Submitted:

20 June 2024

Posted:

21 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

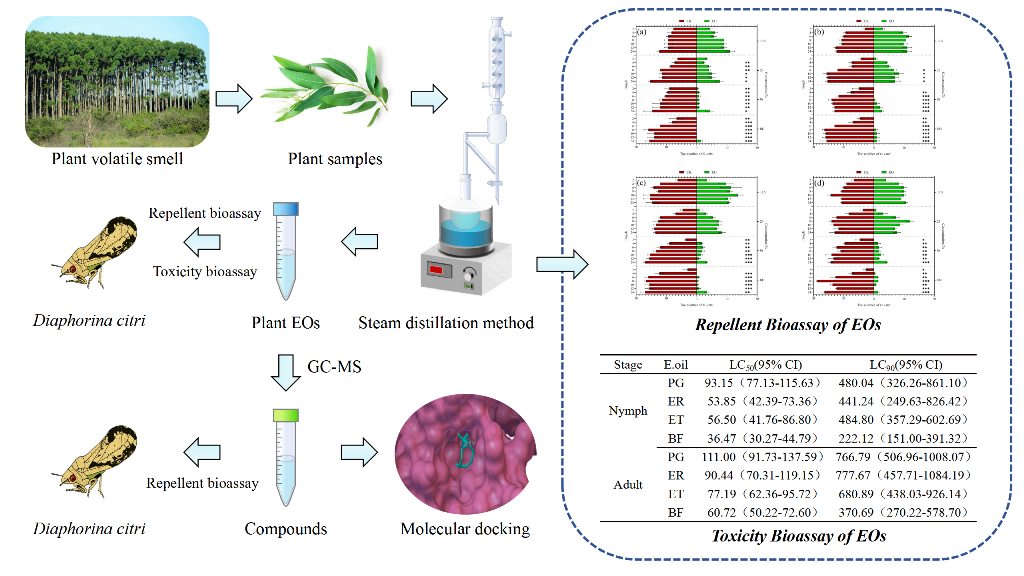

2. Result

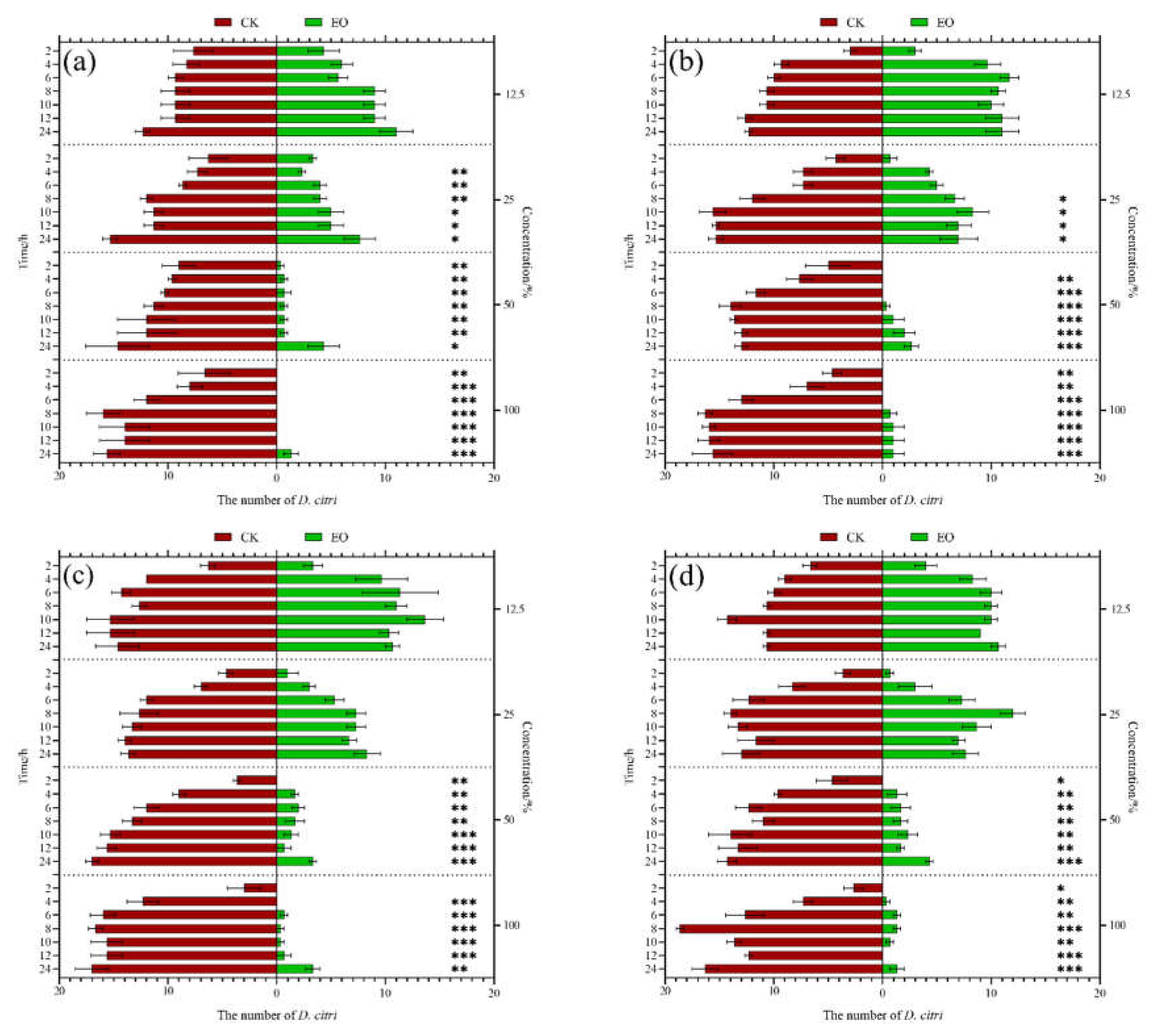

2.1. Repellent Bioassay of Eos

2.2. Toxicity Bioassay

2.3. Chemical Analysis of the EOs

2.4. Repellent Bioassay of Compounds

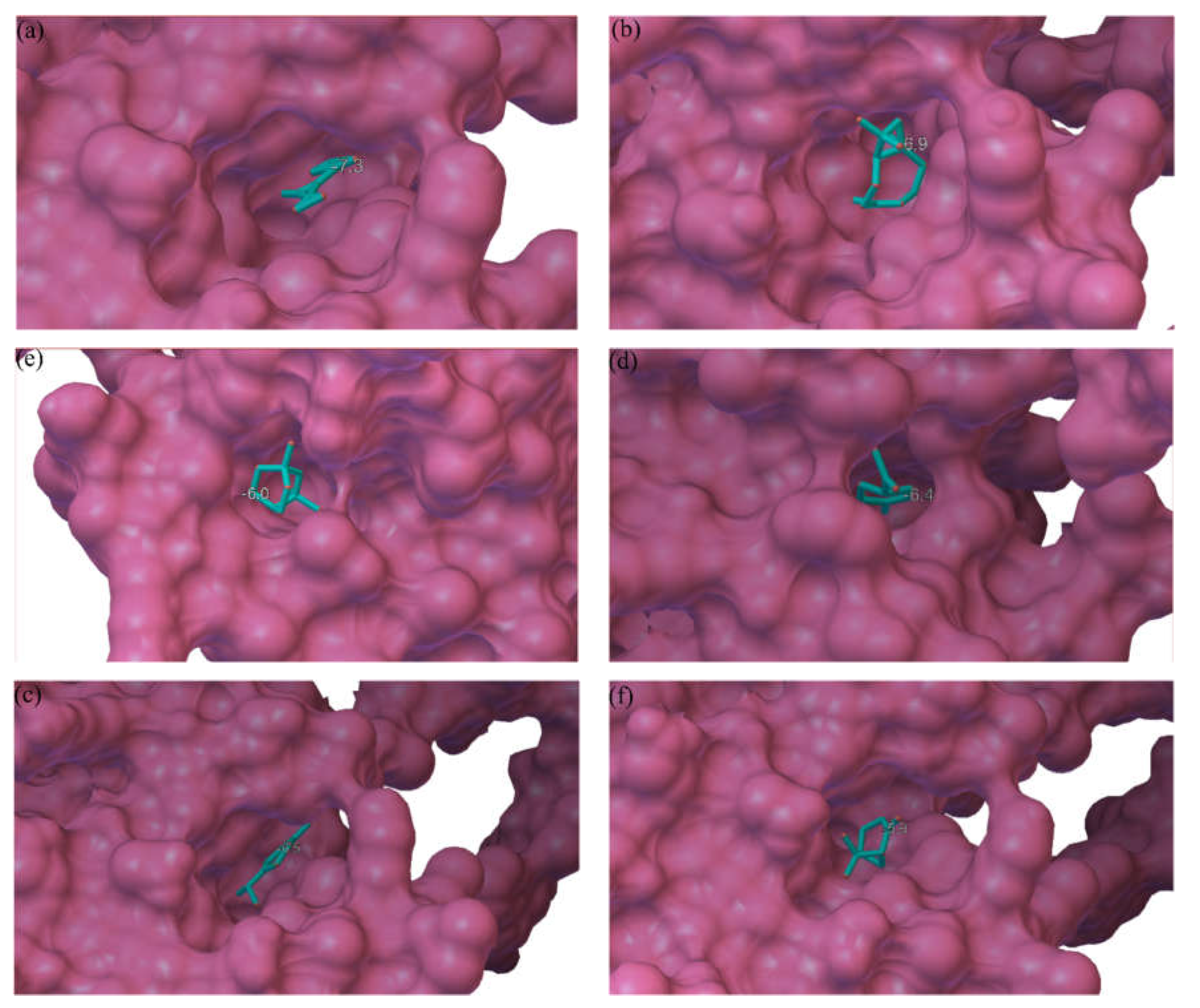

2.5. Molecular Docking

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant and Insect Materials

4.1.1. Plant Materials

4.1.2. Insect Materials

4.2. Extraction of the EOs

4.3. Repellent Bioassay of EOs

4.4. Toxicity Bioassay

4.5. Composition analysis of the EOs by GC-MS

4.6. Repellent Bioassay of Compounds

4.7. Molecular Modeling and Docking

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Bové, J. M. HUANGLONGBING: A DESTRUCTIVE, NEWLY-EMERGING, CENTURY-OLD DISEASE OF CITRUS. Journal of Plant Pathology. 2006, 88, 7–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, S.; Lewis-Rosenblum, H.; Pelz-Stelinski, K.; Stelinski, L. L. Incidence of Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus Infection in Abandoned Citrus Occurring in Proximity to Commercially Managed Groves. Journal of Economic Entomology 2010, 103, 1972–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassanezi, R. B.; Montesino, L. H.; Stuchi, E. S. Effects of huanglongbing on fruit quality of sweet orange cultivars in Brazil. European Journal of Plant Pathology. 2009, 125, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassanezi, R. B.; Belasque, J.; Montesino, L. H. Frequency of symptomatic trees removal in small citrus blocks on citrus huanglongbing epidemics. Crop Protection. 2013, 52, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, B. D.; B. J., R. Chemical control of the Asian citrus psyllid and of huanglongbing disease in citrus. Pest management science. 2015, 71, 808–823. [Google Scholar]

