1. Introduction

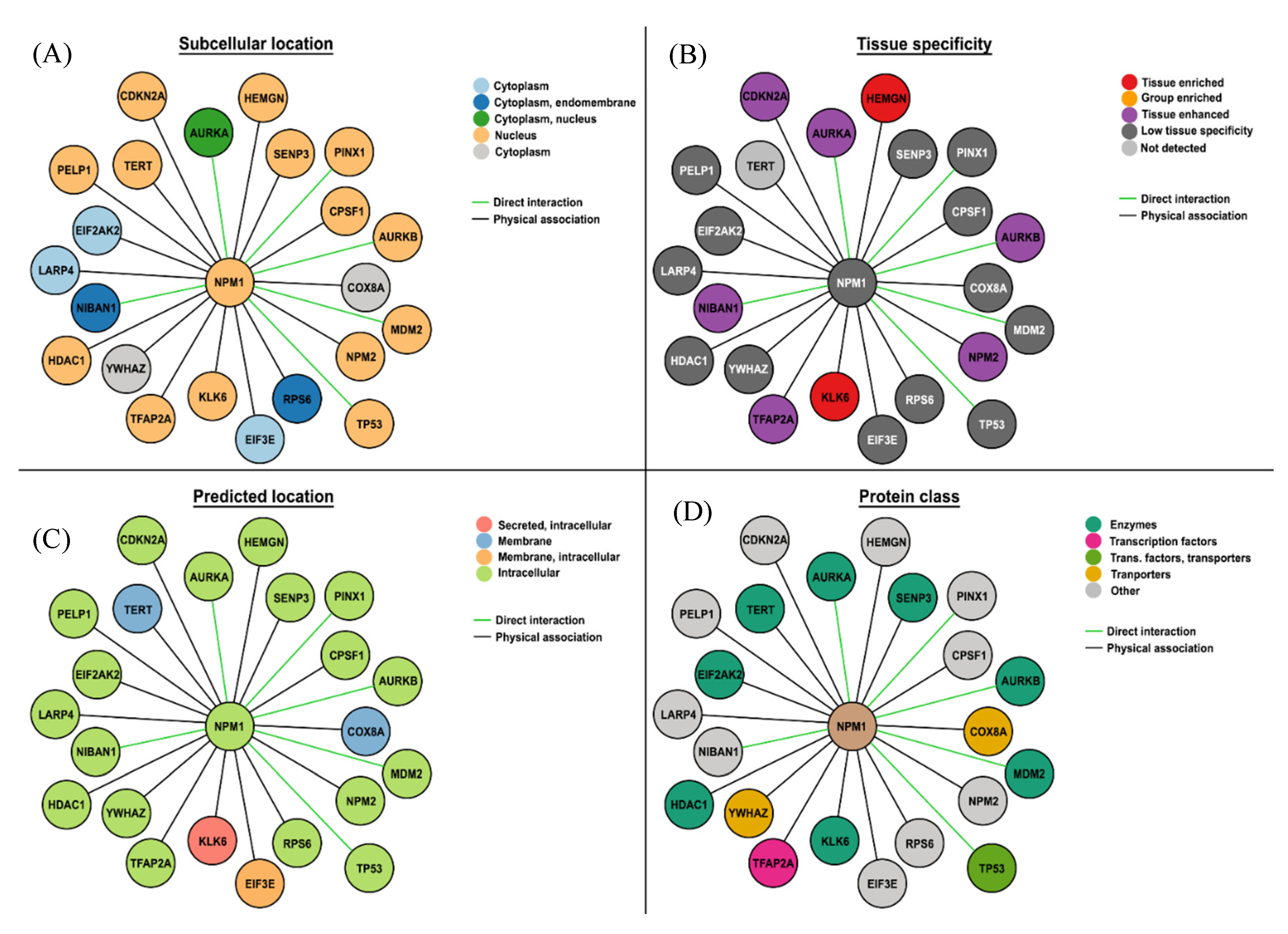

Nucleophosmin 1 (NPM1.1 or NPM1) is a mainly nucleolar protein that shuttles between nucleoli, nucleoplasm and cytoplasm chaperoning nucleic acids and proteins. It is expressed abundantly in all tissues [1] and plays a crucial role in cell cycle control, centrosome duplication, ribosome maturation and export, as well as cellular responses to a variety of stress signals. NPM1 is altered by overexpression, chromosomal translocations and mutations in solid and hematological cancers (reviewed in [2]). In hematological malignancies the NPM1 gene is frequently combined with other genes to give fusion proteins that retain the oligomerization domain in the N-terminal of NPM1 including NPM1-RARα in a subset of acute promyelocytic leukemia patients [3] and the rare NPM1-MLF1 [4] translocation which is associated with the progression of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). 99% of the point mutations in NPM occur in exon 12 and mutation A, a duplication of TCTG, is the most common followed by mutation D, an insertion of CCTG, between nucleotides 960 and 961. These point mutations, although different, almost always lead to the same outcome, a frameshift that creates a C-terminus sequence with a disrupted nucleolar localization signal (NoLS) and a third nuclear export sequence (NES). As a consequence, NPM1 no longer predominantly resides in the nucleolus but relocates to the cytoplasm [5–8] where it is referred to as NPMc+. NPMc+ accumulation in the cytoplasm can be detected by immunocytochemistry [9] and qPCR which allows the monitoring of molecular minimal residual disease (MRD) in patients [10]. NPM1c+ interacts with a number of other proteins (

Figure 1), including itself, mostly using its N-terminal domain (NTD)(reviewed in [11]).

Alterations in NPM1 are considered a gate-keeper mutation, one of the first hits in the process of leukemogenesis (reviewed in [12]). AML patients with a nucleophosmin-1 mutation (AML NPM1

mut) are recognized as a separate entity in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of AML [

13,

14], since NPM1

mut are a founder genetic event, that is rare in MDS [

15] with distinct genetic, pathological, immunophenotypic and clinical characteristics (

Table 1). In this review we will discuss NPM1

mut AML in the context of immunotherapeutic approaches that have been developed to treat it.

2. AML NPM1mut and Prognosis

Survival rates for patients with AML are unfortunately still low. The 7+3 regimen achieves an estimated 5-year survival rate of 30% to 35% in younger adult patients (age <60) and 10-15% in older patients (age >60) [16]. Therefore, exploring new therapeutic options, especially for older patients, is crucial to improve survival rates and address risk factors. NPM1

mut are found more commonly in older adult AML patients (over 35 years of age)(

Table 1) and correlate with high white counts and normal karyotypes [17]. They are present in the M1-M6 subtypes (French American British (FAB) classification of AML), but absent in AML M0 and patients with t(8;21), inv(16), t(15;17), or CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-α (CEBPA) mutations [17]. Homeobox (HOX) genes (A4, A5, A6, A7, A9, A10, B2, B3, B5, B6) as well as the HOX-related genes, PBX3 and MEIS1, are upregulated in AML NPM1

mut samples while CD34 mRNA levels are low/absent in AML patients with NPM1

mut.

There are distinct patterns of co-mutations in NPM1mut patients and there are gene–gene interactions that are particularly pronounced, causing patterns of co-incidental mutation defined groups with a favorable, or conversely, adverse prognosis [20]. The concurrence of NPM1mut is twice as frequent in patients with fms-related receptor tyrosine kinase 3-internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) than those with wild-type NPM1 (NPM1WT). This may be explained, by both being caused by replication slippage errors [21] with the belief that NPM1mut precedes FLT3-ITD [8,22]. FLT3-ITD is associated with poor survival in younger (<60 years) but not in older (60-74 years) AML patients, while NPM1mut is associated with good survival in older, but not younger patients [23]. However, patients with NPM1mut but without a FLT3-ITD translocation often have a favorable prognosis [17] including a better overall survival (OS) rate [24].

Angenendt and colleagues [25] conducted a study on a group of over 2,400 AML patients with NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low, who had varying karyotypes and chromosomal abnormalities. The results showed that in patients with NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low AML, unfavorable cytogenetics were linked to a lower 5-year OS rate (52.4%, 44.8%, 19.5% for normal, aberrant intermediate, and adverse karyotype, respectively). This highlights the significant impact of karyotype abnormalities on the survival outcome of NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low AML patients. In patients who have adverse-risk cytogenetics, those with NPM1mut have a similarly poor prognosis as those with NPM1WT and should receive treatment accordingly.

AML NPM1

mut were not found to be associated with event-free survival, OS or probability of relapse at 60 months post-diagnosis but because NPM1

mut were significantly associated with normal karyotypes and the presence of FLT3-ITD (

Table 2) there appears to be a trend towards improved survival in patients in the intermediate risk group without FLT3-ITD but with NPM1

mut (

p=0.05) [17].

