1. Introduction

Wood’s relevance as a building material has grown due to increased environmental awareness and wood’s ability to store carbon, which plants receive as carbon dioxide from the atmosphere via photosynthesis. New procedures for increasing the characteristics of wood have been developed, expanding the area of its use and the range of conceivable applications [

1]. This situation underscores the significant reliance on high-quality wood species, prompting the exploration of alternative, underutilized wood sources due to limitations in forest area and available volume of such premium wood. Consequently, the veneer-based industry is actively seeking substitutes for high-quality birch (

Betula pendula Roth), considering lower-value hardwood species like grey alder (

Alnus Incana), black alder (

Alnus glutinosa), and aspen (

Populus tremula L.). These species, characterized by lower density, hardness, and mechanical properties, are initially less appealing to the industry.

However, research suggests that wood densification presents a viable avenue for enhancing wood’s performance, thus potentially promoting the utilization of these alternative, low-value wood species [

2,

3,

4]. This favourable process enhances various aspects of wood, including density, strength, and hardness [

5]. Particularly significant for low-density wood, densification improves its suitability for advanced engineering structures and applications [

6]. Wood density, a key characteristic influenced by densification, holds considerable importance for the forest industry, impacting the suitability of wood as a raw material for wood polymer composites [

7].

Screws have become increasingly common in plywood applications, where it is used as a construction material. However, low density wood species do not have enough screw withdrawal capacity when used in construction or packaging. The screw withdrawal resistance in plywood is influenced by various factors such as wood species, surface hardness, density, and shear strength. The withdrawal capacity of screws is affected by the wood species. Ayteking et al. showed that high density wood species such as oak wood exhibited the highest screw withdrawal resistance, followed by Stone pine (

Pinus pinea), black pine (

Pinus thunbergia), and fir (

Pinaceae) [

8]. The withdrawal capacity of wood screws is positively correlated with wood density, as evidenced by a study on Japanese larch cross-laminated timber demonstrated that with a density increment of 0.05 g/cm

3, the withdrawal capacity increased by an average of 9.4% [

9]. Similarly, it has been reported that there is a positive linear relationship between the withdrawal capacity of the screw and specific gravity [

10]. The relationship between residual density and screw withdrawal capacity has been found to be directly proportional, indicating that screw withdrawal capacity decreases as wood density decreases through biodegradation [

11]. Furthermore, the shear strength of wood is a crucial factor in assessing screw withdrawal load resistance, as it describes the connection between wood fibres and the screw [

12]. Mclain’s work suggests that smaller diameter fasteners in low density species may require a change in design strength [

13]. The established relationship between wood density and screw withdrawal capacity suggests that lower density corresponds to decreased screw withdrawal capacity, while higher density correlates with increased capacity [

11,

14]. These findings underscore the pivotal role of wood density in determining fastener withdrawal capacity. Consequently, research aims to densify low-density wood species to enhance their screw withdrawal capacity.

In veneer-based products it is possible to densify each veneer layer separately and combine them in composites such way that you can only have outer layers densified to achieve optimal strength. In this case, the surface hardness will be important factor that is shown to significantly increase with the densification process [

15]. Furthermore, radial densification of wood has been shown to enhance its hardness across three anatomical directions [

16], while surface densification has demonstrated significant improvements in the Janka hardness of wood, particularly at higher pressing temperatures [

17]. This process also holds promise for enhancing the hardness of the outer layers of veneer-based products, thereby opening new avenues for the utilization of low-density species [

18], which in turn contributes to increased screw withdrawal capacity [

19]. Furthermore, in hybrid cross-laminated timber, the withdrawal resistance of screws is influenced by the contact area between the screw and the wood material, revealing a link between withdrawal resistance and hardness [

20]. This relationship extends to various panel materials, where screw withdrawal capacity increases with higher panel density and cellulose nanofibrils (CNF) addition ratio, indicating a correlation between hardness and screw withdrawal capacity [

21]. Notably, improvements in wood’s strength properties resulting from densification have been shown to enhance the holding capacity of fasteners [

22]. Moreover, research underscores the significant impact of wood densification on the withdrawal capacity of nails (up to 200 %) and screws (up to 140 %) [

23].

Here, we addressed the need to support or disapprove the claim that using the densified low-value wood as plywood face veneers will increase the fastener holding capacity enough for construction applications. We investigated the relationship between wood density, surface hardness and screw withdrawal capacity. For this, we used low-value and low-density wood species such as aspen and black alder to be densified and used in plywood face veneers or all layers. We tested the hypothesis that adding only densified face veneer in the plywood will increase the fastener holding capacity of the whole plywood panel and with harder surfaces we will get higher screw holding capacity. The low-value hardwood species were peeled to veneers and made into plywood with laboratory pilot scale veneer and plywood production line. We then densified low-value hardwood face veneers and used them in plywood top and bottom layers looking for relationships between surface hardness and screw withdrawal capacity of plywood made of different low-value hardwood species with and without the densification.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Veneer Preparation

This study used veneers from three distinct hardwood species for plywood production: silver birch (

Betula pendula Roth), black alder (

Alnus glutinosa L.), and common aspen (

Populus tremula L.). Aspen and alder were selected as low-value and underutilized wood species in Estonia, offering alternative to extensively used birch in Nordic European plywood industry. These hardwood species despite having lower density and strength, have previously been established as suitable for alternative species to birch in plywood [

24,

25]. The logs were freshly felled in October 2022 at Järvselja, Tartu County, Estonia, Järvselja Learning and Experimental Forest Foundation. The birch trees had an average stand age of 59 years, black alder 26 years, and aspen 66 years, all weighted by area. The log nominal lengths were 3 m, and average diameters were 24 cm (birch), 26 cm (black alder), and 33 cm (aspen). The rotary-peeling method was based on our previous study by Kallakas et al. [

25]. The logs were cut into 1.3 m long peeler blocks and immersed in a water bath at 40 °C for 24 h. Before peeling, peeler blocks were debarked and various variables such as temperature, moisture content (MC), log length, and annual ring widths were measured. After that, peeler blocks were rotary peeled into 3.34 mm-thick green veneer using an industrial-sized peeling lathe (Model 3HV66; Raute Oyj, Lahti, Finland). Peeling speed was 60 m/min, knife sharpening angle 19° and compression rate 7%. After the peeling process, the veneer matt was cut into sheets with dimensions of 900 × 450 mm

2 using the pneumatic guillotine (Wärtsilä Corporation, Finland). Subsequently, veneer sheets where dried in a laboratory scale veneer dryer (Raute Oyj, Lahti, Finland) at 170 °C. The drying cycle durations varied based on wood species and veneer thickness, as outlined in

Error! Reference source not found.. After, veneers were stored at 25 °C and 20 % RH in the conditioned room to maintain a target moisture content of 4.5 ± 1.5 %, which is necessary for subsequent gluing applications.

Table 1.

Drying times of different hardwood veneer thicknesses.

Table 1.

