1. Introduction

Prevention and treatment of wounds and wound infections are the urgent tasks of modern practical medicine. Infection of the wound, which could be caused by various microorganisms, leads to violations of the healing process of varying severity. Moreover, each wound infection could spread and cause severe consequences, up to life-threatening sepsis. According to statistical data, the incidence of purulent-inflammatory diseases and infectious complications occupies one of the main positions in the list of surgical diseases: the proportion of patients with purulent infection amongst all surgical patients is 35-40%, and mortality reaches 42% [

1].

In recent years, the problem of treating wounds and wound infections has sharply aggravated due to the emergence and wide spread of pathogenic microflora with multidrug resistance [

2]. In addition, a pronounced modern trend is the growth of the contingent of people with reduced immunity. They have a tendency to various concomitant diseases (allergic diseases, diabetes, etc.) and have restrictions on the use of pharmacological methods of treatment [

3].

These factors update the research and development of new highly effective methods and medical technologies for wound treatment. Non-invasive methods of influencing the wounds, which is based on physical impact on damaged tissues are considered as promising [

4,

5,

6,

7].

In this context, therapeutic methods using optical technologies are of significant interest. Amongst these technologies, in recent years, low-intensity laser therapy [

8,

9,

10], chromotherapy (treatment with various parts of the visible spectrum range [

11], including the treatment of wounds with red [

12], blue [

13] light and with infrared radiation [

14], photodynamic therapy [

15].

Apparently, the most representative segment of optical technologies is ultraviolet (UV) therapy. This is due to the fact that UV radiation has the maximum photochemical and photobiological effects, primarily due to the significant energy of UV photons, commensurate with the energy of chemical bonds in biomolecules. In photobiology, ultraviolet radiation is divided into three spectral regions, including UV-C range (Δλ=200...280 nm), UV-B range (Δλ=280...315 nm) and UV-A range (Δλ=315...400 nm) [

16]. Various biological effects inherent in these ranges are determined by the energy of photons and the depth of their penetration into biological tissue.

So, photons of the UV-C range have maximum energy, though their penetrating ability is practically limited to the upper layer of the epidermis (the stratum corneum - a layer of inanimate (dead) cells). UV-B radiation penetrates deeper - to the basal layer and upper dermal cells, i.e., already affects living cells. UV-A radiation has even greater penetrating power and reaches the upper layers of the dermis (penetration depth up to ~1 mm), however, its photon energy is noticeably lower than the photon energy of UV-C and UV-B ranges.

UV-C and UV-B radiation is strongly absorbed by DNA and protein molecules, causing various destructive modifications in them, ultimately leading to cell death. This process determines the strong biocidal effect of short-wavelength UV radiation, while UV-C radiation has the maximum biocidal effect [

3,

6,

17]. In this regard, it is widely used for disinfection and sterilization of inanimate objects [

18,

19]. Together with this it could be directly used to destroy pathogens in infected wounds.

UV-B radiation has a significantly lower biocidal potential than UV-C, but is characterized by a maximum erythemal effect, causing expansion of capillary vessels, an increase in the permeability of their walls and an increase in local blood flow, which leads to a local intensification of metabolic processes and stimulation of the wound healing process [

3,

4,

17,

21].

Unlike UV-C and UV-B, UV-A radiation is absorbed by DNA weakly, but instead excites other endogenous chromophores (porphyrins, etc.), generating various reactive oxygen species in cells, which, on the one hand, activate cell signaling system, initiating inflammatory and proliferative reactions, and on the other hand, they can cause oxidative damage to DNA bases [

3,

16,

20].

The biological (including therapeutic) effect of exposure to UV radiation depends both on the spectral range of the applied radiation ∆λ, and on the energy dose of exposure D (J/cm

2), determined by the product of the irradiance of the biological object (wound) I

∆λ (in W/cm

2) in a given spectral range ∆λ for exposure time t (s), i.e., D = I

∆λ ·t. In clinical practice, the minimum erythema dose (MED) is taken as the basis for UV radiation dosimetry - the smallest energy dose of skin irradiation (in mJ/cm

2), which causes erythema of minimal intensity, but with clearly defined boundaries. MED is determined individually using biodosimeters [

4,

21]. According to international guidelines, the MED for sensitive skin is assumed to be 25 mJ/cm

2 [

22].

The usage of optical technology in medicine has a long history with roots in ancient Egypt. The beginning of modern methods of phototherapy using artificial sources of radiation are the studies of the Danish physician Niels Ryberg Finsen (1860-1904), conducted more than 100 years ago. A real boom in research and practical usage of optical technologies and UV radiation, in particular, falls on the 30-40s of the 20th century. During these years, practical medicine was not acquainted with antibiotics, so many scientists pinned their hopes on significant progress in the treatment of tuberculosis, purulent-inflammatory and infectious diseases with ultraviolet radiation. Most actively these researches and developments were carried out in Germany, the USA and Great Britain. Extensive experimental material was collected on the bactericidal and therapeutic effects of UV radiation, and many preventive and therapeutic methods for the clinical use of ultraviolet radiation were developed [

17]. These methods are recommended for use almost without changes at the present time [

4,

21,

23,

24,

25].

However, with the advent of antibiotics, interest in UV medical technologies for treating wounds has noticeably weakened, and their use has until now been limited mainly to preventive procedures in physiotherapy rooms. Another factor hindering the widespread introduction of UV therapeutic technologies is the risk of possible long-term side effects of UV irradiation, such as mutagenesis and carcinogenesis, which can occur with inadequate methodological application of such technologies [

3,

17,

20].

The “antibiotics crisis”, which became acute at the beginning of the 21st century, forces medical specialists to reconsider the current paradigm of the medical use of UV radiation [

3,

20]. According to current understandings, UV technologies should be used in situations where the risk-benefit ratio is favorable for UV therapy of wound infections, especially in cases of antibiotic-resistant responsible microorganisms.

Thus, in the work [

20], it is proposed to consider therapy using short-wavelength UV-C radiation as an alternative approach to the prevention and treatment of localized infectious diseases, especially those caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens. The prospects for the usage of UV-C therapy for the treatment of wounds and wound infections are associated with a number of factors, among which the following are primarily noted.

Multidrug-resistant microorganisms are equally sensitive to UV irradiation, as their “wild-type” counterparts [

20,

26,

27].

UV-C radiation destroys microorganisms much faster than antibiotics - hours with UV-C therapy versus several days with antibiotic treatment [

3,

20].

UV-C therapy could be much more cost effective than commonly used antibiotics. The argument for this is the fact that in addition to the inactivation of microorganisms, adequate exposure to short-wave UV radiation promotes accelerated wound healing and restoration of skin homeostasis. The effects of UV-C radiation on wound healing include hyperplasia and enhanced re-epithelialization, granulation tissue formation, and shedding of necrotic tissue [

3,

20,

28].

In the work [

3], in the analysis of the potential of UV-C technologies for the treatment of wound infection caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens, low-pressure mercury lamps with various types of excitations, excimer lamps, and short-wavelength LEDs were considered as sources of UV radiation. All these sources are characterized by a narrow (monochromatic) emission spectrum (the typical width of the emission line (band) is ~2 nm for mercury lamps and ~10 nm for excimer lamps and LEDs) and low irradiance of biological objects (of the order of several milliwatts per square centimeter or less). These physical factors could lead to a number of limitations on the possibilities of therapeutic technologies implemented using them - due to the monochromaticity of radiation, the inactivation of microorganisms is of a pronounced selective nature (the death of a pathogen occurs only if its absorption spectrum coincides with the emission spectrum of the lamp), low intensity requires large exposure times and does not allow effective treatment of massively contaminated wounds.

Thus, in the work [

29], in the study in vivo antimicrobial effect of UV radiation with a wavelength of 254 nm, a 10-fold decrease in the bacterial load in mouse wounds infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus required sufficiently large (hypererythemic) single doses of UV-C radiation – 2.59 J/cm

2. Similar doses of UV-C radiation (2.8 J/cm

2) were also used in clinical trials to study the effectiveness of UV-C therapy for difficult-to-heal ulcers infected with methicillin-resistant St. aureus (MRSA) [

27]. Antifungal UV-C therapy of Candida albicans-contaminated wounds in laboratory animals was carried out at even higher doses of UV-C irradiation (up to ~6.5 J/cm

2) [

30].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. New Approach

This research work proposes a new approach to the treatment of wound lesions, which are complicated by the presence of multiresistant microflora and a possible immunodeficiency background. It consists in treating the wound surface with high-intensity broad-spectrum pulsed optical radiation, continuously covering the entire UV range (from 200 to 400 nm), visible and near infrared spectral regions. As a source of radiation, it is proposed to use pulsed xenon lamps as the most technologically advanced high-temperature plasma emitters to date [

31]. Such lamps have a number of physical and technical features that favorably distinguish them from radiation sources traditionally used in modern phototherapy and suggest their high therapeutic potential and safety of use.

Amongst above features, first of all, the emission spectrum of a pulsed xenon lamp should be noted. In optimal power modes, the lamp emits a powerful continuum in the entire spectral transparency window of the quartz bulb of the lamp, i.e., from 0.2 to 2.7 µm. Various biological objects (microbial cells, subcellular structures, biomolecules, etc.) have different absorption spectra due to different physical and biochemical organization. Photochemical action occurs only when the absorption spectra of the object and the spectrum of the acting radiation coincide (the 1st law of photochemistry is the Grotthus-Draper law).

By irradiating microbial cells (bioobject) with a wide spectrum, such a radiation source effectively affects all types of microorganisms, regardless of their spectral characteristics, as well as all vital cell structures - nucleic acids, proteins, biomembranes, etc. A number of important conclusions follow from this: 1) a broad optical spectrum potentially provides a wide range of antimicrobial activity - all types of microflora are suppressed, regardless of the individual spectral characteristics of microorganisms; 2) broad-spectrum UV irradiation of a microorganism causes a multichannel destructive effect on all vital cell structures, which reduces the overall resistance of the pathogen (lethal doses decrease) and the possibility of its adaptation to UV exposure; 3) a continuous (identical to the solar) emission spectrum could provide synergy of biological effects of different spectral ranges - the strong biocidal effect of short-wave ultraviolet combines with the immuno- and trophostimulating effects of medium- and long-wave UV, visible and near-IR radiation, which potentially creates optimal conditions for the growth of new tissues and accelerated wound healing.

