Submitted:

14 June 2024

Posted:

14 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

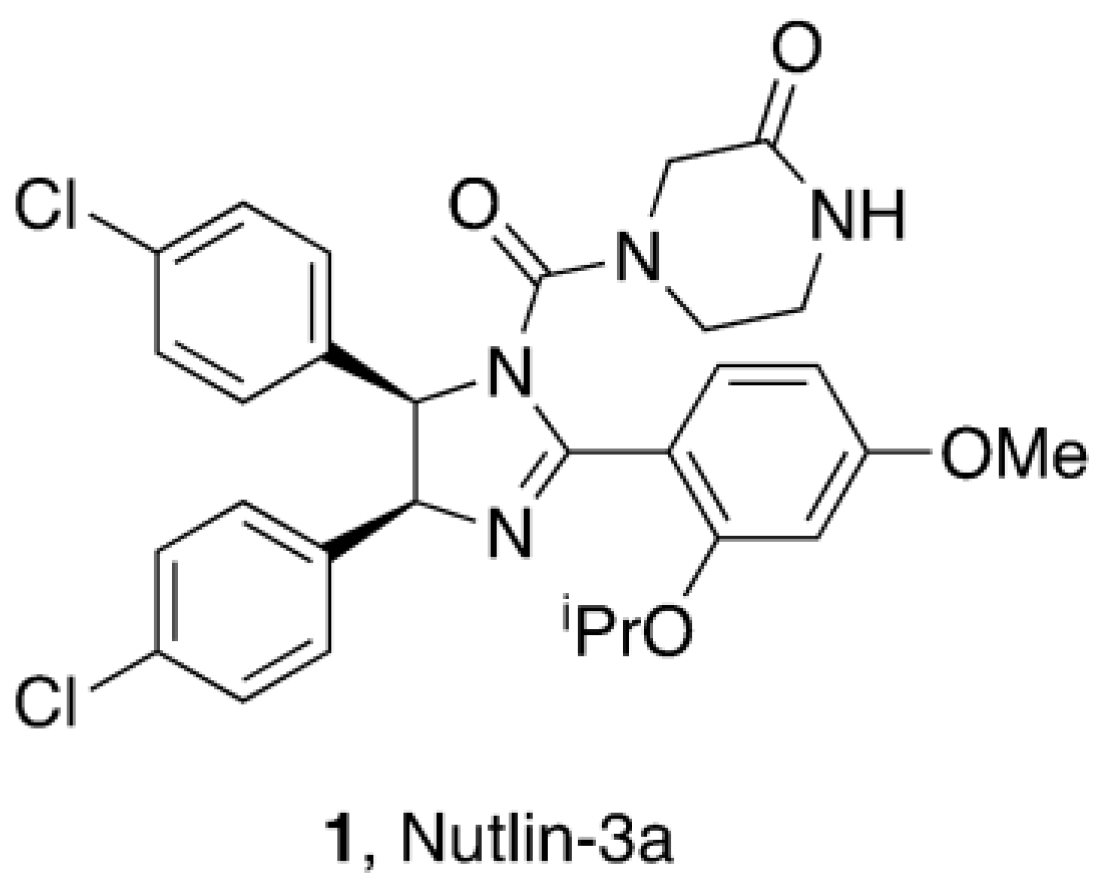

1. Introduction

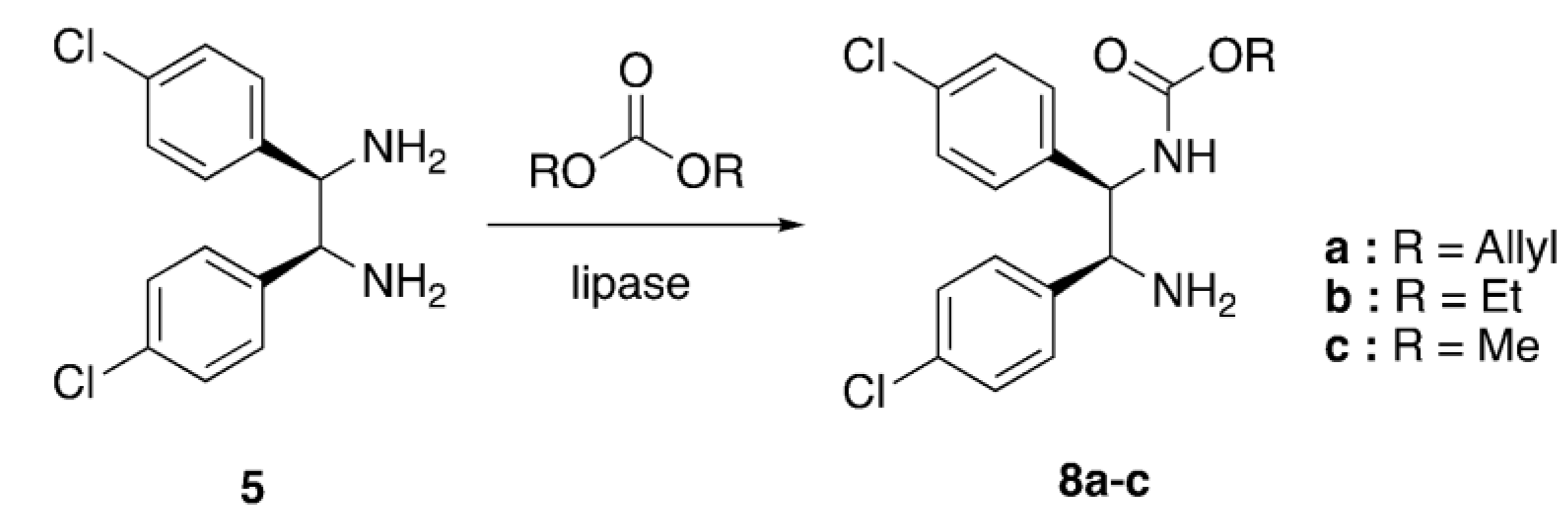

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Enzyme Screening

| Entry | lipase | yield (%)a | Ee (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| entry 1 | CAL-B | 27a | 76 |

| entry 2 | RML | 16a | 69 |

| entry 3 | Liver acetone powder porcine | 6a | 9 |

| entry 4 | Pseudomonas cepacia (PSL-C) | 2b | n.d |

| entry 5 | Candida rugosa | 4b | n.d |

| entry 6 | Pseudomonas fluorescens | 8b | n.d |

| entry 7 | Aspergillus niger | / | / |

| entry 8 | Penicillum roqueforti | / | / |

2.2. Effect of Solvent

| Entry | solvent | yield (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| entry 1 | Toluene | traces |

| entry 2 | 1,4-dioxane | traces |

| entry 3 | tert-amyl alcoholb | 23% |

| entry 4 | ACN | - |

2.3. Effect of Temperature

