1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a public health concern, especially in developing nations. By 2021, an estimated 10.6 million people globally contracted TB, with 1.6 million deaths reported that year[

1,

2]. High-burden countries (HBCs), as defined by the WHO (≥20 cases per 100,000), include nations in Africa, Latin America, and Asia, which are experiencing a steady increase in new TB cases[

1,

3]. Mexico is considered an endemic country for latent TB infection (LTBI), with an incidence rate of 28 cases per 100,000 population annually[

4].

TB infection is increasingly recognized as a spectrum, reflecting a range of states influenced by bacterial load, host immune response, environmental factors, and genetic predisposition[

5,

6]. At one end of the spectrum is LTBI, where the bacteria are present but inactive, with no clinical symptoms, yet there is a risk of progressing to active disease. Moving along the spectrum, intermediate states may exist where the bacteria begin to replicate, but the host’s immune system still manages to contain the infection, leading to subclinical or incipient TB. At the other end is active TB infection (ATBI), a condition characterized by symptomatic disease, which can involve multiple organs and may result from primary infection or reactivation of latent TB[

7,

8].

Vulnerable populations for TB infection include patients with certain comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, silicosis, end-stage renal disease, recent TB infection, treatment with glucocorticoids or biological agents, malnutrition, HIV infection, and those in immunocompromised states, including recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT)[

9].

The cumulative lifetime risk of LTBI reactivation to active disease is estimated to be around 5 to 10%[

10]. However, in HSCT recipients, this risk can increase from 3 to 10 times compared to healthy controls, with a mortality rate ranging from 0 to 50%. Importantly, the lungs are the most frequently involved organ in these cases[

11,

12]. According to the European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL), the rate of ATBI in HSCT is estimated to be 2.7% (ranging from 1.5% to 16.0%) in regions with high tuberculosis incidence (≥100 cases per 100,000 population); 2.2% (ranging from 0.2% to 8.5%) in regions with intermediate TB incidence; and 0.7% (ranging from 0.4% to 2.3%) in low incidence regions (<20 cases per 100,000 population)[

13]. Of note, data from the ECIL shows that only 36% facilities had a formal LTBI screening prior to HSCT.

The WHO TB preventive therapy (TPT) guidelines aim to prioritize treatment for the highest risk groups of developing active TB. TPT should also be considered in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy or undergoing organ transplantation or HSCT, migrants from countries with high TB burden, people with silicosis, health workers, homeless persons, prisoners, and illicit-drug users[

14].

However, the efficacy of TPT is variable, and in the context of HSCT, with few studies showing a benefit, mainly with isoniazid (INH) treatment[

15,

16]

.

Since no guideline exists for diagnosing or treating LTBI in the HSCT population, we explored the efficacy of a preemptive strategy consisting of either a tuberculin skin test (TST) or QuantiFERON-TB Gold (QFT), along with a pulmonary CT scan, followed by INH therapy for positive cases.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective study involving consecutive adult patients who underwent either allo-HSCT or autologous HSCT (auto-HSCT) and their donors at our institution from January 2005 to December 2022. Our main objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of a preemptive approach using INH therapy for LTBI in reducing the rates of TB reactivation to ATBI among HSCT recipients.

We collected comprehensive clinical, microbiological, and outcomes data from electronic medical records, including baseline disease characteristics, type of HSCT, TB screening strategy, INH treatment, and HSCT outcomes. Cases were categorized by HSCT type into auto-HSCT and allo-HSCT groups. Patients with incomplete records or less than 6 months of follow-up post-HSCT were excluded from the analysis.

The study was conducted at the National Cancer Institute (INCan), a tertiary care referral oncologic center in Mexico City. INCan features a specialized HSCT program, performing approximately 50 transplants per year. Most patients treated in this unit have hematologic malignancies rather than bone marrow failure or other hematologic conditions.

Per our institutional protocol, all patients underwent pre-HSCT evaluation with either TST or QFT assay and a pulmonary CT scan. Donors also underwent TST or QFT testing. Negative TST cases were retested at least 2 weeks after the initial test. HSCT recipients and donors who tested positive without clinical manifestations or radiological evidence of the disease received INH treatment for a minimum of 2 months before HSC mobilization and collection, aiming to complete a total of 6 to 9 months at a dose of 5 mg/kg, with a maximum daily dose of 300 mg, following CDC/ATS/IDSA guidelines[

17,

18].

Statistical analysis involved comparing categorical variables using Fisher’s exact test and employing unpaired t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables. In contrast, Mann-Whitney tests were used for non-normally distributed continuous variables. The effectiveness of the preemptive strategy was assessed by determining the rate of TB reactivation, which is defined as the development of ATBI in patients with previous LTBI. Categorical variables are described using frequency and percentages, while quantitative data are presented as median and range.

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.5.2) and RStudio (version 2023.12.1+402), with statistical significance set at a p-value of less than 0.05.

Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee, the study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Of 412 medical records reviewed, 338 (82.0%) patients met inclusion criteria. Seventy-three patients did not undergo tuberculosis screening tests, and one patient had active tuberculosis before HSCT. The median age at diagnosis was 36 years (range 12-67), with a median age of 40 (range 18-69) at HSCT. The cohort consisted of 195 (57.7%) males and 143 (42.3%) females, with all patients being Mexican mestizos (

Table 1).

