Submitted:

11 June 2024

Posted:

12 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

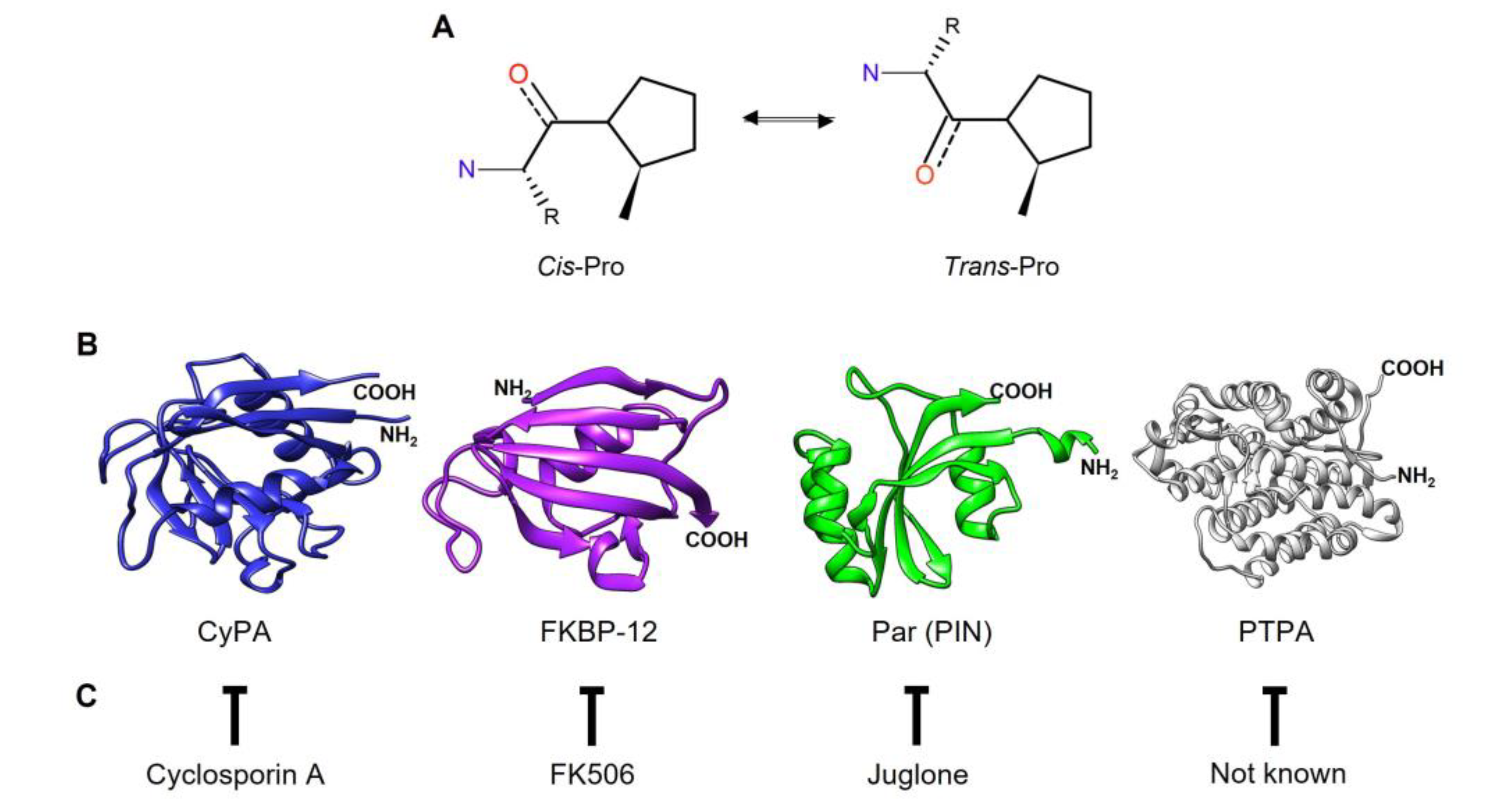

1. Introduction

2. Parasite PPIases: Disease, Genome Database, and Structural Characteristics

2.1. Anaerobic or Microaerophilic Protozoan Parasites

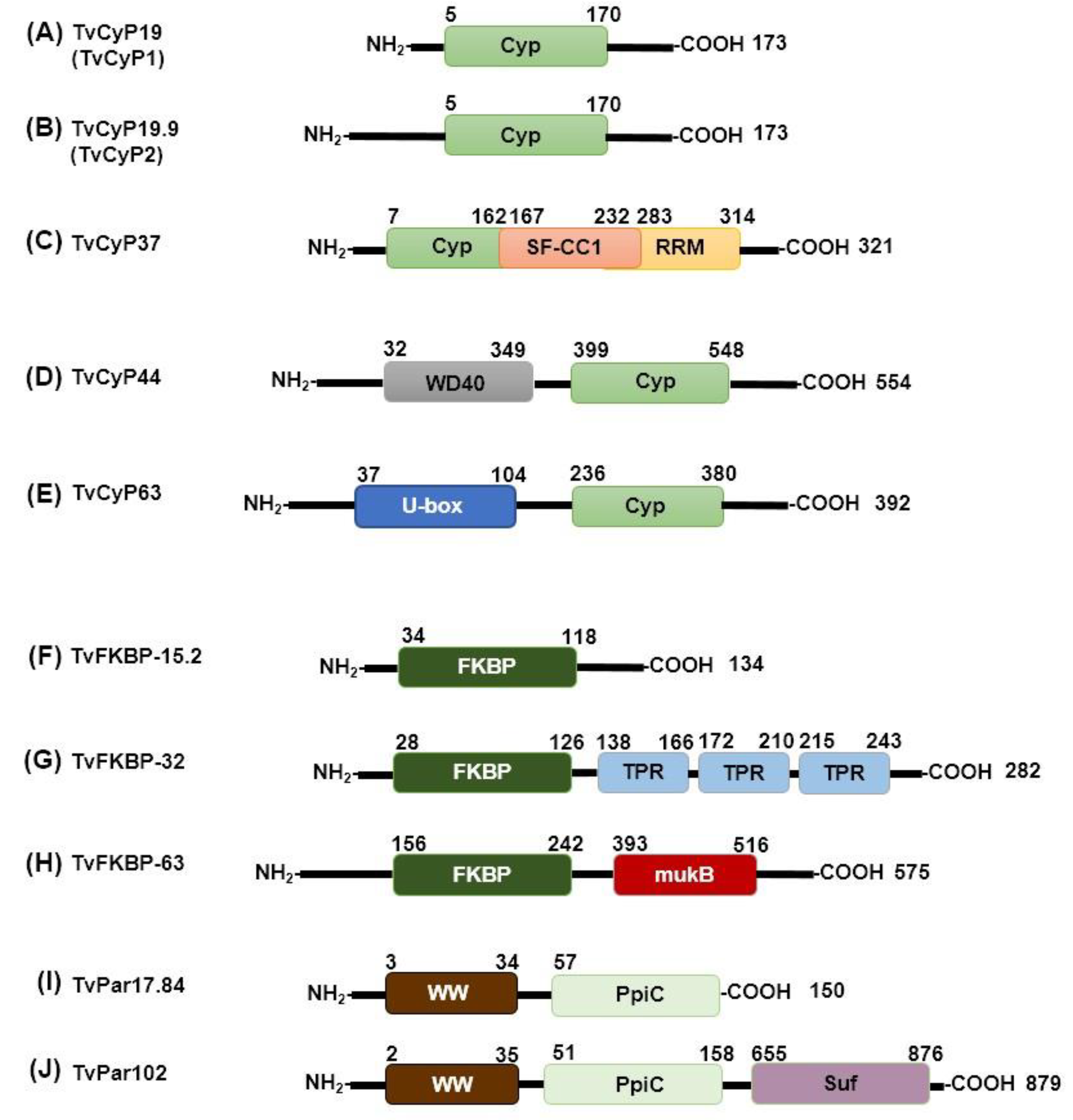

2.1.1. Trichomonas vaginalis

2.1.2. Entamoeba histolytica

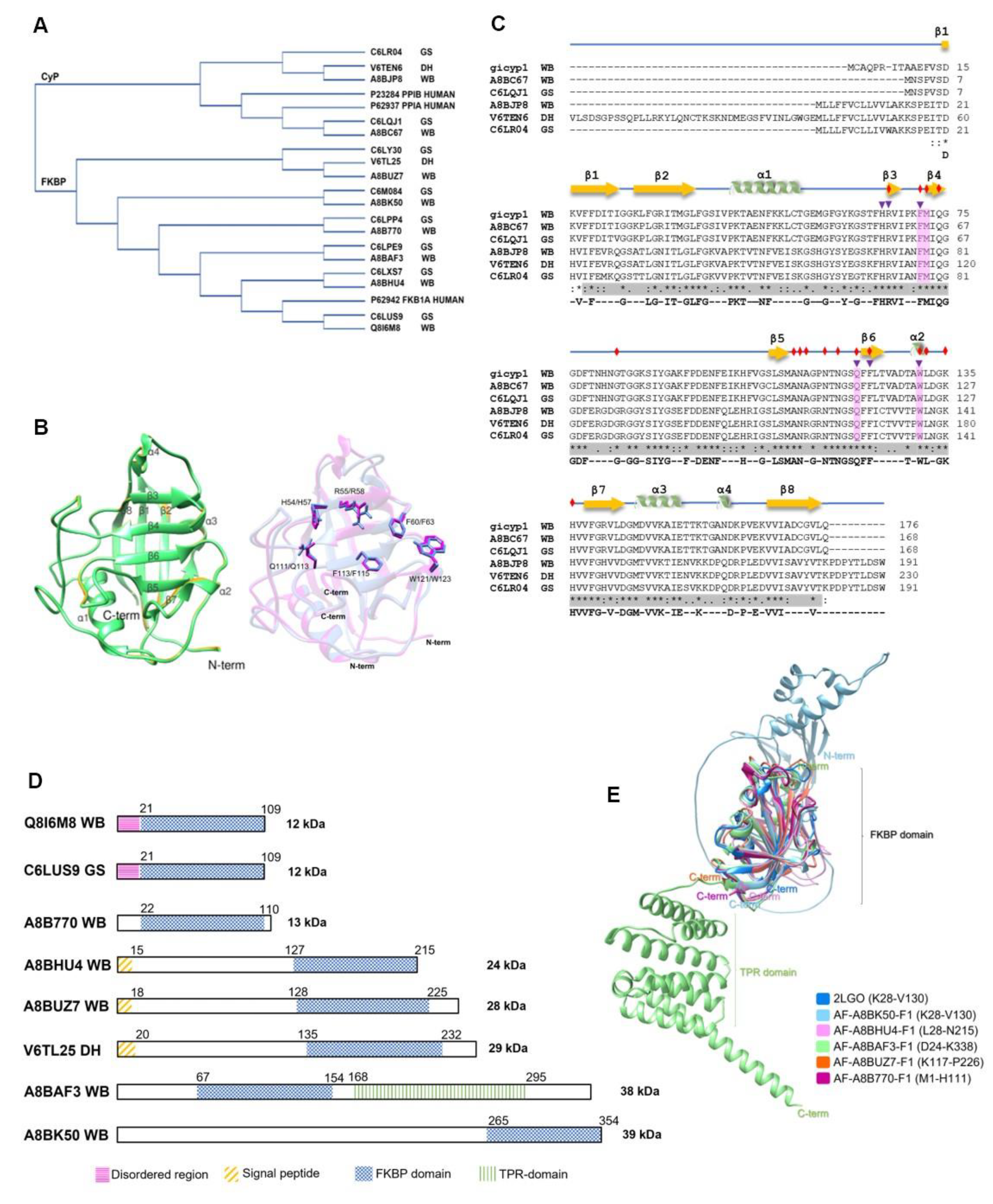

2.1.3. Giardia intestinalis

2.2. Trypanosomatid Parasites

2.2.1. Trypanosoma cruzi and Trypanosoma brucei gambiense

| Parasite | UniProt | TriTrypDB | NCBI | PDB | PPIase name | Localization3 | Function3 | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. cruzi CL Brener | Q4E4L9 | TcCLB.506925.300 (CYPA) |

