1. Introduction

Severe asthma (SA) affects approximately 10% of individuals with asthma [

1] and is characterized by persistent symptoms and frequent exacerbations despite adherence to maximum doses of treatment according to step 5 GINA guidelines [

2,

3]. Over the last 20 years, the availability of IgG for therapeutic use in severe asthma has changed the lives of many people, giving clinicians and patients the possibility to achieve good disease control with limited side effects and paving the way for new composite clinical outcomes, such as clinical remission.

According to the ISAR Registry, the majority of patients with severe asthma diagnosis, nearly 80% of these patients, are classified as having an eosinophilic phenotype [

4]. Severe eosinophilic asthma (SEA) refers to a subgroup of severe asthma patients characterized by high levels of blood and/or sputum eosinophils [

5]; thus, the management of patients affected by SEA often involves targeted therapies, such as monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that specifically tackle eosinophils or type 2 mediators involved in the activation and recruitment of these immune cells, to reduce airway inflammation and improve asthma control [

6].

Benralizumab is a mAb targeting IL-5Rα on eosinophils, basophils, mast cells and other cells [

7]. Its effectiveness in SEA is well established, reducing asthma exacerbations and oral corticosteroid (OCS) use and improving lung function, asthma control and quality of life [

8,

9]. Benralizumab induces eosinophil apoptosis through an antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) mechanism mediated by natural killer (NK) cells and macrophages, significantly reducing peripheral eosinophils [

10,

11]. The SIROCCO [

12] and CALIMA [

13] trials demonstrated that benralizumab significantly reduced exacerbation rates and improved lung function in severe uncontrolled asthma with eosinophilic features, while the ZONDA [

14] study established that this anti-IL-5Rα monoclonal antibody reduced oral corticosteroid use and exacerbations. Moreover thelong-term trials – BORA and MELTEMI [

15,

16] reinforced benralizumab safety and efficacy over 2 and 5 years, respectively. Recent clinical advances as well as the availability of new therapeutic options, require the scientific community to have a more comprehensive approach when considering the management of severe asthma. In light of this, biomarkers are taking on an increasingly pivotal role when evaluating the patient’s endo-phenotype, trying to understand the real weight of different cells and/or cytokines in the immune response of the different patients [

16,

17]. This approach accounts for the choice of the biological drug that could better tackle the real driver of inflammation, standing for a personalized clinical evaluation and treatment decision [

19]. On this path toward precision medicine, the pharmacology of the different biological treatments becomes the essential key for choosing the right drug for the right patient [

19].

This review aims to dive deeper into pharmacological and pharmacokinetic aspects of benralizumab in the treatment of severe asthma, which accounts for its clinical efficacy and safety profile, previously described in patients with an eosinophilic phenotype of the disease.

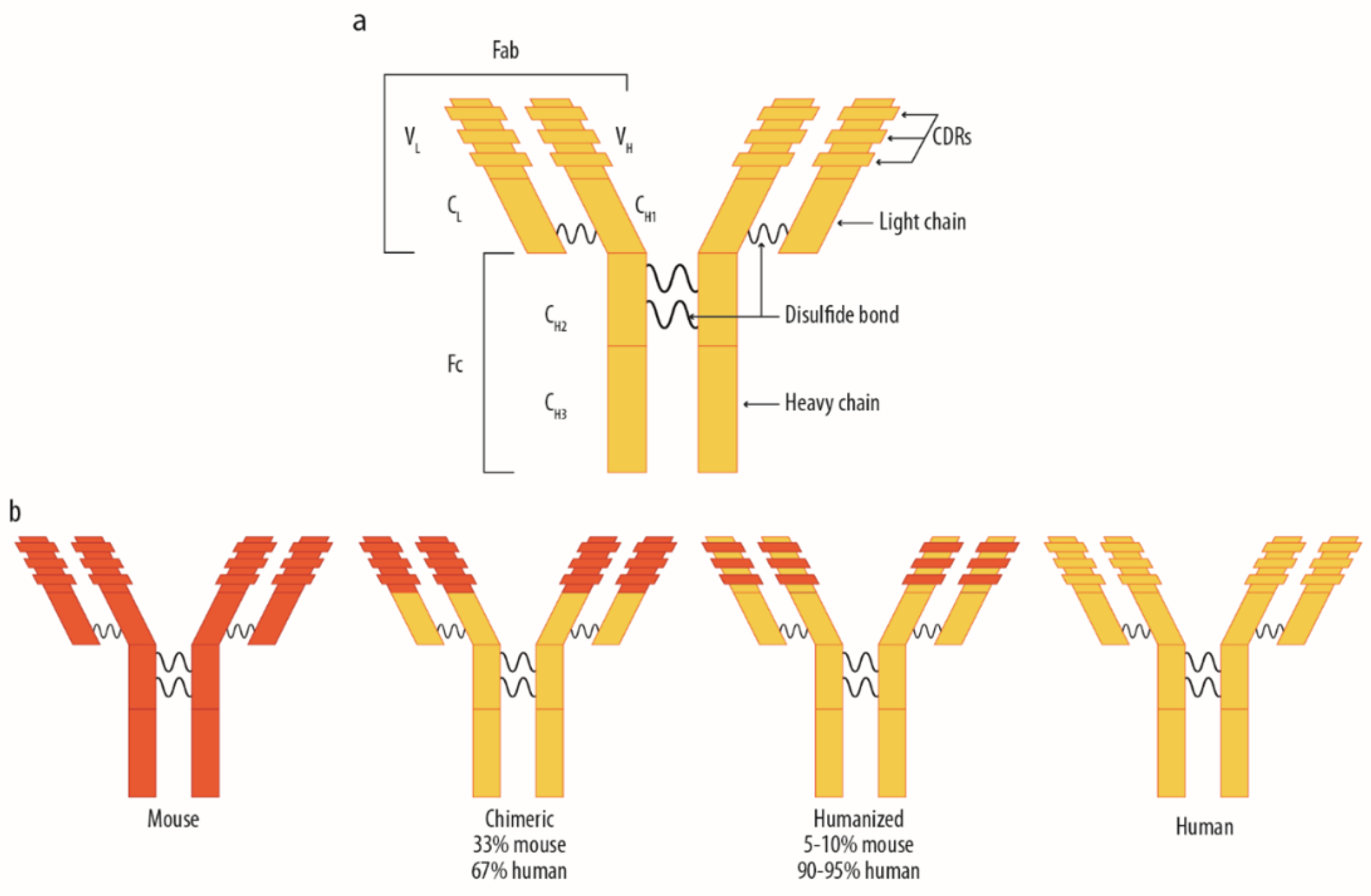

1.1. The Use of Monoclonal Antibodies for Therapeutic Purposes: Distribution Mechanisms and Related Factors

In the treatment of SA, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are currently the most appropriate treatment option [

6]. They target different pathways in airway inflammation; therefore, it is important to thoroughly understand their mechanisms of action. Structurally, they represent monoclonal immunoglobulins belonging to the IgG isotype, produced by a single clone of cells or cell line, consisting of identical antibody molecules able to recognize and bind a single target. They will be following referred to as therapeutic IgGs. Therapeutic IgGs, to date, approved and commercialized for SA, are categorized as humanized or human based on the production process by which they are genetically engineered and, therefore, their final structure (

Figure 1) [

20].

