1. Introduction

Kefir is a homemade viscous fermented beverage obtained by the incubation of milk with kefir grains, a stable community of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), acetic acid bacteria (AAB), and yeasts included in a protein-polysaccharide (kefiran) matrix [

1,

2,

3,

4]. During fermentation, microorganisms duplicate in the grain and produce the matrix components, incrementing grain biomass [

5]. Furthermore, a dynamic partitioning of microorganisms between grain and milk happens, where free/planktonic microorganisms reproduce each one with their own kinetics, and a metabolic cooperation between members of the community is produced [

5,

6,

7,

8].

High-throughput sequencing investigations in kefir grains and their corresponding fermented milk demonstrated an uneven distribution of microorganisms between grain and fermented product, making the microbial community more diverse in the fermented product [

8,

9,

10]. While Lactobacillaceae is the prominent family present in the grain, represented by the microorganisms formerly included in the

Lactobacillus genus, being L kefiranofaciens the most abundant in the grain; in the fermented product

Lactococcus is predominant, accompanied by

Acetobacter,

Lactobacillus and

Leuconostoc. The most common fungal genus across both kefir and kefir grains is

Kazachstania, along with

Kluyveromyces, Naumovozyma, and

Saccharomyces. Regarding yeast community, the main difference between grains and kefir is the higher proportion of

Dekkera found in the fermented product [

8,

9,

11,

12,

13].

Kefir grain microbiota composition depends on the origin of the grain and affects microbiota of the fermented product. Other variables such as type of milk, temperature and time of fermentation among others also affect microbial composition of kefir [

14,

15]. Studies of commercial Turkish kefir microbiota demonstrated that the most abundant genus present is

Lactococcus, followed by

Streptococcus,

Lactobacillus, and

Leuconostoc [

16]. Walsh et al. (2023) used 64 kefir grains from different countries to prepare kefir and deep study of the microorganisms present in the fermented product was performed by using a metagenomic-based approach. This study allowed the definition of a pattern of domination, including the species

Lactococcus lactis subsp.

lactis,

Lactobacillus helveticus and

Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens. Only a few samples are dominated by

Acetobacter orientalis or

Leuconostoc mesenteroides [

17]. This pangenome study determined a core microbiome in kefir represented by

Lactobacillus helveticus,

Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens,

Lactococcus lactis subsp.

lactis or

Lactococcus cremoris subsp.

cremoris, which could be defined as the minimal bacterial composition of a fermented milk to be considered as kefir.

Milk fermentation by kefir grains leads to the production of different metabolites, including lactic acid, acetic acid, CO

2, acetaldehyde, acetoin, and diacetyl, which provide the unique organoleptic properties of this beverage. Moreover, the exopolysaccharide kefiran, produced by

Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens subsp.

kefiranofaciens during fermentation [

18,

19], is necessary for grain growth and contributes to the rheological properties of the fermented product [

20,

21]. The organoleptic qualities of kefir are subjected to variations due to factors such as the origin of the kefir grain, the type of milk, the grain-to-milk proportion, and culture conditions [

11,

15,

22]. Both the physicochemical properties and the metabolites of kefir may depend on microbial activity during fermentation, which could significantly affect the health-promoting properties of this fermented beverage [

23].

Regarding this, the analysis of the physiologically active microbial cells of kefir is relevant to understanding the relation between the microbial active profile and the physicochemical properties of the fermented product obtained. The analysis of the physiologically active microbial cells in a specific time or place can be done by sequencing the complete set of protein-coding RNA transcripts using high-throughput NGS technologies called RNA-Seq [

24]. The metatranscriptome analysis of a complex community of microorganisms, such as that present in kefir, elucidates the expression and regulation of the complete transcripts from those active populations [

25]. Additionally, a more accurate composition of bacteria and yeast of the kefir community could be achieved by seeking transcripts of housekeeping and ribosomal protein genes, generating a transcriptionally active microbiome (TAM) [

26,

27].

The present study aimed to compare the functionally active microbiota present in two kefirs differing in rheological features using a metatranscriptomics approach to attempt understanding the relation between differences in physicochemical and rheological properties of kefir and the microbial active profile associated with each product.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Kefir Grains and Fermented Milk (Kefir) Preparation

Two different frozen stocks of kefir grain CIDCA AGK1 from the CIDCA collection (UNLP, Argentina) were used to obtain the corresponding fermented products: kefir MKAA1 and kefir MKAA2. Grains were inoculated in commercial skim milk UHT (La Serenisima, Argentina) in a ratio grain/milk 10% w/v and cultured by successive passages in milk at 20 °C for 24-48 h as described by Garrote et al. [

22]. Several subcultures (back slopping) were performed to maintain the grains in an active form and grain weight increment was determined. Kefir for microbiological and physicochemical analyses was prepared by inoculation of 3 g of kefir grain in 100 ml of milk and then incubated during 48 h at 20 °C followed by 24 h incubation at 4 °C.

2.2. Physicochemical and Microbiological Characterization of Fermented Milk

To determine the concentration of viable microorganisms in kefir, the fermented product was diluted in tryptone 0.1% w/v, and the appropriate dilutions were plated on MRS agar (Biokar Diagnostic) for LAB and YGC agar (Biokar Diagnostic) for yeasts. The results were expressed as colony-forming units (CFU) per ml of fermented product.

The quantitation of organic acids was performed by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) employing an ion exchange column (AMINEX HPX-87H, Bio-Rad Labs, USA). Kefir was centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 15 min at room temperature (Avanti J25, Beckman Coulter Inc., USA) and filtered through a 0.45 µm pore diameter membrane (Millipore Corporation, USA). The protocol used was previously described by Garrote et al. (2000). The identification and quantification of organic acids were based on comparing retention times of calibration curves with HPLC grade standard acids (Sigma Chemical Co.). pH was measured using a HI1131B microelectrode coupled to a pH meter pH 211 (Hanna Instrument, USA). The apparent viscosity of fermented milk was estimated at 25 °C in a Haake ReoStress 600 rheometer using a plate-plate sensor system PP35 with a gap of 1mm (Thermo Haake, Karlsruhe, Germany) according to Hamet et al. [

28]. Shear stress was determined as a function of shear rate. Apparent viscosities (mPa.s) were calculated at 300 s−1. All the determinations were performed in at least three independent samples.

2.3. Identification of the Transcriptionally Active Microorganisms in Kefir by RNA-Seq Analysis

One millilitre of kefir was centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 x g; the cell pellet was transferred to a microtube with 0.3 g of zirconium beads, ruptured in the FastPrep-24 equipment (MP Biomedicals), and total RNA was extracted using the RNAeasy mini kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The extracted RNA was reversed-transcripted to cDNA to build libraries for NGS sequencing. The samples were divided into two parts, one destined to analyze the bacteria and the other to study yeasts. The bacterial sample was treated with the Ribo-Zero rRNA removal kit, and the yeast sample was enriched with the capture of mRNAs by the poly-A tail, all the procedures according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Illumina).

