Submitted:

11 June 2024

Posted:

12 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

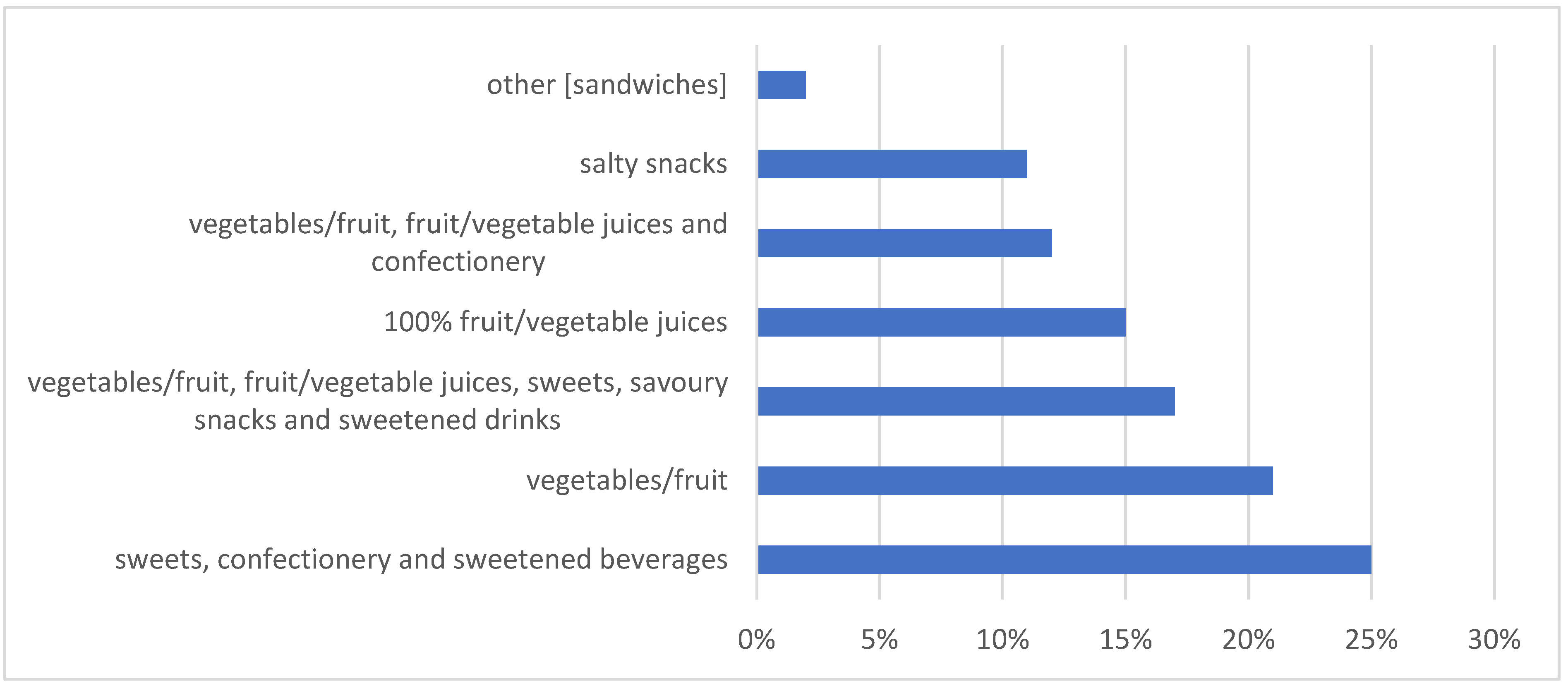

4.1. Snacks – Choice and Frequency of Consumption among Children and Adolescents

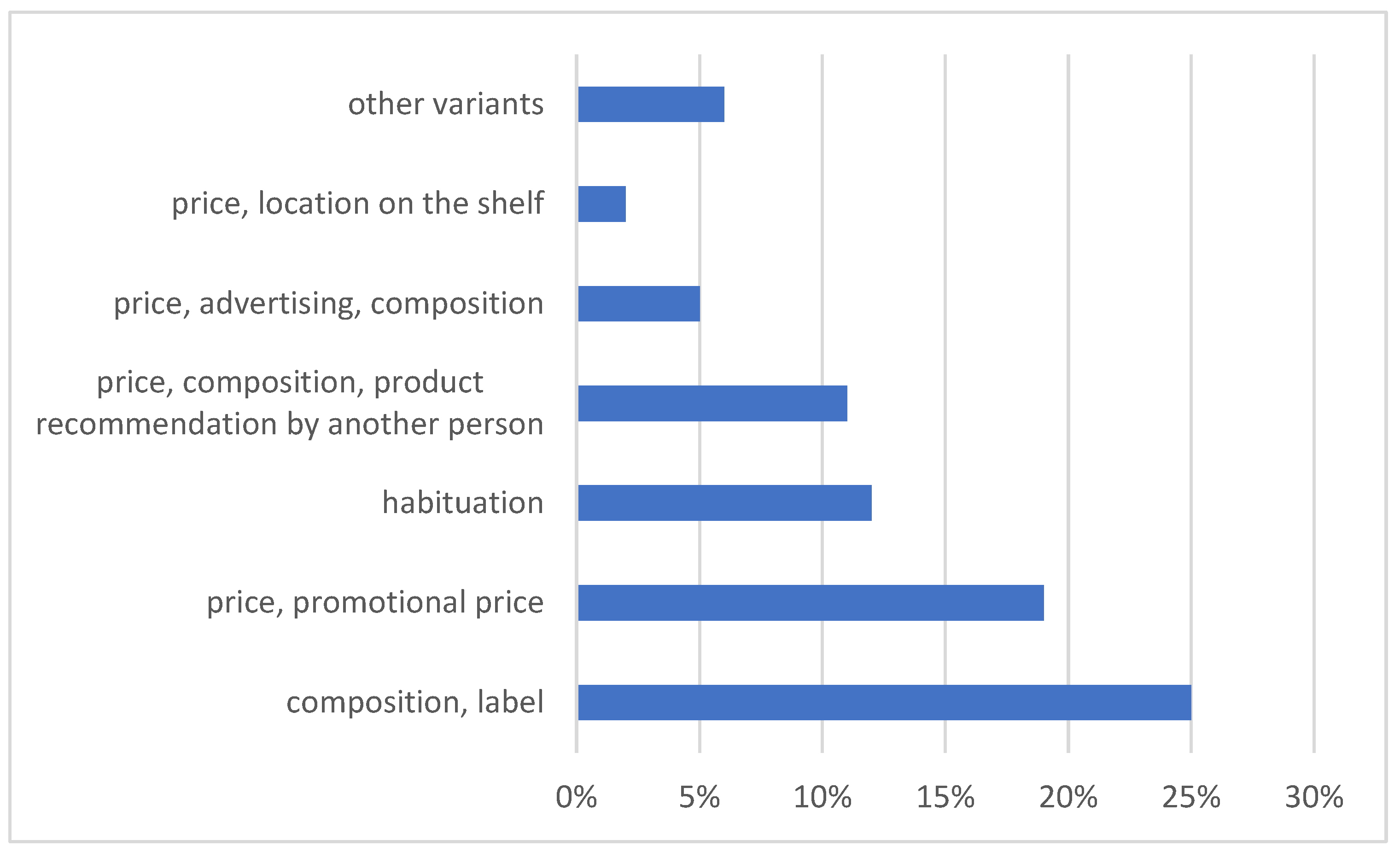

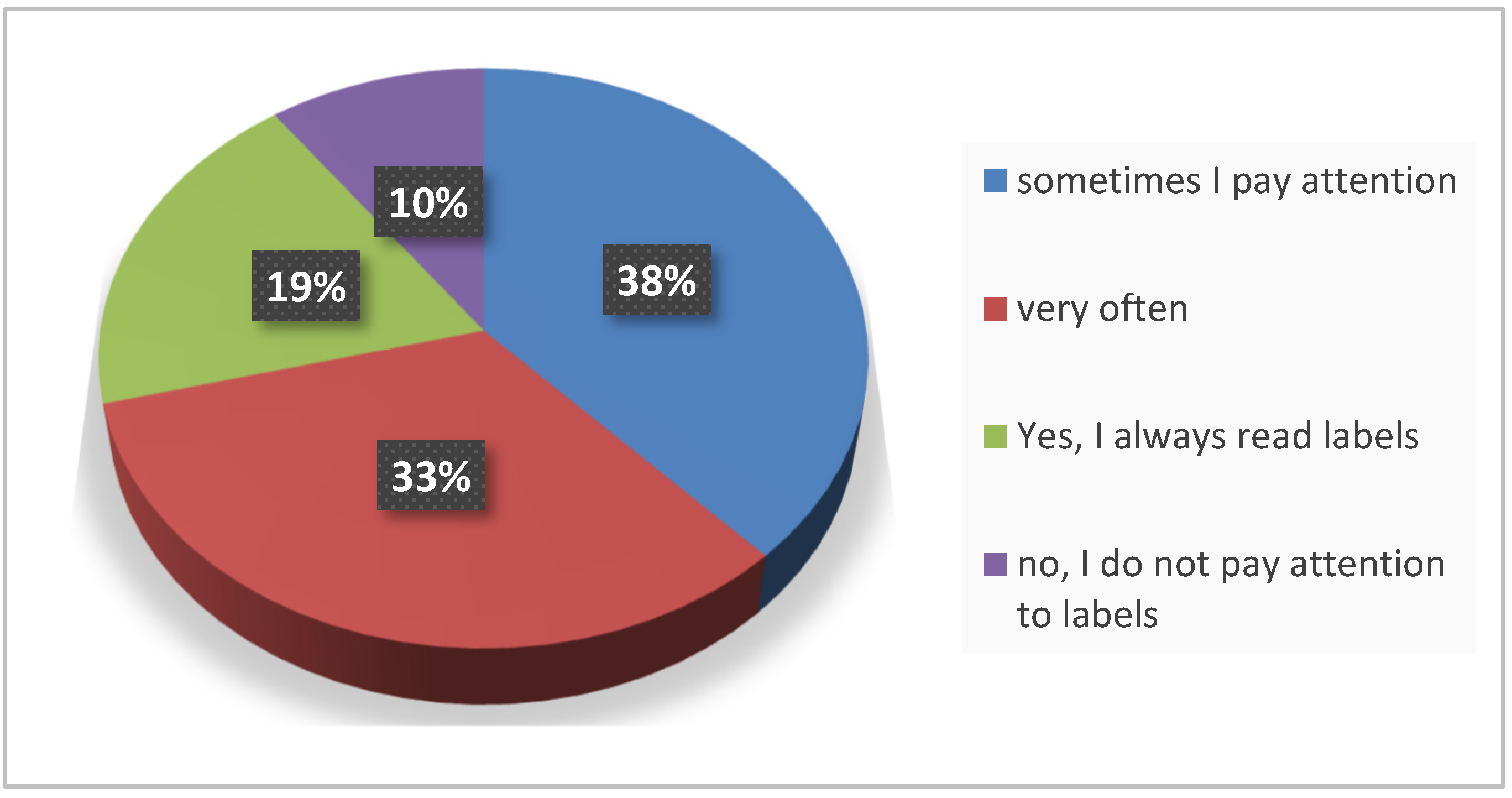

4.2. Selection of Food Products – Labels

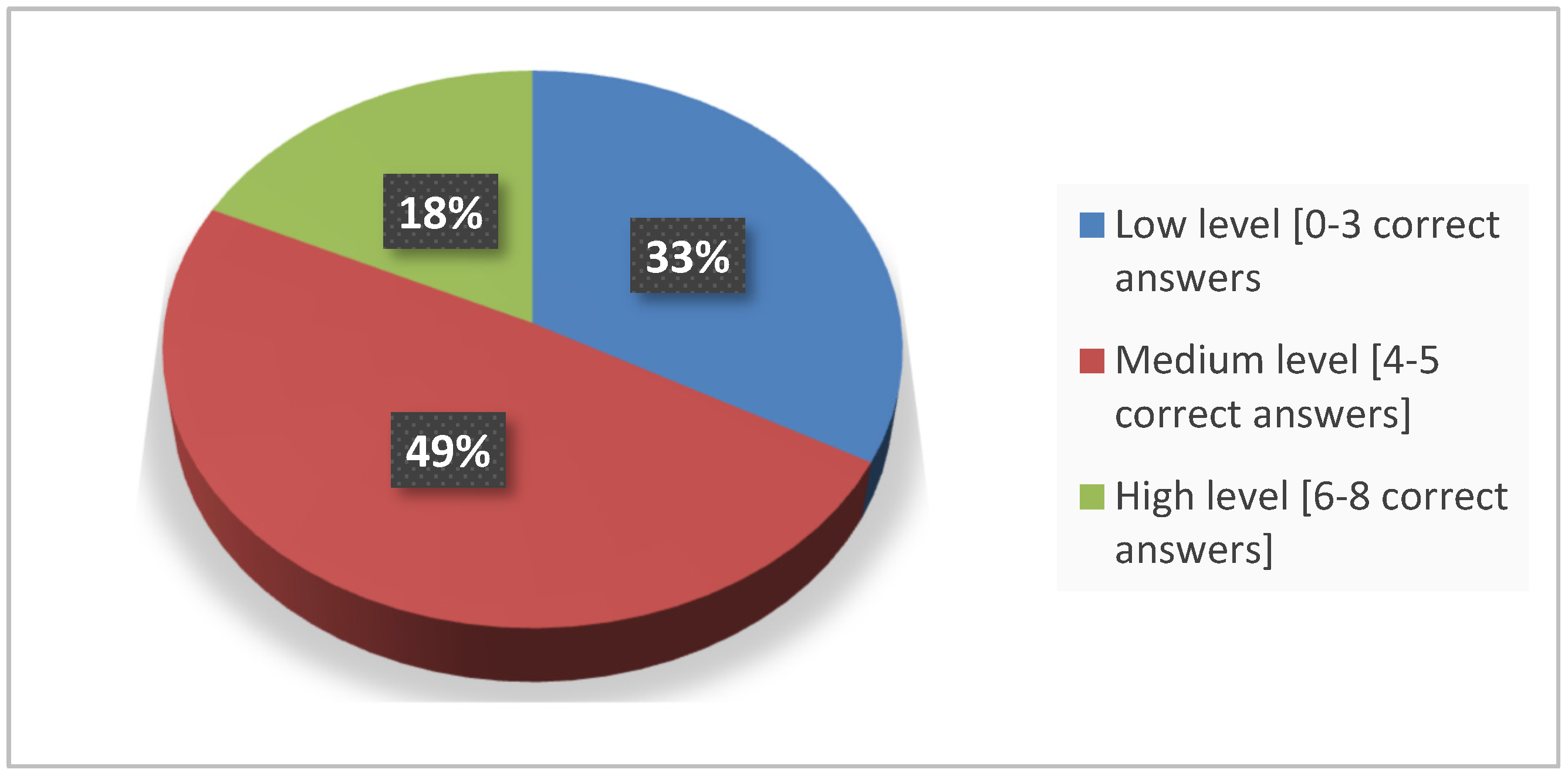

4.3. Food Additives - Impact on Health - Knowledge of Parents

5. Conclusions

- Children most often chose sweets, confectionery and sweet drinks as a form of snack, followed by vegetables and fruits. Snacks in the form of sweets and sweet drinks were consumed very often during the day, which should be considered as highly unsatisfactory nutritional behaviour.

- Parents of school-age children have shown an average level of knowledge about food additives, most often sometimes read food labels checking the composition, guided by promotional price and habit.

- A correlation between parents’ level of knowledge about additives and their level of education has been demonstrated. The higher the level of education, the greater the parents’ knowledge of food additives was and associated with lower consumption of sweetened beverages by their children. The knowledge and education of the parents did not significantly affect the level of consumption of other snacks.

- The nutritional behavior of children and adolescents should be monitored, as they exhibit unfavorable eating habits, often eating foods of low nutritional value between meals, increasing the risk of developing obesity and other health problems.

