1. Introduction

In most cancer cells, the rate of cell proliferation is abnormally increased, often because of dysregulated cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity [

1,

2]. CDKs are enzymes essential for the concerted regulation of cyclin activities throughout the cell cycle and eventually for the progression of cell proliferation [

3]. Therefore, tumor suppression by the inhibition of abnormal CDK activity has emerged as a potential therapeutic strategy for various cancers.

Cyclin D1 determines the progression from the G1 phase to the S phase of the cell cycle, and CDK4/6 phosphorylates and activates cyclin D1 to regulate the cell cycle [

4]. CDK4/6 inhibitors block the formation of the CDK4/6–cyclin D1 protein complex, thereby halting cell division [

2]. Three CDK4/6 inhibitors, palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib, have been approved for the treatment of hormone receptor (HR)-positive, HER2-negative advanced, or metastatic breast cancers [

4,

5]. Among these inhibitors, abemaciclib has a broader spectrum of potential uses beyond breast cancer, and its ability to cross the blood–brain barrier and its efficacy in other cancer types are being explored in clinical trials, making it a relevant choice for various cancers [

6].

Despite the high therapeutic efficacy of CDK4/6 inhibitors, they exhibit various adverse effects. Although the risk of most side effects is low (grade 1 or 2), more severe effects (grade 3 or 4) such as gastrointestinal disturbances, neutropenia, and leukopenia, which can lead to infections, are frequently observed [

7]. Severe and potentially fatal interstitial lung disease has also been identified [

8]. Thus, either discontinuing the use of CDK4/6 inhibitors or reducing their dosage is necessary to mitigate adverse effects [

7,

9].

Several clinical trials have explored combination therapies using CDK4/6 inhibitors [

10]. For example, combination therapy with letrozole, an estrogen converting inhibitor or fulvestrant, an estrogen blocker, which are drugs used in hormonally positive (HR+) breast cancer treatment, has been tested with palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib [

11,

12,

13]. However, these combination therapies have limitations in terms of reducing adverse effects, thus highlighting the need to develop new combination therapies [

14].

Patients with cancer frequently experience depression because of pain associated with treatment, often necessitating antidepressant prescriptions that vary widely in dosage [

15,

16,

17]. Antidepressants have side effects, including insomnia, weight loss, dry mouth, and chest pain [

18]. However, unlike the high-risk side effects of CDK4/6 inhibitors, dangerous side effects are not commonly associated with antidepressants [

18]. Furthermore, recent studies investigating the survival rates of patients with cancer using antidepressants have shown that the use of antidepressants does not worsen survival rates. Moreover, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) significantly improve the survival rates of patients with lung cancer [

16].

Herein, we propose the use of a TCA, desipramine, as a combination drug to enhance the therapeutic outcomes of CDK4/6 inhibitors. We performed in vitro cytotoxicity tests using a combination of various concentrations of abemaciclib and desipramine. In addition, in vivo animal studies were conducted to evaluate the antitumor effect of the combination of abemaciclib and desipramine in a human colon cancer-bearing mouse tumor model. As a result, the combination treatment significantly reduced the tumor size compared with the control or single treatment without causing apparent toxicity to normal tissues. Our findings suggest that the combination of abemaciclib and desipramine could reduce side effects and enhance tumor suppression, thus presenting a promising therapeutic strategy.

