1. Introduction

Deep learning has emerged as a powerful technique for solving complex problems across various domains, including computer vision, natural language processing, and robotics. The success of deep neural networks (DNNs) in these domains has led to an increasing demand for efficient hardware architectures that can accelerate the training and inference processes. Traditional von Neumann architectures, with their separated CPU and memory units, struggle to meet the high computational demands and data movement requirements of deep learning workloads [

28,

29]. To address these challenges, researchers have been exploring innovative approaches such as chiplet-based architectures and processing-in-memory (PIM) techniques.

Chiplet-based architectures offer a promising solution to the limitations of monolithic chip designs in deep learning. Monolithic chips, with their large area and on-chip interconnection costs, face challenges in scaling up to accommodate the growing sizes of deep learning models. Chiplet-based architectures, on the other hand, divide the system into smaller interconnected units called chiplets, allowing for improved scalability, modularity, and flexibility. These chiplets can be designed and optimized independently, leading to better yield and reduced costs. Furthermore, chiplet-based architectures enable efficient utilization of resources by distributing the computational workload across multiple chiplets, resulting in improved performance and energy efficiency.

In parallel, processing-in-memory (PIM) techniques have gained significant attention as a means to overcome the memory bottleneck in deep learning. In traditional architectures, data movement between the processor and memory units consumes a significant amount of energy and time. PIM architectures aim to alleviate this bottleneck by integrating processing units directly into the memory subsystem. By performing computations in close proximity to the data, PIM architectures minimize data movement, reduce latency, and improve energy efficiency. PIM architectures can leverage emerging memory technologies like resistive random-access memory (ReRAM) to achieve high-performance and energy-efficient acceleration of deep learning tasks.

This comprehensive review aims to provide insights into the advancements in chiplet-based architectures and processing-in-memory techniques for deep learning applications. It explores the challenges faced by monolithic chip architectures and highlights the potential of chiplet-based designs in addressing these challenges. The review familiarizes SIAM (Scalable In-Memory Acceleration with Mesh), a benchmarking simulator that evaluates chiplet-based in-memory computing (IMC) architectures, and showcases the flexibility and scalability of SIAM through benchmarking different deep neural networks.

Furthermore, the review delves into the design considerations of processing-in-memory architectures for deep learning workloads. It emphasizes the importance of dataflow-awareness and communication optimization in the design of PIM-enabled manycore platforms. By understanding the unique traffic patterns and data exchange requirements of different machine learning workloads, PIM architectures can be optimized to minimize latency and improve energy efficiency. The review also discusses the challenges associated with on-chip interconnection networks, thermal constraints, and the need for scalable communication in chiplet-based architectures.

Additionally, the review presents a heterogeneous PIM system for energy-efficient neural network training. This approach combines fixed-function arithmetic units and programmable cores on a 3D die-stacked memory, providing a unified programming model and runtime system for efficient task offloading and scheduling. The review highlights the significance of programming models that accommodate both fixed-function logics and programmable cores, as well as achieving balanced hardware utilization in heterogeneous systems with abundant operation-level parallelism.

Finally, the review explores thermally efficient dataflow-aware monolithic 3D (M3D) NoC architectures for accelerating CNN inferencing. It discusses the benefits of integrating processing-in-memory cores using ReRAM technology and emphasizes the importance of efficient network-on-chip (NoC) designs to reduce data movement. The review compares different architectures and highlights the advantages of TEFLON (Thermally Efficient Dataflow-Aware 3D NoC) over performance-optimized space-filling curve (SFC)-based counterparts in terms of energy efficiency, inference accuracy, and thermal resilience.

In Summary, the advancements in chiplet-based architectures and processing-in-memory techniques have the potential to revolutionize deep learning hardware. These approaches offer scalability, flexibility, improved performance, and energy efficiency, addressing the challenges faced by traditional monolithic chip designs. By leveraging the benefits of chiplet-based architectures and processing-in-memory techniques, researchers and engineers can pave the way for enhanced deep learning capabilities and contribute to the development of efficient and powerful AI hardware [

30,

31].

This review is divided into several sections, each focusing on different aspects of processing-in-memory architectures for deep neural networks.

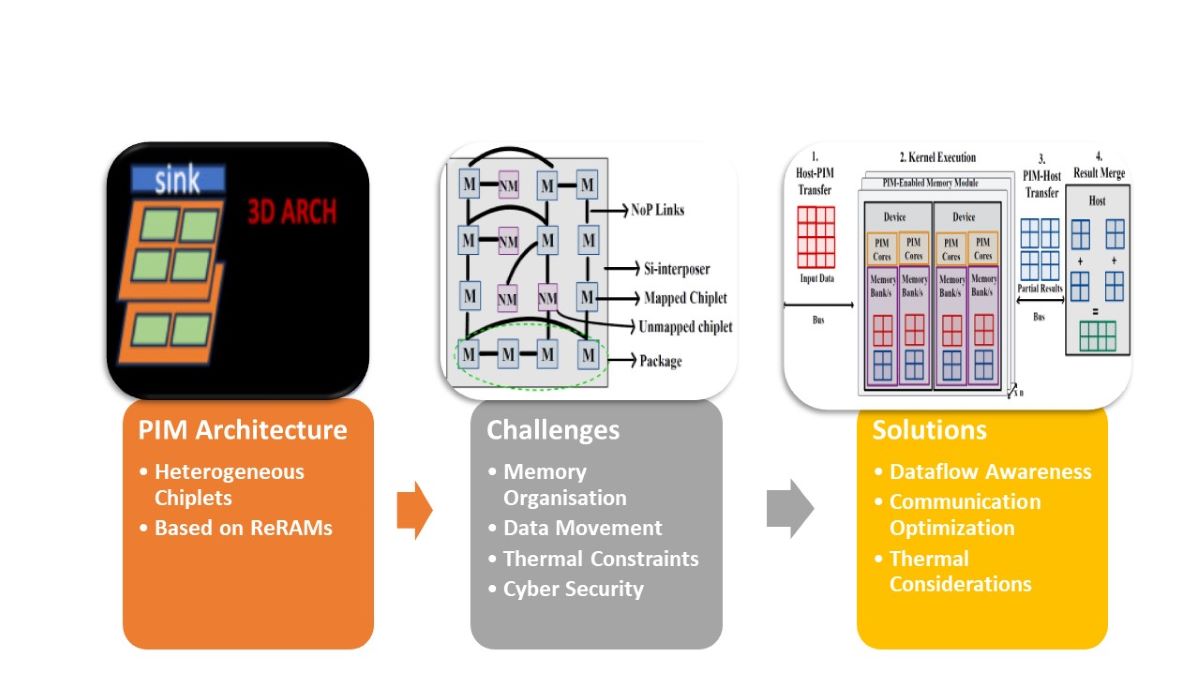

Figure 1 illustrates the layout of the article, showcasing the main challenges associated with PIM-Enabled Manycore Architectures.

Section 1 provides an overview of the challenges faced by traditional architectures and the potential solutions offered by chiplet-based designs and processing-in-memory (PIM) techniques.

Section 2 then delves into the details of PIM, discussing its innovative approach of integrating computational units into the memory subsystem and the benefits it brings in terms of performance, energy efficiency, and scalability. The challenges associated with implementing PIM in heterogeneous CPU-GPU architectures are explored, including memory organization, programming models, data movement, and power/thermal constraints.

Section 3 highlights the importance of dataflow-awareness, communication optimization, and thermal considerations in designing PIM-enabled manycore architectures. Furthermore, it discusses a heterogeneous PIM system for energy-efficient neural network training and thermally efficient dataflow-aware monolithic 3D NoC architectures for accelerating CNN inferencing.

Section 4 addresses the cybersecurity challenges associated with deep neural networks (DNNs). It discusses the increased attack surface due to the growth of AI capabilities and explores adversarial attacks, model stealing attacks, and concerns regarding privacy and data leakage. Finally, the review concludes by emphasizing the potential of PIM techniques in revolutionizing deep learning hardware and contributing to the development of efficient AI hardware [

32].

2. Processing in Memory (PIM)

2.1. Introduction

Processing-in-memory (PIM) is an innovative approach that aims to overcome the memory bottleneck in traditional computer architectures by integrating computational units directly into the memory subsystem. With the rapid growth of data-intensive applications, such as deep learning, PIM has gained significant attention as a promising solution for improving performance, energy efficiency, and overall system scalability. In traditional computer architectures, the processor and memory units are separate entities, requiring frequent data movement between them. This data movement, often referred to as the von Neumann bottleneck, consumes a significant amount of energy and introduces latency, limiting the overall system performance. As the computational demands of modern applications continue to increase, the memory subsystem becomes a critical performance bottleneck. PIM architectures aim to address this bottleneck by bringing processing units closer to the data. By integrating computational units, such as arithmetic units or accelerators, into the memory cells or in close proximity to them, PIM architectures enable computations to be performed directly on the data, minimizing the need for data movement. This approach not only reduces energy consumption but also improves system performance by reducing memory access latency. Various memory technologies can be leveraged in PIM architectures, including static random-access memory (SRAM), dynamic random-access memory (DRAM), and emerging non-volatile memory technologies such as resistive random-access memory (ReRAM) and phase-change memory (PCM)[

33,

34]. These memory technologies offer different trade-offs in terms of density, access speed, power consumption, and endurance, and can be tailored to suit specific PIM design requirements. PIM architectures have shown promising results in a wide range of applications, particularly in data-intensive domains such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, and big data analytics. Deep learning, in particular, benefits greatly from PIM architectures as they can significantly reduce the data movement between the processor and memory during the training and inference processes, leading to improved energy efficiency and faster computation.

2.2. Challenges

Processing-in-memory (PIM) refers to the integration of processing elements within the memory subsystem of a computing system. Heterogeneous CPU-GPU architectures, which combine central processing units (CPUs) and graphics processing units (GPUs), can benefit from PIM to improve performance and energy efficiency. However, there are several challenges associated with implementing PIM in heterogeneous CPU-GPU architectures. Here are some of the key challenges:

Memory Organization: PIM requires a rethinking of memory organization to enable processing elements within the memory subsystem. CPUs and GPUs have different memory access patterns and requirements, which need to be accommodated in the design. Efficiently organizing and managing data in a PIM architecture can be complex, especially when dealing with heterogeneous processing units.

Programming Model: PIM architectures require a programming model that allows developers to express data and task parallelism effectively. Developing software for PIM architectures can be challenging due to the need for explicit data placement and synchronization between the CPU and GPU components. The programming models need to be designed to fully exploit the potential parallelism offered by PIM while maintaining ease of use.

Data Movement: Efficient data movement is crucial for PIM architectures. Moving data between the CPU and GPU components can incur significant overhead due to the communication between different memory spaces. Minimizing data movement and optimizing data transfer mechanisms become essential for achieving high performance in heterogeneous CPU-GPU architectures.

Power and Thermal Constraints: PIM architectures can potentially consume significant power due to the increased integration of processing elements within the memory subsystem. Managing power and thermal constraints in heterogeneous CPU-GPU architectures is critical to prevent overheating and ensure reliable operation. Designing efficient power management techniques that balance performance and energy consumption is a significant challenge.