- Muyesaier, T.; Huada, D. R.; Li, W.; Jia, L.; Ross, S.; Des, C.; Cordia, C.; Tri, P. D. Agriculture Development, Pesticide Application and Its Impact on the Environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 1112. [Google Scholar]

- Siddharth, T.; R. S, R. M. E.; S. L., L. Insecticide resistance in field populations of Asian citrus psyllid in Florida. Pest management science 2011, 67, 1258–1268. [Google Scholar]

- B, K. L. H.; Julius, E.; Muhammad, H.; Jawwad, Q.; Philip, S. Monitoring for Insecticide Resistance in Asian Citrus Psyllid (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) Populations in Florida. Journal of economic entomology 2016, 109, 832–836. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. D.; Stelinski, L. L. Resistance Management for Asian Citrus Psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama, in Florida. Insects 2017, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saúl, P., M. A. M, F. J. I, C. J. M, V. Elisa, R.-A. Ángel, M. M. A, V. Javier and P. Samuel. Insecticide resistance of adults and nymphs of Asian citrus psyllid populations from Apatzingán Valley, Mexico. Pest management science. 2018, 74, 135-140.

- Cassie, S., B. M. A. and W. D. M. Enantiomeric Discrimination in Insects: The Role of OBPs and ORs. Insects. 2022, 13, 368-368.

- Gadenne, C.; Barrozo, R. B.; Anton, S. Plasticity in Insect Olfaction: To Smell or Not to Smell? Annual Review of Entomology 2016, 61, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, W. S. Odorant Reception in Insects: Roles of Receptors, Binding Proteins, and Degrading Enzymes. Annual Review of Entomology 2013, 58, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P, P., Z. J-J, B. L. P and C. M. Soluble proteins in insect chemical communication. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2006, 63, 1658-1676.

- Venthur, H. and J.-J. Zhou. Odorant Receptors and Odorant-Binding Proteins as Insect Pest Control Targets: A Comparative Analysis. Frontiers in Physiology. 2018, 9, 10.3389/fphys.2018.01163.

- Zhou, J. J., F. G. Vieira, X. L. He, C. Smadja, R. Liu, J. Rozas and L. M. Field. Genome annotation and comparative analyses of the odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. (Special Issue: The aphid genome.). Insect Molecular Biology. 2010, 19, 113-122.

- Ming, H. and H. Peng. Molecular characterization, expression profiling, and binding properties of odorant binding protein genes in the whitebacked planthopper, Sogatella furcifera. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Part B, Biochemistry & molecular biology. 2014, 174, 1-8.

- JinBu, L., Y. MaoZhu, Y. WeiChen, M. Sai, D. Youssef, L. XingZhou and Z. XiuYun. Genome-wide analysis of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in the sweet potato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci. Insect science. 2019, 26, 620-634.

- Wu, Z., H. Zhang, S. Bin, L. Chen, Q. Han and J. Lin. Antennal and Abdominal Transcriptomes Reveal Chemosensory Genes in the Asian Citrus Psyllid, Diaphorina citri. PLoS ONE. 2017, 11, e0159372.

- Machado, F. P., D. Folly, J. J. S. Enriquez, C. B. Mello, R. Esteves, R. S. Araújo, P. F. Toledo, J. G. Mantilla-Afanador, M. G. Santos and E. E. Oliveira. Nanoemulsion of Ocotea indecora (Shott) Mez essential oil: Larvicidal effects against Aedes aegypti. Industrial Crops and Products. 2023, 192, 116031.

- Appel, A. G., M. J. Gehret and M. J. Tanley. Repellency and Toxicity of Mint Oil Granules to Red Imported Fire Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of Economic Entomology. 2004, 575-580.

- Jemberie, W., A. Tadie, A. Enyew, A. Debebe and N. Raja. Repellent activity of plant essential oil extracts against malaria vector Anopheles arabiensis Patton (Diptera: Culicidae). ENTOMON. 2020, 41, 91-98.

- Shah, F. M.; Razaq, M.; Ali, Q.; Ali, A.; Shad, S. A.; Aslam, M.; Hardy, I. C. W. Action threshold development in cabbage pest management using synthetic and botanical insecticides. Entomologia Generalis. 2019, 40, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S. F., R. Muhammad, A. Abid, H. Peng and C. Julian. Comparative role of neem seed extract, moringa leaf extract and imidacloprid in the management of wheat aphids in relation to yield losses in Pakistan. PloS one. 2017, 12, e0184639.

- Rehman, J. U., A. Ali and I. A. Khan. Plant based products: Use and development as repellents against mosquitoes: A review. Fitoterapia. 2014, 95, 65-74.

