Submitted:

07 June 2024

Posted:

10 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

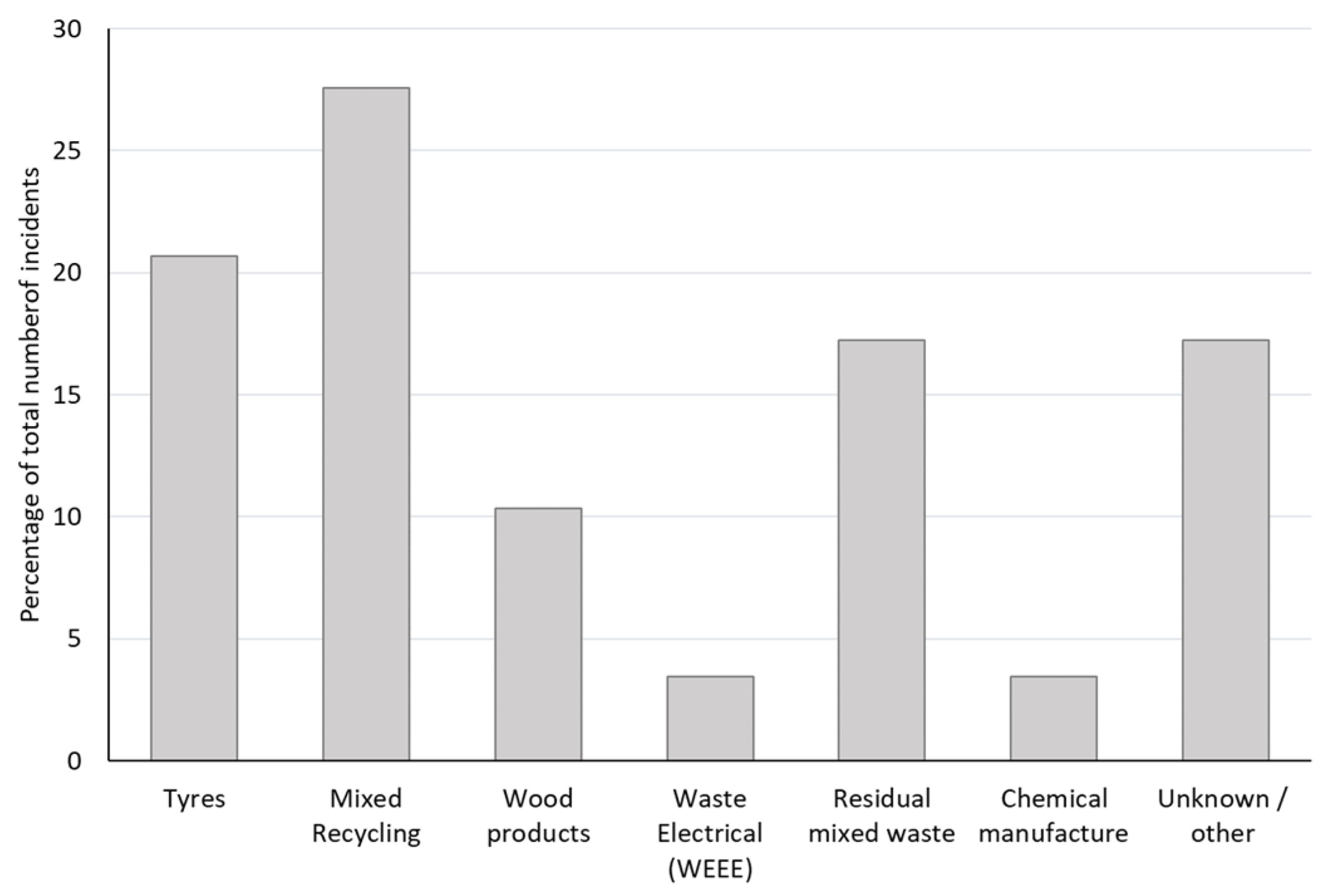

2. Types of Industrial Fires and Associated Pollutants

3. Monitoring and of Industrial Fires

| Monitoring technique and principle | Context for monitoring | Determinands, with detection limits (dl) in parentheses, where available (in ppm, or ug/m3 for particulates). | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Continuous / real time techniques |

|||

| Laser light scattering (670nm) (Turnkey Osiris particulate monitor) | Included in equipment inventory for deployment to UK AQinMI fires. | Total suspended solids (TSP), PM10, PM2.5, and PM1 (all 0.1). | [5,29] |

| Low cost particulate sensors | Wildfires in california | PM2.5 PM10. See reference for performance characteristics. | [30] |

| Beta Attenuation monitor | Fire at open-cut coal min in Latrobe, Victoria, Australia. | PM2.5 (3.4 for 1-h) | [31,32] |

| Infrared (Gasmet DX4030/40) | Included in equipment inventory for deployment to UK AQinMI fires | Carbon dioxide (10), carbon monoxide (1), nitrous oxide (0.02), methane (0.11), sulfur dioxide (0.30), ammonia (0.13), hydrogen chloride (0.20), hydrogen bromide (3.0), hydrogen fluoride (0.2), hydrogen cyanide (0.35), formaldehyde (0.09), 1,3-butadiene (0.20), benzene (0.3), toluene (0.13), ethyl benzene (0.08), m-xylene (0.12), o-xylene (0.12), p-xylene (0.12), acrolein (0.25), phosgene (0.2), arsine (0.02), phosphine (0.2) and methyl isocyanate (0.25). | [1,5] |

| Proton Transfer Reaction Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (PTR-TOF-MS) | Monitoring of a biomass fire | 132 separate VOCs (single ppb) | [11] |

| Automated gas chromatograph | Fire at International Terminals Company, chemical factory, Deer Park, Houston, Texas. | Range of VOCs and other hazardous air pollutants (HAPS) (0.4 ppb-C) | [4] |

| Electrochemical cell (GFG-Microtector II G460) | Industrial fires in Saudi Arabia (exposure by firefighters) | Carbon monoxide (1), hydrogen cyanide (0.5), ammonia (1), sulfur dioxide (0.1), hydrogen chloride (0.2), Hydrogen sulfide (0.2 ppm). | [26] |

| QRAE electrochemical cell |

Included in equipment inventory for deployment to UK AQinMI fires | Chlorine (dl) and carbon monoxide (dl) | [5] |

| ppbRAE photoionization detector |

Fire at International Terminals Company, chemical factory, Deer Park, Houston, Texas. | Total VOCs (ppb) | [28] |

| Jerome gold film electrical resistance analyser | Included in equipment inventory for deployment to UK AQinMI fires | Hydrogen sulfide (3 ppb) | [5,33] |

| Triple quadrupole mass spectrometer Trace atmospheric gas analyzer (TAGA IIe) | Chemical works (chlorine-based pool chemicals), Guelph, Ontario, Canada | HCl and Cl2 (0.5 µg m-3) | [20] |

| Mobile photochemical Monitoring station (MPAMS) and open-path FTIR | Fire at a naphtha cracking complex of a petrochemical complex in Yunling County, Taiwan in May 2011. | Ehylene, propane, butane, toluene, benzene, vinyl chloride monomer, 1,3-butadiene, all at ppb levels. | [17] |

| Non-continuous techniques | |||

| Tecora Delta Low flow pump (1 L min-1) with impinger: absorption into solution followed by wet chemical analysis | Included in equipment inventory for deployment to UK AQinMI fires |

