1. Introduction

Ecology is a discipline that seeks to understand why biological communities change over time [

1]. As global climates change, it is important to understand and to predict how ecosystems and ecosystem services will respond to those changes [

2]. As the severity of climate change increases, stream dynamics such as water temperature fluctuations [

3], habitat changes and availability [

4], and hydrological regime [

5], become increasingly unstable, unpredictable, and highly variable [

2]. Climate change, coupled with human activities that alter landscapes, can be drivers of change with the potential to negatively affect freshwater systems [

6]. Often, landscapes are converted for agriculture, urban development, roadways or other municipal operations [

7], and encroach on important floodplain features like riparian zones, and can have negative impacts on rivers [

8]. The alteration of riparian zones (e.g., deforestation, grass and prairie removal) can alter lotic temperature regimes [

9] and have deleterious effects on the natural structure and functioning of river ecosystems [

10].

Climate change and land alterations are well known to affect streams and rivers. However, landscape type (such as karst geology) can further influence the structure and functioning of river ecosystems [

11]. Karst landscapes have important hydrological influences on streams and rivers via groundwater exchange, providing biota with unique thermal refugia [

12]. In karst terrain, groundwater processes have important moderating effects, reducing overall stream temperature and providing the cooler thermal regimes [

12] needed by certain biota to complete their life histories [

13]. Surface springs in karstic regions are extremely important for their influence on flow and temperature [

14]. Springs can be variable in output volume and temperature depending on bedrock composition and complexity [

15], which can influence the variability of stream temperatures [

14]. Groundwater temperatures in karst landscapes can be governed by mean annual temperatures of the region in which those landscapes are located [

14]. As climate change increases, mean annual atmospheric temperatures are expected to increase, this can have the potential of elevating aquifer (shallow aquifers can be more susceptible to warming) and groundwater temperatures and potentially increasing stream peak temperatures [

16]. Consequently, the effects of increasing temperatures can act as a stressor and driver on biological communities, causing variability in populations [

17].

Globally, 15.2% of the land surface is covered by karst [

18]. Broken down, karst can be found in Europe (21.8%), North America (19.6%), Asia (18.6%), Africa (13.5%), Oceania (6.2%), and South America (4.3%) [

18]. Karst dominates the landscape in portions of the upper midwestern USA, one of several such locations in North America. This region also is characterized as a sensitive bio-ecoregion [

19], with streams exhibiting transitional, temperature-pattern stream networks supporting diverse communities. In this region, there is extensive dissolution and fracture of carbonate rock that accommodates large aquifers with extensive groundwater-surface water connectivity via springs and sinks. These springs stabilize flows and temperatures of receiving streams [

15]. However, these conduit-type groundwater flow paths also produce rapid streamflow responses to rainfall, which can negatively alter hydrology and stream conditions [

14].

Thermal refugia can be limiting to species distribution and composition [

20,

21], yet the variability of stream temperatures is known to be governed by climate change [

22], groundwater [

12], and changes to the riparian corridor [

23] which can create unique temperature-driven stream patterns and communities. Transitional temperature-pattern streams are characterized by varying assemblages of warmwater, coolwater, and coldwater fish species occupying specific thermal habitats in karst regions [

2,

15]. As stream temperatures warm, certain species may become exposed to the dangers of shifting thermal regimes. Salmonids are of major concern, as they inhabit cold, groundwater-fed streams. Trout are generally sensitive fish with specific habitat and thermal requirements [

24], have low thermal thresholds, and have high cultural, and recreational value [

25].

Understanding the ecological effects of thermal inputs and changes in stream temperatures is paramount to predicting distributions of various species in sensitive regions. Karst regions are complex and thus present challenges toward this understanding, especially when these landscapes also are dominated by agriculture [

26]. Stream temperatures can be influenced by atmospheric temperatures [

27] and agricultural land modifications (forest removal, riparian removal) [

6], but how biological communities respond to those changing temperatures is a knowledge gap requiring more research [

12], especially in transitional temperature-pattern stream networks. In the present study, our objectives were to determine what effects thermal conditions may have on the distribution of different fish communities in a transitional temperature-pattern catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA. Specifically, we examined fish communities and condition of trout within the transitional sections of streams along a longitudinal thermal gradient influenced by springs. We hypothesized that spring inputs would support the theory of the transitional temperature pattern and that fish communities would change along that thermal gradient. We hypothesize there will be important correlations in fish community distribution and trout condition.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

Karst environments are dominated by soluble sandstone, limestone, dolomite, and shale [

28]. Karst regions are among the most diverse hydrogeological environments, providing both valuable drinking water from aquifers and cold groundwater inputs to streams and rivers, as well as creating unique landscapes with sensitive biodiversity [

18]. Forming 200 million years ago (mya) from deposited material under shallow seas, accumulations cemented together over time, forming layers of rock that are now the bluffs in southeastern Minnesota, southwestern Wisconsin, northeastern Iowa, and northwestern Illinois, collectively referred to as the Driftless Area (DA) ecoregion. During the most recent glacial advance ~10,000 years ago, the DA was left untouched by ice. Glacial meltwaters carved surrounding bluffs and plateaus, forming Mississippi River tributaries within an area > 25,900 km

2, with > 27,000 km of fishable trout streams [

29].

Located in southeastern Minnesota, USA, the Whitewater River is an agricultural catchment within the DA supporting a coldwater fishery. Home to native brook trout (

Salvelinus fontinalis), introduced brown trout (

Salmo trutta), stocked rainbow trout (

Oncorhynchus mykiss), and slimy and mottled sculpin (family Cottidae;

Uranidea cognata, Uranidea bairdii, respectively), sensitive species found throughout the catchment typically in coldwater sections. This catchment is comprised of three sub-catchments, the North, Middle, and South forks with >189 km of fishable, coldwater streams [

6]. Together, the forks drain 829.6 km

2 of agricultural land and mixed deciduous hardwood forest, across three counties (Olmsted, Winona, and Wabasha), joining together near Elba, Minnesota, and ultimately draining into the Mississippi River at Weaver, Minnesota, USA.