Drying times of different hardwood veneer thicknesses.

| |

Veneer thickness (mm) |

| Wood species |

1.5 |

3.0 |

| Birch |

150 s |

|

| Black alder |

160 s |

390 s |

| Aspen |

170 s |

420 s |

2.2. Veneer Densification

Following conditioning and drying, veneers free of any wood flaws were picked out with care and then cut into 280 x 430 mm

2 pieces. After that, the specimens were densified with a thermo-mechanical process at Luleå University of Technology, located in Northern Sweden. Densified veneer samples with dimensions of 50 x 200 mm

2 were produced. The specimens were conditioned at 20 ± 2 °C and 65 ± 5 % RH until they reached equilibrium moisture content (EMC) prior to densification. Densification was made at relatively low temperatures by purposefully allowing an increase in MC to lower the glass-transition temperature [

26]. In a laboratory hot press (HLOP15, Höfer Presstechnik GmbH, Taiskirchen, Germany), the veneers were compressed uniaxially between heated plates (150 °C). 1.5 mm was set as target veneer thickness, which was upheld by mechanical stops. Target compression ratio was achieved by starting with beginning thicknesses of 3.0 and compressing down up to 50 %. After placing the specimens on the heated platen, the pressing cycle was started. A specimen lost about 1 % of its MC between the start of the cycle and complete contact with both press hotplates. To plasticize the wood, a low contact pressure was first applied and maintained for 10 s to raise the surface temperature. After that, the pressure was raised to achieve a compression rate of 0.1 m/s until the desired thickness was attained. The specimens were kept hot and under pressure for 240 s. Afterward, the press’s interior water circulation was used to cool the platens until they reached 35 °C (6 min). The pressure was removed once the cooling procedure was complete. Before undergoing any processing, each specimen was thereafter securely wrapped in plastic film to avoid moisture changes.

2.3. Plywood Manufactoring

The plywood lay-up schemes were developed using the standard cross-band construction approach, resulting in three plywood types with seven layers, as detailed in

Error! Reference source not found. and

Figure 1. Plywood specimens were prepared with the size of 200 × 50 mm. Undensified plywood serves as control (Type I), made with undensified 1.5 mm thick veneers while Type II and III are made of 3.0 mm densified and undensified face veneers, respectively. For the plywood making, phenol formaldehyde (PF) resin (Prefere Resins Finland Oy, Hamina, Finland) with solid content of 49% was used. Using an adhesive roller (Black Bros 22-D, Mendota, IL, USA), glue was applied to each glue line while the spread rate varied depending on wood species due to the different surface roughness. Total glue consumption was calculated by weighing the veneers before and after spreading (

Table 1). The panels were then subjected to hot pressing using a hydraulic press at 130°C with a pressing pressure of 1.4 MPa. For the study, a total of 90 plywood samples were constructed. To assess the effect of the densification, aspen and black alder veneers that were initially 3.0 mm thick were densified to 1.5 mm. The purpose of this stage was to study how densification of veneers will affect various plywood properties. After, specimens were cut into the respective dimensions for further testing and conditioned at in an environment with a 65% relative humidity and a temperature of 20 °C.

Table 2.

Plywood type description.

Table 2.

Plywood type description.

| Plywood type |

Abbreviation |

Lay-up |

| Undensified |

UN |

N1.5-N1.5-N1.5-N1.5-N1.5-N1.5-N1.5 |

| Face veneer densified |

FVD |

D3.0→1.5-N1.5-N1.5-N1.5-N1.5-N1.5- D3.0→1.5 |

| All veneers densified |

AVD |

D3.0→1.5- D3.0→1.5- D3.0→1.5- D3.0→1.5- D3.0→1.5- D3.0→1.5- D3.0→1.5

|

Figure 1.

Plywood lay-up schemes.

Figure 1.

Plywood lay-up schemes.

Table 1.

Glue consumptions of different plywood types.

Table 1.

Glue consumptions of different plywood types.

| Wood species |

Plywood type |

Glue consumption g/m2

|

| Birch |

UN |

160 (±10.6) |

| Black alder |

UN |

173 (±7.5) |

| FVD |

160 (±7.2) |

| AVD |

133 (±2.2) |

| Aspen |

UN |

165 (±10.9) |

| FVD |

159 (±19.3) |

| AVD |

136 (±7.2) |

2.4. Density Determination

The density of densified and undensified plywood samples was determined in accordance with EN 323:2002 [

27]. A sliding calliper was used to measure length, width, and thickness to an accuracy of 0.01 mm. The test specimens were weighed on a balance with an accuracy of 0.001 g. The test specimens were cut into squares with nominal side lengths of 50 mm. Overall, 90 samples were evaluated. The test specimens with constant mass were conditioned in an environment with a 65 % RHand a temperature of 20 °C. The density of plywood samples was calculated by dividing the weight of the specimens with volume.

2.5. Brinell Hardness Determination

The Brinell hardness values of the densified and undensified plywood samples were determined using the procedures outlined in the EN 1534:2020 [

28]. Prior to testing, specimens were conditioned in an environment with a 65 % relative humidity and a temperature of 20 °C. Then the specimen’s surface was indented with a 10 mm diameter hardened steel ball under a 1000 N load for 25 s using the universal electromechanical testing machine (Zwick/Roell Z050, ZwickRoell GmbH, Germany). The diameter of the indentation left in the specimen was measured using a calliper with an accuracy of 0.01 mm. The Brinell hardness number was obtained by dividing the applied load by the area of the indentation. Overall, 90 samples were evaluated.

2.6. Screw Withdrawal Capacity and Load Determinatio

All tests for the screw withdrawal capacity and load determination were conducted on the universal electromechanical testing machine (Zwick/Roell Z050, ZwickRoell GmbH, Germany) according to EN 13446:2002 [

29]. Prior to testing, specimens were conditioned in an environment with a 65 % RH and a temperature of 20 °C until constant mass was achieved. Screw withdrawal capacity test was done from the tangential section of densified and undensified plywood surface. Crosshead loading rate of 2 mm/min was applied until maximum load was achieved. Ultimate withdrawal load was determined, and screw withdrawal capacity was calculated dividing the ultimate load with radius and penetration depth of the screw. For that, 3.0 × 50 mm galvanized wood screws were used in this test and overall, 90 samples were evaluated.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, a one-way ANOVA was performed on all groups with an alpha level of 0.05. When a significant p-value was observed, the Bonferroni correction was applied by adjusting the alpha level for multiple comparisons (t-tests). The new alpha level was set at 0.017 for three comparisons. The Pearson correlation coefficients (r) and corresponding p-values were computed using MS Excel’s Data Analysis Toolpak/Regression to assess the strength and direction of the relationships between variables, such as density and Brinell hardness and screw withdrawal capacity.

