Submitted:

05 June 2024

Posted:

06 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

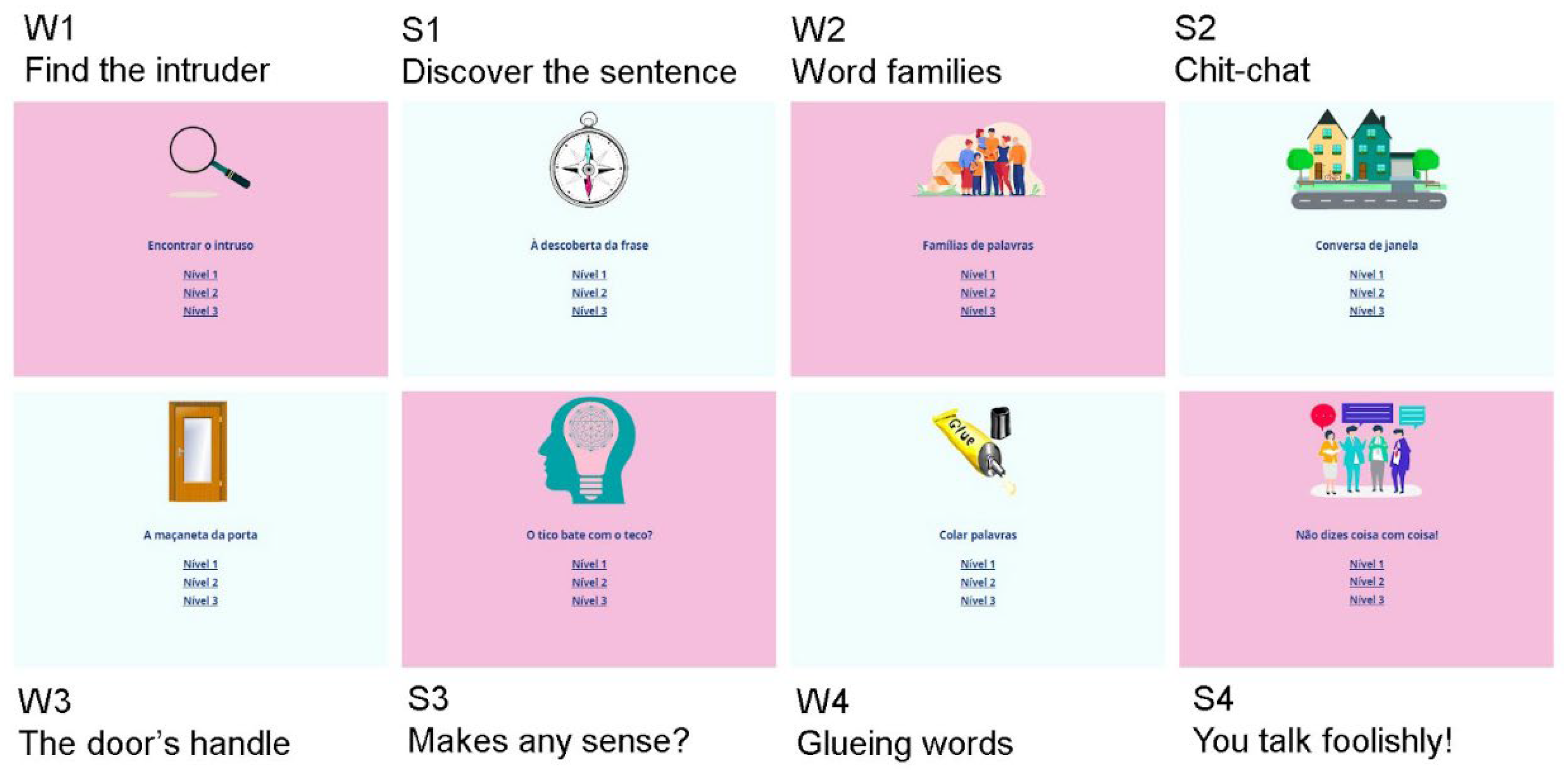

2.2. Materials

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Adherence and Engagement

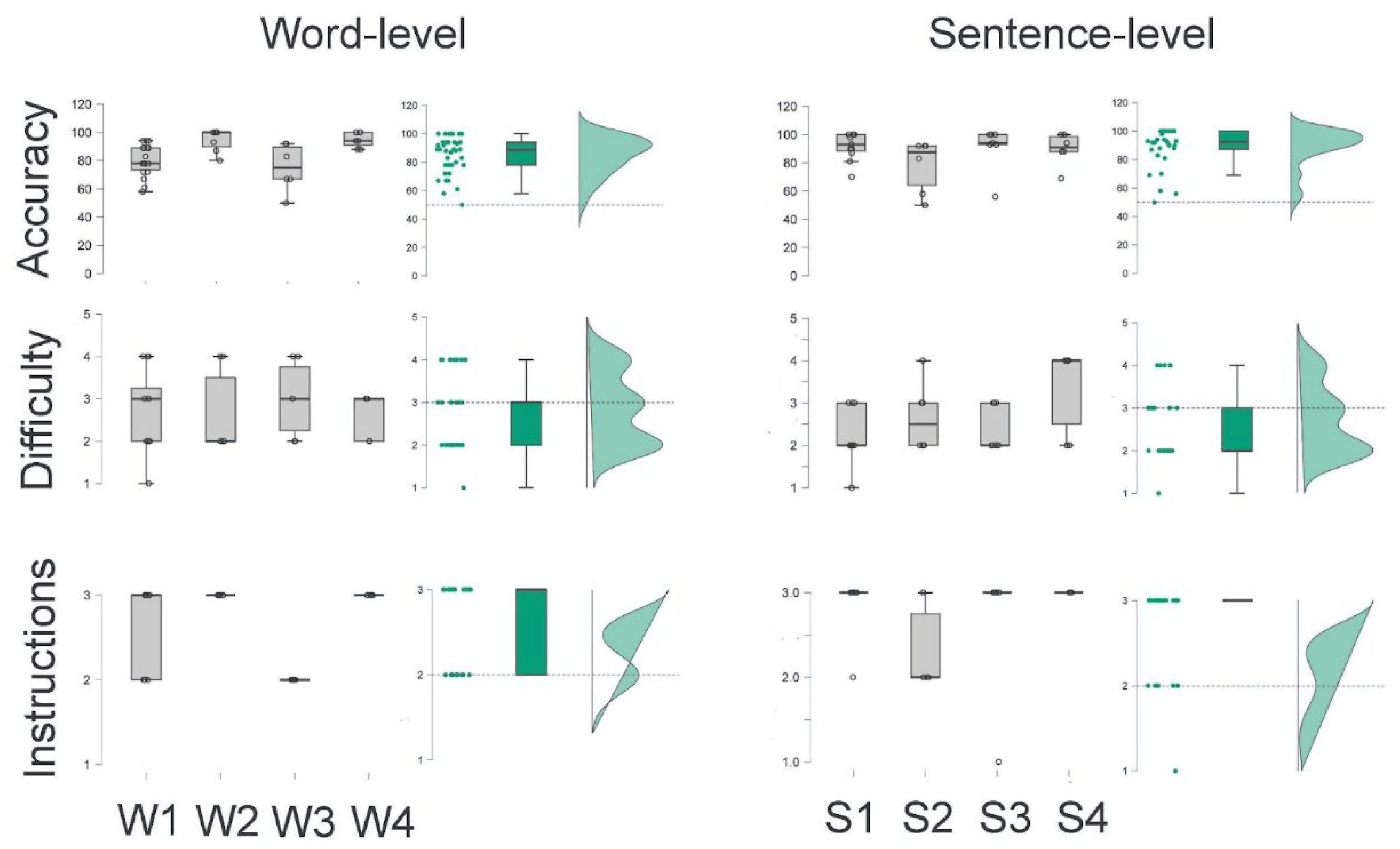

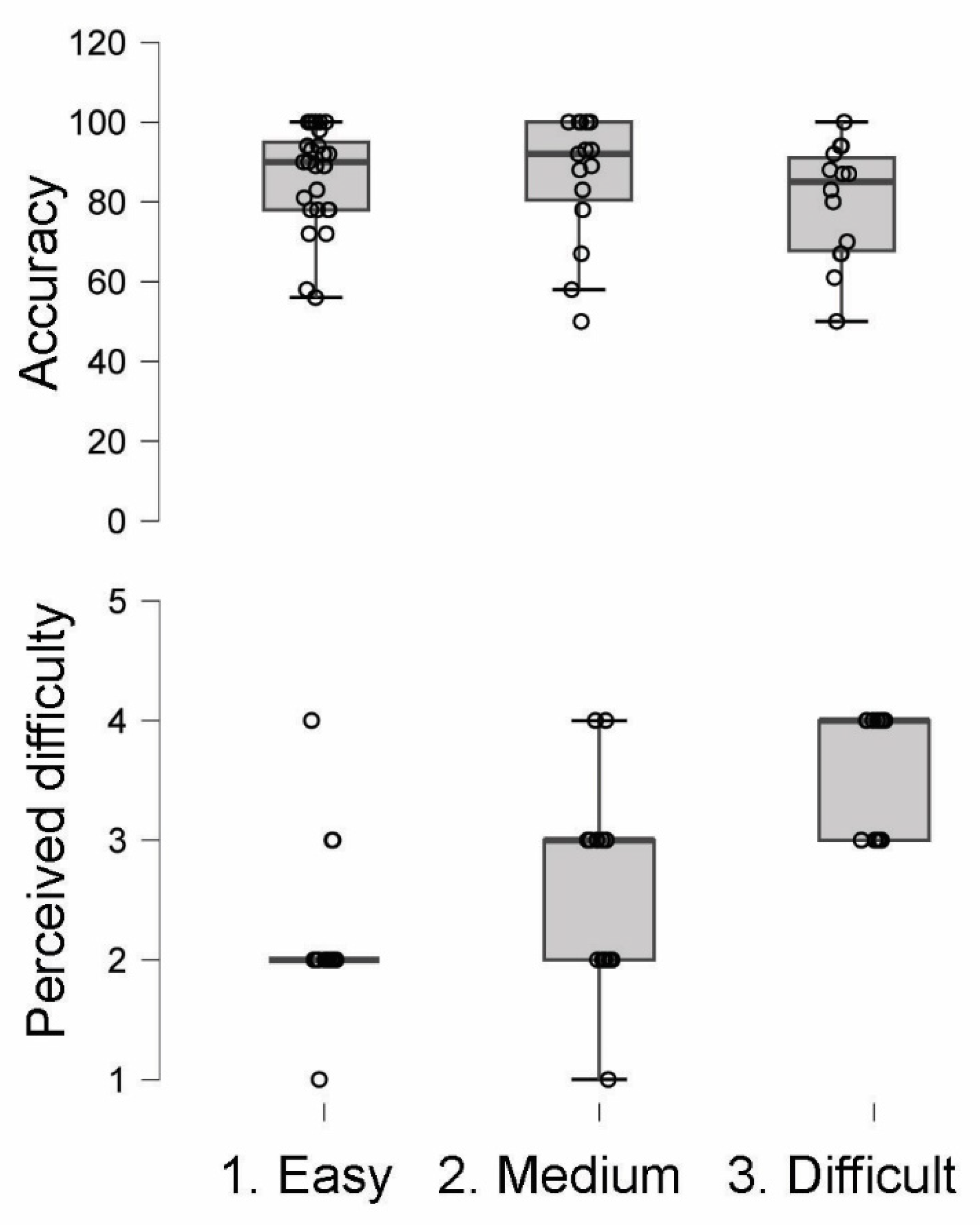

3.2. Performance Accuracy, Perceived Difficulty and Adequacy of Instructions

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bagha, K.N. A short introduction to semantics. JLTR 2011, 2, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeks, J.C.; Stowe, L.A.; Doedens, G. Seeing words in context: the interaction of lexical and sentence level information during reading. Cogn. Brain Res. 2004, 19, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroeger, P.R. Analyzing meaning: An introduction to semantics and pragmatics. Language Science Press, Berlin, 2018.