Memory Consistency and Coherence: Maintaining memory consistency and coherence in PIM architectures is complex, particularly in heterogeneous CPU-GPU systems. CPUs and GPUs often have their own caches and memory hierarchies, which need to be synchronized to ensure data integrity and correctness. Developing efficient coherence protocols and memory consistency models for heterogeneous PIM architectures is a non-trivial task.

Hardware Design and Integration: Hardware design challenges arise when integrating processing elements within the memory subsystem. PIM architectures require modifications to the memory controller, cache hierarchy, and interconnects to enable efficient data processing within memory. Co-designing the hardware components and optimizing the integration of processing elements in a heterogeneous CPU-GPU architecture is a significant challenge.

3. PIM Based Systems

Researchers and engineers are actively working on overcoming these obstacles to fully exploit the benefits of processing-in-memory in heterogeneous CPU-GPU architectures.

The following sub-sections provides a comprehensive review that addresses these obstacles and offers potential solutions for maximizing the benefits of processing-in-memory in heterogeneous CPU-GPU architectures.

3.1. Heterogenous PIM Architecture

The challenges associated with training neural networks, particularly deep neural networks (DNNs), arise from the significant energy consumption and time overhead caused by frequent data movement between the processor and memory. Ongoing research aims to maximize the benefits of processing-in-memory in heterogeneous CPU-GPU architectures by overcoming these obstacles.

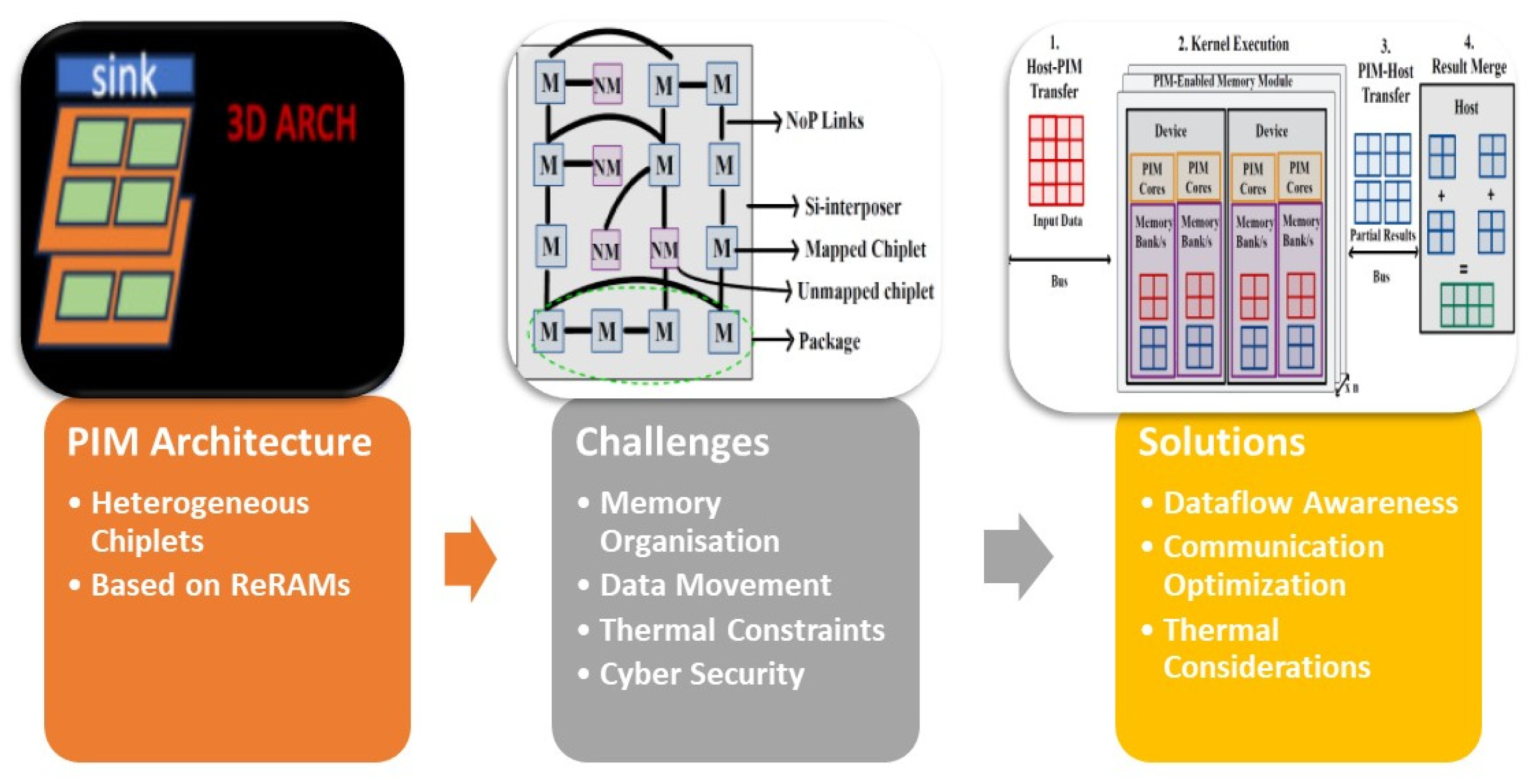

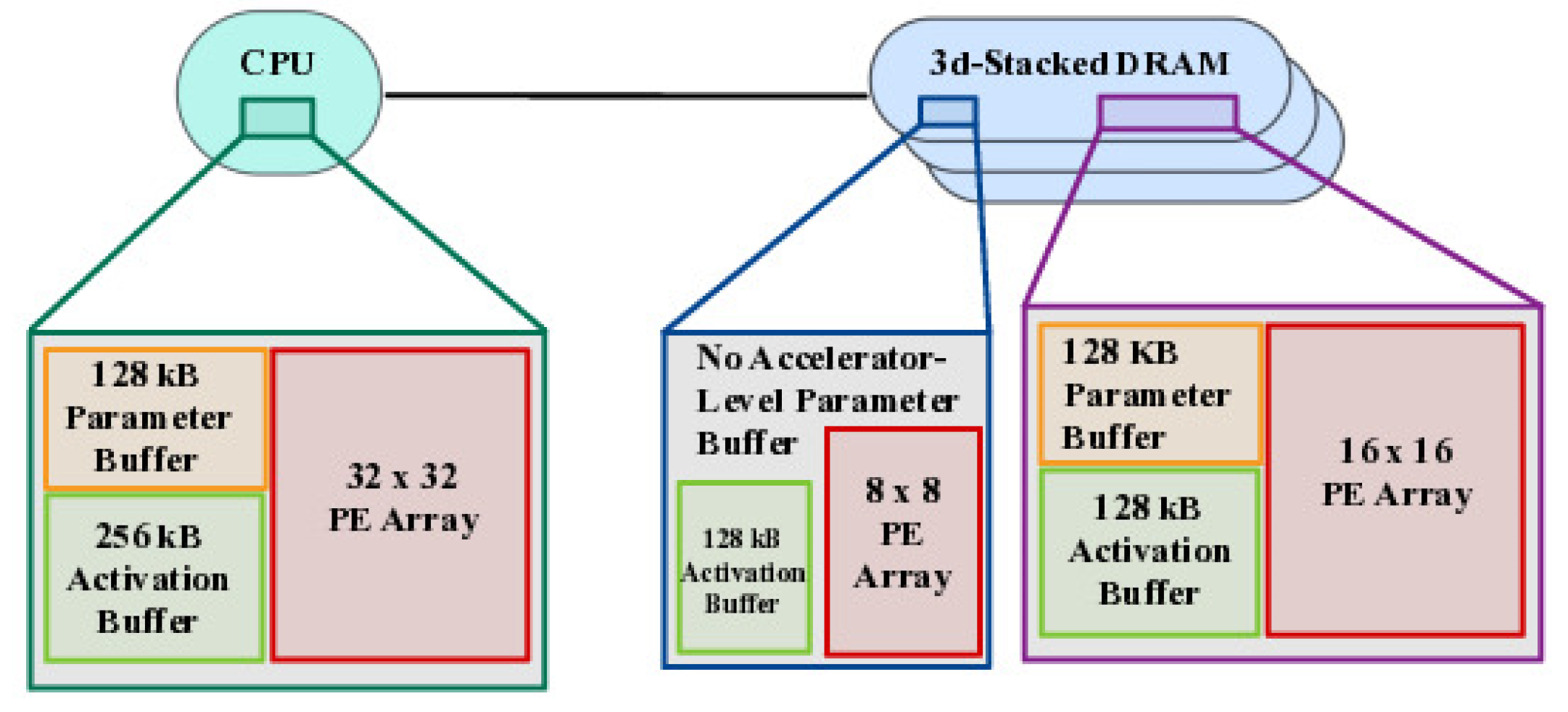

One such approach is proposed in [

1] as a hardware design involves integrating fixed-function arithmetic units and programmable cores on the logic layer of a 3D die-stacked memory (represented in

Figure 2). This configuration creates a heterogeneous processing-in-memory (PIM) architecture that is connected to the CPU. The aim is to minimize data movement and improve system performance by bringing processing capabilities closer to the memory. In addition to the hardware design, a software design is presented, which includes a programming model and runtime system. These components enable programmers to develop, offload, and schedule various neural network training operations across the CPU and the heterogeneous PIM architecture. The objective is to achieve program portability, facilitate program maintenance, enhance system energy efficiency, and improve hardware utilization. By combining the proposed hardware and software designs, a comprehensive solution is offered to address the challenges of energy consumption and data movement during neural network training. The heterogeneous PIM architecture, accompanied by the programming model and runtime system, provides an effective approach for efficient neural network training by leveraging the advantages of processing-in-memory techniques.

The challenges of programming processing-in-memory (PIM) architectures for neural network acceleration in heterogeneous systems with fixed-function logics and programmable cores are non-trivial. One key requirement is a unified programming model that can effectively handle the heterogeneity of PIM architectures. Achieving balanced hardware utilization in such heterogeneous systems is another challenge, particularly in harnessing operation-level parallelism for efficient execution of neural network training workloads. This architecture [

1] aims to minimize data movement and enhance energy efficiency by performing computations in close proximity to the data. To enable programming flexibility, the OpenCL programming model has been extended to accommodate the heterogeneity of PIM architectures. This extension allows developers to express parallelism and take advantage of both fixed-function logics and programmable cores. Insights into the characteristics of neural network training workloads have been provided, showcasing profiling results of time-consuming and memory-intensive operations across different training models. The significance of reducing data movement is emphasized, motivating the adoption of PIM architectures. The combination of hardware and software design techniques aims to improve performance, energy efficiency, and hardware utilization in heterogeneous CPU-GPU systems with PIM capabilities.