Each fork of the Whitewater River catchment, North, Middle, and South, are temperature-transitional sub-catchments. They are arranged from headwaters (HW), middle sections (MS), and lower sections (LS); coolwater, warmwater, and coldwater, respectively. A previous study [

30] characterized each fork by section based on physical habitat, benthic macroinvertebrate index of biotic integrity, and fish index of biotic integrity. Our designations can be supported by stream management plans obtained from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Fisheries section in Lanesboro, Minnesota, USA. Each fork has specific designations for coldwater sections, in river miles, beginning at the confluence of each stream, going upstream with lower 24.2 (North Fork), 23.3 (Middle Fork), and 20.8 (South Fork) of each fork are designated as coldwater. Crow Spring drains into the Middle Fork downstream of the coldwater cutoff and is technically the coldwater section of the Middle.

2.2. Stream Surveys

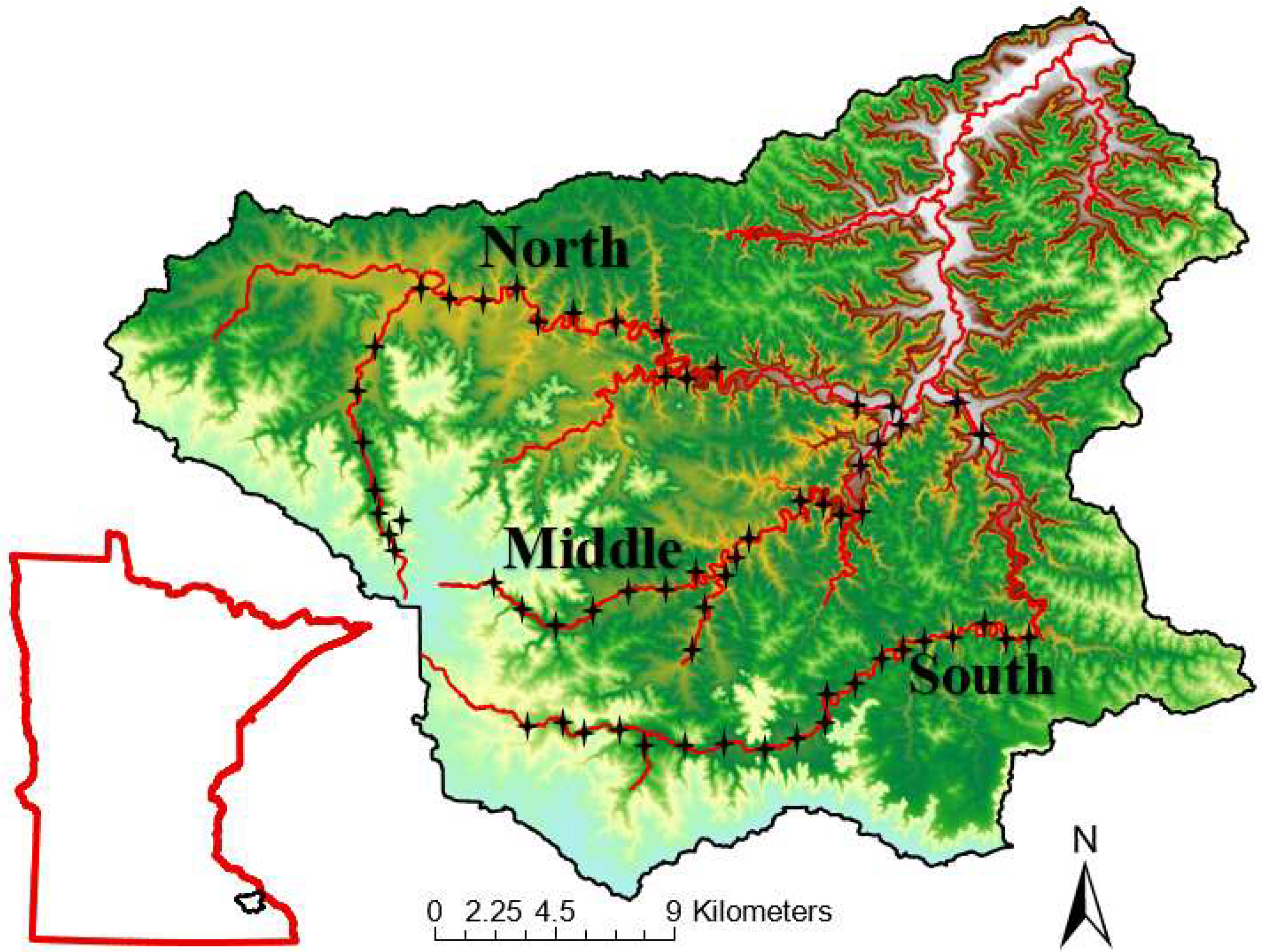

During late spring to early autumn (May – October) in 2018 and 2019, we conducted fish surveys at 61 sites within the three forks of the Whitewater River catchment (North = 21, Middle = 19, South = 21;

Figure 1). Surveys were conducted at sites along each of the three river forks and within main tributaries to each fork. Sites included locations both on private lands (with landowner consent) and public lands (e.g., state parks and wildlife management areas). We attempted to select study sites every 1.5 km along each fork and main tributaries. However, some areas were inaccessible due to terrain and lack of roadways within all forks; there were spatial gaps between sites, especially along the lower reaches of each fork.