By diagnosis, the distribution was as follows: 53 patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), 36 with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), 15 with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), 88 with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), 54 with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), 73 with multiple myeloma (MM), 5 with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), 5 with solid neoplasms, 4 with aplastic anemia (AA), 3 with dendritic-cell neoplasms, 1 with myelofibrosis, and 1 with Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM).

3.2. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Characteristics

Among the 338 patients, the median number of previous lines of therapy before undergoing HSCT was 2 lines (range 1 to 4). Of these patients, 210 (50.9%) underwent auto-HSCT, while 128 (31.1%) underwent allo-HSCT. Within the allogeneic group, 99 (77.3%) had a matched related donor (MRD) transplant, and 29 (22.7%) had a mismatched related donor (MMRD) transplant. Among those receiving allo-HSCT, 106 (82.8%) received myeloablative conditioning, while 22 (17.2%) received reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC).

3.3. Latent Tuberculosis Protocol and TB Reactivation

The LTBI protocol for patients included chest imaging in all cases, with 325 patients (96.2%) having TST and 13 (3.8%) QFT. The initial TST was positive in only 10 transplant recipients, necessitating retesting for the remaining 294 patients. Of these, 81-second TSTs turned positive. Only one patient with a QFT was diagnosed with LTBI. HSCT donors all had TST and chest imaging.

Overall, LTBI was diagnosed in 92 (27%) of HSCT recipients, with 24 showing abnormal chest imaging results and 9 having a history of community bacillus exposure. Abnormal chest imaging included 6 patients with multiple pulmonary nodules due to possible IFI, 4 patients with calcified granulomas, 3 patients with calcified nodules, 3 patients with nodules classified as secondary to HL (1 with progressive disease), two patients with pulmonary fibrosis, two patients with nodules due to involvement by systemic NHL, and one patient each with ground glass opacities due to COVID-19, nodules with S. aureus pneumonia, a granuloma and nodules due to histoplasmosis.

Among the 128 allo-HSCT, 19 donors (14.8%) tested positive, and only one had abnormal chest imaging due to history of TB, with calcified nodules. Additionally, eight allo-HSCT patients had LTBI in both the donor and recipient. There were no significant differences in the age at transplant between LTBI-positive and LTBI-negative recipients (mean 41.4 vs. 40.1 years, p=0.430). However, there was a significant female predominance among LTBI-positive cases (54.4% vs. 37.8%, p=0.0067).

Eighty-six HSCT recipients started INH for LTBI treatment. Most patients, 81 out of 86, completed INH treatment;—a small number of 5 patients discontinued therapy due to hepatotoxicity. There was no reactivation of TB in the 4 non-treated patients. The last two patients were lost to follow-up.

Two cases of ATBI were documented. The first case involved an auto-HSCT recipient, with NHL and type 2 diabetes, who had a TST of 15mm pre-HSCT. Active TB was ruled out based on symptoms. However, LTBI was diagnosed, and the patient had been receiving INH for 4 months. During the transplant nadir, she developed cough and pulmonary infiltrates, visible on chest radiography. A positive Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) bacilloscopy tested positive for TB. She subsequently completed a six-month course of antituberculous treatment.

The second case was another auto-HSCT recipient who was HIV-positive and developed tuberculous lymphadenitis two months post-transplant. This patient had a negative TST before HSCT and a CD4 count of less than 200 cells/mm3. He developed cervical lymphadenopathy, and the diagnosis was confirmed through histopathology, which reported granulomatous lymphadenitis. TB PCR, ZN staining and culture results were all negative. He received 7 months of anti-TB treatment, with clinical improvement. Overall, the cumulative incidence of ATBI was 0.6% (2/338). In patients with LTBI who received INH, the reactivation rate was 1.2% (1/86).

3.4. Survival Analysis and Follow-Up/Relapse

Overall, the median follow-up duration from HSCT to the last follow-up was 39 months (range 1-164), during which 93 deaths were registered, resulting in a mortality rate of 27.5%. The primary causes of death included relapse, the most prevalent at 50 (53.8%) cases, followed by infection with 30 (32.3%) patients. Additionally, graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) accounted for 7 (7.5%) cases, while veno-occlusive disease, graft failure, hepatic failure, and hemorrhage accounted for one case each. There were 2 patients for whom the cause of death was not reported.

