1. Introduction

Yatapoxviruses are a small group of

Chordopoxvirinae that are pathogenic to primates, including humans. The Yatapoxvirus genus includes Yaba monkey tumor virus (YMTV) and Tanapox virus (TPV) [

1]. Previously, Yaba-like disease virus (YLDV) was considered a third member; however, its genome shares 98.68% sequence identity with TPV, and can be considered a different variant of the same virus [

2]. The genomes of YMTV and TPV share 75% sequence identity [

3]. TPV was first isolated from human skin biopsies during a TPV outbreak in 1957 in Tana River Valley, Kenya [

4,

5]. YMTV was first isolated from an outbreak of subcutaneous tumors in monkeys in Yaba, Nigeria, in 1958 [

6]. Yatapoxvirus genomes are A+T rich and range in size from 135-145 kb [

2,

3,

7,

8]. TPV and YMTV exhibit differences in disease presentations. TPV infection is characterized by vesicular skin lesions, whereas YMTV infection produces a localized histiocyte-filled tumor (histiocytomas) [

9].

While both TPV and YMTV infect a wide range of primates, they appear to exhibit host specificity. Serological surveys have indicated that TPV is endemic in African and Malaysian monkeys, but not in Indian rhesus macaques or New World monkeys [

4,

5,

10]. Human Tanapox disease is considered endemic to several regions of Africa and causes febrile illness and vesicular skin lesions similar to those produced in non-human primates. Sporadic cases have been identified in 30 locations spanning 6,000 kilometers from Sierra-Leone to Tanzania, with larger outbreaks occurring from time to time [

11]. Similarly, antibodies against YMTV have been found in great apes and Old World monkeys but not in New World monkeys and Indian rhesus macaques [

10]. A serological survey of 456 primate sera including 26 chimpanzees, 326 Old World monkeys (African green monkeys, patas monkeys, baboons, colobus monkeys, rhesus macaques), and 104 New World monkeys (spider monkeys, squirrel monkeys, owl monkeys, marmosets, and capuchin monkeys) indicated that antibodies against YMTV were evident in chimpanzees and Old-World monkeys but not in any of the New World monkeys [

10].

Following experimental subcutaneous inoculation with YMTV, tumor-like masses were detected in Asiatic rhesus macaques (

Macaca mulatta,

Macaca irus and

Macaca speciosa) but not in African green monkeys, mangabey monkeys, patas monkeys, mice, rats, rabbits and guinea pigs [

6,

9,

12], indicating host specificity. While no natural infection of YMTV in humans has been reported, infection of human volunteers as well as an accidental infection of a laboratory worker have resulted in the development of mild histiocytomas [

13]. Despite the threat posed to human health, the factors determining the host range of yatapoxviruses are poorly understood. In addition, vaccination with vaccinia virus does not appear to protect against yatapoxvirus infections [

13,

14]. Thus, it is important to study factors that determine the host range of yatapoxviruses.

A major determinant for the tropism of many viruses is the attachment and entry via host-specific cell receptors [

15]. However, as poxviruses use ubiquitous cell surface receptors for entry, it is believed that evasion of the innate immune response post-entry is a more important determinant of poxvirus tropism [

16,

17]. Protein Kinase R (PKR) is a prominent host restriction factor against poxvirus infection (Reviewed in [

18]). PKR exists in a monomeric inactive form and is activated upon binding to double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) produced during infection by most viruses, which leads to PKR dimerization and autophosphorylation. Activated PKR phosphorylates the alpha subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2) [

19]. Phosphorylated eIF2⍺ has a high binding affinity for the regulatory core of the guanine nucleotide exchange factor eIF2B and prevents eIF2B from catalyzing GDP-GTP exchange to eIF2⍺ [

20]. As GTP-bound eIF2 is required for translation initiation, the resulting low availability of GTP-eIF2 leads to the shut off of cap-dependent protein synthesis, including that of viral proteins. To overcome the antiviral effects of PKR activity, most poxviruses encode two PKR inhibitors, named E3 and K3 in vaccinia virus. E3 binds dsRNA and prevents PKR dimerization, whereas K3 inhibits PKR by acting as a pseudosubstrate for the eIF2α binding site [

21,

22,

23,

24].

It was previously shown that inhibition of host PKR by K3 orthologs of several poxvirus families was a key determinant of host specificity [

22,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Vaccinia virus lacking the E3L gene (VACV△E3L) but maintaining the K3L gene was unable to replicate in HeLa cells but remained replication competent in BHK21 cells, suggesting a role for K3 in determining host range [

22]. This finding was supported by recent studies on leporipoxvirus, capripoxvirus, and orthopoxvirus K3 orthologs. The myxoma virus (MYXV) K3 ortholog M156 specifically inhibited rabbit PKR but failed to inhibit other PKR species [

25]. Similarly, capripoxvirus K3 orthologs inhibited human, goat, and sheep PKR strongly, but only weakly inhibited mouse and cow PKR [

26]. Our studies on inhibition of PKR from a panel of mammalian species by orthopoxvirus K3 orthologs exhibited distinct inhibition profiles. Here, we used a luciferase-based assay and infections of mammalian cell lines to examine the ability of TPV and YMTV K3 orthologs to inhibit PKR derived from 15 primate species. Our results demonstrate that TPV and YMTV K3 orthologs have distinct PKR inhibition profiles and that they inhibit primate PKR in a species-specific manner.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

Tert immortalized gibbon fibroblasts (gibbon Tert-GF), HeLa cells (human, ATCC #CCL-2), HeLa PKR-knock-out (PKR

ko) cells, and BSC-40 cells (ATCC CRL-2761) were kindly provided by Dr. Adam Geballe [

29]. RK13 cells (rabbit) expressing E3 and K3 (designated RK13+E3L+K3L) were previously described [

30]. The cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Life Technologies) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Lonza) or 10% FBS and 100 IU/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). RK13+E3L+K3L cell culture medium contained 500 μg/ml geneticin and 300 μg/ml zeocin (Life Technologies).

2.2. Plasmids

A library of primate PKR expressing plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. Nels Elde [

31]. Primate PKR and viral antagonist genes VACV K3L (YP_232916.1), TPV 012 (EF420156.1), YMTV 012 (AY386371.1) were subcloned into the pSG5 expression vector for luciferase-based reporter assays. pGL3 luciferase reporter vector was purchased from Promega. Cloning was done using Gibson assembly techniques (New England Biolabs) [

32]. To monitor VACV K3L, TPV 012, and YMTV 012 gene expressions, these genes were cloned into C-terminus DYK-tagged pSG5 vector for transient transfection assay. To generate hybrid

NTPV-

CYMTV and

NYMTV-

CTPV K3 orthologs, we PCR amplified

NYMTV 012 (nucleotide 1-99),

CYMTV 012 (nucleotide 100-168),

NTPV 012 (nucleotide 1-99),

CTPV 012 (nucleotide 100-168) and cloned the TPV 012 and YMTV 012 hybrid genes into pSG5 vector using Gibson assembly. To generate recombinant VACV expressing TPV 012 and YMTV 012 genes, the yatapoxvirus K3 ortholog genes were cloned into p837-GOI-mCherry-E3L as previously described [

33].

2.3. Luciferase-Based Reporter Assays

Luciferase-based assays were performed as previously described [

34]. Briefly, 5 x 10

4 HeLa PKR

ko cells were seeded per well in 24-well plates overnight. The HeLa PKR

ko cells were co-transfected with 200 ng of the indicated PKR expression vector, 200 ng of each viral antagonist expression vector, and 50 ng of pGL3 firefly luciferase expression vector (Promega) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were lysed with mammalian lysis buffer (GE Healthcare) at 48 hours post-transfection. Luciferase activity was measured using a GloMax luminometer (Promega) by adding luciferin (Promega) reagent to the cell lysates as per manufacturer’s recommendations. Data are presented as relative luciferase activity in which all data were normalized to pSG5 empty vector. Experiments were conducted in triplicates for each of the three independent experiments.