- George, D. R., R. D. Finn, K. M. Graham and O. A. E. Sparagano. Present and future potential of plant-derived products to control arthropods of veterinary and medical significance. Parasites & Vectors. 2014, 7. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J. A. A., D. G. Hall, T. R. Gottwald, M. S. Andrade, W. Maldonado, R. T. Alessandro, S. L. Lapointe, E. C. Andrade and M. A. Machado. Repellency of selected Psidium guajava cultivars to the Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri. Crop Protection. 2016, 84, 14-20.

- Clovel, P., A. Rowda, F. M. N. Deye and M. Xavier. Repellency of volatiles from Martinique island guava varieties against Asian citrus psyllids. Arthropod-Plant Interactions. 2022, 16, 341-348.

- Zaka, S. M., X. N. Zeng, P. Holford and G. A. C. Beattie. Repellent effect of guava leaf volatiles on settlement of adults of citrus psylla, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama, on citrus. Insect Science. 2010, 17, 39-45.

- Uzochukwu, O. I., O. E. Sunday, E. W. C. Favour, N. J. Chinedum and E. T. P. Chidike. Overhauling the ecotoxicological impact of synthetic pesticides using plants’ natural products: a focus on Zanthoxylum metabolites. Environmental science and pollution research international. 2023, 30, 67997-68021.

- Song, X. B.; Cui, Y. P.; Peng, A. T.; Ling, J. F.; Chen, X. First report of brown spot disease in Psidium guajava caused by Alternaria tenuissima in China. Journal of Plant Pathology. 2020, 102, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., S. Rutherford, J. S. H. Wan, J. Liu, J. Zhang, M. R. Afzal, D. Du and M. Rossetto. Variation in Leaf Functional and Plant Defense Traits of IntroducedEucalyptusSpecies across Environmental Gradients in Their New Range in Southern China. Forests. 2023, 14.

- Xianliang, Z., H. Jiayue, Z. Changpin, W. Qijie, C. Shengkan, B. David and L. Fagen. Xylem Transcriptome Analysis in Contrasting Wood Phenotypes of Eucalyptus urophylla × tereticornis Hybrids. Forests. 2022, 13, 1102-1102.

- Chen, Y., X. a. Cai, Y. Zhang, X. Rao and S. Fu. Dynamics of Understory Shrub Biomass in Six Young Plantations of Southern Subtropical China. Forests. 2017, 8, 419.

- Ivo, E. W., S. A. Caroline, V. H. X. Linhares, A. Berta, P. Leandro and M. M. Pedreira. Push-pull and kill strategy for Diaphorina citri control in citrus orchards. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. 2023, 171, 287-299.

- Gottwald, T. R., D. G. Hall, A. B. Kriss, E. J. Salinas, P. E. Parker, G. A. C. Beattie and M. C. Nguyen. Orchard and nursery dynamics of the effect of interplanting citrus with guava for huanglongbing, vector, and disease management. Crop Protection. 2014, 64, 93-103.

- Zaka, S. M., X.-N. Zeng, P. Holford and G. A. C. Beattie. Repellent effect of guava leaf volatiles on settlement of adults of citrus psylla, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama, on citrus. Insect Science. 2010, 17, 39-45. [CrossRef]

- Alquezar, B., H. X. Linhares Volpe, R. F. Magnani, M. P. de Miranda, M. A. Santos, N. A. Wulff, J. M. Simoes Bento, J. R. Postali Parra, H. Bouwmeester and L. Pena. β-caryophyllene emitted from a transgenic Arabidopsis or chemical dispenser repels Diaphorina citri, vector of Candidatus Liberibacters. Scientific Reports. 2017, 7, 10.1038/s41598-017-06119-w.

- S., L. S., L. S. C. T. and B. G. A. Charles. Effect of Horticultural Mineral Oil on Huanglongbing Transmission by Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) Population in a Commercial Citrus Orchard in Sarawak, Malaysia, Northern Borneo. Insects. 2021, 12, 772-772.

- Ibarra-Cortés, K. H., H. González-Hernández and A. W. Guzmán-Franco. Susceptibility of nymphs and adults of Diaphorina citri to the entomophathogenic fungus Hirsutella citriformis. Biocontrol Science and Technology. 2017, 27, 433-438.

- Liu, X.-Q., H.-B. Jiang, J.-Y. Fan, T.-Y. Liu, L.-W. Meng, Y. Liu, H.-Z. Yu, W. Dou and J.-J. Wang. An odorant-binding protein of Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri, participates in the response of host plant volatiles. Pest Management Science. 2021, 77, 3068-3079. 10.1002/ps.6352.

- Gao, S., Z. Huo, M. Guo, K. Zhang, Y. Zhang, X. Wang and R. Li. Contact toxicity of eucalyptol and RNA sequencing of Tribolium castaneum after exposure to eucalyptol. Entomological Research. 2023, 53, 226-237. 10.1111/1748-5967.12659.

- S, V. T. d., D. R. F, V. A. C. d. S, M. R. F. A and A. V. M. Evaluation of Chilean Boldo Essential Oil as a Natural Insecticide Against Chrysomya megacephala (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Journal of medical entomology. 2020, 57, 1364-1372.

- L, S. K., S. Kom, B. Noppawan and P. Somsak. Some ultrastructural superficial changes in house fly (Diptera: Muscidae) and blow fly (Diptera: Calliphoridae) larvae induced by eucalyptol oil. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de Sao Paulo. 2004, 46, 263-267.

