Submitted:

06 June 2024

Posted:

07 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Fabeae

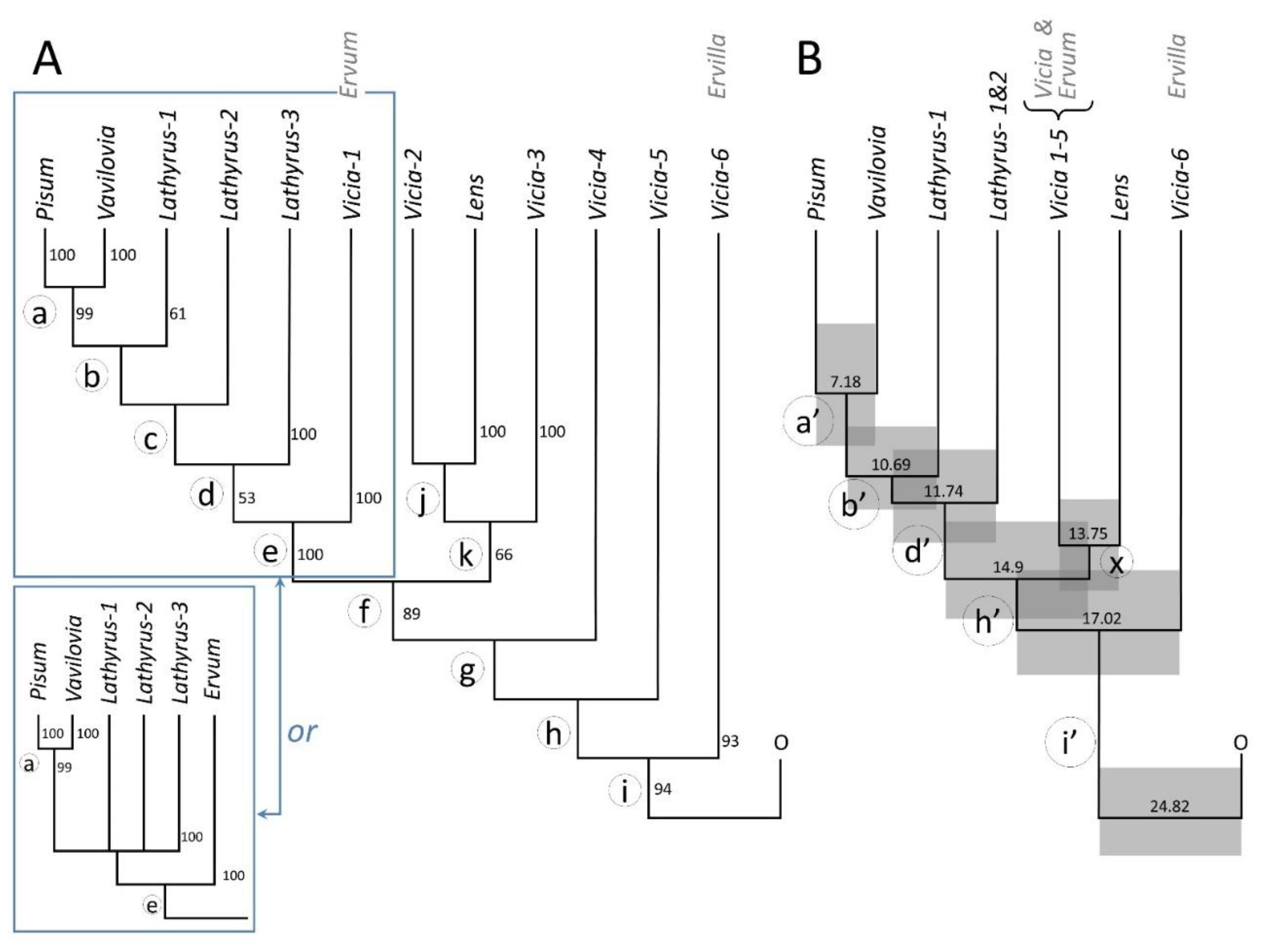

2.1. The Consensus Maximum Likelihood (ML) Phylogeny

2.2. The Chronogram

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lewis, G.P.; Schrire, B.; Mackinder, B.; Lock, M. Legumes of the World. Kew Publishing, Kew, UK. 2005.

