1. Introduction

Recent advancements in wound healing technologies have underscored the potential of Concurrent Optical and Magnetic Stimulation (COMS) as a promising therapeutic modality for hard-to-heal wounds [

1]. COMS has been shown to improve tissue perfusion and promote immunomodulation, thereby contributing to the healing process [

2]. In the context of chronic wounds, diminished tissue perfusion and suppressed cellular respiration are major factors contributing to sustained inflammation that impairs the healing process. The COMS modality was devised with the aim of better promoting wound healing by improving cell proliferation, migration, vasodilation, and angiogenesis.

Extracellular Ca

2+ entry and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are the two most common responses observed across a broad range of electromagnetic stimulation paradigms [

3]. In particular, the transient receptor potential canonical type 1 (TRPC1) cation channel has been implicated in the calcium response responses to electromagnetic field stimulation in muscle [

4], neurons [

5,

6] and diverse other tissues [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Potentially uniting these two electromagnetic response limbs is evidence of a TRPC1-mitochondrial axis [

4,

11] that has been implicated in myoblast proliferation enhancement following electromagnetic exposure. Of importance, the aminoglycoside antibiotics, commonly used in tissue culture and regenerative medicine paradigms, have been shown to impede Ca

2+ permeation through TRPC1, potentially precluding the ability of TRPC1 to transduce magnetic stimulation into regenerative cellular responses.

This study sought to validate the demonstrated regenerative efficacy of COMS in a published in vitro myogenic regenerative model [

4]. This study further aimed to examine the effect of the aminoglycoside antibiotics over COMS cellular responses. Lastly, we aimed to reveal the potential basis for functional synergism between the distinct excitation modes employed by the COMS for improved mechanistic understanding of its mode of action.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell studies and analysis

Cell culture and pharmacology

C2C12 mouse skeletal myoblasts were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; LGC Standards, Teddington, United Kingdom) and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Biowest, Nuaille, France), sodium pyruvate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and L-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and maintained in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Cells were passaged every 48 h to maintain them below 40% confluence, unless otherwise explicitly stated. Myoblasts were seeded into tissue culture dishes/flasks at 3,000 cells/cm2, unless otherwise explicitly stated. Twenty-four hours later the plates were exposed to optical and magnetic stimulation interventions (COMS). Cell number in each well was determined using enzymatic dissociation with TrypLE Express Enzyme (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), followed by the standard trypan blue exclusion method, and counted with a hemocytometer.

Streptomycin Treatments

Streptomycin (100 mg/L; Merck, Germany) was added directly to the cell culture media 15 min before or after exposure to the distinct paradigms. Cells were allowed to grow for another 24 h following exposure, prior to cell analysis.

Western Blot Analysis of Whole Cell Lysates

Protein extraction was performed using RIPA lysis buffer containing 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.05% SDS, EDTA-free 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (Nacalai Tesque Inc., Japan), 1X PhosSTOPTM phosphatase inhibitor (Merck, Germany) and 0.1% sodium deoxycholate (Merck, Germany). Whole-cell lysates were collected using a cell scraper and incubated at 4°C for 30 min before being spun at 3,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Whole-cell lysates were prepared in 4X Laemmli buffer with added β-mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad Laboratories and Sigma Life Science, USA, respectively) and were boiled at 98°C for 5 min. 20–25 µg of proteins from the whole-cell lysates were resolved using denaturing and reducing SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The antibodies and dilution factors used are listed in

Table 1.

Reactive Oxygen Species Measurements

For the determination of ROS cells were seeded in black-walled clear bottom 96-well plates (Costar) at a density of 5,000 cells per well with 8 replicates per condition. 24 h post-seeding, the cells were rinsed twice with Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) and incubated with 5 µM of CM-H2DCFDA (Invitrogen) in warm phenol-free and FBS-free FluoroBrite DMEM (GIBCO) for 30 min. The media containing CM-H2DCFDA was washed out using FluoroBrite DMEM twice before proceeding to expose the individual 96-well plates to COMS for 5 min in the standard culture incubator. ROS measurement was performed using a Cytation 5 microplate reader (BioTek) at Ex/EM: 492/525 nm for 15 readings up to 17 min.

ATP Detection

C2C12 myoblasts were seeded into clear 96-well plates at a density of 5,000 cells per well with 3 replicates per condition and exposed to the distinct interventions of sham (non-treated), light, magnetic fields and COMS for 5 min after 24 h of growth. Cells were then harvested using Cayman Chemical ATP Detection Assay Kit—Luminescence (700410; Ann Arbor, MI, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The collected lysates were diluted 30 times in 1 X ATP Sample Buffer before loading each biological replicate into 2 technical replicates each into a white opaque 96-well plate. The ATP concentration was determined by luminescence reading using Cytation 5 microplate reader (BioTek).

Statistical Analyses

All statistics were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (Version 10.2.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the values between two or more groups supported by multiple comparisons. This was followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. A two-tailed t-test was used for comparisons between the mean of two independent samples.

2.2. Device

The therapy device utilized in this study was the COMS One, manufactured by Piomic Medical AG, Zürich, Switzerland. This device is a Class IIa medical device, CE-certified for the stimulation of chronic leg and foot ulcers, which incorporates the technology for concurrent optical and magnetic stimulation.

Optical Stimulation Component: The COMS One features an optical stimulation system equipped with two types of light-emitting diodes (LEDs). These LEDs emit light at wavelengths of 660 nm (far-red) and 830 nm (near-infrared). The optical signals are pulsed at a frequency of 1 kHz with a maximum pulse width of 0.3 ms, delivering a peak pulse power of 25 mW/cm² and an average power output of 5 mW/cm² at the treatment area. The COMS device in operation is shown in Supplementary

Figure 1.

Magnetic Stimulation Component: Magnetic stimulation is provided by a coil within the device that produces pulsed modulated electromagnetic fields within the extremely low frequency (ELF) range of the electromagnetic spectrum. The emitted signal has an asymmetrical trapezoidal waveform at a frequency of 20 Hz. The peak field strength incrementally increases to 1.6 mT (16 Gauss), and treatments are administered over a 16-minute session at the specified treatment location.

Experimental Setup: Three variations of the COMS One device were employed during the experiments:

An optically-functional model where the magnetic stimulation component was deactivated.

A magnetically-functional model with the optical stimulation turned off.