Another fundamental difference between the proposed technology and the known optical therapeutic technologies is associated with a high intensity of impact on biological objects - the characteristic values of pulsed irradiance of treated surfaces are 10 ... 100 W/cm2, the maximum - 1…10 kW/cm2, which is several orders of magnitude higher than the level of intensity of irradiation of objects by traditional sources of UV radiation. High pulse intensity provides conditions for a significant excess of the rate of direct (in this case, destructive with respect to biomolecules) processes over reverse (relaxation, recombination, repair), which increases the resulting quantum yield of photochemical reactions and leads to a decrease in the threshold energy doses necessary to achieve one sort or another of the biological effect. This, on the one hand, ensures the rapidity of disinfection processes, medical and preventive procedures, and on the other - increases potentially the level of safety in the usage of UV radiation.

In addition, at high pulsed intensities of exposure to the microflora, along with photochemical mechanisms of cell destruction, it is possible to implement additional nonstationary photodynamic [

32,

33] and photothermal [

34,

35] destruction processes, which are fundamentally unfeasible when exposed to traditional continuous-wave radiation sources.

The results of numerous experimental studies conducted in recent years both abroad [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40] and in our country [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47] confirm the expected effects. In particular, it has been shown that broad-spectrum high-intensity pulsed UV radiation has unique biocidal properties - where traditional disinfection methods using standard bactericidal mercury lamps reduce the level of infection by a factor of 1000, this technology reduces the concentration of microbes by several million times or even more [

34,

36,

42,

45]. At the same time, all types of pathogenic microflora are suppressed, including the most resistant, incl. resistant to antibiotics, forms of spore microorganisms and viruses. The process remains efficient at extremely high levels of initial microbiological contamination. For a number of pathogens, a significant (up to 30 times) reduction in the threshold energy doses required to provide a given level of decontamination or achieve a sterilizing effect has been experimentally established [

40,

42,

45].

In addition to the physical features of flash xenon lamps noted above, as experience shows, they also have a number of fundamentally important technical and operational properties, such as the ability to operate in a wide range of ambient temperatures (from minus 60 to plus 60 degrees Celsius), instant readiness for operation, the ability to operate one lamp in a wide range of average power (from fractions of a watt to kilowatts) without changing the spectral characteristics, environmental friendliness (no toxic substances (mercury, etc.) are used), etc.

Currently, the use of pulsed xenon lamps as a biocidal tool is becoming more widespread. Initially, technologies based on pulsed xenon lamps were considered as a means of quickly eliminating the consequences of terrorist acts using bioagents [

19,

40]. Currently, such technologies are being actively studied for use in the food industry in order to increase the shelf life of food products and improve product quality, decontaminate packaging, etc. [

36,

37,

38,

39]. In the medical field, pulsed xenon lamps are currently used in installations for air and surface disinfection [

44,

45,

47,

48].

Thus, it can be stated that today there are objective scientific and medical and technical prerequisites for the development of a new generation of medical devices for the treatment and prevention of wounds and wound infection based on the technology of pulsed high-intensity optical irradiation of biological objects.

The object of this research is the apparatus for pulsed optical irradiation "Zarnitsa-A", developed at the Bauman Moscow State Technical University and implementing a new medical technology for the treatment of wounds and infectious diseases.

2.2. Description of the prototype "Zarnitsa-A"

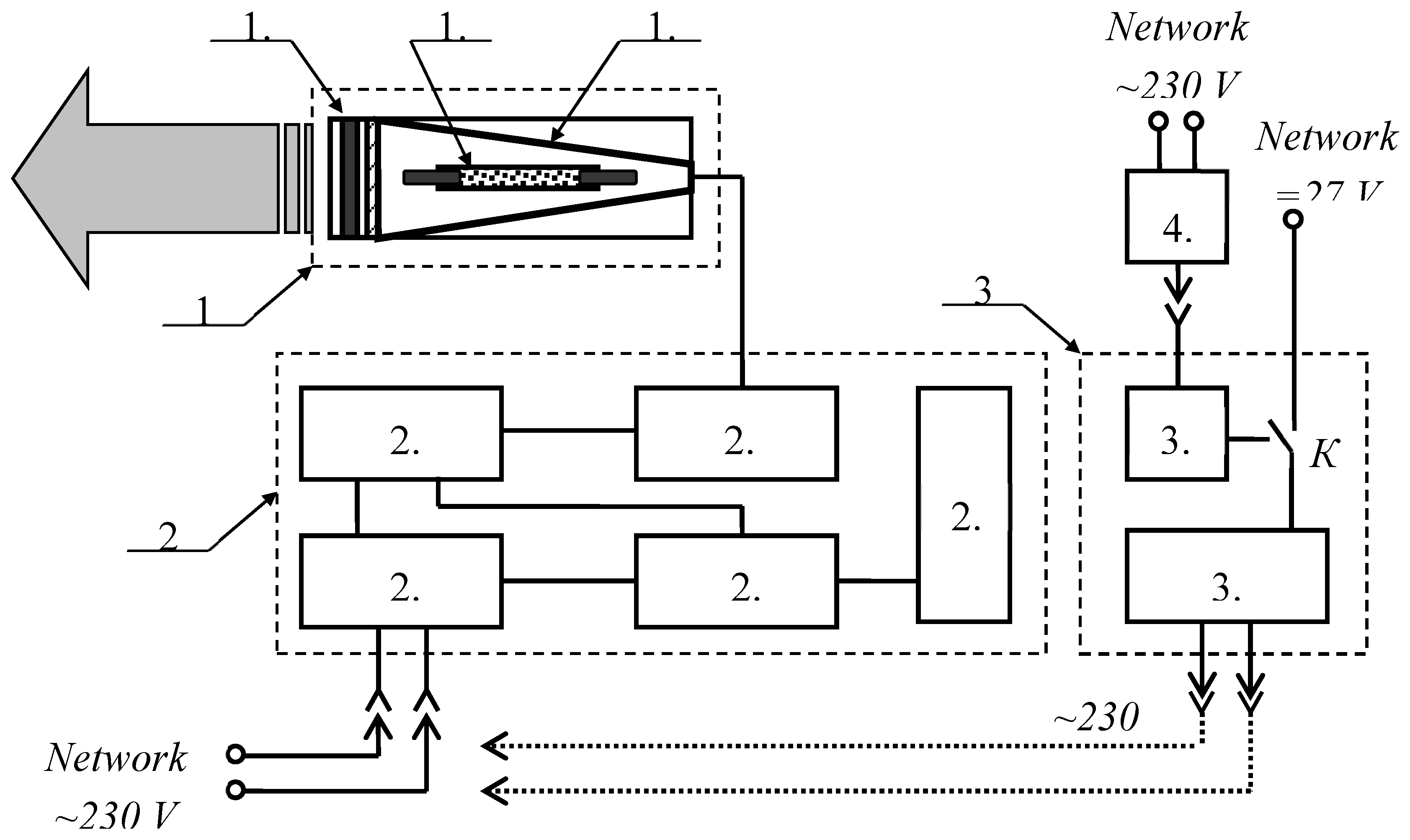

In the research, a prototype of the apparatus "Zarnitsa-A" was used. Its functional diagram is shown in

Figure 1.

The apparatus consists of a service unit (power and control unit), an irradiator and a backup power unit. The principle of operation of the device is based on pulsed irradiation of affected areas up to 50 cm2 in area (per one setting) with high-intensity optical radiation of a continuous spectrum generated by a pulsed xenon lamp. A tubular xenon lamp of the INP-5/60 (pumping flashtube) type with an inner diameter of a quartz bulb of 5 mm and a length of the interelectrode gap of 60 mm was used in the irradiator of the device. The lamp operates in a repetitively pulsed mode with a pulse frequency of 5 Hz and an average electrical power of 100W. The lamp is mounted along the axis of a conical diffuse reflector with an output quartz window with a light diameter of 50 mm. The design of the irradiator allows the installation of additional light filters and/or nozzles outside the exit window that limit the irradiation area. A set of light filters allows you to cut out the necessary wavelength ranges for working in various therapeutic modes. The service unit 2 includes a capacitive storage 2.1 with a stored electrical energy of 20 J, a charge initiation unit 2.2, a capacitive storage charging unit 2.3, a control circuit 2.4 and a control panel 2.5. The service unit is powered by alternating current with a voltage of 230 V directly from the external network or a backup power supply unit. The backup power supply unit 3 consists of an inverter 3.1 and a battery 3.2. The battery is charged using the charging unit 4.1. The formation of alternating current 230 V by the backup power unit 3 occurs by converting the voltage of the on-board network of the vehicle or battery cells through the inverter 3.1. The choice of the power source (battery / on-board network) is made using the toggle switch K, located on the front panel of the backup power unit.

Service unit dimensions - 192x330x142 mm; weight - 6.5 kg. The dimensions and weight of the irradiator are Ø72x298 mm and 0.8 kg, respectively.

On the control panel of the device are installed:

key for supplying power to the device - when the key is turned clockwise to the stop, operating voltages are applied to the power and control circuits;

the "Start" button - when it is pressed, the apparatus starts working - the irradiator emits light flashes that follow at a frequency of 5 Hz for 20 seconds (100 flashes in total) - one irradiation cycle.

the "Stop" button - when it is pressed, the irradiator stops emitting light flashes, but power continues to be supplied to the circuits of the apparatus. When you press the "Start" button again, the operation of the device is resumed.

2.3. Spectral Energy Measurements

Photoelectric measurements of the radiation characteristics of the device were carried out using a calibrated set of photodetectors as part of a “Spektr-01K” photoelectronic converter (FEC), which provides radiation detection in narrow spectral ranges of the UV, visible, and near-IR regions49. Signals from the FEC were recorded with a Tektronix TDS-2014C digital oscilloscope (bandwidth, 70 MHz). The oscilloscope was set to the mode of signal averaging over 64 pulses.

The time-integrated emission spectra of the apparatus were studied using a Solar S100 wide-range fiber-optic spectrometer with a diffraction grating of 300 lines/mm and an S8378-1024 image sensor (manufactured by Hamamatsu). The spectral sensitivity range of the spectrometer is 200…1100 nm, the spectral resolution is 1.5 nm. To register the absolute values of the spectral energy irradiances generated by the device at different distances, we used Ocean Optics P300-1-SR quartz optical fiber (Ø300 µm, Δλ=200…1100 nm) together with a CC-3-UV-S cosine corrector (Δλ= 200…2500 nm). The exposure time of the spectrometer was set from the condition of recording the distribution of energy irradiance averaged over 40 pulses.

The joint calibration of the optical system of the spectrometer with an optical fiber and a cosine corrector in terms of spectral sensitivity was carried out using a reference radiation source DH-3P-CAL (manufactured by Ocean Optics).

