Submitted:

18 June 2024

Posted:

19 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

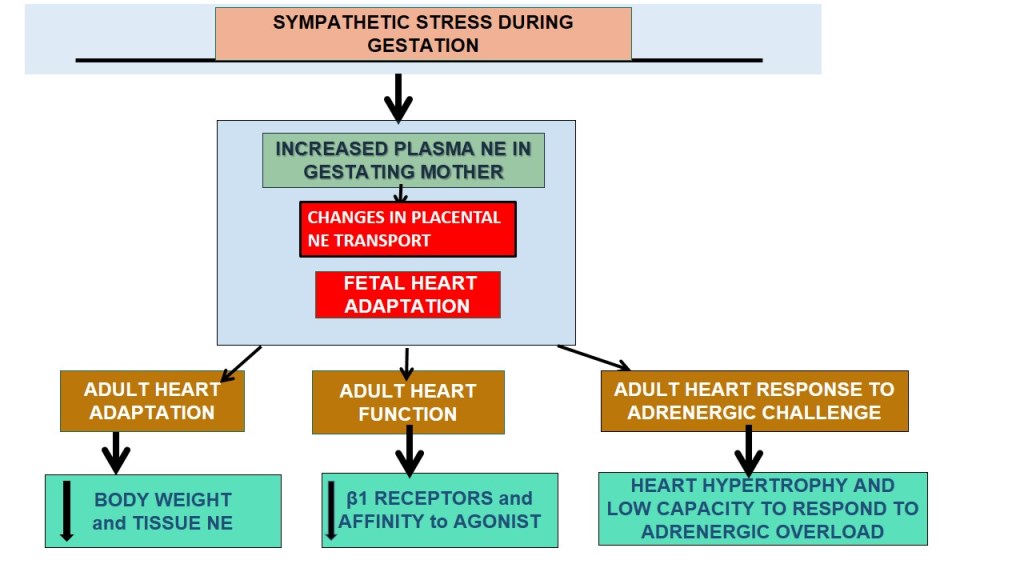

1. Introduction

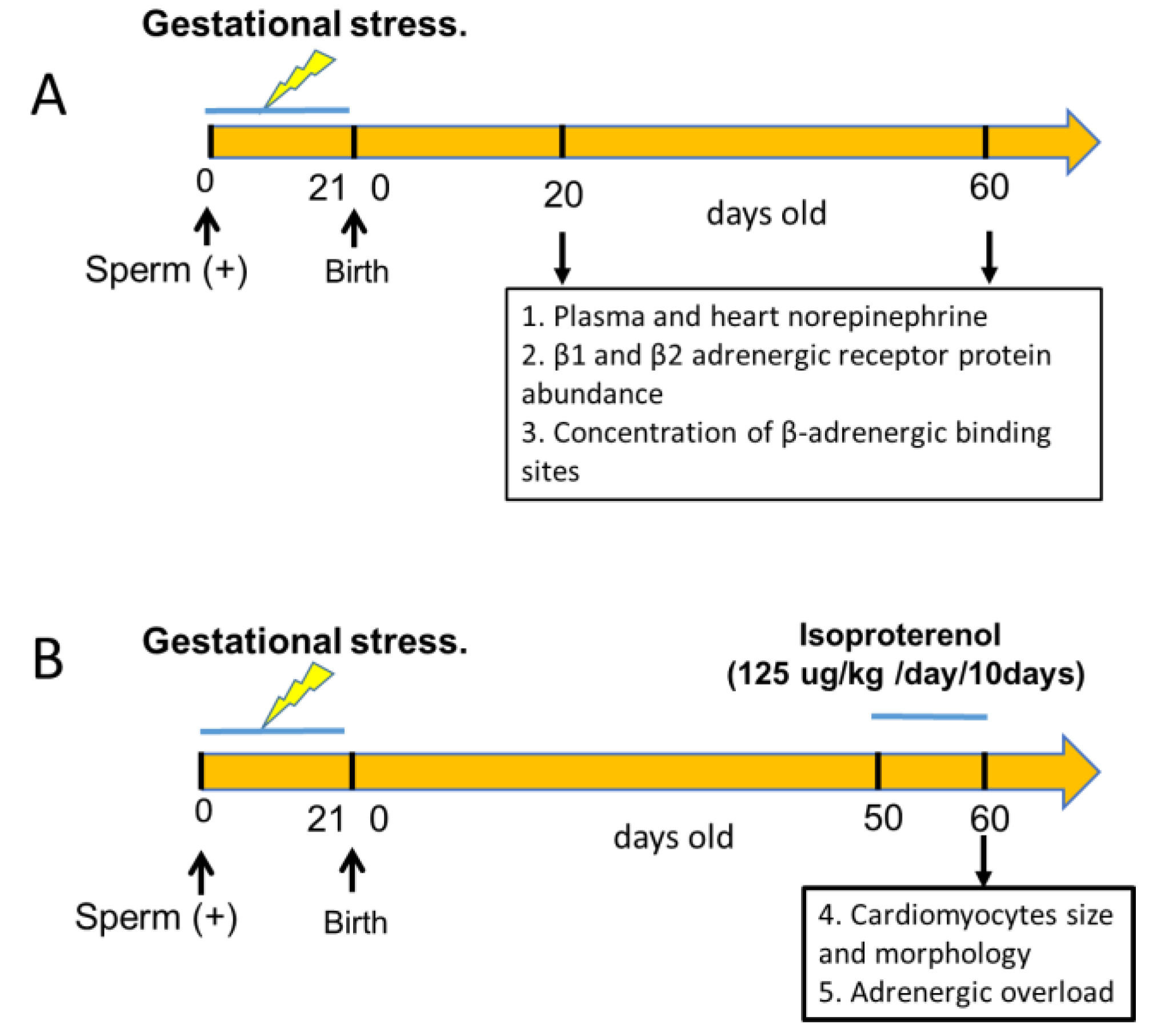

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gestational Stress Induction