2. Results

2.1. Combined Treatment of Abemaciclib with Desipramine in Various Cancer Cell Lines

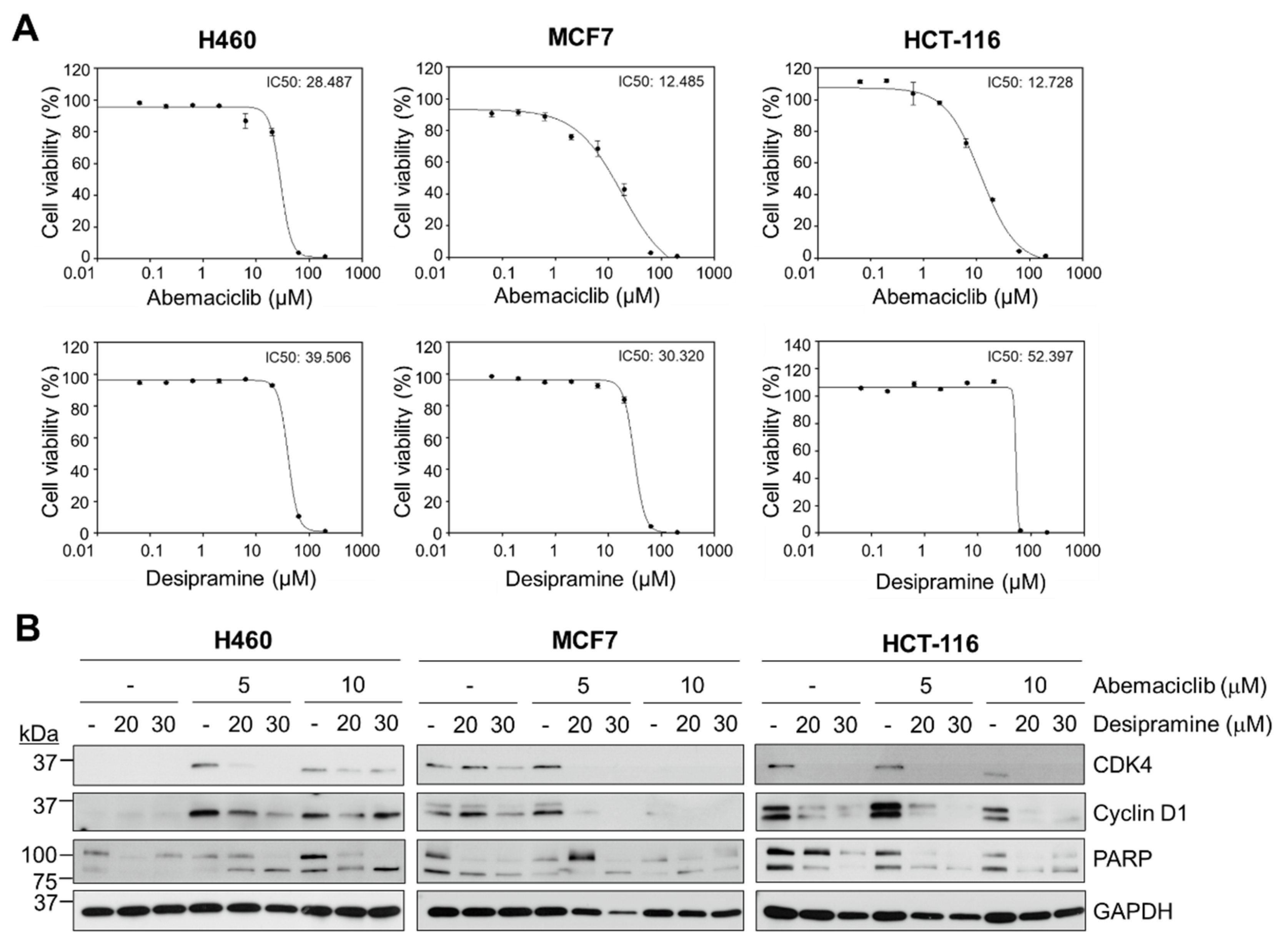

To determine the anticancer effects of abemaciclib and desipramine, a CellTiterGlo assay was performed to analyze cell viability by measuring adenosine triphosphate levels in the cells. Although the IC

50 of abemaciclib was similar between the breast cancer cell line MCF7 (HR

+, HER2

−) and the colon cancer cell line HCT-116 (12.5 vs. 12.7 µM), the NSCLC cell line, H460 cells, showed a more than two-fold higher IC

50 value (28.5 µM) than MCF7 or HCT-116 cells (

Figure 1A, upper row). The IC

50 values of desipramine were 39.5, 30.3, and 52.4 μM for H460, MCF7, and HCT-116 cancer cells, respectively (

Figure 1A, bottom row). MCF7 breast cancer cells and HCT-116 colon cancer cells were more sensitive to abemaciclib treatment than H460 cells, although most cell lines were relatively insensitive to desipramine in terms of cell viability.

Thus, we examined changes in proteins related to the cell death process (PARP) and cell cycle progression (CDK4 and cyclin D1) in these cell lines following treatment with abemaciclib, desipramine, or their combination. In H460 cells, CDK4 and cyclin D1 protein levels were not reduced by single-drug treatment with abemaciclib (5 or 10 μM). However, active PARP (cleaved form) was increased at higher abemaciclib levels (10 μM). Meanwhile, single-drug treatment with desipramine in H460 cells did not induce PARP cleavage even at 30 μM. In MCF7 cells, a higher abemaciclib concentration (10 μM) was effective in abolishing CDK4 and cyclin D1 proteins, although this was not effective in inducing PARP cleavage. In HCT-116 cells, a higher abemaciclib concentration (10 μM) was more effective in reducing CDK4 or cyclin D1 than a lower abemaciclib concentration (5 μM), although they were not completely abolished unlike MCF7 cells. However, desipramine treatment of HCT-116 cells dramatically reduced CDK4 and cyclin D1 levels, although PARP cleavage was not increased. Thus, desipramine is a putative drug that arrests cell cycle progression without inducing cell death.

Combining abemaciclib and desipramine enhanced PARP cleavage at a higher desipramine concentration (30 μM) in all three cell lines. However, this combination was not effective in reducing CDK4 and cyclin D1 levels in H460 cells but were only effective in such levels in HCT-116 cells. The effect on MCF7 cells was unclear because the effect of abemaciclib was dominant in reducing CDK4 and cyclin D1 levels. Thus, the combination treatment with the CDK4 inhibitors abemaciclib and desipramine was more prominent in HCT-116 cancer cells than in H460 or MCF7 cells (

Figure 1B). Based on these results, we evaluated the synergistic effects of abemaciclib and desipramine in HCT-116 cells.