3. Results and Discussion

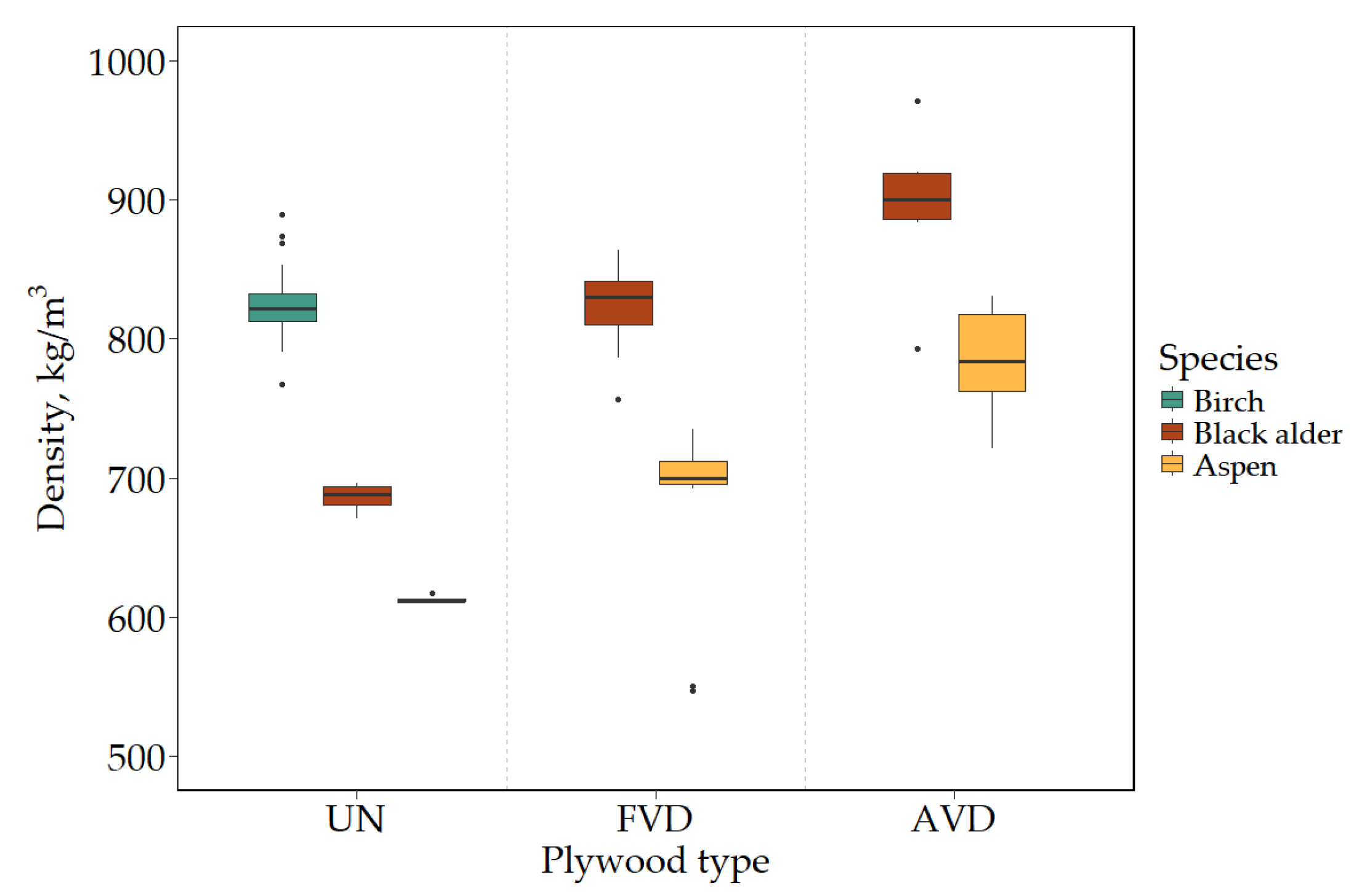

3.1. Density of Plywood

To see how wood densification will affect low-value hardwood species-based plywood densities and how they compare to standard birch plywood, we made samples with all layers densified (AVD) and only face veneers densified (FVD) and compared them with undensified (UN) samples. The plywood samples made from different hardwood species and densified veneer layers are shown on Error! Reference source not found.. From these results we can see that density of plywood is significantly (p<0.017) influenced by the hardwood species used. Veneer densification clearly increases the density of aspen and black alder plywood. As expected, the highest density was achieved when all layers of plywood were densified. Black alder FVD and AVD plywood stands out by gaining the similar or higher than 824.30 kg/m3 density of UN birch plywood (821.98 kg/m3 and 896.73 kg/m3, respectively). Furthermore, black alder AVD plywood showed 72.43 kg/m3 higher (p=0.005) density than birch UN plywood.

Within aspen and black alder plywood samples, all the different plywood types showed significant differences in densities (p<0.017), proving that densifications greatly influenced the density of plywood. This is understandable when considering that higher number of densified veneers in plywood will also increase the overall plywood panel density. Similarly, Bekhta et al. showed that wood species and different types of veneer densification have great effects on plywood density [

30]. Madhoushi et al. showed that 50% densification level will increase the plywood density nearly two times [

31]. In our case we had 50% densification ratio of black alder and aspen veneers. These densified veneers were added into plywood lay-up as face veneers (FVD) or in all layers (AVD). In the instance of black alder, we observed a 20 % and 31 % increase in density for FVD and AVD plywood, respectively as compared to UN plywood while with aspen, similarly we saw a 11 % and 28 % increase in density for FVD and AVD plywood, respectively as compared to UN plywood. The density of plywood is also influenced by the glue consumption [

24,

31]. In our study we saw deviation in glue spread rates (

Table 1) where AVD plywood had less glue consumption due to compressed structure and smoother surfaces (not measured in this study). Though, density of these plywood types (AVD) was still the highest, emphasize how significantly the final plywood density is affected by the addition of densified veneers into plywood.

Figure 2.

Average density values for the tested plywood types.

Figure 2.

Average density values for the tested plywood types.