The cDNA libraries were elaborated according to the RNA Sample sequencing protocol from Illumina, which consisted of the following steps: purification and fragmentation of mRNA; synthesis of the first cDNA chain; synthesis of the second cDNA chain; repair of extremities; adenylation, adapter binding, amplification, library validation, standardization and pool of libraries, and sequencing by bridging PCR in MiSeq sequencer, all these procedures as stated by the manufacturer (Illumina). MiSeq reagent kit v3 (600-cycle) enabled the highest output of sequenced information (15 Gb, 2x300 bp, up to 25 million reads).

2.4. Bioinformatic Analysis

The bioinformatics analysis was done in the servers Sagarana and Truta, located at the Laboratories of Informatics of the ICB/UFMG and Fiocruz/MG, using a GNU Linux/Debian operating system. Some computational algorithms were developed and made in Python throughout the project. Multithreading was used to increase performance and reduce the processing time associated with the programs. The in-house metatranscriptome pipeline for analyzing large RNA-seq datasets in Docker containers for supercomputing cluster environments pipeline is described in detail by Rios et al. [

26]. It creates a manifest.tsv file describing the application settings, location of databases, and fastq files. Briefly, the pipeline performs the first step of processing raw DNA paired-end reads forming consensus sequences which are aligned using the HS-BLASTN accelerating Megablast search tool [

29] against the NCBI RefSeq database; the taxonomic identification uses algorithms similar to MEGAN [

30], the functional annotation is also done using the generated RefSeq.json file, along with another pre-processed file that cross-references between NCBI proteins accession numbers and KO, already in the KEGG hierarchy (acc2KO.json).

In the second step, the reads are mounted in contigs by Trinity software [

31], which are analyzed, and predicted protein-coding regions extracted by the TransDecoder tool [

32] the contigs not annotated are now annotated taxonomically and functionally by the AC-DIAMOND v1 tool [

33]. The transcoder identified which contigs are mRNA and what possible ORFs are. The AC-DIAMOND aligns by BLASTx the annotated contigs as mRNA against the NCBI NR database (non-redundant protein sequences) and UEKO-UniRef Enriched KEGG Orthology [

34]. Lastly, the STAR tool [

35] aligned the reads against mRNA-annotated contigs to quantify the gene expression.

In the third step, due to our experimental design’s absence of biological replicates, we compared paired kefir samples through a fast Bayesian statistic method called CORNAS – Coverage-dependent RNA-Seq [

36]. The sequencing coverage and size values of contigs aligned with AC-DIAMOND were used in the analysis. A sequencing coverage parameter determined from the concentration of the RNA sample was used to estimate the posterior distribution of true gene counts to support calling differentially expressed genes (DEG). Genes were considered differentially expressed if the 0.5th percentile of the count probability distribution for one sample was at least two-fold higher than the 99.5th percentile of the other sample.

The comparison of data sets through Venn diagrams used the InteractiVenn web-based tool [

37]. Other scientific analyses and graphing were done in GraphPad Prism 6 (Dotmatics). The pipeline generates smear MA plots, PCC plots, and Heatmap graphics as a final output. MA plots were generated to visualize the variances between differentially expressed genes in the RNA-seq libraries. Points are annotated genes, the x-axis indicates the log10 normalized mean average, and the y-axis shows the log2 fold change. The KEGG mapping occurred between the kefir libraries, and colours stated the most significant differentially expressed genes. The native R function cor (x, y, method) in version 4.3.1 measured Pearson’s correlation coefficient values between KO pathway genes to build PCC plots. Heatmap graphics were created in RStudio, using dplyr, glue, fs, stringr, ggplot2, treeio, ggtree, and ggnewscale software tools. All libraries were normalized to 300 million reads, and values were converted to log10. The heatmaps from the bacteria and yeast libraries had a limit of 25 and 15 species, most expressed in absolute normalized reads, respectively (

Supplementary Information File).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Kefir Biomass Growth during Successive Subcultures and Physicochemical and Microbiological Characterization of Kefir

Two stocks of frozen kefir CIDCA AGK1 grains (MKAA1 and MKAA2) inoculated into skim milk and incubated for 24 h increased their weight differently. The analysis of grain growth as a function of the number of subcultures (

Figure 1A) showed that stock MKAA1 increased its biomass, reaching a 5-fold increment after 20 subcultures, while stock MKAA2 only doubled its weight. The difference in grain growth behavior was not reflected in the total number of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts observed in each grain, with 3.5x108 CFU/g LAB and 3x107 CFU/g yeasts evidenced in MKAA1 and 1.25x108 CFU/ml LAB and 6.5x107 CFU/ml yeasts in MKAA2.

In kefir fermented milk, the numbers of viable lactic acid bacteria and yeasts were not significantly different between kefir MKAA1 and MKAA2, reaching values of 2x109 CFU/mL for LAB and 3x106 CFU/mL for yeasts (

Table 1). However, kefir obtained with both grains had different pH values after 48h fermentation. The pH of kefir MKAA1 was 4.28, while kefir MKAA2 showed a significantly lower pH value (4.07). A decrease in pH is associated with the production of organic acids during fermentation, which represents an essential feature because they are linked to the organoleptic characteristics as well as the antimicrobial properties of the final product [

5]. The organic acid profiles of both kefirs revealed that lactic and acetic acid were the main organic acids produced (

Table 1), with kefir MKAA2 showing higher levels of both acids. These results are in concordance with the lower pH observed for kefir MKAA2.

Flow curves of both kefirs displayed a pseudoplastic behaviour, with kefir MKAA1 showing a higher hysteresis loop (

Figure 1B). Furthermore, the apparent viscosity of kefir MKAA1 determined at 300 s-1 was higher than that observed for kefir MKAA2. This difference could be associated with changes in the kefir grain and/or the fermented milk active microbiota that influences the production of kefiran, an exopolysaccharide that plays a crucial role in improving the rheological properties of kefir [

38].

3.2. Sequencing Overview

Normalized mRNA read counts were used for taxonomic and functional profile analysis of both kefir beverages’ microbial communities. High-quality sequencing data were generated for all samples (yeast and bacteria libraries of milk kefir MKAA1 and MKAA2). After merging the corresponding paired-end reads, quality control assessment, and trimming sequencing artefacts and duplicates, a total of 9 million reads resulted for all further downstream analyses (a mean of 2.25 million sequences per sample), 6.6 million and 2.4 million reads mapped to bacteria and yeasts, respectively. Unclassified reads were observed, approximately 4.74% of the kefir transcripts (

Table 2).

