Submitted:

03 June 2024

Posted:

05 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

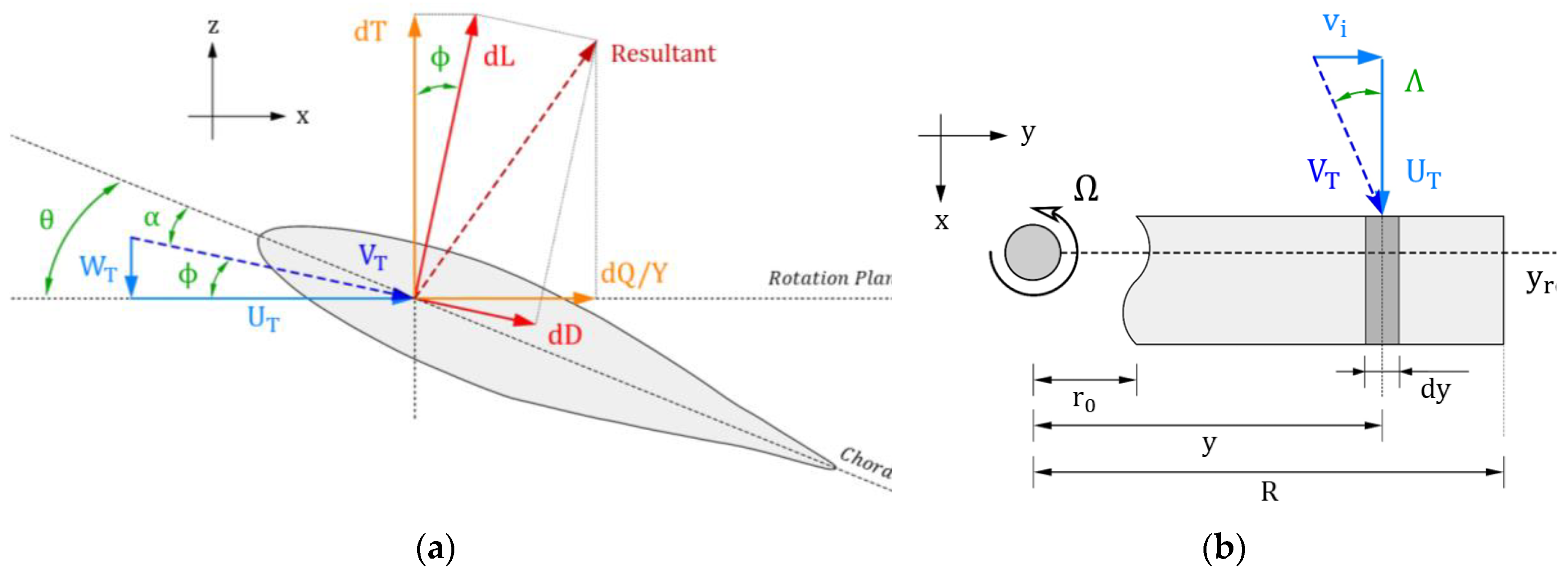

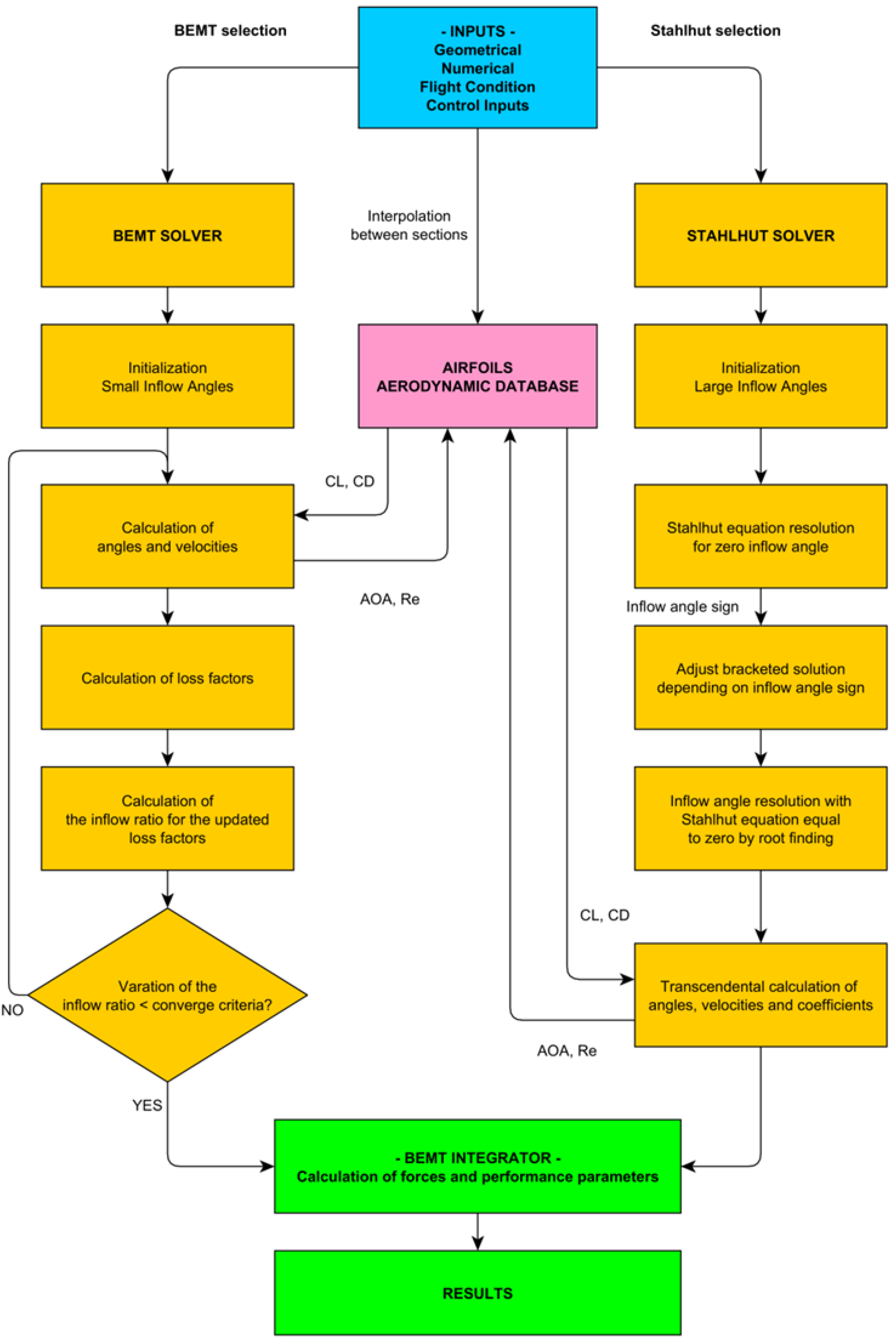

2. Analytical-Numerical Performance Model Architecture

- The flow is incompressible, inviscid, irrotational, and uniform

- There is a continuous flow velocity and pressure, except at the disk

- The airfoils through the blade do not interact between them

- The blades of a proprotor do not interact between them either

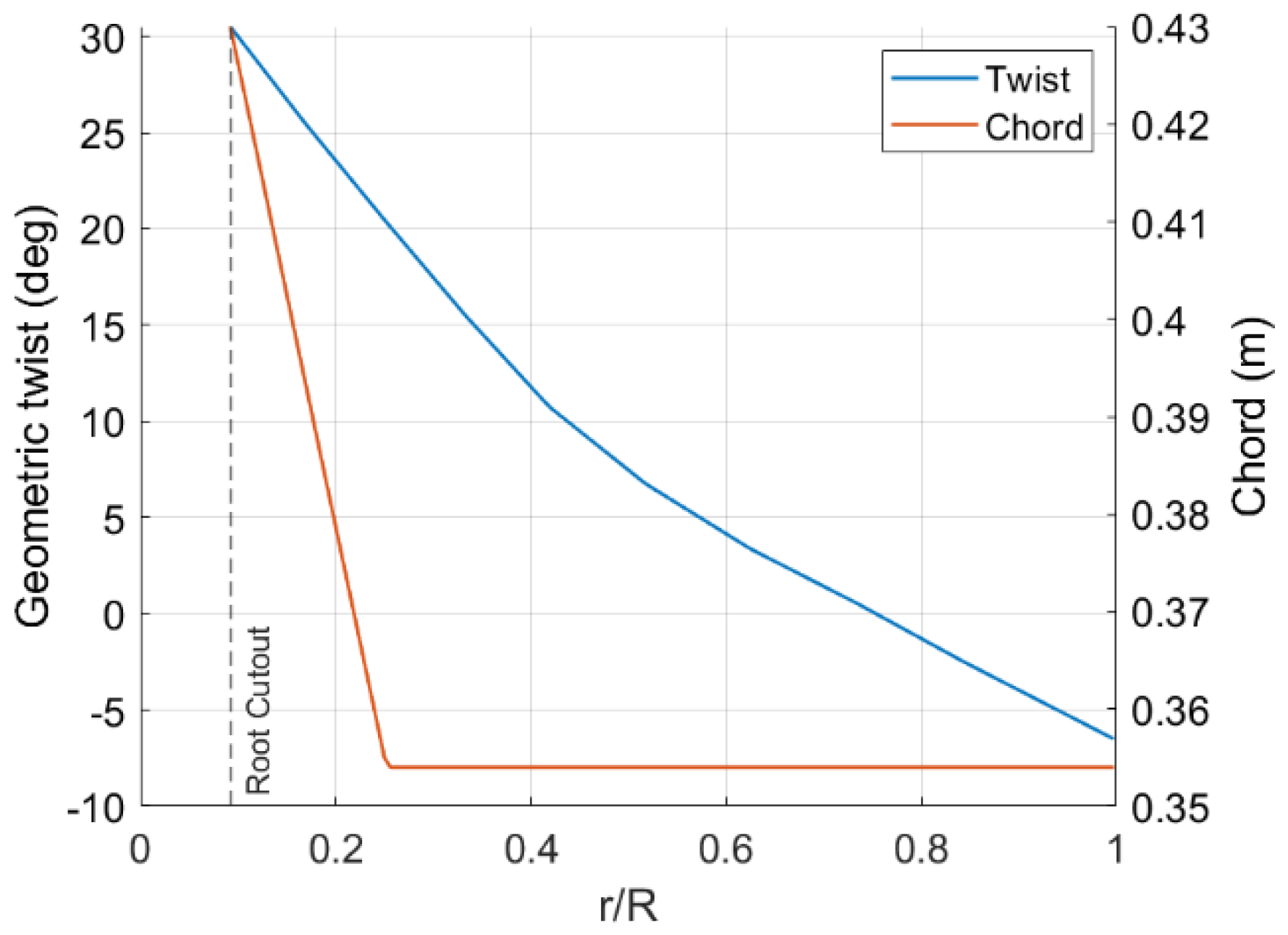

3. Specification of System Configuration

4. Validation of the BEMT and Stahlhut Models

4.1. Static Thrust Evaluation

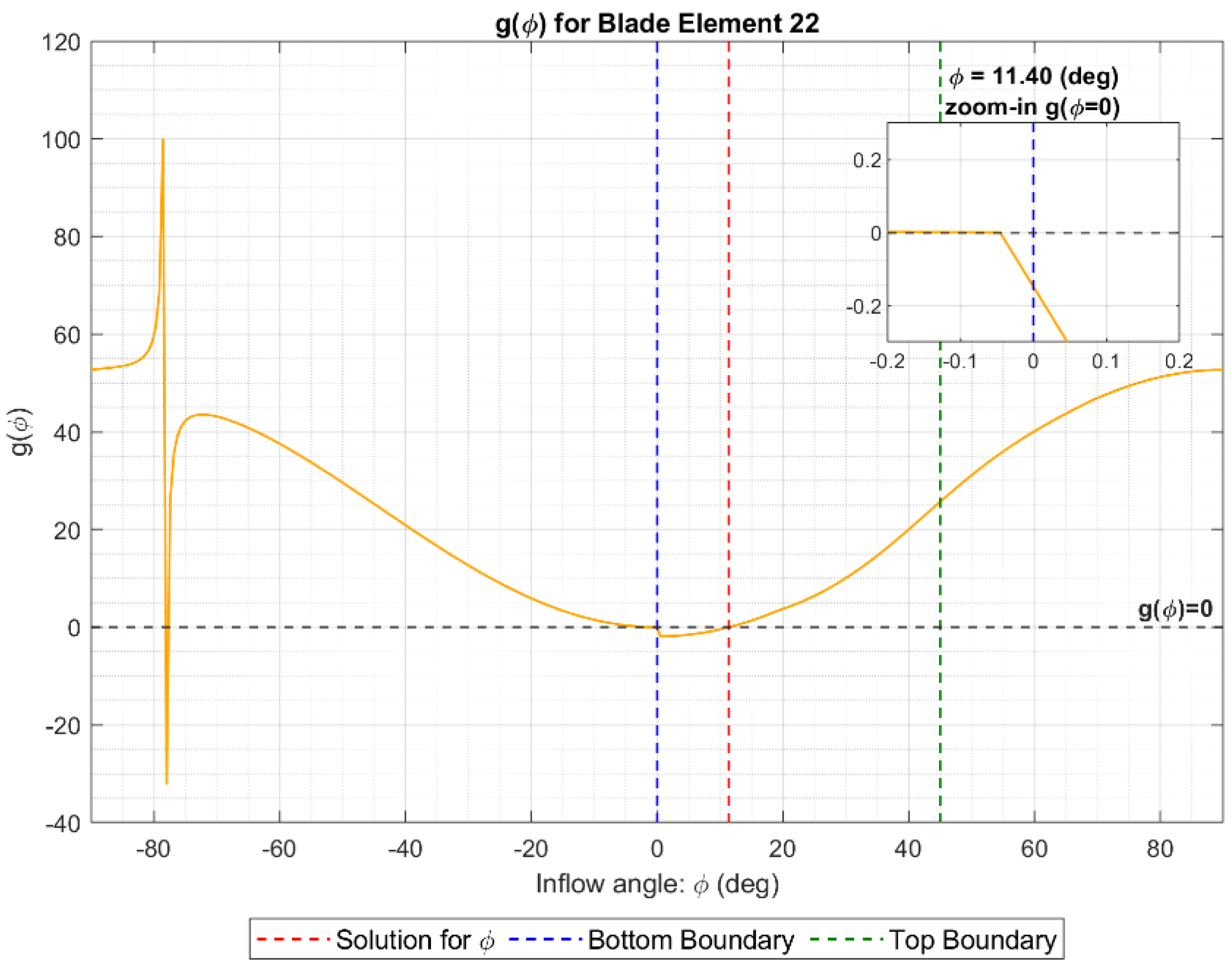

