1. Introduction

In the future the supply of organic platform chemicals will require the use of new starting materials. Currently the vast majority of organics required by chemical industries such as pharmaceuticals, fragrances and materials, are derived from oil. Chemists, biologists and engineers must work together to ensure the chemical industry evolves into the greenest and most sustainable version possible. The use of chemicals derived from biomass feedstocks requires the invention of a new generation of industrial processes and new transformations. [

1] The current, petrochemicals dominated-chemical industry, concentrates on the addition of oxygen-based functionality to hydrocarbons; however, biomass derived chemicals tend to be more highly oxygenated, and a promising approach to synthesise biomass derived chemicals is to remove oxygen from chemicals derived from biorenewables. Dehydration and reduction are two suitable catalytic methods for selective oxygen removal, as is fermentation by a biocatalyst, which can be coupled to downstream chemo- or bio-catalytic transformations to prepare a range of value-added chemicals. In this way we can generate a range of chemicals can be prepared from biomass by combining bio- and chemo-catalysis via a common bio-renewable intermediate [

2].

1,3-Propandiol (1,3-PDO) is a biorenewable intermediate with a lot of promise. Petrochemical routes to 1,3-PDO, which involved multiple steps and toxic reagents, have been declining as bioderived 1,3-PDO has replaced them. 1,3-PDO can be generated by flexible routes, as it can be derived from excess carbohydrates by fermentation, or from fats and oils via glycerol. This demonstrates flexibility in feedstocks for Bio-PDO production ensuring security of supply. Fermentation of biomass to produce 1,3-PDO is well established [

3,

4,

5]. The first generation of processes were based on carbohydrate fermentation. Dupont Tate & Lyle Bioproducts produce bio-1,3-PDO industrially by the fermentation of starch and sugars derived from corn, an abundant crop in North America. More recently routes from fats and oils are becoming commercialised. For example, natural vegetable oils such as waste cooking oil (rapeseed, sunflower etc.) can be converted to biodiesel by heterogenous acid, homogeneous acid or base, or enzymatic catalysts to yield glycerol as a by-product. Glycerol derived from fats and oils can be converted to 1,3-PDO by fermentation, and a number of companies, particularly in China, are engaged in commercial production.

In collaboration with Stephens, Rebroš and co-workers, we have studied the digestion of glycerol derived from fats and oils to produce 1,3-PDO by whole cell biocatalysis for a number of years, concentrating on

Clostridium butyricum [

6,

7,

8,

9] The layering of a biocompatible ionic liquid as a second, upper phase, was shown to enable the extraction of the product, and improve performance [

7]. The use of crude, contaminated glycerol, was facilitated by immobilizing the biocatalyst in a polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) hydrogel, and the entrapment of glycerol in a silica gel to control the release of substrate to the bacterium [

9].

Recently new chemocatalytic routes to bioderived 1,3-PDO have been emerging and a number of heterogeneous catalytic processes have been reported to convert glycerol into 1,3-PDO, with the reaction classed as a ‘hydrogenolysis’ comprising hydrogenation and dehydration. Avoiding the formation of 1,2-PDO is key to success [

10,

11,

12].

Traditionally the main use of 1,3-PDO was in polymer synthesis. However, there is a wealth of new green chemistry to be discovered downstream from 1,3-PDO, which could become a rich source of organic intermediates. As the petrochemical route to 1,3-PDO was relatively complex, it was not deemed a convenient starting point for petrochemicals, however, in the new era, it can be considered one of the most convenient bioderived platforms, and an excellent start point for a range of other organics.

The dehydrogenation of alcohols renders them reactive as aldehydes or ketones [

13,

14].

We previously demonstrated the use of hydrogen borrowing/ hydrogen transfer methodology to synthesize secondary amines from 1,3-PDO [

6,

15]. During these reactions it was observed that, under basic ionic liquid conditions, there was a strong tendency to dehydrate. In the absence of an amine reactant this enabled the synthesis of propanal (

2) from 1,3-propanediol (1,3-PDO) in high yields and selectivities via base-assisted hydrogen transfer initiated dehydration (HTID). [

16,

17,

18] The procedure employed recyclable Cp*IrCl

2(NHC) pre-catalysts. The utility of Iridium catalysts for converting biomass has been noted [

19].