Hydrogen cyanide, acetic acid, hydrogen sulfide, chromic acid (impinger solution of 0.05M sodium hydroxide). Ammonia (impinger solution of 0.05M sulfuric acid) | [5] |

| Tecora Delta low flow pump pump (1 L min-1) with PTFE filter + silver membrane | Included in equipment inventory for deployment to UK AQinMI fires |

Bromine and chlorine (dl dependent on sampling period). | [5] |

| Tecora Delta low flow pump (0.5 L min-1) with Silica gel – Supelco Orbo 53 | Included in equipment inventory for deployment to UK AQinMI fires. | Hydrogen fluoride, nitric acid, phosphoric acid, sulphuric acid, sulfur trioxide and arsine (dl dependent on sampling period). | [5] |

| Tecora Delta low flow pump (0.2 L min-1) with thermal desorption (TD) | Included in equipment inventory for deployment to UK AQinMI fires |

(All at ppb levels) 1,1,1-trichlorothane, 1,2-dichloroethane, 1,3-butadiene, 2,4-toluene diisocyanate, 2,6-toluene diisocyanate, acetone, acetonitrile, acrolein, acrylamide, acrylonitrile, benzene, CS2, chlorobenzene, chloroform, chloropicrin, dichloromethane, ethyl acrylate, ethyl benzene, ethyl isocyanate, ethylene oxide, formaldehyde, methyl acrylate, methyl bromide, methyl chloride, 2-butanone, methyl isocyanate, methyl isothiocyanate, methyl methacrylate, methyl styrene, phenol, phosgene, propane, styrene, tetrachloroethylene, tetrachloromethane, toluene, trichloroethylene, vinyl chloride, xylene, other volatile organic compounds (dl dependent on sampling period). | [5] |

| Tecora Delta low flow pump (10 L min-1) with gridded asbestos filter | Included in equipment inventory for deployment to UK AQinMI fires | Asbestos | |

| SUMMA 6-L vacuum canister for collection, followed by GC-MS | Industrial fires in Saudi Arabia (exposure by firefighters) | (All at ppb levels) 1,3-butadiene, acetone, trichloromonofluoromethane, 1,1-dichloro-ethene, methylene chloride, carbon disulfide, methyl tert-butyl ether, 1,2-dichloro-ethene, benzene, bromodichloromethane, methyl isobutyl ketone, heptane, toluene, tetrachloroethylene, ethylbenzene, m-xylene, o-xylene, p-xylene, styrene, 1,3,5-Trimethylbenzene, benzyl chloride and 1,2,4-Trichlorobenzene. | [26] |

| SUMMA 6-L vacuum canister for collection, followed by GC-MS | Buncefield oil storage fire) | (All at ppb levels) m- and o- and p-xylenes, toluene, benzene and ethyl benzene. | [34] |

| Cannister followed by GC-MS | Fire at open-cut coal mine in Latrobe, Victoria, Australia | Speciated VOCs (All at ppb levels) | [31] |

| Radiello diffusive sampler with adsorbent (modified scintered microporous polyethylene) | Fire at open-cut coal mine in Latrobe, Victoria, Australia | Speciated VOCs (All at ppb levels) | [31] |

| 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH)-coated solid sorbent cartridges, collecting carbonyls as derivatives, followed by elution and analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). | Fire at open-cut coal mine in Latrobe, Victoria, Australia | Carbonyl compounds (e.g., formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acrolein, acetone and benzaldehyde. | [31] |

| Tecora Echo high volume sampler (200 L min-1) with quartz filter. Gravimetric with extraction from filter. | Included in equipment inventory for deployment to UK AQinMI fires | Antimony, arsenic, cadmium, chromium, lead, manganese, nickel, platinum, thallium, vanadium, mercury, other metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, polychlorinated biphenyls, pesticides | [5] |

| Polyurethane Foam (PUF) filters | Fire at open-cut coal mine in Latrobe, Victoria, Australia. Also included in equipment inventory for deployment to UK AQinMI fires | Dioxins and derivatives, including polychlorinated dibenzodioxins, furan and derivatives, including polychlorinated dibenzofurans. PAHs | [5,31] |

4. Modelling of Public Exposure to Harmful Airborne Pollutants from Industrial Fires

5. Health Impacts of Major Incident Fires

6. Suitability of Guideline Values for PM

7. Environmental Justice and Socio-Economic Factors

8. Conclusions, Recommendations and Research Needs

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griffiths, S.D.; Entwistle, J.A.; Kelly, F.J.; Deary, M.E. Characterising the ground level concentrations of harmful organic and inorganic substances released during major industrial fires, and implications for human health. Environment International 2022, 162, 107152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkış, S.; Aksoy, E.; Akpınar, K. Risk assessment of industrial fires for surrounding vulnerable facilities using a multi-criteria decision support approach and GIS. Fire 2021, 4, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A. Risk of spontaneous and anthropogenic fires in waste management chain and hazards of secondary fires. Resour Conserv Recy 2020, 159, 104852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, G.T.; Desikan, A.; Morse, R.; Kalman, C.; MacKinney, T.; Cohan, D.S.; Reed, G.; Parras, J. Assessment of air pollution impacts and monitoring data limitations of a spring 2019 chemical facility fire. Environmental Justice 2022, 15, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S.D.; Chappell, P.; Entwistle, J.A.; Kelly, F.J.; Deary, M.E. A study of particulate emissions during 23 major industrial fires: Implications for human health. Environ International 2018, 112, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.L.; Gao, C.X.; Dennekamp, M.; Williamson, G.J.; Brown, D.; Carroll, M.T.; Ikin, J.F.; Del Monaco, A.; Abramson, M.J.; Guo, Y. Associations between respiratory health outcomes and coal mine fire PM2. 5 smoke exposure: a cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, S.D. Analysis of monitoring data from Major Air Pollution Incidents: Translational lessons for Public Health and Community Resilience Policy and Practice. Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, 2024.

- UNEP. Wasted Air: Impact of Landfill Fires on Air Pollution and People’s Health in Serbia - Working Paper. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/45428 (accessed on May).

