Submitted:

12 June 2024

Posted:

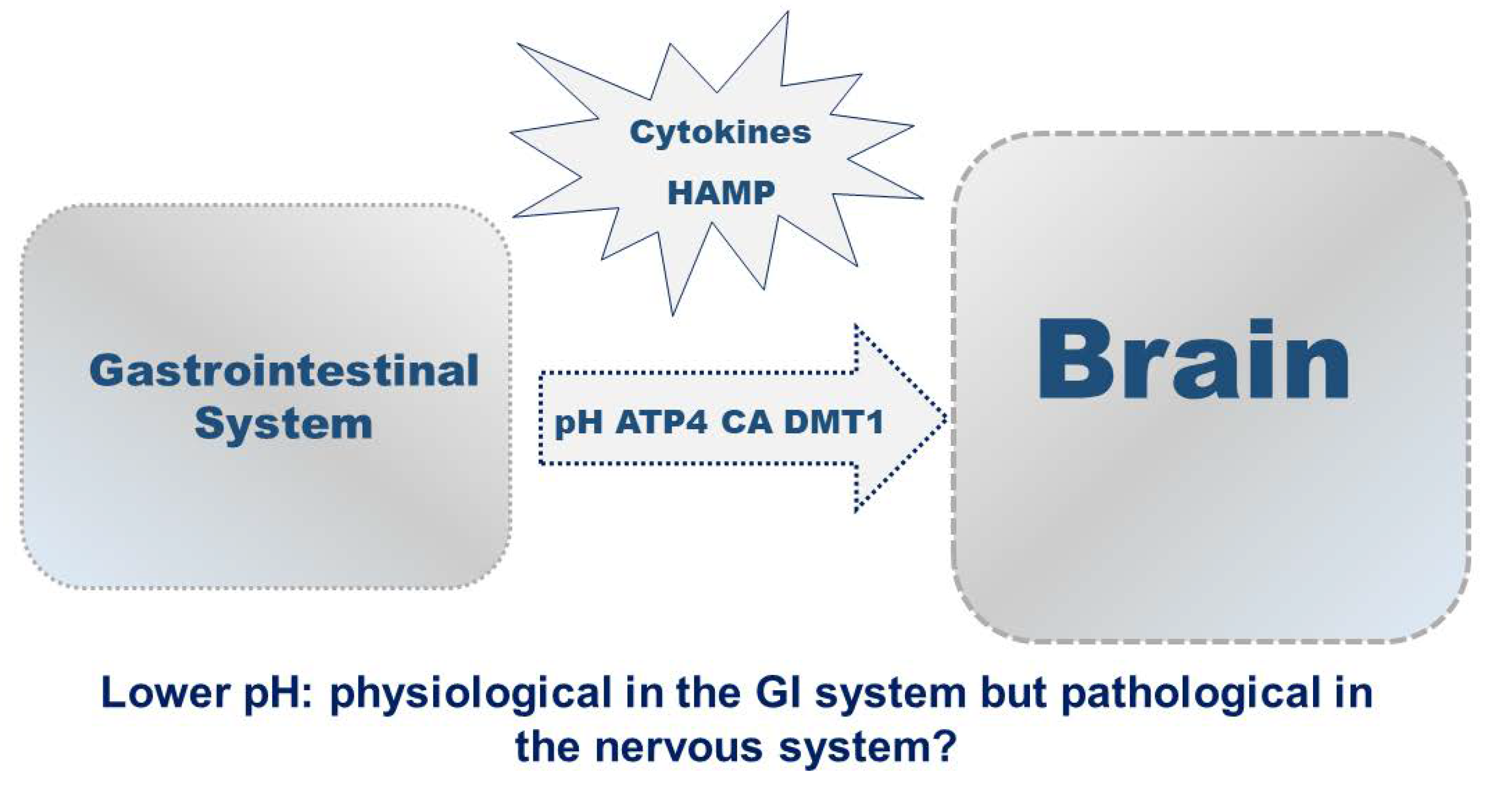

13 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