- Chaffin, R.; Herrmann, D. J.; Winston, M. An empirical taxonomy of part-whole relations: Effects of part-whole relation type on relation identification. Lang. Cognitive proc. 1988, 3, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruse, D.A. On the transitivity of the part-whole relation. J. Linguist. 1979, 15, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruse, D.A. (2000). Meaning in Language. An Introduction to Semantics and Pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (2000).

- Mikołajczak-Matyja, N. The associative structure of the mental lexicon: hierarchical semantic relations in the minds of blind and sighted language users. Psychol. Lang. Commun. 2015, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Deyne, S.; Verheyen, S.; Storms, G. (2016). Structure and Organization of the Mental Lexicon: A Network Approach Derived from Syntactic Dependency Relations and Word Associations. In Towards a Theoretical Framework for Analyzing Complex Linguistic Networks. Understanding Complex Systems, Mehler, A., Lücking, A., Banisch, S., Blanchard, P., Job, B., Eds.; Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2016; pp. 47–79. [CrossRef]

- Emmorey, K.D.; Fromkin, V.A. The mental lexicon. In Linguistics: The Cambridge Survey, Newmeyer, F.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1988; pp. 124–149.

- Jackendof, R. Lexical semantics. In The Oxford handbook of the mental lexicon, Papafragou, A.; Trueswell, J.C.; Gleitman, L.R.; Eds.; Oxford University Press, UK, 2022; pp. 125–150. [CrossRef]

- Caramazza, A. How many levels of processing are there in lexical access? Cogn. Neuropsychol. 1997, 14, 177–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levelt, W.J. Speaking: From intention to articulation. MIT press, Cambridge, UK, 1993.

- Andrews, S. Lexical retrieval and selection processes: Effects of transposed-letter confusability. J. Mem. Lang. 1996, 35, 775–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, H.; Grabowski, T.J.; Tranel, D.; Hichwa, R.D.; Damasio, A.R. A neural basis for lexical retrieval. Nature 1996, 380, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodglass, H. Stages of lexical retrieval. Aphasiology 1998, 12, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shebani, Z.; Patterson, K.; Nestor, P.J.; Diaz-de-Grenu, L.Z.; Dawson, K.; Pulvermüller, F. Semantic word category processing in semantic dementia and posterior cortical atrophy. Cortex 2017, 93, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraudie, A.; Battista, P.; García, A.M.; Allen, I.E. , Miller, Z.A.; Gorno-Tempini, M.L.; Montembeault, M. Speech and language impairments in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 131, 1076–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beales, A.; Whitworth, A.; Cartwright, J. A review of lexical retrieval intervention in primary progressive aphasia and Alzheimer’s disease: Mechanisms of change, generalisation, and cognition. Aphasiology 2018, 32, 1360–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairami, S.; Folia, V.; Liampas, I.; Ntanasi, E.; Patrikelis, P.; Siokas, V.; Yannakoulia, M.; Sakka, P.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.; Scarmeas, N.; Dardiotis, E.; Kosmidis, M.H. Exploring Verbal Fluency Strategies among Individuals with Normal Cognition, Amnestic and Non-Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Alzheimer’s Disease. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) 2023, 59, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liampas, I.; Folia, V.; Morfakidou, R.; Siokas, V.; Yannakoulia, M.; Sakka, P.; Scarmeas, N.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.; Dardiotis, E.; Kosmidis, M.H. Language Differences Among Individuals with Normal Cognition, Amnestic and Non-Amnestic MCI, and Alzheimer’s Disease. ACN 2023, 38, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, S.A.; Ballard, K.J.; Piguet, O.; Hodges, J. R. Bringing words back to mind–Improving word production in semantic dementia. Cortex 2013, 49, 1823–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senaha, M.L.H.; Brucki, S.M.D.; Nitrini, R. Rehabilitation in semantic dementia: Study of the effectiveness of lexical reacquisition in three patients. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2010, 4, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaPointe, L.L.; Stierwalt, J.A.G. Aphasia and related neurogenic language disorders, 5th ed, Thieme, New York, 2018.

