Submitted:

11 June 2024

Posted:

12 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

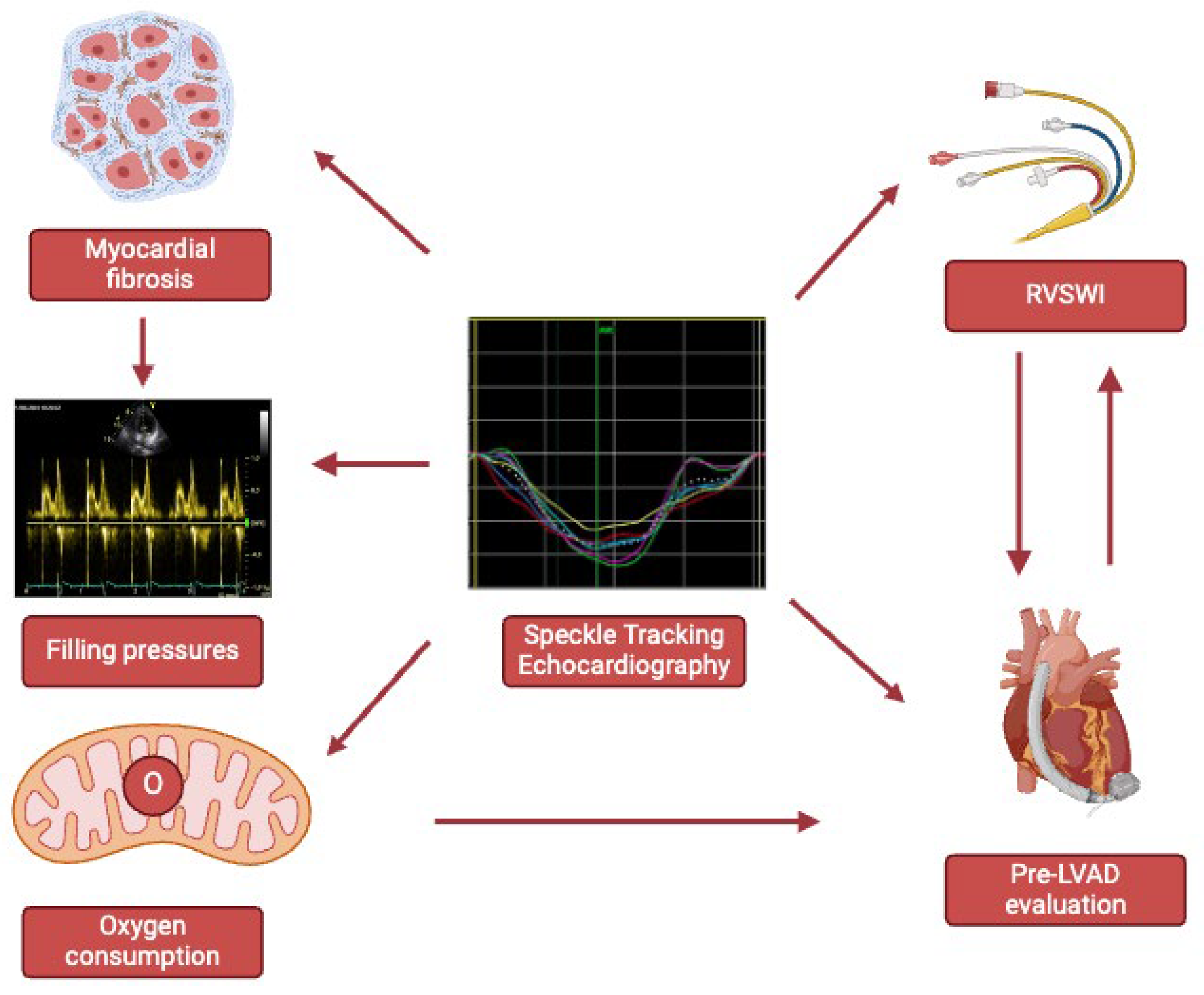

2. Speckle Tracking Echocardiography: Technical Aspects

3. Right Heart Catheterization

4. Myocardial Fibrosis

5. Left Heart Pressures, Strain and Fibrosis

6. Right Heart Pressures, Strain and Fibrosis

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2022, 24, 4–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coats, A.; Filippatos, G.; Bauersachs, J.; Rosano, G. The ESC Textbook of Heart Failure; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kalam, K.; Otahal, P.; Marwick, T.H. Prognostic implications of global LV dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global longitudinal strain and ejection fraction. Heart 2014, 100, 1673–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempny, A.; Diller, G.-P.; Kaleschke, G.; Orwat, S.; Funke, A.; Radke, R.; Schmidt, R.; Kerckhoff, G.; Ghezelbash, F.; Rukosujew, A.; et al. Longitudinal left ventricular 2D strain is superior to ejection fraction in predicting myocardial recovery and symptomatic improvement after aortic valve implantation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 2239–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnasamy, R.; Isbel, N.M.; Hawley, C.M.; Pascoe, E.M.; Burrage, M.; Leano, R.; Haluska, B.A.; Marwick, T.H.; Stanton, T. Left Ventricular Global Longitudinal Strain (GLS) Is a Superior Predictor of All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality When Compared to Ejection Fraction in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0127044–e0127044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, M.; Mandoli, G.E.; Lisi, E.; Ibrahim, A.; Incampo, E.; Buccoliero, G.; Rizzo, C.; Devito, F.; Ciccone, M.M.; Mondillo, S. Left atrial, ventricular and atrio-ventricular strain in patients with subclinical heart dysfunction. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 35, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefani, L.D.; Trivedi, S.J.; Ferkh, A.; Emerson, P.; Marschner, S.; Gan, G.; Altman, M.; Thomas, L. Left atrial mechanics evaluated by two-dimensional strain analysis: alterations in essential hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2024, 42, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondillo, S.; Cameli, M.; Caputo, M.L.; Lisi, M.; Palmerini, E.; Padeletti, M.; Ballo, P. Early Detection of Left Atrial Strain Abnormalities by Speckle-Tracking in Hypertensive and Diabetic Patients with Normal Left Atrial Size. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2011, 24, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, P.; Stefani, L.; Boyd, A.; Richards, D.; Hui, R.; Altman, M.; Thomas, L. Alterations in Left Atrial Strain in Breast Cancer Patients Immediately Post Anthracycline Exposure. Hear. Lung Circ. 2023, 33, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandoli, G.E.; Cameli, M.; Pastore, M.C.; Loiacono, F.; Righini, F.M.; D’ascenzi, F.; Focardi, M.; Cavigli, L.; Lisi, M.; Bisleri, G.; et al. Left ventricular fibrosis as a main determinant of filling pressures and left atrial function in advanced heart failure. Eur. Hear. J. - Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 25, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, M.; Sciaccaluga, C.; Loiacono, F.; Simova, I.; Miglioranza, M.H.; Nistor, D.; Bandera, F.; Emdin, M.; Giannoni, A.; Ciccone, M.M.; et al. The analysis of left atrial function predicts the severity of functional impairment in chronic heart failure: The FLASH multicenter study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 286, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, M.; Righini, F.M.; Lisi, M.; Bennati, E.; Navarri, R.; Lunghetti, S.; Padeletti, M.; Cameli, P.; Tsioulpas, C.; Bernazzali, S.; et al. Comparison of Right Versus Left Ventricular Strain Analysis as a Predictor of Outcome in Patients With Systolic Heart Failure Referred for Heart Transplantation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 112, 1778–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, M.; Lisi, M.; Righini, F.M.; Tsioulpas, C.; Bernazzali, S.; Maccherini, M.; Sani, G.; Ballo, P.; Galderisi, M.; Mondillo, S. Right Ventricular Longitudinal Strain Correlates Well With Right Ventricular Stroke Work Index in Patients With Advanced Heart Failure Referred for Heart Transplantation. J. Card. Fail. 2012, 18, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, M.; Cameli, M.; Righini, F.M.; Malandrino, A.; Tacchini, D.; Focardi, M.; Tsioulpas, C.; Bernazzali, S.; Tanganelli, P.; Maccherini, M.; et al. RV Longitudinal Deformation Correlates With Myocardial Fibrosis in Patients With End-Stage Heart Failure. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 8, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondillo, S.; Galderisi, M.; Mele, D.; Cameli, M.; Lomoriello, V.S.; Zacà, V.; Ballo, P.; D'Andrea, A.; Muraru, D.; Losi, M.; et al. Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography. J. Ultrasound Med. 2011, 30, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli M, Mondillo S, Galderisi M, Mandoli GE, Ballo P, Nistri S, Capo V, D'Ascenzi F, D'Andrea A, Esposito R, Gallina S, Montisci R, Novo G, Rossi A, Mele D, Agricola E. L’ecocardiografia speckle tracking: roadmap per la misurazione e l’utilizzo clinico [Speckle tracking echocardiography: a practical guide]. G Ital Cardiol (Rome). 2017 Apr;18(4):253-269. Italian. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perk, G.; Tunick, P.A.; Kronzon, I. Non-Doppler Two-dimensional Strain Imaging by Echocardiography–From Technical Considerations to Clinical Applications. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2007, 20, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, J.-U.; Pedrizzetti, G.; Lysyansky, P.; Marwick, T.H.; Houle, H.; Baumann, R.; Pedri, S.; Ito, Y.; Abe, Y.; Metz, S.; et al. Definitions for a Common Standard for 2D Speckle Tracking Echocardiography: Consensus Document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to Standardize Deformation Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimdal, A.; Støylen, A.; Torp, H.; Skjærpe, T. Real-Time Strain Rate Imaging of the Left Ventricle by Ultrasound. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 1998, 11, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Jenkins, C.; Marwick, T.H. Use of myocardial strain to assess global left ventricular function: A comparison with cardiac magnetic resonance and 3-dimensional echocardiography. Am. Hear. J. 2009, 157, 102–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, T.; Dulgheru, R.; Bernard, A.; Ilardi, F.; Contu, L.; Addetia, K.; Caballero, L.; Akhaladze, N.; Athanassopoulos, G.D.; Barone, D.; et al. Echocardiographic reference ranges for normal left ventricular 2D strain: results from the EACVI NORRE study. Eur. Hear. J. - Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 18, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Okura, H.; Watanabe, N.; Hayashida, A.; Obase, K.; Imai, K.; Maehama, T.; Kawamoto, T.; Neishi, Y.; Yoshida, K. Comprehensive Evaluation of Left Ventricular Strain Using Speckle Tracking Echocardiography in Normal Adults: Comparison of Three-Dimensional and Two-Dimensional Approaches. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2009, 22, 1025–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badano, L.P.; Kolias, T.J.; Muraru, D.; Abraham, T.P.; Aurigemma, G.; Edvardsen, T.; D’Hooge, J.; Donal, E.; Fraser, A.G.; Marwick, T.; et al. Standardization of left atrial, right ventricular, and right atrial deformation imaging using two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography: a consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to standardize deformation imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 19, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, F.; D'Elia, N.; Nolan, M.T.; Marwick, T.H.; Negishi, K. Normal Ranges of Left Atrial Strain by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017, 30, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Park, J.-H. Strain Analysis of the Right Ventricle Using Two-dimensional Echocardiography. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 26, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghiade, M.; Follath, F.; Ponikowski, P.; Barsuk, J.H.; Blair, J.E.; Cleland, J.G.; Dickstein, K.; Drazner, M.H.; Fonarow, G.C.; Jaarsma, T.; et al. Assessing and grading congestion in acute heart failure: a scientific statement from the Acute Heart Failure Committee of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2010, 12, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, H.; Chatterjee, K.; Davis, K.; Fifer, M.; Franklin, C.; Greenberg, M.; Labovitz, A.; Shah, P.; Tuman, K.; Weil, M.; et al. Present use of bedside right heart catheterization in patients with cardiac disease. Circ. 1998, 32, 840–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K. The Swan-Ganz Catheters: Past, Present, and Future. Circulation 2009, 119, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rio-Pertuz, G.; Nugent, K.; Argueta-Sosa, E. Right heart catheterization in clinical practice: a review of basic physiology and important issues relevant to interpretation. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2023, 13, 122–137.