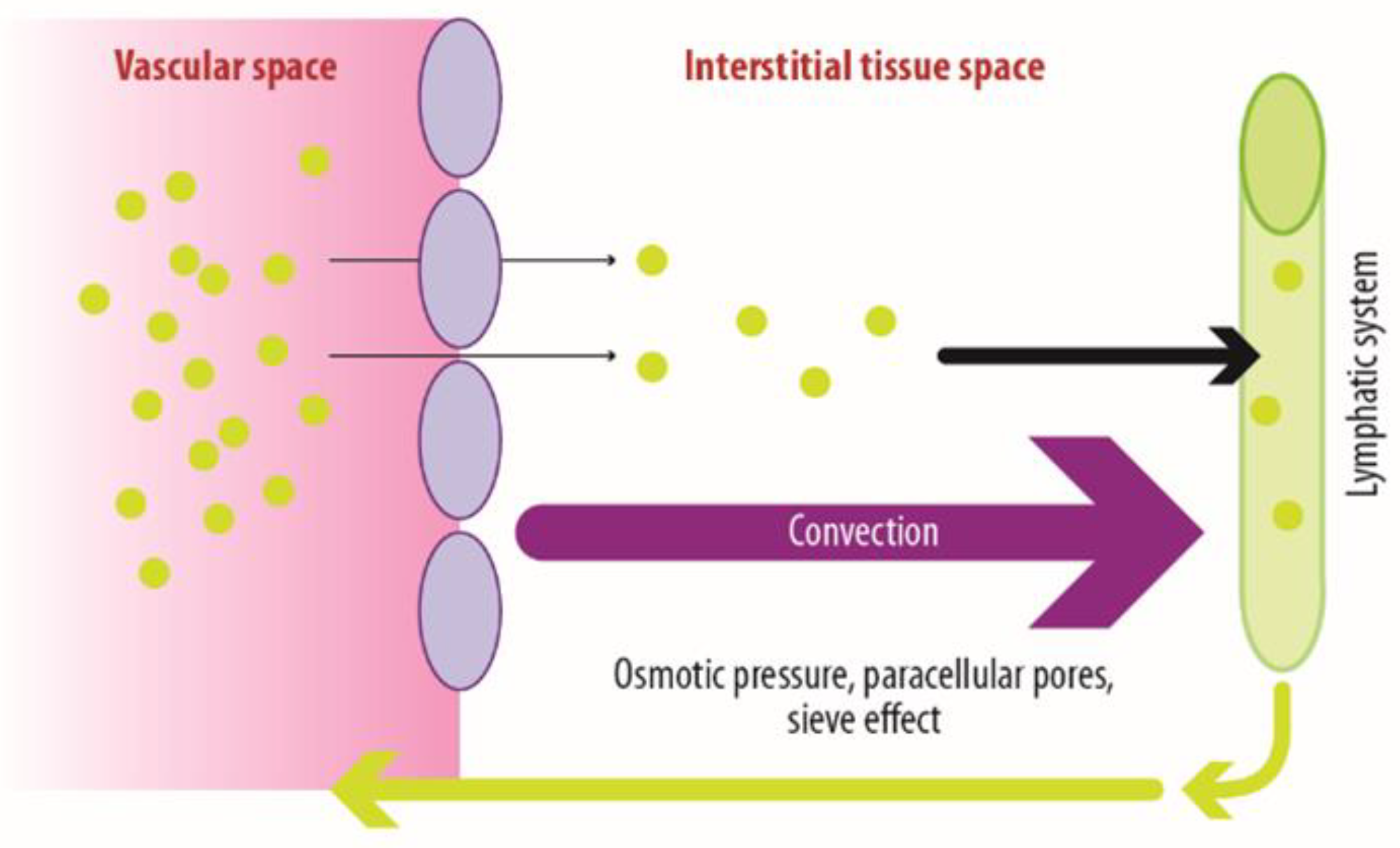

Therapeutic IgGs play a crucial role in modulating immune responses. Thus, they are extensively used for treating a wide range of diseases to reach their target tissues and exert their therapeutic effects; immunoglobulins employ three distinct distribution mechanisms. The first mechanism involves passive diffusion, which is influenced by the size and chemical-physical properties of the molecules. It contributes to IgGs distribution, especially in smaller tissues, but is not the primary mechanism [

21]. The second mechanism, called convection, plays a crucial role; it consists of the transition of fluid from the vascular bed to tissue extracellular space and lymphatic compartment. This process is driven by the blood–tissue hydrostatic gradient, which relies on the pressure difference between blood vessels and surrounding tissues [

21]. The key structures accounting for this process are the endothelial fenestrations (EF), dynamic pores structures located throughout the blood vessel walls that can undergo contraction and relaxation, thus influencing convection. These fenestrations may differ in size across various tissues. For example, in organs, such as the bone marrow, blood vessels have relatively large fenestrations, typically around 100 nm in diameter; as a result, IgGs can easily pass through these fenestrations and enter the surrounding tissue [

22]. However, in smaller blood vessels or those with tighter endothelial junctions, such as those found in the blood-brain barrier, the fenestrations are much smaller or even absent. In these cases, the IgGs crossing through convection is more restricted [

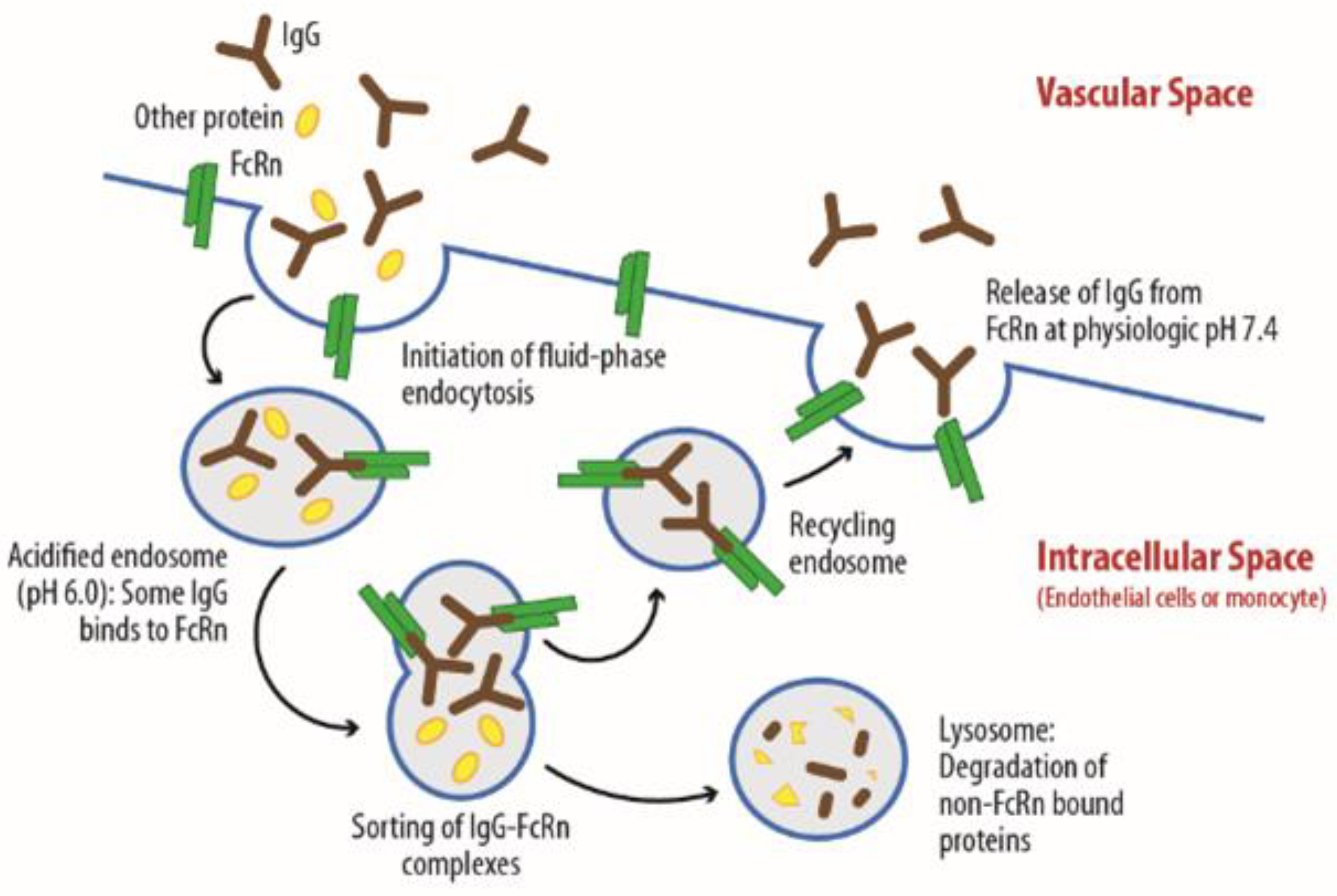

22]. The third mechanism, transcytosis, plays a significant role in IgGs transportation, particularly in small blood vessels characterized by reduced EF (as illustrated in

Figure 2). Transcytosis consists of a stepwise process, starting with the drug binding with FcRn receptors located on the endothelial cells’ surface. This interaction leads to drug-receptor complex internalization and microvesicle formation within the endothelial intracellular space. The stability of the FcRn–IgG bond within these microvesicles is pH-dependent [

23]. Transcytosis carries out multiple functions: it facilitates IgGs recycling, thereby extending their half-life in circulation, which typically ranges from 15 to 25 days. Additionally, transcytosis enables IgGs to transition from the vascular stream directly to the tissue’s extracellular fluids. This mechanism is essential for ensuring IgGs’ effective delivery to target tissues and sites of action, contributing to their therapeutic efficacy in a wide range of disease conditions [

21,

22,

23].