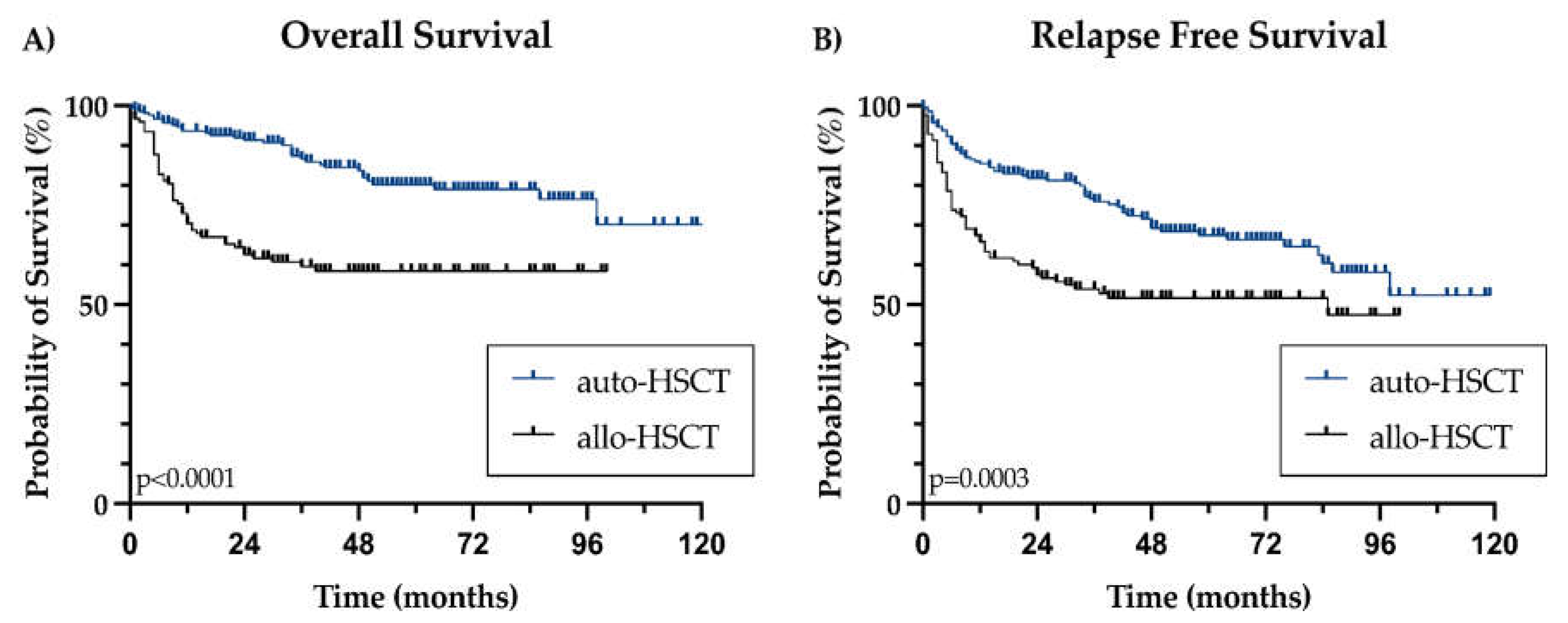

OS was not reached for the entire cohort or when stratified by transplant type. The 2-year OS rates were 91.4% for patients who underwent auto-HSCT and 62.6% for those who underwent allo-HSCT, a difference that reached statistical significance (p<0.0001) (

Figure 1A). LTBI was not associated with a worse OS (HR 1.124, 95%CI 0.688-1.836, p=0.640)

We recorded 89 relapses, with a median post-transplant relapse-free survival (RFS) not reached. The 2-year RFS was 79.3% overall, 83.7% for patients undergoing auto-HSCT, and 71.9% for the allo-HSCT subgroup, with a significant difference by type of transplant (p=0.0003) (

Figure 1B). LTBI did not correlate with a poorer RFS (HR 1.076, 95% CI 0.713-1.625, p=0.726), with a total of 21/92 (22.8%) patients relapsed in the LTBI group, and 68/246 (27.6%) in non-LTBI patients.

4. Discussion

Our analysis identified a total of 39 (30.5%) allo-HSCT recipients, 53 (25.2%) auto-HSCT recipients, and 19 (14.8%) donors with LTBI, showing the highest prevalence among allo-HSCT recipients. This higher prevalence, despite the fewer number of allo-HSCT transplants, could be attributed to baseline hematologic diagnosis, such as acute leukemia, as well as baseline immune status. The LTBI prevalence in healthy donors usually mirrors the prevalence in the general population. In Mexico, LTBI prevalence is highly variable, and has been reported up to 50% in some groups and regions. The donor prevalence in our study reflects a mixed population from both intermediate and high-burden regions in the country.

Despite being a region with areas highly endemic for TB, information on HSCT recipients is scarce in Latin America (LATAM). In our cohort of HSCT recipients, we report a prevalence of LTBI of 27%, which is similar to another recently reported cohort in Mexico. Bourlon et al. documented their experience using TST for LTBI screening followed by INH prophylaxis in 284 Mexican HSCT recipients, finding a prevalence of 20% and zero documented reactivations[

20]. In Brazil, the prevalence of LTBI in HSCT recipients ranged from 8.7% to 17.1%, with no TB reactivations observed when INH-based strategies were employed (

Table 2)[

21,

22]. No additional reports from other LATAM countries were found, evidencing a significant gap in the literature. Our findings contribute to the limited information available on this topic in LATAM, a region where the TB burden remains high.