Clinical data showed that AML NPM1mut generally correlated with a better prognosis for patients (reviewed in [26]); that may be explained by more robust immune responses against leukemic cells in general and the leukemia stem cell (LSC) fraction in particular. In 2014, Schneider et al. [27] compared LSC-enriched populations in AML patients with and without NPM1 gene alterations. The CD34+CD38− cell fraction’s existence within the LSC pool indicated a connection between the features of LSCs and the presence of NPM1mut. Most diseased cells in NPM1mut AML patients are CD33+ and CD34−; LSC are usually seen in the CD34+CD38− cell fraction. This finding raises important issues about the role of immune surveillance in leukemia progression and underscores the potential therapeutic implications of targeting immune-related pathways. However, additional validation and characterization are required to understand the underlying mechanisms.

3. AML NPM1mut Treatment Strategies

While certain immunotherapeutic methods, such as allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) and donor lymphocyte infusion, are established treatments for AML patients, there are also other potential treatments in development or waiting to be implemented in clinical practice. Many mechanisms and properties are still unclear, suggesting significant potential for immunotherapy in NPM1mut AML.

Given that NPM1mut has a high association with AML and has already been shown to be associated with improved patient survival, it is a desirable target structure for customized immunotherapy approaches especially for patients with chronic MRD or NPM1mut receiving maintenance treatment. In an AML NPM1mut patient in molecular relapse, pre-emptive donor lymphocyte infusion resulted in poly-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses against multiple identified LAAs, including NPM1 #3 [38].

Jäger et al. [39] examined 64 patients with AML NPM1

mut who needed an allogeneic hematopoietic SCT (alloHSCT) due to additional adverse prognostic factors (1st line), and inadequate response to or relapse during or after 2nd line CT were retrospectively analysed. They showed that MRD-negative patients in CR achieve better 2-year progression free survival (PFS) and 2-year OS compared to patients with MRD-positive patients in CR (

Table 3). The best results were obtained by patients who underwent alloHSCT because of a recurrence or chronic illness when relapse was identified molecularly, following CT completion. Compared to patients who relapsed while receiving CT, those who encountered a molecular or hematologic relapse after finishing CT responded well to salvage CT. Following alloHSCT, patients with a second MRD-CR had a high probability of long-term remission. During CT, patients who experienced hematologic relapse had poor survival outcomes [40]. Therefore, alloHSCT in NPM1 AML patients depends on the disease burden, relapse type, and response to CT. AlloHSCT transplantation does not seem to benefit NPM1

mut/FLT3-ITD-negative patients when used as a first-line treatment; nevertheless, further clinical trials are being conducted, and MRD needs to be considered [39].

DiNardo et al. [41] showed that the BCL2 inhibitor, venetoclax, had high response rates and durable remissions associated with NPM1 or IDH2 mutations in older AML patients. Subsequently, Jäger et al. [39] showed in a small number of patients, that hypomethylating agents combined with Venetoclax may be an effective alternative treatment for NPM1mut AML especially where an isocitrate dehydrogenase (NADP+ 2) IDH2-mutation is present. Effective relapse methods are offered, with a particular emphasis on the incidence of mild or moderate graft versus host disease (GvHD), which is most likely caused by an immunological graft versus leukemia (GvL) effect.

Forghieri et al. [42] recently wrote about a promising therapeutic approach involving the use of neoantigen-specific T cells, i.e., genetically engineered T cells, such as CAR-T or TCR-transduced T cells directed against NPM1

mut peptides bound to HLA. In patients with full-blown leukemia, adoptive or vaccine-based immunotherapies may not be very effective, but these strategies, possibly in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), may be promising for maintaining remission or pre-emptively eradicating persistent measurable residual disease (discussed further in

Section 5.3). This also applies to patients who are not eligible for alloHSCT.

4. Immunogenic Mutation Related Targets

Different CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to epitopes originating from mutant NPM1 regions have been identified [43] including two HLA-A2-restricted peptides of NPM1mut, #1 and #3, induced distinct T-cell responses (33% and 44%, respectively). Compared to healthy individuals, NPM1mut AML patients exhibited significantly higher frequencies of CTL responses against peptide #3 (p=0.046). Schneider et al. [27] identified specific T-cell responses in AML against epitopes originating from the mutated region of NPM1. In a survival analysis of 25 patients with AML NPM1mut, we observed that those exhibiting specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell immune responses against one or two immunogenic peptides had a better OS compared to those without such immune responses (p=0.004) [44].

Epitope-based differences in immune responses seem to exist (p=0.026); however, given the limited sample size, caution should be exercised when interpreting this result. Due to the inclusion of older patients (7 of 25 were over 60 years old) and other genetic alterations (FLT3-ITD in 11 of 25 NPM1mut patients), the survival rate of all NPM1mut patients was lower. Subsequently, Schneider et al. [27] isolated LSC-enriched population from both NPM1mut and WT patients, and noted that the frequencies of CD34+CD38- cells in AML NPM1mut samples were significantly lower. They found a number of differentially expressed genes of immunological relevance in these populations, including immunoglobulin superfamily member 10 (p=0.00034), CD96 (p=0.00052) and IL-12 receptor beta 1 (IL12RB1, p=0.000834). These markers are involved in immune mechanisms and antigen presentation, highlighting the potential of immune-based therapies that target this subtype of AML patients to be effective.

Kuželová et al. [45] showed that certain HLA-I alleles were also associated with better OS in AML NPM1mut, indicating a predisposition for an effective anti-AML immune response against NPM1mut based on the MHC presentation of the epitopes. The group found that in a cohort of 63 AML patients with NPM1mut, compared to 94 patients with NPM1WT, there was a significant decrease in HLA-B*07, B*18 and B*40 expression. Kuželová et al. also demonstrated a notable OS advantage for patients with NPM1mut who expressed one of these depleted haplotypes (p=0.02) suggesting HLA-B*07, B*18 and B*40 presentation of NPM1mut epitopes are more effective at generating an immune response than other haplotypes, and hence their absence.

Among the most prevalent leukemia-associated antigens (LAAs) in AML are Wilms’ tumor antigen 1 (WT-1), Proteinase 3, and Receptor for hyaluronan-mediated motility (RHAMM; reviewed in [46]). Cancer-testis antigens (CTAs), such as HAGE and PASD1, are expressed less frequently (23% and 35% respectively) but have disease-specific expression [47,48] with little to no expression in healthy tissues, except in immunologically protected sites. All have been shown to generate antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses from AML patients [49] and peptide vaccination studies investigating these antigens [50–54] revealed immunological and clinically-relevant responses. Greiner et al. [55] examined anti-LAA responses using T-cells from AML NPM1mut and NPM1WT patients. Samples from 13/15 (87%) NPM1mut AML patients showed immune responses against at least one LAA and 9/15 (60%) against all four LAAs (NPM1mut, Preferentially expressed Antigen in Melanoma (PRAME) P300, RHAMM R3 and WT1). In NPM1WT patients no responses were found against the NPM1mut epitope, but responses against the other LAAs were comparable to those of NPM1mut patients, although immune responses varied slightly depending on the antigen and the patient.

5. Monoclonal Antibody Therapies

The standard treatment for AML has remained largely unchanged during the past few decades, which is the standard “7 + 3” regimen and includes a seven-day infusion of cytarabine and a three-day treatment with an anthracycline. It is commonly used to achieve complete remission (CR) and is particularly successful in patients aged 65 years and under. In recent years significant advances in our understanding of the pathogenesis of AML, the development of diagnostic assays and approval of new treatments has led to updates in the standard care for AML patients.

5.1. αCD33

CD33 is primarily a myeloid differentiation antigen with initial expression at the very early stages of myeloid cell development and it is not expressed outside the hematopoietic system or on pluripotent HSCs. FLT3-ITD and NPM1mut were found to have increased CD33 expression in patients. Both antigens are expressed on proliferative blasts and leukemia stem cells (LSC) and dual targeting of CD33 and CD123 may enhance treatment efficacy for AML [56]. Several approaches such as monoclonal antibodies and CAR-T cells have been suggested to target overexpression of CD33 and CD123 on AML blasts. Lintuzumab is humanized IgG1 against CD33 that has shown only modest activity in clinical trials [57–59]. Due to toxicity in the liver and normal hematopoietic cells, the phase 3 trial was terminated [60] reflecting the fact that CD33 is largely expressed on myeloid lineage cells, including progenitor cells as well as on neutrophils, NK cells, a subset of B cells, and Kupffer cells in the liver [61].

Due to the short-term effect of αCD33, caused by its’ rapid internalization when it binds, bivalent antibodies conjugated to toxins have been developed to enhance CD33 efficacy [60]. In 2017, after a decade of controversy, the FDA authorized Gemtuzumab-Ozogamicin (GO), a humanized monoclonal αCD33 antibody coupled with the cytotoxic chemical calicheamicin. When GO binds to CD33, it is internalized and calicheamicin is released, triggering DNA double-strand breaks that cause cell death.

