1. Introduction

The scientific explanation of psychosis remains a challenge with significant implications for clinical practice in the field of mental health. During everyday interactions, individuals often make incorrect inferences about their environment, others, or themselves. However, metacognitive abilities allow them to correct these errors when presented with disconfirming evidence or through critical reasoning. In the state of psychosis, however, false ideas or perceptions can be maintained tenaciously despite contradictory evidence. Several frameworks have been developed to explain this process. Mechanistic models accounting for abnormalities in brain structure and signaling are necessary to understand psychosis; for instance, molecular imaging research on patients with a schizophrenia diagnosis showing an increase in dopamine synthesis in the striatum [

1]. However, cognitive frameworks have been regarded as a necessary mediation between the level of dysfunctional mechanisms and the level of clinical phenomenology [

2]. For instance, a two-factor account has been proposed as an explanatory model for the formation and maintenance of delusions in patients across the spectrum of psychosis [

3,

4,

5]. The first factor refers to a neurocognitive process leading to a significant change in subjective experience, which is felt as unexpected, salient, or abnormal by the individual. [

5,

6]. The second factor has been regarded as a failure in hypothesis evaluation. It considers the process from unexpected observations to the formation of new beliefs. More specifically, it has been characterized as a failure to reject hypotheses in the face of disconfirmatory evidence [

3,

5]. Some researchers in the field of cognitive science postulate that the second factor is an explicit metacognitive dysfunction, or a failure in the implicit monitoring and control of cognitive accuracy, which has been regarded by some theorists as implicit metacognition. [

3,

7]. Although the two-factor model has been developed for the analysis of delusions, it is helpful as well to understand the evaluation of hallucinations by the individual, and thus, the disturbance in perceptual reality monitoring that is frequent in patients suffering from psychotic states. [

8]

The first hit in this model has been classically described as a problem in the neuropsychological mechanisms of perception, as the initial studies focused on cases of delusional misidentification [

9]. However, if the attempt is made to explain psychosis in schizophrenia with the resources of a two-factor account, the neuropsychological impairments observed in this population involve several cognitive domains including perception, but also processing speed, attention, memory, executive function, and emotional processing [

10,

11]. These deficits are observed in ultra-high-risk individuals, chronic and late-onset schizophrenia patients [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The cognitive performance is heterogeneous ranging from mild impairment to dementia-like syndromes and it is significantly related to psychosocial functionality and insight [

10,

11]. The cognitive deficits have been observed consistently in patients with first episode psychosis before the use of antipsychotic medication [

15]. This basic neurocognitive factor is not sufficient for the generation of psychotic states in schizophrenia [

3,

5], but the presence of this kind of information processing can be seen also in non-clinical subjects who have had psychotic experiences according to community samples [

16].

The second hit can be characterized as an impairment of implicit or explicit metacognitive ability [

3,

5]. The term metacognition refers to the processes that enable us to evaluate our own mental operations through monitoring, self-regulation, and control of cognitive mechanisms. This leads to the capacity to recognize accurately, reflect, and regulate on our own mental representations [

17]. The metacognitive skills allow the person to identify a particular mental state, for example: experiencing a particular visual or auditory perception, executing a motor act, or accurately experiencing the evocation of information. This has been called metacognitive awareness [

1,

17,

18]. Also, these skills allow us to make judgments about these phenomena and compare incoming information to modify or rectify the judgment. This is called metacognitive confidence [

14,

16,

17,

19]. Finally, there is a predictive aspect in metacognition, which enable us to proofread to our own cognitive performance [

16]. Metacognitive dysfunction has related with poor outcomes in educational, work and social behavior. At the clinical level, a significant association between metacognitive deficits and the maintenance of delusional beliefs has been shown [

20].

Several resources have been developed to assess metacognitive deficits in patients with schizophrenia, including the Indiana Psychiatric Illness Interview, the Metacognitive Assessment interview, the Metacognitive Self-assessment scale, the Metacognition Assessment Scale-abbreviated, the Metacognition Questionnaire-30, as well as memory paradigms. For instance, the Feeling of knowing instrument or the Metamemory Inventory in Adulthood. The comparisons between groups of healthy subjects and patients with psychosis predominantly show a lower performance of the patient across the different measurement methods [

20,

21,

22]. It also possible observe a significant correlation between the scores of these instruments and the degrees of severity in several symptomatologic domains and functional outcomes [

22,

23,

24].