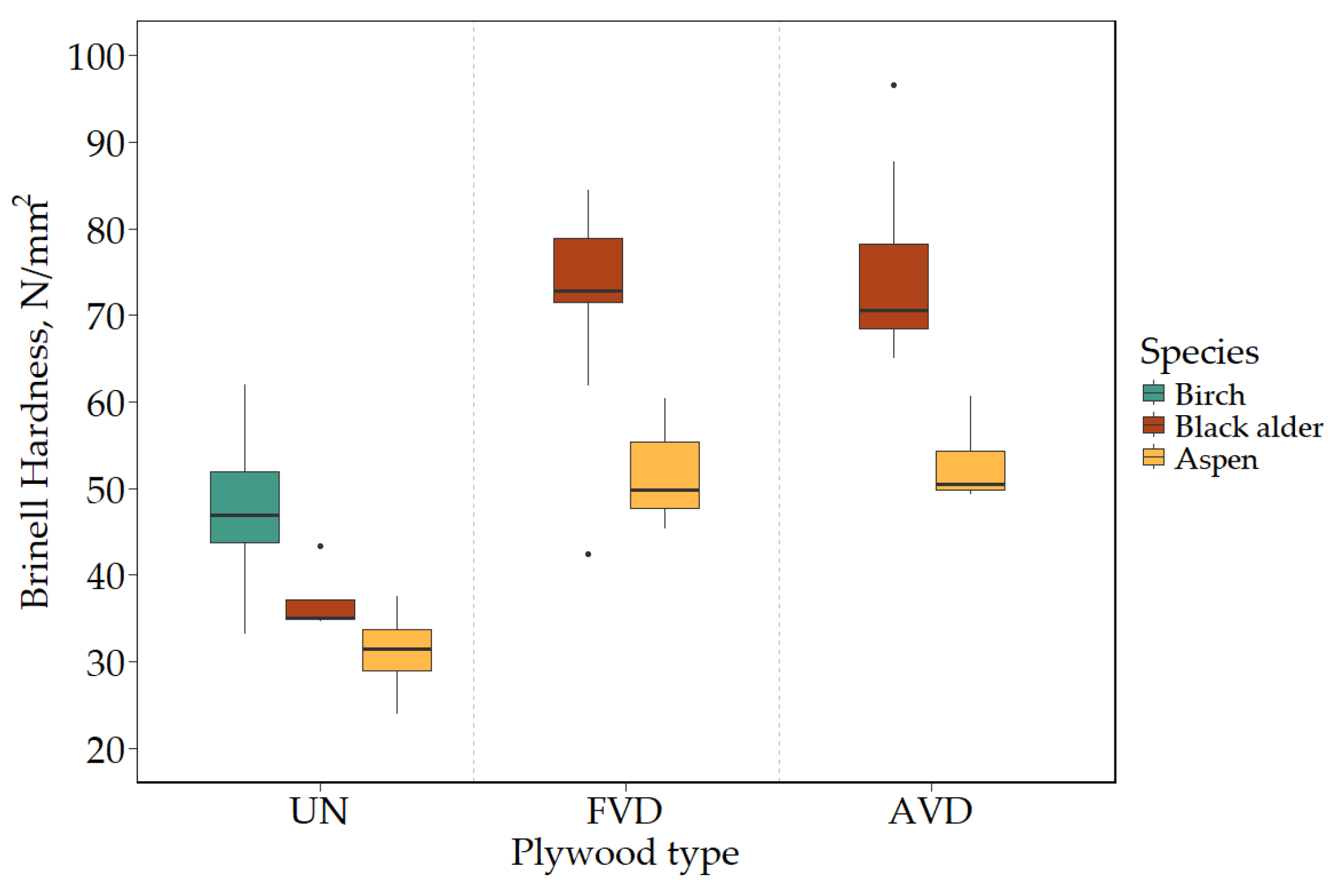

3.2. Brinell Hardness of Plywood

From the previous chapter it was seen that compressing the veneers will increase the overall density of the plywood. In here we see that veneer densification will also lead to significant (p<0.017) increase in Brinell hardness compared to UN plywood (see

Error! Reference source not found.). The Brinell hardness of FVD aspen and black alder plywood was 65 % and 93 % higher, respectively, compared to UN plywood. This significant change in hardness due to densification has been preciously found in several research studies and could be attributed to the closing of the vessel and fibre lumens as well as lathe check conglutination [

32,

33,

34,

35]. However, we saw no significant (p>0.5) increase compared to FVD plywood in Brinell hardness when all layers of plywood lay-up were densified (AVD). This could be explained with the Brinell hardness measurement method, where hardness is only obtained from the one surface of the plywood panel and other layers do not have effect on the hardness of the plywood. Previous studies have highlighted that hardness values are greatly dependant on the wood density and force applied to wood composite and the deeper the indenter penetrates, the more the values are influenced by the undensified wood’s hardness [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Furthermore, it is shown Brinell hardness can benefit from more layers of densified wood in the composite [

41]. With our data we did not observe these effects. We measured the Brinell hardness with the constant applied force of 1000 N and the results of the hardness tests were largely governed by the face veneer density rather than the entire plywood layup.

When comparing the densification effect of low-value wood species to the hardness of birch control UN plywood samples, it is evident that densification significantly increases the surface hardness of low-value wood, matching or even surpassing that of birch. (Error! Reference source not found.). Aspen FVD plywood had similar surface hardness to birch (p=0.041), while AVD samples showed slightly higher surface hardness than birch (p=0.013). At the same time, black alder FVD and AVD plywood samples had significantly (p<0.017) higher surface hardness than UN birch plywood.

The hardness data revealed that both species saw an increase in Brinell hardness from control specimens for both densified plywood types, with only a little difference between them (FVD and AVD, respectively). Increasing surface hardness by densification broadens the variety of uses for low-value species, particularly in furniture applications where the material is exposed to the user as well as in flooring applications.

Figure 3.

Average hardness values for the tested plywood types.

Figure 3.

Average hardness values for the tested plywood types.

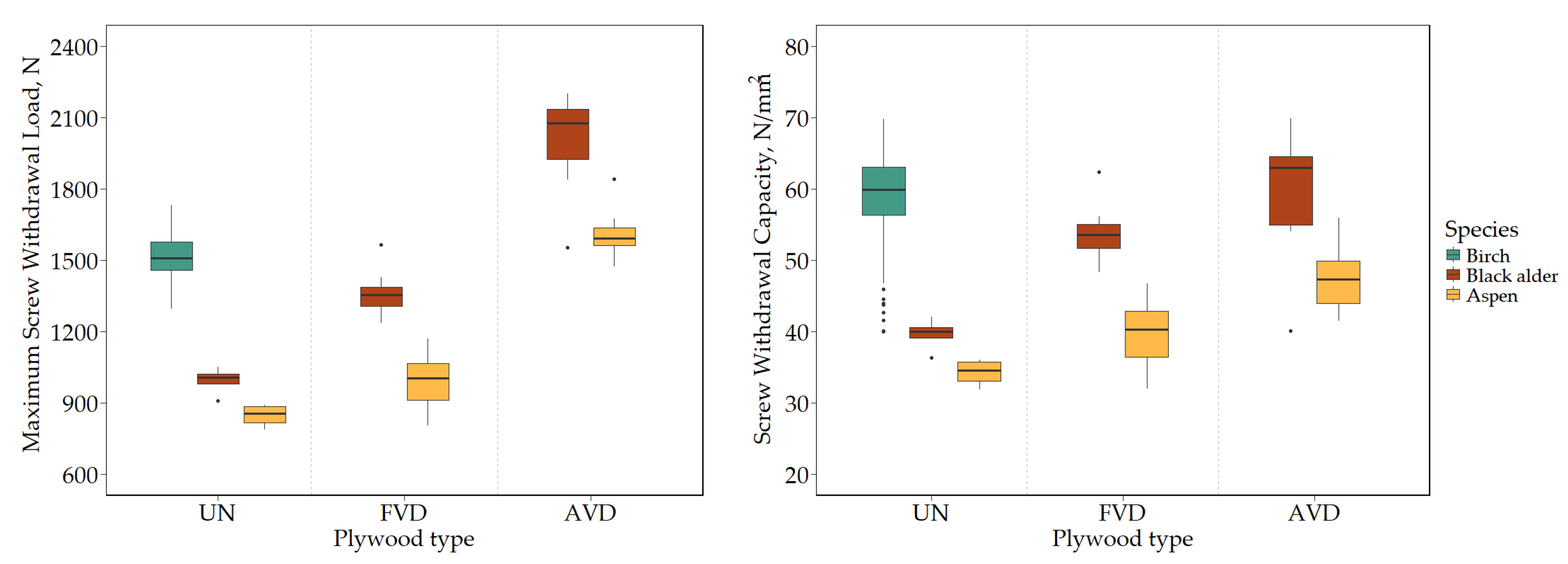

3.3. Screw Withdrawal Load and Capacity of Plywood

We looked for the densification effect on low-value hardwood plywood screw holding properties. Positive trend of veneer densification is clearly visible on both, screw withdrawal load and capacity (Error! Reference source not found.). In here we see that in case of black alder (AVD plywood type), the veneer densification leads to highest screw withdrawal load (1997.79 N) and capacity (59.38 N/mm2). However, it is still not significantly higher (p=0.022) from birch UN plywood screw withdrawal capacity (57.87 N/mm2). Another thing that strikes here, is that addition of more densified layers into black alder plywood lay-up did not much improve screw withdrawal capacity, only by 5.74 N/mm2 (FVD versus AVD plywood), which was not significant (p=0.140). That’s not the case with maximum screw withdrawal load, where the AVD shows clearly significantly (p<0.017) higher maximum withdrawal load than FVD plywood. That’s reasonable because of the set recovery effect in densified plywood samples, where AVD plywood thickness gets higher than the FVD plywood thickness, when densified veneers expand during time. Due to that, screw withdrawal capacity, which is calculated from load divided by thickness, reduces its significance. On the other hand, when we only measure load (not counting the thickness), then we still have the actual high significance between FVD and AVD plywood types.