- Mohd, I. M. N., H. Yazmin, R. N. F. Che, A. M. N. Mubin, Y. S. Keong, R. H. Sulaiman, M. M. Jaffri, M. N. Elyani, A. Rasedee and A. N. Banu. Physicochemical characterization, cytotoxic effect and toxicity evaluation of nanostructured lipid carrier loaded with eucalyptol. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies. 2021, 21, 254-254.

- Caldas, G. F. R., M. M. F. Limeira, A. V. Araújo, G. S. Albuquerque, J. d. C. Silva-Neto, T. G. d. Silva, J. H. Costa-Silva, I. R. A. d. Menezes, J. G. M. d. Costa and A. G. Wanderley. Repeated-doses and reproductive toxicity studies of the monoterpene 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) in Wistar rats. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2016, 97, 297-306.

- Eugenia Amoros, M., V. Pereira das Neves, F. Rivas, J. Buenahora, X. Martini, L. L. Stelinski and C. Rossini. Response of Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Liviidae) to volatiles characteristic of preferred citrus hosts. ARTHROPOD-PLANT INTERACTIONS. 2019, 13, 367-374. 10.1007/s11829-018-9651-8.

- Manoj, K., T. Maharishi, A. Ryszard, S. Vivek, N. M. Sneha, M. Chirag, S. Minnu, P. Uma, H. Muzaffar, S. Surinder, C. Sushil, P. R. Kumar, B. M. K. and S. Varsha. Guava (Psidium guajava L.) Leaves: Nutritional Composition, Phytochemical Profile, and Health-Promoting Bioactivities. Foods. 2021, 10, 752-752.

- Raj, M. S. A., S. Amalraj, S. Alarifi, M. G. Kalaskar, R. Chikhale, V. P. Santhi, S. Gurav and M. Ayyanar. Nutritional Composition, Mineral Profiling, In Vitro Antioxidant, Antibacterial and Enzyme Inhibitory Properties of Selected Indian Guava Cultivars Leaf Extract. Pharmaceuticals. 2023, 16.

- Katembo, K. D., L. Gauthier, M. J. Mate, D. Thomas, R. Mélissa, M. Adrien and B. Nils. Growth, Productivity, Biomass and Carbon Stock in Eucalyptus saligna and Grevillea robusta Plantations in North Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Forests. 2022, 13, 1508-1508.

| Stage | E.oil | n | Slope ± SEM | LC50 (95% CI) | LC90 (95% CI) | χ 2 | df |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nymph | PG | 90 | 1.80±0.20 | 93.15(77.13-115.63) | 480.04(326.26-861.10) | 1.90 | 3 |

| ER | 90 | 1.40±0.18 | 53.85(42.39-73.36) | 441.24(249.63-826.42) | 1.31 | 3 | |

| ET | 90 | 1.11±0.18 | 56.50(41.76-86.80) | 484.80(357.29-602.69) | 0.84 | 3 | |

| BF | 90 | 1.63±0.17 | 36.47(30.27-44.79) | 222.12(151.00-391.32) | 3.06 | 3 | |

| Adult | PG | 90 | 1.53±0.16 | 111.00(91.73-137.59) | 766.79(506.96-1008.07) | 1.83 | 3 |

| ER | 90 | 1.11±0.15 | 90.44(70.31-119.15) | 777.67(457.71-1084.19) | 0.79 | 3 | |

| ET | 90 | 1.36±0.15 | 77.19(62.36-95.72) | 680.89(438.03-926.14) | 0.23 | 3 | |

| BF | 90 | 1.63±0.16 | 60.72(50.22-72.60) | 370.69(270.22-578.70) | 0.12 | 3 |

| No. | Compounds | NIST RI | Relative abundance (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PG | ER | ET | BF | |||

| 1 | 4-Hexen-3-one | 855 | - | 0.51 | - | - |

| 2 | Dimethyl sulfone | 922 | - | 0.60 | 3.02 | - |

| 3 | Benzene, (1-methylethyl)- | 926.57 | - | - | 1.68 | - |

| 4 | Cyclobutanespiro-2’-bicyclo[1.1.0]butane-4’-spirocyClobutane | 930 | - | 1.10 | 5.85 | 0.68 |

| 5 | α-Pinene | 936.35 | - | 3.40 | 15.59 | 3.21 |

| 6 | Cyclopentene, 1-butyl- | 938 | - | - | 0.93 | - |

| 7 | Bicyclo (3.3.1)non-2-ene | 964 | - | - | 0.68 | - |

| 8 | 4-methyl-1- (1-methylethyl)-Bicyclo[3.1.0]hex-2-ene | 966 | - | - | 1.21 | - |

| 9 | Bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane, 4-methylene-1- (1-methylethyl)- | 972 | - | 0.45 | 1.62 | - |

| 10 | 2,6-Octadiene, 2,6-dimethyl- | 978 | - | 0.43 | 1.44 | - |

| 11 | β-Pinene | 979.71 | - | 1.81 | 6.25 | 0.70 |

| 12 | 1,7-Octadiene, 2-methyl-6-methylene- | 984 | - | 0.38 | 1.31 | - |

| 13 | DiSulfur compounds, ethyl 1-methylethyl | 985 | - | - | 0.58 | - |

| 14 | Pyridine, 3-propyl- | 986 | - | - | 0.73 | - |

| 15 | Benzene, (1-methylpropyl)- | 1001 | - | 0.37 | - | - |

| 16 | α-Phellandrene | 1006 | - | 12.20 | 0.77 | 0.55 |

| 17 | Terpilene | 1018.03 | - | - | - | - |

| 18 | 4-Hexen-1-ol, acetate | 1020 | - | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.63 |

