1. Introduction

Mesoscale eddies, which encompass spatial scales ranging from 10 to 100 kilometers and temporal scales from weeks to months, are significant drivers of complex interactions within the ocean, including its physics, biology, and biogeochemistry [

1]. These eddies are commonly observed in west boundary currents and are characterized by strong vertical and horizontal currents. The Kuroshio Extension (KE), situated in the North Pacific Ocean, is a notable component of the western boundary current. It is distinguished by its elevated temperature, salinity, flow velocity, and noticeable ocean color [

2].

The Kuroshio Extension (KE) region is renowned for its prominent ocean front and the highest eddy kinetic energy globally. This unique oceanic area is influenced by various factors, including topography, monsoons, and the western boundary current. These factors contribute to the manifestation of complex and dynamic characteristics observed in the eddies present within the KE [

3]. Throughout the lifecycle of an eddy, from its formation to dissipation, it actively transports its internal water mass in a westward direction. This transport is facilitated by a range of physical processes, including eddy stirring, trapping, pumping, and eddy-wind Ekman pumping [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. These processes play a crucial role in facilitating horizontal exchange and vertical transport of physical and chemical constituents, such as heat, salt, kinetic energy, nutrients, and phytoplankton. The physical and biological processes within eddies has a significant impact on the ecological environment of the upper ocean [

11,

12,

13]. The widely accepted eddy pumping process, based on satellite measurements of cyclonic (anticyclonic) eddies, suggests that the uplifting (deepening) of isopycnals and nitrate into (out of) the euphotic zone stimulates (inhibits) phytoplankton growth, resulting in elevated (reduced) concentrations of chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. With the advancement of Argo and Bio-Argo float deployments, researchers now have effective tools to explore the subsurface dynamics within eddies without relying solely on satellite observations. In a more recent study, Dufois et al. [

8] conducted cruise observations and provided evidence that anticyclonic eddies in subtropical gyres exhibit intensified surface Chl-a concentrations during winter, attributed to convective mixing stirring the subsurface Chl-a maximum. Wang et al. [

9] proposed that winter cyclonic eddies (CE) promote enhanced vertical blooms dominated by phytoplankton biomass due to shallow mixed layers and uplifted thermoclines.

In South China Sea, He et al. [

10] found that intense downwelling within anticyclone eddies (ACE) leads to a substantially deeper and less pronounced subsurface Chl-a maximum compared to CE during summer. In the North Subtropical Pacific, Huang et al. [

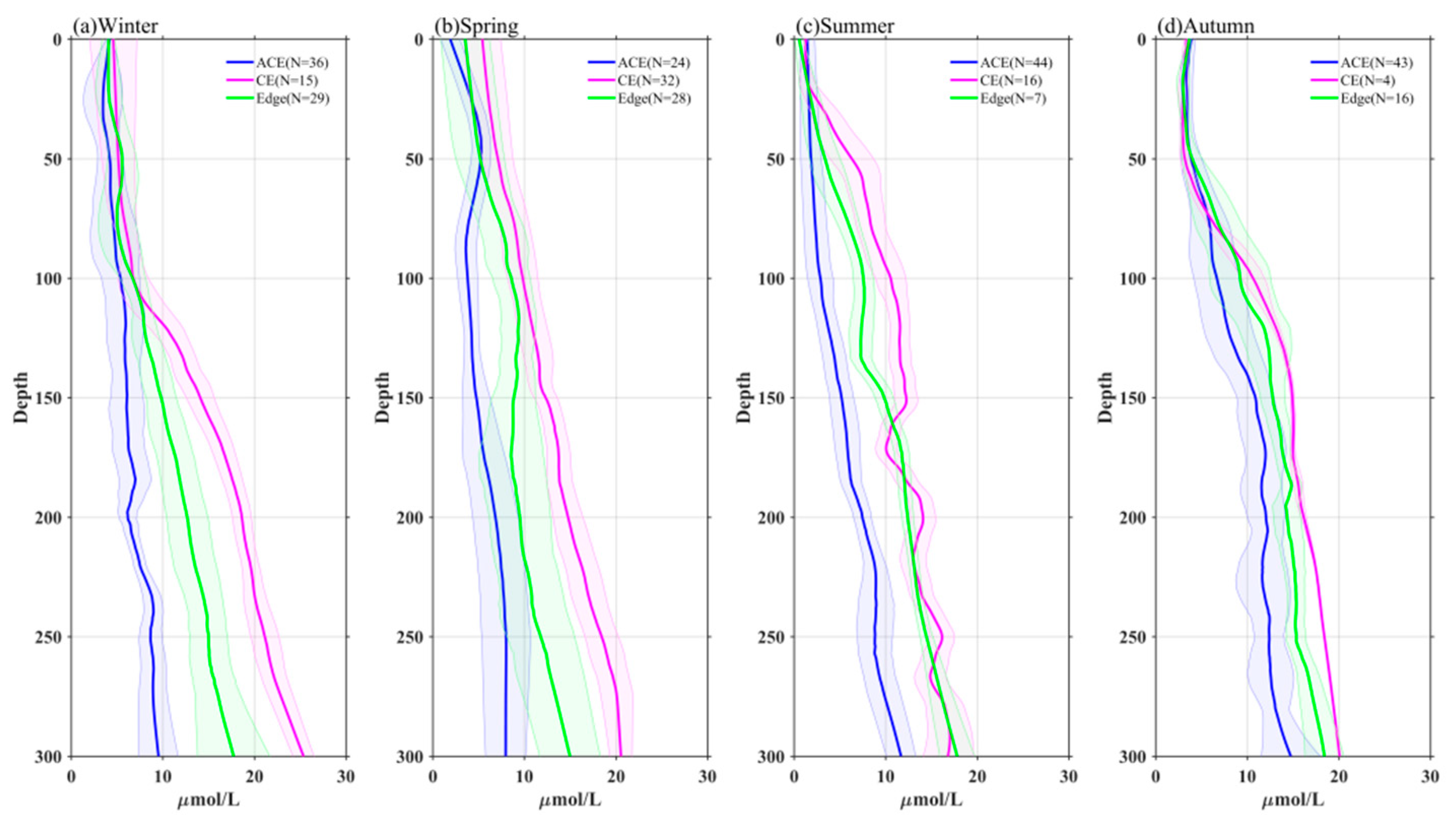

12] conducted studies and observed that the depth-integrated nitrate and Chl-a anomalies within eddies are generally within ±90% for nitrate and ±10% for Chl-a in the euphotic layer. However, it is worth noting that the magnitudes of these anomalies can vary significantly depending on individual eddy analyses. Rii et al. [

21] and Bidigare et al. [

22] reported substantial increases in anomalies within CE compared to areas outside of eddies, with magnitudes ranging from 3.3 to 9.0 times and 1.0 to 1.5 times, respectively. These variations highlight the importance of incorporating a significant amount of subsurface observation data to distinguish the contributions of different physical processes. Overall, Previous studies have provided valuable observational evidence concerning regional variations in the biogeochemical response to eddies. Nevertheless, the biogeochemical response driven by eddies remains unclear, particularly with regard to different seasons.

This study examines the seasonal variations in eddy-driven biogeochemical responses in the KE using satellite data and decades of oceanographic observation data. Eddy-associated surface Chl-a anomalies spanning 21 years are composited onto eddy-centric coordinates. Additionally, Argo floats are used to normalize Chl-a, nutrient, temperature, and salinity measurements into a standardized vertical profile, allowing for a statistical analysis of the vertical structure ( physical and biological) of eddies in the KE under different seasons. OFES outputs is used to evaluated the contribution of mesoscale dynamics to nutrient transport.