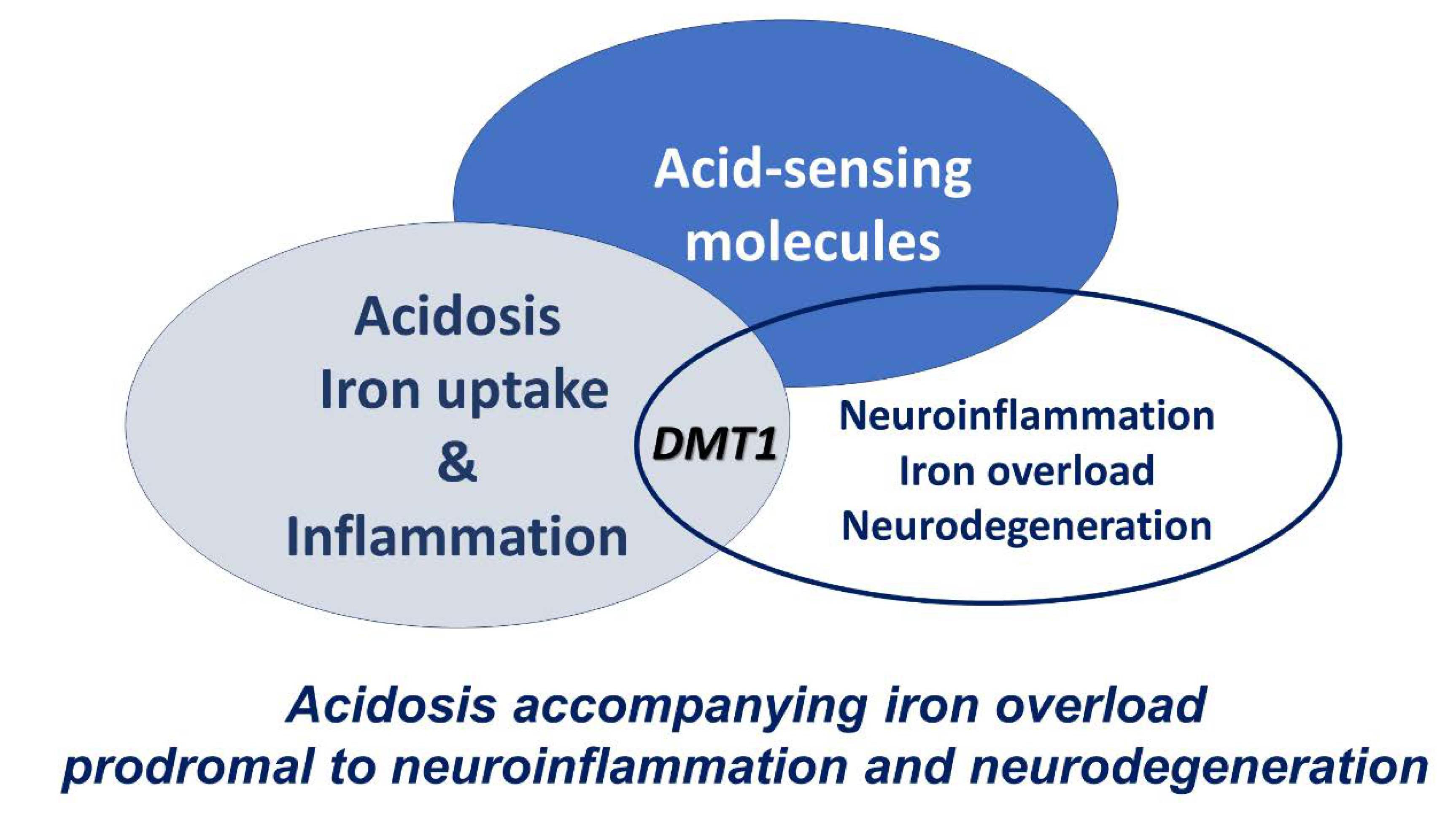

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Acid-Sensing Molecules in Acidosis and Pathology