Although the rate of LTBI in HSCT donors generally reflects the local epidemiology[

23,

24], this relationship is not always consistent for HSCT recipients, as other factors can contribute to significant variability. For instance, as shown in

Table 2, countries not classified as HBC exhibit a variable LTBI prevalence in this high-risk population, ranging from 0% to 31.6%. In contrast, for HBC, the LTBI prevalence in HSCT recipients ranges from 8.7% to 41.2%. This discrepancy hints the influence of additional factors beyond regional TB prevalence, such as differences in healthcare practices, screening protocols, and the underlying immune status of transplant recipients[

25]. Additionally, patients with a history of pretransplant ATBI and extensive GvHD are at a higher risk of reactivating TB post-transplant, as exemplified in the series by Agrawal et al. and Zeng et al[

26,

27].

In our cohort, 2 patients developed ATBI after HSCT. This rate is similar to what is reported in the literature for HBC, with the incidence of ATBI varying significantly across different transplant centers, ranging from 0.4% to 2.7%, while it is estimated in 2.7% (ranging from 1.5% to 16%) in high-burden regions[

28,

29,

30]. Focusing in allo-HSCT recipients, this is markedly higher, with studies reporting a standardized incidence ratio of up to 9.1% and relative risks ranging from 2.95 to 13.1 times higher[

28,

31]. In contrast, the use of INH prophylaxis effectively prevented ATBI in allo-HSCT recipients.

Notably, one of the auto-HSCT recipients who experienced TB reactivation shortly after HSCT was under INH prophylaxis. This suggests that, while INH preemptive treatment is generally effective, it may not completely eliminate the risk of TB reactivation, particularly in highly immunocompromised patients. Factors such as a high level of immunosuppression or potential drug resistance and drug-drug interactions may contribute to early TB reactivation in these patients[

32].

Regarding the safety of INH therapy, despite a high rate of successful treatment completion in LTBI patients, hepatotoxicity posed a challenge, leading to therapy discontinuation in 5.4%, when used as monotherapy for LTBI, hepatic injury rates ranging from 0.15% to 2%[

33]. Prophylactic treatment with INH potentially diminishes TB reactivation,

Table 2 [

23].

The WHO TB guidelines emphasize the importance of completing treatment ideally before the transplantation procedure, recommending faster and shorter regimens such as 1HP (one month of daily Rifampicin (RMP) plus INH) or 3HP (three months of weekly RMP plus INH) for better adherence and fewer interactions with immunosuppressants, like corticosteroids and tacrolimus[

34]. However, shortages and resistance to RMP pose challenges to its use in LATAM and worldwide[

35,

36,

37], and the risk of drug interactions remains high[

38]. As an alternative, a limited number of studies have shown that, in patients with LTBI who did not receive INH as preemptive therapy prior to HSCT, adding INH after HSCT can still be effective in preventing the reactivation of TB[

39].

Aside from HSCT recipients, patients who receive T-cell modifying therapies such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T-cells, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) or bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs) could be at high risk for ATBI due to prior immunosuppression and lymphodepletion. These treatments contribute to persistent hypogammaglobulinemia and prolonged cytopenia, therefore potentially requiring ongoing monitoring and management[

40,

41].

Moreover, patients receiving CAR-T cell therapy can be at an increased risk for ATBI, as the use of tocilizumab, an anti-interleukin-6 antibody, is associated with a further increase in TB reactivation risk[

40,

42]. Although reports on TB reactivation are limited for these therapies, a study by Zhang et al. demonstrated a comparable risk to patients undergoing HSCT[

43], while two reports exist on ICI, with an LTBI prevalence of 13.0% and a reactivation rate of 0.1% in low-burden TB areas (

Table 2)[

44,

45].

In this context, preemptive anti-TB treatment is recommended to mitigate the risk of reactivation during immunosuppression. This approach ensures early detection and prompt treatment of TB reactivation, thus improving patient outcomes[

46,

47].

Akin other studies, the 2-year overall survival rates between auto-HSCT (91.4%) and allo-HSCT (62.6%) recipients were not impacted by LTBI. Importantly, none of the 93 reported deaths was attributed to ATBI. Taken together, this data underscores the need for vigilant monitoring and prompt management in this high-risk population[

28,

48].

The study had several advantages, including the relatively large number of both auto- and allo-HSCT patients from a region with few reports in this setting. It covered a wide range of hematological neoplasms in an area with a high burden of TB, had a long follow-up period (median of 39 months), and showed good tolerability for the INH preemptive therapy. However, the study also had some limitations, including its retrospective nature, incomplete data for 74 patients, especially in earlier years, which could have skewed the results. Additionally, there was variability in follow-up duration and in the utilization of screening strategies with both TST and QFT being used.

Table 2.

Reported studies and strategies of LTBI and ATBI in cell-therapy and T-cell directed therapy recipients.

Table 2.