Read counts in the four sequencing libraries ranged from 1,046,458 in MKAA2 (yeast) to 4,113,272 in MKAA1 (bacteria). In these, the reads identified taxonomically by HS-BLASTN ranged from 76.5% in MKAA2 (yeast) to 97.9% in MKAA1 (bacteria). The reads identified as part of an mRNA by TransDecoder ranged from 57.3% in MKAA1 (yeast) to 74.4% in MKAA1 (bacteria). Reads annotated with KEGG Orthology Entries (KO) ranged from 42.2% in MKAA1 (yeast) to 64.4% in MKAA1 (bacteria). Combining all the strategies employed to attempt the taxonomic and functional affiliation of the reads, the percentage of reads annotated by the pipeline ranged from 90.8% in MKAA2 (yeast) to 98.59% in MKAA1 (bacteria) (

Table 2).

Trinity-generated contigs varied from 41,450 in MKAA1 (bacteria) to 63,859 in MKAA2 (yeast), TransDecoder-identified as mRNA ranging from 40.5% in MKAA2 (bacteria) to 47.2% in MKAA2 (yeast) and then annotated by KEGG Orthology (KO) ranged from 29.5% in MKAA1 (yeast) to 34.8% in MKAA2 (yeast) (

Table 3).

3.3. The Transcriptionally Active Microbiome (TAM) of MKAA1 and MKAA2 Kefir

3.3.1. Bacteria Taxonomy in the Metatranscriptome of Kefir Beverages

Microbial communities of kefir MKAA1 and MKAA2 were assessed based on all mRNA reverse-transcripted bacteria and yeast typing genes. The nomenclature used here was after reclassifying the genus

Lactobacillus into 25 genera and the family Lactobacillaceae containing all genera formerly of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae [

39,

40].

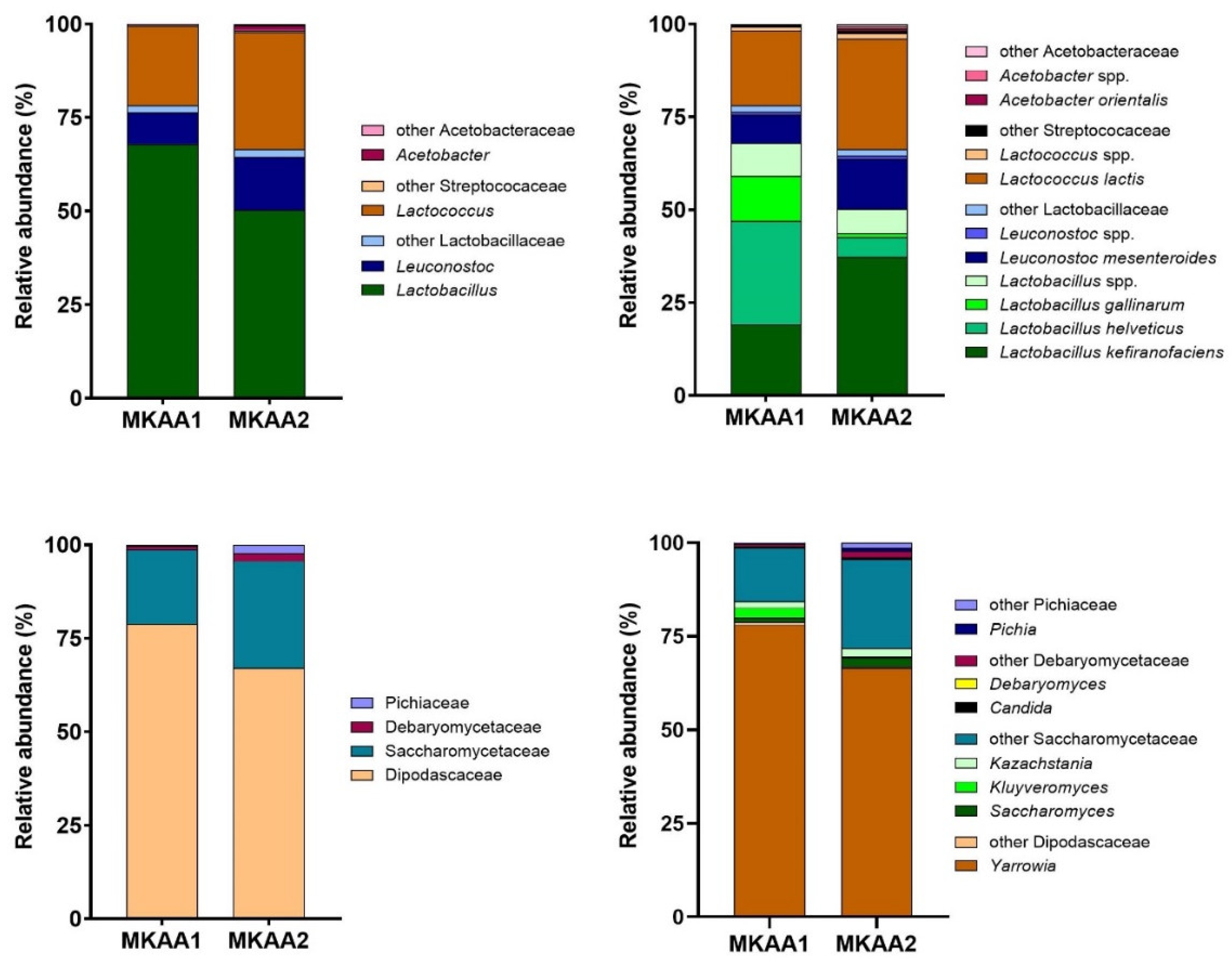

In the bacterial transcriptionally active microbiome (bTAM) analysis, the Firmicutes and Proteobacteria phyla comprise almost all protein-related readouts. However, the importance of each phylum in the milk kefir samples is slightly different, with Firmicutes and Proteobacteria accounting for 99.8% and 0.2% in MKAA1 and 98.3% and 1.7% in MKAA2, respectively. The LAB families Lactobacillaceae and Streptococcaceae dominated the bTAM (MKAA1 78.3%, 21.5%; MKAA2 66.5%, 31.9% respectively) while the AAB family Acetobacteraceae had only marginal counts (0.2% to 1.7%).