2.2. Enhanced Effects of Abemaciclib and Desipramine Combination on Cell Cycle and Death

To evaluate the synergistic effect of abemaciclib and desipramine, we analyzed the viability of HCT-116 cells with combinations of four concentrations of abemaciclib (1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM) and three concentrations of desipramine (20, 30, and 40 μM). Hence, the maximum inhibitory effect on cell viability (95.8%) was observed with the combination of 10 μM abemaciclib and 40 μM desipramine (

Figure 2A). Meanwhile, when the synergistic effect of abemaciclib and desipramine was assessed, the highest synergistic effect (ZIP score: 17.35) was observed with the combination of 10 μM abemaciclib and 30 μM desipramine (

Figure 2B). Repeated CellTiterGlo assays (n = 3) confirmed the significant reduction of relative cell viability to 6.68% in abemaciclib (10 μM) and desipramine (30 μM) combination compared with a single drug with either 10 μM abemaciclib (55.46%,

p < 0.001) or 30 μM desipramine (98.45, N.S.) only (

Figure 2C).

To determine whether the combination treatment inhibited cellular proliferation, we analyzed cell cycles. Single treatment with abemaciclib increased the G1 population in HCT-116 cells as the concentration was increased from G1-23.5% at a negative control to 57.8% at 5 μM, and 53.0% at 10 μM. By contrast, a higher desipramine concentration did not increase the G1 population at 20 μM (22.0%) or 30 μM (27.0%). For the G2 population, abemaciclib decreased the G2 level from 26.9% at a negative control to 12.5% at 5 μM and to 17.2% at 10 μM. Desipramine also reduced the G2 population to 23.6% at 20 μM and to 18.7% at 30 μM. The S-phase population treated with abemaciclib reduced from 39.9% at a negative control to 19.5% at 5 μM and 16.3% at 10 μM, and single treatment with desipramine was not effective for S-phase reduction even at higher concentrations. However, we confirmed that the G1 arrest was increased to the highest level (58.8%) with the combination of abemaciclib (5 μM)/desipramine (30 μM), and G2 arrest was increased to the highest level at 27.4% with the abemaciclib (10 μM)/desipramine (30 μM) combination. Meanwhile, the S-phase level decreased to 11.3% with the abemaciclib (5 μM)/desipramine (30 μM) combination (

Figure 2D). Therefore, the combination of lower abemaciclib concentrations is sufficiently effective in inducing G1- and G2-phase arrests and depleting the S-phase.

To compare the effect of abemaciclib/desipramine combination treatment and single-drug treatment on cell death, we analyzed the changes in both early and late apoptotic populations by Annexin-V assay using flow cytometry. The single abemaciclib treatment increased frequency of early and late apoptotic population dose-dependently, from early (5.52%) and late (4.83%) apoptotic population of negative control HCT-116 cell to 13.1% of early and 11.4% of late apoptotic population at 10 μM. Unlike abemaciclib, desipramine did not dose-dependently increase the apoptotic population at 20 μM (3.39% of early and 1.86% of late apoptotic populations) and at 30 μM (5.04% of early and 2.68% of late apoptotic populations). However, applying those two drugs in combination significantly increased the apoptotic population (33.2% in total; 13.1% of early and 20.1% of late apoptotic populations) even at the lowest concentration of abemaciclib (5 μM)/desipramine (20 μM) combination. The highest level of overall cell death at 66.5% (28.6% of early and 37.9% of late apoptotic populations) was observed with the combination of higher abemaciclib (10 μM)/desipramine (30 μM) concentrations. However, the combination of lower abemaciclib (5 μM) with a higher concentration of desipramine (30 μM) also resulted in 49.9% of the apoptotic population (19.4% of early and 30.5% of late apoptotic populations) (

Figure 2E). Desipramine did not induce cell death by itself, even at higher doses; however, when used in combination with abemaciclib, it enhanced the potential cytotoxic effect of abemaciclib at lower concentrations, suggesting that abemaciclib can be used at a lower dose with minimal adverse effects when applied in combination with desipramine. This result provides a basis for assessing the effectiveness of the combined use of abemaciclib/desipramine

in vivo.