A fully-functional unit, operating as per the manufacturer’s specifications.

These configurations allowed for the assessment of the individual and combined effects of the optical and magnetic components.

3. Results

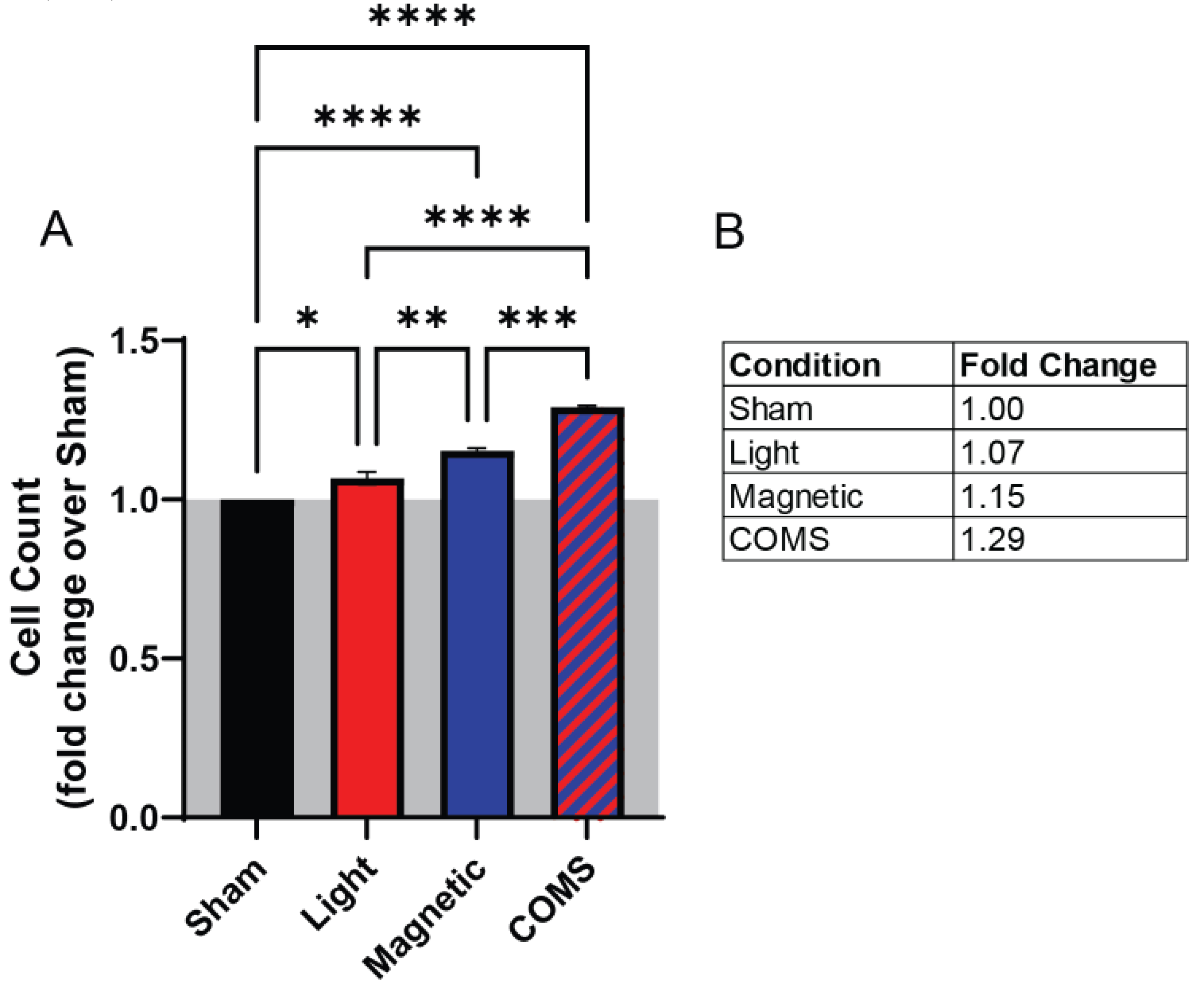

The proliferative effects of the separate and combined COMS modalities were examined in an established magnetoreceptive in vitro myogenesis system [

4]. Exposure to light (red) and magnetic fields (blue) separately enhanced cell proliferation by 7% and 15%, respectively, relative to sham (black) (

Figure 1). Exposure to combined light and magnetic fields (COMS modality; hatched blue/red) produced an increase in cell proliferation of 29%, which represented significant increases over light and magnetic fields individually. These results suggest that light and magnetic fields act synergistically to promote cell proliferation.