The main bacterial genera in MKAA1 and MKAA2 samples belong to the genus formerly named

Lactobacillus (67.9% and 50.3%),

Lactococcus (21.1% and 31.3%), and

Leuconostoc (8.40% and 14.2%), respectively (

Figure 2, upper panel). Genus Acetobacter also showed marked differences between both kefirs, with a higher proportion in MKAA2 (1.25%) than in MKAA1 (0.12%). Analyzing the MKAA1 sample,

Lactobacillus helveticus (27.7%),

Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens (19.2%),

Lactobacillus gallinarum (12.2%),

Lactococcus lactis (20.2%), and

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (7.76%) were more conspicuous. However, in the MKAA2 sample, the relative abundance of these species was distinct, with

L. helveticus and

L. gallinarum having marginal roles (5.31% and 0.94%, respectively), whereas

L. kefiranofaciens (37.3%),

L. lactis (29.9%), and

L. mesenteroides (13.4%) predominated (

Figure 2, upper panel).

These results are in concordance with previously published data at similar fermentation stages where

L. kefiranofaciens,

L. helveticus,

Lactococcus lactis and/or

Leuconostoc mesenteroides were considered the dominant microbiota depending on the grain and the fermentation time [

8,

17] Metagenomic sequencing of kefir revealed a shift from

L. kefiranofaciens to

Leuconostoc as the dominant species during fermentation ([

17]) indicating that time of fermentation is a crucial factor affecting microbial domination .

L. gallinarum was detected as metabolically active in kefir MKAA1 and was not described as dominant by metagenome analysis in the previous report. Considering results obtained in both kefir samples, it is noteworthy that active lactobacilli found in the highest proportion (

L. helveticus,

L. kefiranofaciens and

L. gallinarum) were all grouped in the same clade according to the new taxonomical classification that reflects the phylogenetic position of the microorganisms with shared ecological and metabolic properties [

40]. On the contrary, microorganisms that were isolated from these kefir grains in previous studies or have been described in the kefir grain microbiome, such as

Lentilactobacillus kefiri,

Lacticaseibacillus paracasei, or

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum were not dominant in the fermented milk when analyzing bTAM [

10].

Comparing the bTAM of MKAA1 and MKAA2 with two Brazilian milk kefirs [

26] (Rios et al., 2023), there are remarkable differences in their relative abundances. In Brazilian kefirs, the most prevalent bacterial genera were

Leuconostoc (60%),

Lactobacillus (25%) and

Lactococcus (6%), while in Argentinian kefirs were

Lactobacillus (59%),

Lactococcus (26%) and

Leuconostoc (11%).

3.3.2. Yeast Taxonomy in the Metatranscriptome of Kefir Beverages

The Ascomycota phylum was dominant in yeast transcriptionally active microbiome (yTAM), with >99.9% of total protein-related reads. The families Dipodascaceae and Saccharomycetaceae were the most abundant in both samples (MKAA1, 78.8%, 19.9%; MKAA2, 67.0%, 28.6%, respectively), with a shallow occurrence of Debaryomycetaceae and Pichiaceae (

Figure 2, lower panel). The main genus in the microbiome was

Yarrowia (MKAA1, 78.0% and MKAA2, 66.5%), represented by the species

Y. lipolytica, followed by other Saccharomycetaceae genera with low counts of

Kazachstania,

Kluyveromyces, and

Saccharomyces (around 2% each) (

Figure 2, lower panel). These results concord with those described by Walsh et al. [

17], who found that

Saccharomyces eubayanus,

Kluyveromyces marxianus, and

Saccharomyces cerevisiae were detected at low relative abundance (<2%).

There are remarkable differences in comparing the yTAM of two Brazilian milk kefirs [

26] with the Argentinian kefirs MKAA1 and MKAA2. In Brazilian kefirs, Pichiaceae predominated with 58.8% of the total against 1.23% in the Argentinian kefirs, Dipodascaceae showed 17.3% versus 72.9%, and Saccharomycetaceae was 11.8% versus 24.3%. The most frequent genera in Brazilian samples were Pichia and an unidentified genus of Pichiaceae at 18.3% and 40.5%,

Yarrowia at 17% and

Saccharomyces at 4%, while in MKAA1 and MKAA2,

Yarrowia was 72.2%,

Saccharomyces 1.73% and

Pichia only 0.46%.