Aspen fibres are generally loose in wood products that leads to low fastener holding strength. In here we are looking to improve aspen screw holding capacity by veneer densification that leads to more compact structure of wood. When looking at the veneer densification effect on aspen plywood types, then we can see a significant (p<0.017) increase in both, screw withdrawal load and capacity for all the plywood types as compared to UN plywood. This improvement could be attributed to compressed fibres and compact structure of densified wood which leads to better connection between screw threads and wood, that increases with higher number of densified layers in plywood lay-up. On the other hand, none of the densified aspen plywood types reached to birch UN plywood in screw withdrawal capacity.

Based on our data, we can say that we are able to greatly improve the screw holding capacity (35% and 16% for FVD black alder and aspen, respectively) by just adding a face layer of densified wood on to plywood as compared to UN plywood. Higher improvements were achieved when all layers of plywood where densified (50 % and 38 % for AVD black alder and aspen, respectively) as compared to UN plywood.

Figure 4.

Average screw withdrawal load (Left) and capacity (Right) values for the tested plywood types.

Figure 4.

Average screw withdrawal load (Left) and capacity (Right) values for the tested plywood types.

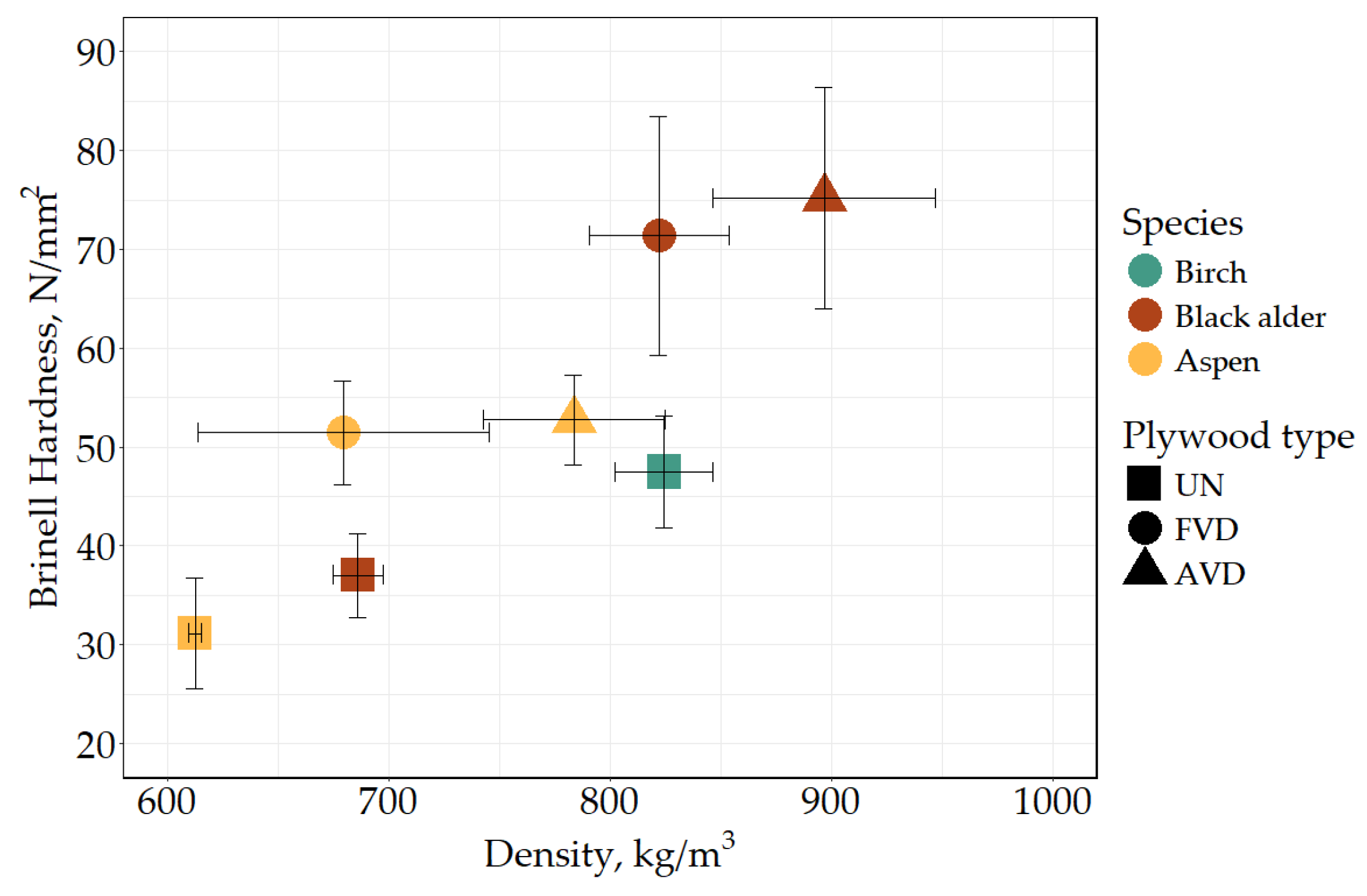

3.4. Density-Specific Mechanical Properties

In this research we had plywood samples with varying densities (UN, FVD, AVD). Density increase of plywood was achieved by adding densified veneer layers to plywood lay-up. We also saw above that surface hardness was increased by adding densified layers to plywood. To see if there are any correlations and to understand the effect of density on the surface hardness of plywood, the density values are plotted against the Brinell hardness (Error! Reference source not found.). The firsts thing that stands out is that the highest density (AVD plywood) does not give a significant increase to surface hardness when compared to FVD plywood. As said before, this could be elucidated using the Brinell hardness measurement method, which derives hardness solely from one surface of the plywood panel, less affected by the other layers within the plywood.

Next, we looked at how well density of plywood can correlate to surface hardness. The data for all the plywood samples combined gives positive correlation of

r = 0.50 and

p < 0.05, suggesting that plywood density has impact on surface hardness. When looking at the different plywood types, then we can see that adding one layer of densified veneer (FVD plywood type) will have positive correlation (

r = 0.54 and

p < 0.05 for aspen plywood and

r = 0.92 and

p < 0.05 for black alder plywood) with density and surface hardness as compared to UN plywood. With AVD plywood types, the significant positive correlations compared to UN plywood stay the same. However, when adding more layers of densified veneers into plywood lay-up, thereby increasing the overall density of the plywood, the surface hardness increase is not significant. In this case we see only slight positive correlations between density and surface hardness which are not significant (

r = 0.36 and

p = 0.13 for FVD vs. AVD aspen plywood and

r = 0.38 and

p = 0.12 for FVD vs. AVD black alder plywood). This suggests that surface hardness is only significant influenced by the top layer density of the plywood. Although, surface hardness could also be influenced by the force exerted on the wood composite, as the indenter penetrates deeper, the values could be increasingly influenced by the hardness of the undensified wood [

36,

37,

38]. In this study we kept force constant (1000 N) and did not observe this effect.

Figure 5.

Plywood density vs. surface hardness.

Figure 5.

Plywood density vs. surface hardness.