4. Discussion

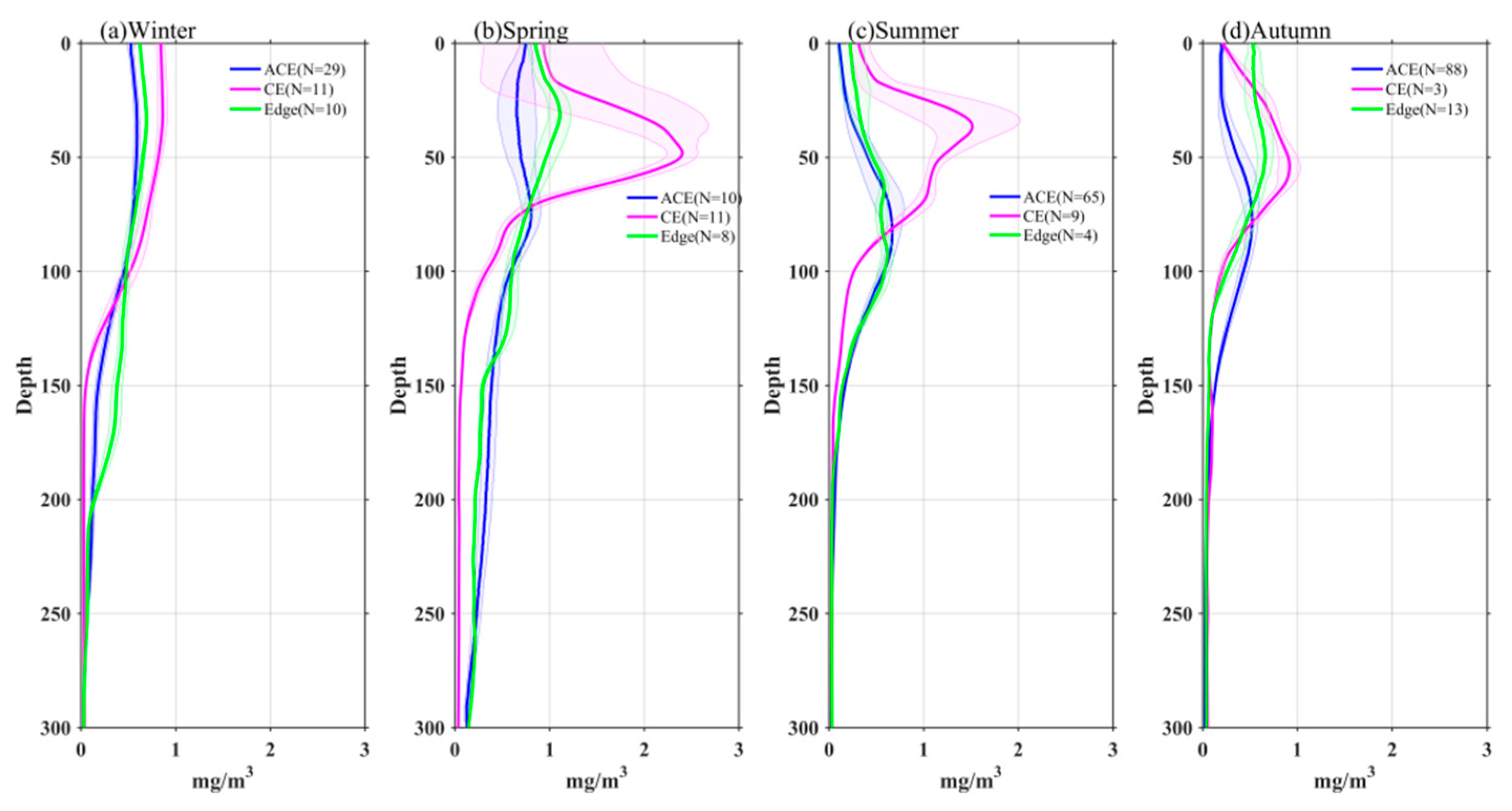

In this study, we have observed that CEs in the KE region exhibit higher surface Chl-a concentrations compared to the edge values, while ACEs show lower surface Chl-a concentrations. This pattern is particularly pronounced during the cold seasons (winter and spring) when Chl-a levels are typically at their highest. The analysis of Chl-a patterns within eddies, using EOF analysis, has revealed the complexity of these relationships, indicating that multiple mechanisms contribute to the interaction between eddies and Chl-a dynamics.

Nutrients and light availability are crucial factors influencing phytoplankton blooms. Eddies play a significant role in shaping the vertical distribution of Chl-a and nitrate through processes such as eddy pumping, eddy Ekman pumping, eddy stirring, variations in light conditions, and vertical mixing, which vary across different seasons [

12,

16,

34]. The modulation of the MLD by eddies has also been identified as a contributing factor to elevated Chl-a levels [