Several trials have shown that augmenting the standard treatment with GO, a conjugate of CD33 antibody and cytotoxin calicheamicin has had promising results. It is recommended that GO is added to the first cycle of standard 7+3 induction therapy, especially for CD33-positive NPM1mut AML [13,62,63]. In the randomized AMLSG 09-09 study for NPM1mut patients, CR rates were similar with and without GO, but relapse-free survival was prolonged to a clinically relevant extent in those patients who achieved a CR [64]. The inclusion of GO in intensive chemotherapy (CT) for NPM1mut AML patients led to a notable decrease in NPM1mut transcript levels throughout all treatment cycles, explaining this significant reduction in relapse rates [65,66].

GO has been approved in conjunction with aggressive treatment for newly diagnosed AML patients [67]. GO was initially designed as a monotherapy with a single 9 mg/m² dose for the first recurrence of CD33+ AML. The CR recovery rate is 13%, with a median recurrence-free survival of 6.4 months. The most common consequences were grade 3 and 4 neutropenia (98%), thrombopenia (99%), and a few veno-occlusive disorders (VOD, 0.9%). In up to 25-35% of patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed/refractory (R/R) AML, GO induced CR or CR with incomplete platelet recovery especially in AML patients with a favorable prognosis [68]. GO also eliminated MRD in extensively treated individuals with a reduced response [69]. GO enhanced the 5-year OS and significantly reduced relapse rates in AML patients with NPM1mut (p=0·0028) [70]. However, combining GO with intensive CT for NPM1 AML patients in randomized AMLSG 09-09 trial (NCT00893399) resulted in a high mortality rate [71]. Patient-administered GO had lower associated relapse rates compared to the standard treatment [71].

5.2. αCD123

Targeting CD123 has been suggested as an AML treatment; however, its efficacy was unsatisfactory except in NPM1mut AML/or patients with a FLT3-ITD mutation. This is because these patients have an LSC population enriched in CD34+/CD38− cells [72]. Using a naked antibody that targeted CD123 (CSL362) caused lysis of the AML cells that expressed CD123 due to the activation of the innate immune system [73]. However in a clinical trial of 40 patients with R/R AML, only two patients had a clinical response [73].

Tagraxofusp (SL-401) is a recombinant αCD123 (IL-3 receptor alpha chain) antibody based on the diphtheria toxin. Following its attachment to CD123 and inhibition of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2), tagraxofusp was internalized. In patients with a blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, a myeloid malignancy with high CD123 expression, SL-401 has led to clinical improvement [74]. To treat CD123-positive AML and MDS, SL-401 has also been used with azacitidine (AZA) or venetoclax/AZA. Three of the four previously untreated MDS patients and eight of the nine AML patients who had not received treatment before achieved CR. It is noteworthy that TP53 mutations were present in three responding MDS patients and two responding AML patients. When paired with venetoclax/AZA in CD123-positive R/R AML, pivekimab sunirine, another αCD123 antibody-drug combination that causes DNA alkylation, produced objective response rates (ORRs) of 51% with promising efficacy [75].

Using a mouse model that targeted both CD33 and CD123 via a bispecific conjugate, LSCs were eliminated through a T-cell dependent mechanism both in-vivo and in-vitro [76]. This model suggests that NPM1mut AML is initiated by CD123+ LSCs [76].

5.3. The immune Checkpoint Inhibitors - αPD-1 and αPD-L1

Checkpoint inhibition targeting the Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1), PDx axis have successfully achieved responses in a number of tumor types, including hematopoietic malignancies (reviewed in [77]). However, responses in AML have shown fewer promising results perhaps reflecting their lower mutation burden. This may explain why recent ex vivo studies may provide evidence that support the use of immunogenic strategies for AML NPM1mut in the presence of an ICI.

A systematic review that compared 19 randomized clinical trials involving 11,379 patients with solid tumors including non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma and gastric urothelial carcinoma [78] showed that αPD-1 treatments (such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab) achieved better OS and PFS compared to αPD-L1 therapeutic antibodies, with no significant difference in safety profiles. The reason is thought to be that αPD-1 can bind PD-1 on T cells, blocking binding of PD-1 to both PD-L1 and PD-L2 ligands on antigen presenting cells (APC; cancer cells) at the same time. However the PD-L1 antibody can only bind PD-L1, so T cells may still be inhibited by the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L2, even when PD-L1 signaling is blocked (reviewed in [79]). The level of PD-L1 on APCs may affect the response of patients to αPD-L1 treatment with PD-L1 low/negative patients having a compensatory increase in PD-L2 levels making the difference in treatment efficacy between αPD-1 and αPD-L1 exacerbated.

Expression of CD34/CD38/CD274 surface markers for LPC/LSCs were evaluated in 20/20 NPM1mut/NPM1wt AML patient samples via flow cytometry analyses. The LSC fraction showed a higher level of PD-L1 expression than the non-LSC fraction. The influence of αPD-1 antibody on these antigen-specific immune responses and the formation of stem-like colonies were assessed as well. It is noteworthy that high PD-L1 expression in NPM1mut patients was detected, especially in the leukemic progenitor compartment. This observation further supports the hypothesis that NPM1-directed immune responses might play an important role in tumor cell rejection, which tumor cells try to escape via expression of PD-L1. Immunogenicity of neoantigens derived from NPM1mut cells with higher PD-L1 expression constitute promising target structures for individualized immunotherapeutic approaches.

In addition, we have previously shown that CD8+-specific LAA-immune responses against PRAME, WT-1, RHAMM or NPM1mut expressing LPC/LSC from AML patients with mutated or wild type NPM1 were similar except for their response to NPM1mut epitopes which were only seen in samples from NPM1mut patients (vidé suprá). We also found that T cell-mediated anti-tumor responses from AML patients were enhanced by the presence of αPD-1 blocking antibody [55]. Along with the expression of PD-1 on LSCs isolated from NPM1mut patients, this suggests that treatment with αPD-1 antibodies combined with immunotherapeutic vaccine approaches could represent new treatment options for this biologically distinct group of patients [55,80].

The immune-modulating drug lenalidomide has been shown to promote anti-tumor immunity including anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative, pro-apoptotic and anti-angiogenicity [81]. The effects of lenalidomide are distinct from CT, hypomethylating agents, or kinase inhibitors, making lenalidomide an attractive agent for use in AML treatment including in combination with existing active agents. Combinations of immunotherapeutic approaches are believed to increase antigen-specific immune responses against leukemic cells including LPC/LSCs. In this study, we used a combination of LAA-peptides with the ICI, αPD-1 (nivolumab), and lenalidomide to enhance the killing of LSC/LPCs ex vivo [82]. We used primary cells from AML patients and observed the T-cell responses of all patients in vitro. Results using the combination of ICI αPD-1 and the immune modulatory drug, lenalidomide, showed enhanced LPC/LSC killing. The effect was greatest against NPM1mut cells when the immunogenic epitope was derived from the mutated region of NPM1 [24]. These studies show that antigen-specific immune responses against leukemic cells as well as LPC/LSC, are enhanced by combinations of immunotherapeutic approaches especially when using a combination of LAA-peptides, the αPD-1 antibody, and one further immunomodulating drug, providing an interesting opportunity to enhance the outcomes in future clinical studies.