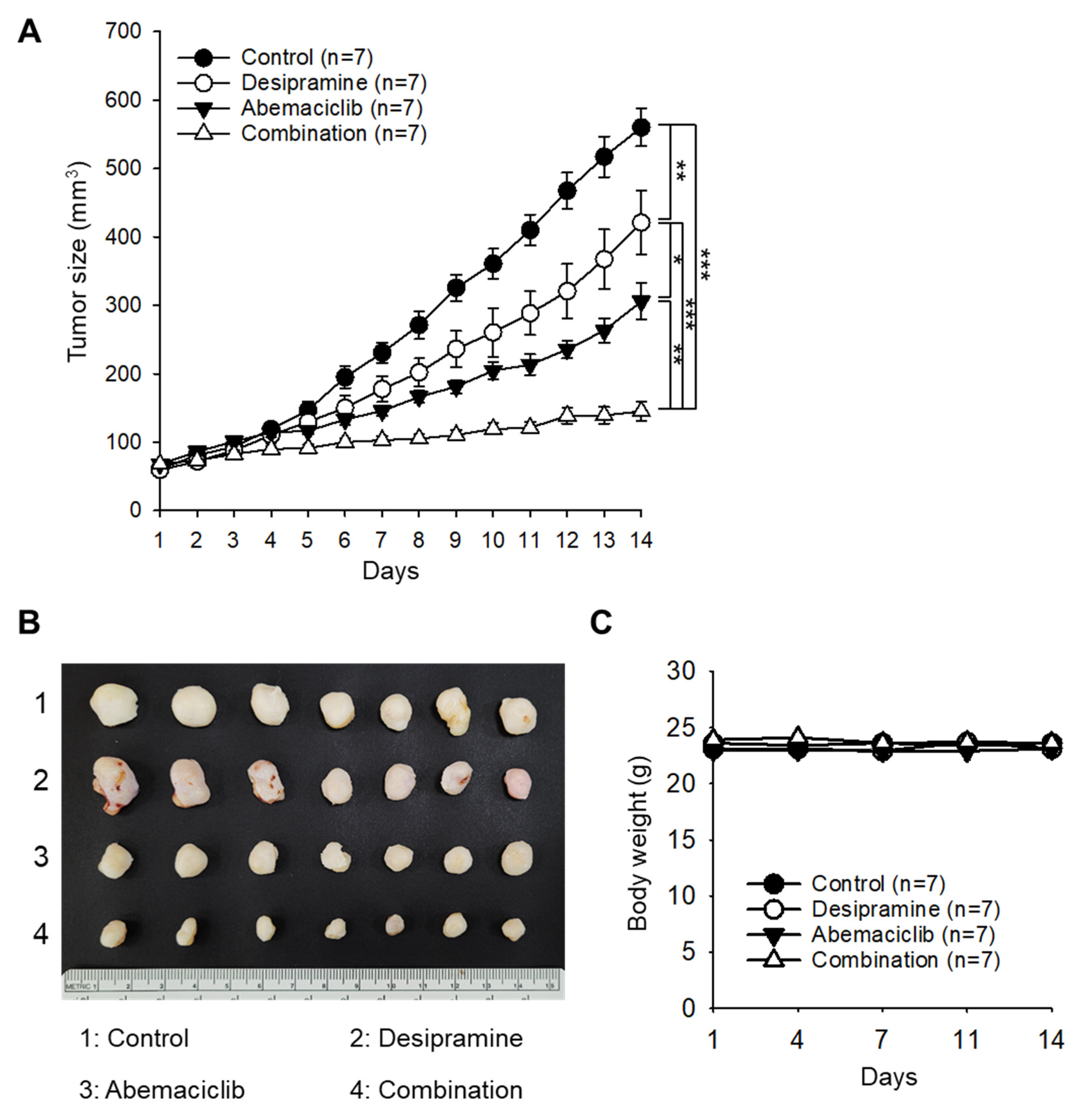

2.3. Antitumor Effects of Abamaciclib and Desipramine in an HCT-116 Xenograft Model

To evaluate the enhanced therapeutic effect of the combined treatment with abemaciclib and desipramine, a xenograft tumor model was constructed using the colorectal cancer cell line HCT-116. When the tumor size reached 60–70 mm

3, the drugs were administered once daily at 20 mg/kg (desipramine) and/or 30 mg/kg (abemaciclib). Tumor sizes of the desipramine- or abemaciclib-treated groups were 75.2% (

p < 0.01) and 54.6% (

p < 0.001) of the control group, respectively. Notably, tumor size in the combined treatment group significantly decreased to 25.9% (

p < 0.001) compared with that in the control group, confirming a significant synergistic antitumor effect (coefficient of drug interaction [CDI]=0.64) in the combined treatment group compared with the drug-alone treatment groups (

Figure 3A,B). The mice in the drug treatment groups did not show a significant difference in body weight compared with the control mice (

Figure 3C). In an additional set of experiment, we found that the anticancer effect of the combination treatment (desipramine 20 mg/kg + abemaciclib 30 mg/kg) was similar to that of high-dose abemaciclib (50 mg/kg) (

Figure S1). The combination of desipramine (20 mg/kg) and high-dose abemaciclib (50 mg/kg) did not induce an enhanced antitumor effect compared with either a high dose of abemaciclib (50 mg/kg) or combined treatment with a lower dose of abemaciclib (30 mg/kg).