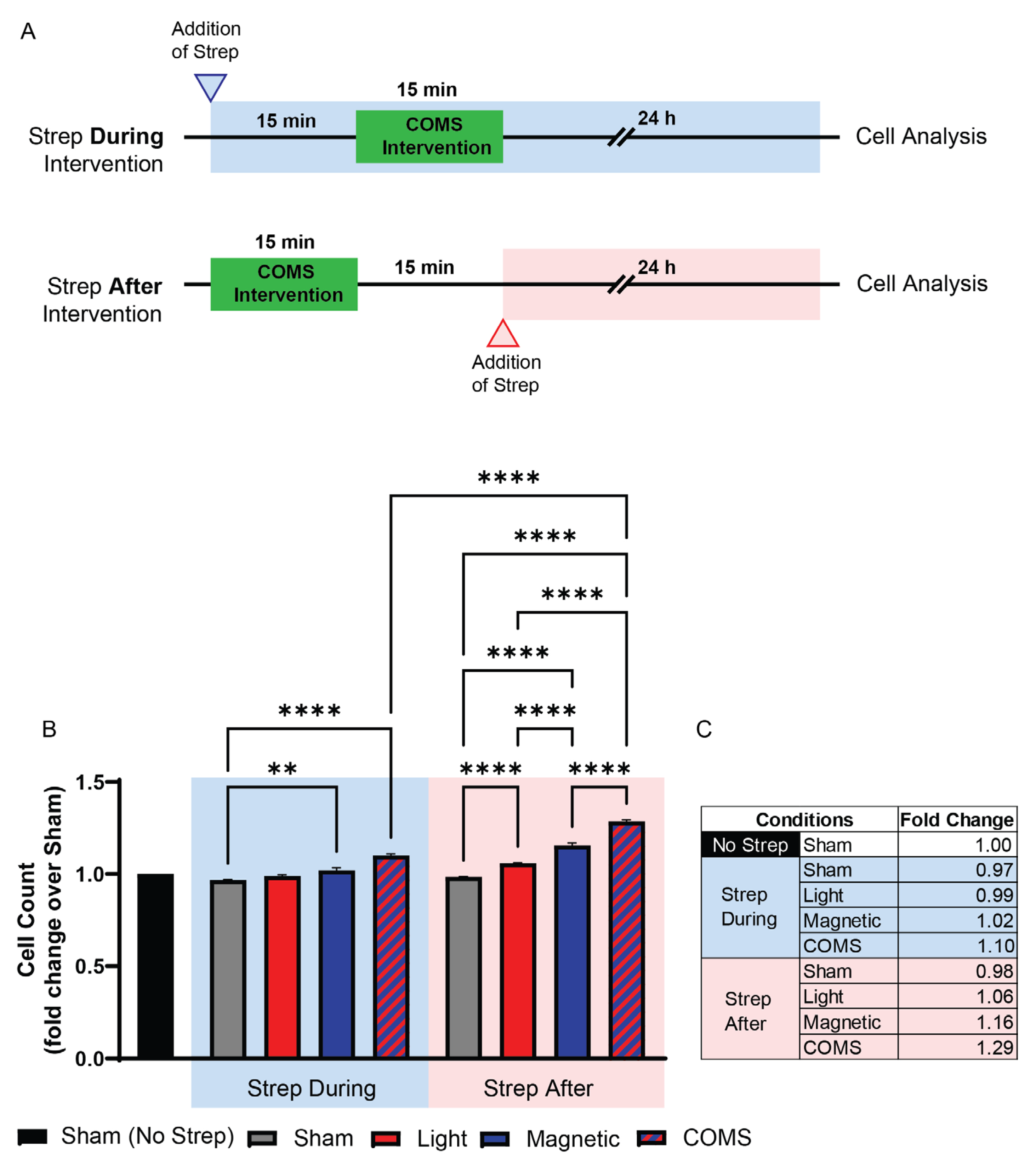

The presence of streptomycin, timed to coincide with magnetic exposure, was previously shown to preclude magnetotransduction [

4]. Streptomycin added to the media 15 minutes prior to exposure to any of the interventions attenuated cell proliferation (

Figure 2B; Strep During Exposure). By contrast, the addition of streptomycin 15 minutes after the exposure to either light, magnetic fields or the combination (

Figure 2B; Strep After Exposure) was ineffective at inhibiting proliferation and moreover, was indistinguishable from the responses of cells untreated with streptomycin (

Figure 1). Therefore, a criterion for streptomycin antagonism of electromagnetic regenerative responses is that it be present at the time of exposure.

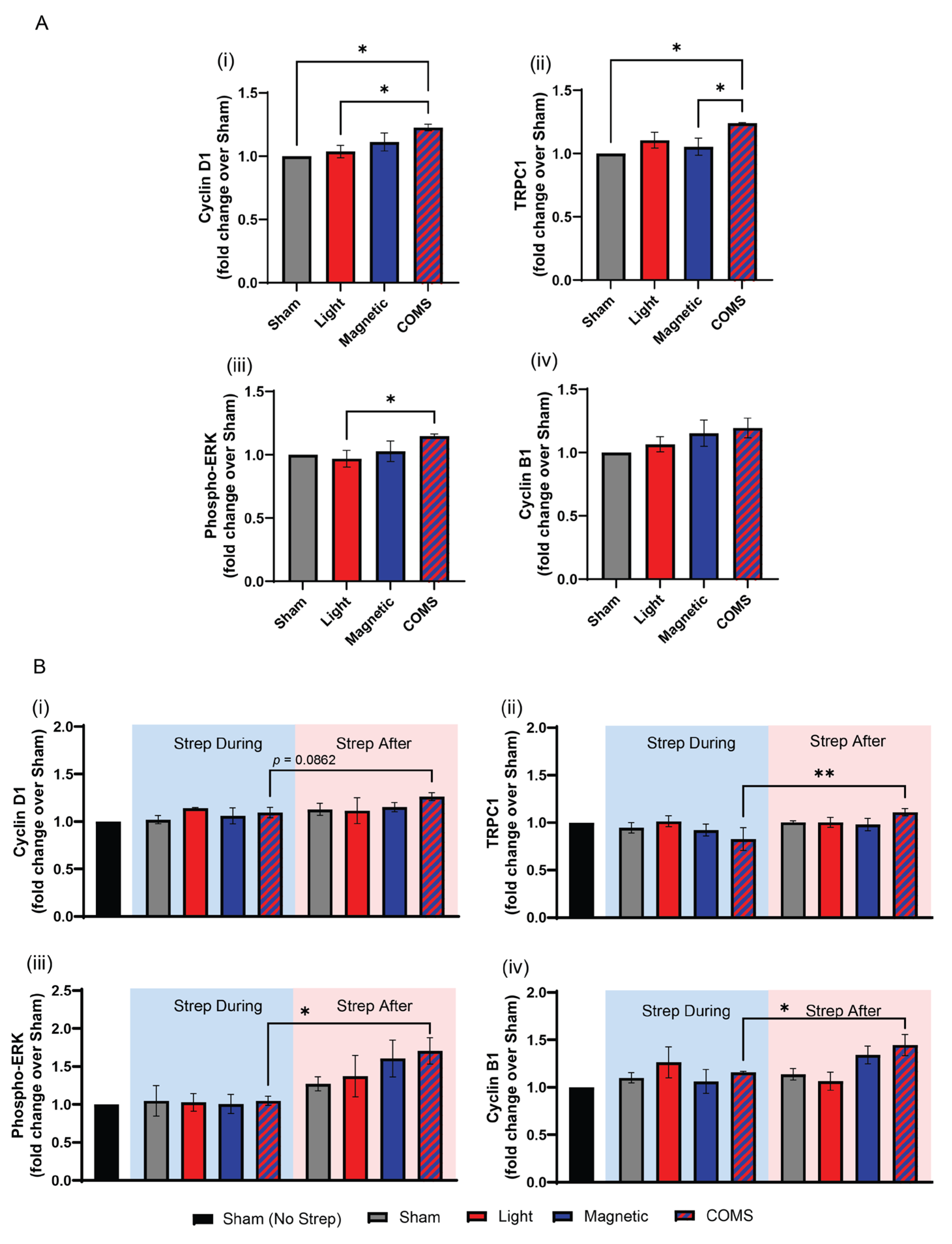

Cyclin D1 promotes cell cycle progression, favoring proliferation at the expense of differentiation [