One of the limitations of metacognition assessment in clinical settings is the length of time required in the assessment. Also, the procedures that rely on exploring the patients' beliefs without measurements of cognitive performance data is questionable in terms of validity and objectivity. A way forward is to measure the overconfidence in judgment through the assessment of the correspondence between the beliefs about performance and the objective cognitive performance. This can be achieved with a simple and quick metamemory evaluation: a word list learning task. In this procedure, participants memorize a list of words. Before each recall trial, they are asked to predict the number of words they will be able to recall. Throughout the trials and presentations of the same word list, subjects have the opportunity to receive feedback on their performance and narrow the gap between their predictions and actual performance. The results depend on the accuracy of the relationship between the prediction and the recall: the number of words above or under the prediction can be subtracted from the number of words evoked. In patients with frontal damage, Luria [

25] and Vilkki [

26] described this methodology for the assessments of metacognition, and more specifically metamemory.

This study was focused on the assessment of metacognition in patients with schizophrenia. The aims of the study were: 1) to measure the overconfidence in metacognitive judgments through the prediction of word list recall; 2) to analyze the correlation between basic neurocognition (memory and executive function), metacognition (through a metamemory test) and the severity of psychotic symptoms (as measured with the PANSS). We expect a positive correlation between errors in recall prediction and the severity of the positive symptom factor of the PANSS; also, we expect that overconfidence explains a higher variance in positive symptoms, through a prediction model. 3) Finally, we expected to find a correlation between overconfidence scores and the levels of functionality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Setting

The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the National Institute of Psychiatry of Mexico (Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz, INPRFM) with number CEI/C/029/2022.

Participants and selection criteria. A total of 51 participants were included. The participants met the following inclusion criteria: a) diagnosis of schizophrenia, b) age of 18 years or more, c) minimum schooling of six years, d) currently receiving antipsychotic treatment, and e) at least one year with the diagnosis. We excluded participants with delusional disorder, substance induced psychosis, schizoaffective disorder, major neurocognitive disorder or any other serious psychiatric comorbidity, catatonic syndrome, or active consumption of any substance other than tobacco. Severe or uncontrolled medical illnesses were also discarded. All participants signed an informed consent letter.

2.2. Procedure and Data Collection

Clinical diagnosis the of Schizophrenia was made by a specialized psychiatrist, following the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th version (DSM-5). After verifying inclusion/exclusion criteria, participants signed an informed consent letter. The research’s assistants with medical degrees were trained in the administration of the tests. Under the supervision of the principal investigator, the assessment was performed in a single session, into a quiet, sound-controlled, and illuminated room. The assessment was conducted in the following order: registration of demographic and clinical data, PANSS interview, Metacognitive test and FAST. The complete evaluation lasted about 90 minutes.

Demographic and clinical data were obtained with a structured interview: age, years of educations, age of onset, illness duration, hospitalizations and pharmacological treatment.

Metacognition test. The subtest of Metamemory included in the Executive Functions and Frontal Lobe Battery (BANFE- 2) was used [

27]. The test consists in learning a 9 words list presented in the same order over 5 trials. Prior to each trial, participants must indicate how many words they believe they will remember, and this number is recorded. Subsequently, the list of words is read aloud, and the participant is asked to recall as many words as possible. The number of words recalled is then recorded. The difference between the predicted number of words and the actual number recalled is calculated. A positive difference (where the prediction exceeds the actual recall) is considered an indication of overconfidence or overestimation, while a negative difference (where the prediction falls short of the actual recall) is considered underestimation. A score of zero indicates equivalence between prediction and performance. This assessment battery has been adapted and standardized for the Mexican population and is sensitive to academic years or school experience. The normative data adjusted for age and schooling were also recorded for the overconfidence and underestimation errors to determine the level of impairment. Memory assessment. Total recall over 3 trials of word list was obtained. Each trial is scored with one point for each word recalled. The total recall is obtained by averaging the number of correct responses reported over the three trials. The normative data adjusted for age and schooling for the performances were obtained to determine the level of impairment. Perseverative and intrusive words expressed by the participants were recorded during the 5 trials in the subtest of Metamemory. These responses are considered a proxy indicators of executive dysfunction. The first were classified within the domain of inhibitory control, and the second were classified within the domain of interference inhibition.