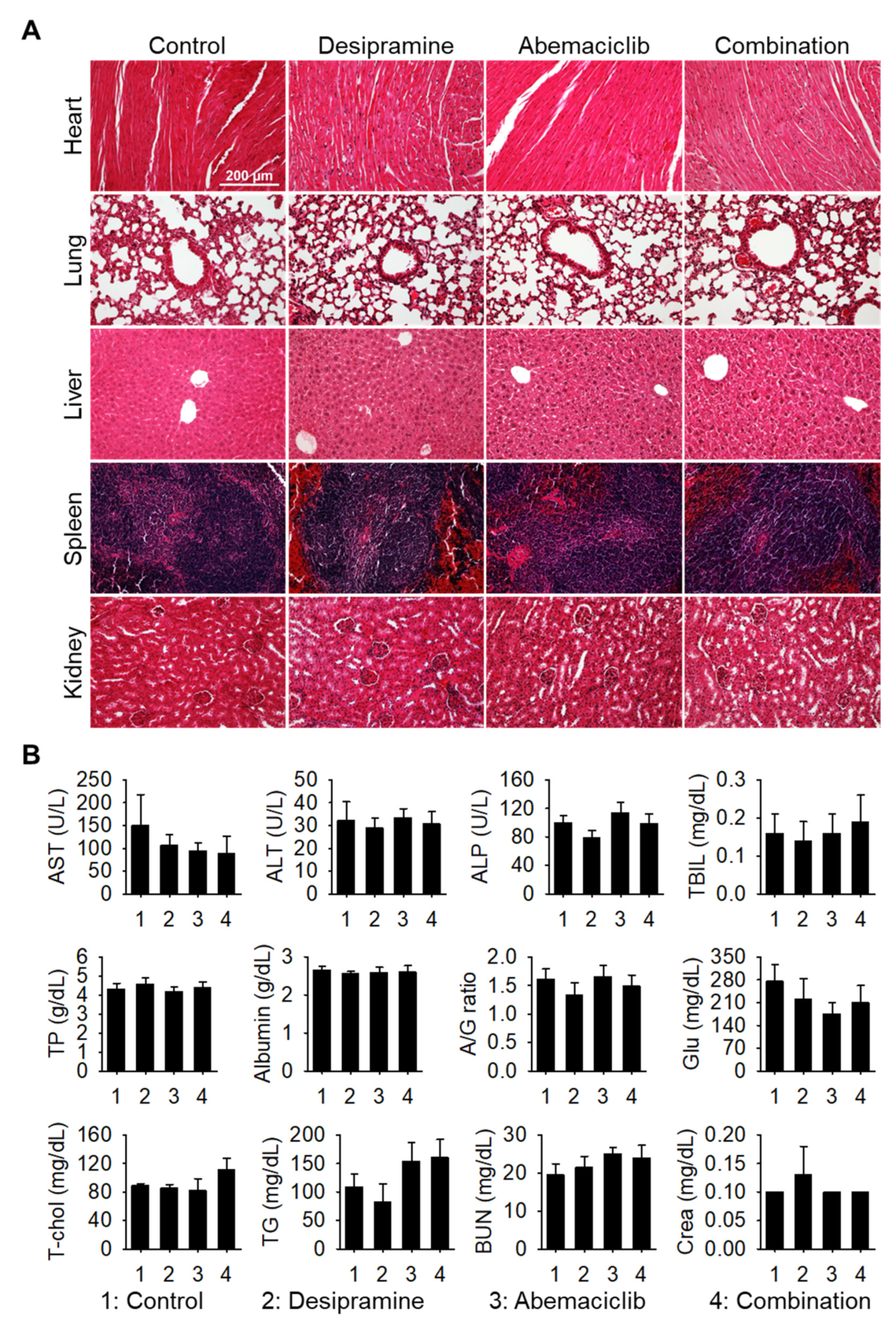

Next, we performed histopathological analysis of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections of the major organs (heart, lung, liver, spleen, and kidney). No histological changes were observed in the drug-treated groups compared with the vehicle-treated control group (

Figure 4A). In addition, no signs of side effects were observed in the blood chemical analysis (

Figure 4B), confirming that the combined dosage regimen used in this study is safe and provides synergistic antitumor effects against colon tumors.

Therefore, the combination therapy of CDK4/6 inhibitors with anti-depressants could be a novel therapeutic approach for solid tumors, such as colorectal, breast, and lung tumors.

3. Discussion

Assuming that cell cycle progression is hyperactive in almost all cancers, CDKs are crucial for the transition from the G1 to S phase of the cell cycle. Thus, CDK4/6 inhibitors have been recommended as promising targeted therapeutics for various cancers. The three main CDK4/6 inhibitors that are currently approved and widely studied are palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib. Each inhibitor has unique properties and varying degrees of relevance for different cancer types; however, their main indication remains HR(+)/HER2(−) breast cancer [

19]. Comparisons of their efficacy based on clinical trials revealed that abemaciclib showed broader potential relevance beyond breast cancer, including NSCLC and glioblastoma; however, in terms of objective response rate or progression-free survival, it is less compelling than breast cancer [

20]. This has led to extensive studies on the combination of various small-molecule drugs, including epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, BRAF or MEK inhibitors in melanoma [

21,

22], ALK inhibitors in neuroblastoma [

23], and immune checkpoint inhibitors [

24]. To utilize this combination therapy, large-scale clinical trials are required to evaluate the toxicity that causes serious side effects, even if the combination therapy is more efficient. Therefore, drugs that can overcome this obstacle and be safely used in combination with CDK4/6 inhibitors need to be identified.