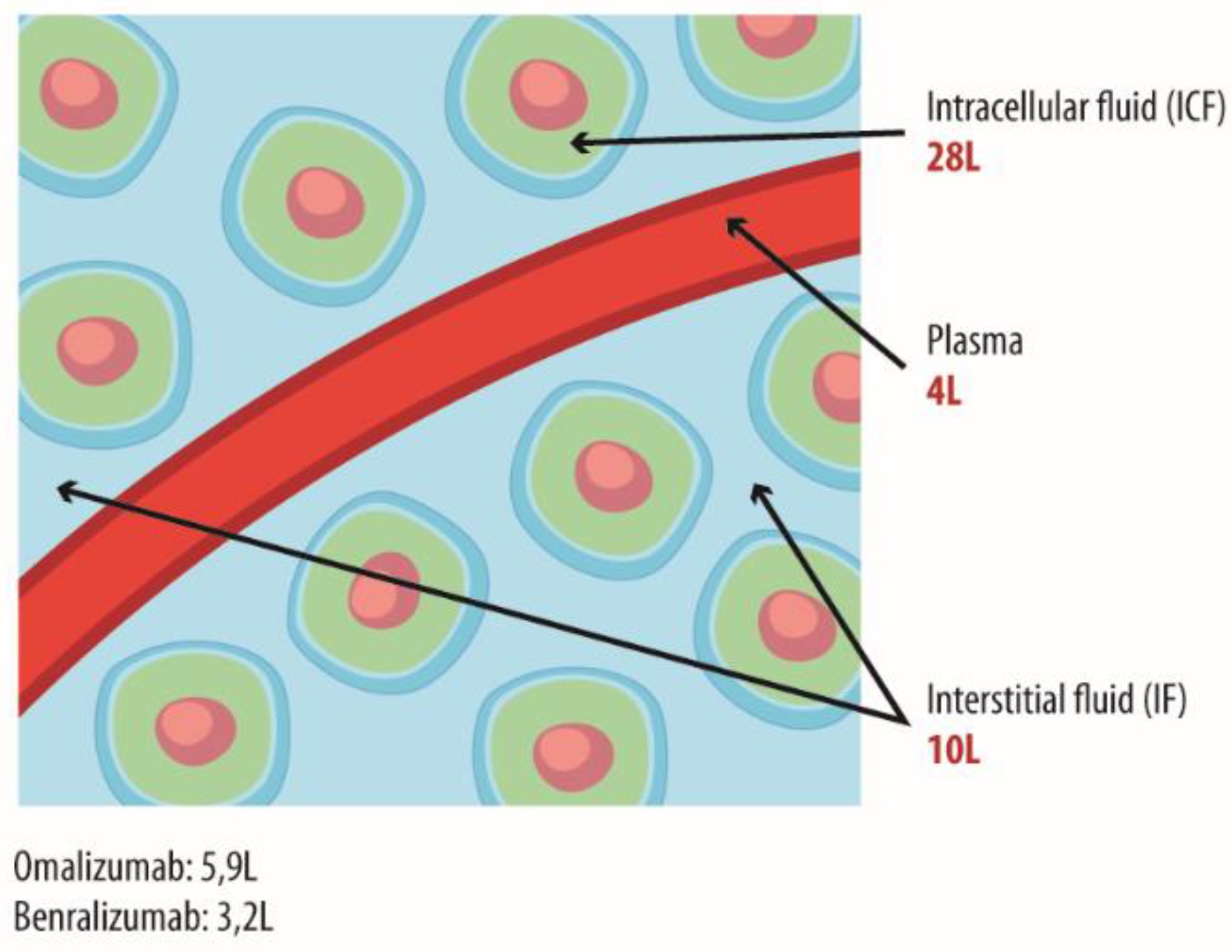

The total amount of IgG keeps a steady equilibrium, across various compartments, including vascular and interstitial spaces. This balance does not impact the volume of distribution (Vd), calculated as the dose (mg) divided by the plasma concentration (mg/l) and thus referred to as “apparent”. Consequently, the Vd remains relatively constant at 5–6 l, suggesting that distribution beyond the plasma compartment cannot be justified solely based on this parameter (

Figure 3) [

21,

22].

Endothelial permeability is another aspect to be considered in Igs distributions; its increase is often associated with inflammation [

24], a hallmark of chronic inflammatory disorders, such as severe asthma and EGPA [

25]. Of note, recent data suggests the vascular endothelium works not only as a physical barrier but also as a functional immunological organ, able to produce cytokines and chemokines and to respond to antigens in a FcER-dependent manner [

24]. Additionally, cytokines, such as IL-4, may trigger an upregulation of Fcε receptors (FcERI and FcERII) on endothelial cells. Overall, these mechanisms might potentially worsen Th2-driven inflammatory responses, leading to compromised endothelial integrity and increased permeability [

24].

1.2. Mechanism of Action of Therapeutic IgGs for Severe Asthma

The IgGs currently studied, approved, and commercialized for treating SA have distinct mechanisms of action, targeting different molecular pathways.

Omalizumab, the first approved for allergic asthma, acts by blocking both free and bound IgE, reducing the presence of FcεRI receptors on basophils and dendritic cells, and competing with basophil receptors to deactivate IgE bound to them [

26]. Dupilumab targets the type 1 IL-4 receptor and the type 2 IL-4/IL-13 receptor, thereby inhibiting signaling triggered by IL-4 and IL-13, which are key players in orchestrating allergic and inflammatory type 2 responses [

27]. Mepolizumab binds serum IL-5, a fundamental cytokine for the development, activation, and survival of eosinophils, preventing its interaction with the IL-5α receptor [

28]. Tezepelumab targets thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), an alarmin produced by bronchial epithelium in response to a wide range of triggers [

29,

30]. This pivotal epithelial alarmin can also be produced by other immune cells, such as dendritic cells, fibroblasts, basophils and mast cells, in the presence of IgE, IL-4, IL-13 and TNF-α [

31]. Once released, TSLP is able to interact with this receptor expressed on different cells, not only the above-mentioned, but also lymphocytes, eosinophils, nerves, smooth muscle cells and platelets, modulating the allergic and inflammatory process T2 and Th1 up-stream/Th17 [

30]. It modulates the type 2 allergic and inflammatory processes by interacting with receptors located on lymphocytes, eosinophils, nerves, smooth muscle cells, and platelets [

32].