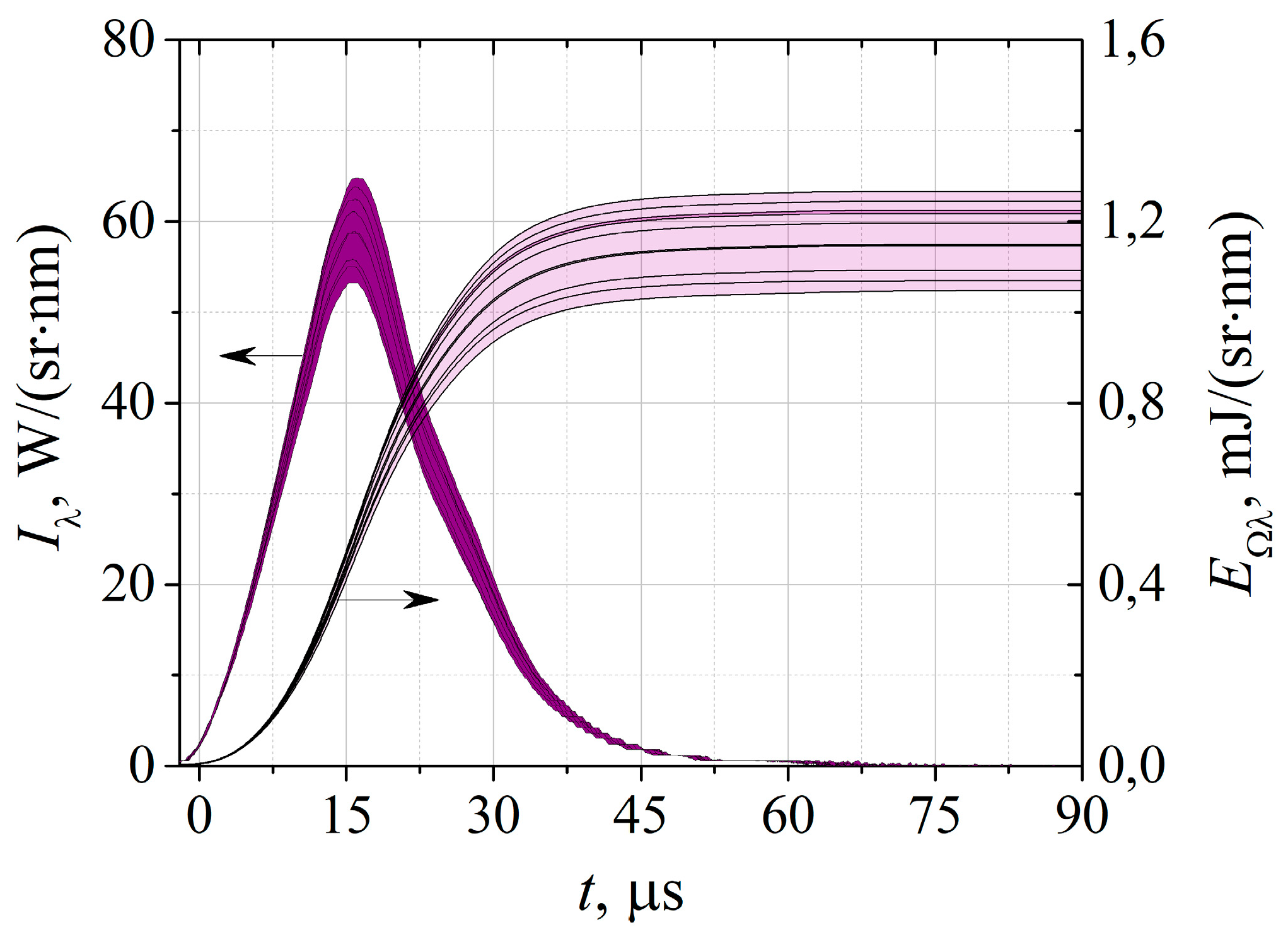

Figure 2 shows the time dependence of the spectral radiation intensity of the “Zarnitsa-A” apparatus in the short-wave UV region of the spectrum (λ=257±14 nm) obtained as a result of processing signals from the Spectr-01K FEC and the result of its integration over time. The thickness of the lines gives the value of the scatter in the values of the measured optical characteristics in 10 different cycles of turning on the apparatus, 64 pulses each. As it could be seen, the spread of pulse energies does not exceed 10%. The duration of the UV-C radiation pulse at half-height is 20.0 ± 0.5 µs. This duration corresponds to the characteristic duration of the energy input into the discharge, which, with an energy stored in the capacitors of 20 J, gives the peak electric power of the lamp ~ 1 MW.

Similar processing of signals from FEC "Spektr-01K" in other spectral ranges made it possible to reconstruct the photoelectronic radiation spectrum of the device and determine the energy-power characteristics of the irradiator integral over the spectrum, which amounted to a radiation power of 31.5 ± 0.1 kW/sr and an angular energy density radiation in the spectral range 200…1100 nm 0.77±0.02 J/sr. At the same time, up to 40% of the total radiated power and ~25% of the integral radiation energy are emitted in the UV region of the spectrum Δλ=200…400 nm. The decrease in the energy efficiency of UV radiation compared to the power efficiency is associated with longer durations of light pulses in the visible and near-IR spectral regions than in the UV range. The data of photoelectric measurements are in good agreement with the results of spectrometric studies performed using the Solar S100 spectrometer.

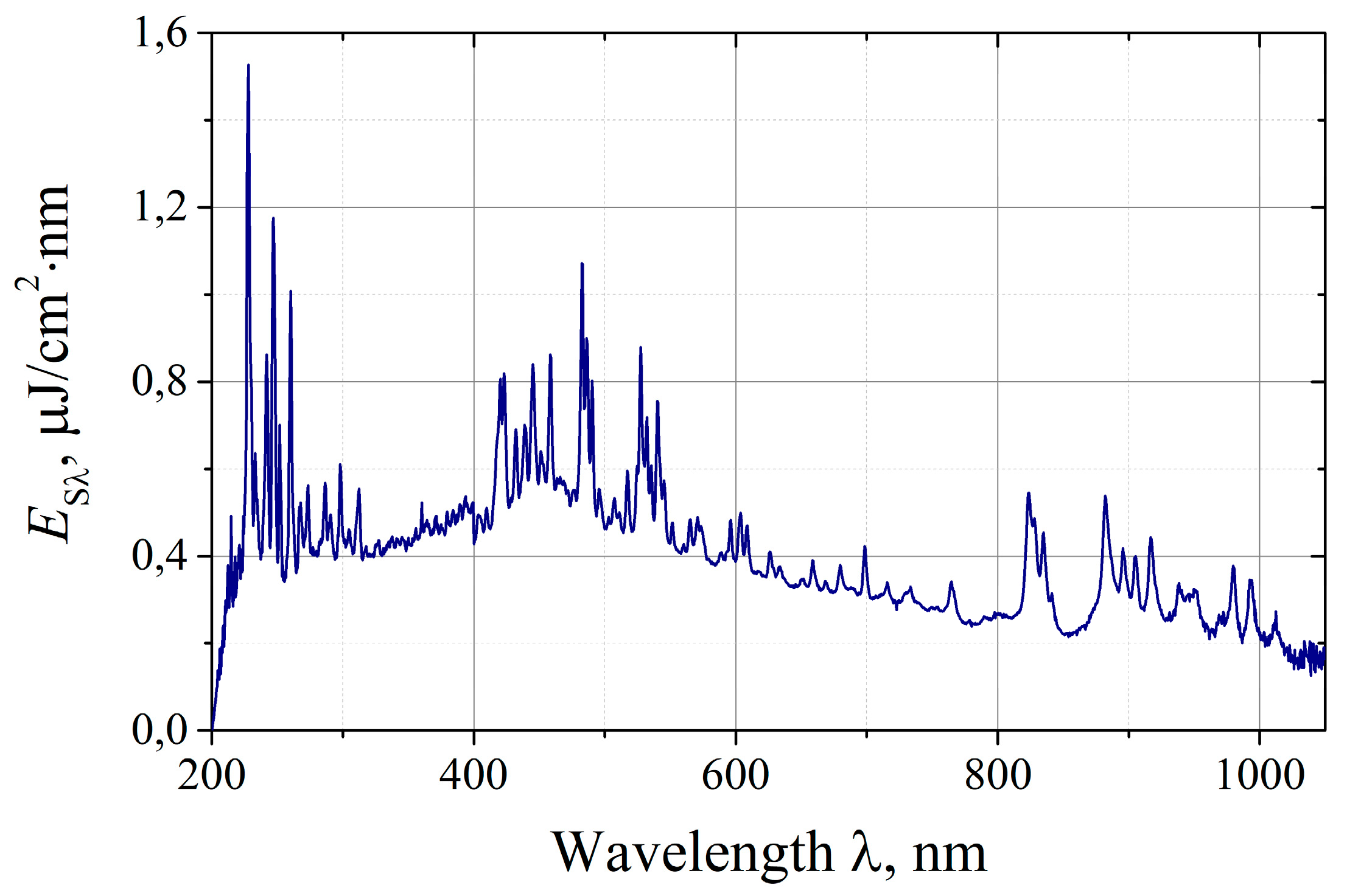

On

Figure 3 it is shown the radiation spectrum of the irradiator of the “Zarnitsa-A” apparatus recorded by the Solar S100 spectrometer. The spectrum is given as a dependence of the spectral energy density of the radiation E

sλ on the wavelength λ for one irradiation pulse at a distance L=50 cm from the irradiator cutoff of the apparatus.

As it could be seen, the emission spectrum of the device is predominantly continuous with powerful lines of atomic and ionized xenon superimposed on it in the short-wave UV region (200 ... 300 nm), visible (420 ... 550 nm) and near IR (800 ... 1000 nm) ranges. The spectrometer registers the emission spectrum in the range of 200…1100 nm, the actual emission spectrum of the xenon lamp (and, accordingly, the irradiator of the device) extends to the long-wavelength limit of the quartz transmission (~2.7 μm), however, the fraction of radiation in the region of 1.1…2.7 μm, as specially conducted measurements show, does not exceed 10% of the radiation energy in the range of 0.2 ... 1.1 μm. By integrating the experimental spectrum over wavelengths, we obtained the radiation energy density of the device in the spectral range of 200…1100 nm per pulse at a distance L=50 cm, which was Es≈0.32 mJ/cm2. This value determines the angular density of the radiation integrated over the spectrum and shows good agreement with photoelectric measurements. A similar procedure makes it possible to determine the spectral efficiencies (or relative shares in the total spectrum) in the actual wavelength ranges. According to the measurements, the share of UV-C radiation is ~10% of the energy emitted in the spectral region Δλ=200…1100 nm, the corresponding shares of UV-B and UV-A ranges are ~4 and ~10%, respectively.