Among the TCAs, desipramine possesses anticancer properties. Recent studies have explored the ability of various antidepressants, including desipramine, to modulate autophagy, a process involved in the degradation and recycling of cellular components that contribute to their anticancer effects. These antidepressants may trigger apoptosis, inhibit cellular energy metabolism, and exhibit other mechanisms that suppress tumor growth [

25]. Desipramine has been investigated as a potential treatment for lung cancer, specifically, small cell lung cancer (SCLC). A phase 2a clinical trial conducted at Stanford University explored the use of desipramine in patients with SCLC or other high-grade neuroendocrine tumors [

26].

In this study, desipramine treatment alone in HCT-116 cells reduced the protein levels of CDK4 and cyclin D1, although it did not activate the apoptotic protein PARP by cleavage (

Figure 1B) or did not increase the apoptotic cell population, even at higher concentrations (

Figure 2E). However, when combined with abemaciclib, the frequency of apoptosis dramatically increased to more than twice that of abemaciclib treatment alone (

Figure 2E). The arrest of cell cycle at G2 increased by 10% with the combination of desipramine and abemaciclib, regardless of abemaciclib dose difference. Therefore, the non-cytotoxicity of desipramine may be attributed to the huge increase in apoptotic cell frequency with a lower dose of abemaciclib, suggesting that this combination avoids adverse effects on non-cancerous cells by using low dose of abemaciclib.

These results were also verified in vivo by comparing tumor growth inhibition with drug treatment without toxicity to non-tumor organs or blood biochemistry. The combination of desipramine (20 mg/kg) and a lower dose of abemaciclib (30 mg/kg) resulted in a significantly synergistic antitumor effect when compared with treatment with each drug alone, whereas no adverse effect was observed in the combined treatment group. Interestingly, the combined treatment with desipramine and high-dose abemaciclib (50 mg/kg) did not induce further antitumor effects. This is in good agreement with the results obtained from the in vitro cell study, and suggests an optimal dose regimen for combination therapy.

Although combining CDK4/6 inhibitors with other targeted therapies can enhance the efficacy of cancer treatment, it also tends to increase the risk of adverse effects. This necessitates a careful and personalized approach to treatment, guided by ongoing research and clinical trials, to optimize therapeutic strategies. Our study on the combination of abemaciclib and desipramine may contribute to these efforts.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

H460, MCF7, and HCT-116 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collections (Manassas, VA, USA), and H460 and MCF7 were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (#10-040-CV; Corning, New York, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (#35-010-CV; Corning) and 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin antibiotic cocktail (#15240062; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), whereas HCT-116 was cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C and 5% CO2. All cells were sub-cultured at 80%–90% confluence twice weekly, detached with TrypLE Express solution (#25200072, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to minimize the damage to the cells, and maintained in the absence of mycoplasma contamination.

4.2. Cell Viability Assay

To measure the effects of desipramine hydrochloride (#D3900; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and abemaciclib (#S5746; Selleckchem, Houston, TX, USA) in vitro, H460, MCF7, and HCT-116 cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 103 cells/well in 96-well white optical plates (#3903; Corning, New York, USA), and then treated with 8-point serial half log dilutions of desipramine (~200 μM) or abemaciclib (~200 μM) from the next day for 72 h. Cell viability was measured using CellTiter-Glo (#G9241; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol on a Synergy HTX multimode plate reader (Agilent BioTek, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and normalized to that of the negative control. IC50 for each drug and cell line were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (ver. 9).

4.3. Combinatorial Cytotoxicity Assay

To evaluate the combinatorial effects of abemaciclib and desipramine, HCT-116 cell was selected, and combined compounds of abemaciclib (0–10 μM) and desipramine (0–30 μM) were treated for 72 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO

2 incubator. Cell viability was measured as described above and synergistic scores (ZIP) were calculated using the SynergyFinder 3.0 software (version 3.0) [

27].

4.4. Immunoblotting

Protein concentrations were measured using a bicinchoninic acid kit (#23225; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Primary antibodies against PARP (#9542S; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), CDK4 (#12790S; CST), Cyclin D1 (#2978S; CST), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (#sc-25778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were added and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies specific to the primary antibodies were used to detect proteins using a chemiluminescence kit (#34577; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

4.5. Cell Cycle Analysis and Apoptosis Assay Using Flow Cytometry

Compound treated cells, including a dimethylsulfoxide control, were prepared fixed in cold 70% ethanol for 16 h at 4 °C in 300 μl of FxCycle™ propidium iodide/RNase staining solution (#F10797; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Invitrogen), and then transferred into a 5-ml round bottom polystyrene tube with a cell-strainer cap (#352235; Corning, Falcon, México, S.A de C.V) after incubation for 30 min at room temperature. The cell cycle was analyzed using a FACSLyric™ Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

To measure apoptotic populations, whole cells, including adherent and floating cells, were collected using the FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (#556547; BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, HCT-116 (1.5 × 105) cells were treated with combination of abemaciclib (10 μM) and desipramine (20 or 30 μM) for 72 h in a 6-well plate. Harvested cells were stained for 15 min at room temperature in the dark, and the stained cells were analyzed using the FACSLyric™ Flow Cytometer. All flow cytometry data were analyzed using the FlowJo software (version 10).