- Urquhart, G.J.; Symington, M.; Foxall, K.; Harrison, H.; Sepai, O. Using science to respond to public exposures from chemical hazards during emergencies in England. Toxicology Research 2023, 12, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, M.T.; Doolan, D.; O’Sullivan, A.; Hession, M. Emergency planning and the Control of Major Accident Hazards (COMAH/Seveso II) Directive: An approach to determine the public safety zone for toxic cloud releases. Journal of hazardous materials 2008, 154, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brilli, F.; Gioli, B.; Ciccioli, P.; Zona, D.; Loreto, F.; Janssens, I.A.; Ceulemans, R. Proton Transfer Reaction Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometric (PTR-TOF-MS) determination of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted from a biomass fire developed under stable nocturnal conditions. Atmos Environ 2014, 97, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koss, A.R.; Sekimoto, K.; Gilman, J.B.; Selimovic, V.; Coggon, M.M.; Zarzana, K.J.; Yuan, B.; Lerner, B.M.; Brown, S.S.; Jimenez, J.L. Non-methane organic gas emissions from biomass burning: identification, quantification, and emission factors from PTR-ToF during the FIREX 2016 laboratory experiment. Atmos Chem Phys 2018, 18, 3299–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemieux, P.M.; Lutes, C.C.; Santoianni, D.A. Emissions of organic air toxics from open burning: a comprehensive review. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2004, 30, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, J.C. A Toxicological Review of the Products of Combustion. 2010.

- Estrellan, C.R.; Iino, F. Toxic emissions from open burning. Chemosphere 2010, 80, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisen, F.; Gillett, R.; Choi, J.; Fisher, G.; Torre, P. Characteristics of an open-cut coal mine fire pollution event. Atmospheric Environment 2017, 151, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shie, R.-H.; Chan, C.-C. Tracking hazardous air pollutants from a refinery fire by applying on-line and off-line air monitoring and back trajectory modeling. Journal of hazardous materials 2013, 261, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruokojärvi, P.; Ettala, M.; Rahkonen, P.; Tarhanen, J.; Ruuskanen, J. Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and-furans (PCDDs and PCDFs) in municipal waste landfill fires. Chemosphere 1995, 30, 1697–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruokojärvi, P.; Ruuskanen, J.; Ettala, M.; Rahkonen, P.; Tarhanen, J. Formation of polyaromatic hydrocarbons and polychlorinated organic compounds in municipal waste landfill fires. Chemosphere 1995, 31, 3899–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karellas, N.; Chen, Q.; De Brou, G.; Milburn, R. Real time air monitoring of hydrogen chloride and chlorine gas during a chemical fire. Journal of hazardous materials 2003, 102, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzucco, W.; Costantino, C.; Restivo, V.; Alba, D.; Marotta, C.; Tavormina, E.; Cernigliaro, A.; Macaluso, M.; Cusimano, R.; Grammauta, R. The management of health hazards related to municipal solid waste on fire in Europe: an environmental justice issue? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 6617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, C.; Horii, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Asante, K.A.; Ballesteros Jr, F.; Viet, P.H.; Itai, T.; Takigami, H.; Tanabe, S.; Fujimori, T. Occurrence, profiles, and toxic equivalents of chlorinated and brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in E-waste open burning soils. Environ Pollut 2017, 225, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnermark, A.; Blomqvist, P. Emissions from an automobile fire. Chemosphere 2006, 62, 1043–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.O.; Arôxa, B.H.; Klausner, V.; Bastos, E.J.d.B.; Prestes, A.; Pacini, A.A. Report of Particulate Matter Emissions During the 2015 Fire at Fuel Tanks in Santos, Brazil. Air, Soil and Water Research 2020, 13, 1178622120971251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Gillespie, J.; Schuder, M.; Duberstein, W.; Beverland, I.J.; Heal, M.R. Evaluation and calibration of Aeroqual series 500 portable gas sensors for accurate measurement of ambient ozone and nitrogen dioxide. Atmospheric Environment 2015, 100, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, B.H.; Pasha, M.J.; Al-Shamsi, M.A.S. Firefighter exposures to organic and inorganic gas emissions in emergency residential and industrial fires. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 770, 145332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Schito, G.; Cui, Q. VOC emissions from asphalt pavement and health risks to construction workers. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 244, 118757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An Han, H.; Han, I.; McCurdy, S.; Whitworth, K.; Delclos, G.; Rammah, A.; Symanski, E. The Intercontinental Terminals Chemical Fire Study: a rapid response to an industrial disaster to address resident concerns in Deer Park, Texas. International journal of environmental research and public health 2020, 17, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnkey Instruments Limited. Osiris. Available online: https://turnkey-instruments.

- South Coast AQMD. Air Quality Sensor Performance Evaluation Center. Available online: https://www.aqmd.gov/aq-spec/evaluations (accessed on June).

- Reisen, F.; Cope, M.; Emmerson, K.; Galbally, I.; Gillett, R.; Keywood, M.; Molloy, S.; Powell, J.; Fisher, G.; Torre, P. Analysis of air quality during the Hazelwood mine fire. 2016.

- Met One Instruments. Available online: https://metone.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/bam-1020_detection_limit.pdf (accessed on June).

- Able Instruments. Available online: https://able.co.uk/product/gas-analysers/j605/ (accessed on 13th May).

- Targa, J.; Kent, A.; Stewart, R.; Coleman, P.; Bower, J.; Webster, H.; Taylor, J.; Murray, V.; Mohan, R.; Aus, C. Initial review of air quality aspects of the Buncefield Oil Depot Explosion. 2006.