3. Acidosis and Iron Uptake by DMT1

4. Acidosis-Dependent Inflammation and Iron Homeostasis

5. Acidosis-Dependent Neuroinflammation and Iron Overload

6. Iron Chelation and Transport Strategies

7. Conclusions

References

- Gunshin H, Mackenzie B, Berger UV, Gunshin Y, Romero MF, Boron WF, Nussberger S, Gollan JL, and Hediger MA. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter. Nature 1997, 388, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming MD, Trenor CC, Su MA, Foernzler D, Beier DR, Dietrich WF, and Andrews NC Microcytic anaemia mice have a mutation in Nramp2, a candidate iron transporter gene. Nat Genet 1997, 16, 383–386. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrick MD, Dolan KG, Horbinski C, Ghio AJ, Higgins D, Porubcin M, Moore EG, Hainsworth LN, Umbreit JN, Conrad ME, Feng L, Lis A, Roth JA, Singleton S, Garrick LM. DMT1: a mammalian transporter for multiple metals. Biometals. 2003, 16, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, T. Systemic iron homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 1721–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming MD, Romano MA, Su MA, Garrick LM, Garrick MD, Andrews NC. Nramp2 is mutated in the anemic Belgrade (b) rat: evidence of a role for Nramp2 in endosomal iron transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998, 95, 1148–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philpott CC, Ryu MS. Special delivery: distributing iron in the cytosol of mammalian cells. Front Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 173. [Google Scholar]

- Yanatori I, Kishi F. DMT1 and iron transport. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2019, 133, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, Vaughn MB, Donovan A, McVey Ward D, Ganz T, Kaplan J. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science 2004, 306, 2090–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemeth E, Ganz T. Hepcidin-Ferroportin Interaction Controls Systemic Iron Homeostasis Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 6493.

- Knutson, MD. J Iron transport proteins: Gateways of cellular and systemic iron homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2017, 292, 12735–12743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie B and Garrick MD Iron imports. II. Iron uptake at the apical membrane in the intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2005, 289, G981–G986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu LJ, Leenders AG, Cooperman S, Meyron-Holtz E, Smith S, Land W, Tsai RY, Berger UV, Sheng ZH, Rouault TA. Expression of the iron transporter ferroportin in synaptic vesicles and the blood-brain barrier. Brain Res 2004, 1001, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urrutia, P. , Aguirre, P., Esparza, A., Tapia, V., Mena, N. P., Arredondo, M., et al. Inflammation alters the expression of DMT1, FPN1 and hepcidin, and it causes iron accumulation in central nervous system cells. J. Neurochem. 2013, 126, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, L. H. , Yan, C. Z., Zheng, B. J., Ci, Y. Z., Chang, S. Y., Yu, P., et al. Astrocyte hepcidin is a key factor in LPS-induced neuronal apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrick MD, Dolan KG. An expression system for a transporter of iron and other metals. In Ultrastructure and Molecular Biology stet for oxidants and Antioxidants, Methods in Molecular Biology; D. Armstrong ed; Humana press: Totawa NJ, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Garrick MD, Kuo HC, Vargas F, Singleton S, Zhao L, Smith JJ, Paradkar P, Roth JA, Garrick LM. Comparison of mammalian cell lines expressing distinct isoforms of divalent metal transporter 1 in a tetracycline-regulated fashion. Biochem J. 2006, 398, 539–546.