2.4. Effect of Reaction Time

2.5. Scaling Up

| Entry | Diamine mg |

diamine/DAC mg/mL |

Enzyme loadinga | T (°C) |

Time (days) |

Yield (%)b Ee (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry 1 | 60 | 30 | 0.3:1 | 45 | 6 | 27 76 |

| entry 2 | 200 | 50 | 0.5:1 | 45 | 6 | 14 83 |

| entry 3 | 60 | 30 | 0.3:1 | 75 | 3 | 65 80 |

| entry 4 | 500 | 70 | 0.5:1 | 75 | 3 | 65 89 |

| Entry | Diamine mg |

diamine/DEC mg/mL |

Enzyme loadinga | T (°C) | Time (days) | Yield (%)b Ee (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry 1 | 60 | 30 | 0.3:1 | 45 | 6 | trace n.d. |

| entry 2 | 60 | 30 | 0.3:1 | 75 | 3 | 16 72 |

| entry 3 | 200 | 67 | 0.5:1 | 75 | 4 | 22 78 |

| entry 4 | 500 | 50 | 0.5:1 | 75 | 3 | 30 53 |

| Entry | Diamine mg |

Diamine/DMC mg/mL |

Enzyme loadinga | T (°C) | Time (days) | Yield (%)b Ee (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry 1 | 60 | 30 | 0.3:1 | 45 | 6 | trace n.d. |