8,

18]. In our study, we followed the approaches of previous researchers [

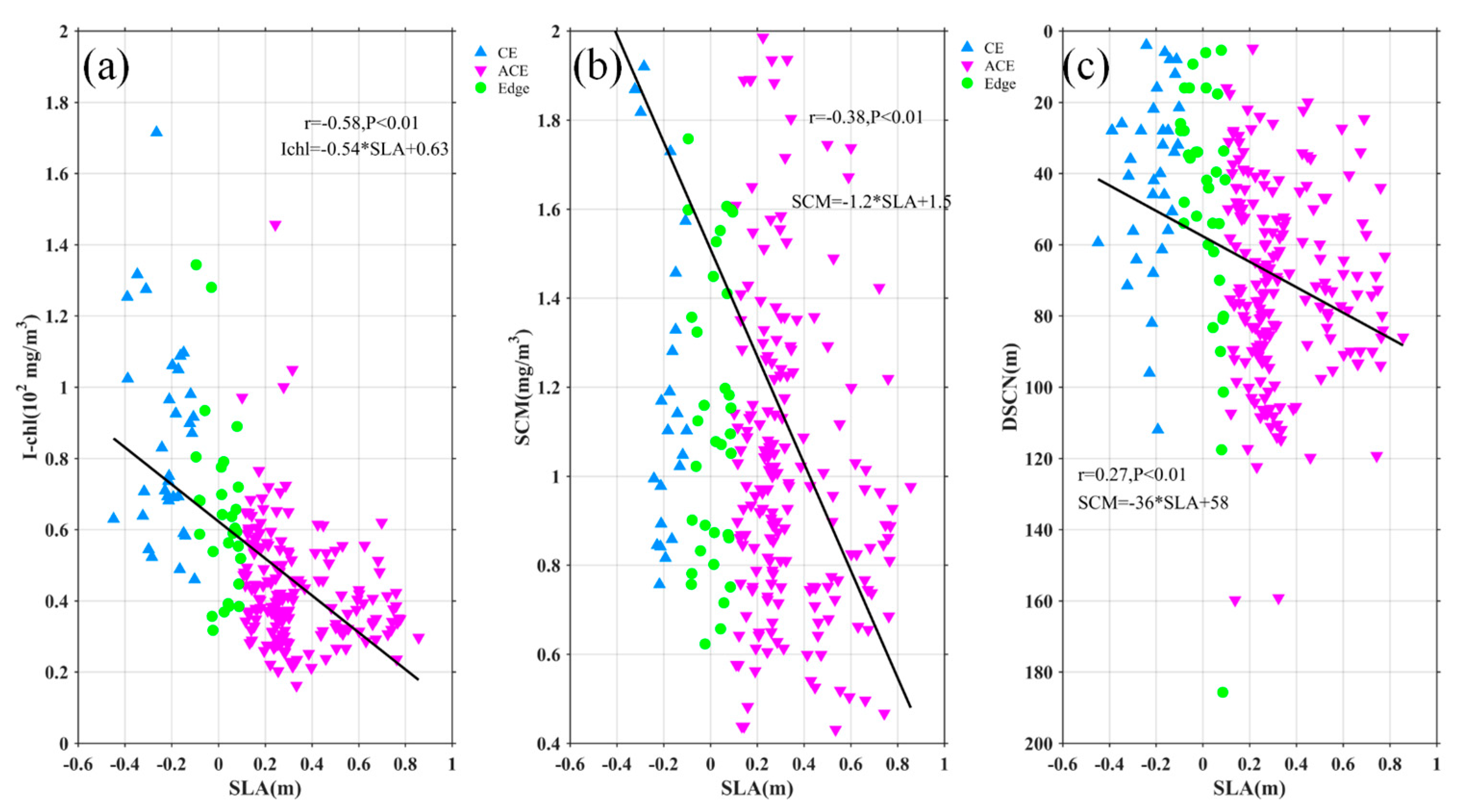

16,

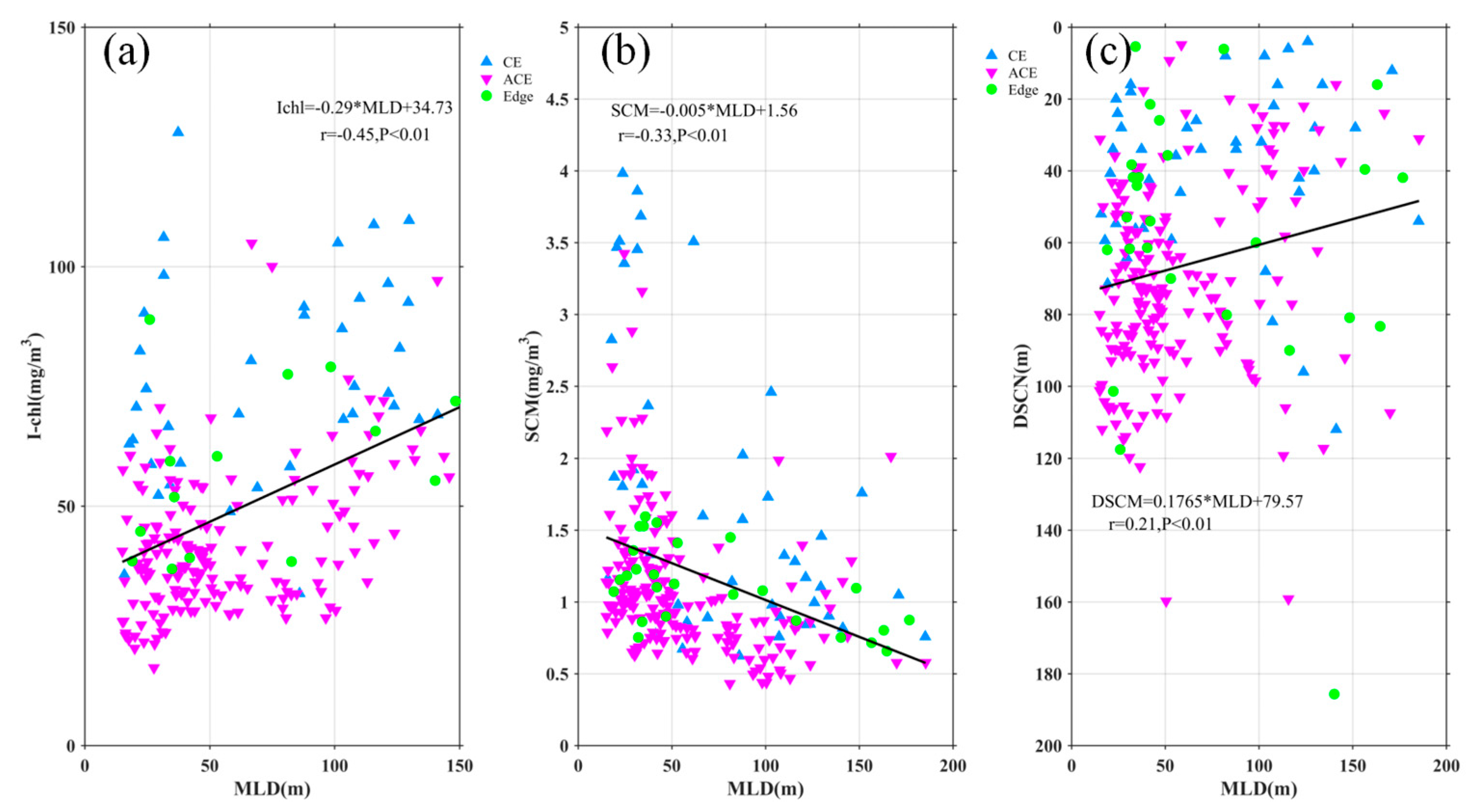

35] to investigate how MLD within eddies affects the distribution of Chl-a and nitrate. Despite the seasonal variation in our data, the integrated Chl-a (I-Chl), SCM, and deep SCM (DSCM) showed significant correlations with SLA (r = -0.58, -0.38, -0.27;

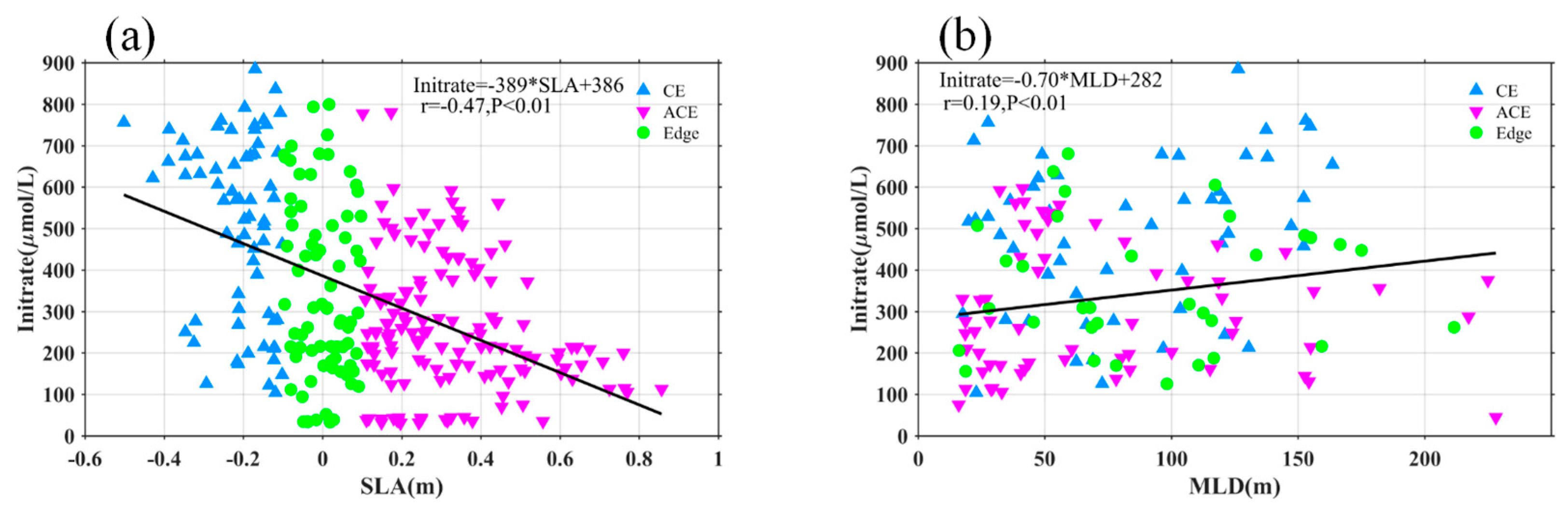

Figure 10), all with p < 0.01. Similarly, integrated nitrate (I-nitrate) exhibited a strong negative correlation (r = -0.47, p < 0.01) with SLA (

