Submitted:

17 June 2024

Posted:

17 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

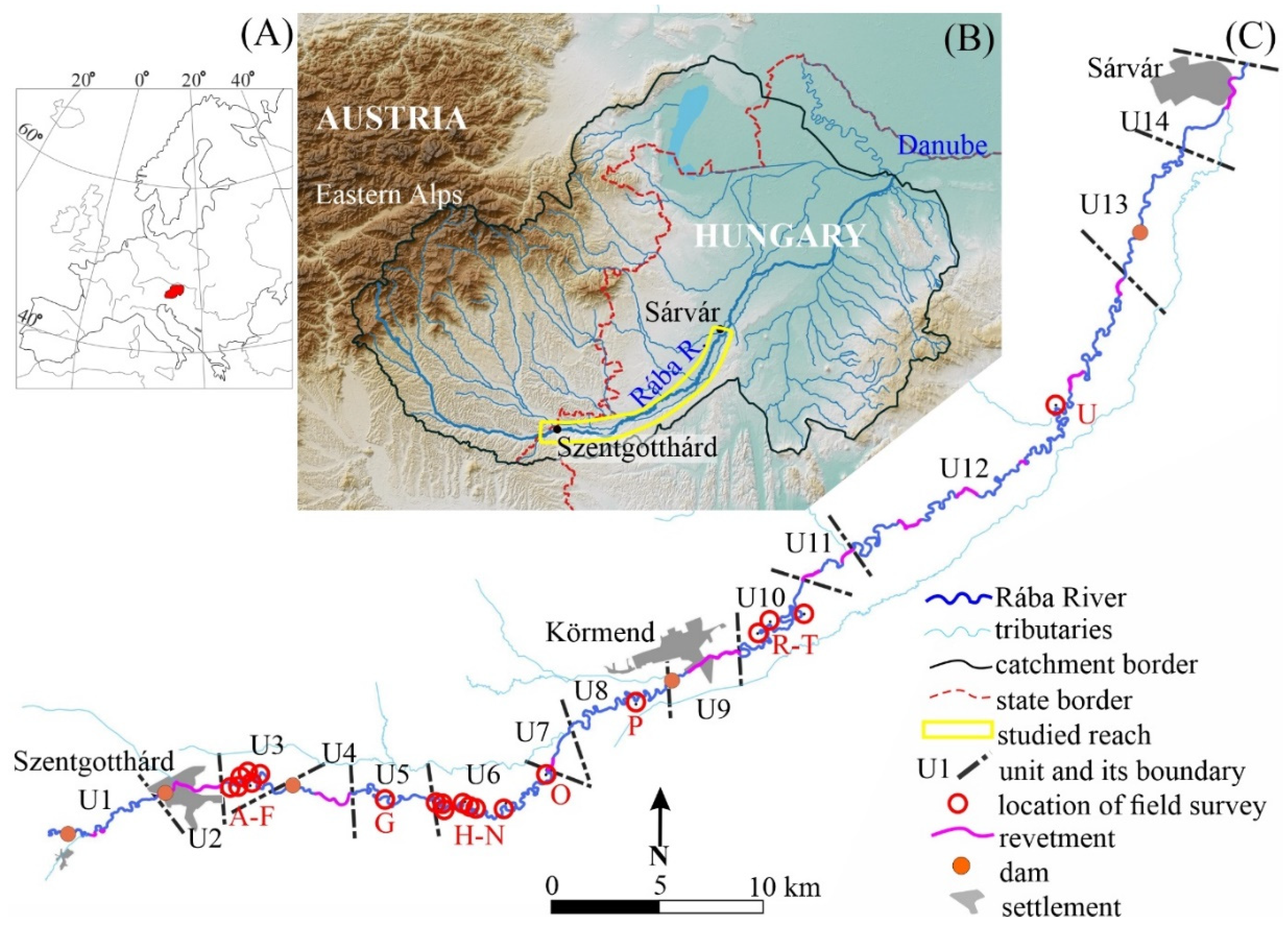

2. Study Area

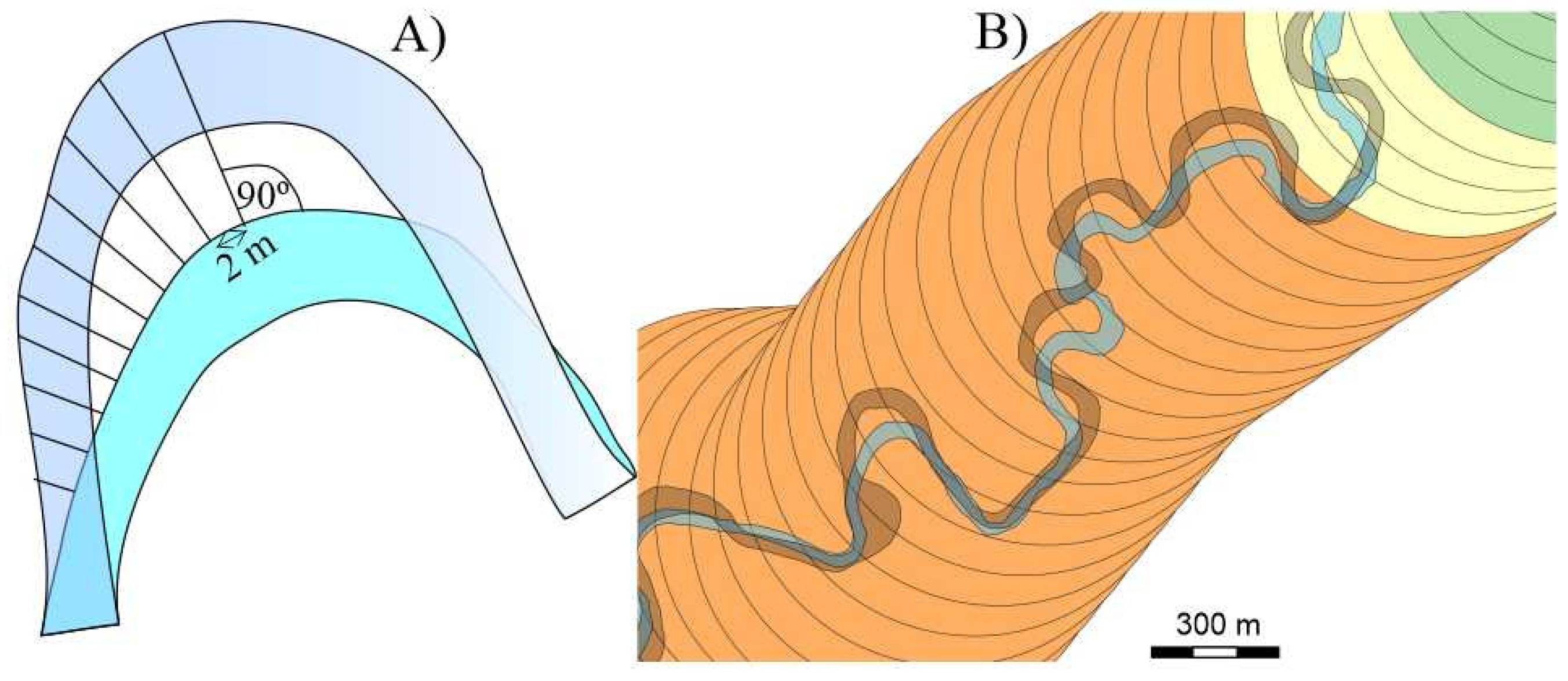

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

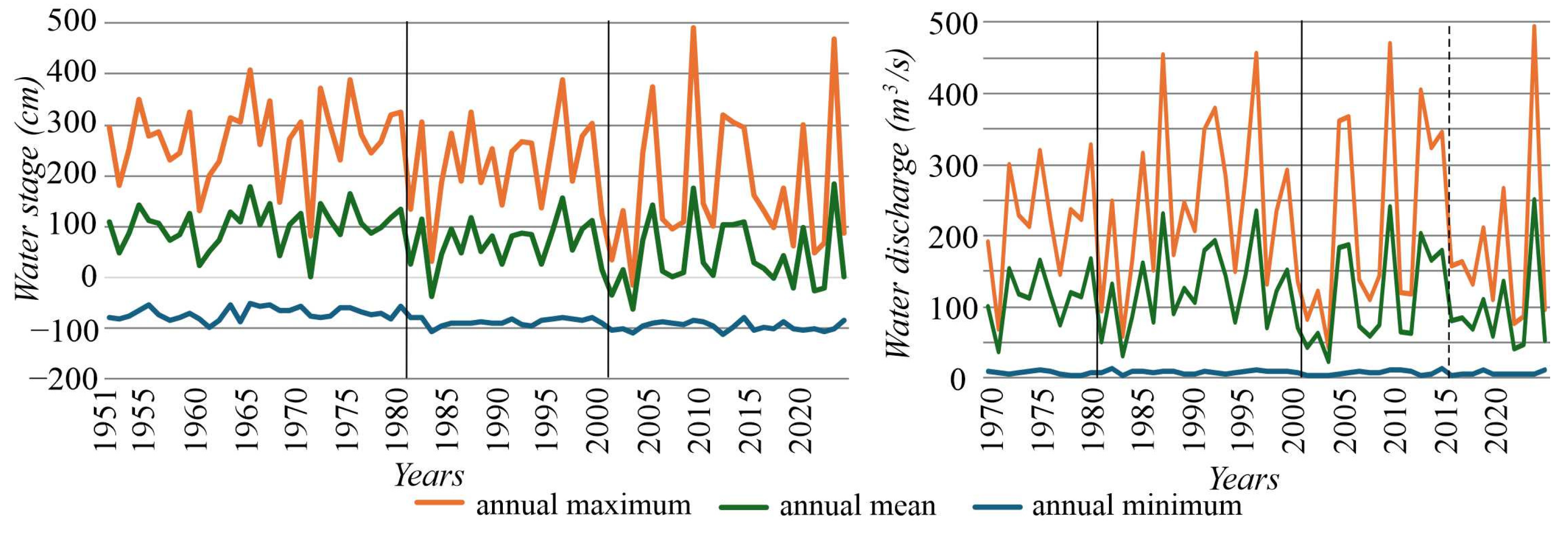

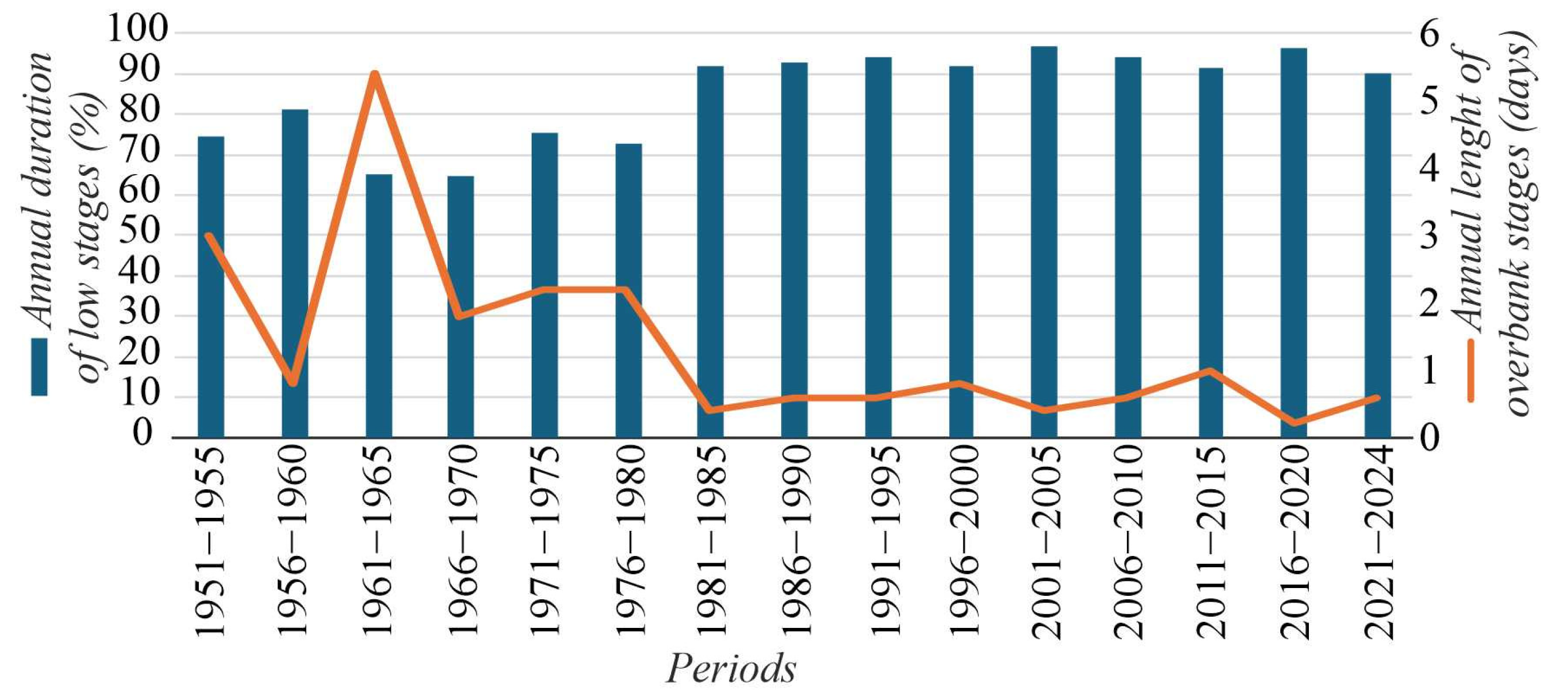

4.1. Hydrological Changes of the Rába River (1950–2024)

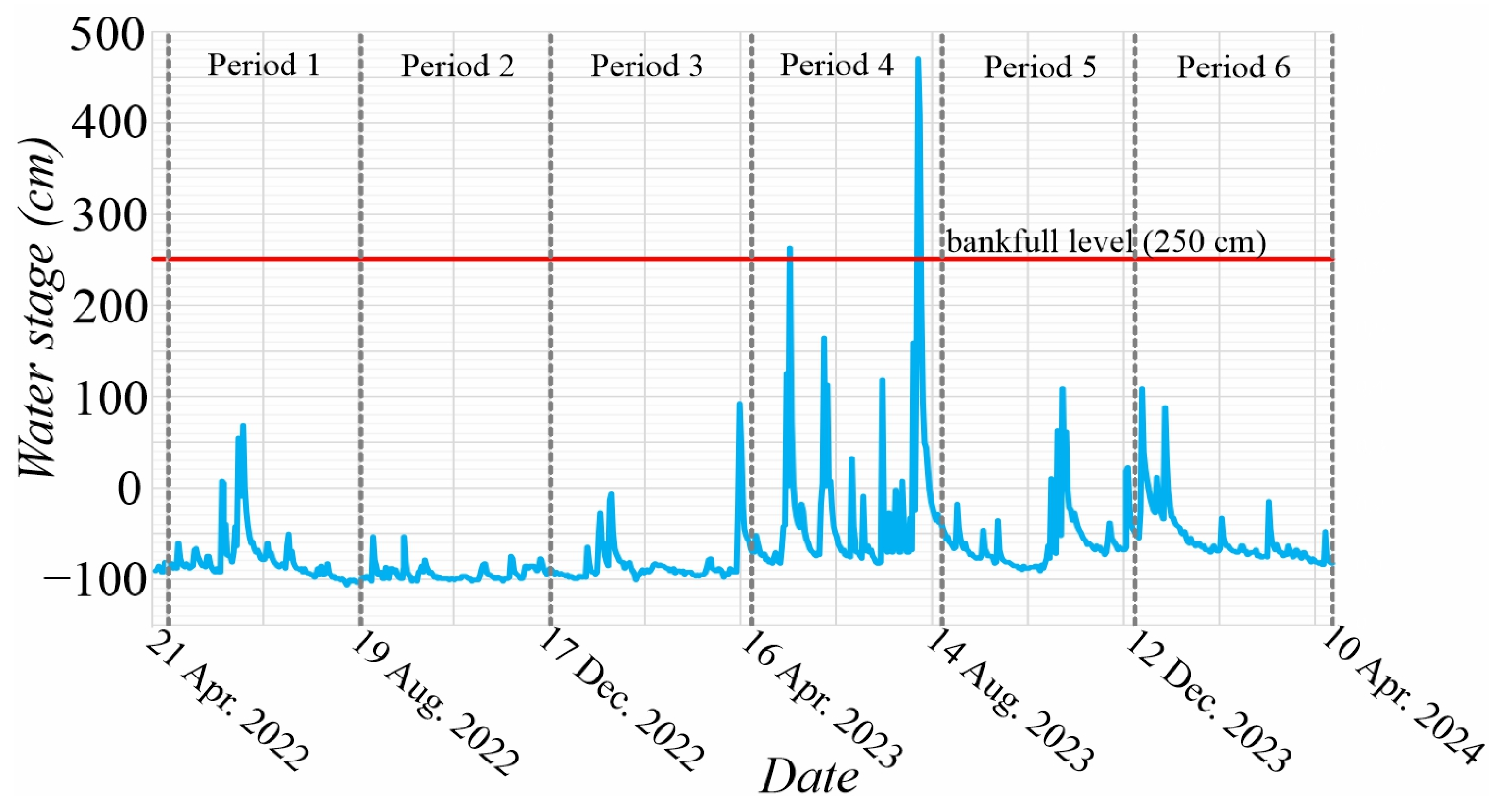

4.2. Hydrological Changes of the Rába River (2022–2024) during the Field Surveys

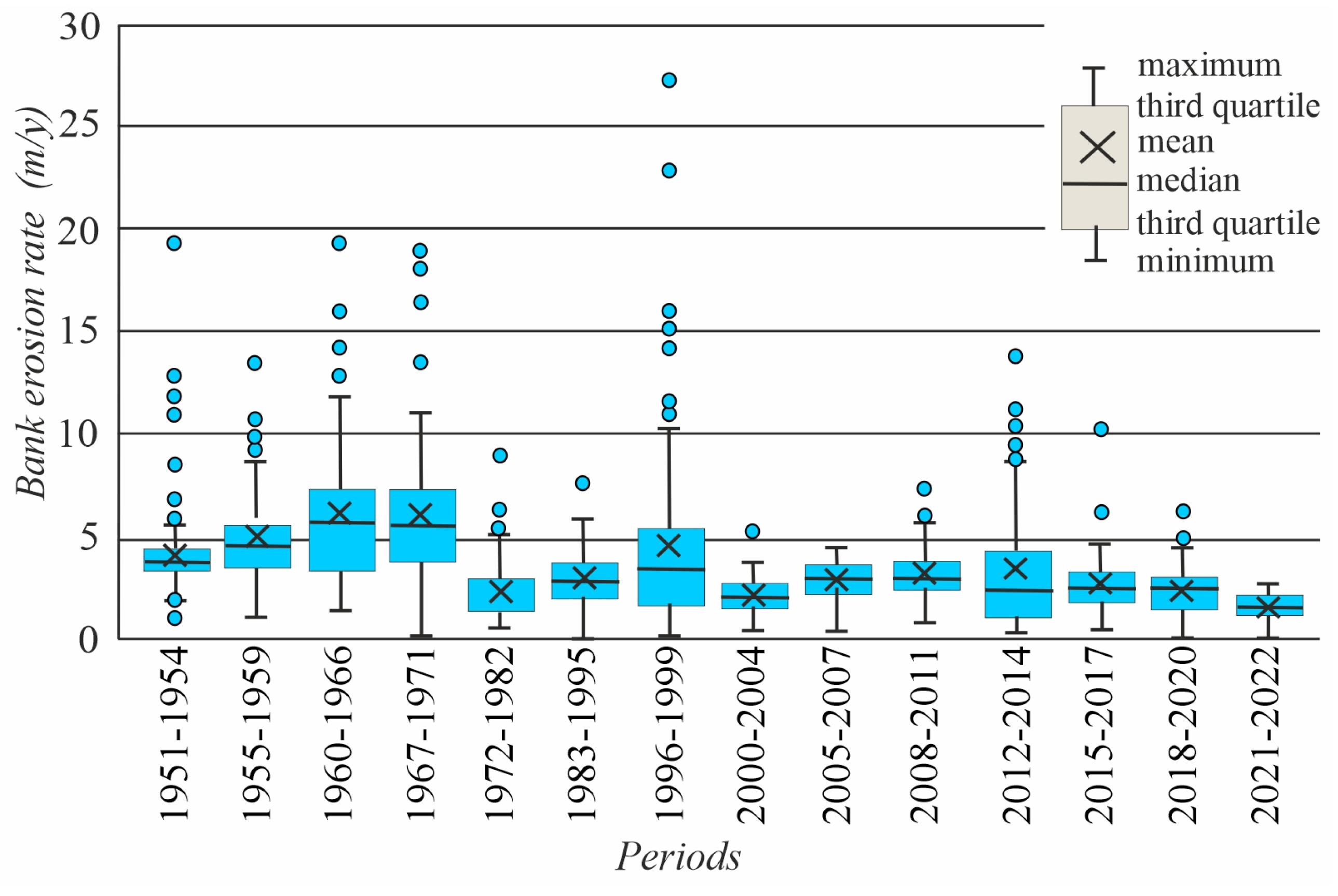

4.3. Bank Erosion of the Studied Reach of the Rába between 1951 and 2022

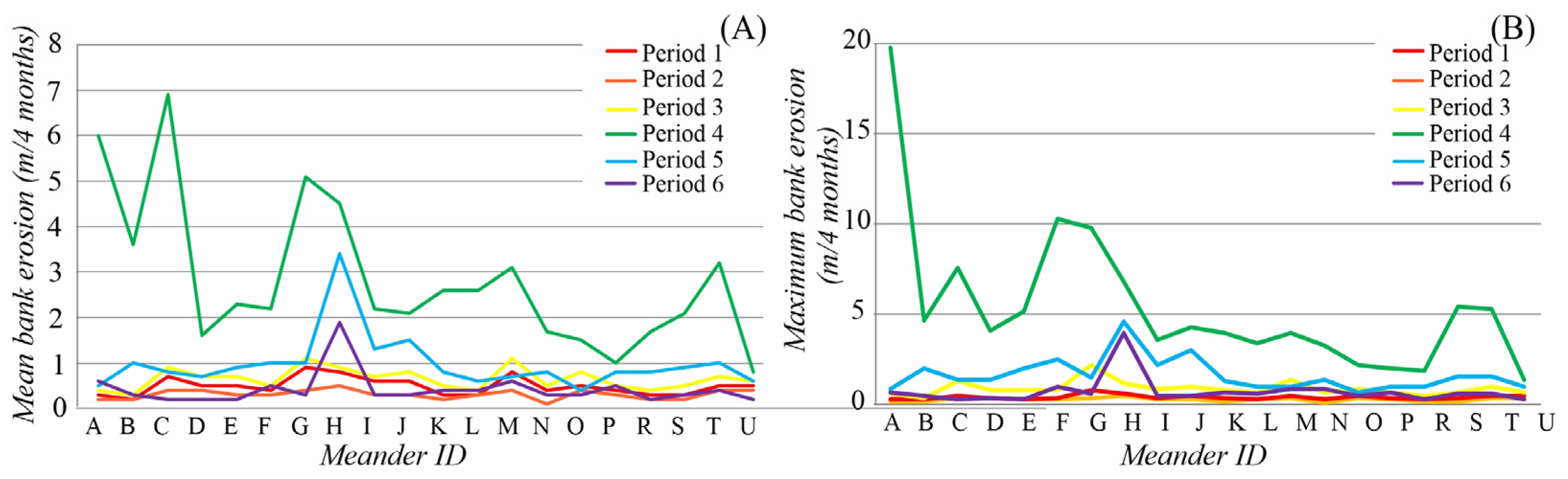