12]. Cyclin D1 protein levels were significantly increased over sham exposure (grey) by the combination of light and magnetic fields (COMS; hatched blue/red)), whereas the other stimulation conditions did not significantly increase Cyclin D1 protein levels (

Figure 3Ai). TRPC1 protein expression was also increased by the COMS modality (

Figure 3Aii) in agreement with previous reports of a TRPC1-mitochondrial signaling axis that is both responsible for, as well as a part of, the magnetoreceptive proliferative response invoking cyclin D1 [

4]. TRPC1 expression also appeared to be most sensitive to streptomycin antagonism, which coincides with demonstrated feedback regulation of TRPC1 expression by magnetic field exposure [

4]. The MAP/ERK pathway stimulates transcriptional cascades involved in cell proliferation and survival in response to magnetic field exposure [

13]. Accordingly, Phospho-ERK protein expression was preferentially upregulated by COMS stimulation (

Figure 3Aiii). In agreement with cellular proliferative responses being antagonized by aminoglycoside antibiotics, streptomycin added 15 mins before COMS stimulation precluded the upregulations of cyclin D1, TRPC1 and phospho-ERK, whereas the administration of streptomycin 15 mins after COMS intervention did not (

Figure 3Bi, ii, iii).

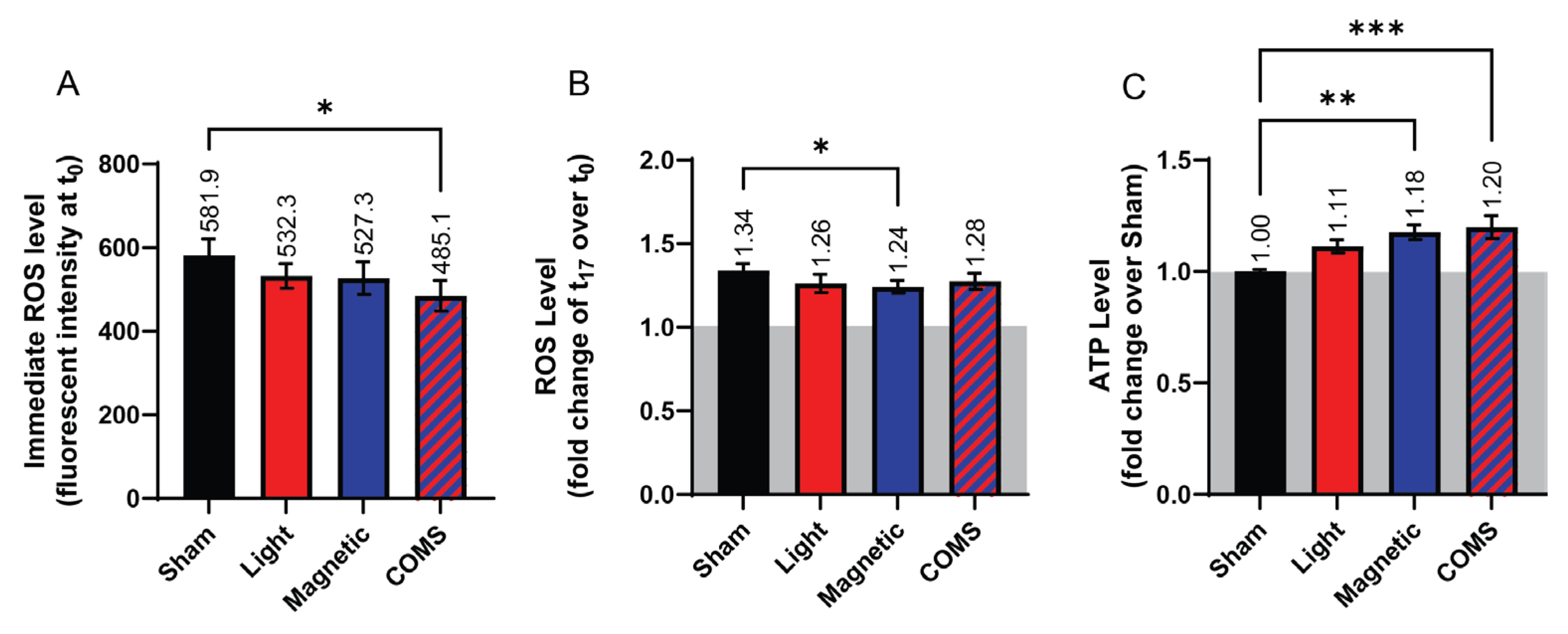

Changes in ROS and ATP production in response to the various interventions were next investigated. Paralleling the response in protein expression, cells treated with the COMS modality showed a significant reduction in ROS production (

Figure 4A, absolute fluorescent intensity) relative to sham (black), whereas the reductions in ROS levels did not achieve statistical significance in response to the other exposure conditions, albeit showing the same incremental responses to light and magnetic fields as for cell proliferation (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) and protein expression (

Figure 3). Additionally, the rate of ROS accumulation showed a tendency to be reduced across all interventions relative to sham (

Figure 4B, fold change over respective baseline). In an anti-parallel manner to ROS production, accumulative ATP levels (fold change over sham) were significantly increased by lone magnetic field exposure and more greatly so by COMS intervention, whereas ROS production in response to light exposure did not achieve statistical significance. These results corroborate previous indications of synergism between magnetic fields and light exposure at the level of mitochondrial responses.

Figure 3.

Myogenic protein expression in response to exposure to light, magnetic fields, and their combination. (A) Protein expression of (i) Cyclin D1, (ii) TRPC1, (iii) phosphorylated ERK, (iv) and Cyclin B1 in response to the indicated exposure intervention (n = 3). (B) Protein expression of (i) Cyclin D1, (ii) TRPC1, (iii) phosphorylated ERK, (iv) and Cyclin B1 in the presence (blue shaded box) and absence (red shaded box) of streptomycin as indicated (n = 3). All data shown in panel B were collected from cells of the same plating and represent independent cell samples as those used in panel A. Statistical analyses were performed minimally in three independent biological replicates. Data were analyzed using One-Way ANOVA followed by multiple comparison tests. Significance levels are indicated as follows: *p<0.05 and **p<0.01. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Figure 3.