XP_821578.1 | TcCyP192 | Extracellular space | Promotes ROS production in host cells | [68,76,77,78,80] | |

| Q4DC03 | TcCLB.507009.100 | XP_811912.1 | TcCyP20 | |||||

| Q4DNC9 | TcCLB.507521.70 | XP_815879.1 | 1XO7 | TcCyP212 | [68,78] | |||

| Q4DI85 | TcCLB.504035.70 | XP_814080.1 | TcCyP222 | Mitochondria | Cell death regulation | [68,79] | ||

| Q4CXV1 | TcCLB.506413.80 | XP_806960.1 | TcCyP24 | |||||

| Q4DFL3 | TcCLB.508323.94 | XP_813175.1 | TcCyP25 | [68,78] | ||||

| Q4D4K3 | TcCLB.503885.40 | XP_809302.1 | TcCyP26 | |||||

| Q4CX88 | TcCLB.509499.10 | XP_806737.1 | TcCyP282 | [68,78] | ||||

| Q4DQI8 | TcCLB.505807.10 | XP_816616.1 | TcCyP29 | |||||

| Q4DNS3 | TcCLB.511589.50 | XP_816007.1 | TcCyP30 | Membrane | [43,68] | |||

| Q4DM35 | TcCLB.511577.40 (CYP35) |

XP_815421.1 | TcCyP35 (TcCyP34)2 |

[68,78] | ||||

| Q4DVC9 | TcCLB.511217.120 | XP_818332.1 | TcCyP35.3 (TcCyP35) |

[68] | ||||

| Q4E4G0 | TcCLB.506885.400 (CYP40) |

XP_821542.1 | TcCyP38 (TcCyP40)2 |

[43,68] | ||||

| Q4DG41 | TcCLB.510761.44 | XP_813344.1 | TcCyP42 | Membrane | [43,68] | |||

| Q4D1M5 | TcCLB.504215.10 | XP_808273.1 | TcCyP103 TcCyP110 |

[68] | ||||

| T. cruzi Y | Q09734 | TcYC6_0113560 | CAA49346.1 | 1JVW | TcFKBP222 (TcMIP) |

Extracellular space | Host cell entry/invasion |

[69,70] |

| T. cruzi CL Brener | Q4D5W5 | TcCLB.508169.69 | XP_809772.1 | TcFKBP12 | ||||

| Q4DFL5 | TcCLB.508323.84 | XP_813174.1 | TcFKBP12.2 | |||||

| Q4D7F5 | TcCLB.511731.89 | XP_810317.1 | TcFKBP35 | |||||

| Q4CZN2 | TcCLB.511353.10 | XP_807578.1 | TcFKBP52 | |||||

| Q4CYE6 | TcCLB.507629.39 | XP_807152.1 | TcFKBP93 | |||||

| T. cruzi CL Brener | Q4D8F7 | TcCLB.508567.70 (Pin1) |

XP_810661.1 | TcPar12.62 (TcPin1) |

Cytosol | [72,81] | ||

| Q4D394 | TcCLB.506697.50 | XP_808848.1 | TcPar132 (TcPar14) |

[73] | ||||

| Q4D9J4 | TcCLB.506857.60 (Par45) |

XP_811046.1 | TcPar452 | Nucleus | [73] |

| UniProt | TriTrypDB | NCBI | PPIase name2 | Localization4 | Function4 | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D0A5M6 | Tbg972.11.920 (CYPA) | XP_011779241.1 | TbgCyP19(TbgCyPA) | Cytoplasm, flagellum, and extracellular space | [82,83] | ||

| C9ZYX4 | Tbg972.9.6990 | XP_011776889.1 | TbgCyP20.3 | ||||

| D0A8E1 | Tbg972.11.10610 | XP_011780206.1 | TbgCyP20.5 | ||||

| C9ZIV0 | Tbg.972.2.170 | XP_011771617.1 | TbgCyP21.1 | ||||

| C9ZT99 | Tbg972.7.5450 | XP_011774914.1 | TbgCyP21.2 | Extracellular space | [83] | ||

| C9ZWH7 | Tbg972.8.7100 | XP_011776042.1 | TbgCyP21.4 | ||||

| C9ZRQ0 | Tbg972.7.160 | XP_011774319.1 | TbgCyP24 | ||||

| C9ZSQ5 | Tbg972.7.3760 | XP_011774720.1 | TbgCyP25.55 | ||||

| C9ZNS2 | Tbg972.5.1880 | XP_011773337.1 | TbgCyP25.56 | ||||

| C9ZWA7 | Tbg972.8.6340 | XP_011775972.1 | TbgCyP27.1 | ||||

| C9ZXF5 | Tbg972.9.1740 | XP_011776370.1 | TbgCyP27.4 | ||||

| C9ZQE6 | Tbg972.6.1040 | XP_011773911.1 | TbgCyP29 | ||||

| C9ZVY5 | Tbg972.8.5140 | XP_011775850.1 | TbgCyP30 | ||||

| C9ZUX8 | Tbg972.8.1650 | XP_011775493.1 | TbgCyP33 | ||||

| C9ZYI8 | Tbg972.9.5630 | XP_011776753.1 | TbgCyP38 | Extracellular space | [83] | ||

| C9ZZI1 | Tbg972.9.9060 | XP_011777096.1 | TbgCyP43 | Membrane | [43] | ||

| C9ZIB2 | Tbg972.1.930 | XP_011771345.1 | TbgCyP46 | ||||

| C9ZPQ4 | Tbg972.5.5220 | XP_011773669.1 | TbgCyP58 | Nucleus | [43] | ||

| C9ZZU0 | Tbg972.10.15980 | XP_011778762.1 | TbgCyP100 | ||||

| D0A2I5 | Tbg972.10.5640 | XP_011777743.1 | TbgFKBP12 | ||||

| C9ZSQ4 | Tbg972.7.3750 | XP_011774719.1 | TbgFKBP12.33(TbgFKBP12) | Flagellar pocket | Motility and cytokinesis | [84] | |

| D0A0P0 | Tbg972.10.19020 (MIP) | XP_011779062.1 | TbgFKBP21 | ||||

| D0A0P1 | Tbg972.10.19030 | XP_011779063.1 | TbgFKBP36 | ||||

| D0A0V5 | Tbg972.10.19710 | XP_011779127.1 | TbgFKBP48 | Extracellular space | [83] | ||

| D0A6H9 | Tbg972.11.3980 | XP_011779544.1 | TbgFKBP92 | ||||

| C9ZUI9 | Tbg972.8.300 (Pin1) | XP_011775354.1 | TbgPar123(TbgPin1) | Cytoplasm | [85] | ||

| C9ZKX9 | Tbg972.3.3260 | XP_011772278.1 | TbgPar13(TbgPar14) | [85] | |||

| C9ZRL7 | Tbg972.7.2770 (Par45) | XP_011774600.1 | TbgPar423 | Nucleus | Cell growth | [85] |