Fish assessments were completed to estimate abundance (trout and non-trout), Simpsons Diversity Index (SDI), fishing effort (CPUE), and relative weight (Wr, trout only, a measure of fish condition) within 150-m reaches at each stream sites across all forks. A single-pass electrofishing method (downstream to upstream, Smith-Root LR-24 electrofisher, two or three netters) was used to survey the fish community. Fish captured were identified, counted, only trout were weighed (g) and measured (total length, mm), all fish were returned to the stream after capture, except for a few specimens retained for later identification. We examined length/weight data for trout only, to investigate trout condition and potential influences. We used condition as a descriptor for relative weight (Wr) to describe trout as “thin” (< 89%), “normal” (90 – 100 %), and “robust” (> 100%).

2.3. Data Analyses

Data were analyzed using Program R version 3.5.1 (R Core Team 2018), and Microsoft Excel. Basic descriptive statistics were used to describe stream variables and catch statistic data (i.e., means, and standard deviation). Inferential statistical methods following [

31] (e.g., analysis of variance [ANOVA], Chi-square goodness of fit analysis, two-sample t-test) were used as appropriate to test for differences across various measurements among study reaches.

We used Simpson’s Diversity Index [

32] to describe diversity of fish among forks. SDI is a measure of diversity which considers the number of species present and the relative abundance of each species. To calculate SDI using catch statistics, we used the following formula

where

n is the number of individuals of a single species,

N is the number of individuals in the total sample. The resulting values lie between 0 (low diversity) and 1 (high diversity).

To calculate trout abundance, we used number of fish caught divided by reach length, then multiplied by 1609 km. For CPUE estimates, we used fish/min to describe catch rates from electrofishing.

To assess whether certain factors varied longitudinally, a linear regression model-least squares approach (lm) was used with river.km as the predictor and diversity, CPUE, and condition, separately, as a response. Linear regression is used to estimate the linear relationship between a response (dependent) and predictor (independent) variables.