At a distance L=5 cm from the irradiator cutoff of the "Zarnitsa-A" apparatus, according to the spectrometric measurements performed using a fiber-optic light guide with a cosine corrector, the diameter of the light spot in terms of the half-intensity level is D05≈4 cm, while in one irradiation cycle (20 seconds , 100 pulses) in the center of the spot, the total radiation energy density in the integrated spectrum (200…1100 nm) is ~1 J/cm2, respectively, the energy dose in the UV-C range is ~100 mJ/cm2. As the distance increases to L=10 cm, the radiation energy density in the center of the spot decreases by ~2 times, the spot diameter increases to D05≈5.5 cm.

2.4. Preclinical Studies in vitro

Preclinical studies of the bactericidal and wound-healing effectiveness of the Zarnitsa-A apparatus were carried out on the basis of the Izmerov Research Institute of Occupational Health. The purpose of the ongoing microbiological studies was to evaluate the in vitro bactericidal action of the “Zarnitsa-A” apparatus in relation to clinically significant microorganisms (MOs).

The following types of MO were chosen as objects of study:

Preparation of the control strains MOs and the initial suspension was carried out in the following way. A museum strain of a specific MOs was taken and inoculated on slant meat-pentone agar (MPA) to obtain a daily culture. From the obtained daily agar culture of the control strain MOs, a suspension was prepared in physiological saline. The preparation of a suspension with a given concentration of cells was carried out using an optical turbidity standard No. 0.5 according to McFarland. For a more accurate determination of the initial concentration of MOs in the suspension intended for the experiment, serial dilutions of the resulting suspension were performed using the tenfold dilution method.

In the experiments, the following was carried out: 1) positive control (for this - 1.0 cm3 of inoculum was taken from each dilution with an automatic dispenser and transferred to the surface of the agar medium) - it served to control the prepared suspension and further calculate the results; 2) negative control (without inoculation) - served to control the sterility of nutrient media, utensils and instruments.

When preparing the experimental Petri dishes, 1.0 cm3 of seed material was evenly distributed with a spatula over the surface of the agar, not reaching the side walls of the Petri dish by 0.5...1 cm, which was necessary to exclude possible parietal effects. Petri dishes 90 mm in diameter were used in the experiments; accordingly, the area of the sown surface was S≈50 cm2.

The initial density of MOs in the No suspensions varied in the range from 106 to 4.108 CFU/cm3, which, with the inoculated aliquot , gave the initial surface contamination of the agar medium CFU/cm2. MPA was used as a nutrient medium on which MOs was inoculated in all experiments. For each irradiation mode, 3 Petri dishes were prepared to ensure 3-fold repetition of measurements.

Experimental Petri dishes with the inoculated culture (after drying at room temperature) were irradiated with the “Zarnitsa-A” apparatus, while the irradiator of the apparatus was fixed in a special stand, which made it possible to adjust the distance from the irradiator to the irradiated object.

Cups with bacterial inoculations (control and workers after irradiation) were incubated in a thermostat at a temperature of (37±1)°C for 24 hours. After that the formed colonies were counted.

Most of the experiments were performed at a distance from the contaminated surface to the end plane of the irradiator L=10 cm. In the present study, the surface (in the plane of the contaminated surface) radiation energy density in the UV-C range (∆λ=200…280 nm) was taken as a representative dose of radiation. The energy doses of UV-C radiation in the experiments varied from 25 to 150 mJ/cm2, respectively, the exposure time varied from 10 to 60 seconds.

The effectiveness of disinfection was determined by calculating the logarithm of inactivation, equal to the decimal logarithm of the ratio of the initial number of microorganisms in the sample to the number of microorganisms that survived after irradiation with a dose of . The numerical value of the logarithm of inactivation shows how many decimal orders the initial number of bacteria decreased after treatment with a given energy dose.

Another form of representation of the bactericidal efficiency of the device is the efficiency of disinfection, expressed as a percentage and equal to the ratio of the number of inactivated (dead) at a given dose

bacteria

to the number of initially inoculated bacteria

The number of nines in the numerical value of is equal to the integer number of the inactivation logarithm.

2.5. Preclinical Studies in vivo

Animal experiments were agreed and approved by the ethics committee of the Izmerov Research Institute of Occupational Health.

The studies were carried out using Wistar rats. The age of the animals at the beginning of the experiment was 12 ± 2 weeks with a body weight of at least 215 g, which did not deviate from the average for all groups by more than 20%.

The experiments involved 45 male rats in 3 groups of 15 animals in each. In the control group No. 1, wound therapy was carried out only with the use of a broad-spectrum antibiotic (cefazolin at an average therapeutic dose I.M., a course of 8 days); in the control group No. 2, wound therapy was carried out with the use of an antibiotic (cefazolin, a course of 8 days) and treatment with Levomekol ointment. In the third, main group, the wound was treated similarly to the control group No. 2, but with additional irradiation with the “Zarnitsa-A” apparatus.

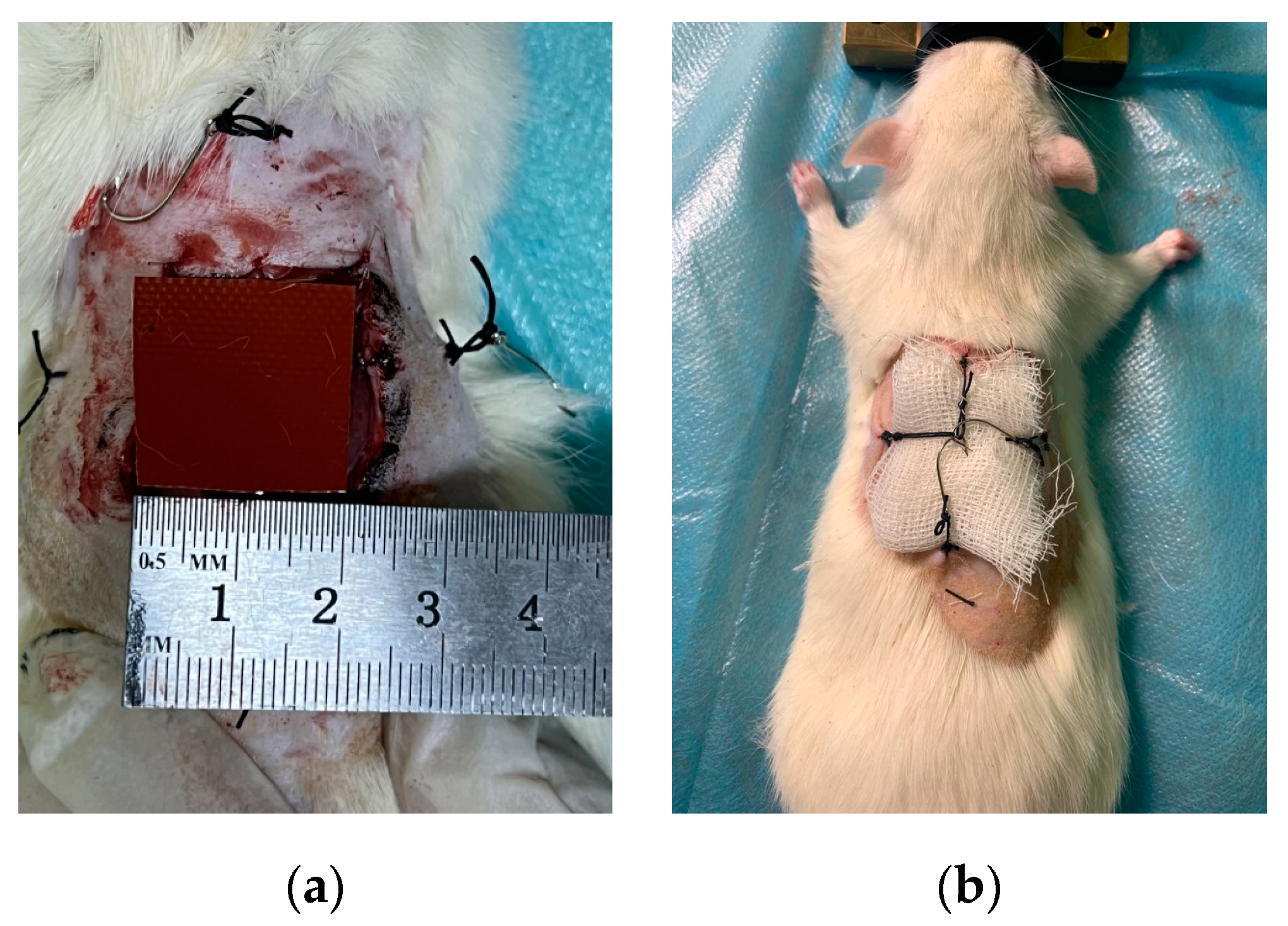

2.5.1. Pathology (wound) modeling

Surgical actions for inflicting a wound defect were carried out in a state of narcotic sleep of animals (sevoflurane was used for anesthesia at a concentration of 4%). After placing the animal on the contour of the anesthetic-respiratory apparatus, depilation of the back area with a size of 60x60 mm was performed. Then, a marker was applied to the skin of the back region using a marker according to a pre-prepared template in the form of a square with sides of 20x20 mm, and a simultaneous excision of the skin with subcutaneous fat was performed within the marked contour (

Figure 4(a)):

The skin edges of the wound were fixed to the underlying superficial and deep fascia of the back with simple interrupted sutures using a “Monocryl 3-0” monofilament suture with a cutting atraumatic needle. Interrupted sutures were placed at the corners and in the middle of all sides of intact skin.

Further, all animals were seeded with the wound surface culture of St. aureus in the amount of 103 CFU.

Immediately after seeding the wound surface, an intramuscular injection of a broad-spectrum antibiotic, Cefazolin, was performed. The dosage was calculated individually according to the weight of the animal. Calculation was done on the base dosage of 55 mg/kg. The average dosage was 12±1 mg of the antibiotic.