2.2.2. Leishmania major and Leishmania donovani

2.3. Apicomplexan Parasites

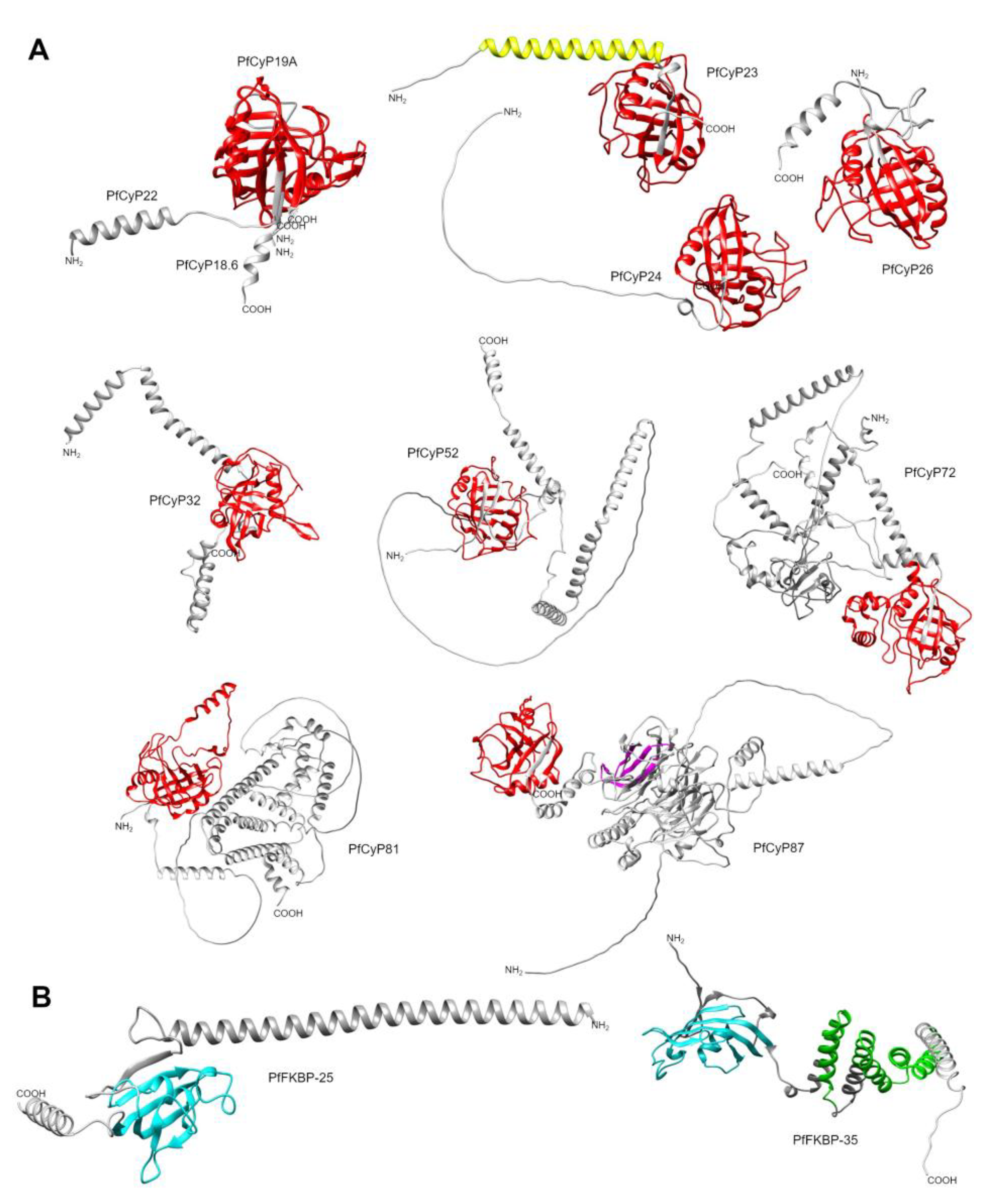

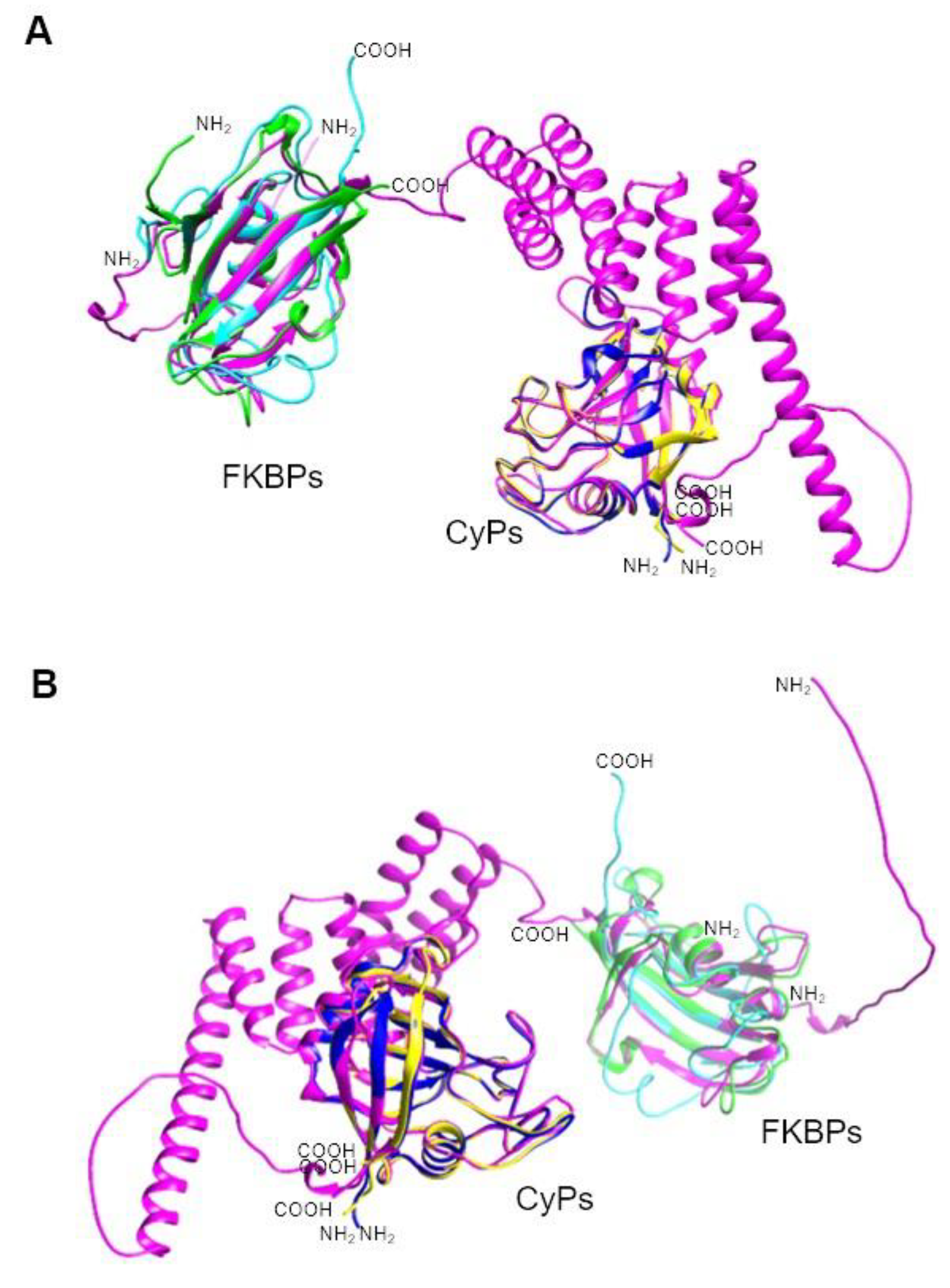

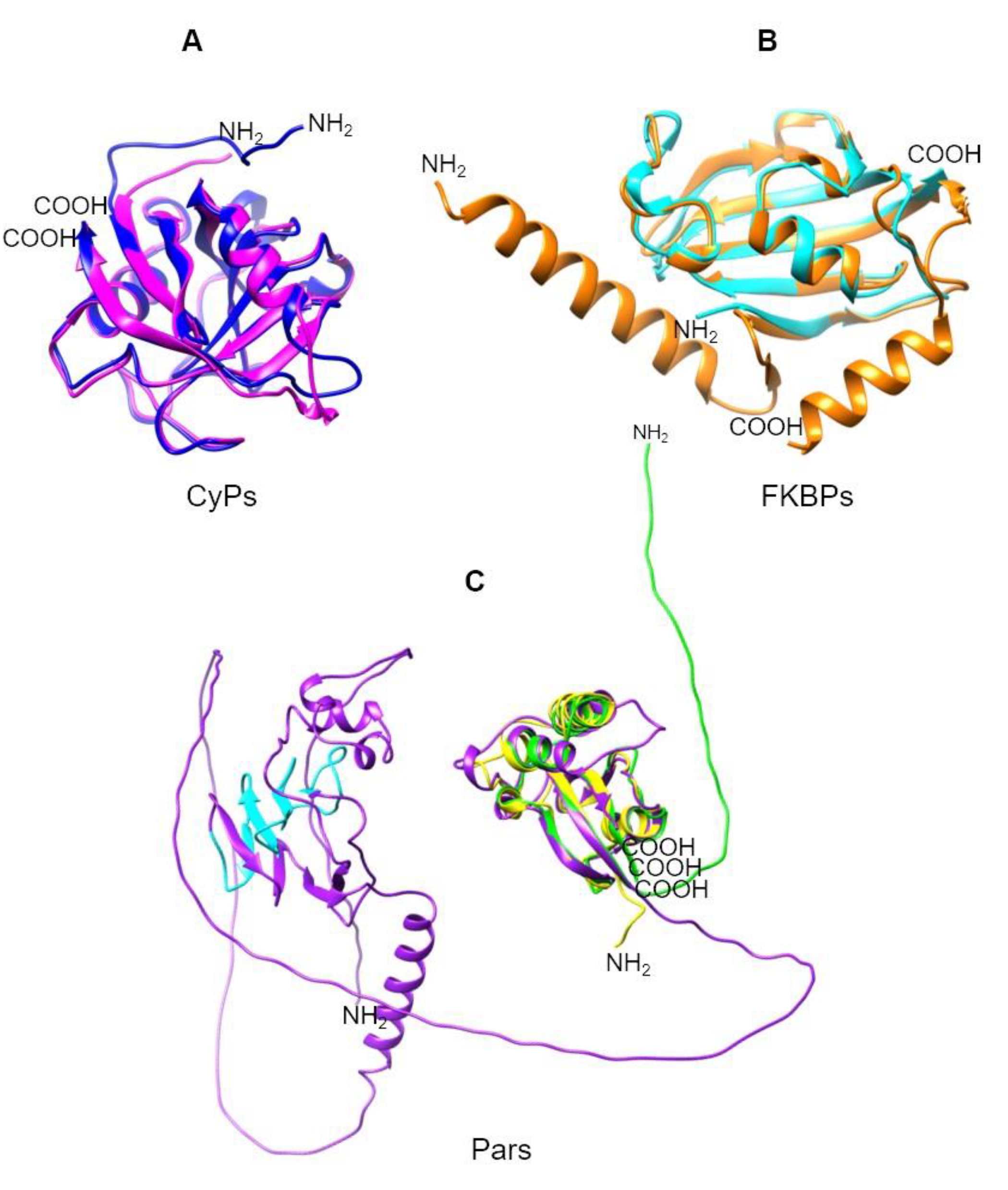

2.3.1. Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax

| UniProt | PlasmoDB | NCBI | PDB | PPIase name | Localization | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A0A1G4HCW7 | PVP01_0916900 (CYP19C) | XP_001615280.1 | PvCyP18.5 | ||||

| A0A1G4HBM6 | PVP01_0818200 (CYP19A) | XP_001614493.1 | PvCyP19 | ||||

| A0A1G4HCM3 | PVP01_0916400 | XP_001615276.1 | PvCyP21 | ||||

| A0A1G4HDR7 | PVP01_1005100 (CYP23) | XP_001613671.1 | PvCyP23 | ||||

| A0A1G4H2Q1 | PVP01_1301700 (CYP26) | XP_001616500.1 | PvCyP26 | ||||

| A0A1G4GR33 | PVP01_0115700 (CYP24) | XP_001608574.1 | PvCyP29 | ||||

| A0A1G4H4X8 | PVP01_1434000 (CYP32) | XP_001617250.1 | PvCyP32 | ||||

| A0A1G4HIV6 | PVP01_1325800 | CAG9475874.1 | PvCyP52 | ||||

| A0A1G4HAY2 | PVP01_0729200 | XP_001614845.1 | PvCyP71 | ||||

| A0A1G4GR20 | PVP01_0117200 (CYP81) | CAG9485095.1 | PvCyP65 | Nucleus | [43] | ||

| A0A1G4HEA6 | PVP01_1023800 (CYP87) | XP_001613274.1 | PvCyP83 | ||||

| A0A1G4H4D0 | PVP01_1414200 | XP_001617060.1 | 4JYS | PvFKBP253 | [108] | ||

| A0A565A3M9 | PVP01_1464500 | XP_001613999.1 | 2KI3 | PvFKBP343(PvFKBP35) | [109,121] |

2.3.2. Toxoplasma gondii

3. Localization and Functions of PPIases in Parasites

4. Recombinant Expression and Purification of PPIases from Clinically Important Protists

| Parasite | PPIasa | UniProt | kDa | pI | Expression system | Purification | Catalytic Efficiency3 |

Inhibition | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Vector |

kcat/Km. |

Inhibitor | IC50 nM4 | |||||||

| T. cruzi | TcCyP19 |

Q9U664 | 18.9 | 8.4 | M15, XL1Blue | pQE30 | IMAC | CsA H-7-94 F-7-62 MeVal-4 |

14.42-18.4 12.54 13.3 15.25 |

[66,77,79,81] | |

| TcCyP21 | Q4DPB9 | 21.1 | 9.1 | BL21 pLysS | pET14 | IMAC | CsA H-7-94 F-7-62 MeVal-4 |

28.74 23.64 25.15 30.04 |

[69,79] | ||

| TcCyP25 | Q9NAT5 | 25.6 | 8.5 | Origami | pRSETA | IMAC | CsA H-7-94 F-7-62 MeVal-4 |

31.7 17.2 17.8 29.98 |

[69,79] | ||

| TcCyP28 | O76990 | 28.4 | 9.7 | BL21 RIL | pET41b | IMAC | CsA H-7-94 F-7-62 MeVal-4 |

13.05 9.16 10.06 13.52 |

[69,79] | ||

| TcCyP34 | K2NAL4 | 33.4 | 9.0 | BL21(DE3) | pRSETA | IMAC | CsA H-7-94 F-7-62 MeVal-4 |

>2005 | [69,79] | ||

| TcCyP38 (TcCyP40) |

Q6V7K6 | 38.4 | 5.7 | M15 | pQE30 | IMAC | CsA H-7-94 F-7-62 MeVal-4 |

>2005 | [69] | ||

| T. brucei | TbgCyP19 (TbCypA) |

D0A5M6 | 18.7 | 8.3 | M15 | pQE30 | IMAC | [83] | |||

| T. vaginalis | TvCyP19 (TvCyP1) |

A2DT06 | 19 | 7.7 | BL21 | pET32a | IMAC, IEX, AC | 7.1 M-1s-1 4.0 M-1s-1 |

CsA | 7.5 | [26,28] |

| TvCyP19.9 (TvCyP2) |

A2DLL4 | 20 | 9.1 | BL21 | pET, pGEX2t pET29b |

IMAC, IEX, AC | 4.5 M-1s-1 | [27,29] | |||

| L. major | LmaCyP19 | O02614 | 19 | 7.7 | M15 | pQE30, pREP4 pET14b, pTYB1 pGEX4T-3 |

IMAC, HIC, AC | 1.5x106 M-1s-1 2.6x106 M-1s-1 |

CsA | Ki=0.53 | [96,97] |

| LmaCyP38 (LmaCyp40) | E9AFV2 | 38.4 | 5.6 | BL21 | pGEX-5X-Strep | AC | [93] | ||||

| L. donovani | LdCyP20.4 (LdCyP) |

Q9U9R3 | 17.7 | 6.9 | BL21 pLysS | pET3a, pQE32 | IMAC | [92,94,99,100] | |||

| T. gondii | TgCyP18 | A0A125YZ79 | 18.3 | 6.9 | BL21 | pET28a | IMAC, AC, SEC, RPC | 1.0x104 M-1s-1 | [130] | ||

| TgCyP20 | S8F7V1 | 19.6 | 6.0 | AC | [126,129] | ||||||

| TgCyP23 | A0A125YL73 | 22.9 | 7.0 | BL21 | pET28a | IMAC, SEC | 3.8x106 M-1s-1 | [130] | |||

| P. falciparum | PfCyP19 (PfCyP19A) |

Q76NN7 | 19 | 8.2 | BL21 | pET-3a, pET22b+ | IMAC | 6.3x106 M-1s-1 1.2x107 M-1s-1 |