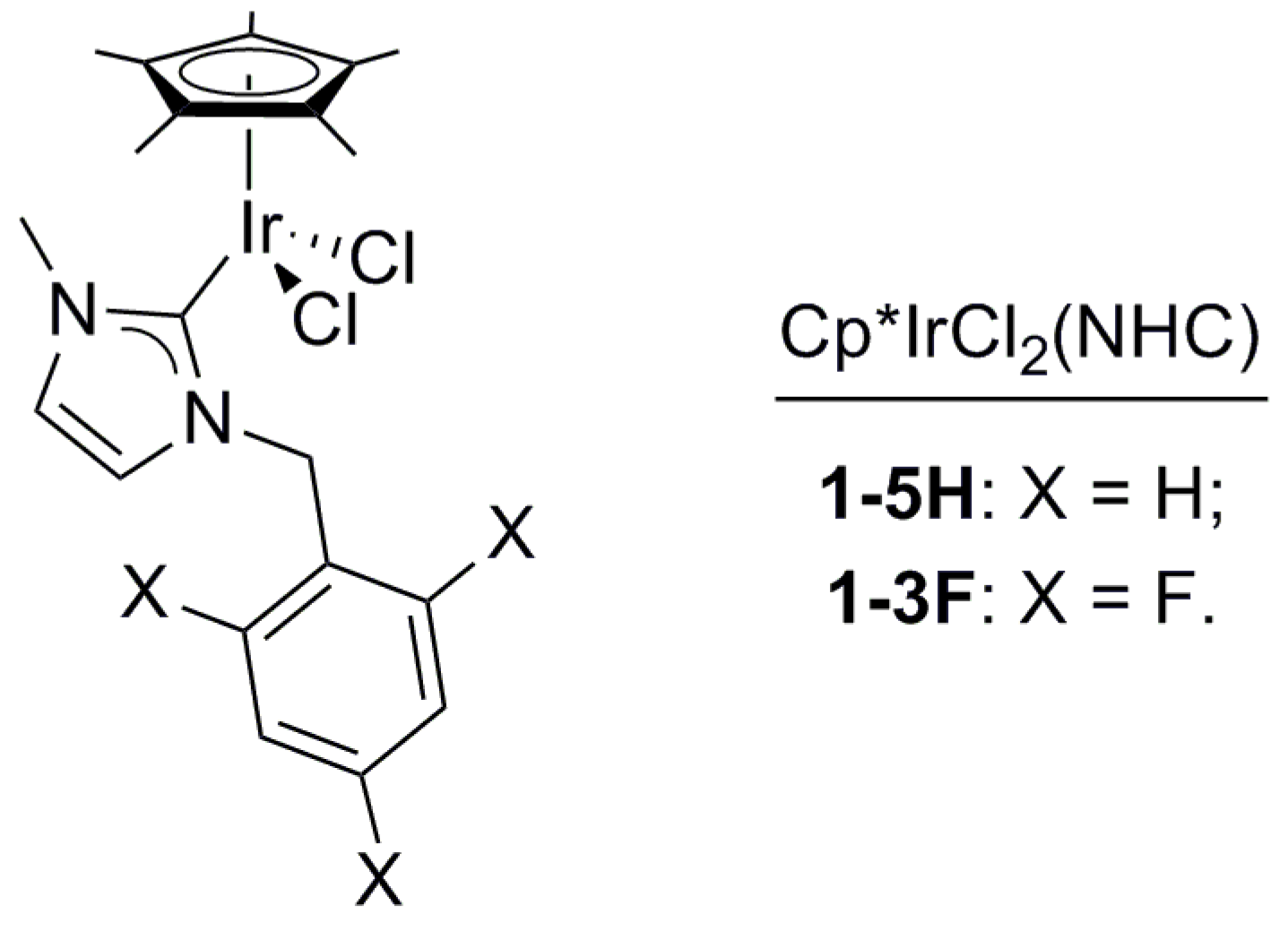

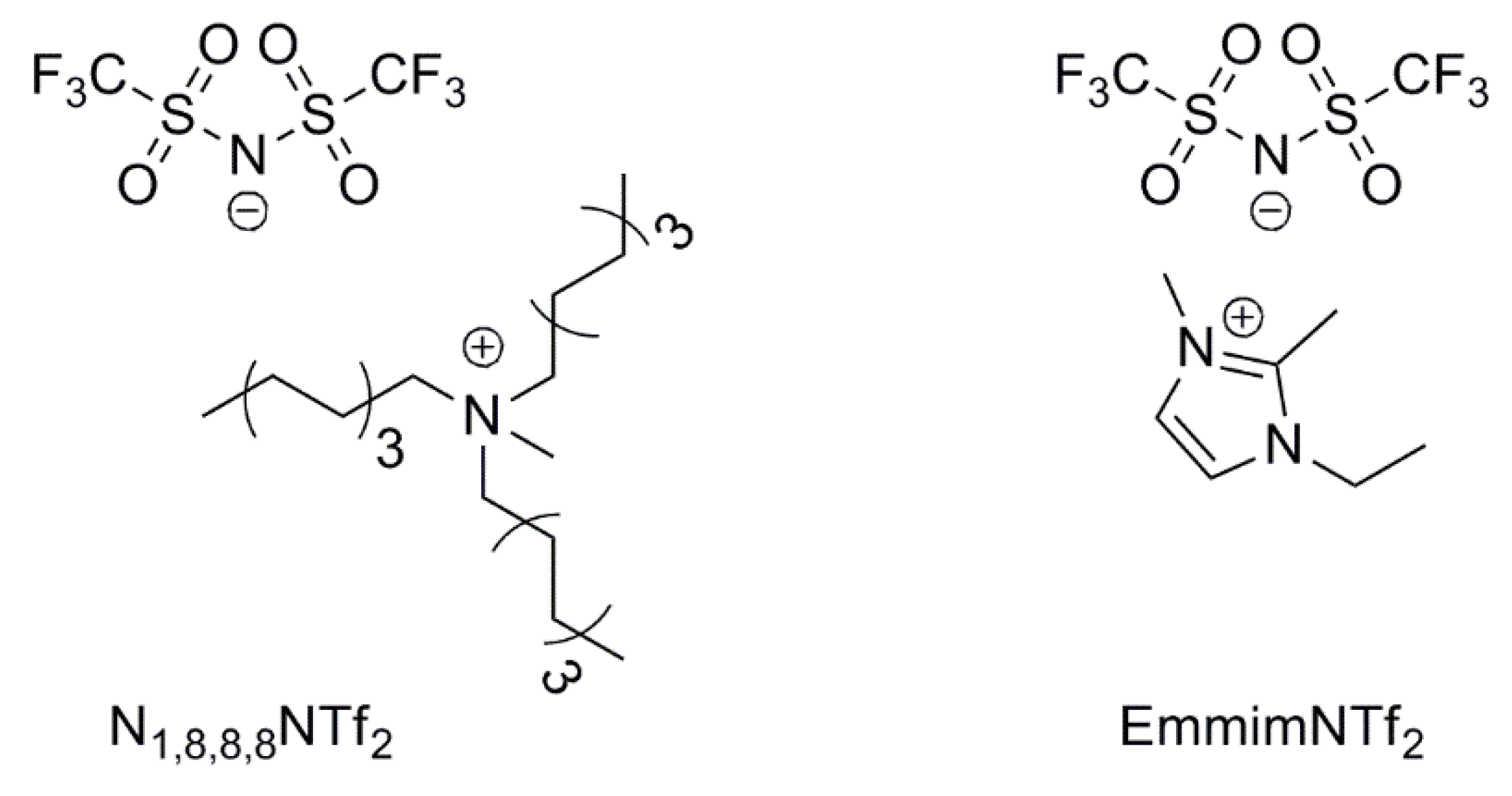

The treatment of 1,3-PDO with a base and a Cp*IrCl

2(NHC) complex (

1-5H,

1-3F,

Figure 1), in 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethyl-imidazolium-

N,

N-bistriflimide (EmmimNTf

2) or methyl-tri-

n-octyl-ammonium-

N,

N-bistriflimide (N

1,8,8,8NTf

2) (

Figure 2), was found to lead to a range of C3 and C6 alcohols and aldehydes. Propanal (

2), 2-methyl-pent-2-enal (

3), 2-methyl-pentanal (

4), and 1-propanol (

5) were the main products observed (

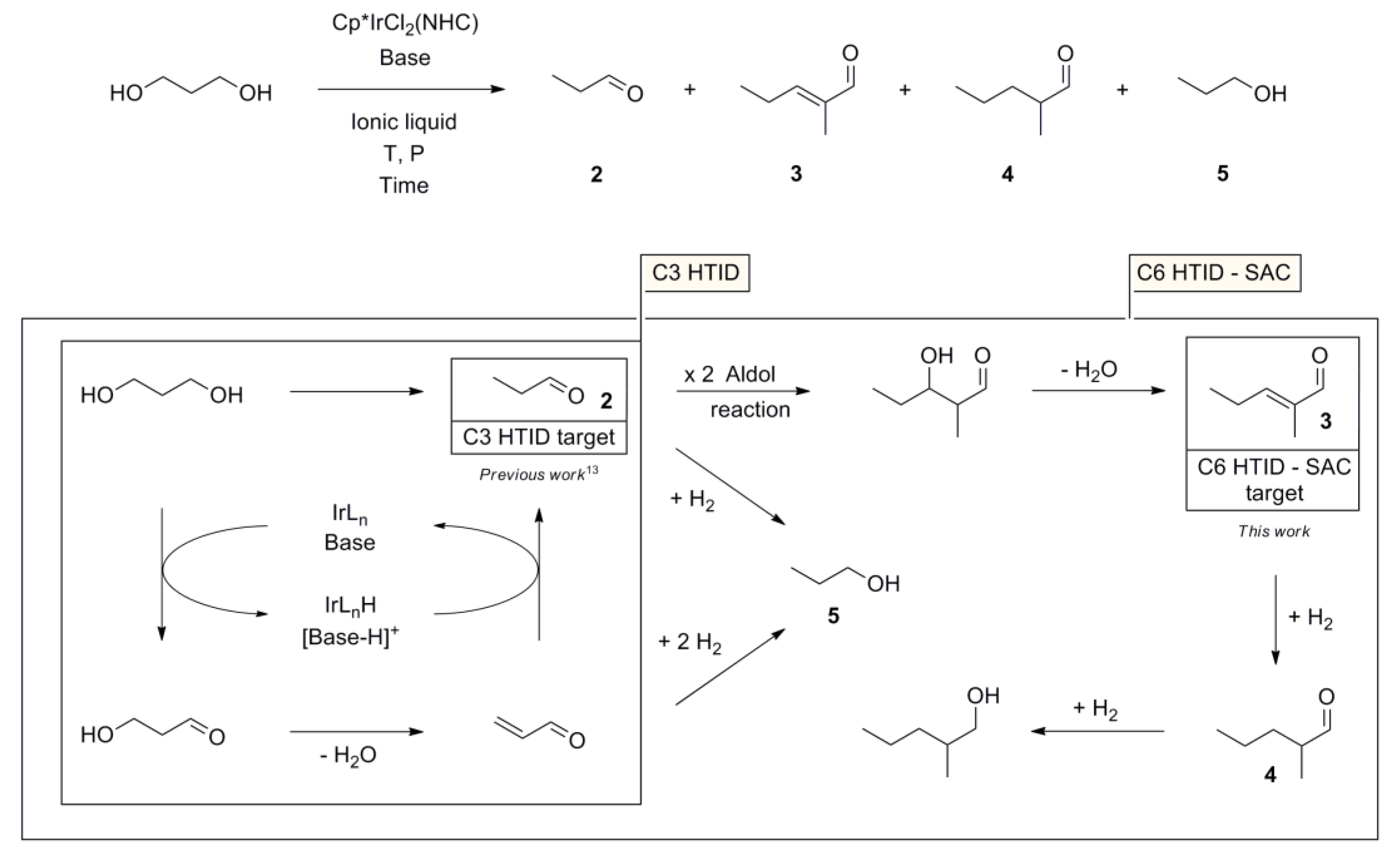

Scheme 1). The transition from C3 to C6 products occurs due to self-aldol condensation (SAC). Reaction yield and selectivity could be controlled by tuning (a) the nature and loading of the Cp*IrCl

2(NHC) pre-catalyst, (b) the ionic liquid used as the solvent, the reaction (c) temperature and (d) pressure, and (e) the nature and loading of the assisting base. The HTID can therefore be driven towards specific targets by tuning the reaction conditions. Operating a dehydration in an ionic liquid provides a unique opportunity for facile separation of C3 products. The aldehyde products are far more volatile than the solvent and the substrates and so running the reaction under vacuum enables removal of propanal as it is formed. High selectivity towards

2 could be obtained when running the HTID of 1,3-PDO under vacuum (

ca. 0.350 mBar).

A reaction pathway rationalising the formation of

2,

3,

4, and

5 from 1,3-PDO is shown in

Scheme 1. Formation of

2 occurs via the Cp*IrCl

2(NHC)-catalysed, base-assisted HTID of 1,3-PDO through the intermediates 3-hydroxypropionaldehyde and acrolein. Both

2 and acrolein could then undergo hydrogenation to

5. Propanal (

2) can dimerise, via SAC, to deliver

3, after dehydration. Hydrogenation of

3 generates

4 and 2-methyl-pentanol, a minor by-product, respectively. Running the HTID of 1,3-PDO in ionic liquids under vacuum allows removal of

2 from the reaction mixture as soon as formed, preventing from its further reaction; and affording good selectivity.

Here we report the coupling of HTID and SAC in one-pot to generate C6 aldehyde

3 in good yield. 2-methyl-pent-2-enal (

3) has commercial applications in food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics. Fragrant and flavoured esters, [

20] including lactones, [

21] as well as esters of branched C9 alcohols suitable as plasticisers, [

22] can be synthesized from

3. In industry,

3 is prepared by the self-aldol condensation of

2, carried out in the presence of stoichiometric amounts of an aqueous base such as NaOH or KOH. [

23,

24,

25,

26] Under optimized conventional reaction conditions, 86 % selectivity to

3, with 99 % conversion of

2, has been achieved.

Homogeneous catalytic aldol condensation reactions can have major drawbacks. Low selectivity and the generation of organically contaminated caustic waste streams are common. [

27,

28,

29] Aldol condensation reactions are typically accompanied by side reactions significantly reducing the yield of desired products and resulting in unwanted products to be separated and disposed of as waste. Aldol reactions are often carried out in aqueous solutions leading to the production of large quantities of wastewater. [

30] The greener synthesis of aldol condensation products such as

3 is an important goal.