Psychopathology. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) was used to assess the severity of psychiatric symptoms. In the present study, the adaptation for Mexican population was used. Five main factors have been identified: positive, negative, cognitive, anxiety/ depression, and excitation [

28]. The factor of positive symptoms, including delusions and hallucinatory behavior, is used as a measure of psychotic states.

Social Functioning. We used The Brief Functioning Assessment Scale (FAST) to evaluate the following aspect: autonomy, work activity, cognitive functioning, finances, interpersonal relationships, free time. This instrument has been adapted to Spanish version for its usage in patients with schizophrenia [

29].

2.3. Statistical Analysis.

Descriptive statistics were performed for clinical and sociodemographic data, and a Pearson correlation test were used to assess the relationships between positive and negative factors of the PANSS, the total number of errors, the number of perseverative and intrusive responses, and FAST score. A multiple lineal regression was conducted with variables significantly related to the positive symptoms.

3. Results

A total of 51 participants were evaluated: 22 women and 29 men. The demographic and clinical data are shown in

Table 1. In our sample, patients exhibited moderate severity of symptoms according to the PANSS, despite pharmacological treatment. These data indicate the presence of both positive and negative symptoms, which are evident in the sample. Additionally, the assessment of memory indicates that mild, moderate, and severe verbal memory impairments are identifiable in 92.1% of the sample. Regarding metacognitive performance, overconfidence errors were present in 51% of the patients compared to normative data, while a lower percentage of 27.4% showed underestimation errors compared to the normative data.