1.3. Benralizumab in Severe Asthma: Mechanism of Action and Kinetics

1.3.1. Mechanism of Action

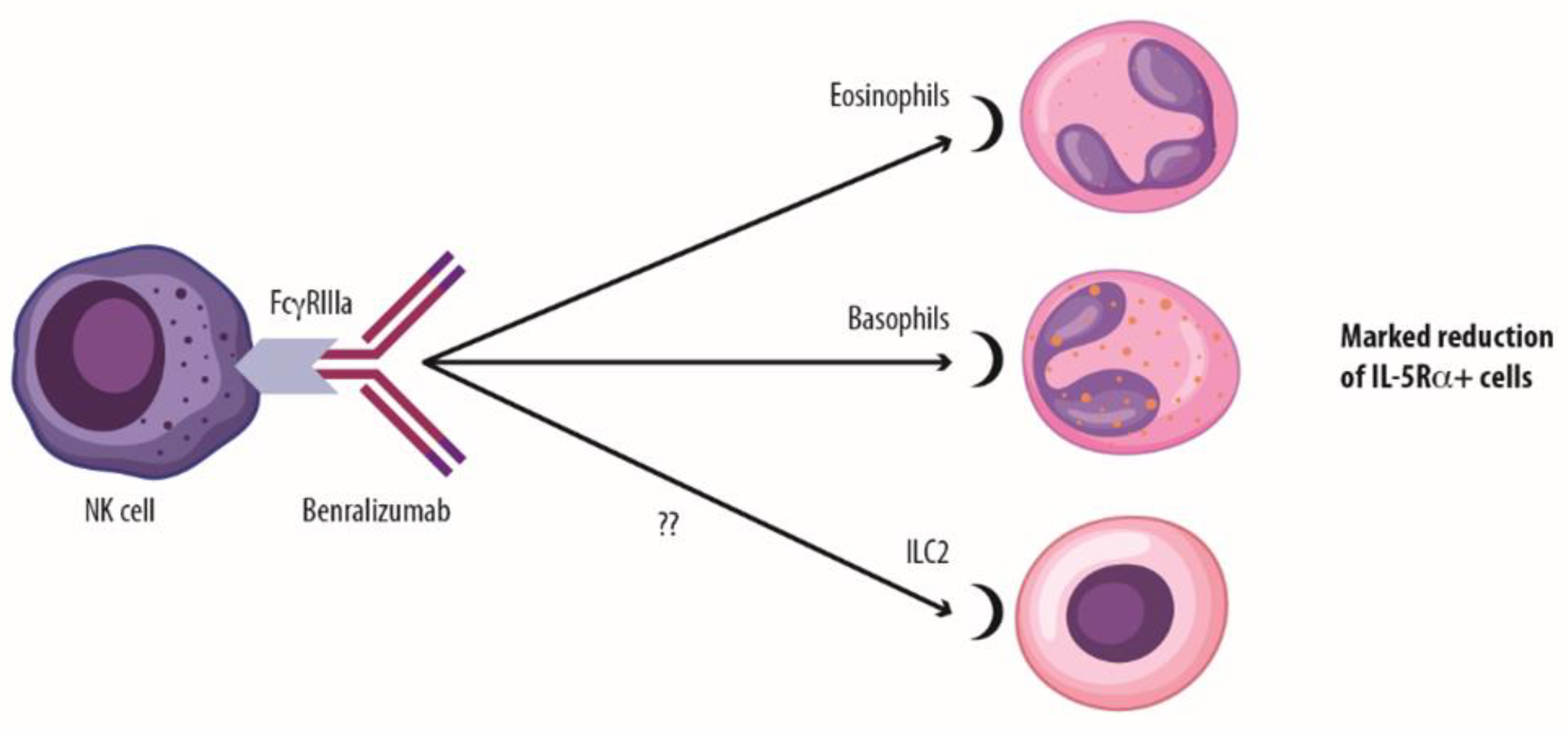

Benralizumab is a direct anti-eosinophilic mAb binding the chain of IL-5 receptors, capable of markedly reducing these cells by inducing antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) by natural killer (NK) cells [

10]. Benralizumab shows a low dissociation constant (Kd) value of 11 pM. Of note, the smaller the Kd, the more tightly bound the ligand is, so we can state a very high affinity between benralizumab and the IL-5Rα. The benralizumab afucosylated portion significantly enhances its binding affinity to the FcγRIII receptor on NK cells, making it around 1,000-times more effective than non-afucosylated immunoglobulins. This increased affinity induces cell killing via ADCC and enhances annexin V expression, a marker of apoptosis [

33]. The expression of the IL-5Rα receptor is not limited to eosinophils but also extends to other innate and adaptive immune system cells, including CD45+ eosinophil precursors, basophils, and potentially also innate lymphoid cells-2 (ILC-2) [

34]). Recent studies have, in fact, demonstrated significant reductions in IL-5+ ILC2 levels in both peripheral blood and sputum, as well as a decrease in CD125 (IL-5R)+ILC2 levels in peripheral blood following treatment with benralizumab [

34]. Of note, benralizumab targeting the IL-5α receptor also prevents the IL-5/IL-5R interaction, thus interfering with the functions of these cytokines on its target cells [

7].

Additionally, benralizumab can induce eosinophil death also through macrophage activation, and specifically, involving either the direct uptake of eosinophils by macrophage phagocytosis/efferocytosis (antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis, ADCP) or the release of TNF-that has a direct cytotoxic effect on eosinophils, leading to eosinophil apoptosis linking to the TNFR1 expressed on eosinophil surface [

11].

This complex and unique mechanism of action and pharmacodynamics leads to a profound reduction in eosinophils in both peripheral blood and bronchial tissue [

34]. These findings corroborate data from Nair et al. [

35], that confirms benralizumab efficacy in reducing tissue eosinophilia, also in those patients with more than 20% eosinophils in sputum (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) [

34].

he science of eosinophils has been changing in the last years; eosinophils’ heterogeneity is emerging, and the presence of homeostatic tissue-resident eosinophils (rEos) in the lung parenchyma has been described [

36]. Under inflammatory conditions, an additional cell subphenotype is present, called inflammatory eosinophil (iEos) [

37]. In humans, the percentage of eosinophils showing an inflammatory phenotype directly correlated with asthma severity and the treatment with anti-IL-5 reduced the percentage of circulating iEos to a similar extent as observed in healthy individuals [

38]. Furthermore, it has been observed that in SEA patients with nasal polyps, the proportion of iEos increases when moving from the blood into the nasal polyp tissue [

37]. More recently, a study analyzed the effect of mepolizumab on eosinophils in sputum in a pediatric population with severe asthma, demonstrating that exacerbating patients had a statistically higher percentage of iEos compared to those without exacerbations, despite treatment with mepolizumab [

39]. The analysis of circulating iEos is not feasible with benralizumab since eosinophil count in peripheral blood is virtually zero in patients undergoing treatment. However, the evaluation of the impact of anti-eosinophilic strategies on tissue iEos would represent a very interesting field of research in the future.

1.3.2. Kinetics of Benralizumab

Benralizumab is approved for the treatment of SA with a dose regimen of 30 mg for three administrations every 4 weeks (loading phase), followed by subsequent administrations of 30 mg every 8 weeks (maintenance phase) [

40]. This loading dosage facilitates rapid tissue penetration, which, together with the fast mechanism of ADCC, results in a significant and quick reduction of eosinophilia. Steady-state concentration is an important pharmacokinetic parameter describing a dynamic equilibrium in which drug concentrations consistently stay within therapeutic limits for a long, potentially indefinite time. By the third to fourth administration, benralizumab achieves an initial steady state, with a mean circulating concentration of approximately 2 µg/ml. Subsequently, after an added 4–5 half-lives, between the fifth and sixth drug administration, the drug reaches the second and definitive steady-state, with a mean concentration of approximately 1 µg/ml, overcoming the 90% effective concentrations (EC90%) threshold, representing 90% of the maximal pharmacological effect. Simulated data show a corresponding 60% reduction in exacerbations and clinical remission achievement at one year at this concentration level [

41]. Notably, the SIROCCO study confirms a consistent efficacy plateau for annualized exacerbation rate reduction with the 30 mg dosage administered once every 8 weeks (Q8W) [

41]. Analysis of real-world evidence studies confirms the effectiveness of benralizumab, reinforcing its prolonged beneficial effects, with the potential for even greater exacerbation reduction over time, as evidenced by the ORBE [

42,

43] and ANANKE study [

44]. These pharmacokinetic-related findings also emphasize the importance of assessing benralizumab efficacy beyond a 6-month treatment period.

It is interesting to speculate about the presence of “soluble” proteins, such as alpha receptors for IL-5 [

45,

46], and whether they may be able to reduce the availability of benralizumab, negatively impacting its efficacy; therefore, it can be hypothesized that the potential interaction between benralizumab and soluble IL-5R may not activate ADCC since it does not involve cell interaction, resulting in weak activity (decoy receptor). However, available data on the massive eosinophils depletion described above, suggests that the interaction with soluble IL-5R is irrelevant both pharmacokinetically and clinically.

Another potential factor that might alter benralizumab kinetics is the development of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs), with particular attention to neutralizing and persistent ones, as happens for other mAbs [

47,

48]. In fact, such therapeutics run the risk of being recognized as foreign by a host immune system, leading to ADA development. Taking into account that the dosage is one of the drug-related factors influencing the immunogenicity [

48], a reduction in drug dosing after the first three administrations of benralizumab, according to its therapeutic schedule, is a condition that might increase the risk for ADA development [

47]. Data from the MELTEMI study, which extends benralizumab safety observation up to 5 years, indicate that in the 8-week arm, the percentage of neutralizing and persistent ADAs is 5–6%, confirming a low clinical impact [

16].