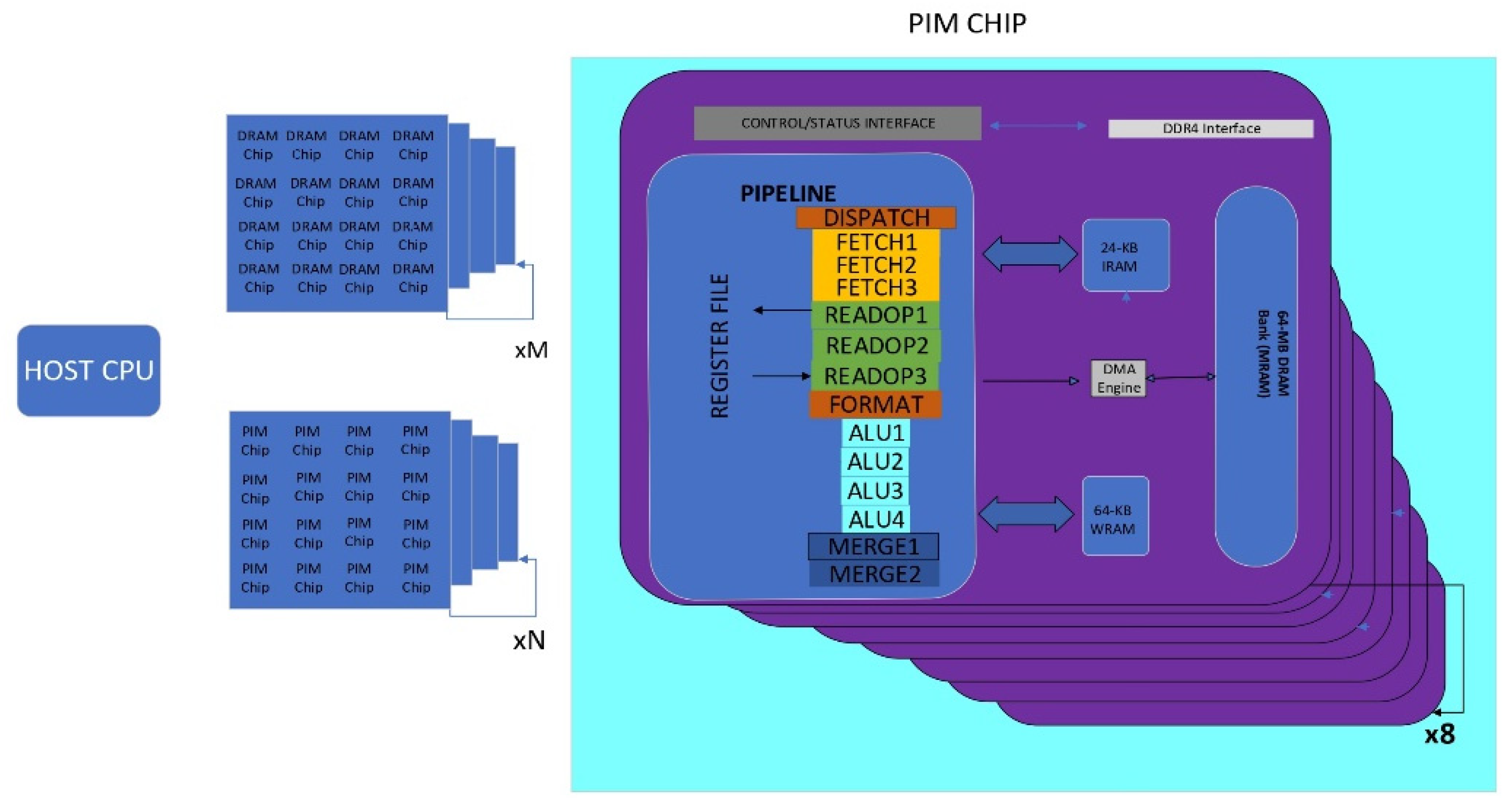

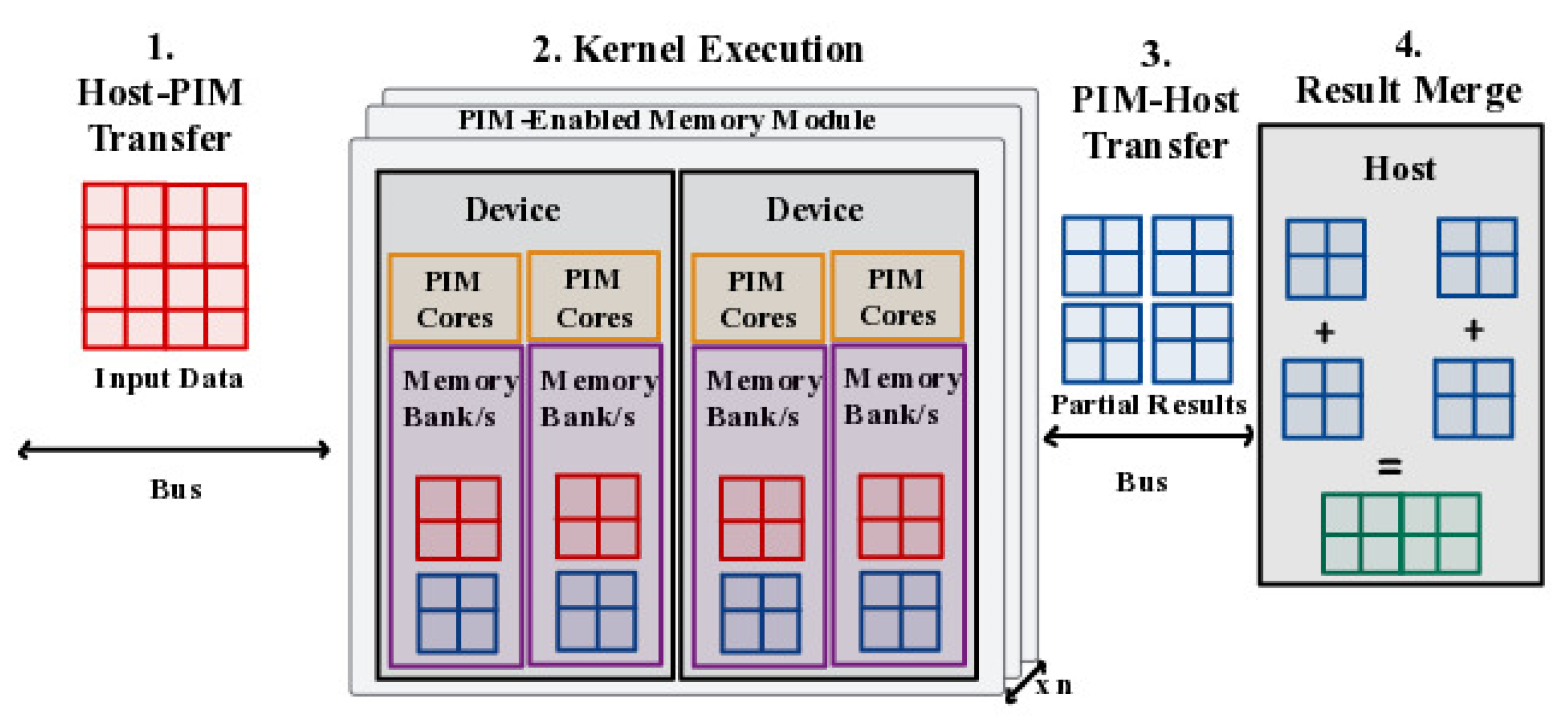

Another study in [

7] offers recommendations for software designers, insights into workload suitability for the PIM system, and suggestions for future hardware and architecture designers of PIM systems. It discusses the concept of processing-in-memory (PIM) as a solution to the data movement bottleneck in memory-bound workloads. It introduces the UPMEM PIM architecture, which combines DRAM memory arrays with in-order cores called DRAM Processing Units (DPUs) integrated in the same chip(as depicted in

Figure 3). The study presents key takeaways from the comprehensive analysis of the UPMEM PIM architecture.

Firstly, it describes the experimental characterization of the architecture using microbenchmarks and introduces PrIM (Processing-In-Memory benchmarks), a benchmark suite consisting of 16 memory-bound workloads from various application domains. The analysis provides insights into the performance and scaling characteristics of PrIM benchmarks on the UPMEM PIM architecture. It compares the architecture’s performance and energy consumption to CPU and GPU counterparts. The evaluation is conducted on real UPMEM-based PIM systems with different numbers of DPUs.

Another work in [

10] discusses the development of a practical processing-in-memory (PIM) architecture using commercial DRAM technology. The proposed PIM architecture leverages 2.5D/3D stacking integration technologies and exploits bank-level parallelism in commodity DRAM to provide higher bandwidth and lower energy per bit transfer to processors. Importantly, the architecture does not require changes in host processors or application code, making it easily integrable with existing systems. The PIM architecture is implemented with a 20nm DRAM technology and integrated it with an unmodified commercial processor. A software stack is also developed to enable the execution of existing applications without modifications. System-level evaluations demonstrated significant performance improvements for memory-bound neural network kernels and applications, with speedups of 11.2x and 3.5x, respectively. Additionally, the proposed PIM architecture reduced the energy per bit transfer by 3.5x and improved the overall energy efficiency of the system by 3.2x.

The ever-increasing demand for high-performance machine learning applications has spurred a quest for more efficient and powerful processors. One of the key challenges in this domain lies in optimizing the data flow between memory and computing units within conventional architectures, which often leads to significant energy consumption and latency issues. Addressing this challenge, [

12] presents an innovative architecture called Lattice, which leverages Nonvolatile Processing-In-Memory (NVPIM) based on Resistive Random Access Memory (ReRAM) to accelerate Deep Convolution Neural Networks (DCNN). The primary objective of Lattice is to overcome the drawbacks associated with costly analog-digital conversions and excessive data copies or writes. To achieve this, the architecture introduces a novel approach to compute the partial sum of dot products between feature maps and weights in a CMOS peripheral circuit, effectively eliminating the need for analog-digital conversions. By doing so, Lattice not only reduces the energy overhead associated with these conversions but also enhances the overall system energy efficiency. Furthermore, Lattice incorporates an efficient data mapping scheme that aligns the feature map and weight data, minimizing unnecessary data copies or writes. This optimization helps to further reduce energy consumption and improve the overall performance of the system. In addition, the architecture introduces a zero-flag encoding scheme, specifically designed for sparse DCNNs, which enables energy savings during the processing of zero-values. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed architecture, extensive experiments were conducted, comparing Lattice to three state-of-the-art NVPIM designs: ISAAC, PipeLayer, and FloatPIM. The results clearly demonstrate that Lattice outperforms these existing designs, achieving substantial energy efficiency improvements ranging from 4x to 13.22x. The significance of Lattice extends beyond its immediate contributions. It sheds light on the pressing need for ultra-low power machine learning processors, especially in the era of resource-constrained edge devices and Internet of Things (IoT) applications. By addressing the challenges associated with data traffic between memory and computing units, Lattice paves the way for more energy-efficient and high-performance machine learning systems.

[

18] introduces PIM-STM, a library that provides various implementations of Transactional Memory (TM) for PIM systems. It explores the challenges of efficiently implementing TM in PIM devices and evaluates different design choices and algorithms. It also presents experimental results demonstrating the performance and memory efficiency gains achieved by using PIM-STM in comparison to conventional CPU-based systems. Overall, the work aims to provide guidelines for developers and offers a library to test alternative STM designs for PIM architectures.