In

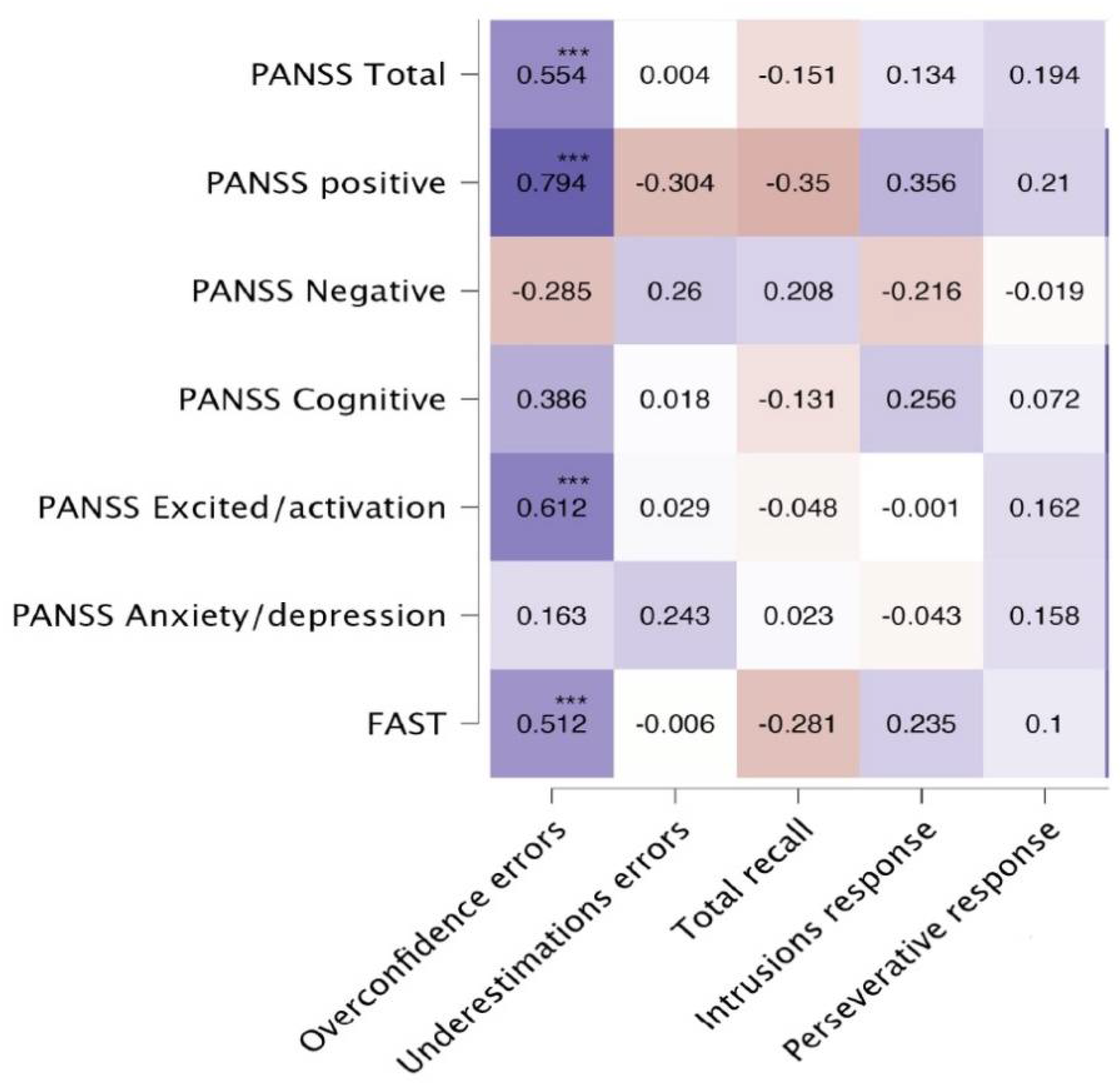

Figure 1, we show the correlation coefficients (Pearson’s test) between the psychopathological scores, the social functioning test, and the scores on the Metamemory Test. As we expected, the strongest correlation, after the Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons, is observed between overconfidence errors and the positive factor of the PANSS (r = 0.774, p < 0.001). In contrast, a negative correlation was observed between positive symptoms and underestimation errors. Unexpectedly, we found significant correlations between overconfidence errors and the excitation factor, as well as with the PANSS and the FAST total scores. The total number of errors in the Metamemory Test shows a correlation of lower magnitude with the same subscales of the PANSS; a discrete correlation was observed between intrusive responses and positive symptoms, which was not significant after Bonferroni’s correction.

