Submitted:

04 June 2024

Posted:

06 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Laboratory Procedures

2.3. Sequence Analyses

2.3.1. Genotypic and Mutational Analysis

2.3.2. Impact of Occult-Associated Mutations on Protein Function

3. Results

3.1. Participants Clinical Characteristics

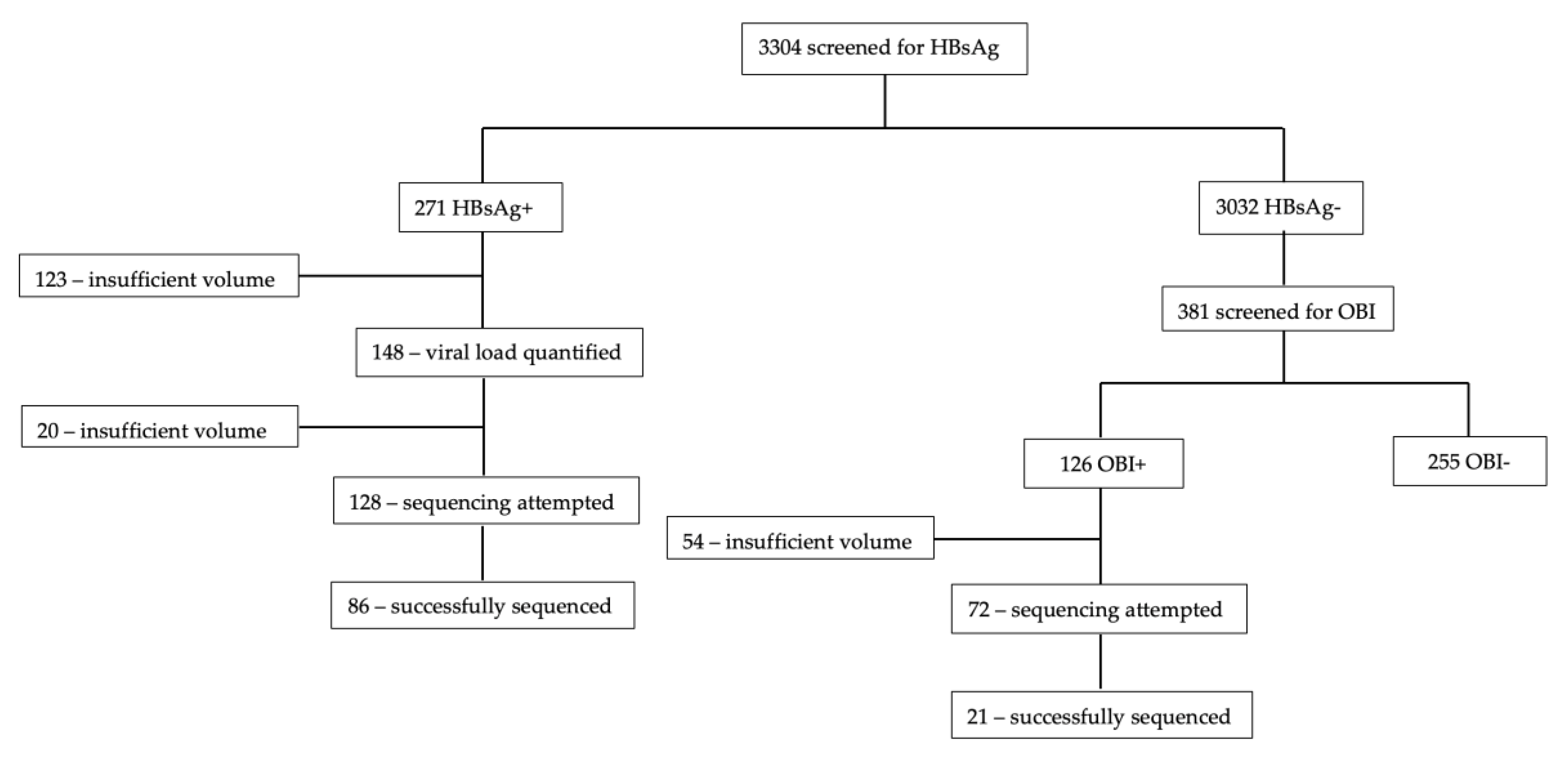

3.2. Sequencing Success

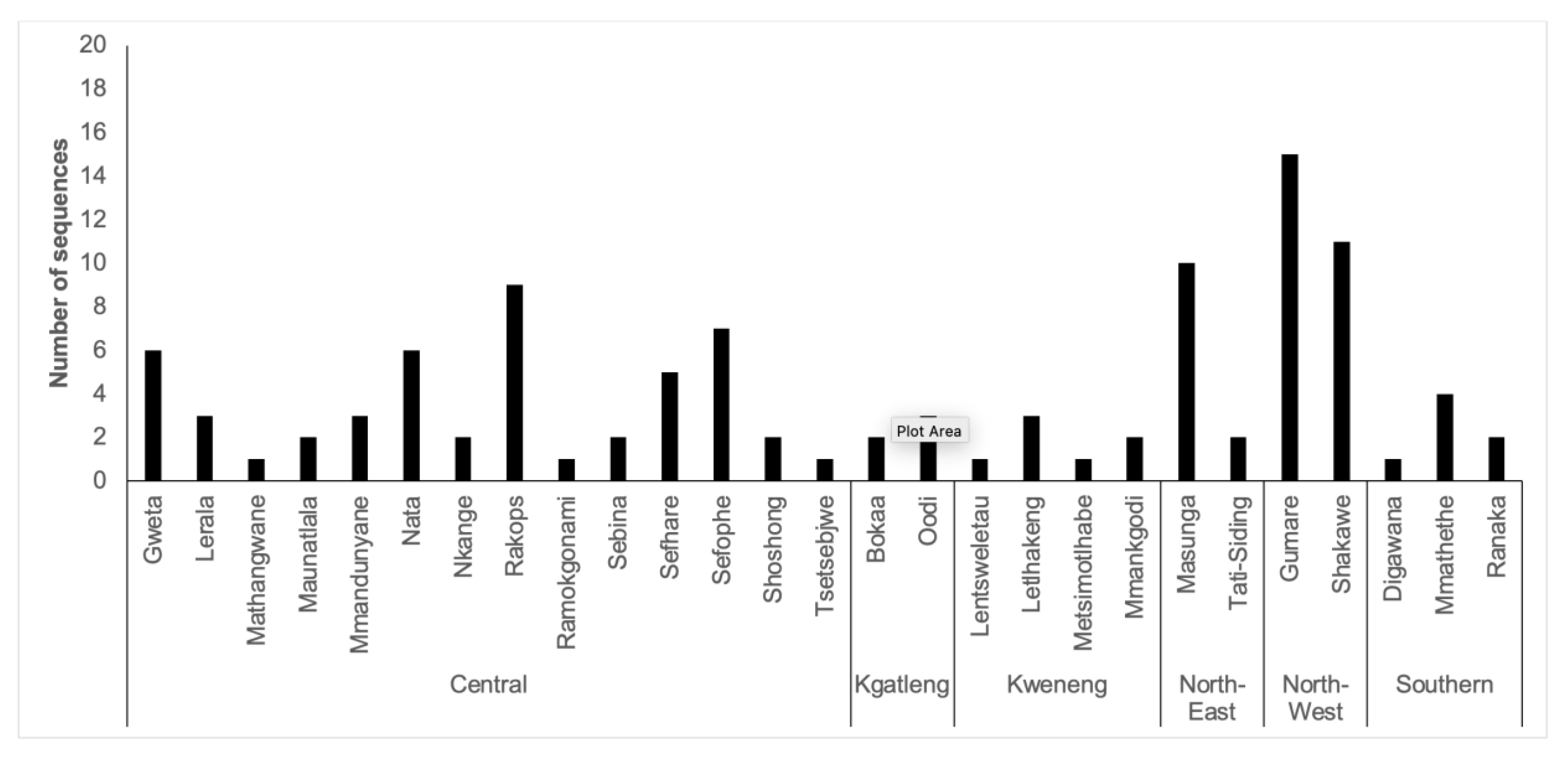

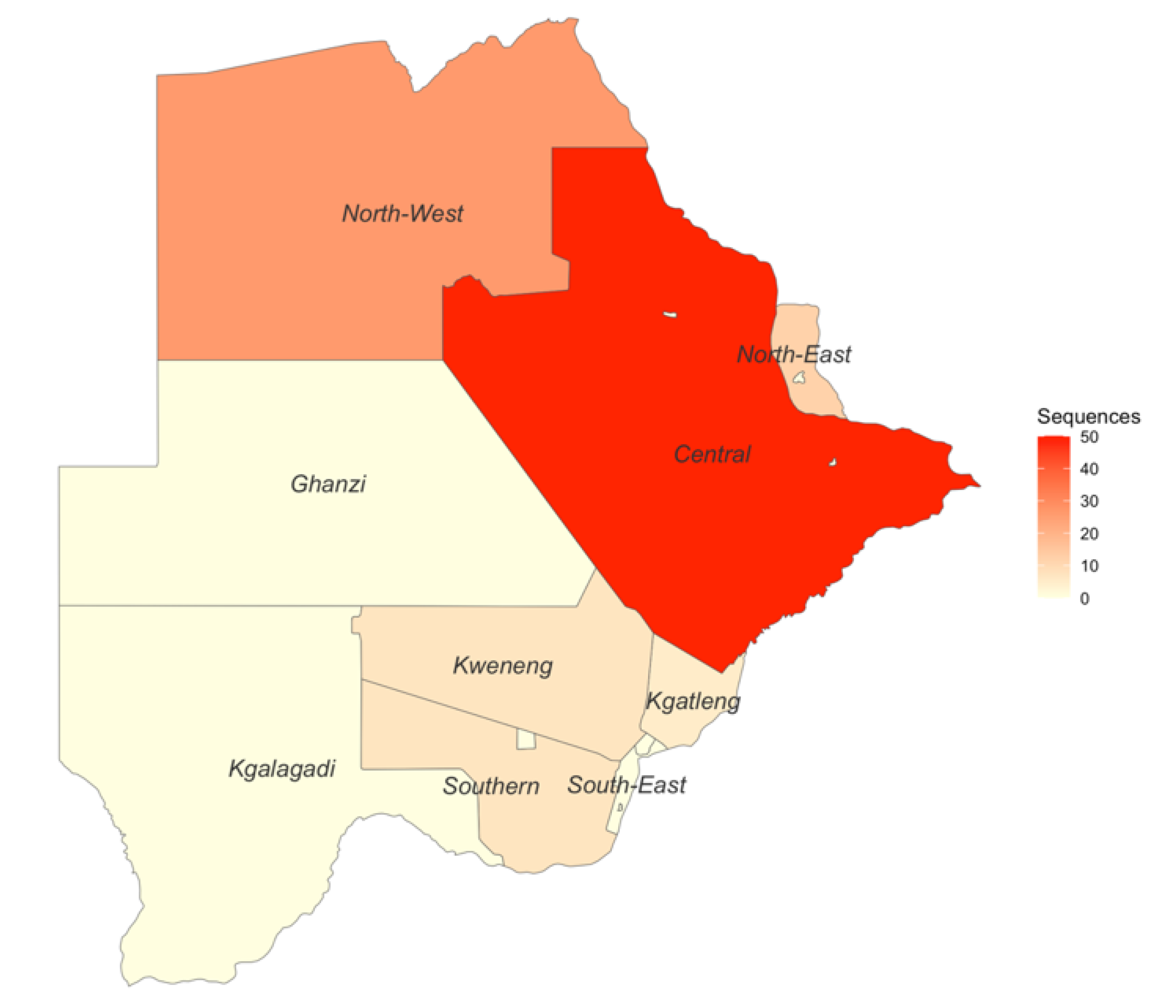

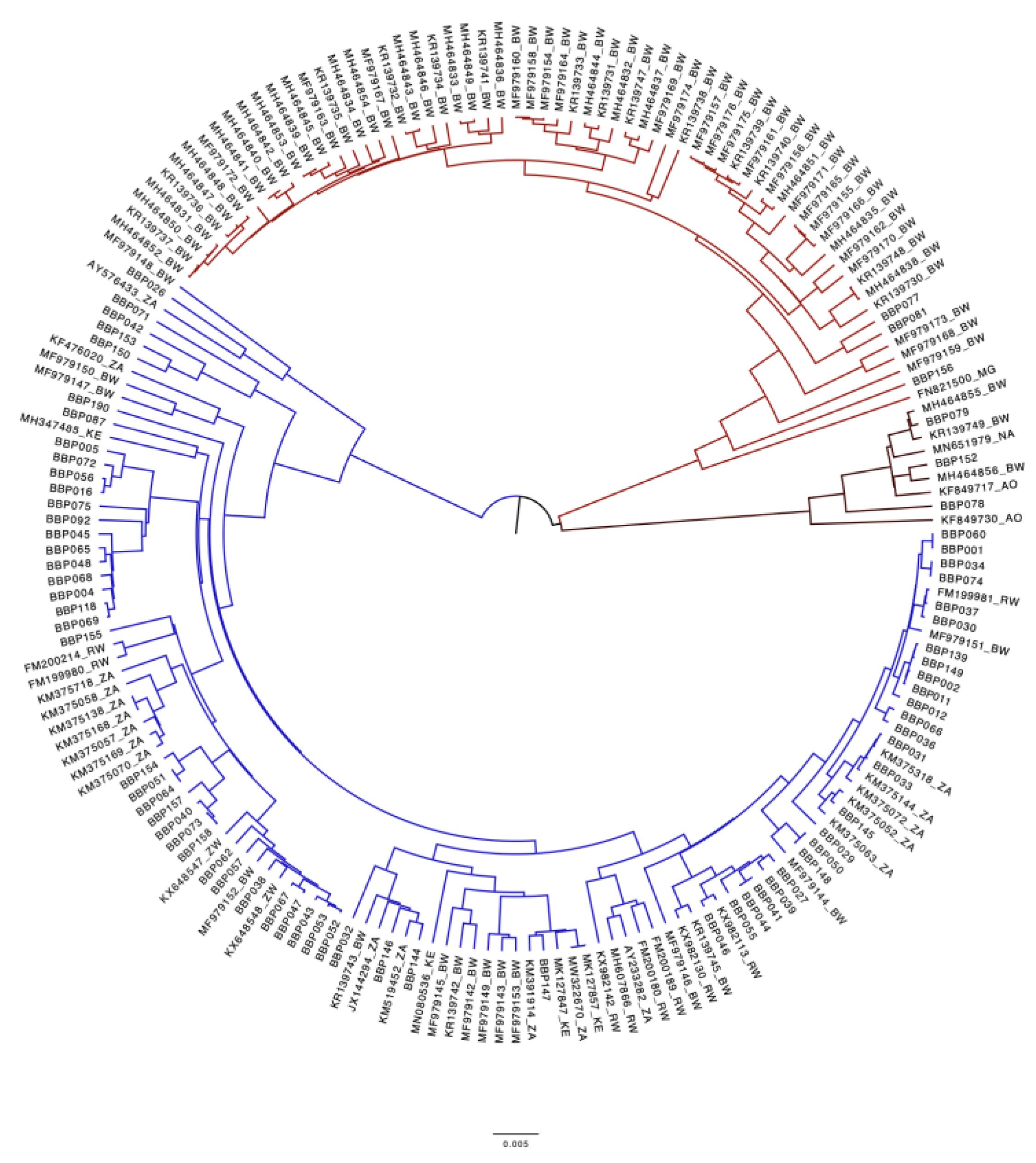

3.3. Genotypic Analysis

3.4. Mutational Analysis

3.4.1. Escape Mutations

3.4.2. Comparison of Botswana reference HBV sequences and BCPP HBV sequences.

3.4.3. Impact of Occult-Associated Mutations on Protein Function

| ORF | Mutation | PROVEAN Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Core | coreT142S | Neutral |