2.4. Virus and Infections

Vaccinia virus variant vP872 [

35] was kindly provided by Dr. Bertram Jacobs. VC-R4+VACV K3L and VC-R4+sheeppox 011 (SPPV 011), as well as the generation of VC-R4 from vP872 variant were previously described [

26,

33]. Generation of chimeric vaccinia virus, VC-R4+TPV 012, and VC-R4+YMTV 012, was done by the scarless integration of the open reading frames of the yatapoxvirus K3L orthologs into the E3L locus [

33]. The chimeric viruses were plaque-purified two times, and the K3L ortholog gene integrations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The viruses were purified by zonal sucrose gradient centrifugation, and the virus titer was determined on confluent 12-well plates of RK13+E3L+K3L cells. Plaque assays were performed with confluent 6-well plates of the indicated cell lines, which were infected with 50 plaque-forming units (pfu) of each indicated virus. One hour post-infection, the media were replaced with DMEM containing 5% FBS, 1% carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), and 100 U P/S. After 48 hours, cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet, and the excess staining was washed with water. The plates were imaged using an iBright Imaging System (Invitrogen). Virus infection assays were performed in confluent 6-well plates of the indicated cells. The cells were infected with each indicated virus at a MOI of 0.01. Cells and supernatants were collected at 30 hours post-infection and subjected to three rounds of freezing at -80

oC and thawing at 37

oC. Lysates were sonicated twice for 15s, 50% amplitude (Qsonica Q500).

2.5. PCR of Viral Genomic DNA

HeLa PKR

ko cells were seeded in 10 cm dishes to a confluency of 90-100%. The cells were then infected with indicated viruses at a MOI of 0.1 for 24 hours. Viral genomic DNA (gDNA) extraction was done as previously described [

36]. About 100 ng of the isolated viral gDNA was used as a template in a PCR targeting K3L ortholog genes using Phusion High Fidelity DNA polymerase (NEB #M0530L). The forward primer sequence is 5′ GACGAACCACCAGAGGATGATG 3′ and the reverse primer sequence is 5′ AGTACTACAATTTGTATTTTTTAATCTATCTCA 3′. PCR products were gel purified with Monarch DNA Gel Extraction Kit (NEB #T1020) and Sanger sequencing was done to confirm correct integration of the K3L orthologs.

2.6. Immunoblot Analyses

To determine the level of K3 orthologs expression in a transient transfection system, 4x105 HeLa PKRko cells were seeded in a 6-well plate. The next day, the cells were transfected with 1 µg of pSG5 empty vector, DYK tagged VACV K3L, DYK tagged TPV 012, DYK tagged YMTV 012, using Genjet: DNA ratio of 2:1. At 48 hours post-transfection, cells were washed with PBS, lysed with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in DPBS, and sonicated at 50% amplitude for 5 seconds twice. About 10 µg of proteins were run on 12% SDS polyacrylamide gels (Biorad) and transferred to polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF, GE Healthcare) membranes. Membranes were blocked with SuperBlock blocking buffer (Thermofisher) for 1 hour and were probed with primary antibodies against Flag M2 (Sigma F1804) and beta-actin (Sigma A1978) at a dilution of 1:2000 in SuperBlock blocking buffer (Thermofisher) for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing with Tris Buffered Saline 0.1% Tween®️ 20 (TBST, Fisher Bioreagents), membranes were probed with secondary antibody horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.,715-035-150) at a dilution of 1:10000 in 1% (w/v) non-fat milk dissolved in TBST for 1 hour. The membranes were washed three times for 10 minutes, and proteins were detected with Amersham™ ECL™ (GE Healthcare). Images were taken using the iBright Imaging System (Invitrogen).

To determine the level of K3L ortholog expression by the chimeric vaccinia virus, 8x105 HeLa PKRko cells were seeded in a 6-well plate. The next day, the cells were infected with VC-R4, VC-R4+VACV K3L, VC-R4+TPV 012, VC-R4+YMTV 012 at a MOI of 3. Protein lysates were collected at 24 hours post-infection. 12 µg of protein was electrophoresed using 12% SDS polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF, GE Healthcare) membranes. Membranes were probed with primary antibodies beta-actin (Sigma A1978) at dilution 1:2000 in Thermofisher Superblock blocking buffer, primary antibodies against TPV 012 (Genscript) at dilution 1:1000 in 5% milk dissolved in TBST, VACV-K3 at dilution 1:500 in 5% milk dissolved in TBST overnight at 4oC. Anti-TPV 012 (cVQVIRTDKLKGYVDVRHIT) and anti-VACV K3 (cKVIRVDYTKGYIDVNYKRM) were custom produced by peptide-KLH conjugate in New Zealand rabbit (GenScript). After being washed with TBST three times, membranes were probed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (Invitrogen, A16023) at a dilution of 1:10000 in 1% milk for anti-TPV 012 and anti-VACV K3, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., 715-035-150) at 1:10000 dilution in TBST containing 1% (w/v) non-fat milk for beta-actin. The membranes were washed three times for 10 minutes, and proteins were detected with Amersham™ ECL™ (GE Healthcare). Images were taken using the iBright Imaging System (Invitrogen).

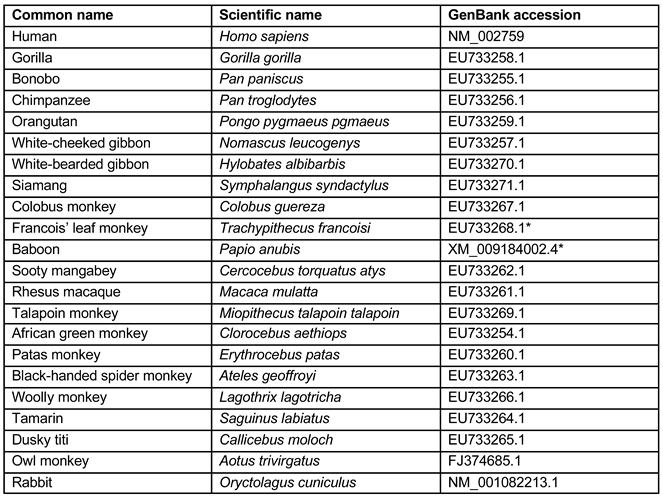

2.7. Phylogenetic Analysis

The amino-acid sequences of PKR from 21 different primate species (

Table 1) were used to generate the phylogenetic tree. The multiple sequence alignment was performed using MUSCLE [

37] and the resulting alignment was used to construct a phylogenetic tree using the maximum likelihood approach, as implemented in the program PhyML 3.0 [

38]. Nodal support of the phylogenetic tree was assessed by bootstrap analysis of 100 replicates. The resulting phylogenetic tree was visualized using FigTree v1.4.4 (available at:

http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

Francois leaf PKR and EU733268.1: all synonymous: T208>C (L70L), C861>T (I287I), G1326>A (G442G), T1446C (H482H).

Baboon PKR and XM_009184002.4: one synonymous A465G (Q155Q) and four non-synonymous G1489A (E497K), A1498C (K500Q), G1511A (G504T) and A1558G (K520E).

3. Results

3.1. Species-Specific Inhibition of Primate PKRs by Yatapoxvirus K3 Orthologs

Inhibition of PKR by K3 orthologs has been shown to be a key determinant for the host range of poxviruses [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