Myogenic protein expression in response to exposure to light, magnetic fields, and their combination. (A) Protein expression of (i) Cyclin D1, (ii) TRPC1, (iii) phosphorylated ERK, (iv) and Cyclin B1 in response to the indicated exposure intervention (n = 3). (B) Protein expression of (i) Cyclin D1, (ii) TRPC1, (iii) phosphorylated ERK, (iv) and Cyclin B1 in the presence (blue shaded box) and absence (red shaded box) of streptomycin as indicated (n = 3). All data shown in panel B were collected from cells of the same plating and represent independent cell samples as those used in panel A. Statistical analyses were performed minimally in three independent biological replicates. Data were analyzed using One-Way ANOVA followed by multiple comparison tests. Significance levels are indicated as follows: *p<0.05 and **p<0.01. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Figure 4.

Dichotomous changes in ROS and ATP production following COMS exposure. (A) Bar chart showing the immediate ROS response of cells (fluorescent intensity averaged during initial 3 minutes of reading) for the indicated interventions (n = 4). (B) ROS level of cells expressed as fluorescent intensity fold change at 17 min (t17) over time 0, (t0), (n = 5). (C) The bar chart shows the ATP levels of cells (expressed as fold change over Sham) at t17. (n = 2, with 6 technical replicates each). In all cases, cells were exposed for 5 minutes to the indicated exposure modality at the start of device activation before measurements were commenced. Data were analyzed using One-Way ANOVA followed by multiple comparison tests with *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Figure 4.

Dichotomous changes in ROS and ATP production following COMS exposure. (A) Bar chart showing the immediate ROS response of cells (fluorescent intensity averaged during initial 3 minutes of reading) for the indicated interventions (n = 4). (B) ROS level of cells expressed as fluorescent intensity fold change at 17 min (t17) over time 0, (t0), (n = 5). (C) The bar chart shows the ATP levels of cells (expressed as fold change over Sham) at t17. (n = 2, with 6 technical replicates each). In all cases, cells were exposed for 5 minutes to the indicated exposure modality at the start of device activation before measurements were commenced. Data were analyzed using One-Way ANOVA followed by multiple comparison tests with *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM).

4. Discussion

Electromagnetism (pulsed magnetic fields and photons) is increasingly being recognized for its broad regenerative capacity, if appropriately executed [

3]. The separate and combined light and magnetic field components of the Concurrent Optical and Magnetic Stimulation (COMS) paradigm demonstrated graded and synergistic effects that served to modulate cellular respiration and that ultimately translated into enhanced proliferation. Light exposure on its own consistently produced the smallest change in a measured parameter yet acted in a supra-additive manner when combined with magnetic field exposure in the form of the COMS modality to produce the greatest overall response. Light hence appeared to play a faciliatory role in achieving synergism within the context of the comprehensive COMS stimulation.

In particular, TRPC1 has been implicated in both photomodulatory [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] as well as magnetoreceptive [

4,

5,

11] biological responses. Notably, the TRPC subfamily holds the highest degree of homology to the original

Drosophila phototransductive TRP channel [

19], the founding member of the entire superfamily [

20,

21,

22]. Moreover, both magnetoreception [

4] and photomechanical transduction [

23] could be prevented by pretreatment with the same promiscuous TRPC1 antagonist, 2-APB. The aminoglycoside antibiotics also have been previously shown to disrupt TRPC1-dependent magnetoreception in diverse cell types [

4,

6]. Here we examined the ability of streptomycin, an aminoglycoside antibiotic, to influence the photosensitive and magnetoreceptive components of COMS.

The addition of streptomycin to the bathing media 15 minutes prior to COMS stimulation attenuated a cellular response, whereas the addition of streptomycin 15 minutes following COMS stimulation did not interfere with cellular response to electromagnetic exposure (

Figure 2). The critical difference being that streptomycin was present during cell exposure in the first scenario and did not coincide with exposure in the second scenario. Importantly, as the cell response was measured 24 hours after electromagnetic exposure, the difference in time spent in the presence of streptomycin (30 minutes) was nominal by comparison. Hence, the observed differences in proliferation induction could not be attributed to the inhibition of protein synthesis commonly attributed to diverse antibiotic classes [

24].

Cyclins D1 and B1 regulate cell cycle progression from G1 to S and from S to G2/M phases, respectively [

25,

26]. Both cyclins D1 and B1 are regulated by TRPC1-mediated calcium entry to control the proliferation of the same murine myogenic cell line employed in the present study [

27,

28]. Cyclins D1 and B1 expression levels were increased by all stimulation modes, but most strongly by the COMS intervention. As previously reported, streptomycin added during exposure suppressed the COMS-induced rise in either cyclin, implicating the involvement of TRPC1 [

4].

TRPC1 and TRPM7 are the two most highly expressed TRP channels in C2C12 myoblasts [

4,

27,

29] as well as the most ubiquitously expressed overall in the body [

20,

30]. In support of TRPC1 serving to transduce electromagnetic stimuli, the developmental expression pattern of TRPC1 coincided with myoblast proliferative capacity as well as magnetosensitivity [

4,

29], and the silencing TRPC1, but not TRPM7, expression precluded myoblast magnetic responsiveness. Most critically, the vesicular reintroduction of TRPC1 into TRPC1 CRISPR-Cas9 knockdown myoblasts was necessary and sufficient to reinstate the magnetic induction of myoblast proliferation and mitochondrial responses [

11]. Aminoglycoside antagonism of COMS cellular responses is likely occurring through the blockade of TRPC1-mediated calcium entry [

31] that, in turn, serves to modulate magnetic mitohormetic (mitochondrial) adaptations [

3,

4,

32,

33]. The unified COMS modality most effectively reduced ROS and increased ATP levels. Such dichotomous changes in ROS (decrease) and ATP (increase) would be consistent with an improvement in mitochondrial respiratory efficiency [

34] as a result of the synergistic actions of coincident light and magnetic field stimulations.