| Terminal protein | tpE88R | Neutral |

| tpQ6H | Deleterious | |

| Surface | surfaceV194A | Neutral |

| surfaceS55P | Deleterious | |

| Reverse transcriptase | rtM250L | Neutral |

| Precore | preCW28L | Deleterious |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Primer Name | Sequence | Positions |

|---|---|---|

| SC_1_LEFT | TTCCACCAAGCTCTGCAAGATC | 11 - 32 |

| SC_1_RIGHT | AGAGGAATATGATAAAACGCCGCA | 384-407 |

| SC_2_LEFT | CTCCAATCACTCACCAACCTCC | 325-346 |

| SC_2_RIGHT | AAAGCCCTACGAACCACTGAAC | 692-713 |

| SC_3_LEFT | AAATACCTATGGGAGTGGGCCT | 632-653 |

| SC_3_RIGHT | TTGTGTAAATGGAGCGGCAAAG | 1655-1676 |

| SC_4_LEFT | AGAAAACTTCCTGTTAACAGACCTATTG | 949-976 |

| SC_4_RIGHT | GGACGACAGAATTATCAGTCCCG | 1326-1348 |

| SC_5_LEFT | TCCATACTGCGGAACTCCTAGC | 1265-1286 |

| SC_5_RIGHT | TGTAAGACCTTGGGCAGGATTTG | 1632-1654 |

| SC_6_LEFT | CTTCTCATCTGCCGGTCCGTGT | 1559-1580 |

| SC_6_RIGHT | AGAAGTCAGAAGGCAAAAACGAGA | 1947-1970 |

| SC_7_LEFT | GGCTTTGGGGCATGGACATT | 1890-1909 |

| SC_7_RIGHT | ATCCACACTCCGAAAGAGACCA | 2256-2277 |

| SC_8_LEFT | GACAACTATTGTGGTTTCATATTTCT | 2193-2218 |

| SC_8_RIGHT | TTGTTGACACCTATTAATAATGTCCTCA | 2576-2594 |

| SC_9_LEFT | TGGGCTTTATTCCTCTACTGTCCC | 2492-2515 |

| SC_9_RIGHT | GGGAACAGAAAGATTCGTCCCC | 2889-2910 |

| SC_10_LEFT | TTGCGGGTCACCATATTCTTGG | 2816-2837 |

| SC_10_RIGHT | GGCCTGAGGATGACTGTCTCTT | 3189-3210 |

| REFERENCE SEQUENCES | BCPP SEQUENCES | COMMON MUTATIONS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | Frequency | Prevalence | Mutation | Frequency | Prevalence | REF | BCPP | ||