Due to its value, significant effort has been spent trying to improve the production of

3 by SAC of

2. Mehnert and co-workers reported the highly selective synthesis of

3 (82 %), with quantitative conversion of

2, in ionic liquid [bdmim][PF

6] ([bdmim]: 1-butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium), in the presence of sodium hydroxide. [

25,

26] Kawanami and co-workers demonstrated that

3 could be obtained in supercritical CO

2 with 94 % selectivity at the critical pressure of CO

2 of 12 MPa, in the presence of MgO catalyst and a small amount of water. [

31] Also in supercritical CO

2 Poliakoff and co-workers reported the synthesis of

3, with selectivity up to 99 %, in the presence of a variety of heterogeneous acidic and basic catalysts such as Amberlist

® 15,

γ-Alumina, Purolite

®CT175 [

29]. Selective, solvent free syntheses of

3 from

2 in the presence of solid base catalysts were reported by Sharma et al. Liquid phase self-aldol condensation of

2, using activated hydrotalcite of Mg/Al molar ratio 3.5 as the catalyst, led to conversions up to 97 % with 99 % selectivity towards

3. [

32]. The direct production of

3 from

2 via SAC was achieved in water by Hayashi and co-workers using the amino amide Pro-NH

2 as the catalyst. Dissolving propanal and a catalytic amount of Pro–NH

2 in water resulted first in a homogeneous solution containing the aldol product 2-methyl-pentan-1,3-diol. If the aqueous solution was stirred for longer than 2.5 hours, an oily phase, consisting of

3, the dehydrated aldol adduct formed; after stirring for 24 hours, hydrophobic

3 was isolated in 56 % yield. [

33]

The efficient, selective, synthesis of

2 from 1,3-PDO, using recyclable Cp*IrCl

2(NHC) catalyst precursors, in ionic liquids, reported by this group, [

16,

17,

18] prompted us to attempt the synthesis of

3 directly from 1,3-PDO, by combining HTID and SAC in a one-pot, one-step synthetic method.

3. Results and Discussion

The selective synthesis of 2-methyl-pent-2-enal (

3) was targeted by carrying out the hydrogen transfer initiated dehydration (HTID) of 1,3-PDO and maximizing the aldol condensation of propanal (

2). According to the reaction mechanism postulated in

Scheme 1, building up a sufficient concentration of

2 should maximise self-aldol condensation (SAC) and result in higher selectivity towards

3 (and

4).

The reaction of 1,3-PDO in the presence of the Ir(III) complexes

1-5H and

1-3F and K

2CO

3 in the ionic liquids EmmimNTf

2 or N

1,8,8,8NTf

2, at temperature varying in the range 100 – 180 °C, under air, was therefore successfully driven towards the selective production of

3 by operating in a sealed reaction tube (see

Table 1 and

Table 2, and

Tables S11–S17). In the closed reaction vessel,

2 was forced to further react after its formation; dimerisation via SAC resulted in product solutions in which

2 had been largely consumed, and

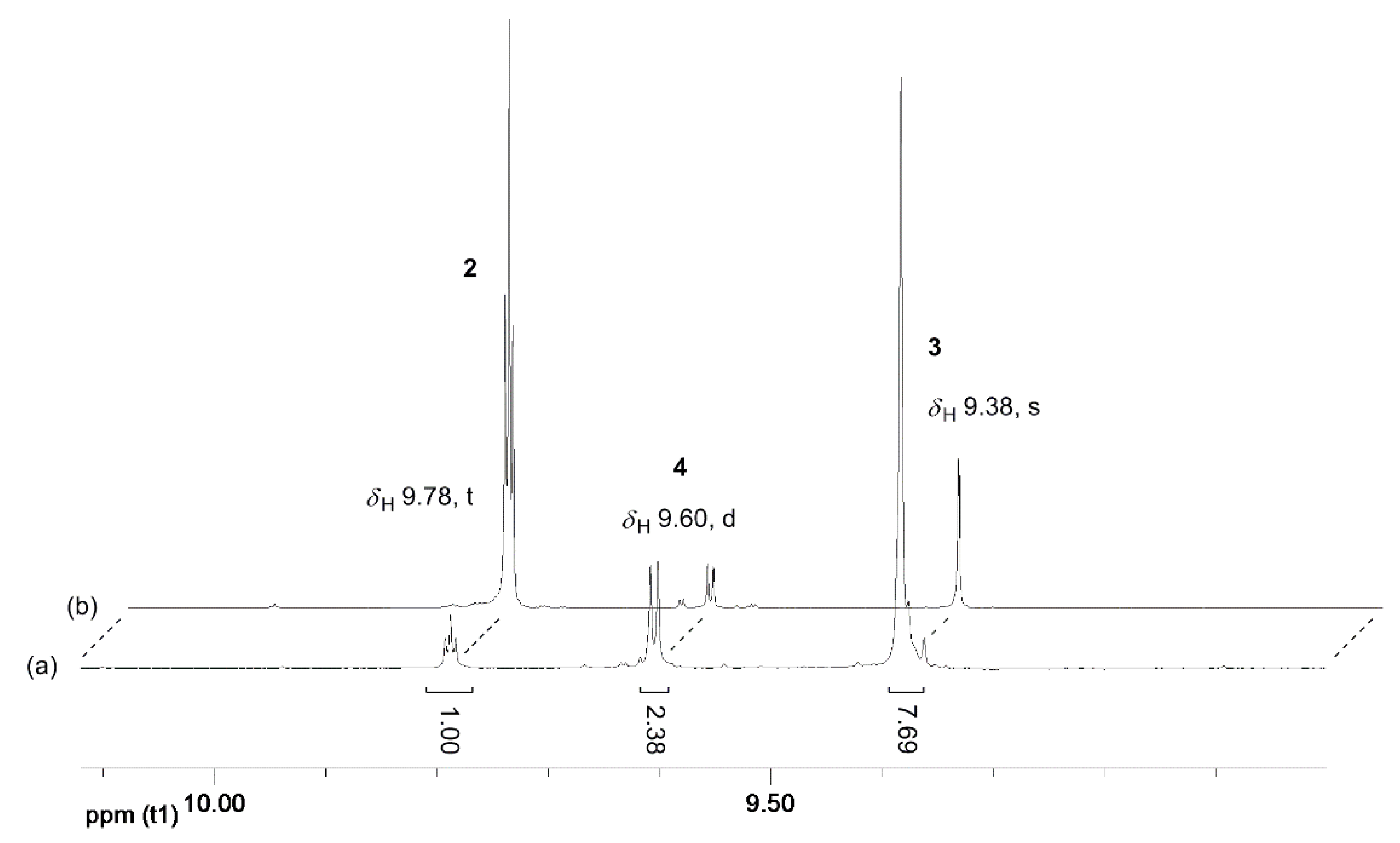

3 was the major product. The

1H NMR spectra of the product solutions display, in the aldehydic region, the singlet at

δH 9.38 due to the aldehydic proton of the dominant species

3, along with the doublet at

δH 9.60 and the triplet at

δH 9.78 due to the aldehydic protons of the minor components

4 and

2, respectively. The relative intensity of the peaks due to

2,

3, and

4 results inverted compared to that observed in the NMR spectra of the crude product obtained under

vacuum (see

Figure 3). Surprisingly, no formation of the C3 alcohol

5 (a major side-product when running the HTID of 1,3-PDO at ca. 0.350 mBar to selectively produce

2) was observed at any of the reaction conditions tested: the triplet at

δH 3.59, due to the C

H2OH protons of

5, was never detected. No cross-aldol condensation side-products were observed in the reaction product solutions. Having accessed the C6 aldehyde chemistry, cross-aldolization involving

2,

3, and

4, and then the ensuing products, can result in a mixture of aldol products having a range of carbon atom numbers (C≥9 aldehydes). C. P. Mehnert and co-workers observed large amounts of high boiling aldehydes (C>9) when generating C6-aldehydes (i.e.,

3) via cross-aldol condensation of a C3-aldehyde precursor such as

2, at 80 °C, in NaOH – containing ionic liquids. [

25,

26] In the reaction product solutions resulting from the HTID / SAC treatment of 1,3-PDO only very minor, negligible signals were detected in the aldehydic region of the

1H NMR spectra of the product solutions, along with those due to

2,

3, and

4 (

Figure 3).

The maximum selectivity towards

3 achieved via the combination of HTID and SAC achieved (> 80 %) is comparable to that obtained by M. Poliakoff and co-workers running SAC in scCO

2, [

29]. Whilst aldehyde

2 is the substrate in the SAC literature accounts cited, the combination of HTID and SAC enables the synthesis of

3 directly from the biorenewable platform 1,3-PDO. In addition, mild temperatures allow quantitative or high substrate conversions via HTID / SAC, whereas higher temperatures (

ca. 285 °C) were required to achieve satisfying conversions in the production of

3 from

2 in scCO

2. For example, in the presence of

Ir-3F, quantitative conversions of 1,3-PDO were observed at 100 – 120 °C in EmmimNTf

2, the selectivities varied in the range 70 – 80 %, and at 150 °C in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2 selectivities were 80 – 90 %; in the presence of

Ir-5F, at 100 – 150 °C, conversions of 1,3-PDO varied in the range 80 – 90 % in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2 with selectivities of 80 – 90 %. Quantitative conversions of the substrate

2 were observed at 80 °C by P. Mehnert and co-workers running the SAC of

2 to

3 in [bdmim][PF

6] treated with NaOH-H

2O (selectivity towards

3: 82 %), and in NaOH-H

2O (selectivity: 82 %). [

25,

26]

The influence of the nature and loading of the pre-catalyst, the ionic liquid used as the solvent, the temperature, and the loading of the base, on both the conversions of 1,3-PDO and the selectivity towards the C6 aldehyde 3, was investigated. Maximum conversions were targeted at each of the reaction conditions investigated. The reaction time and selectivities observed at the different reaction conditions are reported at the maximum conversion.

