Submitted:

21 June 2024

Posted:

24 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Empathy Scale

2.2.2. Interpersonal Competence Questionnaire (ICQ)

2.2.3. Listening Skills Questionnaire

2.2.4. Competence Questionnaire for Psychological Councilors in Universities

2.3. Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias Test

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis among Variables

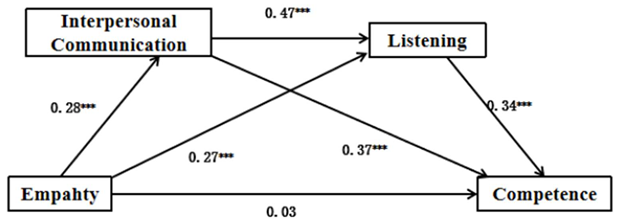

3.3. Chained Mediation Model Test

4. Discussion

4.1. The Relationship between Empathy and Competence

4.2. Separate Mediating Roles of Interpersonal Communication and Listening

4.3. Chain Mediating Role of Interpersonal Interaction and Listening

4.4. Theoretical and Practical Implications

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abejo, C.G.; Adanza, D.R.; Salvador, H.N.; Uy, M.N.; Indoc, S.M.; Abiol, M.J. The Influence of Interpersonal Skills of Working Students on Client Service Satisfaction in a Higher Educational Institution. International Journal of Multidisciplinary: Applied Business and Education Research 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, M.P.; Salzman, J.; EspinaRey, A.; Daly, K. Impact of Providing Peer Support on Medical Students’ Empathy, Self-Efficacy, and Mental Health Stigma. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almerich, G.; Suárez-Rodríguez, J.; Díaz-García, I.; Cifuentes, S.C. 21st-century competences: The relation of ICT competences with higher-order thinking capacities and teamwork competences in university students. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2020, 36, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, D.R.; Maissen, L.B.; Brockner, J. The role of listening in interpersonal influence. Journal of Research in Personality 2012, 46, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A. The Role of Interpersonal Communication Skills in Human Resource and Management. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Astiti, S.P. Efektivitas Konseling Sebaya (Peer Counseling) dalam Menuntaskan Masalah Siswa. Indonesian Journal of Islamic Psychology 2019, 1, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, C.; Schmutte, T.; Davidson, L. An update on the growing evidence base for peer support. Mental Health and Social Inclusion 2017, 21, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodie, G.D.; Vickery, A.J.; Cannava, K.; Jones, S.M. The Role of “Active Listening” in Informal Helping Conversations: Impact on Perceptions of Listener Helpfulness, Sensitivity, and Supportiveness and Discloser Emotional Improvement. Western Journal of Communication 2015, 79, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buie, D.H. Empathy: Its Nature and Limitations. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 1981, 29, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, D.; McKinney, K.J. Individual, interpersonal, and institutional level factors associated with the mental health of college students. Journal of American College Health 2012, 60, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caban, S.; Makos, S.; Thompson, C.M. The Role of Interpersonal Communication in Mental Health Literacy Interventions for Young People: A Theoretical Review. Health Communication 2023, 38, 2818–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Y.; Luo, D. . An analysis of the factors influencing the competence of undergraduate psychological counsellors. Psychology Monthly 2022, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, C.M. What is empathy, and can empathy be taught? Physical Therapy 1990, 70, 707–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, P.; Budiyanto, B.; Agustedi, A. The role of interpersonal communication in moderating the effect of work competence and stress on employee performance. Accounting. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.; Bohart, A.C.; Watson, J.C.; Greenberg, L.S. Empathy. Psychotherapy 2011, 48, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedesco, H.N. The Impact of (In)effective Listening on Interpersonal Interactions. International Journal of Listening 2015, 29, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, M.; de Jong, M.; Kamans, E.; Wolfensberger, M.; van Vuuren, M. Empathy Competencies and Behaviors in Professional Communication Interactions: Self Versus Client Assessments. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly 2023, 86, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearhart, C.C.; Bodie, G.D. Active-Empathic Listening as a General Social Skill: Evidence from Bivariate and Canonical Correlations. Communication Reports 2011, 24, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Ye, M.; Leng, Y. Revision and testing of the Interpersonal Reaction Pointer Scale in mainland China. Journal of Southeast University (Philosophy and Social Science Edition), 2013; (S1), 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hirn, S.L.; Thomas, J.; Zoelch, C. The role of empathy in the development of social competence: a study of German school leavers. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 2018, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, A.; Itzchakov, G. The Power of Listening at Work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, A.N.; Itzchakov, G. The power of listening at work. Annals of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behaviour 2022, 9, 121–146. [Google Scholar]