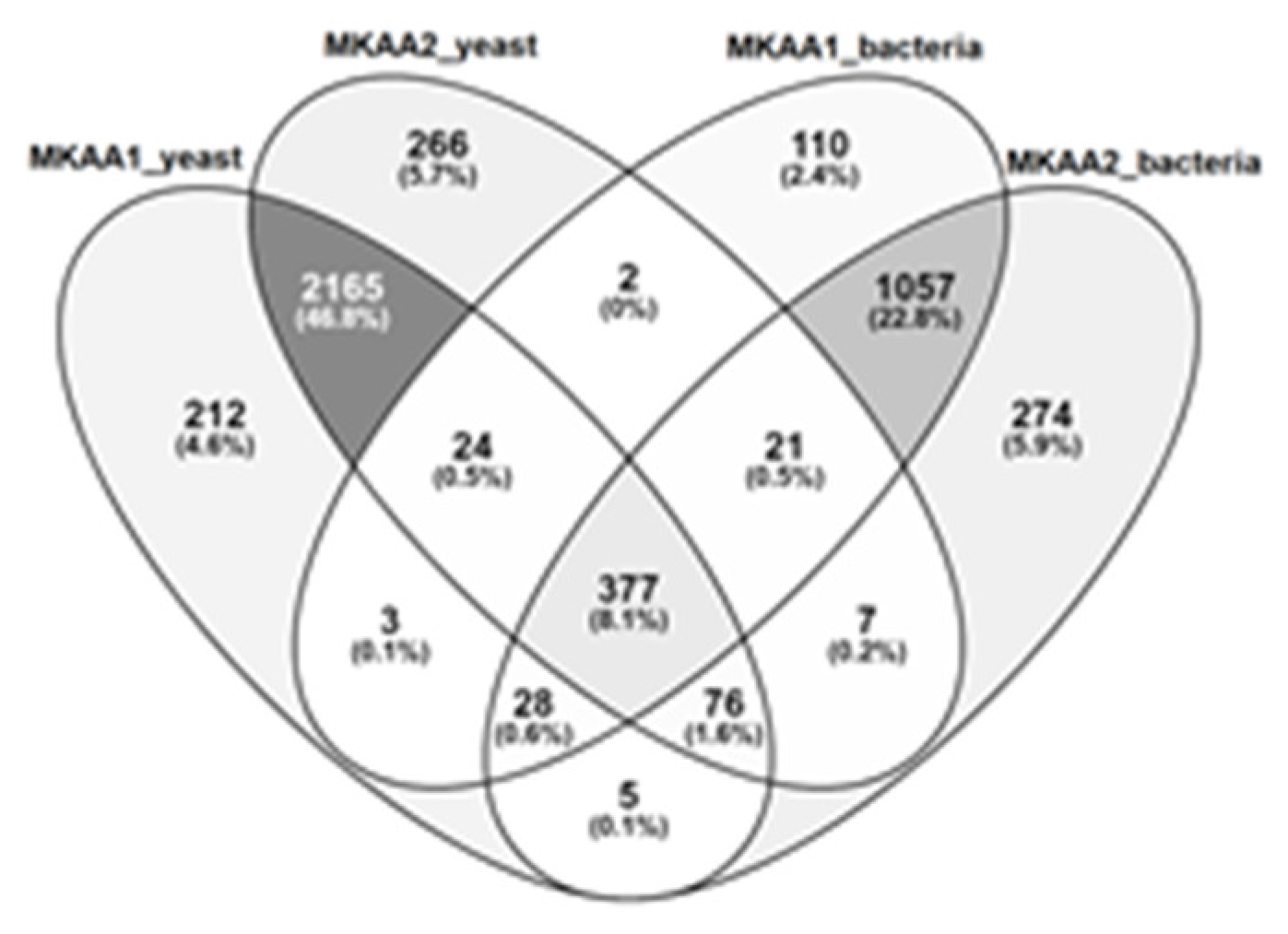

3.4. The Functional Profile of the Kefir Microbial Community of MKAA1 and MKAA2 Beverages

Regarding KEGG PATHWAY mapping of the KO functional orthologs, there were 1,622 and 1,845 assigned KO entries in MKAA1 and MKAA2 bacteria libraries, respectively, out of a total of 1,984 unique KO, and 2,890 and 2,938 assigned KO entries in yeast libraries, respectively, out of a total of 3,186 unique KO. Both kefirs shared 74.7% of bacteria KO and 82.9% of yeast KO (

Figure 3). KO found in only one kefir in the bacterial and fungal libraries were 7% and 7.8% in MKAA1 and 18.2% and 9.3% in MKAA2, respectively.

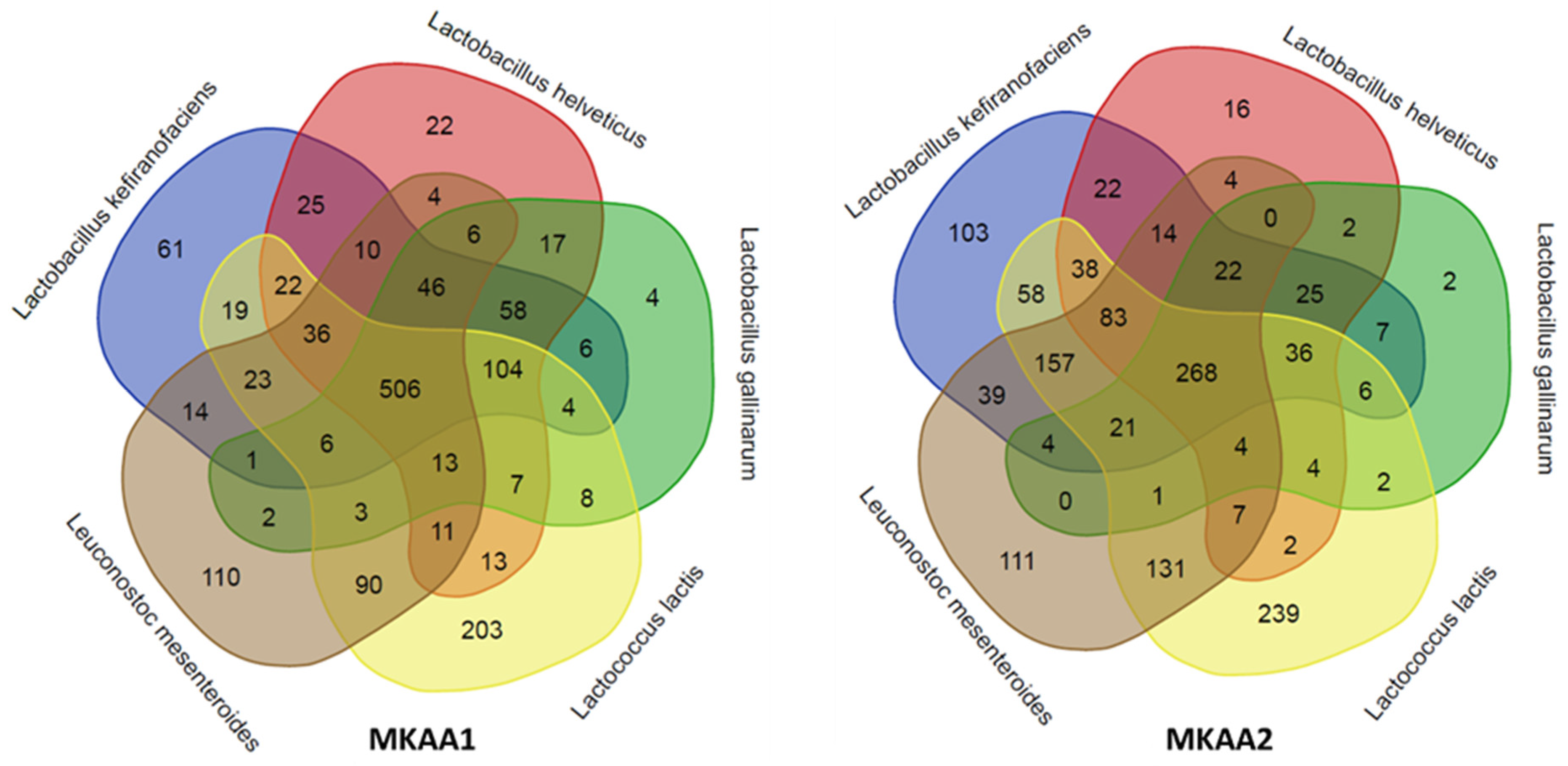

In a more in-depth analysis of the biological processes mapped in each kefir sample related to the five main LAB, we observed marked quantitative differences between the lactobacilli,

Lactococcus and

Leuconostoc. Although there were approximately the same number of KO in both samples (1,454 KO in MKAA1 and 1,428 KO in MKAA2, out of a total of 1,555 unique KO), the roles played by

L. helveticus and

L. gallinarum changed drastically. There was a significant decrease in the participation of these two Lactobacillus species and a consequent increase in

L. kefiranofaciens,

Lactococcus lactis and

Leuconostoc mesenteroides (

Table 4,

Figure 4).

The species pair

L. helveticus and

L. gallinarum participated with 934 KO in MKAA1 and then dropped to 590 KO in MKAA2 (37% less), with a subsequent increase from 520 to 838 KO absent in both. Of these KO in MKAA1 and MKAA2, 757 and 361 were shared with at least one other lactic acid bacteria: 506 and 268 KO with the other three lactic acid bacteria, 104 and 36 with

L. kefiranofaciens and

Lc. lactis, 58 and 25 with

L. kefiranofaciens only, 46 and 22 with

L. kefiranofaciens and

Leu. mesenteroides, 17 and 2 with each other, 13 and 4 with

Lc. lactis and

Leu. mesenteroides, 7 and 4 with

Lc. lactis only, and 6 and 0 with

Leu. mesenteroides only, respectively (

Figure 4).