The Ir(III) complexes

1-5H or

1-3F (

Figure 1), and the base, are indispensable: no reaction of 1,3-PDO was observed either in the presence of

1-5H, or

1-3F, in the absence of base (see entry 22 in

Table 1 for

1-5H, and entry 20 in

Table 2 for

1-3F), or,

vice versa, in the presence of base and in the absence of

1-5H, or

1-3F (see entries 17 and 18 in

Table 1). No HTID can be initiated, prior to SAC, in the absence of either the pre-catalyst Cp*IrX

2(NHC) or the assisting base.

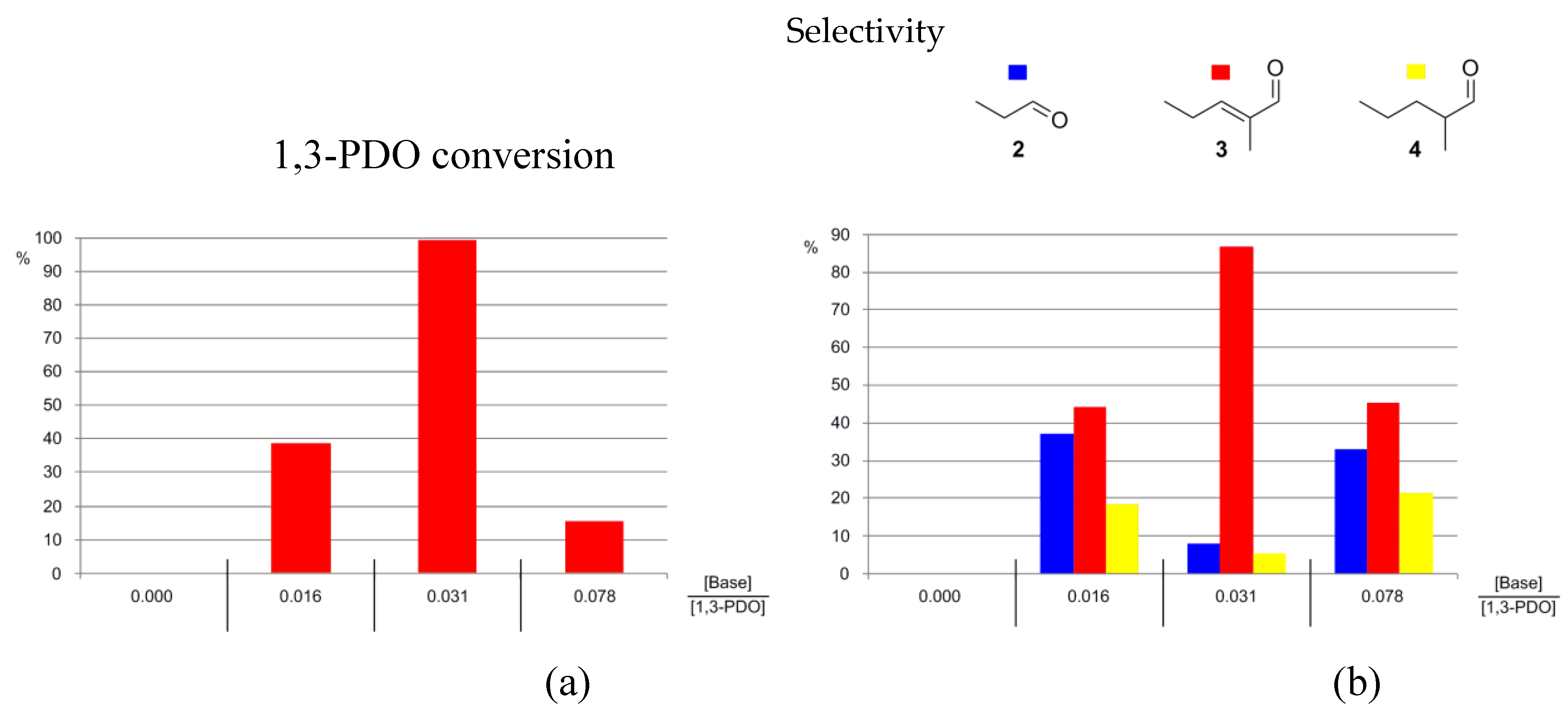

3.1. The Effects of Altering the Base

Two bases were used to promote the reaction K

2CO

3 or KOH. Only a minor effect on the reaction outcome was observed when changing the base: conversions and selectivities were found to be similar when using either K

2CO

3 or KOH. In order to minimise production of caustic reaction waste, K

2CO

3 was selected as the assisting base for the HTID of 1,3-PDO for C6 aldehyde production. The concentration of base was found to be a key parameter for efficient conversion of 1,3-PDO and selective synthesis of

3. The optimal ratio [Base]:[1,3-PDO] to be used for the selective production of

3, and with high conversions of 1,3-PDO, was found to be the same as that needed when targeting

2, [

16,

17] namely [Base]:[1,3-PDO] ≅ 0.031, in the presence of both the pre-catalysts

1-5H (

Figure S1) and

1-3F (

Figure 4). For example, when reacting 1,3-PDO at 150 °C, at [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅195.0, in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2, the conversion of 1,3-PDO was found to be 89 and 99 % in the presence of

1-5H (after 1 day) and

1-3F (after 3 days), respectively, when [Base]:[1,3-PDO] ≅ 0.031. The selectivity towards

3 resulted 76.9 and 86.6 %, respectively, while that towards

4 was found to be 18.5 and 5.4 %, respectively. 4.6 and 8.0 % of

2, respectively, were also detected (see entry 6 in

Table 1 for

1-5H, and entry 6 in

Table 2 for

1-3F). Ratios [Base]:[1,3-PDO] lower and higher than 0.031 resulted in lower 1,3-PDO conversions and lower selectivities towards

3.

Subsequent reactions were carried out at the ratio [Base]:[1,3-PDO] ≅ 0.031.

3.2. The Effect of Catalyst Loading and Temperature

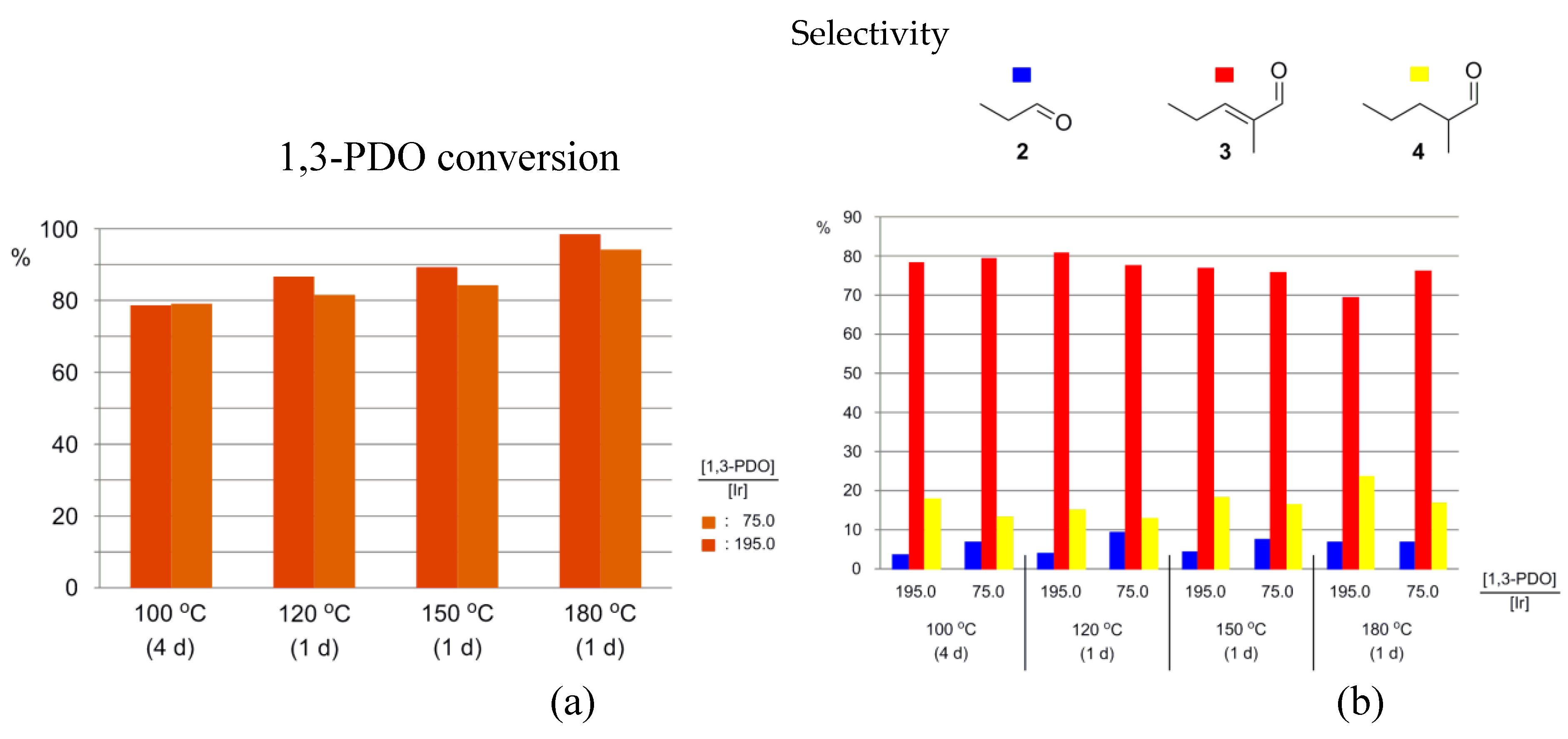

3.2.1. In the Presence of 1-5H

When using

1-5H as the catalyst precursor, different catalyst loadings result in little to moderate changes in both 1,3-PDO conversions and product selectivities. When running the HTID - SACat 100 °C, the reaction was slow. A conversion of 79 % was measured after 4 days at both [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅75.0 and 195.0, in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2 (entries 1 and 2 in

Table 1, and

Figure 5a). 77 % conversion was observed after 7 days, at both [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅75.0 and 195.0, in EmmimNTf

2 (entries 9 and 10 in

Table 1, and

Figure S2a).