- Bootsma, I.T.; Boerma, E.C.; Scheeren, T.W.L.; de Lange, F. The contemporary pulmonary artery catheter. Part 2: measurements, limitations, and clinical applications. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2021, 36, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2200879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J.S.; Ganz, W.; Diamond, G.; McHugh, T.; Chonette, D.W.; Swan, H. Thermodilution cardiac output determination with a single flow-directed catheter. Am. Hear. J. 1972, 83, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagard, R.; Conway, J. Measurement of cardiac output: Fick principle using catheterization. Eur. Hear. J. 1990, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.S.; Gustafsson, F. Pulmonary artery pulsatility index: physiological basis and clinical application. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2020, 22, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, T.D.; Wiedemann, H.P. COMPLICATIONS OF HEMODYNAMIC MONITORING. Clin. Chest Med. 1999, 20, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D.; Mulvihill, D.; Lew, W.Y.W. Risk of developing complete heart block during bedside pulmonary artery catheterization in patients with left bundle-branch block. Arch. Intern. Med. 1987, 147, 2005–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprung, C.L.; Elser, B.; Schein, R.M.H.; Marcial, E.H.; Schrager, B.R. Risk of right bundle-branch block and complete heart block during pulmonary artery catheterization. Crit. Care Med. 1989, 17, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, T.J.; Shabot, M.M. Pulmonary Artery Rupture Associated With the Swan-Ganz Catheter. Chest 1995, 108, 1349–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieske, B.; Tschöpe, C.; A de Boer, R.; Fraser, A.G.; Anker, S.D.; Donal, E.; Edelmann, F.; Fu, M.; Guazzi, M.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the HFA–PEFF diagnostic algorithm: a consensus recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Hear. J. 2019, 40, 3297–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henein, M.Y.; Tossavainen, E.; A'Roch, R.; Söderberg, S.; Lindqvist, P. Can Doppler echocardiography estimate raised pulmonary capillary wedge pressure provoked by passive leg lifting in suspected heart failure? Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2018, 39, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.H.; Brooks, W.W.; Hayes, J.A.; Sen, S.; Robinson, K.G.; Bing, O.H.L. Myocardial Fibrosis and Stiffness With Hypertrophy and Heart Failure in the Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat. Circulation 1995, 91, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, D.A.; Bronzwaer, J.G.; Paulus, W.J. What Mechanisms Underlie Diastolic Dysfunction in Heart Failure? Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 1533–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, M.; Cameli, M.; Mandoli, G.E.; Pastore, M.C.; Righini, F.M.; D’ascenzi, F.; Focardi, M.; Rubboli, A.; Mondillo, S.; Henein, M.Y. Detection of myocardial fibrosis by speckle-tracking echocardiography: from prediction to clinical applications. Hear. Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 1857–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyöngyösi, M.; Winkler, J.; Ramos, I.; Do, Q.; Firat, H.; McDonald, K.; González, A.; Thum, T.; Díez, J.; Jaisser, F.; et al. Myocardial fibrosis: biomedical research from bench to bedside. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2017, 19, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandoli, G.E.; D'Ascenzi, F.; Vinco, G.; Benfari, G.; Ricci, F.; Focardi, M.; Cavigli, L.; Pastore, M.C.; Sisti, N.; De Vivo, O.; et al. Novel Approaches in Cardiac Imaging for Non-invasive Assessment of Left Heart Myocardial Fibrosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, J.G.; Kamal, F.A.; Robbins, J.; Yutzey, K.E.; Blaxall, B.C. Cardiac Fibrosis: The Fibroblast Awakens. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 1021–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampaktsis, P.N.; Kokkinidis, D.G.; Wong, S.-C.; Vavuranakis, M.; Skubas, N.J.; Devereux, R.B. The role and clinical implications of diastolic dysfunction in aortic stenosis. Heart 2017, 103, 1481–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krayenbuehl, H.P.; Hess, O.M.; Monrad, E.S.; Schneider, J.; Mall, G.; Turina, M. Left ventricular myocardial structure in aortic valve disease before, intermediate, and late after aortic valve replacement. Circulation 1989, 79, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zile, M.R.; Tomita, M.; Nakano, K.; Mirsky, I.; Usher, B.; Lindroth, J.; Carabello, B.A. Effects of left ventricular volume overload produced by mitral regurgitation on diastolic function. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 1991, 261, H1471–H1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, M.; Lisi, M.; Giacomin, E.; Caputo, M.; Navarri, R.; Malandrino, A.; Ballo, P.; Agricola, E.; Mondillo, S. Chronic Mitral Regurgitation: Left Atrial Deformation Analysis by Two-Dimensional Speckle Tracking Echocardiography. Echocardiography 2011, 28, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonow, R.O. Left Atrial Function in Mitral Regurgitation. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 7, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidemann, F.; Herrmann, S.; Störk, S.; Niemann, M.; Frantz, S.; Lange, V.; Beer, M.; Gattenlöhner, S.; Voelker, W.; Ertl, G.; et al. Impact of Myocardial Fibrosis in Patients With Symptomatic Severe Aortic Stenosis. Circulation 2009, 120, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Franzone, A.; Lanz, J.; Siontis, G.C.; Stortecky, S.; Gräni, C.; Roost, E.; Windecker, S.; Pilgrim, T. Early Detection of Subclinical Myocardial Damage in Chronic Aortic Regurgitation and Strategies for Timely Treatment of Asymptomatic Patients. Circulation 2018, 137, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieske, B.; Tschöpe, C.; A de Boer, R.; Fraser, A.G.; Anker, S.D.; Donal, E.; Edelmann, F.; Fu, M.; Guazzi, M.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the HFA–PEFF diagnostic algorithm: a consensus recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Hear. J. 2021, 40, 3297–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, M.; Mandoli, G.E.; Loiacono, F.; Dini, F.L.; Henein, M.; Mondillo, S. Left atrial strain: a new parameter for assessment of left ventricular filling pressure. Hear. Fail. Rev. 2015, 21, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, M.; Sparla, S.; Losito, M.; Righini, F.M.; Menci, D.; Lisi, M.; D'Ascenzi, F.; Focardi, M.; Favilli, R.; Pierli, C.; et al. Correlation of Left Atrial Strain and Doppler Measurements with Invasive Measurement of Left Ventricular End-Diastolic Pressure in Patients Stratified for Different Values of Ejection Fraction. Echocardiography 2016, 33, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, M.; Tanboga, I.H.; Aksakal, E.; Kaya, A.; Isik, T.; Ekinci, M.; Bilen, E. Relation of left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide level with left atrial deformation parameters. Eur. Hear. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2012, 13, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, M.; Lisi, M.; Focardi, M.; Reccia, R.; Natali, B.M.; Sparla, S.; Mondillo, S. Left Atrial Deformation Analysis by Speckle Tracking Echocardiography for Prediction of Cardiovascular Outcomes. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 110, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D.A.; Belyavskiy, E.; Aravind-Kumar, R.; Kropf, M.; Frydas, A.; Braunauer, K.; Marquez, E.; Krisper, M.; Lindhorst, R.; Osmanoglou, E.; et al. Potential Usefulness and Clinical Relevance of Adding Left Atrial Strain to Left Atrial Volume Index in the Detection of Left Ventricular Diastolic Dysfunction. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D.A.; Takeuchi, M.; Krisper, M.; Köhncke, C.; Bekfani, T.; Carstensen, T.; Hassfeld, S.; Dorenkamp, M.; Otani, K.; Takigiku, K.; et al. Normal values and clinical relevance of left atrial myocardial function analysed by speckle-tracking echocardiography: multicentre study. Eur. Hear. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 16, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Khan, F.H.; Remme, E.W.; Ohte, N.; García-Izquierdo, E.; Chetrit, M.; Moñivas-Palomero, V.; Mingo-Santos, S.; Andersen. S.; Gude, E.; et al. Determinants of left atrial reservoir and pump strain and use of atrial strain for evaluation of left ventricular filling pressure. Eur. Hear. J. - Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 23, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henein, M.Y.; Holmgren, A.; Lindqvist, P. Left atrial function in volume versus pressure overloaded left atrium. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 31, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, M.; Sciaccaluga, C.; Loiacono, F.; Simova, I.; Miglioranza, M.H.; Nistor, D.; Bandera, F.; Emdin, M.; Giannoni, A.; Ciccone, M.M.; et al. The analysis of left atrial function predicts the severity of functional impairment in chronic heart failure: The FLASH multicenter study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 286, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, M.; Mandoli, G.E.; Cameli, M.; Pastore, M.C.; Righini, F.M.; Benfari, G.; Rubboli, A.; D’ascenzi, F.; Focardi, M.; Tsioulpas, C.; et al. Left atrial strain by speckle tracking predicts atrial fibrosis in patients undergoing heart transplantation. Eur. Hear. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 23, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, B.L.; Castilho, B. New insights into assessing severity of advanced heart failure through left atrial mechanics. Eur. Hear. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateshvaran, A.; Tureli, H.O.; Faxén, U.L.; Lund, L.H.; Tossavainen, E.; Lindqvist, P. Left atrial reservoir strain improves diagnostic accuracy of the 2016 ASE/EACVI diastolic algorithm in patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: insights from the KARUM haemodynamic database. Eur. Hear. J. - Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 23, 1157–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Smiseth, O.; A Morris, D.; Cardim, N.; Cikes, M.; Delgado, V.; Donal, E.; A Flachskampf, F.; Galderisi, M.; Gerber, B.L.; Gimelli, A.; et al. Multimodality imaging in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: an expert consensus document of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Hear. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 23, e34–e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, G.-Y.; Marwick, T.H.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, M.-K.; Hong, K.-S.; Oh, D.-J. Global 2-Dimensional Strain as a New Prognosticator in Patients With Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009, 54, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengeløv, M.; Jørgensen, P.G.; Jensen, J.S.; Bruun, N.E.; Olsen, F.J.; Fritz-Hansen, T.; Nochioka, K.; Biering-Sørensen, T. Global Longitudinal Strain Is a Superior Predictor of All-Cause Mortality in Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 8, 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, M.; Mondillo, S.; Righini, F.M.; Lisi, M.; Dokollari, A.; Lindqvist, P.; Maccherini, M.; Henein, M. Left Ventricular Deformation and Myocardial Fibrosis in Patients With Advanced Heart Failure Requiring Transplantation. J. Card. Fail. 2016, 22, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadic, M.; Pieske-Kraigher, E.; Cuspidi, C.; Morris, D.A.; Burkhardt, F.; Baudisch, A.; Haßfeld, S.; Tschöpe, C.; Pieske, B. Right ventricular strain in heart failure: Clinical perspective. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 110, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoki, H.; Borowski, A.G.; Shrestha, K.; Hu, B.; Kusunose, K.; Troughton, R.W.; Tang, W.; Klein, A.L. Right Ventricular Global Longitudinal Strain Provides Prognostic Value Incremental to Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction in Patients with Heart Failure. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2014, 27, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barssoum, K.; Altibi, A.M.; Rai, D.; Kharsa, A.; Kumar, A.; Chowdhury, M.; Elkaryoni, A.; Abuzaid, A.S.; Baibhav, B.; Parikh, V.; et al. Assessment of right ventricular function following left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation—The role of speckle-tracking echocardiography: A meta-analysis. Echocardiography 2020, 37, 2048–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, M.; Loiacono, F.; Sparla, S.; Solari, M.; Iardino, E.; Mandoli, G.E.; Bernazzali, S.; Maccherini, M.; Mondillo, S. Systematic Left Ventricular Assist Device Implant Eligibility with Non-Invasive Assessment: The SIENA Protocol. J. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound 2017, 25, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stricagnoli, M.; Sciaccaluga, C.; Mandoli, G.E.; Rizzo, L.; Sisti, N.; Aboumarie, H.S.; Benfari, G.; Maritan, L.; Tsioulpas, C.; Bernazzali, S.; et al. Clinical, echocardiographic and hemodynamic predictors of right heart failure after LVAD placement. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 38, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindow T, Manouras A, Lindqvist P, Manna D, Wieslander B, Kozor R, Strange G, Playford D, Ugander M. Echocardiographic estimation of pulmonary artery wedge pressure: invasive derivation, validation, and prognostic association beyond diastolic dysfunction grading. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2024 Mar 27;25(4):498-509. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Reference values (%) |