[

19] discusses a proposed architecture called “Reconfigurable Processing-in-Memory” (PIM) for data-intensive applications. The architecture aims to address the challenges posed by deep neural networks (DNNs) and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in terms of resource constraints and data movement overheads. Existing PIM architectures have trade-offs in power, performance, area, energy efficiency, and programmability. The proposed solution focuses on achieving higher energy efficiency while maintaining programmability and flexibility. It introduces a novel multi-core reconfigurable architecture integrated within DRAM sub-arrays. Each core consists of multiple processing elements (PEs) with programmable functional units constructed using high-speed reconfigurable multi-functional look-up-tables (M-LUTs). These M-LUTs enable multiple functional outputs in a time-multiplexed manner, eliminating the need for different LUTs for each function.The architecture supports various operations required for CNN and DNN processing, including convolution, pooling, activation functions, and batch normalization. It offers improved efficiency and performance compared to conventional PIM architectures, making it suitable for demanding big data and AI acceleration applications. Overall, the proposed reconfigurable PIM architecture aims to provide energy-efficient and high-performance solutions for data-intensive applications by leveraging multi-functional look-up-tables and integrating them within DRAM sub-arrays.

[

20] discusses a new architecture called StreamPIM, which aims to address the memory wall issue and improve performance and energy efficiency in large-scale applications. The proposed architecture leverages racetrack memory (RM) techniques, which increase memory density and enable processing-in-memory (PIM) architectures. StreamPIM tightly couples the memory core and computation units, constructing a matrix processor from domain-wall nanowires without using CMOS-based computation units. It also introduces a domain-wall nanowire-based bus to eliminate electromagnetic conversion. The architecture optimizes performance by leveraging RM internal parallelism. The proposed StreamPIM architecture overcomes data transfer overheads and conversion inefficiencies, offering improved performance and energy efficiency for matrix computations.

In order to compare and analyze different architectures used in Processing-in-Memory (PIM) systems, a table has been compiled (

Table 1) outlining the significant features of various PIM architectures. The table provides a comprehensive overview of the key characteristics and functionalities of each architecture, facilitating a better understanding of their respective advantages and limitations.

3.2. Data Flow Aware Architecture

As deep convolutional neural networks (DNNs) become more complex, the need for a manycore architecture with multiple ReRAM-based processing elements (PEs) on a single chip arises. However, traditional PIM-based architectures often prioritize computation and overlook the crucial role of communication. Merely increasing computational resources without addressing the communication infrastructure’s limitations can hamper overall performance. The use of chiplet-based 2.5D architectures has gained attention in recent years. These architectures involve the integration of multiple smaller dies through a network-on-interposer (NoI) [

2]. The motivation behind this approach has been to achieve energy efficiency and cost advantages compared to monolithic planar chips. Additionally, the exploration of 3D integration techniques, such as through-silicon vias (TSVs) or monolithic inter-tier vias (MIVs), offers opportunities for improved performance and energy efficiency. In the context of machine learning workloads, it is crucial to consider the specific traffic patterns and data exchange requirements. Real-world scenarios often involve the simultaneous execution of multiple machine learning applications with varying inputs. To address this, dataflow-awareness becomes essential in manycore accelerators designed for machine learning applications. Different machine learning workloads, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), graph neural networks (GNNs), and transformer models, exhibit unique on-chip traffic patterns when mapped onto a manycore system. Optimizing the dataflow between chip-lets or processing elements (PEs) is critical for reducing latency and improving energy efficiency. One approach involves mapping consecutive neural layers onto neighboring chip-lets or PEs to minimize long-range and multi-hop data exchange as stated in [

2].

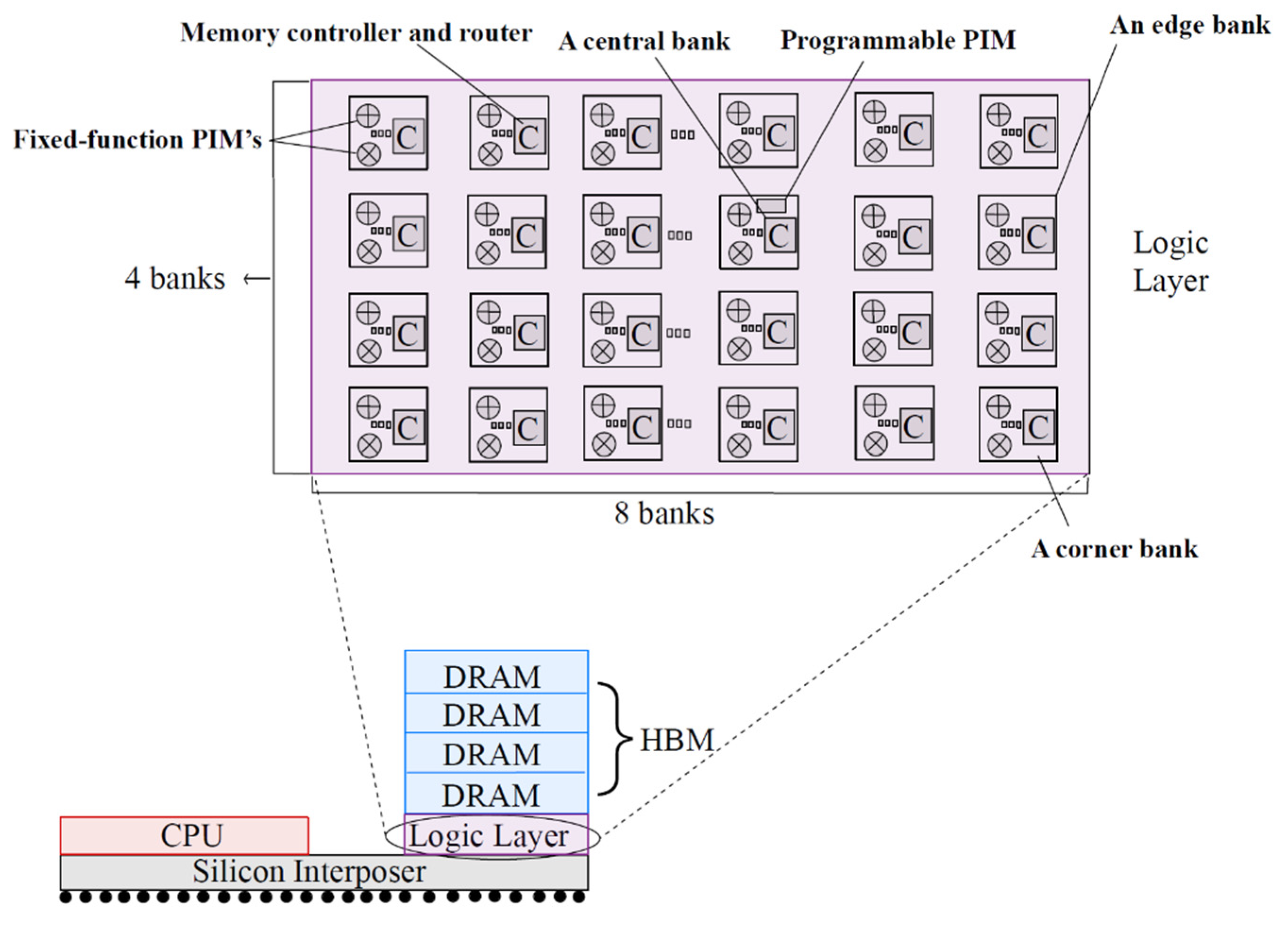

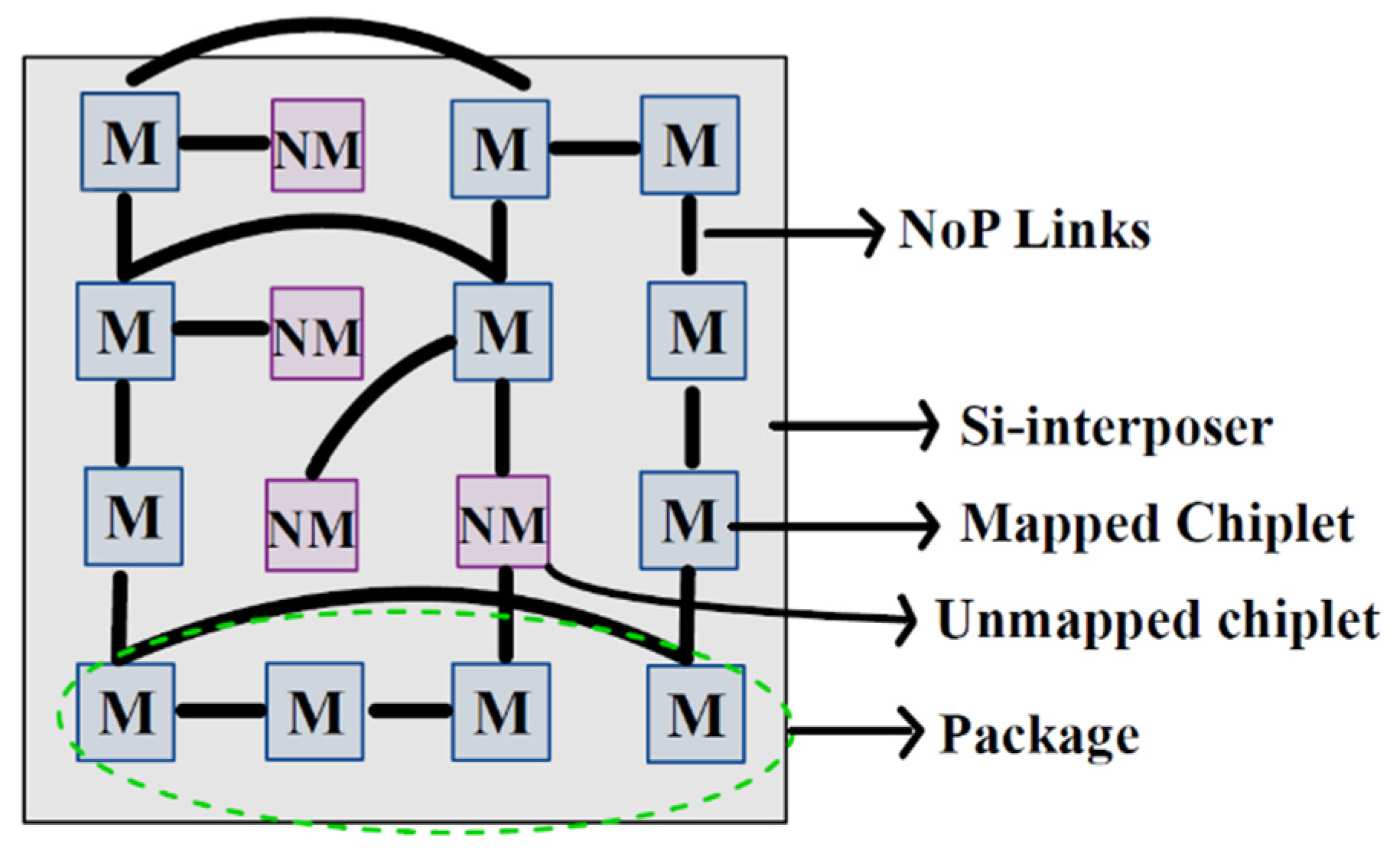

Figure 4 provides a visual representation of the SWAP architecture described for a chiplet-based system in [

2]. This architecture incorporates both mapped (M) and unmapped (NM) chiplets, as shown in the diagram. The inclusion of a limited number of mapped and unmapped chiplets enables the system to optimize its performance.