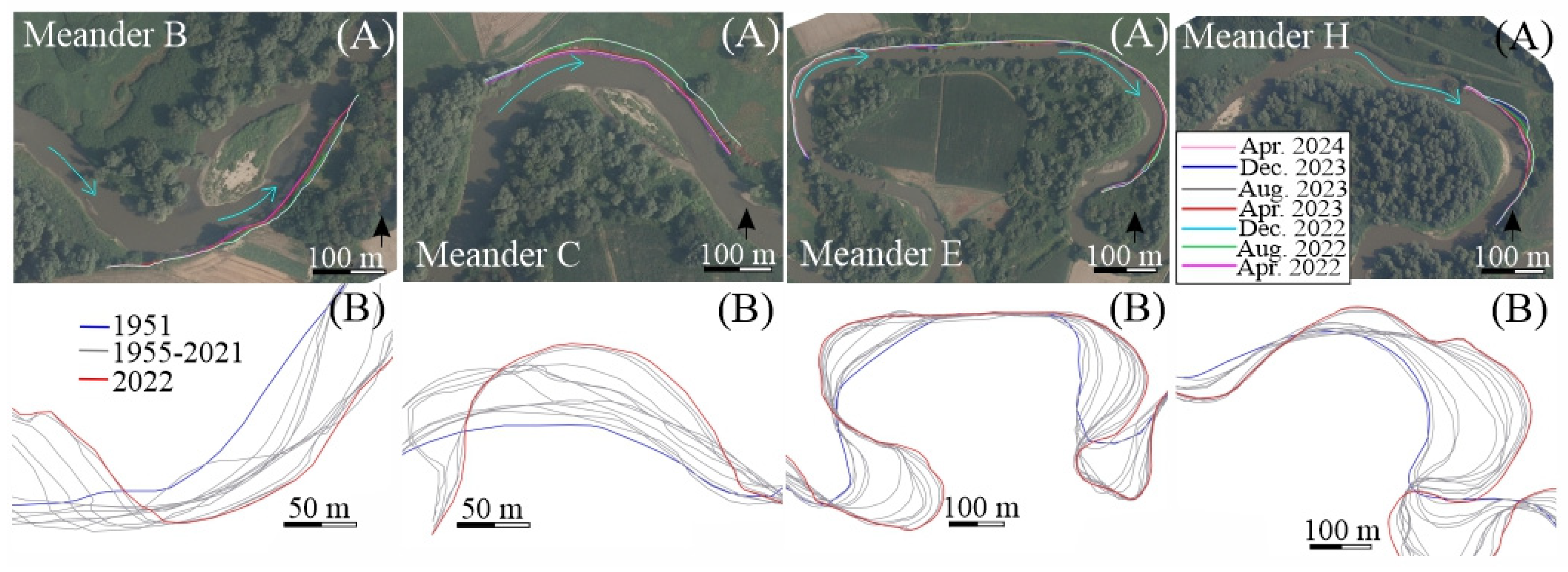

4.4. Bank Erosion of the Selected Meanders of the Rába between 2022 and 2024

4. Discussion

4.1. Hydrological Alteration of the Rába River Since 1950

4.2. The Relationship between Hydrology and Bank Erosion

4.3. Relationship between Hydrology and Bank Erosion: A Conceptual Model

4.4. Spatiality of Bank Erosion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flannigan, M.D.; Stocks, B.J.; Wotton, B.M. Climate change and forest fires. Science of the Total Environment 2000, 262, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munka, C.; Cruz, G.; Caffera, R.M. Long term variation in