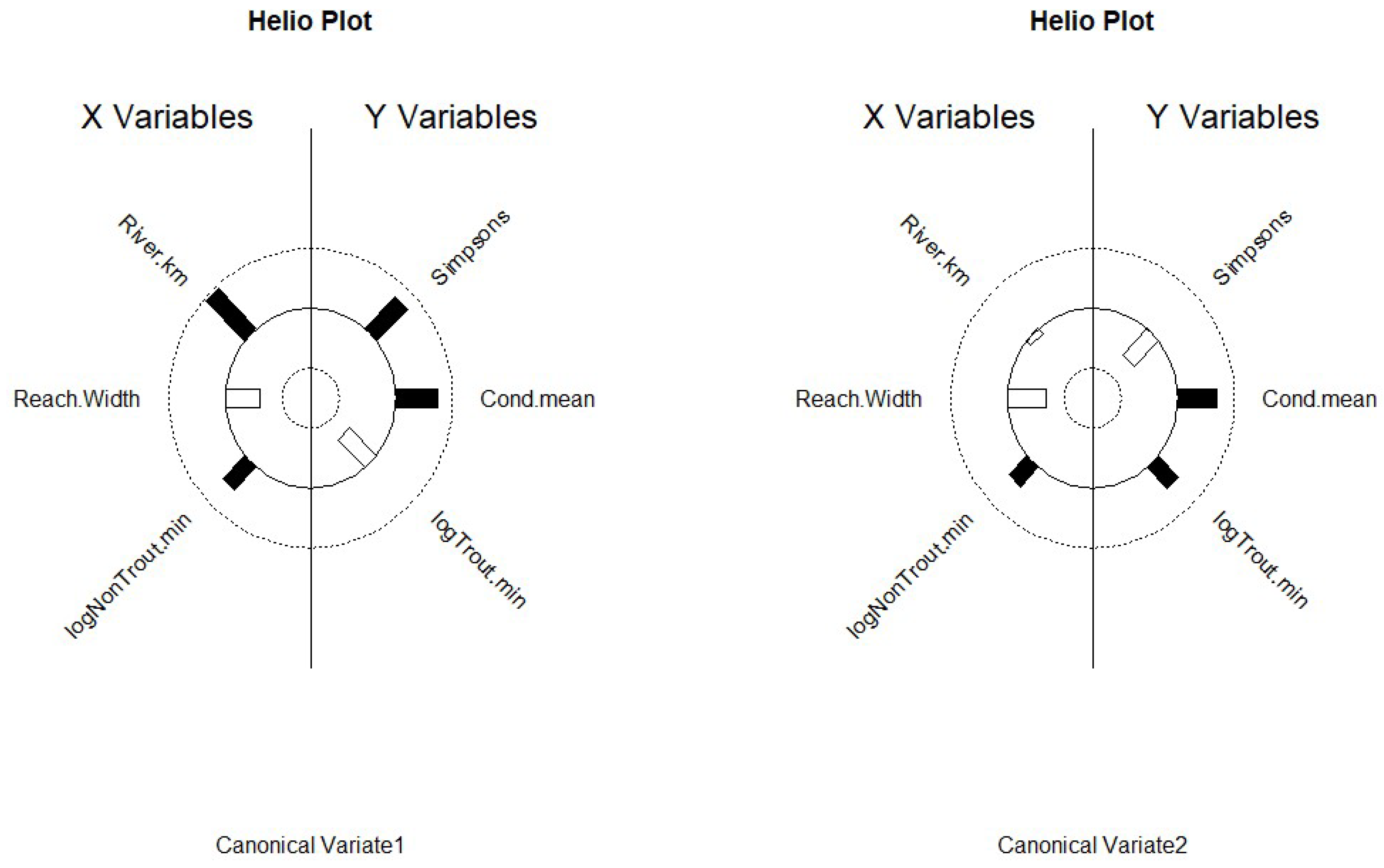

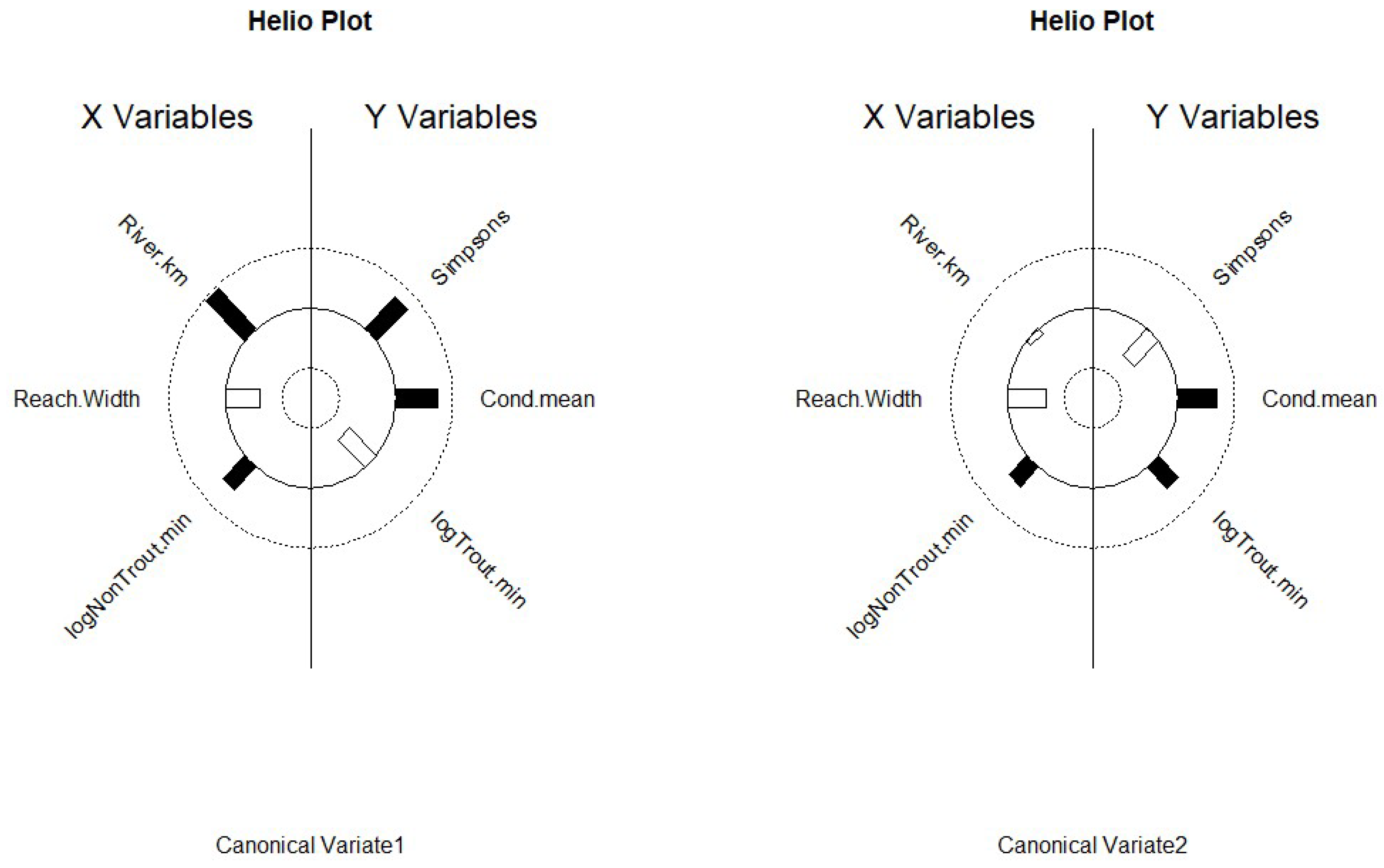

Canonical Correlations (CanCorr) [

33] was used to explore multivariate relationships among stream variables and catch statistics. CanCorr finds separate linear combinations for the stream and catch multivariate data sets that have the maximum correlation with each other; these are denoted as the first canonical variate pair. Subsequent pairs of canonical variates (i.e., second, third, and so on) are independent of all previous canonical variates and show relationships among variables after accounting for factors driving all previous canonical variates. However, correlation strength decreases for subsequent canonical variates, so approximate F-tests [

33] were used to test for non-zero correlations between canonical variate pairs. Heliographs [

34] of the correlations between all significant canonical variates and the stream variables and catch statistics were used to portray multivariate relationships among stream characteristics.

Figure 1.

Whitewater River catchment located in southeastern Minnesota, USA. Displayed are the North (n = 21), Middle (n = 19), and South Forks (n = 21) with main tributaries. The four-point stars are study sites along each fork. This catchment is dominated by agricultural activities with >70% of the once forested land converted.

Figure 1.

Whitewater River catchment located in southeastern Minnesota, USA. Displayed are the North (n = 21), Middle (n = 19), and South Forks (n = 21) with main tributaries. The four-point stars are study sites along each fork. This catchment is dominated by agricultural activities with >70% of the once forested land converted.