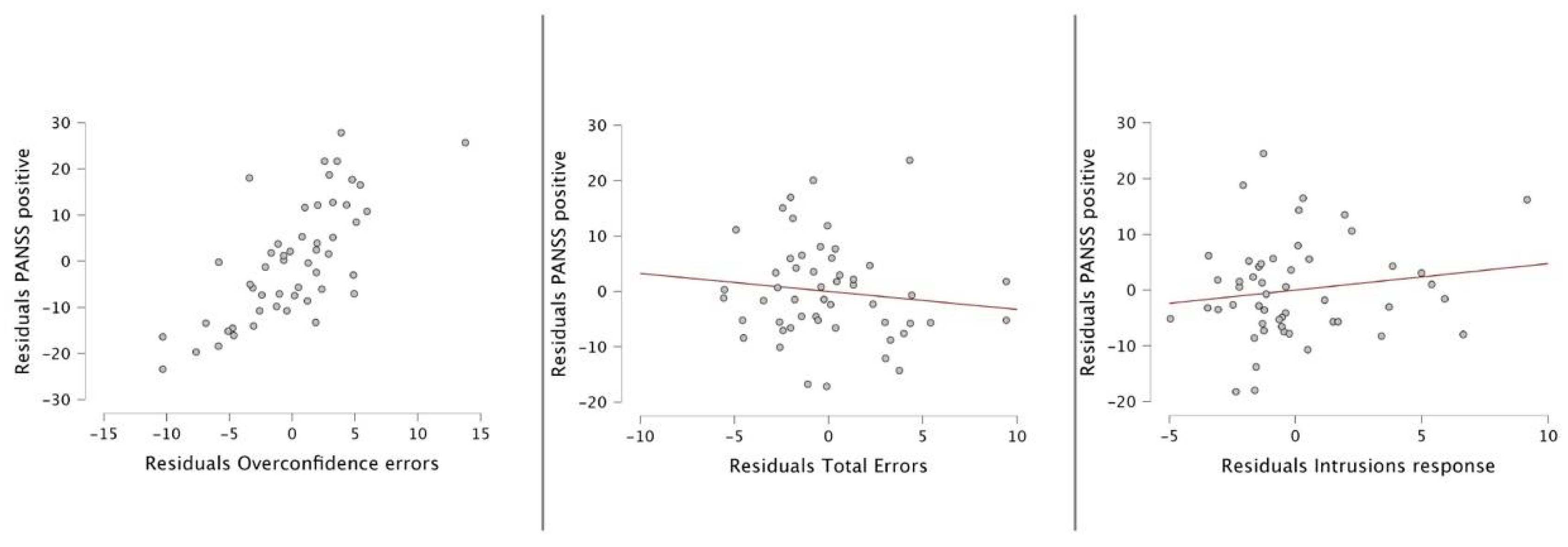

The multiple lineal regression model for predicting positive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia revealed significant correlations with overconfidence errors (r=0.794***), total errors of metamemory test (r=0.417**) and the intrusion response (r= 0.356**). For the enter model, the results were r=0.78, r

2=0.61; F=24.57 and p< 0.001. The only significant predictor in the model was overconfidence errors.

Table 2 shows the model summary, and figure 2 shows the partial regression plots.

4. Discussion

The background problem that gives rise to this study regards the explanation of psychosis through the study of metacognition in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The study of metacognitive dysfunction contributes to the explanation of the psychotic states, and more specifically, to the onset and maintenance of delusions. To approach this general question from an empirical perspective, we studied the overconfidence in metacognitive judgments through the prediction of a word list recall, in a sample of patients with schizophrenia. As the main result, we observed an increased number of overconfidence errors, which implies that patients tend to overestimate their own ability to remember a list of words. This finding is consistent with previous descriptions in patients with schizophrenia regarding the presence of overconfidence judgments about memory capacities. Although our study focused on verbal memory, it is interesting to observe that the failures in the metamemory process have been identified in verbal, visual and episodic forms of memory by means of different stimulus presentations: word pairs, word lists, static images and videos [

30,

31,

32,

33]

We used the two-factor model of delusions as an explanatory framework to approach the problem of psychosis in our sample, as this model is compatible with the study of implicit or explicit metacognition. In our own adaptation of the model, factor 1 was approached through basic neurocognitive measures of verbal memory, and with the measurement of intrusive and perseverative responses, as proxies for the executive control of memory retrieval. We did not find a correlation between positive symptoms and perseverative responses or total memory recall. However, we observed a correlation between the positive symptom factor of the PANNS and the number of intrusion errors, which can be regarded as a form of interference due to failures in inhibitory control. This proxy to the assessment of executive functioning points to the possible influence of these variables on the generation or maintenance of the positive symptoms of psychosis. As known, the exact relationship between executive functioning and psychosis remains elusive [

34]. It has been described that failures in several executive processes are associated with the presence of psychopathology in general terms [

35,

36], but limited evidence is available on their specific association with psychosis [

37]. White et al [

37] showed significant associations between psychotic symptoms and working memory, response inhibition, attention vigilance and cognitive flexibility. Interestingly, these authors do not observe correlations with impulsivity, which is consistent with our study. This finding and the available literature lead us, along with other authors, to believe that the nature of the first hit is mostly heterogeneous. In their most recent review, Lee et al. [

38] shows the significant variability in the scores observed in patients with psychosis; this heterogeneous and variable profile is observed not only in executive functions, but also in processing speed, attention, memory and learning. Although not enough literature is available in this regard, we do not reject the possibility that other executive functions impairments that have been widely reported in patients with psychosis, such as failures in working memory, could have a greater weight as basic neurocognitive disturbances contributing to the generation of positive symptomology. In our study, however, the logistic regression analysis showed that only metacognitive errors predicted psychotic symptomatology. This is consistent with the proposal by Coltheart and Davies [

3,

5] who state that first factor is not sufficient for the generation of delusions, and that a bias against disconfirmatory evidence (BADE) is necessary to explain the maintenance of delusions. This approach has also been replicated in other models with different metacognitive measures [

30,

32,

37,

39].