|---|---|

| Left ventricle | |

| GLS | -17.2 - -27.7 |

| GRS | 21.1 – 53.8 |

| GCS | -23.1 - -40.6 |

| Left atrium | |

| PALS | 42.3 – 52.4 age 20-40 35.4 – 46.1 age 40-60 30.9 – 41.9 age > 60 |

| PACS | 11.9 – 19.0 age 20-40 13.2 – 19.6 age 40-60 13.6 – 21.4 age > 60 |

| Right ventricle | |

| RVFWS | > -20 |

| HTx check list |

| Diagnosis and differential diagnosis for PH |

| Fulminant myocarditis |

| Peripartum cardiomyopathy |

| Differential diagnosis for sepsis |

| ADHF requiring inotropic, vasopressor, and vasodilator therapy |

| Cardiogenic shock |

| Discordant left and right ventricular dysfunction |

| Parameter | Reference values |

|---|---|

| Right atrium | |

| Mean RAP | 2-8 mmHg |

| RA a wave | 3-7 mmHg |

| RA v wave | 3-8 mmHg |

| Right ventricle | |

| RVESP | 17-32 mmHg |

| RVEDP | 2-8 mmHg |

| Pulmonary artery | |

| mPAP | 10-21 mmHg |

| sPAP | 17-32 mmHg |

| dPAP | 4-15 mmHg |

| PCWP | 2-8 mmHg |

| Left atrium | |

| Mean LAP | 6-12 mmHg |

| LA a wave | 4-14 mmHg |

| LA v wave | 6-16 mmHg |

| Left ventricle | |

| LVESP | 90-140 mmHg |

| LVEDP | 5-12 mmHg |

| Derived parameters | |

| CO | 2.5-4.5 mL/min/m2 |

| PVR | <2 WU |

| RVSWI | 5-10 g*m2/beat |

| PAPi | 0.9 in RV infarction <1.85 in patients undergoing LVAD implantation <3.65 in patients with advanced HF |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).