Reported studies and strategies of LTBI and ATBI in cell-therapy and T-cell directed therapy recipients.

| Study |

Year |

Country |

High Burden Country#

|

Therapy (n) |

LTBI prevalence in the study (%) |

Pre-emptive strategy |

TB re-activation (%) |

| Current study |

2024 |

Mexico |

Yes |

auto-HSCT (n=210), allo-HSCT (n=128) |

25.2

D14.8/R30.5 |

INH |

1.2 |

| Hyun et al.[25] |

2024 |

South Korea |

Yes |

auto-HSCT (n=9275), allo-HSCT (n=11202) |

N.A. |

None |

0.9

1.7 |

| Castro-Lima et al.[21] |

2023 |

Brazil |

Yes |

auto-HSCT (n=153), allo-HSCT (n=38) |

17.1 |

INH |

0 |

| Zhang et al.[43] |

2023 |

China |

Yes |

CD-19/CD-22 CAR-T (n=427) |

N.A. |

None |

1.2 |

| Mert et al.[23] |

2022 |

Turkey |

No |

auto-HSCT (n=227), allo-HSCT (n=134) |

18.2

21.6 |

INH |

0 |

| Compagno et al.[49] |

2022 |

Italy |

No |

auto-HSCT (n=51), allo-HSCT (n=209) |

13.7

6.7 |

INH |

0 |

| Bello et al.[50] |

2022 |

Philippines |

Yes |

auto-HSCT (n=31), allo-HSCT (n=2) |

33.3 |

None |

0 |

| de Oliveira-Rodrigues et al.[22] |

2021 |

Brazil |

Yes |

allo-HSCT (n=126) |

8.7 |

INH |

0 |

| Anand et al.[44] |

2020 |

USA |

No |

anti-PD-1/PD-L1 ICI (n=62823)∞

|

N.A. |

None |

0.1 |

| Langan et al.[45] |

2020 |

Germany |

No |

anti-PD-1/PD-L1 ICI (n=70) |

13.0 |

INH ± RMP |

0 |

| Park et al.[15] |

2020 |

South Korea |

Yes |

allo-HSCT (n=1162) |

16.0 |

INH

None |

0

4.6 |

| Zeng et al.[27] |

2020 |

China |

Yes |

allo-HSCT (n=6236) |

N.A. |

INH¢

|

0.5 |

| Bourlon et al.[20] |

2020 |

Mexico |

Yes |

auto-HSCT (n=165), allo-HSCT (n=125) |

20.0

D41.2/R20.0 |

INH |

0 |

| Sosa-Moreno et al.[51] |

2020 |

USA |

No |

auto-HSCT (n=217), allo-HSCT (n=240) |

5.5

1.7 |

INH |

0 |

| Cheng et al.[39] |

2019 |

USA |

No |

auto-HSCT (n=1252), allo-HSCT (n=1279) |

1.2 |

INH |

0 |

| Aki et al.[30] |

2018 |

Turkey |

No |

auto-HSCT (n=287), allo-HSCT (n=271) |

31.6 |

INH

None |

0

0. 2 |

| Agrawal et al.[26] |

2017 |

India |

Yes |

allo-HSCT (n=175) |

N.A. |

None |

2.8 |

| Lee et al.[28] |

2017 |

South Korea |

Yes |

allo-HSCT (n=845) |

28.1 |

INH,

None |

2.1

5.7 |

| Fan et al.[52] |

2015 |

Taiwan |

No |

auto-HSCT (n=672), allo-HSCT (n=1368) |

N.A. |

None |

1.0

2.3 |

| Sester et al.[53] |

2014 |

Europe |

No |

Unspecified (n=103) |

0-5.8 |

N.A. |

0 |

| Moon et al.[54] |

2013 |

South Korea |

Yes |

auto-HSCT (n=100), allo-HSCT (n=114) |

26.0 |

None |

0.8 |

5. Conclusions

The implementation of an LTBI protocol involving screening with TST and QFT resulted in the diagnosis of LTBI in 27% of HSCT recipients and 14.8% of donors. The overall incidence of active TB infection and reactivation was low, with no deaths attributed to TB. Effective and complete antiTB therapy based on INH was associated with no subsequent reactivation during the follow-up period, highlighting the effectiveness of the LTBI protocol.

These findings emphasize the importance of stringent LTBI protocols in endemic countries to mitigate the risks associated with tuberculosis in HSCT, especially allo-HSCT recipients. Further studies are needed to explore the utility of such protocols for other modalities of cell and immune-based therapies beyond HSCT.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Pellon-Téllez K, Valero-Saldaña L and Acosta-Maldonado BL; methodology, Pellon-Téllez K, Fernandez-Vargas OE, Cornejo-Juárez P, Rubalcava-Lara LF and Acosta-Maldonado BL; validation, Cornejo-Juárez P, Martin-Onraet A, Valero-Saldaña L and Acosta-Maldonado BL; formal analysis, Pellon-Téllez K, Fernandez-Vargas OE and Rubalcava-Lara LF; investigation, Pellon-Téllez K, Rubalcava-Lara LF, Alvidrez-González RA and Bonilla-Salcedo AY; data curation, Pellon-Téllez K, Fernandez-Vargas OE, Martin-Onraet A and Rubalcava-Lara LF; writing—original draft preparation, Pellon-Téllez K, Fernandez-Vargas OE, Cornejo-Juárez P, Martin-Onraet A, Rubalcava-Lara LF, Alvidrez-González RA and Bonilla-Salcedo AY; writing—review and editing, Pellon-Téllez K, Fernandez-Vargas OE, Cornejo-Juárez P, Martin-Onraet A, Rubalcava-Lara LF and Acosta-Maldonado BL; visualization, Pellon-Téllez K, Fernandez-Vargas OE and Martin-Onraet A; supervision, Patricia Cornejo-Juárez, Valero-Saldaña L and Acosta-Maldonado BL; project administration, Pellon-Téllez .All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (protocol code No. 2021/121).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study and the utilization of anonymized clinical data.