- Arredondo M, Mendiburo MJ, Flores S, Singleton ST, Garrick MD. Mouse divalent metal transporter 1 is a copper transporter in HEK293 cells. Biometals 2014, 27, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrick MD, Singleton ST, Vargas F, Kuo HC, Zhao L, Knöpfel M, Davidson T, Costa M, Paradkar P, Roth JA, Garrick LM. DMT1: which metals does it transport? Biol Res 2006, 39, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- et al. Effect of DMT1 knockdown on iron, cadmium, and lead uptake in Caco-2 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2003, 284, C44–C50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevo Y, Nelson N. The NRAMP family of metal-ion transporters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006, 1763, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez MT, Gaete V, Watkins JA, Glass J. Mobilization of iron from endocytic vesicles. The effects of acidification and reduction. J Biol Chem 1990, 265, 6688–6692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins JA, Nunez MT, Gaete V, Alvarez O, Glass J. Kinetics of iron passage through subcellular compartments of rabbit reticulocytes. J Membr Biol 1991, 119, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohgami RS, Campagna DR, Greer EL, Antiochos B, McDonald A, Chen J, Sharp JJ, Fujiwara Y, Barker JE, Fleming MD. Identification of a ferrireductase required for efficient transferrin-dependent iron uptake in erythroid cells. Nat Genet. 2005, 37, 1264–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sendamarai AK, Ohgami RS, Fleming MD, Lawrence CM. Structure of the membrane proximal oxidoreductase domain of human Steap3, the dominant ferrireductase of the erythroid transferrin cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008, 105, 7410–7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng YR, Jiang BY, Chen CC. Acid-sensing ion channels: dual function proteins for chemo-sensing and mechano-sensing J Biomed Sci 2018, 25, 46.

- Mazzocchi N, De Ceglia R, Mazza D, Forti L, Muzio L, Menegon A. Fluorescence-Based Automated Screening Assay for the Study of the pH-Sensitive Channel ASIC1a. J Biomol Screen 2016, 21, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mango D, Nisticò R. Neurodegenerative Disease: What Potential Therapeutic Role of Acid-Sensing Ion Channels? Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15, 730641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiacchiaretta, M. , Latifi, S., Bramini, M., Fadda, M., Fassio, A., Benfenati, F., et al. Neuronal hyperactivity causes Na +/H + exchanger-induced extracellular acidification at active synapses. J. Cell Sci, 1435. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong ZG, Xu TL. The role of ASICS in cerebral ischemia. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Membr Transp Signal 2012, 1, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Ramírez O, González-Garrido A. The role of acid sensing ion channels in the cardiovascular function. Front Physiol. 2023, 14, 1194948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redd MA, Scheuer SE, Saez NJ, Yoshikawa Y, Chiu HS, Gao L, Hicks M, Villanueva JE, Joshi Y, Chow CY, Cuellar-Partida G, Peart JN, See Hoe LE, Chen X, Sun Y, Suen JY, Hatch RJ, Rollo B, Xia D, Alzubaidi MAH, Maljevic S, Quaife-Ryan GA, Hudson JE, Porrello ER, White MY, Cordwell SJ, Fraser JF, Petrou S, Reichelt ME, Thomas WG, King GF, Macdonald PS, Palpant NJ. Therapeutic Inhibition of Acid-Sensing Ion Channel 1a Recovers Heart Function After Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Circulation. 2021, 144, 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher R, Ducrot N, Lefebvre T, Zineeddine S, Ausseil J, Puy H, Karim Z. Crosstalk between Acidosis and Iron Metabolism: Data from In Vivo Studies. Metabolites 2022, 12, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker HM, Deitmer JW. Proton Transport in Cancer Cells: the role of Carbonic Anhydrases. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemon N, Canepa E, Ilies MA, Fossati S. Carbonic Anhydrases as Potential Targets Against Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction in Alzheimer's Disease and Stroke. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13, 772278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poggetti V, Salerno S, Baglini E, Barresi E, Da Settimo F, Taliani S. Carbonic Anhydrase Activators for Neurodegeneration: An Overview. Molecules 2022, 27, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryder C, McColl K, Zhong F, Distelhorst CW. Acidosis promotes Bcl-2 family-mediated evasion of apoptosis: involvement of acid-sensing G protein-coupled receptor Gpr65 signaling to Mek/Erk. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 27863–27875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarnico I, Lanzillotta A, Benarese M, Alghis M, Baiguera C, Battistin L, Spano PF, Pizzi M. NF-kappaB dimers in the regulation of neuronal survival. Int Rev Neurobiol 2009, 85, 351–362. [Google Scholar]