| PreS1 | S5P | 3 | 8.1% | G35R | 12 | 12.1% | T94P | 44.4% | 50.5% |

| A6S | 6 | 16.2% | N37Y | 15 | 15.2% | ||||

| K10N | 3 | 8.1% | I48V | 21 | 21.2% | ||||

| F25L | 5 | 13.5% | A90V | 23 | 23.2% | ||||

| V74F | 2 | 5.4% | |||||||

| I84V | 5 | 13.5% | |||||||

| A86T | 2 | 5.4% | |||||||

| V88L | 3 | 8.1% | |||||||

| A90T | 6 | 16.2% | |||||||

| A90P | 9 | 24.3% | |||||||

| V91S | 5 | 13.5% | |||||||

| P92L | 4 | 11.1% | |||||||

| P92S | 5 | 13.9% | |||||||

| P93S | 4 | 11.1% | |||||||

| PreS2 | V17I | 2 | 5.3% | Y21C | 2 | 2.2% | A7T | 5.3% | 16.9% |

| Y21S | 2 | 5.1% | L32V | 8 | 9.0% | A11T | 5.3% | 10.3% | |

| F22L | 3 | 7.7% | N37T | 7 | 7.9% | T38I | 41.0% | 30.3% | |

| R48T | 5 | 12.8% | A39V | 9 | 10.1% | A53V | 12.8% | 4.5% | |

| H41P | 2 | 2.2% | L54P | 15.4% | 14.6% | ||||

| H41L | 3 | 3.4% | |||||||

| I45T | 18 | 20.2% | |||||||

| S46F | 8 | 9.0% | |||||||

| S47L | 2 | 2.2% | |||||||

| T49I | 6 | 6.7% | |||||||

| D51V | 6 | 6.7% | |||||||

| L54S | 21 | 23.6% | |||||||

| preC | C14Y | 2 | 7.14% | None | |||||

| W28L | 3 | 10.71% | |||||||

| V17F | 15 | 53.57% | |||||||

| Core | S35A | 2 | 8.3% | P45S | 8 | 9.8% | None | ||

| A41S | 2 | 8.3% | C61R | 2 | 2.4% | ||||

| C48G | 2 | 8.3% | G63R | 2 | 2.4% | ||||

| E64D | 3 | 12.5% | E64K | 3 | 3.7% | ||||

| L65V | 3 | 12.5% | M66T | 2 | 2.4% | ||||

| T67N | 4 | 16.7% | N74I | 3 | 3.7% | ||||

| N74S | 2 | 8.3% | S106F | 2 | 2.4% | ||||

| E77D | 2 | 8.3% | T142S | 2 | 2.7% | ||||

| A131P | 3 | 12.5% | V148A | 2 | 2.7% | ||||

| R151C | 4 | 16.7% | R181P | 3 | 3.7% | ||||

| D153A | 3 | 12.5% | |||||||

| S183P | 2 | 8.3% | |||||||

| X | E80A | 2 | 8.3% | L5V | 16 | 26.7% | S11P | 12.5% | 18.3% |

| I88S | 2 | 8.3% | Y6C | 9 | 15.0% | G22S | 8.3% | 43.8% | |

| K130M | 3 | 15.8% | S12A | 11 | 18.3% | A31T | 8.3% | 28.1% | |

| V131I | 4 | 21.1% | R26C | 13 | 20.3% | S46P | 41.7% | 67.2% | |

| P29S | 17 | 26.6% | |||||||

| A31S | 8 | 12.5% | |||||||

| G32R | 8 | 12.5% | |||||||

| P33S | 27 | 42.2% | |||||||

| T36G | 3 | 4.7% | |||||||

| T36A | 14 | 21.9% | |||||||

| S47A | 5 | 7.8% | |||||||

| D48V | 6 | 9.4% | |||||||

| C78R | 8 | 12.7% | |||||||

| A85S | 2 | 3.4% | |||||||

| L93S | 2 | 4.3% | |||||||

| V116L | 2 | 4.3% | |||||||

| S147P | 2 | 4.3% | |||||||

| Surface | M1R | 2 | 5.4% | N3S | 3 | 3.5% | T114S | 3.4% | 2.2% |

| S45P | 3 | 8.1% | G7R | 3 | 3.5% | K122R | 2.3% | 10.1% | |

| L49R | 2 | 5.4% | F8L | 2 | 2.3% | N131T | 14.8% | 2.2% | |

| L98V | 3 | 3.4% | R24K | 4 | 4.5% | V194A | 37.5% | 5.7% | |

| M103I | 3 | 3.4% | G44S | 2 | 2.3% | ||||

| P111A | 3 | 3.4% | S45T | 2 | 2.3% | ||||

| S117R | 2 | 2.3% | S45A | 4 | 4.5% | ||||

| Q129R | 4 | 4.5% | P46T | 3 | 3.4% | ||||

| G130N | 2 | 2.3% | S55P | 9 | 10.2% | ||||

| T140I | 2 | 2.3% | T57I | 5 | 5.6% | ||||

| A159V | 5 | 5.7% | V96A | 9 | 10.1% | ||||

| E164G | 4 | 4.5% | Q101K | 2 | 2.2% | ||||

| V168A | 2 | 2.3% | W156Q | 2 | 2.3% | ||||

| L173P | 3 | 3.4% | A159I | 2 | 2.3% | ||||

| V184A | 4 | 4.5% | E164D | 25 | 28.7% | ||||

| S204N | 8 | 9.1% | F179L | 2 | 2.3% | ||||

| V180A | 6 | 6.9% | |||||||

| W182R | 2 | 2.3% | |||||||

| F183S | 3 | 3.5% | |||||||

| V184L | 2 | 2.7% | |||||||

| G185W | 2 | 2.7% | |||||||

| I195M | 39 | 55.7% | |||||||

| W199R | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| Y200C | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| P203Q | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| Y206H | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| Y206R | 3 | 4.3% | |||||||

| I213M | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| P214L | 4 | 5.7% | |||||||

| REFERENCE SEQUENCES | BCPP SEQUENCES | COMMON MUTATIONS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | Frequency | Prevalence | Mutation | Frequency | Prevalence | REF | BCPP | ||