Figure 12a). These findings indicate that I-Chl, SCM, DSCM, and I-nitrate are more pronounced within CEs compared to the eddy edges, but weaker within ACEs. Furthermore,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13b demonstrate a significant correlation between I-Chl, SCM, DSCM, I-nitrate, and MLD (r = 0.45, -0.33, -0.21, 0.19;

Figure 11 and 12b), all with p < 0.01. Deeper MLD corresponds to decreased SCM and DSCM by factors of 0.005 mg/m

4 and 0.1765 m, respectively. Conversely, I-Chl and I-nitrate increase linearly by factors of 0.29 mg/m

4 and 0.75 μmol/L/m, respectively, with MLD deepening. Notably, most CEs (blue marks) exhibit larger SCM, DSCM, I-Chl, and I-nitrate values compared to ACEs (pink marks). Previous studies have demonstrated that CEs are associated with shallower euphotic depths than ACEs, providing more favorable light conditions for phytoplankton growth and leading to larger SCM and I-Chl values [

14,

15,

16,

36]. These findings highlight the critical role of nutrient supply in driving phytoplankton blooms.

The modulation of MLD within eddies plays a significant role in shaping the distribution of Chl-a. Generally, CEs (ACEs) enhance (dampen) nutrient supply through eddy-induced upwelling (downwelling), leading to high (low) Chl-a concentrations [

5]. Previous studies have shown that eddy pumping is the dominant mechanism controlling the biogeochemical response in eddies, resulting in upward and downward displacement of the SCM layer [

12]. However, other studies propose that ACEs are more productive than CEs in subtropical gyres due to winter deeper mixing (MLD), which enhances nutrient supply to the mixed layer and/or redistributes Chl-a through stirring of the SCM [

7,

8,

18]. In summer, the shallow MLD without strong vertical mixing does not promote the stirring of the SCM [

16].

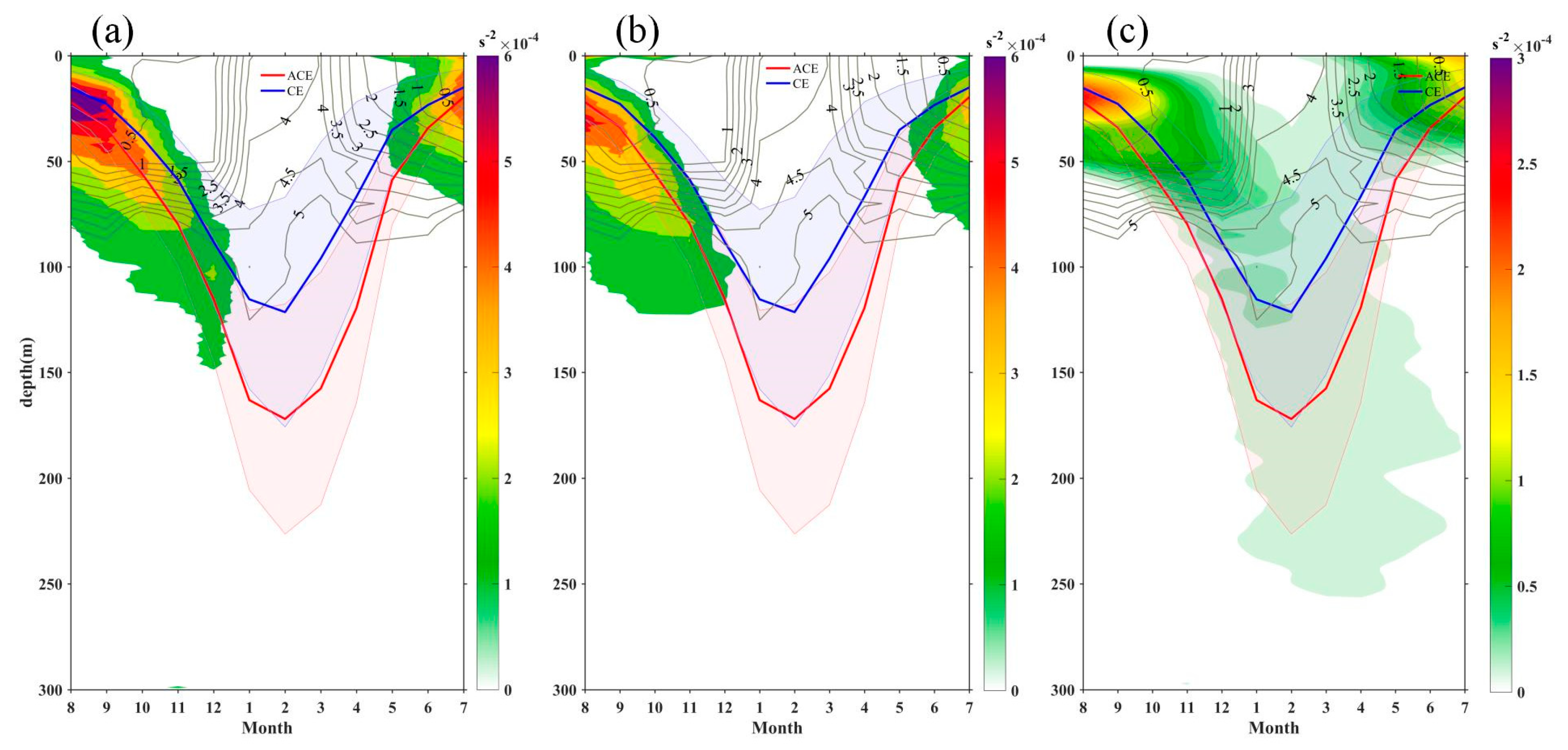

Figure 13 illustrates that changes in the MLD are influenced by turbulent vertical mixing and adiabatic processes associated with vertical stretching and/or eddy pumping [

18]. Eddy pumping leads to a deeper MLD in ACEs compared to CEs throughout the year, with the most significant differences observed in winter. Both ACEs and CEs exhibit a shallow mixed layer with stable water (stronger N2) throughout the year (

Figure 13a and b). From summer to winter, as the mixed layer deepens, the shallow stratification dissipates, and the nitrate flux peaks by the end of winter. Subsequently, the water column undergoes restratification starting from spring. In CE (ACE), the summer stratification is stronger (weaker) than that in ACE (CE), resulting in a shallower (deeper) MLD, which facilitates a greater (smaller) injection of nutrients into the mixed layer during winter (

Figure 13). However, these changes in MLD do not align with the occurrence of higher (lower) average Chl-a concentrations in CEs (ACEs). It is worth noting that negative (positive) Chl-a values in the core of CEs (ACEs) account for a significant proportion of the total CEs (ACEs) during winter (24% and 19%, respectively). This suggests that the differences in stratification during winter convective mixing, leading to variations in nutrient supply, may contribute to negative (positive) Chl-a concentrations in the core of CEs (ACEs). The opposite Chl-a phase can also be attributed to eddy stirring, which traps areas of high and low Chl-a concentrations, and/or eddy Ekman pumping [

37].