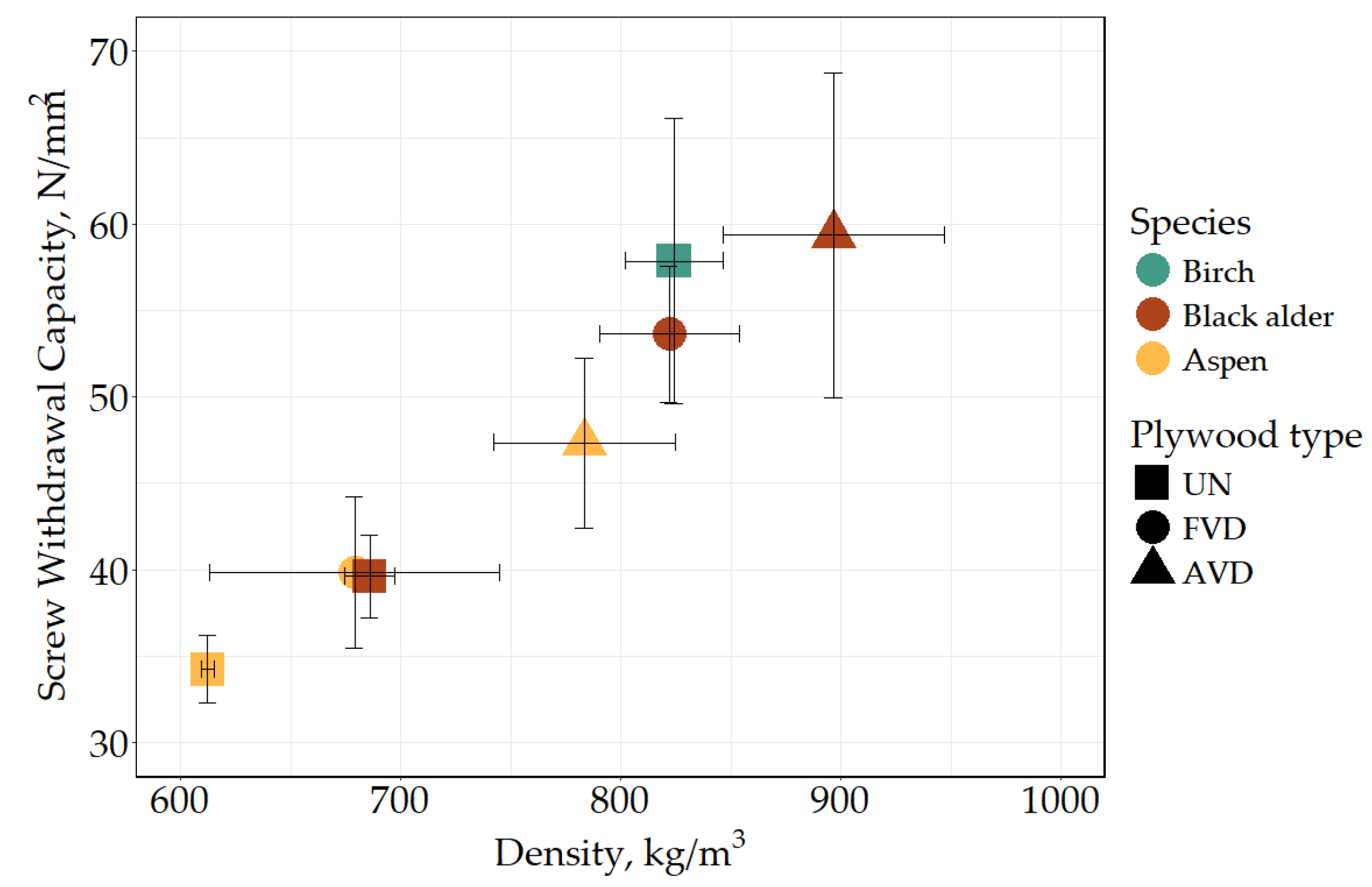

We saw previously that screw withdrawal capacity was positively correlated with plywood type (

Error! Reference source not found.). Therefore, we looked how well does it correlate with plywood density. As expected, screw withdrawal capacity was heavily influenced by the plywood density (

Error! Reference source not found.) and all our plywood types had statistically significant strong positive correlation between plywood density and screw withdrawal capacity (

r = 0.776 and

p < 0.05). These strong positive correlations stayed the same between all the plywood types within the wood species. This is consistent with the general tendency for wood materials to have higher screw withdrawal capacity when wood density is higher [

42,

43,

44,

45]. It also supports our hypothesis, that increasing the low-value wood density by densification will lead to higher screw holding capacity. However, when looking at density increase versus screw withdrawal capacity in comparison with birch UN plywood, then only black alder manages to reach to similar screw withdrawal capacity. While density of the black alder AVD plywood is 9% higher than birch UN plywood (

p = 0.005), the screw withdrawal capacity difference is not significant (

p = 0.681).

Figure 6.

Plywood density vs. screw withdrawal capacity.

Figure 6.

Plywood density vs. screw withdrawal capacity.