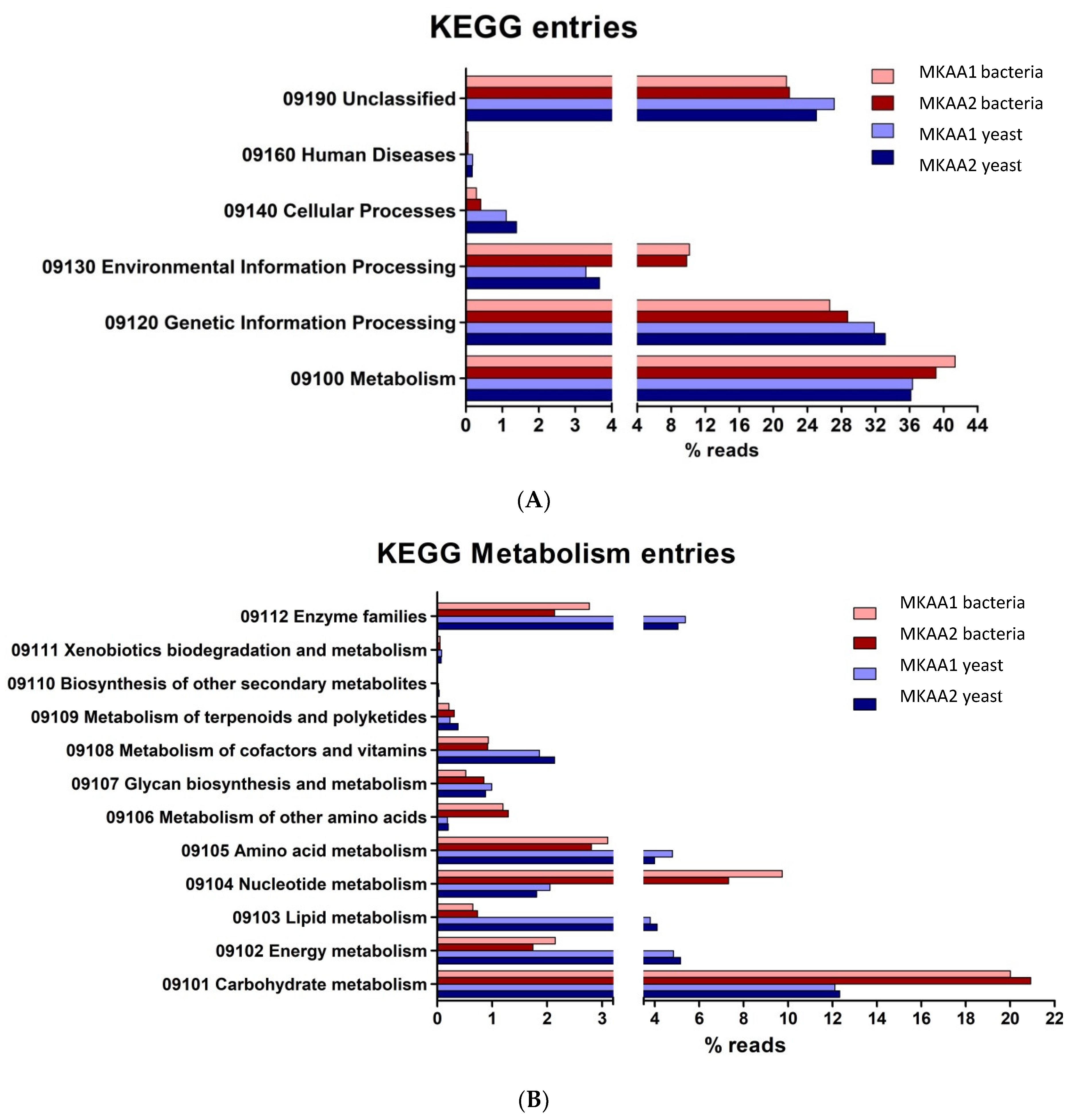

Concerning the six top categories for KEGG Pathway mapping (

Figure 5A), the relative abundances of reads associated with “Metabolism” and “Genetic Information Processing” in bacteria and yeast are majorities, and others 23 to 29% were categorised as “Unclassified”. Only slight differences were observed in the total KO between bacteria and yeasts. Concerning the second-level categories under the top category “Metabolism” (

Figure 5B), the relative abundance of transcripts associated with “Carbohydrate metabolism” was higher in bacteria than in yeasts (20% vs 12%), also observed with “Nucleotide metabolism” (9% vs 2%), and “Metabolism of other amino acids” (1.2% vs 0.2%). Otherwise, yeasts showed a higher relative abundance of transcripts associated with “Energy metabolism” (5% vs 2%), Lipid metabolism” (4% vs 0.8%), “Aminoacid metabolism” (4.5% vs 3%), “Metabolism of cofactors and vitamins” (2% vs 1%) and “Enzyme families” (6% vs 2.5%).

The changes observed in MKAA1 and MKAA2,

L. kefiranofaciens exclusive KO triplicated from MKAA1 to MKAA2, and the substantial decreases in total KO assigned to

L. helveticus and

L. gallinarum may explain some of the differences in the physicochemical aspect of both kefirs. Considering that

L kefiranofaciens subp

kefiranofaciens is described as kefiran producer there is no direct interpretation of the variations in rheological features of the beverages (

Figure 1b) indicating more compex relationship between these species.

L. helveticus strains are well known for their proteolytic ability [

41], which may provide amino acids and short peptides. However, this is not related to the improvement of

L. kefiranofaciens growth since adding proteases to milk did not affect its growth. Moreover,

L. kefiranofaciens positively affects the growth of

Leuconostoc mesenteroides because of its proteolytic activity [

8]. In this direction, the higher proportions of

L. kefiranofaciens in MKAA2 could explain the increment in

Leuconostoc observed compared to MKAA1.

bTAM analysis also demonstrated that in MKAA2,

Lactococcus and

Acetobacter were in higher proportion in MKAA2 in concordance to the higher content of lactic and acetic acid of this fermented milk as was previously reported [

11]. It was demonstrated that lactate and acetate, which are in higher proportion in MKAA2, may function as regulators of growth and metabolic activity of distinct species. Lactate stimulates the growth of

L. kefiranofaciens [

8], in concordance with what is observed in MKAA2. As higher kefiran production is obtained under pH control culture [

18,

42], the differences in the final pH of MKAA2 and higher organic acid content may lead to less viscosity. These results are in concordance with previous reports. Kefir prepared with different kefir grain/milk ratios also presented differences in viscosity since a lower kefir grain/milk ratio decreases the acidification rate, leading to higher viscosity. Otherwise, the differences in yeast active microbiome (

Figure 2, lower panel) could also affect polysaccharide synthesis by

L kefiranofaciens.