An alternative formulation to BADE has been proposed by one-factor theorists, based on a predictive processing account. According to this explanatory framework, delusions are conceptualized as beliefs that evolve over time, involving a negotiation between existing beliefs and the available evidence under conditions of uncertainty. In this framework, unexpected experiences may trigger the formation of delusional beliefs. However, once this belief is formed, it "creates new expectations about uncertainty that reduce updating but also facilitate the flexible assimilation of contradictory evidence.” [

40] From our perspective, the predictive processing framework is useful as a theoretical tool for the explanation of psychosis; however, our results highlight the relevance of a metacognitive bias of overconfidence, strongly correlated with psychotic symptoms. Thus, our study supports the hypothesis of metacognitive defects contributing to the failure to reject contradictory evidence.

The results of our study highlight the relationship between metacognition and psychotic symptoms in a sample of patients with schizophrenia. From our perspective, these findings align with current mechanistic models of schizophrenia that focus on the role of prefrontal cortex. Metacognitive abilities related to memory tasks have been found to be impaired in patients with frontal lobe damage; for instance, lesions affecting Brodmann areas 10 and 46 in humans and monkeys lead to changes in confidence formation, but not first-order task performance. The connectivity of the prefrontal cortex with other cortical and subcortical structures is relevant to understand the development of metacognition [

17]. As known, prefrontal abnormalities in structure and function are among the most consistently observed in patients with schizophrenia: for instance, disturbances in cortical thickness of the lateral and medial aspects of the prefrontal cortex, with a moderate size effect (Cohen’s

d), as compared to healthy subjects matched for demographic variables [

41]

Our results showed an unexpected correlation between overestimation scores and excitability symptoms: hostility, uncooperativeness, and poor impulse control. In this regard, literature has postulated that metacognitive skills are not directly related to the presence of aggressive or hostile behavior; however, these skills play a mediating role in the occurrence of hostile behavior when individuals show a poor performance in monitoring abilities and simultaneously present a significant reactivity to emotions such as anger [

42]. The interplay between metacognition and impulsivity is challenging because we are not aware of an integrative framework providing a full explanation of the connection between these variables. However, different theories have been proposed: the conflict monitoring theory, the integrative self-control theory, the process model of self-control, the metamotivation model, the triat models, and the self-regulated learning and problem-solving models [

43]. Marie Hennecke and Sebastian Bürgler [

43] propose that there are two sets of metacognitive components including self-awareness and metacognitive regulatory processing that function during and after self-control behavior. According to this perspective, failures in either component could potentially influence the presentation of poor impulse control behaviors. Thus, our findings could indicate that overconfidence errors are related with the presence of hostility and impulse control failures in our patients since overconfidence is indicative of a monitoring problem or a difficulty in self-awareness.

Finally, we found a correlation between overconfidence scores with the levels of social functioning. It has been postulated that metacognitive skills are the bridge between neurocognitive skills and real-life outcomes such as work, school and the generation of interpersonal relationships. Specifically, it has been proposed that having an accurate perception of our abilities and limitations allows us to more effectively guide our behavior [

44]. In patients with schizophrenia, it has been observed that overestimation predicts impaired outcomes in residential, social and vocational domains [

45,

46]. In this sense, our findings point in the same direction showing that levels of overconfidence are related to worse performance on the total score of a functionality test that includes social, occupational, hobbies and financial domains.

The strengths of this study rely on the utility of a friendly measure for the clinical study of metacognition in patients with chronic psychosis. However, our study has important limitations: the sample size is discrete, which does not allow generalizations; on the other hand, our clinical population is limited to patients with schizophrenia. Thus, we do not know if this same phenomenon can be replicated with other psychotic disorders. A broader evaluation of the different neurocognitive and metacognitive domains could be helpful in the future to develop more specific proposals on a two-strike theory of psychosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F-M, R.A.B, R.S-A; methodology, Y.F-M. M.F-R, R.S-A; Data collection R.A.B, Y.F-M.; analysis, Y.F-M, J.R-B; writing—original draft preparation, Y.F-M, J.R-B; writing—review and editing, Y.F-M, J.R-B, M.F-R, R.S-A; supervision, J.R-B; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.