- There is a clear need for preventive action and nutritional education of the public, especially children and parents, on proper nutrition, reading product labels for the content of additives and the harmfulness of excessive consumption.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kolmaga, A.; Trafalska, E.; Szatko, F. Risk factors of excessive body mass in children and adolescents in Łódź. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 2019, 70, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachtan-Janicka, J. The Pyramid of Healthy Eating and Lifestyle. Medical Standards. Pediatrics 2019, 16, 743–750. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, B.J.; Bestle, S.M.S.; Trolle, E.; Biltoft-Jensen, A.P.; Matthiessen, J.; Lassen, A.D. A Qualitative Evaluation of Social Aspects of Sugar-Rich Food and Drink Intake and Parental Strategies for Reductions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gierlak, M.; Jarzyna, S.; Brzeziński, M. Growing problem, ineffective action. Access to prevention and treatment of obesity in children and adolescents. Control and audit 2022, 3, 462–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaine, R.E.; Kachurak, A.; Davison, K.K.; Klabunde, R.; Fisher, J.O. Food parenting and child snacking: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripicchio, L.G.; Bailey, L.R.; Davey, A.; Croce, M.Ch.; Fisher, O.J. Snack frequency, size, and energy density are associated with diet quality among US adolescents. Public Health Nutr 2023, 26, 2374–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piasecka, A.; Lesiów, T. Snacks and eating habits among preschool children. Engineering Sciences and Technologies 2019, 3(34), 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumena, W.A. Maternal Knowledge, Attitude and Practices toward Free Sugar and the Associations with Free Sugar Intake in Children. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, C.E.; Davison, K.K.; Blaine, R.E.; Fisher, J.O. Occasions, purposes, and contexts for offering snacks to preschool-aged children: schemas of caregivers with low-income backgrounds. Appetite 2021, 167, 105627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, M.Ch.; Fisher, J.O.; Coffman, L.D.; Bailey, L.R.; Davey, A.; Tripicchio, L.G. Association of weight status with the types of foods consumed at snacking occasions among US adolescents. Obesity 2022, 30, 2459–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, M. Pyramid of Healthy Nutrition and Physical Activity for children and adolescents. Human Nutrition and Metabolism 2016, 43, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmaga, A.; Godala, M.; Trafalska, E.; Kaleta, D.; Szatko, F. Organization of nutritional education at school. Part I – structure of food consumption. Entrepreneurship and Management 2016, 17, 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmaga, A.; Godala, M.; Rzeźnicki, A.; Trafalska, E.; Szatko, F. Organization of nutritional education at school. Part II – Selection of food products. Entrepreneurship and Management, 2016; 17, 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kapczuk, P.; Komorniak, M.; Rogulska, K.; Bosiacki, M.; Chlubek, D. Highly processed foods and their impact on the health of children and adults. Advances in Biochemistry 2020, 66, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowska, J. Family nutrition as an important factor in shaping eating habits in children and adolescents. Polish Nursing 2014, 1, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Charzewska, J.; Chwojnowska, Z.; Wajszczyk, B. Snacks: type and frequency of consumption by children and adolescents. Human Nutrition and Metabolism 2016, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Sosnowska-Bielicz, E.; Wrótniak, J. Nutritional habits and obesity in preschool and school children, Lublin Pedagogical Yearbook, 2013, 32, 147–165. 32.

- Jonczyk, P.; Potempa, M.; Kajdaniuk, D. Characteristics of eating habits and physical activity among school children aged 11 to 13 in the city of Piekary Śląskie. Metabolic Medicine 2015, 19, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mendyk, K.; Antos-Latek, K.; Kowalik, M.; Pagacz, K.; Lewicki, M.; Obel, E. Health-promoting behaviours related to nutrition and physical activity in school children and adolescents up to 18 years of age. Piel Zdr Publ. 2017, 26, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripicchio, L.G.; Croce, M.Ch.; Coffman, L.D.; Pettinato, C.; Fisher, O. J. Age-related differences in eating location, food source location, and timing of snack intake among U.S. children 1–19 years. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2023, 20, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, A. Consumer awareness of food safety and how they can mitigate risk. Domestic Trade 2018, 2, 246–260. [Google Scholar]

- Rakuła, M.; Kiciak, A. Consumer knowledge of food labeling. Journal of Education. Health and Sport 2022, 12, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuKhader, M.; Nazmi, A.; Lekshmi, U.M. Identification and Prevalence of Food Colors in Candies Commonly Consumed by Children in Muscat, Oman. Int J Nutr Pharmacol Neurol Dis 2021, 11, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.R.; Oliveira, A. Dietary Interventions to Prevent Childhood Obesity: A Literature Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salejda, A.M.; Krasnowska, G.; Buska, K. Consumer on the Food Market – Their Knowledge and Behaviour, Food for the Conscious Consumer, Faculty of Food and Nutrition Sciences, University of Life Sciences in Poznań 2016, 1, 15-24. 1.