- Le Deist, F.D.; Winterton, J. What Is Competence? Human Resource Development International 2005, 8, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.T.; Chuang, S.S. The role of empathy between functional competence diversity and competence acquisition: a case study of interdisciplinary teams. Quality and Quantity 2018, 52, 2535–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-T.; Chuang, S.-S. The role of empathy between functional competence diversity and competence acquisition: a case study of interdisciplinary teams. Quality & Quantity 2018, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.-L.; Tang, B.-S. On the cultivation of college students' listening ability. Jiangsu Higher Education 2012, 139–140. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, N.; Cooper, C.; Lloyd-Evans, B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of group peer support interventions for people experiencing mental health conditions. BMC psychiatry 2021, 21, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manusov, V.; Stofleth, D.; Harvey, J.A.; Crowley, J.P. Conditions and Consequences of Listening Well for Interpersonal Relationships: Modeling Active-Empathic Listening, Social-Emotional Skills, Trait Mindfulness, and Relational Quality. International Journal of Listening 2018, 34, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March-Amengual, J.-M.; CambraBadii, I.; Casas-Baroy, J.-C.; Altarriba, C.; ComellaCompany, A.; Pujol-Farriols, R.; Baños, J.-E.; Galbany-Estragués, P.; ComellaCayuela, A. Psychological Distress, Burnout, and Academic Performance in First Year College Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayberry, M.L.; Espelage, D.L. Associations among empathy, social competence, & Reactive/Proactive aggression subtypes. Journal of youth and adolescence 2007, 36, 787–798. [Google Scholar]

- Nemec, P.B.; Spagnolo, A.C.; Soydan, A.S. Can you hear me now? Teaching listening skills. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2017, 40, 415–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetiawan, H. Konseling Teman Sebaya (Peer Counseling) Untuk Mereduksi Kecanduan Game Online. Counsellia: Jurnal Bimbingan dan Konseling 2016, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, M.V. The Functions of Empathy (Decentering) in Human Relations. Human Relations 1989, 42, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringwald, W.R.; Wright, A.G.C. The Affiliative role of empathy in everyday interpersonal interactions. European Journal of Personality 2021, 35, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmiati, R.; Lestari, M. Peer Counselor Training Untuk Mencengah Perilaku Bullying. Indonesia Journal of Learning Education and Counseling 2018, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsabila, S.; Wiryantara, J.; Salsabila, N.; Alhad, M.A. The Role of Peer Counseling on Mental Health. Bisma The Journal of Counseling 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segrin, C.G.; Taylor, M. Positive interpersonal relationships mediate the association between social skills and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences 2007, 43, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, M.B.; Cartner, S.; MacDonald, R.; Whitson, S.; Bailey, A.; Brown, E. The effectiveness of peer support from a person with lived experience of mental health challenges for young people with anxiety and depression: a systematic review. BMC psychiatry 2023, 23, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A. Role of Interpersonal Communication in Organizational Effectiveness. International Journal of Research in Management & Business Studies 2014, 1, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- So, C.; Fiori, K. Attachment anxiety and loneliness during the first-year of college: Self-esteem and social support as mediators. Personality and Individual Differences 2022, 187, 111405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheruvelil, K.S.; Soranno, P.A.; Weathers, K.C.; Hanson, P.C.; Goring, S.J.; Filstrup, C.T.; Read, E.K. Creating and maintaining high-performing collaborative research teams: The importance of diversity and interpersonal skills. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2014, 12, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, L.M.; Spencer, S.M. Competence at Work: Models for Superior Performance. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y. The Relationship Between College Students’ Interpersonal Relationship and Mental Health: Multiple Mediating Effect of Safety Awareness and College Planning. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 2023, 16, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weger, H.; Castle, R.; Emmett, M.C. Active Listening in Peer Interviews: The Influence of Message Paraphrasing on Perceptions of Listening Skill. International Journal of Listening 2010, 24, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Russell, D.W.; Zakalik, R.A. Adult Attachment, Social Self-Efficacy, Self-Disclosure, Loneliness, and Subsequent Depression for Freshman College Students: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Counseling Psychology 2005, 52, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Lin, X.; Li, X.; Xu, X.; Guo, H.; Sun, B.; Jiang, H. The Influence of Emotion and Empathy on Decisions to Help Others. Sage Open 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S. Competence model construction and questionnaire development of psychological members in colleges and universities (Master's thesis, Jiangxi Normal University). 2015.