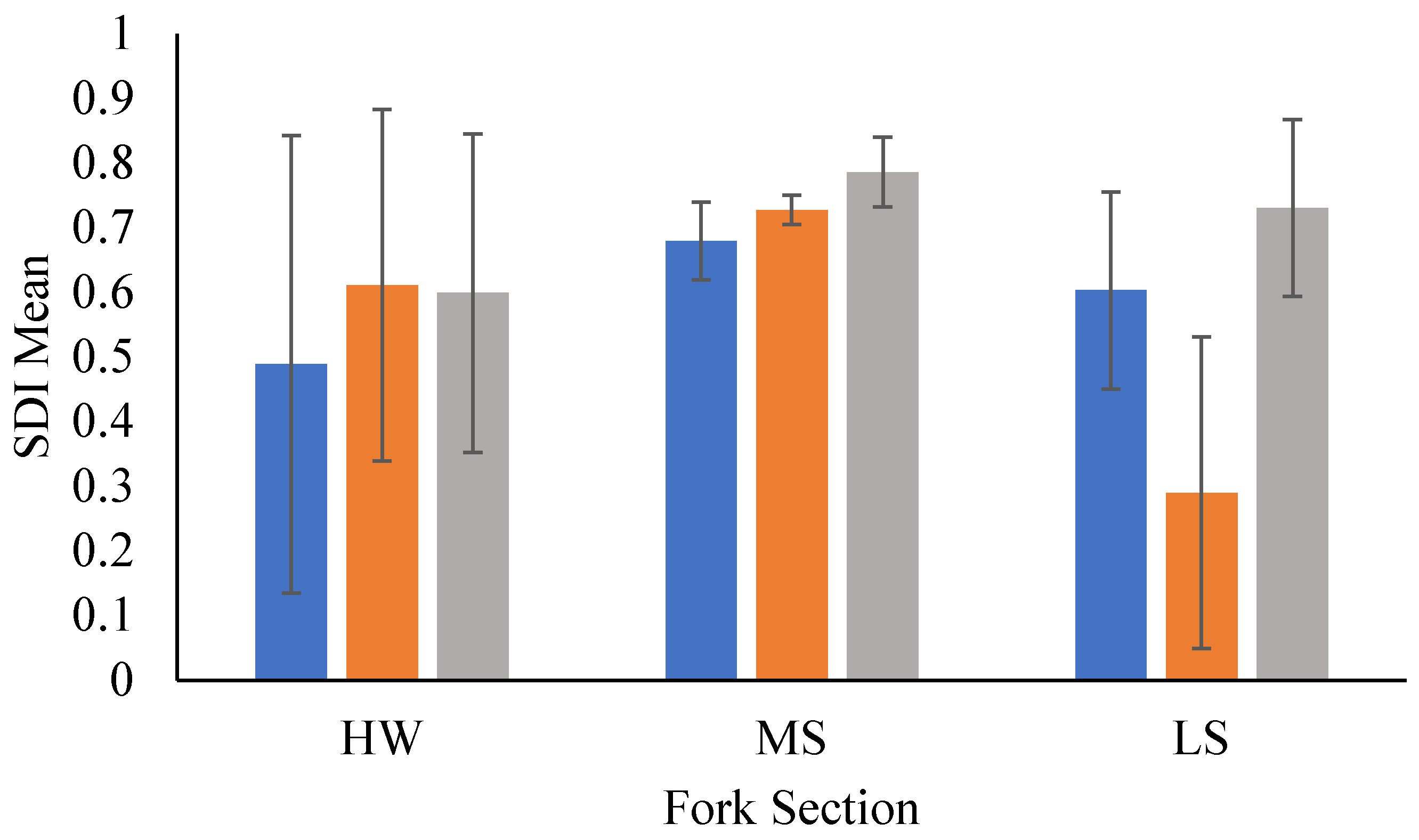

Figure 4.

Mean Simpson Diversity Index values are displayed with ± one standard deviation error bars. Data are arranged by section for each fork from the HW to LS’s sections. Data collected during late spring and early fall in 2018 and 2019 in the Whitewater River catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

Figure 4.

Mean Simpson Diversity Index values are displayed with ± one standard deviation error bars. Data are arranged by section for each fork from the HW to LS’s sections. Data collected during late spring and early fall in 2018 and 2019 in the Whitewater River catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

Figure 5.