- Liu, G.; Moore, K.; Su, W.-C.; Delclos, G.L.; De Porras, D.G.R.; Yu, B.; Tian, H.; Luo, B.; Lin, S.; Lewis, G.T. Chemical explosion, COVID-19, and environmental justice: Insights from low-cost air quality sensors. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 849, 157881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, D.J.; McKeown, A.M.; Hall, D.J.; Porter, S. Validation of ADMS against wind tunnel data of dispersion from chemical warehouse fires. Atmospheric Environment 1999, 33, 1937–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, C. Approaches to fire modelling with ADMS. In Proceedings of the ADMS 5 User Group Meeting, Edinburgh; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Biočanin, R.; Stefanov, S.; Urošević, S.; Mekić, S. Modeling of pollutants in the air in terms of fire on dumps/Modelowanie zanieczyszczeń powietrza w warunkach pożaru na wysypisku. Ecological Chemistry and Engineering S 2012, 19, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, B.; Duijm, N.J.; Markert, F. Airborne releases from fires involving chemical waste—A multidisciplinary case study. Journal of hazardous materials 1998, 57, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, R.; Filippi, J.B.; Truchot, B.; Couto, F.T. Local to continental scale coupled fire-atmosphere simulation of large industrial fire plume. Fire safety journal 2022, 134, 103699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthimiou, G.; Andronopoulos, S.; Tavares, R.; Bartzis, J. CFD-RANS prediction of the dispersion of a hazardous airborne material released during a real accident in an industrial environment. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries 2017, 46, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukmirović, Z.B.; Unkašević, M.; Lazić, L.; Tošić, I. Regional air pollution caused by a simultaneous destruction of major industrial sources in a war zone. The case of April Serbia in 1999. Atmospheric Environment 2001, 35, 2773–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leelőssy, Á.; Ludányi, E.L.; Kohlmann, M.; Lagzi, I.; Meszaros, R. Comparison of two Lagrangian dispersion models: a case study for the chemical accident in Rouen, January 21-22, 2013. Időjárás 2013, 117, 435–450. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliaferri, F.; Invernizzi, M.; Capelli, L. A sensitivity analysis applied to SPRAY and CALPUFF models when simulating dispersion from industrial fires. Atmospheric Pollution Research 2022, 13, 101249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainslie, B.; Jackson, P. The use of an atmospheric dispersion model to determine influence regions in the Prince George, BC airshed from the burning of open wood waste piles. Journal of environmental management 2009, 90, 2393–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, H. Modelling the plume from the Buncefield Oil Depot fire. Chemical Hazards and Poisons Report 2006, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Deary, M.E.; Uapipatanakul, S. Evaluation of the performance of ADMS in predicting the dispersion of sulfur dioxide from a complex source in Southeast Asia: implications for health impact assessments. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health 2014, 7, 381–399. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, N.S.; Morawska, L. A review of dispersion modelling and its application to the dispersion of particles: An overview of different dispersion models available. Atmospheric environment 2006, 40, 5902–5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smethurst, H.; Witham, C.; Robins, A.; Murray, V. An exceptional case of long range odorant transport. Journal of wind engineering and industrial aerodynamics 2012, 103, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deary, M.E.; Griffiths, S.D. A novel approach to the development of 1-hour threshold concentrations for exposure to particulate matter during episodic air pollution events. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 418, 126334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO global air quality guidelines, Particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide.; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Chu, C.; Tan, J.; Cao, J.; Song, W.; Xu, X.; Jiang, C.; Ma, W.; Yang, C.; Chen, B. Ambient air pollution and hospital admission in Shanghai, China. Journal of hazardous materials 2010, 181, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behndig, A.; Mudway, I.; Brown, J.; Stenfors, N.; Helleday, R.; Duggan, S.; Wilson, S.; Boman, C.; Cassee, F.R.; Frew, A. Airway antioxidant and inflammatory responses to diesel exhaust exposure in healthy humans. European Respiratory Journal 2006, 27, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greven, F.E.; Krop, E.J.; Spithoven, J.J.; Burger, N.; Rooyackers, J.M.; Kerstjens, H.A.; Van der Heide, S.; Heederik, D.J. Acute respiratory effects in firefighters. American journal of industrial medicine 2012, 55, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swiston, J.R.; Davidson, W.; Attridge, S.; Li, G.T.; Brauer, M.; van Eeden, S.F. Wood smoke exposure induces a pulmonary and systemic inflammatory response in firefighters. European respiratory journal 2008, 32, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J. Syndromic surveillance in the Health Protection Agency. Chemical Hazards and Poisons Report 2010, 17, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Black, C.; Tesfaigzi, Y.; Bassein, J.A.; Miller, L.A. Wildfire smoke exposure and human health: Significant gaps in research for a growing public health issue. Environmental toxicology and pharmacology 2017, 55, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faustini, A.; Alessandrini, E.R.; Pey, J.; Perez, N.; Samoli, E.; Querol, X.; Cadum, E.; Perrino, C.; Ostro, B.; Ranzi, A. Short-term effects of particulate matter on mortality during forest fires in Southern Europe: results of the MED-PARTICLES Project. Occupational and environmental medicine 2015, 72, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haikerwal, A.; Akram, M.; Del Monaco, A.; Smith, K.; Sim, M.R.; Meyer, M.; Tonkin, A.M.; Abramson, M.J.; Dennekamp, M. Impact of fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) exposure during wildfires on cardiovascular health outcomes. Journal of the American Heart Association 2015, 4, e001653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, Z.S.; Hoshiko, S.; Fahimi, J.; Harrison, R.J.; Cascio, W.E.; Rappold, A.G. Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular emergency department visits associated with wildfire smoke exposure in California in 2015. Journal of the American heart association 2018, 7, e007492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, S.E.; Moffat, A.; Gazzard, R.; Baker, D.; Murray, V. Health impacts of wildfires. PLoS currents 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, S.M.; Miller, M.D.; Balmes, J.R. Health effects of wildfire smoke in children and public health tools: a narrative review. Journal of exposure science & environmental epidemiology 2021, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wegesser, T.C.; Pinkerton, K.E.; Last, J.A. California wildfires of 2008: coarse and fine particulate matter toxicity. Environmental health perspectives 2009, 117, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhui, K.; Newbury, J.B.; Latham, R.M.; Ucci, M.; Nasir, Z.A.; Turner, B.; O’Leary, C.; Fisher, H.L.; Marczylo, E.; Douglas, P. Air quality and mental health: evidence, challenges and future directions. BJPsych open 2023, 9, e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zhou, J.; Li, M.; Huang, J.; Dou, D. Urbanites’ mental health undermined by air pollution. Nature Sustainability 2023, 6, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Review of evidence on health aspects of air pollution: REVIHAAP project: technical report. In Review of evidence on health aspects of air pollution: REVIHAAP project: technical report; 2013.

- Simpson, R.W.; Williams, G.; Petroeschevsky, A.; Morgan, G.; Rutherford, S. Associations between outdoor air pollution and daily mortality in Brisbane, Australia. Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal 1997, 52, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G.; Corbett, S.; Wlodarczyk, J. Air pollution and hospital admissions in Sydney, Australia, 1990 to 1994. American journal of public health 1998, 88, 1761–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaels, R.A.; Kleinman, M.T. Incidence and apparent health significance of brief airborne particle excursions. Aerosol Science & Technology 2000, 32, 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, R.A. Airborne particle excursions contributing to daily average particle levels may be managed via a 1 hr standard, with possible public health benefits. Aerosol Science and Technology 1996, 25, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. Access Acute Exposure Guideline Levels (AEGLs) Values. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/aegl/access-acute-exposure-guideline-levels-aegls-values#chemicals (accessed on 27/03/2019).

- American Industrial Hygiene Association. Current ERPG® Values (2016). 2016.

- Stieb, D.M.; Burnett, R.T.; Smith-Doiron, M.; Brion, O.; Shin, H.H.; Economou, V. A new multipollutant, no-threshold air quality health index based on short-term associations observed in daily time-series analyses. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2008, 58, 435–450. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Elshout, S.; Léger, K.; Nussio, F. Comparing urban air quality in Europe in real time: A review of existing air quality indices and the proposal of a common alternative. Environment International 2008, 34, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airly. Air Quality Index CAQI and AQI – Methods of Calculation. Available online: https://airly.org/en/air-quality-index-caqi-and-aqi-methods-of-calculation/ (accessed on May).