Additionally, it is important to consider the influence of submesoscale processes in the KE system, which are most pronounced during winter and spring [

38]. Submesoscale features exhibit higher vertical velocities compared to eddies [

39], making them important contributors to phytoplankton production by transporting nutrients and phytoplankton into the sunlit ocean [

40,

41,

42]. This transport mechanism plays a significant role in promoting phytoplankton production. Although the analysis in this study may not fully capture the submesoscale features due to the spatial resolution of the data and potential obscuration in the EOF patterns, it is essential to acknowledge their potential influence for a comprehensive understanding of the biogeochemical dynamics in the KE system.

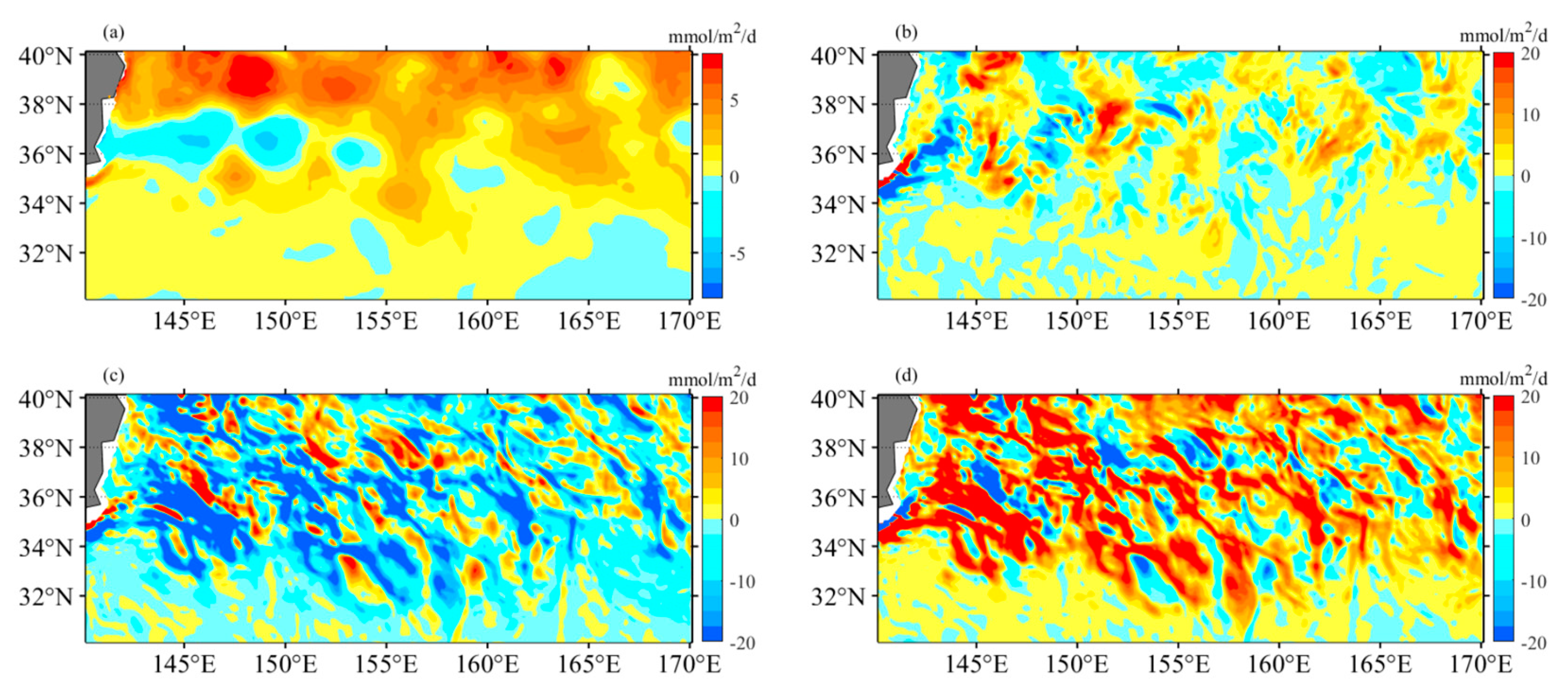

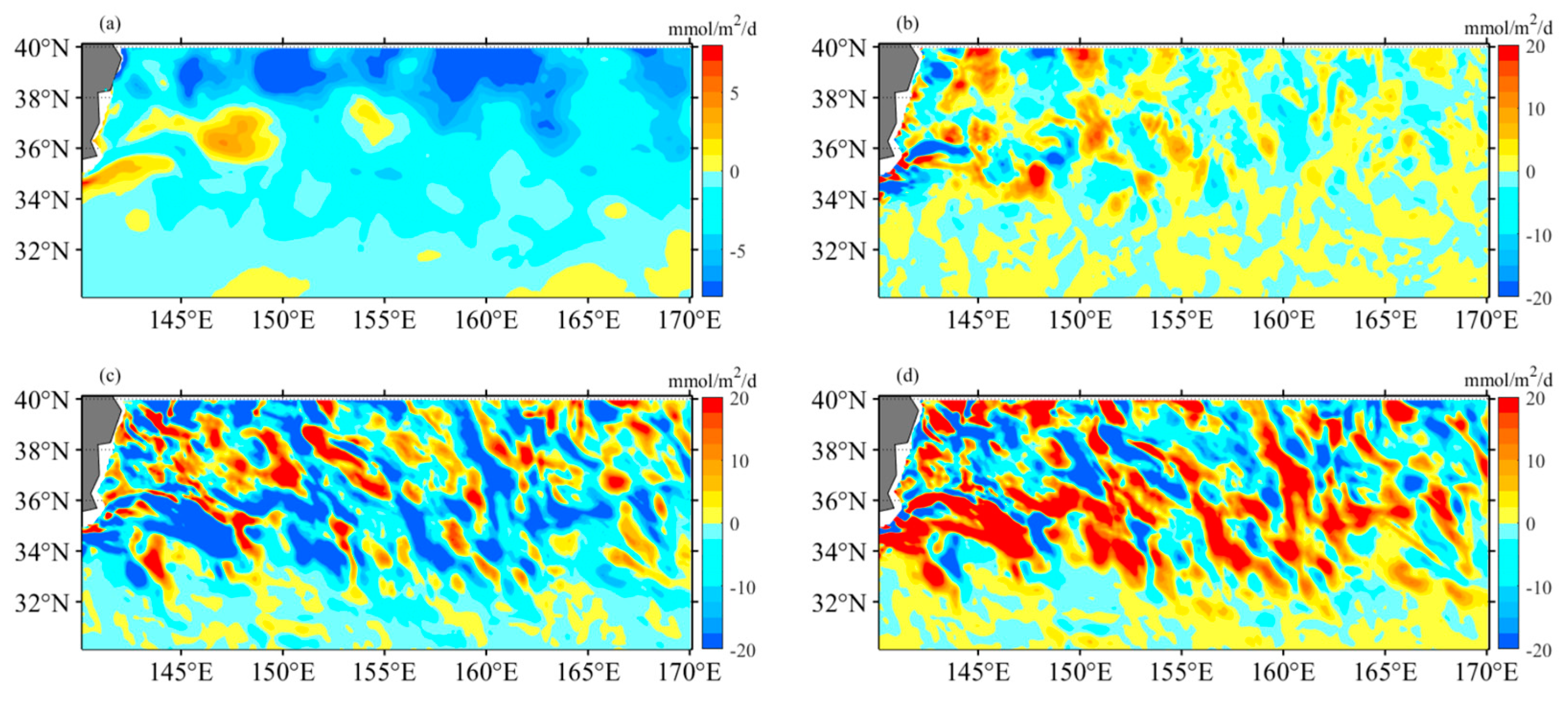

To assess the influence of mesoscale dynamics on biological production, the mixed-layer nitrogen budget is analyzed using the OFES hydrography-biology products [