4.6. Xenograft Tumor Model

HCT-116 cancer cells were implanted subcutaneously into BABL/c nude the mice (CAnN.CgFoxn1nu/CrljOri; Orient Bio, Seoul, Republic of Korea) at 5 × 10

6 cells/100 μl, and tumors. When the tumor size reached 60–70 mm

3, the mice were randomly divided into four groups as follows: control (n = 7), desipramine alone (n = 7), abemaciclib alone (n = 7), and desipramine and abemaciclib combination (n = 7). Desipramine (20 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally, whereas abemaciclib was administered orally at a dose of 30 mg/kg. Desipramine and abemaciclib were administered once daily until the end of the study period. The vehicle was administered to mice in the control group. Tumor size was measured every day until day 14 after treatment, and the differences between the groups were analyzed. Tumor size was calculated as follows: tumor volume (mm

3) = 1/2 × length (mm) × width (mm) × height (mm). The body weights of the mice were measured periodically. The in vivo synergistic effect of the combined treatment was determined by calculating the CDI [

28]. CDI values of <1 and <0.7 indicate synergy and significant synergy, respectively. The clinically recommended dose range for desipramine is 50–300 mg per day [

29]. Desipramine was administered to the mice at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day to evaluate its antidepressant effect [

30]. We also tested this drug at the same dose in an antitumor study.

To evaluate the in vivo toxicity of the drugs, major organs (heart, lung, liver, spleen, and kidney) were collected on day 14, sectioned, and stained with H&E. Blood samples were collected from mice for serum biochemical analysis.

5. Conclusions

Combined treatment with abemaciclib and desipramine induces a significantly synergistic outcome in colon cancer therapy without any apparent side effects. Combination therapy with CDK4/6 inhibitors and anti-depressants could be a novel therapeutic approach for solid tumors such as colorectal, breast, and lung cancers.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C. and S.-H.G.; validation, Y.L., Y.S. and Y.E.C.; investigation, Y.L., Y.S. and Y.E.C.; data curation, Y.L. and Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and Y.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.C. and S.-H.G.; supervision, Y.C. and S.-H.G.; funding acquisition, Y.C. and S.-H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Cancer Center grant (2310550), Republic of Korea.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (approval no. NCC-24-1036).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Some data may not be made available because of privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Cancer Center grant (2310550), Republic of Korea.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Strupp, C.; Corvaro, M.; Cohen, S.M.; Corton, J.C.; Ogawa, K.; Richert, L.; Jacobs, M.N. Increased cell proliferation as a key event in chemical carcinogenesis: Application in an integrated approach for the testing and assessment of non-genotoxic carcinogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tripathy, D.; Bardia, A.; Sellers, W.R. Ribociclib (LEE011): Mechanism of action and clinical impact of this selective cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor in various solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 3251–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baker, S.J.; Reddy, E.P. CDK4: A key player in the cell cycle, development, and cancer. Genes Cancer. 2012, 3, 658–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shapiro, G.I. Cyclin-dependent kinase pathways as targets for cancer treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 1770–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobhani, N.; D’Angelo, A.; Pittacolo, M.; Roviello, G.; Miccoli, A.; Corona, SP.; Bernocchi, O.; Generali, D.; Otto, T. Updates on the CDK4/6 inhibitory strategy and combinations in breast cancer. Cells. 2019, 8, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Patnaik, A.; Rosen, L.S.; Tolaney, S.M.; Tolcher, A.W.; Goldman, J.W.; Gandhi, L.; Papadopoulos, K.P.; Beeram, M.; Rasco, D.W.; Hilton, J.F.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Abemaciclib, an Inhibitor of CDK4 and CDK6, for Patients with Breast Cancer, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, and Other Solid Tumors. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 740–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hortobagyi, G.N.; Stemmer, S.M.; Burris, H.A.; Yap, Y.S.; Sonke, G.S.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Campone, M.; Blackwell, K.L.; André, F.; Winer, E.P.; et al. Ribociclib as first-line therapy for HR-positive, advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1738–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. FDA warns about rare but severe lung inflammation with Ibrance, Kisqali, and Verzenio for breast cancer. www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-warns-about-rare-severe-lung-inflammation-ibrance-kisqali-and-verzenio-breast-cancer. 9-13-2019.