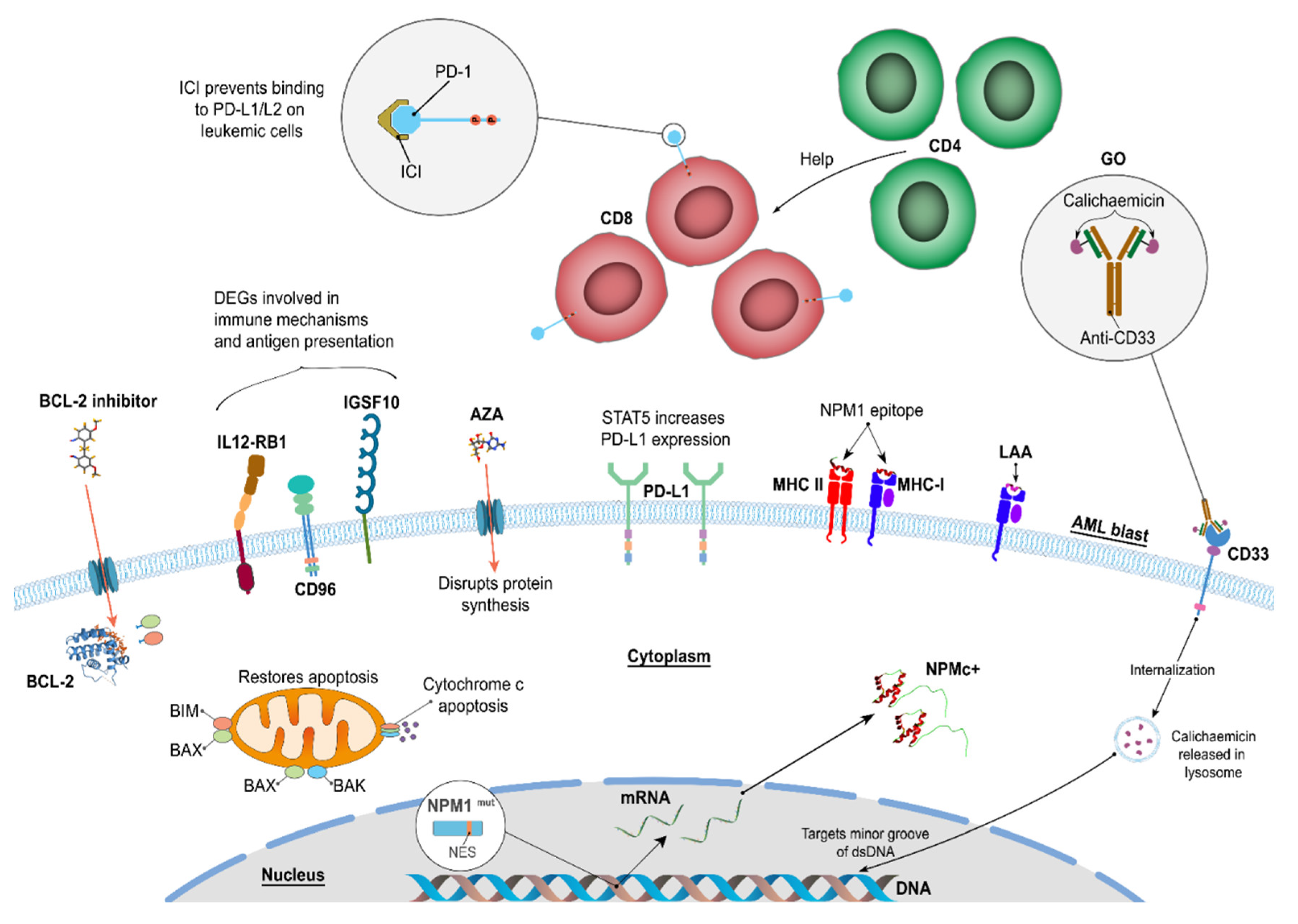

We have recently examined whether all-trans retinoic acid, AZA, αCTLA4 or Lenalidomide, in combination with αPD-1, to determine whether this could further improve the destruction of leukemic cells and also LPC/LSC from AML patients [83](

Figure 2). We identified which LAA (WT-1, PRAME or NPM-1) generated the strongest immune response (as measured by colony-forming immunoassays) and using samples from 20 AML patients with more than 90% leukemic blasts. AZA, in combination with αPD-1, had a pronounced effect on T-cell activation and inhibition of LPC/LSC growth.

Other strategies for immunotherapy, that can be used in combination with PDx need to be considered. One approach is the signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5), which promotes PD-L1 expression by facilitating histone lactylation and driving immunosuppression in AML and thus may benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy. ICI could block the interactions of PD-1 with PD-L1 and thereby enhance the reactivity of CD8+ T cells in the microenvironment when co-culture with STAT5 activated AML cells occurs [84].

Daver et al. found that AZA in combination with αPD-1 resulted in improved OS and an encouraging response rate, particularly in hypomethylating agent (HMA)-naïve and salvage-1 patients [85]. A randomized phase III study and a randomized phase II study of AZA with or without PD-1 inhibitor in first-line elderly AML patients and a randomized trial of PD-1 inhibitor for the eradication of MRD in high-risk AML in remission has started. Clinical and immune biomarker–enriched trials are likely to yield further improved outcomes with HMA in combination with ICI therapies in AML, but this remains to be seen as more study results are made available, and especially for NPM1mut AML patients.

The results suggest that PD-1/PD-L1 in combination with NPM1mut related approaches or other strategies such as STAT5 or HMA may have notable impact on immunotherapeutic outcomes when used for the treatment of AML.

6. Venetoclax and Hypomethylating Agents

The aberration of DNA methylation is a common early event in the pathogenesis of AML, caused by genetic alterations in DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and Ten-Eleven-Translocation (TET) dioxygenases and leading to transcription dysregulation (reviewed in [86]). The standard treatment protocol for newly diagnosed NPM1mut AML patients who are unfit and/or elderly (>60 years), is a combination of venetoclax and HMAs such as AZA which inhibits DNMTs by its incorporation into DNA or low-dose cytarabine (LDAC). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved molecule, venetoclax, targets the NPM1 apoptotic pathway by inhibiting B-cell leukemia/lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) [41,87,88]. The increased sensitivity to venetoclax may be due to an NPM1 mutant-primed impairment in mitochondrial function [89].Venetoclax-based regimens are especially beneficial for NPM1mut AML patients at first diagnosis and in the case of patients who are R/R to treatment. Regarding the effectiveness of venetoclax in NPM1mut AML, the human monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1 which harbors a NPM1mut exhibits increased sensitivity to chemotherapies through the reduction of NF-κB activity and BCL-2/BAX expression [90]. High BCL2 protein levels are associated with improved outcomes in patients with R/R AML or untreated AML, according to predictive indicators for venetoclax sensitivity [91]. However, not every patient has experienced this. A plausible rationale could be that a FLT3-ITD or TP53 deletion in NPM1mut AML patients leads to a mitochondrial malfunction. Moreover, as NPM1mut AML patients age, IDH1/2 mutations develop, which impacts how well venetoclax-based therapy can work [92].

Single-agent HMA or LDAC regimens are often better tolerated and have lower treatment-related mortality rates than conventional CT [93]. With a median survival of 6–10 months, response rates to HMAs alone are modest (10%–50%) [93,94]. Despite its efficacy, relapse within 18 months is a major obstacle of HMA due to drug resistance. One suggested mechanism is that HMA interferes with DNA methylation and in the long term causes a failure of cells to undergo cell cycle arrest [95].

The combination of HMA and venetoclax is suggested to maximize the efficacy of treatment, evading the resistance created through the use of a single agent. In a phase 3 clinical trial (NCT02993523) involving venetoclax plus AZA [41], 66.7% of NPM1mut AML patients experienced CR and incomplete remission with the majority of the patients testing negative for detectable residual disease (MRD). With a predicted two-year survival rate of 70%, the one-year survival rate for elderly individuals with NPM1mut AML surpassed 80%. Usually, 1-2 cycles were required to generate the desired response with a favorable safety profile [41]. Similarly, venetoclax plus LDAC achieved CR and an incomplete CR of 89% and 78%, respectively, in NPM1mut AML patients in trials NCT02287233 and NCT03069352 [96,97]. The combination of venetoclax and HMA is considered to be advanced in AML treatment, dose scheduling and further understanding of the mechanism of action and resistance remain to be explored [41].

7. Discussion

Our review has described treatments that are of particular relevance to AML NPM1mut patients. These patients are unique with a tendency to be over 35 years of age, have a high WCC, have FLT3-ITD, a normal karyotype and upregulated HOX and HOX associated genes and low to absent CD34+ expression on their blasts. Representing one-third of all AML patients, AML NPM1mut has become a separate entity in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of AML, reflecting the patients’ ability to benefit from a targeted treatment strategy. Although treatment of AML patients has changed little until recently [35], the AMLSG09-09 clinical trial showed that the addition of GO can extend relapse-free survival to a clinically relevant extent in CD33+ NPM1mut AML patients who achieve a CR [64,65]. It is notable that most of the diseased cells in NPM1mut AML patients are CD33+ and CD34- even though LSCs are usually seen in the CD34+ and CD38- fraction from AML patients [98]. This suggests that if NPM1mut occurs in the LSC population they are readily depleted by the immune system or that NPM1mut tend to occur in non-LSCs which are more easily seen by the immune response leading to their destruction and the associated improved patient survival.

This is reflected by the association between NPM1mut and improved survival in older (>70 years old) who have normal cytogenetics, independent of other molecular and clinical prognostic indicators, and in contrast to younger patients [99]. The haplotypes HLA-B*07, B*18 and B*40 are depleted in patients with NPM1mut but when patients with NPM1mut express one of these haplotypes OS is increased [45]. The association of NPM1mut with a better prognosis for patients (reviewed in [26]); may be explained by more robust immune responses against leukemic cells in general and the leukemia stem cell (LSC) fraction in particular. Indeed Schneider et al. showed that AML NPM1mut patients harboring CD8+ responses against one of two predicted NPM1mut peptides had better OS that those without [44].

Recently hypomethylating agents and the Bcl-2 inhibitor, venetoclax, combinations gave impressive results in older patients with NPM1mut AML compared to traditional standard-of-care regimens [100]. However, NPM1mut patients with adverse cytogenetics should be treated the same as NPM1WT patients with unfavorable cytogenetics which were linked to a lower 5-year OS rate [25].

Greiner et al. showed that CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from AML patients could respond to peptides from the mutated regions of NPM1 [43]. They found that AML NPM1mut patients with CTL responses against NPM1mut peptide had better overall survival [45] and used LAAs as a specific method of stimulating T-cell immune responses against LSCs and determining which combinations of immunotherapeutics could further enhance AML cell killing [82].