Considering that kefir MKAA2 has a diminished increment in grain biomass, this finding indicates that fewer matrix components are synthesized, and consequently, an increase in L. kefiranofaciens release from the grains is generated. Otherwise, the less viscosity of MKAA2 fermented product may indicate that the presence of L. kefiranofaciens is not enough for kefiran production, requiring other microorganisms that may produce unknown factors that could induce the production of this polysaccharide.

5. Conclusions

Kefir MKAA1 and MKAA2 showed differences in the amount of organic acids and rheological parameters that affect sensory attributes. When analysing the metatranscriptome of both fermented products, they have remarkably similar communities of microorganisms but with a significantly altered bacterial species distribution, mainly Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens, L. helveticus, L. gallinarum, and Lactococcus lactis. However, the main mapped functional processes are still similar in both beverages. Despite the lower viscosity in MKAA2, no direct correlation was observed with L kefiranofaciens’ relative abundance and activity, which is considered the main producer of kefiran. The results obtained in the present work suggest that changes in kefir active microbiota profile are enough to produce essential alterations in the physicochemical characteristics of the fermented product.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. The KO entries shared by or exclusive of MKAA1 and MKAA2 are listed in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2, and the protein identities of these unique KO are depicted in Supplemental Tables 3 and 4. Heatmap graphics illustrating the relative expression levels of KEGG modules for the paired kefir libraries and their associated communities are shown in Supplemental Figures S1A, B. Pearson’s correlation analysis investigated the relationship between the abundance of normalised annotated KO between MKAA1 and MKAA2 samples. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) is positive for all metabolism, genetic information processing, and environmental information processing pathways, with the strength of the association between the relative abundances very high (Supplemental Figures S2A-C), and the correlation coefficient is very significantly different from zero (P<0.001). The genes more expressed in each sample had their KO indicated in Figures S2A-C and are listed in Supplemental Table 5. MA plots generated to visualise the variances between differentially expressed genes in the RNA-seq libraries, indicating the most significant ones, are depicted in Supplemental Figures S3A-C.

Author Contributions

DLR, PCLS, CSM, and AAB performed the kefir propagation, RNA extraction, library creation, metatranscriptomics sequencing, and subsequent bioinformatics analyses. EN and ACN designed and coordinated the metatranscriptomic study. JRN, GRF contributed with experimental support in Brazil. AAB performed experimental analysis in Argentina. EN, ACN, AAB, GLG and AGA, contributed to conceptualization, writing, revision and discussion of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the CAPES Foundation (project n. 84/2014 – GPR/DRI/CAPES) in collaboration with the MINCyT, CONICET-University National of La Plata, Argentina cooperation proyect, and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) (process 2070.01.0008851/2019-41; APQ 02928-16). In Argentina experimental work was supported by CONICET (PIP2020-2786) and ANPCyT (PICT 2020-03239).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon request. The crude sequencing data were deposited at the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Library of Medicine (NLM), National Centre for Biotechnological Information (NCBI), Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database, BioProject accession PRJNA1084273.

Acknowledgments

AAB, GLG and AGA are members of Scientific Career of CONICET. We acknowledge the CEPAD-ICB-UFMG for providing the Sagarana HPC Cluster as a computational resource. The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by CONICET, ANPCyT, MINCyT- CAPES and FAPEMIG.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Leite, A.M.O.; Miguel, M.A.L.; Peixoto, R.S.; Rosado, A.S.; Silva, J.T.; Paschoalin, V.M.F. Microbiological, Technological and Therapeutic Properties of Kefir: A Natural Probiotic Beverage. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2013, 44, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garofalo, C.; Osimani, A.; Milanović, V.; Aquilanti, L.; De Filippis, F.; Stellato, G.; Di Mauro, S.; Turchetti, B.; Buzzini, P.; Ercolini, D.; et al. Bacteria and Yeast Microbiota in Milk Kefir Grains from Different Italian Regions. Food Microbiol. 2015, 49, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorda, F.A.; de Melo Pereira, G.V.; Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Rakshit, S.K.; Pagnoncelli, M.G.B.; Vandenberghe, L.P.D.S.; Soccol, C.R. Microbiological, Biochemical, and Functional Aspects of Sugary Kefir Fermentation - A Review. Food Microbiol. 2017, 66, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanirati, D.F.; Abatemarco, M.J.; Sandes, S.H. de C.; Nicoli, J.R.; Nunes, Á.C.; Neumann, E. Selection of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Brazilian Kefir Grains for Potential Use as Starter or Probiotic Cultures. Anaerobe 2015, 32, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengoa, A.A.; Iraporda, C.; Garrote, G.L.; Abraham, A.G. Kefir Micro-Organisms: Their Role in Grain Assembly and Health Properties of Fermented Milk. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrote, G.L.; Abraham, A.G.; De Antoni, G.L. Microbial Interactions in Kefir: A Natural Probiotic Drink; 2010; ISBN 9780813815831.