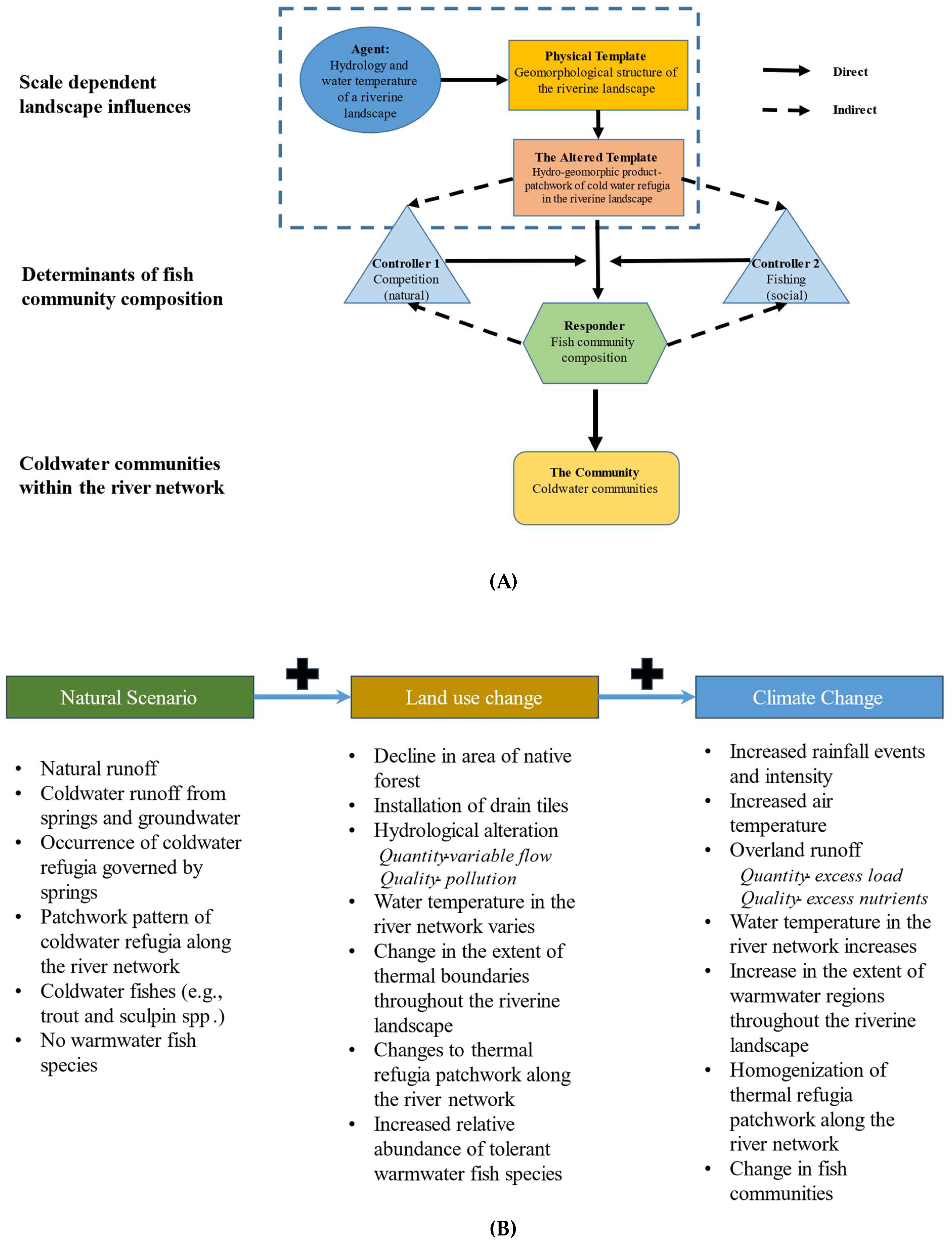

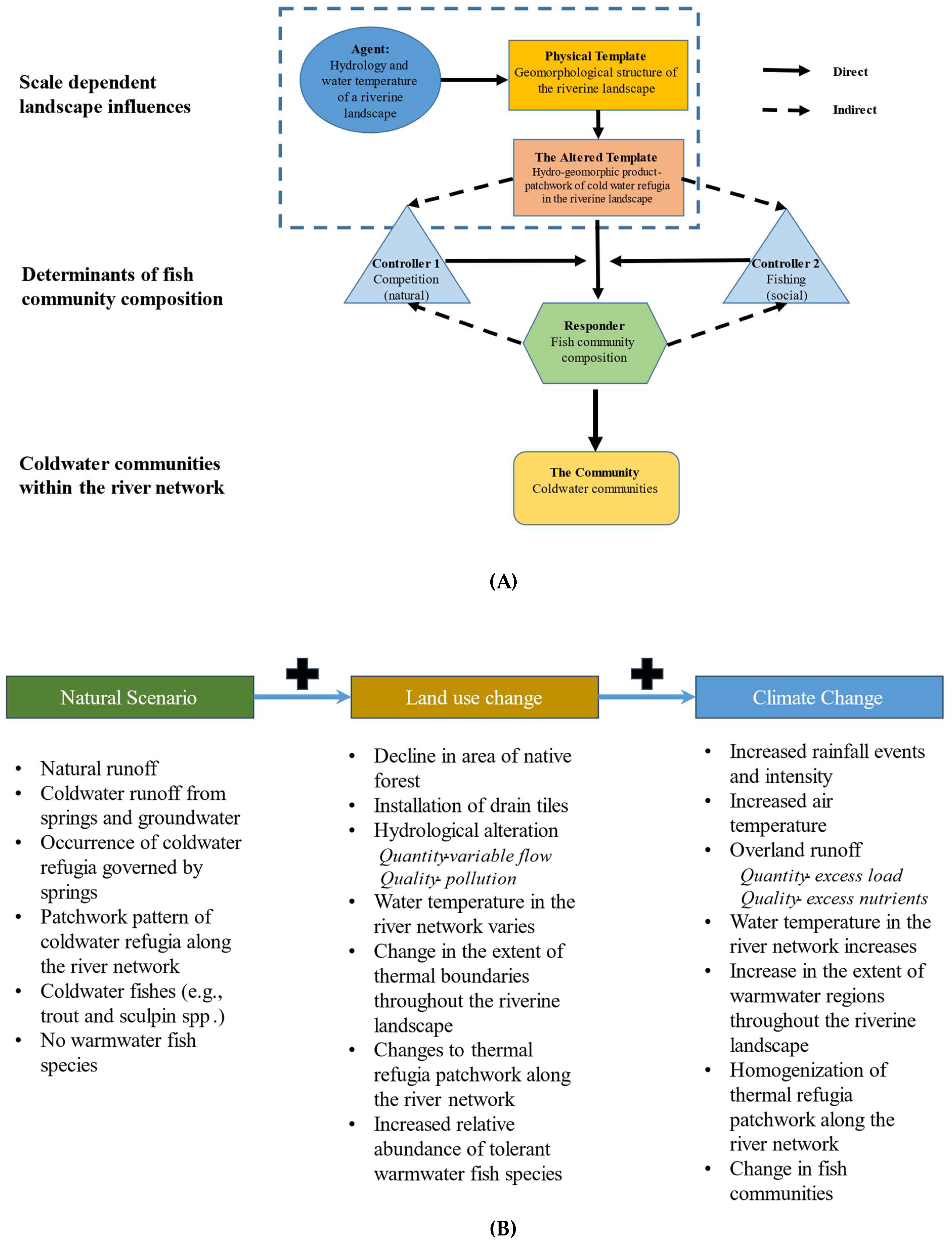

Heliographs of the first two canonical variates from Canonical Correlation modeling displaying the correlation between canonical variates and associated stream variables (X) and catch statistics (Y). Length of bars are proportional to the absolute strength of the correlation; solid black vars are positive correlations, while clear bars show negative correlations plotted on polar coordinates. Data collected during late spring and early fall in 2018 and 2019 in the Whitewater River catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA. Figure A. Conceptual social-ecological model. This describes the agents that shape the physical template of rivers, the altered template, those that control composition, and how communities respond to those agents/drivers of change. Developed for coldwater communities in southeastern Minnesota, USA. Figure B. Flow chain model depicting how rivers may respond to changes. Under a natural setting with natural conditions, some disturbance alters the natural setting, land use; from that interaction, a new set of conditions emerges. Then climate change coupled with land use may produce another set of conditions in river ecosystems. This model can be used to predict potential responses to change or drivers of change in river ecosystems. Flow chain model was developed for trout streams in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

Figure 5.