- US Federal Register. National ambient air quality standards for particulate matter. Final Rule. 2013.

- Perlmutt, L.D.; Cromar, K.R. Comparing associations of respiratory risk for the EPA Air Quality Index and health-based air quality indices. Atmospheric environment 2019, 202, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunt, H.; Russell, D. Public health risk assessment and air quality cell for a tyre fire, Fforestfach, Swansea. Chemical Hazards and Poisons Report 2012, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, M.L.; Zanobetti, A.; Dominici, F. Evidence on Vulnerability and Susceptibility to Health Risks Associated With Short-Term Exposure to Particulate Matter: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American journal of epidemiology 2013, 178, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makri, A.; Stilianakis, N.I. Vulnerability to air pollution health effects. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2008, 211, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, R.; Flacke, J.; Martinez, J.; Van Maarseveen, M. Environmental Health Related Socio-Spatial Inequalities: Identifying “Hotspots” of Environmental Burdens and Social Vulnerability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2016, 13, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badjagbo, K.; Sauvé, S.; Moore, S. Real-time continuous monitoring methods for airborne VOCs. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2007, 26, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Qin, M.; Sun, W.; Fang, W.; Sun, Y.; Gao, L.; Xie, P.; Duan, J.; Wang, D.; Lu, X. Cruise observation of SO2, NO2 and benzene with mobile portable DOAS in the industrial park. Guang pu xue yu Guang pu fen xi= Guang pu 2016, 36, 1936–1940. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Riad, M.M.; Sabry, Y.M.; Khalil, D. On the detection of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) using machine learning and FTIR spectroscopy for air quality monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2019 36th National Radio Science Conference (NRSC); 2019; pp. 386–392. [Google Scholar]

- Farooqui, Z.; Biswas, J.; Saha, J. Long-Term Assessment of PurpleAir Low-Cost Sensor for PM2. 5 in California, USA. Pollutants 2023, 3, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.L.; Goodman, N.; Vardoulakis, S. Five Years of Accurate PM2. 5 Measurements Demonstrate the Value of Low-Cost PurpleAir Monitors in Areas Affected by Woodsmoke. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 7127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Doraiswamy, P.; Levy, R.; Pikelnaya, O.; Maibach, J.; Feenstra, B.; Polidori, A.; Kiros, F.; Mills, K. Impact of California fires on local and regional air quality: The role of a low-cost sensor network and satellite observations. GeoHealth 2018, 2, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Ruiz-Suarez, S.; Reich, B.J.; Guan, Y.; Rappold, A.G. A Data-Fusion Approach to Assessing the Contribution of Wildland Fire Smoke to Fine Particulate Matter in California. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragbir, P.; Kaduwela, A.; Passovoy, D.; Amin, P.; Ye, S.; Wallis, C.; Alaimo, C.; Young, T.; Kong, Z. UAV-based wildland fire air toxics data collection and analysis. Sensors 2023, 23, 3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiber, C.; Nowlin, D.; Landowski, B.; Tolentino, M.E. Tracking hazardous aerial plumes using IoT-enabled drone swarms. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 4th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT); 2018; pp. 377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart-Evans, J.; Kibble, A.; Mitchem, L. An evidence-based approach to protect public health during prolonged fires. International Journal of Emergency Management 2016, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart-Evans, J.; Hall, L.; Czerczak, S.; Manley, K.; Dobney, A.; Hoffer, S.; Pałaszewska-Tkacz, A.; Jankowska, A. Assessing and improving cross-border chemical incident preparedness and response across Europe. Environment international 2014, 72, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Emission rates (mg kg-1 unless otherwise stated) for different categories of substance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material burning | VOCs | sVOCS | Carbonyls | PAHs | PCDDs/Fs |

| Fuel oil | Benzene, 1022; toluene,42; ethyltoluenes,22; xylenes, 25; 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene, 32. | Not listed | Formaldehyde, 303; acetaldehyde, 63; acrolein, 39; acetone, 35; benzaldehyde, 104. | Naphthalene, 162; acenaphthylene, 99; fluoranthene, 20; 1-methylfluorene, 26; anthracene, 15. | HpCDD, 7.07 x 10-5; OCDD, 1.34 x 10-4; TCDF, 2.05 x 10-4; HxCDF, 1.86 x 10-5 (data for crude oil). |

| Household waste | Benzene 980; styrene 527 ; toluene 372 ; ethylbenzene 182 ; chloromethane 163. |

Phenol 113 ; 3- or 4-cresol 44.1 ; 2-cresol 24.6 ; bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate 23.8 ; isophorone 9.3. | Formaldehyde 444 ; acetaldehyde 428 ; acetone 254 ; benzaldehyde 152 ; propionaldehyde 113. | Naphthalene 11.4 ; phenanthrene 5.3 ; fluorine 3.0 ; fluoranthene 2.8 ; chrysene 1.8. | Total PCDD/Fs: 5.8 x 10-3; TEQ‡ PCDD/Fs: 7.7 x 10-5; |

| Burning of scrap tyres | Benzene, 2180; toluene, 1368; styrene, 653; ethylbenzene, 378; limonene, 460. | Phenol, 533; 1-methylnaphthalene, 279; 2-methylnaphthalene, 390; bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate, 23.8; isophorone, 9.3. | Formaldehyde, 444; acetaldehyde, 428; acetone, 254; benzaldehyde, 152; propionaldehyde, 113. | Acenaphthene, 1368; naphthalene, 651; phenanthrene, 245; fluoranthene, 398; pyrene, 93. | Not listed |

| Automobile shredder residue | Toluene, 10690; benzene, 9584; styrene, 6528; ethylbenzene, 4964; chlorobenzene, 1718. | Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, 2058; benzenebutanenitrile, 3340; phenol, 990; benzaldehyde, 1690; 1,2-dichlorobenzene, 110. |

Not listed | Naphthylene, 883.3; acenaphthylene, 150.0; fluorene, 38.0; phenanthrene, 231.3; anthracene, 35.7. | TCDD; PeCDF, 1.40; TCDF, 1.80; HxCDF, 0.40; PeCDD, 0.30. |

| Wood burning (tropical forest) | Benzene, 400; toluene, 250; acetonitrile, 180; methyl chloride, 100; xylenes, 60. | Furan, 480; 2-methylfuran, 170; 3-furfural, 370; 2,5-dimethylfuran, 30; 3-methylfuran, 3. | Formaldehyde, 1400; methanol, 2000; acetaldehyde, 650; acetone, 620; 2,3-butanedione, 920; acrolein, 180. | Total PAHs, 25.0. | Total PCDDs/Fs, 0.0067) |

| Incident or fire type | Details | Airborne pollutants and concentrations (if known) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burning of polymeric materials | Qualitative data from a review of such fires |

