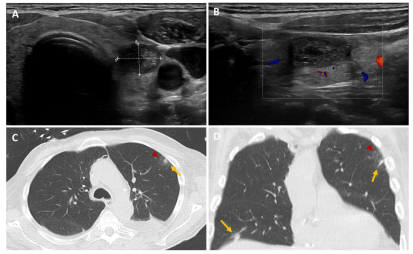

We report the case of a 71-year-old patient admitted to intensive care with severe abdominal-onset sepsis treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics. The patient had undergone liver transplantation for a moderately differentiated hepatocarcinoma operated on more than 1 year previously. During the workup, and given his immunosuppression, an extensive bacteriological mapping was carried out (viral, bacterial, parasitic, fungal) which came back positive for Clostridium difficile. Antibiotic therapy was rapidly modulated in the light of our results, with a favourable clinical and biological outcome. In her follow-up, we noted the presence of an aspergillary antigen which came back positive late and was checked 2 times. A thoracic CT scan was performed and showed the presence of two pulmonary nodules in the upper left lobar with frosted glass and the lower right lobar (

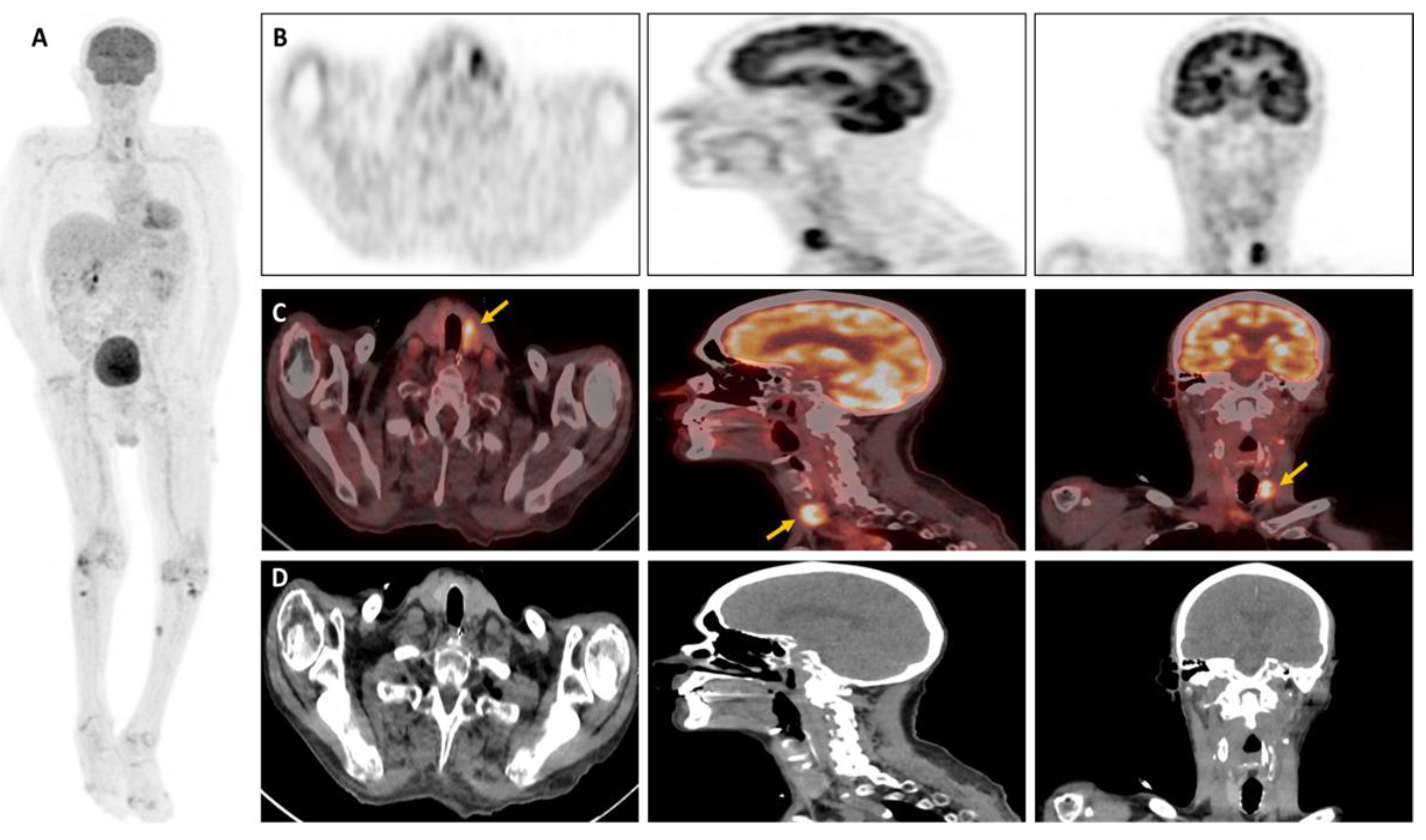

Figure 2A,B). A bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was achieved, confirming the presence of Aspergillus fumigatus the diagnosis of pulmonary aspergillosis. An 18F-FDG-PET-CT was ordered to assess the presence of any extra-pulmonary sites and revealed subcutaneous/muscular nodules and focal hypermetabolism in the left thyroid lobe (

Figure 1). In light of the results, a thyroid work-up was carried out; the biological tests came back normal, and the thyroid ultrasound revealed an iso- and hypoechoic EU-TIRADS-5 macro-nodule of the left lobe measuring 18x12x23mm, with vascularization around the perimeter, which had been punctured (

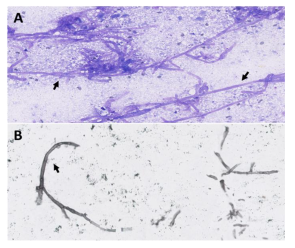

Figure 2C,D). Histological findings showed the presence of an aspergill filament within the lesion, confirming the diagnosis of invasive thyroid aspergillosis (

Figure 3). Aspergillosis is a prevalent fungal infection caused by inhaling spores (named conidia) of the mould Aspergillus [

1]. These are generally contained in soils, plants, and decaying organic matter, but also in the air and indoor environments. Over 200 species of Aspergillus are currently thought to have been described, of which only around 10% are pathogenic to humans [

2]. The genus Aspergillus comprises several hundred species, of which Aspergillus fumigatus remains the most common pathogenic agent, responsible for approximately 90% of cases of Aspergillus disease, followed by Aspergillus flavus, Niger, Terreus and Nidulans [

3]. In general, Aspergillosis is fairly widespread. Depending on the patient’s immunity, they can lead to various forms of clinical presentation, ranging from an isolated form to multi-organ involvement [