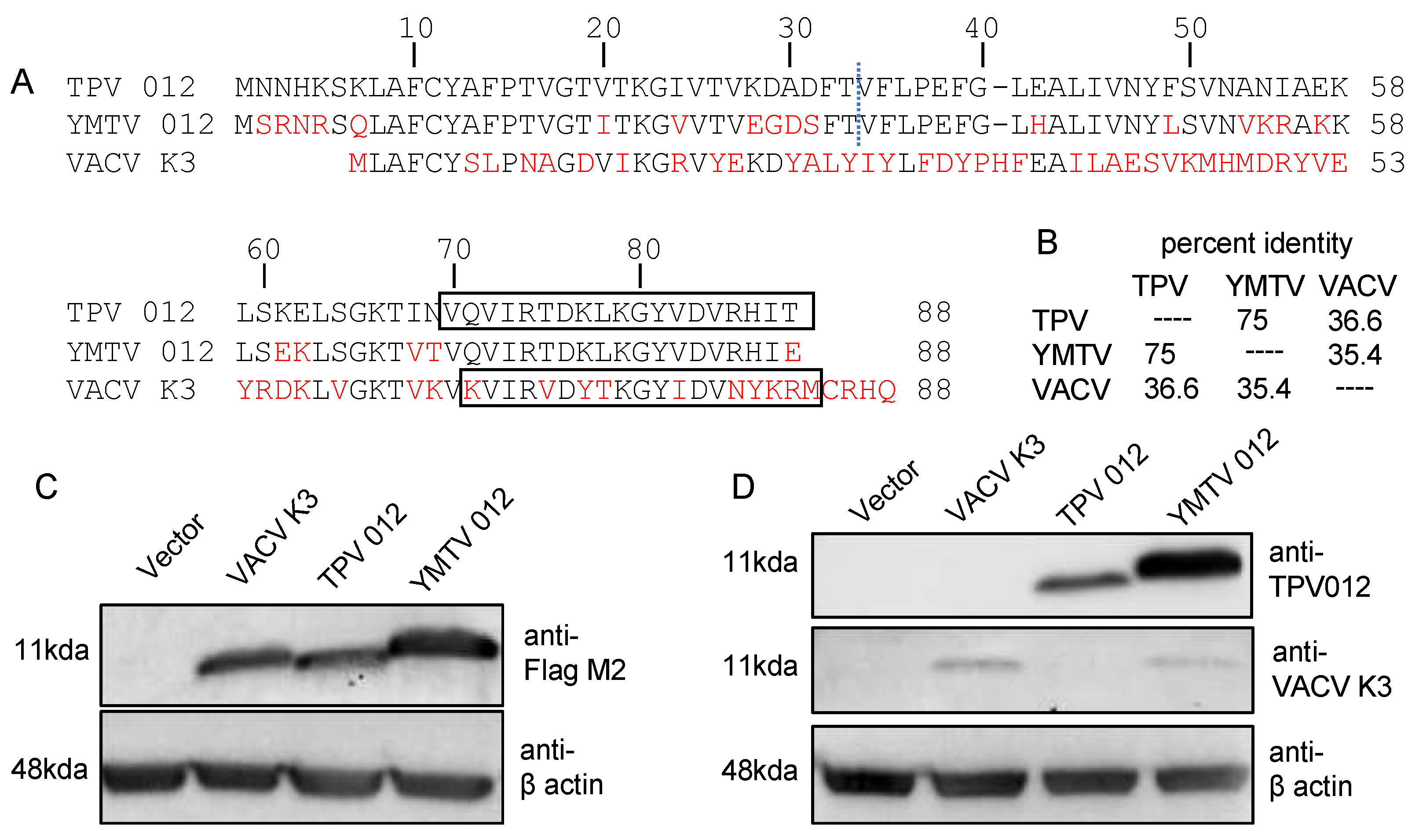

34]. In this study, we examined the role of the K3 orthologs TPV 012 and YMTV 012 in inhibiting PKR derived from a diverse set of primate species. Comparison of the amino acid sequences between TPV, YMTV and VACV K3 orthologs revealed 22 amino acid differences (75% sequence identitiy) between TPV 012 and YMTV 012 and, and about 36% sequence identity between yatapoxvirus and VACV K3 orthologs (

Figure 1A,B). We cloned these three orthologs into the pSG5 expression vector with two C-terminal FLAG tags and transfected them into HeLa PKR

ko cells. Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates showed that vaccinia K3 and TPV 012 were expressed at comparable levels, whereas YMTV 012 was expressed at higher level than the former (

Figure 1C). We also raised polyclonal antibodies against a conserved epitope of TPV 012 (

Figure 1A). Western blots HeLa PKR

ko cell lysates transiently transfected with untagged K3L orthologs showed higher expression of YMTV 012 (

Figure 1D). A previously generated antibody raised against VACV K3 detected both VACV K3 as well as YMTV 012 (

Figure 1D).

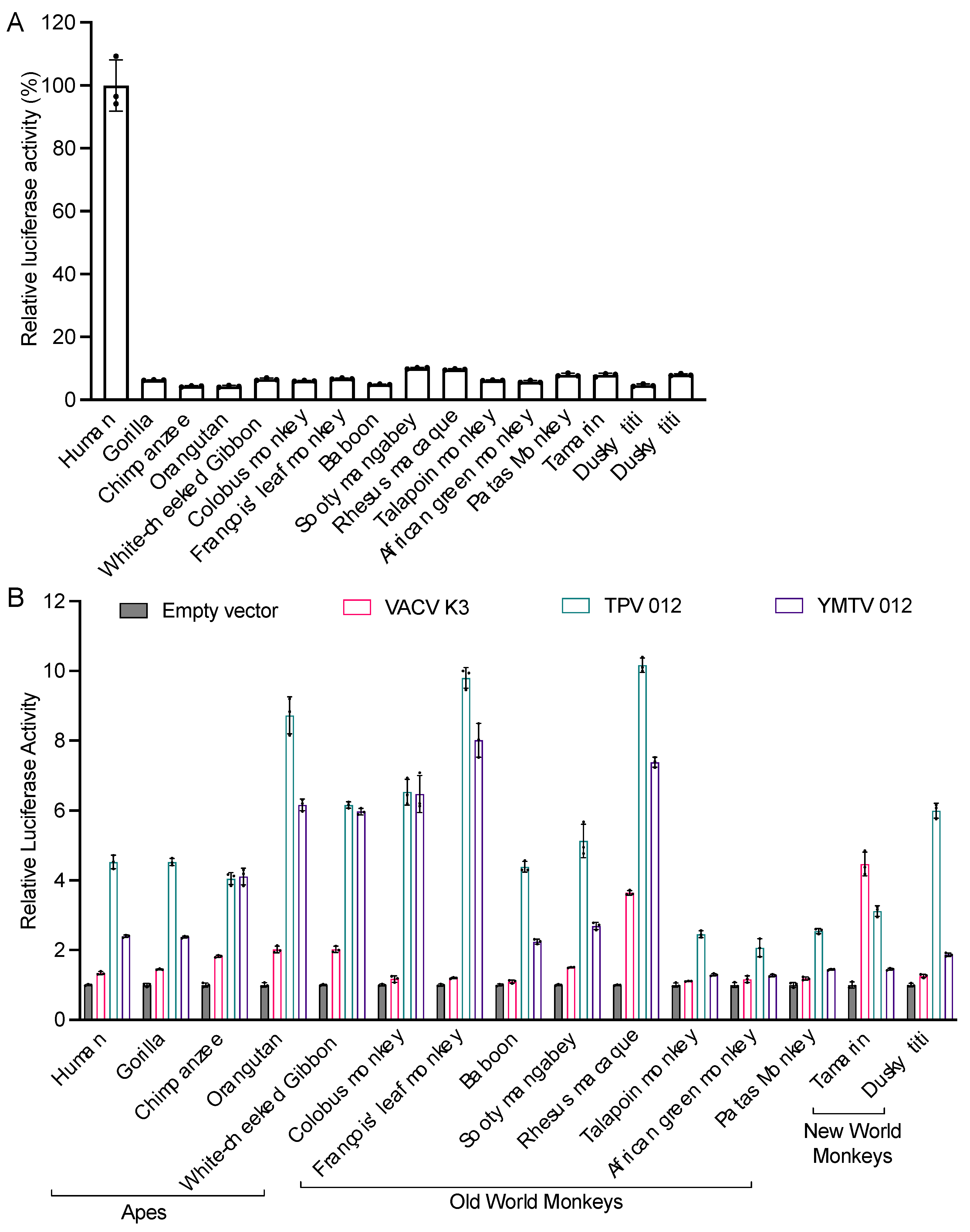

We next tested the sensitivities of 15 different primate species to VACV K3 and the yatapoxvirus K3 orthologs in an established luciferase-based expression assay in which PKR-deficient HeLa cells are co-transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid, PKR and PKR inhibitors [

25,

34]. In this assay, PKR is activated by dsRNA that is formed by overlapping transcripts generated from the transfected plasmids [