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate public archived datasets. However, upon request, the corresponding author can provide access to the anonymized data utilized in the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bagcchi, S. WHO’s Global Tuberculosis Report 2022. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Report 2023. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. ISBN: 978-92-4-008385-1 2023.

- The World Health Organization WHO Global Lists of High Burden Countries for Tuberculosis (TB), TB/HIV and Multidrug/Rifampicin-Resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB). 2021-2025.; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. ISBN: 978-92-4-002943-9., 2021.

- The World Bank Group World Bank. "Incidence of Tuberculosis (per 100,000 People) - Mexico”. World Development Indicators. Https://Data.Worldbank.Org/Indicator/SH.TBS.INCD?Locations=MX.

- Sia, J.K.; Rengarajan, J. Immunology of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infections. Microbiol Spectr 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, P.F.P.S.; Teixeira, C.S.S.; Ichihara, M.Y.; Rasella, D.; Nery, J.S.; Sena, S.O.L.; Brickley, E.B.; Barreto, M.L.; Sanchez, M.N.; Pescarini, J.M. Incidence and Risk Factors of Tuberculosis among 420 854 Household Contacts of Patients with Tuberculosis in the 100 Million Brazilian Cohort (2004–18): A Cohort Study. Lancet Infect Dis 2024, 24, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, M.; Behr, M.A.; Dowdy, D.; Dheda, K.; Divangahi, M.; Boehme, C.C.; Ginsberg, A.; Swaminathan, S.; Spigelman, M.; Getahun, H.; et al. Tuberculosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016, 2, 16076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbota, G.; Bonnet, M.; Lienhardt, C. Management of Tuberculosis Infection: Current Situation, Recent Developments and Operational Challenges. Pathogens 2023, 12, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litvinjenko, S.; Magwood, O.; Wu, S.; Wei, X. Burden of Tuberculosis among Vulnerable Populations Worldwide: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Lancet Infect Dis 2023, 23, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumbacea, D.; Arend, S.M.; Eyuboglu, F.; Fishman, J.A.; Goletti, D.; Ison, M.G.; Jones, C.E.; Kampmann, B.; Kotton, C.N.; Lange, C.; et al. The Risk of Tuberculosis in Transplant Candidates and Recipients: A TBNET Consensus Statement. European Respiratory Journal 2012, 40, 990–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, R.L.; Dulley, F.L.; Suganuma, L.; França, I.L.; Yasuda, M.A.S.; Costa, S.F. Tuberculosis in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Patients: Case Report and Review of the Literature. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2010, 14, e187–e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, A. Tuberculosis in Allogeneic Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: So Many Unresolved Questions! Bone Marrow Transplant 2021, 56, 2050–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, A.; Mikulska, M.; De Greef, J.; Bondeelle, L.; Franquet, T.; Herrmann, J.-L.; Lange, C.; Spriet, I.; Akova, M.; Donnelly, J.P.; et al. Mycobacterial Infections in Adults with Haematological Malignancies and Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplants: Guidelines from the 8th European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia. Lancet Infect Dis 2022, 22, e359–e369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manual Operativo de La OMS Sobre La Tuberculosis. Módulo 1: Prevención. Tratamiento Preventivo de La Tuberculosis; Pan American Health Organization, 2022; ISBN 9789275325100.