CO, HCN, HCl/HBr/HF, NOx, SO2, organic irritants (acrolein/formaldehyde), inorganic irritants (phosgene/ammonia), PAHs, PCDD/Fs, PM (bold indicates likelihood of high concentrations relative to standards). | [14] |

| Burning of wood materials | Qualitative data from a review of such fires | NOx, acrolein/formaldehyde, PAHs, PCDD/Fs, PM | [14] |

| Burning of rubber tyres | Qualitative data from a review of such fires |

CO, HCN, HCl/HBr/HF, NOx, SO2, P2O5, organic irritants (acrolein/formaldehyde), inorganic irritants (phosgene/ammonia), PAHs, PCDD/Fs, PM (bold indicates likelihood of high concentrations relative to standards). | [14] |

| Burning of oil and petrol | Qualitative data from a review of such fires | SO2, organic irritants (acrolein/formaldehyde), PAHs, PCDD/Fs, PM (bold indicates likelihood of high concentrations relative to standards). | [14] |

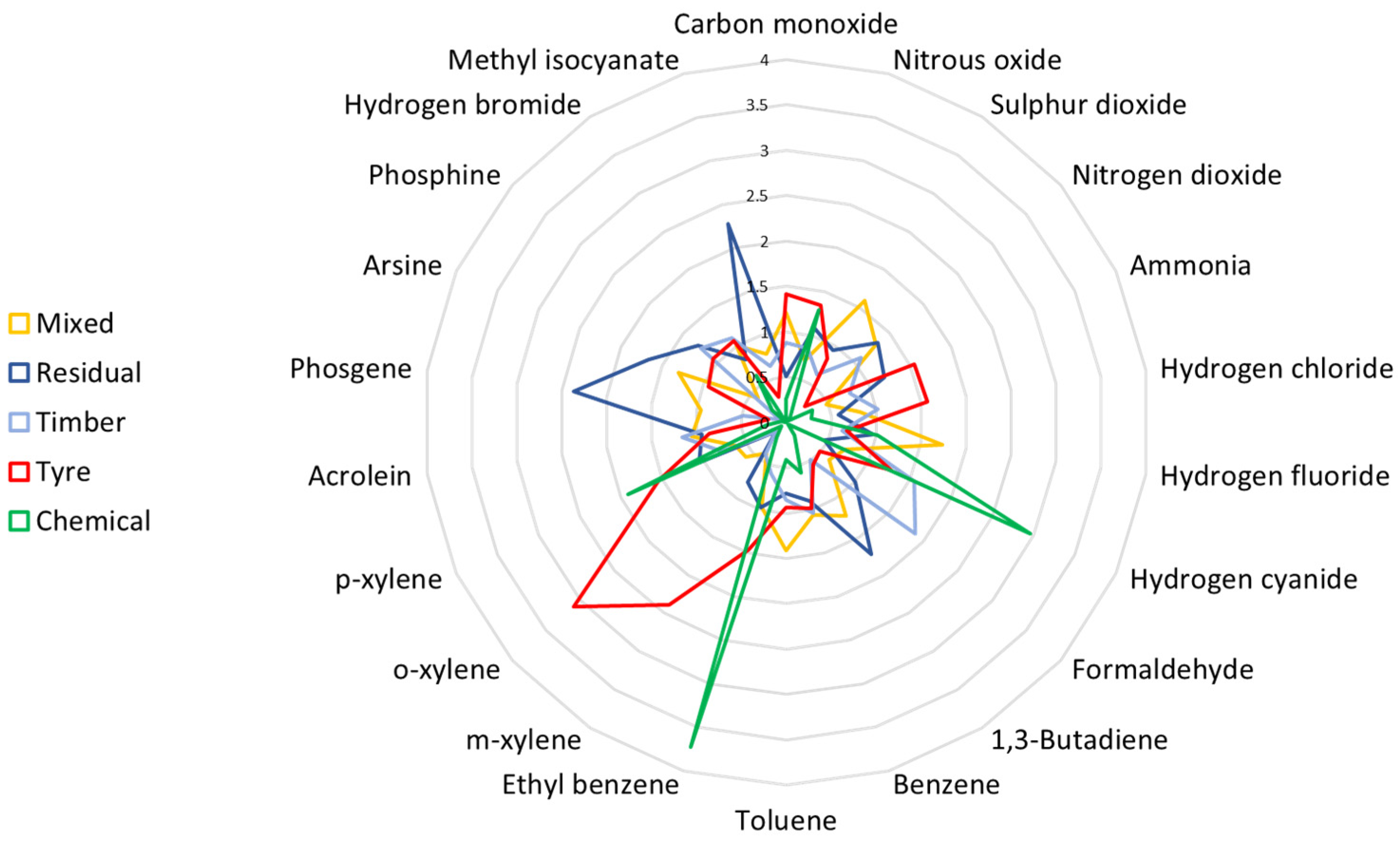

| Tyre fires | Based on ambient monitoring carried out as part of the UK’s AQinMI service | Incident-mean concentrations (ppb for gases and µg m-3 for PM) with the maximum 1 min concentration in parentheses: CO, 0.58 (3.01); HCN, 0.09 (0.48); ammonia, 0.22 (1.07); HBr, 0.53 (2.76); HCl, 0.05 (0.47); HF, 0.02 (0.28); NO, 0.23 (0.42); NO2, 0.03 (0.74); phosgene, 0.01 (0.24); SO2, 0.08 (0.7); benzene, 0.16 (1.13); 1,3-butadiene, 0.03 (1.45); ethyl benzene, 0.08 (1.31); formaldehyde, 0.03 (0.2); methyl isocyanate, 0.02 (0.22); m-xylene, 0.02 (0.62); o-xylene, 0.1 (1.5); p-xylene, 0.09 (0.72); toluene, 0.16 (3.74); arsine, 0.02 (0.12); PM10, 115 (6527); PM2.5, 27.8 (652) | [1,5]‡ |

| Fires involving mixed recycling | Based on ambient monitoring carried out as part of the UK’s AQinMI service | Incident-mean concentrations (ppb for gases and µg m-3 for PM) with the maximum 1 min concentration in parentheses: CO, 0.78 (10.7); HCN, 0.17 (46.1); ammonia, 0.14 (4.74); HBr, 0.66 (5.66); HCl, 0.07 (66.2); HF, 0.08 (5.56); NO, 0.14 (2.32); NO2, 0.11 (0.77); phosgene, 0.17 (0.85); SO2, 0.68 (2.52); benzene, 0.2 (15.5); 1,3-butadiene, 0.49 (3.15); ethyl benzene, 0.1 (8.54); formaldehyde, 0.12 (0.88); methyl isocyanate, 0.01 (0.46); o-xylene, 0.01 (0.7); p-xylene, 0.23 (1.48); toluene, 0.36 (3.76); arsine, 0.01 (0.79); PM10, 83 (6527); PM2.5, 24.4 (652) | [1,5]‡ |