39] and suppresses the translation of reporter mRNA, which serves as a proxy to quantify relative translation. Luciferase activity is thus inversely correlated with PKR activity, and inhibition of PKR leads to elevated luciferase activity. We first co-transfected cells with PKRs from 15 primate species representing apes (human, gorilla, chimpanzee, orangutan, white-cheeked gibbon), Old World monkeys (colobus monkey, François leaf monkey, baboon, sooty mangabey, rhesus macaques, talapoin monkey, African green monkey, and patas monkey monkey) and New World monkeys (tamarin and dusky titi), together with the luciferase reporter plasmid to assess PKR activity. All PKRs showed strong and comparable inhibition of luciferase activity (

Figure 2A). We next co-transfected each PKR with either K3 ortholog and the luciferase reporter plasmid (

Figure 2B). Most primate PKRs tested were largely resistant to VACV K3 (less than 2-fold inhibition). Orangutan and white-cheeked gibbon PKR were weakly inhibited (about 2-fold), while rhesus macaque and tamarin PKR were inhibited at intermediate low levels (about 4-fold). 11 of the 15 primate PKRs were inhibited substantially better by TPV 012 than by YMTV 012. PKRs from chimpanzee, white-cheeked gibbon, colobus monkey, and François leaf monkey were inhibited comparably well by TPV 012 and YMTV 012. In addition to different inhibition profiles when comparing TPV 012 with YMTV 012, species-specific differences in PKR susceptibility were observed, with orangutan, François leaf monkey and rhesus macaque PKR being most strongly inhibited, and nine other PKRs being intermediately inhibited by TPV 012. In contrast, nine tested PKRs were only weakly inhibited by YMTV 012.

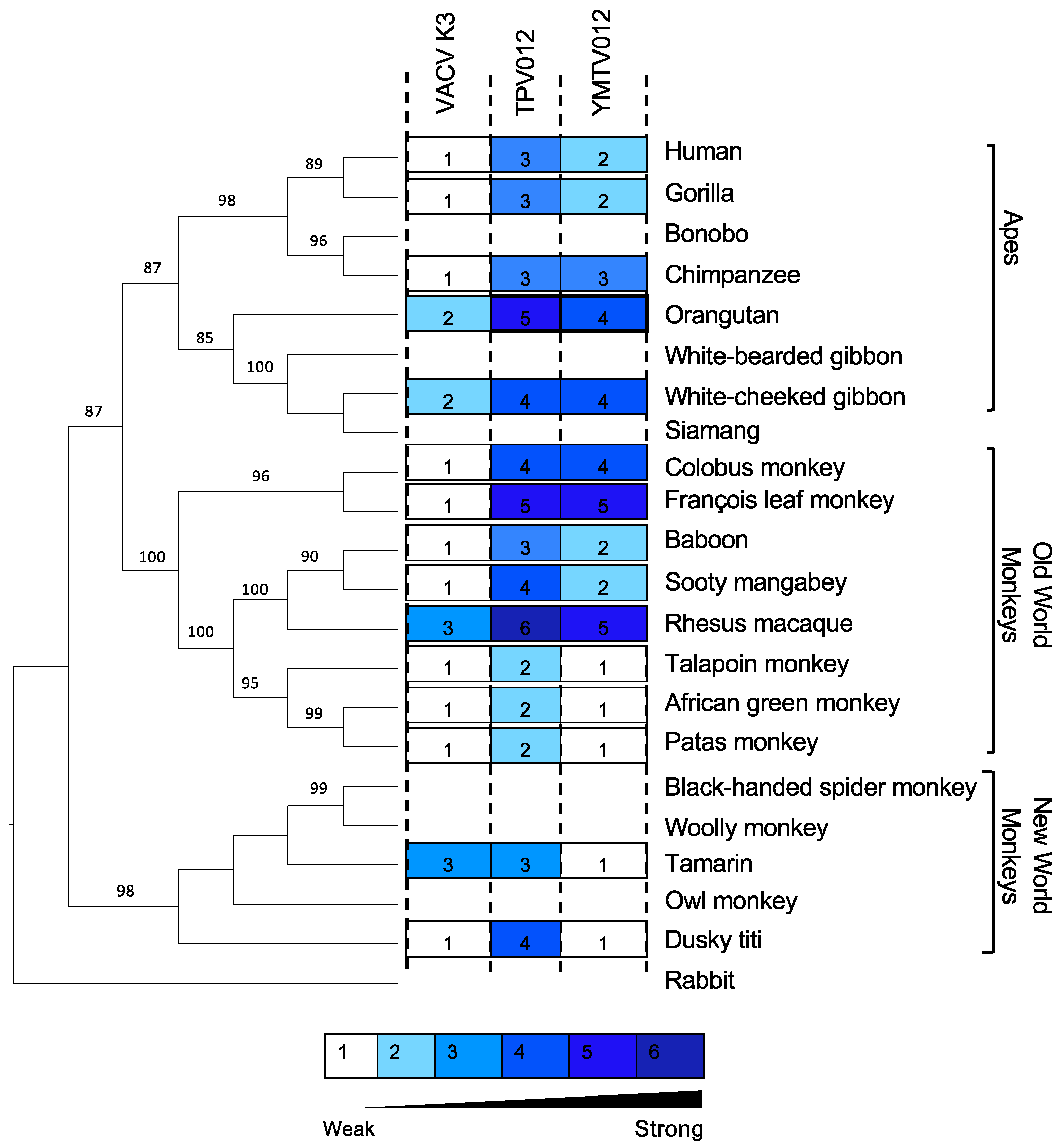

We also projected the relative sensitivities of the tested PKRs to the K3 orthologs on a phylogenetic tree generated with PKR amino acid sequences from a panel of 21 primate species using rabbit PKR as an outgroup to visualize the relatedness among the primate species PKRs (

Figure 3). This tree recapitulates the relatedness of primates PKRs from an earlier study. The closer relatedness of human PKR to gorilla PKR than to chimpanzee PKR, which is different from the generally accepted primate phylogeny, likely as a result of positive selection during PKR evolution [

31]. We used a previously described scale to grade relative PKR inhibition [

28], with 1 for no or very weak inhibition (< 2-fold inhibition), 2 for weak inhibition (2 to 3-fold inhibition), 3 for intermediate low inhibition (3 to 5-fold inhibition), 4 for intermediate high inhibition (5 to 7-fold inhibition), 5 for high inhibition (7 to 10-fold inhibition), and 6 for very high inhibition (> 10-fold inhibition).