| 19 | o-Cymene | 1022 | - | 10.70 | 4.13 | 13.62 |

| 20 | 4,6-Octadiyn-3-one, 2-methyl- | 1023 | 0.69 | - | - | - |

| 21 | 2-Azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-3-one | 1025 | - | 1.86 | 2.05 | 1.65 |

| 22 | p-Cymene | 1025.98 | - | 3.77 | 1.55 | 5.34 |

| 23 | Limonene | 1026 | 3.66 | 3.08 | 2.32 | 0.76 |

| 24 | 2-Methyl-1,3-dithiacyclopentane | 1026 | - | 1.15 | - | 1.51 |

| 25 | 1,7-Nonadiene, 4,8-dimethyl- | 1026 | - | 0.85 | 0.46 | - |

| 26 | Thiazole, 5-ethenyl-4-methyl- | 1027 | - | 0.76 | 0.93 | 0.63 |

| 27 | Pyridine, 2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-6-propyl- | 1028 | - | 0.56 | 0.65 | - |

| 28 | Indane | 1029 | - | 1.69 | 0.63 | 2.19 |

| 29 | Cyclohexanol, 3,5-dimethyl- | 1030 | - | 3.26 | 2.83 | 2.94 |

| 30 | β-Phellandrene | 1031 | 2.68 | 1.77 | 4.36 | 2.82 |

| 31 | D-Limonene | 1031.27 | 3.15 | 4.13 | 3.19 | 2.35 |

| 32 | Eucalyptol | 1034.33 | - | 5.91 | 6.87 | 4.31 |

| 33 | 3-Octen-2-one, (E)- | 1035 | - | 3.23 | 3.92 | 2.89 |

| 34 | Ocimene | 1037 | 0.53 | 5.72 | 1.21 | - |

| 35 | 2-Acetyl-5-methylfuran | 1037.22 | - | 0.50 | 0.57 | - |

| 36 | (S)-2,5-Dimethyl-3-vinylhex-4-en-2-ol | 1039 | 0.96 | 4.32 | 4.32 | 2.93 |

| 37 | 3-Octen-2-one | 1040 | - | 1.89 | 1.40 | 1.55 |

| 38 | BenzeneacetAldehyde | 1045.59 | - | 0.48 | - | - |

| 39 | (E)-β-Ocimene | 1049 | - | 0.96 | - | - |

| 40 | γ-Terpinene | 1060.24 | - | 0.57 | - | 3.02 |

| 41 | Benzenemethanol, α-methyl- | 1061.21 | - | - | - | 0.94 |

| 42 | trans-4-Thujanol | 1070 | - | - | - | 1.82 |

| 43 | BenzAldehyde, 3-methyl- | 1070.12 | - | 0.48 | - | 2.37 |

| 44 | (Z)-Pent-2-enyl butyrate | 1091 | - | - | - | 1.77 |

| 45 | Linalool | 1100.58 | - | - | - | 0.98 |

| 46 | 6-Nonenal, (Z)- | 1103.52 | - | - | - | 1.03 |

| 47 | Pinocarveol | 1138 | - | - | 0.91 | - |

| 48 | Myrcenone | 1145 | - | - | 0.52 | - |

| 49 | p-Mentha-1 (7),2-dien-8-ol | 1163 | - | - | 0.70 | - |

| 50 | Pinocarvone | 1164 | - | - | 1.41 | - |

| 51 | Phenol, 4-ethyl- | 1165.40 | - | - | 0.63 | - |

| 52 | (E)-2,6-Dimethylocta-5,7-dien-2-ol | 1169 | - | - | - | 1.66 |

| 53 | Lavandulol | 1170 | - | - | - | 1.36 |

| 54 | Borneol | 1170.41 | - | - | 0.68 | - |

| 55 | Terpinen-4-ol | 1181.45 | - | 0.53 | - | 2.38 |

| 56 | 2-Butenoic acid, hexyl ester | 1191 | - | - | - | 0.73 |

| 57 | (-)-Dihydrocarveol | 1192 | - | - | - | 0.56 |

| 58 | α-Terpineol | 1195.55 | - | - | - | 0.59 |

| 59 | Benzamide | 1344 | - | 0.46 | - | - |

| 60 | 2,3,5,9-tetramethyltricyclo[6.3.0.01,5]undec-3-ene | 1348 | - | 4.20 | - | - |

| 61 | Terpinyl acetate | 1350 | - | 2.89 | - | - |

| 62 | (1α,3β,4β)-p-menthane-3,8-diol | 1355 | - | 0.61 | - | - |

| 63 | Neryl acetate | 1365.22 | - | 3.09 | - | - |

| 64 | Methyl 4-aminobenzoate | 1372 | 1.30 | - | - | - |

| 65 | 6,8-Nonadien-2-one, 8-methyl-5- (1-methylethyl)-, (E)- | 1373 | 0.59 | - | - | - |