The next step was the application of the preparation "Levomekol" (for animals of the 2nd and 3rd groups) and the imposition of sterile gauze bandages (for animals of all groups). The fixation of the bandage was provided by pre-attached hooks and loops (

Figure 4(b)). To ensure the possibility of atraumatic removal and replacement of dressings and due to the impossibility of their standard fixation by dressing due to the behavioral characteristics of rats, two mutually perpendicular hook-loop pairs were additionally prepared on the back of the animal, sutured directly to the intact skin.

For the main group, 1 hour after seeding the wound surface, the wound was treated with radiation from the “Zarnitsa-A” apparatus. At the same time, the organs of vision of the animals were covered with an opaque screen to prevent exposure to high-intensity optical radiation.

Irradiation of the wound surface of the rats of the main group was carried out from a distance from the cut of the irradiator of the "Zarnitsa-A" apparatus to the surface of the wound - L=5 cm. At this distance, the diameter of the light spot was 4 cm at the level of half intensity and exceeded the diagonal (i.e., maximum) wound size (≈2.8 cm). The duration of the irradiation procedure was 60 seconds (three inclusions of 20 seconds each). According to the measurements, under these conditions, the total dose per therapy session in the UV-C range of the spectrum was ~0.3 J/cm2; the corresponding dose in the integrated radiation spectrum (Δλ=200...1100 nm) ~3 J/cm2. Irradiation was carried out daily for 8 days. The total (cumulative) dose in the UV-C range of the spectrum for an eight-day course of therapy was 2.4 J/cm2; cumulative dose in the integrated spectrum ~ 24 J/cm2.

To assess the effect of the apparatus under study on the organs and vital systems of laboratory animals, they were observed for 14 days. The dynamics of the animal's body weight, temperature, and wound surface area were assessed on the 3rd, 7th, 10th, and 14th days. Also at these time points, blood was taken to make a clinical blood analysis. To study the bactericidal action, swabs from the wound surface were carried out 4 hours after the artificial infection of the wound and after irradiation with the apparatus, as well as on the 3rd, 7th, 10th, and 14th days. On the 14th day of the experiment after euthanasia, all animals were sampled for histological examination.

The area of the wound surface was determined by applying a tracing paper to the wound, on which the edges of the wound were outlined. After that the outlined area was estimated using graph paper.

Swabbing from the wound surface were made with a sterile swab soaked in Amies transport medium. To determine the total microbial number, the swabs were placed in a sterile test tube with 10 ml of isotonic sodium chloride solution and thoroughly washed by shaking with glass beads for 10 min. The washing liquid was inoculated by the deep method, 1.0 ml into each Petri dish with MPA (20 ml). The cultures were incubated at 37ºC for 24...48 hours. Then the number of grown colonies was counted and recorded.

Clinical examination of the animals was carried out after the start of the study once a day. During the examination their general condition was recorded.

The rectal body temperature of each animal was recorded using electric thermometers Oakton 10T, OAKTON Instruments, USA with rectal sensors of the appropriate diameter.

Blood sampling for hematological studies was carried out after 12...14 hours of fasting in animals from the lateral tail vein. Blood samples were collected in 4.0 ml tubes and were analyzed within 2 hours after collection. For general clinical blood analysis, a URIT-2900 Vet Plus veterinary hematology analyzer (manufactured by URIT Medical Electronic Co., China) was used. The hematology analyzer is fully automated for counting blood cells and erythrocyte indices.

During histological studies, skin samples were fixed in formalin for 2 days. After passing through alcohols of ascending concentration and chloroform in a Tissue-Tek VIP5Jr apparatus (“Sakura”, USA), skin fragments were poured into a histomix using a Tissue-Tek TEC device (“Sakura”, USA); histological sections 5–8 µm thick were made on a Microm HM340E microtome (“Thermo Scientific”, USA). The obtained preparations were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and according to Van Gieson. Morphological examination of the skin wound was performed using a Leica DM2500 microscope (“Leica Microsystems”, Germany) at 200x and 400x magnification.

2.6. Statistical Processing

Statistical processing of the results was carried out using Microsoft Excel and specialized software for statistical data analysis. The type of data distribution was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov or Shapiro-Wilk criteria. For data with a normal distribution type, the group arithmetic mean (M), standard deviation (SD) was calculated; for data with an abnormal distribution, the median (Me) and interquartile range (25% and 75% percentiles) were determined.

The statistical comparison criterion was chosen based on the type of distribution - intergroup comparison of interval variables measurements for data with a normal distribution were performed using ANOVA analysis of variance, for data with an abnormal distribution or with a normal distribution in cases where ANOVA was not applicable, using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test.

Intragroup comparison of the values of one variable at different measurement periods for data with a normal distribution was performed using ANOVA for repeated measurements, for data with an abnormal distribution, using the Wilcoxon criterion test. Differences were considered statistically significant at p<0,05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Main Results of Preclinical Studies in vitro

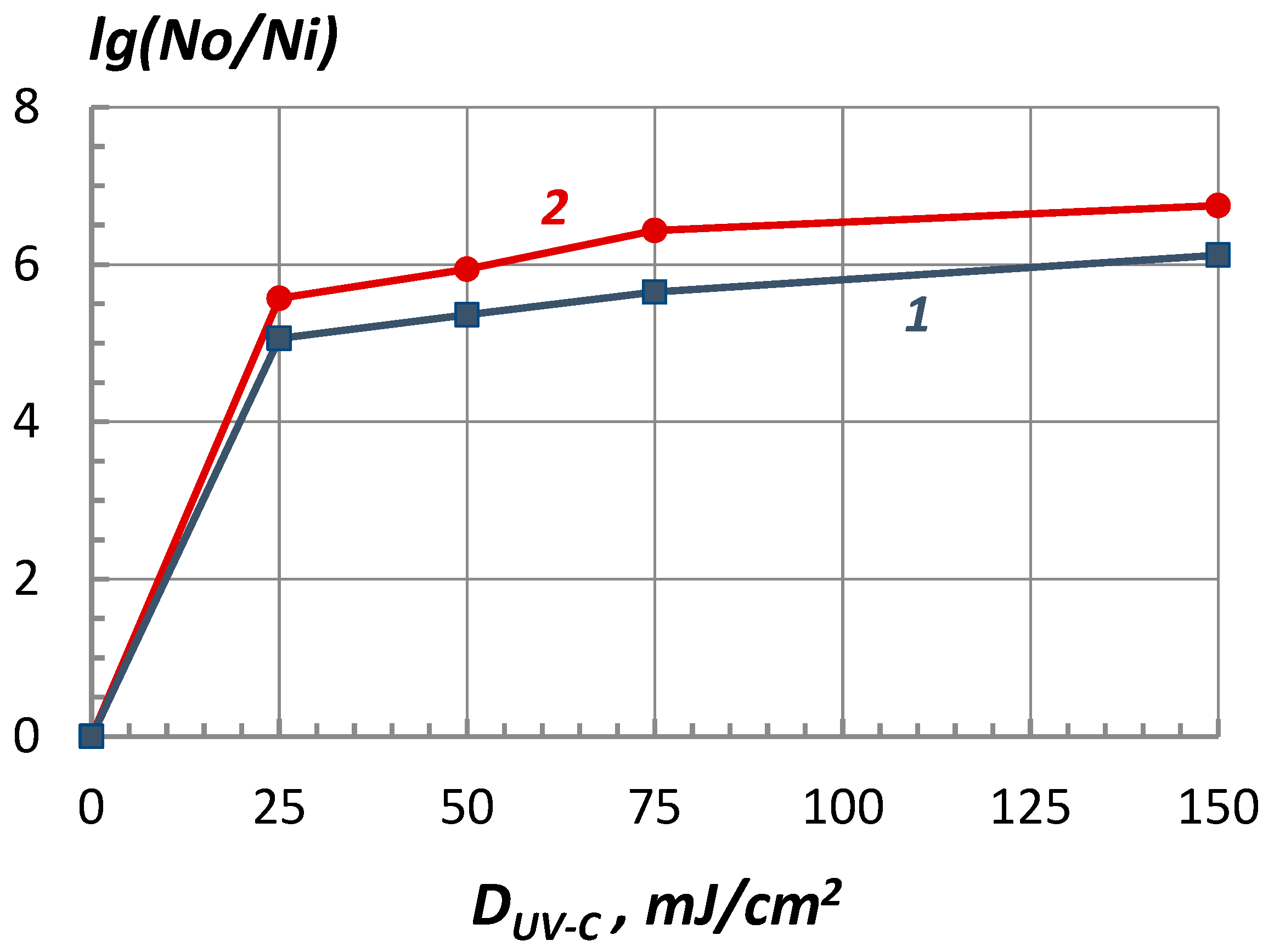

As an example,

Figure 5 shows the results of microbiological experiments to assess the bactericidal effectiveness of the “Zarnitsa-A” apparatus against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus bacteria.

Experimental data are represented as a dependence of the logarithm of inactivation on the energy dose of UV-C radiation (the so-called survival curves) and show that the Zarnitsa-A apparatus provides deep disinfection of a surface contaminated with bacteria already at doses of ~25 mJ/cm2, approximately corresponding to one minimum erythemal dose (MED), a decrease in surface contamination by more than 5 orders of magnitude is achieved (the disinfection efficiency exceeds 99.999%). Similar results were obtained for other studied bacteria - Escherichia coli and Streptococcus pyogenes. No statistically significant differences in the resistance of the selected MOs to high-intensity optical radiation were found in the course of the experiments.

Increasing the dose to 150 mJ/cm2 leads to almost complete sterilization of the surface (absence of colony growth or single colonies were observed).

However, it was noted that with an increase in the energy dose of more than 25 mJ/cm2, the rate of decrease in the level of infection (inactivation rate) decreases, and the survival curves tend to saturate or reach a plateau. This type of survival curve is determined by the heterogeneity of the irradiated bacterial population, i.e., the presence of a fraction of microorganisms resistant to a disinfecting factor (in this case, UV radiation). Another possible reason for the formation of a "tail" of the survival curve is associated with factors of a nonbiological nature, in particular, the mutual shading of bacteria at their high surface density, which is characteristic of the conditions of the experiments.