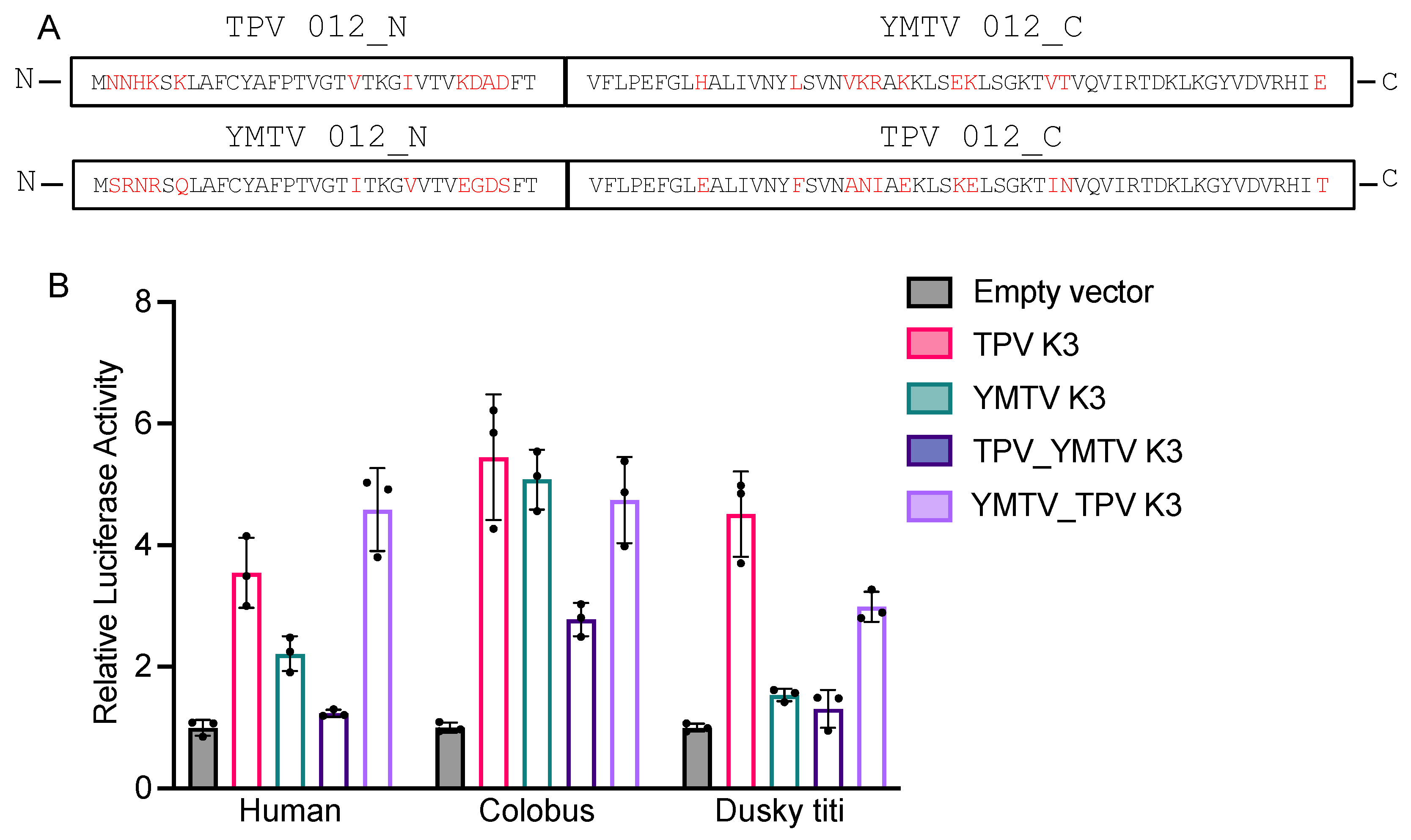

3.2. Differential PKR Inhibition Was Governed by the C-Terminus of Yatapoxvirus K3 Orthologs

The amino acid sequence alignment of YMTV and TPV K3 orthologs identified 22 amino acid differences between the two orthologs, which are distributed throughout the protein sequence. To investigate which regions are important for the differential PKR inhibition by yatapoxvirus K3 orthologs, we generated constructs encoding hybrid YMTV-TPV K3 orthologs in which the C-terminal regions of the two inhibitors were swapped. We took advantage of the shared region in the middle part of the gene (FTVFLPEFG) to separate the N-and C- termini, which leaves 11 amino acids difference in each terminus (

Figure 4A). We analyzed the ability of these hybrid proteins to inhibit human, colobus monkey, and dusky titi PKR using the luciferase assay. The hybrid

NTPV-

CYMTV exhibited inhibition profiles that were more similar to YMTV 012 for each PKR tested (

Figure 4B). Correspondingly, the

NYMTV-

CTPV hybrid showed a similar inhibition pattern to wild-type TPV 012. These results indicate that the C-terminus of TPV 012 and YMTV 012 is important for the observed differential PKR inhibition.

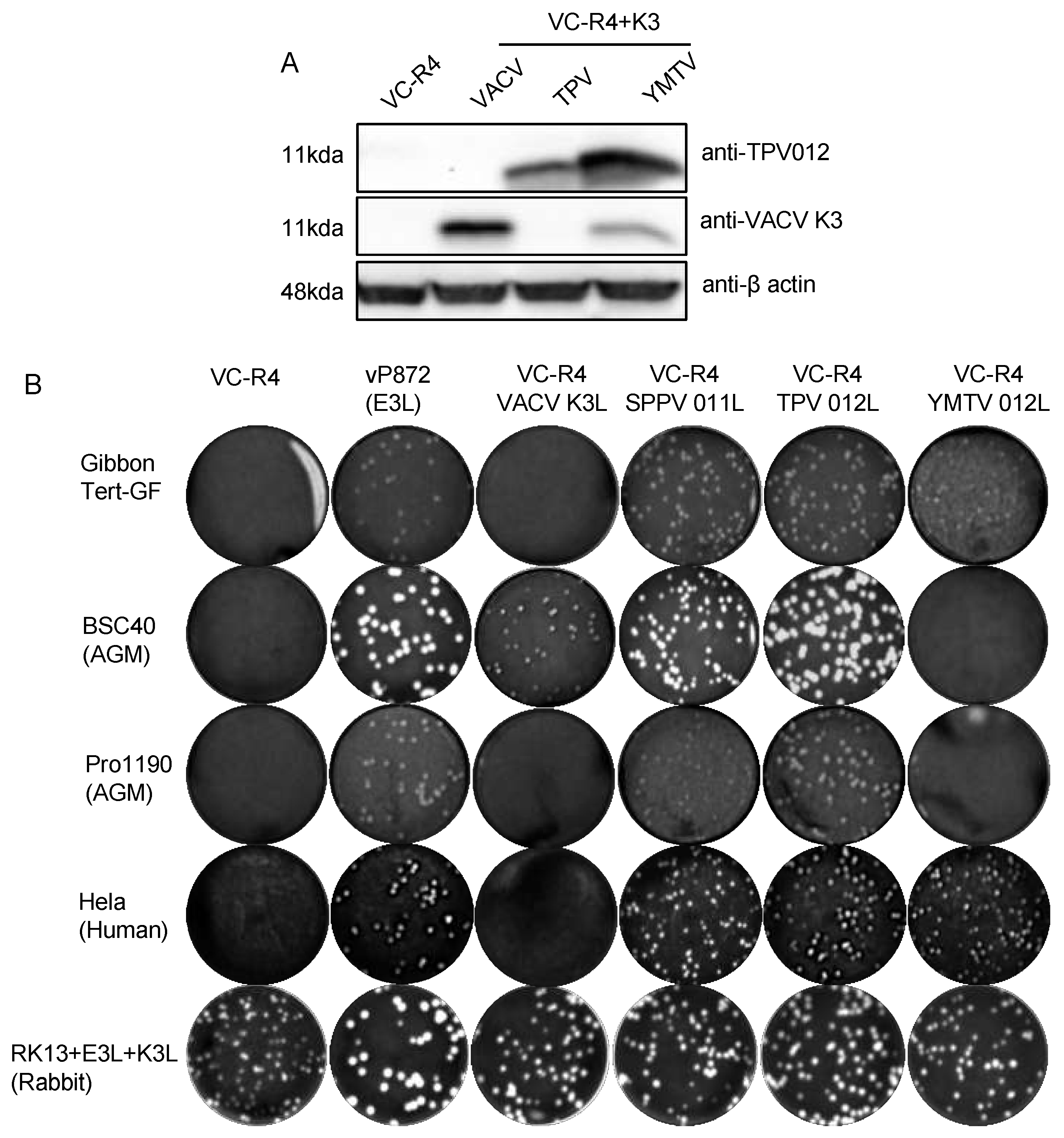

3.3. Chimeric Viruses Expressing TPV 012 or YMTV 012 Displayed Cell Type Specific Differences in Plaque Formation and Virus Replication

Next, we investigated whether the ability of TPV 012 and YMTV 012 orthologs to inhibit primate PKRs correlated with the ability of the viral genes to rescue replication of a VACV strain that lacks PKR inhibitors in primate-derived cell lines. The VACV strain VC-R4 (VACV△E3L△K3L) is a highly attenuated vaccinia virus variant that can only replicate in PKR deficient cell lines or cell lines expressing PKR antagonists [

33]. We inserted either TPV 012 or YMTV 012 into VC-R4 at the E3L locus using the scarless integration method as previously described, designating the chimeric viruses VC-R4-TPV 012 or VC-R4-YMTV 012, respectively [

33]. To analyze expression of the K3 orthologs by these chimeric viruses, we infected HeLa PKR

ko cells and performed western blots using custom-made antibodies at 24 hours post-infection. In agreement with the transfection data (

Figure 1), YMTV 012 was detected at a higher level compared to TPV 012 (

Figure 5A). We next examined plaque formation of these viruses in comparison to VACV vP872 (which lacks K3L but contains the second VACV PKR inhibitor E3), VC-R4+VACV K3L, and VC-R4+SPPV 011 which expresses the sheeppox virus K3 ortholog [

26], in different primate-derived cell lines: HeLa (human), gibbon Tert-GF (gibbon), BSC-40 and PRO1190 (African green monkey). As control, we used RK13+K3L+E3L cells (rabbit), which express VACV E3 and K3 and in which VC-R4 is permissive. We infected these cells with 50 PFU/well. As expected, all viruses formed plaques with comparable sizes in permissive RK13+K3L+E3L cells, VC-R4 only formed plaques in RK13+K3L+E3L cells, and vP872 and VC-R4+SPPV 011 formed plaques in all cells tested (

Figure 5B). VC-R4+VACV K3L developed small plaques only in BSC-40 cells. VC-R4+TPV 012 infection led to the formation of plaques in all tested cells with comparable size to plaques formed by both VC-R4+SPPV 011 and vP872. Relative to VC-R4+TPV 012, VC-R4+YMTV 012 formed smaller plaques in HeLa and gibbon Tert-GF cells and failed to cause plaque formation in both African green monkey cells. In general, based on the plaque assay, TPV 012 rescued VC-R4 replication substantially better than YMTV 012 in primate-derived cell lines, despite the higher expression of YMTV 012.