CsA CsC CsD Rapamycin FK506 |

10 581 238 >5000 >10000 |

[106,113,114,116,117] |

| PfCyP22 (PfCyP19B) |

Q8IIK8 | 22 | 7.1 | BL21 | pET22b+ | IMAC | 2.3x106 M-1s-1 5.7x106 M-1s-1 |

CsA | 10 | [106,116,117,118] | |

| PfCyP18.6 (PfCyP19C) |

Q8IIK3 | 18.6 | 5.9 | BL21 | pET22b+ | IMAC | [106,114] | ||||

| PfCyP23 | Q8I3I0 | 23.2 | 5.3 | BL21 | pET22b+ | IMAC | [106,114] | ||||

| PfCyP25 (PfCyP24) |

Q8I6S4 | 24.9 | 6.7 | BL21 | pET22b+ | IMAC | [106,109,114,120] | ||||

| PfCyP26 | Q8I621 | 26.4 | 8.5 | BL21 | pET22b+ | IMAC | [106,114] | ||||

| PfCyP32 | Q8I5Q4 | 32.3 | 9.8 | Rosseta | pET22b+ | IMAC | [106,114] | ||||

| PfCyP53 (PfCyP52) |

Q8ILM0 | 52.7 | 7.0 | BL21 | pET22b+ | IMAC | [106,114] | ||||

| E. histolytica | EhCyP18 (EhCyP) |

O15729 | 18.1 | XL1Blue | pTrcHis A | IMAC | CsA | 10 | [46] | ||

| G. intestinalis | GiCyP19 (GiCyP1) |

19 | BL21 | pGEX 4T-1 | AC | CsA | 500 | [56] | |||

| GiCyP18 | A8BC67 | 18 | 8.4 | BL21 | pColdI | IMAC | [64] | ||||

| T. cruzi | TcFKBP22 (TcMIP) |

Q09734 | 22.1 | 6.8 | XL1 Blue | pGEX-2T | AC | 0.745 M-1s-1 | FK506 | 410 | [70,71] |

| T. gondii | TgFCBP57 | Q4VKI5 | 57.2 | 5.5 | BL21(DE3) | pET15b | IMAC | FK506 CsA |

70 750 |

[127] | |

|

P. falciparum |

PfFKBP35 | Q8I4V8 | 34.8 | 5.4 | BL21, TB1 | pMALc2X, pSUMO | IMAC, SEC, AC | 1.7x104 M-1s-1 1x105 M-1s-1 |

FK506 Rapamcyin D44 |

320,260 480 125 |

[108,112,115,121] |

| P. vivax | PvFKBP25 | A0A1G4H4D0 | 25.2 | 9.5 | BL21(DE3) | pNIC28-Bsa4 | IMAC, SEC | [109] | |||

| PvFKBP34 (PvFKBP35) |

A0A565A3M9 | 34 | 6.1 | BL21(DE3) | pSUMO | IMAC, SEC | 1x105 M-1s-1 | FK506 D44 |

160 125 |

[109,121] | |

| G. intestinalis | GiFKBP12 | Q8I6M8 | 12 | 9.2 | BL21(DE3)-R3-RARE | AVA0421 | IMAC, SEC | [59] | |||

| T. cruzi | TcPar12.6 (TcPin1) |

Q4D8F7/ Q4DKA4 |

12.6 | 7.7 | JM109 | pQE30 | IMAC | 3.97x105 M-1s-1 1.54x104 M-1s-1 |

[73,82] | ||

| TcPar13 (TcPar14) |

Q4D394/ Q4E641 |

13.3 | 9.4 | BL21(DE3)-CodonPlus RIL | pET-22b+ | IMAC, SEC | 0.194 M-1s-1 | [74] | |||

| TcPar45 | Q4D9J4/ Q4DH56 |

45.5 | 8.7 | BL21(DE3)-CodonPlus RIL | PET28a | IMAC, SEC | 7.1x103 M-1s-1 | [74] | |||

| T. brucei | TbgPar12 (TbPin1) |

C9ZUI9 | 12.5 | 6 | pET28b | SEC | [86] | ||||

| TbPar42 | C9ZRL7 | 41.7 | 7.1 | pET28b | SEC | [86] | |||||

| L. major | LmaPar13 (LmPIN1) |

Q4QII4 | 12.6 | 7.2 | BL21 | IMAC, SEC | [93,98] | ||||

5. Assays of the Activity of PPIases from Clinically Important Protists

6. Inhibition Assays of rPPIases from Protozoan Parasites

7. Protozoan PPIases Biotechnological Applications

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baneth, G.; Bates, P.A.; Olivieri, A. Host–parasite interactions in vector-borne protozoan infections. European Journal of Protistology 2020, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrester, S.J.; Hall, N. The revolution of whole genome sequencing to study parasites. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology 2014, 195, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G. Peptidyl-Prolyl cis/trans Isomerases and Their Effectors. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English 1994, 33, 1415–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanghanel, J.; Fischer, G. Insights into the catalytic mechanism of peptidyl prolyl cis/trans isomerases. Front Biosci 2004, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, K.P.; Finn, G.; Lee, T.H.; Nicholson, L.K. Prolyl cis-trans isomerization as a molecular timer. Nature Chemical Biology 2007, 3, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, A.; Monaghan, P.; Page, A.P. Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerases (immunophilins) and their roles in parasite biochemistry, host-parasite interaction and antiparasitic drug action. International Journal for Parasitology 2006, 36, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlke, D.; Freund, C.; Leitner, D.; Labudde, D. Statistically significant dependence of the Xaa-Pro peptide bond conformation on secondary structure and amino acid sequence. BMC Structural Biology 2005, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, L.; Christner, C.; Kipping, M.; Schelbert, B.; Rücknagel, K.P.; Grabley, S.; Küllertz, G.; Fischer, G. Selective inactivation of parvulin-like peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerases by juglone. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 5953–5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordens, J.; Janssens, V.; Longin, S.; Stevens, I.; Martens, E.; Bultynck, G.; Engelborghs, Y.; Lescrinier, E.; Waelkens, E.; Goris, J.; Van Hoof, C. The protein phosphatase 2A phosphatase activator is a novel peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans-isomerase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006, 281, 6349–6357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusdottir, A.; Stenmark, P.; Flodin, S.; Nyman, T.; Hammarström, M.; Ehn, M.; Bakali, H.M.A.; Berglund, H.; Nordlund, P. The crystal structure of a human PP2A phosphatase activator reveals a novel fold and highly conserved cleft implicated in protein-protein interactions. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006, 281, 22434–22438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handschumacher, R.; Harding, M.; Rice, J.; Drugge, R.; Speicher, D. Cyclophilin: A specific cytosolic binding protein for Cyclosporin, A. Science 1984, 226, 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Heitman, J. The cyclophilins. Genome Biology 2005, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galat, A. Peptidyl prolyl cis/trans isomerases (Immunophilins): Biological diversity-targets-functions. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 2003, 3, 1315–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, T.L.; Walker, J.R.; Campagna-Slater, V.; Finerty, P.J.; Finerty, P.J.; Paramanathan, R.; Bernstein, G.; Mackenzie, F.; Tempel, W.; Ouyang, H.; Lee, W.H.; Eisenmesser, E.Z.; Dhe-Paganon, S. Structural and biochemical characterization of the human cyclophilin family of peptidyl-prolyl isomerases. PLoS Biology 2010, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michnick, S.W.; Rosen, M.K.; Wandless, T.L.; Karplus, M.; Schreiber, S.L. Solution structure of FKBP, a rotamase enzyme and receptor for FK506 and rapamycin. Science 1991, 252, 836–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duyne, A.D.; Standaert, R.F.; Karplus, P.A.; Schreiber, S.L.; Clardy, J. Atomic structure of FKBP-FK506, an immunophilin-immunosuppressant complex. Science 1991, 252, 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galat, A. Sequence diversification of the FK506-binding proteins in several different genomes. European. Journal of Biochemistry 2000, 267, 4945–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahfeld, J.-U.; Riicknagel, K.P.; Schelbert, B.; Ludwigb, B.; Hackerb, J.; Mannc, K.; Fischer, G. Confirmation of the existence of a third family among peptidyl-prolyl cisltrans isomerases Amino acid sequence and recombinant production of parvulin. FEBS Letters 1994, 352, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahfeld, J.-U.; Schierhornb, A.; Mannc, K.; Fischer, G. A novel peptidyl-prolyl cisltrans isomerase from Escherichia coli. FEBS Letters 1994, 343, 6569. [Google Scholar]

- Rudd, K.E.; Sofia, H.J.; Koonin, E.V.; Plunkett, G.; Lazar, S.; Rouviere, P.E. A new family of peptidyl-prolyl isomerases. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 1995, 20, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Salah, Z.; Alian, A.; Aqeilan, R.I. WW domain-containing proteins: retrospectives and the future. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark 2012, 17, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranganathan, R.; Lu, K.P.; Hunter, T.; Noel, J.P. Structural and functional analysis of the mitotic rotamase Pin1 suggests substrate recognition is phosphorylation dependent. Cell 1997, 89, 875–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaherty, P.T.; Jain, P. Peptidyl prolyl isomerase inhibitors. Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry 2011, 46, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2022. Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. Tomado de: www.cdc.gov/std/trichomonas/stdfact-trichomoniasis. [Revisado el: 26/12/22].

- et al. VEuPathDB: the eukaryotic pathogen, vector and host bioinformatics resource center in 2023. Nucleic Acids Research 2024, 52, D808–D816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, H.M.; Chu, C.H.; Wang, Y.T.; Lee, Y.; Wei, S.Y.; Liu, H.W.; Ong, S.J.; Chen, C.; Tai, J.H. Regulation of nuclear translocation of the Myb1 transcription factor by TvCyclophilin 1 in the protozoan parasite Trichomonas vaginalis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2014, 289, 19120–19136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, H.M.; Huang, Y.H.; Aryal, S.; Liu, H.W.; Chen, C.; Chen, S.H.; Chu, C.H.; Tai, J.H. Endomembrane Protein Trafficking Regulated by a TvCyP2 Cyclophilin in the Protozoan Parasite, Trichomonas vaginalis. Scientific Reports 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.; Lou, Y.C.; Chou, C.C.; Wei, S.Y.; Sadotra, S.; Cho, C.C.; Lin, M.H.; Tai, J.H.; Hsu, C.H.; Chen, C. Structural basis of interaction between dimeric cyclophilin 1 and Myb1 transcription factor in Trichomonas vaginalis. Scientific Reports 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, S.; Hsu, H.M.; Lou, Y.C.; Chu, C.H.; Tai, J.H.; Hsu, C.H.; Chen, C. N-terminal segment of tvcyp2 cyclophilin from trichomonas vaginalis is involved in self-association, membrane interaction, and subcellular localization. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graveley, B.R. A protein interaction domain contacts RNA in the prespliceosome. Mol Cell. 2004, 13, 302–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, T.L.; Walker, J.R.; Ouyang, H.; MacKenzie, F.; Butler-Cole, C.; Newman, E.M.; Eisenmesser, E.Z.; Dhe-Paganon, S. The crystal structure of human WD40 repeat-containing peptidylprolyl isomerase (PPWD1). FEBS Journal 2008, 275, 2283–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maris, C.; Dominguez, C.; Allain, F.H.T. The RNA recognition motif, a plastic RNA-binding platform to regulate post-transcriptional gene expression. FEBS Journal 2005, 272, 2118–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatakeyama, S.; Kei-ichi, I.N. U-box proteins as a new family of ubiquitin ligases. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2003, 302, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohi, M.D.; vander Kooi, C.W.; Rosenberg, J.A.; Chazin, W.J.; Gould, K.L. Structural insights into the U-box, a domain associated with multi-ubiquitination. Nature Structural Biology 2003, 10, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richly H, Rape M, Braun S, Rumpf S, Hoege C, et al. A series of ubiquitin binding factors connects CDC48/p97 to substrate multiubiquitylation and proteasomal targeting. Cell 2005, 120, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Min, J. (2011). Structure and function of WD40 domain proteins. In Protein and Cell (Vol. 2, Issue 3, pp. 202–214). Higher Education Press Limited Company. [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, L.D.; Regan, L. TPR proteins: The versatile helix. In Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2003, 28, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musacchio, A.; Zawadzka, K.; Zawadzki, P.; Baker, R.; Rajasekar, K.v.; Wagner, F.; Sherratt, D.J.; Arciszewska, L.K. MukB ATPases are regulated independently by the N-and C-terminal domains of MukF kleisin. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audibert, A.A.; Simonelig, M. (1998). Autoregulation at the level of mRNA 3 end formation of the suppressor of forked gene of Drosophila melanogaster is conserved in Drosophila virilis. In Genetics (Vol. 95). www.pnas.org.

- The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, D523–D531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koichiro Tamura, Glen Stecher, and Sudhir Kumar. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 11. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeira F, Pearce M, Tivey ARN, et al. Search and sequence analysis tools services from EMBL-EBI in 2022. Nucleic Acids Research.