2.2. Adrenergic Overload Protocol

2.3. Quantification of NE Levels

2.4. Determination of plasma glucose

2.5. Plasma insulin determination by ELISA kit

2.6. Binding of [3H]dihydroalprenolol to Cardiac Membranes

2.6.1. Preparation of the Crude Membrane Fraction

2.6.2. Assay for β-Adrenergic Receptors

2.7. Determination of Cardiac β1- and β2-Adrenergic Receptor mRNA

| Genes | Forward | Reverse |

| 18S | 5’-TCAAGAACGAAAGTCGGAGG-3’ | 5’-GGACATCTAAGGGCATCACA-3’ |

| β1AR | 5’-TCGTAGTGGGCAACGTGTTGGTGAT-3’ | 5’-GTCTACGAAGTCCAGAGCTCACAGAA-3’ |

| β2AR | 5’-CAGGCCTATGCTATCGCTTCCTCTAT-3’ | 5’-GGCTGAGGTTTTGGGCATGAAATC-3’ |

2.8. Determination of Cardiac β1- and β2-Adrenergic Receptors by Western Blot

2.9. Morphometric Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

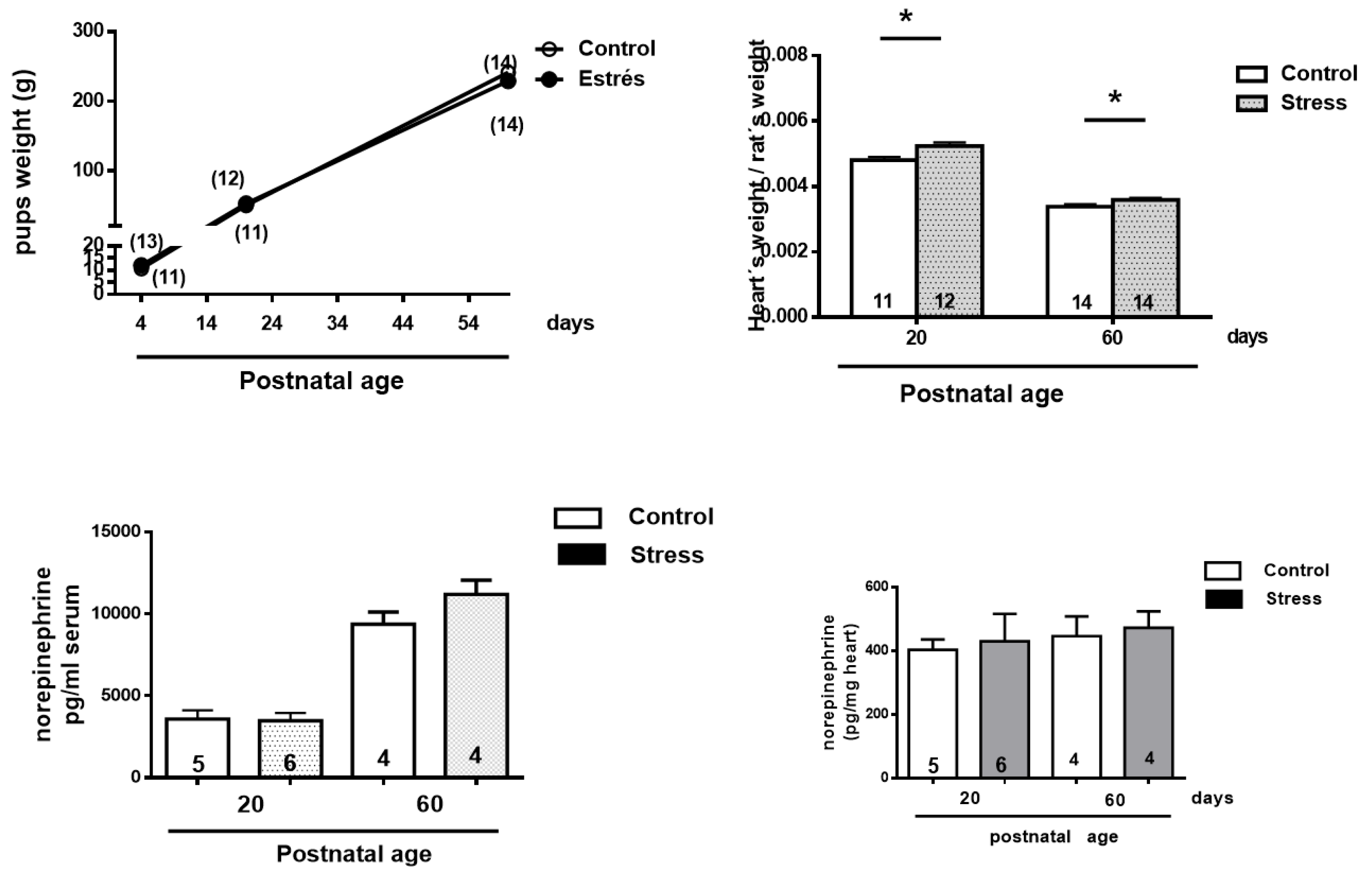

3.1. Animal and Heart Relative Weight

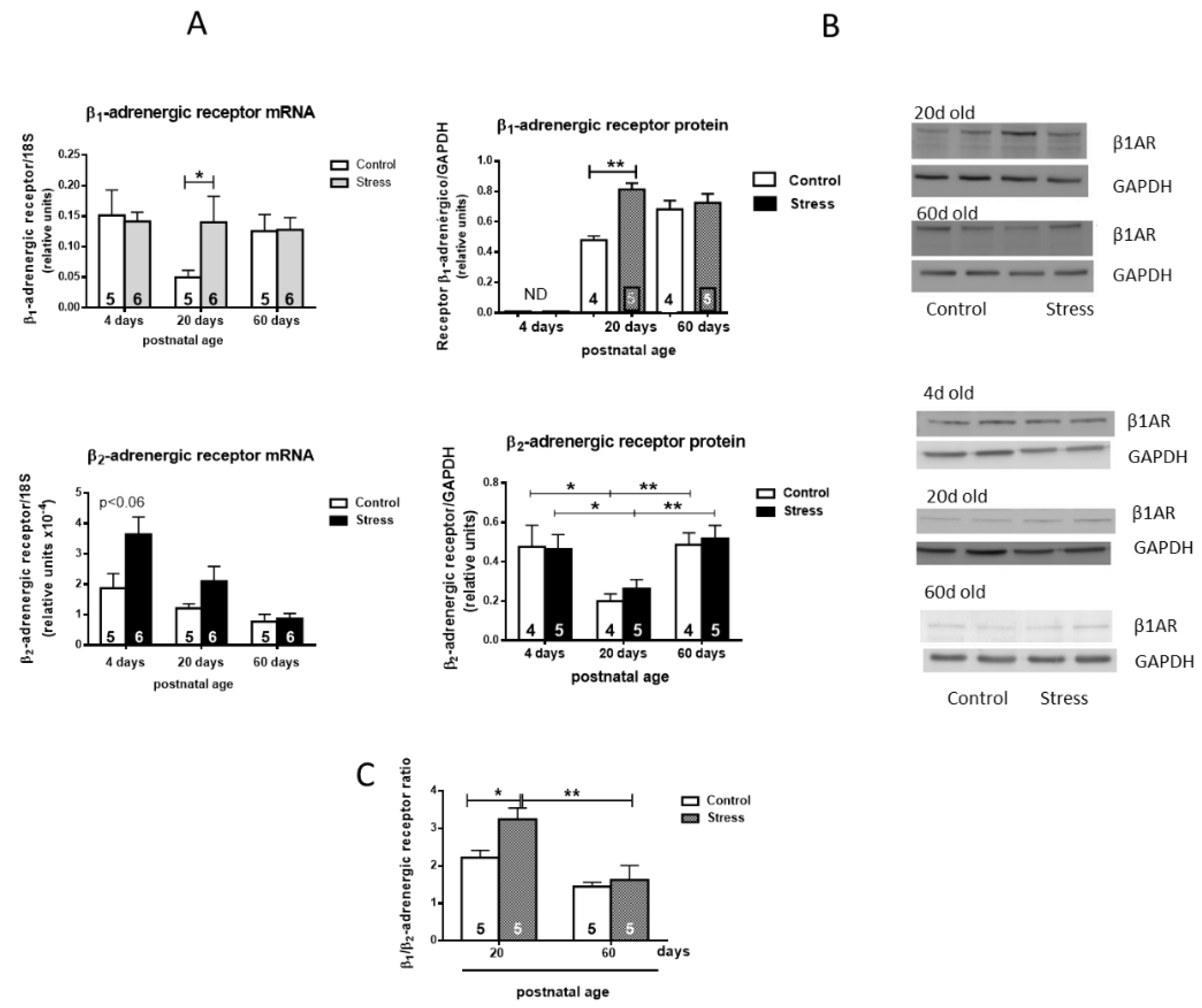

3.2. Changes in β1 and β2 Adrenergic Receptor Protein Abundance

3.3. Concentration of β-Adrenergic Binding Sites

3.4. Effects of Isoproterenol on Ventricle Size and Cardiomyocyte Area in Gestationally Stressed Rats

3.5. Cardiac Functional Parameters in Stressed Offspring Challenged with Isoproterenol Overload

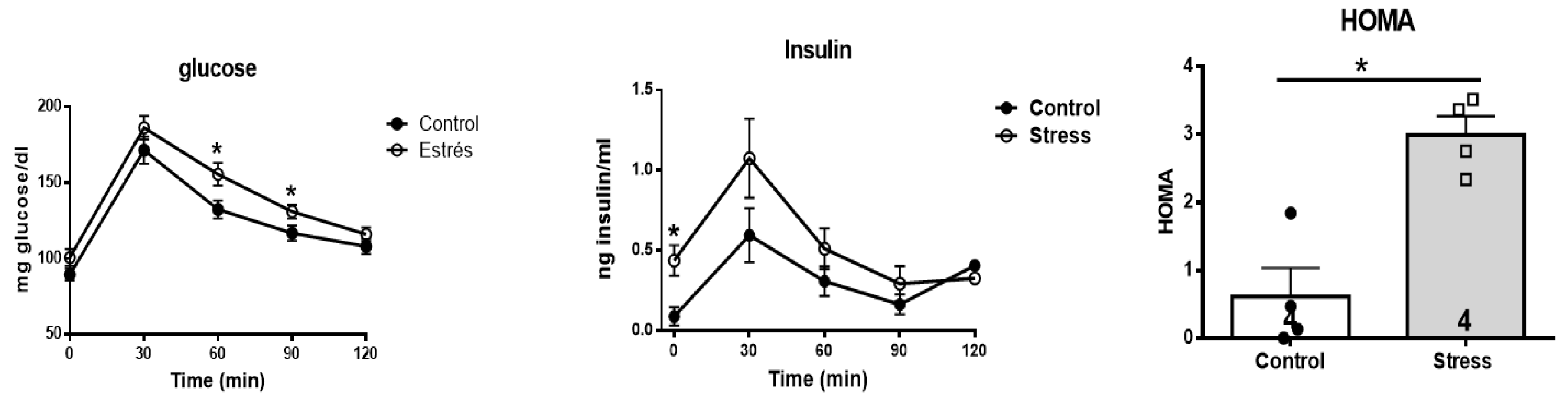

3.6. Effect of stress on the glycemic and insulin response to a glucose overload

4. Discussion

Effects of Gestational Stress in the Heart