9,

28]. The nitrogen change in the OFES model (in mmol m-2 d-1) is divided into three components: mean advective flow, eddy flow, and mixing. During winter, the average nitrate increase is 2.67, with the three components contributing as follows: 0.54 (mean advective flow), -5.13 (eddy flow), and 7.26 (mixing) (

Figure 14). In contrast, summer exhibits an average nitrate decrease of 4.64, with the three components contributing as follows: -0.34 (mean advective flow), -5.93 (eddy flow), and 1.64 (mixing) (

Figure 15). These results indicate that eddy flows play a significant role in nutrient depletion, while the mean flow has a relatively minor impact and contributes minimally to nutrient changes. The magnitude of these flows does not exhibit clear seasonal variation. On the other hand, the mixing component displays substantial variations in magnitude. Therefore, the seasonal variation of nitrate primarily depends on the influence of vertical mixing, highlighting the contribution of convective mixing processes to nutrient increase (winter) or decrease (summer) in the KE region.

5. Conclusions

This study investigates the influence of mesoscale and submesoscale processes on biological production in the KE System. Using remote sensing and Argo floats, the researchers explore how eddies modify surface and subsurface Chl-a concentrations. CE and ACE induce positive and negative surface Chl-a anomalies, respectively, particularly in winter. This is due to the lifting or deepening of isopycnals and nitrate, stimulating or depressing phytoplankton growth. Consequently, CE and ACE result in variations in SCM depth-integrated Chl-a, and nitrate. These anomalies are mainly located near the main axis of the KE. Monopole Chl-a patterns within eddy centers correspond to positive or negative anomalies, depending on the principal component's sign. Chl-a concentrations above the SCM layer in CE and ACE are higher and lower than the edge values, respectively, while those below exhibit the opposite pattern, regardless of winter variations. Negative and positive Chl-a anomalies account for approximately 26% and 18% of the total CE and ACE, respectively, across all seasons. Nutrient supply resulting from stratification differences under convective mixing and eddy stirring may contribute to these anomalies. The study also highlights the role of submesoscale processes, such as higher vertical velocity in winter and spring, in transporting nutrients and phytoplankton into the sunlit ocean and promoting significant phytoplankton production. However, the study acknowledges the need for improved spatial resolution and comprehensive observations to fully understand submesoscale processes. Another study examined MLD adjustment in eddies, revealing the influence of eddy-induced upwelling and downwelling in CE and ACE on nutrient supply and Chl-a concentrations. The differences between CE and ACE are more significant in winter due to deeper mixing, enhanced nutrient supply, and redistribution of Chl-a. The shallow mixed layer and stratification in summer affect nutrient injection and contribute to variations in Chl-a concentrations. Convective mixing processes also play a role in nutrient increase or decrease during winter and summer, respectively. Overall, this study highlights the importance of mesoscale and submesoscale processes in driving biological productivity in the KE system.

Overall, the study emphasizes the importance of mesoscale and submesoscale processes in driving biological productivity and provides insights into the mechanisms underlying nutrient supply and Chl-a distributions in the KE system. While shedding light on these dynamics, the study acknowledges the need for future research to improve spatial resolution and incorporate comprehensive observations for a better understanding of submesoscale features and their impacts.

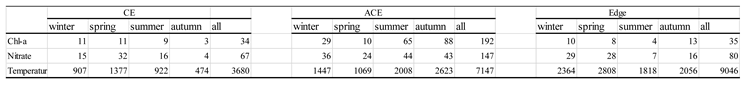

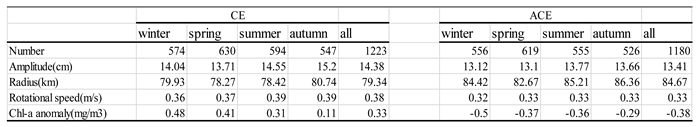

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of standard deviation for SLA from 1993 to 2020 year.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of standard deviation for SLA from 1993 to 2020 year.