rainfall erosivity in Uruguay: a preliminary Fournier approach. GeoJournal 2007, 70, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, G.R. Climate and Rivers. River Res. and Applic. 2019, 35, 1119–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werritty, A.; Leys, K.F. The sensitivity of Scottish rivers and upland valley floors to recent environmental change. Catena 2001, 42, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyzga, B. A review on channel incision in the Polish Carpathian rivers during the 20th century. Developments in Earth Surf. Proc. 2007, 11, 525–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, N.J.; Al-Khafaji, A.S.; Alwan, I.A. Investigation of rivers planform change in a semi-arid region of high vulnerability to climate change: A case study of Tigris River and its tributaries in Iraq. Reg. Stud. in Marine Sci. 2023, 68, 2352–4855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, J.C. Large increases in flood magnitude in response to modest changes in climate. Nature 1993, 361, 430–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, J.C. Long-term episodic changes in magnitudes and frequencies of floods in the upper Mississippi River valley. In: Fluvial Processes and Environmental Change. Eds.: Brown, A.G., Quine, T.A., Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1999, pp. 255–282.

- Feng, X.; Zhang, G.; Yin, X. Hydrological responses to climate change in Nenjiang River basin, Northeastern China. Water Res. Manag. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.; Laize, C.L.R.; Acreman, M.C.; Floerke, M. How will climate change modify river flow regimes in Europe? Hydrology and Earth Syst. Sci. [CrossRef]

- Blöschl, G.; Hall, J.; Viglione, A.; et al. Changing climate both increases and decreases European river floods. Nature 2019, 573, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondolf, G.M.; Piégay, H.; Landon, N. Channel response to increased and decreased bedload supply from land use change: contrasts between two catchments. Geomorphology 2002, 45, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, S.N.; Richards, K.S. Linking river channel form and process: time, space and causality revisited. Earth Surf. Proc. and Landforms 1997, 22, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilvear, D.; Winterbottom, S.; Sichingabula, H. Character of channel planform change and meander development: Luangwa River, Zambia. Earth Surf. Proc. Landforms 2000, 25, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsden, D. A critical assessment of the sensitivity concept in geomorphology. Catena 200, 42, 99-123. [CrossRef]