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cottrell EC, Seckl JR. Prenatal stress, glucocorticoids and the programming of adult disease. Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:19. [CrossRef]

- Kajantie E. Fetal origins of stress-related adult disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1083:11-27. [CrossRef]

- Hales CN, Barker DJ. The thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Br Med Bull. 2001;60:5-20. [CrossRef]

- Godfrey KM, Barker DJ. Fetal programming and adult health. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4(2B):611-24. [CrossRef]

- Phillips DI, Jones A, Goulden PA. Birth weight, stress, and the metabolic syndrome in adult life. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1083:28-36. [CrossRef]

- Lim K, Zimanyi MA, Black MJ. Effect of maternal protein restriction in rats on cardiac fibrosis and capillarization in adulthood. Pediatr Res. 2006;60(1):83-7. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Twinn DS, Ekizoglou S, Wayman A, Petry CJ, Ozanne SE. Maternal low-protein diet programs cardiac beta-adrenergic response and signaling in 3-mo-old male offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291(2):R429-36.

- Igosheva N, Klimova O, Anishchenko T, Glover V. Prenatal stress alters cardiovascular responses in adult rats. J Physiol. 2004;557(Pt 1):273-85. [CrossRef]

- Piquer B, Fonseca JL, Lara HE. Gestational stress, placental norepinephrine transporter and offspring fertility. Reproduction. 2017;153(2):147-55. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein DS, Kopin IJ. Adrenomedullary, adrenocortical, and sympathoneural responses to stressors: a meta-analysis. Endocr Regul. 2008;42(4):111-9.

- Pacak K, Palkovits M, Yadid G, Kvetnansky R, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS. Heterogeneous neurochemical responses to different stressors: a test of Selye's doctrine of nonspecificity. Am J Physiol. 1998;275(4 Pt 2):R1247-55. [CrossRef]

- Writing Group M, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38-360.

- Benedict CR, Fillenz M, Stanford C. Noradrenaline release in rats during prolonged cold-stress and repeated swim-stress. Br J Pharmacol. 1979;66(4):521-4. [CrossRef]

- Dorfman M, Arancibia S, Fiedler JL, Lara HE. Chronic intermittent cold stress activates ovarian sympathetic nerves and modifies ovarian follicular development in the rat. Biol Reprod. 2003;68(6):2038-43. [CrossRef]

- Dorfman M, Ramirez VD, Stener-Victorin E, Lara HE. Chronic-intermittent cold stress in rats induces selective ovarian insulin resistance. Biol Reprod. 2009;80(2):264-71. [CrossRef]

- Barra R, Cruz G, Mayerhofer A, Paredes A, Lara HE. Maternal sympathetic stress impairs follicular development and puberty of the offspring. Reproduction. 2014;148(2):137-45. [CrossRef]