- Piekut, M. Clean label very desirable. Dairy Trade Forum 2023, 1, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah, Y.; Moy, F.; Loh, D. Socio-demographic and lifestyle factors associated with nutrition label use among Malaysian adults. British Food Journal 2015, 117, 2777–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonowicz, K.; Osmala-Kurpiewska, W.; Piekut, A. Parents are aware of the risks to children’s health resulting from exposure to selected chemicals passing from plastic packaging into food. Med Og Nauk Zdr 2021, 27, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gketsios, I.; Tsiampalis, T.; Kanellopoulou, A.; Vassilakou, T.; Notara, V.; Antonogeorgos, G.; Rojas-Gil, A.P.; Kornilaki, E.N.; Lagiou, A.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; et al. The Synergetic Effect of Soft Drinks and Sweet/Salty Snacks Consumption and the Moderating Role of Obesity on Preadolescents’ Emotions and Behavior: A School-Based Epidemiological Study. Life 2023, 13, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stachowicz, J. Chemistry in the kitchen – history, necessity and dangers. Food Processing Engineering 2016, 4/4, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Supreme Audit Office. Supervision of the use of food additives LLO.430.003.2018 Nr ewid. 173/2018/P/18/082/LLO, Available online:. Available online: www.nik.gov.pl (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Savin, M.; Vrkati´c, A.; Dedi´c, D.; Vlaški, T.; Vorguˇcin, I.; Bjelanovi´c, J.; Jevtic, M. Additives in Children’s Nutrition-A Review of Current Events. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, S.L.; D’Adamo, C.R.; Holton, K.F.; Ortiz, S.; Overby, N.; Logan, A.C. Beyond Plants: The Ultra-Processing of Global Diets Is Harming the Health of People, Places, and Planet. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, N.T.; Jacobs, D.R.; MacLehose, R.F.; Demerath, E.W.; Kelly, S.P.; Dreyfus, J.G.; Pereira, M.A. Consumption of Caffeinated and Artificially Sweetened Soft Drinks Is Associated with Risk of Early Menarche. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasilewska, E.; Małgorzewicz, S. Adverse food reactions to food additives. Metabolic Disorders Forum 2015, 6, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bradman, A.; Castorina, R.; Thilakaratne, R.; Gillan, M.; Pattabhiraman, T.; Nirula, A.; Marty, M.; Miller, M.D. Dietary Exposure to United States Food and Drug Administration-Approved Synthetic Food Colors in Children, Pregnant Women, and Women of Childbearing Age Living in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoś, K.; Jarosz, M.; Wojda, B.; Ołtarzewski, M. Research on the intake of selected dyes from the diet among children and adolescents in Poland. Human nutrition and metabolism 2019, 46, 140–142. [Google Scholar]

- Asif, A.M.; Al-Khalifa, A.S.; Al-Nouri, D.M.; El-Din, M.F.S. Dietary intake of artificial food color additives containing food products by school-going children. Saudi J Biol Sci 2021, 28, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemanowicz, M. Consumer awareness of additives used on the food market in Poland. Marketing and Market 2015, 8, 332. [Google Scholar]