| 66 | (-)-α-Copaene | 1376 | 3.54 | - | - | - |

| 67 | Di-epi-α-cedrene- (I) | 1382 | 5.52 | - | - | - |

| 68 | (-)-β-Bourbonene | 1384 | 1.12 | - | - | - |

| 69 | (-)-Modhephene | 1385 | 0.63 | - | - | - |

| 70 | Damascenone | 1386 | 0.71 | - | - | - |

| 71 | Acetic Acid, phenoxy- | 1389 | 0.79 | - | - | - |

| 72 | β-Cubebene | 1390 | 9.42 | - | - | - |

| 73 | Niacinamide | 1419 | 0.80 | - | - | - |

| 74 | Ethyl mandelate | 1421 | - | 0.69 | 0.51 | 1.98 |

| 75 | Benzoic Acid, 4-methoxy- | 1424.27 | 1.49 | - | - | - |

| 76 | Benzenemethanol, 4-hydroxy- | 1426 | 1.42 | - | - | 0.61 |

| 77 | 3-Hexanone, 1-phenyl- | 1427 | 5.14 | 0.87 | 0.60 | 2.34 |

| 78 | 2-Propenoic Acid, 3-phenyl- | 1427.53 | - | - | - | 1.04 |

| 79 | Quinoxaline, 2,3-dimethyl- | 1428 | 0.50 | - | - | - |

| 80 | (E,E)-2,4-Undecadienal | 1430 | 2.16 | 0.40 | - | 1.08 |

| 81 | (+)-Calarene | 1432 | 5.08 | 0.36 | - | 1.43 |

| 82 | β-Caryophyllene | 1432.49 | 6.15 | 1.04 | 0.72 | 2.89 |

| 83 | γ-Elemene | 1433 | 2.27 | - | - | 0.92 |

| 84 | Ethyl β-safranate | 1434 | 3.22 | 0.47 | - | 1.31 |

| 85 | trans-α-Bergamotene | 1435 | 3.27 | 0.43 | - | 1.22 |

| 86 | 2-Hydroxymethylbenzimidazole | 1437 | 3.14 | - | - | 0.96 |

| 87 | Ethanone, 1- (3-hydroxyphenyl)- | 1439 | 0.76 | - | - | - |

| 88 | Azulene, 1,2,3,3a,6,8a-hexahydro-1,4-dimethyl-7- (1-methylethyl)-, (1R,3aS,8aS)- | 1440 | 3.09 | - | - | - |

| 89 | Naphthalene, 1,2,4a,5,8,8a-hexahydro-4,7-dimethyl-1- (1-methylethyl)-, (1α,4aβ,8aα)- (.+/-.)- | 1440 | 3.34 | - | - | 0.99 |

| 90 | Aromandendrene | 1440 | 0.85 | - | - | - |

| 91 | (+)-α-Muurolene | 1440 | - | 0.62 | - | 1.67 |

| 92 | Benzyl angelate | 1446 | 1.25 | - | - | - |

| 93 | -6-Methyl-2-methylene-6- bicyclo[3.1.1]heptane | 1446 | 1.02 | - | - | - |

| 94 | (-)-Aristolene | 1447 | 2.08 | - | - | - |

| 95 | Benzene, 1- (1,5-dimethylhexyl)-4-methyl- | 1449 | 1.17 | - | - | - |

| 96 | (-)-α-Himachalene | 1449 | 1.11 | - | - | - |

| 97 | Acetophenone, 4’-hydroxy- | 1455 | 0.76 | - | - | 2.21 |

| 98 | (E)-β-Famesene | 1457 | - | - | - | 1.02 |

| 99 | 5,9-Undecadien-2-ol, 6,10-dimethyl- | 1459 | - | - | - | 0.74 |

| 100 | 1,1’- (1,4-phenylene)bis-Ethanone | 1461 | 0.67 | - | - | - |

| 101 | Benzene, [1-[[1- (1-methylethyl)-3-butenyl]oxy]ethyl]-, [S- (R*,R*)]- | 1463 | - | - | - | 0.91 |

| 102 | 2-Pinen-10-yl isobutyrate | 1466 | - | - | - | 1.46 |

| 103 | (1R,9R,E)-4,11,11-Trimethyl-8-methylenebicyclo[7.2.0]undec-4-ene | 1466 | - | - | - | 0.90 |

| 104 | Acoradiene | 1471 | - | - | - | 0.64 |

| 105 | (4R,4aS,6S)-4,4a-Dimethyl-6- (prop-1-en-2-yl)-1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,7-octahydronaphthalene | 1476 | 0.57 | - | - | - |

| 106 | Eudesma-2,4,11-triene | 1479 | 0.54 | - | - | - |

| 107 | (-)-Germacrene D | 1481 | 1.52 | - | - | - |

| 108 | 3- (4-Hydroxyphenyl)propanal | 1490 | - | 0.37 | 1.01 | - |

| 109 | (1S,2E,6E,10R)-3,7,11,11-Tetramethylbicyclo[8.1.0]undeca-2,6-diene | 1495 | - | 0.81 | 2.07 | - |