- Piquer B, Ruz F, Barra R, Lara HE. Gestational Sympathetic Stress Programs the Fertility of Offspring: A Rat Multi-Generation Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(5). [CrossRef]

- Lian S, Wang D, Xu B, Guo W, Wang L, Li W, et al. Prenatal cold stress: Effect on maternal hippocampus and offspring behavior in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2018;346:1-10. [CrossRef]

- Sun D, Chen K, Wang J, Zhou L, Zeng C. In-utero cold stress causes elevation of blood pressure via impaired vascular dopamine D1 receptor in offspring. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2020;42(2):99-104. [CrossRef]

- Piquer B, Olmos D, Flores A, Barra R, Bahamondes G, Diaz-Araya G, et al. Exposure of the Gestating Mother to Sympathetic Stress Modifies the Cardiovascular Function of the Progeny in Male Rats. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(5). [CrossRef]

- Ayala P, Montenegro J, Vivar R, Letelier A, Urroz PA, Copaja M, et al. Attenuation of endoplasmic reticulum stress using the chemical chaperone 4-phenylbutyric acid prevents cardiac fibrosis induced by isoproterenol. Exp Mol Pathol. 2012;92(1):97-104. [CrossRef]

- Luna SL, Neuman S, Aguilera J, Brown DI, Lara HE. In vivo beta-adrenergic blockade by propranolol prevents isoproterenol-induced polycystic ovary in adult rats. Horm Metab Res. 2012;44(9):676-81.