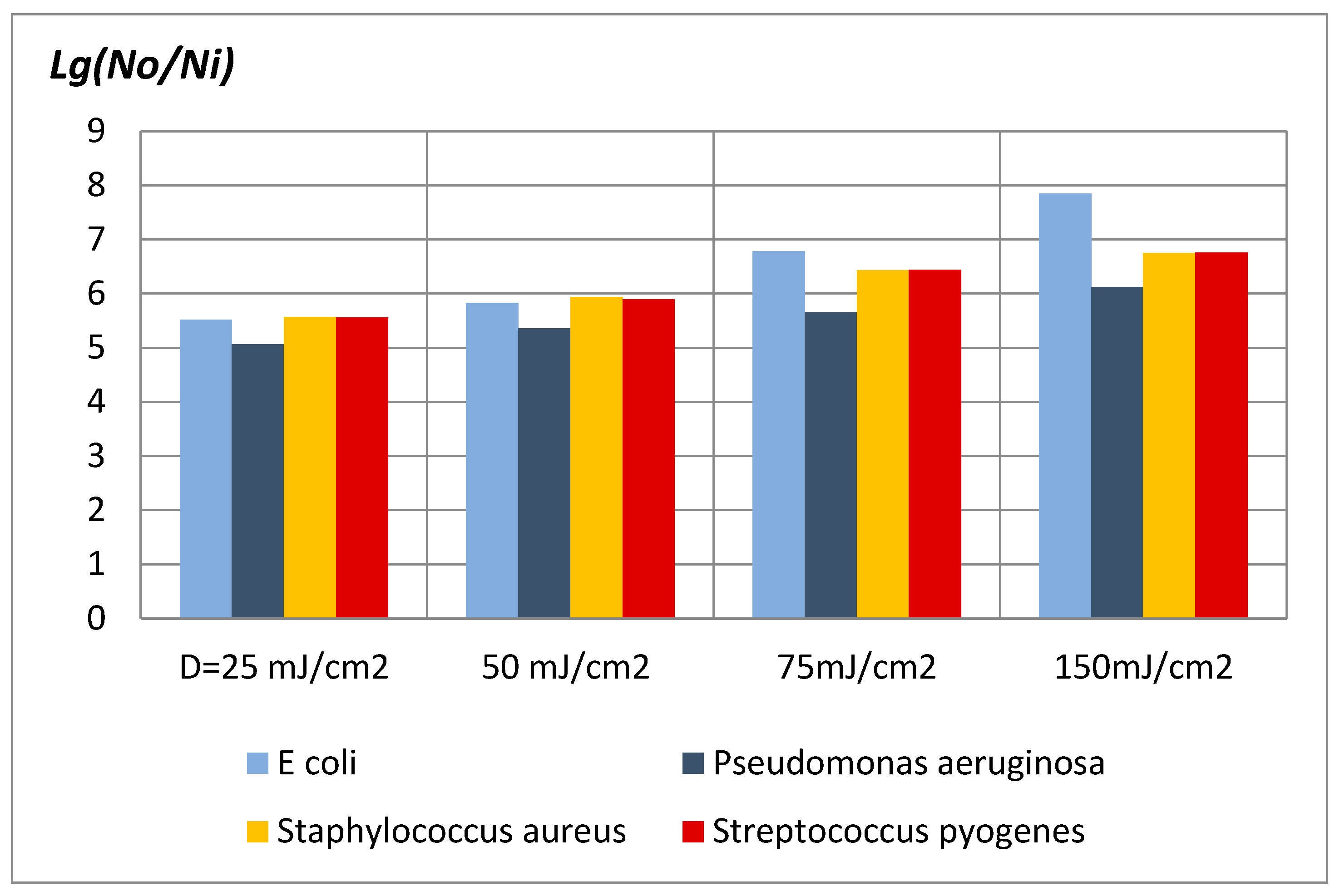

On

Figure 6 the experimental data is represented on the bactericidal effectiveness of the "Zarnitsa-A" apparatus at various doses of UV-C radiation.

Considering that microbiological measurements in this methodological version have an error within one order, it should be stated approximately the same bactericidal effectiveness of the “Zarnitsa-A” apparatus in relation to all the studied types of MO - bacteria of Escherichia and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes. For a 10 second irradiation session from a distance of 10 cm from the emitter of the device to a contaminated surface, the level of bacterial contamination for all types of the indicated microflora decreased by more than 5 decimal orders - the disinfection efficiency exceeded 99.999%.

At a dose of UV-C radiation D=150 mJ/cm2 (three irradiation cycles of 20 seconds each), the reduction in agar surface contamination for all considered microorganisms exceeded a million times (inactivation logarithm lg(N0/Ni)>6). Reducing the distance to a distance of ~5 cm increases the power density of UV radiation on the object by about a factor of two, which makes it possible to halve the duration of the disinfection process (in particular, to 5 seconds while maintaining the energy dose of irradiation ~25 mJ/cm2).

Thus, the experiments carried out testify to the high bactericidal effectiveness of the “Zarnitsa-A” apparatus and the possibility of a significant reduction in the duration of preventive and therapeutic procedures.

3.2. Main Results of Preclinical Studies in vivo (Experiments on Animals)

Daily clinical examination did not reveal any significant symptoms in animals of all experimental groups. Analysis of data on measurements of rectal temperature and body weight of laboratory animals also did not reveal significant differences between the experimental groups.

According to the results of hematological analyzes on the 3rd day in all groups, low values of hemoglobin and other indicators of the erythrocyte germ were noted. Also, almost all rats had a marked increase in the number of leukocytes, which is probably due to the ongoing inflammatory reaction in the animal body. On the 7th day in the main group, there was a significant decrease in the number of leukocyte germ cells compared to the control groups, which serves as an indirect indicator of the bactericidal effect of complex therapy. A significant decrease in the number of erythrocyte germ cells was also noted. In the following days, there was a trend towards a decrease in the number of leukocyte germ cells in all experimental groups, the most pronounced in the main group receiving complex therapy. On the last day of the study in the main group, there was a significant decrease in the number of lymphocytes, platelets and thrombocrit values compared with the control groups.

In general, it could be stated that the selected irradiation regimen does not cause lethal outcomes and pronounced functional and somatic disorders in laboratory animals: analyzes of physiological and hematological parameters did not reveal pathological changes that could be associated with the action of the apparatus under study, which may indicate the potential safety of use of this type of apparatus in clinical practice.

The results of microbiological examination of the wound are represented in the

Table 1.

Analysis of the results of microbiological examination of the wound showed a significant decrease in the average number of colonies of microorganisms in the main group compared with the control groups throughout the research period. On the first and third days, the microflora was represented by gram-positive cocci (St. aureus) in all groups. On the 7th day and further in the control group No. 2 and in the main group, there was no growth of the used pathogenic strain (St. aureus), which prevailed in the control group No. 1. Colonies of microorganisms in the control group No. 2 and in the main group are represented by saprophytic microflora. On the last day of the study, in the control group No. 2, there was a slight increase in microflora, and in the main group there was practically no growth of microflora, while in the control group No. 1, the growth of a predominantly pathogenic strain (St. aureus) was still recorded. Thus, against the background of the used therapy regimens, most animals in the main group indicated a pronounced bactericidal effect.

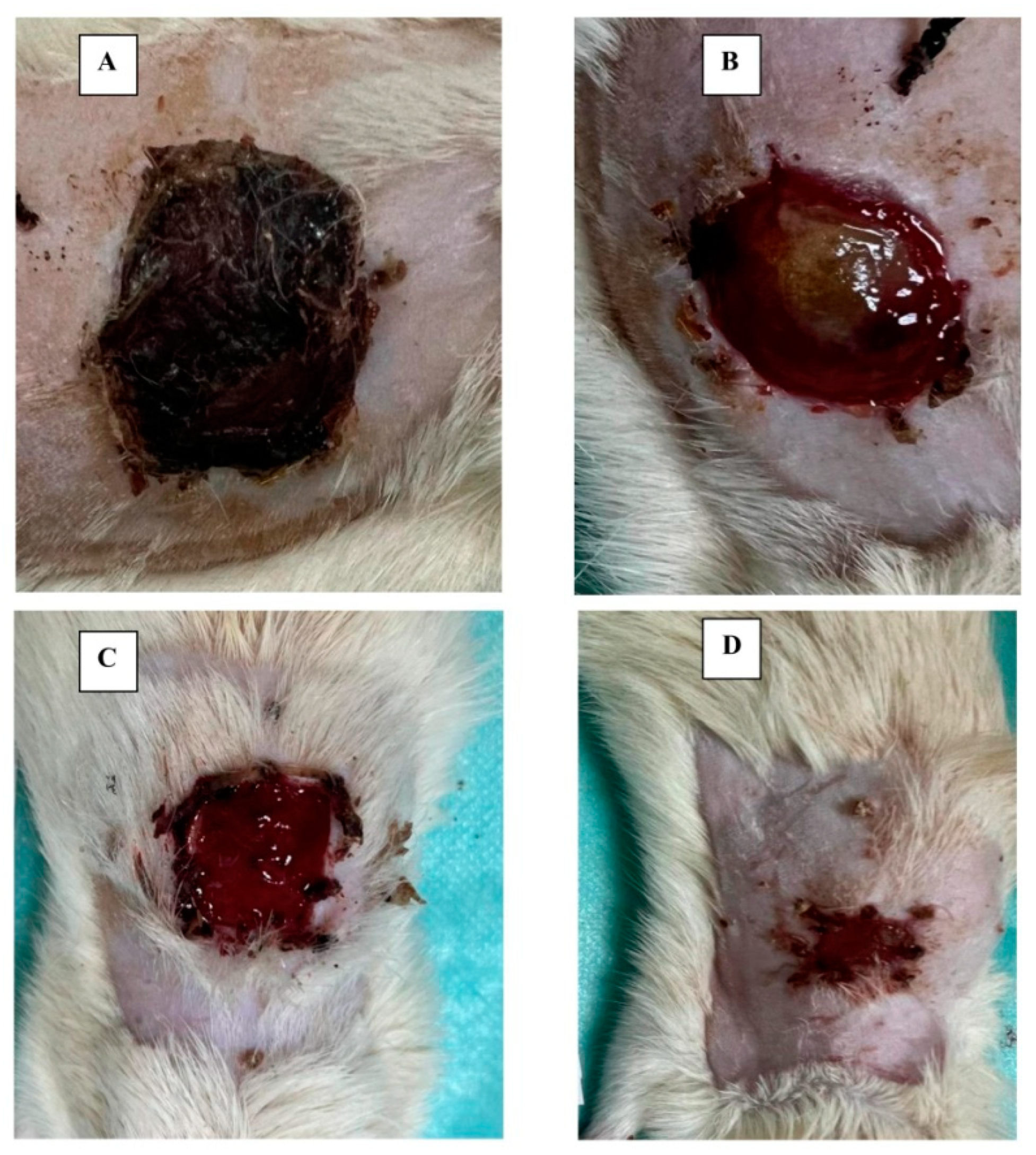

The results of measuring the size of the wound showed a significant decrease in the area of the wound surface in the main group compared with the control groups; at the same time, starting from the 10th day of the study, a clean wound and no exudate were observed in the main group, while in the control group No. 2, the presence of exudate in a clean wound was noted, and in the control group No. 1, after removing the scab, there was a pronounced wound surface with purulent exudate. On

Figure 7 there are photographs showing the state of the wound surface in animals in different groups on the 14

th day of the study.

