Submitted:

21 June 2024

Posted:

24 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Eddy Identification

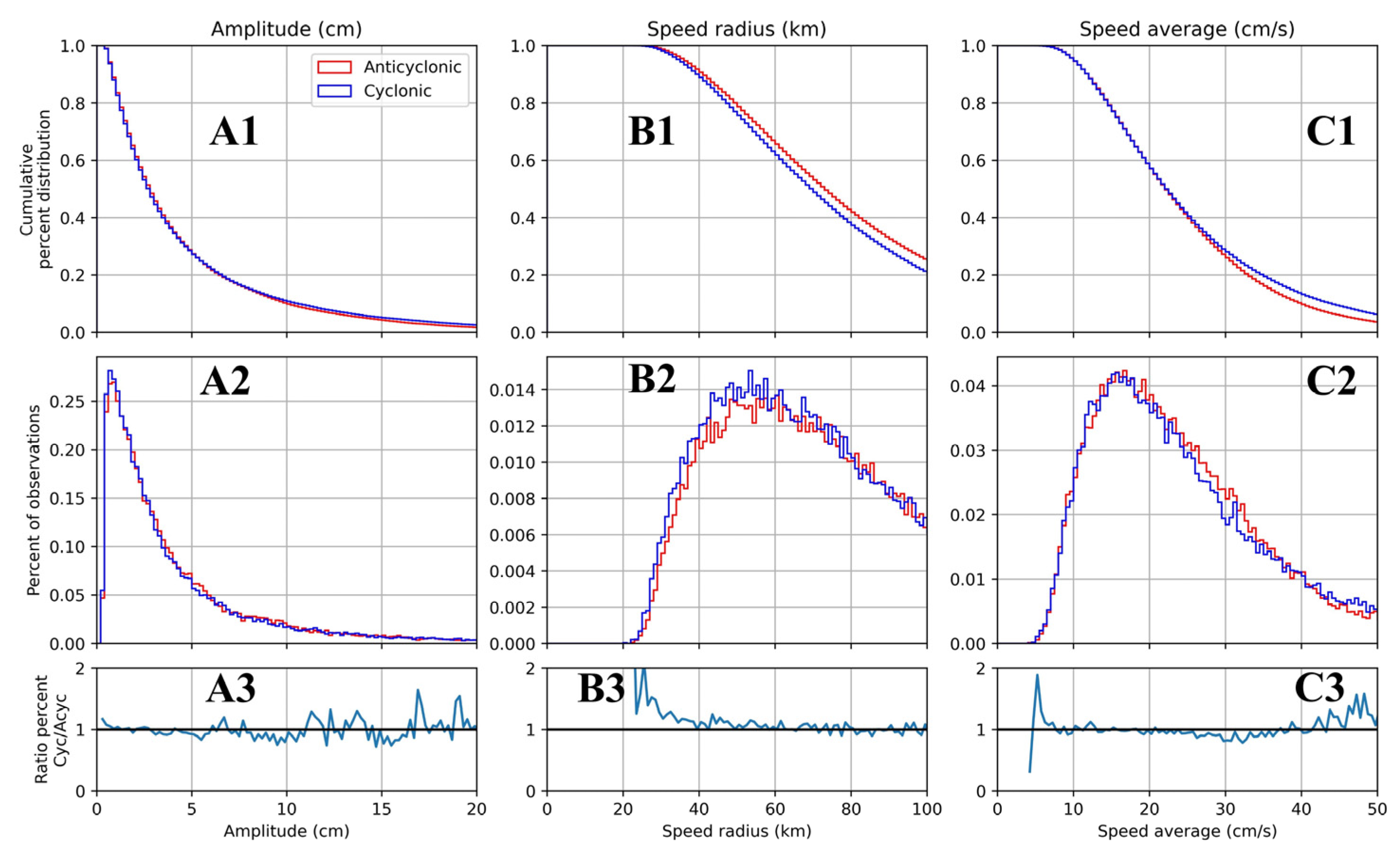

3. Results and Discussion

3.1.1. Mesoscale Eddy Life Span, Frequency, and Track Analysis

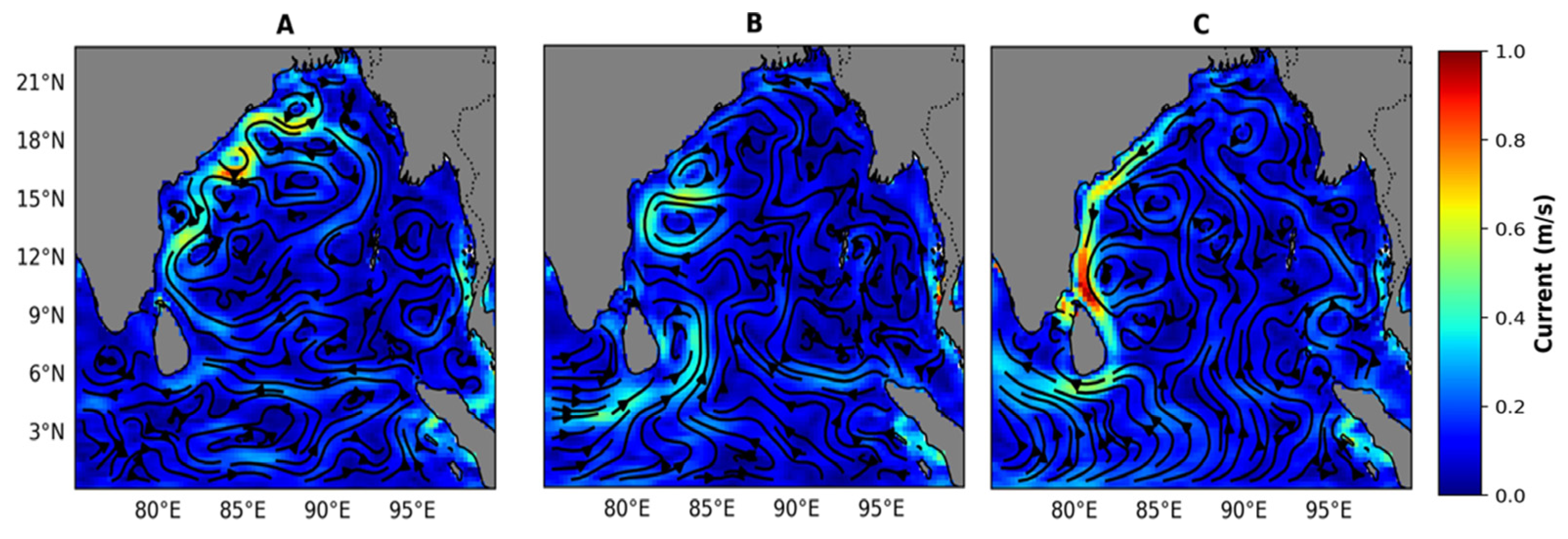

3.1.2. Mesoscale Eddy Propagation Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robinson, I.S. Mesoscale Ocean Features: Eddies. In Discovering the Ocean from Space; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010; pp. 69–114; ISBN 978-3-540-24430-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, S.K.; Luther, M.E.; O’Brien, J.J. Relationship between the Interannual Variability of Ocean Fields and the Wind Stress Curl over the Central Arabian Sea and the Indian Summer Monsoon Rainfall (Unpublished). 1986.

- Gopalan, A.K.S.; Krishna, V.V.; Ali, M.M.; Sharma, R. Detection of Bay of Bengal Eddies from TOPEX and in Situ Observations. Journal of Marine Research 2000, 58, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Curchitser, E.N. Gulf Stream Eddy Characteristics in a High-resolution Ocean Model. JGR Oceans 2013, 118, 4474–4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busireddy, N.K.R.; Ankur, K.; Osuri, K.K. Significance of Mesoscale Warm Core Eddy on Marine and Coastal Environment of the Bay of Bengal. In Coastal and Marine Environments-Physical Processes and Numerical Modelling; IntechOpen, 2019.