Aminoglycoside Antagonism of Other Calcium Channels

Calcium-permeable TRP channels are the primary sensory receptors of individual cells [

20,

35], whereas voltage-gated calcium channels relay stimuli reception between cells via direct electrogenic communication [

3]. TRPC1 channels are hence predominantly expressed in proliferating progenitor cells [

4,

36,

37,

38,

39], whereas voltage-gated calcium channels are more characteristic of differentiated tissues [

4,

36,

37,

38]. The aminoglycoside antibiotics also block calcium permeation through L-type voltage-gated calcium channels in diverse species and cell types [

40,

41,

42]. However, the affinity of the aminoglycoside antibiotics for the pore region of L-type voltage-gated calcium channels is much lower [

41,

42,

43,

44] than that for the pore region of TRPC channels [

45], binding in the mM range rather than the µM range, respectively [

46]. At the concentration of streptomycin administered in the present study (100 µg/mL) and based on developmental expression patterns of a variety of cation channels at the proliferative stage of myogenesis [

4], TRPC1 is thus the most likely target for aminoglycoside antibiotic antagonism. On the other hand, the affinity series for the distinct aminoglycoside antibiotic species is similar for L-type voltage-gated calcium [

41,

42,

43,

44] and TRPC [

45] channels.

COMS Electromagnetic Transduction

Evidence exists for both magnetic fields [

4,

5,

11] and light [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] modulating TRPC1 function. Here we showed that the combination of light and magnetic fields (COMS modality) was capable of upregulating TRPC1 expression (

Figure 2A) and could be completely abrogated with streptomycin when applied coincidently with exposure (

Figure 2 B). Light given in isolation generally produced the smallest responses across measures, whereas when combined with magnetic field exposure produced significantly greater responses than magnetic field exposure alone, suggesting that light is permissive to magnetic sensitivity. This type of response indicates that light is acting to establish sensitivity to magnetic fields and would be consistent with the radical pair mechanism of magnetoreception [

47] that has been shown to modulate mitochondrial energetics [

48]. On the other hand, magnetic field-independent mechanisms for photomodulation have also been proposed that employ mitochondrial cytochrome c stimulation [

49], possibly in combination with TRP-channel mediated calcium entry [

50]. The relative contributions and form(s) of photomodulation that are invoked in the present study remain to be identified.

Clinical Implications of Aminoglycoside Antibiotic Antagonism of Electromagnetic Therapies

The aminoglycosides were amongst the first broad-spectrum antibiotics used for clinical purposes that are now garnering renewed interest due to the growing global incidence of antimicrobial resistance [

51]. The antagonism of the COMS modality by the aminoglycosides will have importance beyond that of in vitro electromagnetic regenerative paradigms as they are used across a broad array of in vitro and in vivo medical paradigms that are responsive to diverse developmental stimuli transduced by TRPC1 [

3]. Their use will thus confound the interpretation of data generated by employing in vitro or in vivo electromagnetic paradigms. The topical use of the aminoglycoside antibiotics is clinically appealing as they can be administered locally at high concentrations for extended periods, effectively circumventing the risks associated with systemic useage such as organ toxicity and gut microflora dysbiosis. Despite their broad acceptance, however, the aminoglycoside antibiotics are minimally effective in treating deep-seated wound infections due to their poor penetration and uptake into persister cells [

52,

53,

54]. The aminoglycosides are generally not the first line of defense in soft tissue infections such as chronic or hard-to-heal wounds. Nonetheless, the prophylactic use of the aminoglycosides in the treatment of other medical conditions such as lung infection and tuberculosis may undermine the regenerative efficacy of other COMS methodologies.

5. Conclusions

The distinct electromagnetic stimulation modes of Concurrent Optical and Magnetic Stimulation (COMS) were shown to exert incremental yet synergistic effects. Light appeared to play a permissive role when combined with extremely low frequency magnetic field exposure resulting in supra-additive responses. COMS-induced changes in cell proliferation, cell cycle regulatory proteins, and mitochondrial respiration were correlated with TRPC1 channel expression, previously reported to participate in a calcium-mitochondrial axis invoked by magnetic fields and antagonized by the aminoglycoside antibiotics. Accordingly, streptomycin hampered the ability of the separate and combined COMS stimulation modalities to induce proliferative responses. However, at the dose of streptomycin used in the present study (100 µg/mL), the synergism between concurrent light and magnetic stimulation was capable of partially overcoming the antagonism of streptomycin to achieve statistically significance proliferative enhancements. Given the broad developmental attributes of TRPC1 and its propensity to be antagonized by the aminoglycoside antibiotics, the coincident use of the aminoglycosides during regenerative medicine paradigms should be carefully considered.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org., Figure S1: Plated cells subjected to light, magnetic fields, or both in a tissue culture incubator.

Author Contributions

J.F. provided engineering specifications as well as the research PIOMCS devices for the isolated exposure of light and magnetic fields. Conceptualization, J.F. and A.F-O., methodology, J.N.I., Y.K.T.; validation, J.N.I.; formal analysis, A.F-O., Y.K.T., J.N.I.; investigation, J.N.I.; resources, A.F-O.; data curation, J.N.I., Y.K.T., writing—original draft preparation, A.F-O., J.F., J.N.I.; writing—review and editing, Y.K.T., A.F-O.; visualization, Y.K.T.; supervision, Y.K.T., A.F-O.; project administration, A.F-O.; funding acquisition, A.F-O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by Pulsing Magnetic Field Therapy Research, Singapore (E-551-00-0004-01).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the results are presented in the manuscript. Any other inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors via email.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the Department of Surgery and the Institute of Health Technology and Innovation (iHealthtech) of the National University of Singapore. They would also like to acknowledge the Development Office of the National University of Singapore who organized the fund that supported this study.