5]. The most severe forms, known as “invasive”, are usually seen in immunocompromised patients due to HIV infection, oncological conditions, intensive chemotherapy, immunosuppressive drug therapy, post-transplant conditions, or other chronic diseases, and may be associated with high mortality rates and life-threatening illness [

6]. It is therefore crucial to assess both the extent of the disease and the effectiveness of treatment, with several diagnostic strategies currently available. The cornerstone of IA diagnosis is biopsy-based fungal culture, supplemented by other biomarker tests such as galactomannan in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) [

7]. Conventional CT imaging is generally useful in diagnostic management, but radiological features of aspergillosis are not specific, and the CT finding termed the “halo-signal” is a sign that may not always be clearly detectable [

8].

In this challenging context, nuclear medicine imaging has gained in popularity, particularly through the performance of 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography combined with computed tomography (

18F-FDG-PET/CT) in the diagnosis and monitoring of infectious diseases [

9].

18F-labelled FDG is a glucose analogue absorbed by cells via a membrane transporter (GLUT-1 and GLUT-3) and sequestered after phosphorylation. Therefore, its intracellular concentration is proportional to the cell’s metabolism [

9]. Typically, cellular use of glucose rises in leukocytes activated by infection and inflammation, leading to intense uptake of

18F-FDG, detectable by PET/CT [

10]. Due to the heterogeneous presentation of IA,

18F-FDG-PET/CT is a consistent tool, particularly in the early stages of the disease, and for the detection of extrapulmonary lesions [

11]. According to the literature, the metabolic activity of aspergill nodules is not necessarily high and may vary (low to high uptake) depending on aggressiveness and form (acute or chronic IA) [

11]. Some authors have reported different metabolical imaging presentations of aspergillary lesions; a cold nodule with discrete surrounding metabolism, an iso-metabolic one when glucose uptake is similar to or less than the mediastinal blood pool, and a hypermetabolic one when glucose uptake is greater than the mediastinal blood pool as in our patient [

11,

12]. Hence, IA can result in a wide range of clinical manifestations of aspergillosis and a broad spectrum of possible presentations on 18F-FDG-PET/CT imaging. In our view, Aspergillosis predominantly affects the lungs which invade the lung parenchyma and vasculature, but may also spread by hematogenous route to various organs such as the central nervous system, heart, kidney, skin, soft tissues, and liver [