- et al. 1B/(-)IRE DMT1 expression during brain ischemia contributes to cell death mediated by NF-κB/RelA acetylation at Lys310. PLoS One 2012, 7, e38019. [Google Scholar]

- Ordway B, Gillies RJ, Damaghi M. Extracellular Acidification Induces Lysosomal Dysregulation Cells 2021, 10, 1188.

- Wilson JL, Allison Gregory A, Kurian MA, Bushlin I, Mochel F, Emrick L, Adang L. BPAN Guideline Contributing Author roup. Hogarth P, Hayflick SJ. Consensus clinical management guideline for beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2021, 63, 1402–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingrassia R, Memo M, Garavaglia B. Ferrous Iron Up-regulation in Fibroblasts of Patients with Beta Propeller Protein-Associated Neurodegeneration (BPAN). Front Genet. 2017, 8, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Bao Y, Li M, Zhang W, Chen C. The role of ferroptosis and its mechanism in ischemic stroke. Exp Neurol. 2024, 372, 114630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Zhang X, Xiong X, Zhu H, Chen R, Zhang S, Chen G, Jian Z. Nrf2 Regulates Oxidative Stress and Its Role in Cerebral Ischemic Stroke. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022, 11, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 44. Oates PS, Morgan EH. 1996 Defective iron uptake by the duodenum of Belgrade rats fed diets of different iron contents. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol.

- Garrick M, Scott D, Walpole S, Finkelstein E, Whitbred J, Chopra S, Trivikram L, Mayes D, Rhodes D, Cabbagestalk K, Oklu R, Sadiq A, Mascia B, Hoke J, Garrick L. Iron supplementation moderates but does not cure the Belgrade anemia. BioMetals 1997, 10, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards JA, Hoke JE. Defect of intestinal mucosal iron uptake in mice with hereditary microcytic anemia. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1972, 141, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canonne-Hergaux F, Fleming MD, Levy JE, Gauthier S, Ralph T, Picard V, Andrews NC, Gros P. The Nramp2/DMT1 iron transporter is induced in the duodenum of microcytic anemia mk mice but is not properly targeted to the intestinal brush border. Blood. 2000, 96, 3964–3970. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad ME, Umbreit JN, Moore EG, Hainsworth LN, Porubcin M, Simovich MJ, Nakada MT, Dolan K, Garrick MD. Separate pathways for cellular uptake of ferric and ferrous iron. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000, 279, G767–G774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKie AT, Barrow D, Latunde-Dada GO, Rolfs A, Sager G, Mudaly E, Mudaly M, Richardson C, Barlow D, Bomford A, Peters TJ, Raja KB, Shirali S, Hediger MA, Farzaneh F, Simpson RJ. An iron-regulated ferric reductase associated with the absorption of dietary iron. Science. 2001, 291, 1755–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 50. Hubert N, Hentze MW..Previously uncharacterized isoforms of divalent metal transporter (DMT)-1: implications for regulation and cellular function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1235.