- Gaudet, P.; Livstone, M.S.; Lewis, S.E.; Thomas, P.D. Phylogenetic-based propagation of functional annotations within the Gene Ontology consortium. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2011, 12, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán, P.; Serrano-Vázquez, A.; Rojas-Velázquez, L.; González, E.; Pérez-Juárez, H.; Hernández, E.G. . & Ximénez, C. Amoebiasis: Advances in Diagnosis, Treatment, Immunology Features and the Interaction with the Intestinal Ecosystem. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 11755. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.; Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R.A.; Yang, M.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, C.; Lanczycki, C.J.; Marchler-Bauer, A. CDD/SPARCLE: the conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D265–D268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ostoa-Saloma, P.; Carrero, J.C.; Petrossian, P.; Hérió, P.; Landa, A.; Laclette, J.P. Cloning, characterization and functional expression of a cyclophilin of Entamoeba histolytica. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology 2000, 107, https://doi/10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00190–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matena, A.; Rehic, E.; Hönig, D.; Kamba, B.; Bayer, P. Structure and function of the human parvulins Pin1 and Par14/17. Biological Chemistry 2018, 399, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, R.D. Giardia duodenalis: Biology and pathogenesis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2021, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savioli, L.; Smith, H.; Thompson, A. Giardia and Cryptosporidium join the “Neglected Diseases Initiative. ” Trends in Parasitology 2006, 22, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzén, O.; Jerlström-Hultqvist, J.; Castro, E.; Sherwood, E.; Ankarklev, J.; Reiner, D.S.; Palm, D.; Andersson, J.O.; Andersson, B.; Svärd, S.G. Draft genome sequencing of Giardia intestinalis assemblage B isolate GS: Is human giardiasis caused by two different species? PLoS Pathogens 2009, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankarklev, J.; Franzén, O.; Peirasmaki, D.; Jerlström-Hultqvist, J.; Lebbad, M.; Andersson, J.; Andersson, B.; Svärd, S.G. Comparative genomic analyses of freshly isolated Giardia intestinalis assemblage A isolates. BMC Genomics 2015, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajaczkowski, P.; Lee, R.; Fletcher-Lartey, S.M.; Alexander, K.; Mahimbo, A.; Stark, D.; Ellis, J.T. The controversies surrounding Giardia intestinalis assemblages A and B. Current Research in Parasitology and Vector-Borne Diseases 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, H.G.; McArthur, A.G.; Gillin, F.D.; Aley, S.B.; Adam, R.D.; Olsen, G.J.; Best, A.A.; Cande, W.Z.; Chen, F.; Cipriano, M.J.; Davids, B.J.; Dawson, S.C.; Elmendorf, H.G.; Hehl, A.B.; Holder, M.E.; Huse, S.M.; Kim, U.U.; Lasek-Nesselquist, E.; Manning, G.; … Sogin, M.L. Genomic minimalism in the early diverging intestinal parasite Giardia lamblia. Science 2007, 317, 1921–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, R.D.; Dahlstrom, E.W.; Martens, C.A.; Bruno, D.P.; Barbian, K.D.; Ricklefs, S.M.; Hernandez, M.M.; Narla, N.P.; Patel, R.B.; Porcella, S.F.; Nash, T.E. Genome sequencing of Giardia lamblia genotypes A2 and B isolates (DH and GS) and comparative analysis with the genomes of Genotypes A1 and E (WB and pig). Genome Biology and Evolution 2013, 5, 2498–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Lu, S.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R.A.; Yang, M.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, C.; Lanczycki, C.J.; Marchler-Bauer, A. The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, D384–D388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.-S.; Kong, H.-H.; Chung, D.-I. Cloning and characterization of Giardia intestinalis cyclophilin. The Korean Journal of Parasitology 2002, 40, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galat, A. Peptidylprolyl isomerases as in vivo carriers for drugs that target various intracellular entities. Biomolecules 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Research 2000, 28. http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/status.html. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchko, G.W.; Hewitt, S.N.; Van Voorhis, W.C.; Myler, P.J. Solution structure of a putative FKBP-type peptidyl-propyl cis-trans isomerase from Giardia lamblia. Journal of Biomolecular NMR 2013, 57, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, F.; Wilm, A.; Dineen, D.G.; Gibson, T.J.; Karplus, K.; Li, W.; Lopez, R.; McWilliam, H.; Remmert, M.; Söding, J.; Thompson, J.D.; Higgins, D.G. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Molecular Systems Biology 2011, 7, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; Bridgland, A.; Meyer, C.; Kohl, S.A.A.; Ballard, A.J.; Cowie, A.; Romera-Paredes, B.; Nikolov, S.; Jain, R.; Adler, J.; … Hassabis, D. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera - A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma’ayeh, S.Y.; Liu, J.; Peirasmaki, D.; Hörnaeus, K.; Bergström Lind, S.; Grabherr, M.; Bergquist, J.; Svärd, S.G. Characterization of the Giardia intestinalis secretome during interaction with human intestinal epithelial cells: The impact on host cells. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Fang, R.; Zhu, W.; Wu, J.; Li, X.; Patankar, J.V.; Li, W. Giardia duodenalis and its secreted ppib trigger inflammasome activation and pyroptosis in macrophages through TLR4-induced ROS signaling and A20-mediated NLRP3 deubiquitination. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. (2007). Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2947–2948.

- World Health Organization. (2023). Trypanosomiasis, human African (sleeping sickness). Retrieved August 24, 2023, from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/trypanosomiasis-human-african-(sleeping-sickness).

- World Health Organization. (2023). Chagas disease (also known as American trypanosomiasis). Retrieved August 24, 2023, from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chagas-disease-(american-trypanosomiasis).

- El-Sayed, N.M.; Myler, P.J.; Blandin, G.; Berriman, M.; Crabtree, J.; Aggarwal, G.; Caler, E.; Renauld, H.; Worthey, E.A.; Hertz-Fowler, C.; Ghedin, E.; Peacock, C.; Bartholomeu, D.C.; Haas, B.J.; Tran, A.N.; Wortman, J.R.; Alsmark, U.C.M.; Angiuoli, S.; Anupama, A.; … Hall, N. Comparative genomics of trypanosomatid parasitic protozoa. Science 2005, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potenza, M.; Galat, A.; Minning, T.A.; Ruiz, A.M.; Duran, R.; Tarleton, R.L.; Marín, M.; Fichera, L.E.; Búa, J. Analysis of the Trypanosoma cruzi cyclophilin gene family and identification of Cyclosporin A binding proteins. Parasitology 2006, 132, 867–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, A.; Ruiz-Cabello, F.; Fernández-Cano, A.; Stock, R.P.; Gonzalez, A. Secretion by Trypanosoma cruzi of a peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase involved in cell infection. EMBO Journal 1995, 14, 2483–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira PJ, Vega MC, González-Rey E, Fernández-Carazo R, Macedo-Ribeiro S, Gomis-Rüth FX, González A, Coll, M. Trypanosoma cruzi macrophage infectivity potentiator has a rotamase core and a highly exposed alpha-helix. EMBO Rep. 2002, 3, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Truebestein, L.; Leonard, T.A. Coiled-coils: The long and short of it. BioEssays 2016, 38, 903–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erben, E.D.; Daum, S.; Téllez-Iñón, M.T. The Trypanosoma cruzi PIN1 gene encodes a parvulin peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase able to replace the essential ESS1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology 2007, 153, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erben, E.D.; Valguarnera, E.; Nardelli, S.; Chung, J.; Daum, S.; Potenza, M.; Schenkman, S.; Téllez-Iñón, M.T. Identification of an atypical peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase from trypanosomatids. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Cell Research 2010, 1803, 1028–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durocher, D.; Jackson, S.P. The FHA domain. FEBS Letters 2002, 513, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.P.; Sanders, M.; Berry, A.; McQuillan, J.; Aslett, M.A.; Quail, M.A.; Chukualim, B.; Capewell, P.; Macleod, A.; Melville, S.E.; Gibson, W.; David Barry, J.; Berriman, M.; Hertz-Fowler, C. The genome sequence of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, causative agent of chronic human African Trypanosomiasis. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2010, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Búa, J.; Aslund, L.; Pereyra, N.; García, G.A.; Bontempi, E.J.; Ruiz, A.M. Characterisation of a cyclophilin isoform in Trypanosoma cruzi. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2001, 200, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedroso dos Santos, G.; Abukawa, F.M.; Souza-Melo, N.; Alcântara, L.M.; Bittencourt-Cunha, P.; Moraes, C.B.; … Schenkman, S. Cyclophilin 19 secreted in the host cell cytosol by Trypanosoma cruzi promotes ROS production required for parasite growth. Cellular Microbiology. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Búa, J.; Fichera, L.E.; Fuchs, A.G.; Potenza, M.; Dubin, M.; Wenger, R.O.; Moretti, G.; Scabone, C.M.; Ruiz, A.M. Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi effects of cyclosporin A derivatives: Possible role of a P-glycoprotein and parasite cyclophilins. Parasitology 2008, 135, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustos, P.L.; Volta, B.J.; Perrone, A.E.; Milduberger, N.; Búa, J. A homolog of cyclophilin D is expressed in Trypanosoma cruzi and is involved in the oxidative stress–damage response. Cell Death Discovery 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer-Santos, E.; Aguilar-Bonavides, C.; Rodrigues, S.P.; Cordero, E.M.; Marques, A.F.; Varela-Ramirez, A.; Choi, H.; Yoshida, N.; Da Silveira, J.F.; Almeida, I.C. Proteomic analysis of Trypanosoma cruzi secretome: Characterization of two populations of extracellular vesicles and soluble proteins. Journal of Proteome Research 2013, 12, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erben, E.D.; Nardelli, S.C.; De Jesus, T.C.L.; Schenkman, S.; Tellez-Iñon, M.T. Trypanosomatid pin1-type peptidyl-prolyl isomerase is cytosolic and not essential for cell proliferation. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 2013, 60, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellé, R.; McOdimba, F.; Chuma, F.; Wasawo, D.; Pearson, T.W.; Murphy, N.B. The African trypanosome cyclophilin A homologue contains unusual conserved central and N-terminal domains and is developmentally regulated. Gene 2002, 290, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, A.; Hirtz, C.; Bécue, T.; Bellard, E.; Centeno, D.; Gargani, D.; Rossignol, M.; Cuny, G.; Peltier, J.-B. Exocytosis and protein secretion in Trypanosoma. BMC Microbiology 2010, 10, https://doi/10.1186/1471-2180-10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasseur, A.; Rotureau, B.; Vermeersch, M.; Blisnick, T.; Salmon, D.; Bastin, P.; Pays, E.; Vanhamme, L.; Pérez-Morgaa, D. Trypanosoma brucei FKBP12 differentially controls motility and cytokinesis in procyclic and bloodstream forms. Eukaryotic Cell 2013, 12, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, J.Y.; Lai, C.Y.; Tan, L.C.; Yang, D.; He, C.Y.; Liou, Y.C. Functional characterization of two novel parvulins in Trypanosoma brucei. FEBS Letters 2010, 584, 2901–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2023. Leishmaniasis. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis.

