing the connections between various nodes participating in the service workflow. In the VoD service, it manages the workflow of the video service subnetwork and the user interface manager subnetwork as shown in

Figure 5. It also manages the deviations from the expected workflow by using the policies that define actions to correct them.

User Interface Management Subnetwork (UIM): It manages the user interface workflow providing registration, login, video selection, and other interactions.

Video Service Management Subnetwork: It provides the video service from content to video server and client management.

Cognitive Red Flag Manager: when deviations occur from normal workflow such as one of the video clients fails, the SWM will switch it to the secondary video client as shown in

Figure 6. It also communicates a red flag which is then communicated to the APM to take corrective action, in this case, restore the video client that went down and let the CNM know to make it secondary.

Event Monitor: It monitors events from video service and user interface workflows and creates an associative memory and an event-driven interaction history with a time stamp. These provide the long-term memory for other nodes to use the information in multiple ways including performing data analytics and gaining insights to take appropriate action.

In the next section, we discuss the results.