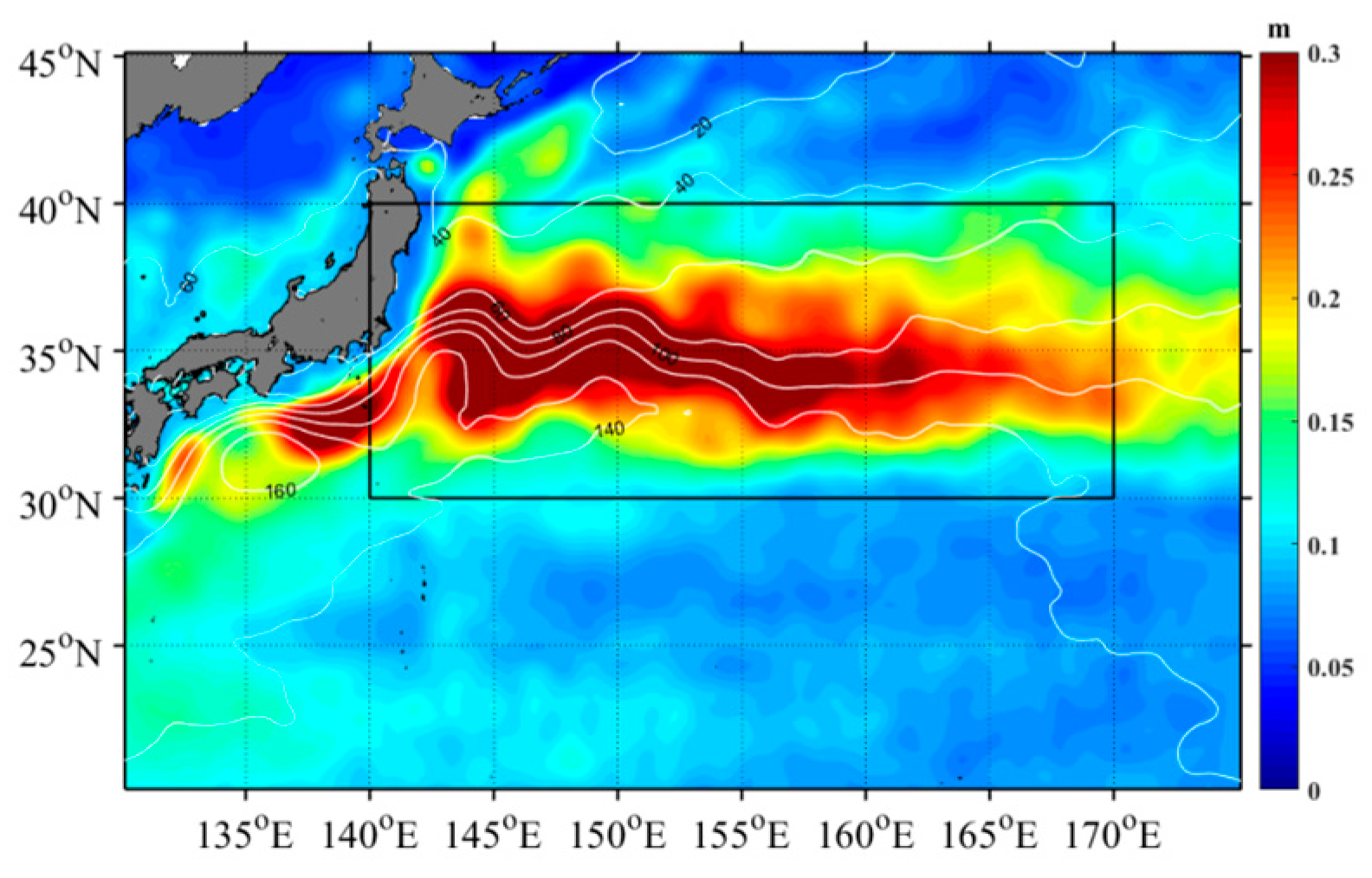

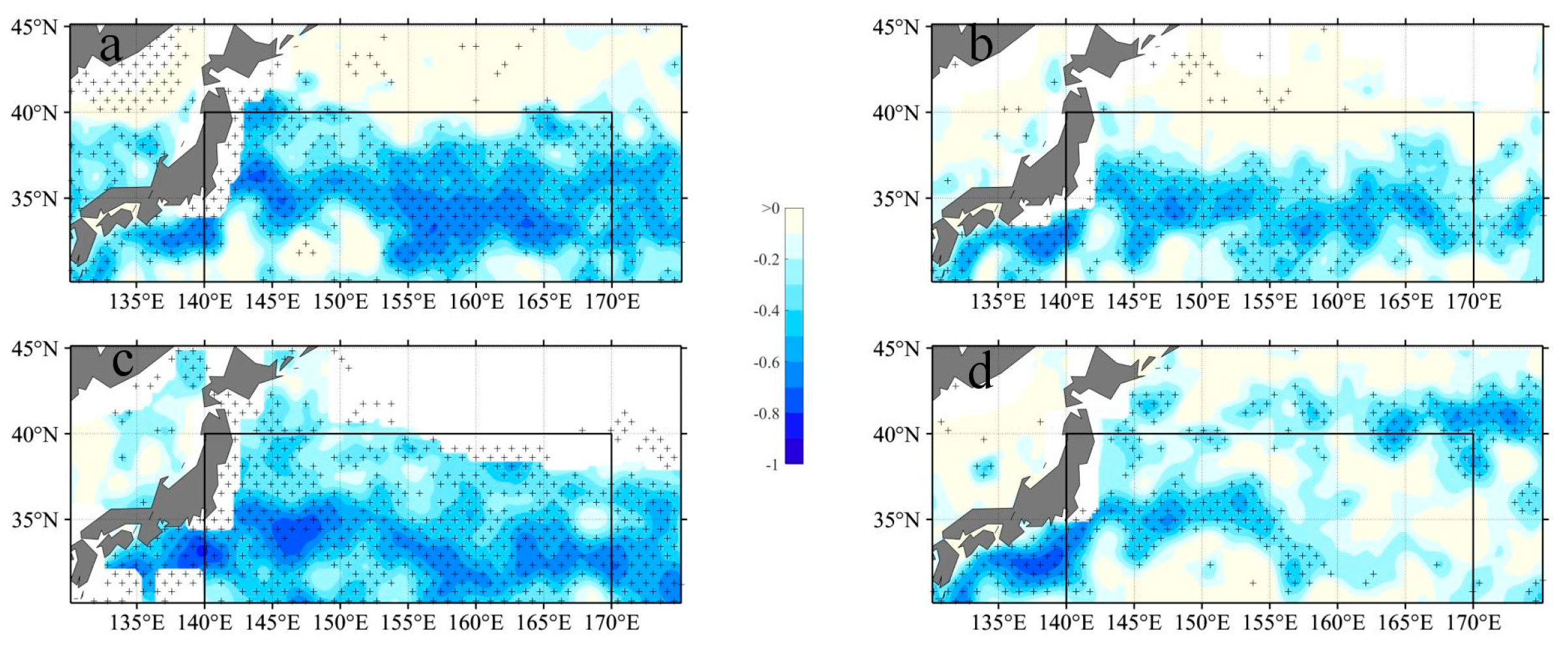

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of correlation(a:winter; b:spring; c:summer; d:autumn) between SLA and Chl-a anomaly corresponding to eddies from 1993 to 2017. Plus sign denote significant correlations at a 95 % confidence level.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of correlation(a:winter; b:spring; c:summer; d:autumn) between SLA and Chl-a anomaly corresponding to eddies from 1993 to 2017. Plus sign denote significant correlations at a 95 % confidence level.

Figure 3.

Composite averages of winter (a and c), spring (b and f), summer (c and g) and autumn (d and h) Chl-a anomalies associated with Cyclonic and Anticyclonic eddy in the KE during the period 1998 to 2016. Inner and outer circles respectively coincide with r/R<1 and r/R<2.

Figure 3.

Composite averages of winter (a and c), spring (b and f), summer (c and g) and autumn (d and h) Chl-a anomalies associated with Cyclonic and Anticyclonic eddy in the KE during the period 1998 to 2016. Inner and outer circles respectively coincide with r/R<1 and r/R<2.

Figure 4.

The first three spatial empirical orthogonal function (EOF) mode of Chl-a within Cyclonic eddy in winter (first column),spring (second column), summer (third column) and autumn (fourth column).

Figure 4.

The first three spatial empirical orthogonal function (EOF) mode of Chl-a within Cyclonic eddy in winter (first column),spring (second column), summer (third column) and autumn (fourth column).

Figure 5.

The first three spatial empirical orthogonal function (EOF) mode of Chl-a within Anticyclonic eddy in winter (first column), spring (second column), summer (third column) and autumn (fourth column).

Figure 5.

The first three spatial empirical orthogonal function (EOF) mode of Chl-a within Anticyclonic eddy in winter (first column), spring (second column), summer (third column) and autumn (fourth column).

Figure 6.

Mean regional winter (a,b,c), spring (d,e,f), summer (g,h,i) and autumn (j,k,l) Chl-a anomalies within Cyclonic and Anticyclonic eddy in the KE during the period 1998 to 2016. Quantified at each 0.5 × 0.5 pixel.

Figure 6.

Mean regional winter (a,b,c), spring (d,e,f), summer (g,h,i) and autumn (j,k,l) Chl-a anomalies within Cyclonic and Anticyclonic eddy in the KE during the period 1998 to 2016. Quantified at each 0.5 × 0.5 pixel.