1.4. A Potential third Mechanism of Action of Benralizumab?

Recently, Dagher et al. showed that the benralizumab interaction with isolated eosinophils from healthy individuals in the presence of NK cells triggers NK cell activation, marked by an increase in CD137+ clusters, and boosts the release of Granzyme B and IFN-γ. Hence, this suggests a third mechanism of action of benralizumab [

11]. In support of this last evidence, another study examined patients with SEA treated with benralizumab for 6 months; the results have shown a reduction in the proportion of immature NK cells and an increase in mature, activated NK cells able to induce eosinophil apoptosis, together with higher levels of IFN-γ production and expression of CD137 on the surface of NK cells [

49]. These findings echo those of Dagher et al. in healthy subjects, suggesting that benralizumab may induce a shift in NK cell phenotype from immature to activated and cytotoxic. Notably, most treated patients were not on oral corticosteroid maintenance therapy [

49], data not shown). Additionally, the increased activation of NK cells was associated with improved lung function (FEV1) and reduced use of oral corticosteroids during the 6 months of treatment [

50]. Further research is needed to determine the impact of the modulation regarding the direct effect of benralizumab administration or the reduction of OCS dose or, eventually, the contribution of both factors. The efficacy of benralizumab in reducing exacerbations, improving lung function, and reducing the need for OCS in patients with SEA has been profoundly demonstrated. Real-world evidence further supports this treatment effect, demonstrating that over 90% of patients are able to achieve long-term OCS sparing while maintaining optimal asthma control in eosinophilic-driven SA patients [

50]. The reduction in OCS use due to benralizumab treatment in patients with SEA could have beneficial effects on NK cell function because OCS therapy is known to alter the abundance and phenotype of NK cells, potentially compromising their activity [

51,

52]. Considering that NK cells are involved in immunosurveillance against viruses and that viral infections in SA patients further diminish the cytokine-releasing capacity and apoptotic ability of NK cells [

51], the benralizumab-induced functional recovery of NK cells [

11,

49] may positively implicate enhanced immune protection against viruses, mitigating the risk of viral infections and of asthma exacerbations [

53,

55].

1.5. Looking over the Fence: New Insights on Benralizumab Activity

Few data is available concerning the impact on adaptive immunity during biologic treatment in patients with SA. Still, standing the complexity of SA pathogenesis which involves virtually all immunological cell subsets, it is expectable that biologics could somehow induce substantial modifications on adaptive cells expression and activity. A recent paper by Bergantini et al. explored blood T cell subsets in a small population of SA patients at baseline and throughout two years of treatment with mepolizumab or benralizumab, aiming to detect drug-specific modifications of T cell subsets (including effector and regulatory cells) and exploring their potential correlation with clinical features [

50]. Interestingly, anti-IL5 treatment was associated to a substantial rebalancing of T cell subsets, leading to a normalization of T-reg expression and activity similar ot non-asthmatic subjects: mepolizumab and benralizumab showed quite similar effects on this regard, even though some differences were reported concerning the timing of induction; on the other hand, significant differences were reported on immune-checkpoint (IC) expression on CD4 and CD8 cells. The clinical significance of this finding is still unclear: however, the Authors also observed a significant correlation between PD-1 expression on T-reg cells and the modifications of clinical scores (such as ACT), suggesting how the broad immunological effects of benralizumab may significantly influence also the therapeutic response in clinical terms.

Another unexplored research area regards the potential impact of biologic drugs on cell metabolism and molecular patterns of protein expression: a paper by Vantaggiato et al. applied a proteomic approach to investigate this specific issue in a cohort of patients treated with mepolizumab and benralizumab for a total of six months [

56]. Again, blocking IL-5 pathway led not only to a significant improvement of clinical and respiratory functional outcomes but also to a reliable re-balancing of proteomic features in SA patients, which after 6 months of treatment showed a protein expression profile substantially similar to healthy controls: in particular, it appears that biologic therapy was able to counteract oxidative stress through a empowerment of proteins expression with antioxidative properties, such as ceruloplasmin, transthyretin or apolipoproteins A and C. Intriguingly, the authors depicted also some drug-specific pathways that managed to discriminate a differential effect between mepolizumab and benralizumab: however, the clinical implications of these findings are still to be clarified.

1.6. Benralizumab and Oral Corticosteroids Sparing Effect: As the Mechanism of Action Entails a Clinical Advantage

The efficacy of benralizumab in reducing exacerbations, improving lung function, and reducing the need for OCS in patients with SEA has been profoundly demonstrated. Real-world evidence further supports this treatment effect, demonstrating that over 60% of patients are able to achieve long-term OCS sparing while maintaining optimal asthma control in eosinophilic-driven SA patients [

51].

From a kinetic perspective, corticosteroids, characterized by specific chemical and physical properties, are able to distribute intracellularly within tissues. This process varies depending on their cyclopentanoperhydrophenanthrene derivatives’ characteristics. The distribution of corticosteroids is typically large (Vd ≥30L), resulting in a significantly longer biological half-life compared to its plasma half-life (18–36 hours vs 2–3 hours for prednisone SmPC). Considering this aspect is crucial to optimize adrenal gland function recovery when planning OCS reduction. Corticosteroids exert their pharmacodynamic effects both systemically, within the bloodstream, and locally within tissue [

57]. sThis occurs primarily through genomic immunosuppressive mechanisms involving processes, such as transactivation and transrepression pathways. The potential of IgG therapy, and in particular benralizumab, to reduce or even eliminate the need for corticosteroid use in SEA and other conditions, such as EGPA, has become a pivotal expression of this biologic treatment effectiveness. However, it is worth acknowledging there are differences in patient characteristics and study methodologies across different trials, including the duration of follow-up periods, which can impact the possibility of assessing for a direct comparison. Considering what was previously discussed, it is important to highlight that patients in the benralizumab pivotal ZONDA study seem to have a more severe asthma disease or at least more OCS dependent [

58]. This is evidenced by different clinical characteristics, such as higher maintenance OCS intake (sum of control plus treatment arm) compared to other biologic treatments (SIRUS and VENTURE studies), as well as a higher percentage of comorbid nasal polyps patients (SIRIUS study) [

58].

Benralizumab treatment in patients with SEA, associated with a reduction in OCS use, could have beneficial effects on NK cell function. OCS therapy is known to alter the abundance and phenotype of NK cells, potentially compromising their activity. Moreover, viral infections in SA patients further diminish NK cell activation due to their cytokine-releasing capacity and apoptotic ability [

59]. Benralizumab’s ability to strongly suppress the eosinophilic inflammation thanks to the NK cell function restoring potential independently from the OCS use and OCS sparing effect could offer a comprehensive approach to the treatment of SA and its associated immune dysregulation [

50]. The NK cell reactivation could contribute to improving immune system activity and potentially mitigate the risk of infections and other adverse events associated with OCS use [64–66].

1.7. Concluding and Innovative Remarks

The available data so far clearly show that reducing eosinophils, the main driver of inflammation and tissue damage in SA accounts for clinical benefits to these patients without increasing the risk of adverse events associated with their near-total elimination [

16,

34]. An eosinophil and a non-eosinophil-dependent mechanism of action could be hypothesized, although further investigations are required. Benralizumab is able to directly reduce tissue levels of eosinophils via multiple mechanisms, and additionally, it is potentially able to modulate the innate immune response, leading to its restoration [

11,

49]. The rehabilitation of NK cells may also positively implicate enhanced protection against infections and/or cancer [

61]. All these immunological aspects, as well as its PK, can explain the clinical success of this mAb, as highlighted by several clinical key indicators of efficacy, such as the high proportion of patients achieving clinical remission up to 3 years [

43,

50] –the control of these patients even in cases of failure of previous biologic treatment [

9,

63]; the magnitude of its OCS-sparing effect that can often lead to complete oral steroid elimination in severe eosinophilic patients, while maintaining or even improving disease control [

14,

44]. In other words, the complex and unique multiple modes of actions of benralizuamb and its PK features, seem to be the milestone on which the effectiveness of benralizumab is founded.