- AVMA. American Veterinary Medical Association Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition. 2020.

- Muniyappa R, Chen H, Muzumdar RH, Einstein FH, Yan X, Yue LQ, et al. Comparison between surrogate indexes of insulin sensitivity/resistance and hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp estimates in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297(5):E1023-9. [CrossRef]

- Kruger NJ. The Bradford method for protein quantitation. Methods Mol Biol. 1994;32:9-15.

- Barria A, Leyton V, Ojeda SR, Lara HE. Ovarian steroidal response to gonadotropins and beta-adrenergic stimulation is enhanced in polycystic ovary syndrome: role of sympathetic innervation. Endocrinology. 1993;133(6):2696-703. [CrossRef]

- Lara HE, Porcile A, Espinoza J, Romero C, Luza SM, Fuhrer J, et al. Release of norepinephrine from human ovary: coupling to steroidogenic response. Endocrine. 2001;15(2):187-92. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura K, Fushimi K, Kouchi H, Mihara K, Miyazaki M, Ohe T, et al. Inhibitory effects of antioxidants on neonatal rat cardiac myocyte hypertrophy induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and angiotensin II. Circulation. 1998;98(8):794-9. [CrossRef]

- Zar J. Biostatistical Analysis. second edition ed. NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984 1984. 5 p.

- Benjamin IJ, Jalil JE, Tan LB, Cho K, Weber KT, Clark WA. Isoproterenol-induced myocardial fibrosis in relation to myocyte necrosis. Circ Res. 1989;65(3):657-70. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta P. The Laboratory Rat: Relating Its Age With Human's. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(6):624-30.

- Ricu M, Paredes A, Greiner M, Ojeda SR, Lara HE. Functional development of the ovarian noradrenergic innervation. Endocrinology. 2008;149(1):50-6. [CrossRef]

- Burnstock G, Verkhratsky A. Vas deferens--a model used to establish sympathetic cotransmission. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31(3):131-9. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Gareri C, Rockman HA. G-Protein-Coupled Receptors in Heart Disease. Circ Res. 2018;123(6):716-35. [CrossRef]

- Bristow MR, Altman NL. Heart Rate in Preserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(11):792-4. [CrossRef]

- Jevjdovic T, Dakic T, Kopanja S, Lakic I, Vujovic P, Jasnic N, et al. Sex-Related Effects of Prenatal Stress on Region-Specific Expression of Monoamine Oxidase A and beta Adrenergic Receptors in Rat Hearts. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019;112(1):67-75.

- Galvez A, Paredes A, Fiedler JL, Venegas M, Lara HE. Effects of adrenalectomy on the stress-induced changes in ovarian sympathetic tone in the rat. Endocrine. 1999;10(2):131-5.

- Elmes MJ, Haase A, Gardner DS, Langley-Evans SC. Sex differences in sensitivity to beta-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol in the isolated adult rat heart following prenatal protein restriction. Br J Nutr. 2009;101(5):725-34.

- Bristow MR, Ginsburg R, Umans V, Fowler M, Minobe W, Rasmussen R, et al. Beta 1- and beta 2-adrenergic-receptor subpopulations in nonfailing and failing human ventricular myocardium: coupling of both receptor subtypes to muscle contraction and selective beta 1-receptor down-regulation in heart failure. Circ Res. 1986;59(3):297-309. [CrossRef]

- Cayupe B, Morgan C, Puentes G, Valladares L, Burgos H, Castillo A, et al. Hypertension in Prenatally Undernourished Young-Adult Rats Is Maintained by Tonic Reciprocal Paraventricular-Coerulear Excitatory Interactions. Molecules. 2021;26(12). [CrossRef]

- Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Rev. 2000;21(1):55-89. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).