- Paradkar PN, Roth JA. Nitric oxide transcriptionally down-regulates specific isoforms of divalent metal transporter (DMT1) via NF-kappaB. J Neurochem. 2006, 96, 1768–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shawki, A. , Anthony, S. R., Nose, Y., Engevik, M. A., Niespodzany, E. J., Barrientos, T., Öhrvik, H., Worrell, R. T., Thiele, D. J., and Mackenzie, B. Intestinal DMT1 is critical for iron absorption in the mouse but is not required for the absorption of copper or manganese. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2015, 309, G635–G647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wolff NA, Ghio AJ, Garrick LM, Garrick MD, Zhao L, Fenton RA, Thévenod F. Evidence for mitochondrial localization of divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1). FASEB J 2014, 28, 2134–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das A, Nag S, Mason AB, Barroso MM. Endosome-mitochondria interactions are modulated by iron release from transferrin. J Cell Biol. 2016, 214, 831–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheftel AD, Zhang AS, Brown C, Shirihai OS, Ponka P. Direct interorganellar transfer of iron from endosome to mitochondrion. Blood. 2007, 110, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff NA, Garrick MD, Zhao L, Garrick LM, Ghio AJ, Thévenod F. A role for divalent metal transporter (DMT1) in mitochondrial uptake of iron and manganese. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrick MD, Gniecko K, Liu Y, Cohan DS, Garrick LM. Transferrin and the transferrin cycle in Belgrade rat reticulocytes. J Biol Chem. 1993, 268, 14867–14874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang T, Huang H, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Larsen MR. Divalent Metal Transporter 1 Knock-Down Modulates IL-1β Mediated Pancreatic Beta-Cell Pro-Apoptotic Signaling Pathways through the Autophagic Machinery. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 8013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldini N, Avnet S. The Effects of Systemic and Local Acidosis on Insulin Resistance and Signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2018, 20, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae BJ, Lee KS, Hwang I, Yu JW. Extracellular Acidification Augments NLRP3-Mediated Inflammasome Signaling in Macrophages. Immune Netw 2023, 23, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg Z, Hu Z, Sternberg D, Waseh S, Quinn JF, Wild K, Jeffrey K, Zhao L, Garrick M. Serum Hepcidin Levels, Iron Dyshomeostasis and Cognitive Loss in Alzheimer's Disease. Aging Dis. 2017, 8, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson E, Schultz N, Saito T, Saido TC, Blennow K, Gouras GK, Zetterberg H, Hansson O. Cerebral Abeta deposition precedes reduced cerebrospinal fluid and serum Abeta42/Abeta40 ratios in the App(NL-F/NL-F) knock-in mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2023, 15, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellazzi M, Patergnani S, Donadio M, Giorgi C, Bonora M, Bosi C, Brombo G, Pugliatti M, Seripa D, Zuliani G, Pinton P. Autophagy and mitophagy biomarkers are reduced in sera of patients with Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 20009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng J, Liao Y, Dong Y, Hu H, Yang N, Kong X, Li S, Li X, Guo J, Qin L, Yu J, Ma C, Li J, Li M, Tang B, Yuan Z. Microglial autophagy defect causes parkinson disease-like symptoms by accelerating inflammasome activation in mice. Autophagy 2020, 16, 2193–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiguera C, Alghisi M, Pinna A, Bellucci A, De Luca MA, Frau L, Morelli M, Ingrassia R, Benarese M, Porrini V, Pellitteri M, Bertini G, Fabene PF, Sigala S, Spillantini MG, Liou HC, Spano PF, Pizzi M. Late-onset Parkinsonism in NFκB/c-Rel-deficient mice. Brain 2012, 135, 2750–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar J, Mena N, Hunot S, Prigent A, Alvarez-Fischer D, Arredondo M, Duyckaerts C, Sazdovitch V, Zhao L, Garrick LM, Nuñez MT, Garrick MD, Raisman-Vozari R, Hirsch EC. Divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) contributes to neurodegeneration in animal models of Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008, 105, 18578–18583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth JA, Singleton S, Feng J, Garrick M, Paradkar PN. Parkin regulates metal transport via proteasomal degradation of the 1B isoforms of divalent metal transporter 1. J Neurochem. 2010, 113, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingrassia R, Garavaglia B, Memo M. DMT1 Expression and Iron Levels at the Crossroads Between Aging and Neurodegeneration. Front Neurosci. 2019, 13, 575.