To cater to machine learning workloads, the design of a dataflow-aware network-on-interposer (NoI) architecture suited for 2.5D/3D integration is important. However, several challenges arise when communicating between chiplets, including dealing with large physical distances, mitigating issues with poor electrical wires, and managing power constraints. Achieving ultra-high bandwidth, energy-efficient, and low-latency inter-chiplet data transfer is a significant consideration. Furthermore, thermal challenges need to be addressed when designing dataflow-aware manycore architectures.

[

11] also discusses the advantages and challenges of using resistive random-access memory (ReRAM)-based processing-in-memory (PIM) architectures for deep learning applications. ReRAM-based architectures have shown potential in accelerating deep learning algorithms while being more energy-efficient than traditional GPUs. However, they also have limitations in terms of model accuracy and performance. The document highlights the design challenges associated with ReRAM-based PIM architectures for Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). It addresses the precision sensitivity of CNNs and the communication-intensive nature of GNNs as specific challenges. The document also mentions the non-idealities of ReRAMs, such as noise, hard faults, process variations, and limited write endurance, which can affect the implementation of large-scale deep learning algorithms. The authors propose ReRAM-based heterogeneous manycore PIM designs as a solution to address these challenges and shortcomings.

[

14] discusses the implementation of processing-in-memory (PIM) technology to accelerate deep learning (DL) workloads. It addresses the challenge of increasing fabrication costs in monolithic PIM accelerators by proposing a 2.5-D system that integrates multiple PIM chiplets through a network-on-package (NoP). However, the communication requirements of DL workloads are not adequately considered in existing NoP architectures. The proposed SWAP architecture in [

14] takes into account the traffic characteristics of DL applications and achieves significant performance and energy consumption improvements with lower fabrication costs compared to state-of-the-art NoP topologies. It presents an optimization methodology for designing an irregular NoP architecture based on DL workloads, along with experimental evaluations demonstrating the superiority of SWAP.

[

15] discusses the challenges of on-chip training for large-scale deep neural networks (DNNs) and proposes a mixed-precision RRAM-based compute-in-memory (CIM) architecture called MINT to overcome these challenges. The MINT architecture utilizes analog computation inside the memory array to speed up vector-matrix multiplications (VMM) and addresses the issues of higher weight precision and analog-to-digital converter (ADC) resolution. The architecture splits the multi-bit weights into most significant bits (MSBs) and least significant bits (LSBs), with CIM transposable arrays performing forward and backward propagations for MSBs, while regular memory arrays store LSBs for weight updates. The impact of ADC resolution on training accuracy is analyzed, and the MINT architecture is evaluated using a convolutional VGG-like network on the CIFAR-10 dataset, demonstrating high accuracy and energy efficiency compared to baseline CIM architectures.

To minimize execution time, energy consumption, and overall cost, [

16] highlights the importance of hardware-mapping co-optimization in multi-accelerator systems and the need for exploring the multi-objective space. It introduces MOHaM, a framework for multi-objective hardware-mapping co-optimization. MOHaM addresses these requirements and provides an open-source infrastructure for designing multi-accelerator systems with known workloads. MOHaM utilizes a specialized multi-objective evolutionary algorithm to select suitable sub-accelerators, configure them, determine their optimal placement, and map the layers of DNNs spatially and temporally. The framework is evaluated against existing Design Space Exploration (DSE) frameworks and demonstrates Pareto optimal solutions with significant improvements in latency and energy reduction. It introduces custom genetic operators and an optimization algorithm, making it faster and more efficient than exhaustive search methods. The results show substantial latency and energy reductions compared to state-of-the-art approaches.

3.3. Thermally Aware Architecture

The increased integration density and higher power dissipation in dataflow-aware architectures require efficient thermal management techniques to ensure reliable operation and prevent overheating. The design of data-flow-aware manycore architectures must therefore tackle thermal challenges.

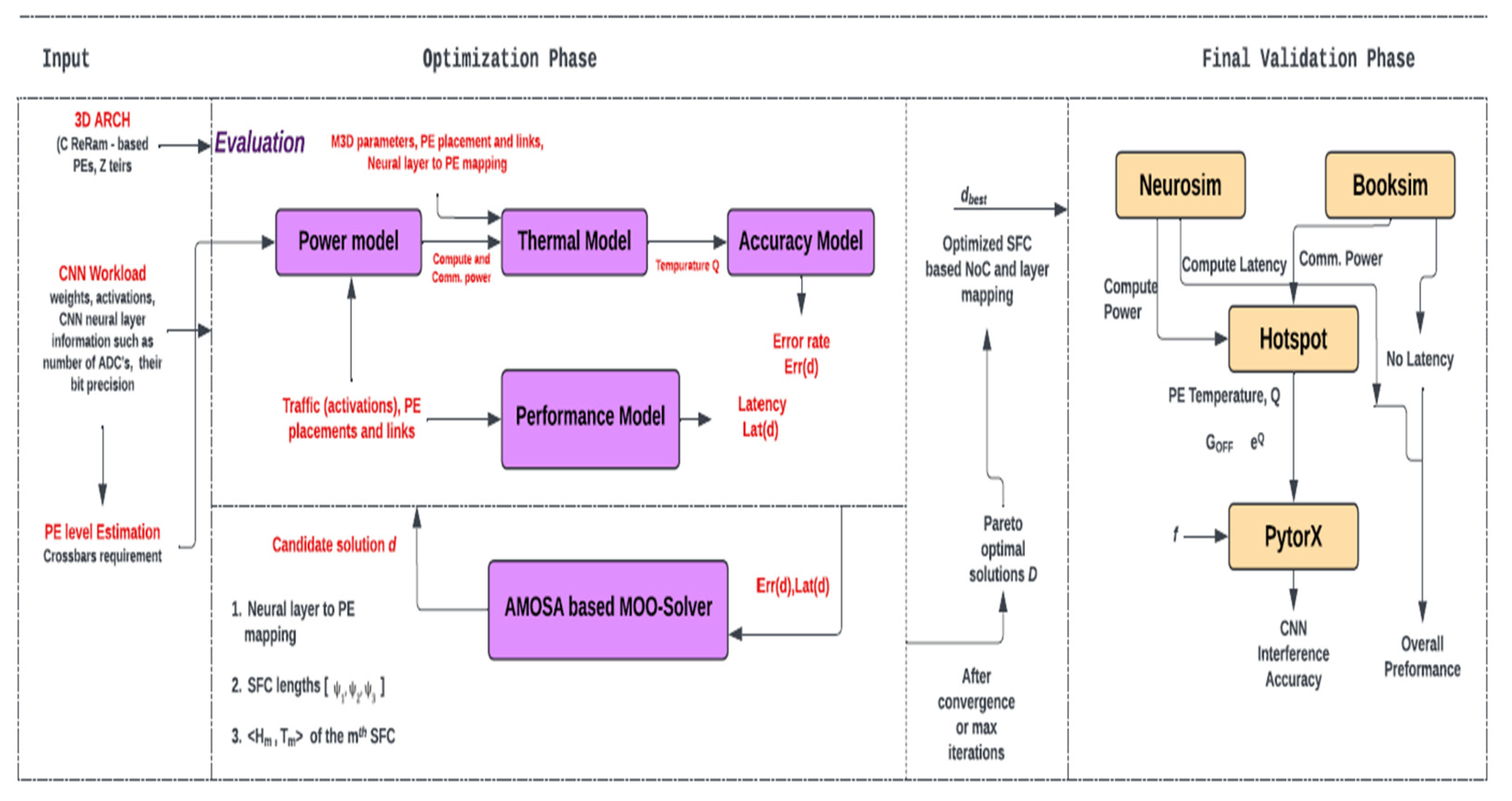

One such study in [

3] introduces a thermally optimized dataflow-aware monolithic 3D (M3D) Network-on-Chip (NoC) architecture for enhancing Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) inferencing. The proposed design aims to integrate multiple processing-in-memory (PIM) cores using Resistive random-access memory (ReRAM) technology on a single chip (shown in

Figure 5). It emphasizes the importance of efficient communication in ReRAM-based architectures and underscores the need for an effective network-on-chip (NoC) solution. It focuses on the concept of mapping CNN layers to ReRAM-based PEs and the significance of maintaining contiguity among PEs to minimize communication latency. It discusses the use of space-filling curves (SFCs) to achieve dataflow-awareness in designing the NoC architecture. More importantly, it addresses the thermal constraints of ReRAMs, particularly the impact of temperature on conductance and inference accuracy. It emphasizes the importance of avoiding thermal hotspots and distributing high-power consuming cores effectively in the 3D architecture.

In [

2], Floret is mentioned as an SFC-enabled network-on-interposer (NoI) topology for 2.5D chiplet-based integration, which achieves high performance by mapping neural layers of CNN models to contiguous chip-lets. It is stated that Floret outperforms other existing NoI architectures. However, [

3] introduces TEFLON, which is described as a thermally efficient dataflow-aware monolithic 3D (M3D) NoC architecture designed to accelerate CNN inferencing without creating thermal bottlenecks. TEFLON is claimed to reduce the Energy-Delay-Product (EDP) and improve inference accuracy compared to performance-optimized SFC-based counterparts.

It is also observed in this study that CNNs like GN and RN34* exhibit higher reduction in Energy-Delay-Product (EDP) compared to linear VGG CNNs such as VGG11, VGG19, VGG19*, and VGG16*. This is attributed to the presence of additional bypass links for the CNN neural layers that are spatially split among multiple processing elements (PEs) in GN and RN34*. These additional bypass links contribute to improved efficiency and reduced energy consumption in the inference process, resulting in higher EDP reduction compared to the linear VGG CNNs.

(The asterisk (*) next to the CNN models (GN, RN34, VGG19, VGG19, VGG16) indicates that there might be some variations or modifications to the original models.)

A comparison of inference accuracy on the CIFAR-10 dataset is made between different implementations:

(a) Software-only implementation without any impact of thermal noise.

(b) Floret on a 100 PE system size, considering the impact of reduced noise margin and thermal noise, with varying PE frequency (10 MHz and 100 MHz).

It indicates that the impact of thermal noise on the inference accuracy at 100 MHz is significant on Floret for all the CNNs. For instance, the inference accuracy of the RN34 model in the Floret-enabled NoC drops by 13.4% compared to the software-only implementation. On the other hand, TEFLON-enabled NoC shows more resilience to thermal noise even at high frequencies, with an average accuracy loss ranging from 0.5% to 2% only.

Another study in [

4] also discusses a design methodology for a heterogeneous 3D NoC that handles the communication requirements between CPUs and GPUs efficiently while reducing thermal issues caused by high power density. It highlights the challenges of training CNNs on heterogeneous manycore platforms and emphasizes the benefits of using 3D ICs and NoCs in improving performance and reducing data transfer latency. It discusses the need to optimize both performance and thermal characteristics in manycore systems and explores the role of CPU, GPU, and memory controller placement in achieving better performance and temperature profiles. The authors present their proposed design methodology and evaluate its effectiveness in reducing temperature while maintaining performance. They conduct experiments using LeNet and CIFAR CNNs and demonstrate a significant reduction in maximum temperature with only a minimal degradation in the full-system energy-delay product compared to traditional 3D NoCs optimized solely for performance.

To gain insights into various PIM architectures, challenges, and proposed solutions, refer to

Table 2.