- Park, J.H.; Choi, E.-J.; Park, H.-S.; Choi, S.-H.; Lee, S.-O.; Kim, Y.S.; Woo, J.H.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, K.-H.; et al. Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection Based on the Interferon-γ Release Assay in Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2020, 71, 1977–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, P.; Anwar, M.; Khan, B.; Altaf, C.; Ullah, K.; Raza, S.; Hussain, I. Role of Isoniazid Prophylaxis for Prevention of Tuberculosis in Haemopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients. J Pak Med Assoc 2005, 55, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lewinsohn, D.M.; Leonard, M.K.; LoBue, P.A.; Cohn, D.L.; Daley, C.L.; Desmond, E.; Keane, J.; Lewinsohn, D.A.; Loeffler, A.M.; Mazurek, G.H.; et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017, 64, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterling, T.R.; Njie, G.; Zenner, D.; Cohn, D.L.; Reves, R.; Ahmed, A.; Menzies, D.; Horsburgh, C.R.; Crane, C.M.; Burgos, M.; et al. Guidelines for the Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC, 2020. MMWR. Recommendations and Reports 2020, 69, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ron-Magaña, A.L.; Fernandez-Vargas, O.E.; Barrera-Chairez, E.; Ron-Guerrero, C.S.; Bañuelos-Ávila, A.J. BEAM-Modified Conditioning Therapy with Cisplatin+Dexamethasone Instead of Carmustine Prior to Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT) in Patients with Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Ann Transplant 2019, 24, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourlon, C.; Camacho-Hernández, R.; Fierro-Angulo, O.M.; Acosta-Medina, A.A.; Bourlon, M.T.; Niembro-Ortega, M.D.; Gonzalez-Lara, M.F.; Sifuentes-Osornio, J.; Ponce-de-León, A. Latent Tuberculosis in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategies to Prevent Disease Activation in an Endemic Population. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2020, 26, 1350–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Lima, V.A.C.; Santos, A.P.T.; Musqueira, P.T.; Maluf, N.Z.; Ramos, J.F.; Mariano, L.; Rocha, V.; Costa, S.F. Prevalence of Latent Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Comparing Tuberculin Skin Test and Interferon-Gamma Release Assay. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 2023, 42, 899–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Rodrigues, M.; de Almeida Testa, L.H.; dos Santos, A.C.F.; Zanetti, L.P.; da Silva Ruiz, L.; de Souza, M.P.; Colturato, V.R.; Machado, C.M. Latent and Active Tuberculosis Infection in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients: A Prospective Cohort Study. Bone Marrow Transplant 2021, 56, 2241–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mert, D.; Ozer, M.; Merdin, A.; İskender, G.; Uncu Ulu, B.; Kizil Çakar, M.; Dal, M.S.; Altuntaş, F.; Ertek, M. Latent Tuberculosis in Adult Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Recipients: Clinical Experience from a Previously Endemic Population. Medicine 2022, 101, e31786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumbacea, D.; Arend, S.M.; Eyuboglu, F.; Fishman, J.A.; Goletti, D.; Ison, M.G.; Jones, C.E.; Kampmann, B.; Kotton, C.N.; Lange, C.; et al. The Risk of Tuberculosis in Transplant Candidates and Recipients: A TBNET Consensus Statement. European Respiratory Journal 2012, 40, 990–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.; Lee, M.; Jung, I.; Kim, E.; Hahn, S.M.; Kim, Y.R.; Lim, S.; Ihn, K.; Kim, M.Y.; Ahn, J.G.; et al. Changes in Tuberculosis Risk after Transplantation in the Setting of Decreased Community Tuberculosis Incidence: A National Population-Based Study, 2008–2020. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2024, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, N.; Aggarwal, M.; Kapoor, J.; Ahmed, R.; Shrestha, A.; Kaushik, M.; Bhurani, D. Incidence and Clinical Profile of Tuberculosis after Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Transplant Infectious Disease 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.-Z.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Wu, Y.-J.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Zhang, J.-N.; Fu, H.-X.; Wang, J.-Z.; Wang, F.-R.; Yan, C.-H.; Mo, X.-D.; et al. Frequency, Risk Factors, and Outcome of Active Tuberculosis Following Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2020, 26, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-J.; Lee, D.-G.; Choi, S.-M.; Park, S.H.; Cho, S.-Y.; Choi, J.-K.; Kim, S.-H.; Choi, J.-H.; Yoo, J.-H.; Cho, B.-S.; et al. The Demanding Attention of Tuberculosis in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Recipients: High Incidence Compared with General Population. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0173250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordonnier, C.; Martino, R.; Trabasso, P.; Held, T.K.; Akan, H.; Ward, M.S.; Fabian, K.; Ullmann, A.J.; Wulffraat, N.; Ljungman, P.; et al. Mycobacterial Infection: A Difficult and Late Diagnosis in Stem Cell Transplant Recipients. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2004, 38, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akı, Ş.Z.; Sucak, G.T.; Tunçcan, Ö.G.; Köktürk, N.; Şenol, E. The Incidence of Tuberculosis Infection in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Recipients: A Retrospective Cohort Study from a Center in Turkey. Transplant Infectious Disease 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, S.-C.; Tang, J.-L.; Hsueh, P.-R.; Luh, K.-T.; Yu, C.-J.; Yang, P.-C. Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2001, 27, 1293–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tengan, F.M.; Figueiredo, G.M.; Leite, O.H.; Nunes, A.K.; Manchiero, C.; Dantas, B.P.; Magri, M.C.; Barone, A.A.; Bernardo, W.M. Prevalence of Multidrug-resistant Tuberculosis in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Tropical Medicine & International Health 2020, 25, 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, D.; Adjobimey, M.; Ruslami, R.; Trajman, A.; Sow, O.; Kim, H.; Obeng Baah, J.; Marks, G.B.; Long, R.; Hoeppner, V.; et al. Four Months of Rifampin or Nine Months of Isoniazid for Latent Tuberculosis in Adults. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 379, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Health Organization Latent Tuberculosis Infection: Updated and Consolidated Guidelines for Programmatic Management; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. ISBN: 978-92-4-155023-9, 2018.