Author Contributions

FM, MB, LM, CV, AM, AV, PC: Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing JWS, GS, LB, CC: Writing—review and editing; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This editorial project was supported by AstraZeneca.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance was provided by Raffaella Gatta, PhD, and Aashni Shah (Polistudium SRL, Milan, Italy). This assistance was supported by AstraZeneca.

Conflicts of interest

Alessandra Vultaggio declares fees as speaker/lecturer by AstraZeneca, Chiesi Farmaceutici, GSK, Novartis, Sanofi; Francesco Menzella declares research funding as Principal investigator by AstraZeneca, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Novartis, Sanofi; fees as speaker/lecturer by AstraZeneca, Chiesi Farmaceutici, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Sanofi; Jan Walter Schroeder has nothing to declare; Gianenrico Senna declares fees as speaker/lecturer at congress and advisory boards for AZ, Sanofi, menarini, Novartis, Chiesi, GSK; Paolo Cameli reports having received in the last 3 years research grants and fees as speaker from AstraZeneca-MedImmune, Guidotti-Malesci and GlaxoSmithKline; Marco Benci, Carola Vetriolo and Laura Malerba are AstraZeneca employees; Laura Bergantini is investigator for current research financed by AstraZeneca (grants paid to his institution); Andrea Matucci received fee for advisory board and speaker for GSK, Sanofi, Novartis, Astra Zeneca, CSL Boerhing Chiesi, Takeda; Claudia Crimi reported payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers, bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Astrazeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Menarini, ResMed, Fisher&Paykel.

Abbreviations

| ADCC |

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity |

| ADCP |

Antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis |

| AER |

Annual exacerbation rate |

| CDC |

Complement-dependent cytotoxicity |

| EC 90% |

90% effective concentrations |

| EGPA |

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis |

| IgG |

IgG antibody |

| IL; ILC2; NK |

Interleukin; innate type 2 lymphoid cells; natural killer |

| Q4W/Q8W |

Every 4 weeks/every 8 weeks |

| S.S. |

Steady state |

| Th |

T-helper lymphocyte |

| Vd |

Distribution volume |

References

- Rönnebjerg, L.; Axelsson, M.; Kankaanranta, H.; Backman, H.; Rådinger, M.; Lundbäck, B.; Ekerljung, L. Severe Asthma in a General Population Study: Prevalence and Clinical Characteristics. J Asthma Allergy. 2021, 14, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Difficult-to-treat & Severe Asthma in adolescent and adult patients – Diagnosis and Management. 2023. Available from: https://ginasthma.org/severeasthma).

- Shaw, D.E.; Sousa, A.R.; Fowler, S.J.; Fleming, L.J.; Roberts, G.; Corfield, J.; Pandis, I.; Bansal, A.T.; Bel, E.H.; Auffray, C.; Compton, C.H.; Bisgaard, H.; Bucchioni, E.; Caruso, M.; Chanez, P.; Dahlén, B.; Dahlen, S.E.; Dyson, K.; Frey, U.; Geiser, T.; Gerhardsson de Verdier, M.; Gibeon, D.; Guo, Y.K.; Hashimoto, S.; Hedlin, G.; Jeyasingham, E.; Hekking, P.P.; Higenbottam, T.; Horváth, I.; Knox, A.J.; Krug, N.; Erpenbeck, V.J.; Larsson, L.X.; Lazarinis, N.; Matthews, J.G.; Middelveld, R.; Montuschi, P.; Musial, J.; Myles, D.; Pahus, L.; Sandström, T.; Seibold, W.; Singer, F.; Strandberg, K.; Vestbo, J.; Vissing, N.; von Garnier, C.; Adcock, I.M.; Wagers, S.; Rowe, A.; Howarth, P.; Wagener, A.H.; Djukanovic, R.; Sterk, P.J.; Chung, K.F.; U-BIOPRED Study Group. Clinical and inflammatory characteristics of the European U-BIOPRED adult severe asthma cohort. Eur Respir J. 2015, 46, 1308–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poznanski, S.M.; Mukherjee, M.; Zhao, N.; Huang, C.; Radford, K.; Ashkar, A.A.; Nair, P. Asthma exacerbations on benralizumab are largely non-eosinophilic. Allergy. 2021, 76, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez de Llano, L.; Tran, T.N.; Al-Ahmad, M.; Alacqua, M.; Bulathsinhala, L.; Busby, J.; Canonica, G.W.; Carter, V.; Chaudhry, I.; Christoff, G.C.; Cosio, B.G.; Costello, R.W.; FitzGerald, J.M.; Heaney, L.G.; Heffler, E.; Iwanaga, T.; Jackson, D.J.; Kerkhof, M.; Rhee, C.K.; Menzies-Gow, A.N.; Murray, R.; Papadopoulos, N.G.; Papaioannou, A.L.; Pfeffer, P.E.; Popov, T.A.; Price, C.A.; Sadatsafavi, M.; Tohda, Y.; Wang, E.; Wechsler, M.; Zangrilli, J.G.; Price, D.B. Characterization of eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic severe asthma phenotypes and proportion of patients with these phenotypes in the International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020, 201, A4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhl R, Humbert M, Bjermer L, et al. Severe eosinophilic asthma: a roadmap to consensus. Eur Respir J 2017, 49, 1700634. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Huang, C.; Venegas-Garrido, C.; Zhang, K.; Bhalla, A.; Ju, X.; O’Byrne, P.M.; Svenningsen, S.; Sehmi, R.; Nair, P. Benralizumab Normalizes Sputum Eosinophilia in Severe Asthma Uncontrolled by Anti-IL-5 Antibodies: A Single-Blind, Placebo-controlled Clinical Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023, 208, 1330–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grayson, M.H.; Feldman, S.; Prince, B.T.; Patel, P.J.; Matsui, E.C.; Apter, A.J. Advances in asthma in 2017: Mechanisms, biologics, and genetics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018, 142, 1423–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scioscia, G.; Tondo, P.; Nolasco, S.; Pelaia, C.; Carpagnano, G.E.; Caiaffa, M.F.; Valenti, G.; Maglio, A.; Papia, F.; Triggiani, M.; Crimi, N.; Pelaia, G.; Vatrella, A.; Foschino Barbaro, M.P.; Crimi, C. Benralizumab in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma: a multicentre real-life experience. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Bona, D.; Crimi, C.; D’Uggento, A.M.; Benfante, A.; Caiaffa, M.F.; Calabrese, C.; Campisi, R.; Carpagnano, G.E.; Ciotta, D.; D’Amato, M.; Pelaia, C.; Pelaia, G.; Pellegrino, S.; Scichilone, N.; Scioscia, G.; Ribecco, N.; Spadaro, G.; Valenti, G.; Vatrella, A.; Crimi, N.; Macchia, L. Effectiveness of benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma: Distinct sub-phenotypes of response identified by cluster analysis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2022, 52, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roan, F.; Obata-Ninomiya, K.; Ziegler, S.F. Epithelial cell-derived cytokines: more than just signaling the alarm. J Clin Invest. 2019, 129, 1441–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbeck R, Kozhich A, Koike M, Peng L, Andersson CK, Damschroder MM, Reed JL, Woods R, Dall’acqua WW, Stephens GL, Erjefalt JS, Bjermer L, Humbles AA, Gossage D, Wu H, Kiener PA, Spitalny GL, Mackay CR, Molfino NA, Coyle AJ. MEDI-563, a humanized anti-IL-5 receptor alpha mAb with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010, 125, 1344–1353. [CrossRef]

- Bleecker ER, FitzGerald JM, Chanez P, Papi A, Weinstein SF, Barker P, Sproule S, Gilmartin G, Aurivillius M, Werkström V, Goldman M; SIROCCO study investigators. Efficacy and safety of benralizumab for patients with severe asthma uncontrolled with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β2-agonists (SIROCCO): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016, 388, 2115–2127. [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, Korn S, Ohta K, Lommatzsch M, Ferguson GT, Busse WW, Barker P, Sproule S, Gilmartin G, Werkström V, Aurivillius M, Goldman M; CALIMA study investigators. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016, 388, 2128–2141. [CrossRef]

- Nair P, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, Bourdin A, Lugogo NL, Kuna P, Barker P, Sproule S, Ponnarambil S, Goldman M; ZONDA Trial Investigators. Oral Glucocorticoid-Sparing Effect of Benralizumab in Severe Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2017, 376, 2448–2458. [CrossRef]