Elevated PD-L1 expression on AML NPM1mut cells (ratio of v1/v2 as determined by qPCR) is associated with poorer survival [101] suggesting that anti-PD-1 treatment could block this signaling pathway, enhance T cell killing of leukemic cells and cause an associated improvement in patient survival. In vitro we showed that the immune checkpoint inhibitor, αPD-1, can enhance killing by LAA-stimulated CTLs [27,55]. Notably, the effect was greatest when T cells from NPM1mut patients were stimulated with NPM1mut peptide suggesting anti-PD-1 antibodies, such as nivolumab, could be used to treat AML NPM1mut. This may reflect the features of AML NPM1mut that are especially associated with successful αPD-1 treatment of cancers including disease stability and a targetable mutation.

We recently examined whether αPD-1, ATRA, AZA, αCTLA4 and/or Lenalidomide were the best treatments to facilitate the destruction of autologous AML colonies in NPM1mut and NPM1WT patients [83]. Results were enhanced in patients with NPM1mut compared with NPM1WT with αPD-1 and AZA providing the most effective T-cell mediated reduction in AML cells in CFI assays. This concurs with our understanding of PDx treatments and when they work best. When CTLs recognize LAAs, their response includes the production of inflammatory cytokines such as IFNγ and the upregulation of PD-1 on their surface. This prevents excessive T-cell responses and limits the immune response. The tumor cells concurrently upregulate PD-L1, inhibiting T-cell responses against them [104]. The blockage of this PD-1/PD-L1 interaction can lead to enhanced tumor killing and improved patient survival rates (reviewed in [103]). However results in the treatment of AML have been mixed, reflecting the features of NPMWT that make AML a poor target for PDx therapies. These include rapidly progressing disease that generates a high tumor, but low mutational burden. However PD-1 is regulated by DNA methylation [104], demonstrating a benefit for HMA and αPD-1 treatment in AML patients. The combination of venetoclax and HMAs has been shown to improve OS and CR compared with AZA alone in patients >75 years of age with previously untreated AML who are ineligible for intensive chemotherapy [41].

It is clear that the development and progression of AML is closely linked to an impaired immune response. Leukemic cells manipulate the tumor microenvironment by creating a niche that directly promotes their survival and makes them resistant to immunotherapeutic strategies. Therefore, innovative strategies for immunotherapies need to be further developed and adapted to overcome the obstacles in the treatment of AML and especially NPM1mut AML [105]. However AML NPM1mut offer several advantages over AML NPMWT, by virtue of their predominance of CD33+ diseased cells and an absence of CD34+ suggesting the target population are not the more difficult to treat CD34+ LSC cells. The presence of a NPM1mut provides a unique target for treatment, whose immunogenicity can be enhanced by treatment strategies that are likely to be enhanced by αPD-1, HMAs and immune modulators.

8. Conclusions and Future Developments

In the hunt for additional NPM1mut peptide targets for future treatment strategies, and ideally the identification of those that are naturally processed and presented, we could use mass spectrometry technologies that have been previously used to identify LAA-associated peptides processed and presented on MHC on CML and AML cells [106,107]. Similar strategies could be used to isolate peptides presented by MHC class I and II molecules on CD34-CD33+ cells from AML NPM1mut patients, especially those associated with improved survival. This would provide naturally occurring epitope(s) for future studies that could be used to enhance NPM1mut-directed immune responses. It may even lend credence to the development of NPM1mut analog peptides, shown previously to stimulate enhanced immune responses against naturally occurring epitopes presented on HLA-A*0201+ AML cells [50].

We have discussed the association between NPM1mut AML and the unique features associated with it. These include normal cytogenetics and enhanced survival in patients >70 years of age. This phenomenon appears to be associated with the capacity of NPM1mut cells to stimulate a CD8+ T cells response against AML cells and lead to relapse-free survival in patients who achieve a CR. More recent studies have built on the standard of care treatment to show that the additional use of hypomethylating agents and Bcl-2 inhibitors can cause improved OS and CR in patients >75 years of age who are not eligible for intensive chemotherapy. Future studies should examine other available treatment options and their efficacy in combination and the clinical trials that provide the proof of principle for a group of elderly AML patients who now have meaningful treatment options.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.; investigation, J.G., M.G. and B.G.; resources, writing—original draft preparation, J.G., M.G., E.M. and B.G.: writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, J.G. and B.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| alloHSCT |

allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant |

LDAC |

low-dose cytarabine |

| AML |

Acute myeloid leukemia |

LPC/LSC |

leukemic progenitor/stem cells |

| APC |

Antigen presenting cells |

MDS |

Myelodysplastic syndrome |

| AZA |

5′-azacitidine |

MRD |

Minimal residual disease |

| BCL-2 |

B-cell leukemia/lymphoma-2 |

NPM1 |

Nucleophosmin 1 |

| CEBPA |

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-α |

OS |

overall survival |

| CR |

Complete remission |

PD-1 |

programmed cell death-1 |

| CT |

Chemotherapy |

PD-L1 |

Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 |

| FAB |

French American British |

PDx |

PD-1/PD-L1 axis |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

PFS |

Progression-free survival |

| FKT3-ITD |

fms related receptor tyrosine kinase 3-internal tandem duplication |

PRAME |

Preferentially expressed Antigen in Melanoma |

| GO |

Gemtuzumab-Ozogamicin |

RHAMM |

Receptor for hyaluronan-mediated motility |

| HMA |

hypomethylating agents |

R/R |

Relapsed/refractory |

| ICI |

immune checkpoint inhibitor |

STAT5 |

Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| LAA |

Leukemia associated antigens |

WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Grisendi, S.; Mecucci, C.; Falini, B.; Pandolfi, P.P. Nucleophosmin and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2006, 6, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarka, J.; Short, N.J.; Kanagal-Shamanna, R.; Issa, G.C. Nucleophosmin 1 Mutations in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.; Nassiri, M. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: A Review and Discussion of Variant Translocations. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2015, 139, 1308–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondi, S.C.; Dube, I.D.; Valentine, M.B.; Mirro, J., Jr.; Watt, H.J.; Larson, R.A.; Bitter, M.A.; Le Beau, M.M.; Rowley, J.D. Clinicopathologic manifestations and breakpoints of the t(3;5) in patients with acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia 1989, 3, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dumbar, T.S.; Gentry, G.A.; Olson, M.O. Interaction of nucleolar phosphoprotein B23 with nucleic acids. Biochemistry 1989, 28, 9495–9501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordell, J.L.; Pulford, K.A.; Bigerna, B.; Roncador, G.; Banham, A.; Colombo, E.; Pelicci, P.G.; Mason, D.Y.; Falini, B. Detection of normal and chimeric nucleophosmin in human cells. Blood 1999, 93, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borer, R.A.; Lehner, C.F.; Eppenberger, H.M.; Nigg, E.A. Major nucleolar proteins shuttle between nucleus and cytoplasm. Cell 1989, 56, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falini, B.; Mecucci, C.; Tiacci, E.; Alcalay, M.; Rosati, R.; Pasqualucci, L.; La Starza, R.; Diverio, D.; Colombo, E.; Santucci, A. Cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. New England Journal of Medicine 2005, 352, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falini, B.; Martelli, M.P.; Bolli, N.; Bonasso, R.; Ghia, E.; Pallotta, M.T.; Diverio, D.; Nicoletti, I.; Pacini, R.; Tabarrini, A. , et al. Immunohistochemistry predicts nucleophosmin (NPM) mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2006, 108, 1999–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillon, R.; Hills, R.; Freeman, S.; Potter, N.; Jovanovic, J.; Ivey, A.; Kanda, A.S.; Runglall, M.; Foot, N.; Valganon, M. , et al. Molecular MRD status and outcome after transplantation in NPM1-mutated AML. Blood 2020, 135, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cela, I.; Di Matteo, A.; Federici, L. Nucleophosmin in Its Interaction with Ligands. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falini, B.; Brunetti, L.; Sportoletti, P.; Martelli, M.P. NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: from bench to bedside. Blood 2020, 136, 1707–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohner, H.; Wei, A.H.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Craddock, C.; DiNardo, C.D.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Godley, L.A.; Hasserjian, R.P. , et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood 2022, 140, 1345–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, S.; Baer, C.; Hutter, S.; Dicker, F.; Fuhrmann, I.; Meggendorfer, M.; Pohlkamp, C.; Kern, W.; Haferlach, T.; Haferlach, C. , et al. Risk assessment according to IPSS-M is superior to AML ELN risk classification in MDS/AML overlap patients defined by ICC. Leukemia 2023, 37, 2138–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimony, S.; Stahl, M.; Stone, R.M. Acute myeloid leukemia: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 2023, 98, 502–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantarjian, H.M.; Kadia, T.M.; DiNardo, C.D.; Welch, M.A.; Ravandi, F. Acute myeloid leukemia: Treatment and research outlook for 2021 and the MD Anderson approach. Cancer 2021, 127, 1186–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhaak, R.G.; Goudswaard, C.S.; van Putten, W.; Bijl, M.A.; Sanders, M.A.; Hugens, W.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Erpelinck, C.A.; Delwel, R.; Lowenberg, B. , et al. Mutations in nucleophosmin (NPM1) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML): association with other gene abnormalities and previously established gene expression signatures and their favorable prognostic significance. Blood 2005, 106, 3747–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Nastou, K.C.; Lyon, D.; Kirsch, R.; Pyysalo, S.; Doncheva, N.T.; Legeay, M.; Fang, T.; Bork, P. , et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, D605–D612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falini, B.; Martelli, M.P.; Bolli, N.; Sportoletti, P.; Liso, A.; Tiacci, E.; Haferlach, T. Acute myeloid leukemia with mutated nucleophosmin (NPM1): is it a distinct entity? Blood 2011, 117, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaemmanuil, E.; Gerstung, M.; Bullinger, L.; Gaidzik, V.I.; Paschka, P.; Roberts, N.D.; Potter, N.E.; Heuser, M.; Thol, F.; Bolli, N. , et al. Genomic Classification and Prognosis in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med 2016, 374, 2209–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrow, J.; Dyer, S.A.; Akiki, S.; Griffiths, M.J. Molecular roulette: nucleophosmin mutations in AML are orchestrated through N-nucleotide addition by TdT. Blood 2019, 134, 2291–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, E.M.; Chan, S.M.; Minden, M.D.; Murphy, T.; Shlush, L.I.; Schimmer, A.D. Biological and clinical consequences of NPM1 mutations in AML. Leukemia 2017, 31, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juliusson, G.; Jadersten, M.; Deneberg, S.; Lehmann, S.; Mollgard, L.; Wennstrom, L.; Antunovic, P.; Cammenga, J.; Lorenz, F.; Olander, E. , et al. The prognostic impact of FLT3-ITD and NPM1 mutation in adult AML is age-dependent in the population-based setting. Blood Adv 2020, 4, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlenk, R.F.; Döhner, K.; Krauter, J.; Fröhling, S.; Corbacioglu, A.; Bullinger, L.; Habdank, M.; Späth, D.; Morgan, M.; Benner, A. Mutations and treatment outcome in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine 2008, 358, 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angenendt, L.; Rollig, C.; Montesinos, P.; Ravandi, F.; Juliusson, G.; Recher, C.; Itzykson, R.; Racil, Z.; Wei, A.H.; Schliemann, C. Revisiting coexisting chromosomal abnormalities in NPM1-mutated AML in light of the revised ELN 2022 classification. Blood 2023, 141, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranieri, R.; Pianigiani, G.; Sciabolacci, S.; Perriello, V.M.; Marra, A.; Cardinali, V.; Pierangeli, S.; Milano, F.; Gionfriddo, I.; Brunetti, L. , et al. Current status and future perspectives in targeted therapy of NPM1-mutated AML. Leukemia 2022, 36, 2351–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, V.; Zhang, L.; Bullinger, L.; Rojewski, M.; Hofmann, S.; Wiesneth, M.; Schrezenmeier, H.; Götz, M.; Botzenhardt, U.; Barth, T.F.E. , et al. Leukemic stem cells of acute myeloid leukemia patients carrying NPM1 mutation are candidates for targeted immunotherapy. Leukemia 2014, 28, 1759–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilliland, D.G.; Griffin, J.D. The roles of FLT3 in hematopoiesis and leukemia. Blood 2002, 100, 1532–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levis, M.; Small, D. FLT3: ITDoes matter in leukemia. Leukemia 2003, 17, 1738–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiah, H.S.; Kuo, Y.Y.; Tang, J.L.; Huang, S.Y.; Yao, M.; Tsay, W.; Chen, Y.C.; Wang, C.H.; Shen, M.C.; Lin, D.T. , et al. Clinical and biological implications of partial tandem duplication of the MLL gene in acute myeloid leukemia without chromosomal abnormalities at 11q23. Leukemia 2002, 16, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohner, K.; Tobis, K.; Ulrich, R.; Frohling, S.; Benner, A.; Schlenk, R.F.; Dohner, H. Prognostic significance of partial tandem duplications of the MLL gene in adult patients 16 to 60 years old with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: a study of the Acute Myeloid Leukemia Study Group Ulm. J Clin Oncol 2002, 20, 3254–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani, S.; Erpelinck, C.; van Putten, W.L.; Valk, P.J.; van der Poel-van de Luytgaarde, S.; Hack, R.; Slater, R.; Smit, E.M.; Beverloo, H.B.; Verhoef, G. , et al. High EVI1 expression predicts poor survival in acute myeloid leukemia: a study of 319 de novo AML patients. Blood 2003, 101, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, T.K.; Wald, D.; Chen, Y.; Vermaat, J.M.; Xiong, Y.; Tse, W. Molecular prognostic markers for adult acute myeloid leukemia with normal cytogenetics. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2009, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döhner, K.; Paschka, P. Intermediate-risk acute myeloid leukemia therapy: current and future. Hematology 2014, 2014, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döhner, H.; Estey, E.; Grimwade, D.; Amadori, S.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Büchner, T.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Larson, R.A. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2017, 129, 424–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preudhomme, C.; Sagot, C.; Boissel, N.; Cayuela, J.M.; Tigaud, I.; de Botton, S.; Thomas, X.; Raffoux, E.; Lamandin, C.; Castaigne, S. , et al. Favorable prognostic significance of CEBPA mutations in patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: a study from the Acute Leukemia French Association (ALFA). Blood 2002, 100, 2717–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani, S.; Erpelinck, C.; Meijer, J.; van Oosterhoud, S.; van Putten, W.L.; Valk, P.J.; Berna Beverloo, H.; Tenen, D.G.; Lowenberg, B.; Delwel, R. Biallelic mutations in the CEBPA gene and low CEBPA expression levels as prognostic markers in intermediate-risk AML. Hematol J 2003, 4, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, S.; Götz, M.; Schneider, V.; Guillaume, P.; Bunjes, D.; Döhner, H.; Wiesneth, M.; Greiner, J. Donor lymphocyte infusion induces polyspecific CD8+ T-cell responses with concurrent molecular remission in acute myeloid leukemia with NPM1 mutation. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2013, 31, e44–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäger, P.; Rautenberg, C.; Kaivers, J.; Kasprzak, A.; Geyh, S.; Baermann, B.-N.; Haas, R.; Germing, U.; Schroeder, T.; Kobbe, G. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and pre-transplant strategies in patients with NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: a single center experience. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 10774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jager, P.; Rautenberg, C.; Kaivers, J.; Kasprzak, A.; Geyh, S.; Baermann, B.N.; Haas, R.; Germing, U.; Schroeder, T.; Kobbe, G. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and pre-transplant strategies in patients with NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: a single center experience. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 10774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Jonas, B.A.; Pullarkat, V.; Thirman, M.J.; Garcia, J.S.; Wei, A.H.; Konopleva, M.; Dohner, H.; Letai, A.; Fenaux, P. , et al. Azacitidine and Venetoclax in Previously Untreated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forghieri, F.; Riva, G.; Lagreca, I.; Barozzi, P.; Bettelli, F.; Paolini, A.; Nasillo, V.; Lusenti, B.; Pioli, V.; Giusti, D. , et al. Neoantigen-Specific T-Cell Immune Responses: The Paradigm of NPM1-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greiner, J.; Ono, Y.; Hofmann, S.; Schmitt, A.; Mehring, E.; Götz, M.; Guillaume, P.; Döhner, K.; Mytilineos, J.; Döhner, H. Mutated regions of nucleophosmin 1 elicit both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2012, 120, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greiner, J.; Schneider, V.; Schmitt, M.; Gotz, M.; Dohner, K.; Wiesneth, M.; Dohner, H.; Hofmann, S. Immune responses against the mutated region of cytoplasmatic NPM1 might contribute to the favorable clinical outcome of AML patients with NPM1 mutations (NPM1mut). Blood 2013, 122, 1087–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzelova, K.; Brodska, B.; Fuchs, O.; Dobrovolna, M.; Soukup, P.; Cetkovsky, P. Altered HLA Class I Profile Associated with Type A/D Nucleophosmin Mutation Points to Possible Anti-Nucleophosmin Immune Response in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0127637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, V.S.; Ghazi, H.; Fletcher, D.M.; Guinn, B.A. A Direct Comparison, and Prioritisation, of the Immunotherapeutic Targets Expressed by Adult and Paediatric Acute Myeloid Leukaemia Cells: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guinn, B.A.; Bland, E.A.; Lodi, U.; Liggins, A.P.; Tobal, K.; Petters, S.; Wells, J.W.; Banham, A.H.; Mufti, G.J. Humoral detection of leukaemia-associated antigens in presentation acute myeloid leukaemia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005, 335, 1293–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, S.P.; Sahota, S.S.; Mijovic, A.; Czepulkowski, B.; Padua, R.A.; Mufti, G.J.; Guinn, B.A. Frequent expression of HAGE in presentation chronic myeloid leukaemias. Leukemia 2002, 16, 2238–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.E.; Bonney, S.A.; Lee, C.; Publicover, A.; Khan, G.; Smits, E.L.; Sigurdardottir, D.; Arno, M.; Li, D.; Mills, K.I. , et al. Application of the pMHC Array to Characterise Tumour Antigen Specific T Cell Populations in Leukaemia Patients at Disease Diagnosis. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0140483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardwick, N.; Buchan, S.; Ingram, W.; Khan, G.; Vittes, G.; Rice, J.; Pulford, K.; Mufti, G.; Stevenson, F.; Guinn, B.A. An analogue peptide from the Cancer/Testis antigen PASD1 induces CD8+ T cell responses against naturally processed peptide. Cancer Immun 2013, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Almshayakhchi, R.; Nagarajan, D.; Vadakekolathu, J.; Guinn, B.A.; Reeder, S.; Brentville, V.; Metheringham, R.; Pockley, A.G.; Durrant, L.; McArdle, S. A Novel HAGE/WT1-ImmunoBody((R)) Vaccine Combination Enhances Anti-Tumour Responses When Compared to Either Vaccine Alone. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 636977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, M.; Schmitt, A.; Rojewski, M.T.; Chen, J.; Giannopoulos, K.; Fei, F.; Yu, Y.; Gotz, M.; Heyduk, M.; Ritter, G. , et al. RHAMM-R3 peptide vaccination in patients with acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and multiple myeloma elicits immunologic and clinical responses. Blood 2008, 111, 1357–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qazilbash, M.H.; Wieder, E.; Thall, P.F.; Wang, X.; Rios, R.; Lu, S.; Kanodia, S.; Ruisaard, K.E.; Giralt, S.A.; Estey, E.H. , et al. PR1 peptide vaccine induces specific immunity with clinical responses in myeloid malignancies. Leukemia 2017, 31, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brayer, J.; Lancet, J.E.; Powers, J.; List, A.; Balducci, L.; Komrokji, R.; Pinilla-Ibarz, J. WT1 vaccination in AML and MDS: A pilot trial with synthetic analog peptides. Am J Hematol 2015, 90, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greiner, J.; Goetz, M.; Schuler, P.J.; Bulach, C.; Hofmann, S.; Schrezenmeier, H.; Dӧhner, H.; Schneider, V.; Guinn, B.A. Enhanced stimulation of antigen-specific immune responses against nucleophosmin 1 mutated acute myeloid leukaemia by an anti-programmed death 1 antibody. Br J Haematol 2022, 198, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehninger, A.; Kramer, M.; Röllig, C.; Thiede, C.; Bornhäuser, M.; Von Bonin, M.; Wermke, M.; Feldmann, A.; Bachmann, M.; Ehninger, G. Distribution and levels of cell surface expression of CD33 and CD123 in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood cancer journal 2014, 4, e218–e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, P.C.; Dumont, L.; Scheinberg, D.A. Supersaturating infusional humanized anti-CD33 monoclonal antibody HuM195 in myelogenous leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 1998, 4, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Raza, A.; Jurcic, J.G.; Roboz, G.J.; Maris, M.; Stephenson, J.J.; Wood, B.L.; Feldman, E.J.; Galili, N.; Grove, L.E.; Drachman, J.G. , et al. Complete remissions observed in acute myeloid leukemia following prolonged exposure to lintuzumab: a phase 1 trial. Leuk Lymphoma 2009, 50, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, E.; Kalaycio, M.; Weiner, G.; Frankel, S.; Schulman, P.; Schwartzberg, L.; Jurcic, J.; Velez-Garcia, E.; Seiter, K.; Scheinberg, D. , et al. Treatment of relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia with humanized anti-CD33 monoclonal antibody HuM195. Leukemia 2003, 17, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laszlo, G.S.; Estey, E.H.; Walter, R.B. The past and future of CD33 as therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Reviews 2014, 28, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.I. How close are we to CAR T-cell therapy for AML? Best practice & research Clinical haematology 2019, 32, 101104. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, J.; Pautas, C.; Terre, C.; Raffoux, E.; Turlure, P.; Caillot, D.; Legrand, O.; Thomas, X.; Gardin, C.; Gogat-Marchant, K. , et al. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin for de novo acute myeloid leukemia: final efficacy and safety updates from the open-label, phase III ALFA-0701 trial. Haematologica 2019, 104, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hills, R.K.; Castaigne, S.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Delaunay, J.; Petersdorf, S.; Othus, M.; Estey, E.H.; Dombret, H.; Chevret, S.; Ifrah, N. , et al. Addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to induction chemotherapy in adult patients with acute myeloid leukaemia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol 2014, 15, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohner, H.; Weber, D.; Krzykalla, J.; Fiedler, W.; Kuhn, M.W.M.; Schroeder, T.; Mayer, K.; Lubbert, M.; Wattad, M.; Gotze, K. , et al. Intensive chemotherapy with or without gemtuzumab ozogamicin in patients with NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukaemia (AMLSG 09-09): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol 2023, 10, e495–e509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlenk, R.F.; Paschka, P.; Krzykalla, J.; Weber, D.; Kapp-Schwoerer, S.; Gaidzik, V.I.; Leis, C.; Fiedler, W.; Kindler, T.; Schroeder, T. , et al. Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin in NPM1-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Early Results From the Prospective Randomized AMLSG 09-09 Phase III Study. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapp-Schwoerer, S.; Weber, D.; Corbacioglu, A.; Gaidzik, V.I.; Paschka, P.; Kronke, J.; Theis, F.; Rucker, F.G.; Teleanu, M.V.; Panina, E. , et al. Impact of gemtuzumab ozogamicin on MRD and relapse risk in patients with NPM1-mutated AML: results from the AMLSG 09-09 trial. Blood 2020, 136, 3041–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hills, R.K.; Castaigne, S.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Delaunay, J.; Petersdorf, S.; Othus, M.; Estey, E.H.; Dombret, H.; Chevret, S.; Ifrah, N. , et al. Addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to induction chemotherapy in adult patients with acute myeloid leukaemia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials. The Lancet Oncology 2014, 15, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thol, F.; Schlenk, R.F. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin in acute myeloid leukemia revisited. Expert opinion on biological therapy 2014, 14, 1185–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hear, C.; Inaba, H.; Pounds, S.; Shi, L.; Dahl, G.; Bowman, W.P.; Taub, J.W.; Pui, C.H.; Ribeiro, R.C.; Coustan-Smith, E. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin can reduce minimal residual disease in patients with childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2013, 119, 4036–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaigne, S.; Pautas, C.; Terré, C.; Raffoux, E.; Bordessoule, D.; Bastie, J.-N.; Legrand, O.; Thomas, X.; Turlure, P.; Reman, O. Effect of gemtuzumab ozogamicin on survival of adult patients with de-novo acute myeloid leukaemia (ALFA-0701): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. The Lancet 2012, 379, 1508–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenk, R.F.; Paschka, P.; Krzykalla, J.; Weber, D.; Kapp-Schwoerer, S.; Gaidzik, V.I.; Leis, C.; Fiedler, W.; Kindler, T.; Schroeder, T. , et al. Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin in NPM1-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML): Results from the Prospective Randomized AMLSG 09-09 Phase-III Study. Blood 2018, 132, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perriello, V.M.; Gionfriddo, I.; Rossi, R.; Milano, F.; Mezzasoma, F.; Marra, A.; Spinelli, O.; Rambaldi, A.; Annibali, O.; Avvisati, G. , et al. CD123 Is Consistently Expressed on NPM1-Mutated AML Cells. Cancers 2021, 13, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.Z.; Busfield, S.; Ritchie, D.S.; Hertzberg, M.S.; Durrant, S.; Lewis, I.D.; Marlton, P.; McLachlan, A.J.; Kerridge, I.; Bradstock, K.F. A Phase 1 study of the safety, pharmacokinetics and anti-leukemic activity of the anti-CD123 monoclonal antibody CSL360 in relapsed, refractory or high-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia & lymphoma 2015, 56, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Pemmaraju, N.; Lane, A.A.; Sweet, K.L.; Stein, A.S.; Vasu, S.; Blum, W.; Rizzieri, D.A.; Wang, E.S.; Duvic, M.; Sloan, J.M. Tagraxofusp in blastic plasmacytoid dendritic-cell neoplasm. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 380, 1628–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daver, N.; Montesinos, P.; Aribi, A.; Marconi, G.; Altman, J.K.; Wang, E.S.; Roboz, G.J.; Burke, P.W.; Gaidano, G.; Walter, R.B. , et al. Broad Activity for the Pivekimab Sunirine (PVEK, IMGN632), Azacitidine, and Venetoclax Triplet in High-Risk Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML). Blood 2022, 140, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Drake, A.C.; Hu, G.; Rudnick, S.; Chen, Q.; Phennicie, R.; Attar, R.; Nemeth, J.; Gaudet, F.; Chen, J. Induction and therapeutic targeting of human NPM1c+ myeloid leukemia in the presence of autologous immune system in mice. The Journal of Immunology 2019, 202, 1885–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Liu, P. A perspective of immunotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia: Current advances and challenges. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.; Cui, L.; Zhao, X.; Bai, H.; Cai, S.; Wang, G.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, J.; Chen, S.; Song, J. , et al. Use of Immunotherapy With Programmed Cell Death 1 vs Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 Inhibitors in Patients With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 2020, 6, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Han, X. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy of human cancer: past, present, and future. J Clin Invest 2015, 125, 3384–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greiner, J.; Hofmann, S.; Schmitt, M.; Gotz, M.; Wiesneth, M.; Schrezenmeier, H.; Bunjes, D.; Dohner, H.; Bullinger, L. Acute myeloid leukemia with mutated nucleophosmin 1: an immunogenic acute myeloid leukemia subtype and potential candidate for immune checkpoint inhibition. Haematologica 2017, 102, e499–e501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amato, R.J.; Loughnan, M.S.; Flynn, E.; Folkman, J. Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994, 91, 4082–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guinn, B.A.; Schuler, P.J.; Schrezenmeier, H.; Hofmann, S.; Weiss, J.; Bulach, C.; Gotz, M.; Greiner, J. A Combination of the Immunotherapeutic Drug Anti-Programmed Death 1 with Lenalidomide Enhances Specific T Cell Immune Responses against Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greiner, J., Schuler, P.J., Schrezenmeier, H., Weiss, J., Bulach, C., Goetz, M., Guinn, B. Combinations of Different Immunotherapeutics Enhance Specific T Cell Immune Responses Against Leukemic Cells, as well as Leukemic Progenitor and Stem Cells in Acute Myeloid Leukemia In Preparation.