| Fires involving timber | Based on ambient monitoring carried out as part of the UK’s AQinMI service | Incident-mean concentrations (ppb for gases and µg m-3 for PM) with the maximum 1 min concentration in parentheses: CO, 0.48 (12.3); HCN, 0.23 (24.7); ammonia, 0.16 (11); HBr, 0.7 (44.3); HCl, 0.06 (11.2); HF, 0.07 (7.81); NO, 0.07 (2.21); NO2, 0.5 (147); phosgene, 0.25 (17.7); SO2, 0.09 (9.51); benzene, 0.24 (6.93); 1,3-butadiene, 0.16 (23.9); ethyl benzene, 0.08 (6.81); formaldehyde, 0.44 (23.5); methyl isocyanate, 0.01 (0.35); m-xylene, 0 (0.98); o-xylene, 0.01 (1.28); p-xylene, 0.2 (6.27); toluene, 0.34 (23.2); arsine, 0 (1.76); PM10, 28 (848); PM2.5, 12.6 (306) | [1,5]‡ |

| Fires involving WEEE materials | Based on ambient monitoring carried out as part of the UK’s AQinMI service | Incident-mean concentrations (ppb for gases and µg m-3 for PM) with the maximum 1 min concentration in parentheses: CO, 0.41 (2.58); HCN, 0.05 (0.49); ammonia, 0.03 (0.18); HBr, 0.52 (2.34); HCl, 0.02 (0.22); HF, 0.07 (0.31); NO, 0.04 (0.32); NO2, 0.04 (0.32); phosgene, 0.06 (0.39); SO2, 0.29 (0.82); benzene, 0.38 (1.34); 1,3-butadiene, 0.1 (0.73); ethyl benzene, 0.0 (0.07); formaldehyde, 0.02 (0.25); methyl isocyanate, 0.0 (0.0); m-xylene, 0.0 (0.08); o-xylene, 0.0 (0.0); p-xylene, 0.0 (0.0); toluene, 0.75 (1.78); arsine, 0.02 (0.13); PM10, 37.9 (174); PM2.5, 31.6 (154) | [1,5]‡ |

| Fires involving residual recycling materials | Based on ambient monitoring carried out as part of the UK’s AQinMI service | Incident-mean concentrations (ppb for gases and µg m-3 for PM) with the maximum 1 min concentration in parentheses: CO, 0.37 (16.3); HCN, 0.13 (17.4); ammonia, 0.25 (10.5); HBr, 0.98 (31.3); HCl, 0.03 (7.02); HF, 0.05 (2.48); NO, 0.11 (0.48); NO2, 0.44 (4.33); phosgene, 1.43 (9.23); SO2, 0.06 (0.69); benzene, 0.2 (4.21); 1,3-butadiene, 0.27 (25); ethyl benzene, 0.11 (3.04); formaldehyde, 0.15 (4.96); methyl isocyanate, 0.2 (1.45); m-xylene, 0.01 (0.86); p-xylene, 0.24 (4.91); toluene, 0.31 (9.02); arsine, 0.12 (0.9); PM10, 136.9 (6141); PM2.5, 79.1 (652) | [1,5]‡ |

| Landfill fires | Various controlled and uncontrolled landfill sites: the soils and vegetation adjacent to these sites were sampled for PAHs, and PCBs that had settled with the PM from the plume | Total PAHs ranged up to 300,000 µg kg-1 dry weight (dw), though typically concentrations were in the thousands of µg kg-1 (compared to reference concentrations ranging from 12 to 112 µg kg-1. PCDD/Fs total PCB concentrations ranged from 0.2 to 7,900 µg kg-1 dw. | [15] |

| Open-cut coal-mine fire in Latrobe, Victoria, Australia, February 2014 | Burned for 45 days, creating a dense plume that affecting ca. 45,000 residents in local towns. The most affected location was the nearest town of Morwell, 0.5 km from the mine. | Concentrations given are ranges observed during fire at the most affected location: PM2.5 5.4-731 µg m-3 for 24-h averaging period), CO (0-17.4 ppm); NO2 (2-44 ppb), SO2 (0-35 ppb); benzene (1.1-14 ppb for 24-h averaging period), toluene (0.5-4.8 ppm for 24-h averaging period), ethylbenzene (0.5-0.6 ppb for 24-h averaging period), xylenes (0.18-0.56 ppb for 7-d averaging period). 1,3-butadiene (0.5-2.5 ppb for 24-h averaging period), formaldehyde (1.4-7.6 ppb), B(a)P (0.1-8.2 ng m-3). | [16] |

| Fire at International Terminals Company Deer Park Chemical plant, Harris County, Texas, USA | Fire affected several tanks containing naphtha and xylene and burned for 3 days. |

benzene (highest recorded value of 32,000ppb in the industrial area, but measurements in the hundreds of ppb in other locations), isoprene (up to 1000 ppb), 1,3-butadiene (up to 1700 ppb), H2S (69.7 to 119.2 ppb) | [4] |

| Fire at a naphtha cracking complex of a petrochemical complex in Yunling County, Taiwan in May 2011. | Fire burned for 10 hours. The site is adjacent to a residential area of 61,600 people. | Ehylene (57 ppb), propane (7 ppb), butane (6 ppb), toluene (2 ppb), benzene (21 ppb), vinyl chloride monomer (389 ppb), 1,3-butadiene (35 ppb). | [17] |

| Landfill fire in Sweden | Test site at which there was a controlled fire for monitoring purposes, but where an unplanned fire also broke out. Monitoring was carried out for both. | Total PAHs 810 ng m-3, total PCBs, 590 ng m-3, PCDD/Fs 2.88 to 20.54 ng m-3 (0.051 to 0.427 ng m-3TEQ). | [15,18,19] |

| Fire at a pool chemical manufacturing facility in Guelph, Ontario, Canada in August 2000 | Initial explosion at the factory, followed by a fire that lasted for over 60-h |

HCl, average over the survey period was 22 µg m-3, with a maximum instantaneous value of 350 µg m-3 and chlorine gas were monitored over the period of the fire. For Cl2 the average was 12 µg m-3, with a maximum of 570 µg m-3. | [20] |

| Fire at oil storage depot at Buncefield, Hertfordshire, UK in December 2005. | The fire burned for 5 days, though the high combustion temperature gave rise to a very buoyant plume that crossed to mainland Europe. | m-and p-Xylene 230 ppb, o-xylene 140 ppb, toluene 160 ppb, benzene 170 ppb, ethyl benzene 82 ppb, PM10 1000 µg m-3. | [1,5] |

| Fire at Bellolampo Landfill, Palermo, Sicily, Italy | Fire extended to a surface area of up to 120,000 m2 and lasted 18 days. | Ambient monitoring stations recorded an average of 50 µg m-3 PM10 over the first 24-h, falling to 20 µg m-3 thereafter. Elevated air and soil concentrations of dioxins were determined in soil exposed to the plume, as well as in milk samples in affected farms. Elevated heavy metals concentrations detected in soils. | [21] |