In N

1,8,8,8NTf

2, rates of 1,3-PDO conversion increased with increasing temperature with conversions over 80% achieved after one day at 120, 150 and 180 °C (

Figure 5a). The maximum conversion after 1 day of 98 % was achieved at 180 °C. Selectivities towards

3 changed relatively little with temperature with typical values measured being between 75 and 80% selectivity towards

3 after 1 day (

Figure 5b). At temperatures varying in the range 120 – 180 °C, the selectivity towards

2 varied in the range 4.0 – 9.3 %, while that towards

4 varied in the range 13.2 – 23.6 %.

In EmmimNTf

2, 1,3-PDO conversion was slower and decreased with increasing temperature from 100 °C (77 % after 7 days) to 120 °C (after 4 days: 60 and 44 % at [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅ 75.0 and 195.0, respectively,

Figure S2a). At higher temperature the rate improved significantly. At 180 °C after 1 day: 88 and 93 % conversion was observed at [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅ 75.0 and 195.0, respectively) (see entries 11-16 in

Table 1, and

Figure S2a). However the increase of rate was accompanied by a significant decrease in selectivity (

Figure S2b) confirming EmmimNTf

2 to be an inferior solvent for the reaction. This, compounded with the difficulty of synthesizing the cation, render Emmim cations a poorer choice than ammonium cations.

3.2.2. In the Presence of 1-3F

When running the HTID - SAC in the presence of

1-3F as the pre-catalyst, high percentage conversions of 1,3-PDO were observed in both N

1,8,8,8NTf

2 and EmmimNTf

2. 97 – 99 % of 1,3-PDO was converted when running the reaction for 1, 3, 5, 7 days at 180, 150, 120, 100 °C, respectively, at any [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] (see entries 2-16 in

Table 2, and

Figure 6a and Figure S3a);slightly lower, but still high (73 %), conversion was observed only when reacting 1,3-PDO in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2, at 100 °C, at [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅75.0 (see entry 1 in

Table 2). High selectivities towards

3 were observed in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2, at 150 °C (reaction time: 3 days), at both [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅75.0 (82.1 %), and195.0 (86.6 %); and in EmmimNTf

2, at 100 °C (reaction time: 7 days) when [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅195.0 (70.9 %), and at 120 °C (reaction time: 5 days) when [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅195.0 (76.0 %) (see entries 5, 6, 10, and 12 in

Table 2, respectively, and

Figure 6b and Figure S3b). Otherwise, selectivity towards

3 was found to be lower when reacting 1,3-PDO in presence of

1-3F, varying in the range 35.7 - 64.8 % in EmmimNTf

2, and 30.8 - 55.9 % in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2. Significant amounts of

2 were detected in the product solutions when lower selectivities towards

3 were observed (32.2 - 49.8 % in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2, 22.5 - 55.4 % in EmmimNTf

2), whereas still small amount of

4, varying in the range 3.0 - 11.9 % in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2 and 4.9 - 14.5 % in EmmimNTf

2, were formed at any of the reaction conditions, except in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2, at 180 °C and at [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅75.0, when selectivity towards

4 was found to be 24.0 %. Where performances are similar for the two classes of cation ammonium cations should be chosen due to their greater ease of synthesis.

3.3. Ionic Liquid Effect

Ionic liquids were found to enhance the performance of the HTID– SAC reaction with regards to both substrate conversion and selectivity towards

3. For example, when reacting 1,3-PDO in the presence of

Ir-5H and K

2CO

3 for 1 day at 120 °C, [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅195.0 and [Base]:[1,3-PDO] ≅ 0.031, 35 % less 1,3-PDO is converted in the absence of ionic liquid (52 %) as compared to the reaction run in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2 (87 %) (see entries 19 and 4, respectively, in

Table 1). The selectivity towards

3 falls to 60.4 % (as compared to 80.6 % in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2), while

2 and

4 increase to 9.8 and 29.8 %, respectively (as compared to 4.0 and 15.3 %, respectively, in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2). The ionic liquids tested were also found to enhance the performance of the HTID – SAC reaction targeting

3 when compared to a traditional organic solvent such as toluene. For example, when reacting 1,3-PDO at the same conditions, but in toluene, only 70 % conversion of 1,3-PDO was observed (see entry 20 in

Table 1); remarkably, the selectivity towards

3 resulted as low as 7.4 %, while that towards

2 increased to 92.6%, and no traces of

4 were observed, revealing a significant increase in SAC in the ionic liquids, compared to toluene.

Both EmmimNTf2 and N1,8,8,8NTf2 are stable throughout the HTID reactions. Monitoring diagnostic resonances displayed by the1H NMR spectra of the HTID – SAC reacting mixtures shows that no decomposition of the ionic liquids occurs at any of the experimental conditions tested. The triplet at δH 0.86 due to the -CH2CH3 methylic protons, the singlet at 2.92 due to the -NCH3 protons, and the multiplet at δH 3.18 due to the -NCH2- protons of N1,8,8,8NTf2 remain unchanged throughout the reaction time. No changes are observed either for the monitored resonances corresponding to the proton atoms of EmmimNTf2, namely the triplet at δH 1.51 and the quartet at δH 4.14 due to the -CH2CH3 methylic and methylenic protons, respectively, or the two doublets at δH 7.62 and 7.63 due to the two inequivalent HC=CH imidazolic protons.

Although the performance of the HTID – SAC reaction towards the selective production of 3 was found to be highly satisfactory in both N1,8,8,8NTf2 and EmmimNTf2, the former proved to be a more convenient solvent medium as mono-phasic, homogeneous product solutions were obtained using N1,8,8,8NTf2, whereas the three aldehydes 2, 3, and 4 were distributed among two phases in the product solutions obtained in EmmimNTf2. The recycling of both the catalyst and the ionic liquid, as well as isolation of products, can be managed more efficiently in N1,8,8,8NTf, adding to advantages in the life cycle and synthesis of the ammonium cation over the imidazolium cation.

3.4. 1,3-PDO and Water Effect

Reacting 1,3-PDO in neat 1,3-PDO instead of ionic liquids enhances turnover frequencies. For example, when using

Ir-3F as the catalyst precursor, at the same molar concentrations used in EmmimNTf

2, at 150 °C, [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅195.0, and [Base]:[1,3-PDO] ≅ 0.031, the turnover frequencies were found to increase to 1.41·10

−3 s

−1, as compared to 0.81·10

−3 s

−1 in EmmimNTf

2 (see entries 19 and 14 in

Table 2, respectively). A remarkable increase in selectivity towards

3 (71.1 %) was also observed (in EmmimNTf

2: 47.9 %); correspondingly, the selectivity towards

2 fell to 23.5 % (in EmmimNTf

2: 46.9 %), while that towards

4 changed little, resulting 5.4 % in neat 1,3-PDO and 5.2 % in EmmimNTf

2.

Only minor effects on the HTID – SAC reaction outcome were observed in the presence of water. Conversions and selectivities towards

3 remain high when water is added to the reaction mixture. For example, when reacting 1,3-PDO in the presence of

Ir-5H and K

2CO

3, at [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅ 75.0 and [Base]:[1,3-PDO] ≅ 0.031, in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2, at 150 °C, in the presence of 3.0 g of water, 77 % conversion of 1,3-PDO was observed, as compared to 84 % in the absence of water (see entries 1 in Tables 3 and 5 in Table 1, respectively), while the selectivity towards

3 resulted 68.2 % (as compared to 75.8 %, in the absence of water). As for the minor side-products, the selectivity towards

2 increased to 23.8% (as compared to 7.6%, in the absence of water), and that towards

4 decreased to 8.1 % (as compared to 16.7 %, in the absence of water). As expected for a condensation reaction, water usually affects SAC reactions. While SAC scarcely proceeds when performed under neat conditions, indicating that the presence of water is essential, excess amount of water, on the other hand, results in lower yields of the aldol product. When producing 2-methyl-pentane-1,3-diol (to then dehydrate to

3) from

2 via SAC in the presence of the amino amide Pro-NH

2 as the catalyst, Y. Hayashi and co-workers found that yields of the aldol product, while changing in the range 23-48 % varying the amount of water in the range 1-50 equivalent to

2, fell to 14 % if the amount of water was increased to 100 equivalents. [

33] The ability to operate the HTID – SAC reaction transforming 1,3-PDO into

3, in the presence of significant amount of water, is remarkable, and presumably a function of operating the reaction in a hydrophobic ionic liquid. It may be possible to directly extract products of fermentation from concentrated broth [

7], then use the ionic liquid solution for the chemocatalytic reaction directly, in a version of one-pot combined bio- and chemo-catalysis [

6]. Operating reactions in ionic liquids can also improve the separation of volatile products due to their low volatility [

16]. EmmimNTf

2 and N

1,8,8,8NTf

2 have been selected to representative common classes of hydrophobic ionic liquids.