- García-García, J.-M.; Rodrigo Sanz, T.; Quirós Fernández, S.; de la Rosa Carrillo, D. Shortage of Fixed-Dose Combination of Antituberculous Drugs in Spain. Archivos de Bronconeumología (English Edition) 2020, 56, 118–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, A.R.; Cooper, R.; Khan, F.A. Responsible Use of Rifampin in Canada Is Threatened by Irresponsible Shortages. Can Med Assoc J 2019, 191, E1139–E1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranzani, O.T.; Pescarini, J.M.; Martinez, L.; Garcia-Basteiro, A.L. Increasing Tuberculosis Burden in Latin America: An Alarming Trend for Global Control Efforts. BMJ Glob Health 2021, 6, e005639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sáez-Garrido, M.; Espuny-Miró, A.; Ruiz-Gómez, A.; Díaz-Carrasco, M.S. Drug-Drug Interactions in Patients Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Systematic Review. Farm Hosp. 2021, 45, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.P.; Kusztos, A.E.; Bold, T.D.; Ho, V.T.; Glotzbecker, B.E.; Hsieh, C.; Baker, M.A.; Baden, L.R.; Hammond, S.P.; Marty, F.M. Risk of Latent Tuberculosis Reactivation After Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2019, 69, 869–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.A.; Seo, S.K. How I Prevent Infections in Patients Receiving CD19-Targeted Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells for B-Cell Malignancies. Blood 2020, 136, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, M.; Nagavally, S.; Dhakal, B.; Chhabra, S.; D’Souza, A.; Hari, P. Risk of Infections with BCMA-Directed Immunotherapy in Multiple Myeloma. Blood 2021, 138, 1626–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, M.H.; Kremer, J.M.; Jahreis, A.; Vernon, E.; Isaacs, J.D.; van Vollenhoven, R.F. Integrated Safety in Tocilizumab Clinical Trials. Arthritis Res Ther 2011, 13, R141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Huang, L.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, C.; Wan, D.; Wei, J.; Cao, Y. Case Report: Active Tuberculosis Infection in CAR T-Cell Recipients Post CAR T-Cell Therapy: A Retrospective Case Series. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, K.; Sahu, G.; Burns, E.; Ensor, A.; Ensor, J.; Pingali, S.R.; Subbiah, V.; Iyer, S.P. Mycobacterial Infections Due to PD-1 and PD-L1 Checkpoint Inhibitors. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e000866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan, E.A.; Graetz, V.; Allerheiligen, J.; Zillikens, D.; Rupp, J.; Terheyden, P. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Tuberculosis: An Old Disease in a New Context. Lancet Oncol 2020, 21, e55–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, K.; Shekarkhand, T.; Costa, B.A.; Nemirovsky, D.; Derkach, A.; Nishimura, N.; Farzana, T.; Rueda, C.; Chung, D.; Landau, H.; et al. A Comparative Analysis of Infectious Complications in Patients with Multiple Myeloma Treated with BCMA-Targeted Bispecific Antibodies and CAR T-Cell Therapy. Blood 2023, 142, 1957–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, H. Management of Adverse Effects in CAR T-Cell Therapy. Rinsho Ketsueki 2023, 64, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, A.; Shi, J.; Luo, Y.; Ye, Y.; Tan, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhao, Y. Allo-HSCT Recipients with Invasive Fungal Disease and Ongoing Immunosuppression Have a High Risk for Developing Tuberculosis. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 20402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compagno, M.; Navarra, A.; Campogiani, L.; Coppola, L.; Rossi, B.; Iannetta, M.; Malagnino, V.; Parisi, S.G.; Mariotti, B.; Cerretti, R.; et al. Latent Tuberculosis Infection in Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients: A Retrospective Italian Cohort Study in Tor Vergata University Hospital, Rome. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 10693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, J.A.G.; Cruz, A.B.; Virata, Ma.P.; Calavera, A.; Abad, C.L. A Retrospective Review of Infections and Outcomes within 100 Days of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Insights from a New Transplant Program in the Philippines. IJID Regions 2022, 3, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Moreno, A.; Narita, M.; Spitters, C.; Swetky, M.; Podczervinski, S.; Lind, M.L.; Holmberg, L.; Liu, C.; Edelstein, R.; Pergam, S.A. A Targeted Screening Program for Latent Tuberculosis Infection Among Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, W.-C.; Liu, C.-J.; Hong, Y.-C.; Feng, J.-Y.; Su, W.-J.; Chien, S.-H.; Chen, T.-J.; Chiang, C.-H. Long-Term Risk of Tuberculosis in Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients: A 10-Year Nationwide Study. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2015, 19, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sester, M.; van Leth, F.; Bruchfeld, J.; Bumbacea, D.; Cirillo, D.M.; Dilektasli, A.G.; Domínguez, J.; Duarte, R.; Ernst, M.; Eyuboglu, F.O.; et al. Risk Assessment of Tuberculosis in Immunocompromised Patients. A TBNET Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014, 190, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.M.; Lee, S.-O.; Choi, S. -H.; Kim, Y.S.; Woo, J.H.; Yoon, D.H.; Suh, C.; Kim, D. -Y.; Lee, J. -H.; Lee, J.; et al. Comparison of the <scp>Q</Scp> Uanti <scp>FERON</Scp> - <scp>TB G</Scp> Old <scp>I</Scp> N- <scp>T</Scp> Ube Test with the Tuberculin Skin Test for Detecting Latent Tuberculosis Infection Prior to Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Transplant Infectious Disease 2013, 15, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).