- Burza, S.; Croft, S.L.; Boelaert, M. Leishmaniasis. The Lancet 2018, 392, 951–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivens, A.C.; Peacock, C.S.; Worthey, E.A.; Murphy, L.; Aggarwal, G.; Berriman, M.; Sisk, E.; Rajandream, M.-A.; Adlem, E.; Aert, R.; Anupama, A.; Apostolou, Z.; Attipoe, P.; Bason, N.; Bauser, C.; Beck, A.; Beverley, S.M.; Bianchettin, G.; Borzym, K.; … Myler, P.J. The genome of the kinetoplastid parasite, Leishmania major. Science 2005, 309, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downing, T.; Imamura, H.; Decuypere, S.; Clark, T.G.; Coombs, G.H.; Cotton, J.A.; Hilley, J.D.; De Doncker, S.; Maes, I.; Mottram, J.C.; Quail, M.A.; Rijal, S.; Sanders, M.; Schönian, G.; Stark, O.; Sundar, S.; Vanaerschot, M.; Hertz-Fowler, C.; Dujardin, J.C.; Berriman, M. Whole genome sequencing of multiple Leishmania donovani clinical isolates provides insights into population structure and mechanisms of drug resistance. Genome Research 2011, 21, 2143–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoerauf, A.; Rascher, C.; Bang, R.; Pahl, A.; Solbach, W.; Brune, K.; Rö llinghoff, M.; Bang, H. Host-cell cyclophilin is important for the intracellular replication of Leishmania major. Molecular Microbiology 1997, 24, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.; Delhi, P.; Sinha, K.M.; Banerjee, R.; Datta, A.K. Lack of abundance of cytoplasmic cyclosporin A-binding protein renders free-living Leishmania donovani resistant to Cyclosporin A. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 19294–19300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yau, W.L.; Blisnick, T.; Taly, J.F.; Helmer-Citterich, M.; Schiene-Fischer, C.; Leclercq, O.; Li, J.; Schmidt-Arras, D.; Morales, M.A.; Notredame, C.; Romo, D.; Bastin, P.; Späth, G.F. Cyclosporin A treatment of Leishmania donovani reveals stage-specific functions of cyclophilins in parasite proliferation and viability. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2010, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venugopal, V.; Sen, B.; Datta, A.K.; Banerjee, R. Structure of cyclophilin from Leishmania donovani at 1.97 Å resolution. Acta Crystallographica Section F: Structural Biology and Crystallization Communications 2007, 63, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soufari, H.; Waltz, F.; Parrot, C.; Durrieu-Gaillard, S.; Bochler, A.; Kuhn, L.; Sissler, M.; Hashem, Y.; Protéomique, P. Structure of the mature kinetoplastids mitoribosome and insights into its large subunit biogenesis. PNAS 2020, 117, 29851–29861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko, V.; Xue, Z.; Sherry, B.; Bukrinsky, M. Functional analysis of Leishmania major cyclophilin. International Journal for Parasitology 2008, 38, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascher, C.; Pahl, A.; Pecht, A.; Brune, K.; Solbach, W.; Bang, H. Leishmania major parasites express cyclophilin isoforms with an unusual interaction with calcineurin. Biochem. J 1998, 334, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, G.; Ghosh, S.; Raghuraman, H.; Banerjee, R. Probing conformational transitions of PIN1 from L. major during chemical and thermal denaturation. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 154, 904–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, A.; Das, I.; Datta, R.; Sen, B.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Mandal, C.; Datta, A.K. A single-domain cyclophilin from Leishmania donovani reactivates soluble aggregates of adenosine kinase by isomerase-independent chaperone function. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 47451–47460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Basu, S.; Datta, A.K.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Banerjee, R.; Dasgupta, D. Equilibrium unfolding of cyclophilin from Leishmania donovani: Characterization of intermediate states. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2014, 69, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, B.; Venugopal, V.; Chakraborty, A.; Datta, R.; Dolai, S.; Banerjee, R.; Datta, A.K. Amino acid residues of Leishmania donovani cyclophilin key to interaction with its adenosine kinase: Biological implications. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 7832–7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2023). Malaria. Retrieved August 24 2023,from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria.

- Auburn, S.; Böhme, U.; Steinbiss, S.; Trimarsanto, H.; Hostetler, J.; Sanders, M.; Gao, Q.; Nosten, F.; Newbold, C.I.; Berriman, M.; Price, R.N.; Otto, T.D. A new Plasmodium vivax reference sequence with improved assembly of the subtelomeres reveals an abundance of pir genes. Wellcome Open Research 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neafsey, D.E.; Galinsky, K.; Jiang, R.H.Y.; Young, L.; Sykes, S.M.; Saif, S.; Gujja, S.; Goldberg, J.M.; Young, S.; Zeng, Q.; Chapman, S.B.; Dash, A.P.; Anvikar, A.R.; Sutton, P.L.; Birren, B.W.; Escalante, A.A.; Barnwell, J.W.; Carlton, J.M. The malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax exhibits greater genetic diversity than Plasmodium falciparum. Nature Genetics 2012, 44, 1046–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlton, J.M.; Das, A.; Escalante, A.A. Genomics, population genetics and evolutionary history of Plasmodium vivax. Advances in Parasitology 2013, 81, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín-Menéndez, A.; Bell, A. Overexpression, purification and assessment of cyclosporin binding of a family of cyclophilins and cyclophilin-like proteins of the human malarial parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Protein Expression and Purification 2011, 78, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedadi M, Lew J, Artz J, Amani M, Zhao Y, Dong A, Wasney GA, Gao M, Hills T, Brokx S, Qiu W, Sharma S, Diassiti A, Alam Z, Melone M, Mulichak A, Wernimont A, Bray J, Loppnau P, Plotnikova O, Newberry K, Sundararajan E, Houston S, Walker J, Tempel W, Bochkarev A, Kozieradzki I, Edwards A, Arrowsmith C, Roos D, Kain K, Hui, R. Genome-scale protein expression and structural biology of Plasmodium falciparum and related Apicomplexan organisms. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007, 151, 100–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, B.K.; Ye, H.; Hye, R.Y.; Ho, S.Y. Solution structure of FK506 binding domain (FKBD) of Plasmodium falciparum FK506 binding protein 35 (PfFKBP35). Proteins: Structure, Function and Genetics 2008, 70, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S.; Austin, D.; Harikishore, A.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Baek, K.; Yoon, H.S. Crystal structure of Plasmodium vivax FK506-binding protein 25 reveals conformational changes responsible for its noncanonical activity. Proteins: Structure, Function and Bioinformatics 2014, 82, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alag, R.; Qureshi, I.A.; Bharatham, N.; Shin, J.; Lescar, J.; Yoon, H.S. NMR and crystallographic structures of the FK506 binding domain of human malarial parasite Plasmodium vivax FKBP35. Protein Science 2010, 19, 1577–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajan, S.; Yoon, H.S. Structural insights into Plasmodium PPIases. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.R.; Kang, C.B.; Chia, J.; Tang, K.; Yoon, H.S. Expression, purification, and molecular characterization of Plasmodium falciparum FK506-binding protein 35 (PfFKBP35). Protein Expression and Purification 2007, 53, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, M.R.; Hall, D.R.; Berriman, M.; Nunes, J.A.; Leonard, G.A.; Fairlamb, A.H.; Hunter, W.N. The three-dimensional structure of a Plasmodium falciparum cyclophilin in complex with the potent anti-malarial cyclosporin A. Journal of Molecular Biology 2000, 298, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín-Menéndez, A.; Monaghan, P.; Bell, A. A family of cyclophilin-like molecular chaperones in Plasmodium falciparum. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology 2012, 184, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Adams, B.; Musiyenko, A.; Shulyayeva, O.; Barik, S. The FK506-binding protein of the malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, is a FK506-sensitive chaperone with FK506-independent calcineurin-inhibitory activity. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology 2005, 141, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berriman, M.; Fairlamb, A.H. Detailed characterization of a cyclophilin from the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Biochemical Journal 1998, 334, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavigan, C.S.; Kiely, S.P.; Hirtzlin, J.; Bell, A. Cyclosporin-binding proteins of Plasmodium falciparum. International Journal for Parasitology 2003, 33, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirtzlin, J.; Farber, P.M.; Franklin, R.M.; Bell, A. Molecular and biochemical characterization of a Plasmodium falciparum cyclophilin containing a cleavable signal sequence. European Journal of Biochemistry 1995, 232, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Craig, A. Comparative proteomic analysis of metabolically labelled proteins from Plasmodium falciparum isolates with different adhesion properties. Malaria Journal 2006, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G.R. Cloning and characterization of a Plasmodium falciparum cyclophilin gene that is stage-specifically expressed. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology 1995, 73, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, P.; Bell, A. A Plasmodium falciparum FK506-binding protein (FKBP) with peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase and chaperone activities. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology 2005, 139, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alag, R.; Shin, J.; Yoon, H.S. NMR assignments of the FK506-binding domain of FK506-binding protein 35 from Plasmodium vivax. Biomolecular NMR Assignments 2009, 3, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and prevention. (2023).Toxoplasmosis. Retrieved , 2023. from:https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/toxoplasmosis/index. 23 August.