- Busse WW, Bleecker ER, FitzGerald JM, Ferguson GT, Barker P, Sproule S, Olsson RF, Martin UJ, Goldman M; BORA study investigators. Long-term safety and efficacy of benralizumab in patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma: 1-year results from the BORA phase 3 extension trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019, 7, 46–59. [CrossRef]

- Cameli, P.; Aliani, M.; Altieri, E.; Bracciale, P.; Brussino, L.; Caiaffa, M.F.; Canonica, G.W.; Caruso, C.; Centanni, S.; D’Amato, M.; De Michele, F.; Del Giacco, S.; Di Marco, F.; Pelaia, G.; Rogliani, P.; Romagnoli, M.; Schino, P.; Schroeder, J.W.; Senna, G.; Vultaggio, A.; Benci, M.; Boarino, S.; Menzella, F. Sustained Effectiveness of Benralizumab in Naïve and Biologics-Experienced Severe Eosinophilic Asthma Patients: Results from the ANANKE Study. J Asthma Allergy. 2024, 17, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanagh, J.E.; Hearn, A.P.; Dhariwal, J.; d’Ancona, G.; Douiri, A.; Roxas, C.; Fernandes, M.; Green, L.; Thomson, L.; Nanzer, A.M.; Kent, B.D.; Jackson, D.J. Real-World Effectiveness of Benralizumab in Severe Eosinophilic Asthma. Chest. 2021, 159, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, S.; Bourdin, A.; Chupp, G.; Cosio, B.G.; Arbetter, D.; Shah, M.; Gil, E.G. Integrated Safety and Efficacy Among Patients Receiving Benralizumab for Up to 5 Years. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021, 9, 4381–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonica, G.W.; Blasi, F.; Carpagnano, G.E.; Guida, G.; Heffler, E.; Paggiaro, P.; Allegrini, C.; Antonelli, A.; Aruanno, A.; Bacci, E.; Bagnasco, D.; Beghè, B.; Bonavia, M.; Bonini, M.; Brussino, L.; Caiaffa, M.F.; Calabrese, C.; Camiciottoli, G.; Caminati, M.; Caruso, C.; Cavallini, M.; Chieco Bianchi, F.; Conte, M.E.; Corsico, A.G.; Cosmi, L.; Costantino, M.; Costanzo, G.; Crivellaro, M.; D’Alò, S.; D’Amato, M.; Detoraki, A.; Di Proietto, M.C.; Facciolongo, N.C.; Ferri, S.; Fierro, V.; Foschino, M.P.; Latorre, M.; Lombardi, C.; Macchia, L.; Milanese, M.; Montagni, M.; Parazzini, E.M.; Parente, R.; Passalacqua, G.; Patella, V.; Pelaia, G.; Pini, L.; Puggioni, F.; Ricciardi, L.; Ridolo, E.; Rolo, J.; Scichilone, N.; Scioscia, G.; Senna, G.; Solidoro, P.; Varricchi, G.; Vianello, A.; Yacoub, M.R.; Yang, B. Severe Asthma Network Italy Definition of Clinical Remission in Severe Asthma: A Delphi Consensus. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023, 11, 3629–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Lu, H.; Li, H.; Tang, M.; Tong, A. Development of therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of diseases. Mol Biomed. 2022, 3, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryman, J.T.; Meibohm, B. Pharmacokinetics of Monoclonal Antibodies. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2017, 6, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matera, M.G.; Calzetta, L.; Rogliani, P.; Cazzola, M. Monoclonal antibodies for severe asthma: Pharmacokinetic profiles. Respir Med. 2019, 153, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrok MJ, Wu Y, Beyaz N, Yu XQ, Oganesyan V, Dall’Acqua WF, Tsui P. pH-dependent binding engineering reveals an FcRn affinity threshold that governs IgG recycling. J Biol Chem. 2015, 290, 4282–4290. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorzelak-Pabis, P.; Luczak, E.; Wojdan, K.; Antosik, K.; Borowiec, M.; Broncel, M.; Chalubinski, M. Endothelial integrity may be regulated by a specific antigen via an IgE-mediated mechanism. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online). 2017, 71, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matucci A, Vivarelli E, Perlato M, Mecheri V, Accinno M, Cosmi L, Parronchi P, Rossi O, Vultaggio A. EGPA Phenotyping: Not Only ANCA, but Also Eosinophils. Biomedicines. 2023, 11, 776. [CrossRef]