- Londero, A.; Hamet, M.F.; De Antoni, G.L.; Garrote, G.L.; Abraham, A.G. Kefir Grains as a Starter for Whey Fermentation at Different Temperatures: Chemical and Microbiological Characterisation. J. Dairy Res. 2012, 79, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasche, S.; Kim, Y.; Mars, R.A.T.; Machado, D.; Maansson, M.; Kafkia, E.; Milanese, A.; Zeller, G.; Teusink, B.; Nielsen, J.; et al. Metabolic Cooperation and Spatiotemporal Niche Partitioning in a Kefir Microbial Community. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, A.J.; O’Sullivan, O.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P.; Cotter, P.D. Sequencing-Based Analysis of the Bacterial and Fungal Composition of Kefir Grains and Milks from Multiple Sources. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Orozco, B.D.; García-Cano, I.; Escobar-Zepeda, A.; Jiménez-Flores, R.; Álvarez, V.B. Metagenomic Analysis and Antibacterial Activity of Kefir Microorganisms. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, 2933–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, A.M.; Crispie, F.; Kilcawley, K.; O’Sullivan, O.; O’Sullivan, M.G.; Claesson, M.J.; Cotter, P.D. Microbial Succession and Flavor Production in the Fermented Dairy Beverage Kefir. mSystems 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanoeva, C.; Rios, D.; Alvarenga, R.; Acurcio, L.; Sandes, S.; Nunes, A.; Nicoli, J.; Neumann, E. Functionally Active Microbiome and Physicochemical Properties of Milk and Sugary Water Kefir from Brazil. Austin Food Sci. 2021, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, C.J.; González-Orozco, B.D.; Jiménez-Flores, R. Evaluation of Kefir Grain Microbiota, Grain Viability, and Kefir Bioactivity from Fermenting Dairy Processing By-Products. J. Dairy Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M’hir, S.; Ayed, L.; De Pasquale, I.; Fanizza, E.; Tlais, A.Z.A.; Comparelli, R.; Verni, M.; Latronico, R.; Gobbetti, M.; Di Cagno, R.; et al. Comparison of Milk Kefirs Obtained from Cow’s, Ewe’s and Goat’s Milk: Antioxidant Role of Microbial-Derived Exopolysaccharides. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satir, G.; Guzel-Seydim, Z.B. How Kefir Fermentation Can Affect Product Composition? Small Rumin. Res. 2016, 134, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yegin, Z.; Yurt, M.N.Z.; Tasbasi, B.B.; Acar, E.E.; Altunbas, O.; Ucak, S.; Ozalp, V.C.; Sudagidan, M. Determination of Bacterial Community Structure of Turkish Kefir Beverages via Metagenomic Approach. Int. Dairy J. 2022, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, L.H.; Coakley, M.; Walsh, A.M.; Crispie, F.; O’Toole, P.W.; Cotter, P.D. Analysis of the Milk Kefir Pan-Metagenome Reveals Four Community Types, Core Species, and Associated Metabolic Pathways. iScience 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentry, B.; Cazón, P.; O’Brien, K. A Comprehensive Review of the Production, Beneficial Properties, and Applications of Kefiran, the Kefir Grain Exopolysaccharide. Int. Dairy J. 2023, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonelli, N.; Gagliarini, N.; Medrano, M.; Piermaria, J.; Abraham, A. Kefiran. In Polysaccharides of Microbial Origin; Oliveira, J., Radhouani, H., Reis, R., Eds.; Springer Nature, 2022; pp. 1–12 ISBN 9783662467640.

- Rimada, P.S.; Abraham, A.G. Polysaccharide Production by Kefir Grains during Whey Fermentation. J. Dairy Res. 2001, 68, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimada, P.S.; Abraham, A.G. Comparative Study of Different Methodologies to Determine the Exopolysaccharide Produced by Kefir Grains in Milk and Whey. Lait 2003, 83, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrote, G.L.; Abraham, A.G.; De Antoni, G.L. Characteristics of Kefir Prepared with Different Grain:Milk Ratios. J. Dairy Res. 1998, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourrie, B.C.T.; Ju, T.; Fouhse, J.M.; Forgie, A.J.; Sergi, C.; Cotter, P.D.; Willing, B.P. Kefir Microbial Composition Is a Deciding Factor in the Physiological Impact of Kefir in a Mouse Model of Obesity. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 125, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: A Revolutionary Tool for Transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashiardes, S.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Elinav, E. Use of Metatranscriptomics in Microbiome Research. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2016, 10, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios, D.L.; da Silva, P.C.L.; Moura, C.S.S.; Villanoeva, C.N.B.C.; da Rocha Fernandes, G.; Bengoa, A.A.; Garrote, G.L.; Abraham, A.G.; Nicoli, J.R.; Neumann, E.; et al. Comparative Metatranscriptome Analysis of Brazilian Milk and Water Kefir Beverages. Int. Microbiol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasapolli, R.; Schütte, K.; Schulz, C.; Vital, M.; Schomburg, D.; Pieper, D.H.; Vilchez-Vargas, R.; Malfertheiner, P. Analysis of Transcriptionally Active Bacteria Throughout the Gastrointestinal Tract of Healthy Individuals. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 1081–1092.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamet, M.F.; Piermaria, J.A.; Abraham, A.G. Selection of EPS-Producing Lactobacillus Strains Isolated from Kefir Grains and Rheological Characterization of the Fermented Milks. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ye, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y. High Speed BLASTN: An Accelerated MegaBLAST Search Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 7762–7768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huson, D.H.; Tappu, R.; Bazinet, A.L.; Xie, C.; Cummings, M.P.; Nieselt, K.; Williams, R. Fast and Simple Protein-Alignment-Guided Assembly of Orthologous Gene Families from Microbiome Sequencing Reads. Microbiome 2017, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q.; et al. Full-Length Transcriptome Assembly from RNA-Seq Data without a Reference Genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Lomsadze, A.; Borodovsky, M. Identification of Protein Coding Regions in RNA Transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Leung, H.C.-M.; Luo, R.; Wong, C.-K.; Ting, H.-F.; Lam, T.-W. AC-DIAMOND v1: Accelerating Large-Scale DNA-Protein Alignment. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3744–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, G.R.; Barbosa, D.V.C.; Prosdocimi, F.; Pena, I.A.; Santana-Santos, L.; Coelho Junior, O.; Barbosa-Silva, A.; Velloso, H.M.; Mudado, M.A.; Natale, D.A.; et al. A Procedure to Recruit Members to Enlarge Protein Family Databases--the Building of UECOG (UniRef-Enriched COG Database) as a Model. Genet. Mol. Res. 2008, 7, 910–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast Universal RNA-Seq Aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, J.Z.B.; Khang, T.F.; Tammi, M.T. CORNAS: Coverage-Dependent RNA-Seq Analysis of Gene Expression Data without Biological Replicates. BMC Bioinformatics 2017, 18, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heberle, H.; Meirelles, G.V.; da Silva, F.R.; Telles, G.P.; Minghim, R. InteractiVenn: A Web-Based Tool for the Analysis of Sets through Venn Diagrams. BMC Bioinformatics 2015, 16, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimada, P.S.; Abraham, A.G. Kefiran Improves Rheological Properties of Glucono-δ-Lactone Induced Skim Milk Gels. Int. Dairy J. 2006, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvetti, E.; O’Toole, P.W. The Genomic Basis of Lactobacilli as Health-Promoting Organisms. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O’toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. A Taxonomic Note on the Genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 Novel Genera, Emended Description of the Genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and Union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valasaki, K.; Staikou, A.; Theodorou, L.G.; Charamopoulou, V.; Zacharaki, P.; Papamichael, E.M. Purification and Kinetics of Two Novel Thermophilic Extracellular Proteases from Lactobacillus Helveticus, from Kefir with Possible Biotechnological Interest. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 5804–5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheirsilp, B.; Suksawang, S.; Yeesang, J.; Boonsawang, P. Co-Production of Functional Exopolysaccharides and Lactic Acid by Lactobacillus Kefiranofaciens Originated from Fermented Milk, Kefir. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).