- Pelizzoni I, Zacchetti D, Campanella A, Grohovaz F, Codazzi F. Iron uptake in quiescent and inflammation-activated astrocytes: a potentially neuroprotective control of iron burden. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013. 1832, 1326–1333.

- Salami A, Papenberg G, Sitnikov R, Laukka EJ, Persson J, Kalpouzos G. Elevated neuroinflammation contributes to the deleterious impact of iron overload on brain function in aging. Neuroimage 2021, 230, 117792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang E, Ong WY, Go ML, Connor JR. Upregulation of iron regulatory proteins and divalent metal transporter-1 isoforms in the rat hippocampus after kainate induced neuronal injury. Exp Brain Res. 2006, 170, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, EC. Iron transport in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009, 2009 15 Suppl 3, S209–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo C, Ardissone A, Freri E, Gasperini S, Moscatelli M, Zorzi G, Panteghini C, Castellotti B, Garavaglia B, Nardocci N, Chiapparini L. Substantia Nigra Swelling and Dentate Nucleus T2 Hyperintensity May Be Early Magnetic Resonance Imaging Signs of β-Propeller Protein-Associated Neurodegeneration Mov Disord Clin Pract 2018, 6, 51–56.

- Manti F, Panteghini C, Garavaglia B, Leuzzi V. Neurodevelopmental Disorder and Late-Onset Degenerative Parkinsonism in a Patient with a WDR45 Defect. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2021, 9, 110–112. [Google Scholar]

- et al. Pallidal neuronal apolipoprotein E in pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration recapitulates ischemic injury to the globus pallidus. Mol Genet Metab 2015, 116, 289–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutts A, Chowdhury S, Ratkay LG, Eyers M, Young C, Namdari R, Cadieux JA, Chahal N, Grimwood M, Zhang Z, Lin S, Tietjen I, Xie Z, Robinette L, Sojo L, Waldbrook M, Hayden M, Mansour T, Pimstone S, Goldberg YP, Webb M, Cohen CJ. Potent, Gut-Restricted Inhibitors of Divalent Metal Transporter 1: Preclinical Efficacy against Iron Overload and Safety Evaluation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2023, 386, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrick, MD. Managing Iron Overload: A Gut Check. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2023, 386, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillo AS, SantaMaria AM, Kafina MD, Cioffi AG, Huston NC, Han M, Seo YA, Yien YY, Nardone C, Menon AV, Fan J, Svoboda DC, Anderson JB, Hong JD, Nicolau BG, Subedi K, Gewirth AA, Wessling-Resnick M, Kim J, Paw BH, Burke MD. Restored iron transport by a small molecule promotes absorption and hemoglobinization in animals. Science 2017, 356, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrick MD, Garrick LM, Zhao L, Collins JF, Soukup J, Ghio AJ. A direct comparison of divalent metal-ion transporter (DMT1) and hinokitiol, a potential small molecule replacement. Biometals 2019, 32, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraglia KA, Chorghade RS, Kim BR, Tang XX, Shah VS, Grillo AS, Daniels PN, Cioffi AG, Karp PH, Zhu L, Welsh MJ, Burke MD. Small-molecule ion channels increase host defences in cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. Nature 2019, 567, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devos D, Labreuche J, Rascol O, Corvol JC, Duhamel A, Guyon Delannoy P, Poewe W, Compta Y, Pavese N, Růžička E, Dušek P, Post B, Bloem BR, Berg D, Maetzler W, Otto M, Habert MO, Lehericy S, Ferreira J, Dodel R, Tranchant C, Eusebio A, Thobois S, Marques AR, Meissner WG, Ory-Magne F, Walter U, de Bie RMA, Gago M, Vilas D, Kulisevsky J, Januario C, Coelho MVS, Behnke S, Worth P, Seppi K, Ouk T, Potey C, Leclercq C, Viard R, Kuchcinski G, Lopes R, Pruvo JP, Pigny P, Garçon G, Simonin O, Carpentier J, Rolland AS, Nyholm D, Scherfler C, Mangin JF, Chupin M, Bordet R, Dexter DT, Fradette C, Spino M, Tricta F, Ayton S, Bush AI, Devedjian JC, Duce JA, Cabantchik I, Defebvre L, Deplanque D, Moreau C; FAIRPARK-II Study Group. Trial of Deferiprone in Parkinson's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2022, 387, 2045–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetli HA, Buckett PD, Wessling-Resnick M. Small-molecule screening identifies the selanazal drug ebselen as a potent inhibitor of DMT1-mediated iron uptake. Chem Biol. 2006, 13, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, A. , Yoshimoto, T., Kikuchi, H., Sano, K., Saito, I., Yamaguchi, T., and Yasuhara, H. Ebselen in acute middle cerebral artery occlusion: a placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Cerebrovasc. Dis.