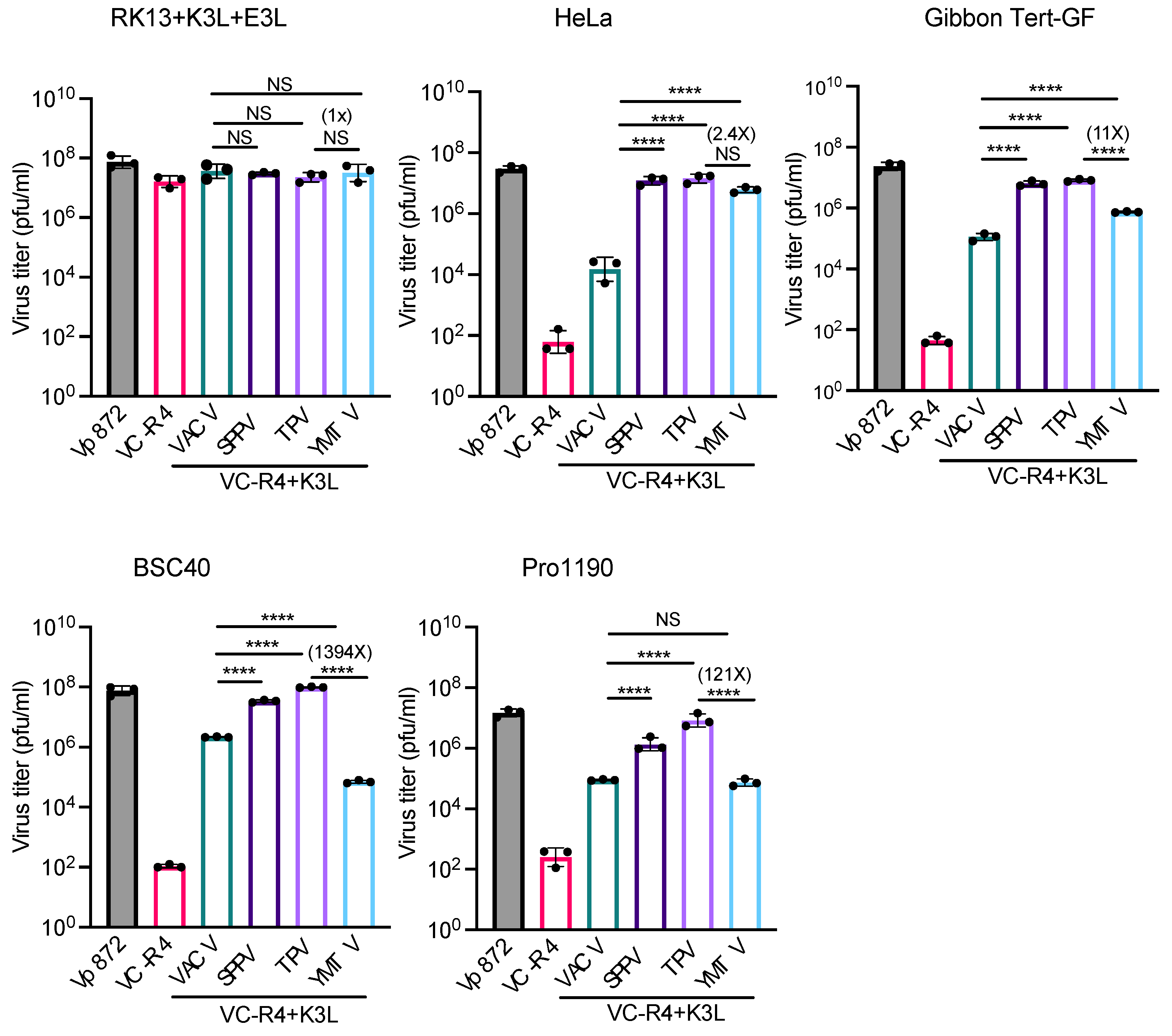

We next measured virus titers to determine the capacity of yatapoxvirus K3 orthologs to restore the replication of VC-R4. We infected RK13+K3L+E3L and primate-derived cell lines HeLa (human), gibbon Tert-GF, BSC-40 (African green monkeys), and PRO1190 (African green monkeys) cells with either VC-R4, vP872, VC-R4+VACV K3L, VC-R4+SPPV 11, VC-R4+TPV 012 and VC-R4+YMTV 012 at a MOI of 0.01. Cell lysates were collected at 30 hours post-infection, and virus titer was determined in RK13+K3L+E3L cells. Consistent with the plaque assays and luciferase assays, all viruses replicated to comparable titers in RK13+K3L+E3L cells (

Figure 6). VC-R4 did not replicate in any cells tested (virus titer below 103 pfu/ml), except in RK13+K3L+E3L cells. VACV K3L rescued VC-R4 virus replication in all cells tested to variable extents, with virus titers about 10-to 100-fold lower than vP872. In HeLa and gibbon Tert-GF cells, SPPV 011 and TPV 012 both restored the replication of VC-R4 to a level comparable to vP872. In BSC-40 and PRO1190 cells, TPV 012 and SPPV 011 rescued VC-R4 replication comparably. Consistent with the plaque assays, VC-R4+YMTV 012 replicated to slightly lower levels than VC-R4+TPV 012 in HeLa cells, although this difference was not significant. In contrast, VC-R4+YMTV 012 significantly replicated with less efficiency than VC-R4+TPV 012 in gibbon Tert-GF cells (11-fold lower), BSC-40 cells (1394-fold lower), and in PRO1190 cells (121-fold lower).

4. Discussion

Vaccinia virus K3 is a poxvirus host range factor that acts by inhibiting the host restriction factor PKR. Homology between the K3 and the S1 domain of eIF2⍺ allows K3 to function as a pseudosubstrate of PKR, competitively inhibiting eIF2⍺ phosphorylation [

19]. This interaction between PKR and K3 has been studied using yeast and mammalian cell assay systems [

40,

41]. Previously, Elde et al. have studied the interaction of 10 primate PKR variants with VACV K3 and showed that PKR from Old World monkeys and New World monkeys were generally susceptible to VACV K3, whereas PKR from hominoids were resistant to VACV K3, indicating species-specific inhibition of primate PKR by VACV K3 [

31]. We recently described that K3 orthologs from myxoma virus, which infects rabbits and hares, and capripoxviruses, which infect sheep, goats and cattle, also inhibit host PKRs in a species-specific manner [

25,

26,

42]. Our recent studies revealed that K3 inhibition could not be predicted by the phylogenetic relatedness of PKR alone [

28]. Therefore, in this study, we experimentally determined whether K3 orthologs of the Yatapoxvirus genus also exhibit host-specific PKR inhibition.