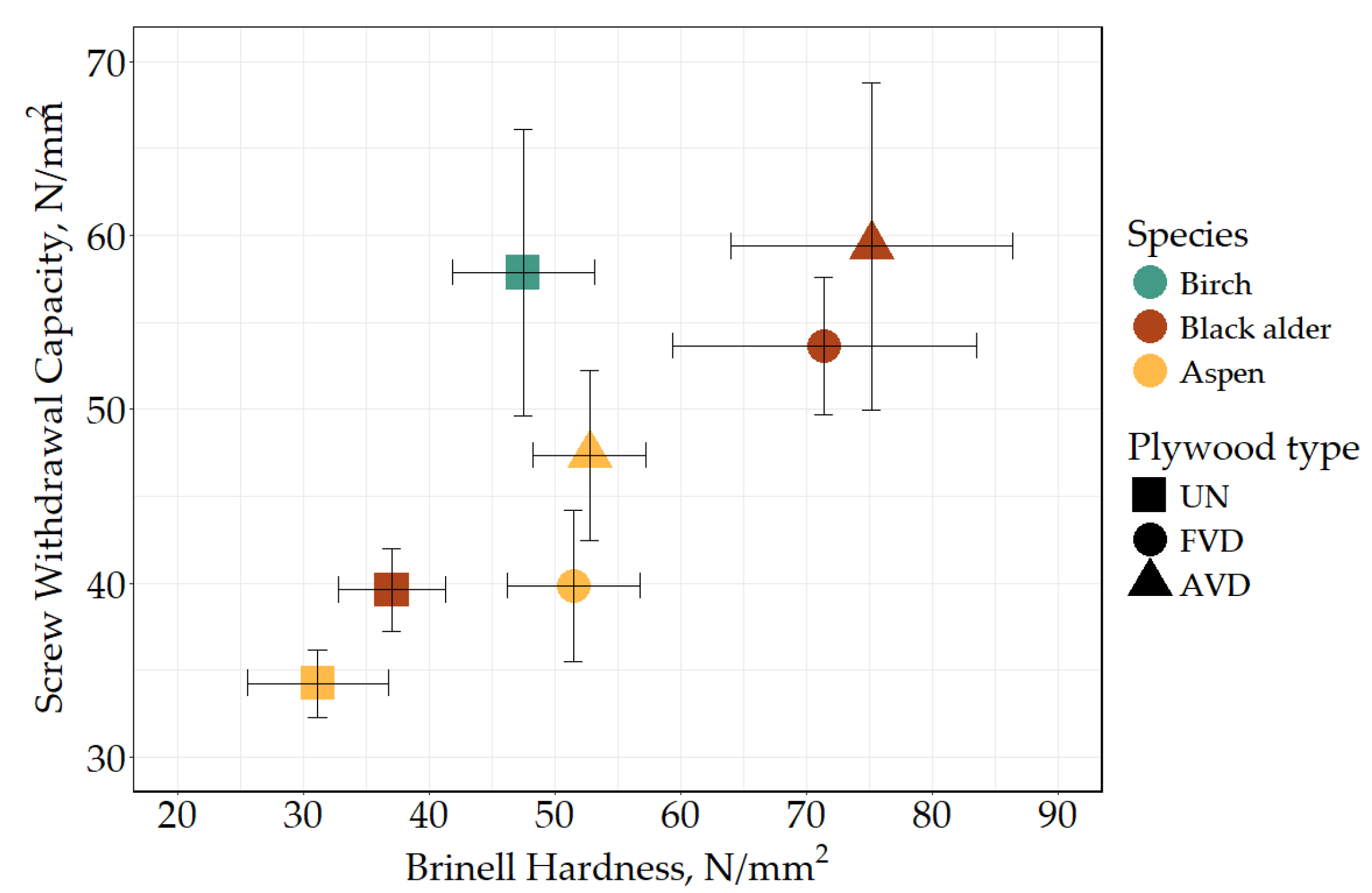

Because surface hardness is one of the main properties that is greatly influenced by the wood densification as seen above (Error! Reference source not found.) it is also important to consider how well does surface hardness contribute to screw withdrawal capacity. The positive effect of increasing the surface hardness on screw withdrawal capacity is visible on (Error! Reference source not found.). After adding one layer of densified aspen veneer with higher surface hardness to aspen plywood, the screw withdrawal capacity is increased by 16 % (comparing aspen UN plywood to aspen FVD plywood type) which gives positive correlation of r = 0.495 between surface hardness and screw withdrawal capacity, although not significant (p = 0.061). Correlation is improved when all layers are densified (comparing aspen UN plywood to aspen AVD plywood type) giving significant positive correlation of r = 0.568 and p = 0.004. However, with black alder we see a lot higher (35 %) screw withdrawal capacity increase with surface hardness increase from black alder UN plywood to black alder FVD plywood which gives significant strong positive correlation between surface hardness and screw withdrawal capacity (r = 0.863 and p <0.05). Conversely, we saw only slight positive correlations which were not significant (r = 0.330, p = 0.167 and r = 0.316, p = 0.200 for aspen and black alder plywood, respectively) between surface hardness and screw withdrawal capacity when adding more layers of densified veneers to plywood lay-up (from FVD plywood to AVD plywood type). Despite that surface hardness did not improve significantly from FVD plywood to AVD plywood, it still increased the screw withdrawal capacity by 19 % (p = 0.004) for aspen plywood and by 11% (p = 0.140) for black alder plywood which fell short on our set threshold for statistical significance, 0.05.

This suggests that screw withdrawal capacity is affected more on the compact and dense wood structure, rather than wood surface hardness. Though we observed positive correlations between UN and FVD plywood surface hardness and screw withdrawal capacity, it is seen that density has a major role in determining screw withdrawal capacity. Our data implies that densifying and increasing the low-value wood density might be the route to improved screw withdrawal capacity of plywood. This is consistent with the use of higher density wood to get higher fastener holding capacity [

42,

43,

44,

45].

Figure 7.

Plywood surface hardness vs. screw withdrawal capacity.

Figure 7.

Plywood surface hardness vs. screw withdrawal capacity.

4. Conclusions

The goal of this study was to investigate how the densification of low-value wood veneers will increase the plywood screw withdrawal capacity and surface hardness when added in the plywood lay-up either on replacing surface layers or all layers. We examined the correlation between wood density, surface hardness, and screw withdrawal capacity. To achieve this, we densified low-value, low-density wood species such as aspen and black alder and applied them to plywood lay-up as face veneers or in all layers.

We observed that densifying low-value wood veneers and incorporating them into the plywood lay-up significantly increases the overall density of the plywood. However, only black alder AVD plywood gained higher density than birch UN plywood.

We observed a statistically significant positive correlation (r = 0.776 and p < 0.05) between plywood density and screw withdrawal capacity which stayed the same with all the plywood types within the different wood species. This data supports the hypothesis that with increased plywood density with only surface veneers densified will lead to significant screw withdrawal capacity improvement. Nonetheless, the screw withdrawal capacity of birch UN plywood remained highest together with black alder AVD plywood. Though, densified veneers significantly improved screw withdrawal load for aspen and black alder plywood compared to birch plywood.

We observed that surface hardness of the plywood was significantly influenced by the plywood face veneer layer density. The densities of the remaining plywood veneer layers did not show any significant contribution to surface hardness. On the contrary, having more densified layers in plywood significantly contributed to screw withdrawal capacity. This improvement can be attributed to the compressed fibers and compact structure of the densified wood, which enhance the connection between the screw threads and the wood. This effect becomes more pronounced with a higher number of densified layers in the plywood lay-up.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Tolgay Akkurt (T.A.) and Anti Rohumaa (A.R.).; methodology, T.A.; software, Heikko Kallakas (H.K.).; validation, T.A., A.R and H.K.; formal analysis, T.A and H.K.; investigation, T.A., Fred Mühls (F.M.) and Alexander Scharf (A.S.); resources, Jaan Kers (J.K.); data curation, F.M and T.A; writing—original draft preparation, H.K.; writing—review and editing, A.S., T.A and H.K.; visualization, H.K.; supervision, T.A.; project administration, J.K.; funding acquisition, H.K, A.R and J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Estonian Research Council grant (PRG2213) and Environmental Investment Center (RE.4.08.22-0012).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to the confidentiality of the running project.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Environmental Investment Center for supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kariz, M.; Kuzman, M.K.; Šernek, M. The Effect of Heat Treatment on the Withdrawal Capacity of Screws in Spruce Wood. Bioresources 2013, 8, 4340–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Peng, J.; Huang, Q.; Cai, L.; Shi, S.Q. Fabrication of Densified Wood via Synergy of Chemical Pretreatment, Hot-Pressing and Post Mechanical Fixation. Journal of Wood Science 2020, 66, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mania, P.; Wróblewski, M.; Wójciak, A.; Roszyk, E.; Moliński, W. Hardness of Densified Wood in Relation to Changed Chemical Composition. Forests 2020, 11, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelit, H.; Emiroglu, F. Density, Hardness and Strength Properties of Densified Fir and Aspen Woods Pretreated with Water Repellents. Holzforschung 2021, 75, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, J.P.; Kafle, B.; Subhani, M.; Reiner, J.; Ashraf, M. Densification of Timber: A Review on the Process, Material Properties, and Application. Journal of Wood Science 2022, 68, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.; Fang, C.H.; Ma, Y.F.; Fei, B.H. Wood Mechanical Densification: A Review on Processing. Materials and Manufacturing Processes 2022, 37, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvennoinen, R.V.J.; Palviainen, J.; Kellomaeki, S.; Peltola, H.; Sauvala, K. Detection of Wood Density by a Diffractive-Optics-Based Sensor. In Proceedings of the Other Conferences; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Aytekin, A. Determination of Screw and Nail Withdrawal Resistance of Some Important Wood Species. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2008, 9, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, S.; Wu, G.; Gong, Y.; Ren, H. Withdrawal Properties of Self-Tapping Screws in Japanese Larch (Larix Kaempferi (Lamb.) Carr.) Cross Laminated Timber. Forests 2021, 12, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaily, S.S.; Gopakumar, D.A.; Aprilia, N.A.S.; Rizal, S.; Paridah, M.T.; Khalil, H.P.S.A. Evaluation of Screw Pulling and Flexural Strength of Bamboo-Based Oil Palm Trunk Veneer Hybrid Biocomposites Intended for Furniture Applications. Bioresources 2019, 14, 8376–8390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.C. Residual Strength Estimation of Decayed Wood by Insect Damage through in Situ Screw Withdrawal Strength and Compression Parallel to the Grain Related to Density. Journal of the Korean Wood Science and Technology 2021, 49, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gašparík, M.; Barcík, Š.; Borůvka, V.; Holeček, T. Impact of Thermal Modification of Spruce Wood on Screw Direct Withdrawal Load Resistance. Bioresources 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclain, T. Design Axial Withdrawal Strength from Wood. I. Wood Screws and Lag Screw. For Prod J 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, W.; Hunt, J.F.; Tajvidi, M. Screw and Nail Withdrawal Strength and Water Soak Properties of Wet-Formed Cellulose Nanofibrils Bonded Particleboard. Bioresources 2017, 12, 7692–7710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, D.; Haller, P.; Navi, P. Thermo-Hydro and Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical Wood Processing: An Opportunity for Future Environmentally Friendly Wood Products. Wood Mater Sci Eng 2013, 8, 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mania, P.; Hartlieb, K.; Mruk, G.; Roszyk, E. Selected Properties of Densified Hornbeam and Paulownia Wood Plasticised in Ammonia Solution. Materials 2022, 15, 4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, C.; Tu, D.; Zhu, Z.; Li, K. Surface Densification of Poplar Solid Wood: Effects of the Process Parameters on the Density Profile and Hardness. Bioresources 14, 4814–4831.