Heliographs of the first two canonical variates from Canonical Correlation modeling displaying the correlation between canonical variates and associated stream variables (X) and catch statistics (Y). Length of bars are proportional to the absolute strength of the correlation; solid black vars are positive correlations, while clear bars show negative correlations plotted on polar coordinates. Data collected during late spring and early fall in 2018 and 2019 in the Whitewater River catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA. Figure A. Conceptual social-ecological model. This describes the agents that shape the physical template of rivers, the altered template, those that control composition, and how communities respond to those agents/drivers of change. Developed for coldwater communities in southeastern Minnesota, USA. Figure B. Flow chain model depicting how rivers may respond to changes. Under a natural setting with natural conditions, some disturbance alters the natural setting, land use; from that interaction, a new set of conditions emerges. Then climate change coupled with land use may produce another set of conditions in river ecosystems. This model can be used to predict potential responses to change or drivers of change in river ecosystems. Flow chain model was developed for trout streams in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

Table 1.

Spring data showing distribution and influence of inputs for both flow in liters/sec (Q) and mean temperature (x-bar). Abbreviations are North Fork (NF), Middle Fork (MF), South Fork (SF), headwaters (HW), middle sections (MS), and lower sections (LS) of each fork. Means (x-bar) for variable are shown with + one standard deviation. Chi-square results testing for differences distribution among forks and differences in pattern among sections. Asterisks denote significance and number of asterisks denote strength. Data collected from the Minnesota Spring Inventory website for spring located in the Whitewater catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA. .

Table 1.

Spring data showing distribution and influence of inputs for both flow in liters/sec (Q) and mean temperature (x-bar). Abbreviations are North Fork (NF), Middle Fork (MF), South Fork (SF), headwaters (HW), middle sections (MS), and lower sections (LS) of each fork. Means (x-bar) for variable are shown with + one standard deviation. Chi-square results testing for differences distribution among forks and differences in pattern among sections. Asterisks denote significance and number of asterisks denote strength. Data collected from the Minnesota Spring Inventory website for spring located in the Whitewater catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA. .

| |

|

Springs |

|

Testing |

| Fork |

|

x̄ |

Q |

n |

|

X2

|

DF |

P |

| North |

|

9.2 (3.04) |

459 |

26 |

|

|

|

|

| Middle |

|

9.6 (3.10) |

3,978 |

30 |

|

9.3 |

2 |

0.05* |

| South |

|

9 (3.00) |

1,854 |

19 |

|

|

|

|

| Section |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NF- HW |

|

9.9 |

28 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

| NF- MS |

|

|

|

1 |

|

41.1 |

2 |

< 0.0001** |

| NF- LS |

|

9.2 |

431 |

24 |

|

|

|

|

| MF- HW |

|

8.9 |

184 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| MF- MS |

|

12.6 |

305 |

7 |

|

15.8 |

2 |

< 0.0001** |

| MF- LS |

|

8.7 |

3489 |

20 |

|

|

|

|

| SF- HW |

|

9.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SF- MS |

|

|

|

1 |

|

32.5 |

2 |

< 0.0001** |

| SF- LS |

|

9 |

1854 |

18 |

|

|

|

|

Table 2.

Results from linear model with diversity used as the response and river.km as the predictor. Shown are model estimate, standard error, r-square value, T and F statistic, and probability statistic. Asterisk denotes significant differences and strength. Data represented is for the three forks (North, Middle, South) of the Whitewater River located in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

Table 2.

Results from linear model with diversity used as the response and river.km as the predictor. Shown are model estimate, standard error, r-square value, T and F statistic, and probability statistic. Asterisk denotes significant differences and strength. Data represented is for the three forks (North, Middle, South) of the Whitewater River located in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

| Coefficient |

Estimate |

Std. Error |

T |

P |

| Middle Fork |

0.486 |

0.064 |

7.55 |

3.9e-10*** |

| North Fork |

0.151 |

0.077 |

1.96 |

0.05 |

| South Fork |

0.283 |

0.081 |

3.51 |

0.001*** |

| River.km |

-0.001 |

0.002 |

-0.499 |

0.62 |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Model |

R2

|

DF |

F |

P |

| lm |

0.16 |

3 and 57 |

4.72 |

0.005 |

Table 3.

Fish community SDI values obtained for each fork by section. Abbreviations are as follow, North Fork (NF), Middle Fork (MF), South Fork (SF), headwater (HW), middle section (MS), and lower section (LS). X-bar is the mean value for SDI. All values are 1-D. ANOVA results are shown with f-statistic and p-value. Asterisk denotes significant differences. Data represented is for the three forks (North, Middle, South) of the Whitewater River located in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

Table 3.

Fish community SDI values obtained for each fork by section. Abbreviations are as follow, North Fork (NF), Middle Fork (MF), South Fork (SF), headwater (HW), middle section (MS), and lower section (LS). X-bar is the mean value for SDI. All values are 1-D. ANOVA results are shown with f-statistic and p-value. Asterisk denotes significant differences. Data represented is for the three forks (North, Middle, South) of the Whitewater River located in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

| Fork |

x̄ |

F |

P |

| NF- HW |

0.49 (0.35) |

|

|

| NF- MS |

0.67 (0.05) |

1.52 |

0.245 |

| NF- LS |

0.60 (0.15) |

|

|

| MF- HW |

0.61 (0.27) |

|

|

| MF- MS |

0.72 (0.02) |

6.71 |

0.007* |

| MF- LS |

0.29 (0.24) |

|

|

| SF- HW |

0.59 (0.24) |

|

|

| SF- MS |

0.79 (0.05) |

3.35 |

0.05* |

| SF- LS |

0.73 (0.12) |

|

|

Table 4.