- Chelton, D.B.; Schlax, M.G.; Samelson, R.M.; Szoeke, R.A. de Global Observations of Large Oceanic Eddies. Geophysical Research Letters 2007, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Godø, O.R.; Samuelsen, A.; Macaulay, G.J.; Patel, R.; Hjøllo, S.S.; Horne, J.; Kaartvedt, S.; Johannessen, J.A. Mesoscale Eddies Are Oases for Higher Trophic Marine Life. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, T.G. Annual and Seasonal Mean Buoyancy Fluxes for the Tropical Indian Ocean. Current Science 1997, 667–674. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, V. Sediment Load of Indian Rivers. Current Science 1993, 928–930. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; McCreary, J.P.; Qiu, B.; Qi, Y.; Du, Y.; Chen, X. Dynamics of Eddy Generation in the Central Bay of Bengal. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2018, 123, 6861–6875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P.; Nuncio, M.; Narvekar, J.; Kumar, A.; Sardesai, S.; Souza, S.N.D.; Gauns, M.; Ramaiah, N.; Madhupratap, M. Are Eddies Nature’s Trigger to Enhance Biological Productivity in the Bay of Bengal? Geophysical Research Letters 2004, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P.; Nuncio, M.; Ramaiah, N.; Sardesai, S.; Narvekar, J.; Fernandes, V.; Paul, J.T. Eddy-Mediated Biological Productivity in the Bay of Bengal during Fall and Spring Intermonsoons. Deep-Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 2007, 54, 1619–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Sil, S.; Pramanik, S.; Arunraj, K.S.; Jena, B.K. Characteristics and Evolution of a Coastal Mesoscale Eddy in the Western Bay of Bengal Monitored by High-Frequency Radars. Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans 2019, 88, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potemra, J.T.; Luther, M.E.; O’Brien, J.J. The Seasonal Circulation of the Upper Ocean in the Bay of Bengal. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 1991, 96, 12667–12683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, D.; McCreary, J.P.; Han, W.; Shetye, S.R. Dynamics of the East India Coastal Current: 1. Analytic Solutions Forced by Interior Ekman Pumping and Local Alongshore Winds. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 1996, 101, 13975–13991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, M.T.; Sarma, Y.V.B.; Murty, V.S.N.; Vethamony, P. On the Circulation in the Bay of Bengal during Northern Spring Inter-Monsoon (March–April 1987). Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 2003, 50, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wang, D.; Hou, Y. The Features and Interannual Variability Mechanism of Mesoscale Eddies in the Bay of Bengal. Continental Shelf Research 2012, 47, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurien, P.; Ikeda, M.; Valsala, V.K. Mesoscale Variability along the East Coast of India in Spring as Revealed from Satellite Data and OGCM Simulations. Journal of oceanography 2010, 66, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyadjro, E.S. Study on the Basin Scale Salt Exchange in the Indian Ocean Using Satellite Observations and Model Simulations. PhD Thesis, University of South Carolina, 2012.

- Sengupta, D.; Goddalehundi, B.R.; Anitha, D.S. Cyclone-Induced Mixing Does Not Cool SST in the Post-Monsoon North Bay of Bengal. Atmospheric Science Letters 2008, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayachandran, P.N.; Shetye, S.R.; Sengupta, D.; Gadgil, S. Forcing Mechanisms of the Bay of Bengal. Curr. Sci 1996, 70, 753–763. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Francis, P.A. Role of Andaman and Nicobar Islands in Eddy Formation along Western Boundary of the Bay of Bengal. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.P.; Muraleedharan, P.M.; Prasad, T.G.; Gauns, M.; Ramaiah, N.; Souza, S.N. de; Sardesai, S.; Madhupratap, M. Why Is the Bay of Bengal Less Productive during Summer Monsoon Compared to the Arabian Sea? Geophysical Research Letters 2002, 29, 88-1–88-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P.; Narvekar, J.; Nuncio, M.; Kumar, A.; Ramaiah, N.; Sardesai, S.; Gauns, M.; Fernandes, V.; Paul, J. Is the Biological Productivity in the Bay of Bengal Light Limited? Current science 2010, 1331–1339. [Google Scholar]