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis

5. Conclusions

References

- N. S. Zawodny, K. A. Pascioni, and C. S. Thurman, “An Overview of the Proprotor Performance Test in the 14 by 22 Foot Subsonic Tunnel,” FORUM 2023 - Vert. Flight Soc. 79th Annu. Forum Technol. Disp., 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Burdett and K. Van Treuren, “A Theoretical and Experimental Comparison of Optimizing Angle of Twist Using BET and BEMT,” 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Alba-Maestre, K. P. van Reine, T. Sinnige, and S. G. P. Castro, “Preliminary propulsion and power system design of a tandem-wing long-range evtol aircraft,” MDPI Sustain., vol. 11, no. 23, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Yan and C. L. Archer, “Assessing Compressibility Effects on the Performance of Large Horizontal-Axis Wind Turbines,”. [CrossRef]

- Y. El Khchine and M. Sriti, “Tip Loss Factor Effects on Aerodynamic Performances of Horizontal Axis Wind Turbine,” Energy Procedia, vol. 118, pp. 136–140, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Oliveira, J. G. de Matos, L. A. de S. Ribeiro, O. R. Saavedra, and J. R. P. Vaz, “Assessment of Correction Methods Applied to BEMT for Predicting Performance of Horizontal-Axis Wind Turbines,” MDPI Sustain., vol. 15, no. 8, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Wu, “CFD Body Force Propeller Model with Blade Rotational Effect,” MDPI, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Martín-San-Román, P. Benito-Cia, J. Azcona-Armendáriz, and A. Cuerva-Tejero, “Validation of a free vortex filament wake module for the integrated simulation of multi-rotor wind turbines,” Renew. Energy, vol. 179, pp. 1706–1718, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Mccaw, S. Turnock, and W. Batten, “The Coupling of Blade Element Momentum Theory and a Transient Timoshenko Beam Model to Predict Propeller Blade Vibration,” SMP’19 Sixth Int. Symp. Mar. Propulsors, no. May, 2019.

- H. R. (2015) Smith, “Engineering Models of Aircraft Propellers at Incidence,” 2015.

- C. W. Stahlhut and J. . G. Leishman, “Aerodynamic Design Optimization of Proprotors for Convertible-Rotor Concepts,” 2012.