| TP | D16A | 3 | 7.7% | Q6H | 2 | 2.8% | V71I | 28.2% | 34.7% |

| T18L | 3 | 7.7% | A20V | 2 | 2.8% | Q87H | 53.8% | 47.2% | |

| V71N | 4 | 10.3% | A20G | 2 | 2.8% | H182Q | 5.1% | 21.7% | |

| E75D | 4 | 10.3% | L23P | 2 | 2.8% | ||||

| N120K | 2 | 5.1% | D32G | 2 | 2.8% | ||||

| S121G | 2 | 5.1% | A40I | 2 | 2.8% | ||||

| K161Q | 2 | 5.1% | G46Q | 2 | 2.8% | ||||

| L181I | 3 | 7.7% | W54L | 2 | 2.8% | ||||

| F61L | 2 | 2.8% | |||||||

| S80P | 2 | 2.8% | |||||||

| P82H | 2 | 2.8% | |||||||

| E88R | 2 | 2.8% | |||||||

| I91S | 13 | 18.1% | |||||||

| R93K | 2 | 2.8% | |||||||

| Q95E | 2 | 2.8% | |||||||

| M113I | 2 | 2.8% | |||||||

| D128N | 2 | 2.8% | |||||||

| Q138H | 15 | 20.8% | |||||||

| L153T | 2 | 3.8% | |||||||

| G157R | 2 | 3.8% | |||||||

| R162K | 2 | 3.8% | |||||||

| S167G | 2 | 4.3% | |||||||

| Spacer | V4A | 3 | 7.9% | S15P | 7 | 11.9% | P64A | 44.7% | 36.3% |

| S5I | 6 | 15.8% | S18P | 12 | 20.3% | I84T | 13.2% | 12.1% | |

| Q6K | 15 | 39.5% | V29I | 6 | 6.7% | Y86H | 13.2% | 26.4% | |

| A7T | 23 | 60.5% | R34Q | 11 | 12.2% | H93S | 44.7% | 45.1% | |

| R10W | 3 | 7.9% | Q36L | 15 | 16.7% | S125N | 5.6% | 22.9% | |

| Q19K | 5 | 13.2% | H47R | 19 | 20.9% | S129N | 5.3% | 12.3% | |

| P20S | 2 | 5.3% | R63W | 2 | 2.2% | ||||

| L24P | 5 | 13.2% | F74L | 2 | 2.2% | ||||

| V29T | 3 | 7.9% | S91A | 11 | 12.1% | ||||

| P46S | 3 | 7.9% | H93P | 2 | 2.2% | ||||

| P56S | 4 | 10.5% | K102E | 3 | 3.3% | ||||

| H83R | 5 | 13.2% | F126I | 4 | 8.2% | ||||

| G85D | 2 | 5.3% | P127S | 12 | 23.1% | ||||

| S87I | 2 | 5.3% | P128S | 5 | 9.6% | ||||

| S89N | 6 | 15.8% | S130F | 2 | 3.2% | ||||

| S89T | 9 | 23.7% | A131S | 9 | 12.7% | ||||

| S90K | 5 | 13.2% | Q136E | 2 | 2.5% | ||||

| S91F | 5 | 13.2% | Q136K | 5 | 6.2% | ||||

| S92L | 3 | 7.9% | G137R | 12 | 14.5% | ||||

| L108F | 3 | 8.1% | P138L | 2 | 2.4% | ||||

| V121M | 2 | 5.4% | S141P | 3 | 3.6% | ||||

| F123L | 2 | 5.6% | T150I | 2 | 2.2% | ||||

| S129G | 2 | 5.4% | T150S | 7 | 7.9% | ||||

| S135N | 2 | 5.4% | Q151E | 5 | 5.6% | ||||

| F140S | 4 | 10.5% | K155D | 6 | 6.7% | ||||

| L158I | 10 | 26.3% | S159T | 4 | 4.5% | ||||

| L161I | 2 | 5.3% | |||||||

| RT | E1D | 5 | 12.5% | V7T | 2 | 2.3% | V7A | 40.0% | 16.3% |

| H9Q | 3 | 7.5% | E11K | 3 | 3.5% | L53I | 35.0% | 11.4% | |

| S105T | 5 | 12.5% | R15K | 3 | 3.5% | I103V | 37.5% | 23.5% | |

| S106C | 3 | 7.5% | I16T | 2 | 2.3% | P109S | 20.0% | 14.1% | |

| R110G | 12 | 30.0% | A21T | 2 | 2.3% | H122N | 35.0% | 2.4% | |

| S119C | 3 | 7.5% | R51G | 2 | 2.3% | W153R | 7.5% | 19.0% | |

| Q139H | 12 | 30.0% | G52E | 2 | 2.3% | K266V | 27.5% | 14.5% | |

| R242K | 3 | 7.5% | L53N | 2 | 2.3% | K266I | 65.0% | 65.2% | |

| H271P | 2 | 5.0% | L53S | 2 | 2.3% | N332S | 39.3% | 15.9% | |

| H271S | 3 | 7.5% | T54Y | 2 | 2.3% | Q333K | 44.4% | 14.5% | |

| H271C | 13 | 32.5% | T54S | 4 | 4.5% | ||||

| T322I | 3 | 9.1% | V63A | 7 | 8.0% | ||||

| H122L | 2 | 2.4% | |||||||

| N124H | 19 | 22.4% | |||||||

| Y126H | 20 | 23.5% | |||||||

| L129M | 2 | 2.4% | |||||||

| N131D | 16 | 18.8% | |||||||

| Y151F | 2 | 2.4% | |||||||

| R167H | 2 | 2.4% | |||||||

| V173L | 23 | 27.4% | |||||||

| L180M | 41 | 47.1% | |||||||

| I187A | 2 | 2.3% | |||||||

| V190A | 2 | 2.3% | |||||||

| R192S | 2 | 2.8% | |||||||

| R192L | 3 | 4.2% | |||||||

| R193V | 2 | 2.8% | |||||||

| M204V | 37 | 53.6% | |||||||

| V207A | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| V214A | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| T222A | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| A223V | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| T225A | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| L229F | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| N238T | 9 | 13.0% | |||||||

| S246F | 3 | 4.3% | |||||||

| M250L | 4 | 5.8% | |||||||

| V253I | 10 | 14.5% | |||||||

| S256G | 6 | 8.7% | |||||||

| T259S | 8 | 11.6% | |||||||

| Q262R | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| I282V | 8 | 11.6% | |||||||

| C287Y | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| R289E | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| R289K | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| I290F | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| Y312H | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| M336V | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| Y339C | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| Y339L | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| RNaseH | V138D | 3 | 12.50% | R1Q | 2 | 9.5% | S2P | 41.7% | 61.9% |

| C5M | 2 | 9.5% | Y116F | 8.3% | 30.0% | ||||

| T37A | 2 | 9.1% | R151K | 8.3% | 7.8% | ||||

| A38T | 2 | 9.1% | |||||||

| K53N | 2 | 4.1% | |||||||

| L54I | 2 | 3.7% | |||||||

| G75S | 3 | 4.7% | |||||||

| T77A | 10 | 15.6% | |||||||

| G84R | 2 | 3.1% | |||||||

| A93V | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| P100L | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| L107V | 4 | 5.7% | |||||||

| Y108S | 3 | 4.3% | |||||||

| R113S | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| L114P | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| P115L | 5 | 7.1% | |||||||

| R117H | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| R117C | 2 | 2.9% | |||||||

| R117Q | 6 | 8.6% | |||||||

| T119S | 8 | 11.4% | |||||||

| V128D | 18 | 25.7% | |||||||

| F142S | 3 | 4.3% | |||||||

| V148A | 24 | 36.9% | |||||||

References

- WHO. Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low- and middle-income countries; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2024.