- Kim, K.; Weiss, L.M. Toxoplasma: the next 100 years. Microbes and Infection 2008, 10, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langosch, D. and Arkin, I.T. (), Interaction and conformational dynamics of membrane-spanning protein helices. Protein Science 2009, 18, 1343–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High, K.P.; Joiner, K.A.; Handschumacher, R.E. Isolation, cDNA sequences, and biochemical characterization of the major cyclosporin-binding proteins of Toxoplasma gondii. The Journal of Biochemical Chemistry 1994, 269, 9105–9112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, B.; Musiyenko, A.; Kumar, R.; Barik, S. A novel class of dual-family immunophilins. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, 24308–24314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.M.; Bannai, H.; Xuan, X.; Nishikawa, Y. Toxoplasma gondii cyclophilin 18-mediated production of nitric oxide induces bradyzoite conversion in a CCR5-dependent manner. Infection and Immunity 2009, 77, 3686–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliberti, J.; Valenzuela, J.G.; Carruthers, V.B.; Hieny, S.; Andersen, J.; Charest, H.; Sousa, C.R.; Fairlamb, A.; Ribeiro, J.M.; Sher, A. Molecular mimicry of a CCR5 binding-domain in the microbial activation of dendritic cells. Nature Immunology 2003, 4, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favretto, F.; Jiménez-Faraco, E.; Conter, C.; Dominici, P.; Hermoso, J.A.; Astegno, A. Structural basis for cyclosporin isoform-specific inhibition of cyclophilins from Toxoplasma gondii. ACS Infectious Diseases 2023, 9, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubourg, A.; Xia, D.; Winpenny, J.P.; Al Naimi, S.; Bouzid, M.; Sexton, D.W.; Wastling, J.M.; Hunter, P.R.; Tyler, K.M. Giardia secretome highlights secreted tenascins as a key component of pathogenesis. GigaScience. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, M.M.; Karafova, A.; Kamysz, W.; Schenkman, S.; Pelle, R.; McGwire, B.S. Secreted trypanosome cyclophilin inactivates lytic insect defense peptides and induces parasite calcineurin activation and infectivity. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2013, 288, 8772–8784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rêgo, J.V.; Duarte, A.P.; Liarte, D.B.; de Carvalho Sousa, F.; Barreto, H.M.; Búa, J.; Romanha, A.J.; Rádis-Baptista, G.; Murta, S.M.F. Molecular characterization of cyclophilin (TcCyP19) in Trypanosoma cruzi populations susceptible and resistant to benznidazole. Experimental Parasitology 2015, 148, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, B.K.; Varikuti, S.; Verma, C.; Shivahare, R.; Bishop, N.; Dos Santos, G.P.; McDonald, J.; Sur, A.; Myler, P.J.; Schenkman, S.; Satoskar, A.R.; McGwire, B.S. Immunization with a Trypanosoma cruzi cyclophilin-19 deletion mutant protects against acute Chagas disease in mice. Npj Vaccines 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrone, A.E.; Pinillo, M.; Rial, M.S.; Fernández, M.; Milduberger, N.; González, C.; Bustos, P.L.; Fichera, L.E.; Laucella, S.A.; Albareda, M.C.; Búa, J. Trypanosoma cruzi secreted cyclophilin TcCyP19 as an early marker for trypanocidal treatment efficiency. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 11875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustos, P.L.; Perrone, A.E.; Milduberger, N.A.; Búa, J. Improved immuno-detection of a low-abundance cyclophilin allows the confirmation of its expression in a protozoan parasite. Immunochemistry & Immunopathology 2015, 01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa-Pereira, P.J.; Vega, M.C.; González-Rey, E.; Fernández-Carazo, R.; Macedo-Ribeiro, S.; Gomis-Rüth, F.X.; González, A.; Coll, M. Trypanosoma cruzi macrophage infectivity potentiator has a rotamase core and a highly exposed α-helix. EMBO Reports 2002, 3, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoller, G.; Rücknagel, K.P.; Nierhaus, K.H.; Schmid, F.X.; Fischer, G.; Rahfeld, J.U. A ribosome-associated peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase identified as the trigger factor. EMBO Journal 1995, 14, 4939–4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludlam, A.V.; Moore, B.A.; Xu, Z. The crystal structure of ribosomal chaperone trigger factor from Vibrio cholerae. PNAS 2004, 101, 13436–13441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Sen, B.; Datta, R.; Datta, A.K. Isomerase-independent chaperone function of cyclophilin ensures aggregation prevention of adenosine kinase both in vitro and under in vivo conditions. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 11862–11872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, M.A.; Watanabe, R.; Laurent, C.; Lenormand, P.; Rousselle, J.C.; Namane, A.; Späth, G.F. Phosphoproteomic analysis of Leishmania donovani pro- and amastigote stages. Proteomics 2008, 8, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.A.; Watanabe, R.; Dacher, M.; Chafey, P.; Osorio, Y. Fortéa, J.; Scott, D.A.; Beverley, S.M.; Ommen, G.; Clos, J.; Hem, S.; Lenormand, P.; Rousselle, J.C.; Namane, A.; Späth, G.F. Phosphoproteome dynamics reveal heat-shock protein complexes specific to the Leishmania donovani infectious stage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2010, 107, 8381–8386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leneghan, D.; Bell, A. Immunophilin-protein interactions in Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology 2015, 142, 1404–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarovinsky, F.; Andersen, J.F.; King, L.R.; Caspar, P.; Aliberti, J.; Golding, H.; Sher, A. Structural determinants of the anti-HIV activity of a CCR5 antagonist derived from Toxoplasma gondii. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 53635–53642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Robledo, J.A.; Vasta, G.R. Production of recombinant proteins from protozoan parasites. Trends in Parasitology 2010, 26, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, Á.P.; Calvo, E.P.; Wasserman, M.; Chaparro-Olaya, J. Production of recombinant proteins from Plasmodium falciparum in Escherichia coli. Biomedica 2016, 36, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, G.; Bang, H.; Mech, C. Nachweis einer Enzymkatalyse für die cis-trans-Isomerisierung der Peptidbindung in prolinhaltigen Peptiden. Biomed Biochim Acta 1984, 43, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kofron, J.L.; Kuzmic, P.; Kishore, V.; Colón-Bonilla, E.; Rich, D.H. Determination of kinetic constants for peptidyl prolyl cis-trans isomerase by an improved spectrophotometric assay. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 6127–6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.K.; Stein, R.L. Substrate specificities of the peptidyl prolyl cis-trans isomerase activities of distinct enzymes cyclophilin and FK-506 binding protein: Evidence for the existence of a family of distinct enzymes. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 3813–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siekierka, J.; Hung, S.; Poe, M.; Lin, C.; Sigal, N. A cytosolic binding protein for the immunosuppressant FK506 has peptidyl-prolyl isomerase activity but is distinct from cyclophilin. Letters to Nature 1989, 341, 755–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ünal, C.M.; Steinert, M. Microbial peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerases (PPIases): Virulence factors and potential alternative drug targets. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2014, 78, 544–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, K.; Kakalis, L.T.; Anderson, K.S.; Armitage, I.M.; Kandschumacher, R.E.; Handschumacher, R.E. Expression of human cyclophilin-40 and the effect of the His141+Trp mutation on catalysis and cyclosporin A binding. European Journal of Biochemistry 1995, 229, https://doi/10.1111/j.1432–10331995tb20454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connern, C.P.; Halestrap, A.P. Purification and N-terminal sequencing of peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase from rat liver mitochondrial matrix reveals the existence of a distinct mitochondrial cyclophilin. Biochemical Journal 1992, 284, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harikishore, A.; Niang, M.; Rajan, S.; Preiser, P.R.; Yoon, H.S. Small molecule plasmodium FKBP35 inhibitor as a potential antimalaria agent. Scientific Reports 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunyak, B.M.; Gestwicki, J.E. Peptidyl-proline isomerases (PPIases): Targets for natural products and natural product-inspired compounds. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2016, 59, 9622–9644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golding, H.; Aliberti, J.; King, L.R.; Manischewitz, J.; Andersen, J.; Valenzuela, J.; Landau, N.R.; Sher, A. Inhibition of HIV-1 infection by a CCR5-binding cyclophilin from Toxoplasma gondii. Blood 2003, 102, 3280–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golding, H.; Khurana, S.; Yarovinsky, F.; King, L.R.; Abdoulaeva, G.; Antonsson, L.; Owman, C.; Platt, E.J.; Kabat, D.; Andersen, J.F.; Sher, A. CCR5 N-terminal region plays a critical role in HIV-1 inhibition by Toxoplasma gondii-derived cyclophilin-18. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, 29570–29577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Huang, X.; Yu, Q.; Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, G.; Ren, W.; Zhang, X. The protective effect of a DNA vaccine encoding the Toxoplasma gondii cyclophilin gene in BALB/c mice. Parasite Immunology 2013, 35, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Huang, X.; Gong, P.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Yang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, N.; Zhang, X. Protective immunity induced by a recombinant BCG vaccine encoding the cyclophilin gene of Toxoplasma gondii. Vaccine 2013, 31, 6065–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-P.; Zhong, H.-N.; Zhou, H.-M. Catalysis of the refolding of urea denatured creatine kinase by peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1997, 1338, 1997–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| UniProt | TrichDB2 | TrichDB3 | NCBI | PDB | PPIase name |

Localization5 | Function5 | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2FJP1 | TVAG_370440 | TVAGG3_0054050 | XP_001307803 | TvCyP14 | Nucleus | [43] | ||

| A2EC21 | TVAG_137880 | TVAGG3_0269460 | XP_001322019.1 | TvCyP18 | Cytoplasm | [43] | ||

| A2DT06 | TVAG_004440 | TVAGG3_0649370 | XP_001328636.1 | 5YB9 | TvCyP19 (TvCyP1)4 | Cytoplasm Hydrogenosomes, Cytoplasm and Membrane |

Protein trafficking | [27,29] |

| A2F1H0 | TVAG_027250 | TVAGG3_0947870 | XP_001314072 | TvCyP19.2 | Cytoplasm | [43] | ||

| A2FAA8 | TVAG_047830 | TVAGG3_0485720 | XP_001311112 | TvCyP19.8 | Cytoplasm | [43] | ||

| A2DLL4 | TVAG_062520 | TVAGG3_0580400 | XP_001579633.1 | 6LXO | TvCyP19.9 TvCyP24 |

Cytoplasm ER, Cytoplasm, and Membrane |

Protein trafficking | [28,30] |

| A2E5J4 | TVAG_038810 | TVAGG3_0240350 | XP_001324258 | TvCyP20 | Cytoplasm | [43] | ||

| A2FIV3 | TVAG_078570 | TVAGG3_0462310 | XP_001308098 | TvCyP21 | Cytoplasm | [43] | ||

| A2DKZ9 | TVAG_146960 | TVAGG3_0362200 | XP_001579938 | TvCyP22 | Cytoplasm | [43] | ||

| A2FTU8 | TVAG_27739 | TVAGG3_0951420 | XP_001304599 | TvCyP23 | Cytoplasm | [43] | ||

| A2E6H3 | TVAG_106810 | TVAGG3_0040330 | XP_001324009.1 | TvCyP37 | Nucleus | [43] | ||

| A2GDG2 | TVAG_583670 | TVAGG3_0820230 | XP_001297735.1 | TvCyP44 | Cytoplasm and Nucleus |

[43] | ||

| A2DEW6 | TVAG_172150 | TVAGG3_0530670 | XP_001581944.1 | TvCyP63 | Nucleus | [43] | ||

| A2DA37 | TVAG_476140 | TVAGG3_0266130 | XP_001583671.1 | TvFKBP12 | Cytoplasm | [43] | ||

| A2DYS7 | TVAG_426610 | TVAGG3_0538360 | XP_001326690.1 | TvFKBP15.1 | ER | [43] | ||

| A2G763 | TVAG_062070 | TVAGG3_0922950 | XP_001299933.1 | TvFKBP15.2 | ER | [43] | ||

| A2FYT1 | TVAG_435000 | TVAGG3_0194750 | XP_001302863.1 | TvFKBP19 | Cytoplasm | [43] | ||

| A2F0D0 | TVAG_292580 | TVAGG3_0216440 | XP_001330357.1 | TvFKBP20 | Cytoplasm | [43] | ||

| A2EV02 | TVAG_368970 | TVAGG3_0441630 | XP_001315748.1 | TvFKBP30 | Cytoplasm | [43] | ||

| A2EC50 | TVAG_413760 | TVAGG3_0204900 | XP_001321950.1 | TvFKBP32 | Cytoplasm | [43] | ||

| A2G9L9 | TVAG_428320 | TVAGG3_0107870 | XP_001299079.1 | TvFKBP33 | Cytoplasm | [43] | ||

| A2FER9 | TVAG_140950 | TVAGG3_0603860 | XP_001309536.1 | TvFKBP63 | [43] | |||

| A2ECU0 | TVAG_102340 | TVAGG3_0563910 | XP_001321708.1 | TvPar17.84 | Cytoplasm | [43] | ||

| A2ED59 | TVAG_420360 | TVAGG3_0425040 | XP_001321637.1 | TvPar17.87 | Cytoplasm and Nucleus |

[43] | ||

| A2EWG2 | TVAG_325610 | TVAGG3_0877000 | XP_001315212.1 | TvPar102 | Cytoplasm and Nucleus |

[43] |

| UniProt | AmoebaDB | NCBI | PPIase name | Localization4 | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C4LYX1 | EHI_117870 | XP_656069.1 | EhCyP10 | |||

| O15729 | EHI_125840 | XP_656494.1 | EhCyP18 (EhCyP)3 |

Cytoplasm | [43,46] | |

| C4M7U6 | EHI_020340 | XP_654585.1 | EhCyP20 | Cytoplasm | [43] | |

| C4M525 | EHI_128100 | XP_648283.1 | EhCyP21 | Cytoplasm | [43] | |

| C4M942 | EHI_083580 | XP_654418.1 | EhCyP22 | Cytoplasm | [43] | |

| C4M2J5 | EHI_054760 | XP_654797.2 | EhCyP40 | Nucleus | [43] | |

| C4LTN0 | EHI_012390 | XP_655852.2 | EhFKBP18 | ER | [43] | |

| C4M276 | EHI_180160 | XP_653822.1 | EhFKBP29 | |||

| C4LTA4 | EHI_044850 | XP_657211.1 | EhFKBP35 | |||

| B1N302 | EHI_051870 | XP_001913568.1 | EhFKBP43 | |||

| C4LUU9 | EHI_178850 | XP_656239.1 | EhFKBP46 | |||

| C4M181 | EHI_188070 | XP_653673.2 | EhPar13 | Cytoplasm and Nucleus | [43] | |

| C4LT92 | EHI_044730 | XP_657226.1 | EhPar13.25 | Nucleus | [43] |

| Isolate | UniProt | GiardiaDB | NCBI | PDB | PPIase name | Localization4 | Function4 | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G. intestinalis WB | GiCyP19 (GiCyP1)3 |