Table 3.

Reaction of 1,3-PDO in the presence of

1-5H or

1-3F ([1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅ 75.0) and K

2CO

3 ([K

2CO

3]:[1,3-PDO] ≅ 0.031), at 150 °C, in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2, and water: conversion

a of 1,3-PDO, selectivity towards

2,

3, and

4, and TOF

b (Entries 1-2 correspond to those in

Tables S10 and S20).

Table 3.

Reaction of 1,3-PDO in the presence of

1-5H or

1-3F ([1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅ 75.0) and K

2CO

3 ([K

2CO

3]:[1,3-PDO] ≅ 0.031), at 150 °C, in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2, and water: conversion

a of 1,3-PDO, selectivity towards

2,

3, and

4, and TOF

b (Entries 1-2 correspond to those in

Tables S10 and S20).

| Entry |

Catalyst |

1,3-PDO conversiona

|

2 |

3 |

4 |

TOFb

|

| |

|

[%] |

|

|

|

[s−1](×103) |

| 1 |

Ir-5H |

77 |

23.8 |

68.2 |

8.1 |

0.63 |

| 2 |

Ir-3F |

71 |

11.2 |

75.6 |

13.2 |

0.63 |

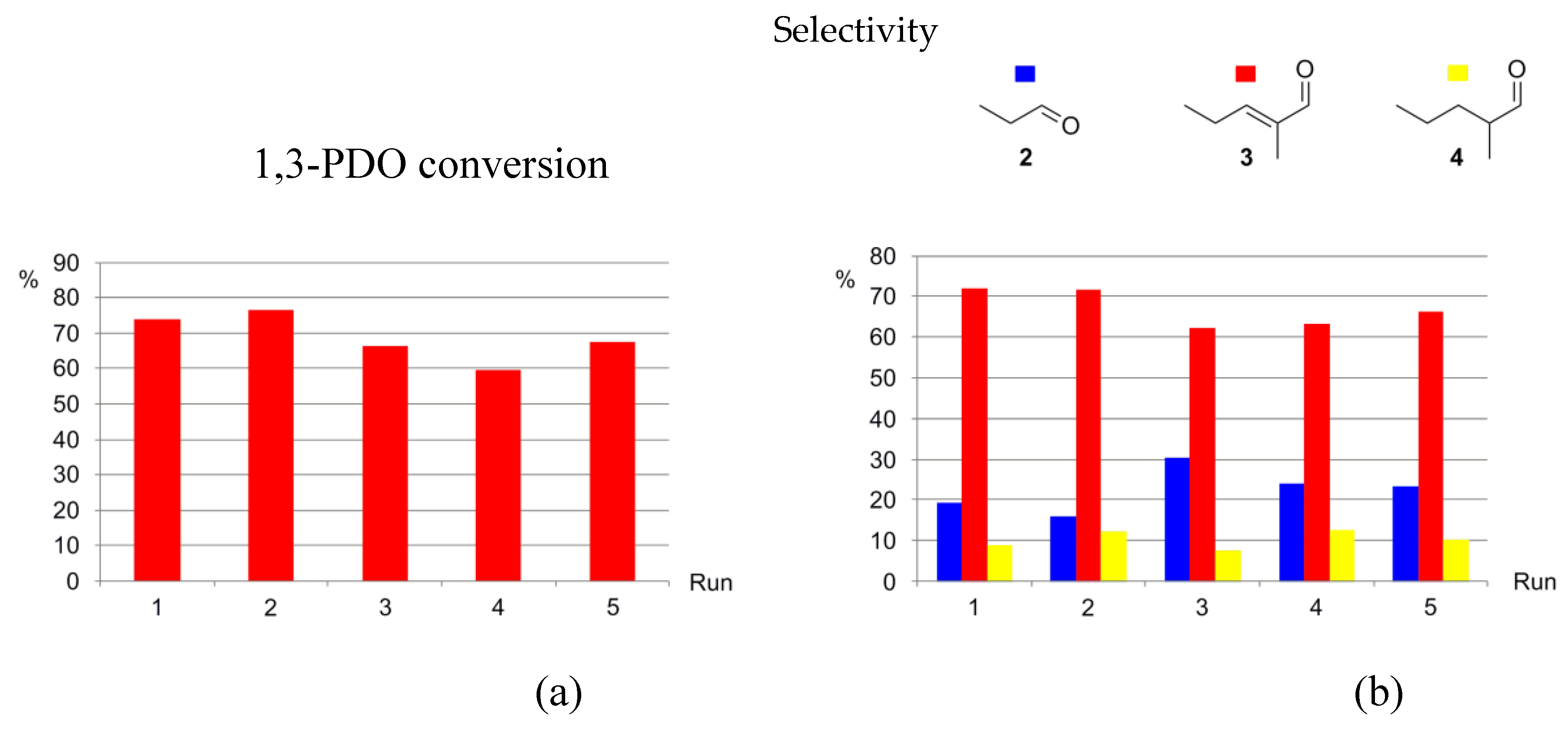

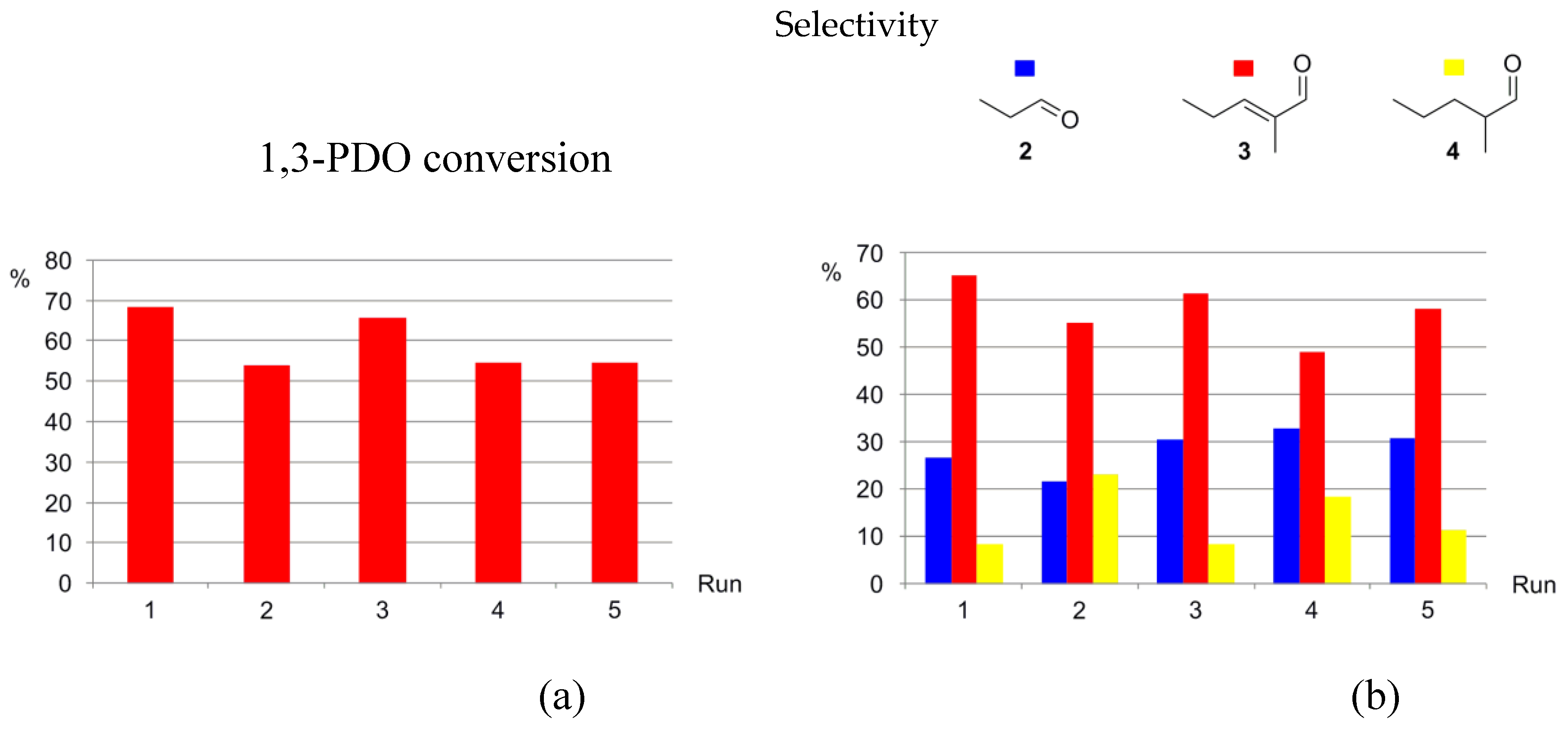

3.5. Catalysts Recycling

The recyclability of the catalytic systems generated by precursors

1-5H and

1-3F towards the selective production of

3 from 1,3-PDO via HTID – SAC was investigated in N

1,8,8,8NTf

2, in the presence of K

2CO

3, at catalyst loading [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅ 75.0, at both 120 and 150 °C. Both the catalyst precursors, and the ionic liquid, were found to be recyclable. For example,

1-5H was successfully re-used for five runs at 120 °C: running the HTID – SAC reaction for one day, the average conversion of 1,3-PDO was found 74 and 68 % after the first and last recycling run, respectively, with average selectivity towards

3 72.1 and 66.3 %, respectively (see tables S11 and S12, and

Figure 7). At the same conditions, in the presence of

1-3F, average conversions after three days varied in the range 69 - 54 %, while the average selectivity toward

3 was found to be 65.1 and 58.1 % after the first and last recycling run, respectively (see

Tables S13 and S14, and

Figure 8). The catalytic system generated by precursors

1-5H and

1-3F remains active and selective over five runs also at 150 °C. In the presence of

1-5H, the average selectivity towards

3 after the first and last recycling run (one day reaction) was 72.6 and 66.0 %, respectively (see tables S15 and S16); the average conversions of 1,3-PDO, after a 13 % drop in the second run, change little over the following runs (first run: 72 %; second run: 59 %; last run: 54 %). In the presence of

1-3F, the conversion of 1,3-PDO varies in the range 83 – 67 % (three days reaction), the selectivity towards

3 being 75.2 and 63.8 after the first and last run, respectively (see

Table S17, and

Figure 9). The ionic liquid N

1,8,8,8NTf

2 is stable throughout the 5 recycling runs: the

1H NMR spectra of the DMSO-d

6 solutions of the reacting mixture show that the triplet at

δH 0.86 due to the -CH

2CH

3 methylic protons, the singlet at

δH 2.92 due to the -NCH

3 protons, and the multiplet at

δH 3.18 due to the -NCH

2- protons of N

1,8,8,8NTf

2 remain unchanged through the reactions of the 5 recycling runs.