- Phinius, B.B.; Anderson, M.; Gobe, I.; Mokomane, M.; Choga, W.T.; Mutenga, S.R.; Mpebe, G.; Pretorius-Holme, M.; Musonda, R.; Gaolathe, T.; et al. High Prevalence of Hepatitis B Virus Infection Among People With HIV in Rural and Periurban Communities in Botswana. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023, 10, ofac707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbangiwa, T.; Kasvosve, I.; Anderson, M.; Thami, P.K.; Choga, W.T.; Needleman, A.; Phinius, B.B.; Moyo, S.; Leteane, M.; Leidner, J.; et al. Chronic and Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Pregnant Women in Botswana. Genes (Basel) 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, K.; Anderson, M.; Gyurova, I.; Ambroggio, L.; Moyo, S.; Sebunya, T.; Makhema, J.; Marlink, R.; Essex, M.; Musonda, R.; et al. High Rates of Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection in HIV-Positive Individuals Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy in Botswana. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017, 4, ofx195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondo, G.; Pollicino, T.; Cacciola, I.; Squadrito, G. Occult hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol 2007, 46, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Hamada-Tsutsumi, S.; Okuse, C.; Sakai, A.; Matsumoto, N.; Sato, M.; Sato, T.; Arito, M.; Omoteyama, K.; Suematsu, N.; et al. Effects of vaccine-acquired polyclonal anti-HBs antibodies on the prevention of HBV infection of non-vaccine genotypes. J Gastroenterol 2017, 52, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Liao, Y.; Chen, J.; Cai, B.; Su, Z.; Ying, B.; Lu, X.; Tao, C.; Wang, L. Epidemiology study of HBV genotypes and antiviral drug resistance in multi-ethnic regions from Western China. Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 17413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, J.H.; Chen, P.J.; Lai, M.Y.; Chen, D.S. Hepatitis B genotypes correlate with clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 2000, 118, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, J.H.; Liu, C.J.; Chen, D.S. Hepatitis B viral genotypes and lamivudine resistance. J Hepatol 2002, 36, 303–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.; Choga, W.T.; Moyo, S.; Bell, T.G.; Mbangiwa, T.; Phinius, B.B.; Bhebhe, L.; Sebunya, T.K.; Lockman, S.; Marlink, R.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Near Full-Length Genomes of Hepatitis B Virus Isolated from Predominantly HIV Infected Individuals in Botswana. Genes (Basel) 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choga, W.T.; Anderson, M.; Zumbika, E.; Moyo, S.; Mbangiwa, T.; Phinius, B.B.; Melamu, P.; Kayembe, M.K.; Kasvosve, I.; Sebunya, T.K.; et al. Molecular characterization of hepatitis B virus in blood donors in Botswana. Virus Genes 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruti, K.; Lentz, K.; Anderson, M.; Ajibola, G.; Phinius, B.B.; Choga, W.T.; Mbangiwa, T.; Powis, K.M.; Sebunya, T.; Blackard, J.T.; et al. Hepatitis B virus prevalence and vaccine antibody titers in children HIV exposed but uninfected in Botswana. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0237252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaver, Z.M.; Anderson, M.; Bhebhe, L.; Baruti, K.; Choga, W.T.; Ngidi, J.; Mbangiwa, T.; Tau, M.; Setlhare, D.R.; Melamu, P.; et al. Decreased hepatitis B virus vaccine response among HIV-positive infants compared with HIV-negative infants in Botswana. AIDS 2022, 36, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phinius, B.B.; Anderson, M.; Gobe, I.; Mokomane, M.; Choga, W.T.; Mokomane, M.; Choga, W.T.; Mpebe, G.; Makhema, J.; Shapiro, R.; et al. High Prevalence of Hepatitis B Virus Drug Resistance Mutations to Lamivudine Among People with HIV/HBV Coinfection in Rural and Peri-Urban Communities in Botswana. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinius, B.B.; Anderson, M.; Gobe, I.; Mokomane, M.; Choga, W.T.; Phakedi, B.; Ratsoma, T.; Mpebe, G.; Makhema, J.; Shapiro, R.; et al. High Prevalence of Hepatitis B Virus Drug Resistance Mutations to Lamivudine among People with HIV/HBV Coinfection in Rural and Peri-Urban Communities in Botswana. Viruses 2024, 16, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Hollinger, F.B. Occult hepatitis B virus infection and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. J Viral Hepat 2014, 21, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilard, A.; Andersson, M.; Ringlander, J.; Wejstal, R.; Norkrans, G.; Lindh, M. Vertically acquired occult hepatitis B virus infection may become overt after several years. J Infect 2019, 78, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.; Choga, W.T.; Moyo, S.; Bell, T.G.; Mbangiwa, T.; Phinius, B.B.; Bhebhe, L.; Sebunya, T.K.; Makhema, J.; Marlink, R.; et al. In Silico Analysis of Hepatitis B Virus Occult Associated Mutations in Botswana Using a Novel Algorithm. Genes (Basel) 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olagbenro, M.; Anderson, M.; Gaseitsiwe, S.; Powell, E.A.; Gededzha, M.P.; Selabe, S.G.; Blackard, J.T. In silico analysis of mutations associated with occult hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in South Africa. Arch Virol 2021, 166, 3075–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phinius, B.B.; Anderson, M.; Bhebhe, L.; Baruti, K.; Manowe, G.; Choga, W.T.; Mupfumi, L.; Mbangiwa, T.; Mudanga, M.; Moyo, S.; et al. Increased Prevalence of Liver Fibrosis and HIV Viremia among Patients with HIV, HBV, and Tuberculosis in Botswana. Pathogens 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaolathe, T.; Wirth, K.E.; Holme, M.P.; Makhema, J.; Moyo, S.; Chakalisa, U.; Yankinda, E.K.; Lei, Q.; Mmalane, M.; Novitsky, V.; et al. Botswana’s progress toward achieving the 2020 UNAIDS 90-90-90 antiretroviral therapy and virological suppression goals: a population-based survey. Lancet HIV 2016, 3, e221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhema, J.; Wirth, K.E.; Pretorius Holme, M.; Gaolathe, T.; Mmalane, M.; Kadima, E.; Chakalisa, U.; Bennett, K.; Leidner, J.; Manyake, K.; et al. Universal Testing, Expanded Treatment, and Incidence of HIV Infection in Botswana. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choga, W. Complete Hepatitis B Virus Sequencing using an ONT-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Protocol; 2023.