[55] | ||||||

| A8BC67 | GL50803_0017163 | XP_001707838.1 | GiCyP183 | Cytoplasm Secreted |

Virulence factor | [43,62] | ||

| A8BJP8 | GL50803_0017000 | XP_001706629.1 | GiCyP21 | Cytoplasm Secreted |

[43,62] | |||

| G. intestinalis DH | V6TEN6 | DHA2_17000 | GiCyP25 | Membrane | [43] | |||

| G. intestinalis GS | C6LQJ1 | GL50581_1019 | GiCyP18 | Secreted | [43] | |||

| C6LR04 | GL50581_1186 | GiCyP21 | Secreted | [43] | ||||

| G. intestinalis WB | Q8I6M8 | GL50803_10450 | XP_001709141.1 | 2LGO | GiFKBP123 | Secreted | [58,62] | |

| A8B770 | GL50803_7246 | XP_001709155.1 | GiFKBP13 | Cytoplasm | [43] | |||

| A8BHU4 | GL50803_101339 | XP_001706925.1 | GiFKBP24 | Cytoplasm Secreted |

[43,62] | |||

| A8BUZ7 | GL50803_42780 | XP_001704692.1 | GiFKBP28 | |||||

| A8BAF3 | GL50803_3643 | XP_001708385.1 | GiFKBP38 | Cytoplasm Secreted |

[43,62] | |||

| A8BK50 | GL50803_10570 | XP_001706462.1 | GiFKBP39 | |||||

| G. intestinalis DH | V6TL25 | DHA2_151252 | GiFKBP29 | |||||

| G. intestinalis GS | C6LUS9 | GL50581_2531 | GiFKBP12 | Secreted | [62] | |||

| C6LPP4 | GL50581_711 | GiFKBP13 | ||||||

| C6LXS7 | GL50581_3593 | GiFKBP24 | Secreted | [62] | ||||

| C6LY30 | GL50581_3701 | GiFKBP28 | ||||||

| C6LPE9 | GL50581_614 | GiFKBP38 | Secreted | [62] | ||||

| C6M084 | GL50581_4472 | GiFKBP39 |

| UniProt | TriTrypDB | NCBI | PDB | PPIase name | Localization4 | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O02614 | LmjF.25.0910 (CYPA) | XP_001683845.1 | LmCyP19 (LmaCyP1)3 | Cilium, Cytoplasm, and Nucleus | [43,95,96] | ||

| Q4QJ67 | LmjF.06.0120 (CYP2) | XP_001680781.1 | LmCyP20.3 (LmaCyP2) | Cytoplasm | [43,92] | ||

| Q4QBG3 | LmjF.23.0125 (CyP3) | XP_001683335.1 | LmCyP20.4 (LmaCyP3) | Nucleus | [43,92] | ||

| Q4Q424 | LmjF.33.1630 (CYP4) | XP_001685924.1 | LmCyP24 (LmaCyP4) | Cytoplasm | [43,92] | ||

| Q4Q6Q9 | LmjF.31.0050 (CYP5) | XP_001684989.1 | LmCyP24.6 (LmaCyP5) | Cytoplasm | [43,92] | ||

| Q4QBK2 | LmjF.22.1450 (CYP6) | XP_001683296.1 | 7AIH | LmCyP25 (LmaCyP6) | Cilium, Cytoplasm, and Nucleus | [43,92,95] | |

| E9AFI5 | LmjF.35.3610 (CYP7) | XP_003722755.1 | LmCyP26 (LmaCyP7) | Cilium, Cytoplasm, and Nucleus | [43,92] | ||

| Q4QAK0 | LmjF.24.1315 (CYP8) | XP_001683648.1 | LmCyP26.5 (LmaCyP8) | Cytoplasm | [43,92] | ||

| Q4Q7V7 | LmjF.30.0020 (CYP9) | XP_001684591.1 | LmCyP27 (LmaCyP9) | Axoneme and Cytoplasm | [43,92] | ||

| Q4Q1A6 | LmjF.36.3130 (CYP10) | XP_001686892.1 | 7AM2 | LmCyP29 (LmaCyP10) | Cytoplasm | [43,92,94,95] | |

| Q4QBH1 | LmjF.23.0050 (CYP11) | XP_001683327.1 | 2HQJ | LmCyP32 (LmaCyP11) | Cytoplasm and Nucleolus | [43,58,92] | |

| E9AC11 | LmjF.01.0220 (CYP12) | XP_003721542.1 | LmCyP36 (LmaCyP12) | Axoneme and Cytoplasm | [43,92] | ||

| E9AFV2 | LmjF.35.4770 (CYP40) | XP_003722872.1 | LmCyP38 (LmaCyp40)3 | Cytoplasm | [43,92] | ||

| Q4QEP7 | LmjF.16.1200 (CYP13) | XP_001682201.1 | LmCyP39 (LmaCyP13) | Axoneme and Cytoplasm | [43,92] | ||

| E9AEZ3 | LmjF.35.1720 (CYP14) | XP_003722563.1 | LmCyP48 (LmaCyP14) | Cytoplasm and Membranes | [43,92] | ||

| Q4QCV2 | LmjF.20.0940 (CYP15) | XP_001682846.1 | LmCyP49 LmaCyP15 | [92] | |||

| Q4QDV4 | LmjF.18.0880 (CYP16) | XP_001682494.1 | LmCyP108 LmaCyP16 | Nucleoplasm | [43,92] | ||

| Q4QBK4 | LmjF.22.1430 | XP_001683294.1 | LmFKBP-11.8 (maFKBPL1) | Axoneme and Cytoplasm | [43,92] | ||

| Q4Q255 | LmjF.36.0230 | XP_001686593.1 | LmFKBP-11.9 (LmaFKBPL2) | [92] | |||

| Q4QHC5 | LmjF.10.0890 | XP_001681423.1 | LmFKBP-17.3 (LmaFKBPL3) | [92] | |||

| Q4QDB9 | LmjF.19.0970 | XP_001682679.1 | LmFKBP-23 (LmaFKBPL4) | [92] | |||

| Q4QD56 | LmjF.19.1530 | XP_001682742.1 | LmFKBP-48 (LmaFKBPL5) | [92] | |||

| Q4QII4 | LmjF.07.1030 (PIN1) | XP_001681014.1 | LmPar13 (LmaPPICL1)3(LmPIN1) | Cytosol and nucleus | [43,92,97] | ||

| Q4QBU3 | LmjF.22.0530 (PAR45) | XP_001683205.1 | LmPar47 (LmaPPICL2) | Nucleus | [43,92] |

| UniProt | TriTrypDB | NCBI | PDB | PPIase name | Localization4 | Function4 | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E9BHJ8 | LdBPK_250940.1 (CYPA) | XP_003861424.1 | LdCyP19 | ||||

| A0A3S7WXE3 | LdBPK_230140.1 | XP_003860915.1 | LdCyP20.3 | ||||

| Q9U9R3 | LdBPK_060120.1 | XP_003858320.1 | 2HAQ | LdCyP20.43(LdCyP) | Cytoplasm and ER | Disaggregation and Aggregation prevention | [91,93,98,99,100] |

| A0A3S7X410 | LdBPK_310060.1 | XP_003863096.1 | LdCyP24 | ||||

| A0A3Q8ICB3 | LdBPK_221300.1 | XP_003860876.1 | LdCyP25 | ||||

| E9BSN7 | LdBPK_353660.1 | XP_003864946.1 | LdCyP26 | ||||

| E9BGZ8 | LdBPK_241350.1 | XP_003861226.1 | LdCyP27 | ||||

| A0A3S7X325 | LdBPK_300020.1 | XP_003862718.1 | LdCyP28 | ||||

| E9BQA4 | LdBPK_331730.1 | XP_003863999.1 | LdCyP28.6 | Membrane | [93] | ||

| E9BU37 | LdBPK_363280.1 | XP_003865443.1 | LdCyP29 | ||||

| E9BG26A0A504XWA0 | LdBPK_230060.1 | XP_003860907.1 | LdCyP32 | ||||

| A0A451EJ79 | LdBPK_010220.1 | XP_003857835.1 | LdCyP36 | ||||

| A0A3Q8IIG9 | LdBPK_354830.1 | XP_003865060.1 | LdCyP38.4(LdCyP40) | [92] | |||

| A0A504WZ51 | LdBPK_161250.1 | XP_003859812.1 | LdCyP39 | ||||

| E9BS46 | LdBPK_351710.1 (CYP14) | XP_003864755.1 | LdCyP48.5 | Membrane | [43] | ||

| E9BEP2 | LdBPK_200950.1 | XP_003860435.1 | LdCyP49 | ||||

| E9BDR8 | LdBPK_180880.1 | XP_003860101.1 | LdCyP108 | ||||

| E9BFZ3 | LdBPK_221280.1 | XP_003860874.1 | LdFKBP11.8 | ||||

| E9BT84 | LdBPK_360250.1 | XP_003865142.1 | LdFKBP11.9 | ||||

| E9BAD9 | LdBPK_100940.1 | XP_003858930.1 | LdFKBP17 | ||||

| E9BE85 | LdBPK_190920.1 | XP_003860268.1 | LdFKBP22 | ||||

| E9BEE5 | LdBPK_191560.1 | XP_003860328.1 | LdFKBP47 | ||||

| E9B9B2 | LdBPK_071180.1 | XP_003858557.1 | LdPar12 | ||||

| E9BFR0 | LdBPK_220410.1 | XP_003860791.1 | LdPar17 |

| UniProt | PlasmoDB | NCBI | PDB | PPIase name | Localization4 | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q8IIK3 | PF3D7_1116300 (CYP19C) | XP_001347841.1 | PfCyP18.6 (PfCyP19C) 3 | Nucleus (Spliceosome) | [43,105,113] | ||

| Q76NN7 | PF3D7_0322000 (CYP19A) | XP_001351290.1 | 1QNG | PfCyP19 (PfCyP19A) 3 | Cytoplasm | [43,105,112,113,115,116] | |

| Q8IIK8 | PF3D7_1115600 (CYP19B) | XP_001347835.1 | PfCyP22 (PfCyP19B) 3 | CytoplasmMembrane | [43,105,116,117,118] | ||

| Q8I3I0 | PF3D7_0528700 (CYP23) | XP_001351841.1 | PfCyP233 | Nucleus (Spliceosome) | [43,105,113] | ||

| Q8I6S4 | PF3D7_0804800 (CYP24) | XP_001349469.1 | PfCyP25 (PfCyP24) 3 | Membrane | [43,105,108,113,119] | ||

| Q8I621 | PF3D7_1202400 (CYP26) | XP_001350433.1 | PfCyP2633 | Cytoplasm | |||

| Q8I5Q4 | PF3D7_1215200 (CYP32) | XP_001350556.1 | PfCyP323 | Cytoplasm and Mitochondria | [43,105,113] | ||

| Q8ILM0 | PF3D7_1423200 (CYP52) | XP_001348397.2 | PfCyP53 (PfCyP52) 3 | Nucleus (Spliceosome) | [43,105,113] | ||

| Q8I2K8 | PF3D7_0930600 (CYP72) | XP_001352173.1 | PfCyP723 | Nucleus | [43,105] | ||

| Q8IAN0 | PF3D7_0803000 (CYP81) | XP_001349484.1 | PfCyP81 | Nucleus | [43,105] | ||

| Q8I402 | PF3D7_0510200 (CYP87) | XP_001351660.1 | 2FU0 | PfCyP87 | Nucleus (Spliceosome)[ | [43,105,106] | |

| C0H5B2 | PF3D7_1313300 | XP_002809009.1 | PfFKBP25.6 | ||||

| Q8I4V8 | PF3D7_1247400 | XP_001350859.1 | 2OFN | PfFKBP353 | Cytoplasm and Nucleus | [43,107,111,114,120] |

| UniProt | ToxoDB | NCBI | PDB | PPIase name | Localization4 | Function4 | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A0A125YZ79 | TGME49_289250 | XP_018636397.1 | TgCyP183 | Manipulates host cell responses | [127,129] | ||

| S8F7V1 | TGME49_221210 | XP_002369951.1 | TgCyP203 | Secreted | Manipulates host cell responses | [125,128] | |

| A0A125YV51 | TGME49_270560 | XP_002365722.1 | TgCyP21 | ||||

| A0A125YL73 | TGME49_285760 | XP_002369214.1 | TgCyP233 | ||||

| A0A125YLU4 | TGME49_230520 | XP_002367963.2 | TgCyP26 | ||||

| S8FB56 | TGME49_238000 | XP_018637703.1 | TgCyP32 | ||||

| A0A125YQ35 | TGME49_262520 | XP_002365354.1 | TgCyP35 | ||||

| S8F5I7 | TGME49_205700 | XP_002367801.1 | TgCyP383 | Membrane | [43,125] | ||

| A0A125YVH7 | TGME49_241830 | XP_002366733.1 | 3BKP | TgCyP64 | [58] | ||

| A0A125YII8 | TGME49_229940 | XP_002367918.1 | TgCyP66.21 | Nucleus | |||

| S8GFQ1 | TGME49_227850 | XP_002366408.1 | TgCyP66.25 | Nucleus | |||

| A0A125YUW2 | TGME49_305940 | XP_002370366.1 | 3BO7 | TgCyP69 | [58] | ||

| S8FD30 | TGME49_320640 | XP_002369921.1 | TgCyP86 | ||||

| S8GFX3 | TGME49_228360FKBP-12 | XP_002366458.1 | TgFKBP38 | Membrane | [43] | ||

| S8F5H8 | TGME49_285850 | XP_002369223.1 | TgFKBP46 | ||||

| Q4VKI5 | TGME49_283850 | XP_018637740.1 | TgFCBP572,3 | [126] | |||

| A0A125YIR1 | TGME49_318275 | XP_018637996.1 | TgFKBP64 | ||||

| S8F128 | TGME49_258625 | XP_018637023.1 | TgFKBP66 | ||||

| A0A125YRG0 | TGME49_258930 | XP_002365107.1 | TgPar13 | ||||

| S8EUZ2 | TGME49_228040 | XP_002366427.1 | TgPar96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).