- Neyses, B.; Rautkari, L.; Yamamoto, A.; Sandberg, D. Pre-Treatment with Sodium Silicate, Sodium Hydroxide, Ionic Liquids or Methacrylate Resin to Reduce the Set-Recovery and Increase the Hardness of Surface-Densified Scots Pine. IForest 2017, 10, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perçin, O.; Altunok, M. The Effects of Heat Treatment, Wood Species and Adhesive Types on Screw Withdrawal Strength of Laminated Veneer Lumbers. Kastamonu University Journal of Forestry Faculty 2019, 19, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.J.; Ahn, K.S.; Kang, S.G.; Oh, J.K. Prediction of Withdrawal Resistance for a Screw in Hybrid Cross-Laminated Timber. Journal of Wood Science 2020, 66, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, W.; Hunt, J.F.; Tajvidi, M. Screw and Nail Withdrawal Strength and Water Soak Properties of Wet-Formed Cellulose Nanofibrils Bonded Particleboard. Bioresources 2017, 12, 7692–7710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulker, O.; Imirzi, O.; Burdurlu, E. The Effect of Densification Temperature on Some Physical and Mechanical Properties of Scots Pine (Pinus Sylvestris L.). Bioresources 2012, 7, 5581–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhoushi, M.; Gray, M.; Tabarsa, T. Influence of Wood Densification on Withdrawal Strength of Fasteners in Eastern Cottonwood (Populus Deltoides). 11th World Conference on Timber Engineering 2010, WCTE 2010 2010, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Akkurt, T.; Kallakas, H.; Rohumaa, A.; Hunt, C.G.; Kers, J. Impact of Aspen and Black Alder Substitution in Birch Plywood. Forests 2022, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallakas, H.; Rohumaa, A.; Vahermets, H.; Kers, J. Effect of Different Hardwood Species and Lay-Up Schemes on the Mechanical Properties of Plywood. Forests 2020, Vol. 11, Page 649 2020, 11, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmén, L. Temperature and Water Induced Softening Behaviour of Wood Fiber Based Materials.; 1982.

- EVS-EN 323:2002 - EVS Standard Evs.Ee | En. 2002.

- EVS-EN 1534:2020 - EVS Standard Evs.Ee | En. 2020.

- EVS-EN 13446:2002 - EVS Standard Evs.Ee | En. 2002.

- Bekhta, P.; Pipíška, T.; Gryc, V.; Sedliačik, J.; Král, P.; Ráheľ, J.; Vaněrek, J. Properties of Plywood Panels Composed of Thermally Densified and Non-Densified Alder and Birch Veneers. Forests 2023, Vol. 14, Page 96 2023, 14, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhoushi, M.; Gray, M.; Tabarsa, T. Influence of Wood Densification on Withdrawal Strength of Fasteners in Eastern Cottonwood (Populus Deltoides). 11th World Conference on Timber Engineering 2010, WCTE 2010 2010, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, M.; Norimoto, M.; Tanahashi, M.; Rowel1, R.M. Steam or Heat Fixation of Compressed Wood. Wood and Fiber Science 1993, 224–235. [Google Scholar]

- Kamke, F.A. DENSIFIED RADIATA PINE FOR STRUCTURAL COMPOSITES. Maderas. Ciencia y tecnología 2006, 8, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navi, P.; Heger, F. Combined Densification and Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical Processing of Wood. MRS Bull 2004, 29, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.H.; Mariotti, N.; Cloutier, A.; Koubaa, A.; Blanchet, P. Densification of Wood Veneers by Compression Combined with Heat and Steam. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products 2012, 70, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemz, P.; Stübi, T. Investigations of Hardness Measurements on Wood Based Materials Using a New Universal Measurement System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the symposium on wood machining, properties of wood and wood composites related to wood machining; Vienna, Austria; p. 2000.

- Kontinen, P.; Nyman, C. Hardness of Wood-Based Panel Products and Their Coatings and Overlays. Paper Timber 1977, 9, 531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Rautkari, L.; Properzi, M.; Pichelin, F.; Hughes, M. Surface Modification of Wood Using Friction. Wood Sci Technol 2009, 43, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, A.; Neyses, B.; Sandberg, D. Hardness of Surface-Densified Wood. Part 1: Material or Product Property? Holzforschung 2022, 76, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, A.; Neyses, B.; Sandberg, D. Hardness of Surface-Densified Wood. Part 2: Prediction of the Density Profile by Hardness Measurements. Holzforschung 2022, 76, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautkari, L.; Kamke, F.A.; Hughes, M. Density Profile Relation to Hardness of Viscoelastic Thermal Compressed (VTC) Wood Composite. [CrossRef]

- Abukari, M.H. The Performance of Structural Screws in Canadian Glulam, McGill University: Montreal, 2012.

- Gutknecht, M.P.; Macdougall, C. Withdrawal Resistance of Structural Self-Tapping Screws Parallel-to-Grain in Common Canadian Timber Species. 2019; 46, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, S.; Kazemi Najafi, S.; Ebrahimi, G.; Ghofrani, M. Withdrawal Resistance of Screws in Structural Composite Lumber Made of Poplar (Populus Deltoides). Constr Build Mater 2017, 142, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes RIBEIRO, M.; Henrique Soares DEL MENEZZI, C.; Luiz SIQUEIRA, M.; Rodolfo de MELO, R. Effect of Wood Density and Screw Length on the Withdrawal Resistance of Tropical Wood. Nativa 2018, 6, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).