Yatapoxviruses infect primates and can cause zoonotic infections in humans. Here, we analyzed whether TPV and YMTV K3 orthologs inhibit PKR from 15 different primate species in comparison to VACV K3. Our results confirm and extend the results of species-specific VACV K3 inhibition previously reported in both yeast-based [

31] and luciferase-based assays [

28]. White-cheeked gibbon PKR was largely resistant to VACV K3, whereas VACV K3 strongly inhibited tamarin PKR and rhesus macaque PKR. Interestingly, dusky titi PKR, which was previously shown to be susceptible to VACV K3 in the yeast-based assay, appeared to be largely resistant to VACV K3 in our luciferase-based assays. Although the yeast assay can be used to predict the inhibition of PKR by viral antagonists, yeast expression systems have very different post-translational modifications relative to mammalian cells, which might affect protein function [

43]. In general, our data showed that TPV 012 and YMTV 012 exhibited distinct PKR inhibition profiles and that these K3 orthologs inhibited primate PKR in a species-specific manner. All tested primate PKRs were sensitive to TPV 012, although to different degrees. We found a distinct profile of inhibition by YMTV 012 within the Old World monkeys in which talapoin monkey, African green monkey, and patas monkey PKRs were largely resistant to YMTV 012 inhibition. In contrast, rhesus macaque PKR was largely sensitive, supporting that the interaction between K3 orthologs and PKR could only be partially inferred by phylogenetic relatedness. This finding is in line with subcutaneous inoculation studies, showing that YMTV induced tumor formation in rhesus monkeys, whereas no tumors were observed in sooty mangabey, patas monkey, and African green monkeys [

6,

9,

12].

TPV 012 and YMTV 012 differ by 22 amino acids out of 88 residues (

Figure 1). K3 orthologs from the orthopoxvirus genus share a higher sequence identity (80.7-100%) among their members [

28] than TPV 012 and YMTV 012. We found residues within the C-terminus region are important for the differential PKR inhibition by these orthologs. There are two critical conserved motifs in the C-terminus of the K3 orthologs: the PKR recognition motif and helix insert region [

19]. The PKR recognition motif, which includes residues K74, Y76, and D78, provides important determinants for high-affinity binding to PKR [

19]. TPV 012 and YMTV 012 orthologs have identical residues in the PKR recognition motif “KGYVD”, one amino acid difference compared to the PKR recognition motif “KGYID” of VACV K3. The helix insert of eIF2⍺ appears to undergo conformational change upon binding to PKR resulting in the Ser51 site of eIF2⍺ becoming fully accessible to the phosphoacceptor binding site of PKR [

44]. The K3 helix insert region is structurally homologous to the region adjacent to Ser51 in eIF2⍺. The unique conformation of the helix insert region of K3L functions as an inhibitor of PKR activation by preventing PKR trans-autophosphorylation and acting as a pseudosubstrate of PKR [

44]. In addition, we and others have shown that one or more amino acid residues in orthopoxvirus K3 orthologs are responsible for the differential PKR inhibition and that the amino acid variants are predominantly located in the helix insert region [

27,

28].

In this study, the function of yatapoxvirus K3 proteins was further examined in the context of virus infection. The E3L and K3L double knockout vaccinia virus strain VC-R4 (VACV△E3L△K3L) can only replicate in PKR deficient cell lines or cell lines that express PKR antagonists. By inserting K3L orthologs from different poxviruses in the E3L locus of VC-R4, we can analyze the chimeric viruses’ ability to replicate in PKR competent cell lines. The advantage of using the chimeric virus system is that it allows us to assess the ability of K3L orthologs in rescuing the virus in PKR competent cells. As expected, VC-R4 could not replicate in all tested cells, except RK13+E3L+K3L cells. VC-R4 expressing SPPV 011 and TPV 012 replicated as efficiently as vP872 in all tested cell lines as shown in plaque assays and virus titer. In contrast, the VC-R4+VACV K3L and VC-R4+YMTV 012 formed smaller plaques in all tested cell lines, except in RK13+E3L+K3L where these viruses formed comparable plaque size with other viruses. Together these results indicate that the VACV K3L and YMTV 012 are generally weaker inhibitors for the PKR orthologs that we tested. This result was recapitulated in the virus replication assay. There was an 11-fold higher virus titer in VC-R4+TPV 012 infected gibbon Tert-GF cells than in VC-R4+YMTV 012 infected cells. The difference in virus titer was more pronounced in PRO1190 and BSC40 cells, with about 100- to 1000-fold lower virus titer in VC-R4+YMTV 012 infections. While the general patterns observed in the luciferase-based assay were recapitulated in the infection assay, we observed some differences in the magnitude of inhibition.

Overall, the data presented here support previous observations regarding species-specific PKR inhibition by VACV K3 orthologs and extend them to a new genus of poxviruses [

27,

28,

31]. Within primate species PKR, TPV 012 exhibited a broader range of PKR inhibition than did YMTV 012 and VACV K3. VACV K3 appeared to have a narrow range of PKR inhibition within primate species but inhibited efficiently PKR from a wide range mammals PKR [

28]. It is worth mentioning that the ability of a virus to replicate and disseminate efficiently in its host is dependent on the entire interactome between the host and the virus [

45]. In addition to K3L, yatapoxviruses encode several host range genes, including E3L, C7L, M11L, Serpins, P28-like, B5R [

46]. The role of E3L gene of YMTV and C7L of YLDV in host range factors has been previously described [

47,

48]. However, the role of other genes as host range factors needs to be experimentally confirmed.

5. Conclusions

The possible reemergence of smallpox-like diseases through zoonosis of animal poxviruses is a major public health concern. Members of the Yatapoxvirus genus infect humans and other primates and have caused outbreaks throughout Africa for the past 60 years. In addition, human infections with yatapoxviruses have been reported in animal handlers at primate centers in the United States and among travelers who visited Africa. Despite the threat posed to human health, the factors determining the host range of these viruses remain poorly understood. Here, we describe the inhibitory profiles of TPV and YMTV K3 orthologs against primate PKRs, and show that they display virus and host species-specific PKR inhibition. The TPV and YMTV K3 orthologs exhibited distinct PKR inhibition profiles, with TPV 012 generally inhibiting PKRs more strongly than YMTV 012. The species-specific PKR inhibition by the TPV and YMTV K3 orthologs may contribute to the differential susceptibility of primate species to the TPV and YMTV virus infections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M. and S.R..; methodology, D.M., J.N.S, C.P., T.C., L.T., G.B. and S.R..; validation, D.M., J.N.S, C.P., T.C., L.T., G.B. and S.R.; formal analysis, D.M., J.N.S, C.P., T.C., L.T., G.B. and S.R.; resources, S.R.; data curation, D.M., L.T.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.; writing—review and editing, D.M., J.N.S, C.P., L.T., G.B. and S.R..; visualization, D.M., L.T. and S.R.; supervision, S.R.; project administration, S.R.; funding acquisition, S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant R01 AI114851 (to S. R.) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Data Availability Statement

All data necessary for the interpretation of the findings presented in this work are contained within the manuscript figures.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jeffrey Hastings for technical assistance. We thank Drs. Nels Elde, Bertram Jacobs, Charles Samuel, and Adam Geballe for generously providing materials and reagents. Parts of this work were included in the PhD dissertation of D. M.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Haller, S.L.; Peng, C.; McFadden, G.; Rothenburg, S. Poxviruses and the evolution of host range and virulence. Infect Genet Evol 2014, 21, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Essani, K.; Smith, G.L. The genome sequence of Yaba-like disease virus, a yatapoxvirus. Virology 2001, 281, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, C.R.; Amano, H.; Ueda, Y.; Qin, J.; Miyamura, T.; Suzuki, T.; Li, X.; Barrett, J.W.; McFadden, G. Complete genomic sequence and comparative analysis of the tumorigenic poxvirus Yaba monkey tumor virus. J Virol 2003, 77, 13335–13347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downie, A.W.; Taylor-Robinson, C.H.; Caunt, A.E.; Nelson, G.S.; Manson-Bahr, P.E.; Matthews, T.C. Tanapox: a new disease caused by a pox virus. British medical journal 1971, 1, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jezek, Z.; Arita, I.; Szczeniowski, M.; Paluku, K.M.; Ruti, K.; Nakano, J.H. Human tanapox in Zaire: clinical and epidemiological observations on cases confirmed by laboratory studies. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 1985, 63, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bearcroft, W.G.; Jamieson, M.F. An outbreak of subcutaneous tumours in rhesus monkeys. Nature 1958, 182, 195–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, J.C.; Novembre, F.J.; Brown, D.R.; Goldsmith, C.S.; Esposito, J.J. Studies on Tanapox virus. Virology 1989, 172, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarian, S.H.; Barrett, J.W.; Frace, A.M.; Olsen-Rasmussen, M.; Khristova, M.; Shaban, M.; Neering, S.; Li, Y.; Damon, I.K.; Esposito, J.J.; et al. Comparative genetic analysis of genomic DNA sequences of two human isolates of Tanapox virus. Virus Res 2007, 129, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sproul, E.E.; Metzgar, R.S.; Grace, J.T., Jr. The pathogenesis of Yaba virus-induced histiocytomas in primates. Cancer research 1963, 23, 671–675. [Google Scholar]