- Radoane, M.; Obreja, F.; Cristea, I.; Mihailă, D. Changes in the channel-bed level of the eastern Carpathian rivers: Climatic vs. human control over the last 50 years. Geomorphology 2013, 193, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalai, Z.; Balogh, J.; Jakab, G. Riverbank erosion in Hungary – with an outlook on environmental consequences. Hung. Geo. Bull. 2013, 2, 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Czigány, Sz.; Pirkhoffer, E.; Balassa, B.; Bugya, T.; Bötkös, T.; Gyenizse, P.; Nagyváradi, L.; Lóczy, D.; Geresdi, I. Flash floods as a natural hazard in Southern Transdanubia. Földrajzi Közlemények 2010, 134, 281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, F.; Gutiérrez, M.; Sancho, C. Geomorphological and sedimentological analysis of a catastrophic flash flood in the Arás drainage basin. Geomorphology 1998, 22, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorczyca, E.; Krzemien, K.; Wronska-Walach, D.; Sobucki, M. Channel changes due to extreme rainfalls int he Polish Carpathians. In: Geomorphological impacts of extreme weather. Ed.: Lóczy D., Springer: Wellington, UK, 2013; pp. 23–37.

- Dixon, S.J.; Smith, G.H.S.; Best, J.L.; Nicholas, A.P.; Bull, J.M.; Vardy, M.E.; Sarker, M.H.; Goodbred, S. The planform mobility of river channel confluences: insights from analysis of remotely sensed imagery Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 176, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehotsky, M.; Frandofer, M.; Novotny, J.; Rusnak, M.; Szmanda, J.B. Geomorphic/sedimentary responses of rivers to floods: case studies from Slovakia. In: Geomorphological impacts of extreme weather. Ed.: Lóczy D., Springer: Wellington, UK, 2013; pp. 37–53.

- Kiss, T.; Blanka, V. River channel response to climate- and human-induced hydrological changes: Case study on the meandering Hernád River, Hungary. Geomorphology 2012, 175, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, T.; Blanka, V.; Andrási, G.; Hernesz, P. 2013. Extreme Weather and the Rivers of Hungary: Rates of Bank Retreat. In: Geomorphological Impacts of Extreme Weather: Case studies from central and eastern Europe. Ed.: Lóczy D., Springer: Wellington, UK, 2013; pp. 83–99.

- Ma, F.; Ye, A.; Gong, W.; Mao, Y.; Miao, C.; Di, Z. An estimate of human and natural contributions to flood changes of the Huai River. Global and Planetary Change 2014, 119, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, K.; Read, A.; Frazier, P.; Mount, N. The effect of altered flow regime on the frequency and duration of bankfull discharge: Murrumbidgee River, Australia. River Res. Applic. 2005, 21, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, E.; Brunstein, D.; Vauchel, P.; Roulet, M.; Fuertes, O.; Guyot, J.L.; Darozzes, J.; Bourrel, L. Temporal relations between meander deformation, water discharge and sediment fluxes in the floodplain of the Rio Beni (Bolivian Amazonia). Earth Surf. Proc. and Landforms 2006, 32, 230–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, T.; Sipos, Gy. Braid-scale geometry changes in a sand-bedded river: Significance of low stages. Geomorphology 2006, 84, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkel, L. 2002. Change in the frequency of extreme events as the indicator of climatic change in the Holocene (in fluvial systems). Quat. Internat. 2007; 91, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnell, A.M.; Bertoldi, W.; Corenblit, D. Changing river channels: The roles of hydrological processes, plants and pioneer fluvial landforms in humid temperate, mixed load, gravel bed rivers. Earth-Sci. Rev. [CrossRef]

- Schumm, S.A. The Fluvial System. Wiley: New York, USA, 1977, p.338.

- Pfister, L.; Kwadijk, J.; Musy, A.; Bronstert, A.; Hoffmann, L. Climate cahnge, land use change and runoff prediction in the Rhine-Meuse basins. River Res. and Applic. 2004, 20, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, J.A.; Pasternack, G.B.; Johnson, M.L. Logging effects on sediment flux observed in a pollen based record of overbank deposition in a northern California catchment. Earth Surf. Proc. Landforms 2005, 30, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.E.; Nahar, N.; Chowdhury, N.N.; Sayanno, T.K.; Haque, S. Geomorphological changes of river Surma due to climate change. Int J Energ Water Res, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, J.C. Historical Valley Floor Sedimentation in the Upper Mississippi Valley. Annals Ass. of Am. Geogr. 1987, 77, 224–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A.P.; Brierley, G.J. Geomorphologic responses of lower Bega River to catchment disturbance. Geomorphology 1997, 18, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madej, M.A. Changes in channel-stored sediment, Redwood Creek, Northwestern California, 1947-1980. USGS Prof. Paper, 1454. [Google Scholar]

- Van De Wiel, M.J.; Coulthard, T.J.; Macklin, M.G.; Lewin, J. Modelling the response of river systems to environmental change: progress, problems and prospects for palaeo-environmental reconstructions. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2011, 104, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooke, J.M. Styles of channel change. In: Applied Fluvial Geomorphology for Engineering and Management. Eds.: Thorne, C.R., Hey, R.D., Newson, M.D., Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1997, pp. 237–268.