| entry 2 | 60 | 30 | 0.3:1 | 75 | 5 | 95 73 |

| entry 3 | 500 | 70 | 0.3:1 | 75 | 7 | 22 31 |

| entry 4 | 200 | 40 | 0.3:1 | 75 | 7 | 36 46 |

| entry 5 | 500 | 100 | 0.4:1 | 75 | 4 | 30 44 |

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Enzymatic Reaction

3.2. General Racemic Reaction

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Brown, C.J.; Lain, S.; Verma, C.S.; Fersht, A.R.; Lane, D.P. Awakening Guardian Angels: Drugging the P53 Pathway. Nat Rev Cancer 2009, 9, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, C.P.; Brown-Swigart, L.; Evan, G.I. Modeling the Therapeutic Efficacy of P53 Restoration in Tumors. Cell 2006, 127, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A.; Kirsch, D.G.; McLaughlin, M.E.; Tuveson, D.A.; Grimm, J.; Lintault, L.; Newman, J.; Reczek, E.E.; Weissleder, R.; Jacks, T. Restoration of P53 Function Leads to Tumour Regression in Vivo. Nature 2007, 445, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Zender, L.; Miething, C.; Dickins, R.A.; Hernando, E.; Krizhanovsky, V.; Cordon-Cardo, C.; Lowe, S.W. Senescence and Tumour Clearance Is Triggered by P53 Restoration in Murine Liver Carcinomas. Nature 2007, 445, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shangary, S.; Qin, D.; McEachern, D.; Liu, M.; Miller, R.S.; Qiu, S.; Nikolovska-Coleska, Z.; Ding, K.; Wang, G.; Chen, J.; et al. Temporal Activation of P53 by a Specific MDM2 Inhibitor Is Selectively Toxic to Tumors and Leads to Complete Tumor Growth Inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 3933–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Chen, F.-E. Small-Molecule MDM2 Inhibitors in Clinical Trials for Cancer Therapy. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 236, 114334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Matsubara, H. Recent Advances in P53 Research and Cancer Treatment. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology 2011, 2011, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Thuraisamy, A. MDM2/P53 Inhibitors as Sensitizing Agents for Cancer Chemotherapy. In Protein Kinase Inhibitors as Sensitizing Agents for Chemotherapy; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 243–266 ISBN 978-0-12-816435-8.

- Vassilev, L.T.; Vu, B.T.; Graves, B.; Carvajal, D.; Podlaski, F.; Filipovic, Z.; Kong, N.; Kammlott, U.; Lukacs, C.; Klein, C.; et al. In Vivo Activation of the P53 Pathway by Small-Molecule Antagonists of MDM2. Science 2004, 303, 844–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, B.; Wovkulich, P.; Pizzolato, G.; Lovey, A.; Ding, Q.; Jiang, N.; Liu, J.-J.; Zhao, C.; Glenn, K.; Wen, Y.; et al. Discovery of RG7112: A Small-Molecule MDM2 Inhibitor in Clinical Development. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 466–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.-J.; Jiang, N.; Zhang, J.; Ross, T.M.; Chu, X.-J.; Bartkovitz, D.; Podlaski, F.; Janson, C.; et al. Discovery of RG7388, a Potent and Selective P53–MDM2 Inhibitor in Clinical Development. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 5979–5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll-Mulet, L.; Iglesias-Serret, D.; Santidrián, A.F.; Cosialls, A.M.; De Frias, M.; Castaño, E.; Campàs, C.; Barragán, M.; De Sevilla, A.F.; Domingo, A.; et al. MDM2 Antagonists Activate P53 and Synergize with Genotoxic Drugs in B-Cell Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Cells. Blood 2006, 107, 4109–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohnstad, H.O.; Paulsen, E.B.; Noordhuis, P.; Berg, M.; Lothe, R.A.; Vassilev, L.T.; Myklebost, O. MDM2 Antagonist Nutlin-3a Potentiates Antitumour Activity of Cytotoxic Drugs in Sarcoma Cell Lines. BMC Cancer 2011, 11, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deben, C.; Wouters, A.; De Beeck, K.O.; Van Den Bossche, J.; Jacobs, J.; Zwaenepoel, K.; Peeters, M.; Van Meerbeeck, J.; Lardon, F.; Rolfo, C.; et al. The MDM2-Inhibitor Nutlin-3 Synergizes with Cisplatin to Induce P53 Dependent Tumor Cell Apoptosis in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 22666–22679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Rousseau, R.F.; Middleton, S.A.; Nichols, G.L.; Newell, D.R.; Lunec, J.; Tweddle, D.A. Pre-Clinical Evaluation of the MDM2-P53 Antagonist RG7388 Alone and in Combination with Chemotherapy in Neuroblastoma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 10207–10221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Player, M.R. Small-Molecule Inhibitors of the P53-HDM2 Interaction for the Treatment of Cancer. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 2008, 17, 1865–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElSawy, K.; Verma, C.S.; Lane, D.P.; Caves, L. On the Origin of the Stereoselective Affinity of Nutlin-3 Geometrical Isomers for the MDM2 Protein. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 3727–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotouhi, N.; Liu, E.A.; Vu, B.T. Cis-Imidazolines as Mdm2 Inhibitors Intl. Pat. Appl. WO2005002575A1 2005.