| Dispersion models (categorised by type) | Summary of study and results | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | ||

| ADMS (Atmospheric Dispersion Modelling System) | This was the simulation of the release of pollutants from a chemical warehouse fire that was contained within the building and where the emissions from a buoyant plume were made through roof vents and doors. The effect of the ADMS building module was studied. The results were compared to wind tunnel tests. | [36] |

| ADMS | Simulation of a fire at a car recycling plant. Particular focus was on parameters used, e.g., source temperature, area, exit velocity and emission rate. The best performance against monitoring data was for an area source. | [37] |

| UK CHEMET | Routinely used, particularly in the early phase of a fire to track the dispersion of plumes from fires or chemical releases. Basic model that calculates plume path. Larger incidents may also be modelled using NAME (see below). | [1,5] |

| EPA Screen Model; 3 | Simulation of worst case scenario for ground level concentrations of pollutants from an uncontrolled tyre dump fire (mg m-3): CO (674), PM (652) and PAH (24) concentrations 500m downwind of the fire. | [38] |

| General Gaussian plume model after first calculating the plume rise. | The study aimed to simulate concentrations of airborne contaminants in adjacent areas in the case of a fire at a chemical and pharmaceutical plant in Denmark. A range of different meteorological conditions were modelled. | [39] |

| CFD | ||

| CFD code coupled with a mesoscale metreological model | Simulation of PM emission during a hypothetical industrial fire. The CFD component was used to accurately parameterize the fire and developing plume, which was then modelled on a meso-scale using the meteorological model. The results were compared to a system where the CFD component was replaced by the ForeFire model. | [40] |

| CFD-RANS (Computational Fluid Dynamics Reynolds-Averaged Navier Stokes) | CFD-RANS was used to calculate dispersion for the accidental release of 900Kg of vinyl chloride monomer at an industrial facility. Modelling was restricted to the chemical facility boundaries, comparing the predicted concentrations with real monitoring data. Performance was considered satisfactory, especially given that there were uncertainties in wind direction. | [41] |

| Eulerian | ||

| TAPM (The Air Pollution Model, CSIRO), combined with a Chemical Transport Model | Open-cut coal mine fire in Latrobe, Victoria, Australia. Allowed the calculation of personalized mean 24-h (0-56 µg m-3) and peak 12-h (0-879 µg m-3) PM2.5 exposure for a range of participants who were also asked about health effects of the fire. | [6] |

| Lagrangian | ||

| HYSPLIT (Hybrid Single Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory) | Fire at a naphtha cracking complex of a petrochemical complex in Yunling County, Taiwan in May 2011. Used back-trajectory model to trace monitored pollutants (propane, butane, toluene, benzene, vinyl chloride, 1,3-butadiene to the source of the fire from distances up to 10km. | [17] |

| HYSPLIT | Fire following bombing of industrial facilities in Serbia during the Kosovo war. Used in back-trajectory mode to identify the likely source of elevated concentrations of aerosol-bound PAHs, dioxins, and furans that were detected in Greece. | [42] |

| HYSPLIT | Modelling dispersion of pollutants at a fire involving six tanks of a 179-tank fuel storage facility in port of Santos, Brazil. Used in forward mode to calculate trajectories for the fire, with results showing that the plume was mainly carried out to sea, explaining the relatively small increases in PM10 observed at monitoring stations in the city. | [24] |

| HYSPLIT and PyTREX | Accidental release of methyl mercaptan from a chemical works in Rouen, France. Unknown emission rate, so a nominal concentration was modelled in forward mode to try and explain the very geographically and temporally separated reports of odour nuisance (in Paris and London and over a period of more than 24 hours). Both models gave similar results. | [43] |

| HYSPLIT | Fire at a chemical plant in Houston, Texas. Used in forward mode to predict a range of possible trajectories of the plume and identify which monitoring stations would have been subject to elevated airborne pollutants from the fire. | [4] |

| CALPUFF and SPRAY | Hypothetical refinery fire. Sensitivity analysis of the key model parameters that might affect the calculation of ground level concentrations of a (tracer) gas. Of the model parameters tested (source diameter, temperature, height and exit velocity), diameter was found to be the most sensitive. | [44] |

| CALPUFF | Burning of wood waste from trees killed by the Mountain Pine Beetle, British Columbia, Canada. Modelled the meteorological conditions, and distances from the centre of the city of Prince George, where wood burning could be permitted (based upon exceedances of the Canada standard for PM2.5). | [45] |

| ADMS-Star | Tyre fire at Mexborough, UK in 2010. Used back-calculation method to estimate emission rates. Predicted 24-h average concentrations for those exposed to the plume. Estimated that 7856 residents may have been exposed to PM10 concentrations in the US EPA AQI category of ‘Hazardous’ (>425 µg m-3). | [7] |

| NAME | Fire at fuel storage site (20 tanks) at Buncefield, Hertfordshire, UK. Used a nominal concentration of tracer gas in the model to allow calculation of the dispersion in three dimensions. Accurately modelled plume rise and geographical spread. Corroborated by satellite imagery. | [46] |

| Limit or guideline | 24-h concentration / µg m-3 | Derived 1-h concentration / µg m-3 (if available) |

|---|---|---|

| PM10 | ||

| CAQI‡ Low | 12 | 25‡ |

| CAQI Medium | 25 | 50‡ |

| CAQI High | 50 | 90‡ |

| CAQI Very High | 100 | 180‡ |

| WHO AQG⁕ | 45 | - |

| WHO Interim Target 4 / EU 24-h guideline | 50 | - |

| WHO Interim Target 3 | 75 | 109† |

| WHO Interim Target 2 | 100 | 146† |

| WHO Interim Target 1 | 150 | |

| US EPA AQI 100: Unhealthy for sensitive groups | 155 | 227† |

| US EPA AQIΨ 150: Unhealthy | 255 | 427† |

| US EPA AQI 200: Very unhealthy | 355 | 707† |

| US EPA AQI 300: Hazardous | 425 | 945† |

| UK threshold for evacuation | 320 | 510† |

| PM2.5 | ||

| CAQI Low | 10 | 15‡ |

| CAQI Medium | 20 | 30‡ |

| CAQI High | 30 | 55‡ |

| CAQI Very High | 60 | 110‡ |

| WHO AQG | 15 | - |

| WHO Interim Target 4 / EU 24-h guideline | 20 | - |

| WHO Interim Target 3 | 30 | 48† |

| WHO Interim Target 2 | 50 | 63† |

| WHO Interim Target 1 | 70 | 93† |

| US EPA AQI 100: Unhealthy for sensitive groups | 35 | 45† |

| US EPA AQI 150: Unhealthy | 55.5 | 70† |

| US EPA AQI 200: Very unhealthy | 150.5 | 183† |

| US EPA AQI 300: Hazardous | 250 | 345§ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).