- Zhan, Q.; Liu, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q. The development of a questionnaire on the listening ability of university psychologists. Chinese Journal of Mental Health 2021, 788–794. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, Q.; Zhang, C. The effects of empathy and interpersonal trust on the communication ability of university psychologists. Heilongjiang Higher Education Research 2020, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Zhu, Z. The character is tics and influencing factors of college students’ psychological qualities: based on an analysis of online survey data of college students. Educ Res 2022, 43, 126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, R.C. Psychological Diagnosis of College Students; Shandong Education Press: Jinan, 1999; pp. 339–345. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Fredrickson, B.L. Listen to resonate: Better listening as a gateway to interpersonal positivity resonance through enhanced sensory connection and perceived safety. Current opinion in psychology 2023, 53, 101669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| variables | M±SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Gender | 1.66±0.47 | 1 | ||||||

| 2Place of birth | 1.47±0.50 | ﹣0.05 | 1 | |||||

| 3Single-birth | 1.67±0.47 | 0.15** | ﹣0.47*** | 1 | ||||

| 4Empathy | 3.51±0.39 | 0.04 | 0.10* | ﹣0.08 | 1 | |||

| 5Interpersonal communication | 3.35±0.53 | ﹣0.04 | 0.13* | ﹣0.12* | 0.29*** | 1 | ||

| 6Listening | 3.22±0.39 | ﹣0.04 | 0.13** | ﹣0.18*** | 0.41*** | 0.56*** | 1 | |

| 7Competence | 3.97±0.56 | ﹣0.01 | 0.14** | ﹣0.17*** | 0.28*** | 0.58*** | 0.57*** | 1 |

| Regression Equation | Significance of Regression Coefficients | Fitting Index | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variable | Predictive Variables | β | t | R2 | F |

| Interpersonal Communication | Empathy | 0.28 | 5.64*** | 0.10 | 10.21*** |

| Gender | ﹣0.03 | ﹣0.67 | |||

| Place of birth | 0.07 | 1.25 | |||

| Single-birth | ﹣0.07 | ﹣1.10 | |||

| Listening | Empathy | 0.27 | 6.29*** | 0.39 | 48.07*** |

| Interpersonal Communication | 0.47 | 11.11*** | |||

| Gender | ﹣0.24 | ﹣0.58 | |||

| Place of birth | 0 | 0 | |||

| Single-birth | ﹣0.09 | ﹣2.00 | |||

| Competence | Empathy | 0.03 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 45.73*** |

| Interpersonal Communication | 0.37 | 7.73*** | |||

| Listening | 0.34 | 6.70*** | |||

| Gender | 0.02 | 0.63 | |||

| Place of birth | 0.02 | 0.43 | |||

| Single-birth | ﹣0.01 | ﹣1.28 | |||

| Trails | Effect | Effect size | 95% confidence interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Lower | |||||

| Direct Effect | Empathy → Competence | 0.04 | 10.26% | ﹣0.09 | 0.16 |

| Intermediation Effect | Empathy → Interpersonal communication → competence | 0.15 | 38.46% | 0.08 | 0.23 |

| Empathy → Listening → competence | 0.13 | 33.33% | 0.08 | 0.19 | |

| Empathy → Interpersonal communication → Listening → competence | 0.07 | 17.95% | 0.03 | 0.11 | |

| Aggregate Intermediation Effect | 0.35 | 89.74% | 0.24 | 0.47 | |

| Total Effect | 0.39 | 100.00% | 0.25 | 0.53 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).