Mean (+ one standard deviation) CPUE (trout/min) and abundance (fish/km) of trout. Abbreviations are as follow: North Fork (NF), Middle Fork (MF), South Fork (SF), headwaters (HW), middle sections (MS), and lower sections (LS). ANOVA results are shown with f-statistic and p-value. Asterisk denotes significant differences. Data collected during late spring and early fall in 2018 and 2019 in the Whitewater River catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

Table 4.

Mean (+ one standard deviation) CPUE (trout/min) and abundance (fish/km) of trout. Abbreviations are as follow: North Fork (NF), Middle Fork (MF), South Fork (SF), headwaters (HW), middle sections (MS), and lower sections (LS). ANOVA results are shown with f-statistic and p-value. Asterisk denotes significant differences. Data collected during late spring and early fall in 2018 and 2019 in the Whitewater River catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

| Fork |

|

CPUE |

|

Abundance |

F |

P |

| NF - HW |

|

0.043 (0.07) |

|

32 (0) |

|

|

| NF - MS |

|

0.23 (0.15) |

|

82 (33.4) |

9.21563 |

0.00322* |

| NF - LS |

|

0.56 (0.24) |

|

193 (82.3) |

|

|

| MF - HW |

|

0.202 (0.21) |

|

67 (63.9) |

|

|

| MF - MS |

|

0.62 (0.70) |

|

166 (204) |

3.19866 |

0.06966 |

| MF - LS |

|

1.30 (0.96) |

|

338 (216) |

|

|

| SF - HW |

|

0.01 (0.01) |

|

11 (0) |

|

|

| SF - MS |

|

0.23 (0.15) |

|

65 (34) |

16.5381 |

0.00016* |

| SF - LS |

|

0.73 (0.15) |

|

234 (97) |

|

|

| Model |

F |

DF |

P |

|

|

|

| lm |

14.72 |

5 and 55 |

3.75e-09*** |

|

|

|

Table 5.

Linear model testing of trout condition. Estimate value is the model response, standard error, t-statistic of testing, and the probability statistic. Model outputs are adjusted r-square, degrees of freedom, F statistic, and model p-value. Asterisks denote significance and strength. Data collected during late spring and early fall in 2018 and 2019 in the Whitewater River catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

Table 5.

Linear model testing of trout condition. Estimate value is the model response, standard error, t-statistic of testing, and the probability statistic. Model outputs are adjusted r-square, degrees of freedom, F statistic, and model p-value. Asterisks denote significance and strength. Data collected during late spring and early fall in 2018 and 2019 in the Whitewater River catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

| Fork |

Estimate |

Std. Error |

T |

P |

| Middle |

83.9 |

2.53 |

33.14 |

2e-16 *** |

| North |

-7.66 |

2.88 |

-2.65 |

0.0121 * |

| South |

-11.2 |

3.48 |

-3.21 |

0.0029 ** |

| River.km |

0.5 |

0.09 |

5.03 |

1.69e-05 *** |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Model |

R2

|

DF |

F |

P |

| Lm |

0.38 |

3 and 33 |

8.303 |

0.0003 |

Table 6.

Mean (+ one standard deviation) trout condition (relative weight, Wr) within sections of each fork. Abbreviations are as follow: North Fork (NF), Middle Fork (MF), South Fork (SF), headwaters (HW), middle sections (MS), and lower sections (LS). Also shown are ANOVA results with f and p-value. Asterisk denotes significant differences. Data collected during late spring and early fall in 2018 and 2019 in the Whitewater River catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

Table 6.

Mean (+ one standard deviation) trout condition (relative weight, Wr) within sections of each fork. Abbreviations are as follow: North Fork (NF), Middle Fork (MF), South Fork (SF), headwaters (HW), middle sections (MS), and lower sections (LS). Also shown are ANOVA results with f and p-value. Asterisk denotes significant differences. Data collected during late spring and early fall in 2018 and 2019 in the Whitewater River catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

| Fork |

Wr |

F |

P |

| NF-HW |

110 (0.90) |

|

|

| NF-MS |

89 (7.41) |

11.2301 |

0.00277* |

| NF-LS |

85 (3.97) |

|

|

| MF-HW |

93 (5.50) |

|

|

| MF-MS |

96 (6.31) |

1.04063 |

0.38556 |

| MF-LS |

91 (5.90) |

|

|

| SF-HW |

118 (0) |

|

|

| SF-MS |

90 (6.32) |

10.0172 |

0.00883* |

| SF-LS |

86 (5.64) |

|

|

Table 7.

Canonical variates produced by modeling with stream (X) and catch statistic variables (Y) using Canonical Correlations. Results show correlation strength (Corr) between the variate pair, approximate F-test statistics, and p-values for tests of non-zero correlations. Data collected during late spring and early fall in 2018 and 2019 in the Whitewater River catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

Table 7.

Canonical variates produced by modeling with stream (X) and catch statistic variables (Y) using Canonical Correlations. Results show correlation strength (Corr) between the variate pair, approximate F-test statistics, and p-values for tests of non-zero correlations. Data collected during late spring and early fall in 2018 and 2019 in the Whitewater River catchment in southeastern Minnesota, USA.

| Variate |

Corr |

F |

P |

| 1 |

0.764 |

5.45 |

9.63E-06 |

| 2 |

0.510 |

2.97 |

0.026 |

| 3 |

0.196 |

1.32 |

0.259 |