Conflicts of Interest

J.F. is a cofounder of Piomic Medical AG. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Reinboldt-Jockenhofer, F., J. Traber, G. Liesch, C. Bittner, U. Benecke, and J. Dissemond, Concurrent optical and magnetic stimulation therapy in patients with lower extremity hard-to-heal wounds. J Wound Care, 2022. 31(Sup6): p. S12-S21. [CrossRef]

- Traber, J., T. Wild, J. Marotz, M.C. Berli, and A. Franco-Obregon, Concurrent Optical- and Magnetic-Stimulation-Induced Changes on Wound Healing Parameters, Analyzed by Hyperspectral Imaging: An Exploratory Case Series. Bioengineering (Basel), 2023. 10(7). [CrossRef]

- Franco-Obregon, A., Harmonizing Magnetic Mitohormetic Regenerative Strategies: Developmental Implications of a Calcium-Mitochondrial Axis Invoked by Magnetic Field Exposure. Bioengineering (Basel), 2023. 10(10). [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.L.Y., Y.K. Tai, J. Fröhlich, C.H.H. Fong, J.N. Yin, Z.L. Foo, et al., Ambient and supplemental magnetic fields promote myogenesis via a TRPC1-mitochondrial axis: evidence of a magnetic mitohormetic mechanism. Faseb j, 2019. 33(11): p. 12853-12872. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q., C. Chen, P. Deng, G. Zhu, M. Lin, L. Zhang, et al., Extremely Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Fields Promote In Vitro Neuronal Differentiation and Neurite Outgrowth of Embryonic Neural Stem Cells via Up-Regulating TRPC1. PLoS One, 2016. 11(3): p. e0150923. [CrossRef]

- Madanagopal, T.T., Y.K. Tai, S.H. Lim, C.H. Fong, T. Cao, V. Rosa, et al., Pulsed electromagnetic fields synergize with graphene to enhance dental pulp stem cell-derived neurogenesis by selectively targeting TRPC1 channels. Eur Cell Mater, 2021. 41: p. 216-232. [CrossRef]

- Parate, D., A. Franco-Obregón, J. Fröhlich, C. Beyer, A.A. Abbas, T. Kamarul, et al., Enhancement of mesenchymal stem cell chondrogenesis with short-term low intensity pulsed electromagnetic fields. Sci Rep, 2017. 7(1): p. 9421. [CrossRef]

- Uzieliene, I., P. Bernotas, A. Mobasheri, and E. Bernotiene, The Role of Physical Stimuli on Calcium Channels in Chondrogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Int J Mol Sci, 2018. 19(10). [CrossRef]

- Ma, T., Q. Ding, C. Liu, and H. Wu, Electromagnetic fields regulate calcium-mediated cell fate of stem cells: osteogenesis, chondrogenesis and apoptosis. Stem Cell Res Ther, 2023. 14(1): p. 133. [CrossRef]

- Sendera, A., B. Pikula, and A. Banas-Zabczyk, Preconditioning of Mesenchymal Stem Cells with Electromagnetic Fields and Its Impact on Biological Responses and “Fate”-Potential Use in Therapeutic Applications. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed), 2023. 28(11): p. 285. [CrossRef]

- Kurth, F., Y.K. Tai, D. Parate, M. van Oostrum, Y.R.F. Schmid, S.J. Toh, et al., Cell-Derived Vesicles as TRPC1 Channel Delivery Systems for the Recovery of Cellular Respiratory and Proliferative Capacities. Adv Biosyst, 2020. 4(11): p. e2000146. [CrossRef]

- Skapek, S.X., J. Rhee, D.B. Spicer, and A.B. Lassar, Inhibition of myogenic differentiation in proliferating myoblasts by cyclin D1-dependent kinase. Science, 1995. 267(5200): p. 1022-4. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., J. Zhang, Y. Lei, Z. Han, D. Rong, Q. Yu, et al., Low frequency pulsed electromagnetic field promotes C2C12 myoblasts proliferation via activation of MAPK/ERK pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2016. 479(1): p. 97-102. [CrossRef]

- Contreras, E., A.P. Nobleman, P.R. Robinson, and T.M. Schmidt, Melanopsin phototransduction: beyond canonical cascades. J Exp Biol, 2021. 224(23). [CrossRef]

- Detwiler, P.B., Phototransduction in Retinal Ganglion Cells. Yale J Biol Med, 2018. 91(1): p. 49-52.

- Moraes, M.N., L.V.M. de Assis, I. Provencio, and A.M.L. Castrucci, Opsins outside the eye and the skin: a more complex scenario than originally thought for a classical light sensor. Cell Tissue Res, 2021. 385(3): p. 519-538. [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, G.L., D.S. Mizobuti, H.N.M. da Silva, C. Covatti, C.C. de Lourenco, M.J. Salvador, et al., Multiple LEDT wavelengths modulate the Akt signaling pathways and attenuate pathological events in mdx dystrophic muscle cells. Photochem Photobiol Sci, 2022. 21(7): p. 1257-1272. [CrossRef]

- Sassoli, C., F. Chellini, R. Squecco, A. Tani, E. Idrizaj, D. Nosi, et al., Low intensity 635 nm diode laser irradiation inhibits fibroblast-myofibroblast transition reducing TRPC1 channel expression/activity: New perspectives for tissue fibrosis treatment. Lasers Surg Med, 2016. 48(3): p. 318-32. [CrossRef]

- Bellemer, A., Thermotaxis, circadian rhythms, and TRP channels in Drosophila. Temperature (Austin), 2015. 2(2): p. 227-43. [CrossRef]

- Kiselyov, K. and R.L. Patterson, The integrative function of TRPC channels. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed), 2009. 14(1): p. 45-58. [CrossRef]

- Goretzki, B., C. Guhl, F. Tebbe, J.M. Harder, and U.A. Hellmich, Unstructural Biology of TRP Ion Channels: The Role of Intrinsically Disordered Regions in Channel Function and Regulation. J Mol Biol, 2021. 433(17): p. 166931. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., G. Sooch, I.S. Demaree, F.A. White, and A.G. Obukhov, Transient Receptor Potential Canonical (TRPC) Channels: Then and Now. Cells, 2020. 9(9). [CrossRef]

- Margiotta, J.F. and M.J. Howard, Cryptochromes Mediate Intrinsic Photomechanical Transduction in Avian Iris and Somatic Striated Muscle. Front Physiol, 2020. 11: p. 128. [CrossRef]

- Khodabukus, A. and K. Baar, Streptomycin decreases the functional shift to a slow phenotype induced by electrical stimulation in engineered muscle. Tissue Eng Part A, 2015. 21(5-6): p. 1003-12. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K., M. Hitomi, and D.W. Stacey, Variations in cyclin D1 levels through the cell cycle determine the proliferative fate of a cell. Cell Div, 2006. 1: p. 32. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, A., A. Maity, W.G. McKenna, and R.J. Muschel, Cell cycle-dependent regulation of the cyclin B1 promoter. J Biol Chem, 1995. 270(47): p. 28419-24. [CrossRef]