- Usher, M.B. Landscape sensitivity: from theory to practice. Catena 2001, 42, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.D. Nonlinear dynamical systems in geomorphology: revolution or evolution? Geomorphology 1992, 5, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.F. Landscape sensitivity in time and space, an introduction. Catena 2001, 42, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kis, A.; Szabó, P.; Pongrácz, R. Spatial and temporal analysis of drought-related climate indices for Hungary for 1971–2100. Hung. Geo. Bull. 2023, 72, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, R.; Pongrácz, I.; Hatvani, G.; Magyar, N.; Anda, A.; Kovács-Székely, I. Seasonal trends in the Early Twentieth Century Warming (ETCW) in a centennial instrumental temperature record from Central Europe. Hung. Geo. Bull. 2024, 73, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csoma, J. Hydrology of the Rába River. [A Rába hidrográfiája]. Vízrajzi Atlasz, 1972; 14, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, H.; Kollmann, W.; Vasvári, V.; Ambrózy, P.; Domokos, M.; Goda, L.; Laczay, I.; Neppel, F.; Szilágyi, E. Hydrologische Monographie des Einzugsgebietes der Oberen Raab. Series on Water Management, Technischen Universität Graz, Graz, Austria, 1996; p. 257.

- Károlyi, Z. Hydrography of the Little Plain [A Kisalföld vizeinek földrajza]. Földrajzi Közlemények 1962 10, 157-174.

- Laczay, I. Catchment and hydrology of the Rába. Regulation and meanders of the Rába. [A Rába vízgyűjtője és vízrendszere. A Rába szabályozása és kanyarulati viszonyai] Vízrajzi Atlasz 1972, 14, 4–7, 24-30.

- Crowder, D.W.; Knapp, H.V. Effective discharge recurrence intervals of Illinois streams. Geomorphology, 2005; 64, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabolotnia, T.; Parajka, J.; Gorbachova, L.; Széles, B.; Blöschl, G.; Aksiuk, O.; Tong, R.; Komma, J. Fluctuations of Winter Floods in Small Austrian and Ukrainian Catchments. Hydrology 2022, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabih, S.; Tzoraki, O.; Zanis, P.; Tsikerdekis, T.; Akritidis, D.; Kontogeorgos, I.; Benaabidate, L. Alteration of the Ecohydrological Status of the Intermittent Flow Rivers and Ephemeral Streams due to the Climate Change Impact (Case Study: Tsiknias River). Hydrology 2021, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerst, M.; Rüther, N. Bank Retreat and Streambank Morphology of a Meandering River during Summer and Single Flood Events in Northern Norway. Hydrology 2018, 5, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkiatas, G.T.; Koutalakis, P.D.; Kasapidis, I.K.; Iakovoglou, V.; Zaimes, G.N. Monitoring and Quantifying the Fluvio-Geomorphological Changes in a Torrent Channel Using Images from Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Hydrology 2022, 9, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, B.; Rinaldi, M. Changes in meander geometry over the last 250 years along the lower Guadalquivir River (southern Spain) in response to hydrological and human factors. Geomorphology 2022, 410, 108284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertalan, L.; Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Surian, N.; Sulc Michalková, M.; Kovács, Z.; Szabó, Sz.; Szabó, G.; Hooke, J. Detailed assessment of spatial and temporal variations in river channel changes and meander evolution as a preliminary work for effective floodplain management. The example of Sajó River, Hungary. J. Envi. Manag, 2019; 248, 109277. [Google Scholar]

| Survey period | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 |

| Apr. –Aug. 2022 | Aug. – Dec. 2022 | Dec. 2022 – Apr. 2023 | Apr. – Aug. 2023 | Aug. – Dec. 2023. | Dec. 2023. –Apr. 2024 | |

| mean bank erosion | 0.5±0.2 | 0.3±0.1 | 0.7±0.2 | 2.8±1.6 | 1.0±0.6 | 0.4±0.4 |

| greatest mean bank erosion (ID of meander) | 0.9 (G) | 0.5 (H) | 1.1 (G) | 6.9 (C) | 3.4 (H) | 1.9 (6) |

| maximum local bank erosion | 1.6 (G) | 0.8 (G) | 2.2 (G) | 19.8 (A) | 4.6 (H) | 4.0 (H) |

| number of bends with bank erosion higher than 0.8 m | 2 | 0 | 5 | 20 | 14 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).