- Bartkovitz, D.J.; Cai, J.; Chu, X.-J.; Li, H.; Lovey, A.J.; Vu, B.T.; Zhao, C. Chiral Cis-Imidazolines Intl. Pat. Appl. WO 2009/047161 2009.

- Davis, T.A.; Johnston, J.N. Catalytic, Enantioselective Synthesis of Stilbene Cis-Diamines: A Concise Preparation of (−)-Nutlin-3, a Potent P53/MDM2 Inhibitor. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.A.; Vilgelm, A.E.; Richmond, A.; Johnston, J.N. Preparation of (−)-Nutlin-3 Using Enantioselective Organocatalysis at Decagram Scale. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 10605–10616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantinati, A.; Bianco, S.; Cristofori, V.; Cavazzini, A.; Catani, M.; Zanirato, V.; Pacifico, S.; Rimondi, E.; Milani, D.; Voltan, R.; et al. Expeditious Synthesis and Biological Characterization of Enantio-Enriched (-)-Nutlin-3. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 8504–8508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, C.K.; Seidel, D. Catalytic Enantioselective Desymmetrization of Meso -Diamines: A Dual Small-Molecule Catalysis Approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14538–14541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, K. Biotransformations in Organic Chemistry: A Textbook; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; ISBN 978-3-642-17393-6. [Google Scholar]

- Patti, A.; Sanfilippo, C. Breaking Molecular Symmetry through Biocatalytic Reactions to Gain Access to Valuable Chiral Synthons. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Urdiales, E.; Alfonso, I.; Gotor, V. Update 1 of: Enantioselective Enzymatic Desymmetrizations in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, PR110–PR180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busto, E.; Gotor-Fernández, V.; Montejo-Bernardo, J.; García-Granda, S.; Gotor, V. First Desymmetrization of 1,3-Propanediamine Derivatives in Organic Solvent. Development of a New Route for the Preparation of Optically Active Amines. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 4203–4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Lombardía, N.; Busto, E.; García-Urdiales, E.; Gotor-Fernández, V.; Gotor, V. Enzymatic Desymmetrization of Prochiral 2-Substituted-1,3-Diamines: Preparation of Valuable Nitrogenated Compounds. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 2571–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rìos-Lombardìa, N.; Busto, E.; Gotor-Fernández, V.; Gotor, V. Synthesis of Optically Active Heterocyclic Compounds by Preparation of 1,3-Dinitro Derivatives and Enzymatic Enantioselective Desymmetrization of Prochiral Diamines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 2010, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Lombardía, N.; Busto, E.; Gotor-Fernández, V.; Gotor, V. Chemoenzymatic Asymmetric Synthesis of Optically Active Pentane-1,5-Diamine Fragments by Means of Lipase-Catalyzed Desymmetrization Transformations. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 5709–5718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkessel, A.; Ong, M.-C.; Nachi, M.; Neudörfl, J.-M. Enantiopure Monoprotected Cis-1,2-Diaminocyclohexane: One-Step Preparation and Application in Asymmetric Organocatalysis. ChemCatChem 2010, 2, 1215–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Sánchez, D.; Ríos-Lombardía, N.; García-Granda, S.; Montejo-Bernardo, J.; Fernández-González, A.; Gotor, V.; Gotor-Fernández, V. Lipase-Catalyzed Desymmetrization of Meso-1,2-Diaryl-1,2-Diaminoethanes. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2014, 25, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangary, S.; Wang, S. Small-Molecule Inhibitors of the MDM2-P53 Protein-Protein Interaction to Reactivate P53 Function: A Novel Approach for Cancer Therapy. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2009, 49, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiguchi, S.; Fujii, A.; Takehara, J.; Ikariya, T.; Noyori, R. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Aromatic Ketones Catalyzed by Chiral Ruthenium(II) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 7562–7563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhonsky, V.V.; Pashenko, A.A.; Becker, J.; Hausmann, H.; De Groot, H.J.M.; Overkleeft, H.S.; Fokin, A.A.; Schreiner, P.R. Synthesis and Antiproliferative Activity of Hindered, Chiral 1,2-Diaminodiamantane Platinum( ii ) Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 14009–14016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirel, C.; Pécaut, J.; Choua, S.; Turek, P.; Amabilino, D.B.; Veciana, J.; Rey, P. Enantiopure and Racemic Chiral Nitronyl Nitroxide Free Radicals: Synthesis and Characterization. Eur J Org Chem 2005, 2005, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).