- Huang, Z.W.; Zhang, X.N.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.L.; Zhang, J.W.; Sun, Y.X.; Xu, J.Q.; Liu, Q.; Long, Z.J. STAT5 promotes PD-L1 expression by facilitating histone lactylation to drive immunosuppression in acute myeloid leukemia. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daver, N.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Basu, S.; Boddu, P.C.; Alfayez, M.; Cortes, J.E.; Konopleva, M.; Ravandi-Kashani, F.; Jabbour, E.; Kadia, T. , et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Biomarkers of Response to Azacitidine and Nivolumab in Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Nonrandomized, Open-Label, Phase II Study. Cancer Discov 2019, 9, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wong, M.P.M.; Ng, R.K. Aberrant DNA Methylation in Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Its Clinical Implications. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, L.; Wong, C.Y.G.; Gill, H. Targeting and Monitoring Acute Myeloid Leukaemia with Nucleophosmin-1 (NPM1) Mutation. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachowiez, C.A.; Loghavi, S.; Zeng, Z.; Tanaka, T.; Kim, Y.J.; Uryu, H.; Turkalj, S.; Jakobsen, N.A.; Luskin, M.R.; Duose, D.Y. , et al. A Phase Ib/II Study of Ivosidenib with Venetoclax +/- Azacitidine in IDH1-Mutated Myeloid Malignancies. Blood Cancer Discov 2023, 4, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.-C.; Rérolle, D.; Berthier, C.; Hleihel, R.; Sakamoto, T.; Quentin, S.; Benhenda, S.; Morganti, C.; Wu, C.; Conte, L. Actinomycin D targets NPM1c-primed mitochondria to restore PML-driven senescence in AML therapy. Cancer discovery 2021, 11, 3198–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Qin, F.; Yang, L.; Xian, J.; Zou, Q.; Jin, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L. Nucleophosmin mutations induce chemosensitivity in THP-1 leukemia cells by suppressing NF-κB activity and regulating Bax/Bcl-2 expression. Journal of Cancer 2016, 7, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, A.W.; Davids, M.S.; Pagel, J.M.; Kahl, B.S.; Puvvada, S.D.; Gerecitano, J.F.; Kipps, T.J.; Anderson, M.A.; Brown, J.R.; Gressick, L. Targeting BCL2 with venetoclax in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine 2016, 374, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowiez, C.A.; Reville, P.K.; Kantarjian, H.; Jabbour, E.; Borthakur, G.; Daver, N.; Issa, G.; Furudate, K.; Tanaka, T.; Pierce, S. Contemporary outcomes in IDH-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: The impact of co-occurring NPM1 mutations and venetoclax-based treatment. American journal of hematology 2022, 97, 1443–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintás-Cardama, A.; Ravandi, F.; Liu-Dumlao, T.; Brandt, M.; Faderl, S.; Pierce, S.; Borthakur, G.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Cortes, J.; Kantarjian, H. Epigenetic therapy is associated with similar survival compared with intensive chemotherapy in older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2012, 120, 4840–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombret, H.; Seymour, J.F.; Butrym, A.; Wierzbowska, A.; Selleslag, D.; Jang, J.H.; Kumar, R.; Cavenagh, J.; Schuh, A.C.; Candoni, A. International phase 3 study of azacitidine vs conventional care regimens in older patients with newly diagnosed AML with> 30% blasts. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2015, 126, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veselý, J. Mode of action and effects of 5-azacytidine and of its derivatives in eukaryotic cells. Pharmacology & therapeutics 1985, 28, 227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, A.H.; Montesinos, P.; Ivanov, V.; DiNardo, C.D.; Novak, J.; Laribi, K.; Kim, I.; Stevens, D.A.; Fiedler, W.; Pagoni, M. Venetoclax plus LDAC for newly diagnosed AML ineligible for intensive chemotherapy: a phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2020, 135, 2137–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, A.H.; Strickland Jr, S.A.; Hou, J.-Z.; Fiedler, W.; Lin, T.L.; Walter, R.B.; Enjeti, A.; Tiong, I.S.; Savona, M.; Lee, S. Venetoclax combined with low-dose cytarabine for previously untreated patients with acute myeloid leukemia: results from a phase Ib/II study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2019, 37, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dick, J.E.; Bhatia, M.; Gan, O.; Kapp, U.; Wang, J.C. Assay of human stem cells by repopulation of NOD/SCID mice. Stem Cells 1997, 15 Suppl 1, 199-203; discussion 204-197. [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.; Marcucci, G.; Maharry, K.; Radmacher, M.D.; Mrozek, K.; Margeson, D.; Whitman, S.P.; Wu, Y.Z.; Schwind, S.; Paschka, P. , et al. Favorable prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations in older patients with cytogenetically normal de novo acute myeloid leukemia and associated gene- and microRNA-expression signatures: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol 2010, 28, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachowiez, C.A.; Loghavi, S.; Kadia, T.M.; Daver, N.; Borthakur, G.; Pemmaraju, N.; Naqvi, K.; Alvarado, Y.; Yilmaz, M.; Short, N. , et al. Outcomes of older patients with NPM1-mutated AML: current treatments and the promise of venetoclax-based regimens. Blood Adv 2020, 4, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodska, B.; Otevrelova, P.; Salek, C.; Fuchs, O.; Gasova, Z.; Kuzelova, K. High PD-L1 Expression Predicts for Worse Outcome of Leukemia Patients with Concomitant NPM1 and FLT3 Mutations. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadzadeh, M.; Johnson, L.A.; Heemskerk, B.; Wunderlich, J.R.; Dudley, M.E.; White, D.E.; Rosenberg, S.A. Tumor antigen-specific CD8 T cells infiltrating the tumor express high levels of PD-1 and are functionally impaired. Blood 2009, 114, 1537–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Pei, Y.; Luo, J.; Huang, Z.; Yu, J.; Meng, X. Looking for the Optimal PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitor in Cancer Treatment: A Comparison in Basic Structure, Function, and Clinical Practice. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orskov, A.D.; Treppendahl, M.B.; Skovbo, A.; Holm, M.S.; Friis, L.S.; Hokland, M.; Gronbaek, K. Hypomethylation and up-regulation of PD-1 in T cells by azacytidine in MDS/AML patients: A rationale for combined targeting of PD-1 and DNA methylation. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 9612–9626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tettamanti, S.; Pievani, A.; Biondi, A.; Dotti, G.; Serafini, M. Catch me if you can: how AML and its niche escape immunotherapy. Leukemia 2022, 36, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knights, A.J.; Weinzierl, A.O.; Flad, T.; Guinn, B.A.; Mueller, L.; Mufti, G.J.; Stevanovic, S.; Pawelec, G. A novel MHC-associated proteinase 3 peptide isolated from primary chronic myeloid leukaemia cells further supports the significance of this antigen for the immunotherapy of myeloid leukaemias. Leukemia 2006, 20, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelde, A.; Schuster, H.; Heitmann, J.S.; Bauer, J.; Maringer, Y.; Zwick, M.; Volkmer, J.P.; Chen, J.Y.; Stanger, A.M.P.; Lehmann, A. , et al. Immune Surveillance of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Is Mediated by HLA-Presented Antigens on Leukemia Progenitor Cells. Blood Cancer Discov 2023, 4, 468–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).