| 110 | Benzyl tiglate | 1498 | - | - | 0.68 | - |

| 111 | α-Muurolene | 1499 | 0.66 | - | 0.63 | - |

| 112 | Epizonarene | 1501 | - | - | 0.57 | - |

| 113 | α-Cuprenene | 1509 | - | - | 0.61 | - |

| 114 | (E)-α-Bisabolene | 1512 | 0.65 | 0.47 | 1.27 | - |

| 115 | (-)-γ-Cadinene | 1513 | - | - | 0.74 | - |

| 116 | cis-Calamenene | 1523 | 3.01 | - | - | - |

| 117 | (+)-δ-Cadinene | 1524 | 0.64 | - | - | - |

| 118 | Cadinadiene,cadina-1,4-diene | 1532 | 0.92 | - | - | - |

| 119 | (+)-α-Cadinene | 1538 | 0.89 | - | - | - |

| 120 | β-Vetivenene | 1540 | 0.50 | - | - | - |

| 121 | 3,7 (11)-Eudesmadiene | 1542 | 1.29 | - | - | - |

| Total | 97.21 | 97.89 | 97.97 | 96.79 | ||

| Terpineoids | 65.31 | 44.00 | 46.91 | 46.15 | ||

| Ketone | 12.24 | 10.00 | 8.16 | 9.61 | ||

| Ester | 6.12 | 8.00 | 8.16 | 9.61 | ||

| Alcohol | 4.08 | 6.00 | 6.12 | 13.46 | ||

| Acid | 4.08 | 5.00 | - | 1.92 | ||

| Hydrocarbons | - | 6.00 | 12.24 | 1.92 | ||

| Heterocyclic compound | 4.08 | 8.00 | 8.16 | 5.77 | ||

| Aromatics | - | 6.00 | 6.12 | 5.77 | ||

| Amine | 2.04 | 2.00 | - | - | ||

| Aldehyde | 2.04 | 8.00 | 2.04 | 5.77 | ||

| Time(h) | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 24 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | CAS | Mean±SEM% | ||||||

| β-Caryophyllene | 87-44-5 | 100±0.00 | 100±0.00 | 100±0.00 | 94.07±2.97a | 83.23±5.2abc | 83.23±5.2ab | 85.00±4.28ab |

| α-Terpinene | 99-86-5 | 100±0.00 | 100±0.00 | 85.05±7.87abc | 67.72±2.69abcd | 70.61±10.32abcd | 68.15±10.76bcd | 80.37±1.61abc |

| β-Pinene | 127-91-3 | 80.61±11.56abc | 50.27±8.93bc | 42.06±4.83def | 58.36±12.59cde | 60.69±5.52bcd | 73.45±4.92abc | 72.01±5.01abc |

| Linalool | 78-70-6 | 55.19±2.89bc | 69.11±1.38ab | 62.29±4.85bcd | 54.94±1.6def | 52.31±1.31cd | 52.98±0.79cd | 53.7±0.85c |

| Eucalyptol | 470-82-6 | 100±0.00 | 100±0.00 | 94.86±2.57ab | 92.22±4.01ab | 100±0.00 | 100±0.00 | 100±0.00 |

| α-Pinene | 80-56-8 | 100±0.00 | 100±0.00 | 80.43±5.66abc | 86.98±3.49abc | 93.33±6.67a | 87.13±3.57ab | 76.92±4.47abc |

| Phellandrene | 99-83-2 | 100±0.00 | 77.78±11.11ab | 83.07±5.82abc | 93.65±6.35a | 84.13±11.45ab | 72.26±5.56abcd | 52.84±2.47c |

| Ocimene | 13877-91-3 | 4.58±17.56de | -14.31±9.51e | -9.39±4.13h | -4.32±2.27hi | -4.32±2.27e | -4.53±2.43f | 7.34±6.82d |

| D-Limonen | 5989-27-5 | -9.16±2.38e | -11.27±4.36e | -8.43±1.56h | -8.43±3.24i | -8.97±2.19e | 11.44±3.23f | 2.7±1.96d |

| γ-Terpinene | 99-85-4 | 48.89±14.57bcd | 26.83±8.04cd | 28.92±1.31defg | 25.41±4.81fgh | 43.39±10.62d | 53.33±4.63cd | 20.08±6.76d |

| o-Cymene | 527-84-4 | 100±0.00 | 100±0.00 | 91.91±4.05ab | 71.42±5.72abcd | 70.98±5.49abcd | 63.14±1.57bcd | 54.77±5.29c |

| Cineole | 406-67-7 | 100±0.00 | 65.02±3.37abc | 45.95±2.57def | 63.24±7.25bcde | 48.03±4.16d | 79.35±10.62abc | 65.72±9.22bc |

| 1,4-Diethylbenzene | 105-05-5 | -1.06±7.35e | 4.15±9.54de | -9.09±4.29h | -1.45±1.45hi | 1.15±1.15e | 1.76±7.54f | 9.70±5.78d |

| Limonene | 138-86-3 | -10.82±10.64e | -17.32±8.52e | -9.09±4.29h | -9.09±4.29i | -9.09±4.29e | 12.87±3.25f | 3.20±1.62d |

| 3-Carene | 13466-78-9 | 8.91±13.76cde | 1.14±5.46de | 1.42±3.34gh | -10.07±4.36i | -9.97±4.43e | 11.42±3.1f | 3.70±6.42d |

| 1-Phenylhexan-3-one | 29898-25-7 | 8.38±16.9de | 1.63±8.13de | 17.21±12.83fgh | 5.41±1.84hi | 5.41±1.84e | 16.76±3.32ef | 21.56±1.52d |

| Myrtol | 8002-55-9 | 65.02±3.37ab | 39.09±5.09bcd | 23.74±4.27efgh | 12.27±2.58ghi | 12.27±2.58de | 12.27±2.58f | 21.43±4.59d |

| df | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | |

| F-Value | 24.532 | 32.647 | 38.263 | 47.305 | 41.381 | 37.517 | 35.776 | |

| P-Value | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).