- Phinius, B.B.; Anderson, M.; Mokomane, M.; Gobe, I.; Choga, W.T.; Ratsoma, T.; Phakedi, B.; Mpebe, G.; Ditshwanelo, D.; Musonda, R.; et al. Atypical Hepatitis B Virus Serology Profile-Hepatitis B Surface Antigen-Positive/Hepatitis B Core Antibody-Negative-In Hepatitis B Virus/HIV Coinfected Individuals in Botswana. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ONT. PCR Tiling of Sars Cov 2 Virus With Rapid Barcoding SQK rbk110 PCTR - 9125 - v110 - Revh - 24mar2021 Minion. Available online: https://community.nanoporetech.com/docs/prepare/library_prep_protocols/pcr-tiling-of-sars-cov-2-virus-with-rapid-barcoding-and-midnight/v/mrt_9127_v110_revw_14jul2021 (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Vilsker, M.; Moosa, Y.; Nooij, S.; Fonseca, V.; Ghysens, Y.; Dumon, K.; Pauwels, R.; Alcantara, L.C.; Vanden Eynden, E.; Vandamme, A.M.; et al. Genome Detective: an automated system for virus identification from high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 871–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, A. AliView: a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3276–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.; Gaseitsiwe, S.; Moyo, S.; Wessels, M.J.; Mohammed, T.; Sebunya, T.K.; Powell, E.A.; Makhema, J.; Blackard, J.T.; Marlink, R.; et al. Molecular characterisation of hepatitis B virus in HIV-1 subtype C infected patients in Botswana. BMC Infect Dis 2015, 15, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwei, K.; Tang, X.; Lok, A.S.; Sureau, C.; Garcia, T.; Li, J.; Wands, J.; Tong, S. Impaired virion secretion by hepatitis B virus immune escape mutants and its rescue by wild-type envelope proteins or a second-site mutation. J Virol 2013, 87, 2352–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konopleva, M.V.; Belenikin, M.S.; Shanko, A.V.; Bazhenov, A.I.; Kiryanov, S.A.; Tupoleva, T.A.; Sokolova, M.V.; Pronin, A.V.; Semenenko, T.A.; Suslov, A.P. Detection of S-HBsAg Mutations in Patients with Hematologic Malignancies. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.L.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.H. Genetic variation of occult hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22, 3531–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, Z.; Qin, L.; Lu, M.; Yang, D. The amino Acid residues at positions 120 to 123 are crucial for the antigenicity of hepatitis B surface antigen. J Clin Microbiol 2007, 45, 2971–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.G.; Ueda, K. A meta-analysis on genetic variability of RT/HBsAg overlapping region of hepatitis B virus (HBV) isolates of Bangladesh. Infect Agent Cancer 2019, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.M.; Welge, J.A.; Rouster, S.D.; Shata, M.T.; Sherman, K.E.; Blackard, J.T. Mutations associated with occult hepatitis B virus infection result in decreased surface antigen expression in vitro. J Viral Hepat 2012, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong-Lin, Y.; Qiang, F.; Ming-Shun, Z.; Jie, C.; Gui-Ming, M.; Zu-Hu, H.; Xu-Bing, C. Hepatitis B surface antigen variants in voluntary blood donors in Nanjing, China. Virol J 2012, 9, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Li, F.; Guo, H.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, J.; Mao, R.; Qin, Y.; Xu, J.; et al. Amino acid substitutions Q129N and T131N/M133T in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) interfere with the immunogenicity of the corresponding HBsAg or viral replication ability. Virus Research 2018, 257, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, P.J.; Zhang, Y.L.; Chen, C.R.; Zheng, Q.B.; Yeh, S.H.; Yu, H.; Xue, Y.; Chen, Y.X.; et al. Influence of mutations in hepatitis B virus surface protein on viral antigenicity and phenotype in occult HBV strains from blood donors. J Hepatol 2012, 57, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Wang, Y. Comprehensive analysis of the prevalence of hepatitis B virus escape mutations in the major hydrophilic region of surface antigen. J Med Virol 2012, 84, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.N.; Oon, C.J. Changes in the antigenicity of a hepatitis B virus mutant stemming from lamivudine therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000, 44, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodadad, N.; Seyedian, S.S.; Moattari, A.; Biparva Haghighi, S.; Pirmoradi, R.; Abbasi, S.; Makvandi, M. In silico functional and structural characterization of hepatitis B virus PreS/S-gene in Iranian patients infected with chronic hepatitis B virus genotype D. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colagrossi, L.; Hermans, L.E.; Salpini, R.; Di Carlo, D.; Pas, S.D.; Alvarez, M.; Ben-Ari, Z.; Boland, G.; Bruzzone, B.; Coppola, N.; et al. Immune-escape mutations and stop-codons in HBsAg develop in a large proportion of patients with chronic HBV infection exposed to anti-HBV drugs in Europe. BMC Infect Dis 2018, 18, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, F.; Slanina, H.; Roderfeld, M.; Roeb, E.; Trebicka, J.; Ziebuhr, J.; Gerlich, W.H.; Schüttler, C.G.; Schlevogt, B.; Glebe, D. A Novel Insertion in the Hepatitis B Virus Surface Protein Leading to Hyperglycosylation Causes Diagnostic and Immune Escape. Viruses 2023, 15, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokaya, J.; McNaughton, A.L.; Hadley, M.J.; Beloukas, A.; Geretti, A.M.; Goedhals, D.; Matthews, P.C. A systematic review of hepatitis B virus (HBV) drug and vaccine escape mutations in Africa: A call for urgent action. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018, 12, e0006629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, X.; Tong, S. Impact of immune escape mutations and N-linked glycosylation on the secretion of hepatitis B virus virions and subviral particles: Role of the small envelope protein. Virology 2018, 518, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adesina, O.A.; Akanbi, O.A.; Opaleye, O.O.; Japhet, M.O.; Wang, B.; Oluyege, A.O.; Klink, P.; Bock, C.T. Detection of Q129H Immune Escape Mutation in Apparently Healthy Hepatitis B Virus Carriers in Southwestern Nigeria. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshkar, S.T.; Patil, N.B.; Lad, A.A.; Papal, N.S.; S. , S.S. Monitoring of hepatitis B virus surface antigen escape mutations and concomitant nucleostide analog resistance mutations in patients with chronic hepatitis B. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2022, 10, 2261–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarevic, I. Clinical implications of hepatitis B virus mutations: recent advances. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20, 7653–7664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooreman, M.P.; Leroux-Roels, G.; Paulij, W.P. Vaccine- and hepatitis B immune globulin-induced escape mutations of hepatitis B virus surface antigen. J Biomed Sci 2001, 8, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencay, M.; Hübner, K.; Gohl, P.; Seffner, A.; Weizenegger, M.; Neofytos, D.; Batrla, R.; Woeste, A.; Kim, H.S.; Westergaard, G.; et al. Ultra-deep sequencing reveals high prevalence and broad structural diversity of hepatitis B surface antigen mutations in a global population. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0172101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Wu, C.C.; Chen, X.W.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Lu, M.J. Genetic variation of hepatitis B virus and its significance for pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enriquez-Navarro, K.; Maldonado-Rodriguez, A.; Rojas-Montes, O.; Torres-Ibarra, R.; Bucio-Ortiz, L.; De la Cruz, M.A.; Torres-Flores, J.; Xoconostle-Cazares, B.; Lira, R. Identification of mutations in the S gene of hepatitis B virus in HIV positive Mexican patients with occult hepatitis B virus infection. Annals of Hepatology 2020, 19, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, R.K.; Khatun, M.; Banerjee, P.; Ghosh, A.; Sarkar, S.; Santra, A.; Das, K.; Chowdhury, A.; Banerjee, S.; Datta, S. Synergistic impact of mutations in Hepatitis B Virus genome contribute to its occult phenotype in chronic Hepatitis C Virus carriers. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 9653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, M.F.; González, C.; Gregori, J.; Casillas, R.; Carioti, L.; Guerrero-Murillo, M.; Riveiro-Barciela, M.; Godoy, C.; Sopena, S.; Yll, M.; et al. Sophisticated viral quasispecies with a genotype-related pattern of mutations in the hepatitis B X gene of HBeAg-ve chronically infected patients. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ave, A.R.; Putra, A.E.; Miro, S. Gene X Two Triple Mutations Predominance on Chronic Hepatitis B Virus in Padang, West Sumatra, Indonesia. The Indonesian Journal of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Digestive Endoscopy 2022, 23, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, H.G. Key role of hepatitis B virus mutation in chronic hepatitis B development to hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2015, 7, 1282–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, Z.; Xu, J. X protein mutations in hepatitis B virus DNA predict postoperative survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol 2014, 35, 10325–10331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, D.N.; Flanagan, J.M.; Hu, J. Mapping of Functional Subdomains in the Terminal Protein Domain of Hepatitis B Virus Polymerase. J Virol 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherkhani, R.; Farshadpour, F. Prevalence, genotype distribution and mutations of hepatitis B virus and the associated risk factors among pregnant women residing in the northern shores of Persian Gulf, Iran. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0265063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.M.; Kim, B.S.; Tabor, E. Precore codon 28 stop mutation in hepatitis B virus from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J Intern Med 1997, 12, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudu, S.A.; Harmal, N.S.; Saeed, M.I.; Alshrari, A.S.; Malik, Y.A.; Niazlin, M.T.; Hassan, R.; Sekawi, Z. Naturally occurring hepatitis B virus surface antigen mutant variants in Malaysian blood donors and vaccinees. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2015, 34, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salpini, R.; Battisti, A.; Piermatteo, L.; Carioti, L.; Anastasiou, O.E.; Gill, U.S.; Di Carlo, D.; Colagrossi, L.; Duca, L.; Bertoli, A.; et al. Key mutations in the C-terminus of the HBV surface glycoprotein correlate with lower HBsAg levels in vivo, hinder HBsAg secretion in vitro and reduce HBsAg structural stability in the setting of HBeAg-negative chronic HBV genotype-D infection. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020, 9, 928–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, A.; Hassanshahi, G.H.; Ghalebi, S.R.; Jafarzadeh, A.; Mohit, M.; Hajghani, M.; Kazemi Arababadi, M. Intensity of HLA-A2 Expression Significantly Decreased in Occult Hepatitis B Infection. Jundishapur J Microbiol 2014, 7, e10298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arababadi, M.K.; Pourfathollah, A.A.; Jafarzadeh, A.; Hassanshahi, G. Serum Levels of IL-10 and IL-17A in Occult HBV-Infected South-East Iranian Patients. Hepat Mon 2010, 10, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Vivekanandan, P.; Kannangai, R.; Ray, S.C.; Thomas, D.L.; Torbenson, M. Comprehensive genetic and epigenetic analysis of occult hepatitis B from liver tissue samples. Clin Infect Dis 2008, 46, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Mu, S.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Z. Evidence that methylation of hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA in liver tissues of patients with chronic hepatitis B modulates HBV replication. J Med Virol 2009, 81, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, M.; Huang, J.; Xu, R.; Liao, Q.; Shan, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Rong, X.; Tang, X.; Li, T.; et al. Novel hepatitis B virus surface antigen mutations associated with occult genotype B hepatitis B virus infection affect HBsAg detection. J Viral Hepat 2020, 27, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Number (%) n=107 |