- Yamaguchi, T. , Sano, K., Takakura, K., Saito, I., Shinohara,Y, Asano, T., and Yasuhara, H. Ebselen in acute ischemic stroke: a placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Stroke 1998, 29, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller A, Cadenas E, Graf P, Sies H. A novel biologically active seleno-organic compound--I. Glutathione peroxidase-like activity in vitro and antioxidant capacity of PZ 51 (Ebselen). Biochem Pharmacol 1984, 33, 3235–3239. [Google Scholar]

- Paernham MJ, Sies H. The early research and development of ebselen. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013, 86, 1248–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnerup J, Sutherland BA, M Buchan AM, Kleinschnitz C. Neuroprotection for stroke: current status and future perspectives. Int J Mol Sci 2012, 13, 11753–11772.

- Lapchak PA, Zivin JA. Ebselen, a seleno-organic antioxidant, is neuroprotective after embolic strokes in rabbits: synergism with low-dose tissue plasminogen activator. Stroke 2003, 34, 2013–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klann IP, Martini F, Gonçalves Rosa S, Nogueira CW. Ebselen reversed peripheral oxidative stress induced by a mouse model of sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Mol Biol Rep 2020, 47, 2205–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazaiean M, Aliasgharian A, Karami H, Darvishi-Khezri H. Ebselen: A promising therapy protecting cardiomyocytes from excess iron in iron-overloaded thalassemia patients. Open Med (Wars) 2023, 18, 20230733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukem S, Sayoh I, Maungchanburi S, Thongbuakaew T. Ebselen, Iron Uptake Inhibitor, Alleviates Iron Overload-Induced Senescence-Like Neuronal Cells SH-SY5Y via Suppressing the mTORC1 Signaling Pathway. Adv Pharmacol Pharm Sci 2023, 2023, 6641347. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhang M, Flores SRL, Woloshun RR, Yang C, Yin L, Xiang P, Xu X, Garrick MD, Vidyasagar S, Merlin D and Collins JF Oral gavage of ginger nanoparticle-derived lipid vectors carrying Dmt1 siRNA blunts iron loading in murine hereditary hemochromatosis. Mol Ther 2019, 27, 493–506. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Zhang M, Woloshun RR, Yu Y, Lee JK, Flores SRL, Merlin D, and Collins JF. Oral administration of ginger-derived lipid nanoparticles and Dmt1 siRNA potentiates the effect of dietary iron restriction and mitigates pre-existing iron overload in Hamp KO mice. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi S, Volonté MA. Iron chelation in early Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol 2023, 22, 290–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulli I, Dettori I, Coppi E, Cherchi F, Venturini M, Di Cesare Mannelli L, Ghelardini C, Nocentini A, Supuran CT, Pugliese AM, Pedata F. Role of Carbonic Anhydrase in Cerebral Ischemia and Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors as Putative Protective Agents. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supuran, CT. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and their potential in a range of therapeutic areas. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2018, 28, 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu L, Jifu C, Xia J, Wang J. E3 ligases and DUBs target ferroptosis: A potential therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024, 175, 116753. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).