- Maggi, L.; Rossettini, B.; Montaini, G.; Matucci, A.; Vultaggio, A.; Mazzoni, A.; Palterer, B.; Parronchi, P.; Maggi, E.; Liotta, F.; Annunziato, F.; Cosmi, L. Omalizumab dampens type 2 inflammation in a group of long-term treated asthma patients and detaches IgE from FcεRI. Eur J Immunol. 2018, 48, 2005–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harb, H.; Chatila, T.A. Mechanisms of Dupilumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2020, 50, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelaia, C.; Vatrella, A.; Busceti, M.T.; Gallelli, L.; Terracciano, R.; Savino, R.; Pelaia, G. Severe eosinophilic asthma: from the pathogenic role of interleukin-5 to the therapeutic action of mepolizumab. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017, 11, 3137–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies-Gow, A.; Wechsler, M.E.; Brightling, C.E. Unmet need in severe, uncontrolled asthma: can anti-TSLP therapy with tezepelumab provide a valuable new treatment option? Respir Res. 2020, 21, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauvreau, G.M.; Sehmi, R.; Ambrose, C.S.; Griffiths, J.M. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin: its role and potential as a therapeutic target in asthma. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2020, 24, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, T. TSLP expression: cellular sources, triggers, and regulatory mechanisms. Allergol Int. 2012, 61, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, R.; Kumar, V.; Copenhaver, A.M.; Gallagher, S.; Ghaedi, M.; Boyd, J.; Newbold, P.; Humbles, A.A.; Kolbeck, R. Novel mechanisms of action contributing to benralizumab’s potent anti-eosinophilic activity. Eur Respir J. 2022, 59, 2004306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazi, A.; Trikha, A.; Calhoun, W.J. Benralizumab--a humanized mAb to IL-5Rα with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity--a novel approach for the treatment of asthma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012, 12, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matucci, A.; Maggi, E.; Vultaggio, A. Eosinophils, the IL-5/IL-5Rα axis, and the biologic effects of benralizumab in severe asthma. Respir Med. 2019, 160, 105819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehmi, R.; Lim, H.F.; Mukherjee, M.; Huang, C.; Radford, K.; Newbold, P.; Boulet, L.P.; Dorscheid, D.; Martin, J.G.; Nair, P. Benralizumab attenuates airway eosinophilia in prednisone-dependent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018, 141, 1529–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vultaggio, A.; Accinno, M.; Vivarelli, E.; Mecheri, V.; Maggiore, G.; Cosmi, L.; Parronchi, P.; Rossi, O.; Maggi, E.; Gallo, O.; Matucci, A. Blood CD62Llow inflammatory eosinophils are related to the severity of asthma and reduced by mepolizumab. Allergy. 2023, 78, 3154–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesnil, C.; Raulier, S.; Paulissen, G.; Xiao, X.; Birrell, M.A.; Pirottin, D.; Janss, T.; Starkl, P.; Ramery, E.; Henket, M.; Schleich, F.N.; Radermecker, M.; Thielemans, K.; Gillet, L.; Thiry, M.; Belvisi, M.G.; Louis, R.; Desmet, C.; Marichal, T.; Bureau, F. Lung-resident eosinophils represent a distinct regulatory eosinophil subset. J Clin Invest. 2016, 126, 3279–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matucci, A.; Nencini, F.; Maggiore, G.; Chiccoli, F.; Accinno, M.; Vivarelli, E.; Bruno, C.; Locatello, L.G.; Palomba, A.; Nucci, E.; Mecheri, V.; Perlato, M.; Rossi, O.; Parronchi, P.; Maggi, E.; Gallo, O.; Vultaggio, A. High proportion of inflammatory CD62Llow eosinophils in blood and nasal polyps of severe asthma patients. Clin Exp Allergy. 2023, 53, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, G.E.; Knight, J.; Liu, Q.; Shelar, A.; Stewart, E.; Wang, X.; Yan, X.; Sanders, J.; Visness, C.; Gill, M.; Gruchalla, R.; Liu, A.H.; Kattan, M.; Khurana Hershey, G.K.; Togias, A.; Becker, P.M.; Altman, M.C.; Busse, W.W.; Jackson, D.J.; Montgomery, R.R.; Chupp, G.L. Activated sputum eosinophils associated with exacerbations in children on mepolizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/fasenra-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- Chia, Y.L.; Yan, L.; Yu, B.; Wang, B.; Barker, P.; Goldman, M.; Roskos, L. Relationship Between Benralizumab Exposure and Efficacy for Patients With Severe Eosinophilic Asthma. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019, 106, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moragón E, García-Moguel I, Nuevo J, Resler G; ORBE study investigators. Real-world study in severe eosinophilic asthma patients refractory to anti-IL5 biological agents treated with benralizumab in Spain (ORBE study). BMC Pulm Med. 2021, 21, 417. [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Galo, A.; Moya Carmona, I.; Ausín, P.; Carazo Fernández, L.; García-Moguel, I.; Velasco-Garrido, J.L.; Andújar-Espinosa, R.; Casas-Maldonado, F.; Martínez-Moragón, E.; Martínez Rivera, C.; Vera Solsona, E.; Sánchez-Toril López, F.; Trisán Alonso, A.; Blanco Aparicio, M.; Valverde-Monge, M.; Valencia Azcona, B.; Palop Cervera, M.; Nuevo, J.; Sánchez Tena, J.; Resler, G.; Luzón, E.; Levy Naon, A. Achieving clinical outcomes with benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma patients in a real-world setting: orbe II study. Respir Res. 2023, 24, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vultaggio, A.; Aliani, M.; Altieri, E.; Bracciale, P.; Brussino, L.; Caiaffa, M.F.; Cameli, P.; Canonica, G.W.; Caruso, C.; Centanni, S.; D’Amato, M.; De Michele, F.; Del Giacco, S.; Di Marco, F.; Menzella, F.; Pelaia, G.; Rogliani, P.; Romagnoli, M.; Schino, P.; Senna, G.; Benci, M.; Boarino, S.; Schroeder, J.W. Long-term effectiveness of benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma patients treated for 96-weeks: data from the ANANKE study. Respir Res. 2023, 24, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.Y.; Sedgwick, J.B.; Bates, M.E.; Vrtis, R.F.; Gern, J.E.; Kita, H.; Jarjour, N.N.; Busse, W.W.; Kelly, E.A. Decreased expression of membrane IL-5 receptor alpha on human eosinophils: II. IL-5 down-modulates its receptor via a proteinase-mediated process. J Immunol. 2002, 169, 6459–6466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, B.; Kirchem, A.; Phipps, S.; Gevaert, P.; Pridgeon, C.; Rankin, S.M.; Robinson, D.S. Differential regulation of human eosinophil IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF receptor alpha-chain expression by cytokines: IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF down-regulate IL-5 receptor alpha expression with loss of IL-5 responsiveness, but up-regulate IL-3 receptor alpha expression. J Immunol. 2003, 170, 5359–5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matucci, A.; Vultaggio, A.; Danesi, R. The use of intravenous versus subcutaneous monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of severe asthma: a review. Respir Res. 2018, 19, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vultaggio, A.; Perlato, M.; Nencini, F.; Vivarelli, E.; Maggi, E.; Matucci, A. How to prevent and mitigate hypersensitivity reactions to biologicals induced by anti-drug antibodies? Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 765747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergantini, L.; Pianigiani, T.; d’Alessandro, M.; Gangi, S.; Cekorja, B.; Bargagli, E.; Cameli, P. The effect of anti-IL5 monoclonal antibodies on regulatory and effector T cells in severe eosinophilic asthma. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023, 166, 115385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pini L, Bagnasco D, Beghè B, Braido F, Cameli P, Caminati M, Caruso C, Crimi C, Guarnieri G, Latorre M, Menzella F, Micheletto C, Vianello A, Visca D, Bondi B, El Masri Y, Giordani J, Mastrototaro A, Maule M, Pini A, Piras S, Zappa M, Senna G, Spanevello A, Paggiaro P, Blasi F, Canonica GW, On Behalf Of The Sani Study Group. Unlocking the Long-Term Effectiveness of Benralizumab in Severe Eosinophilic Asthma: A Three-Year Real-Life Study. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 3013. [CrossRef]

- Pelaia, C.; Crimi, C.; Benfante, A.; Caiaffa, M.F.; Calabrese, C.; Carpagnano, G.E.; Ciotta, D.; D’Amato, M.; Macchia, L.; Nolasco, S.; Pelaia, G.; Pellegrino, S.; Scichilone, N.; Scioscia, G.; Spadaro, G.; Valenti, G.; Vatrella, A.; Crimi, N. Therapeutic Effects of Benralizumab Assessed in Patients with Severe Eosinophilic Asthma: Real-Life Evaluation Correlated with Allergic and Non-Allergic Phenotype Expression. J Asthma Allergy. 2021, 14, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepretre, F.; Gras, D.; Chanez, P.; Duez, C. Natural killer cells in the lung: potential role in asthma and virus-induced exacerbation? Eur Respir Rev. 2023, 32, 230036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabogal Piñeros, Y.S.; Bal, S.M.; Dijkhuis, A.; Majoor, C.J.; Dierdorp, B.S.; Dekker, T.; Hoefsmit, E.P.; Bonta, P.I.; Picavet, D.; van der Wel, N.N.; Koenderman, L.; Sterk, P.J.; Ravanetti, L.; Lutter, R. Eosinophils capture viruses, a capacity that is defective in asthma. Allergy. 2019, 74, 1898–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murrison, L.B.; Brandt, E.B.; Myers, J.B.; Hershey, G.K.K. Environmental exposures and mechanisms in allergy and asthma development. J Clin Invest. 2019, 129, 1504–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vantaggiato, L.; Cameli, P.; Bergantini, L.; d’Alessandro, M.; Shaba, E.; Carleo, A.; Di Giuseppe, F.; Angelucci, S.; Sebastiani, G.; Dotta, F.; Bini, L.; Bargagli, E.; Landi, C. Serum Proteomic Profile of Asthmatic Patients after Six Months of Benralizumab and Mepolizumab Treatment. Biomedicines. 2022, 10, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.M. Clinical Pharmacology of Corticosteroids. Respir Care. 2018, 63, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdin, A.; Husereau, D.; Molinari, N.; Golam, S.; Siddiqui, M.K.; Lindner, L.; Xu, X. Matching-adjusted comparison of oral corticosteroid reduction in asthma: Systematic review of biologics. Clin Exp Allergy. 2020, 50, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lepretre, F.; Gras, D.; Chanez, P.; Duez, C. Natural killer cells in the lung: potential role in asthma and virus-induced exacerbation? Eur Respir Rev. 2023, 32, 230036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Vera, C.; García-Betancourt, R.; Palacios, P.A.; Müller, M.; Montero, D.A.; Verdugo, C.; Ortiz, F.; Simon, F.; Kalergis, A.M.; González, P.A.; Saavedra-Avila, N.A.; Porcelli, S.A.; Carreño, L.J. Natural killer T cells in allergic asthma: implications for the development of novel immunotherapeutical strategies. Front Immunol. 2024, 15, 1364774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkström, N.K.; Strunz, B.; Ljunggren, H.G. Natural killer cells in antiviral immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022, 22, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waggoner, S.N.; Reighard, S.D.; Gyurova, I.E.; Cranert, S.A.; Mahl, S.E.; Karmele, E.P.; McNally, J.P.; Moran, M.T.; Brooks, T.R.; Yaqoob, F.; Rydyznski, C.E. Roles of natural killer cells in antiviral immunity. Curr Opin Virol. 2016, 16, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminati, M.; Marcon, A.; Guarnieri, G.; Miotti, J.; Bagnasco, D.; Carpagnano, G.E.; Pelaia, G.; Vaia, R.; Maule, M.; Vianello, A.; Senna, G. Benralizumab Efficacy in Late Non-Responders to Mepolizumab and Variables Associated with Occurrence of Switching: A Real-Word Perspective. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).