6]. The thyroid gland is an unusual localization as it is extremely resistant to infection owing to its high iodine level, hydrogen peroxide production, extensive lymphatic and vascular supply, and encapsulated location [

13]. Thyroid aspergillosis may exhibit variability in thyroid bioassays, ranging from hyperthyroidism due to hormone release from follicular cell lesions, to hypothyroidism or euthyroidism, as in our patient’s case [

11]. The majority of cases are frequently asymptomatic, and given the shallow epidemiological data on thyroid aspergillosis in the literature, the diagnosis was often made at autopsy (approximately 10-12% of extrapulmonary disease) [

14]. According to the literature, no studies of hypermetabolic nodular thyroid aspergillosis on 18F-FDG-PET/CT confirmed on histology have yet been reported. In our patient, given the focal thyroid hypermetabolism, ultrasound and fine needle aspiration (FNA) were performed to avoid missing another pathology, revealing the presence of a hypoechoic, non-vascularised nodule (

Figure 2A-B) and aspergillus filaments (

Figure 3), confirming the diagnosis of atypical thyroid invasive aspergillosis. Invasive aspergillosis is a relatively common fungal infection in immunocompromised patients, generally affecting the lungs, but can also spread by hematogenous route and invade other organs. Thyroid aspergillosis has been rarely reported in the literature and is an entity that physicians should be aware of. The scope and severity of clinical manifestations may vary according to the individual’s immune status and the location of the invaded organs. Delays in diagnosis therefore often contribute to fatal outcomes and delayed treatment. Clinicians must incorporate 18F-FDG PET/CT into the diagnostic and therapeutic management of patients with suspected Aspergillus infection to provide a comprehensive assessment and determine the most suitable therapy.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not receive ethical review and approval due to the nature of the research (case report).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient. The consent form was obtained on 01.03.2024.

Data Availability Statement

The data used and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NAR et al (2012) Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med. [CrossRef]

- Chotirmall SH, Al-Alawi M, Mirkovic B et al (2013) Aspergillus associated airway disease, infammation, and the innate immune response. Biomed Res Int.

- Bigot J, Guillot L, Guitard J, Ruffin M, Corvol H, Balloy V, Hennequin C. Bronchial Epithelial Cells on the Front Line to Fight Lung Infection-Causing Aspergillus fumigatus. Front Immunol. 2020 ; 11:1041. 22 May.

- Salazar F, Brown GD (2018) Antifungal innate immunity: a perspective from the last 10 years. J Innate Immun 10:373–397.

- Tunniclife G, Schomberg L, Walsh S et al (2013) Airway and parenchymal manifestations of pulmonary aspergillosis. Respir Med 107:1113–1123.

- Van de Veerdonk FL, Gresnigt MS, Romani L et al (2017) Aspergillus fumigatus morphology and dynamic host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol 15:661–674.

- Ullmann AJ, Aguado JM, et al. Diagnosis and management of Aspergillus diseases: executive summary of the 2017 ESCMID-ECMM-ERS guideline. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018 May;24 Suppl 1:e1-e38. Epub 2018 Mar 12. [PubMed]

- Ray A, Mittal A, Vyas S. CT Halo sign: A systematic review. Eur J Radiol. 2020 Mar;124:108843. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaudemans AW, de Vries EF, Galli F, Dierckx RA, Slart RH, Signore A. The use of (18)F-FDG-PET/CT for diagnosis and treatment monitoring of inflammatory and infectious diseases. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:623036. Epub 2013 Aug 21. PMCID: PMC3763592. [PubMed]

- Ledoux MP, Guffroy B, Nivoix Y, Simand C, Herbrecht R. Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Feb;41(1):80-98. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altini, C. , Ruta, R., Mammucci, P. et al. Heterogeneous imaging features of Aspergillosis at 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Transl Imaging 10, 435–445 (2022).

- Kim JY, Yoo J-W, Oh M et al (2013) F-Fluoro-2-Deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography fndings are diferent between invasive and noninvasive pulmonary Aspergillosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr 37(4):596–601.

- Lisbona R, Lacourciere Y, Rosenthall L. Aspergillomatous abscesses of the brain and thyroid. J Nucl Med. 1973;14(7):541–2.

- Hori A, Kami M, Kishi Y, Machida U, Matsumura T, Kashima T. Clinical significance of extra-pulmonary involvement of invasive aspergillosis: a retrospective autopsy-based study of 107 patients. J Hosp Infect. 2002;50(3): 175–82.

- Nguyen J, Manera R, Minutti C. Aspergillus thyroiditis: a review of the literature to highlight clinical challenges. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31(12):3259–64.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).