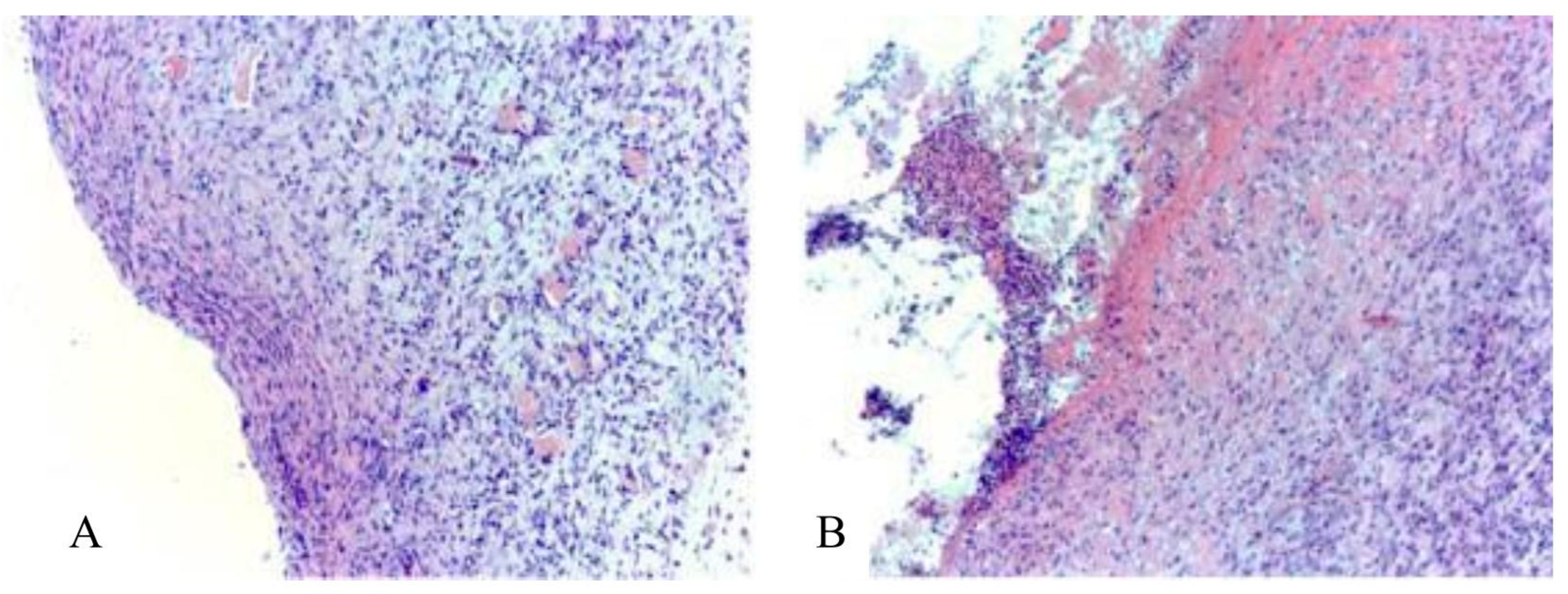

The main results of histological studies in experimental groups of animals were as follows.

In the control group No. 1, on the 14

th day of wound healing, granulation tissue was detected (

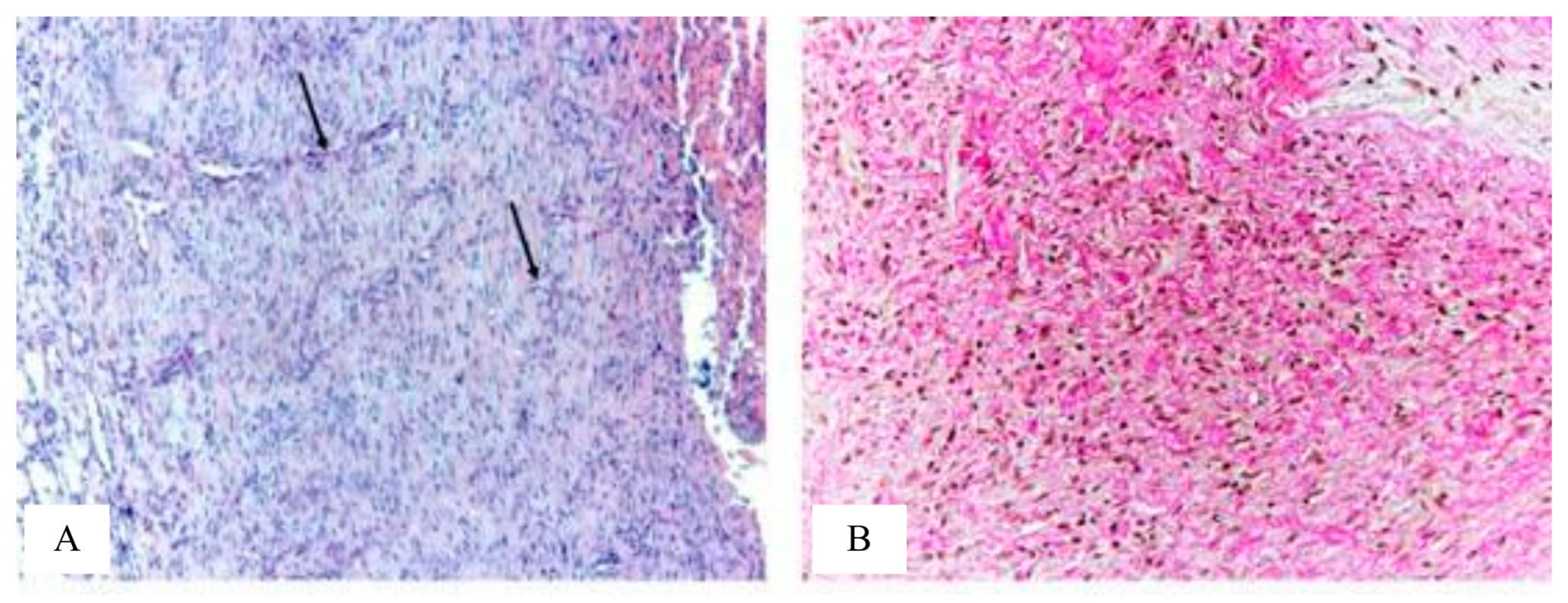

Figure 8), represented by a large number of cells - mainly fibroblasts and fibrocytes, which is typical for phase II of the course of the wound process - proliferation. Granulation tissue contains a large number of plethoric vessels. Vessels are predominantly slit-like, their wall is not formed or partially formed. Collagen fibers are arranged partially ordered. Inflammatory infiltration by lymphocytes, histiocytes and neutrophils in the granulation tissue is pronounced in most animals.

In the control group No. 2, compared with the control group No. 1, the granulation tissue in most animals contains a small number of vessels (

Figure 9). Vessels are predominantly slit-shaped, and some of the vessels are rounded. In slit-shaped vessels in most animals, the wall is partially formed. Collagen fibers are partially ordered. Inflammatory infiltration in the granulation tissue in most rats is mild.

In general, the histological picture of the wound defect in animals of the control groups No. 1 and No. 2 corresponds to the II phase of the course of the wound process - proliferation.

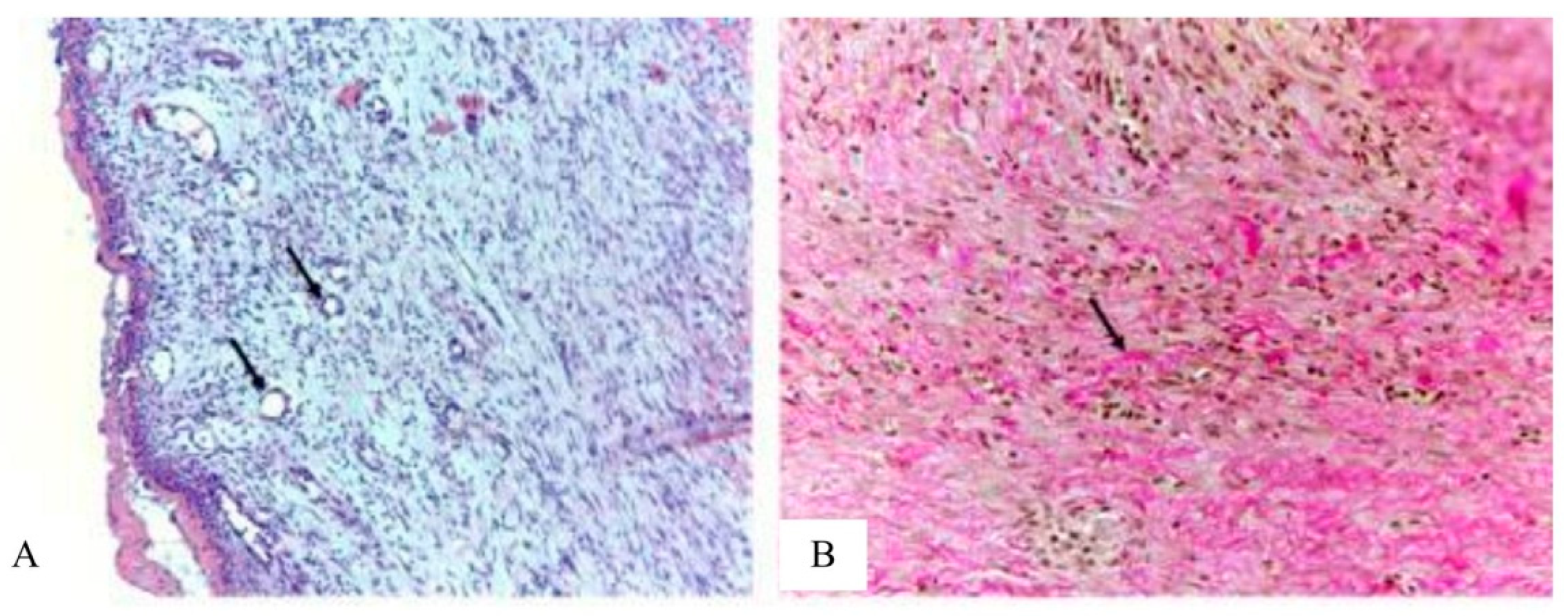

In the main group, in the granulation tissue, blood vessels are predominantly round in shape with formed walls (

Figure 10). Collagen fibers are arranged in an orderly manner. Histologically mature scar tissue is represented by parallel, dense bundles of collagen containing few blood vessels and cells compared to intact tissues. Inflammatory infiltration by lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes in the granulation tissue in all animals is weakly expressed. Thus, in the main group, in contrast to the control groups, according to the morphological characteristics, phase III of the course of the wound process is observed and accelerated wound healing takes place.