- Madhupratap, M.; Gauns, M.; Ramaiah, N.; Kumar, S.P.; Muraleedharan, P.M.; Sousa, S.N.D.; Sardessai, S.; Muraleedharan, U. Biogeochemistry of the Bay of Bengal: Physical, Chemical and Primary Productivity Characteristics of the Central and Western Bay of Bengal during Summer Monsoon 2001. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 2003, 50, 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, V.; Jagadeesan, L.; Dalabehera, H.B.; Rao, D.N.; Kumar, G.S.; Durgadevi, D.S.; Yadav, K.; Behera, S.; Priya, M.M.R. Role of Eddies on Intensity of Oxygen Minimum Zone in the Bay of Bengal. Continental Shelf Research 2018, 168, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulakaram, V.S.; Vissa, N.K.; Bhaskaran, P.K. Characteristics and Vertical Structure of Oceanic Mesoscale Eddies in the Bay of Bengal. Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans 2020, 89, 101131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkowski, P.G.; Ziemann, D.; Kolber, Z.; Bienfang, P.K. Role of Eddy Pumping in Enhancing Primary Production in the Ocean. Nature 1991, 352, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetye, S.R.; Gouveia, A.D.; Shenoi, S.S.C.; Sundar, D.; Michael, G.S.; Nampoothiri, G. The Western Boundary Current of the Seasonal Subtropical Gyre in the Bay of Bengal. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 1993, 98, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Gandhi, N.; Ramesh, R.; Prakash, S. Role of Cyclonic Eddy in Enhancing Primary and New Production in the Bay of Bengal. Journal of Sea Research 2015, 97, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Guo, Y.; Yun, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Thangaraj, S.; Zhao, W.; Sun, J. Variation in Biogenic Calcite Production by Coccolithophores across Mesoscale Eddies in the Bay of Bengal. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2022, 179, 113728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-González, I.J.; Arístegui, J.; Lee, C.; Sanchez-Vidal, A.; Calafat, A.; Fabrés, J.; Sangrá, P.; Mason, E. Carbon Dynamics within Cyclonic Eddies: Insights from a Biomarker Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhu, N.V.; Jyothibabu, R.; Maheswaran, P.A.; Gerson, V.J.; Gopalakrishnan, T.C.; Nair, K.K.C. Lack of Seasonality in Phytoplankton Standing Stock (Chlorophyll a) and Production in the Western Bay of Bengal. Continental Shelf Research 2006, 26, 1868–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrenfeld, M.J.; Falkowski, P.G. Photosynthetic Rates Derived from Satellite-Based Chlorophyll Concentration. Limnology and Oceanography 1997, 42, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, E.; Pascual, A.; McWilliams, J.C. A New Sea Surface Height–Based Code for Oceanic Mesoscale Eddy Tracking. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 2014, 31, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaigneau, A.; Gizolme, A.; Grados, C. Mesoscale Eddies off Peru in Altimeter Records: Identification Algorithms and Eddy Spatio-Temporal Patterns. Progress in Oceanography 2008, 79, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurian, J.; Colas, F.; Capet, X.; McWilliams, J.C.; Chelton, D.B. Eddy Properties in the California Current System. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2011, 116. [CrossRef]

- Nencioli, F.; Dong, C.; Dickey, T.; Washburn, L.; McWilliams, J.C. A Vector Geometry–Based Eddy Detection Algorithm and Its Application to a High-Resolution Numerical Model Product and High-Frequency Radar Surface Velocities in the Southern California Bight. Journal of atmospheric and oceanic technology 2010, 27, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelton, D.B.; Schlax, M.G.; Samelson, R.M. Global Observations of Nonlinear Mesoscale Eddies. Progress in oceanography 2011, 91, 167–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doglioli, A.M.; Blanke, B.; Speich, S.; Lapeyre, G. Tracking Coherent Structures in a Regional Ocean Model with Wavelet Analysis: Application to Cape Basin Eddies. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2007, 112. [CrossRef]

- Penven, P.; Echevin, V.; Pasapera, J.; Colas, F.; Tam, J. Average Circulation, Seasonal Cycle, and Mesoscale Dynamics of the Peru Current System: A Modeling Approach. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2005, 110.