3.4. Processing-in-Memory Systems Applications

3.4.1. Graph Neural Networks

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are machine learning models used for analyzing graph-structured data. The execution of GNNs involves both compute-intensive and memory-intensive operations, with the latter being a significant bottleneck due to data movement between memory and processors. PIM systems aim to alleviate this bottleneck by integrating processors close to or inside memory arrays.

[

5] discusses the acceleration of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) on Processing-In-Memory (PIM) systems by introducing PyGim, an ML framework designed to accelerate GNNs on real PIM systems. It proposes intelligent parallelization techniques for memory-intensive GNN kernels and develops a Python API for them. The framework enables hybrid execution of GNNs, where compute-intensive and memory-intensive operations are executed on processor-centric and memory-centric systems, respectively.

Figure 6 illustrates the execution of the aggregation step on a real PIM system [

5]. It visualizes the practical implementation of the aggregation process within the context of a PIM system. PyGim is extensively evaluated on a real-world PIM system, outperforming its CPU counterpart and achieving higher resource utilization than CPU and GPU systems. It emphasizes the potential of PIM architectures in accelerating GNNs and presents several key innovations. These include the Combination of Accelerators (CoA) scheme, which utilizes different accelerators for compute-intensive and memory-intensive operations, and Hybrid Parallelism (HP) techniques for efficient parallelization of GNN aggregation on PIM systems. A PIM backend is developed, integrated with PyTorch, and made available through a user-friendly Python API. The evaluation of PyGim on a commercial PIM system demonstrates its superior performance compared to CPU-based approaches. PyGim is intended to be open-sourced to facilitate the widespread use of PIM systems in GNN applications.

There is another study in [

8] that discusses the challenges of training Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) on large real-world graph datasets in edge-computing scenarios. It also proposes the use of Resistive Random-Access Memory (ReRAM)-based Processing-in-Memory (PIM) architectures, which offer energy efficiency and low latency. However, ReRAM-based PIM architectures face issues of low reliability and performance when used for GNN training with large graphs. To overcome these challenges, it introduces a learning-for-data-pruning framework. This framework utilizes a trained Binary Graph Classifier (BGC) to prune subgraphs early in the training process, reducing the size of the input data graph. By reducing redundant information, the overall training process is accelerated, the reliability of the ReRAM-based PIM accelerator is improved, and the training cost is reduced. Experimental results demonstrate that using this data pruning framework, GNN training can be accelerated, the reliability of ReRAM-based PIM architectures can be improved by up to 1.6 times, and the overall training cost can be reduced by 100 times compared to state-of-the-art data pruning techniques.

Another work in [

9] proposes a fault-aware framework for training Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) on edge platforms using Resistive random-access memory (ReRAM)-based processing-in-memory (PIM) architecture. Though ReRAM-based PIM architectures have gained popularity for high-performance and energy-efficient neural network training on edge devices. They leverage the crossbar array structure of ReRAMs for efficient matrix-vector multiplication operations.

However, ReRAMs are prone to hardware faults, particularly stuck-at-faults (SAFs), which make the resistance of ReRAM cells unchangeable. These faults can lead to unreliable training and poor test accuracy. The fault-tolerant methods for neural networks, such as weight pruning and retraining, are not effective in addressing faults in ReRAM-based architectures storing both adjacency and weight matrices. [

9] introduces FARe, a novel fault-tolerant framework specifically designed for ReRAM-based PIM architectures. FARe considers the distribution of SAFs in ReRAM crossbars and maps the graph adjacency matrix accordingly. It also utilizes weight clipping to address faults in the GNN weight matrix. Experimental results demonstrate that FARe outperforms existing approaches in terms of both accuracy and timing overhead. It can restore GNN test accuracy by 47.6% on faulty ReRAM hardware with only a ~1% timing overhead compared to the fault-free counterpart. FARe is model- and dataset-agnostic, making it applicable to different types of GNN workloads and graph datasets.

Graph processing is important for various applications such as social networks, recommendation systems, and knowledge graphs. Traditional architectures face difficulties in handling the irregular data structure of graphs and memory-bound graph algorithms. [

13] discusses the challenges and solutions related to processing large-scale graphs using processing-in-memory (PIM) architectures. It proposes a degree-aware graph partitioning algorithm called GraphB for balanced partitioning and introduces tile buffers with an on-chip 2D-Mesh for efficient inter-node data transfer. GraphB also incorporates datalow design for computation-communication overlap and dynamic load balancing. In performance evaluations, GraphB achieves significant speedups compared to state-of-the-art PIM-based graph processing systems.

3.4.2. NN Inference

Utilizing processing-in-memory (PIM) architectures offers significant potential for enhancing both the performance and energy efficiency of neural network (NN) inference. PIM architectures integrate computational capabilities directly into the memory units, enabling computations to be performed in close proximity to the data. This proximity minimizes data movement and communication overhead, which are typically the major bottlenecks in traditional computing systems. A similar study in [

6] analyzes three state-of-the-art PIM architectures: UPMEM, Mensa, and SIMDRAM. The analysis reveals that PIM architectures significantly benefit memory-bound NNs. UPMEM shows 23 times the performance of a high-end GPU when the GPU requires memory oversubscription for a general matrix-vector multiplication kernel.

Figure 7 displays the design of the Mensa-G accelerator as depicted in [

6]. It provides a visual representation of the architecture and components of the accelerator. Mensa improves energy efficiency and throughput by 3.0 times and 3.1 times, respectively, compared to the Google Edge TPU for 24 Google edge NN models. SIMDRAM outperforms a CPU/GPU by 16.7 times and 1.4 times for three binary NNs. It concludes that the ideal PIM architecture for NN models depends on the specific attributes of the model, considering the inherent design choices. It emphasizes the need for programming models and frameworks that can unify the benefits of different PIM architectures into a single heterogeneous system. PIM is identified as a promising solution to improve the performance and energy efficiency of various NN models.

[

17] discusses the exploration and characterization of a commercial Processing-in-Memory (PIM) technology known as UPMEM-PIM. It highlights the need for PIM architectures to address the growing demand for memory-intensive workloads in areas such as scientific computing, graph processing, and machine learning. It mentions the challenges faced by PIM, including programmability and flexible parallelization. UPMEM-PIM is identified as a general-purpose PIM technology that offers programmability and flexibility for parallel programming. General-purpose PIM designs, like UPMEM-PIM, have the potential to become important computing devices as their hardware and software stack matures.

[

21] presents a study on accelerating reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms using Processing-In-Memory (PIM) systems. RL is the process through which an agent learns optimal behavior by interacting with datasets to maximize rewards. However, RL algorithms face performance challenges when dealing with extensive and diverse datasets, leading to memory-bound bottlenecks and high execution latencies. PIM computing paradigms, which perform computations inside memory devices, can address these issues. The work in [

21] introduces SwiftRL, a framework that explores the potential of real-world PIM architectures to accelerate RL workloads and their training phases. It contributes a roofline model highlighting the memory-bound nature of RL workloads, presents the benefits of in-memory computing systems, demonstrates scalability tests on thousands of PIM cores, compares performance with traditional CPU and GPU implementations, and provides open-source PIM implementations of RL training workloads.

4. Necessity of Cyber Security in PIM

Deep neural networks (DNNs) have revolutionized various fields, including computer vision, natural language processing, and pattern recognition. However, with the increasing adoption of DNNs in critical applications, cybersecurity has emerged as a significant concern. This section explores the challenges and opportunities in enhancing cybersecurity in deep neural networks, drawing insights from recent research papers and industry practices.

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms, such as large language models, has led to increased computing demands in data centers. This growth in AI capabilities has expanded the attack surface for cybercriminals, who exploit vulnerabilities in DNN architectures and training processes. Understanding the evolving threat landscape is crucial for developing effective cybersecurity measures.

Adversarial attacks pose a significant threat to the integrity and reliability of DNNs. These attacks involve manipulating input data through imperceptible perturbations, causing DNNs to make incorrect predictions or misclassify inputs. Defending against adversarial attacks requires robust training methodologies, such as defensive distillation and adversarial training, and the development of adversarial defense mechanisms.

Deep neural networks trained on proprietary datasets can be vulnerable to model stealing attacks. Malicious actors can extract sensitive information from deployed models, including proprietary algorithms, training data, and trade secrets. Protecting intellectual property within DNN models necessitates the implementation of secure model sharing and deployment techniques, such as watermarking and encryption.

Deep learning models often require large amounts of data for training, raising concerns regarding privacy and data leakage. Adversaries may attempt to extract sensitive information by exploiting vulnerabilities in the training process or by intercepting data during inference. Implementing privacy-preserving techniques, such as differential privacy and secure multi-party computation, can mitigate these risks and ensure the confidentiality of user data.

As deep neural networks continue to advance and find widespread adoption, addressing cybersecurity challenges becomes paramount. Enhancing cybersecurity in DNNs requires a multi-faceted approach, encompassing robust training methodologies, adversarial defense mechanisms, secure model sharing, privacy preservation, continuous monitoring and patching, and explainable AI techniques. By proactively addressing these challenges and leveraging the opportunities presented in recent research papers and industry practices, the potential of deep neural networks can be harnessed while mitigating the risks associated with cyber threats.

[

22] discusses the use of heterogeneous chip-lets as a solution for enabling large-scale computing in data centers. It highlights the increasing computing demands driven by artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms, particularly large language models. It emphasizes the advantages of heterogeneous computing with domain-specific architectures (DSAs) and chip-lets in scaling up and scaling out computing systems while reducing design complexity and costs compared to traditional monolithic chip designs. It addresses the key challenge of interconnecting computing resources and orchestrating heterogeneous chip-lets. It explores the diversity and evolving demands of different AI workloads and discusses how chip-lets can improve cost efficiency and time to market. Furthermore, it examines challenges related to chip-let interface standards, packaging, security issues, and software programming in chip-let systems. The paper also discusses infrastructure challenges arising from diverse and evolving AI workloads, focusing on the importance of communication and computation in AI task acceleration. It describes the arithmetic intensity and computation-to-communication ratio as metrics to characterize different AI algorithms. The growth disparity between hardware throughput and bandwidth is highlighted, necessitating scalable hardware acceleration systems. Moreover, the paper presents chip-lets as a solution for rapid heterogeneous system development. It explains how chip-lets enable the integration of multiple circuits into chips, addressing limitations in scaling up monolithic ASIC chips such as chip area and yield rate. Chip-lets offer advantages in performance, energy efficiency, cost, and time to market. Examples of chip-let-based products, such as the AMD EPYC CPU processor, are provided to showcase the success of chip-let technology. Overall, the paper provides insights into the challenges, opportunities, and benefits associated with using heterogeneous chip-lets for large-scale computing in the context of AI workloads.