- Downie, A.W. Serological evidence of infection with Tana and Yaba pox viruses among several species of monkey. The Journal of hygiene 1974, 72, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, B.P.; Nakazawa, Y.J.; Reynolds, M.G.; Carroll, D.S. Estimating the geographic distribution of human Tanapox and potential reservoirs using ecological niche modeling. International journal of health geographics 2014, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrus, J.L.; Strandström, H.V. Susceptibility of Old World monkeys to Yaba virus. Nature 1966, 211, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, J.T., Jr.; Mirand, E.A. Human susceptibility to a simian tumor virus Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1963, 108, 1123-1128. [CrossRef]

- Stich, A.; Meyer, H.; Köhler, B.; Fleischer, K. Tanapox: first report in a European traveller and identification by PCR. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2002, 96, 178–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrov, D.S. Virus entry: molecular mechanisms and biomedical applications. Nature reviews. Microbiology 2004, 2, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, G. Poxvirus tropism. Nature reviews. Microbiology 2005, 3, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, B. Poxvirus cell entry: how many proteins does it take? Viruses 2012, 4, 688–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, B.L.; Langland, J.O. When two strands are better than one: the mediators and modulators of the cellular responses to double-stranded RNA. Virology 1996, 219, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dar, A.C.; Sicheri, F. X-ray crystal structure and functional analysis of vaccinia virus K3L reveals molecular determinants for PKR subversion and substrate recognition. Molecular cell 2002, 10, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomavicius, T.; Guaita, M.; Zhou, Y.; Jennings, M.D.; Latif, Z.; Roseman, A.M.; Pavitt, G.D. The structural basis of translational control by eIF2 phosphorylation. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, P.R.; Zhang, F.; Tan, S.L.; Garcia-Barrio, M.T.; Katze, M.G.; Dever, T.E.; Hinnebusch, A.G. Inhibition of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR by vaccinia virus E3: role of complex formation and the E3 N-terminal domain. Molecular and cellular biology 1998, 18, 7304–7316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langland, J.O.; Jacobs, B.L. The role of the PKR-inhibitory genes, E3L and K3L, in determining vaccinia virus host range. Virology 2002, 299, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langland, J.O.; Jacobs, B.L. Inhibition of PKR by vaccinia virus: role of the N- and C-terminal domains of E3L. Virology 2004, 324, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, S.L.; Park, C.; Bruneau, R.C.; Megawati, D.; Zhang, C.; Vipat, S.; Peng, C.; Senkevich, T.G.; Brennan, G.; Tazi, L.; et al. Molecular basis for the host range function of the poxvirus PKR inhibitor E3. bioRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Haller, S.L.; Rahman, M.M.; McFadden, G.; Rothenburg, S. Myxoma virus M156 is a specific inhibitor of rabbit PKR but contains a loss-of-function mutation in Australian virus isolates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2016, 113, 3855–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Peng, C.; Brennan, G.; Rothenburg, S. Species-specific inhibition of antiviral protein kinase R by capripoxviruses and vaccinia virus. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2019, 1438, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Varga, J.; Deschambault, Y. Poxvirus encoded eIF2α homolog, K3 family proteins, is a key determinant of poxvirus host species specificity. Virology 2020, 541, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Peng, C.; Rahman, M.J.; Haller, S.L.; Tazi, L.; Brennan, G.; Rothenburg, S. Orthopoxvirus K3 orthologs show virus- and host-specific inhibition of the antiviral protein kinase PKR. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17, e1009183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, K.S.; Esparo, N.M.; Child, S.J.; Geballe, A.P. A Single Amino Acid Dictates Protein Kinase R Susceptibility to Unrelated Viral Antagonists. PLoS Pathog 2016, 12, e1005966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Liu, J.; Chan, W.M.; Rothenburg, S.; McFadden, G. Myxoma virus protein M029 is a dual function immunomodulator that inhibits PKR and also conscripts RHA/DHX9 to promote expanded host tropism and viral replication. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9, e1003465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elde, N.C.; Child, S.J.; Geballe, A.P.; Malik, H.S. Protein kinase R reveals an evolutionary model for defeating viral mimicry. Nature 2009, 457, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, D.G.; Young, L.; Chuang, R.Y.; Venter, J.C.; Hutchison, C.A., 3rd; Smith, H.O. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods 2009, 6, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vipat, S.; Brennan, G.; Park, C.; Haller, S.L.; Rothenburg, S. Rapid, Seamless Generation of Recombinant Poxviruses using Host Range and Visual Selection. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE 2020. [CrossRef]

- Rothenburg, S.; Seo, E.J.; Gibbs, J.S.; Dever, T.E.; Dittmar, K. Rapid evolution of protein kinase PKR alters sensitivity to viral inhibitors. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2009, 16, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beattie, E.; Tartaglia, J.; Paoletti, E. Vaccinia virus-encoded eIF-2 alpha homolog abrogates the antiviral effect of interferon. Virology 1991, 183, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, J.; Condit, R.; Obijeski, J. The preparation of orthopoxvirus DNA. Journal of virological methods 1981, 2, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guindon, S.; Dufayard, J.F.; Lefort, V.; Anisimova, M.; Hordijk, W.; Gascuel, O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3. 0. Syst Biol 2010, 59, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejepinska, J.; Malik, R.; Wagner, S.; Svoboda, P. Reporters transiently transfected into mammalian cells are highly sensitive to translational repression induced by dsRNA expression. PLoS One 2014, 9, e87517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawagishi-Kobayashi, M.; Silverman, J.B.; Ung, T.L.; Dever, T.E. Regulation of the protein kinase PKR by the vaccinia virus pseudosubstrate inhibitor K3L is dependent on residues conserved between the K3L protein and the PKR substrate eIF2alpha. Molecular and cellular biology 1997, 17, 4146–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.V.; Chang, H.W.; Jacobs, B.L.; Kaufman, R.J. The E3L and K3L vaccinia virus gene products stimulate translation through inhibition of the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase by different mechanisms. J Virol 1993, 67, 1688–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Peng, C.; Zhang, C.; Stoian, A.M.M.; Tazi, L.; Brennan, G.; Rothenburg, S. Maladaptation after a virus host switch leads to increased activation of the pro-inflammatory NF-κB pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2022, 119, e2115354119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira Gomes, A.M.; Souza Carmo, T.; Silva Carvalho, L.; Mendonça Bahia, F.; Parachin, N.S. Comparison of Yeasts as Hosts for Recombinant Protein Production. Microorganisms 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, A.C.; Dever, T.E.; Sicheri, F. Higher-order substrate recognition of eIF2alpha by the RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR. Cell 2005, 122, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenburg, S.; Brennan, G. Species-Specific Host-Virus Interactions: Implications for Viral Host Range and Virulence. Trends in microbiology 2020, 28, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratke, K.A.; McLysaght, A.; Rothenburg, S. A survey of host range genes in poxvirus genomes. Infect Genet Evol 2013, 14, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myskiw, C.; Arsenio, J.; Hammett, C.; van Bruggen, R.; Deschambault, Y.; Beausoleil, N.; Babiuk, S.; Cao, J. Comparative analysis of poxvirus orthologues of the vaccinia virus E3 protein: modulation of protein kinase R activity, cytokine responses, and virus pathogenicity. J Virol 2011, 85, 12280–12291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Chao, J.; Xiang, Y. Identification from diverse mammalian poxviruses of host-range regulatory genes functioning equivalently to vaccinia virus C7L. Virology 2008, 372, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, F.; Higgins, D.G. Clustal Omega for making accurate alignments of many protein sequences. Protein Sci 2018, 27, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).