- Vuković, M. Communication related quality of life in patients with different types of aphasia following a stroke: preliminary insights. Int. Arch. Commun. Disord. 2018, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, N.L.; Poon, L.W. Aging and retrieval of words in semantic memory. J. Gerontol. 1985, 40, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieder, M.; Crinelli, R.M.; Koenig, T.; Wahlund, L.O.; Dierks, T.; Wirth, M. Electrophysiological and behavioral correlates of stable automatic semantic retrieval in aging. Neuropsychologia 2012, 50, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, J.; Jolicoeur, P.; Grimault, S.; Pineault, J.; Joubert, S. Neural changes associated with semantic processing in healthy aging despite intact behavioral performance. Brain Lang. 2015, 149, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baciu, M.; Boudiaf, N.; Cousin, E.; Perrone-Bertolotti, M.; Pichat, C.; Fournet, N. . Krainik, A. Functional MRI evidence for the decline of word retrieval and generation during normal aging. Age 2016, 38, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, D.M.; Laver, G.D. 10 Aging and Word Retrieval: Selective Age Deficits in Language. Advances in psychology 1990, 72, 281–300. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, J.K.; Young, M.; Garcia, C. Why do older adults have difficulty with semantic fluency? Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2018, 25, 803–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortensen, A.; Meyer, A.S.; Humphreys, G.W. Age-related effects on speech production: A review. Lang. Cognitive Proc. 2006, 21, 238–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obler, L.K.; Fein, D.; Nicholas, M.; Albert, M.L. Auditory comprehension and aging: Decline in syntactic processing. Appl. Psycholinguist. 1991, 12, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickels, L. Evaluating lexical semantic therapy: BOXes, arrows and how to mend them. Aphasiology 1997, 11, 1083–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visch-Brink, E.G.; Bajema, I. M.; Sandt-Koenderman, M.V.D. Lexical semantic therapy: BOX. Aphasiology 1997, 11, 1057–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarin, F.S.; Branco, L.; Pereira, N.; Kochhann, R.; Gindri, G.; Fonseca, R.P. Rehabilitation of lexical and semantic communicative impairments: An overview of available approaches. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2014, 8, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, M.L.; Meese, M.V.; Truong, S.; Babiak, M.C.; Miller, B.L.; Gorno-Tempini, M.L. Treatment for apraxia of speech in nonfluent variant primary progressive aphasia. Behav. Neurol. 2013, 26, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelcic, N.; Cagnin, A.; Meneghello, F.; Turolla, A.; Ermani, M.; Dam, M. Effects of lexical–semantic treatment on memory in early Alzheimer disease: An observer-blinded randomized controlled trial. NNR 2012, 26, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelcic, N.; Agostini, M.; Meneghello, F.; Bussè, C.; Parise, S.; Galano, A.; Tonin, P.; Dam, M.; Cagnin, A. Feasibility and efficacy of cognitive telerehabilitation in early Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 1605–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, M.M.; Boland, J.E. Children’s use of language context in lexical ambiguity resolution. QJEP 2010, 63, 160–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiland, C.; Barata, M.C.; Yoshikawa, H. The co-occurring development of executive function skills and receptive vocabulary in preschool-aged children: a look at the direction of the developmental pathways. Infant child dev. 2014, 23, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneman, M.; Carpenter, P.A. Individual Differences in Working Memory and Reading. JVLBA 1980, 19, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slevc, L.R. Saying what’s on your mind: Working memory effects on sentence production. JEP: LMC 2011, 37, 1503–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederstrasser, N.G.; Hogervorst, E.; Giannouli, E.; Bandelow, S. Approaches to cognitive stimulation in the prevention of dementia. JGG 2016, 5, 005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardif, S.; Simard, M. Cognitive stimulation programs in healthy elderly: a review. IJADR 2011, 2011, 378934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peel, N.M.; Russell, T.G.; Gray, L.C. Feasibility of using an in-home video conferencing system in geriatric rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2011, 43, 364–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Ríos, R.; Mateos, R.; Lojo, D.; Conn, D. K.; Patterson, T. Telepsychogeriatrics: a new horizon in the care of mental health problems in the elderly. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 24, 1708–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousia, A.; Martzoukou, M.; Siokas, V.; Aretouli, E.; Aloizou, A.M.; Folia, V.; Peristeri, E.; Messinis, L.; Nasios, G.; Dardiotis, E. Beneficial effect of computer-based multidomain cognitive training in patients with mild cognitive impairment. App. Neuropsych-Adul. 2021, 28, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, J.R. Comments on ‘Lexical semantic therapy: BOX’: a consideration of the development and implementation of the treatment. Aphasiology 1997, 11, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, L. Theory of mind in utterance interpretation: The case from clinical pragmatics. Frontiers in Psychology 2015, 6, 148075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathôt, S.; Schreij, D.; Theeuwes, J. OpenSesame: An open-source, graphical experiment builder for the social sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2012, 44, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, K.; Kühn, S.; Filevich, E. “Just Another Tool for Online Studies” (JATOS): An easy solution for setup and management of web servers supporting online studies. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foos, P.W.; Boone, D. Adult age differences in divergent thinking: It’s just a matter of time. Educ. Gerontol. 2008, 34, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, S.A.; Altmann, L.J.P.; Abrams, L.; Gonzalez Rothi, L.J.; Heilman, K.M. Divergent task performance in older adults: Declarative memory or creative potential? Creat. Res. J. 2014, 26, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folia, V.; Liampas, I.; Ntanasi, E.; Yannakoulia, M.; Sakka, P.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.; Scarmeas, N.; Dardiotis, E.; Kosmidis, M.H. Longitudinal trajectories and normative language standards in older adults with normal cognitive status. Neuropsychology 2022, 36, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusi, G.; Lavolpe, S.; Crepaldi, M.; Rusconi, M.L. The controversial effect of age on divergent thinking abilities: A systematic review. J. Creat. Behav. 2021, 55, 374–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmiero, M. The effects of age on divergent thinking and creative objects production: A cross-sectional study. High Abil. Stud. 2015, 26, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, B.; Antonietti, A.; Daneau, B. The relationships between cognitive reserve and creativity. A study on American aging population. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmiero, M.; Di Giacomo, D.; Passafiume, D. Can creativity predict cognitive reserve? JCB 2016, 50, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folia, V.; Liampas, I.; Siokas, V.; Silva, S.; Ntanasi, E.; Yannakoulia, M.; Sakka, P.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.; Scarmeas, N.; Dardiotis, E.; Kosmidis, M.H. Language performance as a prognostic factor for developing Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome and mild cognitive impairment: Results from the population-based HELIAD cohort. JINS 2023, 29, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liampas, I.; Folia, V.; Zoupa, E.; Siokas, V.; Yannakoulia, M.; Sakka, P.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.; Scarmeas, N.; Dardiotis, E.; Kosmidis, M.H. Qualitative Verbal Fluency Components as Prognostic Factors for Developing Alzheimer’s Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment: Results from the Population-Based HELIAD Cohort. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) 2022, 58, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cera, R.; Cristini, C.; Antonietti, A. Conceptions of learning, well-being, and creativity in older adults. ECPS 2018, 18, 241–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Individuals (n = 14) | Collective (n = 13) | |

| Mean± SD, Min-Max | ||

| Age | 57.92 ± 24.35, 29–90 | 57.85 ± 11.88, 37–73 |

| Schooling | 10.50 ± 6.38, 4–18 | 7.60 ± 4.25, 4–16 |

| Percentage | ||

| Gender M F |

21.4 78.6 |

15,4 84.6 |

| Active Y N |

42,9 57.1 |

0 100 |

| W1 | W2 | W3 | W4 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | |

| Unit size | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Number of steps | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Additional processes (AP) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Uncertainty in AP | 1 | 0 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Sum | 5 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Completed blocks/ opened blocks (%) | ||||||||||

| Group | Level | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | |

| Individuals | 1 | 9.8 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 22.7 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | |

| 2 | 16.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| 3 | 33.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Average | 22.2 | 1.9 | ||||||||

| Collective | 1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| 2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| 3 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Number of blocks completed | ||||||||||

| Whole sample | 1 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 2 | |

| 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Sum | 38 | 30 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).