[

23] discusses the importance of social network security and the use of deep convolutional neural networks (DCNN) for topic mining and security analysis. It addresses the increasing concerns regarding network information security in social networks, such as network attacks, data leakage, and theft of confidential information. The research aims to develop a Weibo security topic detection model using DCNN and Big Data technology. The model utilizes the long short-term memory (LSTM) structure in the memory intelligence algorithm to extract Weibo topic information, while the DCNN learns the grammar and semantic information of Weibo topics for in-depth data features. Comparative analysis of the improved DCNN model with other models, such as AlexNet, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and Deep Neural Network (DNN), shows superior accuracy, recall, and F1 value. The experimental results demonstrate that the improved DCNN model achieves a recognition accuracy peak of 96.17% after 120 iterations, outperforming the other models by at least 5.4%. The intrusion detection model also exhibits high accuracy, recall, and F1 value. Furthermore, the improved DCNN security detection model shows lower training and testing time consumption compared to similar approaches in the literature. The research concludes that the improved DCNN model, based on deep learning, exhibits lower delay and good network data security transmission. Overall, the paper emphasizes the significance of timely and effective social network security topic mining and analysis models for ensuring data and information security in social networks. The utilization of DCNN and Big Data technology in this context provides valuable insights for enhancing network security performance and improving the security and transmission of social network data.

[

24] discusses the application of deep learning techniques in the field of cybersecurity. It highlights the challenges faced by computer systems in terms of security and explores how advancements in machine learning, particularly deep learning, can address these challenges. The paper presents three distinct cybersecurity problems: spam filtering, malware detection, and adult content filtering. It describes the use of specific deep learning techniques such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTMs), Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) combined with Transfer Learning to tackle these problems. The experiments conducted show promising results, with an Area Under ROC Curve greater than 0.94 in each scenario, indicating excellent performance. The paper emphasizes the importance of creating future-proof cybersecurity systems in the face of the evolving threat landscape, particularly with the rise of the Internet of Things (IoT). It discusses the potential of deep learning techniques to enhance the effectiveness of security solutions by leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning advancements. In the related works section, the paper reviews previous research on malicious software detection, spam filtering, adult content filtering, and neural network architecture. It highlights the use of neural networks, including convolutional neural networks, in detecting and classifying malware. Various machine learning algorithms such as decision trees, logistic regression, random forests, AdaBoost, artificial neural networks, and convolutional neural networks are discussed in the context of spam detection. Overall, the document provides a comprehensive overview of applying deep learning in cybersecurity, evaluates the status of experiments conducted in spam filtering, malware detection, and adult content filtering, and discusses their simplicity and applicability in real-world environments. It aims to inspire more individuals to explore and utilize the potential of deep learning techniques in addressing cybersecurity challenges.

[

25] aims to detect and protect cloud systems from malicious attacks by developing a new deep learning model. The proposed model utilizes transfer learning and deep neural networks for intelligent detection of attacks in network traffic. It converts the network traffic into 2D preprocessed feature maps, which are then processed using transferred and fine-tuned convolutional layers. The model achieves high classification accuracies, with 89.74% for multiclass and 92.58% for binary classification, as evaluated on the NSL-KDD test dataset. The paper also provides an overview of various state-of-the-art studies and techniques in the field of intrusion detection systems (IDS) using deep learning. These include models based on CNN, LSTM, autoencoders, and other deep learning architectures. Different datasets such as NSL-KDD, KDD Cup’99, and UNSW-NB15 have been utilized for training and evaluating the performance of these models. In addition, the paper mentions the use of techniques like data preprocessing, reinforcement learning, information gain (IG) filter-based feature selection, and swarm-based optimization to enhance the performance of IDS systems. It also discusses the effectiveness of deep learning approaches in improving the accuracy and efficiency of intrusion detection. Overall, the research article highlights the significance of deep transfer learning in addressing the challenges of cyber security, particularly in cloud systems. The proposed model demonstrates promising results in detecting and classifying various types of attacks, contributing to the advancement of cyber security technologies.

[

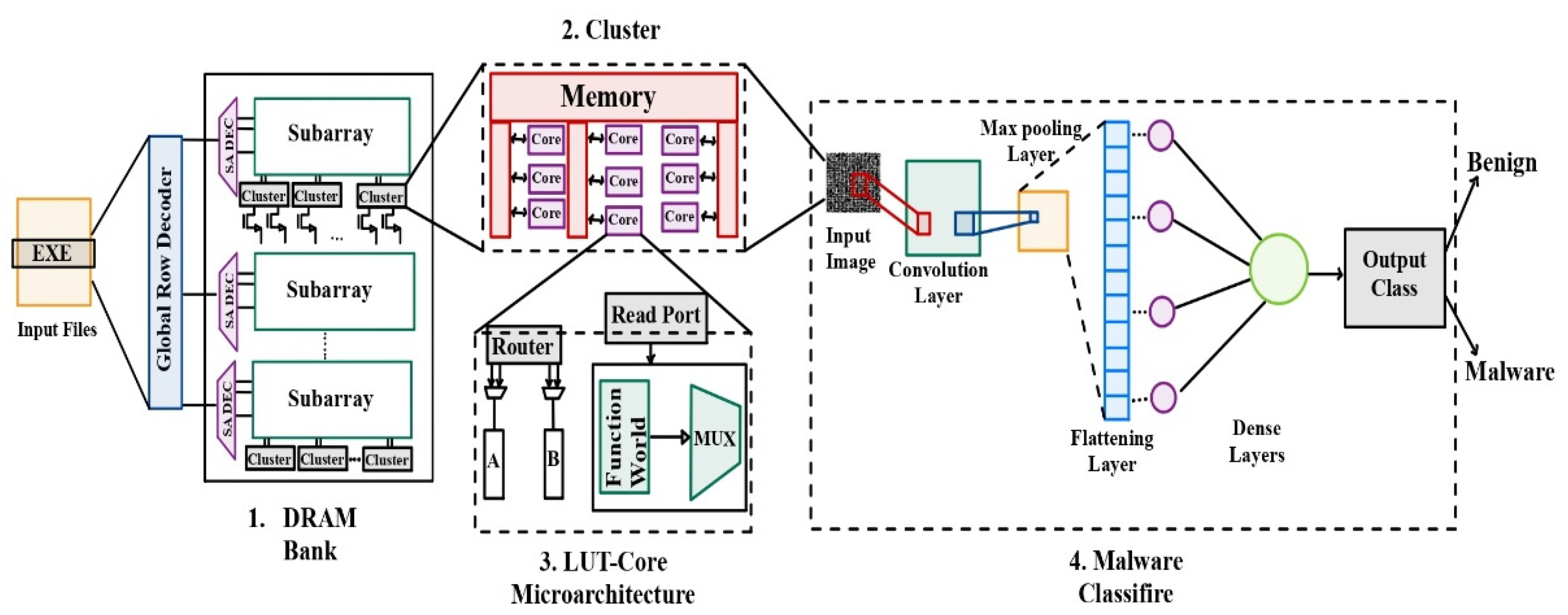

26] discusses the challenges and proposed solutions for improving the efficiency of malware detection using machine learning techniques. The authors address the increasing security threats posed by malware in embedded systems and the need for robust detection methods. The paper introduces the concept of Processing-in-Memory (PIM) architecture, where the memory chip is enhanced with computing capabilities. This architecture minimizes memory access latency and reduces the computational resources required for model updates. The authors propose a PIM-based approach for malware detection, incorporating precision scaling techniques tailored for Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) models.

The proposed PIM architecture(as shown in

Figure 8) demonstrates higher throughput and improved energy efficiency compared to existing Lookup Table (LUT)-based PIM architectures. The combination of PIM and precision scaling enhances the performance of malware detection models while reducing energy consumption. This approach offers a promising solution to the resource-intensive nature of malware detection model updates and contributes to more efficient and sustainable cybersecurity practices. The paper highlights the three-fold contributions of the research: memory-efficient malware detection using in-memory computation, precision scaling to decrease power consumption, and scaling malware samples to lower bit integer types while maintaining high detection accuracy. The related work section discusses various malware detection techniques, including static and dynamic analysis, image processing, and the use of neural networks, emphasizing the advantages and limitations of each approach. It also provides an overview of Processing-in-Memory (PIM) designs and their benefits in terms of throughput and energy efficiency for deep learning applications. Overall, the paper presents a novel approach to improving the efficiency of malware detection through the integration of Processing-in-Memory architecture and precision scaling techniques. The proposed methodology shows promising results and addresses the challenges associated with training models on evolving malware data.

[

27] discusses the security implications of processing-in-memory (PiM) architectures. PiM architectures aim to improve performance and energy efficiency by allowing direct access to main memory, but this can also introduce vulnerabilities. It introduces IMPACT, a set of high-throughput timing attacks that exploit PiM architectures to establish covert and side channels. It highlights two covert-channel attack variants that leverage PiM architectures to achieve high-throughput communication channels. It also presents a side-channel attack on a DNA sequence analysis application that leaks private characteristics of a user’s sample genome. The results show significant improvements in communication throughput compared to existing covert-channel attacks. It discusses the challenges and limitations of traditional defense mechanisms against PiM-based attacks and proposes potential countermeasures. It evaluates two defense mechanisms and analyzes their performance and security trade-offs.

Refer to

Table 3 for an overview of papers addressing the importance of cybersecurity in Processing-in-Memory (PIM) systems. It offers insights into different approaches and perspectives taken by researchers to tackle security challenges associated with PIM technologies.

Overall, this section provides insights into the challenges, opportunities, and benefits associated with cybersecurity measures in various domains, including deep neural networks, large-scale computing, social media platforms, and cloud systems. It highlights the importance of robust techniques and advanced technologies in protecting against cyber threats and preserving data security.

5. Summary of the Review

This article provides a comprehensive review of the latest advancements in processing-in-memory (PIM) techniques for deep learning applications. It addresses the limitations of traditional von Neumann architectures and highlights the benefits of chiplet-based designs and PIM in terms of scalability, modularity, flexibility, performance, and energy efficiency.

The article begins by discussing the challenges faced by monolithic chip architectures and how chiplet-based designs offer improved scalability and resource utilization. It then delves into the concept of processing-in-memory, which aims to overcome the memory bottleneck by integrating computational units directly into the memory subsystem. PIM architectures reduce data movement, minimize latency, and improve energy efficiency by performing computations in close proximity to the data. Various memory technologies, such as SRAM, DRAM, ReRAM, and PCM, can be leveraged in PIM architectures.

The review emphasizes the significance of dataflow-awareness, communication optimization, and thermal considerations in designing PIM-enabled manycore architectures. It explores different machine learning workloads and their specific dataflow requirements. The document also presents a heterogeneous PIM system for energy-efficient neural network training and discusses thermally efficient dataflow-aware monolithic 3D NoC architectures for accelerating CNN inferencing.

There are several areas of future research and development in the field of processing-in-memory architectures for deep neural networks. Some potential future directions include:

Exploring advanced memory technologies: Further investigation into emerging memory technologies, such as memristors or spintronics, can offer new opportunities for enhancing the performance and energy efficiency of PIM architectures.

Optimizing communication and interconnectivity: Continued research on efficient on-chip interconnection networks and communication protocols can further reduce data movement and latency in PIM architectures.

Integration with emerging technologies: Exploring the integration of PIM architectures with other emerging technologies, such as neuromorphic computing or quantum computing, can lead to novel and more efficient computing systems.

Security and privacy considerations: Addressing the cybersecurity challenges associated with deep neural networks and PIM architectures, including adversarial attacks, model stealing attacks, and privacy concerns, is crucial for the widespread adoption of these technologies.

Hardware-software co-design: Further exploration of hardware-software co-design approaches can enable better optimization and utilization of PIM architectures, considering the unique characteristics of deep learning workloads.

Real-world application deployment: Conducting practical experiments and case studies to evaluate the performance, energy efficiency, and scalability of PIM architectures in real-world deep learning applications can provide valuable insights for their adoption.