- Azani, N.; Babineau, M.; Bailey, C.D.; Banks, H.; Barbosa, A.R.; Pinto, R.B.; Boatwright, J.S.; Borges, L.M.; Brown, G.K.; Bruneau, A.; Candido, E.; Cardoso, D.; Chung, K.; Clark, R.P.; Conceição, A.d.S.; Crisp, M.; Cubas, P.; Delgado-Salinas, A.; Dexter, K.G.; Doyle, J.J.; Duminil, J.; Egan, A.N.; de la Estrella, M.; Falcão, M.J.; Filatov, D.A.; Fortuna-Perez, A.P.; Fortunato, R.H.; Gagnon, E.; Gasson, P.; Rando, J.G.; de Azevedo Tozzi, A.M.G.; Gunn, B.; Harris, D.; Haston, E.; Hawkins, J.A.; Herendeen, P.S.; Hughes, C.E.; Iganci, J.R.V.; Javadi, F.; Kanu, S.A.; Kazempour-Osaloo, S.; Kite, G.C.; Klitgaard, B.B.; Kochanovski, F.J.; Koenen, E.J.M.; Kovar, L.; Lavin, M.; le Roux, M.; Lewis, G.P.; de Lima, H.C.; López-Roberts, M.C.; Mackinder, B.; Maia, V.H.; Malécot, V.; Mansano, V.F.; Marazzi, B.; Mattapha, S.; Miller, J.T.; Mitsuyuki, C.; Moura, T.; Murphy, D.J.; Nageswara-Rao, M.; Nevado, B.; Neves, D.; Ojeda, D.I.; Pennington, R.T.; Prado, D.E.; Prenner, G.; de Queiroz, L.P.; Ramos, G.; Filardi, F.L.R.; Ribeiro, P.G.; de Lourdes Rico-Arce, M.; Sanderson, M.J.; Santos-Silva, J.; São-Mateus, W.M.B.; Silva, M.J.S.; Simon, M.F.; Sinou, C.; Snak, C.; de Souza, É.R.; Sprent, J.; Steele, K.P.; Steier, J.E.; Steeves, R.; Stirton, C.H.; Tagane, S.; Torke, B.M.; Toyama, H.; da Cruz, D.T.; Vatanparast, M.; Wieringa, J.J.; Wink, M.; Wojciechowski, M.F.; Yahara, T.; Yi, T. and Zimmerman, E. A new subfamily classification of the Leguminosae based on a taxonomically comprehensive phylogeny: The Legume Phylogeny Working Group (LPWG). Taxon. 2017, 66, 44-77. [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, M.F.; Sanderson, M.J.; Hu, J.M., Evidence on the monophyly of Astragalus (Fabaceae) and its major subgroups based on nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS and chloroplast DNA trnL intron data. Syst. Bot. 1999, 24, 409–437. [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Li, S-J.; Su, C.; Sirichamorn, Y.; Han, L-N.; Ye, W.; Lôc, P.K.; Wen, J.; Compton, J.A.; Schrire, B.; Nie, Z-L.; Chen, H.K. Phylogenomic framework of the IRLC legumes (Leguminosae subfamily Papilionoideae) and intercontinental biogeography of tribe Wisterieae. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2021, 163, 107235. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.; Guo, W.; Gupta, S.; Fan, W.; Mower, J.P. (2016), Evolutionary dynamics of the plastid inverted repeat: the effects of expansion, contraction, and loss on substitution rates. New Phytol, 2016, 209, 1747-1756. [CrossRef]

- Choi, I-S.; Jansen, R.; Ruhlman, T. Lost and Found: Return of the Inverted Repeat in the Legume Clade Defined by Its Absence, Genome Biology and Evolution. 2019, 11, 1321–1333. [CrossRef]

- Kupicha, F.K., Vicieae. In "Advances in Legume Systematics". Eds. R.M. Polhill and P.M. Raven. pp. 377-381. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. (1981).

- Schaefer, H.; Hechenleitner, P.; Santos-Guerra, A.; Menezes de Sequeira, M.; Pennington, R.T.; Kenicer, G. and Carine, M.A. Systematics, biogeography, and character evolution of the legume tribe Fabeae with special focus on the middle-Atlantic island lineages. BMC Evol. Biol. 2012, 12, 250. [CrossRef]

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. The World Checklist of Vascular Plants (WCVP): Fabaceae. (2023) Checklist dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/mvhaj3 accessed via GBIF.org on 09/05/2024.

- Ferguson, M.E.; Maxted, N.; van Slageren, M.V. and Robertson, L.D. () A re-assessment of the taxonomy of Lens Mill. (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae, Vicieae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2000, 133: 41-59. [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, T., Abbo, S., Sherman, A., Coyne, C., Saranga, Y., Lev-Yadun, S., Main, D., Zheng, P. and Ophir, R. Limited divergent adaptation despite a substantial environmental cline in wild pea, Mol. Ecol. 2020, 29, 4322–4336.. [CrossRef]

- Timo Hellwig, Shahal Abbo, Amir Sherman, Ron Ophir, Prospects for the natural distribution of crop wild-relatives with limited adaptability: The case of the wild pea Pisum fulvum, Plant Science. 2021, 310, 110957. [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, T., Abbo, S. and Ophir R. Phylogeny and disparate selection signatures suggest two genetically independent domestication events in pea (Pisum L.) Plant J. 2022, 110, 419–439. [CrossRef]

- Kenicer G. and Parsons R. Lathyrus the complete guide Royal Horticultural Society, Peterborough (2021).

- Rix, M., Nesbitt, M. & King, C. 1063. Lathyrus oleraceus Lam. Curtis's Botanical Magazine, 2023, 40, 197–205. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Kosterin, O. E. Abyssinian pea (Lathyrus schaeferi Kosterin nom. Nov. pro Pisum abyssinicum A. Br.) is a problematic taxon. Vavilovskii Zhurnal Genetiki i Selektsii Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2017, 21, 158–169. [CrossRef]

- https://www.webofscience.com/wos/alldb/basic-search accessed 19/05/20024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).