- Benavides Damm, T., S. Richard, S. Tanner, F. Wyss, M. Egli, and A. Franco-Obregon, Calcium-dependent deceleration of the cell cycle in muscle cells by simulated microgravity. FASEB J, 2013. 27(5): p. 2045-54. [CrossRef]

- Benavides Damm, T., A. Franco-Obregon, and M. Egli, Gravitational force modulates G2/M phase exit in mechanically unloaded myoblasts. Cell Cycle, 2013. 12(18): p. 3001-12. [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, S., C. Beyer, S. Unternahrer, T. Benavides Damm, G. Schade-Kampmann, M. Hebeisen, et al., Impedance flow cytometry gauges proliferative capacity by detecting TRPC1 expression. Cytometry A, 2014. 85(6): p. 525-36. [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y., Y. Lee, S.M. Kim, Y.D. Yang, J. Jung, and U. Oh, Quantitative analysis of TRP channel genes in mouse organs. Arch Pharm Res, 2012. 35(10): p. 1823-30. [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, C.Y., A.P. Taniguti, A. Pertille, H. Santo Neto, and M.J. Marques, Stretch-activated calcium channel protein TRPC1 is correlated with the different degrees of the dystrophic phenotype in mdx mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 2011. 301(6): p. C1344-50. [CrossRef]

- Bielfeldt, M., H. Rebl, K. Peters, K. Sridharan, S. Staehlke, and J.B. Nebe, Sensing of Physical Factors by Cells: Electric Field, Mechanical Forces, Physical Plasma and Light—Importance for Tissue Regeneration. Biomedical Materials & Devices, 2023. 1(1): p. 146-161. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., L. Jin, Y. Qin, Z. Ouyang, J. Zhong, and Y. Zeng, Harnessing Mitochondrial Stress for Health and Disease: Opportunities and Challenges. Biology, 2024. 13(6): p. 394.

- Nunn, A.V., G.W. Guy, and J.D. Bell, The quantum mitochondrion and optimal health. Biochem Soc Trans, 2016. 44(4): p. 1101-10. [CrossRef]

- Diver, M.M., J.V. Lin King, D. Julius, and Y. Cheng, Sensory TRP Channels in Three Dimensions. Annu Rev Biochem, 2022. 91: p. 629-649. [CrossRef]

- Bidaud, I., A. Monteil, J. Nargeot, and P. Lory, Properties and role of voltage-dependent calcium channels during mouse skeletal muscle differentiation. J Muscle Res Cell Motil, 2006. 27(1): p. 75-81. [CrossRef]

- Bijlenga, P., J.H. Liu, E. Espinos, C.A. Haenggeli, J. Fischer-Lougheed, C.R. Bader, et al., T-type alpha 1H Ca2+ channels are involved in Ca2+ signaling during terminal differentiation (fusion) of human myoblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2000. 97(13): p. 7627-32. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z., Z.M. Wang, and O. Delbono, Charge movement and transcription regulation of L-type calcium channel alpha(1S) in skeletal muscle cells. J Physiol, 2002. 540(Pt 2): p. 397-409. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C. and Y. Shi, TRPC Channels and Cell Proliferation. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2017. 976: p. 149-155. [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Kurtz, G., Inhibition of membrane calcium activation by neomycin and streptomycin in crab muscle fibers. Pflugers Arch, 1974. 349(4): p. 337-49. [CrossRef]

- Haws, C.M., B.D. Winegar, and J.B. Lansman, Block of single L-type Ca2+ channels in skeletal muscle fibers by aminoglycoside antibiotics. J Gen Physiol, 1996. 107(3): p. 421-32. [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.L. and P.D. Langton, Streptomycin inhibition of myogenic tone, K+-induced force and block of L-type calcium current in rat cerebral arteries. J Physiol, 1998. 508 ( Pt 3)(Pt 3): p. 793-800. [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, N.P., M. Streamer, L.I. Lusambili, F. Sachs, and D.G. Allen, Streptomycin reduces stretch-induced membrane permeability in muscles from mdx mice. Neuromuscul Disord, 2006. 16(12): p. 845-54. [CrossRef]

- Audesirk, G., T. Audesirk, C. Ferguson, M. Lomme, D. Shugarts, J. Rosack, et al., L-type calcium channels may regulate neurite initiation in cultured chick embryo brain neurons and N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res Dev Brain Res, 1990. 55(1): p. 109-20. [CrossRef]

- Winegar, B.D., C.M. Haws, and J.B. Lansman, Subconductance block of single mechanosensitive ion channels in skeletal muscle fibers by aminoglycoside antibiotics. J Gen Physiol, 1996. 107(3): p. 433-43. [CrossRef]

- Hamill, O.P. and D.W. McBride, Jr., The pharmacology of mechanogated membrane ion channels. Pharmacol Rev, 1996. 48(2): p. 231-52.

- Hore, P.J. and H. Mouritsen, The Radical-Pair Mechanism of Magnetoreception. Annu Rev Biophys, 2016. 45: p. 299-344. [CrossRef]

- Usselman, R.J., I. Hill, D.J. Singel, and C.F. Martino, Spin biochemistry modulates reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by radio frequency magnetic fields. PLoS One, 2014. 9(3): p. e93065. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., F. Tian, S.S. Soni, F. Gonzalez-Lima, and H. Liu, Interplay between up-regulation of cytochrome-c-oxidase and hemoglobin oxygenation induced by near-infrared laser. Sci Rep, 2016. 6: p. 30540. [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, L.F. and M.R. Hamblin, Proposed Mechanisms of Photobiomodulation or Low-Level Light Therapy. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron, 2016. 22(3). [CrossRef]

- Krause, K.M., A.W. Serio, T.R. Kane, and L.E. Connolly, Aminoglycosides: An Overview. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2016. 6(6). [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, B.A. and C. Hoey, Topical antimicrobial therapy for treating chronic wounds. Clin Infect Dis, 2009. 49(10): p. 1541-9. [CrossRef]

- Punjataewakupt, A., S. Napavichayanun, and P. Aramwit, The downside of antimicrobial agents for wound healing. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2019. 38(1): p. 39-54. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, V., A.E. Sidders, K.Y. Lu, A.Z. Velez, P.G. Durham, D.T. Bui, et al., Overcoming biological barriers to improve treatment of a Staphylococcus aureus wound infection. Cell Chem Biol, 2023. 30(5): p. 513-526 e5. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).