- Waugh, D.W.; Abraham, E.R.; Bowen, M.M. Spatial Variations of Stirring in the Surface Ocean: A Case Study of the Tasman Sea. Journal of Physical Oceanography 2006, 36, 526–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isern-Fontanet, J.; Garc\’ıa-Ladona, E.; Font, J. Identification of Marine Eddies from Altimetric Maps. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 2003, 20, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, M. de; Backeberg, B.; Counillon, F. Using an Eddy-Tracking Algorithm to Understand the Impact of Assimilating Altimetry Data on the Eddy Characteristics of the Agulhas System. Ocean Dynamics 2018, 68, 1071–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, G.; Liu, Y.; Sun, W.; Xia, C.; Dong, C. Multi-Source Data Analysis of Mesoscale Eddies and Their Effects on Surface Chlorophyll in the Bay of Bengal. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuncio, M.; Kumar, S.P. Life Cycle of Eddies along the Western Boundary of the Bay of Bengal and Their Implications. Journal of Marine Systems 2012, 94, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraleedharan, K.R.; Jasmine, P.; Achuthankutty, C.T.; Revichandran, C.; Dinesh Kumar, P.K.; Anand, P.; Rejomon, G. Influence of Basin-Scale and Mesoscale Physical Processes on Biological Productivity in the Bay of Bengal during the Summer Monsoon. Progress in Oceanography 2007, 72, 364–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Xie, S.-P.; McCreary, J.P.; Qi, Y.; Du, Y. Intraseasonal Variability of Sea Surface Height in the Bay of Bengal. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2013, 118, 816–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinglong, C.; Qiu, Y.; Xinyu, L.; Chunsheng, J. General Features and Seasonal Variation of Mesoscale Eddies in the Bay of Bengal. J. Appl. Oceanogr 2019, 38, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Jose, F. Seasonal Influence of Freshwater Discharge on Primary Productivity and Euphotic Depth in the Northern Bay of Bengal. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2023–2023 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium; IEEE: Pasadena, CA, USA, July 16, 2023; pp. 4023–4024. [Google Scholar]

- Hareesh Kumar, P.V.; Mathew, B.; Ramesh Kumar, M.R.; Raghunadha Rao, A.; Jagadeesh, P.S.V.; Radhakrishnan, K.G.; Shyni, T.N. ‘Thermohaline Front’ off the East Coast of India and Its Generating Mechanism. Ocean Dynamics 2013, 63, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenheer, A.; Quadfasel, D. Seasonal Variability of the Bay of Bengal Circulation Inferred from TOPEX/Poseidon Altimetry. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2000, 105, 3243–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golder, M.R.; Shuva, M.S.H.; Rouf, M.A.; Uddin, M.M.; Bristy, S.K.; Bir, J. Chlorophyll-a, SST and Particulate Organic Carbon in Response to the Cyclone Amphan in the Bay of Bengal. J Earth Syst Sci 2021, 130, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. J., V.; Das, S.; Murali.R, M. Contrasting Chl-a Responses to the Tropical Cyclones Thane and Phailin in the Bay of Bengal. Journal of Marine Systems 2017, 165, 103–114. [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhan, H.; Cai, S. Anticyclonic Eddies Enhance the Winter Barrier Layer and Surface Cooling in the Bay of Bengal. JGR Oceans 2020, 125, e2020JC016524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Sil, S. Spatio-Temporal Variability of Coastal Upwelling Using High Resolution Remote Sensing Observations in the Bay of Bengal. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2023, 282, 108228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.A.; Banas, N.S.; Giddings, S.N.; Siedlecki, S.A.; MacCready, P.; Lessard, E.J.; Kudela, R.M.; Hickey, B.M. Estuary-enhanced Upwelling of Marine Nutrients Fuels Coastal Productivity in the U. S. P Acific N Orthwest. JGR Oceans 2014, 119, 8778–8799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, S.; Caesar, J.; Janes, T. Marine Dynamics and Productivity in the Bay of Bengal. 2018.

- Ray, S.; Swain, D.; Ali, M.M.; Bourassa, M.A. Coastal Upwelling in the Western Bay of Bengal: Role of Local and Remote Windstress. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaigneau, A.; Le Texier, M.; Eldin, G.; Grados, C.; Pizarro, O. Vertical Structure of Mesoscale Eddies in the Eastern South Pacific Ocean: A Composite Analysis from Altimetry and Argo Profiling Floats. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, 2011JC007134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandapat, S.; Chakraborty, A. Mesoscale Eddies in the Western Bay of Bengal as Observed from Satellite Altimetry in 1993–2014: Statistical Characteristics, Variability and Three-Dimensional Properties. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2016, 9, 5044–5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornec, M.; Laxenaire, R.; Speich, S.; Claustre, H. Impact of Mesoscale Eddies on Deep Chlorophyll Maxima. Geophysical Research Letters 2021, 48, e2021GL093470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).