- A. Bouhelal, A. Smaili, O. Guerri, and C. Masson, “Comparison of BEM and Full Navier-Stokes CFD Methods for Prediction of Aerodynamics Performance of HAWT Rotors,” Proc. 2017 Int. Renew. Sustain. Energy Conf. IRSEC 2017, no. December 2018, pp. 1–6, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Leng et al., “Aerodynamic Modeling of Propeller Forces and Moments at High Angle of Incidence,” AIAA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Xia, D. Ma, L. Zhang, X. Liu, and K. Cong, “Blade Shape Optimization and Analysis of a Propeller for VTOL Based on an Inverse Method,” MDPI, vol. 12, no. 7, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yao, D. Ma, L. Zhang, X. Yang, and Y. Yu, “Aerodynamic Optimization and Analysis of Low Reynolds Number Propeller with Gurney Flap for Ultra-High-Altitude Unmanned Aerial Vehicle,” MDPI, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Erik, T. Giljarhus, and A. Porcarelli, “Investigation of Rotor Efficiency with Varying Rotor Pitch Angle for a Coaxial Drone,” MDPI, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Piancastelli and M. Sali, “Tri-Rotor Propeller Design Concept, Optimization and Analysis of the Lift Efficiency During Hovering,” Arab. J. Sci. Eng., vol. 48, no. 9, pp. 12523–12539, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Silva, K. R. Antclif, S. K. S. Whiteside, and L. W. Kohlman, “Baseline Assumptions and Future Research Areas for Urban Air Mobility Vehicles,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20200002445 2020-08-05T22:20:26+00:00Z.

- K. Cong, D. Ma, L. Zhang, X. Xia, and Y. Yao, “Design and analysis of passive variable-pitch propeller for VTOL UAVs,” Aerosp. Sci. Technol., 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Lee and M. Dassonville, “Iterative Blade Element Momentum Theory for Predicting Coaxial Rotor Performance in Hover,” Am. Helicopter Soc., 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Jiménez, J. D. Hoyos, C. Echavarría, and J. P. Alvarado, “Exhaustive Analysis on Aircraft Propeller Performance through a BEMT Tool,” J. Aeronaut. Astronaut. Aviat. , vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 13–24, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Drela, “XFOIL: An Analysis and Design System for Low Reynolds Number Airfoils,” 1989. [CrossRef]

- J. C. P. J. Morgado, R. Vizinho, M.A.R. Silvestre, “XFOIL vs CFD performance predictions for high lift low Reynolds number airfoils,” Aerosp. Sci. Technol., 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Ledoux et al., “Analysis of the Blade Element Momentum Theory,” HAL Appl. Math., vol. 81, no. 6, pp. 2596–2621, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. F. Felker, L. A. Young, and D. B. Signor, “Performance and Loads Data from a Hover Test of a Full-Scale XV-15 Rotor,” 1986.

- G. Chen, D. Ma, Y. Jia, X. Xia, and C. He, “Comprehensive Optimization of the Unmanned Tilt-Wing Cargo Aircraft with Distributed Propulsors,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 137867–137883, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Maisel, D. C. Borgman, and D. D. Few, “Tilt Rotor Research Aircraft Familiarization Document,” 1975. [Online]. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/2060/19750016648.

- P. D. Peter B. S. Lissaman, “Wind turbine airfoils and rotor wakes,” in Wind Turbine Technology: Fundamental Concepts in Wind Turbine Engineering, Second Edition, 2009.

- J. L. Tangier and M. S. Selig, “An Evaluation of an Empirical Model for Stall Delay Due to Rotation for HAWTs,” Nrel/Cp-440-23258, no. July, pp. 1–12, 1997.

- C. A. Saias, I. Goulos, I. Roumeliotis, and V. Pachidis, “Preliminary Design of Hybrid-Electric Propulsion Systems for Emerging Urban Air Mobility Rotorcraft Architectures,” J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 143, 2021. [CrossRef]