- Stanciu, I.M.; Parosanu, A.I.; Nitipir, C. An Overview of the safety profile and clinical impact of CDK4/6 inhibitors in breast cancer-A systematic review of randomized phase II and III clinical trials. Biomolecules. 2023, 13, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ettl, J. Management of adverse events due to cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors. Breast Care (Basel). 2019, 14, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Finn, R.S.; Crown, J.P.; Lang, I.; Boer, K.; Bondarenko, I.M.; Kulyk, S.O.; Ettl, J.; Patel, R.; Pinter, T.; Schmidt, M.; et al. The cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in combination with letrozole versus letrozole alone as first-line treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1/TRIO-18): a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slamon, D.J.; Neven, P.; Chia, S.; Fasching, P.A.; De Laurentiis, M.; Im, S.A.; Petrakova, K.; Bianchi, G.V.; Esteva, F.J.; Martín, M.; et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus fulvestrant in advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sledge, G.W. Jr.; Toi, M.; Neven, P.; Sohn, J.; Inoue, K.; Pivot, X.; Burdaeva, O.; Okera, M.; Masuda, N.; Kaufman, P.A.; et al. MONARCH 2: Abemaciclib in combination with fulvestrant in women with HR+/HER2- advanced breast cancer who had progressed while receiving endocrine therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2875–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thill, M.; Schmidt, M. Management of adverse events during cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitor-based treatment in breast cancer. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2018, 10, 1758835918793326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zingone, A.; Brown, D.; Bowman, ED.; Vidal, O.; Sage, J.; Neal, J.; Ryan, BM. Relationship between anti-depressant use and lung cancer survival. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2017, 10, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, E.; Park, Y.; Li, D.; Rodriguez-Fuguet, A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.C. Antidepressant use and lung cancer risk and survival: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Res. Commun. 2023, 3, 1013–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, K.L.; Chen, Y.L.; Stewart, R.; Chen, VC. Antidepressant use and mortality among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. JAMA Netw. Open. 2023, 6, e2332579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Riediger, C.; Schuster, T.; Barlinn, K.; Maier, S.; Weitz, J.; Siepmann, T. Adverse Effects of antidepressants for chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Ji, Z.; Chen, L.; Zou, J.; Zheng, J.; Lin, W.; Cai, J.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, D.; et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of different combinations of three CDK4/6 inhibitors with endocrine therapies in HR+/HER-2 - metastatic or advanced breast cancer patients: a network meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2023, 23, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Du, Q.; Guo, X.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, Q. The application and prospect of CDK4/6 inhibitors in malignant solid tumors. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, S.H.; Gong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Van Horn, R.D.; Yin, T.; Huber, L.; Burke, T.F.; Manro, J.; Iversen, P.W.; Wu, W.; et al. RAF inhibitor LY3009120 sensitizes RAS or BRAF mutant cancer to CDK4/6 inhibition by abemaciclib via superior inhibition of phospho-RB and suppression of cyclin D1. Oncogene. 2018, 37, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teh, J.L.F.; Cheng, P.F.; Purwin, T.J.; Nikbakht, N.; Patel, P.; Chervoneva, I.; Ertel, A.; Fortina, P.M.; Kleiber, I.; HooKim, K.; et al. In Vivo E2F Reporting Reveals Efficacious Schedules of MEK1/2-CDK4/6 Targeting and mTOR-S6 Resistance Mechanisms. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wood, A.C.; Krytska, K.; Ryles, H.T.; Infarinato, N.R.; Sano, R.; Hansel, T.D.; Hart, L.S.; King, F.J.; Smith, T.R.; Ainscow, E.; et al. Dual ALK and CDK4/6 Inhibition Demonstrates Synergy against Neuroblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 2856–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, J.; Bu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Geng, Y.; Nihira, N.T.; Tan, Y.; Ci, Y.; Wu, F.; Dai, X.; et al. Cyclin D-CDK4 kinase destabilizes PD-L1 via cullin 3-SPOP to control cancer immune surveillance. Nature. 2018, 553, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He, L.; Fu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, X.; Ding, R.-B.; Qi, X.; Bao, J. Antidepressants as Autophagy Modulators for Cancer Therapy. Molecules 2023, 28, 7594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riess, J.W.; Jahchan, N.S.; Das, M.; Zach Koontz, M.; Kunz, P.L.; Wakelee, H.A.; Schatzberg, A.; Sage, J.; Neal, J.W. A phase IIa study repositioning desipramine in small cell lung cancer and other high-grade neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2020, 23, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ianevski, A.; Giri, A.K.; Aittokallio, T. SynergyFinder 3.0: an interactive analysis and consensus interpretation of multi-drug synergies across multiple samples. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W739–W743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, M.; Choi, Y.E. , Yan, L.; Goh, S.-H.; Choi, Y. FOXM1 inhibitor-loaded nanoliposomes for enhanced immunotherapy against cancer. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amitai, Y.; Frischer, H. The toxicity and dose of desipramine hydrochloride. JAMA. 1994, 272, 1719–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yau, J.L.; Noble, J.; Thomas, S.; Kerwin, R.; Morgan, P.E.; Lightman, S.; Seckl, J.R.; Pariante, C.M. The antidepressant desipramine requires the ABCB1 (Mdr1)-type p-glycoprotein to upregulate the glucocorticoid receptor in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007, 32, 2520–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).