The pre-catalysts

1-5H [

16] and

1-3F [

17] were previously demonstrated to be recyclable for at least ten runs in the selective production of

2 directly from 1,3-PDO via HTID, operating at 0.35 bar, in both ionic liquids N

1,8,8,8NTf

2 and EmmimNTf

2, in the presence of K

2CO

3, at catalyst loading [1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅ 75.0 and 220, at both 120 and 150 °C.

The catalytic system and the ionic liquid are re-used without any treatment in between recycles for the selective production of

3. In a similar reactivity context, the ionic liquid [bmim][BF

4] was found to be recyclable by C. P. Mehnert and co-workers in the synthesis of the C9 aldehyde 2,4-dimethyl-hept-2-enal via cross-aldol reaction of

2 and

4, in which the C9 condensation product is obtained, at 95 °C, with selectivities (up to 80 %) higher than in water (59 %) [

25,

26]. After removing the organic sodium salts, mostly carboxylic sodium derivatives formed in side-reactions of the aldol condensation process from the assisting basic sodium salts, the ionic liquid could be efficiently re-used for three further recycles in the production of 2,4-dimethyl-hept-2-enal, and also as solvent medium for additional aldol reactions.

Further improvement of the catalytic system’s recyclability and separations may be achievable by using a basic ionic liquid as both the reaction medium and catalyst (the assisting base in both the HTID and SAC) for producing aldol condensation products directly from 1,3-PDO. We have demonstrated the application of a basic ionic liquid gel to the production of

2 by HTID [

18]. However, although that would be feasible with regards to only SAC, and it has been reported by C. P. Mehnert and co-workers, [

26] our studies suggest that a critical concentration of base affords the most efficient HTID. Under and above the critical concentration of the assisting base, both selectivity and yields of

2 decrease significantly, requiring adjustment of base concentration between runs [

16,

17]. In instances where salt builds up in the reaction separation strategies have been suggested by Hart

et al. [

37].

Figure 1.

Structure of complexes 1-5H and 1-3F, catalyst precursors.

Figure 1.

Structure of complexes 1-5H and 1-3F, catalyst precursors.

Figure 2.

Structure of ionic liquids EmmimNTf2 and N1,8,8,8NTf2, tested as the solvent media.

Figure 2.

Structure of ionic liquids EmmimNTf2 and N1,8,8,8NTf2, tested as the solvent media.

Scheme 1.

Cp*IrCl2(NHC)-catalysed, base-assisted HTID of 1,3-PDO, followed by SAC, and postulated reaction mechanism.

Scheme 1.

Cp*IrCl2(NHC)-catalysed, base-assisted HTID of 1,3-PDO, followed by SAC, and postulated reaction mechanism.

Figure 3.

Example of 1H NMR spectra of the product solutions of the reaction of 1,3-PDO in the presence of 1-5H or 1-3F and K2CO3, in EmmimNTf2 or N1,8,8,8NTf2, at temperatures varying in the range 100 – 180 °C, in a closed reaction vessel (a), compared to an example of a 1H NMR spectrum of the product solutions isolated at P ≅ 0.35 bar (b): enlargement of the aldehydic region (δH 9.00 - 10.12).

Figure 3.

Example of 1H NMR spectra of the product solutions of the reaction of 1,3-PDO in the presence of 1-5H or 1-3F and K2CO3, in EmmimNTf2 or N1,8,8,8NTf2, at temperatures varying in the range 100 – 180 °C, in a closed reaction vessel (a), compared to an example of a 1H NMR spectrum of the product solutions isolated at P ≅ 0.35 bar (b): enlargement of the aldehydic region (δH 9.00 - 10.12).

Figure 4.

Reaction of 1,3-PDO in the presence of 1-3F ([1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅195.0) and K2CO3, in N1,8,8,8NTf2, at 150 °C, in a closed reaction vessel (reaction time: 3 days): effect of [Base]:[1,3-PDO] on (a) 1,3-PDO conversion, and (b) selectivity towards 2, 3, and 4.

Figure 4.

Reaction of 1,3-PDO in the presence of 1-3F ([1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅195.0) and K2CO3, in N1,8,8,8NTf2, at 150 °C, in a closed reaction vessel (reaction time: 3 days): effect of [Base]:[1,3-PDO] on (a) 1,3-PDO conversion, and (b) selectivity towards 2, 3, and 4.

Figure 5.

Reaction of 1,3-PDOin the presence of 1-5H ([1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅75.0 and 195.0), and K2CO3, in N1,8,8,8NTf2, in a closed reaction vessel: (a) 1,3-PDO conversion; (b) selectivity towards 2, 3, and 4.

Figure 5.

Reaction of 1,3-PDOin the presence of 1-5H ([1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅75.0 and 195.0), and K2CO3, in N1,8,8,8NTf2, in a closed reaction vessel: (a) 1,3-PDO conversion; (b) selectivity towards 2, 3, and 4.

Figure 6.

Reaction of 1,3-PDO in the presence of 1-3F ([1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅75.0 and 195.0), and K2CO3, in N1,8,8,8NTf2, in a closed reaction vessel: (a) 1,3-PDO conversion; (b) selectivity towards 2, 3, and 4.

Figure 6.

Reaction of 1,3-PDO in the presence of 1-3F ([1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅75.0 and 195.0), and K2CO3, in N1,8,8,8NTf2, in a closed reaction vessel: (a) 1,3-PDO conversion; (b) selectivity towards 2, 3, and 4.

Figure 7.

Recycling 1-5H as the catalyst precursor for the HTID – SAC reaction of 1,3-PDO ([1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅ 75.0) in N1,8,8,8NTf2, in the presence of K2CO3 ([K2CO3]:[1,3-PDO] ≅ 0.031), at 120 °C, in a closed reaction vessel (reaction time: 1 d): (a) 1,3-PDO conversion (duplicates); (b) selectivity towards 2, 3, and 4 (duplicates).

Figure 7.

Recycling 1-5H as the catalyst precursor for the HTID – SAC reaction of 1,3-PDO ([1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅ 75.0) in N1,8,8,8NTf2, in the presence of K2CO3 ([K2CO3]:[1,3-PDO] ≅ 0.031), at 120 °C, in a closed reaction vessel (reaction time: 1 d): (a) 1,3-PDO conversion (duplicates); (b) selectivity towards 2, 3, and 4 (duplicates).

Figure 8.

Recycling 1-3F as the catalyst precursor for the HTID – SAC reaction of 1,3-PDO ([1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅ 75.0) in N1,8,8,8NTf2, in the presence of K2CO3 ([K2CO3]:[1,3-PDO] ≅ 0.031), at 120 °C, in a closed reaction vessel (reaction time: 3 d): (a) 1,3-PDO conversion (duplicates); (b) selectivity towards 2, 3, and 4 (duplicates).

Figure 8.

Recycling 1-3F as the catalyst precursor for the HTID – SAC reaction of 1,3-PDO ([1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅ 75.0) in N1,8,8,8NTf2, in the presence of K2CO3 ([K2CO3]:[1,3-PDO] ≅ 0.031), at 120 °C, in a closed reaction vessel (reaction time: 3 d): (a) 1,3-PDO conversion (duplicates); (b) selectivity towards 2, 3, and 4 (duplicates).

Figure 9.

Recycling 1-3F as the catalyst precursor for the HTID – SAC reaction of 1,3-PDO ([1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅ 75.0) in N1,8,8,8NTf2, in the presence of K2CO3 ([K2CO3]:[1,3-PDO] ≅ 0.031), at 150 °C, in a closed reaction vessel (reaction time: 3 d): (a) 1,3-PDO conversion; (b) selectivity towards 2, 3, and 4.

Figure 9.

Recycling 1-3F as the catalyst precursor for the HTID – SAC reaction of 1,3-PDO ([1,3-PDO]:[Ir] ≅ 75.0) in N1,8,8,8NTf2, in the presence of K2CO3 ([K2CO3]:[1,3-PDO] ≅ 0.031), at 150 °C, in a closed reaction vessel (reaction time: 3 d): (a) 1,3-PDO conversion; (b) selectivity towards 2, 3, and 4.

Table 1.

Reaction of 1,3-PDO in the presence of

1-5H and K

2CO

3, in ionic liquids: conversion

a of 1,3-PDO, selectivity towards

2,

3, and

4, and TOF

b (Entries 1-24 correspond to those in

Table S1).