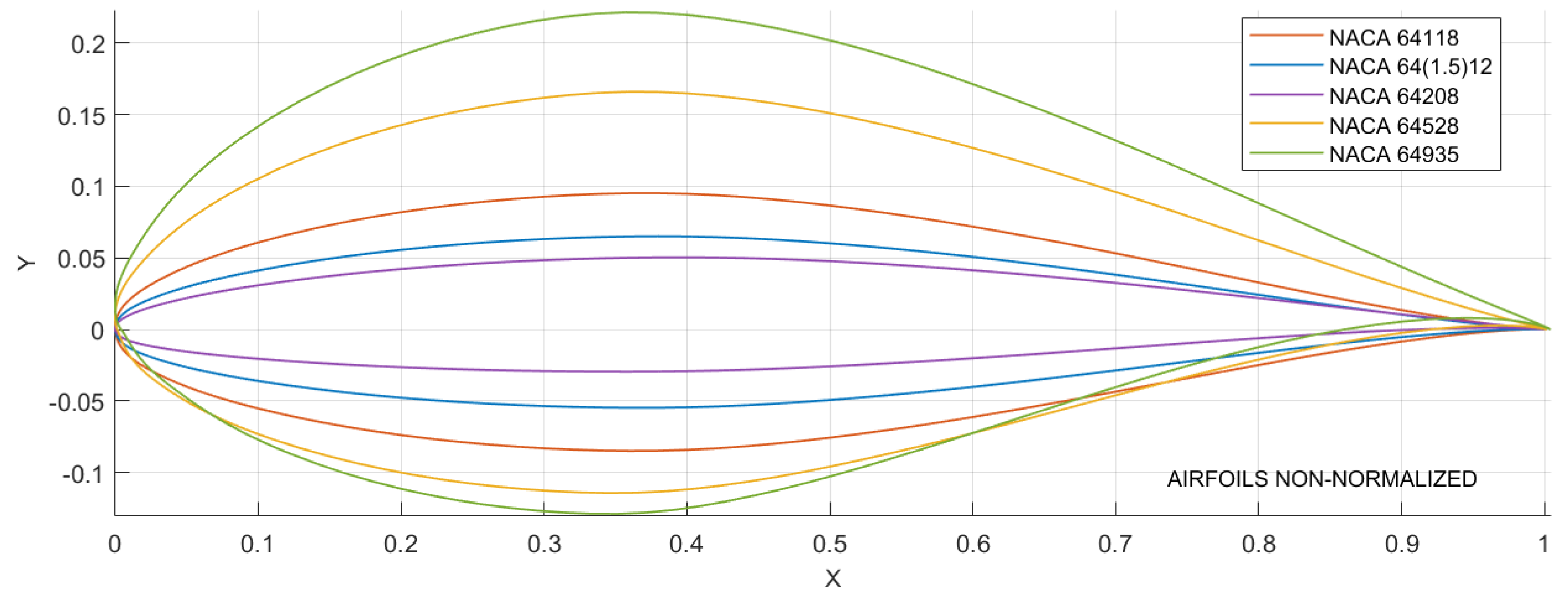

| Airfoil | r/R |

|---|---|

| NACA 64118 | 1.00 |

| NACA 64(1.5)12 | 0.80 |

| NACA 64208 | 0.51 |

| NACA 64528 | 0.17 |

| NACA 64935 | 0.09 |

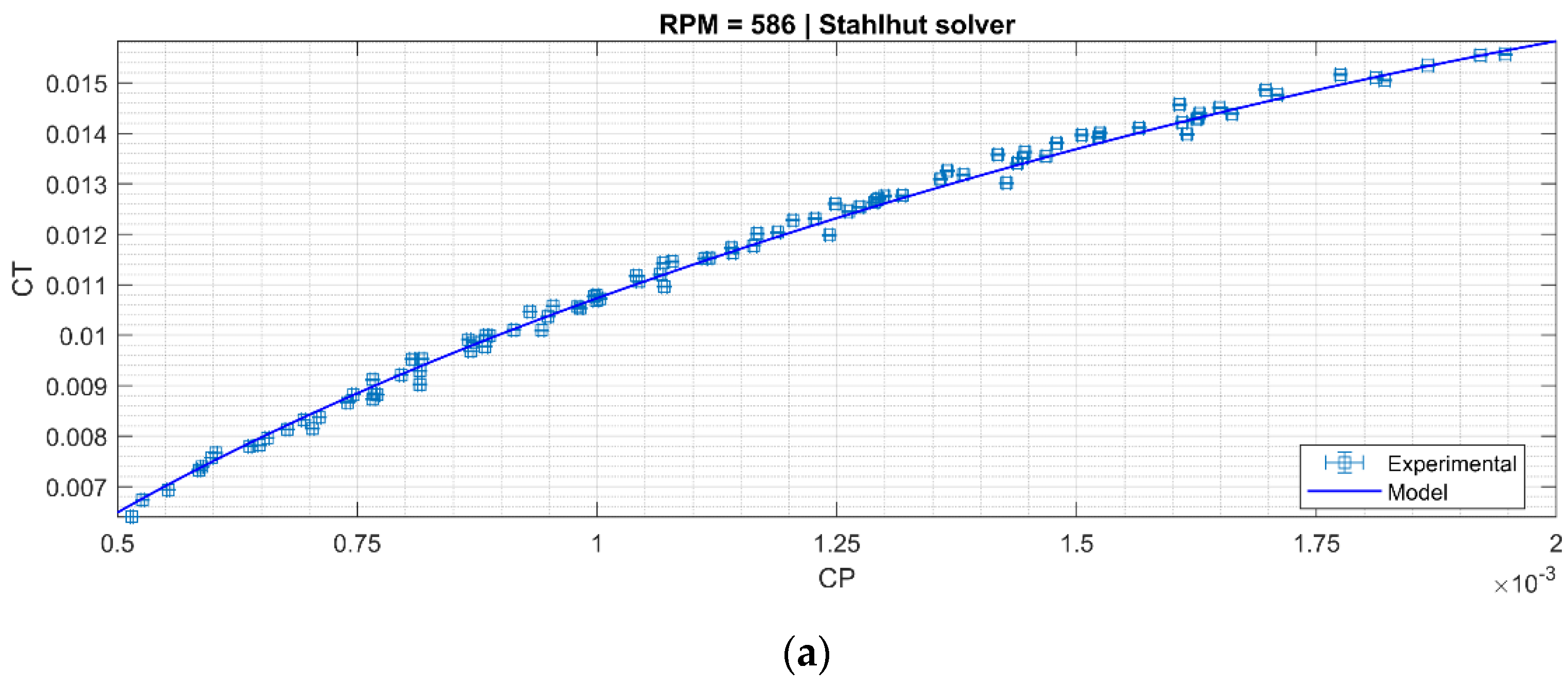

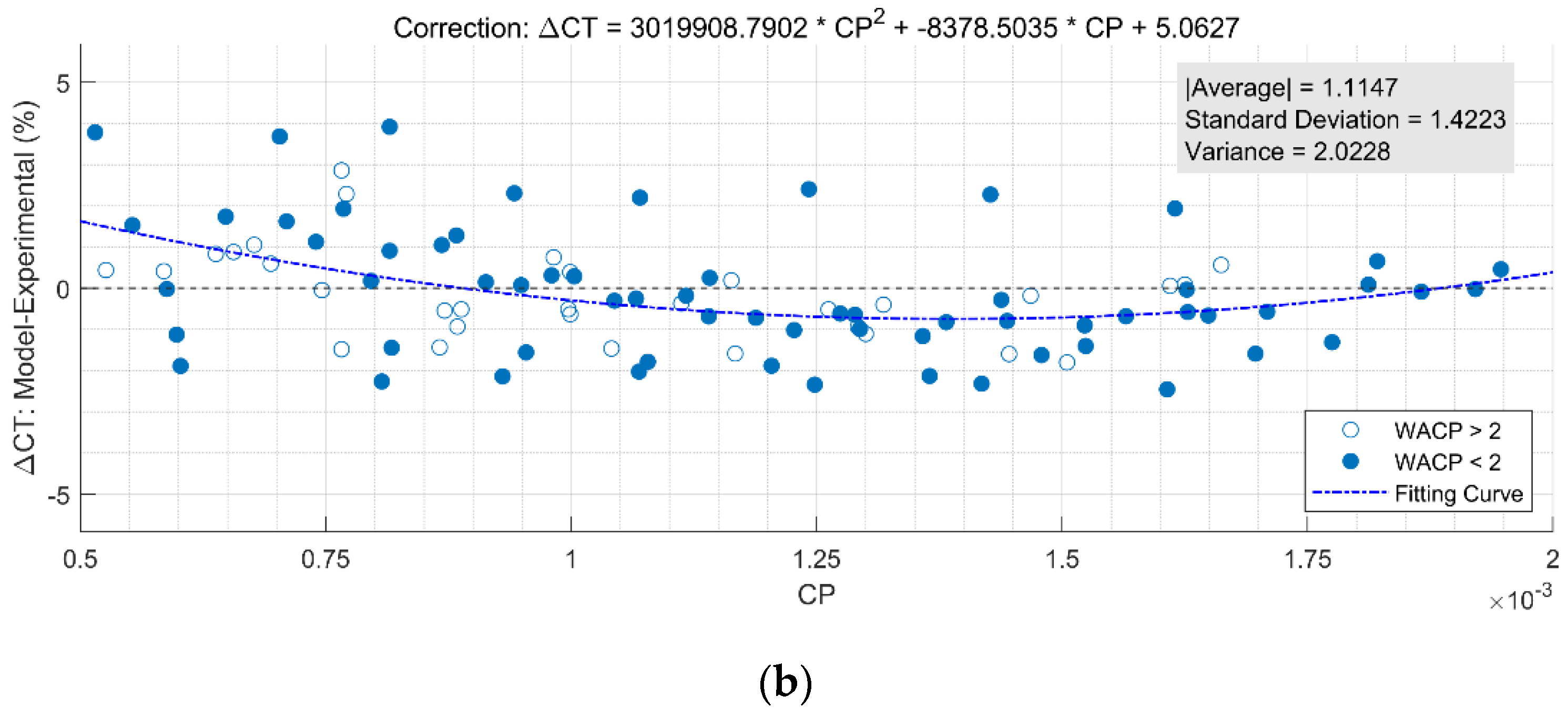