Table 4 provides a comprehensive collection of papers that delve into the topic of Processing-in-Memory (PIM). It encompasses discussions on architecture, challenges, proposed solutions, and future scope, as explored in this review.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, this comprehensive review has explored the advancements in processing-in-memory (PIM) techniques for deep learning applications. The limitations of monolithic chip designs in deep learning, such as area, yield, and on-chip interconnection costs, have been addressed, and chiplet-based architectures have emerged as a promising solution. These architectures offer improved scalability, modularity, and flexibility, allowing for better yield and reduced costs. Furthermore, chiplet-based designs enable efficient utilization of resources by distributing the computational workload across multiple chiplets, resulting in enhanced performance and energy efficiency.

Processing-in-memory (PIM) techniques have gained significant attention as they aim to overcome the memory bottleneck in deep learning. By integrating processing units directly into the memory subsystem, PIM architectures minimize data movement, reduce latency, and improve energy efficiency. The review has highlighted the potential of PIM architectures in leveraging emerging memory technologies like resistive random-access memory (ReRAM) to achieve high-performance and energy-efficient acceleration of deep learning tasks.

The importance of dataflow-awareness and communication optimization in the design of PIM-enabled manycore platforms has been emphasized. Different machine learning workloads require tailored dataflow-awareness to minimize latency and improve energy efficiency. Additionally, the challenges associated with on-chip interconnection networks, thermal constraints, and scalable communication in chiplet-based architectures have been discussed.

A heterogeneous PIM system for energy-efficient neural network training has been presented, combining fixed-function arithmetic units and programmable cores on a 3D die-stacked memory. This approach provides a unified programming model and runtime system for efficient task offloading and scheduling. The significance of programming models that accommodate both fixed-function logics and programmable cores has been highlighted.

The review has also explored thermally efficient dataflow-aware monolithic 3D (M3D) NoC architectures for accelerating CNN inferencing. By integrating processing-in-memory cores using ReRAM technology and designing efficient network-on-chip (NoC) architectures, data movement can be reduced. The advantages of TEFLON (Thermally Efficient Dataflow-Aware 3D NoC) over performance-optimized space-filling curve (SFC)-based counterparts in terms of energy efficiency, inference accuracy, and thermal resilience have been highlighted.

Overall, the advancements in processing-in-memory techniques have the potential to revolutionize deep learning hardware. These approaches offer scalability, flexibility, improved performance, and energy efficiency, addressing the challenges faced by traditional monolithic chip designs. By leveraging the benefits of processing-in-memory techniques, researchers and engineers can pave the way for enhanced deep learning capabilities and contribute to the development of efficient and powerful AI hardware.

References

- Liu, J.; Zhao, H.; Ogleari, M.A.; Li, D.; Zhao, J. Processing-in-Memory for Energy-Efficient Neural Network Training: A Heterogeneous Approach. In Proceedings of the 51st Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO-51); IEEE Press: 655-668, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Narang, G.; Doppa, J.R.; Ogras, U.; Pande, P.P. Dataflow-Aware PIM-Enabled Manycore Architecture for Deep Learning Workloads. arXiv preprint. arXiv:abs/2403.19073, 2024.

- Narang, G.; Ogbogu, C.; Doppa, J.; Pande, P. TEFLON: Thermally Efficient Dataflow-Aware 3D NoC for Accelerating CNN Inferencing on Manycore PIM Architectures. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. Just Accepted. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Joardar, B.K.; Choi, W.; Kim, R.G.; Doppa, J.R.; Pande, P.P.; Marculescu, D.; Marculescu, R. 3D NoC-Enabled Heterogeneous Manycore Architectures for Accelerating CNN Training: Performance and Thermal Trade-Offs. In Proceedings of the Eleventh IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Networks-on-Chip, 19 October 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Giannoula, C.; Yang, P.; Vega, I.F.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.X.; Luna, J.G.; Sadrosadati, M.; Mutlu, O.; Pekhimenko, G. Accelerating Graph Neural Networks on Real Processing-In-Memory Systems. arXiv preprint 26 February 2024. arXiv:2402.16731.

- Oliveira, G.F.; Gómez-Luna, J.; Ghose, S.; Boroumand, A.; Mutlu, O. Accelerating Neural Network Inference with Processing-in-DRAM: From the Edge to the Cloud. IEEE Micro 2022, 42, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Luna, J.; El Hajj, I.; Fernandez, I.; Giannoula, C.; Oliveira, G.F.; Mutlu, O. Benchmarking Memory-Centric Computing Systems: Analysis of Real Processing-in-Memory Hardware. In Proceedings of the 2021 12th International Green and Sustainable Computing Conference (IGSC), 18 October 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbogu, C.; Joardar, B.K.; Chakrabarty, K.; Doppa, J.; Pande, P.P. Data Pruning-enabled High Performance and Reliable Graph Neural Network Training on ReRAM-based Processing-in-Memory Accelerators. ACM Transactions on Design Automation of Electronic Systems 2024.

- Dhingra, P.; Ogbogu, C.; Joardar, B.K.; Doppa, J.R.; Kalyanaraman, A.; Pande, P.P. FARe: Fault-Aware GNN Training on Re-RAM-based PIM Accelerators. arXiv preprint 19 January 2024. arXiv:2401.10522.

- Lee, S.; Kang, S.H.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Lee, E.; Seo, S.; Yoon, H.; Lee, S.; Lim, K.; Shin, H.; Kim, J. Hardware Architecture and Software Stack for PIM Based on Commercial DRAM Technology: Industrial Product. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM/IEEE 48th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA), 14 June 2021; pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Joardar, B.K.; Arka, A.I.; Doppa, J.R.; Pande, P.P.; Li, H.; Chakrabarty, K. Heterogeneous Manycore Architectures Enabled by Processing-in-Memory for Deep Learning: From CNNs to GNNs (ICCAD Special Session Paper). In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design (ICCAD), 1 November 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Q.; Wang, Z.; Feng, Z.; Yan, B.; Cai, Y.; Huang, R.; Chen, Y.; Yang, C.L.; Li, H.H. Lattice: An ADC/DAC-less ReRAM-Based Processing-in-Memory Architecture for Accelerating Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 57th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), 20 July 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, S.; Kang, Y. Load Balanced PIM-Based Graph Processing. ACM Transactions on Design Automation of Electronic Systems 2024.

- Sharma, H.; Mandal, S.K.; Doppa, J.R.; Ogras, U.Y.; Pande, P.P. SWAP: A Server-Scale Communication-Aware Chiplet-Based Manycore PIM Accelerator. IEEE Trans. Comput. Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2022, 41, 4145–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Huang, S.; Peng, X.; Yu, S. MINT: Mixed-Precision RRAM-Based In-Memory Training Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), 12 October 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.; Russo, E.; Palesi, M. Multi-Objective Hardware-Mapping Co-Optimisation for Multi-DNN Workloads on Chiplet-Based Accelerators. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2024, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, B.; Kim, T.; Lee, D.; Rhu, M. Pathfinding Future PIM Architectures by Demystifying a Commercial PIM Technology. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA), 2 March 2024; pp. 263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, A.; Castro, D.; Romano, P. PIM-STM: Software Transactional Memory for Processing-In-Memory Systems. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, 27 April 2024; Volume 2, pp. 897–911. [Google Scholar]

- Bavikadi, S.; Sutradhar, P.R.; Ganguly, A.; Dinakarrao, S.M.P. Reconfigurable Processing-in-Memory Architecture for Data Intensive Applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 37th International Conference on VLSI Design and 2024 23rd International Conference on Embedded Systems (VLSID), IEEE; 2024; pp. 222–227. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yi, S.; Peng, L.; Pan, X.; Sun, G.; Luo, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J. StreamPIM: Streaming Matrix Computation in Racetrack Memory. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA), 2 March 2024; pp. 297–311. [Google Scholar]

- Gogineni, K.; Dayapule, S.S.; Gómez-Luna, J.; Gogineni, K.; Wei, P.; Lan, T.; Sadrosadati, M.; Mutlu, O.; Venkataramani, G. SwiftRL: Towards Efficient Reinforcement Learning on Real Processing-In-Memory Systems. arXiv preprint 7 May 2024. arXiv:2405.03967.

- Yang, Z.; Ji, S.; Chen, X.; Zhuang, J.; Zhang, W.; Jani, D.; Zhou, P. Challenges and Opportunities to Enable Large-Scale Computing via Heterogeneous Chiplets. In Proceedings of the 2024 29th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference (ASP-DAC), 22 January 2024; pp. 765–770. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. Social Media Platform-Oriented Topic Mining and Information Security Analysis by Big Data and Deep Convolutional Neural Network. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 199, 123070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-García, A.; Rego, A.Z.; Pastor-López, I.; Sanz, B.; Tellaeche, A.; Gaviria, J.; Bringas, P.G. Deep Learning Applications on Cybersecurity: A Practical Approach. Neurocomputing 2024, 563, 126904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çavuşoğlu, Ü.; Akgun, D.; Hizal, S. A Novel Cyber Security Model Using Deep Transfer Learning. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 3623–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasarapu, S.; Bavikadi, S.; Dinakarrao, S.M. Empowering Malware Detection Efficiency within Processing-in-Memory Architecture. arXiv preprint 12 April 2024. arXiv:2404.08818.

- Kanellopoulos, K.; Bostanci, F.; Olgun, A.; Yaglikci, A.G.; Yuksel, I.E.; Ghiasi, N.M.; Bingol, Z.; Sadrosadati, M.; Mutlu, O. Amplifying Main Memory-Based Timing Covert and Side Channels using Processing-in-Memory Operations. arXiv preprint 17 April 2024. arXiv:2404.11284.

- Asad, A.; Kaur, R.; Mohammadi, F. A Survey on Memory Subsystems for Deep Neural Network Accelerators. Future Internet 2022, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Mohammadi, F. Power Estimation and Comparison of Heterogeneous CPU-GPU Processors. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 25th Electronics Packaging Technology Conference (EPTC), 5 December 2023; pp. 948–951. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, R.; Mohammadi, F. Comparative Analysis of Power Efficiency in Heterogeneous CPU-GPU Processors. In Proceedings of the 2023 Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, & Applied Computing (CSCE), 24 July 2023; pp. 756–758. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, R.; Saluja, N. Comparative Analysis of 1-bit Memory Cell in CMOS and QCA Technology. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Flexible Electronics Technology Conference (IFETC), Ottawa, ON, Canada; 2018; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safayenikoo, P.; Asad, A.; Fathy, M.; Mohammadi, F. An Energy Efficient Non-Uniform Last Level Cache Architecture in 3D Chip-Multiprocessors. In Proceedings of the 2017 18th International Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ISQED), Santa Clara, CA, USA; 2017; pp. 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, A.; AL-Obaidy, F.; Mohammadi, F. Efficient Power Consumption using Hybrid Emerging Memory Technology for 3D CMPs. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 11th Latin American Symposium on Circuits & Systems (LASCAS), San Jose, Costa Rica; 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, A.; Kaur, R.; Mohammadi, F. Noise Suppression Using Gated Recurrent Units and Nearest Neighbor Filtering. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), Las Vegas, NV, USA; 2022; pp. 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).