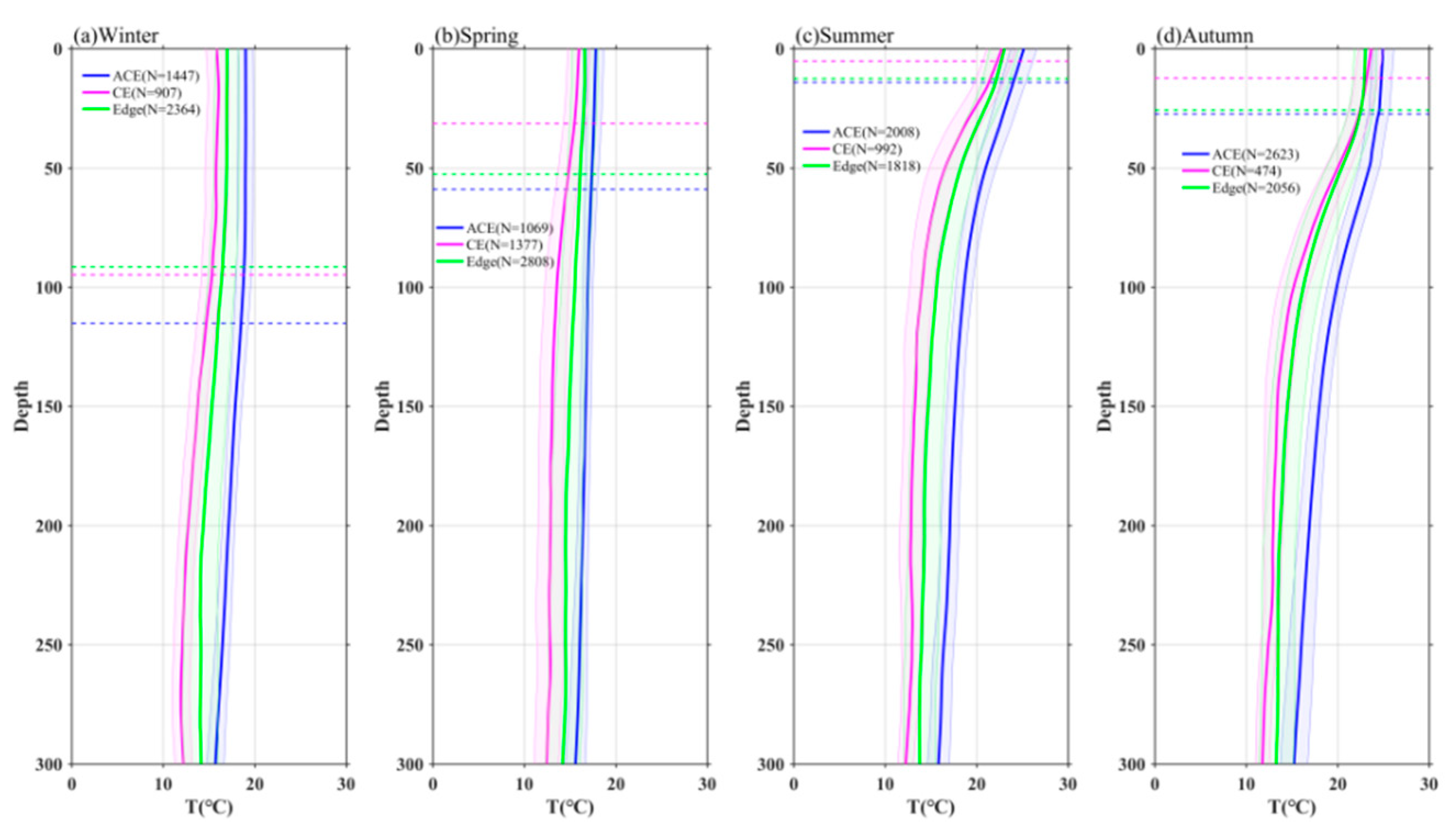

Figure 7.

Vertical profiles of temperature in eddies during winter(a), spring(b), summer(c) and autumn(d). Composite mean vertical profiles for cyclonic eddies (pink), anticyclonic eddies (blue), and edge (green). N indicates the number of profiles. The shading are standard errors. Dotted line represents mixed layer depth.

Figure 7.

Vertical profiles of temperature in eddies during winter(a), spring(b), summer(c) and autumn(d). Composite mean vertical profiles for cyclonic eddies (pink), anticyclonic eddies (blue), and edge (green). N indicates the number of profiles. The shading are standard errors. Dotted line represents mixed layer depth.

Figure 8.

Vertical profiles of Chl-a in eddies during winter(a), spring(b), summer(c) and autumn(d). The shading are standard errors.

Figure 8.

Vertical profiles of Chl-a in eddies during winter(a), spring(b), summer(c) and autumn(d). The shading are standard errors.

Figure 9.

Vertical profiles of nitrate in eddies during winter(a), spring(b), summer(c) and autumn(d). The shading are standard errors.

Figure 9.

Vertical profiles of nitrate in eddies during winter(a), spring(b), summer(c) and autumn(d). The shading are standard errors.

Figure 10.

Statistical relationship between the depth-integrated Chl-a (a), SCM(b), DSCM(c) and SLA. The blue, pink and green marks represent the observations in the CE, ACE and edge, respectively. The black solid lines are the linear regressions.

Figure 10.

Statistical relationship between the depth-integrated Chl-a (a), SCM(b), DSCM(c) and SLA. The blue, pink and green marks represent the observations in the CE, ACE and edge, respectively. The black solid lines are the linear regressions.

Figure 11.

Statistical relationship between the depth-integrated Chl-a(a), SCM(b), DSCM(c) and MLD. The blue, pink and green marks represent the observations in the CE, ACE, and edge, respectively. The black solid lines are the linear regressions.

Figure 11.

Statistical relationship between the depth-integrated Chl-a(a), SCM(b), DSCM(c) and MLD. The blue, pink and green marks represent the observations in the CE, ACE, and edge, respectively. The black solid lines are the linear regressions.

Figure 12.

Statistical relationship between the depth-integrated nitrate and SLA (a), MLD (b). The blue, pink and green marks represent the observations in the CE, ACE, and edge, respectively. The black solid lines are the linear regressions.

Figure 12.

Statistical relationship between the depth-integrated nitrate and SLA (a), MLD (b). The blue, pink and green marks represent the observations in the CE, ACE, and edge, respectively. The black solid lines are the linear regressions.

Figure 13.

Buoyancy frequency (shading) and MLD (blue and red lines)) from Argo floats within CEs (a) and ACEs (b) in KE. (c) buoyancy frequency difference between CEs and ACEs. The grey lines correspond to the nitrate mean seasonal contours.

Figure 13.

Buoyancy frequency (shading) and MLD (blue and red lines)) from Argo floats within CEs (a) and ACEs (b) in KE. (c) buoyancy frequency difference between CEs and ACEs. The grey lines correspond to the nitrate mean seasonal contours.

Figure 14.

The nitrogen budget analysis using the OFES hydrography-biology products provides estimates of nitrate changes (in mmol m−2 d−1) within the mixed layer during the winter period from 1999 to 2009. Four components are considered: (a) the total change in nitrate, (b) the mean advective-induced component (horizontal + vertical), (c) the eddy-induced component (horizontal + vertical), and (d) the mixing component.

Figure 14.

The nitrogen budget analysis using the OFES hydrography-biology products provides estimates of nitrate changes (in mmol m−2 d−1) within the mixed layer during the winter period from 1999 to 2009. Four components are considered: (a) the total change in nitrate, (b) the mean advective-induced component (horizontal + vertical), (c) the eddy-induced component (horizontal + vertical), and (d) the mixing component.

Figure 15.

The nitrogen budget analysis using the OFES hydrography-biology products provides estimates of nitrate changes (in mmol m−2 d−1) within the mixed layer during the summer period from 1999 to 2009. Four components are considered: (a) the total change in nitrate, (b) the mean advective-induced component (horizontal + vertical), (c) the eddy-induced component (horizontal + vertical), and (d) the mixing component.

Figure 15.

The nitrogen budget analysis using the OFES hydrography-biology products provides estimates of nitrate changes (in mmol m−2 d−1) within the mixed layer during the summer period from 1999 to 2009. Four components are considered: (a) the total change in nitrate, (b) the mean advective-induced component (horizontal + vertical), (c) the eddy-induced component (horizontal + vertical), and (d) the mixing component.