|---|---|

| Sex Female |

71 (66.4) |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 43 (36 – 49) |

| HBV type HBsAg+ OBI+ |

86 (80.4) 21 (19.6) |

| Total anti-HBc, n=104 Positive |

87 (83.7) |

| Anti-HBc IgM status*, n=81 Positive |

5 (6.2) |

| HBeAg status*, n=82 Positive |

15 (18.3) |

| HBV viral load Target not detected <2000 ≥2000 |

21 (19.6) 63 (58.9) 23 (21.5) |

| HIV viral load Undetectable Detectable |

95 (88.8) 12 (11.2) |

| ART status Naïve On ART |

6 (5.6) 101 (94.4) |

| ART regimen None 3TC/TDF-containing regimen 3TC-containing regimen TDF-containing regimen# Unknown |

1 (1.0) 27 (26.7) 45 (44.6) 28 (27.7) |

| Duration on ART, years, n=76, median (IQR) | 7.0 (4.7 – 9.9) |

| Mutation | Frequency | Genotype | HBV type | Reported impact | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T114S | 2 | A1 | HBsAg | Other substitutions at position 114 (R) reported to impair virion secretion | [29] |

| S114L | 1 | E | HBsAg | Other substitutions at position 114 (R) reported to impair virion secretion | [29] |

| T118M | 1 | A1 | OBI | Impair antigenicity, detection escape | [30] |

| C121R | 1 | A1 | OBI | Other substitutions at position 121 (S) reported to reduce antigenicity and impair HBsAg detection | [31,32] |

| K122R | 9 | A1 | HBsAg | Decreased HBsAg expression, detection failure | [33,34,35] |

| Q129C | 1 | A1 | OBI | Other Q129 (N) mutations lead to impaired antigenicity and immunogenicity, Q129R leads to impaired virion/S protein secretion, Q129H leads to decreased virion secretion | [29,36,37] |

| G130C | 1 | A1 | OBI | Other G130 mutations to lead to diagnostic escape, vaccine/ immunoglobulin therapy escape, altered antigenicity | [38,39] |

| N131T | 2 | A1 | HBsAg | Vaccine escape | [40] |

| T131N | 1 | D3 | HBsAg | Vaccine escape, diagnostic escape, hepatitis B immunoglobulin resistance | [41,42,43] |

| C137I | 1 | A1 | HBsAg | Other C137 mutations are reported to decrease antigenicity | [31] |

| C139R | 1 | A1 | HBsAg | Impair virion/S protein secretion | [37] |

| N146S | 1 | E | OBI | Impair virion secretion | [29,44] |

| C147Y | 1 | A1 | HBsAg | Impair virion secretion | [29] |

| REFERENCE SEQUENCES | BCPP SEQUENCES | COMMON MUTATIONS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | Frequency | Prevalence | Mutation | Frequency | Prevalence | Mutation | REFERENCE | BCPP | |

| PreS1 | A90P | 9/37 | 24.3% | I48V | 21/99 | 21.2% | T94P | 44.4% | 50.5% |

| A90V | 23/99 | 23.2% | |||||||

| PreS2 | None | I45T | 18/89 | 20.2% | A7T | 5.3% | 16.9% | ||

| L54S | 21/89 | 23.6% | A11T | 5.3% | 10.3% | ||||

| T38I | 41.0% | 30.3% | |||||||

| A53V | 12.8% | 4.5% | |||||||

| preC | None | V17F | 15/28 | 53.6% | None | ||||

| Core | None | None | None | ||||||

| X | V131I | 4/19 | 21.1% | R26C | 13/64 | 20.3% | S11P | 12.5% | 18.3% |

| P29S | 17/64 | 26.6% | G22S | 8.3% | 43.8% | ||||

| P33S | 27/64 | 42.2% | A31T | 8.3% | 28.1% | ||||

| T36A | 14/64 | 21.9% | S46P | 41.7% | 67.2% | ||||

| Surface | E164D | 25/87 | 28.7% | K122R | 2.3% | 10.1% | |||

| I195M | 39/70 | 55.7% | N131T | 14.8% | 2.2% | ||||

| V194A | 37.5% | 5.7% | |||||||

| BW REFRENCE SEQUENCES | BCPP REFERENCES | COMMON MUTATIONS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | Frequency | Prevalence | Mutation | Frequency | Prevalence | REFERENCE | BCPP | |||

| TP | Q138H | 15/72 | 20.8% | V71I | 28.2% | 34.7% | ||||

| Q87H | 53.8% | 47.2% | ||||||||

| H182Q | 5.1% | 21.7% | ||||||||

| Spacer | Q6K | 15/38 | 39.5% | S18P | 12/59 | 20.3% | P64A | 44.7% | 36.3% | |

| A7T | 23/38 | 60.5% | H47R | 19/91 | 20.9% | I84T | 13.2% | 12.1% | ||

| S89T | 9/38 | 23.7% | P127S | 12/52 | 23.1% | Y86H | 13.2% | 26.4% | ||

| L158I | 10/38 | 26.3% | H93S | 44.7% | 45.1% | |||||

| S125N | 5.6% | 22.9% | ||||||||

| S129N | 5.3% | 12.3% | ||||||||

| RT | R110G | 12/40 | 30.0% | N124H | 19/84 | 22.6% | V7A | 40.0% | 16.3% | |

| Q139H | 12/40 | 30.0% | Y126H | 20/84 | 23.8% | L53I | 35.0% | 11.4% | ||

| H271C | 13/40 | 32.5% | V173L | 23/84 | 27.4% | I103V | 37.5% | 23.5% | ||

| L180M | 41/87 | 47.1% | P109S | 20.0% | 14.1% | |||||

| M204V | 37/69 | 53.6% | H122N | 35.0% | 2.4% | |||||

| W153R | 7.5% | 19.0% | ||||||||

| K266V | 27.5% | 14.5% | ||||||||

| K266I | 65.0% | 65.2% | ||||||||

| N332S | 39.3% | 15.9% | ||||||||

| Q333K | 44.4% | 14.5% | ||||||||

| Rnase H | V128D | 18/70 | 25.7% | S2P | 41.7% | 61.9% | ||||

| V148A | 24/70 | 34.3% | Y116F | 8.3% | 30.0% | |||||

| R151K | 8.3% | 7.8% | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).