Table 1.

Reaction of 1,3-PDO in the presence of

1-5H and K

2CO

3, in ionic liquids: conversion

a of 1,3-PDO, selectivity towards

2,

3, and

4, and TOF

b (Entries 1-24 correspond to those in

Table S1).

| Entry |

Solvent |

Catalyst |

[1,3-PDO]:[Ir] |

Base |

[Base]:[1,3-PDO] |

T |

Time |

1,3-PDO conversiona

|

2 |

3 |

4 |

TOFb

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

[°C] |

[d] |

[%] |

[%] |

[%] |

[%] |

[s−1] (×103) |

| 1 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

Ir-5H |

71.9 |

K2CO3

|

0.0310 |

100 |

4 |

79 |

7.1 |

79.4 |

13.5 |

0.16 |

| 2 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

Ir-5H |

193.8 |

K2CO3

|

0.0312 |

100 |

4 |

79 |

3.9 |

78.1 |

18.0 |

0.44 |

| 3 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

Ir-5H |

72.2 |

K2CO3

|

0.0304 |

120 |

1 |

82 |

9.3 |

77.5 |

13.2 |

0.17 |

| 4 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

Ir-5H |

193.5 |

K2CO3

|

0.0307 |

120 |

1 |

87 |

4.0 |

80.6 |

15.3 |

0.49 |

| 5 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

Ir-5H |

72.2 |

K2CO3

|

0.0306 |

150 |

1 |

84 |

7.6 |

75.8 |

16.7 |

0.23 |

| 6 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

Ir-5H |

189.4 |

K2CO3

|

0.0306 |

150 |

1 |

89 |

4.6 |

76.9 |

18.5 |

0.65 |

| 7 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

Ir-5H |

69.5 |

K2CO3

|

0.0312 |

180 |

1 |

94 |

6.9 |

76.3 |

16.8 |

0.76 |

| 8 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

Ir-5H |

194.8 |

K2CO3

|

0.0309 |

180 |

1 |

98 |

6.9 |

69.4 |

23.6 |

2.23 |

| 9 |

EmmimNTf2

|

Ir-5H |

72.4 |

K2CO3

|

0.0301 |

100 |

7 |

77 |

7.5 |

79.2 |

13.3 |

0.16 |

| 10 |

EmmimNTf2

|

Ir-5H |

191.9 |

K2CO3

|

0.0301 |

100 |

7 |

77 |

10.2 |

80.3 |

9.5 |

0.43 |

| 11 |

EmmimNTf2

|

Ir-5H |

77.0 |

K2CO3

|

0.0302 |

120 |

4 |

60 |

8.1 |

78.4 |

13.5 |

0.10 |

| 12 |

EmmimNTf2

|

Ir-5H |

187.4 |

K2CO3

|

0.0311 |

120 |

4 |

44 |

1.8 |

82.2 |

15.9 |

0.33 |

| 13 |

EmmimNTf2

|

Ir-5H |

76.5 |

K2CO3

|

0.0307 |

150 |

3 |

85 |

19.7 |

67.1 |

13.2 |

0.25 |

| 14 |

EmmimNTf2

|

Ir-5H |

194.3 |

K2CO3

|

0.0305 |

150 |

3 |

68 |

6.2 |

75.5 |

18.3 |

0.51 |

| 15 |

EmmimNTf2

|

Ir-5H |

71.7 |

K2CO3

|

0.0309 |

180 |

1 |

88 |

43.8 |

42.4 |

13.8 |

0.41 |

| 16 |

EmmimNTf2

|

Ir-5H |

196.1 |

K2CO3

|

0.0307 |

180 |

1 |

93 |

53.0 |

37.3 |

9.7 |

2.15 |

| 17 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

No catalyst |

/ |

K2CO3

|

0.0318 |

120 |

1 |

1 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

/ |

| 18 |

EmmimNTf2

|

No catalyst |

/ |

K2CO3

|

0.0307 |

150 |

3 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| 19 |

No IL |

Ir-5H |

179.8 |

K2CO3

|

0.0311 |

120 |

1 |

52 |

9.8 |

60.4 |

29.8 |

1.07 |

| 20 |

Toluene |

Ir-5H |

177.8 |

K2CO3

|

0.0315 |

120 |

1 |

70 |

92.6 |

7.4 |

0.0 |

1.45 |

| 21 |

1,3-PDOc

|

Ir-5H |

191.6 |

K2CO3

|

0.0305 |

120 |

3 |

138 |

30.5 |

65.2 |

4.3 |

1.02 |

| 22 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

Ir-5H |

180.1 |

No base |

/ |

150 |

3 |

0 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

0.00 |

| 23 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

Ir-5H |

183.0 |

K2CO3

|

0.0151 |

150 |

3 |

23 |

34.0 |

55.4 |

10.5 |

0.16 |

| 24 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

Ir-5H |

185.7 |

K2CO3

|

0.0762 |

150 |

3 |

12 |

36.2 |

44.6 |

19.2 |

0.08 |

Table 2.

Reaction of 1,3-PDO in the presence of

1-3F and K

2CO

3, in ionic liquids: conversion

a of 1,3-PDO, selectivity towards

2,

3, and

4, and TOF

b (Entries 1-22 correspond to those in

Table S2).

Table 2.

Reaction of 1,3-PDO in the presence of

1-3F and K

2CO

3, in ionic liquids: conversion

a of 1,3-PDO, selectivity towards

2,

3, and

4, and TOF

b (Entries 1-22 correspond to those in

Table S2).

| Entry |

Solvent |

[1,3-PDO]:[Ir] |

Base |

[Base]:[1,3-PDO] |

T |

Time |

1,3-PDO conversiona

|

2 |

3 |

4 |

TOFb

|

| |

|

|

|

|

[°C] |

[d] |

[%] |

[%] |

[%] |

[%] |

[s−1] (×103) |

| 1 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

78.2 |

K2CO3

|

0.0309 |

100 |

7 |

73 |

44.2 |

50.0 |

5.8 |

0.09 |

| 2 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

215.5 |

K2CO3

|

0.0296 |

100 |

7 |

97 |

46.5 |

48.4 |

5.1 |

0.35 |

| 3 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

76.2 |

K2CO3

|

0.0304 |

120 |

5 |

99 |

42.4 |

53.4 |

4.2 |

0.18 |

| 4 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

196.0 |

K2CO3

|

0.0318 |

120 |

5 |

99 |

49.8 |

47.3 |

3.0 |

0.45 |

| 5 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

77.6 |

K2CO3

|

0.0310 |

150 |

3 |

99 |

8.3 |

82.1 |

9.7 |

0.30 |

| 6 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

204.6 |

K2CO3

|

0.0310 |

150 |

3 |

99 |

8.0 |

86.6 |

5.4 |

0.79 |

| 7 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

77.2 |

K2CO3

|

0.0306 |

180 |

1 |

99 |

45.2 |

30.8 |

24.0 |

0.89 |

| 8 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

212.0 |

K2CO3

|

0.0303 |

180 |

1 |

99 |

32.2 |

55.9 |

11.9 |

2.45 |

| 9 |

EmmimNTf2

|

77.7 |

K2CO3

|

0.0302 |

100 |

7 |

99 |

44.7 |

50.4 |

4.9 |

0.13 |

| 10 |

EmmimNTf2

|

187.7 |

K2CO3

|

0.0309 |

100 |

7 |

99 |

18.4 |

70.9 |

10.7 |

0.31 |

| 11 |

EmmimNTf2

|

86.1 |

K2CO3

|

0.0279 |

120 |

5 |

98 |

22.5 |

64.8 |

12.7 |

0.20 |

| 12 |

EmmimNTf2

|

212.2 |

K2CO3

|

0.0310 |

120 |

5 |

99 |

12.2 |

76.0 |

11.9 |

0.49 |

| 13 |

EmmimNTf2

|

79.1 |

K2CO3

|

0.0300 |

150 |

3 |

99 |

55.4 |

35.7 |

8.9 |

0.31 |

| 14 |

EmmimNTf2

|

210.7 |

K2CO3

|

0.0308 |

150 |

3 |

99 |

46.9 |

47.9 |

5.2 |

0.81 |

| 15 |

EmmimNTf2

|

77.7 |

K2CO3

|

0.0312 |

180 |

1 |

99 |

44.1 |

41.4 |

14.5 |

0.90 |

| 16 |

EmmimNTf2

|

209.0 |

K2CO3

|

0.0310 |

180 |

1 |

99 |

28.1 |

63.5 |

8.4 |

2.42 |

| 17 |

No IL |

207.1 |

K2CO3

|

0.0322 |

120 |

5 |

78 |

56.5 |

43.5 |

0.0 |

0.37 |

| 18 |

Toluene |

204.6 |

K2CO3

|

0.0308 |

120 |

3 |

76 |

90.9 |

9.1 |

0.0 |

0.60 |

| 19 |

1,3-PDOc

|

207.1 |

K2CO3

|

0.0307 |

150 |

3 |

/ |

23.5 |

71.1 |

5.4 |

1.41 |

| 20 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

203.5 |

No base |

/ |

150 |

3 |

0 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

0.00 |

| 21 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

200.4 |

K2CO3

|

0.0148 |

150 |

3 |

39 |

37.2 |

44.2 |

18.6 |

0.30 |

| 22 |

N1,8,8,8NTf2

|

178.6 |

K2CO3

|

0.0769 |

150 |

3 |

16 |

33.0 |

45.5 |

21.5 |

0.11 |