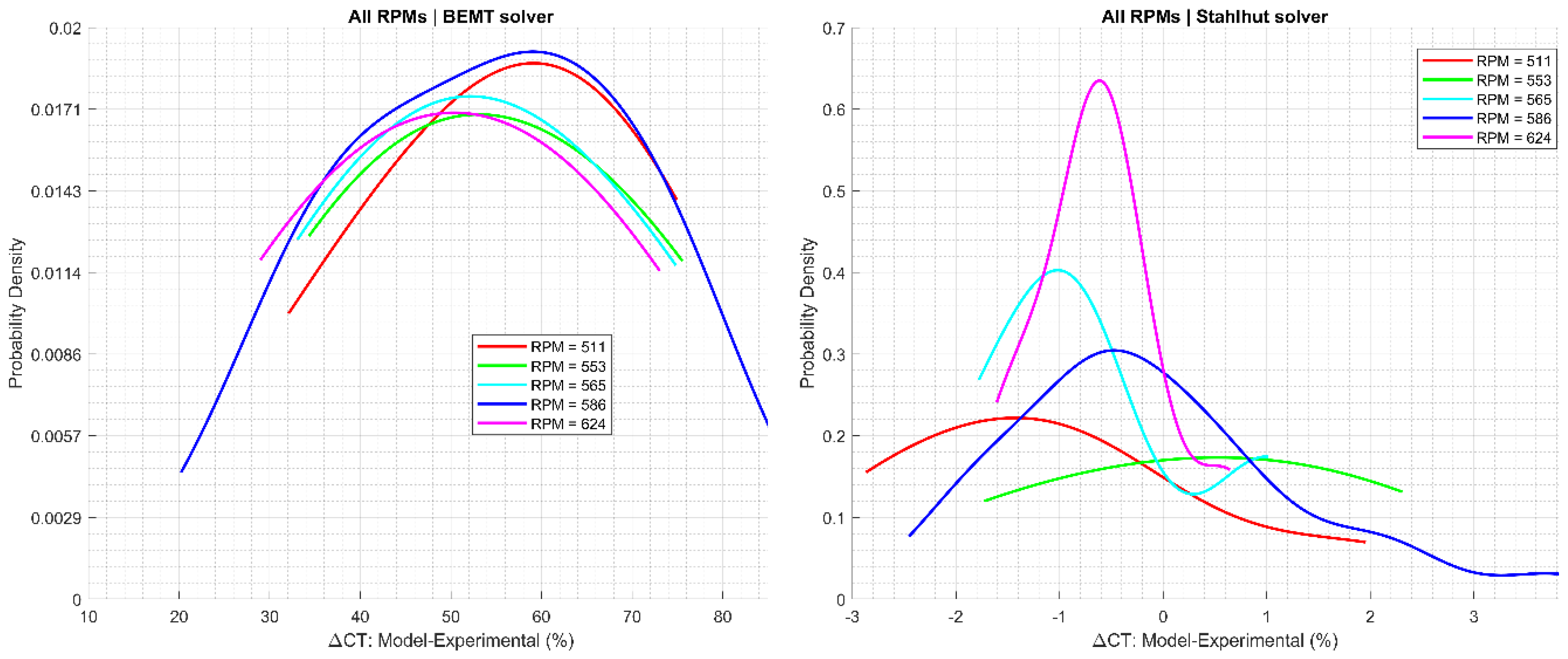

| Solver | RPM | Samples | |Average| | Standard Deviation | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEMT | 511 | 7 | 56.07 | 15.95 | 254.44 |

| 553 | 4 | 54.40 | 14.74 | 314.73 | |

| 565 | 4 | 53.44 | 17.59 | 309.43 | |

| 586 | 168 | 54.28 | 16.33 | 266.58 | |

| 624 | 8 | 50.74 | 16.67 | 277.97 | |

| Stahlhut | 511 | 7 | 1.64 | 1.71 | 2.92 |

| 553 | 4 | 1.35 | 1.74 | 3.03 | |

| 565 | 4 | 1.12 | 1.17 | 1.38 | |

| 586 | 168 | 1.11 | 1.42 | 2.02 | |

| 624 | 8 | 0.77 | 0.68 | 0.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).