4. Conclusions

The problem of prevention and treatment of wounds and wound infection is acute for modern medicine, which is largely associated with the emergence of pathogens with multidrug resistance.

In this work, we propose a new approach to the treatment of wound lesions complicated by the presence of multiresistant microflora and a possible immunodeficiency background. It consists in treating the wound surface with high-intensity broad-spectrum pulsed optical radiation, continuously covering the entire UV range (from 200 to 400 nm), visible and near infrared spectral regions. Impulse xenon lamps are used as a radiation source. Such lamps emit a continuous spectrum in the wavelength range from 200 to 2700 nm and make it possible to irradiate objects with an extremely high intensity, several orders of magnitude higher than the irradiation intensity of traditional therapeutic radiation sources. In fact, broad-spectrum high-intensity pulsed optical radiation is a new, to date, little-studied physical tool for influencing the biological objects, including biomolecules, cells, biological tissues, and the body as a whole. The apparatus of high-intensity pulsed optical irradiation "Zarnitsa-A", which is studied in this work, implements the proposed new medical technology for the treatment of wounds and infectious diseases.

As a result of the preclinical tests of the Zarnitsa-A apparatus, its high bactericidal effectiveness and the possibility of significantly reducing the duration of preventive and therapeutic procedures were shown - in 5 ... 10 seconds of irradiation of massively contaminated surfaces, the disinfection efficiency for clinically significant pathogens is more than 99.999%. In vivo experiments on laboratory animals showed a higher bactericidal efficacy of the Zarnitsa-A apparatus compared to the anti-infective and vulnerary ointment Levomekol.

In a preclinical study of the wound healing effect of the Zarnitsa-A apparatus, it was shown that the selected irradiation regimen, namely: the daily dose of UV-C radiation is 0.3 J/cm2, the fluence integrated over the spectrum is 3 J/cm2 at a cumulative dose of short-wave UV radiation for a course of therapy of 2.4 J/cm2 and a cumulative fluence of 24 J/cm2 did not cause death and pronounced functional and somatic disorders in Wistar rats. Analyzes of physiological and hematological parameters did not reveal pathological changes that could be associated with the action of the device under study.

At the same time, it was found that the Zarnitsa-A high-intensity pulsed optical irradiation apparatus has a pronounced wound healing effect and, in combination with the Levomekol ointment, reliably provides a higher rate of wound healing compared to the usage of the officinal Levomekol ointment only.

The implemented technical characteristics and declared modes of wound irradiation can be recommended as the main ones in the treatment of infected wounds and should be clarified in the course of clinical trials.

The experimental data obtained indicate the potential prospects of using the Zarnitsa-A apparatus for pulsed high-intensity optical irradiation in medical and veterinary practice in the treatment and prevention of wound lesions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.V.B., I.V.B., and A.S.K.; methodology, L.Y.V. and E.V.Z; validation, E.V.Z. and A.V.K. and formal analysis V.I.K.; investigation, L.Y.V., A.V.K. and S.M.N.; resources, A.S.K. and S.M.N.; data curation, D.O.N., L.Y.V., A.V.K. and S.M.N; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.K., I.V.B., L.Y.V. and S.M.N.; writing—review and editing, V.V.B., A.S.K., and E.V.Z; visualization, S.M.N.; supervision, K.A.S., A.S.K. and A.V.K.; project administration, V.V.B. and V.I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Functional diagram of the apparatus "Zarnitsa-A": 1 – irradiator block; 1.1 – replaceable light filter; 1.2 – pulsed xenon lamp; 1.3 – radiation flux shaper; 2 – service block; 2.1 – capacitive storage; 2.2 – the discharge initiating block; 2.3 – capacitive storage charging unit; 2.4 – control and monitoring scheme; 2.5 – control panel; 3 – backup power supply; 3.1 – inverter; 3.2 – battery; 4 – battery charging unit; K – power modes toggle switch.

Figure 1.

Functional diagram of the apparatus "Zarnitsa-A": 1 – irradiator block; 1.1 – replaceable light filter; 1.2 – pulsed xenon lamp; 1.3 – radiation flux shaper; 2 – service block; 2.1 – capacitive storage; 2.2 – the discharge initiating block; 2.3 – capacitive storage charging unit; 2.4 – control and monitoring scheme; 2.5 – control panel; 3 – backup power supply; 3.1 – inverter; 3.2 – battery; 4 – battery charging unit; K – power modes toggle switch.

Figure 2.

Time dependence of the spectral radiation strength of the “Zarnitsa-A” apparatus and the angular density of radiation energy in the short-wave UV region of the spectrum (λ=257±14 nm).

Figure 2.

Time dependence of the spectral radiation strength of the “Zarnitsa-A” apparatus and the angular density of radiation energy in the short-wave UV region of the spectrum (λ=257±14 nm).

Figure 3.

Spectral energy density of the radiation of the apparatus "Zarnitsa-A" per pulse at a distance of 50 cm from the irradiator.

Figure 3.

Spectral energy density of the radiation of the apparatus "Zarnitsa-A" per pulse at a distance of 50 cm from the irradiator.

Figure 4.

Wound modelling. (a) Applying a wound defect according to the template. (b) Fixation of the bandage on the wound surface of the animal.

Figure 4.

Wound modelling. (a) Applying a wound defect according to the template. (b) Fixation of the bandage on the wound surface of the animal.

Figure 5.

Logarithm of the inactivation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (1) and Staphylococcus aureus (2) bacteria by the “Zarnitsa-A” apparatus. Initial density of agar surface contamination N0(1) = 4.105 and N0(2) = 2.106 (2) CFU /cm2.

Figure 5.

Logarithm of the inactivation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (1) and Staphylococcus aureus (2) bacteria by the “Zarnitsa-A” apparatus. Initial density of agar surface contamination N0(1) = 4.105 and N0(2) = 2.106 (2) CFU /cm2.

Figure 6.

Bactericidal effectiveness of the "Zarnitsa-A" apparatus at various doses of UV-C radiation.

Figure 6.

Bactericidal effectiveness of the "Zarnitsa-A" apparatus at various doses of UV-C radiation.

Figure 7.

The condition of the wound surface on the 14th day after modeling the pathology. A, B - control group No. 1, A - wound under the scab; B - wound after removal of the scab, there is a pronounced wound surface with purulent exudate; C - control group No. 2 (levomekol), there is a decrease in the wound surface, the wound contains exudate; D - the main group (levomekol + irradiation with the "Zarnitsa-A" apparatus), there is a pronounced decrease in the size of the wound defect, the absence of exudate.

Figure 7.

The condition of the wound surface on the 14th day after modeling the pathology. A, B - control group No. 1, A - wound under the scab; B - wound after removal of the scab, there is a pronounced wound surface with purulent exudate; C - control group No. 2 (levomekol), there is a decrease in the wound surface, the wound contains exudate; D - the main group (levomekol + irradiation with the "Zarnitsa-A" apparatus), there is a pronounced decrease in the size of the wound defect, the absence of exudate.

Figure 8.

Granulation tissue of the wound of rats of the control group No. 1. Vascular plethora, pronounced inflammatory infiltration by lymphocytes, histiocytes and neutrophils; cells dominate over the fibers (A, B). Massive overlays of exudate (B). Stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Mag. 200x.

Figure 8.

Granulation tissue of the wound of rats of the control group No. 1. Vascular plethora, pronounced inflammatory infiltration by lymphocytes, histiocytes and neutrophils; cells dominate over the fibers (A, B). Massive overlays of exudate (B). Stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Mag. 200x.

Figure 9.

Granulation tissue of the wound of rats of the control group No. 2. A - predominantly slit-shaped blood vessels (black arrows), moderate inflammatory infiltration by lymphocytes, histiocytes and neutrophils. Stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Mag. 200x; B - fuchsinophilic collagen fibers are partially ordered; cells predominate over fibers. Coloring according to van Gieson. Mag. 200x.

Figure 9.

Granulation tissue of the wound of rats of the control group No. 2. A - predominantly slit-shaped blood vessels (black arrows), moderate inflammatory infiltration by lymphocytes, histiocytes and neutrophils. Stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Mag. 200x; B - fuchsinophilic collagen fibers are partially ordered; cells predominate over fibers. Coloring according to van Gieson. Mag. 200x.

Figure 10.

Granulation tissue of the wound of rats of the main group (Levomekol with irradiation). A – blood vessels predominantly round in shape with formed walls (black arrows), weak inflammatory infiltration by lymphocytes, histiocytes and neutrophils; fibers predominate. Stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Mag. 200x;B - collagen fibers are ordered. Coloring according to van Gieson. Mag. 200x.

Figure 10.

Granulation tissue of the wound of rats of the main group (Levomekol with irradiation). A – blood vessels predominantly round in shape with formed walls (black arrows), weak inflammatory infiltration by lymphocytes, histiocytes and neutrophils; fibers predominate. Stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Mag. 200x;B - collagen fibers are ordered. Coloring according to van Gieson. Mag. 200x.

Table 1.

Influence of therapy regimens on the average number of colonies per 1 ml. (IU (25% -75%)).

Table 1.

Influence of therapy regimens on the average number of colonies per 1 ml. (IU (25% -75%)).

| Experimental groups |

Control time |

| 4 hours |

3 days |

7 days |

10 days |

14 days |

| Control №1 * |

44.0 |

300.0 |

300.0 |

300.0 |

300.0 |

| (20.5-300.0) |

(300.0-300.0) |

(250.0-300.0) |

(300.0-300.0) |

(300.0-300.0) |

| Control №2 |

77.0* |

1.0* |

13* |

20* |

7.0* |

| (5.5-294.0) |

(0.0-3.0) |

(2.0-58.0) |

(9.5-197.5) |

(0.5-125.5) |

| Main №3 |

3.5* |

0.0* |

0.0*#

|

0.0*#

|

0.5*#

|

| (2.0-13.0) |

(0.0-0.0) |

(0.0-1.0) |

(0.0-2.5) |

(0.0-2.5) |