- Januś, E.; Sablik, P.; Grzechnik, M. Consumer awareness of additives used on the food market. Acta Sci. Pol. Zootechnica 2023, 22, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key data | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| woman | 101 | 78.3 |

| man | 28 | 21.7 |

| Level of education | ||

| basic | 14 | 10.9 |

| professional | 21 | 16.3 |

| average | 29 | 22.4 |

| higher | 65 | 50.4 |

| Frequency of intake | Sweets (%) | Salty snacks (%) | Sweet drinks (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| several times a day | 12 | 9.3 | 4 | 3.1 | 35 | 27.1 |

| once a day | 43 | 33.3 | 19 | 14.7 | 25 | 19.4 |

| several times a week | 49 | 38.0 | 47 | 36.4 | 30 | 23.3 |

| once a week | 15 | 11.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| several times a month | 10 | 7.8 | 54 | 41.9 | 30 | 23.3 |

| Not at all | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3.9 | 9 | 6.9 |

| Parents' level of knowledge | Level of education | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher | Average | Basic and professional | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| High | 16 | 24.6 | 4 | 13.8 | 3 | 8.6 | 23 |

| Average | 36 | 55.4 | 11 | 37.9 | 16 | 45.7 | 63 |

| Weak | 13 | 20.0 | 14 | 48.3 | 16 | 45.7 | 43 |

| Total | 65 | 100.0 | 29 | 100.0 | 35 | 100.0 | 129 |

| Consumption of snacks (behaviour) | Level of education of parents | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher | Average | Basic and professional | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Vegetables/fruit | |||||||

| Beneficial | 18 | 27.7 | 7 | 24.1 | 6 | 17.1 | 31 |

| Negative | 47 | 73.3 | 22 | 75.9 | 29 | 82.7 | 98 |

| Comparison | chi2=1.387; p=0.501 | ||||||

| Sweets | |||||||

| Beneficial | 12 | 18.5 | 6 | 20.7 | 5 | 14.3 | 23 |

| Negative | 53 | 81.5 | 23 | 79.3 | 30 | 85.7 | 106 |

| Comparison | chi2=0.480; p=0.787 | ||||||

| Sweet drinks | |||||||

| Beneficial | 26 | 40.0 | 9 | 31.0 | 5 | 14.3 | 40 |

| Negative | 39 | 60.0 | 20 | 69.0 | 30 | 85.7 | 89 |

| Comparison | chi2=7.032; p=0.0297 | ||||||

| Salty snacks | |||||||

| Beneficial | 29 | 44.6 | 13 | 44.8 | 16 | 45.7 | 58 |

| Negative | 36 | 55.4 | 16 | 55.2 | 19 | 54.3 | 71 |

| Comparison | chi2=0.011; p=0.994 | ||||||

| Consumption of snacks (behaviour) | Level of knowledge of parents | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Average | Low | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Vegetables/fruit | |||||||

| Beneficial | 8 | 34.8 | 16 | 25.4 | 7 | 16.3 | 31 |

| Negative | 15 | 65.2 | 47 | 74.6 | 36 | 83.7 | 98 |

| Comparison | chi2=2.936; p=0.230 | ||||||

| Sweets | |||||||

| Beneficial | 4 | 17.4 | 11 | 17.5 | 8 | 18.6 | 23 |

| Negative | 19 | 82.6 | 52 | 82.5 | 35 | 81.4 | 106 |

| Comparison | chi2=0.027; p=0.987 | ||||||

| Sweet drinks | |||||||

| Beneficial | 9 | 39.1 | 20 | 31.8 | 11 | 25.6 | 40 |

| Negative | 14 | 60.9 | 43 | 68.2 | 32 | 74.4 | 89 |

| Comparison | chi2=1.317; p=0.518 | ||||||

| Salty snacks | |||||||

| Beneficial | 11 | 47.8 | 32 | 50.8 | 15 | 34.9 | 58 |

| Negative | 12 | 52.2 | 31 | 49.2 | 28 | 65.1 | 71 |

| Comparison | chi2=2.707; p=0.258 | ||||||

| Pay attention to labels before buying | Level of knowledge | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Average | Low | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Always | 7 | 30.5 | 10 | 15.9 | 7 | 16.3 | 24 |

| Very often | 8 | 34.8 | 23 | 36.5 | 12 | 27.9 | 43 |

| Sometimes they pay attention | 7 | 30.4 | 23 | 36.5 | 19 | 44.2 | 49 |

| Does not pay attention | 1 | 4.3 | 7 | 11.1 | 5 | 11.6 | 13 |

| Total | 23 | 100.0 | 63 | 100.0 | 43 | 100.0 | 129 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).